Jules Dumont d'Urville

Encyclopedia

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

explorer, naval officer

French Navy

The French Navy, officially the Marine nationale and often called La Royale is the maritime arm of the French military. It includes a full range of fighting vessels, from patrol boats to a nuclear powered aircraft carrier and 10 nuclear-powered submarines, four of which are capable of launching...

and rear admiral, who explored the south and western Pacific, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

and Antarctica.

Childhood

Dumont was born at Condé-sur-NoireauCondé-sur-Noireau

Condé-sur-Noireau is a commune in the Calvados department in the Basse-Normandie region in northwestern France.It is situated on the Noireau River. In the fifteenth century, the town was occupied by the English, and belonged to Sir John Fastolf of Caister Castle in Norfolk...

. His father, Gabriel Charles François Dumont d’Urville and Bailiff

Bailiff

A bailiff is a governor or custodian ; a legal officer to whom some degree of authority, care or jurisdiction is committed...

of Condé-sur-Noireau

Condé-sur-Noireau

Condé-sur-Noireau is a commune in the Calvados department in the Basse-Normandie region in northwestern France.It is situated on the Noireau River. In the fifteenth century, the town was occupied by the English, and belonged to Sir John Fastolf of Caister Castle in Norfolk...

(1728–1796) was, like his ancestors, responsible for the court of Condé. His mother Jeanne Françoise Victoire Julie (1754–1832) came from Croisilles, Calvados

Croisilles, Calvados

Croisilles is a commune in the Calvados department in the Basse-Normandie region in northwestern France.-Population:...

and was a rigid and formal woman coming from an ancient family of the rural nobility of Basse-Normandie

Basse-Normandie

Lower Normandy is an administrative region of France. It was created in 1956, when the Normandy region was divided into Lower Normandy and Upper Normandy...

. He was weak and often sickly. After the death of his father when he was six, his mother’s brother, the Abbot of Croisilles, played the part of his father and from 1798 was in charge of his education. The Abbot taught him Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

, Greek

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

, rhetoric

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the facility of speakers or writers who attempt to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations. As a subject of formal study and a productive civic practice, rhetoric has played a central role in the Western...

and philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

.

From 1804 Dumont studied at the lycée Impérial in Caen

Caen

Caen is a commune in northwestern France. It is the prefecture of the Calvados department and the capital of the Basse-Normandie region. It is located inland from the English Channel....

.

In Caen’s library he began to read the encyclopédists

Encyclopédie

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It was edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert...

and the reports of travel of Bougainville

Louis Antoine de Bougainville

Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville was a French admiral and explorer. A contemporary of James Cook, he took part in the French and Indian War and the unsuccessful French attempt to defend Canada from Britain...

, Cook

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

and Anson

George Anson, 1st Baron Anson

Admiral of the Fleet George Anson, 1st Baron Anson PC, FRS, RN was a British admiral and a wealthy aristocrat, noted for his circumnavigation of the globe and his role overseeing the Royal Navy during the Seven Years' War...

, and he became deeply passionate about these matters. At the age of 17 years he failed the physical tests of the entrance exam to the École Polytechnique

École Polytechnique

The École Polytechnique is a state-run institution of higher education and research in Palaiseau, Essonne, France, near Paris. Polytechnique is renowned for its four year undergraduate/graduate Master's program...

and he therefore decided to enlist in the navy.

Early years in the navy

In 1807 Dumont was admitted to the Naval AcademyÉcole Navale

The École Navale is the French Naval Academy in charge of the education of the officers of the French Navy.The academy was founded in 1830 by the order of King Louis-Philippe...

at Brest

Brest, France

Brest is a city in the Finistère department in Brittany in northwestern France. Located in a sheltered position not far from the western tip of the Breton peninsula, and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an important harbour and the second French military port after Toulon...

where he presented himself as a timid young man, very serious and studious, little interested in amusements and much more interested in studies than in military matters. In 1808, he obtained the grade of first class candidate.

At the time the French navy was only a neglected "cousin", of a much lower quality than Napoleon's army

La Grande Armée

The Grande Armée first entered the annals of history when, in 1805, Napoleon I renamed the army that he had assembled on the French coast of the English Channel for the proposed invasion of Britain...

and its ships were blockaded in their ports by the absolute domination of the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

. Dumont was confined to land like his colleagues and spent the first years in the navy studying foreign languages. In 1812, after having been promoted to ensign

Ensign (rank)

Ensign is a junior rank of a commissioned officer in the armed forces of some countries, normally in the infantry or navy. As the junior officer in an infantry regiment was traditionally the carrier of the ensign flag, the rank itself acquired the name....

and finding himself bored with port life and disapproving of the dissolute behaviour of the other young officers, he asked to be transferred to Toulon

Toulon

Toulon is a town in southern France and a large military harbor on the Mediterranean coast, with a major French naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur region, Toulon is the capital of the Var department in the former province of Provence....

on board the Suffren; but this ship was also blockaded in port.

