Marshalsea

Encyclopedia

The Marshalsea was a prison on the south bank of the River Thames

in Southwark

, now part of London. From the 14th century until it closed in 1842, it housed men under court martial for crimes at sea, including those accused of "unnatural crimes"

, political figures and intellectuals accused of sedition

, and—most famously—London's debtors, the length of their stay determined largely by the whim of their creditors.

Run privately for profit, as were all prisons in England until the 19th century, the Marshalsea looked like an Oxbridge

college and functioned as an extortion

racket. For prisoners who could pay, it came with access to a bar, shop, and restaurant, as well as the crucial privilege of being allowed out during the day, which meant debtors could earn money to satisfy their creditors. Everyone else was crammed into one of nine small rooms with dozens of others, possibly for decades for the most modest of debts, which increased as unpaid prison fees accumulated. A parliamentary committee reported in 1729 that 300 inmates had starved to death within a three-month period, and that eight to ten prisoners were dying every 24 hours in the warmer weather.

The prison became known around the world in the 19th century through the writings of the English novelist Charles Dickens

, whose father was sent there in 1824 for a debt to a baker. Forced to leave school at the age of 12 for a job in a factory, Dickens based several of his characters on his experiences, most notably Amy Dorrit

, whose father was also a Marshalsea debtor.

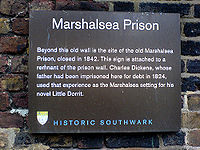

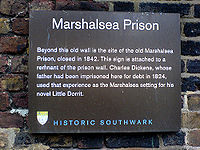

Much of the prison was demolished in the 1870s, though some of the buildings were used into the 20th century, housing an ironmonger's, a butter shop, and a printing house for the Marshalsea Press. All that is left of it now is the long brick wall that marked the southern boundary of the prison, on which a local history library now sits, the existence of what Dickens called "the crowding ghosts of many miserable years" marked only by a plaque from the local council. "[I]t is gone now," he wrote, "and the world is none the worse without it."

mareschalcie. The word was believed in the 16th and 17th centuries to be marshal + see, for seat, but in fact it derives from marshal + cy, as in "captaincy." "Marshal

" originally meant farrier

, from the Old Germanic marh ("horse") and scalc ("servant"), later becoming a title bestowed on those presiding over the courts of Medieval Europe

.

"Marshalsea" was originally the name of the Marshalsea Court. Also called the Court of the Verge, the Court of the Steward and Marshal, and the Court of the Marshalsea of the Household of the Kings of England, it was a special jurisdiction of the English royal household

that emerged around 1290, when the domestic rules and personnel of the Lord Steward

and Knight Marshal

began to constitute a judicial body. It assumed jurisdiction over members of the household living within "the verge", defined as within 12 miles (19.3 km) of the King's person, wherever that might be; it was therefore an "ambulatory" court, moving around the country with the King. It dealt with pleas of trespass, pleas of contempt, and cases of debt. In practice the court was often used for private disputes among people unconnected with the royal household, and its definition of "verge" went somewhat beyond 12 miles. The prison was originally built to hold prisoners being tried by the Marshalsea Court and the Court of the King's Bench, to which Marshalsea rulings could be appealed, but its use was soon extended, and the term "Marshalsea" came to be used for the prison itself.

Southwark (ˈsʌvək) was settled by the Romans

Southwark (ˈsʌvək) was settled by the Romans

around 43 CE. It served as an entry point into London from southern England, particularly along Watling Street

, the Roman road from Canterbury, which ran into Southwark's Borough High Street

. As a result it became known for its travellers and inns, including Geoffrey Chaucer

's Tabard Inn, and its population of criminals hiding out on the wrong side of the old London Bridge. The itinerant population brought with it poverty, prostitutes, bear baiting, theatres—including Shakespeare's Globe

—and, inevitably, prisons. In 1796, there were five within its boundaries: the Clink

, King's Bench Prison

, the White Lion, the Borough Compter

, and the Marshalsea, compared to just 18 in London as a whole.

Before the Bankruptcy Act of 1869 abolished debtors' prisons, men and women in England were routinely imprisoned for debt at the pleasure of their creditors, sometimes for decades. They would often take their families with them, the only alternative for the women and children being the shame of uncertain charity outside the jail, so that entire communities sprang up inside the debtors' prisons, with children born and raised there. Other European countries had legislation limiting imprisonment for debt to one year, but debtors in England were imprisoned until their creditors were satisfied, however long that took. When the Fleet Prison

Before the Bankruptcy Act of 1869 abolished debtors' prisons, men and women in England were routinely imprisoned for debt at the pleasure of their creditors, sometimes for decades. They would often take their families with them, the only alternative for the women and children being the shame of uncertain charity outside the jail, so that entire communities sprang up inside the debtors' prisons, with children born and raised there. Other European countries had legislation limiting imprisonment for debt to one year, but debtors in England were imprisoned until their creditors were satisfied, however long that took. When the Fleet Prison

closed in 1842, some debtors were found to have been there for 30 years.

The law offered no protection for people with assets tied up by inheritance laws, or for those who had paid their creditors as much as they could. Because prisons were privately administered, whole economies were created around the debtor communities, with the prison keepers charging rent (the so-called "jailor's fee"), bailiffs charging for food and clothing, attorneys charging legal fees in fruitless efforts to get the debtors out, and creditors, often tradesmen, increasing the debt simply because the debtor was in jail. The result was that the prisoners' families, including children, often had to be sent to work simply to pay the costs of keeping their breadwinner in prison, the debts accumulating to the point where there was no realistic prospect of release.

According to a petition presented to parliament in 1641, around 10,000 people in England and Wales were in prison for debt. Legislation began to address the problem from 1649 onwards, though it was slow to make any real difference. Helen Small writes that, under George III

(1760–1820), new legislation prevented debts of under 40 shillings leading to jail—roughly £ today—but even the smallest amounts would quickly exceed that once lawyers' fees were added. Under the Insolvent Debtors Act 1813, debtors could request release after 14 days in jail by taking an oath that their assets did not exceed £20, but if any of their creditors objected, they had to stay inside. Even after a lifetime in prison, the debt remained to be paid.

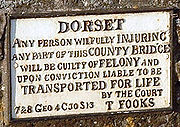

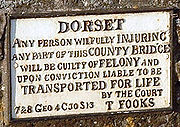

Until the late 19th century, imprisonment alone was not regarded in Britain as a punishment, at least not by those imposing it. Prisons were intended only to hold people until their creditors had been paid, or their fate decided by judges: usually execution, the stocks

Until the late 19th century, imprisonment alone was not regarded in Britain as a punishment, at least not by those imposing it. Prisons were intended only to hold people until their creditors had been paid, or their fate decided by judges: usually execution, the stocks

, flogging, the pillory

, or the ducking stool. Before the United States Declaration of Independence

in 1776, convicts were also sent to one of the American colonies

, a process known as penal transportation

, often for the most minor offence. When that stopped, they started being held instead in disused ships called hulks

moored in the Thames, and at Plymouth and Portsmouth, with the intention that they would be transported somewhere at some point. According to The National Archives at Kew, the establishment of these hulks marked the first involvement of central government in Britain in the administration of prisons. In 1787, penal transportation to Australia

began, lasting until 1867. A number of prisons were built by central government during this period to hold convicts awaiting transportation, most notably Millbank

, built in 1816, but also Parkhurst

(1838), Pentonville

(1842), Portland (1848), Portsmouth (1850), and Chatham (1856).

