.gif)

History of Ireland (1801–1922)

Encyclopedia

The whole island of Ireland formed a constituent part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

from 1801 to 1922. For almost all of this period, Ireland was governed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom

in London through its Dublin Castle administration in Ireland

. Ireland faced considerable economic difficulties in the 19th century, including the Great Famine of the 1840s. The late 19th century and early 20th century saw a vigorous campaign for Irish Home Rule. While legislation enabling Irish Home Rule was eventually passed, vigorous and armed opposition from Irish unionists, particularly in Ulster, opposed it. Proclamation was shelved for the duration following the outbreak of the Great War. By 1918, however, moderate nationalism

had been eclipsed by militant republican separatism. Ulster Unionism was adamantly opposed to its implementation.

Ireland opened the 19th century still reeling from the after effects of the Irish Rebellion of 1798

Ireland opened the 19th century still reeling from the after effects of the Irish Rebellion of 1798

. Prisoners were still being deported to Australia and sporadic violence continued in county Wicklow

. There was another abortive rebellion led by Robert Emmet

in 1803. The Act of Union, which constitutionally made Ireland part of the British state can largely be seen as an attempt to redress the grievances of the 1798 rising and to prevent it from destabilising Britain or providing a base for foreign invasion.

In 1800 the Irish Parliament

and the Parliament of Great Britain

passed the Act of Union

which, from 1 January 1801, abolished the Irish legislature, and merged the Kingdom of Ireland

and the Kingdom of Great Britain

to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

. After one failed attempt, the passage of the act in the Irish parliament was finally achieved, albeit with the mass bribery of members of both houses, who were awarded British and United Kingdom peerage

s and other "encouragements".

In this period, Ireland was governed by authorities appointed in Great Britain. These were the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

, who was appointed by the King and the Chief Secretary for Ireland

appointed by the British Prime Minister. As the century went on, the British Parliament took over from the monarch as the executive as well as legislative branch of government. For this reason, in Ireland, the Chief Secretary became more important than the Lord Lieutenant, who became of more symbolic than real importance. After the abolition of the Irish Parliament, Irish Members of Parliament were elected to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in Westminster. The British Administration in Ireland

– known by metonymy

as "Dublin Castle

" – remained largely dominated by the Anglo-Irish establishment until the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922.

Part of the Union's attraction for many Irish Catholics was the promised abolition of the remaining Penal Laws then in force (which discriminated against Roman Catholics

), and the granting of Catholic Emancipation

. However King George III

blocked emancipation, believing that to grant it would break his coronation oath to defend the Anglican

church. A campaign under the Irish Catholic lawyer and politician Daniel O'Connell

and the Catholic Association

led to renewed agitation for the abolition of the Test Act

. Arthur Wellesley, the First Duke of Wellington, the Anglo Irish soldier and statesman, was at the peak of his enormous prestige as the victor of the Napoleonic Wars. As Prime Minister he used his considerable political power and influence to steer the enabling legislation through the U.K. Parliament. He then persuaded King George IV to sign the Act into in law under threat of resignation. The Catholic Relief Act 1829

, allowed British and Irish Catholics to sit in the Parliament. Daniel O'Connell became the first Catholic M.P. to be seated since 1689. As head of the Repeal Association

, O'Connell mounted an unsuccessful campaign for the repeal of the Act of Union and the restoration of Irish self-government. O'Connell's tactics were largely peaceful, using mass rallies to show the popular support for his campaign. While O'Connell failed to gain repeal of the union, his efforts led to reforms in matters such as local government, and the Poor Laws.

Significant electoral reform acts s would enlarge the franchise throughout the U.K. in the ensuing century.

Despite O'Connell's peaceful methods, there was also a good deal of sporadic violence and rural unrest in the country in the first half of the 19th century. In Ulster

, there were repeated outbreaks of sectarian violence, such as the celebrated riot at Dolly's Brae, between Catholics and the nascent Orange Order

. Elsewhere, tensions between the rapidly growing rural population on one side and their landlords and the state on the other, gave rise to much agrarian violence and social unrest. Secret peasant societies such as the "Whiteboys

" and the "Ribbonmen" used sabotage and violence to intimidate landlords into better treatment of their tenants. The most sustained outbreak of violence was the "Tithe War

" of the 1830s, over the obligation of the mostly Catholic peasantry to pay tithes to the Protestant Church of Ireland

. The Royal Irish Constabulary

was set up in response to such violence to police rural areas.

Ireland underwent major highs and lows economically during the 19th century; from economic booms during the Napoleonic Wars

Ireland underwent major highs and lows economically during the 19th century; from economic booms during the Napoleonic Wars

and in the late 19th century (when it experienced a surge in economic growth unmatched until the 'Celtic Tiger

' boom of the 1990s), to severe economic downturns and a series of famines, the last threatening in 1879. The worst of these was the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849), in which about one million people died and another million emigrated.

Ireland's economic problems were in part the result of the small size of Irish landholdings and a large increase in the population in the years before the famine. In particular, both the law and social tradition provided for subdivision of land, with all sons inheriting equal shares in a farm, meaning that farms became so small that only one crop, potatoes, could be grown in sufficient amounts to feed a family. Furthermore, many estates, from whom the small farmers rented, were poorly run by absentee landlords and in many cases heavily mortgaged. Enclosures of land since the turn of the 19th century had also exacerbated the problem, and the extensive grazing of cattle had contributed to the smaller plots of land available to tenants to raise their crops.

In the new Whig government in Britain (from 1846), Charles Trevelyan

became assistant secretary to the Treasury, and largely responsible for the British government's response to the famine in Ireland.

When potato blight hit the island in 1845, much of the rural population was left without food. Unfortunately at this time, the then Prime Minister Lord John Russell adhered to a strict laissez-faire

economic policy, which maintained that further state intervention would have the whole country dependent on hand-outs, and that what was needed was for economic viability to be encouraged. Despite a net surplus of food produced locally in Ireland, it was exported to England and elsewhere. Public works schemes were set up but proved inadequate, and the situation became catstrophic when epidemics of typhoid, cholera and dysentery took hold. Enormous sums were raised all over the world by charities (Native Americans

sent supplies, as did the Ottoman Empire

, while Queen Victoria

personally gave the equivalent in modern money of €70,000). However the inadequate nature of the British government's initiatives led to a problem becoming a catastrophe; the class of cottiers or farm labourers was virtually wiped out.