In this period Dumont built on his already substantial cultural knowledge. He already spoke, in addition to Latin and Greek, English, German, Italian, Russian, Chinese and Hebrew. During his later travels in the Pacific, thanks to his prodigious memory, he acquired some knowledge of an immense number of dialects of Polynesia

Polynesia

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of over 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are termed Polynesians and they share many similar traits including language, culture and beliefs...

and Melanesia

Melanesia

Melanesia is a subregion of Oceania extending from the western end of the Pacific Ocean to the Arafura Sea, and eastward to Fiji. The region comprises most of the islands immediately north and northeast of Australia...

. He learnt about botany

Botany

Botany, plant science, or plant biology is a branch of biology that involves the scientific study of plant life. Traditionally, botany also included the study of fungi, algae and viruses...

and entomology

Entomology

Entomology is the scientific study of insects, a branch of arthropodology...

in long excursions in the hills of Provence

Provence

Provence ; Provençal: Provença in classical norm or Prouvènço in Mistralian norm) is a region of south eastern France on the Mediterranean adjacent to Italy. It is part of the administrative région of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur...

and he studied in the nearby naval observatory

Observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geology, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed...

.

Finally Dumont undertook his first short navigation of the Mediterranean Sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

in 1814, when Napoleon had been exiled to Elba

Elba

Elba is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino. The largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago, Elba is also part of the National Park of the Tuscan Archipelago and the third largest island in Italy after Sicily and Sardinia...

. In 1816, he married Adélie Pepin, daughter of a clockmaker from Toulon, who was openly disliked by Dumont’s mother, who thought her inappropriate for her son and refused to meet her and, later on, her grandsons from the marriage.

In the Aegean Sea

In 1819 Dumont d'Urville sailed on board the Chevrette, under the command of Captain Gauttier-DuparcPierre Henri Gauttier Duparc

Pierre Henri Gauttier Duparc was a French Navy officer and admiral.Gauttier Duparc captained the Chevrette in 1819 during the travels of Jules Dumont d'Urville, where he contributed to the discovery of the Venus de Milo. His interest for naval chronometres earned him the nickname of "Gauttier...

, to carry out a hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore oil exploration/drilling and related disciplines. Strong emphasis is placed on soundings, shorelines, tides, currents, sea floor and submerged...

of the islands of the Greek archipelago. During a pause near the island of Milos

Milos

Milos , is a volcanic Greek island in the Aegean Sea, just north of the Sea of Crete...

, the local French representative brought to Dumont's attention the rediscovery of a marble statue a few days before (8 April 1820) by a local peasant

Peasant

A peasant is an agricultural worker who generally tend to be poor and homeless-Etymology:The word is derived from 15th century French païsant meaning one from the pays, or countryside, ultimately from the Latin pagus, or outlying administrative district.- Position in society :Peasants typically...

. The statue, now known as the Venus de Milo

Venus de Milo

Aphrodite of Milos , better known as the Venus de Milo, is an ancient Greek statue and one of the most famous works of ancient Greek sculpture. Created at some time between 130 and 100 BC, it is believed to depict Aphrodite the Greek goddess of love and beauty. It is a marble sculpture, slightly...

dates from around the year 130 BC. Dumont recognised its value and would have acquired it immediately, but the ship’s commander pointed out that there was not enough space on board for an object of its size. Moreover, the expedition was likely to proceed through stormy seas that could damage it. Dumont then wrote to the French ambassador to Constantinople

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

about its discovery. The Chevrette arrived in Constantinople on 22 April and Dumont succeeded in convincing the ambassador to acquire the statue.

Meanwhile, the peasant had sold the statue to a priest, Macario Verghis, who wished to present it as a gift to an interpreter for the Sultan

Sultan

Sultan is a title with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic language abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", and "dictatorship", derived from the masdar سلطة , meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be used as the title of certain rulers who...

in Constantinople. The French ambassador's representative arrived just as the statue was being loaded aboard a ship bound for Constantinople and persuaded the island's primates (chief citizens) to annul the sale and honour the first offer. This earned Dumont the title of Chevalier (knight

Knight

A knight was a member of a class of lower nobility in the High Middle Ages.By the Late Middle Ages, the rank had become associated with the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct for the perfect courtly Christian warrior....

) of the Légion d'honneur

Légion d'honneur

The Legion of Honour, or in full the National Order of the Legion of Honour is a French order established by Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the Consulat which succeeded to the First Republic, on 19 May 1802...

