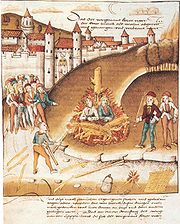

Execution by burning

Encyclopedia

Combustion

Combustion or burning is the sequence of exothermic chemical reactions between a fuel and an oxidant accompanied by the production of heat and conversion of chemical species. The release of heat can result in the production of light in the form of either glowing or a flame...

. As a form of capital punishment

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

, burning has a long history as a method in crimes such as treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

, heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

, and witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

.

According to the Talmud

Talmud

The Talmud is a central text of mainstream Judaism. It takes the form of a record of rabbinic discussions pertaining to Jewish law, ethics, philosophy, customs and history....

, the “burning” mentioned in the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

was done by melting lead and pouring it down the convicted person’s throat, causing immediate death. The particular form of execution by burning in which the condemned is bound to a large stake is more commonly called burning at the stake. Death by burning fell into disfavour among governments in the late 18th century.

Cause of death

If the fire was large (for instance, when a large number of prisonPrison

A prison is a place in which people are physically confined and, usually, deprived of a range of personal freedoms. Imprisonment or incarceration is a legal penalty that may be imposed by the state for the commission of a crime...

ers were executed at the same time), death often came from carbon monoxide poisoning

Carbon monoxide poisoning

Carbon monoxide poisoning occurs after enough inhalation of carbon monoxide . Carbon monoxide is a toxic gas, but, being colorless, odorless, tasteless, and initially non-irritating, it is very difficult for people to detect...

before flames actually caused harm to the body. If the fire was small, however, the convict would burn for some time until death from heatstroke, shock, the loss of blood

Blood

Blood is a specialized bodily fluid in animals that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells....

and/or simply the thermal decomposition

Thermal decomposition

Thermal decomposition, or thermolysis, is a chemical decomposition caused by heat. The decomposition temperature of a substance is the temperature at which the substance chemically decomposes....

of vital body parts.

Calf (anatomy)

In human anatomy the calf is the back portion of the lower leg . In terms of muscle systems, the calf corresponds to the posterior compartment of the leg. Within the posterior compartment, the two largest muscles are known together as the calf muscle and attach to the heel via the Achilles tendon...

, thighs and hands, torso

Torso

Trunk or torso is an anatomical term for the central part of the many animal bodies from which extend the neck and limbs. The trunk includes the thorax and abdomen.-Major organs:...

and forearms, breasts, upper chest

Chest

The chest is a part of the anatomy of humans and various other animals. It is sometimes referred to as the thorax or the bosom.-Chest anatomy - Humans and other hominids:...

, face

Face

The face is a central sense organ complex, for those animals that have one, normally on the ventral surface of the head, and can, depending on the definition in the human case, include the hair, forehead, eyebrow, eyelashes, eyes, nose, ears, cheeks, mouth, lips, philtrum, temple, teeth, skin, and...

; and then finally death. On other occasions, people died from suffocation

Suffocation

Suffocation is the process of Asphyxia.Suffocation may also refer to:* Suffocation , an American death metal band* "Suffocation", a song on Morbid Angel's debut album, Altars of Madness...

with only their calves on fire. Several records report that victims took over 2 hours to die. In many burnings a rope was attached to the convict’s neck

Neck

The neck is the part of the body, on many terrestrial or secondarily aquatic vertebrates, that distinguishes the head from the torso or trunk. The adjective signifying "of the neck" is cervical .-Boner anatomy: The cervical spine:The cervical portion of the human spine comprises seven boney...

passing through a ring on the stake and they were simultaneously strangled and burnt. In later years in England some burnings only took place after the convict had already hanged

Hanging

Hanging is the lethal suspension of a person by a ligature. The Oxford English Dictionary states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion and death by impalement in which the body would remain...

for half an hour. In many areas in England the condemned woman (men were hanged, drawn, and quartered) was seated astride a small seat called the saddle which was fixed half way up a permanently positioned iron stake. The stake was about 4 metres high and had chains hanging from it to hold the condemned woman still during her punishment. Having been taken to the place of execution in a cart with her hands firmly tied in front of her and wearing just a thin shift she was lifted over the executioner’s shoulder and carried up a ladder against the stake to be sat astride the saddle. The chains were then fastened and sometimes she was painted with pitch

Pitch (resin)

Pitch is the name for any of a number of viscoelastic, solid polymers. Pitch can be made from petroleum products or plants. Petroleum-derived pitch is also called bitumen. Pitch produced from plants is also known as resin. Products made from plant resin are also known as rosin.Pitch was...

which was supposed to help the fire burn her more quickly.

Historical usage

Phalaris

Phalaris was the tyrant of Acragas in Sicily, from approximately 570 to 554 BC.-History:He was entrusted with the building of the temple of Zeus Atabyrius in the citadel, and took advantage of his position to make himself despot. Under his rule Agrigentum seems to have attained considerable...

, of Akragas in Sicily, is said to have roasted his enemies alive in a brazen bull

Brazen bull

The brazen bull, bronze bull, or Sicilian bull, was a torture and execution device designed in ancient Greece. Its inventor, metal worker Perillos of Athens, proposed it to Phalaris, the tyrant of Akragas, Sicily, as a new means of executing criminals. The bull was made entirely of bronze, hollow,...

; it was devised for him by a workman named Perillus or Perilaos, who made it so that the screams of the victims sounded like the roaring of a bull; when Perillus asked for his reward, he became the first victim. Phalaris was later executed in his brazen bull.

