Witch trials in Early Modern Europe

Encyclopedia

Early modern Europe

Early modern Europe is the term used by historians to refer to a period in the history of Europe which spanned the centuries between the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, roughly the late 15th century to the late 18th century...

, and to some extent in the European colonies in North America, there was a widespread hysteria that malevolent Satanic

Satanism

Satanism is a group of religions that is composed of a diverse number of ideological and philosophical beliefs and social phenomena. Their shared feature include symbolic association with, admiration for the character of, and even veneration of Satan or similar rebellious, promethean, and...

witches

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

were operating as an organized threat to Christendom

Christendom

Christendom, or the Christian world, has several meanings. In a cultural sense it refers to the worldwide community of Christians, adherents of Christianity...

. Those accused of witchcraft were portrayed as being worshippers of the Devil

Devil

The Devil is believed in many religions and cultures to be a powerful, supernatural entity that is the personification of evil and the enemy of God and humankind. The nature of the role varies greatly...

, who engaged in such acts as malevolent sorcery

Maleficium (sorcery)

Maleficium is a Latin term meaning "wrongdoing" or "mischief" and is used to describe malevolent, dangerous, or harmful magic, "evildoing" or "malevolent sorcery"...

, and orgies at meetings known as Witches' Sabbaths. Many people were subsequently accused of being witches, and were put on trial for the crime, with varying punishments being applicable in different regions and at different times.

While early trials fall still within the Late Medieval period, the peak of the witch hunt was during the period of the European wars of religion

European wars of religion

The European wars of religion were a series of wars waged in Europe from ca. 1524 to 1648, following the onset of the Protestant Reformation in Western and Northern Europe...

, peaking between about 1580 and 1630.

The witch hunts declined in the early 18th century. In Great Britain, their end is marked by the Witchcraft Act of 1735. But sporadic witch-trials continued to be held during the second half of the 18th century, the last known dating to 1782, though a prosecution was commenced in Tennessee as recently as 1833.

Over the entire duration of the phenomenon of some three centuries, an estimated total of 40,000 to 60,000 people were executed.

Among the best known of these trials were the Scottish North Berwick witch trials

North Berwick witch trials

The North Berwick witch trials were the trials in 1590 of a number of people from East Lothian, Scotland, accused of witchcraft in the St Andrew's Auld Kirk in North Berwick. They ran for two years and implicated seventy people. The accused included Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell on charges...

, Swedish Torsåker witch trials

Torsåker witch trials

The Torsåker witch trials took place in 1675 in Torsåker parish, Sweden. 71 people: 6 men and 65 women were beheaded and then burned, all in a single day...

and the American Salem witch trials

Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings before county court trials to prosecute people accused of witchcraft in the counties of Essex, Suffolk, and Middlesex in colonial Massachusetts, between February 1692 and May 1693...

. Among the largest and most notable were the Trier witch trials

Trier witch trials

The Witch trials of Trier in Germany in the years from 1581 to 1593 was the perhaps biggest witch trial in Europe. The persecutions started in the diocese of Trier in 1581 and reached the city itself in 1587, where it was to lead to the death of about three hundred and sixty eight people, and was...

(1581–1593), the Fulda witch trials

Fulda witch trials

The Witch trials of Fulda in Germany in the years from 1603 to 1606 was one of the biggest witch trials in Europe together with the Trier witch trials 1587-1593 and Quedlinburg in 1589...

(1603–1606), the Würzburg witch trial

Würzburg witch trial

The Würzburg witch trial, which took place in Germany in 1626–1631, is one of the biggest mass-trials and mass-executions seen in Europe during the Thirty Years War; 157 men, women and children in the city of Würzburg are confirmed to have been burned alive at the stake; 219 are believed to...

(1626–1631) and the Bamberg witch trials

Bamberg witch trials

The Bamberg witch trials, which took place in Bamberg in Germany in 1626-1631, are among the more famous cases in European witchcraft history. They resulted in the executions of between 300 and 600 people, and were some of the greatest witch trials in history, as well as some of the greatest...

(1626–1631).

The sociological causes of the witch-hunts have long been debated in scholarship.

Mainstream historiography sees the reason for the witch craze in a complex interplay of various factors that mark the Early Modern period

Early modern period

In history, the early modern period of modern history follows the late Middle Ages. Although the chronological limits of the period are open to debate, the timeframe spans the period after the late portion of the Middle Ages through the beginning of the Age of Revolutions...

, including the religious sectarianism

Sectarianism

Sectarianism, according to one definition, is bigotry, discrimination or hatred arising from attaching importance to perceived differences between subdivisions within a group, such as between different denominations of a religion, class, regional or factions of a political movement.The ideological...

in the wake of the Reformation

Reformation

- Movements :* Protestant Reformation, an attempt by Martin Luther to reform the Roman Catholic Church that resulted in a schism, and grew into a wider movement...

, besides other religious, societal, economic and climatic factors.

Background

Three developments in Christian doctrine have been identified as factors contributing significantly to the witch hunts: 1) a shift from the rejection of belief in witches to an acceptance of their existence and powers, 2) developments in the doctrine of SatanSatan

Satan , "the opposer", is the title of various entities, both human and divine, who challenge the faith of humans in the Hebrew Bible...

which incorporated witchcraft as part of Satanic influence, 3) the identification of witchcraft as heresy. Belief in witches and supernatural evil were widespread in medieval Europe, and the secular legal codes of European countries had identified witchcraft as a crime before being reached by Christian missionaries. Scholars have noted that the early influence of the Church in the mediaeval era resulted in the revocation of these laws in many places, bringing an end to traditional pagan witch hunts.

Throughout the medieval era mainstream Christian teaching denied the existence of witches and witchcraft, condemning it as pagan superstition. Notable instances include an Irish synod in 800, Agobard of Lyons

Agobard

Agobard of Lyon was a Spanish-born priest and archbishop of Lyon, during the Carolingian Renaissance. The author of multiple treatises, ranging in subject matter from the iconoclast controversy to Spanish Adoptionism to critiques of the Carolingian royal family, Agobard is best known for his...

, Pope Gregory VII

Pope Gregory VII

Pope St. Gregory VII , born Hildebrand of Sovana , was Pope from April 22, 1073, until his death. One of the great reforming popes, he is perhaps best known for the part he played in the Investiture Controversy, his dispute with Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor affirming the primacy of the papal...

, and Serapion of Vladimire. The traditional accusations and punishments were likewise condemned. Historian Ronald Hutton

Ronald Hutton

Ronald Hutton is an English historian who specializes in the study of Early Modern Britain, British folklore, pre-Christian religion and contemporary Paganism. A reader in the subject at the University of Bristol, Hutton has published fourteen books and has appeared on British television and radio...

therefore exonerated the early Church from responsibility for the witch hunts, arguing that this was the result of doctrinal change in the later Church.

However, Christian influence on popular beliefs in witches and maleficium (harm committed by magic), failed to eradicate traditional beliefs, and developments in the Church doctrine of Satan proved influential in reversing the previous dismissal of witches and witchcraft as superstition; instead these beliefs were incorporated into an increasingly comprehensive theology of Satan as the ultimate source of all maleficium. The work of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

in the 13th century was instrumental in developing the new theology which would give rise to the witch hunts, but due to the fact that sorcery was judged by secular courts it was not until maleficium was identified with heresy that theological trials for witchcraft could commence. Despite these changes the doctrinal shift was only completed in the 15th century, when it first began to result in Church-inspired witch trials. Promulgation of the new doctrine by Henricus Institoris met initial resistance in some areas, and some areas of Europe only experienced the first wave of the new witch trials in the latter half of the 16th century.

