HM Bark Endeavour

Encyclopedia

HMS Endeavour, also known as HM Bark Endeavour, was a British Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

research vessel

Research vessel

A research vessel is a ship designed and equipped to carry out research at sea. Research vessels carry out a number of roles. Some of these roles can be combined into a single vessel, others require a dedicated vessel...

commanded by Lieutenant James Cook

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

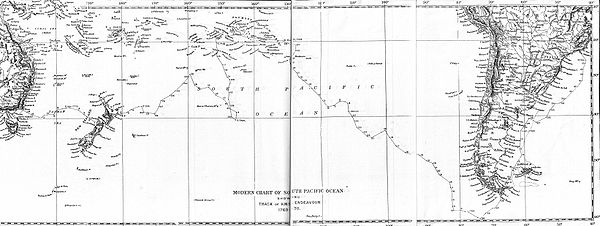

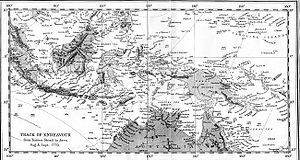

on his first voyage of discovery

First voyage of James Cook

The first voyage of James Cook was a combined Royal Navy and Royal Society expedition to the south Pacific ocean aboard HMS Endeavour, from 1768 to 1771...

, to Australia and New Zealand from 1769 to 1771.

Launched in 1764 as the collier

Collier (ship type)

Collier is a historical term used to describe a bulk cargo ship designed to carry coal, especially for naval use by coal-fired warships. In the late 18th century a number of wooden-hulled sailing colliers gained fame after being adapted for use in voyages of exploration in the South Pacific, for...

Earl of Pembroke, she was purchased by the Navy in 1768 for a scientific mission to the Pacific Ocean

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

, and to explore the seas for the surmised Terra Australis Incognita or "unknown southern land". Renamed and commissioned as His Majesty's Bark the Endeavour, she departed Plymouth

Plymouth

Plymouth is a city and unitary authority area on the coast of Devon, England, about south-west of London. It is built between the mouths of the rivers Plym to the east and Tamar to the west, where they join Plymouth Sound...

in August 1768, rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn

Cape Horn is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island...

, and reached Tahiti

Tahiti

Tahiti is the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia, located in the archipelago of the Society Islands in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is the economic, cultural and political centre of French Polynesia. The island was formed from volcanic activity and is high and mountainous...

in time to observe the 1769 transit of Venus

Transit of Venus

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and Earth, becoming visible against the solar disk. During a transit, Venus can be seen from Earth as a small black disk moving across the face of the Sun...

across the Sun. She then set sail into the largely uncharted ocean to the south, stopping at the Pacific islands of Huahine

Huahine

Huahine is an island located among the Society Islands, in French Polynesia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. It is part of the Leeward Islands group . The island has a population of about 6,000.-Geography:...

, Borabora, and Raiatea

Raiatea

Raiatea , is the second largest of the Society Islands, after Tahiti, in French Polynesia. The island is widely regarded as the 'center' of the eastern islands in ancient Polynesia and it is likely that the organised migrations to Hawaii, Aotearoa and other parts of East Polynesia started at...

to allow Cook to claim them for Great Britain. In September 1769, she anchored off New Zealand, the first European vessel to reach the islands since Abel Tasman

Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the VOC . His was the first known European expedition to reach the islands of Van Diemen's Land and New Zealand and to sight the Fiji islands...

's Heemskerck 127 years earlier. In April 1770, Endeavour became the first seagoing vessel to reach the east coast of Australia, when Cook went ashore at what is now known as Botany Bay

Botany Bay

Botany Bay is a bay in Sydney, New South Wales, a few kilometres south of the Sydney central business district. The Cooks River and the Georges River are the two major tributaries that flow into the bay...

.

Endeavour then sailed north along the Australian coast. She narrowly avoided disaster after running aground on the Great Barrier Reef

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world'slargest reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over 2,600 kilometres over an area of approximately...

, and was beached on the mainland for seven weeks to permit rudimentary repairs to her hull. On 10 October 1770, she limped into port in Batavia (now named Jakarta

Jakarta

Jakarta is the capital and largest city of Indonesia. Officially known as the Special Capital Territory of Jakarta, it is located on the northwest coast of Java, has an area of , and a population of 9,580,000. Jakarta is the country's economic, cultural and political centre...

) in the Dutch East Indies

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies was a Dutch colony that became modern Indonesia following World War II. It was formed from the nationalised colonies of the Dutch East India Company, which came under the administration of the Netherlands government in 1800....

for more substantial repairs, her crew sworn to secrecy about the lands they had discovered. She resumed her westward journey on 26 December, rounded the Cape of Good Hope

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa.There is a misconception that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Africa, because it was once believed to be the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In fact, the...

on 13 March 1771, and reached the English port of Dover

Dover

Dover is a town and major ferry port in the home county of Kent, in South East England. It faces France across the narrowest part of the English Channel, and lies south-east of Canterbury; east of Kent's administrative capital Maidstone; and north-east along the coastline from Dungeness and Hastings...

on 12 July, having been at sea for nearly three years.

Largely forgotten after her epic voyage, Endeavour spent the next three years shipping Navy stores to the Falkland Islands

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands are an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean, located about from the coast of mainland South America. The archipelago consists of East Falkland, West Falkland and 776 lesser islands. The capital, Stanley, is on East Falkland...

. Renamed and sold into private hands in 1775, she briefly returned to naval service as a troop transport during the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

and was scuttled

Scuttling

Scuttling is the act of deliberately sinking a ship by allowing water to flow into the hull.This can be achieved in several ways—valves or hatches can be opened to the sea, or holes may be ripped into the hull with brute force or with explosives...

in a blockade of Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island in 1778. Her wreck has not been precisely located, but relics, including six of her cannons and an anchor, are displayed at maritime museum

Maritime museum

A maritime museum is a museum specializing in the display of objects relating to ships and travel on large bodies of water...

s worldwide. A replica

Ship replica

A ship replica is a reconstruction of a no longer existing ship. Replicas can range from authentically reconstructed, fully seaworthy ships, to ships of modern construction that give an impression of an historic vessel...

of Endeavour was launched in 1994 and is berthed alongside the Australian National Maritime Museum

Australian National Maritime Museum

The Australian National Maritime Museum is a federally-operated maritime museum located in Darling Harbour, Sydney. After consideration of the idea to establish a maritime museum, the Federal government announced that a national maritime museum would be constructed at Darling Harbour, tied into...

in Sydney Harbour

Port Jackson

Port Jackson, containing Sydney Harbour, is the natural harbour of Sydney, Australia. It is known for its beauty, and in particular, as the location of the Sydney Opera House and Sydney Harbour Bridge...