Burning was used as a means of execution in many ancient societies. According to ancient reports, Roman

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

authorities executed many of the early Christian martyrs by burning, sometimes by means of the tunica molesta

Tunica molesta

A tunica molesta was a shirt impregnated with flammable substances such as naphtha, used to execute people by burning in ancient Rome. The Roman emperor Nero executed some Christians in this way, according to Seneca....

, a flammable tunic.

Also Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion

Haninah ben Teradion

Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion or Hananiah ben Teradion was a teacher in the third Tannaitic generation . He was a contemporary of Eleazar ben Perata I and of Halafta, together with whom he established certain ritualistic rules...

, one of the Jewish Ten Martyrs

Ten Martyrs

The Ten Martyrs refers to a group of ten rabbis living during the era of the Mishnah who were martyred by the Romans in the period after the destruction of the second Temple...

executed for defying Emperor Hadrian

Hadrian

Hadrian , was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138. He is best known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman Britain. In Rome, he re-built the Pantheon and constructed the Temple of Venus and Roma. In addition to being emperor, Hadrian was a humanist and was philhellene in...

’s edicts against practice of the Jewish religion, is reported to have been burnt at the stake. As narrated in the Talmud

Talmud

The Talmud is a central text of mainstream Judaism. It takes the form of a record of rabbinic discussions pertaining to Jewish law, ethics, philosophy, customs and history....

, ben Teradion was placed on a pyre of green brush; fire was set to it, and wet wool was placed on his chest to prolong the agonies of death. However, the executioner – moved by the Rabbi’s proud and stoic stance amidst the fire – removed the wool and fanned the flame, thus accelerating the end, and then he himself plunged into the flames.

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

, the ancient Celts executed thieves and prisoners of war by burning them to death inside giant “wicker men

Wicker Man

A wicker man was a large wicker statue of a human used by the ancient Druids for human sacrifice by burning it in effigy, according to Julius Caesar in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico...

”.

North American Indians often used burning as a form of execution, either against members of other tribes or against white settlers during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Roasting over a slow fire was a customary method. See Captives in American Indian Wars

Captives in American Indian Wars

Treatment applied to captives in the American Indian Wars was specific to the local culture of each tribe. Captive adults might be killed, while children were, most of time, kept alive and adopted...

.

Under the Byzantine Empire

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the Roman Empire or Romania to its inhabitants and neighbours, the Empire was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State...

, burning was introduced as a punishment for disobedient Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is a religion and philosophy based on the teachings of prophet Zoroaster and was formerly among the world's largest religions. It was probably founded some time before the 6th century BCE in Greater Iran.In Zoroastrianism, the Creator Ahura Mazda is all good, and no evil...

s, because of the belief that they worshiped fire.

The Byzantine Emperor Justinian (r. 527–565) ordered death by fire, intestacy

Intestacy

Intestacy is the condition of the estate of a person who dies owning property greater than the sum of their enforceable debts and funeral expenses without having made a valid will or other binding declaration; alternatively where such a will or declaration has been made, but only applies to part of...

, and confiscation of all possessions by the State to be the punishment for heresy against the Christian faith in his Codex Iustiniani

Corpus Juris Civilis

The Corpus Juris Civilis is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Eastern Roman Emperor...

(CJ 1.5.), ratifying the decrees of his predecessors the Emperors Arcadius

Arcadius

Arcadius was the Byzantine Emperor from 395 to his death. He was the eldest son of Theodosius I and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla, and brother of the Western Emperor Honorius...

and Flavius Augustus Honorius.

In 1184, the Roman Catholic Synod of Verona

Synod of Verona

The Synod of Verona was held in 1184 under the auspices of Pope Lucius III. It is most notable for condemning the Waldensians under the charge of witchcraft; the charge was later amended to include heresy....

legislated that burning was to be the official punishment for heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

. It was also believed that the condemned would have no body to be resurrected in the Afterlife. This decree was later reaffirmed by the Fourth Council of the Lateran

Fourth Council of the Lateran

The Fourth Council of the Lateran was convoked by Pope Innocent III with the papal bull of April 19, 1213, and the Council gathered at Rome's Lateran Palace beginning November 11, 1215. Due to the great length of time between the Council's convocation and meeting, many bishops had the opportunity...

in 1215, the Synod

Synod

A synod historically is a council of a church, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. In modern usage, the word often refers to the governing body of a particular church, whether its members are meeting or not...

of Toulouse in 1229, and numerous spiritual and secular leaders through the 17th century.

Civil authorities burnt persons judged to be heretics under the medieval Inquisition, including Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno , born Filippo Bruno, was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, mathematician and astronomer. His cosmological theories went beyond the Copernican model in proposing that the Sun was essentially a star, and moreover, that the universe contained an infinite number of inhabited...

. The historian Hernando del Pulgar

Hernando del Pulgar

Hernando del Pulgar was a Spanish writer.He was born at Pulgar and was educated at the court of John II. Henry IV made him one of his secretaries, and under Isabella he became councillor of state, was charged with a mission to France, and in 1482 was appointed historiographer-royal...