Emigration was not uncommon in Ireland in the years preceding the famine. Between 1815–1845, Ireland had already established itself as the major supplier of overseas labour to Great Britain and America. However, emigration reached a peak during the famine, particularly in the years 1846–1855. The famine also saw increased emigration to Canada and assisted passages to Australia. Because of ongoing political tensions between the

US and the UK, the large and influential Irish American

diaspora

created, financed and encouraged the Irish independence movement. In 1858, the Irish Republican Brotherhood

(IRB, also known as the Fenians) was founded as a secret society dedicated to armed rebellion against the British. A related organisation formed in New York

was known as Clan na Gael

, which several times organised raids into the British Province of Canada

. While the Fenians had a considerable presence in rural Ireland, the Fenian Rising

launched in 1867 was a fiasco and was contained by police rather than the British military. Moreover, wider support for Irish republicanism

, in the face of harsh laws against sedition

, was minimal in Ireland in the period; as late as the 1860s, mass meetings of constitutional nationalists

ended with the singing of "God Save the Queen" while royal visits often drew cheering crowds.

tried to launch a rebellion

against British rule in 1848. This coincided with the worst years of the famine, however it was contained by Military action. William Smith O'Brien

, leader of the Confederates, failure to capture a party of police barricaded in widow McCormack's house, who were holding her children as hostages, marked the effective end of the revolt.". Though intermittent resistance continued till late 1849, O'Brien and his colleagues were quickly arrested. Originally sentenced to death, this sentence was later commuted to transportation to Van Diemen's Land, where they joined John Mitchel

In the wake of the famine, many thousands of Irish peasant farmers and labourers either died or left the country. Those who remained waged a long campaign for better rights for tenant farmers and ultimately for land re-distribution. This period, known as the "Land War

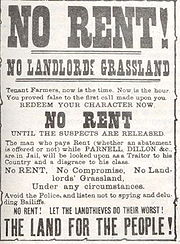

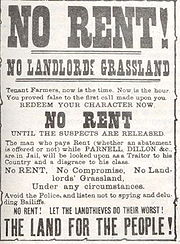

In the wake of the famine, many thousands of Irish peasant farmers and labourers either died or left the country. Those who remained waged a long campaign for better rights for tenant farmers and ultimately for land re-distribution. This period, known as the "Land War

" in Ireland, had a nationalist as well as a social element. The reason for this was that the land-owning class in Ireland, since the period of the 17th century Plantations of Ireland

, had been composed of Protestant settlers, originally from England, who had a British identity. The Irish (Roman Catholic) population widely believed that the land had been unjustly taken from their ancestors and given to this Protestant Ascendancy

during the English conquest of the country.

The Irish National Land League

, was formed to defend the interests of tenant farmers, at first demanding the "Three Fs

" – Fair rent, Free sale and Fixity of tenure. Members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

, such as Michael Davitt

, were prominent among the leadership of this movement. When they saw its potential for popular mobilisation, nationalist leaders such as Charles Stewart Parnell

also became involved.

The most effective tactic of the Land League was the boycott

(the word originates in Ireland in this period), where unpopular landlords were ostracised by the local community. Grassroots Land League members used violence against landlords and their property; attempted evictions of tenant farmers regularly turned into armed confrontations. Under the British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, an Irish Coercion Act

was first introduced – a form of martial law – to contain the violence. Parnell, Davitt, William O'Brien

and the other leaders of the Land League were temporarily imprisoned – being held responsible for the violence.

Ultimately, the land question was settled through successive Irish Land Acts by United Kingdom governments – beginning with the 1881 Act of William Ewart Gladstone

, which first gave extensive rights to tenant farmers, then the Wyndham

Land Purchase Act (1903) won by William O'Brien after the 1902 Land Conference

, enabling tenant farmers purchase their plots of land from their landlords, the problems of non-existent rural housing resolved by D.D. Sheehan under the Bryce

Labourers (Ireland) Act (1906). These acts created a very large class of small property owners in the Irish countryside, and dissipated the power of the old Anglo-Irish landed class.

Unrest and agitation also resulted in the successful introduction of agricultural co-operatives through the initiative of Horace Plunkett, but the most positive changes came after the introduction of the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898

which put the control and running of rural affairs into local hands. However it did not end support for independent Irish nationalism, as British governments had hoped. See also Irish Land Commission

.

underwent a massive change in the course of the 19th century. After the Famine, the Irish language

went into steep decline. This process was started in the 1820s, when the first National Schools were set up in the country. These had the advantage of encouraging literacy, but classes were provided only in English and the speaking of Irish was prohibited. However, before the 1840s, Irish was still the majority language in the country and numerically (given the rise in population) may have had more speakers than ever before. The Famine devastated the Irish speaking areas of the country, which tended also to be rural and poor. As well as causing the deaths of thousands of Irish speakers, the famine also led to sustained and widespread emigration from the Irish-speaking south and west of the country. By 1900, for the first time in perhaps two millennia, Irish was no longer the majority language in Ireland, and continued to decline in importance. By the time of Irish independence, the Gaeltacht

s had shrunk to small areas along the western seaboard.

In reaction, to this, Irish nationalists began a "Gaelic revival" in the late 19th century, hoping to revive the Irish language and Irish literature and sports. While social organisations such as the Gaelic League and the Gaelic Athletic Association

were very successful in attracting members, most of their activists were English speakers and the movement did not halt the decline of the Irish language.

The form of English established in Ireland differed somewhat from British English

and its variants. Blurring linguistic structures from older forms of English (notably Elizabethan English) and the Irish language, it is known as Hiberno-English

and was strongly associated with turn of the 20th century Celtic Revival

and Irish writers like J.M. Synge, George Bernard Shaw

, Sean O'Casey

, and had resonances in the English of Dublin-born Oscar Wilde

. Some nationalists saw the celebration of Hiberno-Irish by predominantly Anglo-Irish

writers as offensive "stage Irish

" caricature. Synge's play The Playboy of the Western World

was marked by rioting at performances.

and Conservatives

who belonged to the main British political parties. The Conservatives, for example, won a majority in the 1859 general election in Ireland. A significant minority also voted for Unionists, who resisted fiercely any dilution of the Act of Union. In the 1870s a former Conservative barrister turned nationalist

campaigner, Isaac Butt

, established a new moderate nationalist movement, the Home Rule League

. After his death, William Shaw

and in particular a radical young Protestant landowner, Charles Stewart Parnell

, turned the home rule movement, or the Irish Parliamentary Party

(IPP) as it became known, into a major political force. It came to dominate Irish politics, to the exclusion of the previous Liberal, Conservative and Unionist parties that had existed there. The party's growing electoral strength was first shown in the 1880 general election in Ireland, when it won 63 seats (two MPs later defected to the Liberals). By the 1885 general election in Ireland

it had won 86 seats (including one in the heavily Irish-populated English city of Liverpool

). Parnell's movement proved to be a broad one, from conservative landowners to the Land League

.