Magic and witchcraft

During the Mediaeval period, there was widespread belief in magicMagic (paranormal)

Magic is the claimed art of manipulating aspects of reality either by supernatural means or through knowledge of occult laws unknown to science. It is in contrast to science, in that science does not accept anything not subject to either direct or indirect observation, and subject to logical...

across Christian Europe, and as the psychologist Gustav Jahoda noted, "the new world as people saw it [in the medieval] included witches, devils, fairies and all kinds of strange beasts ... magic and miracles were commonplace." The Mediaeval Roman Catholic Church, which then dominated a large swath of the continent, divided magic into two forms: natural magic, which was acceptable because it was viewed as merely taking note of the powers in nature that were created by God

God

God is the English name given to a singular being in theistic and deistic religions who is either the sole deity in monotheism, or a single deity in polytheism....

, and demonic magic, which was frowned upon and associated with demonology

Demonology

Demonology is the systematic study of demons or beliefs about demons. It is the branch of theology relating to superhuman beings who are not gods. It deals both with benevolent beings that have no circle of worshippers or so limited a circle as to be below the rank of gods, and with malevolent...

, divination

Divination

Divination is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic standardized process or ritual...

and necromancy

Necromancy

Necromancy is a claimed form of magic that involves communication with the deceased, either by summoning their spirit in the form of an apparition or raising them bodily, for the purpose of divination, imparting the ability to foretell future events or discover hidden knowledge...

. This idea of malevolent magic, or maleficarum, was mentioned by historian Robert W. Thurston

Robert W. Thurston

Robert W. Thurston is an American historian, who is Professor of Historty at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Thurston is known for primarily working in the field of Sovietology, the historical study of the Soviet Union, although has also written on the subject of the Witch trials in the Early...

, who stated that "One of the most persistent features of European world views ... was the presence of humans who used magic to help or hurt their neighbours."

During the Late Mediaeval and Early Modern periods, magical practice was roughly divided into two forms. The first of these, folk magic, was the form of popular practice widely found amongst common people, consisting largely of simple charms and spells. There were various professionals who performed folk magic in a professional capacity, including charmers, astrologers, fortune tellers, and most importantly, cunning folk

Cunning folk

The cunning folk in Britain were professional or semi-professional practitioners of magic active from the Medieval period through to the early twentieth century. As cunning folk, they practised folk magic – also known as "low magic" – although often combined with elements of "high" or ceremonial...

. These were believed to "possess a broader and deeper knowledge of such [magical] techniques and more experience in using them" than the average person, and it was also believed that they "embodied or could work with supernatural

Supernatural

The supernatural or is that which is not subject to the laws of nature, or more figuratively, that which is said to exist above and beyond nature...

power which greatly increased the effectiveness of the operations concerned." One of the primary purposes of the cunning folk was in removing curses and other bewitchments that their clients believed that they had suffered, and in this manner cunning folk were in most cases working actively against witchcraft, using such methods as the witch bottle

Witch Bottle

The witch bottle is a very old spell device. Its purpose is to draw in and trap harmful intentions directed at its owner. Folk magic contends that the witch bottle protects against evil spirits and magical attack, and counteracts spells cast by witches....

in order to do so.

The other form of magic was ceremonial magic

Ceremonial magic

Ceremonial magic, also referred to as high magic and as learned magic, is a broad term used in the context of Hermeticism or Western esotericism to encompass a wide variety of long, elaborate, and complex rituals of magic. It is named as such because the works included are characterized by...

, followed by those who adhered to philosophies like Hermeticism

Hermeticism

Hermeticism or the Western Hermetic Tradition is a set of philosophical and religious beliefs based primarily upon the pseudepigraphical writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus...

and the Qabalah

Hermetic Qabalah

Hermetic Qabalah is a Western esoteric and mystical tradition...

. Whilst the Church disapproved of demonic magic, which was practiced by both certain cunning folk and ceremonial magicians, and condemned it in Early Medieval texts, they did little to actively suppress those that they believed practiced it, not believing them to be any significant threat to Christendom.

Various historians, notably Carlo Ginzburg

Carlo Ginzburg

Carlo Ginzburg is a noted historian and proponent of the field of microhistory. He is best known for his Il formaggio e I vermi which examined the beliefs of an Italian heretic, Menocchio, from Montereale Valcellina.- Biography :The son of Natalia Ginzburg and Leone Ginzburg, he was born...

, Éva Pócs

Éva Pócs

Éva Pócs is associate professor in the Department of Ethnography and Cultural Anthropology at Janus Pannonius University, Pécs, Hungary, and president of the Folklore Section of the Hungarian Ethnographic Society. She is an author of several books dealing with supernatural beliefs and patterns of...

, Gabor Klaniczay and Emma Wilby

Emma Wilby

Emma Wilby is a British historian specialising in the magical beliefs of Early Modern Britain. An honorary fellow in History at the University of Exeter, England, she has published two books examining witchcraft and the cunning folk of this period...

have theorised that many elements of Early Modern witchcraft were based upon, or even a continuation of, pre-Christian religious beliefs about visionary journeys that had connections with both shamanism

Shamanism

Shamanism is an anthropological term referencing a range of beliefs and practices regarding communication with the spiritual world. To quote Eliade: "A first definition of this complex phenomenon, and perhaps the least hazardous, will be: shamanism = technique of ecstasy." Shamanism encompasses the...

and animism

Animism

Animism refers to the belief that non-human entities are spiritual beings, or at least embody some kind of life-principle....

. In Early Modern Europe, there was often a belief that witches (and in many cases also cunning folk

Cunning folk

The cunning folk in Britain were professional or semi-professional practitioners of magic active from the Medieval period through to the early twentieth century. As cunning folk, they practised folk magic – also known as "low magic" – although often combined with elements of "high" or ceremonial...

) were aided in their performance of magic by supernatural entities known as familiar spirit

Familiar spirit

In European folklore and folk-belief of the Medieval and Early Modern periods, familiar spirits were supernatural entities believed to assist witches and cunning folk in their practice of magic...

s, who appeared in many different forms, usually taking the appearance of either humans or animals. As historian Ronald Hutton remarked, "It is quite possible that pre-Christian mythology lies behind this tradition", an idea supported by other historians, such as Wilby.

In the Early Modern period, it was also widely believed by the prosecutors that the witches travelled to a nocturnal meeting known as the Witches' Sabbath where they worshipped the Devil, feasted, and committed various Christian sins. Although some historians believe that this was entirely a fictional idea created by the witch hunters, others, having studied the first hand reports given by self-professed or accused witches, have come to the conclusion that these trips to the Sabbath were genuine visionary journeys that some witches believed that they went on. Emma Wilby compares these to similar claims made in the Early Modern period by certain cunning folk that they travelled on a visionary journey into Fairy

Fairy

A fairy is a type of mythical being or legendary creature, a form of spirit, often described as metaphysical, supernatural or preternatural.Fairies resemble various beings of other mythologies, though even folklore that uses the term...

land, where they found an assembly led by the King and Queen of the Fairies, feasted, and danced. After making various comparisons with ethnographic

Ethnography

Ethnography is a qualitative method aimed to learn and understand cultural phenomena which reflect the knowledge and system of meanings guiding the life of a cultural group...

and anthropological

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

examples of shamanism in Siberia and North America, she came to the conclusion that both the witches' Sabbath and the Fairyland journeys were visionary experiences undergone by various magical practitioners that likely had their origins in earlier, pre-Christian shamanic ideas.

