February 1946

Encyclopedia

January

– February – March

– April

– May

– June

– July

– August

– September

– October

– November

– December

The following events occurred in February 1946.

The following events occurred in February 1946.

January 1946

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in January 1946.-January 1, 1946 :...

– February – March

March 1946

January – February – March – April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in March, 1946.-March 1, 1946 :...

– April

April 1946

January – February – March - April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in April, 1946:-April 1, 1946 :...

– May

May 1946

January – February – March - April – May – June – July – August – September – October – November – DecemberThe following events occurred in May, 1946:-May 1, 1946 :...

– June

June 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in June, 1946:-June 1, 1946 :...

– July

July 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in July 1946:-July 1, 1946 :...

– August

August 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in August 1946:-August 1, 1946 :...

– September

September 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in September 1946:-September 1, 1946 :...

– October

October 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in October 1946:-October 1, 1946 :...

– November

November 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - November - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in November 1946:-November 1, 1946 :...

– December

December 1946

January - February - March - April – May - June - July - August - September - October - November — DecemberThe following events occurred in December 1946:-December 1, 1946 :...

February 1, 1946 (Friday)

- Trygve LieTrygve LieTrygve Halvdan Lie was a Norwegian politician, labour leader, government official and author. He served as Norwegian Foreign minister during the critical years of the Norwegian government in exile in London from 1940 to 1945. From 1946 to 1952 he was the first Secretary-General of the United...

was sworn in as the first Secretary General of the United Nations. - SyriaSyriaSyria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

and the Soviet Union secretly signed a treaty for military advisers to come to Syria. A treaty between the USSR and Lebanon was signed two days later. - Zoltán TildyZoltán TildyZoltán Tildy , was an influential leader of Hungary, who served as Prime Minister from 1945–1946 and President from 1946-1948 in the post-war period before the seizure of power by Soviet-backed communists....

was sworn in to office as the first President of Hungary, and Ferenc NagyFerenc NagyFerenc Nagy was a Hungarian politician of the Smallholders Party. He was a Speaker of the National Assembly of Hungary from 29 November 1945 to 5 February 1946 and a member of the High National Council from 7 December 1945 to 2 February 1946.Later he served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 4...

succeeded Tildy as Prime Minister. Both were forced out by the Communist party within two years.

February 2, 1946 (Saturday)

- The Soviet Union formally annexed the Japanese Kuril IslandsKuril IslandsThe Kuril Islands , in Russia's Sakhalin Oblast region, form a volcanic archipelago that stretches approximately northeast from Hokkaidō, Japan, to Kamchatka, Russia, separating the Sea of Okhotsk from the North Pacific Ocean. There are 56 islands and many more minor rocks. It consists of Greater...

. - Two unusually large sunspots disrupted radio communication between North America and Europe between and EST.

- A fire in a retirement home in Garfield Heights, OhioGarfield Heights, OhioGarfield Heights is a city in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, United States. The population was 28,849 at the time of the 2010 census.-Geography:Garfield Heights is located at ....

, killed 33 people. - Born: Alpha Oumar KonaréAlpha Oumar KonaréAlpha Oumar Konaré was the President of Mali for two five-year terms , and was Chairperson of the African Union Commission from 2003 to 2008.-Scholarly career:...

, third President of Mali (1992–2002) and Blake ClarkBlake ClarkBlake Clark is an American actor, voice artist, comedian, and veteran of the Vietnam War, having served as a Captain with the 101st Airborne Division....

, American actor and comedian - Died: Rondo HattonRondo HattonRondo Hatton was an American actor who had a brief, but prolific career playing thuggish bit parts in many Hollywood B-movies. He was known for his brutish facial features which were the result of acromegaly, a disorder of the pituitary gland.-Biography:Hatton was born Rondo K...

, 51, American horror movie star

February 3, 1946 (Sunday)

- NBC Radio commentator Drew PearsonDrew Pearson (journalist)Andrew Russell Pearson , known professionally as Drew Pearson, was one of the best-known American columnists of his day, noted for his muckraking syndicated newspaper column "Washington Merry-Go-Round," in which he attacked various public persons, sometimes with little or no objective proof for his...

broke the news of what would become known as the "Gouzenko Affair": a Soviet spy ring had been operating in Canada, and that the spy agency GRUGRUGRU or Glavnoye Razvedyvatel'noye Upravleniye is the foreign military intelligence directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation...

had been transmitting American atomic secrets from OttawaOttawaOttawa is the capital of Canada, the second largest city in the Province of Ontario, and the fourth largest city in the country. The city is located on the south bank of the Ottawa River in the eastern portion of Southern Ontario...

to Moscow. - Died: Friedrich JeckelnFriedrich JeckelnFriedrich Jeckeln was an SS-Obergruppenführer who served as an SS and Police Leader in the occupied Soviet Union during World War II...

, 51, SS commander during the Nazi occupation of the Soviet Union, was hanged in public at Pobeda Square in RigaRigaRiga is the capital and largest city of Latvia. With 702,891 inhabitants Riga is the largest city of the Baltic states, one of the largest cities in Northern Europe and home to more than one third of Latvia's population. The city is an important seaport and a major industrial, commercial,...