Parnell's movement also campaigned for the right of Ireland to govern herself as a region within the United Kingdom, in contrast to O'Connell who had wanted a complete repeal of the Act of Union. Two home rule bills (in 1886 and 1893) were introduced by Liberal Prime Minister

William Gladstone

, but neither became law. The issue divided Ireland: a significant minority of Unionists (largely though by no means exclusively based in Ulster

), but principally the revived radical Orange Order

opposed home rule, fearing that a Dublin parliament dominated by Catholics

and nationalists would discriminate against them and would impose tariffs on trade with Great Britain. (Whilst most of Ireland was primarily agricultural, north-east Ulster was the location of almost all the island's heavy industry and would have been affected by any tariff barriers imposed.)

In 1889, the scandal surrounding Parnell's divorce proceedings split the Irish party, when it became public that Parnell, popularly acclaimed as the 'Uncrowned King of Ireland', had for many years been living in a family relationship with Mrs. Katharine O'Shea, the long separated wife of a fellow MP. When the scandal broke, religious non-conformists in Great Britain, who were the backbone of the pro-Home Rule Liberal Party, forced its leader W. E. Gladstone to abandon support for the Irish cause as long as Parnell remained leader of the IPP. Parnell was subsequently deposed and died in 1891. But the Party and the country remained split between pro-Parnellites and anti-Parnellites

, who fought each other in elections.

The United Irish League

founded in 1898 forced the reunification of the party to stand under John Redmond

in the 1901 general election

. After a brief attempt by the Irish Reform Association

to introduce devolution

in 1904, the Irish Party subsequently held the balance of power in the House of Commons after the 1910 general election.

The last obstacle to achieving Home Rule was removed with the Parliament Act 1911

, when the House of Lords

lost its power to veto legislation and could only delay a bill for two years. In 1912, with the Irish Parliamentary Party at its zenith, a new third Home Rule Bill was introduced by Herbert Asquith, passing its first reading in the Imperial House of Commons

but again defeated in the House of Lords (as with the bill of 1893). During the following two years the threat of civil war hung over the island of Ireland, with the creation in 1913 of the Unionist Ulster Volunteers to resist Home Rule and of their nationalist counterparts the Irish Volunteers

to support Home Rule. These two groups armed themselves by importing thousands of rifles and rounds of ammunition from Imperial Germany and often drilled openly.

In 1914 the House of Commons finally passed the Third Home Rule Act 1914

, condemned by the dissident nationalists' All-for-Ireland League

party as a "partition deal

". On the sudden outbreak of the First World War

in August, the Act was suspended with a view to being implemented in 1915, at the end of what was expected to be a short war.

. It also possessed one of the world's biggest "red light districts" known as Monto

(after its focal point, Mountgomery Street, on the northside of the city).

Unemployment was high in Ireland and worker's pay and conditions were often very poor. In response to this, socialist activists such as James Larkin

and James Connolly

began to organise Trade Unions on syndicalist principles. Belfast

saw a bitter strike (by dockers organised by Larkin) in 1907 in which 10,000 workers went on strike and the police mutinied – a rare instance of non-sectarian mobilisation in Ulster. In Dublin there was an even more vicious dispute – the Dublin Lockout of 1913 – in which over 20,000 workers were fired for belonging to Larkin's Union. Three people died in the rioting that accompanied the lock-out and many more were injured.

However, the labour movement was split on nationalist lines. Southern unions formed the Irish Trade Union Congress

whereas those in Ulster affiliated themselves to British unions. Mainstream Irish nationalists were deeply opposed to social radicalism but socialist and labour activists found some sympathy among more extreme Irish Republicans

. James Connolly founded the Irish Citizen Army

to defend strikers from the police in 1913. In 1916 it participated in the Easter Rising

alongside the Irish Republican Brotherhood

and part of the Irish Volunteers

.

To resist Home Rule, thousands of unionists, led by the Dublin-born barrister Sir Edward Carson and James Craig

, signed the "Ulster Covenant

" of 1912, pledging to resist Home Rule. This movement also saw the setting up of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). In April 1914 30,000 German rifles with 3,000,000 rounds were landed at Larne

, with the authorities blockaded by the UVF (see Larne gunrunning). The Curragh Incident

showed it would be difficult to use the British army to coerce Ulster into home rule from Dublin. In response, Irish nationalists created the Irish Volunteers

, part of which later became the forerunner of the Irish Republican Army

(IRA) — to seek to ensure the passing of the Home Rule Bill

.

In September 1914, just as the First World War

broke out, the UK Parliament finally passed the Third Home Rule Act to establish self-government for Ireland, but was suspended for the duration of the war, expected to last only a year. In order to ensure the implementation of Home Rule after the war, nationalist leaders and the Irish Parliamentary Party

under Redmond supported Ireland's participation

with the British war effort and Allied cause

under the Triple Entente

against the expansion of the Central Powers

. The UVF and a majority of the Irish Volunteers who split off to form the National Volunteers

joined in their thousands their respective Irish regiments of the New British army

. A significant section of the Irish Volunteers

bitterly disagreed with the National Volunteers serving with the Irish Divisions.

The 10th (Irish) Division, the 16th (Irish) Division and the 36th (Ulster) Division suffered crippling losses in the trenches on the Western Front

, in Gallipoli

and the Middle East. Between 35,000 and 50,000 Irishmen (in all armies) are believed to have died in the War. Each side believed that, after the war, Great Britain would favour their respective goals of remaining fully part of the United Kingdom or becoming a self-governing United Ireland

within the union with the United Kingdom. Before the war ended, Britain made two concerted efforts to implement the Act, one in May 1916 after the Easter Rising

and again during 1917–1918, but during the Irish Convention

the Irish sides (Nationalist, Unionist) were unable to agree on terms for the temporary or permanent exclusion of Ulster

from its provisions. However, the combination of postponement of Home Rule and the involvement of Ireland with Great Britain in the war ("England's difficulty is Ireland's opportunity" as an old Republican saying went) provoked some on the radical fringes of Irish nationalism to resort to physical force.

Until 1918, the Irish Parliamentary Party who sought independent self-government for whole of Ireland through the principles of parliamentary constitutionalism, remained the dominant Irish party. But from the early 20th century, a radical fringe among Home Rulers became associated with militant republicanism

, particularly Irish-American republicanism. It was from the former Irish Volunteer ranks that the Irish Republican Brotherhood

organised an armed rebellion in 1916.