Prison reform gathered pace with the appointment of Sir Robert Peel

as Home Secretary in 1822. Before the Gaols Act 1823

, then the Prisons Act of 1835 and 1877, prisons such as the Marshalsea were administered by the royal household, and run for profit almost entirely without regulation by private individuals who purchased the right to manage and make money from them. Prisoners had to feed and clothe themselves and furnish their rooms. If food was supplied, it was bread and water, or something confiscated from the local market as unfit for human consumption; anyone unfortunate enough to have no money for food, and no one to bring it in for him, simply died of starvation. Robert Hughes

writes that jailors assumed the right to chain prisoners with as many iron fetters

as they chose, charging for their removal one at a time, the so-called "trade of chains," a practice that survived into the 1790s. In the Bishop of Ely

's prison, prisoners unable to pay for "easement of irons" were chained to the floor on their backs, with a spiked collar around the neck and heavy iron bars over the legs, until they somehow found the money.

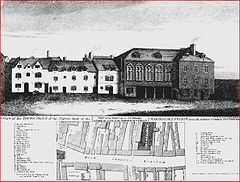

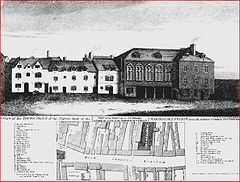

The Marshalsea occupied two buildings on what is now Borough High Street, the first from the beginning of the 14th century, and possibly earlier, at what would now be 161 Borough High Street, between King Street and Mermaid Court. In 1799, the government reported that the prison had fallen into a state of decay, though Robyn Adams writes that it was already crumbling and insecure by the late 16th century, and decided to rebuild it 130 yards (119 m) south on Borough High Street, on the site of the White Lion prison, also called the Borough Gaol. The second Marshalsea functioned as a prison from 1811 until 1849 at what is now 211 Borough High Street. Much of it was demolished in the 1870s, when the Home Office took over responsibility for running prisons, though parts of it existed into the 1950s at least, providing rooms and shops to rent.

The Marshalsea occupied two buildings on what is now Borough High Street, the first from the beginning of the 14th century, and possibly earlier, at what would now be 161 Borough High Street, between King Street and Mermaid Court. In 1799, the government reported that the prison had fallen into a state of decay, though Robyn Adams writes that it was already crumbling and insecure by the late 16th century, and decided to rebuild it 130 yards (119 m) south on Borough High Street, on the site of the White Lion prison, also called the Borough Gaol. The second Marshalsea functioned as a prison from 1811 until 1849 at what is now 211 Borough High Street. Much of it was demolished in the 1870s, when the Home Office took over responsibility for running prisons, though parts of it existed into the 1950s at least, providing rooms and shops to rent.

Although the first Marshalsea survived for 500 years, and the second for just 38, it is the latter that became widely known, thanks largely to Charles Dickens. Trey Philpotts writes that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit has a referent in the real Marshalsea of the 1820s. Dickens rarely made mistakes and did not exaggerate; if anything, he downplayed the licentiousness of Marshalsea life, perhaps to protect Victorian

sensibilities. Most of our information about the first Marshalsea comes from John Baptist Grano

(1692–ca. 1748), one of Handel's trumpeters at the opera house in Haymarket, who kept a detailed diary of his 458-day incarceration in the first Marshalsea—for a debt of £99 (worth £ today)—from 30 May 1728, until 23 September 1729.

The first Marshalsea was set slightly back from Borough High Street, its buildings measuring no more than 150 by 50 feet. There is no record of when it was built, but there is an early reference to it in 1329, when Agnes, wife of Walter de Westhale, surrendered herself there for having committed "trespass by force and arms" on Richard le Chaucer and his wife, Mary, relatives of the writer Geoffrey Chaucer

The first Marshalsea was set slightly back from Borough High Street, its buildings measuring no more than 150 by 50 feet. There is no record of when it was built, but there is an early reference to it in 1329, when Agnes, wife of Walter de Westhale, surrendered herself there for having committed "trespass by force and arms" on Richard le Chaucer and his wife, Mary, relatives of the writer Geoffrey Chaucer

, by helping her daughter, Joan, marry their son, John, who was only 12 years old and did not have their consent

.

Most of the first Marshalsea, as with the second, was taken up by debtors; in 1773, debtors within 12 miles of Westminster could be imprisoned there for a debt of 40 shillings. It also held a small number of men being tried at the Old Bailey

for crimes at sea. The prison was technically under the control of the Knight Marshal

, but it was let out to private individuals who ran it for profit. In 1727, for example, the Knight Marshal, Sir Philip Meadows, hired John Darby, a printer, as prison governor, who in turn leased it illegally to William Acton, a butcher (see below). Acton paid Darby £140 a year—roughly £ in 2009—for the right to act as resident warden and chief turnkey, and an additional £260 for the right to collect rent from the rooms, and sell food and drink.

; £14 in 2009—for a room with two beds on the Master's Side, shared with three other prisoners: Daniel Blunt, a tailor who owed £9, Benjamin Sandford, a lighterman from Bermondsey

who owed £55, and a Mr. Blundell, a jeweller.

The inmates called the prison the Castle. There was a turret

The inmates called the prison the Castle. There was a turret

ed lodge at the entrance, as with the older Oxbridge colleges, with a side room known as the Pound, where new prisoners would wait until a room was found for them. The courtyard leading out of the lodge was called the Park. It had been divided in two by a long, narrow wall, so that prisoners from the Common Side could spend their daylight hours there without being seen by those on the Master's Side, who preferred not to be distressed by the sight of abject poverty, especially when they might themselves be plunged into it at any moment. The wives, daughters, and lovers of male prisoners were allowed to live with them, so long as they behaved themselves and someone was paying their way. Women prisoners who could pay the fees were housed in the women's quarters, called "the Oak".

There was a bar run by the governor's wife, and a chandler's

shop run in 1728 by a Mr and Mrs Cary, both prisoners, which sold candles, soap, and a little food. When John Howard

(1726–1790), one of England's great 18th-century prison reformers, visited the Marshalsea on 16 March 1774, he found the shop being run by a man and his family who were not prisoners, and who were living in five of the rooms intended for inmates on the Master's Side. There was a coffee shop run in 1729 by a long-term prisoner, Sarah Bradshaw, and a chop-house called Titty Doll's, run by another prisoner, Richard McDonnell, and his wife. There was also a tailor and a barber, and prisoners from the Master's Side could hire prisoners from the Common Side to act as their servants.

Howard reported that there was no infirmary, and that the practice of "garnish" was in place (see below), whereby new prisoners were bullied into giving money to the older prisoners upon arrival. During his visit, the taproom, or beer room, had been let to a prisoner who was living "within the rules" of the King's Bench prison, which meant he was formally incarcerated in the King's Bench, but was allowed to live outside, within a certain radius of the prison, for a fee. Although legislation prohibited jailors from having a pecuniary interest in the sale of alcohol within their prisons, it was another rule that was completely ignored. Howard reported that 600 pots of beer were brought into the Marshalsea one Sunday from a public house

, because the prisoners did not like the beer available in the taproom. Rioting and drunkenness were the only ways the prisoners could be made to "disregard the confinement," he wrote.

Prisoners on the Master's Side rarely ventured to the Common Side. John Baptist Grano went there just once, on 4 August 1728, writing in his diary that, "I thought it would have kill'd me." There was no need for other prisoners to see it, John Ginger writes. It was enough that they knew it existed to keep the rental money, legal fees, and other gratuities flowing from the prisoner's families, fees that anywhere else would have seen them living in the lap of luxury, but which in the Marshalsea could be trusted merely to stave off disease and starvation.

Prisoners on the Master's Side rarely ventured to the Common Side. John Baptist Grano went there just once, on 4 August 1728, writing in his diary that, "I thought it would have kill'd me." There was no need for other prisoners to see it, John Ginger writes. It was enough that they knew it existed to keep the rental money, legal fees, and other gratuities flowing from the prisoner's families, fees that anywhere else would have seen them living in the lap of luxury, but which in the Marshalsea could be trusted merely to stave off disease and starvation.