, contemporary of Ferdinand and Isabella, estimated that the Spanish Inquisition

Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition , commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition , was a tribunal established in 1480 by Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. It was intended to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms, and to replace the Medieval...

had burned at the stake 2,000 people by 1490 (just one decade after the Inquisition began). In the terms of the Spanish Inquisition a burning was described as relaxado en persona

Relaxado en persona

Relaxado en persona is a Spanish phrase, literally meaning "relaxed in person", but a euphemism for "burnt at the stake" in the records of the Spanish Inquisition. The majority of those "relaxed in person" from 1484 onwards were relapsos or herejes...

.

Burning was also used by Roman Catholics and Protestants

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

during the witch-hunts of Europe. The penal code known as the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina

Constitutio Criminalis Carolina

The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina is recognised as the first body of German criminal law...

(1532) decreed that sorcery throughout the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

should be treated as a criminal offence, and if it purported to inflict injury upon any person the witch was to be burnt at the stake. In 1572, Augustus, Elector of Saxony

Augustus, Elector of Saxony

Augustus was Elector of Saxony from 1553 to 1586.-First years:Augustus was born in Freiberg, the youngest child and third son of Henry IV, Duke of Saxony, and Catherine of Mecklenburg. He consequently belonged to the Albertine branch of the Wettin family...

imposed the penalty of burning for witchcraft of every kind, including simple fortunetelling.

Among the best-known individuals to be executed by burning were Jacques de Molay

Jacques de Molay

Jacques de Molay was the 23rd and last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, leading the Order from 20 April 1292 until it was dissolved by order of Pope Clement V in 1312...

(1314), Jan Hus

Jan Hus

Jan Hus , often referred to in English as John Hus or John Huss, was a Czech priest, philosopher, reformer, and master at Charles University in Prague...

(1415), St. Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc

Saint Joan of Arc, nicknamed "The Maid of Orléans" , is a national heroine of France and a Roman Catholic saint. A peasant girl born in eastern France who claimed divine guidance, she led the French army to several important victories during the Hundred Years' War, which paved the way for the...

(30 May 1431), Savonarola (1498) Patrick Hamilton

Patrick Hamilton (martyr)

Patrick Hamilton was a Scottish churchman and an early Protestant Reformer in Scotland. He travelled to Europe, where he met several of the leading reforming thinkers, before returning to Scotland to preach...

(1528), John Frith

John Frith

John Frith was an English Protestant priest, writer, and martyr.Frith was an important contributor to the Christian debate on persecution and toleration in favour of the principle of religious toleration...

(1533), William Tyndale

William Tyndale

William Tyndale was an English scholar and translator who became a leading figure in Protestant reformism towards the end of his life. He was influenced by the work of Desiderius Erasmus, who made the Greek New Testament available in Europe, and by Martin Luther...

(1536), Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus was a Spanish theologian, physician, cartographer, and humanist. He was the first European to correctly describe the function of pulmonary circulation...

(1553), Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno , born Filippo Bruno, was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, mathematician and astronomer. His cosmological theories went beyond the Copernican model in proposing that the Sun was essentially a star, and moreover, that the universe contained an infinite number of inhabited...

(1600) and Avvakum

Avvakum

Avvakum Petrov was a Russian protopope of Kazan Cathedral on Red Square who led the opposition to Patriarch Nikon's reforms of the Russian Orthodox Church...

(1682). Anglican martyrs Hugh Latimer

Hugh Latimer

Hugh Latimer was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, Bishop of Worcester before the Reformation, and later Church of England chaplain to King Edward VI. In 1555, under Queen Mary, he was burnt at the stake, becoming one of the three Oxford Martyrs of Anglicanism.-Life:Latimer was born into a...

and Nicholas Ridley

Nicholas Ridley (martyr)

Nicholas Ridley was an English Bishop of London. Ridley was burned at the stake, as one of the Oxford Martyrs, during the Marian Persecutions, for his teachings and his support of Lady Jane Grey...

(both in 1555) and Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build a favourable case for Henry's divorce from Catherine of Aragon which resulted in the separation of the English Church from...

(1556) were also burnt at the stake.

In Denmark the burning of witches increased following the reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

of 1536. Especially Christian IV of Denmark

Christian IV of Denmark

Christian IV was the king of Denmark-Norway from 1588 until his death. With a reign of more than 59 years, he is the longest-reigning monarch of Denmark, and he is frequently remembered as one of the most popular, ambitious and proactive Danish kings, having initiated many reforms and projects...

encouraged this practice, which eventually resulted in hundreds of people burnt because of convictions of witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

. This special interest of the king also resulted in the North Berwick witch trials

North Berwick witch trials

The North Berwick witch trials were the trials in 1590 of a number of people from East Lothian, Scotland, accused of witchcraft in the St Andrew's Auld Kirk in North Berwick. They ran for two years and implicated seventy people. The accused included Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell on charges...

with caused over seventy people to be accused of witchcraft in Scotland on account of bad weather when James I of England

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

, who shared the Danish king’s interest in witch trials, in 1590 sailed to Denmark to meet his betrothed Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark was queen consort of Scotland, England, and Ireland as the wife of King James VI and I.The second daughter of King Frederick II of Denmark, Anne married James in 1589 at the age of fourteen and bore him three children who survived infancy, including the future Charles I...

.

Edward Wightman

Edward Wightman was an English radical Anabaptist, executed at Lichfield for his activities promoting himself as the divine Paraclete and Savior of the world...

, a Baptist from Burton on Trent, was the last person to be burnt at the stake for heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

in England in the market square of Lichfield

Lichfield

Lichfield is a cathedral city, civil parish and district in Staffordshire, England. One of eight civil parishes with city status in England, Lichfield is situated roughly north of Birmingham...