. The space shuttle Endeavour

Space Shuttle Endeavour

Space Shuttle Endeavour is one of the retired orbiters of the Space Shuttle program of NASA, the space agency of the United States. Endeavour was the fifth and final spaceworthy NASA space shuttle to be built, constructed as a replacement for Challenger...

is named for the original ship.

HMS Endeavour features on the New Zealand fifty cent piece in recognition of its significant place in the nation's history.

Construction

Endeavour was originally a merchant collier named Earl of Pembroke, launched in June 1764 from the coal and whaling port of WhitbyWhitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in the Scarborough borough of North Yorkshire, England. Situated on the east coast of Yorkshire at the mouth of the River Esk, Whitby has a combined maritime, mineral and tourist heritage, and is home to the ruins of Whitby Abbey where Caedmon, the...

in North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire is a non-metropolitan or shire county located in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England, and a ceremonial county primarily in that region but partly in North East England. Created in 1974 by the Local Government Act 1972 it covers an area of , making it the largest...

, and as such is known locally as the Whitby Cat. She was ship-rigged

Full rigged ship

A full rigged ship or fully rigged ship is a sailing vessel with three or more masts, all of them square rigged. A full rigged ship is said to have a ship rig....

and sturdily built with a broad, flat bow, a square stern and a long box-like body with a deep hold. Her length was 106 feet (32.3 m), and 97 in 7 in (29.74 m) on her lower deck, with a beam

Beam (nautical)

The beam of a ship is its width at the widest point. Generally speaking, the wider the beam of a ship , the more initial stability it has, at expense of reserve stability in the event of a capsize, where more energy is required to right the vessel from its inverted position...

of 29 in 3 in (8.92 m). Her burthen was 368 71/94 tons.

A flat-bottomed design made her well-suited to sailing in shallow waters and allowed her to be beached

Beach (nautical)

Beaching is when a vessel is laid ashore, or grounded deliberately in shallow water. This is more usual with small flat-bottomed boats. Larger ships may be beached deliberately, for instance in an emergency a damaged ship might be beached to prevent it from sinking in deep water...

for loading and unloading of cargo and for basic repairs without requiring a dry dock

Dry dock

A drydock is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform...

. Her hull

Hull (watercraft)

A hull is the watertight body of a ship or boat. Above the hull is the superstructure and/or deckhouse, where present. The line where the hull meets the water surface is called the waterline.The structure of the hull varies depending on the vessel type...

, internal floors and futtocks were built from traditional white oak

White oak

Quercus alba, the white oak, is one of the pre-eminent hardwoods of eastern North America. It is a long-lived oak of the Fagaceae family, native to eastern North America and found from southern Quebec west to eastern Minnesota and south to northern Florida and eastern Texas. Specimens have been...

, her keel

Keel

In boats and ships, keel can refer to either of two parts: a structural element, or a hydrodynamic element. These parts overlap. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in construction of a ship, in British and American shipbuilding traditions the construction is dated from this event...

and stern post from elm

Elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus Ulmus in the plant family Ulmaceae. The dozens of species are found in temperate and tropical-montane regions of North America and Eurasia, ranging southward into Indonesia. Elms are components of many kinds of natural forests...

and her masts from pine

Pine

Pines are trees in the genus Pinus ,in the family Pinaceae. They make up the monotypic subfamily Pinoideae. There are about 115 species of pine, although different authorities accept between 105 and 125 species.-Etymology:...

and fir

Fir

Firs are a genus of 48–55 species of evergreen conifers in the family Pinaceae. They are found through much of North and Central America, Europe, Asia, and North Africa, occurring in mountains over most of the range...

. Plans of the ship also show a double keelson to lock the keel, floors and frames in place.

Some doubt exists about the height of her masts, as surviving diagrams of Endeavour depict the body of the vessel only, and not the mast plan. While her main and foremasts are accepted to be a standard 129 and 110 ft (39.3 and 33.5 ) respectively, an annotation on one surviving ship plan records the mizzen as "16 yards 29 inches" ( m). If correct, this would produce an oddly truncated mast a full 9 feet (2.7 m) shorter than the standards of the day. Modern research suggests the annotation may be a transcription error and should read "19 yards 29 inches" ( m), which would more closely conform with both the naval standards and the lengths of the other masts. The replica is built to this shorter measurement, as are all current commercial models, and the model in the National Maritime Museum built by the NMM Greenwich. Note, for example, the differences between the height of the mizzen for-and-aft spar in the contemporary painting by Luny (below) and its position on the replica in the photographs, compared to the height of the lowest spars on the fore and mainmasts.

Purchase and refit by Admiralty

On 16 February 1768, the Royal SocietyRoyal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

petitioned King George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

to finance a scientific expedition to the Pacific to study and observe the 1769 transit of Venus across the sun. Royal approval was granted for the expedition, and the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

elected to combine the scientific voyage with a confidential mission to search the south Pacific for signs of the postulated continent Terra Australis Incognita (or "unknown southern land").

The Royal Society suggested command be given to Scottish geographer Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple was a Scottish geographer and the first Hydrographer of the British Admiralty. He was the main proponent of the theory that there existed a vast undiscovered continent in the South Pacific, Terra Australis Incognita...

, whose acceptance was conditional on a brevet

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

commission as a captain in the Royal Navy. However, First Lord of the Admiralty Edward Hawke refused, going so far as to say he would rather cut off his right hand than give command of a Navy vessel to someone not educated as a seaman. In refusing Dalrymple's command, Hawke was influenced by previous insubordination aboard the sloop in 1698, when naval officers had refused to take orders from civilian commander Dr. Edmond Halley

Edmond Halley

Edmond Halley FRS was an English astronomer, geophysicist, mathematician, meteorologist, and physicist who is best known for computing the orbit of the eponymous Halley's Comet. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, following in the footsteps of John Flamsteed.-Biography and career:Halley...

. The impasse was broken when the Admiralty proposed James Cook, a naval officer with a background in mathematics and cartography

Cartography

Cartography is the study and practice of making maps. Combining science, aesthetics, and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality can be modeled in ways that communicate spatial information effectively.The fundamental problems of traditional cartography are to:*Set the map's...