Some historians have traced the idea of a visionary nocturnal journey from the Early Modern period into earlier periods of European history that were closer to the pre-Christian era. The fact that such nocturnal journeys containing supernatural entities have been found across Mediaeval and Early Modern Europe, from the Benandanti

Benandanti

The Benandanti were an agrarian fertility cult in the Friuli district of Northern Italy in the 16th and 17th centuries. Between 1575 and 1675, the Benandanti were tried as heretics or witches under the Roman Inquisition, and their beliefs assimilated to Satanism...

of sixteenth century Friuli

Friuli

Friuli is an area of northeastern Italy with its own particular cultural and historical identity. It comprises the major part of the autonomous region Friuli-Venezia Giulia, i.e. the province of Udine, Pordenone, Gorizia, excluding Trieste...

in Italy to the supposed werewolves of Early Modern Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

has led historian Carlo Ginzburg

Carlo Ginzburg

Carlo Ginzburg is a noted historian and proponent of the field of microhistory. He is best known for his Il formaggio e I vermi which examined the beliefs of an Italian heretic, Menocchio, from Montereale Valcellina.- Biography :The son of Natalia Ginzburg and Leone Ginzburg, he was born...

to believe that they were a part of an "ancient stratum of beliefs" in Europe, that had been found in pre-Christian paganism

Paganism

Paganism is a blanket term, typically used to refer to non-Abrahamic, indigenous polytheistic religious traditions....

. Indeed, historian Robert Thurston noted that in the tenth century document, the Canon Episcopi

Canon Episcopi

The Canon Episcopi is an important document in the history of witchcraft. It is first attested in the Libri de synodalibus causis et disciplinis ecclesiasticis composed by Regino of Prüm around 906, but Regino considered it an older text; he, and later scholars following him, believed it to be from...

, the author (likely a Christian monk) described that there were women who, due to a trick of the Devil, had visions that made them think that they met other women at nocturnal meetings to ride in processions led by the goddess Diana

Diana (mythology)

In Roman mythology, Diana was the goddess of the hunt and moon and birthing, being associated with wild animals and woodland, and having the power to talk to and control animals. She was equated with the Greek goddess Artemis, though she had an independent origin in Italy...

across "great spaces of the earth". Thurston notes that it was these descriptions of women's nocturnal travels which were "clearly the cultural forerunner of the witches' sabbath." According to these historians therefore, the idea of the witches' sabbath, along with the similar idea of familiar spirits and the cunning folk's journey to Fairyland, were not developments of the witch hunters but were genuine visionary traditions amongst the European populace, ones with their origins in pre-Christian religion.

Satan

It was also during the Medieval period that the concept of SatanSatan

Satan , "the opposer", is the title of various entities, both human and divine, who challenge the faith of humans in the Hebrew Bible...

, the Biblical Devil

Devil

The Devil is believed in many religions and cultures to be a powerful, supernatural entity that is the personification of evil and the enemy of God and humankind. The nature of the role varies greatly...

, began to develop into a more threatening form. Around the year 1000, when there were increasing fears that the end of the world would soon come in Christendom, the idea of the Devil had become prominent, with many believing that his activities on Earth would soon begin appearing. Whilst in earlier centuries there had been no set depiction of the Devil, it was also around this time that he began to develop the stereotypical image of being animal-like, or even in some cases an animal himself. In particular, he was often viewed as a goat, or as a human with goat-like features, such as horns, hooves and a tail. Equally, the concepts of demons began to become more prominent, in particular the idea that male demons known as incubi, and female ones known as succubi, would roam the Earth and have sexual intercourse with humans. As Thurston noted, "By about 1200, it would have been difficult to be a Christian and not frequently hear of the devil ... [and] by 1500 scenes of the devil were commonplace in the new cathedrals and small parish churches that had sprung up in many regions."

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the concept of the witch in Christendom underwent a relatively radical change. No longer were they viewed as sorcerers who had been deceived by the Devil into practicing magic that went against the powers of God, as earlier Church leaders like Saint Augustine of Hippo had stated. Instead they became the all-out malevolent Devil-worshipper, who had made a pact with him in which they had to renounce Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

and devote themselves to Satanism. As a part of this, they gained, new, supernatural powers that enabled them to work magic

Magic (paranormal)

Magic is the claimed art of manipulating aspects of reality either by supernatural means or through knowledge of occult laws unknown to science. It is in contrast to science, in that science does not accept anything not subject to either direct or indirect observation, and subject to logical...

, which they would use against Christians. It was believed that they would fly to their nocturnal meetings, known as the Witches' Sabbath, where they would have sexual intercourse with demons. On their death, the witches’ souls, which then belonged to the Devil, subsequently went to Hell

Hell

In many religious traditions, a hell is a place of suffering and punishment in the afterlife. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hells as endless. Religions with a cyclic history often depict a hell as an intermediary period between incarnations...

.

Medieval persecution of heresy

Whilst the witch trials only really began in the 15th century, with the start of the Early Modern periodEarly modern period

In history, the early modern period of modern history follows the late Middle Ages. Although the chronological limits of the period are open to debate, the timeframe spans the period after the late portion of the Middle Ages through the beginning of the Age of Revolutions...

, many of their causes had been developing during the previous centuries, with the persecution of heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

by the Medieval Inquisition

Medieval Inquisition

The Medieval Inquisition is a series of Inquisitions from around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition and later the Papal Inquisition...

during the late twelfth and the thirteenth centuries, and during the Late Medieval period, during which the idea of witchcraft or sorcery gradually changed and adapted. The inquisition had the office of protecting Christian orthodoxy against the "internal" threat of heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

(as opposed to "external" military threats such as those of the Vikings, the Mongols

Mongol invasions

Mongol invasions progressed throughout the 13th century, resulting in the vast Mongol Empire which covered much of Asia and Eastern Europe by 1300....

, and the Saracens or Turks

Growth of the Ottoman Empire

The Growth of the Ottoman Empire is the period followed after the Rise of the Ottoman Empire in which the Ottoman state reached the Pax Ottomana. In this period, the Ottoman Empire expanded southwestwards into North Africa and battled with the re-emergent Persian Shi'ia Safavid Empire to the east...

).

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages was the period of European history around the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries . The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which by convention end around 1500....

, a number of heretical Christian groups, such as the Cathars and the Knights Templar

Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon , commonly known as the Knights Templar, the Order of the Temple or simply as Templars, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders...

had been accused of performing such anti-Christian activities as Satanism, sodomy

Sodomy

Sodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

and malevolent sorcery in France. While the nucleus of the Early Modern "witch craze" would turn out to be popular superstition in the Western Alps, reinforced by theological rationale developed at or following the Council of Basel of the 1430s, what has been called "the first real witch trial in Europe", the accusation of Alice Kyteler

Alice Kyteler

Dame Alice Kyteler , was a woman who was the earliest person accused and condemned for witchcraft in Ireland. She fled the country, but her servant Petronella de Meath was flogged and burned at the stake on November 3, 1324....

in 1324, occurred in 14th-century Ireland, during the turmoils associated with the decline of Norman control.