By all accounts, living conditions were horrific. In 1639, prisoners complained that 23 women were being held in one room without space to lie down, leading to a revolt, with prisoners pulling down fences and attacking the guards with stones. Prisoners were regularly beaten with a "bull's pizzle", a whip made from a bull's penis, or tortured with thumbscrews and a skullcap, a vice

for the head that weighed 12 lb (5.4 kg). What often finished them off was being forced to lie in the Strong Room, a windowless shed near the main sewer, next to cadaver

s awaiting burial, of which there was a plentiful supply. Dickens wrote of it that it was "dreaded by even the most dauntless highwaymen and bearable only to toads and rats". One diabetic army officer, ejected from the Common Side because other inmates had complained about the smell of his urine, was moved to the Strong Room, where he died; his face was eaten by rats within three or four hours of his death, according to a witness.

During the wardship of William Acton in the 1720s the income from charities, collected from various begging bowls in circulation around Southwark and intended to buy food for inmates on the Common Side, was directed instead to a small group of trusted prisoners who policed the prison on Acton's behalf. The same group swore during Acton's trial in 1729 for murder (see below) that the Strong Room was the best room in the house. Ginger writes that Acton and his wife, who lived in a comfortable apartment near the Lodge, knew they were sitting on a powder keg. "When each morning the smell of freshly baked bread filled ... the yard ... only brutal suppression could prevent the Common Side from erupting", he writes.

The Common Side did erupt after a fashion in 1728 when Robert Castell, an architect and debtor in the Fleet prison

The Common Side did erupt after a fashion in 1728 when Robert Castell, an architect and debtor in the Fleet prison

who had been living in lodgings outside the jail "within the rules", was taken to a "sponging house" after he refused to pay a higher prison fee to the Fleet's notorious warden, Thomas Bambridge

. Sponging houses were private lodgings where prisoners were incarcerated before being taken to jail. They acquired the name because they squeezed the prisoner's last money out of him as if he were a sponge. When Castell arrived at the sponging house on 14 November he was forced to share space with a man who was dying of smallpox

, and as a result became infected and died less than a month later.

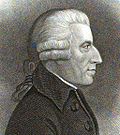

.jpg) Castell had a friend, James Oglethorpe

Castell had a friend, James Oglethorpe

, a Tory MP who became known years later for founding the American colony of Georgia

. He began to ask questions about the treatment of debtor prisoners, which resulted in the appointment in February 1729 of a parliamentary committee, the Gaols Committee, which he chaired. The committee visited the Fleet on 27 February and the Marshalsea on 25 March. Commissioned by Sir Archibald Grant

(see image on the right; Grant is standing third from the right), William Hogarth

accompanied the committee on its visit to the Fleet, sketching it, then later painting it in oil. The art historian Horace Walpole wrote of the painting in 1849: "The scene is the committee. On the table are the instruments of torture. A prisoner in rags, half-starved, appears before them. The poor man has a good countenance, that adds to the interest. On the other hand is the inhuman gaoler. It is the very figure that Salvator Rosa

would have drawn for Iago

in the moment of detection."

The committee was shocked by the prisoners' living conditions. They reported back to parliament that they had found, "the sale of offices, breaches of trust, enormous extortions, oppression, intimidation, gross brutalities, and the highest crimes and misdemeanours." In the Fleet they had found Sir William Rich, a baronet

, in irons. Unable to pay the prison fee, Rich had apparently been burned with a red-hot poker, hit with a stick, and kept in a dungeon for ten days for having wounded the warden with a shoemaker's knife. In the Marshalsea they found that prisoners on the Common Side were being routinely starved to death:

Not that being in the sick ward necessarily made the last month of life any easier:

As a result of the Gaols Committee's inquiries, several key figures within the jails were tried for murder in August 1729, including Thomas Bambridge of the Fleet, and William Acton of the Marshalsea. Given the strongly worded report of the Gaols Committee, the trials were major public events. John Ginger writes that, when the Prince of Wales's

As a result of the Gaols Committee's inquiries, several key figures within the jails were tried for murder in August 1729, including Thomas Bambridge of the Fleet, and William Acton of the Marshalsea. Given the strongly worded report of the Gaols Committee, the trials were major public events. John Ginger writes that, when the Prince of Wales's

bookseller presented his bill at the end of that year, two of the 41 volumes on it were accounts of William Acton's trial.

The first case against Acton was for the murder of Thomas Bliss, a debtor. Unable to pay the prison fees, he had been left with so little to eat that he tried to escape by throwing a rope over the wall, but his pursuers severed it and he fell 20 feet into the prison yard. Wanting to know who had supplied the rope, Acton beat him with a bull's pizzle, stamped on his stomach, placed him in "the hole"—a small damp space under the stairs, which had no floor, and was too small to lie down or stand up in—then in the Strong Room. Originally built to hold pirates, the Strong Room was just a few yards from the prison's sewer. It was never cleaned, had no drain, no sunlight, almost no fresh air—the smell was described as "noisome"—and was full of rats, and sometimes "several barrow fulls of dung". A number of prisoners told the court that it contained no bed, so that prisoners had to lie on the damp floor, often next to the corpses of previous inhabitants. But a group of favoured prisoners Acton had paid to police the jail said there was indeed a bed. One of them said he often chose to lie in there himself, because the Strong Room was so clean; the "best room on the Common side of the jail", said another. This, despite the court's having heard that one prisoner's left side had mortified from lying on the wet floor, and that a rat had eaten the nose, ear, cheek and left eye of another.

Bliss was left in the Strong Room for three weeks wearing a skullcap (a heavy vice for the head), thumb screws, iron collar, leg irons

, and irons round his ankles called sheers. One witness said the swelling in his legs was so bad that the irons on one side could no longer be seen for overflowing flesh. His wife, who was able to see him through a small hole in the door, testified that he was bleeding from the mouth and thumbs. He was given a small amount of food but the skullcap prevented him from chewing; he had to ask another prisoner, Susannah Dodd, to chew his meat for him. He was eventually taken to the sick ward, and died a few months later.

The court was told of three other cases. Captain John Bromfield, Robert Newton, and James Thompson all died after similar treatment from Acton: a beating, followed by time in "the hole" or Strong Room, before being moved to the sick ward, where they were left to lie on the floor in leg irons. So concerned was Acton for his reputation that he requested the indictments be read out in Latin, but his worries were misplaced. The government wanted an acquittal to protect the good name of the Knight Marshal, Sir Philip Meadows, who had hired John Darby as prison governor, who in turn had leased it to Acton. Acton's favoured prisoners had testified on his behalf, introducing contradictory evidence that the judge could not ignore. A stream of witnesses spoke of his good character, including his butcher, brewer, confectioner, and solicitor—his coal merchant thought Acton "improper for the post he was in from his too great compassion"—and he was found not guilty on all charges. The Gaols Committee had succeeded in drawing attention to the situation in England's jails, but reform had eluded them.

Though most of the prisoners in the Marshalsea were debtors, the prison was regarded as second in importance only to the Tower of London

Though most of the prisoners in the Marshalsea were debtors, the prison was regarded as second in importance only to the Tower of London

, and several political figures were held there, mostly for sedition

and other kinds of inappropriate behaviour. William Hepworth Dixon wrote in 1885 that it was full of poets, pirates, parsons, plotters, coiners, libellers, defaulters, Jesuits, and vagabonds of every class.

It became the main holding prison for Roman Catholics suspected of sedition during the Elizabethan era

. Bishop Bonner, the last Roman Catholic Bishop of London, was imprisoned there in 1559, supposedly for his own safety, until his death 10 years later. William Herle

, a spy for Lord Burghley

, Elizabeth I's chief adviser, was held there in 1570 and 1571. In correspondence with the Queen's advisers regarding Marshalsea prisoners he suspected of involvement in a plot to kill her—the so-called Ridolfi plot

—Herle reveals an efficient network within the prison for smuggling information out of it, which included hiding letters in holes in the crumbling brickwork for others to pick up. Robyn Adams writes that the prison leaked both physically and metaphorically.