. Acceptable to both parties, Cook was promoted to Lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

and named as commander of the expedition.

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

, the hull sheathed and caulked

Caulking

Caulking is one of several different processes to seal joints or seams in various structures and certain types of piping. The oldest form of caulking is used to make the seams in wooden boats or ships watertight, by driving fibrous materials into the wedge-shaped seams between planks...

to protect against shipworm

Shipworm

Shipworms are not worms at all, but rather a group of unusual saltwater clams with very small shells, notorious for boring into wooden structures that are immersed in sea water, such as piers, docks and wooden ships...

, and a third internal deck installed to provide cabins, a powder magazine and storerooms. The new cabins provided around 2 square metres (21.5 sq ft) of floorspace apiece and were allocated to Cook and the Royal Society representatives: naturalist

Natural history

Natural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, GCB, PRS was an English naturalist, botanist and patron of the natural sciences. He took part in Captain James Cook's first great voyage . Banks is credited with the introduction to the Western world of eucalyptus, acacia, mimosa and the genus named after him,...

, Banks' assistants Daniel Solander

Daniel Solander

Daniel Carlsson Solander or Daniel Charles Solander was a Swedish naturalist and an apostle of Carl Linnaeus. Solander was the first university educated scientist to set foot on Australian soil.-Biography:...

and Herman Spöring

Herman Spöring Jr.

Herman Diedrich Spöring Jr. was a Finnish explorer, draughtsman, botanist and a naturalist.- Early life :He was born in 1733 in the Finnish town of Turku, at that time the major Finnish city and administrative center under the Kingdom of Sweden. He was the son of an amateur naturalist and...

, astronomer Charles Green

Charles Green (astronomer)

Charles Green was a British astronomer, noted for his assignment by the Royal Society in 1768 to the expedition sent to the Pacific Ocean in order to observe the transit of Venus and the transit of Mercury, aboard James Cook's Endeavour.A farmer's son, he became assistant to the Astronomer Royal...

, and artists Sydney Parkinson

Sydney Parkinson

Sydney Parkinson was a Scottish Quaker, botanical illustrator and natural history artist.Parkinson was employed by Joseph Banks to travel with him on James Cook's first voyage to the Pacific in 1768. Parkinson made nearly a thousand drawings of plants and animals collected by Banks and Daniel...

and Alexander Buchan. These cabins encircled the officer′s mess. The Great Cabin at the rear of the deck was designed as a workroom for Cook and the Royal Society. On the rear lower deck, cabins facing on to the mate's mess were assigned to Lieutenants Zachary Hicks and John Gore

John Gore (seaman)

Captain John Gore was a British American sailor who circumnavigated the globe four times with the Royal Navy in the 18th century and accompanied Captain James Cook in his discoveries in the Pacific Ocean.-History:...

, ship's surgeon William Monkhouse, the gunner Stephen Forwood, ship's master Robert Molyneux, and the captain's clerk

Captain's clerk

A captain's clerk was a rating, now obsolete, in the Royal Navy for a person employed by the captain to keep his records, correspondence, and accounts. The regulations of the Royal Navy demanded that a purser serve at least one year as a captain's clerk, so the latter was often a young man working...

Richard Orton. The adjoining open mess deck provided sleeping and living quarters for the marines and crew, and additional storage space.

A longboat

Longboat

In the days of sailing ships, a vessel would carry several ship's boats for various uses. One would be a longboat, an open boat to be rowed by eight or ten oarsmen, two per thwart...

, pinnace

Pinnace (ship's boat)

As a ship's boat the pinnace is a light boat, propelled by sails or oars, formerly used as a "tender" for guiding merchant and war vessels. In modern parlance, pinnace has come to mean a boat associated with some kind of larger vessel, that doesn't fit under the launch or lifeboat definitions...

and yawl

Yawl

A yawl is a two-masted sailing craft similar to a sloop or cutter but with an additional mast located well aft of the main mast, often right on the transom, specifically aft of the rudder post. A yawl (from Dutch Jol) is a two-masted sailing craft similar to a sloop or cutter but with an...

were provided as ship's boats, though the longboat was rotten and had to be rebuilt and painted with white lead

White lead

White lead is the chemical compound 2·Pb2. It was formerly used as an ingredient for lead paint and a cosmetic called Venetian Ceruse, because its opaque quality made it a good pigment. However, it tended to cause lead poisoning, and its use has been banned in most countries.White lead has been...

before it could be brought aboard. These were accompanied by two privately owned skiffs, one belonging to the boatswain

Boatswain

A boatswain , bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun is an unlicensed member of the deck department of a merchant ship. The boatswain supervises the other unlicensed members of the ship's deck department, and typically is not a watchstander, except on vessels with small crews...

John Gathrey, and the other to Banks. The ship was also equipped with a set of 28 ft (8.5 m) sweeps to allow her to be rowed forward if becalmed or demasted. The refitted vessel was commissioned as His Majesty's Bark

Barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing vessel with three or more masts.- History of the term :The word barque appears to have come from the Greek word baris, a term for an Egyptian boat. This entered Latin as barca, which gave rise to the Italian barca, Spanish barco, and the French barge and...

the Endeavour, to distinguish her from another already commissioned in the Royal Navy, a 14-gun sloop.

On 21 July 1768, Endeavour sailed to Galleon's Reach to take on armaments to protect her against potentially hostile Pacific island natives. Ten 4-pounder cannons were brought aboard, six of which were mounted on the upper deck and the remainder stowed in the hold. Twelve swivel guns were also supplied, and fixed to posts along the quarterdeck, sides and bow. The ship departed for Plymouth

Plymouth

Plymouth is a city and unitary authority area on the coast of Devon, England, about south-west of London. It is built between the mouths of the rivers Plym to the east and Tamar to the west, where they join Plymouth Sound...

on 30 July, for provisioning and to board her crew of 85, including 12 Royal Marines

Royal Marines

The Corps of Her Majesty's Royal Marines, commonly just referred to as the Royal Marines , are the marine corps and amphibious infantry of the United Kingdom and, along with the Royal Navy and Royal Fleet Auxiliary, form the Naval Service...

. Cook also ordered that twelve tons of pig iron

Pig iron

Pig iron is the intermediate product of smelting iron ore with a high-carbon fuel such as coke, usually with limestone as a flux. Charcoal and anthracite have also been used as fuel...

be brought on board as sailing ballast

Sailing ballast

Ballast is used in sailboats to provide moment to resist the lateral forces on the sail. Insufficiently ballasted boats will tend to tip, or heel, excessively in high winds. Too much heel may result in the boat capsizing. If a sailing vessel should need to voyage without cargo then ballast of...