, Staffordshire

Staffordshire

Staffordshire is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes, the county is a NUTS 3 region and is one of four counties or unitary districts that comprise the "Shropshire and Staffordshire" NUTS 2 region. Part of the National Forest lies within its borders...

on 11 April 1612.

In the United Kingdom, the traditional punishment for women found guilty of treason was to be burnt at the stake, where they did not need to be publicly displayed naked, while men were hanged, drawn and quartered

Hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered was from 1351 a penalty in England for men convicted of high treason, although the ritual was first recorded during the reigns of King Henry III and his successor, Edward I...

. There were two types of treason, high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

for crimes against the Sovereign, and petty treason

Petty treason

Petty treason or petit treason was an offence under the common law of England which involved the betrayal of a superior by a subordinate. It differed from the better-known high treason in that high treason can only be committed against the Sovereign...

for the murder of one’s lawful superior, including that of a husband by his wife.

In England, only a few accused of witchcraft were burnt; the majority were hanged. Sir Thomas Malory

Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author or compiler of Le Morte d'Arthur. The antiquary John Leland as well as John Bale believed him to be Welsh, but most modern scholars, beginning with G. L...

, in Le Morte d’Arthur (1485), depicts King Arthur

King Arthur

King Arthur is a legendary British leader of the late 5th and early 6th centuries, who, according to Medieval histories and romances, led the defence of Britain against Saxon invaders in the early 6th century. The details of Arthur's story are mainly composed of folklore and literary invention, and...

as being reluctantly constrained to order the burning of Queen Guinevere

Guinevere

Guinevere was the legendary queen consort of King Arthur. In tales and folklore, she was said to have had a love affair with Arthur's chief knight Sir Lancelot...

, once her adultery with Lancelot

Lancelot

Sir Lancelot du Lac is one of the Knights of the Round Table in the Arthurian legend. He is the most trusted of King Arthur's knights and plays a part in many of Arthur's victories...

was revealed, as a Queen’s adultery would be construed as treason against her royal husband.

Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn ;c.1501/1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536 as the second wife of Henry VIII of England and Marquess of Pembroke in her own right. Henry's marriage to Anne, and her subsequent execution, made her a key figure in the political and religious upheaval that was the...

and Catherine Howard

Catherine Howard

Catherine Howard , also spelled Katherine, Katheryn or Kathryn, was the fifth wife of Henry VIII of England, and sometimes known by his reference to her as his "rose without a thorn"....

, first cousins and the second and fifth wives of Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

were both condemned to be burnt alive or beheaded for adultery as the king’s pleasure should be known. Fortunately for Catherine and Anne, even Henry would not go so far. They were both beheaded. Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey , also known as The Nine Days' Queen, was an English noblewoman who was de facto monarch of England from 10 July until 19 July 1553 and was subsequently executed...

the nine days queen was also condemned to burn as a traitress but it was commuted to beheading by Mary I

Mary I of England

Mary I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from July 1553 until her death.She was the only surviving child born of the ill-fated marriage of Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, succeeded Henry in 1547...

.

In Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

, there are two cases of burning at the stake. First, in 1681, a slave named Maria tried to kill her owner by setting his house on fire. She was convicted of arson and burned at the stake at Roxbury, Massachusetts. Concurrently, a slave named Jack, convicted in a separate arson case, was hanged at a nearby gallows, and after death his body was thrown into the fire with that of Maria. Second, in 1755, a group of slaves had conspired and killed their owner, with servants Mark and Phillis executed for his murder. Mark was hanged and his body gibbet

Gibbet

A gibbet is a gallows-type structure from which the dead bodies of executed criminals were hung on public display to deter other existing or potential criminals. In earlier times, up to the late 17th century, live gibbeting also took place, in which the criminal was placed alive in a metal cage...

ed, and Phillis burned at the stake, at Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

several burnings at the stake are recorded, particularly following suspected slave revolt plots. In 1708 one woman was burnt and one man hanged. In the aftermath of the New York Slave Revolt of 1712 20 people were burnt, and during the alleged slave conspiracy of 1741 no less than 13 slaves were burnt at the stake.

The last burning by the Catholic Church in Latin America was of Mariana de Castro, Lima

Lima

Lima is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín rivers, in the central part of the country, on a desert coast overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Together with the seaport of Callao, it forms a contiguous urban area known as the Lima...

, 1732.

In 1790, Sir Benjamin Hammett introduced a bill into Parliament

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

to end the practice. He explained that the year before, as Sheriff

Sheriff

A sheriff is in principle a legal official with responsibility for a county. In practice, the specific combination of legal, political, and ceremonial duties of a sheriff varies greatly from country to country....

of London, he had been responsible for the burning of Catherine Murphy

Catherine Murphy (counterfeiter)

Catherine Murphy was an English counterfeiter, the last woman to be officially sentenced and executed by the method of burning in England and Great Britain....

, found guilty of counterfeit

Counterfeit

To counterfeit means to illegally imitate something. Counterfeit products are often produced with the intent to take advantage of the superior value of the imitated product...

ing, but that he had allowed her to be hanged first. He pointed out that as the law stood, he himself could have been found guilty of a crime in not carrying out the lawful punishment and, as no woman had been burnt alive in the kingdom for over fifty years, so could all those still alive who had held an official position at all of the previous burnings. The Treason Act 1790

Treason Act 1790

The Treason Act 1790 was an Act of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Great Britain which abolished burning at the stake as the penalty for women convicted of high treason, petty treason and abetting, procuring or counselling petty treason, and replaced it with drawing and hanging.Identical...

was duly passed by Parliament and given royal assent

Royal Assent

The granting of royal assent refers to the method by which any constitutional monarch formally approves and promulgates an act of his or her nation's parliament, thus making it a law...

by King George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

(30 George III. C. 48).