, the attention of the French Academy of Sciences

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research...

and promotion to lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

; and France gained a new, magnificent statue for the Louvre

Louvre

The Musée du Louvre – in English, the Louvre Museum or simply the Louvre – is one of the world's largest museums, the most visited art museum in the world and a historic monument. A central landmark of Paris, it is located on the Right Bank of the Seine in the 1st arrondissement...

in Paris

Voyage of the Coquille

On his return from the voyage of the Chevrette, Dumont was sent to the naval archiveArchive

An archive is a collection of historical records, or the physical place they are located. Archives contain primary source documents that have accumulated over the course of an individual or organization's lifetime, and are kept to show the function of an organization...

where he came across Lieutenant Louis Isidore Duperrey

Louis Isidore Duperrey

Louis Isidore Duperrey was a French sailor and explorer.Duperrey joined the navy in 1800, and served as marine hydrologist to Louis Claude de Saulces de Freycinet aboard the Uranie...

, an acquaintance from the past. The two began to plan an expedition of exploration in the Pacific, an area from which France had been forced out of during the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

. France considered it might be able to regain some of its losses by taking over part of New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

. In August 1822 the ship Coquille sailed from Toulon with the objective of collecting as much scientific and strategic information as possible on the area to which it was dispatched. Duperrey was named Commander of the expedition because he was four years older than Dumont.

René-Primevère Lesson

René-Primevère Lesson

René Primevère Lesson was a French surgeon, naturalist, ornithologist, and herpetologist.Lesson was born at Rochefort, and at the age of sixteen he entered the Naval Medical School there...

also travelled on the Coquille as a naval doctor and naturalist. On the return to France in March 1825, Lesson and Dumont brought back to France an imposing collection of animals and plants collected to the Falkland Islands

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands are an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean, located about from the coast of mainland South America. The archipelago consists of East Falkland, West Falkland and 776 lesser islands. The capital, Stanley, is on East Falkland...

, on the coasts of Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

and Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

, in the archipelagos of the Pacific and New Zealand, New Guinea

New Guinea

New Guinea is the world's second largest island, after Greenland, covering a land area of 786,000 km2. Located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, it lies geographically to the east of the Malay Archipelago, with which it is sometimes included as part of a greater Indo-Australian Archipelago...

and Australia. Dumont was now 35 and in poor health. On board the Coquille, he had behaved as a competent official, but rather abrupt, little inclined to socialise and with a sometimes embarrassing lack of interest in his physical condition and medical and hygiene advice. On the return to France, Duperrey was promoted to commander

Commander

Commander is a naval rank which is also sometimes used as a military title depending on the individual customs of a given military service. Commander is also used as a rank or title in some organizations outside of the armed forces, particularly in police and law enforcement.-Commander as a naval...

, while Dumont was promoted to a lower rank, even after having been on his best behaviour. This greatly disturbed Dumont in subsequent years.

Collection

On the Coquille, Dumont tried to reconcile his responsibilities as second in command with his need to carry out scientific work. He was in charge of carrying out research in the fields of the botany and entomology. The Coquille brought back to France specimens of more than 3,000 species of plants, 400 of which were previously unknown, enriching moreover the Muséum national d'histoire naturelleMuséum national d'histoire naturelle

The Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle is the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, France.- History :The museum was formally founded on 10 June 1793, during the French Revolution...

in Paris with more than 1,200 specimens of insects, covering 1,100 insect species (including 300 previously unknown species). The scientists Georges Cuvier

Georges Cuvier

Georges Chrétien Léopold Dagobert Cuvier or Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier , known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist...

and François Arago

François Arago

François Jean Dominique Arago , known simply as François Arago , was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer and politician.-Early life and work:...

analysed the results of his searches and praised Dumont.

The first voyage of the Astrolabe

Two months after Dumont returned on the Coquille, he presented to the Navy Ministry a plan for a new expedition, which he hoped to command, as his relationship with Duperrey had deteriorated. The proposal was accepted and the Coquille, renamed the AstrolabeFrench ship Astrolabe (1817)

The Astrolabe was a horse barge converted to an exploration ship of the French Navy. She is famous for her travels with Jules Dumont d'Urville.The name derives from an early navigational instrument, the astrolabe, a precursor to the sextant.-Legacy:...

in honour of the ship of La Pérouse

Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse

Jean François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse was a French Navy officer and explorer whose expedition vanished in Oceania.-Early career:...

, sailed from Toulon at the beginning of 1826 towards the Pacific Ocean, for a circumnavigation of the world that was destined to last nearly three years.

The new Astrolabe skirted the coast of southern Australia, carried out new relief maps of the South Island

South Island

The South Island is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand, the other being the more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman Sea, to the south and east by the Pacific Ocean...

of New Zealand, reached the archipelagos of Tonga

Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga , is a state and an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean, comprising 176 islands scattered over of ocean in the South Pacific...

and Fiji

Fiji

Fiji , officially the Republic of Fiji , is an island nation in Melanesia in the South Pacific Ocean about northeast of New Zealand's North Island...

, executed the first relief maps of the Loyalty Islands

Loyalty Islands

The Loyalty Islands are an archipelago in the Pacific. They are part of the French territory of New Caledonia, whose mainland is away. They form the Loyalty Islands Province , one of the three provinces of New Caledonia...