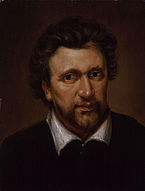

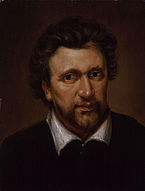

Intellectuals also regularly found themselves in the Marshalsea. Ben Jonson

, the playwright, a friend of Shakespeare

, was jailed in 1597 for The Isle of Dogs

, regarded as so inappropriate that it was immediately suppressed, with no known extant copies; on 28 July, the Privy Council

was told it was a "lewd plaie that was plaied in one of the plaie houses on the Bancke Side

, contaynynge very seditious and sclandrous matter". The poet Christopher Brooke was jailed in 1601 for helping the 17-year-old Ann More marry John Donne

without her father's consent. George Wither

, the political satirist, wrote his poem "The Shepherd's Hunting" in the Marshalsea in 1614 while being held for four months for libel, based on his Abuses Stript and Whipt, 20 satires criticizing revenge, ambition, and lust, one of them directed at the Lord Chancellor

.

Nicholas Udall

, vicar of Braintree and headmaster of Eton College

, was sent there in 1541 for buggery

and suspected theft, though his appointment in 1555 as headmaster of Westminster School

suggests the episode did his name no lasting harm. In 1632 Sir John Eliot

, the Vice-Admiral of Devon, after being sent to the Marshalsea from the Tower of London for questioning the right of the King to tax imports and exports

, described the move as leaving his palace in London for his country house in Southwark. John Selden

, the jurist, was jailed there in 1629 for his involvement in drafting the Petition of Right

, a document limiting the actions of the King, regarded as seditious even though it had been passed by Parliament, and Colonel Culpeper in 1685 or 1687 for striking the Duke of Devonshire

on the ear.

When the prison reformer James Neild (1744–1814) visited the prison in December 1802, just 34 debtors were living there, along with eight wives and seven children. Neild wrote that it was in "a most ruinous and insecure state, and the habitations of the debtors wretched in the extreme." The government had already acknowledged in 1799 that it had fallen into a state of decay. A decision was made to rebuild it 130 yards south (119 m), on the site of the White Lion prison, also known as the Borough Gaol.

When the prison reformer James Neild (1744–1814) visited the prison in December 1802, just 34 debtors were living there, along with eight wives and seven children. Neild wrote that it was in "a most ruinous and insecure state, and the habitations of the debtors wretched in the extreme." The government had already acknowledged in 1799 that it had fallen into a state of decay. A decision was made to rebuild it 130 yards south (119 m), on the site of the White Lion prison, also known as the Borough Gaol.

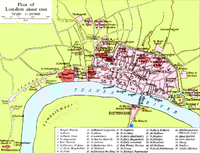

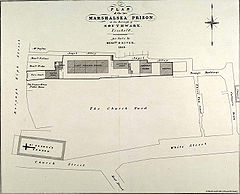

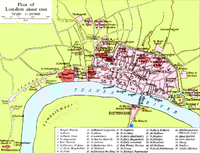

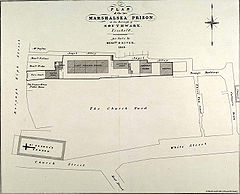

Construction began at 150 High Street—now called Borough High Street—on the south side of Angel Court and Angel Alley, two narrow streets that no longer exist. The site was just north of St George's Church, the location of the 16th-century White Lion prison or "Borough Goal" [sic], as it is known on Richard Horwood

's 1792 map of London (see left). Eventually costing £8,000 to build—£ today—it opened in 1811 with two sections, one for Admiralty prisoners under court martial, and one for debtors, with a shared chapel that had been part of the White Lion. In 1827, 414 out of its 630 debtors were there for debts under £20.

Charles Dickens

(1812–1870) became another major source of information about the second Marshalsea after his father, John

, was sent there as a debtor on 20 February 1824, under the Insolvent Debtor's Act 1813; he owed a baker, James Kerr, £40 and 10 shillings, a sum equivalent to £ in .

Twelve years old at the time, Dickens was sent to live in lodgings with Mrs. Ellen Roylance in Little College Street, Camden Town

, from where he walked five miles (8 km) every day to Warren's blacking factory at 30 Hungerford Stairs, a factory owned by a relative of his mother's. He spent 10 hours a day wrapping bottles of shoe polish for six shillings a week to pay for his keep. His mother, Elizabeth Barrow, and her three youngest children, joined her husband in the Marshalsea in April and, from then on Dickens would visit them every Sunday, until he found lodgings in Lant Street, closer to the prison, in the attic of a house belonging to the vestry clerk of St George's Church. This meant he was able to breakfast with his family in the Marshalsea and dine with them after work.

His father was released after three months, on 28 May 1824, but the family's financial situation remained poor, and Dickens had to continue working at the factory, something he reportedly never forgave his mother for. He subsequently wrote about the Marshalsea and other debtors' prisons in three novels, The Pickwick Papers

(published in installments between 1836–1837); David Copperfield (1849–1850); and finally Little Dorrit

(1855–1857), in which the main character, Amy, is born in the Marshalsea to a debtor imprisoned for reasons so complex no one can fathom how to get him out.

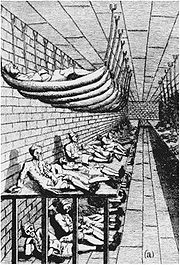

Like the first Marshalsea, the second was notoriously cramped. The debtors' section consisted of a brick barracks, a yard measuring 177 × 56 ft (54 m x 17 m), a kitchen, a public room, and a "tap room" or snuggery, where debtors could drink as much beer as they wanted, at fivepence a pot in 1815. The barracks was less than ten yards wide and 33 yards long (nine by 30 m) and was divided into eight houses, each with three floors, containing 56 rooms in all. Each floor had seven rooms facing the front and seven in the back. There were no internal hallways. The rooms were accessed directly from the outside via eight narrow wooden staircases, a situation regarded as a fire hazard, because the stairs were the only exits and the houses were separated only by thin lathe and plaster partitions.

Like the first Marshalsea, the second was notoriously cramped. The debtors' section consisted of a brick barracks, a yard measuring 177 × 56 ft (54 m x 17 m), a kitchen, a public room, and a "tap room" or snuggery, where debtors could drink as much beer as they wanted, at fivepence a pot in 1815. The barracks was less than ten yards wide and 33 yards long (nine by 30 m) and was divided into eight houses, each with three floors, containing 56 rooms in all. Each floor had seven rooms facing the front and seven in the back. There were no internal hallways. The rooms were accessed directly from the outside via eight narrow wooden staircases, a situation regarded as a fire hazard, because the stairs were the only exits and the houses were separated only by thin lathe and plaster partitions.

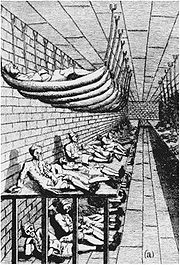

Women debtors were housed in rooms over the tap room. Most of the rooms for men were 10.5 feet (3.2 m) square and 8.5 feet (2.6 m) square, with boarded floors, a fireplace, and a glazed window. Each housed two or three prisoners, and as the rooms were too small for two beds, prisoners had to share. The anonymous witness complained in 1833: "170 persons have been confined at one time within these walls, making an average of more than four persons in each room—which are not ten feet square!!! I will leave the reader to imagine what the situation of men, thus confined, particularly in the summer months, must be."

Much of the prison business was run by a debtors' committee of nine prisoners and a chair—a position held by Dickens's father, John—who were appointed on the last Wednesday of each month, and met every Monday at 11 a.m. The committee was responsible for imposing fines for rules violations, an obligation they appear to have met with enthusiasm. Debtors could be fined for theft; throwing water or filth out of windows or into someone else's room; making noise after midnight; cursing, fighting, or singing obscene songs; smoking in the beer room between eight and ten in the morning, or twelve and two in the afternoon; defacing the staircase; dirtying the privy seats; stealing newspapers or utensils from the snuggery; urinating

in the yard; drawing water before it had boiled—and for criticizing the committee, which the parliamentary commissioners wrote had "too frequently been the case".