Because of divisions among the Volunteer leadership, only a small part of their numbers were mobilised. Indeed, Eoin MacNeill

Because of divisions among the Volunteer leadership, only a small part of their numbers were mobilised. Indeed, Eoin MacNeill

, the Volunteer commander, countermanded orders to units to begin the insurrection. Nevertheless, at Easter 1916, a small band of 1500 republican rebels (Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army) staged a rebellion, called the "Easter Rising

" in Dublin, under Padraig Pearse and James Connolly

. The Rising was put down after a week's fighting. Initially their acts were widely condemned by nationalists, who had suffered severe losses in the war as their sons fought at Gallipoli

during the Landing at Cape Helles, and on the Western Front

. Major newspapers such as the Irish Independent

and local authorities openly called for the execution of Pearse and the Rising's leadership. However the government's handling of the aftermath, and the execution of rebels and others in stages, ultimately led to widespread public sympathy for the rebels.

The government and the Irish media wrongly blamed Sinn Féin

, then a small monarchist political party with little popular support for the rebellion, even though in reality it had not been involved. Nonetheless Rising survivors, notably Éamon de Valera

returning from imprisonment in Great Britain, joined the party in great numbers, radicalised its programme and took control of its leadership.

Until 1917, Sinn Féin, under its founder Arthur Griffith

, had campaigned for a form of government championed first by O'Connell, namely that Ireland would become independent as a dual monarchy

with Great Britain, under a shared king. Such a system operated under Austria-Hungary

, where the same monarch, Emperor Charles I, reigned separately in both Austria and Hungary. Indeed Griffith in his book, The Resurrection of Hungary

, modelled his ideas on the manner in which Hungary had forced Austria to create a dual monarchy linking both states.

Faced with an impending split between its monarchists and republicans, a compromise was brokered at the 1917 Ard Fheis (party conference) whereby the party would campaign to create a republic, then let the people decide if they wanted a monarchy or republic, subject to the proviso that if they wanted a king, they could not choose someone from Britain's Royal Family.

Throughout 1917 and 1918, Sinn Féin and the Irish Parliamentary Party fought a bitter electoral battle; each won some by-elections and lost others. The scales were finally tipped in Sinn Féin's favour when as a result of the German Spring Offensive

the government, although it had already received large numbers of volunteer soldiers from Ireland, intended to impose conscription on the island linked with implementing Home Rule. An infuriated public turned against Britain during the Conscription Crisis of 1918. The Irish Parliamentary Party demonstratively withdrew its MPs from the House of Commons

at Westminster

.

In the December 1918 general election

, Sinn Féin won 73 out of 105 seats, 25 of which were uncontested. Sinn Féin's new MPs refused to sit in the British House of Commons. Instead on 21 January 1919 twenty-seven assembled as 'Teachta Dála

' (TDs) in the Mansion House

in Dublin and established Dáil Éireann

(a revolutionary Irish parliament). They proclaimed an Irish Republic

and attempted to establish a unilateral system of government.

For three years, from 1919 to 1921, acting largely on its own authority and independently of the Dáil assembly, the Irish Republican Army

For three years, from 1919 to 1921, acting largely on its own authority and independently of the Dáil assembly, the Irish Republican Army

(IRA), the army of the Irish Republic, engaged in guerrilla warfare

against the British army

and paramilitary police units known as the Black and Tans

and the Auxiliary Division

. Both sides engaged in brutal acts; the Black and Tans deliberately burned entire towns and tortured civilians. The IRA killed many civilians it believed to be aiding or giving information to the British (particularly in Munster

). Royal Irish Constabulary

(RIC) records later revealed the targeted Protestants unionists to have been non-collaborative and very tight-lipped. The IRA also burned historic stately homes in retaliation for the government policy of destroying the homes of republicans, suspected or actual. This clash came to be known as the War of Independence

or the Anglo-Irish War. It reinforced the fears of Ulster Unionists that they could never expect safeguards from an all-Ireland Sinn Féin government in Dublin.

In the background, Britain remained committed to implementing self-government for Ireland in accordance with the (temporarily suspended) Home Rule Act 1914

In the background, Britain remained committed to implementing self-government for Ireland in accordance with the (temporarily suspended) Home Rule Act 1914

. The British Cabinet drew up a committee to deal with this, the Long Committee

. This largely followed Unionist MP recommendations, since Dáil MPs boycotting Westminster had no say or input. These deliberations resulted in a new Fourth Home Rule Act (known as the Government of Ireland Act 1920

) being enacted primarily in the interest of Ulster Unionists. The Act granted (separate) Home Rule to two new institutions, the northeastern-most six counties of Ulster and the remaining twenty-six counties, both territories within the United Kingdom, which partitioned Ireland accordingly into two semi-autonomous regions: Northern Ireland

and Southern Ireland

, co-ordinated by a Council of Ireland

. Upon Royal Assent

, the Parliament of Northern Ireland

came into being in 1921. The institutions of Southern Ireland, however, were boycotted by nationalists and so never became functional.

In July 1921, a cease-fire was agreed and negotiations between delegations of the Irish and British sides produced the Anglo-Irish Treaty

. Under the treaty, southern and western Ireland was to be given a form of dominion status, modelled on the Dominion of Canada

. This was more than what was initially offered to Parnell, and somewhat more than had been achieved under the Irish Parliamentary Party's constitutional 'step by step' towards full freedom approach.

Northern Ireland

was given the right, immediately availed of, to opt out of the new Irish Free State

and an Irish Boundary Commission was to be established to work out the final details of the border. Initially, Northern Ireland comprised the north-east six counties of Ulster, while the remaining twenty-six formed the Free State: on receiving the report of the Boundary Commission, the Heads of Government declined to make any change to this arrangement.

narrowly passed the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921. Under the leadership of Michael Collins

and W. T. Cosgrave, it set about establishing the Irish Free State, with the pro-Treaty IRA becoming part of a fully re-organised new National Army and a new police force, the Civic Guard (quickly renamed as the Garda Síochána

), replacing one of Ireland's two police forces, the Royal Irish Constabulary

. The second, the Dublin Metropolitan Police

, merged some years later with the Gardaí.

However a minority led by Éamon de Valera opposed the treaty on the grounds that:

De Valera led his supporters out of the Dáil and, after a lapse of six months in which the IRA also split, a bloody civil war

between pro- and anti-treaty sides followed, only coming to an end in 1923 accompanied by multiple executions

. The civil war cost more lives than the Anglo-Irish War that preceded it and left divisions that are still felt strongly in Irish politics today.

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

from 1801 to 1922. For almost all of this period, Ireland was governed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

in London through its Dublin Castle administration in Ireland

Dublin Castle administration in Ireland

The Dublin Castle administration in Ireland was the government of Ireland under English and later British rule, from the twelfth century until 1922, based at Dublin Castle.-Head:...