(part of French New Caledonia

New Caledonia

New Caledonia is a special collectivity of France located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, east of Australia and about from Metropolitan France. The archipelago, part of the Melanesia subregion, includes the main island of Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, the Belep archipelago, the Isle of...

) and explored the coasts of New Guinea

New Guinea

New Guinea is the world's second largest island, after Greenland, covering a land area of 786,000 km2. Located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, it lies geographically to the east of the Malay Archipelago, with which it is sometimes included as part of a greater Indo-Australian Archipelago...

. He identified the site of La Pérouse’s shipwreck in Vanikoro

Vanikoro

Vanikoro is an island from the Santa Cruz group, located 118 km to the Southeast of the main Santa Cruz group. It belongs administratively to the Temotu Province of the Solomon Islands....

(one of the Santa Cruz Islands

Santa Cruz Islands

The Santa Cruz Islands are a group of islands in the Pacific Ocean, part of Temotu Province of the Solomon Islands. They lie approximately 250 miles to the southeast of the Solomon Islands Chain...

, part of the archipelago of the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is a sovereign state in Oceania, east of Papua New Guinea, consisting of nearly one thousand islands. It covers a land mass of . The capital, Honiara, is located on the island of Guadalcanal...

) and collected numerous remains of his boats. The voyage continued with the mapping of part of the Caroline Islands

Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia in the eastern part of the group, and Palau at the extreme western end...

and the Moluccas. The Astrolabe returned to Marseille during the early months of 1829 with an impressive load of hydrographical papers and collections of zoological, botanical and mineralogical reports, which were destined to strongly influence the scientific analysis of those regions. Following this expedition, he invented the terms Malaisia, Micronesia

Micronesia

Micronesia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising thousands of small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It is distinct from Melanesia to the south, and Polynesia to the east. The Philippines lie to the west, and Indonesia to the southwest....

and Melanesia

Melanesia

Melanesia is a subregion of Oceania extending from the western end of the Pacific Ocean to the Arafura Sea, and eastward to Fiji. The region comprises most of the islands immediately north and northeast of Australia...

, distinguishing these Pacific cultures and island groups from Polynesia

Polynesia

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of over 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are termed Polynesians and they share many similar traits including language, culture and beliefs...

.

Dumont's health was by now weakened by years of a poor diet.

He suffered from kidney and stomach problems and from intense attacks of gout. During the first thirteen years of their marriage, half of which passed far apart, Adéle and Jules had two sons. The first one died at a young age while his father was to board the Coquille and the second, also called Jules, on the return of his father after four years away.

Dumont d’Urville passed a short period with his family before returning to Paris, where he was promoted to captain and he was put in charge of writing the report of his travels. The five volumes were published at the expense of the French government between 1832 and 1834. During these years d’Urville, who was already a poor diplomat, became more irascible and rancorous as a result of his gout, and lost the sympathy of the naval leadership. In his report, he criticised harshly the military structures, his colleagues, the French Academy of Sciences

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research...

and even the King

Louis-Philippe of France

Louis Philippe I was King of the French from 1830 to 1848 in what was known as the July Monarchy. His father was a duke who supported the French Revolution but was nevertheless guillotined. Louis Philippe fled France as a young man and spent 21 years in exile, including considerable time in the...

- none of which, in his opinion, had given the voyage of the Astrolabe due acknowledgment.

In 1835, Dumont was directed to return to Toulon to engage in “down to earth” work and spent two years, marked by mournful events (notably the loss of a daughter from cholera) and happy events (notably the birth of another son, Émile) but with the constant and nearly obsessive thought of a third expedition to the Pacific, analogous to James Cook's third voyage. He looked again at the Astrolabe’s travel notes, and found a gap in the exploration of Oceania and, in January 1837, he wrote to the Navy Ministry suggesting the opportunity for a new expedition to the Pacific.

The second voyage of the Astrolabe

King Louis-PhilippeLouis-Philippe of France

Louis Philippe I was King of the French from 1830 to 1848 in what was known as the July Monarchy. His father was a duke who supported the French Revolution but was nevertheless guillotined. Louis Philippe fled France as a young man and spent 21 years in exile, including considerable time in the...

approved the plan, but he ordered that the expedition aim for the South Magnetic Pole

South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is one of the two points where the Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on the surface of the Earth and lies on the opposite side of the Earth from the North Pole...

and to claim it for France; if that was not possible, Dumont’s expedition was asked to equal the most southerly latitude of 74°34'S achieved in 1823 by James Weddell

James Weddell

James Weddell was a British sailor, navigator and seal hunter who in the early Spring of 1823 sailed to latitude of 74°15' S and into a region of the Southern Ocean that later became known as the Weddell Sea.-Early life:He entered the merchant service very...

. Thus France became part of the international competition for polar exploration, along with the United States and the United Kingdom.