, along with five of his officers. Jeckeln oversaw the deaths of more than 250,000 people, mostly Jewish, during the Second World War.

February 4, 1946 (Monday)

- National weather forecasts returned to American newspapers after four years. Publication of maps had ceased on December 15, 1941, a week after the United States entered World War II.

February 5, 1946 (Tuesday)

- The first scheduled Trans-Atlantic commercial airplane flight was made when the "Star of Paris", a TWA ConstellationLockheed ConstellationThe Lockheed Constellation was a propeller-driven airliner powered by four 18-cylinder radial Wright R-3350 engines. It was built by Lockheed between 1943 and 1958 at its Burbank, California, USA, facility. A total of 856 aircraft were produced in numerous models, all distinguished by a...

, took off at from New York's La Guardia airport. The plane landed in Paris 14 hours and 48 minutes later. - Plaza MéxicoPlaza MéxicoThe Plaza México, situated in Mexico City, is the world's largest bullring. This 48,000-seat facility is usually dedicated to bullfighting, but many boxing fights have been held there as well, including Julio César Chávez's third bout with Frankie Randall...

, the world's largest (55,000 seats) bullringBullringA bullring is an arena where bullfighting is performed. Bullrings are often associated with Spain, but they can also be found in neighboring countries and the New World...

, was opened in Mexico CityMexico CityMexico City is the Federal District , capital of Mexico and seat of the federal powers of the Mexican Union. It is a federal entity within Mexico which is not part of any one of the 31 Mexican states but belongs to the federation as a whole...

. - The Tishomingo National Wildlife RefugeTishomingo National Wildlife RefugeThe Tishomingo National Wildlife Refuge is part of the United States system of National Wildlife Refuges. It is located in southern Johnston and northeastern Marshall counties in eastern Oklahoma, near the upper Washita arm of Lake Texoma....

was established in OklahomaOklahomaOklahoma is a state located in the South Central region of the United States of America. With an estimated 3,751,351 residents as of the 2010 census and a land area of 68,667 square miles , Oklahoma is the 28th most populous and 20th-largest state...

by order of President Truman. - Born: Charlotte RamplingCharlotte RamplingCharlotte Rampling, OBE is an English actress. Her career spans four decades in English-language as well as French and Italian cinema.- Early life :...

, British film actress, in SturmerSturmer"Sturmer" might refer to:* Andy Sturmer is a singer, songwriter, and music producer.*Sturmer, Essex is a village in England.*A Sturmer Pippin is a type of apple.*Sturmer...

, EssexEssexEssex is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East region of England, and one of the home counties. It is located to the northeast of Greater London. It borders with Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent to the South and London to the south west... - Died: George ArlissGeorge ArlissGeorge Arliss was an English actor, author and filmmaker who found success in the United States. He was the first British actor to win an Academy Award.-Life and career:...

, 77, Oscar-winning British actor

February 6, 1946 (Wednesday)

- Charles Vyner BrookeCharles Vyner BrookeVyner, Rajah of Sarawak, GCMG was the third and final White Rajah of Sarawak.-Early life:...

, the "White Rajah" of the State of SarawakSarawakSarawak is one of two Malaysian states on the island of Borneo. Known as Bumi Kenyalang , Sarawak is situated on the north-west of the island. It is the largest state in Malaysia followed by Sabah, the second largest state located to the North- East.The administrative capital is Kuching, which...

, ceded the state's sovereignty to the United Kingdom as a British Crown Colony. Sarawak is now part of Malaysia. He would pass away on July 1.

February 7, 1946 (Thursday)

- In its colony in VietnamVietnamVietnam – sometimes spelled Viet Nam , officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam – is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and the South China Sea –...

, the military forces of France made a large scale assault to recapture the Bến Tre ProvinceBen Tre ProvinceBến Tre is a province of Vietnam. It is one of the country's southern provinces, being situated in the delta of the Mekong River.-Administration:Politically, Ben Tre is divided into eight districts:*Ba Tri*Bình Đại*Châu Thành*Chợ Lách*Giồng Trôm...

, which had been under control of the Viet MinhViet MinhViệt Minh was a national independence coalition formed at Pac Bo on May 19, 1941. The Việt Minh initially formed to seek independence for Vietnam from the French Empire. When the Japanese occupation began, the Việt Minh opposed Japan with support from the United States and the Republic of China...

since August 25, 1945. The province was quickly brought back under French rule, but guerilla activity continued.

February 8, 1946 (Friday)

- Kim Il-sungKim Il-sungKim Il-sung was a Korean communist politician who led the Democratic People's Republic of Korea from its founding in 1948 until his death in 1994. He held the posts of Prime Minister from 1948 to 1972 and President from 1972 to his death...

was elected Chairman of the Interim People's Committee in the Soviet occupied portion of KoreaKoreaKorea ) is an East Asian geographic region that is currently divided into two separate sovereign states — North Korea and South Korea. Located on the Korean Peninsula, Korea is bordered by the People's Republic of China to the northwest, Russia to the northeast, and is separated from Japan to the...