. Ireland faced considerable economic difficulties in the 19th century, including the Great Famine of the 1840s. The late 19th century and early 20th century saw a vigorous campaign for Irish Home Rule. While legislation enabling Irish Home Rule was eventually passed, vigorous and armed opposition from Irish unionists, particularly in Ulster, opposed it. Proclamation was shelved for the duration following the outbreak of the Great War. By 1918, however, moderate nationalism

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

had been eclipsed by militant republican separatism. Ulster Unionism was adamantly opposed to its implementation.

Act of Union and Catholic Emancipation (1800–1830)

Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 , also known as the United Irishmen Rebellion , was an uprising in 1798, lasting several months, against British rule in Ireland...

. Prisoners were still being deported to Australia and sporadic violence continued in county Wicklow

County Wicklow

County Wicklow is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Mid-East Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Wicklow, which derives from the Old Norse name Víkingalág or Wykynlo. Wicklow County Council is the local authority for the county...

. There was another abortive rebellion led by Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet was an Irish nationalist and Republican, orator and rebel leader born in Dublin, Ireland...

in 1803. The Act of Union, which constitutionally made Ireland part of the British state can largely be seen as an attempt to redress the grievances of the 1798 rising and to prevent it from destabilising Britain or providing a base for foreign invasion.

In 1800 the Irish Parliament

Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland was a legislature that existed in Dublin from 1297 until 1800. In its early mediaeval period during the Lordship of Ireland it consisted of either two or three chambers: the House of Commons, elected by a very restricted suffrage, the House of Lords in which the lords...

and the Parliament of Great Britain

Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and Parliament of Scotland...

passed the Act of Union

Act of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 describe two complementary Acts, namely:* the Union with Ireland Act 1800 , an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, and...

which, from 1 January 1801, abolished the Irish legislature, and merged the Kingdom of Ireland

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland refers to the country of Ireland in the period between the proclamation of Henry VIII as King of Ireland by the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 and the Act of Union in 1800. It replaced the Lordship of Ireland, which had been created in 1171...

and the Kingdom of Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

. After one failed attempt, the passage of the act in the Irish parliament was finally achieved, albeit with the mass bribery of members of both houses, who were awarded British and United Kingdom peerage

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

s and other "encouragements".

In this period, Ireland was governed by authorities appointed in Great Britain. These were the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland was the British King's representative and head of the Irish executive during the Lordship of Ireland , the Kingdom of Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

, who was appointed by the King and the Chief Secretary for Ireland

Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, from the late 18th century until the end of British rule he was effectively the government minister with responsibility for governing Ireland; usually...

appointed by the British Prime Minister. As the century went on, the British Parliament took over from the monarch as the executive as well as legislative branch of government. For this reason, in Ireland, the Chief Secretary became more important than the Lord Lieutenant, who became of more symbolic than real importance. After the abolition of the Irish Parliament, Irish Members of Parliament were elected to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in Westminster. The British Administration in Ireland

Dublin Castle administration in Ireland

The Dublin Castle administration in Ireland was the government of Ireland under English and later British rule, from the twelfth century until 1922, based at Dublin Castle.-Head:...

– known by metonymy

Metonymy

Metonymy is a figure of speech used in rhetoric in which a thing or concept is not called by its own name, but by the name of something intimately associated with that thing or concept...

as "Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle off Dame Street, Dublin, Ireland, was until 1922 the fortified seat of British rule in Ireland, and is now a major Irish government complex. Most of it dates from the 18th century, though a castle has stood on the site since the days of King John, the first Lord of Ireland...

" – remained largely dominated by the Anglo-Irish establishment until the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922.

Part of the Union's attraction for many Irish Catholics was the promised abolition of the remaining Penal Laws then in force (which discriminated against Roman Catholics

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

), and the granting of Catholic Emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

. However King George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

blocked emancipation, believing that to grant it would break his coronation oath to defend the Anglican

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

church. A campaign under the Irish Catholic lawyer and politician Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell Daniel O'Connell Daniel O'Connell (6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847; often referred to as The Liberator, or The Emancipator, was an Irish political leader in the first half of the 19th century...

and the Catholic Association

Catholic Association

The Catholic Association was an Irish Roman Catholic political organisation set up by Daniel O'Connell in the early nineteenth century to campaign for Catholic emancipation within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was one of the first mass-membership political movements in...

led to renewed agitation for the abolition of the Test Act

Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and Nonconformists...

. Arthur Wellesley, the First Duke of Wellington, the Anglo Irish soldier and statesman, was at the peak of his enormous prestige as the victor of the Napoleonic Wars. As Prime Minister he used his considerable political power and influence to steer the enabling legislation through the U.K. Parliament. He then persuaded King George IV to sign the Act into in law under threat of resignation. The Catholic Relief Act 1829

Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom on 24 March 1829, and received Royal Assent on 13 April. It was the culmination of the process of Catholic Emancipation throughout the nation...

, allowed British and Irish Catholics to sit in the Parliament. Daniel O'Connell became the first Catholic M.P. to be seated since 1689. As head of the Repeal Association

Repeal Association

The Repeal Association was an Irish mass membership political movement set up by Daniel O'Connell to campaign for a repeal of the Act of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland....

, O'Connell mounted an unsuccessful campaign for the repeal of the Act of Union and the restoration of Irish self-government. O'Connell's tactics were largely peaceful, using mass rallies to show the popular support for his campaign. While O'Connell failed to gain repeal of the union, his efforts led to reforms in matters such as local government, and the Poor Laws.

Significant electoral reform acts s would enlarge the franchise throughout the U.K. in the ensuing century.

Despite O'Connell's peaceful methods, there was also a good deal of sporadic violence and rural unrest in the country in the first half of the 19th century. In Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

, there were repeated outbreaks of sectarian violence, such as the celebrated riot at Dolly's Brae, between Catholics and the nascent Orange Order

Orange Institution

The Orange Institution is a Protestant fraternal organisation based mainly in Northern Ireland and Scotland, though it has lodges throughout the Commonwealth and United States. The Institution was founded in 1796 near the village of Loughgall in County Armagh, Ireland...

. Elsewhere, tensions between the rapidly growing rural population on one side and their landlords and the state on the other, gave rise to much agrarian violence and social unrest. Secret peasant societies such as the "Whiteboys

Whiteboys

The Whiteboys were a secret Irish agrarian organization in 18th-century Ireland which used violent tactics to defend tenant farmer land rights for subsistence farming...

" and the "Ribbonmen" used sabotage and violence to intimidate landlords into better treatment of their tenants. The most sustained outbreak of violence was the "Tithe War

Tithe War

The Tithe War was a campaign of nonviolent civil disobedience, punctuated by sporadic violent episodes, in Ireland between 1830-36 in reaction to the enforcement of Tithes on subsistence farmers and others for the upkeep of the established state church - the Church of Ireland...