Thurston (2001) speaks of a shift in Christian society from a "relatively open and tolerant" attitude to that of a "persecuting society" taking an aggressive stance towards minorities characterized as Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

, heretics (such as Cathars and Waldensians

Waldensians

Waldensians, Waldenses or Vaudois are names for a Christian movement of the later Middle Ages, descendants of which still exist in various regions, primarily in North-Western Italy. There is considerable uncertainty about the earlier history of the Waldenses because of a lack of extant source...

), lepers or homosexuals, often associated with conspiracy theories assuming a concerted effort on the part of diabolical forces to weaken and destroy Christianity, indeed "the idea became popular that one or more vast conspiracies were trying to destroy Christianity from within. The plotters were reputedly financed and abetted by an outside, evil force, often the Muslims." An important turning-point was the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

of 1348–1350, which killed a large percentage of the European population, and which many Christians believed had been caused by their enemies. The catalogue of typical charges that would later be levelled at witches, of spreading diseases, committing orgies (sometimes incest

Incest

Incest is sexual intercourse between close relatives that is usually illegal in the jurisdiction where it takes place and/or is conventionally considered a taboo. The term may apply to sexual activities between: individuals of close "blood relationship"; members of the same household; step...

uous), cannibalising children

Blood libel

Blood libel is a false accusation or claim that religious minorities, usually Jews, murder children to use their blood in certain aspects of their religious rituals and holidays...

, and following Satanism

Satanism

Satanism is a group of religions that is composed of a diverse number of ideological and philosophical beliefs and social phenomena. Their shared feature include symbolic association with, admiration for the character of, and even veneration of Satan or similar rebellious, promethean, and...

, emerged during the fourteenth century as crimes attributed to heretics and Jews.

Witchcraft had not been considered a heresy during the High Medieval period. Indeed, since the Council of Paderborn

Council of Paderborn

The Council of Paderborn of 785, debating the matter of the Christianization of the Saxons, resolved to make punishable by law all sorts of idolatry, as well as the belief in the existence of witchcraft. It ordered the death penalty for self-appointed witch-hunters who had caused the death of...

of 785, the belief in the possibility of witchcraft itself was considered heretical. While witch-hunts only became common after 1400, an important legal step that would make this development possible occurred in 1320, when Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII , born Jacques Duèze , was pope from 1316 to 1334. He was the second Pope of the Avignon Papacy , elected by a conclave in Lyon assembled by Philip V of France...

authorized the inquisition

Medieval Inquisition

The Medieval Inquisition is a series of Inquisitions from around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition and later the Papal Inquisition...

to persecute witchcraft as a type of heresy.

By the late fourteenth century, a number of "witch hunters" began to publish books on the topic, including Nicholas Eymeric, the inquisitor in Aragon

Aragon

Aragon is a modern autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. Located in northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces : Huesca, Zaragoza, and Teruel. Its capital is Zaragoza...

and Avignon

Avignon

Avignon is a French commune in southeastern France in the départment of the Vaucluse bordered by the left bank of the Rhône river. Of the 94,787 inhabitants of the city on 1 January 2010, 12 000 live in the ancient town centre surrounded by its medieval ramparts.Often referred to as the...

, who published the Directorium Inquisitorum

Directorium Inquisitorum

The Directorium Inquisitorum is Nicholas Eymerich's most prominent and enduring work, which he had composed as early as 1376. Eymerich had written an earlier treatise on sorcery, perhaps as early as 1359, which he extensively reworked into the Directorium Inqusitorum The Directorium Inquisitorum...

in 1376.

Beginning of the witch hunts during the 15th century

Valais witch trials

The Valais witch trials consisted of a witch-hunt including a series of witch trials which took place in the Duchy of Savoy in today's southeastern France and Switzerland between 1428 and 1447. It can be considered as the first series of witch trials in Europe, fifty years before the starting point...

, in communities of the Western Alps, in what was at the time Burgundy

Duchy of Burgundy

The Duchy of Burgundy , was heir to an ancient and prestigious reputation and a large division of the lands of the Second Kingdom of Burgundy and in its own right was one of the geographically larger ducal territories in the emergence of Early Modern Europe from Medieval Europe.Even in that...

and Savoy

Duchy of Savoy

From 1416 to 1847, the House of Savoy ruled the eponymous Duchy of Savoy . The Duchy was a state in the northern part of the Italian Peninsula, with some territories that are now in France. It was a continuation of the County of Savoy...

.

Here, the cause of eliminating the supposed Satanic witches from society was taken up by a number of individuals; Claude Tholosan for instance had tried over two hundred people accusing them of witchcraft in Briançon

Briançon

Briançon a commune in the Hautes-Alpes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department....

, Dauphiné

Dauphiné

The Dauphiné or Dauphiné Viennois is a former province in southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of :Isère, :Drôme, and :Hautes-Alpes....

by 1420.

Soon, the idea of identifying and prosecuting witches spread throughout the neighbouring areas of northern Italy, Switzerland and southern Germany, and it was at Basel

Basel

Basel or Basle In the national languages of Switzerland the city is also known as Bâle , Basilea and Basilea is Switzerland's third most populous city with about 166,000 inhabitants. Located where the Swiss, French and German borders meet, Basel also has suburbs in France and Germany...

that the Council of Basel assembled from 1431 to 1437. This Church Council, which had been attended by such anti-witchcraft figures as Johann Nider and Martin Le Franc

Martin le Franc

Martin le Franc was a French poet of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance.He was born in Normandy, and studied in Paris. He entered clerical orders, becoming an apostolic prothonotary, and later becoming secretary to both Antipope Felix V and Pope Nicholas V.He was named provost at Lausanne...

, helped to standardise the stereotype of the Satanic witch that would be propagated throughout the rest of the trials.

Following the meeting of the Council and the increase in the trials around this area of central Europe, the idea that malevolent Satanic witches were operating against Christendom began spreading throughout much of the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

and several adjacent areas. According to historian Robert Thurston, "From this heart of persecution the witch stereotype spread, both through a flood of new writings on the subject and through men who had been at the Council of Basel and now went elsewhere to take up new assignments in the church." The most notable of these works was published in 1486, written by the German Dominican

Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

monk, Heinrich Kramer

Heinrich Kramer

Heinrich Kramer also known under the Latinized name Henricus Institoris, was a German churchman and inquisitor....

—allegedly aided by Jacob Sprenger—known as the Malleus Malificarum (The Hammer of the Witches) in which they set down the stereotypical image of the Satanic witch and prescribed torture as a means of interrogating suspects. The Malleus Malificarum was reprinted in twenty-nine editions up till 1669.

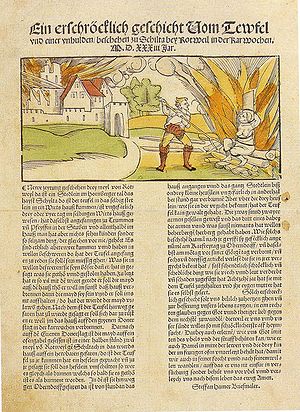

On December 5, 1484, Pope Innocent VIII issued the Summis desiderantes affectibus, a papal bull

Papal bull

A Papal bull is a particular type of letters patent or charter issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the bulla that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it....

in which he recognized the existence of witches and gave full papal approval for the inquisition

Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

to move against witches, including the permission to do whatever necessary to get rid of them. In the bull, which is sometimes referred to as the "Witch-Bull of 1484", the witches were explicitly accused of having "slain infants yet in the mother's womb" (abortion) and of "hindering men from performing the sexual act and women from conceiving" (contraception).