As dreadful as the Marshalsea could be, it was a haven for some prisoners, especially if they had no prospect of employment, to the point where discharge might be used as a form of punishment—one Marshalsea debtor was discharged in 1801 for "making a Noise and disturbance in the prison". John Ginger writes that one of the few times John Baptist Grano let loose and cursed the Marshalsea, calling it the "vilest Gaol in the Three Kingdoms", was the night he found himself accidentally locked out of it. Dr. Haggage in Little Dorrit tells another prisoner, "We are quiet here; we don't get badgered here; there's no knocker, sir, to be hammered at by creditors and bring a man's heart into his mouth ... we have got to the bottom, we can't fall, and what have we found? Peace. That's the word for it. Peace."

.

After garnish, prisoners were given a "chum ticket", which told them which room was theirs. Most were expected to "chum" with other prisoners. They would often spend the first night in the infirmary until a room could be made ready, and would sometimes spend three or four nights walking around the yard before a chum could be found, though they were already being charged for the room they did not have. There was a strict principle of rotation, whereby the newest arrival was placed with the youngest prisoner who was living alone. A wealthier prisoner could pay his roommates to go away—"buy out the chum"—for half-a-crown a week, and could live by himself, while the outcast chum would either pay for lodgings somewhere else in the prison, or sleep in the tap room. The only prisoners not expected to pay "chummage" were debtors who had declared themselves insolvent by swearing an oath that their assets were worth fewer than 40 shillings. If their creditors agreed, they could be released after 14 days, but if anyone objected, they remained confined to the "poor side" of the building, near the women's side, receiving a small weekly allowance from the county, and money from charity.

The Admiralty division housed a few prisoners under naval courts martial for mutiny, desertion, piracy, and what the deputy marshal preferred in 1815 to call "unnatural crimes". Unlike other parts of the prison that had been built from scratch in 1811, the Admiralty division—as well as the northern boundary wall, the dayroom, and the chapel—had been part of the old Borough gaol, and were considerably run down, the cells so rotten they were barely able to confine prisoners. In 1817, one actually managed to break through his cell walls. The low boundary wall together with the irregular use of spikes meant that Admiralty prisoners were often housed in the infirmary, chained to bolts fixed to the floor.

The Admiralty division housed a few prisoners under naval courts martial for mutiny, desertion, piracy, and what the deputy marshal preferred in 1815 to call "unnatural crimes". Unlike other parts of the prison that had been built from scratch in 1811, the Admiralty division—as well as the northern boundary wall, the dayroom, and the chapel—had been part of the old Borough gaol, and were considerably run down, the cells so rotten they were barely able to confine prisoners. In 1817, one actually managed to break through his cell walls. The low boundary wall together with the irregular use of spikes meant that Admiralty prisoners were often housed in the infirmary, chained to bolts fixed to the floor.

They were supposed to have a separate yard to exercise in, so that criminals were not mixing with debtors, but in fact the prisoners mixed often, and according to Dickens, happily. The parliamentary committee deplored this practice, arguing that the Admiralty prisoners were characterized by an "entire absence of all control," and were bound to have a bad effect on the debtors. The two groups of prisoners would retreat to their own sections during inspections, or as Dickens put it:

Whether there as visitors or prisoners, women risked being "ruined

", with or without their consent

. The anonymous witness talks about the risk of rape, or of being tempted into prostitution: "How often has female virtue been assailed in poverty? Alas how often has it fallen, in consequence of a husband or a father having been a prisoner for debt?" The prison doctor lived outside the Marshalsea and would visit every other day to attend to prisoners, and sometimes their children—to "protect his reputation", according to one of the parliamentary reports—but would not attend to their wives. This left the women to give birth alone or with the help of other prisoners. A Marshalsea doctor told a parliamentary commission that he could recall having helped just once with a birth, and then only as a matter of courtesy, because it was not included in his salary.

The Marshalsea was closed by an Act of Parliament in 1842, and on 19 November that year, the inmates were relocated to the hospital at Bethlem

The Marshalsea was closed by an Act of Parliament in 1842, and on 19 November that year, the inmates were relocated to the hospital at Bethlem

if they were mentally ill, or to the King's Bench Prison, at that point renamed the Queen's Prison. On 31 December 1849, the Court of the Marshalsea of the Household of the Kings of England was abolished, and its power transferred to Her Majesty's Court of Common Pleas at Westminster.

The buildings and land were auctioned off in July 1843 and purchased by W.G. Hicks, an ironmonger, for £5,100. The property consisted of the keeper's house, the canteen—called a suttling house—the Admiralty section, the chapel, a three-story brick building, and eight brick houses, all of it closed off from Borough High Street by iron gates. In 1869, imprisonment for debt was finally outlawed in England, except in cases of fraud or refusal to pay, and in the 1870s the Home Office demolished most of the prison buildings, though parts of it were still in use in 1955 as a store for George Harding & Sons, hardware merchants.

Dickens visited what was left of the Marshalsea on 5 May 1857, just before he finished Little Dorrit, when parts of it were being let as rooms or apartments. He wrote in the preface:

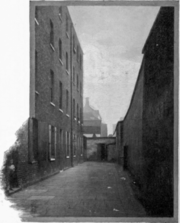

All that remains of the Marshalsea today is the brick wall that marked the southern boundary of the prison, now separating the Local Studies library from a small public garden that used to be a graveyard. The boundary wall is marked on the garden side—on what would have been the external wall of the prison—by a plaque from the local council. The Cuming Museum

All that remains of the Marshalsea today is the brick wall that marked the southern boundary of the prison, now separating the Local Studies library from a small public garden that used to be a graveyard. The boundary wall is marked on the garden side—on what would have been the external wall of the prison—by a plaque from the local council. The Cuming Museum

has one of the prison's pumps, and the Dickens House Museum one of its windows.

The surviving wall is identified by English Heritage

as the southern boundary of the prison, and runs along the narrow alleyway that was the internal prison courtyard (see right), now called Angel Place. The name has led to confusion, because there used to be two alleyways on the north side of the Marshalsea—Angel Court and Angel Alley—the first of which Dickens refers to when giving directions to the prison remains in 1857. See Richard Horwood's 18th century map, which shows Angel Court/Angel Alley near the Borough Goal [sic], marked by the number 2.

Angel Place (see left) lies between Southwark's Local Studies Library at 211 Borough High Street

, Southwark, London SE1 and the small public garden that was formerly St George's churchyard. It is just north of the junction of Borough High Street and Tabard Street. It can be reached by bus (numbers 21, 35, 40, 133, and C10); by underground on the Northern line to Borough tube station

; or by train to London Bridge station

.

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

in Southwark

Southwark

Southwark is a district of south London, England, and the administrative headquarters of the London Borough of Southwark. Situated east of Charing Cross, it forms one of the oldest parts of London and fronts the River Thames to the north...

, now part of London. From the 14th century until it closed in 1842, it housed men under court martial for crimes at sea, including those accused of "unnatural crimes"

Buggery Act 1533

The Buggery Act 1533, formally An Acte for the punysshement of the vice of Buggerie , was an Act of the Parliament of England that was passed during the reign of Henry VIII...

, political figures and intellectuals accused of sedition

Sedition

In law, sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent to lawful authority. Sedition may include any...

, and—most famously—London's debtors, the length of their stay determined largely by the whim of their creditors.

Run privately for profit, as were all prisons in England until the 19th century, the Marshalsea looked like an Oxbridge

Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge in England, and the term is now used to refer to them collectively, often with implications of perceived superior social status...

college and functioned as an extortion

Extortion

Extortion is a criminal offence which occurs when a person unlawfully obtains either money, property or services from a person, entity, or institution, through coercion. Refraining from doing harm is sometimes euphemistically called protection. Extortion is commonly practiced by organized crime...

racket. For prisoners who could pay, it came with access to a bar, shop, and restaurant, as well as the crucial privilege of being allowed out during the day, which meant debtors could earn money to satisfy their creditors. Everyone else was crammed into one of nine small rooms with dozens of others, possibly for decades for the most modest of debts, which increased as unpaid prison fees accumulated. A parliamentary committee reported in 1729 that 300 inmates had starved to death within a three-month period, and that eight to ten prisoners were dying every 24 hours in the warmer weather.