" of the 1830s, over the obligation of the mostly Catholic peasantry to pay tithes to the Protestant Church of Ireland

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland is an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. The church operates in all parts of Ireland and is the second largest religious body on the island after the Roman Catholic Church...

. The Royal Irish Constabulary

Royal Irish Constabulary

The armed Royal Irish Constabulary was Ireland's major police force for most of the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries. A separate civic police force, the unarmed Dublin Metropolitan Police controlled the capital, and the cities of Derry and Belfast, originally with their own police...

was set up in response to such violence to police rural areas.

The Great Famine (1845–1850)

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

and in the late 19th century (when it experienced a surge in economic growth unmatched until the 'Celtic Tiger

Celtic Tiger

Celtic Tiger is a term used to describe the economy of Ireland during a period of rapid economic growth between 1995 and 2007. The expansion underwent a dramatic reversal from 2008, with GDP contracting by 14% and unemployment levels rising to 14% by 2010...

' boom of the 1990s), to severe economic downturns and a series of famines, the last threatening in 1879. The worst of these was the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849), in which about one million people died and another million emigrated.

Ireland's economic problems were in part the result of the small size of Irish landholdings and a large increase in the population in the years before the famine. In particular, both the law and social tradition provided for subdivision of land, with all sons inheriting equal shares in a farm, meaning that farms became so small that only one crop, potatoes, could be grown in sufficient amounts to feed a family. Furthermore, many estates, from whom the small farmers rented, were poorly run by absentee landlords and in many cases heavily mortgaged. Enclosures of land since the turn of the 19th century had also exacerbated the problem, and the extensive grazing of cattle had contributed to the smaller plots of land available to tenants to raise their crops.

In the new Whig government in Britain (from 1846), Charles Trevelyan

Sir Charles Trevelyan, 1st Baronet

Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan, 1st Baronet, KCB was a British civil servant and colonial administrator. As a young man, he worked with the colonial government in Calcutta, India; in the late 1850s and 1860s he served there in senior-level appointments...

became assistant secretary to the Treasury, and largely responsible for the British government's response to the famine in Ireland.

When potato blight hit the island in 1845, much of the rural population was left without food. Unfortunately at this time, the then Prime Minister Lord John Russell adhered to a strict laissez-faire

Laissez-faire

In economics, laissez-faire describes an environment in which transactions between private parties are free from state intervention, including restrictive regulations, taxes, tariffs and enforced monopolies....

economic policy, which maintained that further state intervention would have the whole country dependent on hand-outs, and that what was needed was for economic viability to be encouraged. Despite a net surplus of food produced locally in Ireland, it was exported to England and elsewhere. Public works schemes were set up but proved inadequate, and the situation became catstrophic when epidemics of typhoid, cholera and dysentery took hold. Enormous sums were raised all over the world by charities (Native Americans

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

sent supplies, as did the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, while Queen Victoria

Victoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India....

personally gave the equivalent in modern money of €70,000). However the inadequate nature of the British government's initiatives led to a problem becoming a catastrophe; the class of cottiers or farm labourers was virtually wiped out.

Emigration was not uncommon in Ireland in the years preceding the famine. Between 1815–1845, Ireland had already established itself as the major supplier of overseas labour to Great Britain and America. However, emigration reached a peak during the famine, particularly in the years 1846–1855. The famine also saw increased emigration to Canada and assisted passages to Australia. Because of ongoing political tensions between the

US and the UK, the large and influential Irish American

Irish American

Irish Americans are citizens of the United States who can trace their ancestry to Ireland. A total of 36,278,332 Americans—estimated at 11.9% of the total population—reported Irish ancestry in the 2008 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau...

diaspora

Diaspora

A diaspora is "the movement, migration, or scattering of people away from an established or ancestral homeland" or "people dispersed by whatever cause to more than one location", or "people settled far from their ancestral homelands".The word has come to refer to historical mass-dispersions of...

created, financed and encouraged the Irish independence movement. In 1858, the Irish Republican Brotherhood

Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland during the second half of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century...

(IRB, also known as the Fenians) was founded as a secret society dedicated to armed rebellion against the British. A related organisation formed in New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

was known as Clan na Gael

Clan na Gael

The Clan na Gael was an Irish republican organization in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries, successor to the Fenian Brotherhood and a sister organization to the Irish Republican Brotherhood...

, which several times organised raids into the British Province of Canada

Province of Canada

The Province of Canada, United Province of Canada, or the United Canadas was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham in the Report on the Affairs of British North America following the Rebellions of...

. While the Fenians had a considerable presence in rural Ireland, the Fenian Rising

Fenian Rising

The Fenian Rising of 1867 was a rebellion against British rule in Ireland, organised by the Irish Republican Brotherhood .After the suppression of the Irish People newspaper, disaffection among Irish radical nationalists had continued to smoulder, and during the later part of 1866 IRB leader James...

launched in 1867 was a fiasco and was contained by police rather than the British military. Moreover, wider support for Irish republicanism

Irish Republicanism

Irish republicanism is an ideology based on the belief that all of Ireland should be an independent republic.In 1801, under the Act of Union, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland merged to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

, in the face of harsh laws against sedition

Sedition

In law, sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent to lawful authority. Sedition may include any...

, was minimal in Ireland in the period; as late as the 1860s, mass meetings of constitutional nationalists

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

ended with the singing of "God Save the Queen" while royal visits often drew cheering crowds.

Young Irelander Rebellion (1848)

Members of Repeal Association called the Young Irelanders, formed the Irish ConfederationIrish Confederation

The Irish Confederation was an Irish nationalist independence movement, established on 13 January 1847 by members of the Young Ireland movement who had seceded from Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association. Historian T. W...

tried to launch a rebellion

Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848

The Young Irelander Rebellion was a failed Irish nationalist uprising led by the Young Ireland movement. It took place on 29 July 1848 in the village of Ballingarry, County Tipperary. After being chased by a force of Young Irelanders and their supporters, an Irish Constabulary unit raided a house...

against British rule in 1848. This coincided with the worst years of the famine, however it was contained by Military action. William Smith O'Brien

William Smith O'Brien

William Smith O'Brien was an Irish Nationalist and Member of Parliament and leader of the Young Ireland movement. He was convicted of sedition for his part in the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848, but his sentence of death was commuted to deportation to Van Diemen's Land. In 1854, he was...

, leader of the Confederates, failure to capture a party of police barricaded in widow McCormack's house, who were holding her children as hostages, marked the effective end of the revolt.". Though intermittent resistance continued till late 1849, O'Brien and his colleagues were quickly arrested. Originally sentenced to death, this sentence was later commuted to transportation to Van Diemen's Land, where they joined John Mitchel

John Mitchel

John Mitchel was an Irish nationalist activist, solicitor and political journalist. Born in Camnish, near Dungiven, County Londonderry, Ireland he became a leading member of both Young Ireland and the Irish Confederation...