Modern burnings

No modern state conducts executions by burning, other than a mass execution in North Korea. Like all capital punishment, it is forbidden to members of the Council of EuropeCouncil of Europe

The Council of Europe is an international organisation promoting co-operation between all countries of Europe in the areas of legal standards, human rights, democratic development, the rule of law and cultural co-operation...

by the European Convention on Human Rights

European Convention on Human Rights

The Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms is an international treaty to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by the then newly formed Council of Europe, the convention entered into force on 3 September 1953...

. It was never routinely practiced in the United States and in any case the Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

while ruling on Firing Squads in Wilkerson v. Utah

Wilkerson v. Utah

Wilkerson v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 , is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court affirmed the judgment of the Supreme Court of the Territory of Utah in stating that execution by firing squad, as prescribed by the Utah territorial statute, was not cruel and unusual punishment under the...

from 1879 incidentally determined that it was cruel and unusual punishment

Cruel and unusual punishment

Cruel and unusual punishment is a phrase describing criminal punishment which is considered unacceptable due to the suffering or humiliation it inflicts on the condemned person...

.

However, modern-day burnings still occur. In South Africa for example, extrajudicial execution by burning was done via a method called necklacing

Necklacing

Necklacing is the practice of summary execution and torture carried out by forcing a rubber tyre, filled with petrol, around a victim's chest and arms, and setting it on fire...

where rubber tires filled with kerosene (or gasoline) are placed around the neck of a live individual. The fuel is then ignited, the rubber melts, and the victim is burnt to death. In Rio de Janeiro, burning people standing inside a pile of tires is a common form of murder used by drug dealers to punish those who have supposedly collaborated with the police. This form of burning is called microondas, “the microwave”. The movie Tropa de Elite

Tropa de Elite

The Elite Squad is a 2007 Brazilian film directed by José Padilha. The film is a semi-fictional account of the BOPE , the Special Police Operations Battalion of the Rio de Janeiro Military Police. It is the second feature film and first fiction film of Padilha, who had previously directed the...

(Elite squad) has a scene depicting this practice.

GRU

GRU or Glavnoye Razvedyvatel'noye Upravleniye is the foreign military intelligence directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation...

officer writing under the alias Victor Suvorov, at least one Soviet traitor (Oleg Penkovsky

Oleg Penkovsky

Oleg Vladimirovich Penkovsky, codenamed HERO ; April 23, 1919, Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia, Soviet Russia, – May 16, 1963, Soviet Union), was a colonel with Soviet military intelligence in the late 1950s and early 1960s who informed the United Kingdom and the United States about the Soviet Union...

) was burnt alive in a crematorium. During the 1980 New Mexico State Penitentiary riot

New Mexico State Penitentiary Riot

The New Mexico Penitentiary Riot, which took place on February 2 and 3, 1980, in the state's maximum security prison south of Santa Fe, was one of the most violent prison riots in the history of the American correctional system: 33 inmates died and more than 200 inmates were treated for injuries...

, a number of inmates were burnt to death by fellow inmates, who used blow torch

Blow torch

A blowtorch , blow torch , or blowlamp is a tool for applying lower-intensity and more diffuse flame and heat for various applications, than the oxyacetylene torch. Before aerosol cans and pressurized gas cylinders, fuel was pressurized by a syringe or pump...

es.

One of the most notorious extrajudicial burnings of modern times occurred in Waco, Texas

Waco, Texas

Waco is a city in and the county seat of McLennan County, Texas. Situated along the Brazos River and on the I-35 corridor, halfway between Dallas and Austin, it is the economic, cultural, and academic center of the 'Heart of Texas' region....

in the USA on 15 May 1916. Jesse Washington, a mentally challenged African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

farmhand, after having been convicted of the murder of a white woman, was taken by a mob to a bonfire, castrated, doused in coal oil

Coal oil

Coal oil is a term once used for a specific shale oil used for illuminating purposes. Coal oil is obtained from the destructive distillation of cannel coal, mineral wax, and bituminous shale, while kerosene is obtained by the distillation of petroleum...

, and hanged by the neck from a chain over the bonfire, slowly burning to death. A postcard from the event still exists, showing a crowd standing next to Washington’s charred corpse with the words on the back “This is the barbecue we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe”. This event attracted international condemnation, and is remembered as the Waco Horror.

At the end of the 1990s, a number of North Korean army generals were executed by being burnt alive inside the Rungrado May Day Stadium

Rungrado May Day Stadium

The Rŭngrado May First Stadium, or May Day Stadium, is a multi-purpose stadium in Pyongyang, North Korea, completed on May 1, 1989.-Overview:The stadium was constructed as a main stadium for the 13th World Festival of Youth and Students in 1989....

in Pyongyang

Pyongyang

Pyongyang is the capital of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, commonly known as North Korea, and the largest city in the country. Pyongyang is located on the Taedong River and, according to preliminary results from the 2008 population census, has a population of 3,255,388. The city was...