. Kim, who led the northern branch of the Korean Communist Party, would become the first leader of North KoreaNorth KoreaThe Democratic People’s Republic of Korea , , is a country in East Asia, occupying the northern half of the Korean Peninsula. Its capital and largest city is Pyongyang. The Korean Demilitarized Zone serves as the buffer zone between North Korea and South Korea...

. - Died: Miles ManderMiles ManderMiles Mander , born Lionel Henry Mander , was a well-known and versatile English character actor of the early Hollywood cinema, also a film director and producer, and a playwright and novelist.-Early life:Miles Mander was the second son of Theodore Mander, builder of Wightwick Manor, of the prominent...

, 57, English actor and director (b. 1888)

February 9, 1946 (Saturday)

- In what has been described as the beginning of the Cold WarCold WarThe Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

, Soviet leader Joseph StalinJoseph StalinJoseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

addressed a national radio audience in his first major public speech after the end of World War II. Stalin said that another war was inevitable because of the "capitalist development of the world economy", and that the USSR would need to concentrate on national defense in advance of a war with the Western nations. - In the most well-known example of a recurrent nova, T Coronae BorealisT Coronae BorealisT Coronae Borealis , informally nicknamed the Blaze Star, is a recurring nova in the constellation Corona Borealis. It normally has a magnitude of about 10, which is near the limit of typical binoculars. It has been seen to outburst twice, reaching magnitude 2.0 on May 12, 1866 and magnitude 3.0...

, nicknamed the "blaze star", was seen to flare up almost 80 years after a nova seen on May 12, 1866. - Charles "Lucky" Luciano, an American Mafia boss, was transported from a New York prison to an ocean liner, and deported to his native Italy.

February 10, 1946 (Sunday)

- In the first election in the Soviet Union since 1937, there was a reported turnout of 101,450,936 voters (99.7% of those eligible). For the 682 deputies of the Soviet of the UnionSoviet of the UnionSoviet of the Union , was one of the two chambers of the Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, elected on the basis of universal, equal and direct suffrage by secret ballot in accordance with the principles of Soviet democracy, and with the rule that there be one deputy for...

, and the 657 members of the Soviet of NationalitiesSoviet of NationalitiesThe Soviet of Nationalities , was one of the two chambers of the Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, elected on the basis of universal, equal and direct suffrage by secret ballot in accordance with the principles of Soviet democracy...

, the candidates were unopposed and the choice was yes-or-no. Of the 1,339 candidates, there were 254 who were not Communist Party members. - The ocean liner Queen Mary docked at Pier 90 in New York City, bringing 1,666 war brides and their 668 children.

- Hubertus van Mook, the Governor-General of the Dutch East IndiesGovernor-General of the Dutch East IndiesThe Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies represented the Dutch rule in the Dutch East Indies between 1610 and Dutch recognition of the independence of Indonesia in 1949.The first Governors-General were appointed by the Dutch East India Company...

, proposed a plan for IndonesiaIndonesiaIndonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

's people to choose independence or Dutch citizenship as part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. - Commodore Ben Wyatt, Military Governor of the Marshall IslandsMarshall IslandsThe Republic of the Marshall Islands , , is a Micronesian nation of atolls and islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, just west of the International Date Line and just north of the Equator. As of July 2011 the population was 67,182...

, informed the 167 residents of the Bikini AtollBikini AtollBikini Atoll is an atoll, listed as a World Heritage Site, in the Micronesian Islands of the Pacific Ocean, part of Republic of the Marshall Islands....

that they would be relocated, so that atomic bomb testing could take place. Wyatt told the villagers that their sacrifice was "for the good of mankind and to end all wars".

February 11, 1946 (Monday)

- The Revised Standard VersionRevised Standard VersionThe Revised Standard Version is an English translation of the Bible published in the mid-20th century. It traces its history to William Tyndale's New Testament translation of 1525. The RSV is an authorized revision of the American Standard Version of 1901...

of the New TestamentNew TestamentThe New Testament is the second major division of the Christian biblical canon, the first such division being the much longer Old Testament....

was formally introduced by the International Council of Religious Education at its 1946 meeting, at Central High School in Columbus, OhioColumbus, OhioColumbus is the capital of and the largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio. The broader metropolitan area encompasses several counties and is the third largest in Ohio behind those of Cleveland and Cincinnati. Columbus is the third largest city in the American Midwest, and the fifteenth largest city...

. - Rioting began in India after Rashid Ali, an officer in the resistance group the Indian National ArmyIndian National ArmyThe Indian National Army or Azad Hind Fauj was an armed force formed by Indian nationalists in 1942 in Southeast Asia during World War II. The aim of the army was to overthrow the British Raj in colonial India, with Japanese assistance...

, was sentenced by the colonial authorities to seven years in prison. - The Yalta Agreement was published one year to the day after it had been signed, in simultaneous releases in Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

(9:00 am), London , and Moscow .