Peak of the trials: 1580–1630

The height of the European trials were between 1580 and 1630, with the large hunts first beginning in 1609. During this period, the biggest witch trials were held in Europe, notably the Trier witch trialsTrier witch trials

The Witch trials of Trier in Germany in the years from 1581 to 1593 was the perhaps biggest witch trial in Europe. The persecutions started in the diocese of Trier in 1581 and reached the city itself in 1587, where it was to lead to the death of about three hundred and sixty eight people, and was...

(1581–1593), the Fulda witch trials

Fulda witch trials

The Witch trials of Fulda in Germany in the years from 1603 to 1606 was one of the biggest witch trials in Europe together with the Trier witch trials 1587-1593 and Quedlinburg in 1589...

(1603–1606), the Würzburg witch trial

Würzburg witch trial

The Würzburg witch trial, which took place in Germany in 1626–1631, is one of the biggest mass-trials and mass-executions seen in Europe during the Thirty Years War; 157 men, women and children in the city of Würzburg are confirmed to have been burned alive at the stake; 219 are believed to...

(1626–1631) and the Bamberg witch trials

Bamberg witch trials

The Bamberg witch trials, which took place in Bamberg in Germany in 1626-1631, are among the more famous cases in European witchcraft history. They resulted in the executions of between 300 and 600 people, and were some of the greatest witch trials in history, as well as some of the greatest...

(1626–1631).

In 1590, the North Berwick witch trials

North Berwick witch trials

The North Berwick witch trials were the trials in 1590 of a number of people from East Lothian, Scotland, accused of witchcraft in the St Andrew's Auld Kirk in North Berwick. They ran for two years and implicated seventy people. The accused included Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell on charges...

occurred in Scotland, and were of particular note as the king, James VI

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

, got involved himself. James had developed a fear that witches planned to kill him after he suffered from storms whilst travelling to Denmark

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

in order to claim his bride, Anne

Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark was queen consort of Scotland, England, and Ireland as the wife of King James VI and I.The second daughter of King Frederick II of Denmark, Anne married James in 1589 at the age of fourteen and bore him three children who survived infancy, including the future Charles I...

, earlier that year. Returning to Scotland, the king heard of trials that were occurring in North Berwick

North Berwick

The Royal Burgh of North Berwick is a seaside town in East Lothian, Scotland. It is situated on the south shore of the Firth of Forth, approximately 25 miles east of Edinburgh. North Berwick became a fashionable holiday resort in the 19th century because of its two sandy bays, the East Bay and the...

and ordered the suspects to be brought to him—he subsequently believed that a nobleman, Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell

Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell

Francis Stewart, Earl Bothwell , was Commendator of Kelso Abbey and Coldingham Priory, a Privy Counsellor and Lord High Admiral of Scotland. Like his stepfather, Archibald Douglas, Parson of Douglas, he was a notorious conspirator, who died in disgrace...

, was a witch, and after the latter fled in fear of his life, he was outlawed as a traitor. The king subsequently set up royal commissions to hunt down witches in his realm, recommending torture in dealing with suspects, and in 1597 he wrote a book about the menace that witches posed to society entitled Daemonologie

Daemonologie

Daemonologie is the book written and published in 1597 by King James VI of Scotland . In the book he approves and supports the practise of witch hunting...

.

Decline of the trials: 1650–1750

Whilst the witch trials had begun to fade out across much of Europe by the mid-seventeenth century, they continued to a greater extent on the fringes of Europe and in the American colonies. In ScandinaviaScandinavia

Scandinavia is a cultural, historical and ethno-linguistic region in northern Europe that includes the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, characterized by their common ethno-cultural heritage and language. Modern Norway and Sweden proper are situated on the Scandinavian Peninsula,...

, the late seventeenth century saw the peak of the trials in a number of areas; for instance, in 1675, the Torsåker witch trials

Torsåker witch trials

The Torsåker witch trials took place in 1675 in Torsåker parish, Sweden. 71 people: 6 men and 65 women were beheaded and then burned, all in a single day...

took place in Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

, where seventy-one people were executed for witchcraft in a single day. In the nearby Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

, which was then under the control of the Swedish monarchy, the hunt peaked in that same decade. During the same period, the Salzburg witch trials

Salzburg witch trials

The Salzburg witch trials, known in history as the Magician Jackls process, which took place in the city of Salzburg in Austria in 1675-1690, was one of the largest and most famous witch trials in Austria. It led to the execution of 139 people...

in Austria led to the death of 139 people (1675–1690).

The clergy and the intellectuals began to speak out against the trials from the late sixteenth century. Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler was a German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer. A key figure in the 17th century scientific revolution, he is best known for his eponymous laws of planetary motion, codified by later astronomers, based on his works Astronomia nova, Harmonices Mundi, and Epitome of Copernican...

in 1615 could only by the weight of his prestige keep his mother from being burnt as a witch. The 1692 Salem witch trials

Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings before county court trials to prosecute people accused of witchcraft in the counties of Essex, Suffolk, and Middlesex in colonial Massachusetts, between February 1692 and May 1693...

were a brief outburst of witch hysteria in the New World at a time when the practice was already waning in Europe. Winifred King was the last person tried for witchcraft in New England.

During the early 18th century, the practice subsided. Jane Wenham

Jane Wenham

Jane Wenham was the subject of what is commonly but erroneously regarded as the last witch trial in England. The trial took place in 1712 and was reported widely in printed tracts of the period, notably F...

was among the last subjects of a typical witch trial in England in 1712, but was pardoned after her conviction and set free. The last execution for witchcraft in England took place in 1716, when Mary Hicks and her daughter Elizabeth were hanged. Janet Horne

Janet Horne

Janet Horne was a Scottish alleged witch, the last person to be executed for witchcraft in Great Britain.Janet Horne and her daughter were arrested in Dornoch in Scotland and imprisoned on the accusations of her neighbours. Horne was showing signs of senility, and her daughter had a deformity of...

was executed for witchcraft in Scotland in 1727. The Witchcraft Act of 1735 saw the end of the traditional form of witchcraft as a legal offence in Britain, those accused under the new act were restricted to people who falsely pretended to be able to procure spirits, generally being the most dubious professional fortune tellers and mediums, and punishment was light.

Helena Curtens

Helena Curtens

Helena Curtens was an alleged German witch. She was one of the last people executed for sorcery in Germany and the last person executed for this crime in the Rhine area...

and Agnes Olmanns were the last women to be executed as witches in Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, in 1738. In Austria, Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa of Austria

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina was the only female ruler of the Habsburg dominions and the last of the House of Habsburg. She was the sovereign of Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, Mantua, Milan, Lodomeria and Galicia, the Austrian Netherlands and Parma...

outlawed witch-burning and torture in the late 18th century; the last capital trial took place in Salzburg in 1750

Maria Pauer

Maria Pauer , was an alleged Austrian witch. She was the last person to be executed for witchcraft in Austria....

.