, North Korea

North Korea

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea , , is a country in East Asia, occupying the northern half of the Korean Peninsula. Its capital and largest city is Pyongyang. The Korean Demilitarized Zone serves as the buffer zone between North Korea and South Korea...

.

In Sulaymaniyah

Sulaymaniyah

Sulaymaniyah is a city in Iraqi Kurdistan, Iraq. It is the capital of Sulaymaniyah Governorate. Sulaymaniyah is surrounded by the Azmar Range, Goizja Range and the Qaiwan Range in the north east, Baranan Mountain in the south and the Tasluje Hills in the west. The city has a semi-arid climate with...

, Iraq

Iraq

Iraq ; officially the Republic of Iraq is a country in Western Asia spanning most of the northwestern end of the Zagros mountain range, the eastern part of the Syrian Desert and the northern part of the Arabian Desert....

, there were 400 cases of the burning of women in 2006. In Iraqi Kurdistan

Iraqi Kurdistan

Iraqi Kurdistan or Kurdistan Region is an autonomous region of Iraq. It borders Iran to the east, Turkey to the north, Syria to the west and the rest of Iraq to the south. The regional capital is Arbil, known in Kurdish as Hewlêr...

, at least 255 women had been killed in just the first six months of 2007, three-quarters of them by burning.

It was reported on 21 May 2008, that in Kenya

Kenya

Kenya , officially known as the Republic of Kenya, is a country in East Africa that lies on the equator, with the Indian Ocean to its south-east...

a mob had burnt to death at least 11 people accused of witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

.

On 19 June 2008, the Taliban in Sadda, Lower Kurram, Pakistan burnt alive three truck drivers of the Turi

Turi

The Turi or Torai inhabit the Kurram Valley, in Kurram Agency, Federally Administered Tribal Areas, Pakistan. They speak Pashto and practice the Twelver Shia sect of Islam.-Pre-Imperial history:...

tribe after attacking a convoy of trucks loaded with food and other basic needs & medicine in way from Kohat

Kohat

Kohat is a medium sized town in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. It is located at 33°35'13N 71°26'29E with an altitude of 489 metres and is the capital of Kohat District. The town centres around a British-era fort, various bazaars, and a military cantonment. A British-built narrow gauge...

to Parachinar

Parachinar

Parachinar is the capital of Kurram Agency, FATA of Pakistan. It is about 290 km west of the capital, Islamabad...

in the presence of security forces.

Self-immolation by widows

Although satiSati (practice)

For other uses, see Sati .Satī was a religious funeral practice among some Indian communities in which a recently widowed woman either voluntarily or by use of force and coercion would have immolated herself on her husband’s funeral pyre...

, or the practice of a widow immolating herself on her husband’s funeral pyre, was officially outlawed by India

British Raj

British Raj was the British rule in the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947; The term can also refer to the period of dominion...

’s British rulers in 1829, the rite persists. The most high-profile sati incident was in Rajasthan in 1987 when 18-year-old Roop Kanwar

Roop Kanwar

Roop Kanwar was an 18-year old Rajput woman who committed sati on 4 September 1987 at Deorala village of Sikar district in Rajasthan, India. At the time of her death, she had been married for eight months to Maal Singh Shekhawat, who had died a day earlier at age 24, and had no children.Several...

was burned to death.

Bride-burning

Bride-burning is counted a form of murderMurder

Murder is the unlawful killing, with malice aforethought, of another human being, and generally this state of mind distinguishes murder from other forms of unlawful homicide...

, not execution. On 20 January 2011, 28 year old Ranjeeta Sharma was found burning to death on a road in rural New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

. The New Zealand Police confirmed that the woman was alive before being covered in an accelerant and set alight. Sharma’s husband, Davesh Sharma, has been charged with her murder.

Portrayal in film

Carl Theodor DreyerCarl Theodor Dreyer

Carl Theodor Dreyer, Jr. was a Danish film director. He is regarded by many critics and filmmakers as one of the greatest directors in cinema.-Life:Dreyer was born illegitimate in Copenhagen, Denmark...

’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc

The Passion of Joan of Arc

The Passion of Joan of Arc is a silent film produced in France in 1928. It is based on the record of the trial of Joan of Arc. The film was directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer and stars Renée Jeanne Falconetti...

(The Passion of Joan of Arc), though made in the late 1920s (and therefore without the assistance of computer graphics), includes a relatively graphic and realistic treatment of Jeanne

Joan of Arc

Saint Joan of Arc, nicknamed "The Maid of Orléans" , is a national heroine of France and a Roman Catholic saint. A peasant girl born in eastern France who claimed divine guidance, she led the French army to several important victories during the Hundred Years' War, which paved the way for the...

’s execution; his Day of Wrath

Day of Wrath

Day of Wrath is a black-and-white film, made in 1943, by Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer. The film is an adaptation of Anne Pedersdotter by the Norwegian playwright Hans Wiers-Jenssen, based on an actual Norwegian case in the sixteenth century.-Plot:Day of Wrath is set in a Danish village in...

also featured a woman burnt at the stake. Many other film versions of the story of Joan show her death at the stake — some more graphically than others. The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc

The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc

The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc is a French/American historical drama film directed by Luc Besson. The screenplay was written by Besson and Andrew Birkin, and the original music score was composed by Éric Serra....

, released in 1999, ends with Joan slowly burned alive in the marketplace of Rouen.