February 12, 1946 (Tuesday)

- Sgt. Isaac WoodardIsaac WoodardIsaac Woodard, Jr., often written Isaac Woodward, was an African American World War II veteran whose 1946 beating and maiming, hours after being discharged from the United States Army, sparked national outrage and galvanized the civil rights movement in the United States.Still in uniform, Woodard...

, an African-American U.S. Army veteran, was beaten and blinded by the police chief in Batesburg, South Carolina. Woodard's maiming attracted national attention on Orson WellesOrson WellesGeorge Orson Welles , best known as Orson Welles, was an American film director, actor, theatre director, screenwriter, and producer, who worked extensively in film, theatre, television and radio...

's radio show, and was later dramatized in the 1958 Welles movie Touch of EvilTouch of EvilTouch of Evil is a 1958 American crime thriller film, written, directed by, and co-starring Orson Welles. The screenplay was loosely based on the novel Badge of Evil by Whit Masterson...

, as well as in Woody GuthrieWoody GuthrieWoodrow Wilson "Woody" Guthrie is best known as an American singer-songwriter and folk musician, whose musical legacy includes hundreds of political, traditional and children's songs, ballads and improvised works. He frequently performed with the slogan This Machine Kills Fascists displayed on his...

's song The Blinding of Isaac Woodard. Woodard died in 1992. His assailant, Lindwood Shull, was acquitted by a federal court, and lived until 1997.

- The DuMont Television NetworkDuMont Television NetworkThe DuMont Television Network, also known as the DuMont Network, DuMont, Du Mont, or Dumont was one of the world's pioneer commercial television networks, rivalling NBC for the distinction of being first overall. It began operation in the United States in 1946. It was owned by DuMont...

made the first network telecast, transmitting, by cable, video and audio of Lincoln's Birthday celebrations from its station in Washington, D.C. (W3XWTWTTGWTTG, channel 5, is an owned-and-operated television station of the Fox Broadcasting Company, located in the American capital city of Washington, D.C...

), to its New York affiliate, WABDWNYWWNYW, virtual channel 5 , is the flagship television station of the News Corporation-owned Fox Broadcasting Company, located in New York City. The station's transmitter is atop the Empire State Building and its studio facilities are located in the Yorkville section of Manhattan...

. The NBC and CBS stations in New York also received the DuMont broadcast. - Trans Australia AirlinesTrans Australia AirlinesTrans Australia Airlines or TAA, was one of the two major Australian domestic airlines between its inception in 1946 and its sale to Qantas in May 1996. During that period TAA played a major part in the development of the Australian air transport industry...

made its first flight. - In advance of the presidential election in ArgentinaArgentinaArgentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

, the U.S. State Department issued a 121 page "blue book", with evidence that ArgentinaArgentinaArgentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

, and candidate Juan PerónJuan PerónJuan Domingo Perón was an Argentine military officer, and politician. Perón was three times elected as President of Argentina though he only managed to serve one full term, after serving in several government positions, including the Secretary of Labor and the Vice Presidency...

, had aided Nazi GermanyNazi GermanyNazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

during World War II. Perón won the election in spite of the American publication.

February 13, 1946 (Wednesday)

- Harold L. IckesHarold L. IckesHarold LeClair Ickes was a United States administrator and politician. He served as United States Secretary of the Interior for 13 years, from 1933 to 1946, the longest tenure of anyone to hold the office, and the second longest serving Cabinet member in U.S. history next to James Wilson. Ickes...

, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior since 1933, resigned in protest after President Truman said that Ickes could have been "wrong" in testimony given to a U.S. Senate committee about Truman's nominee for Undersecretary of the Navy. Ickes wrote "I cannot stay on when you, in effect, have expressed a lack of confidence in me." - Born: Colin MatthewsColin MatthewsColin Matthews OBE is an English composer of classical music.-Early life and education:Matthews was born in London in 1946; his older brother is the composer David Matthews. He read classics at the University of Nottingham, and then studied composition there with Arnold Whittall, and with Nicholas...

, British composer, in London

February 14, 1946 (Thursday)

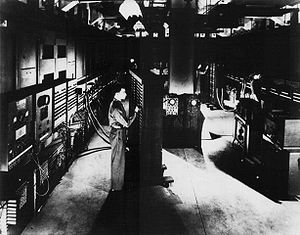

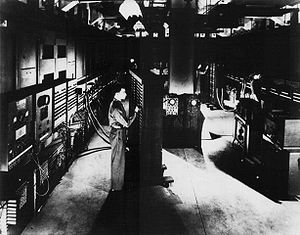

- ENIACENIACENIAC was the first general-purpose electronic computer. It was a Turing-complete digital computer capable of being reprogrammed to solve a full range of computing problems....

, the Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer, was introduced to the public by the U.S. Army, in a press conference at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The world's first electronic computer weighed 30 tons, had 18,000 vacuum tubes, and was 8 feet tall, 3 feet deep, and 100 feet long. One of the computer's first tests was computing trajectories for rocket launching, "completing in ten days a job which would have required three months of concentrated effort by a mathematician". - The Bank of EnglandBank of EnglandThe Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694, it is the second oldest central bank in the world...

was nationalisedNationalizationNationalisation, also spelled nationalization, is the process of taking an industry or assets into government ownership by a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to private assets, but may also mean assets owned by lower levels of government, such as municipalities, being...