The prison became known around the world in the 19th century through the writings of the English novelist Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...

, whose father was sent there in 1824 for a debt to a baker. Forced to leave school at the age of 12 for a job in a factory, Dickens based several of his characters on his experiences, most notably Amy Dorrit

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit is a serial novel by Charles Dickens published originally between 1855 and 1857. It is a work of satire on the shortcomings of the government and society of the period....

, whose father was also a Marshalsea debtor.

Much of the prison was demolished in the 1870s, though some of the buildings were used into the 20th century, housing an ironmonger's, a butter shop, and a printing house for the Marshalsea Press. All that is left of it now is the long brick wall that marked the southern boundary of the prison, on which a local history library now sits, the existence of what Dickens called "the crowding ghosts of many miserable years" marked only by a plaque from the local council. "[I]t is gone now," he wrote, "and the world is none the worse without it."

Etymology, Marshalsea Court

"Marshalsea" is historically the same word as "marshalcy"—"the office, rank, or position of a marshal"—deriving from the Anglo-FrenchAnglo-Norman language

Anglo-Norman is the name traditionally given to the kind of Old Norman used in England and to some extent elsewhere in the British Isles during the Anglo-Norman period....

mareschalcie. The word was believed in the 16th and 17th centuries to be marshal + see, for seat, but in fact it derives from marshal + cy, as in "captaincy." "Marshal

Marshal

Marshal , is a word used in several official titles of various branches of society. The word is an ancient loan word from Old French, cf...

" originally meant farrier

Farrier

A farrier is a specialist in equine hoof care, including the trimming and balancing of horses' hooves and the placing of shoes on their hooves...

, from the Old Germanic marh ("horse") and scalc ("servant"), later becoming a title bestowed on those presiding over the courts of Medieval Europe

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

.

"Marshalsea" was originally the name of the Marshalsea Court. Also called the Court of the Verge, the Court of the Steward and Marshal, and the Court of the Marshalsea of the Household of the Kings of England, it was a special jurisdiction of the English royal household

Royal Households of the United Kingdom

The Royal Households of the United Kingdom are the organised offices and support systems for the British Royal Family, along with their immediate families...

that emerged around 1290, when the domestic rules and personnel of the Lord Steward

Lord Steward

The Lord Steward or Lord Steward of the Household, in England, is an important official of the Royal Household. He is always a peer. Until 1924, he was always a member of the Government...

and Knight Marshal

Knight Marshal

The Knight Marshal is a former office in the British Royal Household established by King Henry III in 1236. The position later became a Deputy to the Earl Marshal from the reign of Henry VIII until the office was abolished in 1846 ....

began to constitute a judicial body. It assumed jurisdiction over members of the household living within "the verge", defined as within 12 miles (19.3 km) of the King's person, wherever that might be; it was therefore an "ambulatory" court, moving around the country with the King. It dealt with pleas of trespass, pleas of contempt, and cases of debt. In practice the court was often used for private disputes among people unconnected with the royal household, and its definition of "verge" went somewhat beyond 12 miles. The prison was originally built to hold prisoners being tried by the Marshalsea Court and the Court of the King's Bench, to which Marshalsea rulings could be appealed, but its use was soon extended, and the term "Marshalsea" came to be used for the prison itself.

Southwark

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

around 43 CE. It served as an entry point into London from southern England, particularly along Watling Street

Watling Street

Watling Street is the name given to an ancient trackway in England and Wales that was first used by the Britons mainly between the modern cities of Canterbury and St Albans. The Romans later paved the route, part of which is identified on the Antonine Itinerary as Iter III: "Item a Londinio ad...

, the Roman road from Canterbury, which ran into Southwark's Borough High Street

Borough High Street

Borough High Street is a main street in Southwark, London running south-west from London Bridge, forming part of the A3 road, which runs from London to Portsmouth.- Overview :...

. As a result it became known for its travellers and inns, including Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer , known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey...

's Tabard Inn, and its population of criminals hiding out on the wrong side of the old London Bridge. The itinerant population brought with it poverty, prostitutes, bear baiting, theatres—including Shakespeare's Globe

Globe Theatre

The Globe Theatre was a theatre in London associated with William Shakespeare. It was built in 1599 by Shakespeare's playing company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men, and was destroyed by fire on 29 June 1613...

—and, inevitably, prisons. In 1796, there were five within its boundaries: the Clink

The Clink

The Clink was a notorious prison in Southwark, England which functioned from the 12th century until 1780 either deriving its name from, or bestowing it on, the local manor, the Clink Liberty . The manor and prison were owned by the Bishop of Winchester and situated next to his residence at...

, King's Bench Prison

King's Bench Prison

The King's Bench Prison was a prison in Southwark, south London, from medieval times until it closed in 1880. It took its name from the King's Bench court of law in which cases of defamation, bankruptcy and other misdemeanours were heard; as such, the prison was often used as a debtor's prison...

, the White Lion, the Borough Compter

Borough Compter

The Borough Compter was a small compter or prison initially located in Southwark High Street but moved to nearby Tooley Street in the 17th century, where it stood until demolished until 1855. It took its name from 'The Borough', a historic name for the Southwark area of London on the south side of...

, and the Marshalsea, compared to just 18 in London as a whole.

Debt in England

Fleet Prison

Fleet Prison was a notorious London prison by the side of the Fleet River in London. The prison was built in 1197 and was in use until 1844. It was demolished in 1846.- History :...

closed in 1842, some debtors were found to have been there for 30 years.

The law offered no protection for people with assets tied up by inheritance laws, or for those who had paid their creditors as much as they could. Because prisons were privately administered, whole economies were created around the debtor communities, with the prison keepers charging rent (the so-called "jailor's fee"), bailiffs charging for food and clothing, attorneys charging legal fees in fruitless efforts to get the debtors out, and creditors, often tradesmen, increasing the debt simply because the debtor was in jail. The result was that the prisoners' families, including children, often had to be sent to work simply to pay the costs of keeping their breadwinner in prison, the debts accumulating to the point where there was no realistic prospect of release.

According to a petition presented to parliament in 1641, around 10,000 people in England and Wales were in prison for debt. Legislation began to address the problem from 1649 onwards, though it was slow to make any real difference. Helen Small writes that, under George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

(1760–1820), new legislation prevented debts of under 40 shillings leading to jail—roughly £ today—but even the smallest amounts would quickly exceed that once lawyers' fees were added. Under the Insolvent Debtors Act 1813, debtors could request release after 14 days in jail by taking an oath that their assets did not exceed £20, but if any of their creditors objected, they had to stay inside. Even after a lifetime in prison, the debt remained to be paid.

Prisons in England

Stocks

Stocks are devices used in the medieval and colonial American times as a form of physical punishment involving public humiliation. The stocks partially immobilized its victims and they were often exposed in a public place such as the site of a market to the scorn of those who passed by...

, flogging, the pillory

Pillory

The pillory was a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, formerly used for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse, sometimes lethal...

, or the ducking stool. Before the United States Declaration of Independence

United States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence was a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies then at war with Great Britain regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire. John Adams put forth a...

in 1776, convicts were also sent to one of the American colonies

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were English and later British colonies established on the Atlantic coast of North America between 1607 and 1733. They declared their independence in the American Revolution and formed the United States of America...