Dumont was initially unhappy with the modifications made to his proposal. He had little interest in polar exploration and preferred tropical routes. But soon his vanity took over and he saw the opportunity for achieving a prestigious objective. The two ships, Astrolabe and Zélée, commanded by Charles Hector Jacquinot, were prepared for the voyage at Toulon. In the course of the preparation Dumont also went to London to acquire documentation and instrumentation, meeting the British Admiralty’s oceanographer, Francis Beaufort

Francis Beaufort

Rear-Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort, FRS, FRGS was an Irish hydrographer and officer in Britain's Royal Navy...

and the President of the Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

, John Washington, both strong supporters of the British expeditions to the South Pole.

First contact with Antarctica

Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha Coast, Queen Maud Land. To the east of Cape Norvegia is...

; to pass through the Strait of Magellan

Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan comprises a navigable sea route immediately south of mainland South America and north of Tierra del Fuego...

; to travel up the coast of Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

in order to head for Oceania with the objective of inspecting the new British colonies in Western Australia; to sail to Hobart

Hobart

Hobart is the state capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Founded in 1804 as a penal colony,Hobart is Australia's second oldest capital city after Sydney. In 2009, the city had a greater area population of approximately 212,019. A resident of Hobart is known as...

; and to sail to New Zealand to find opportunities for French whalers and to examine places where a penal colony

Penal colony

A penal colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general populace by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory...

might be established. After passing through the East Indies

East Indies

East Indies is a term used by Europeans from the 16th century onwards to identify what is now known as Indian subcontinent or South Asia, Southeastern Asia, and the islands of Oceania, including the Malay Archipelago and the Philippines...

, the mission would have to round the Cape of Good Hope

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa.There is a misconception that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Africa, because it was once believed to be the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In fact, the...

and return in France.

Early in the voyage, part of the crew was involved in a drunken brawl and arrested in Tenerife

Tenerife

Tenerife is the largest and most populous island of the seven Canary Islands, it is also the most populated island of Spain, with a land area of 2,034.38 km² and 906,854 inhabitants, 43% of the total population of the Canary Islands. About five million tourists visit Tenerife each year, the...

. A short pause was made in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro , commonly referred to simply as Rio, is the capital city of the State of Rio de Janeiro, the second largest city of Brazil, and the third largest metropolitan area and agglomeration in South America, boasting approximately 6.3 million people within the city proper, making it the 6th...

to disembark a sick official. During the first part of the voyage there were also problems of provisioning, particularly rotten meat, which affected the health of the crew. At the end of November, the ships reached the Strait of Magellan. Dumont thought there was sufficient time to explore the strait for three weeks, taking into account the precise maps drawn by Phillip Parker King in the HMS Beagle

HMS Beagle

HMS Beagle was a Cherokee-class 10-gun brig-sloop of the Royal Navy. She was launched on 11 May 1820 from the Woolwich Dockyard on the River Thames, at a cost of £7,803. In July of that year she took part in a fleet review celebrating the coronation of King George IV of the United Kingdom in which...

between 1826 and 1830, before heading south again.

Two weeks after seeing their first iceberg

Iceberg

An iceberg is a large piece of ice from freshwater that has broken off from a snow-formed glacier or ice shelf and is floating in open water. It may subsequently become frozen into pack ice...

, the Astrolabe and the Zélée found themselves entangled again in a mass of ice on 1 January 1838. The same night the pack ice prevented the ships from continuing to the south. In the next two months Dumont lead increasingly desperate attempts to find a passage through the ice so that he could reach the desired latitude. For a while the ships managed to keep to an ice-free channel, but shortly afterwards they became trapped again, after a wind change. Five days of continuous work were necessary in order to open a corridor in the pack ice to free them.

After reaching the South Orkney Islands

South Orkney Islands

The South Orkney Islands are a group of islands in the Southern Ocean, about north-east of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. They have a total area of about ....

, the expedition headed directly to the South Shetland Islands and the Bransfield Strait

Bransfield Strait

Bransfield Strait is a body of water about wide extending for in a general northeast-southwest direction between the South Shetland Islands and Antarctic Peninsula. It was named in about 1825 by James Weddell, Master, Royal Navy, for Edward Bransfield, Master, RN, who charted the South Shetland...

. In spite of thick fog they located some land only sketched on the maps, which Dumont named Terre de Louis-Philippe (now called Graham Land

Graham Land

Graham Land is that portion of the Antarctic Peninsula which lies north of a line joining Cape Jeremy and Cape Agassiz. This description of Graham Land is consistent with the 1964 agreement between the British Antarctic Place-names Committee and the US Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names, in...

), the Joinville Island group

Joinville Island group

Joinville Island group is a group of antarctic islands, lying off the northeastern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, from which Joinville Island group is separated by the Antarctic Sound. Joinville Island, being located at , is the largest island of the Joinville Island group...

and Rosamel Island (now called Andersson Island

Andersson Island

Andersson Island, once known as Rosamel Island, is an island located at the eastern end of the Tabarin Peninsula, Antarctica.The island was first named by the French Antarctic Expedition in 1838, who called it le Rosamel in honor of Vice Admiral Claude Charles Marie du Campe de Rosamel, French...