.

Outward voyage

Endeavour departed Plymouth on 26 August 1768, carrying 94 people and 18 months of provisions. Livestock on board included pigs, poultry, two greyhounds and a milking goat.The first port of call was Funchal

Funchal

Funchal is the largest city, the municipal seat and the capital of Portugal's Autonomous Region of Madeira. The city has a population of 112,015 and has been the capital of Madeira for more than five centuries.-Etymology:...

in the Madeira Islands, which Endeavour reached on 12 September. The ship was recaulked and painted, and fresh vegetables, beef and water brought aboard for the next leg of the voyage. While in port, an accident cost the life of the master's mate Robert Weir, who became entangled in the anchor cable and was dragged overboard when the anchor was released. To replace him, Cook shanghaiied

Shanghaiing

Shanghaiing refers to the practice of conscripting men as sailors by coercive techniques such as trickery, intimidation, or violence. Those engaged in this form of kidnapping were known as crimps. Until 1915, unfree labor was widely used aboard American merchant ships...

a sailor from an American sloop anchored nearby.

Endeavour then continued south along the coast of Africa and across the Atlantic

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

to South America, arriving in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro , commonly referred to simply as Rio, is the capital city of the State of Rio de Janeiro, the second largest city of Brazil, and the third largest metropolitan area and agglomeration in South America, boasting approximately 6.3 million people within the city proper, making it the 6th...

on 13 November 1768. Fresh food and water were brought aboard and the ship departed for Cape Horn

Cape Horn

Cape Horn is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island...

, which she reached during stormy weather on 13 January 1769. However, attempts to round the Cape over the next two days were unsuccessful, with Endeavour repeatedly driven back by wind, rain and contrary tides. Cook noted that the seas off the Cape were large enough to regularly submerge the bow of the ship as she rode down the crests of waves. At last, on 16 January the wind eased and the ship was able to pass the Cape and anchor in the Bay of Good Success on the Pacific coast. The crew were sent to collect wood and water, while Banks and his team gathered hundreds of plant specimens from along the icy shore. On 17 January two of Banks' servants died from cold while attempting to return to the ship during a heavy snowstorm.

Endeavour resumed her voyage on 21 January 1769, heading west-northwest into warmer weather. She reached Tahiti

Tahiti

Tahiti is the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia, located in the archipelago of the Society Islands in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is the economic, cultural and political centre of French Polynesia. The island was formed from volcanic activity and is high and mountainous...

on 10 April, where she remained for the next two months. The transit of Venus across the Sun occurred on 3 June, and was observed and recorded by astronomer Charles Green from Endeavour’s deck.

Pacific exploration

The transit observed, Endeavour departed Tahiti on 13 July and headed northwest to allow Cook to survey and name the Society IslandsSociety Islands

The Society Islands are a group of islands in the South Pacific Ocean. They are politically part of French Polynesia. The archipelago is generally believed to have been named by Captain James Cook in honor of the Royal Society, the sponsor of the first British scientific survey of the islands;...

. Landfall was made at Huahine, Raiatea and Borabora, providing opportunities for Cook to claim each of them as British territories. However, an attempt to land the pinnace on the Austral Island

Austral Islands

The Austral Islands are the southernmost group of islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in the South Pacific. Geographically, they consist of two separate archipelagos, namely in the northwest the Tubuai Islands consisting of the Îles Maria, Rimatara, Rurutu, Tubuai...

of Rurutu

Rurutu (Austral Islands)

Rurutu is the northernmost island in the Austral archipelago of French Polynesia, and the name of a commune consisting solely of that island. It is situated south of Tahiti....

was thwarted by rough surf and the rocky shoreline. On 15 August, Endeavour finally turned south to explore the open ocean for Terra Australis Incognita.

In October 1769, Endeavour reached the coastline of New Zealand, becoming the first European vessel to do so since Abel Tasman

Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the VOC . His was the first known European expedition to reach the islands of Van Diemen's Land and New Zealand and to sight the Fiji islands...

's Heemskerck in 1642. Unfamiliar with such ships, the Māori people at Cook's first landing point in Poverty Bay

Poverty Bay

Poverty Bay is the largest of several small bays on the east coast of New Zealand's North Island to the north of Hawkes Bay. It stretches for 10 kilometres from Young Nick's Head in the southwest to Tuaheni Point in the northeast. The city of Gisborne is located on the northern shore of the bay...

thought the ship was a floating island, or a gigantic bird from their mythical homeland of Hawaiki

Hawaiki

In Māori mythology, Hawaiki is the homeland of the Māori, the original home of the Māori, before they travelled across the sea to New Zealand...

. Endeavour spent the next six months sailing close to shore, while Cook mapped the coastline and reached the conclusion that New Zealand comprised two large islands and was not the hoped-for Terra Australis. In March 1770, the longboat from Endeavour carried Cook ashore to allow him to formally proclaim British sovereignty over New Zealand. On his return, Endeavour resumed her voyage westward, her crew sighting the east coast of Australia on 19 April. On 29 April, she became the first European vessel to make landfall on the east coast of Australia, when Cook landed one of the ship's boats on the southern shore of what is now known as Botany Bay

Botany Bay

Botany Bay is a bay in Sydney, New South Wales, a few kilometres south of the Sydney central business district. The Cooks River and the Georges River are the two major tributaries that flow into the bay...

, New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

.

Shipwreck

For the next four months, Cook charted the coast of Australia, heading generally northward. Just before 11 pm on 11 June 1770, the ship struck a reef, today called Endeavour ReefEndeavour Reef

Endeavour Reef is a coral reef within the Great Barrier Reef. The reef is about long and runs in an east-west direction. The center of the reef is located at . It is about south-east of the Hope Islands in the Hope Islands National Park and off the mainland.It was encountered by Lieutenant...

, within the Great Barrier Reef

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world'slargest reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over 2,600 kilometres over an area of approximately...

system. The sails were immediately taken down, a kedging anchor set and an unsuccessful attempt was made to drag the ship back to open water. The reef Endeavour had struck rose so steeply from the seabed that although the ship was hard aground, Cook measured depths up to 70 feet (21.3 m) less than one ship's length away.