, a process known as penal transportation

Penal transportation

Transportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

, often for the most minor offence. When that stopped, they started being held instead in disused ships called hulks

British prison hulks

Prison hulks were decommissioned ships that authorities used as floating prisons in the 18th and 19th centuries. They were especially popular in England. The term "prison hulk" is not synonymous with the related term, convict ship...

moored in the Thames, and at Plymouth and Portsmouth, with the intention that they would be transported somewhere at some point. According to The National Archives at Kew, the establishment of these hulks marked the first involvement of central government in Britain in the administration of prisons. In 1787, penal transportation to Australia

Convicts in Australia

During the late 18th and 19th centuries, large numbers of convicts were transported to the various Australian penal colonies by the British government. One of the primary reasons for the British settlement of Australia was the establishment of a penal colony to alleviate pressure on their...

began, lasting until 1867. A number of prisons were built by central government during this period to hold convicts awaiting transportation, most notably Millbank

Millbank Prison

Millbank Prison was a prison in Millbank, Pimlico, London, originally constructed as the National Penitentiary, and which for part of its history served as a holding facility for convicted prisoners before they were transported to Australia...

, built in 1816, but also Parkhurst

Parkhurst (HM Prison)

HMP Isle of Wight - Parkhurst Barracks is a prison situated in Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight, operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service.Parkhurst prison is one of the three prisons that make up HMP Isle of Wight, the other two being Camp Hill, and Albany...

(1838), Pentonville

Pentonville (HM Prison)

HM Prison Pentonville is a Category B/C men's prison, operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service. Pentonville Prison is not actually within Pentonville itself, but is located further north, on the Caledonian Road in the Barnsbury area of the London Borough of Islington, in inner-North London,...

(1842), Portland (1848), Portsmouth (1850), and Chatham (1856).

Prison reform gathered pace with the appointment of Sir Robert Peel

Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 December 1834 to 8 April 1835, and again from 30 August 1841 to 29 June 1846...

as Home Secretary in 1822. Before the Gaols Act 1823

Gaols Act 1823

The Gaols Act 1823 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that provided for improvements in the treatment of prisoners in the United Kingdom.-Overview:...

, then the Prisons Act of 1835 and 1877, prisons such as the Marshalsea were administered by the royal household, and run for profit almost entirely without regulation by private individuals who purchased the right to manage and make money from them. Prisoners had to feed and clothe themselves and furnish their rooms. If food was supplied, it was bread and water, or something confiscated from the local market as unfit for human consumption; anyone unfortunate enough to have no money for food, and no one to bring it in for him, simply died of starvation. Robert Hughes

Robert Hughes (critic)

Robert Studley Forrest Hughes, AO is an Australian-born art critic, writer and television documentary maker who has resided in New York since 1970.-Early life:...

writes that jailors assumed the right to chain prisoners with as many iron fetters

Fetters

Legcuffs, shackles, footcuffs, fetters or leg irons are a kind of physical restraint used on the feet or ankles to allow walking but prevent running and kicking. The term "fetter" shares a root with the word "foot"....

as they chose, charging for their removal one at a time, the so-called "trade of chains," a practice that survived into the 1790s. In the Bishop of Ely

Bishop of Ely

The Bishop of Ely is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Ely in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese roughly covers the county of Cambridgeshire , together with a section of north-west Norfolk and has its see in the City of Ely, Cambridgeshire, where the seat is located at the...

's prison, prisoners unable to pay for "easement of irons" were chained to the floor on their backs, with a spiked collar around the neck and heavy iron bars over the legs, until they somehow found the money.

Two buildings

Although the first Marshalsea survived for 500 years, and the second for just 38, it is the latter that became widely known, thanks largely to Charles Dickens. Trey Philpotts writes that every detail about the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit has a referent in the real Marshalsea of the 1820s. Dickens rarely made mistakes and did not exaggerate; if anything, he downplayed the licentiousness of Marshalsea life, perhaps to protect Victorian

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

sensibilities. Most of our information about the first Marshalsea comes from John Baptist Grano

John Baptist Grano

John Baptist Grano was a trumpeter, flutist, and composer based in London, England, who worked with George Frederick Handel at the opera house in the city's Haymarket....

(1692–ca. 1748), one of Handel's trumpeters at the opera house in Haymarket, who kept a detailed diary of his 458-day incarceration in the first Marshalsea—for a debt of £99 (worth £ today)—from 30 May 1728, until 23 September 1729.

First Marshalsea (ca. 1329–1811)

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer , known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey...

, by helping her daughter, Joan, marry their son, John, who was only 12 years old and did not have their consent

Age of consent

While the phrase age of consent typically does not appear in legal statutes, when used in relation to sexual activity, the age of consent is the minimum age at which a person is considered to be legally competent to consent to sexual acts. The European Union calls it the legal age for sexual...

.

Most of the first Marshalsea, as with the second, was taken up by debtors; in 1773, debtors within 12 miles of Westminster could be imprisoned there for a debt of 40 shillings. It also held a small number of men being tried at the Old Bailey

Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court in England and Wales, commonly known as the Old Bailey from the street in which it stands, is a court building in central London, one of a number of buildings housing the Crown Court...

for crimes at sea. The prison was technically under the control of the Knight Marshal

Knight Marshal

The Knight Marshal is a former office in the British Royal Household established by King Henry III in 1236. The position later became a Deputy to the Earl Marshal from the reign of Henry VIII until the office was abolished in 1846 ....

, but it was let out to private individuals who ran it for profit. In 1727, for example, the Knight Marshal, Sir Philip Meadows, hired John Darby, a printer, as prison governor, who in turn leased it illegally to William Acton, a butcher (see below). Acton paid Darby £140 a year—roughly £ in 2009—for the right to act as resident warden and chief turnkey, and an additional £260 for the right to collect rent from the rooms, and sell food and drink.

Master's Side

The prison had separate areas for its two classes of prisoner: the Master's Side, which housed about 50 rooms for rent, and the Common Side, consisting of nine small rooms into which 300 people were locked up from dusk until dawn. Room rents on the Master's Side were ten shillings a week in 1728, with most prisoners forced to share. (Ten shillings in 1728 is £58 in 2009 using the retail price index or £773 using average earnings.) John Grano paid 2s 6d—two shillings and six penniesPenny (British pre-decimal coin)

The penny of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, was in circulation from the early 18th century until February 1971, Decimal Day....

; £14 in 2009—for a room with two beds on the Master's Side, shared with three other prisoners: Daniel Blunt, a tailor who owed £9, Benjamin Sandford, a lighterman from Bermondsey

Bermondsey

Bermondsey is an area in London on the south bank of the river Thames, and is part of the London Borough of Southwark. To the west lies Southwark, to the east Rotherhithe, and to the south, Walworth and Peckham.-Toponomy:...

who owed £55, and a Mr. Blundell, a jeweller.

Turret

In architecture, a turret is a small tower that projects vertically from the wall of a building such as a medieval castle. Turrets were used to provide a projecting defensive position allowing covering fire to the adjacent wall in the days of military fortification...

ed lodge at the entrance, as with the older Oxbridge colleges, with a side room known as the Pound, where new prisoners would wait until a room was found for them. The courtyard leading out of the lodge was called the Park. It had been divided in two by a long, narrow wall, so that prisoners from the Common Side could spend their daylight hours there without being seen by those on the Master's Side, who preferred not to be distressed by the sight of abject poverty, especially when they might themselves be plunged into it at any moment. The wives, daughters, and lovers of male prisoners were allowed to live with them, so long as they behaved themselves and someone was paying their way. Women prisoners who could pay the fees were housed in the women's quarters, called "the Oak".

There was a bar run by the governor's wife, and a chandler's

Chandlery

A chandlery was originally the office in a medieval household responsible for wax and candles, as well as the room in which the candles were kept. It was headed by a chandler. The office was subordinated to the kitchen, and only existed as a separate office in larger households...

shop run in 1728 by a Mr and Mrs Cary, both prisoners, which sold candles, soap, and a little food. When John Howard

John Howard (prison reformer)

John Howard was a philanthropist and the first English prison reformer.-Birth and early life:Howard was born in Lower Clapton, London. His father, also John, was a wealthy upholsterer at Smithfield Market in the city...