, with the signing of a 250 page bill by King George VI. - Born: Gregory HinesGregory HinesGregory Oliver Hines was an American actor, singer, dancer and choreographer.-Early years:Born in New York City, Hines and his older brother Maurice started dancing at an early age, studying with choreographer Henry LeTang...

, American dancer and actor, in New York, (d. 2003), and Bernard DowiyogoBernard DowiyogoHE Bernard Annen Auwen Dowiyogo was President of the Republic of Nauru.-Background and early career:He first became an elected member of Nauru's 18-seat parliament in 1973...

, President of NauruPresident of NauruThe President of Nauru is elected by Parliament from amongst its members. He is both the head of state and head of government of Nauru. Nauru's unicameral Parliament has 18 members, with an electoral term of 3 years. Political parties only play a minor role in Nauru politics, and there has often...

, 1989–95 (d. 2003)

February 15, 1946 (Friday)

- Twenty-two current and former Canadian government employees were arrested by the Royal Canadian Mounted PoliceRoyal Canadian Mounted PoliceThe Royal Canadian Mounted Police , literally ‘Royal Gendarmerie of Canada’; colloquially known as The Mounties, and internally as ‘The Force’) is the national police force of Canada, and one of the most recognized of its kind in the world. It is unique in the world as a national, federal,...

, after Soviet defector Igor GouzenkoIgor GouzenkoIgor Sergeyevich Gouzenko was a cipher clerk for the Soviet Embassy to Canada in Ottawa, Ontario. He defected on September 5, 1945, with 109 documents on Soviet espionage activities in the West...

had provided a list of 1,700 North American informants who were providing classified information to the U.S.S.R. - The United Steel Workers of America and the United States Steel Corporation brought an end to the strike that had begun on January 21, with 130,000 employees returning to work on February 18 in return for an 18½ cent per hour wage increase.

- Died: Cornelius Johnson, 32, American high jump record holder; gold medalist 1936; of pneumonia

February 16, 1946 (Saturday)

- The first UN Security Council vetoUnited Nations Security Council veto powerThe United Nations Security Council "power of veto" refers to the veto power wielded solely by the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council , enabling them to prevent the adoption of any "substantive" draft Council resolution, regardless of the level of international support...

was made, as the Soviet Union killed a resolution concerning the withdrawal of British and French forces from Syria and Lebanon. - Frozen french friesFrench friesFrench fries , chips, fries, or French-fried potatoes are strips of deep-fried potato. North Americans tend to refer to any pieces of deep-fried potatoes as fries or French fries, while in the United Kingdom, Australia, Ireland and New Zealand, long, thinly cut slices of deep-fried potatoes are...

were introduced. Pre-fried by Maxson Food Systems of Long Island, New York, and made to be baked in the oven, the product was first sold at Macy's in New York, but were not immediately popular. American per-capita potato consumption had declined since 1910, and was not measured at previous levels until 1962, when french fries were a fast-food restaurant staple. - The Sikorsky S-51, first helicopter sold for commercial rather than military use, was flown for the first time.

February 17, 1946 (Sunday)

- In a policy of preventing Jewish immigration to Palestine, British authorities intercepted the ship Enzo Sereni, with 915 refugees on board. The Zionist group PalmachPalmachThe Palmach was the elite fighting force of the Haganah, the underground army of the Yishuv during the period of the British Mandate of Palestine. The Palmach was established on May 15, 1941...

retaliated three days later with the destruction of a British Coast Guard station. - Died: Dorothy GibsonDorothy GibsonDorothy Gibson was a pioneering American silent film actress, artist's model and singer active in the early 20th century. She is best remembered as a survivor of the sinking of the RMS Titanic.-Early life and career:...

, 56, American silent film star

February 18, 1946 (Monday)

- The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny began at at the port of ColabaColabaColaba is a part of the city of Mumbai, India, and also a Lok Sabha constituency. During Portuguese rule in the 16th century, the island was known as Candil...

near Bombay (now MumbaiMumbaiMumbai , formerly known as Bombay in English, is the capital of the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is the most populous city in India, and the fourth most populous city in the world, with a total metropolitan area population of approximately 20.5 million...