Sporadic witch-hunts after 1750

In the later eighteenth century, witchcraft had ceased to be considered a criminal offense throughout Europe, but there are a number of cases which were not technically witch trials which are suspected to have involved belief in witches at least behind the scenes. Thus, in 1782, Anna GöldiAnna Göldi

Anna Göldi Anna Göldi Anna Göldi (also Anna Göldin, October 24, 1734 – June 13, 1782 is known as the "last witch" in Switzerland. She was executed for murder in June 1782 in Glarus....

was executed in Glarus

Glarus

Glarus is the capital of the Canton of Glarus in Switzerland. Glarus municipality since 1 January 2011 incorporates the former municipalities of Ennenda, Netstal and Riedern....

, Switzerland

Old Swiss Confederacy

The Old Swiss Confederacy was the precursor of modern-day Switzerland....

, officially for the killing of her infant, a ruling at the time widely denounced throughout Switzerland and Germany as judicial murder

Judicial murder

Judicial murder is the unjustified execution of death penalty.The term was first used in 1782 by August Ludwig von Schlözer in reference to the execution of Anna Göldi...

. Like Anna Göldi, Barbara Zdunk

Barbara Zdunk

Barbara Zdunk, , was an ethnically Polish alleged arsonist and witch who lived in the city of Reszel, now in Poland but between 1772 and 1945 part of Prussia. She is considered by many to have been the last woman executed for witchcraft in Europe. This is doubtful because witchcraft was not a...

was executed in 1811 in Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

not technically for witchcraft but for arson.

In Poland, the Doruchów witch trial occurred in 1783 and the execution of additionally two women for sorcery in 1793, trialed by a legal court but with dubious legitimacy.

Despite the official ending of the trials for Satanic witchcraft, there would still be occasional unofficial killings of those accused in parts of Europe, such as was seen in the cases of Anna Klemens

Anna Klemens

Anna Klemens was a Danish murder victim and an alleged witch. She was lynched and accused of sorcery in Brigsted at Horsens in Denmark, a lynching considered to be the last witch lynching in her country and, most likely, in all Scandinavia....

in Denmark (1800), Krystyna Ceynowa

Krystyna Ceynowa

Krystyna Ceynowa also spelled as Cejnowa, , was a Polish victim of murder by lynching and an alleged witch. She was subjected to the ordeal of water and drowned in Chałupy accused of sorcery...

in Poland (1836), and Dummy, the Witch of Sible Hedingham

Dummy, the Witch of Sible Hedingham

Dummy, the Witch of Sible Hedingham was the pseudonym of an unidentified elderly man who was one of the last people to be charged with witchcraft in England in the 19th century....

in England (1863). In France, there was sporadic violence and even murder in the 1830s, with one woman reportedly burnt in a village square in Nord.

In the 1830s a prosecution for witchcraft was commenced against a man in Fentress County, Tennessee, based upon his alleged influence over the health of a young woman. The case against the supposed witch was dismissed upon the failure of the alleged victim, who had sworn out a warrant against him, to appear for the trial. However, some of his other accusers were convicted on criminal charges for their part in the matter, and various libel actions were brought.

The persecution of those believed to perform malevolent sorcery against their neighbours continued right into the twentieth century. For instance, in 1997 two Russian farmers killed a woman and injured five other members of her family after believing that they had used folk magic against them.

Persecution and sometimes killing of supposed witches still occurs in Sub-saharan Africa, India, and Papua New Guinea. Saudi Arabia and Cameroon are the only countries that still have legislation outlawing witchcraft, with Saudi Arabia having the death penalty for it.

Trials

Animal trial

In legal history, an animal trial was the criminal trial of a non-human. Such trials are recorded as having taken place in Europe from the thirteenth century until the eighteenth...

. People suspected of being "possessed by Satan

Demonic possession

Demonic possession is held by many belief systems to be the control of an individual by a malevolent supernatural being. Descriptions of demonic possessions often include erased memories or personalities, convulsions, “fits” and fainting as if one were dying...

" were put on trial. On the other hand, the church also attempted to extirpate the superstitious belief in witchcraft and sorcery, considering it as fraud in most cases.

Regional differences

The evidence required to convict an alleged witch varied from country to country—but prosecutions everywhere were most frequently sparked off by denunciations, while convictions invariably required a confession. The latter was often obtained by extremely violent methods. Although Europe's witch-frenzy did not begin until the late 15th century—long after the formal abolition of "trial by ordealTrial by ordeal

Trial by ordeal is a judicial practice by which the guilt or innocence of the accused is determined by subjecting them to an unpleasant, usually dangerous experience...

" in 1215—brutal techniques were routinely used to extract the required admission of guilt. They included hot pincers, the thumbscrew, and the "swimming" of suspects (an old superstition whereby innocence was established by immersing the accused in water for a sufficiently long period of time). Investigators were consequently able to establish many fantastic crimes that could never have occurred, even in theory. That said, many judicial procedures of the time required proof of a causative link between the alleged act of witchcraft and an identifiable injury, such as a death or property damage.

The flexibility of the crime and the methods of proving it resulted in easy convictions. Any reckoning of the death toll should take account of the facts that rules of evidence varied from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and that a significant number of witch trials always ended in acquittal.

In York, England, at the height of the Great Hunt (1567–1640) one half of all witchcraft cases brought before church courts were dismissed for lack of evidence. No torture was used, and the accused could clear himself by providing four to eight "compurgators", people who were willing to swear that he wasn't a witch. Only 21% of the cases ended with convictions, and the Church did not impose any kind of corporal or capital punishment.

In the Pays de Vaud, nine of every ten people tried were put to death, but in Finland, the corresponding figure was about one in six (16%). A breakdown of conviction rates (along with statistics on death tolls, gender bias, and much else) can be found in Brian Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe (2nd ed, 1995).

There are particularly important differences between the English and continental witch-hunting traditions. The checks and balances inherent in the jury system, which required a 23-strong body (the grand jury) to indict and a 12-strong one (the petit jury) to convict, always had a restraining effect on prosecutions. Another restraining influence was its relatively rare use of torture: the country formally permitted it only when authorised by the monarch, and no more than 81 torture warrants were issued (for all offences) throughout English history. Continental European courts, while varying from region to region, tended to concentrate power in individual judges and place far more reliance on torture. The significance of the institutional difference is most clearly established by a comparison of the witch-hunts of England and Scotland, for the death toll inflicted by the courts north of the border always dwarfed that of England. It is also apparent from an episode of English history during the early 1640s, when the Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

resulted in the suspension of jury courts for three years. Several freelance witch-hunters emerged during this period, the most notorious of whom was Matthew Hopkins

Matthew Hopkins

Matthew Hopkins was an English witchhunter whose career flourished during the time of the English Civil War. He claimed to hold the office of Witchfinder General, although that title was never bestowed by Parliament...

, who emerged out of East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

and proclaimed himself "Witchfinder General". Such men were inquisitors in all but name, proceeding pursuant to denunciations and torture and claiming a mastery of the supposed science of demonology that allowed for identification of the guilty by, for example, the discovery of witches' marks.