). Conditions on board had rapidly deteriorated: most of the crew had obvious symptoms of scurvy and the main decks were covered by smoke from the ships fires and bad smells and became unbearable. At the end of February 1838, Dumont accepted that he was not able to continue further south, and he continued to doubt the actual latitude reached by Weddell. He therefore directed the two ships towards Talcahuano

Talcahuano

Talcahuano is a port city and commune in the Biobío Region of Chile. It is part of the Greater Concepción conurbation. Talcahuano is located in the south of the Central Zone of Chile.-Geography:...

, in Chile, where he established a temporary hospital for the crew members affected by scurvy.

The Pacific

During the months of exploration of the Pacific were ports of call on various islands in Polynesia. On their arrival in the Marquesas IslandsMarquesas Islands

The Marquesas Islands enana and Te Fenua `Enata , both meaning "The Land of Men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in the southern Pacific Ocean. The Marquesas are located at 9° 00S, 139° 30W...

, the crews found ways "to socialise" with the islanders. Dumont's moral conduct was irreproachable, but he provided a highly summarised description of some incidents of their stay in Nuku Hiva

Nuku Hiva

Nuku Hiva is the largest of the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. It was formerly also known as Île Marchand and Madison Island....

in his reports. During the voyage from the East Indies

East Indies

East Indies is a term used by Europeans from the 16th century onwards to identify what is now known as Indian subcontinent or South Asia, Southeastern Asia, and the islands of Oceania, including the Malay Archipelago and the Philippines...

to Tasmania

Tasmania

Tasmania is an Australian island and state. It is south of the continent, separated by Bass Strait. The state includes the island of Tasmania—the 26th largest island in the world—and the surrounding islands. The state has a population of 507,626 , of whom almost half reside in the greater Hobart...

some of the crew were lost to tropical fevers and dysentery

Dysentery

Dysentery is an inflammatory disorder of the intestine, especially of the colon, that results in severe diarrhea containing mucus and/or blood in the faeces with fever and abdominal pain. If left untreated, dysentery can be fatal.There are differences between dysentery and normal bloody diarrhoea...

(14 men and 3 officials); but for Dumont the worst moment during the expedition was at Valparaiso

Valparaíso

Valparaíso is a city and commune of Chile, center of its third largest conurbation and one of the country's most important seaports and an increasing cultural center in the Southwest Pacific hemisphere. The city is the capital of the Valparaíso Province and the Valparaíso Region...

, where he received a letter from his wife that informed him of the death of his second son from cholera. Adéle’s sorrowful demand that he return home, coincided with a deterioration in his health: Dumont was more and more often hit by attacks of gout and stomach pains.

On 12 December 1839 the two corvettes landed at Hobart

Hobart

Hobart is the state capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Founded in 1804 as a penal colony,Hobart is Australia's second oldest capital city after Sydney. In 2009, the city had a greater area population of approximately 212,019. A resident of Hobart is known as...

, where the sick and the dying were treated. Dumont was received by John Franklin

John Franklin

Rear-Admiral Sir John Franklin KCH FRGS RN was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. Franklin also served as governor of Tasmania for several years. In his last expedition, he disappeared while attempting to chart and navigate a section of the Northwest Passage in the Canadian Arctic...

, Governor of Tasmania and an Arctic

Arctic

The Arctic is a region located at the northern-most part of the Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean and parts of Canada, Russia, Greenland, the United States, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland. The Arctic region consists of a vast, ice-covered ocean, surrounded by treeless permafrost...

explorer, from whom he learned that the ships of the American expedition led by Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes was an American naval officer and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842 and commanded the ship in the Trent Affair during the American Civil War...

were berthed in Sydney waiting to sail south.

Seeing the consistent reduction of the crews, decimated by misfortunes, Dumont expressed his intention to leave this time for the Antarctic with the Astrolabe only, in order to attempt reach the South Magnetic Pole around longitude 140°. A deeply wounded Captain Jacquinot urged the hiring of a number of replacements (generally deserters from a French whaler

Whaler

A whaler is a specialized ship, designed for whaling, the catching and/or processing of whales. The former included the whale catcher, a steam or diesel-driven vessel with a harpoon gun mounted at its bows. The latter included such vessels as the sail or steam-driven whaleship of the 16th to early...

anchored in Hobart) and convinced him to reconsider his intentions; the Astrolabe and the Zelée both left Hobart on 1 January 1840. Dumont’s plan was very simple: to head south, wind conditions allowing.