Land agitation and agrarian resurgence

Land War

The Land War in Irish history was a period of agrarian agitation in rural Ireland in the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s. The agitation was led by the Irish National Land League and was dedicated to bettering the position of tenant farmers and ultimately to a redistribution of land to tenants from...

" in Ireland, had a nationalist as well as a social element. The reason for this was that the land-owning class in Ireland, since the period of the 17th century Plantations of Ireland

Plantations of Ireland

Plantations in 16th and 17th century Ireland were the confiscation of land by the English crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from England and the Scottish Lowlands....

, had been composed of Protestant settlers, originally from England, who had a British identity. The Irish (Roman Catholic) population widely believed that the land had been unjustly taken from their ancestors and given to this Protestant Ascendancy

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy, usually known in Ireland simply as the Ascendancy, is a phrase used when referring to the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland by a minority of great landowners, Protestant clergy, and professionals, all members of the Established Church during the 17th...

during the English conquest of the country.

The Irish National Land League

Irish National Land League

The Irish Land League was an Irish political organization of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmers to own the land they worked on...

, was formed to defend the interests of tenant farmers, at first demanding the "Three Fs

Three Fs

The Three Fs were a series of demands first issued by the Tenant Right League in their campaign for land reform in Ireland from the 1850s. They were,...

" – Fair rent, Free sale and Fixity of tenure. Members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland during the second half of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century...

, such as Michael Davitt

Michael Davitt

Michael Davitt was an Irish republican and nationalist agrarian agitator, a social campaigner, labour leader, journalist, Home Rule constitutional politician and Member of Parliament , who founded the Irish National Land League.- Early years :Michael Davitt was born in Straide, County Mayo,...

, were prominent among the leadership of this movement. When they saw its potential for popular mobilisation, nationalist leaders such as Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell was an Irish landowner, nationalist political leader, land reform agitator, and the founder and leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party...

also became involved.

The most effective tactic of the Land League was the boycott

Boycott

A boycott is an act of voluntarily abstaining from using, buying, or dealing with a person, organization, or country as an expression of protest, usually for political reasons...

(the word originates in Ireland in this period), where unpopular landlords were ostracised by the local community. Grassroots Land League members used violence against landlords and their property; attempted evictions of tenant farmers regularly turned into armed confrontations. Under the British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, an Irish Coercion Act

Irish Coercion Act

The Protection of Person and Property Act 1881 was one of more than 100 Coercion Acts passed by the Parliament of United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland between 1801 and 1922, in an attempt to establish law and order in Ireland. The 1881 Act was passed by parliament and introduced by...

was first introduced – a form of martial law – to contain the violence. Parnell, Davitt, William O'Brien

William O'Brien

William O'Brien was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

and the other leaders of the Land League were temporarily imprisoned – being held responsible for the violence.

Ultimately, the land question was settled through successive Irish Land Acts by United Kingdom governments – beginning with the 1881 Act of William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

, which first gave extensive rights to tenant farmers, then the Wyndham

George Wyndham

George Wyndham PC was a British Conservative politician, man of letters, noted for his elegance, and one of The Souls.-Background and education:...

Land Purchase Act (1903) won by William O'Brien after the 1902 Land Conference

Land Conference

The Land Conference was a successful conciliatory negotiation held in the Mansion House in Dublin, Ireland between 20 December 1902 and 4 January 1903. In a short period it produced a unanimously agreed report recommending an amiable solution to the long waged land war between tenant farmers and...

, enabling tenant farmers purchase their plots of land from their landlords, the problems of non-existent rural housing resolved by D.D. Sheehan under the Bryce

James Bryce, 1st Viscount Bryce

James Bryce, 1st Viscount Bryce OM, GCVO, PC, FRS, FBA was a British academic, jurist, historian and Liberal politician.-Background and education:...

Labourers (Ireland) Act (1906). These acts created a very large class of small property owners in the Irish countryside, and dissipated the power of the old Anglo-Irish landed class.

Unrest and agitation also resulted in the successful introduction of agricultural co-operatives through the initiative of Horace Plunkett, but the most positive changes came after the introduction of the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898

Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898

The Local Government Act 1898 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that established a system of local government in Ireland similar to that already created for England, Wales and Scotland by legislation in 1888 and 1889...

which put the control and running of rural affairs into local hands. However it did not end support for independent Irish nationalism, as British governments had hoped. See also Irish Land Commission

Irish Land Commission

The Irish Land Commission was created in 1881 as a rent fixing commission by the Land Law Act 1881, also known as the second Irish Land Act...

.

Culture and the Gaelic revival

The Culture of IrelandCulture of Ireland

This article is about the modern culture of Ireland and the Irish people. It includes customs and traditions, language, music, art, literature, folklore, cuisine and sport associated with Ireland and Irish people today. However, the culture of the people living in Ireland is not homogeneous...

underwent a massive change in the course of the 19th century. After the Famine, the Irish language

Irish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

went into steep decline. This process was started in the 1820s, when the first National Schools were set up in the country. These had the advantage of encouraging literacy, but classes were provided only in English and the speaking of Irish was prohibited. However, before the 1840s, Irish was still the majority language in the country and numerically (given the rise in population) may have had more speakers than ever before. The Famine devastated the Irish speaking areas of the country, which tended also to be rural and poor. As well as causing the deaths of thousands of Irish speakers, the famine also led to sustained and widespread emigration from the Irish-speaking south and west of the country. By 1900, for the first time in perhaps two millennia, Irish was no longer the majority language in Ireland, and continued to decline in importance. By the time of Irish independence, the Gaeltacht

Gaeltacht

is the Irish language word meaning an Irish-speaking region. In Ireland, the Gaeltacht, or an Ghaeltacht, refers individually to any, or collectively to all, of the districts where the government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant language, that is, the vernacular spoken at home...

s had shrunk to small areas along the western seaboard.

In reaction, to this, Irish nationalists began a "Gaelic revival" in the late 19th century, hoping to revive the Irish language and Irish literature and sports. While social organisations such as the Gaelic League and the Gaelic Athletic Association

Gaelic Athletic Association

The Gaelic Athletic Association is an amateur Irish and international cultural and sporting organisation focused primarily on promoting Gaelic games, which include the traditional Irish sports of hurling, camogie, Gaelic football, handball and rounders...

were very successful in attracting members, most of their activists were English speakers and the movement did not halt the decline of the Irish language.