Interrogation and "proofs"

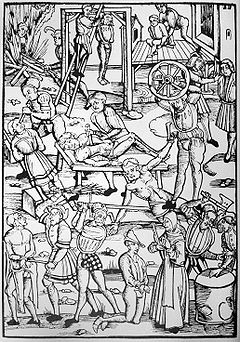

Torture

Torture is the act of inflicting severe pain as a means of punishment, revenge, forcing information or a confession, or simply as an act of cruelty. Throughout history, torture has often been used as a method of political re-education, interrogation, punishment, and coercion...

were used against accused witches to coerce confessions and perhaps cause them to name their co-conspirators. The torture of witches began to grow after 1468 when the Pope declared witchcraft to be "crimen exeptum" and thereby removed all legal limits on the application of torture in cases where evidence was difficult to find. With the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum

Malleus Maleficarum

The Malleus Maleficarum is an infamous treatise on witches, written in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer, an Inquisitor of the Catholic Church, and was first published in Germany in 1487...

in 1487 the accusations and torture of witches again began to increase, leading to the deaths of thousands.

In Italy, an accused witch was deprived of sleep for periods of up to forty hours. This technique was also used in England, but without a limitation on time. Sexual humiliation torture was used, such as forced sitting on red-hot stools with the claim that the accused woman would not perform sexual acts with the devil.

Besides torture, at trial certain "proof

Evidence (law)

The law of evidence encompasses the rules and legal principles that govern the proof of facts in a legal proceeding. These rules determine what evidence can be considered by the trier of fact in reaching its decision and, sometimes, the weight that may be given to that evidence...

s" were taken as valid to establish that a person practiced witchcraft. Peter Binsfeld

Peter Binsfeld

Peter Binsfeld was a German bishop and theologian....

contributed to the establishment of many of these proofs, described in his book Commentarius de Maleficius (Comments on Witchcraft).

- The diabolical mark. Usually, this was a moleMole (skin marking)A melanocytic nevus is a type of lesion that contains nevus cells .Some sources equate the term mole with "melanocytic nevus". Other sources reserve the term "mole" for other purposes....

or a birthmarkBirthmarkA birthmark is a benign irregularity on the skin which is present at birth or appears shortly after birth, usually in the first month. They can occur anywhere on the skin. Birthmarks are caused by overgrowth of blood vessels, melanocytes, smooth muscle, fat, fibroblasts, or...

. If no such mark was visible, the examiner would claim to have found an invisible mark. - Diabolical pact. This was an alleged pact with SatanSatanSatan , "the opposer", is the title of various entities, both human and divine, who challenge the faith of humans in the Hebrew Bible...

to perform evil acts in return for rewards. - Denouncement by another witch. This was common, since the accused could often avoid execution by naming accomplices.

- Relationship with other convicted witch/witches

- Blasphemy

- Participation in SabbathsSabbath (witchcraft)The Witches' Sabbath or Sabbat is a supposed meeting of those who practice witchcraft, and other rites.European records indicate cases of persons being accused or tried for taking part in Sabbat gatherings, from the Middle Ages to the 17th century or later.- Etymology :The English word “sabbat”...

- To cause harm that could only be done by means of sorceryMagic (paranormal)Magic is the claimed art of manipulating aspects of reality either by supernatural means or through knowledge of occult laws unknown to science. It is in contrast to science, in that science does not accept anything not subject to either direct or indirect observation, and subject to logical...

- Possession of elements necessary for the practice of black magicBlack magicBlack magic is the type of magic that draws on assumed malevolent powers or is used with the intention to kill, steal, injure, cause misfortune or destruction, or for personal gain without regard to harmful consequences. As a term, "black magic" is normally used by those that do not approve of its...

- To have one or more witches in the family

- To be afraid during the interrogatories

- Not to cry under torment (supposedly by means of the Devil's aid)

- To have had sexual relationships with a demon

Legal treatises on witchcraft that were widely referred to in continental European trials include the popular Malleus Maleficarum

Malleus Maleficarum

The Malleus Maleficarum is an infamous treatise on witches, written in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer, an Inquisitor of the Catholic Church, and was first published in Germany in 1487...

(1487) by Heinrich Kramer

Heinrich Kramer

Heinrich Kramer also known under the Latinized name Henricus Institoris, was a German churchman and inquisitor....

and Jacob Sprenger, the Tractatus de sortilegiis (1536) by Paolo Grillandi

Paolo Grillandi

Paolo Grillandi was an Italian jurist, from Abruzzo, active as a papal judge in witch trials, from 1517. He was an influential observer of confessions. His book Tractatus de hereticis et sortilegiis , based substantially on his judicial experience, became a standard text on witchcraft and demonology...

and the Praxis rerum criminalium (1554) by Joos de Damhouder

Joos de Damhouder

Joos de Damhouder , also referred to as Joost, Jost, Josse or Jodocus Damhouder, was a jurist from the Seventeen Provinces, whose works had a lasting influence on European criminal law....

.

Executions

The sentence generally was death (as Exodus 22:18 states, "Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live"). There were other sentences, the most common to be chained for years to the oars of a ship, or excommunicatedExcommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

then imprisoned.

Nearly always, a witch's execution involved burning of their body. In England, witches were usually hanged before having their bodies burned and their ashes scattered. In Scotland, the witches were usually strangled at the stake before having their bodies burned—though there are several instances where they were burned alive

Burned at the Stake

Burned at the Stake is a 1981 film directed by Bert I. Gordon. It stars Susan Swift and Albert Salmi.-Cast:*Susan Swift as Loreen Graham / Ann Putnam*Albert Salmi as Captaiin Billingham*Guy Stockwell as Dr. Grossinger*Tisha Sterling as Karen Graham...

. In France, witches were nearly always burned alive. In America people convicted of witchcraft were hanged (in a handful of exceptional cases, such as that of Giles Corey

Giles Corey

Giles Corey was a prosperous farmer and full member of the church in early colonial America who died under judicial torture during the Salem witch trials. Corey refused to enter a plea, and was crushed to death by stone weights in an attempt to force him to do so...

at Salem, alleged witches who refused to plead were pressed to death without trial).

The frequent use of "swimming" to test innocence or guilt means that an unknown number also drowned prior to conviction.

In A History of Torture, George Ryley Scott says:

The peculiar beliefs and superstitions attached to or associated with witchcraft caused those who were suspected of practising the craft to be extremely likely to be subjected to tortures of greater degree than any ordinary heretic or criminal. More, certain specific torments were invented for use against them.

It has been suggested that the execution of persons associated with witchcraft resulted in the loss of much traditional knowledge and folklore, which was often regarded with suspicion and tainted by association.

Numbers of executions

Ever since the ending of the witch hunt, various scholars have estimated how many men, women and children were executed for witchcraft across Europe and North America, with numbers varying wildly depending on the method used to generate the estimate. In the nineteenth century, historians were still unsure as to the exact number, for instance the German folklorist Jacob GrimmJacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Carl Grimm was a German philologist, jurist and mythologist. He is best known as the discoverer of Grimm's Law, the author of the monumental Deutsches Wörterbuch, the author of Deutsche Mythologie and, more popularly, as one of the Brothers Grimm, as the editor of Grimm's Fairy...

claimed that the number was simply "countless" whilst the Scottish journalist Charles Mackay

Charles Mackay

Charles Mackay was a Scottish poet, journalist, and song writer.-Life:Charles Mackay was born in Perth, Scotland. His father was by turns a naval officer and a foot soldier; his mother died shortly after his birth. Charles was educated at the Caledonian Asylum, London, and at Brussels, but spent...

believed that it was "thousands upon thousands". Within several decades, the American suffragette Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Electa Joslyn Gage was a suffragist, a Native American activist, an abolitionist, a freethinker, and a prolific author, who was "born with a hatred of oppression".-Early activities:...

had claimed that nine million women had been killed in the European trials, a figure which would be repeated by a number of later writers such as Gerald Gardner

Gerald Gardner

Gerald Brousseau Gardner , who sometimes used the craft name Scire, was an influential English Wiccan, as well as an amateur anthropologist and archaeologist, writer, weaponry expert and occultist. He was instrumental in bringing the Neopagan religion of Wicca to public attention in Britain and...