Turning south

The first days of the voyage mainly involved the crossing of twenty degrees and a westerly current; on board there were further misfortunes, including the loss of a man. Crossing the 50°S parallel, they experienced unexpected falls in the air and water temperatures. After completing the crossing of the Antarctic ConvergenceAntarctic Convergence

The Antarctic Convergence is a curve continuously encircling Antarctica where cold, northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the relatively warmer waters of the subantarctic. Antarctic waters predominantly sink beneath subantarctic waters, while associated zones of mixing and upwelling create a zone...

, on 16 January, at 60°S they sighted the first iceberg and two days later the ships found themselves in the middle of a mass of ice. On 19 January the expedition crossed the Antarctic Circle

Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is one of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of the Earth. For 2011, it is the parallel of latitude that runs south of the Equator.-Description:...

, with celebrations similar to crossing of the Equator ceremonies

Line-crossing ceremony

The ceremony of Crossing the Line is an initiation rite in the Royal Navy, U.S. Navy, U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Marine Corps, and other navies that commemorates a sailor's first crossing of the Equator. Originally, the tradition was created as a test for seasoned sailors to ensure their new shipmates...

, and they sighted land the same afternoon.

The two ships slowly sailed to the West, skirting walls of ice, and on the afternoon of 21 January some members of the crew disembarked on a rocky island and hoisted the French tricolour

Flag of France

The national flag of France is a tricolour featuring three vertical bands coloured royal blue , white, and red...

. Dumont named it Pointe Géologie and the land beyond, Terre Adélie (Adélie Land

Adélie Land

Adélie Land is the portion of the Antarctic coast between 136° E and 142° E , with a shore length of 350 km and with its hinterland extending as a sector about 2,600 km toward the South Pole. It is claimed by France as one of five districts of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands, although not...

).

In the following days the expedition followed what was presumed to be the coast. They sighted the American schooner

Schooner

A schooner is a type of sailing vessel characterized by the use of fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts with the forward mast being no taller than the rear masts....

Porpoise of the United States Exploring Expedition

United States Exploring Expedition

The United States Exploring Expedition was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States from 1838 to 1842. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones. The voyage was authorized by Congress in...

commanded by Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes was an American naval officer and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842 and commanded the ship in the Trent Affair during the American Civil War...

, but it made an evasive manoeuvre and disappeared into the fog. On 1 February, Dumont decided to turn to the north heading for Hobart, which the two ships reached 17 days later. They were present for the arrival of the two ships of James Ross

James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross , was a British naval officer and explorer. He explored the Arctic with his uncle Sir John Ross and Sir William Parry, and later led his own expedition to Antarctica.-Arctic explorer:...

’s expedition to Antarctica.

On 25 February, the schooners sailed towards the Auckland Islands

Auckland Islands

The Auckland Islands are an archipelago of the New Zealand Sub-Antarctic Islands and include Auckland Island, Adams Island, Enderby Island, Disappointment Island, Ewing Island, Rose Island, Dundas Island and Green Island, with a combined area of...

, where they carried out magnetic measurements and they left a commemorative plate of their visit (as had the commander of the Porpoise previously), in which they announced the discovery of the South Magnetic Pole. They returned via New Zealand, the Torres Strait

Torres Strait

The Torres Strait is a body of water which lies between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is approximately wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost continental extremity of the Australian state of Queensland...

, Timor

Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, north of the Timor Sea. It is divided between the independent state of East Timor, and West Timor, belonging to the Indonesian province of East Nusa Tenggara. The island's surface is 30,777 square kilometres...

, Réunion

Réunion

Réunion is a French island with a population of about 800,000 located in the Indian Ocean, east of Madagascar, about south west of Mauritius, the nearest island.Administratively, Réunion is one of the overseas departments of France...

, Saint Helena

Saint Helena

Saint Helena , named after St Helena of Constantinople, is an island of volcanic origin in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the British overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha which also includes Ascension Island and the islands of Tristan da Cunha...

and finally Toulon, returning on 6 November 1840, the last French expedition of exploration to sail.

Return to France

Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a naval commissioned officer rank above that of a commodore and captain, and below that of a vice admiral. It is generally regarded as the lowest of the "admiral" ranks, which are also sometimes referred to as "flag officers" or "flag ranks"...

and was awarded the gold medal of the French Société de Géographie

Société de Géographie

The Société de Géographie , is the world's oldest geographical society. It was founded in 1821 . Since 1878, its headquarters has been at 184 Boulevard Saint-Germain, Paris. The entrance is marked by two gigantic caryatids representing Land and Sea...

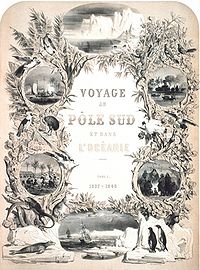

(Geographical Society); he later became its president. He then took over the writing of the report of the expedition, Voyage au pôle Sud et dans l'Océanie sur les corvettes l'Astrolabe et la Zélée 1837-1840, which were published between 1841 and 1854 in 24 volumes, plus seven more volumes with illustrations and maps.