). In the first mutiny in British India since 1857, a group of 1,600 sailors ("ratings") from the HMIS TalwarHMIS TalwarHis Majesty's Indian Ship, HMIS Talwar was the signal training ship of the Royal Indian Navy. A hartal by the ratings of the ship on 18 February 1946, snowballed into a mutiny by the navy personnel of the Royal Indian Navy. The mutiny spilled over to other ships and even on the streets of Bombay...

walked out of the mess hall because of inadequate food, and began to chant, "No food, no work". The next day, another 20,000 ratings in Bombay joined the strike, and over the next days, rioting broke out. Before order was restored on February 24, there were 223 deaths and 1,037 injuries. - Pope Pius XIIPope Pius XIIThe Venerable Pope Pius XII , born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli , reigned as Pope, head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of Vatican City State, from 2 March 1939 until his death in 1958....

announced the appointment of 32 new Roman Catholic cardinals, the first since 1940. Twenty-eight of the appointees received the red hat in Rome on February 21. - A federal judge in CaliforniaCaliforniaCalifornia is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

ruled that segregation in four school districts was unconstitutional. Schools in El Modena, Garden Grove, Westminster and Santa Ana had separated Mexican-American students from English-speaking students. Two months later, California repealed a law permitting segregated schools for Asian-Americans. The decision in Mendez v. WestminsterMendez v. WestminsterMendez, et al v. Westminster School District, et al, 64 F.Supp. 544 , aff'd, 161 F.2d 774 , was a 1946 federal court case that challenged racial segregation in Orange County, California schools...

was upheld on appeal in 1947. - Born: Karen SilkwoodKaren SilkwoodKaren Gay Silkwood was an American labor union activist and chemical technician at the Kerr-McGee plant near Crescent, Oklahoma, United States. Silkwood's job was making plutonium pellets for nuclear reactor fuel rods...

, American activist and subject of 1983 film SilkwoodSilkwoodSilkwood is a 1983 American drama film directed by Mike Nichols. The screenplay by Nora Ephron and Alice Arlen was inspired by the true-life story of Karen Silkwood, who died in a suspicious car accident while investigating alleged wrongdoing at the Kerr-McGee plutonium plant where she...

, in Longview, TexasLongview, TexasLongview is a city in Gregg and Harrison Counties in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2010 Census, the population was 80,455. Most of the city is located in Gregg County, of which it is the county seat; only a small part extends into the western part of neighboring Harrison County. It is...

(d. 1974)

February 19, 1946 (Tuesday)

- The Cabinet Mission to India was announced in the British House of Commons by Lord Pethick-Lawrence, the Secretary of State for IndiaSecretary of State for IndiaThe Secretary of State for India, or India Secretary, was the British Cabinet minister responsible for the government of India and the political head of the India Office...

. He, along with Sir Stafford CrippsStafford CrippsSir Richard Stafford Cripps was a British Labour politician of the first half of the 20th century. During World War II he served in a number of positions in the wartime coalition, including Ambassador to the Soviet Union and Minister of Aircraft Production...

of the Board of Trade, and Albert V. Alexander, the Minister of Defence, would depart on March 15 in order to meet with representatives on the eventual independence of British India.

February 20, 1946 (Wednesday)

- The American Employment Act of 1946, 15 U.S.C. § 1021, was signed into law by President Truman.

- British Prime Minister Clement AttleeClement AttleeClement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

announced plans "to effect the transference of power to responsible India hands by a date not later than June 1948". S.R. Bakshi and Rashmi Pathak, Punjab Through the Ages (Sarup & Sons, 2007), p443 - The Allied Powers government in Japan ended the three century old tradition of "kōshō" licensed prostitution.

February 21, 1946 (Thursday)

- Uprisings against colonial rule took place across Asia, with disturbances in EgyptEgyptEgypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, IndiaIndiaIndia , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

, SingaporeSingaporeSingapore , officially the Republic of Singapore, is a Southeast Asian city-state off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, north of the equator. An island country made up of 63 islands, it is separated from Malaysia by the Straits of Johor to its north and from Indonesia's Riau Islands by the...

and IndonesiaIndonesiaIndonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

. - Americans United for World GovernmentWorld Federalist MovementThe World Federalist Movement is a global citizens movement with member and associate organizations around the world. The WFM International Secretariat is based in New York City across from the United Nations headquarters...

was announced as the new name for the two year old global federalist group Americans United for World Organization. AUWG Chairman Raymond Swing announced that there was need for a world government to control atomic weapons. - Born: Alan RickmanAlan RickmanAlan Sidney Patrick Rickman is an English actor and theatre director. He is a renowned stage actor in modern and classical productions and a former member of the Royal Shakespeare Company...

, English film actor (Harry Potter), in HammersmithHammersmithHammersmith is an urban centre in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in west London, England, in the United Kingdom, approximately five miles west of Charing Cross on the north bank of the River Thames...

, London, and Tyne DalyTyne DalyTyne Daly is an American stage and screen actress, widely known for her work as Detective Mary Beth Lacey in the television series Cagney & Lacey and as Maxine Gray in the television series Judging Amy. She is also known for her role as Alice Henderson in television series Christy...

, American TV and stage actress (Cagney and Lacey), in Madison, WisconsinMadison, WisconsinMadison is the capital of the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Dane County. It is also home to the University of Wisconsin–Madison....

February 22, 1946 (Friday)

- "The Long Telegram" was sent from the U.S. Embassy in Moscow to the U.S. Department of State, and would become the basis of American foreign policy for nearly fifty years. At more than 8,000 words, it was the longest telegraphed message sent to that time. The author, George F. KennanGeorge F. KennanGeorge Frost Kennan was an American adviser, diplomat, political scientist and historian, best known as "the father of containment" and as a key figure in the emergence of the Cold War...