, although it has since been described as having "no rational basis whatsoever" by the professional historian Ronald Hutton

Ronald Hutton

Ronald Hutton is an English historian who specializes in the study of Early Modern Britain, British folklore, pre-Christian religion and contemporary Paganism. A reader in the subject at the University of Bristol, Hutton has published fourteen books and has appeared on British television and radio...

.

In the latter part of the 20th century, as historians began to study the witch trials in greater depth, the estimated number of executions began to be reduced, with the historian Norman Cohn

Norman Cohn

Norman Rufus Colin Cohn FBA was a British academic, historian and writer who spent fourteen years as a professorial fellow and as Astor-Wolfson Professor at the University of Sussex.-Life:...

, in Europe's Inner Demons (1975) criticising claims that they were in the hundreds of thousands, calling these "fantastic exaggerations". Attempting to come to an accurate figure, the historian Brian Levack, author of The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe (1987), took the number of known European witch trials and multiplied it by the average rate of conviction and execution. This provided him with a figure of around 60,000 deaths, however, for the third edition of the work (2006) he later reassessed that number to 45,000. This number was criticised as being too low by Anne Llewellyn Barstow, author of Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts (1994)—a work which was derided as un-scholarly and "largely ignored by academics"—who herself arrived at a number of approximately 100,000 deaths by attempting to adjust Levack's estimate to account for what she believed were unaccounted lost records, although historians have pointed out that Levack's estimate had already been adjusted for these.

Ronald Hutton, in his unpublished essay "Counting the Witch Hunt", counted local estimates, and in areas where estimates were unavailable attempted to extrapolate from nearby regions with similar demographics and attitudes towards witch hunting. He reached an estimate of 40,000 total executions. Table of recorded and estimated executions according to Hutton's estimates

| Country | Recorded | Estimated |

|---|---|---|

| American Colonies | 36 | 35–37 |

| Austria | ?? | 1,500–3,000 |

| Belgium | ?? | 250 |

| Bohemia | ?? | 1,000–2,000 |

| Channel Islands | 66 | 66–80 |

| Denmark | ?? | 1,000 |

| England (and Wales) | 228 | 300–1,000 |

| Estonia | 65 | 100 |

| Finland | 115 | 115 |

| France | 775 | 5,000–6,000 |

| Germany | 8,188 | 17,324–26,000 |

| Hungary | 449 | 800 |

| Iceland | 22 | 22 |

| Ireland | 4 | 4–10 |

| Italy | 95 | 800 |

| Latvia | ?? | 100 |

| Luxembourg | 358 | 355–358 |

| Netherlands | 203 | 203–238 |

| Norway | 280 | 350 |

| Poland | ??? | 1,000–5,000 |

| Portugal | 7 | 7 |

| Russia | 10 | 10 |

| Scotland | 599 | 1,100–2,000 |

| Spain | 6 | 40–50 |

| Sweden | ?? | 200–250 |

| Switzerland | 1,039 | 4,000–5,000 |

| Grand Total: | 12,545 | 35,184–63,850 |

Protests

There have been contemporary protesters against witch trials and against use of torture in the examination of those suspected or accused of witchcraft.Middle Ages

Before the 15th century, the position of the church was that belief in witchcraft was a vestige of pagan folk belief and there are numerous medieval sources which deny the existence of witches and penalize popular belief in them.- 643: The Edictum RothariEdictum RothariThe Edictum Rothari was the first written compilation of Lombard law, codified and promulgated 22 November 643 by King Rothari. The custom of the Lombards, according to Paul the Deacon, the Lombard historian, had been held in memory before this...

, the law code for LombardyLombardyLombardy is one of the 20 regions of Italy. The capital is Milan. One-sixth of Italy's population lives in Lombardy and about one fifth of Italy's GDP is produced in this region, making it the most populous and richest region in the country and one of the richest in the whole of Europe...

in ItalyItalyItaly , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

("Let nobody presume to kill a foreign serving maid or female slave as a witch, for it is not possible, nor ought to be believed by Christian minds"). - 672–754: St. Boniface of Mainz consistently denied the existence of witches, saying that to believe in them was unchristian.

- 775–790: The First Synod of Saint Patrick declared that those who believed in witches are to be anathematized.

- 785: Canon 6 of the Christian Council of PaderbornCouncil of PaderbornThe Council of Paderborn of 785, debating the matter of the Christianization of the Saxons, resolved to make punishable by law all sorts of idolatry, as well as the belief in the existence of witchcraft. It ordered the death penalty for self-appointed witch-hunters who had caused the death of...

in Germany outlawed the belief in witches and ordered the death penalty for those who had organized unofficial witch trials resulting in death. - 9th century: French abbot Agobard of Lyon denied that any person could obtain or wield the power to fly, change shape, or cause bad weather, and argued that such claims were imagination and myth.

- 10th century: The Canon EpiscopiCanon EpiscopiThe Canon Episcopi is an important document in the history of witchcraft. It is first attested in the Libri de synodalibus causis et disciplinis ecclesiasticis composed by Regino of Prüm around 906, but Regino considered it an older text; he, and later scholars following him, believed it to be from...

denied the existence of witches, and considered the belief in witches to be heresy (it did not require any punishment of witches) - 906: In his work A Warning to Bishops, Abbot Regino of PrümRegino of PrümReginon or Regino of Prüm was a Benedictine abbot and medieval chronicler.-Biography:According to the statements of a later era, Regino was the son of noble parents and was born at the stronghold of Altrip on the Rhine near Speyer at an unknown date...

dismisses the popular beliefs in witches and witchcraft as complete fiction. - 936: Pope Leo VII wrote to Archbishop Gerhard of Lorch requiring him to instruct local authorities not to execute those accused of witchcraft.

- 11th century: ColomanColomanColoman, , , ; )* Coloman I. the Book-lover* Coloman of Galicia-Lodomeria * Saint Coloman of Stockerau * Colomán Trabado Pérez...

, the Christian king of Hungary, passed a law declaring "Concerning witches, no such things exist, therefore no more investigations are to be held" (De strigis vero quae non sunt, nulla amplius quaestio fiat). - 1020: Burchard of WormsBurchard of WormsBurchard of Worms was the Roman Catholic bishop of Worms in the Holy Roman Empire, and author of a Canon law collection in twenty books, the "Collectarium canonum" or "Decretum".-Life:...

argued that witches had no power to fly, change people's dispositions, control the weather, or transform themselves or anyone else, and denied the existence of incubi and succubi. He ruled that a belief in such things was a sin, and required priests to impose a strict penance on those who confessed to believing them. - 1080: Gregory VIIPope Gregory VIIPope St. Gregory VII , born Hildebrand of Sovana , was Pope from April 22, 1073, until his death. One of the great reforming popes, he is perhaps best known for the part he played in the Investiture Controversy, his dispute with Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor affirming the primacy of the papal...