Death and legacy

On 8 May 1842 Dumont and his family boarded a train from Versailles to Paris after seeing water games celebrating the king. Near MeudonMeudon

Meudon is a municipality in the southwestern suburbs of Paris, France. It is in the département of Hauts-de-Seine. It is located from the center of Paris.-Geography:...

the train’s locomotive

Locomotive

A locomotive is a railway vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. The word originates from the Latin loco – "from a place", ablative of locus, "place" + Medieval Latin motivus, "causing motion", and is a shortened form of the term locomotive engine, first used in the early 19th...

derailed, the wagons rolled and the tender

Tender locomotive

A tender or coal-car is a special rail vehicle hauled by a steam locomotive containing the locomotive's fuel and water. Steam locomotives consume large quantities of water compared to the quantity of fuel, so tenders are necessary to keep the locomotive running over long distances. A locomotive...

’s coal ended up on the front of the train and caught fire. Dumont's whole family died in the flames of the first French railway disaster, generally known as the Versailles train crash

Versailles train crash

The Versailles rail accident occurred on May 8, 1842 in the cutting at Meudon Bellevue , France. Following the King's fete celebrations at the Palace of Versailles, a train returning to Paris crashed at Meudon after the leading locomotive broke an axle. The carriages behind piled into the wrecked...

. Dumont's remains were identified by Dumontier, doctor on board the Astrolabe and a phrenologist

Phrenology

Phrenology is a pseudoscience primarily focused on measurements of the human skull, based on the concept that the brain is the organ of the mind, and that certain brain areas have localized, specific functions or modules...

.

Montparnasse

Montparnasse is an area of Paris, France, on the left bank of the river Seine, centred at the crossroads of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and the Rue de Rennes, between the Rue de Rennes and boulevard Raspail...

in Paris.

This tragedy led to the end of the practice in France of locking passengers in their train compartments.

He is the author of The New Zealanders: A story of Austral lands - likely to be the first novel written about fictional Maori characters.

Later, in honour of his many valuable chartings, the D'Urville Sea

D'Urville Sea

D'Urville Sea is a sea of the Southern Ocean, north of the coast of Adélie Land, East Antarctica. It is named after the French explorer and officer Jules Dumont d'Urville....

off Antarctica; D'Urville Island

D'Urville Island, Antarctica

D'Urville Island is an island of Antarctica. It is the northernmost island of the Joinville Island group, long, lying immediately north of Joinville Island, from which it is separated by Larsen Channel...

in the Joinville Island group

Joinville Island group

Joinville Island group is a group of antarctic islands, lying off the northeastern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, from which Joinville Island group is separated by the Antarctic Sound. Joinville Island, being located at , is the largest island of the Joinville Island group...

in Antarctica; Cape d'Urville, Irian Jaya, Indonesia

Indonesia

Indonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

; Mount D'Urville

Mount D'Urville

Mount D'Urville is the highest point on Auckland Island, one of New Zealand's subantarctic outlying islands, and is named after French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville. It rises to a height of 630 m . It stands in the southeast of the main island, overlooking the mouth of Carnley Harbour...

, Auckland Island

Auckland Island

Auckland Island is the main island of the Auckland Islands, an uninhabited archipelago in the south Pacific Ocean belonging to New Zealand. It is inscribed in the together with the other subantarctic New Zealand islands in the region as follows: 877-004 Auckland Isls, New Zealand S50.29 E165.52...

; and D'Urville Island

D'Urville Island, New Zealand

D'Urville Island is an island in the Marlborough Sounds along the northern coast of the South Island of New Zealand. It was named after the French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville. With an area of approximately , it is the eighth-largest island of New Zealand, and has around 52 permanent...

in New Zealand were named after him. The Dumont d'Urville Station

Dumont d'Urville Station

The Dumont d'Urville Station is a French scientific station located in Antarctica on Île des Pétrels, archipelago of Pointe Géologie in Adélie Land. It is named after explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville...

on Antarctica is also named after him, as is the Rue Dumont d'Urville, a street near the Champs-Élysées

Champs-Élysées

The Avenue des Champs-Élysées is a prestigious avenue in Paris, France. With its cinemas, cafés, luxury specialty shops and clipped horse-chestnut trees, the Avenue des Champs-Élysées is one of the most famous streets and one of the most expensive strip of real estate in the world. The name is...

in Paris' 8th district

VIIIe arrondissement

The 8th arrondissement of Paris is one of the 20 arrondissements of the capital city of France.Situated on the right bank of the River Seine and centred on the Opéra, the 8th is, together with the 1st and 9th arrondissements and 16th arrondissement and 17th arrondissement, one of Paris's main...

.

A French naval transport ship employed in French Polynesia is named after him; as was a 1931 sloop

Sloop

A sloop is a sail boat with a fore-and-aft rig and a single mast farther forward than the mast of a cutter....

which served in World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.