Cook then ordered that the ship be lightened to help her float off the reef. Iron and stone ballast, spoiled stores and all but four of the ship's guns were thrown overboard, and the ship's drinking water pumped out. Buoy

Buoy

A buoy is a floating device that can have many different purposes. It can be anchored or allowed to drift. The word, of Old French or Middle Dutch origin, is now most commonly in UK English, although some orthoepists have traditionally prescribed the pronunciation...

s were attached to the discarded guns with the intention of retrieving them later, but this proved impractical. Every man on board took turns on the pumps, including Cook and Banks.

When, by Cook's reckoning, about 40 long ton of equipment had been thrown overboard, on the next high tide a second unsuccessful attempt was made to pull the ship free. In the afternoon of 12 June, the longboat carried out two large bower anchors, and block and tackle were rigged to the anchor chains to allow another attempt on the evening high tide. The ship had started to take on water through a hole in her hull. Although the leak would certainly increase once off the reef, Cook decided to risk the attempt and at 10:20 pm the ship was floated on the tide and successfully drawn off. The anchors were retrieved, except for one which could not be freed from the seabed and had to be abandoned.

As expected the leak increased once the ship was off the reef, and all three working pumps had to be continually manned. A mistake occurred in sounding

Sounding line

A sounding line or lead line is a length of thin rope with a plummet, generally of lead, at its end. Regardless of the actual composition of the plummet, it is still called a "lead."...

the depth of water in the hold, when a new man measured the length of a sounding line from the outside plank of the hull where his predecessor had used the top of the cross-beams. The mistake suggested the water depth had increased by about 18 inches (45.7 cm) between soundings, sending a wave of fear through the ship. As soon as the mistake was realised, redoubled efforts kept the pumps ahead of the leak.

The prospects if the ship sank were grim. The vessel was 24 miles (38.6 km) from shore and the three ship's boats could not carry the entire crew. Despite this, the journal of Joseph Banks noted the calm efficiency of the crew in the face of danger, contrary to stories he had heard of seamen panicking or refusing command in such circumstances.

Midshipman Jonathon Monkhouse proposed fother

Fother

Fother is an old unit originally a cart-load , but through transference became a measurement for a quantity of lead. It was defined in different ways at different places and times, being about equal to a ton or somewhat more....

ing the ship, as he had previously been on a merchant ship which used the technique successfully. He was entrusted with supervising the task, sewing bits of oakum

Oakum

Oakum is a preparation of tarred fiber used in shipbuilding, for caulking or packing the joints of timbers in wooden vessels and the deck planking of iron and steel ships, as well as cast iron plumbing applications...

and wool into an old sail, which was then drawn under the ship to allow water pressure to force it into the hole in the hull. The effort succeeded and soon very little water was entering, allowing two of the three pumps to be stopped.

Endeavour then resumed her course northward and parallel to the reef, the crew looking for a safe harbour in which to make repairs. On 13 June, the ship came to a broad watercourse that Cook named the Endeavour River

Endeavour River

The Endeavour River on Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland, Australia, was named in 1770 by Lt. James Cook, R.N., after he was forced to beach his ship, HM Bark Endeavour, for repairs in the river mouth, after damaging it on Endeavour Reef...

. Attempts were made to enter the river mouth, but strong winds and rain prevented Endeavour from crossing the bar until the morning of 17 June. Briefly grounded on a sand spit, she was refloated an hour later and warped into the river proper by early afternoon. The ship was promptly beached on the southern bank and careened

Careening

Careening a sailing vessel is the practice of beaching it at high tide. This is usually done in order to expose one side or another of the ship's hull for maintenance and repairs below the water line when the tide goes out....

to make repairs to the hull. Torn sails and rigging were also replaced and the hull scraped free of barnacles.

An examination of the hull showed that a piece of coral the size of a man's fist had sliced clean through the timbers and then broken off. Surrounded by pieces of oakum from the fother, this coral fragment had helped plug the hole in the hull and preserved the ship from sinking on the reef.

Northward to Batavia

After waiting for the wind, Endeavour resumed her voyage on the afternoon of 5 August 1770, reaching the northern-most point of Cape York PeninsulaCape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large remote peninsula located in Far North Queensland at the tip of the state of Queensland, Australia, the largest unspoilt wilderness in northern Australia and one of the last remaining wilderness areas on Earth...

fifteen days later. On 22 August, Cook was rowed ashore to a small coastal island to proclaim British sovereignty over the eastern Australian mainland. Cook christened his landing place Possession Island

Possession Island National Park

Possession Island is a small island in the Torres Strait Islands group off the coast of far northern Queensland, Australia.The island is known as Bedanug or Bedhan Lag by its Sovereign Original inhabitants, the Kaurareg people. During his first voyage of discovery James Cook sailed northwards...

, and the occasion was marked by ceremonial volleys of gunfire from the shore and Endeavour′s deck.

Torres Strait

The Torres Strait is a body of water which lies between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is approximately wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost continental extremity of the Australian state of Queensland...

between Australia and New Guinea

New Guinea

New Guinea is the world's second largest island, after Greenland, covering a land area of 786,000 km2. Located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, it lies geographically to the east of the Malay Archipelago, with which it is sometimes included as part of a greater Indo-Australian Archipelago...

, earlier navigated by Luis Váez de Torres in 1606. To keep Endeavour’s voyages and discoveries secret, Cook confiscated the log books and journals of all on board and ordered them to remain silent about where they had been.

After a three-day layover off the island of Savu

Savu

Savu is the largest of a group of three islands, situated midway between Sumba and Rote, west of Timor, in Indonesia's eastern province, East Nusa Tenggara. Ferries connect the islands to Waingapu, on Sumba, and Kupang, in West Timor...

, Endeavour sailed on to Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies was a Dutch colony that became modern Indonesia following World War II. It was formed from the nationalised colonies of the Dutch East India Company, which came under the administration of the Netherlands government in 1800....

, on 10 October. A day later the ship was struck by lightning during a sudden tropical storm, but serious damage was avoided thanks to the rudimentary "electric chain" or lightning rod

Lightning rod

A lightning rod or lightning conductor is a metal rod or conductor mounted on top of a building and electrically connected to the ground through a wire, to protect the building in the event of lightning...

that Cook had ordered rigged to Endeavour’s mast.