Fritz Lang

Fritz Lang

Friedrich Christian Anton "Fritz" Lang was an Austrian-American filmmaker, screenwriter, and occasional film producer and actor. One of the best known émigrés from Germany's school of Expressionism, he was dubbed the "Master of Darkness" by the British Film Institute...

’s Metropolis

Metropolis (film)

Metropolis is a 1927 German expressionist film in the science-fiction genre directed by Fritz Lang. Produced in Germany during a stable period of the Weimar Republic, Metropolis is set in a futuristic urban dystopia and makes use of this context to explore the social crisis between workers and...

(1931) involves a robot

Robot

A robot is a mechanical or virtual intelligent agent that can perform tasks automatically or with guidance, typically by remote control. In practice a robot is usually an electro-mechanical machine that is guided by computer and electronic programming. Robots can be autonomous, semi-autonomous or...

being burnt at the stake. The Seventh Seal

The Seventh Seal

The Seventh Seal is a 1957 Swedish film written and directed by Ingmar Bergman. Set during the Black Death, it tells of the journey of a medieval knight and a game of chess he plays with the personification of Death , who has come to take his life. Bergman developed the film from his own play...

(1957) shows a woman about to be burnt at the stake. In The Wicker Man (1973) a British Police Sergeant, after a series of tests to prove his suitability, is burnt to death by the local population inside a giant wicker cage in the shape of a man to assure the next year’s crops and simultaneously assuring his entering heaven as a martyr. In the film adaptation of Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco Knight Grand Cross is an Italian semiotician, essayist, philosopher, literary critic, and novelist, best known for his novel The Name of the Rose , an intellectual mystery combining semiotics in fiction, biblical analysis, medieval studies and literary theory...

’s The Name of the Rose

The Name of the Rose (film)

The Name of the Rose is a 1986 film directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, based on the book of the same name by Umberto Eco. Sean Connery is the Franciscan friar William of Baskerville and Christian Slater is his apprentice Adso of Melk, who are called upon to solve a deadly mystery in a medieval...

(1986), the innocent simpleton Salvatore (Ron Perlman

Ron Perlman

Ronald N. "Ron" Perlman is an American television, film and voice over actor. He is known for having played Vincent in the TV series Beauty and the Beast , a Deathstroke figure known as Slade in the animated series Teen Titans, Clarence "Clay" Morrow in Sons of Anarchy, the comic book character...

) is seen to die horribly, burnt at the stake. The fate is also suffered by Oliver Reed

Oliver Reed

Oliver Reed was an English actor known for his burly screen presence. Reed exemplified his real-life macho image in "tough guy" roles...

’s less innocent character in Ken Russell

Ken Russell

Henry Kenneth Alfred "Ken" Russell was an English film director, known for his pioneering work in television and film and for his flamboyant and controversial style. He attracted criticism as being obsessed with sexuality and the church...

’s The Devils

The Devils (film)

The Devils is a 1971 British historical drama directed by Ken Russell and starring Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave. It is based partially on the 1952 book The Devils of Loudun by Aldous Huxley, and partially on the 1960 play The Devils by John Whiting, also based on Huxley's book...

(1971). In 1492: Conquest of Paradise

1492: Conquest of Paradise

1492: Conquest of Paradise is an epic 1992 European adventure/drama film directed by Ridley Scott and written by Roselyne Bosch, which tells the story of the discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus and the effect this had on the indigenous people...

(1992), several people are burnt at the stake. The Last of the Mohicans

The Last of the Mohicans (1992 film)

The Last of the Mohicans is a 1992 historical epic film set in 1757 during the French and Indian War and produced by Morgan Creek Pictures. It was directed by Michael Mann and based on James Fenimore Cooper's novel of the same name, although it owes more to George B. Seitz's 1936 film adaptation...

(1992) features a British officer being burnt at the stake by a Huron tribe. In Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996 film)

The Hunchback of Notre Dame is a 1996 American animated drama film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation and released to theaters on June 21, 1996 by Walt Disney Pictures. The thirty-fourth animated feature in the Disney animated features canon, the film is inspired by Victor Hugo's novel of...

(1996), an innocent gypsy woman Esmeralda is almost burnt at the stake, but rescued by Quasimodo. The nineteenth episode in the 3rd season of The X Files contains a scene where a security officer discovers a man being burned alive in a crematory

Crematory

A crematory is a machine in which cremation takes place. Crematories are usually found in funeral homes, cemeteries, or in stand-alone facilities. A facility which houses the actual cremator units is referred to as a crematorium.-History:Prior to the Industrial Revolution, any cremation which took...

. The film Elizabeth

Elizabeth (film)

Elizabeth is a 1998 biographical film written by Michael Hirst, directed by Shekhar Kapur, and starring Cate Blanchett in the title role of Queen Elizabeth I of England, alongside Geoffrey Rush, Christopher Eccleston, Joseph Fiennes, Sir John Gielgud, Fanny Ardant and Richard Attenborough...

(1998) used computer graphics to enhance the opening scene where three Protestants are burnt at the stake.

In the 2005 horror sequel Saw II

Saw II

Saw II is a 2005 Canadian-American horror film directed by Darren Lynn Bousman and co-written by Bousman and the first film's co-writer Leigh Whannell. It is a sequel to 2004's Saw and the second installment in the seven-part Saw film series...

a subject burns alive in a furnace while attempting to retrieve two antidotes to a gas that is slowly killing every person in the game. When he pulls the second syringe down from the ceiling of the furnace, he locks himself in and sets the fire alight at the same time.