, the chargé d'affairesChargé d'affairesIn diplomacy, chargé d’affaires , often shortened to simply chargé, is the title of two classes of diplomatic agents who head a diplomatic mission, either on a temporary basis or when no more senior diplomat has been accredited.-Chargés d’affaires:Chargés d’affaires , who were...

at the American embassy, was responding to a specific inquiry from the State Department, and his answer was the containment strategy, to keep the Soviet Union from spreading CommunismCommunismCommunism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

further without going to war. Kennan sent the telegram at Moscow time ( EST), and it was received in Washington at 3:52 EST.

February 23, 1946 (Saturday)

- Lt. Gen. Tomoyuki YamashitaTomoyuki YamashitaGeneral was a general of the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II. He was most famous for conquering the British colonies of Malaya and Singapore, earning the nickname "The Tiger of Malaya".- Biography :...

, who led the Japanese conquest of SingaporeSingaporeSingapore , officially the Republic of Singapore, is a Southeast Asian city-state off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, north of the equator. An island country made up of 63 islands, it is separated from Malaysia by the Straits of Johor to its north and from Indonesia's Riau Islands by the...

and the PhilippinesPhilippinesThe Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

, was hanged in ManilaManilaManila is the capital of the Philippines. It is one of the sixteen cities forming Metro Manila.Manila is located on the eastern shores of Manila Bay and is bordered by Navotas and Caloocan to the north, Quezon City to the northeast, San Juan and Mandaluyong to the east, Makati on the southeast,...

for war crimes, followed by Lt. Col. Seichi Ohta, who had headed security for Japan's "thought police" (kempei tai), and interpreter Takuma Higashigi.

February 24, 1946 (Sunday)

- Argentine general election, 1946Argentine general election, 1946The Argentine general election of 1946, the last for which only men were enfranchised, was held on 24 February. Voters chose both the President and their legislators and with a turnout of 83.4%, it produced the following results:-President:aAbstentions....

:Juan PerónJuan PerónJuan Domingo Perón was an Argentine military officer, and politician. Perón was three times elected as President of Argentina though he only managed to serve one full term, after serving in several government positions, including the Secretary of Labor and the Vice Presidency...

won the race for President of ArgentinaPresident of ArgentinaThe President of the Argentine Nation , usually known as the President of Argentina, is the head of state of Argentina. Under the national Constitution, the President is also the chief executive of the federal government and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces.Through Argentine history, the...

in what was considered the first truly open election since 1928. Perón defeated José TamboriniJosé TamboriniJosé Tamborini was an Argentine physician and historically significant politician.-Life and times:José Pascual Tamborini was born in Buenos Aires, in 1886...

, and the Peronist Labour PartyLabour Party (Argentina)The Labour Party was a political party in Argentina. The party was founded by Peronist trade union leaders at the end of October 1945. The party organization was built up around the Peronist unions, and most of its representatives in different elected offices had been recruited from the ranks of...

won 101 of the 158 seats in the Argentine Chamber of DeputiesArgentine Chamber of DeputiesThe Chamber of Deputies is the lower house of the Argentine National Congress. This Chamber holds exclusive rights to create taxes, to draft troops, and to accuse the President, the ministers and the members of the Supreme Court before the Senate....

. - Died: U.S. Representative (since 1933) J. Buell SnyderJ. Buell SnyderJohn Buell Snyder was a Democratic Party member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania.J. Buell Snyder was born on a farm in Upper Turkeyfoot Township, Pennsylvania. He attended summer sessions of Harvard University, and Columbia University in New York City...

, 68, of a heart attack in his hotel room in Pittsburgh; and "Powder River Jack" Lee, 73, rodeo singer, in an auto accident

February 25, 1946 (Monday)

- African American residents of Columbia, TennesseeColumbia, TennesseeColumbia is a city in Maury County, Tennessee, United States. The 2008 population was 34,402 according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates. It is the county seat of Maury County....

, took up arms after white residents sought to lynch James Stephenson, a 19 year old U.S. Navy veteran. Four white police officers were shot and wounded after trying to enter the black section of town, and the Tennessee Highway Patrol moved in the next morning, arresting more than 100 residents, two of whom died in jail. The Civil Rights CongressCivil Rights CongressThe Civil Rights Congress was a civil rights organization formed in 1946 by a merger of the International Labor Defense and the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties. It became known for involvement in civil rights cases such as the Trenton Six and justice for Isaiah Nixon. The CRC...

, a Communist Party USA defense fund, was formed to aid in the defense of the arrest subjects. - Born: Jean TodtJean TodtJean Todt was born on February 25, 1946, in Pierrefort, Cantal, France. After a successful career as a rally co-driver he made his reputation in motor sport management, first with Peugeot Talbot Sport, then with Scuderia Ferrari, before being appointed Chief Executive Officer of Ferrari from 2004...

, French motorsport boss, in PierrefortPierrefortPierrefort is a commune in the Cantal department in the Auvergne region in south=central France.It is approximately from Clermont Ferrand and from Saint-Flour-Geography:...