The ship remained in very poor condition following her grounding on the Great Barrier Reef in June. The ship′s carpenter John Seetterly observed that she was "very leaky – makes from twelve to six inches an hour, occasioned by her main keel being wounded in many places, false keel

False keel

The false keel was a timber, forming part of the hull of a wooden sailing ship. Typically 6 inches thick for a 74-gun ship in the 19th century, the false keel was constructed in several pieces, which were scarphed together, and attached to the underside of the keel by iron staples...

gone from beyond the midships. Wounded on her larbord side where the greatest leak is but I could not come at it for the water." An inspection of the hull revealed that some unrepaired planks were cut through to within ⅛ inch (3 mm). Cook noted it was a "surprise to every one who saw her bottom how we had kept her above water" for the previous three-month voyage across open seas.

After riding at anchor for two weeks, Endeavour was heaved out of the water on 9 November and laid on her side for repairs. Some damaged timbers were found to be infested with shipworm

Shipworm

Shipworms are not worms at all, but rather a group of unusual saltwater clams with very small shells, notorious for boring into wooden structures that are immersed in sea water, such as piers, docks and wooden ships...

s, which required careful removal to ensure they did not spread throughout the hull. Broken timbers were replaced and the hull recaulked, scraped for shellfish and marine flora, and repainted. Finally, the rigging and pumps were renewed and fresh stores brought aboard for the return journey to England. Repairs and replenishment were completed by Christmas Day 1770, and the next day Endeavour weighed anchor and set sail westward towards the Indian Ocean

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the world's oceanic divisions, covering approximately 20% of the water on the Earth's surface. It is bounded on the north by the Indian Subcontinent and Arabian Peninsula ; on the west by eastern Africa; on the east by Indochina, the Sunda Islands, and...

.

Return voyage

Though Endeavour was now in good condition, her crew were not. During the ship's stay in Batavia, all but 10 of the 94 people aboard had been taken ill with malariaMalaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

and dysentery

Dysentery

Dysentery is an inflammatory disorder of the intestine, especially of the colon, that results in severe diarrhea containing mucus and/or blood in the faeces with fever and abdominal pain. If left untreated, dysentery can be fatal.There are differences between dysentery and normal bloody diarrhoea...

. By the time Endeavour set sail on 26 December, seven crew members had died and another forty were too sick to attend their duties. Over the following twelve weeks, a further 23 died from disease and were buried at sea, including Spöring, Green, Parkinson, and the ship's surgeon William Monkhouse.

Cook attributed the sickness to polluted drinking water, and ordered that it be purified with lime

Lime (fruit)

Lime is a term referring to a number of different citrus fruits, both species and hybrids, which are typically round, green to yellow in color, 3–6 cm in diameter, and containing sour and acidic pulp. Limes are a good source of vitamin C. Limes are often used to accent the flavors of foods and...

juice, but this had little effect. Jonathan Monkhouse, who had proposed fothering the ship to save her from sinking on the reef, died on 6 February, followed six days later by ship's carpenter John Seetterly, whose skilled repair work in Batavia had allowed Endeavour to resume her voyage. The health of the surviving crew members then slowly improved as the month progressed, with the last deaths from disease being three ordinary seamen on 27 February.

On 13 March 1771, Endeavour rounded the Cape of Good Hope and made port in Cape Town

Cape Town

Cape Town is the second-most populous city in South Africa, and the provincial capital and primate city of the Western Cape. As the seat of the National Parliament, it is also the legislative capital of the country. It forms part of the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality...

two days later. Those still sick were taken ashore for treatment. The ship remained in port for four weeks awaiting the recovery of the crew and undergoing minor repairs to her masts. On 15 April, the sick were brought back on board along with ten recruits from Cape Town, and Endeavour resumed her homeward voyage. The English mainland was sighted on 10 July and Endeavour entered the port of Dover

Dover

Dover is a town and major ferry port in the home county of Kent, in South East England. It faces France across the narrowest part of the English Channel, and lies south-east of Canterbury; east of Kent's administrative capital Maidstone; and north-east along the coastline from Dungeness and Hastings...

two days later.

Approximately one month after his return, Cook was promoted to the rank of Commander

Commander

Commander is a naval rank which is also sometimes used as a military title depending on the individual customs of a given military service. Commander is also used as a rank or title in some organizations outside of the armed forces, particularly in police and law enforcement.-Commander as a naval...

, and by November 1771 was in receipt of Admiralty Orders for a second expedition

Second voyage of James Cook

The second voyage of James Cook 1772–1775, commissioned by the British government with advice from the Royal Society, was designed to circumnavigate the globe as far south as possible to finally determine whether there was any great southern landmass, or Terra Australis...

, this time aboard HMS Resolution. He was killed during an altercation with native Hawaiians at Kealakekua Bay

Kealakekua Bay

Kealakekua Bay is located on the Kona coast of the island of Hawaii about south of Kailua-Kona.Settled over a thousand years ago, the surrounding area contains many archeological and historical sites such as religious temples, and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places listings on...

on 14 February 1779.

Later service

While Cook was feted for his successful voyage, Endeavour was largely forgotten. Within a week of her return to England, she was directed to Woolwich DockyardWoolwich Dockyard

Woolwich Dockyard was an English naval dockyard founded by King Henry VIII in 1512 to build his flagship Henri Grâce à Dieu , the largest ship of its day....

for refitting as a naval transport. She then made two routine return voyages to the Falkland Islands

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands are an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean, located about from the coast of mainland South America. The archipelago consists of East Falkland, West Falkland and 776 lesser islands. The capital, Stanley, is on East Falkland...

, the first to deliver provisions and the second to bring home the British garrison. She was paid off in September 1774, and in March 1775 was sold by the Navy to shipping magnate J. Mather for £645.

Mather renamed the increasingly decrepit ship Lord Sandwich and returned her to sea for at least one commercial voyage to Archangel

Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk , formerly known as Archangel in English, is a city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina River near its exit into the White Sea in the north of European Russia. The city spreads for over along the banks of the river...

in Russia. In late 1775, he was asked by the Admiralty to provide one of his ships to transport soldiers to North America to help defeat the colonial militia during the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

. Mather offered to return the ageing Lord Sandwich to military service, but her condition was so poor that she was declared unseaworthy. After extensive repairs the ship was finally accepted as a troop transport in February 1776 and embarked a contingent of Hessian soldiers bound for New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

and Rhode Island

Rhode Island

The state of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, more commonly referred to as Rhode Island , is a state in the New England region of the United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area...

. Upon delivery of her human cargo, Lord Sandwich sailed to Newport

Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is a city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island, United States, about south of Providence. Known as a New England summer resort and for the famous Newport Mansions, it is the home of Salve Regina University and Naval Station Newport which houses the United States Naval War...