(1726–1790), one of England's great 18th-century prison reformers, visited the Marshalsea on 16 March 1774, he found the shop being run by a man and his family who were not prisoners, and who were living in five of the rooms intended for inmates on the Master's Side. There was a coffee shop run in 1729 by a long-term prisoner, Sarah Bradshaw, and a chop-house called Titty Doll's, run by another prisoner, Richard McDonnell, and his wife. There was also a tailor and a barber, and prisoners from the Master's Side could hire prisoners from the Common Side to act as their servants.

Howard reported that there was no infirmary, and that the practice of "garnish" was in place (see below), whereby new prisoners were bullied into giving money to the older prisoners upon arrival. During his visit, the taproom, or beer room, had been let to a prisoner who was living "within the rules" of the King's Bench prison, which meant he was formally incarcerated in the King's Bench, but was allowed to live outside, within a certain radius of the prison, for a fee. Although legislation prohibited jailors from having a pecuniary interest in the sale of alcohol within their prisons, it was another rule that was completely ignored. Howard reported that 600 pots of beer were brought into the Marshalsea one Sunday from a public house

Public house

A public house, informally known as a pub, is a drinking establishment fundamental to the culture of Britain, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. There are approximately 53,500 public houses in the United Kingdom. This number has been declining every year, so that nearly half of the smaller...

, because the prisoners did not like the beer available in the taproom. Rioting and drunkenness were the only ways the prisoners could be made to "disregard the confinement," he wrote.

Common Side

By all accounts, living conditions were horrific. In 1639, prisoners complained that 23 women were being held in one room without space to lie down, leading to a revolt, with prisoners pulling down fences and attacking the guards with stones. Prisoners were regularly beaten with a "bull's pizzle", a whip made from a bull's penis, or tortured with thumbscrews and a skullcap, a vice

Vise

Vise may refer to:* Miami Vise, a defunct AFL team* Vise , a mechanical screw apparatus* Vise , an architectural element* Venus In-Situ Explorer * The Vise, TV show* Visé, BelgiumPeople with the surname Vise:...

for the head that weighed 12 lb (5.4 kg). What often finished them off was being forced to lie in the Strong Room, a windowless shed near the main sewer, next to cadaver

Cadaver

A cadaver is a dead human body.Cadaver may also refer to:* Cadaver tomb, tomb featuring an effigy in the form of a decomposing body* Cadaver , a video game* cadaver A command-line WebDAV client for Unix....

s awaiting burial, of which there was a plentiful supply. Dickens wrote of it that it was "dreaded by even the most dauntless highwaymen and bearable only to toads and rats". One diabetic army officer, ejected from the Common Side because other inmates had complained about the smell of his urine, was moved to the Strong Room, where he died; his face was eaten by rats within three or four hours of his death, according to a witness.

During the wardship of William Acton in the 1720s the income from charities, collected from various begging bowls in circulation around Southwark and intended to buy food for inmates on the Common Side, was directed instead to a small group of trusted prisoners who policed the prison on Acton's behalf. The same group swore during Acton's trial in 1729 for murder (see below) that the Strong Room was the best room in the house. Ginger writes that Acton and his wife, who lived in a comfortable apartment near the Lodge, knew they were sitting on a powder keg. "When each morning the smell of freshly baked bread filled ... the yard ... only brutal suppression could prevent the Common Side from erupting", he writes.

1729 Gaols Committee

Fleet Prison

Fleet Prison was a notorious London prison by the side of the Fleet River in London. The prison was built in 1197 and was in use until 1844. It was demolished in 1846.- History :...

who had been living in lodgings outside the jail "within the rules", was taken to a "sponging house" after he refused to pay a higher prison fee to the Fleet's notorious warden, Thomas Bambridge

Thomas Bambridge

Thomas Bambridge was a notorious warden of the Fleet Prison in England.Bambridge became warden of the Fleet in 1728. He had paid, with another person, £5000 to John Huggins for the wardenship...

. Sponging houses were private lodgings where prisoners were incarcerated before being taken to jail. They acquired the name because they squeezed the prisoner's last money out of him as if he were a sponge. When Castell arrived at the sponging house on 14 November he was forced to share space with a man who was dying of smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

, and as a result became infected and died less than a month later.

.jpg)

James Oglethorpe

James Edward Oglethorpe was a British general, member of Parliament, philanthropist, and founder of the colony of Georgia...

, a Tory MP who became known years later for founding the American colony of Georgia

Province of Georgia

The Province of Georgia was one of the Southern colonies in British America. It was the last of the thirteen original colonies established by Great Britain in what later became the United States...

. He began to ask questions about the treatment of debtor prisoners, which resulted in the appointment in February 1729 of a parliamentary committee, the Gaols Committee, which he chaired. The committee visited the Fleet on 27 February and the Marshalsea on 25 March. Commissioned by Sir Archibald Grant

Sir Archibald Grant, 2nd Baronet

Sir Archibald Grant , 2nd Baronet in his early life was a company specualtor and the Member of parliament for Aberdeenshire, 1722–1732...

(see image on the right; Grant is standing third from the right), William Hogarth

William Hogarth

William Hogarth was an English painter, printmaker, pictorial satirist, social critic and editorial cartoonist who has been credited with pioneering western sequential art. His work ranged from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like series of pictures called "modern moral subjects"...

accompanied the committee on its visit to the Fleet, sketching it, then later painting it in oil. The art historian Horace Walpole wrote of the painting in 1849: "The scene is the committee. On the table are the instruments of torture. A prisoner in rags, half-starved, appears before them. The poor man has a good countenance, that adds to the interest. On the other hand is the inhuman gaoler. It is the very figure that Salvator Rosa

Salvator Rosa

Salvator Rosa was an Italian Baroque painter, poet and printmaker, active in Naples, Rome and Florence. As a painter, he is best known as an "unorthodox and extravagant" and a "perpetual rebel" proto-Romantic.-Early life:...

would have drawn for Iago

Iago

Iago is a fictional character in Shakespeare's Othello . The character's source is traced to Giovanni Battista Giraldi Cinthio's tale "Un Capitano Moro" in Gli Hecatommithi . There, the character is simply "the ensign". Iago is a soldier and Othello's ancient . He is the husband of Emilia,...

in the moment of detection."

The committee was shocked by the prisoners' living conditions. They reported back to parliament that they had found, "the sale of offices, breaches of trust, enormous extortions, oppression, intimidation, gross brutalities, and the highest crimes and misdemeanours." In the Fleet they had found Sir William Rich, a baronet

Baronet

A baronet or the rare female equivalent, a baronetess , is the holder of a hereditary baronetcy awarded by the British Crown...

, in irons. Unable to pay the prison fee, Rich had apparently been burned with a red-hot poker, hit with a stick, and kept in a dungeon for ten days for having wounded the warden with a shoemaker's knife. In the Marshalsea they found that prisoners on the Common Side were being routinely starved to death:

All the Support such poor Wretches have to subsist on, is an accidental Allowance of Pease, given once a week by a Gentleman, who conceals his Name, and about Thirty Pounds of Beef, provided by the voluntary Contribution of the Judge and Officers of the Marshalsea, on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday; which is divided into very small Portions, of about an Ounce and a half, distributed with One-Fourth-part of an Half-penny Loaf ... When the miserable Wretch hath worn out the Charity of his Friends, and consumed the Money, which he hath raised upon his Cloaths, and Bedding, and hath eat his last Allowance of Provisions, he usually in a few Days grows weak, for want of Food, with the symptoms of a hectick Fever; and when he is no longer able to stand, if he can raise 3d to pay the Fee of the common Nurse of the Prison, he obtains the Liberty of being carried into the Sick Ward, and lingers on for about a Month or two, by the assistance of the above-mentioned Prison Portion of Provision, and then dies.

Not that being in the sick ward necessarily made the last month of life any easier:

Trial of William Acton

Frederick, Prince of Wales