February 26, 1946 (Tuesday)

- The Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SED)Socialist Unity Party of GermanyThe Socialist Unity Party of Germany was the governing party of the German Democratic Republic from its formation on 7 October 1949 until the elections of March 1990. The SED was a communist political party with a Marxist-Leninist ideology...

was started in the Soviet Zone of Germany, when the Social Democratic Party was pressured to unite with the Communist Party. The SED, Communist in all but name, would rule East Germany for all but the last six months of that nation's existence. - The Scandinavian phenomenon of "ghost rocketsGhost rocketsGhost Rockets Danish Spøgelsesraketter were mysterious rocket- or missile-shaped unidentified flying objects sighted in 1946, mostly in Sweden and nearby countries....

" was first observed, by observers in Finland. Thousands of reported sightings of the unidentified objects were made throughout 1946. - Born: Ahmed ZewailAhmed ZewailAhmed Hassan Zewail is an Egyptian-American scientist who won the 1999 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on femtochemistry. He is the Linus Pauling Chair Professor Chemistry and Professor of Physics at the California Institute of Technology.- Birth and education :Ahmed Zewail was born on...

, Egyptian femtochemistry pioneer and 1999 Nobel Prize in ChemistryNobel Prize in ChemistryThe Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outstanding contributions in chemistry, physics, literature,...

laureate; in Damanhour - Died: George DealeyGeorge DealeyGeorge Bannerman Dealey was a Dallas, Texas, businessman.Dealey was the long-time publisher of The Dallas Morning News. He used his influence to accomplish many goals but will always be remembered primarily for one of them. He crusaded for the redevelopment of a particularly blighted area near...

, 86, Texas philanthropist, and Frank CroweFrank CroweFrancis Trenholm Crowe was the chief engineer of the Hoover Dam. During that time, he was the superintendent of Six Companies, the construction company that oversaw the construction project....

, American engineer.

February 27, 1946 (Wednesday)

- Former U.S. President Herbert HooverHerbert HooverHerbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

was asked by President Harry Truman to assist in persuading Americans to assist in famine relief worldwide.

- After reviewing a report from National Urban LeagueNational Urban LeagueThe National Urban League , formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of African Americans and against racial discrimination in the United States. It is the oldest and largest...

executive Lester GrangerLester GrangerLester Blackwell Granger was an African American civic leader who organized the Los Angeles, California, chapter of the National Urban League ....

's tour of naval bases worldwide, U.S. Navy Secretary James ForrestalJames ForrestalJames Vincent Forrestal was the last Cabinet-level United States Secretary of the Navy and the first United States Secretary of Defense....

issued the order (applying to the United States NavyUnited States NavyThe United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

only), "Effective immediately, all restrictions governing the types of assignments for which Negro naval personnel are eligible are hereby lifted." - U.S. Senator Arthur H. VandenbergArthur H. VandenbergArthur Hendrick Vandenberg was a Republican Senator from the U.S. state of Michigan who participated in the creation of the United Nations.-Early life and family:...

of MichiganMichiganMichigan is a U.S. state located in the Great Lakes Region of the United States of America. The name Michigan is the French form of the Ojibwa word mishigamaa, meaning "large water" or "large lake"....

further set the tone for the Cold WarCold WarThe Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

, in a famous speech in which he asked the rhetorical question, "What is Russia up to now?", and criticized the Truman Administration's policy of appeasement toward the Soviets. Vandenberg, the highest ranking Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, would become its Chairman when the Republican Party won a majority in both houses in the 1946 mid-term elections.

February 28, 1946 (Thursday)

- Ho Chi MinhHo Chi MinhHồ Chí Minh , born Nguyễn Sinh Cung and also known as Nguyễn Ái Quốc, was a Vietnamese Marxist-Leninist revolutionary leader who was prime minister and president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam...

, the newly elected President of VietnamVietnamVietnam – sometimes spelled Viet Nam , officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam – is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and the South China Sea –...

, sent a telegram to U.S. President Harry S. TrumanHarry S. TrumanHarry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

, asking that the United States use its influence to persuade France not to send occupation forces back into Vietnam, and to "interfere urgently in support of our independence". Truman's reply was that the U.S. would support France, and Ho sought assistance from the Soviet Union instead. - Born: Robin CookRobin CookRobert Finlayson Cook was a British Labour Party politician, who was the Member of Parliament for Livingston from 1983 until his death, and notably served in the Cabinet as Foreign Secretary from 1997 to 2001....

, British politician, Leader of the House of Commons, 2001–2003, in BellshillBellshillBellshill is a town in North Lanarkshire, Scotland, 10 miles south east of Glasgow city centre and 37 miles west of Edinburgh. Other nearby towns are Motherwell , Hamilton and Coatbridge . Since 1996, it has been situated in the Greater Glasgow metropolitan area...

; (d. 2005) - Died: Béla ImrédyBéla ImrédyBéla vitéz Imrédy de Ómoravicza was Prime Minister of Hungary from 1938 to 1939....

, 54, former Prime Minister of Hungary, was executed by firing squad for collaboration with the Nazis.