, which had been occupied by British forces in December 1776. There she was retained at anchor and intermittently used as a prison ship

Prison ship

A prison ship, historically sometimes called a prison hulk, is a vessel used as a prison, often to hold convicts awaiting transportation to penal colonies. This practice was popular with the British government in the 18th and 19th centuries....

under the British flag.

Final resting place

Endeavour’s end came in August 1778, when the British occupation of Newport was threatened by a fleet carrying French soldiers in support of the Continental ArmyContinental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

. The British commander, Captain John Brisbane, determined to blockade Newport Harbor by sinking surplus vessels in its approaches. Between 3 and 6 August, a fleet of Royal Navy frigates and transports, including Lord Sandwich, were scuttled at various locations in Narragansett Bay.

The owners of the sunken vessels were compensated by the Admiralty for the loss of their ships. The Admiralty valuation for the sunken vessel recorded the specifications of Lord Sandwich as matching those of the former Endeavour, including construction in Whitby, a burthen of 368 and 71/94 tons, and re-entry into Navy service on 10 February 1776.

In 1834 a letter appeared in the Providence Journal of Rhode Island, drawing attention to the possible presence of the former Endeavour on the seabed of the bay. This was swiftly disputed by the British consul in Rhode Island, who wrote claiming that Endeavour had been bought from Mather by the French in 1790 and renamed La Liberte. The consul later admitted he had heard this not from the Admiralty, but as hearsay from the former owners of the French ship. It was later suggested the Liberty, which sank off Newport in 1793, was in fact another of Cook's ships, the former HMS Resolution, or another , a naval schooner

Schooner

A schooner is a type of sailing vessel characterized by the use of fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts with the forward mast being no taller than the rear masts....

sold out of service in 1782. A further letter to the Providence Journal stated that a retired English sailor was conducting guided tours of a hulk

Hulk (ship)

A hulk is a ship that is afloat, but incapable of going to sea. Although sometimes used to describe a ship that has been launched but not completed, the term most often refers to an old ship that has had its rigging or internal equipment removed, retaining only its flotational qualities...

on the River Thames

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

as late as 1825, claiming that the ship had once been Cook's Endeavour.

In 1991 the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project, or RIMAP, began research into the identity of the ten transports sunk as part of the Narragansett Bay blockade, including whether the Lord Sandwich recorded as having sunk there was originally Cook's Endeavour. Evidence from the Public Records Office in London confirmed that Endeavour had been renamed Lord Sandwich, had served as a troop transport to North America, and had been scuttled as part of the blockade of Narragansett Bay.

In 1999 a combined research team from RIMAP and the Australian National Maritime Museum began examining known wrecks in the Bay, to determine if any could be Endeavour. In 2000, a site was identified containing the remains of one of the blockaded vessels, partly covered by a separate wreck of a twentieth-century barge. The older remains were those of a vessel of the same size, design and materials of Lord Sandwich, the ex-Endeavour.

Confirmation that Cook's former ship was indeed in Narragansett Bay sparked considerable media and public interest in confirming her location. However, while researchers were able to photograph relics at the site, including a cannon, an anchor and part of an eighteenth-century ceramic teapot, too little evidence existed to definitively establish that this particular wreck had been Cook's ship. In 2006, the Director of RIMAP announced that the wreck would not be raised.

Endeavour relics

In addition to the search for the remains of the ship herself, there was considerable Australian interest in locating relics of the ship′s south Pacific voyage. In 1886, the Working Men's Progress Association of Cooktown sought to recover the six cannons thrown overboard when Endeavour grounded on the Great Barrier Reef. A £300 reward was offered for anyone who could locate and recover the guns, but searches that year and the next were fruitless and the money went unclaimed. Remains of equipment left at Endeavour River were discovered in around 1900, and in 1913 the crew of a merchant steamer erroneously claimed to have recovered an Endeavour cannon from shallow water near the Reef.In 1937, a small part of Endeavour’s keel was gifted to the Australian Government by philanthropist Charles Wakefield in his capacity as President of the Admiral Arthur Phillip Memorial

Arthur Phillip

Admiral Arthur Phillip RN was a British admiral and colonial administrator. Phillip was appointed Governor of New South Wales, the first European colony on the Australian continent, and was the founder of the settlement which is now the city of Sydney.-Early life and naval career:Arthur Phillip...

. Australian Prime Minister Joseph Lyons

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons, CH was an Australian politician. He was Labor Premier of Tasmania from 1923 to 1928 and a Minister in the James Scullin government from 1929 until his resignation from the Labor Party in March 1931...

described the section of keel as "intimately associated with the discovery and foundation of Australia".

Searches were resumed for the lost Endeavour Reef cannons, but expeditions in 1966, 1967, and 1968 were unsuccessful. They were finally recovered in 1969 by a research team from the American Academy of Natural Sciences

Academy of Natural Sciences

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, is the oldest natural science research institution and museum in the New World...

, using a sophisticated magnetometer

Magnetometer

A magnetometer is a measuring instrument used to measure the strength or direction of a magnetic field either produced in the laboratory or existing in nature...

to locate the cannons, a quantity of iron ballast and the abandoned bower anchor. Conservation work on the cannons was undertaken by the Australian National Maritime Museum, after which two of the cannons were displayed at its headquarters in Sydney's Darling Harbour. A third cannon and the bower anchor were displayed at the James Cook Museum in Cooktown, with the remaining three at maritime museums in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, Philadelphia, and the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is the national museum and art gallery of New Zealand, located in Wellington. It is branded and commonly known as Te Papa and Our Place; "Te Papa Tongarewa" is broadly translatable as "the place of treasures of this land".The museum's principles...

in Wellington

Wellington

Wellington is the capital city and third most populous urban area of New Zealand, although it is likely to have surpassed Christchurch due to the exodus following the Canterbury Earthquake. It is at the southwestern tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Rimutaka Range...

.

Replica vessel

In January 1988, to commemorate the Australian BicentenaryAustralian Bicentenary

The bicentenary of Australia was celebrated in 1970 on the 200th anniversary of Captain James Cook landing and claiming the land, and again in 1988 to celebrate 200 years of permanent European settlement.-1970:...

of European settlement in Australia, work began in Fremantle

Fremantle, Western Australia

Fremantle is a city in Western Australia, located at the mouth of the Swan River. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle was the first area settled by the Swan River colonists in 1829...