In the 2007 film adaption and many of the musicals of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber Of Fleet Street

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street is a 1936 British film produced and directed by George King.-Plot:The film features Tod Slaughter in one of his most famous roles as barber Sweeney Todd. Sweeney Todd was wrongly sentenced to life in prison. After his release 15 years later, he begins...

, Sweeney Todd

Sweeney Todd

Sweeney Todd is a fictional character who first appeared as then antagonist of the Victorian penny dreadful The String of Pearls and he was later introduced as an antihero in the broadway musical Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street and its film adaptation...

throws Mrs. Lovett

Mrs. Lovett

Mrs. Lovett is a fictional character appearing in many adaptations of the story Sweeney Todd. She is most commonly referred to as Nellie, although Margery, Maggie, Sarah, Shirley, Wilhemina and Claudetta are other names she has been given. First appearing in the penny dreadful serial The String of...

into an oven and watches her burn briefly before closing the door, as revenge for leading him to believe that his wife was dead. The horror film The Hills Have Eyes

The Hills Have Eyes (2006 film)

The Hills Have Eyes is a 2006 horror film and remake of Wes Craven's 1977 film The Hills Have Eyes. Written by filmmaking partners Alexandre Aja and Grégory Levasseur of the French horror film Haute Tension, and directed by Aja, the film follows a family who becomes the target of a group of...

(2006) graphically portrays a man being burnt to death while tied to a tree. In the 2006 film Final Destination 3

Final Destination 3

Final Destination 3 is a 2006 supernatural slasher film, and the third film in the Final Destination series. The film was directed and written by James Wong, who co-wrote and directed the first film, and was produced by Craig Perry. It was released in North America on February 10, 2006...

, two teenage girls become trapped in overheating tanning beds and are burnt to death when fires erupt. Silent Hill

Silent Hill (film)

Silent Hill is a 2006 horror film directed by Christophe Gans and written by Roger Avary. The story is an adaptation of the Silent Hill series of survival horror video games created by Konami. The film, particularly its emotional, religious and aesthetic content as well as its creature design,...

(2006) depicts death by burning as a punishment in two separate scenes. The Brazilian film Tropa de Elite

Tropa de Elite

The Elite Squad is a 2007 Brazilian film directed by José Padilha. The film is a semi-fictional account of the BOPE , the Special Police Operations Battalion of the Rio de Janeiro Military Police. It is the second feature film and first fiction film of Padilha, who had previously directed the...

(2007) depicts an execution by burning in Rio de Janeiro. In the film adaptation of Dan Brown

Dan Brown

Dan Brown is an American author of thriller fiction, best known for the 2003 bestselling novel, The Da Vinci Code. Brown's novels, which are treasure hunts set in a 24-hour time period, feature the recurring themes of cryptography, keys, symbols, codes, and conspiracy theories...

’s Angels and Demons

Angels and Demons

Angels & Demons is a 2000 bestselling mystery-thriller novel written by American author Dan Brown and published by Pocket Books. The novel introduces the character Robert Langdon, who is also the protagonist of Brown's subsequent 2003 novel, The Da Vinci Code, and 2009 novel, The Lost Symbol...

(2009), the third of four kidnapped cardinals is burned to death, after previously being branded with the ambigram “fire”; later in the film the main villain commits self-immolation

Self-immolation

Self-immolation refers to setting oneself on fire, often as a form of protest or for the purposes of martyrdom or suicide. It has centuries-long traditions in some cultures, while in modern times it has become a type of radical political protest...

in St Peter’s Basilica. The film Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

(2010) includes scenes of death by fire associated with a knight of the military orders who is assigned to witch hunting.

See also

- Auto-da-féAuto-da-féAn auto-da-fé was the ritual of public penance of condemned heretics and apostates that took place when the Spanish Inquisition or the Portuguese Inquisition had decided their punishment, followed by the execution by the civil authorities of the sentences imposed...

- InquisitionInquisitionThe Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

- List of people burned as heretics

- Sati (practice)Sati (practice)For other uses, see Sati .Satī was a religious funeral practice among some Indian communities in which a recently widowed woman either voluntarily or by use of force and coercion would have immolated herself on her husband’s funeral pyre...

(widow-burning) - Self-immolationSelf-immolationSelf-immolation refers to setting oneself on fire, often as a form of protest or for the purposes of martyrdom or suicide. It has centuries-long traditions in some cultures, while in modern times it has become a type of radical political protest...

- Spanish InquisitionSpanish InquisitionThe Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition , commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition , was a tribunal established in 1480 by Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. It was intended to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms, and to replace the Medieval...

- Spontaneous human combustionSpontaneous human combustionSpontaneous human combustion describes reported cases of the burning of a living human body without an apparent external source of ignition...

- Witch-huntWitch-huntA witch-hunt is a search for witches or evidence of witchcraft, often involving moral panic, mass hysteria and lynching, but in historical instances also legally sanctioned and involving official witchcraft trials...

- WitchcraftWitchcraftWitchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

- Witchcraft ActWitchcraft ActIn England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland a succession of Witchcraft Acts have governed witchcraft and provided penalties for its practice, or for pretending to practise it.- Witchcraft Act 1542:...

- Yaoya OshichiYaoya Oshichi, literally "greengrocer Oshichi", was a daughter of the greengrocer Tarobei. She lived in the Hongō neighborhood of Edo at the beginning of the Edo period. She attempted to commit arson after falling in love with a boy. This story became the subject of joruri plays...