The form of English established in Ireland differed somewhat from British English

British English

British English, or English , is the broad term used to distinguish the forms of the English language used in the United Kingdom from forms used elsewhere...

and its variants. Blurring linguistic structures from older forms of English (notably Elizabethan English) and the Irish language, it is known as Hiberno-English

Hiberno-English

Hiberno-English is the dialect of English written and spoken in Ireland .English was first brought to Ireland during the Norman invasion of the late 12th century. Initially it was mainly spoken in an area known as the Pale around Dublin, with Irish spoken throughout the rest of the country...

and was strongly associated with turn of the 20th century Celtic Revival

Celtic Revival

Celtic Revival covers a variety of movements and trends, mostly in the 19th and 20th centuries, which drew on the traditions of Celtic literature and Celtic art, or in fact more often what art historians call Insular art...

and Irish writers like J.M. Synge, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60...

, Sean O'Casey

Seán O'Casey

Seán O'Casey was an Irish dramatist and memoirist. A committed socialist, he was the first Irish playwright of note to write about the Dublin working classes.- Early life:...

, and had resonances in the English of Dublin-born Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s...

. Some nationalists saw the celebration of Hiberno-Irish by predominantly Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish was a term used primarily in the 19th and early 20th centuries to identify a privileged social class in Ireland, whose members were the descendants and successors of the Protestant Ascendancy, mostly belonging to the Church of Ireland, which was the established church of Ireland until...

writers as offensive "stage Irish

Stage Irish

Stage Irish is a stereotyped portrayal of Irish people once common in plays. The term refers to an exaggerated or caricatured portrayal of supposed Irish characteristics in speech and behaviour...

" caricature. Synge's play The Playboy of the Western World

The Playboy of the Western World

The Playboy of the Western World is a three-act play written by Irish playwright John Millington Synge and first performed at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, on January 26, 1907. It is set in Michael James Flaherty's public house in County Mayo during the early 1900s...

was marked by rioting at performances.

Home Rule movement (1870–1914)

Until the 1870s, most Irish people elected as their Members of Parliament (MPs) LiberalsLiberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

and Conservatives

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

who belonged to the main British political parties. The Conservatives, for example, won a majority in the 1859 general election in Ireland. A significant minority also voted for Unionists, who resisted fiercely any dilution of the Act of Union. In the 1870s a former Conservative barrister turned nationalist

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

campaigner, Isaac Butt

Isaac Butt

Isaac Butt Q.C. M.P. was an Irish barrister, politician, Member of Parliament , and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist parties and organisations, including the Irish Metropolitan Conservative Society in 1836, the Home Government Association in 1870 and in 1873 the Home...

, established a new moderate nationalist movement, the Home Rule League

Home Rule League

The Home Rule League, sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was a political party which campaigned for home rule for the country of Ireland from 1873 to 1882, when it was replaced by the Irish Parliamentary Party.-Origins:...

. After his death, William Shaw

William Shaw (Irish politician)

William Shaw was an Irish Protestant nationalist politician. He was a Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and one of the founders of the Irish home rule movement....

and in particular a radical young Protestant landowner, Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell was an Irish landowner, nationalist political leader, land reform agitator, and the founder and leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party...

, turned the home rule movement, or the Irish Parliamentary Party

Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party was formed in 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nationalist Members of Parliament elected to the House of Commons at...

(IPP) as it became known, into a major political force. It came to dominate Irish politics, to the exclusion of the previous Liberal, Conservative and Unionist parties that had existed there. The party's growing electoral strength was first shown in the 1880 general election in Ireland, when it won 63 seats (two MPs later defected to the Liberals). By the 1885 general election in Ireland

United Kingdom general election, 1885

-Seats summary:-See also:*List of MPs elected in the United Kingdom general election, 1885*Parliamentary Franchise in the United Kingdom 1885–1918*Representation of the People Act 1884*Redistribution of Seats Act 1885-References:...

it had won 86 seats (including one in the heavily Irish-populated English city of Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

). Parnell's movement proved to be a broad one, from conservative landowners to the Land League

Irish National Land League

The Irish Land League was an Irish political organization of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmers to own the land they worked on...

.

Parnell's movement also campaigned for the right of Ireland to govern herself as a region within the United Kingdom, in contrast to O'Connell who had wanted a complete repeal of the Act of Union. Two home rule bills (in 1886 and 1893) were introduced by Liberal Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

, but neither became law. The issue divided Ireland: a significant minority of Unionists (largely though by no means exclusively based in Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

), but principally the revived radical Orange Order

Orange Institution

The Orange Institution is a Protestant fraternal organisation based mainly in Northern Ireland and Scotland, though it has lodges throughout the Commonwealth and United States. The Institution was founded in 1796 near the village of Loughgall in County Armagh, Ireland...

opposed home rule, fearing that a Dublin parliament dominated by Catholics

Rome Rule

"Rome Rule" was a term used by Irish unionists and socialists to describe the belief that the Roman Catholic Church would gain political control over their interests with the passage of a Home Rule Bill...

and nationalists would discriminate against them and would impose tariffs on trade with Great Britain. (Whilst most of Ireland was primarily agricultural, north-east Ulster was the location of almost all the island's heavy industry and would have been affected by any tariff barriers imposed.)

In 1889, the scandal surrounding Parnell's divorce proceedings split the Irish party, when it became public that Parnell, popularly acclaimed as the 'Uncrowned King of Ireland', had for many years been living in a family relationship with Mrs. Katharine O'Shea, the long separated wife of a fellow MP. When the scandal broke, religious non-conformists in Great Britain, who were the backbone of the pro-Home Rule Liberal Party, forced its leader W. E. Gladstone to abandon support for the Irish cause as long as Parnell remained leader of the IPP. Parnell was subsequently deposed and died in 1891. But the Party and the country remained split between pro-Parnellites and anti-Parnellites

Irish National Federation

The Irish National Federation was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded in March 1891 by former members of the Irish National League who had left the Irish Parliamentary Party in protest when Charles Stewart Parnell refused to resign the party leadership as a result of his...

, who fought each other in elections.

The United Irish League

United Irish League

The United Irish League was a nationalist political party in Ireland, launched 23 January 1898 with the motto "The Land for the People" . Its objective to be achieved through agrarian agitation and land reform, compelling larger grazier farmers to surrender their lands for redistribution amongst...

founded in 1898 forced the reunification of the party to stand under John Redmond

John Redmond

John Edward Redmond was an Irish nationalist politician, barrister, MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party from 1900 to 1918...

in the 1901 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1900

-Seats summary:-See also:*MPs elected in the United Kingdom general election, 1900*The Parliamentary Franchise in the United Kingdom 1885-1918-External links:***-References:*F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987**...