, Western Australia

Western Australia

Western Australia is a state of Australia, occupying the entire western third of the Australian continent. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Great Australian Bight and Indian Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east and South Australia to the south-east...

on a replica of Endeavour. Financial difficulties delayed completion until December 1993, and the vessel was not commissioned until April 1994. The replica vessel commenced her maiden voyage in October of that year, sailing to Sydney Harbour and then following Cook's path from Botany Bay northward to Cooktown. From 1996 to 2002, the replica retraced Cook's ports of call around the world, arriving in the original Endeavour’s home port of Whitby in June 2002. Footage of waves shot while rounding Cape Horn on this voyage was later used in digitally composited scenes in the 2003 film Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World is a 2003 film directed by Peter Weir, starring Russell Crowe as Jack Aubrey, with Paul Bettany as Stephen Maturin and released by 20th Century Fox, Miramax Films and Universal Studios...

.

The replica Endeavour visited various European ports before undertaking her final ocean voyage from Whitehaven to Sydney Harbour

Port Jackson

Port Jackson, containing Sydney Harbour, is the natural harbour of Sydney, Australia. It is known for its beauty, and in particular, as the location of the Sydney Opera House and Sydney Harbour Bridge...

on 8 November 2004. Her arrival in Sydney was delayed when she ran aground in Botany Bay, a short distance from the point where Cook first set foot in Australia 235 years earlier. The replica Endeavour finally entered Sydney Harbour on 17 April 2005, having travelled 170000 nautical miles (314,840 km), including twice around the world. Ownership of the replica was transferred to the Australian National Maritime Museum in 2005 for permanent service as a museum ship

Museum ship

A museum ship, or sometimes memorial ship, is a ship that has been preserved and converted into a museum open to the public, for educational or memorial purposes...

in Sydney's Darling Harbour.

River Tees

The River Tees is in Northern England. It rises on the eastern slope of Cross Fell in the North Pennines, and flows eastwards for 85 miles to reach the North Sea between Hartlepool and Redcar.-Geography:...

in Stockton-on-Tees

Stockton-on-Tees

Stockton-on-Tees is a market town in north east England. It is the major settlement in the unitary authority and borough of Stockton-on-Tees. For ceremonial purposes, the borough is split between County Durham and North Yorkshire as it also incorporates a number of smaller towns including...

. While this reflects the external dimensions of Cook's vessel, this replica was constructed with a steel rather than a timber frame, has one less internal deck than the original, and is not designed to be put to sea.

The Russell

Russell, New Zealand

Russell, formerly known as Kororareka, was the first permanent European settlement and sea port in New Zealand. It is situated in the Bay of Islands, in the far north of the North Island. As at the 2006 census it had a resident population of 816, an increase of 12 from 2001...

Museum, in the Bay of Islands

Bay of Islands

The Bay of Islands is an area in the Northland Region of the North Island of New Zealand. Located 60 km north-west of Whangarei, it is close to the northern tip of the country....

, New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

has a sea-going one-fifth scale replica of the Endeavour. It was built in Auckland and during 1969 – 70 it sailed some 15000 miles (24,140.1 km) in New Zealand and Australia.

See also

- European and American voyages of scientific explorationEuropean and American voyages of scientific explorationThe era of European and American voyages of scientific exploration followed the Age of Discovery and were inspired by a new confidence in science and reason that arose in the Age of Enlightenment...

- Blue LatitudesBlue LatitudesBlue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before , or Into the Blue: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before , is a travel book by Tony Horwitz....

, a travel book by Tony HorwitzTony HorwitzTony Horwitz is an American journalist and writer. His works include Blue Latitudes or Into the Blue, One for the Road, Confederates In The Attic, Baghdad Without A Map, and A Voyage Long and Strange: Rediscovering the New World. His next book Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked...

Footnotes

In today's terms, this equates to a valuation for Endeavour of approximately £265,000 and a purchase price of £326,400.Provisions loaded at the outset of the voyage included 6,000 pieces of pork and 4,000 of beef, nine tons of bread, five tons of flour, three tons of sauerkraut, one ton of raisins and sundry quantities of cheese, salt, peas, oil, sugar and oatmeal. Alcohol supplies consisted of 250 barrels of beer, 44 barrels of brandy and 17 barrels of rum.

The shanghaiied man was John Thurman, born in New York but a British subject and therefore eligible for involuntary impressment aboard a Royal Navy vessel. Thurman journeyed with Endeavour to Tahiti where he was promoted to the position of sailmaker's assistant, and then to New Zealand and Australia. He died of disease on 3 February 1771, during the voyage between Batavia and Cape Town.

Some of Endeavours crew also contracted an unspecified lung infection. Cook noted that disease of various kinds had broken out aboard every ship berthed in Batavia at the time, and that "this seems to have been a year of General sickness over most parts of India" and in England.

Navy vessels scuttled in Narragansett Bay from 3 August to 6 August 1778 included the frigates Juno 32, Lark

HMS Lark (1762)

HMS Lark was a 32-gun Richmond-class fifth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy. She was launched in 1762 and destroyed 1778 during the American Revolutionary War, in Narragansett Bay...

32, Orpheus

HMS Orpheus (1773)

HMS Orpheus was a British Modified Lowestoffe-class fifth-rate frigate, ordered on 25 December 1770 as one of five fifth-rate frigates of 32 guns each contained in the emergency frigate-building programme inaugurated when the likelihood of war with Spain arose over the ownership of the Falkland...

32, and Cerberus 28; the galley Alarm, and the transports Betty, Britannia, Earl of Oxford, Good Intent, Grand Duke of Russia, Lord Sandwich, Malaga, Rachel and Mary, Susanna, and Union.

External links

- Picture of the recovered anchor and team, in Great Scot newsletter of Scotch College (Melbourne)Scotch College, MelbourneScotch College, Melbourne is an independent, Presbyterian, day and boarding school for boys, located in Hawthorn, an inner-eastern suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia....

, April 2004 - Flyer from the Australian National Maritime Museum about the HMB Endeavour replica (PDF)

- Endeavour runs aground, Pictures and information about the discovery of Endeavours ballast and cannons on the ocean floor off Queensland, Australia, in 1969, National Museum of AustraliaNational Museum of AustraliaThe National Museum of Australia was formally established by the National Museum of Australia Act 1980. The National Museum preserves and interprets Australia's social history, exploring the key issues, people and events that have shaped the nation....