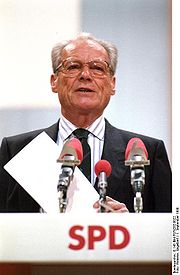

Willy Brandt

Encyclopedia

Willy Brandt, born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm (ˈvɪli ˈbʁant; 18 December 1913 – 8 October 1992), was a German

politician, Mayor of West Berlin 1957–1966, Chancellor of West Germany

1969–1974, and leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

(SPD) 1964–1987.

Brandt's most important legacy was Ostpolitik

, a policy aimed at improving relations with East Germany, Poland

, and the Soviet Union

. This policy caused considerable controversy in West Germany, but won Brandt the Nobel Peace Prize

in 1971.

In 1974, Brandt resigned as Chancellor after Günter Guillaume

, one of his closest aides, was exposed as an agent of the Stasi

, the East German secret service

.

) to Martha Frahm, an unwed mother who worked as a cashier for a department store. His father was an accountant from Hamburg named John Möller, whom Brandt never met. As his mother worked six days a week, he was mainly brought up by his mother's stepfather Ludwig Frahm and his second wife Dora.

After passing his Abitur

in 1932 at Johanneum zu Lübeck, he became an apprentice at the shipbroker and ship's agent F.H. Bertling. He joined the "Socialist Youth" in 1929 and the Social Democratic Party

(SPD) in 1930. He left the SPD to join the more left wing Socialist Workers Party (SAP), which was allied to the POUM

in Spain and the Independent Labour Party

in Britain. In 1933, using his connections with the port and its ships, he left Germany for Norway

to escape Nazi

persecution. It was at this time that he adopted the pseudonym

Willy Brandt to avoid detection by Nazi agents. In 1934, he took part in the founding of the International Bureau of Revolutionary Youth Organizations

, and was elected to its Secretariat.

Brandt was in Germany from September to December 1936, disguised as a Norwegian student named Gunnar Gaasland. He was married to Gertrud Meyer from Lübeck

in a fictitious marriage to protect her from deportation. Meyer had joined Brandt in Norway in July 1933. In 1937, during the Civil War

, Brandt worked in Spain

as a journalist. In 1938, the German government revoked his citizenship, so he applied for Norwegian citizenship

. In 1940, he was arrested in Norway by occupying German forces, but was not identified as he wore a Norwegian uniform. On his release, he escaped to neutral Sweden

. In August 1940, he became a Norwegian citizen, receiving his passport from the Norwegian embassy in Stockholm

, where he lived until the end of the war. Willy Brandt lectured in Sweden on 1 December 1940 at Bommersvik

college about problems experienced by the social democrats in Nazi Germany and the occupied countries at the start of World War II

. In exile in Norway and Sweden Brandt learned Norwegian

and Swedish

. Brandt spoke Norwegian fluently, and retained a close relationship with Norway.

In late 1946, Brandt returned to Berlin

, working for the Norwegian government. In 1948, he joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany

(SPD) and became a German citizen again, formally adopting the pseudonym, Willy Brandt, as his legal name.

From 3 October 1957, to 1966, Willy Brandt was Mayor of West Berlin, during a period of increasing tension in East-West relations that led to the construction of the Berlin Wall

From 3 October 1957, to 1966, Willy Brandt was Mayor of West Berlin, during a period of increasing tension in East-West relations that led to the construction of the Berlin Wall

. In Brandt's first year as Mayor, he also served as the President of the Bundesrat

in Bonn

. Brandt was outspoken against the Soviet

repression of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution

and against Nikita Khrushchev

's 1958 proposal that Berlin receive the status of a "free city

". He was supported by the influential publisher Axel Springer

. As Mayor of West Berlin, Brandt accomplished much in the way of urban development. New hotels, office-blocks and flats were constructed, while both Schloss Charlottenburg and the Reichstag

were restored. Sections of the "Stadtring" Bundesautobahn 100

inner-city motorway were opened, while a major housing programme was carried out, with roughly 20,000 new dwellings built each year during his time in office.

At the start of 1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy saw Brandt as the wave of the future in West Germany and was hoping he would replace Konrad Adenauer as chancellor following elections later in the year. Kennedy made this preference clear by inviting Brandt, the West German opposition leader, to an official meeting at the White House a month before meeting with Adenauer, the country’s leader. The diplomatic snub strained relations between Kennedy and Adenauer further during an especially tense time for Berlin. However, following the building of the Berlin Wall in August 1961, Brandt was disappointed and angry with Kennedy. Speaking in Berlin three days later, Brandt criticized Kennedy, asserting "Berlin expects more than words. It expects political action." He also wrote Kennedy a highly critical public letter in which he warned that the development was liable "to arouse doubts about the ability of the three [Allied] Powers to react and their determination" and he called the situation "a state of accomplished extortion"."

Brandt became the Chairman of the SPD in 1964, a post that he retained until 1987, longer than any other party Chairman since its foundation by August Bebel

. Brandt was the SPD candidate for the Chancellorship in 1961, but he lost to Konrad Adenauer

's conservative Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU). In 1965, Brandt ran again, but lost to the popular Ludwig Erhard

. Erhard's government was short-lived, however, and in 1966 a grand coalition

between the SPD and CDU was formed, with Brandt as Foreign Minister and Vice-Chancellor.

government with the smaller Free Democratic Party of Germany (FDP). Brandt was elected Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany.

(New Eastern Policy). Brandt was active in creating a degree of rapprochement with East Germany, and also in improving relations with the Soviet Union

, Poland

, Czechoslovakia

, and other Eastern Bloc

(communist) countries. A seminal moment came in December 1970 with the famous Warschauer Kniefall

in which Brandt, apparently spontaneously, knelt down at the monument to victims of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

. The uprising occurred during the Nazi German military occupation of Poland, and the monument is to those killed by the German troops who suppressed the uprising and deported remaining ghetto residents to the concentration camps for extermination.

Time

magazine in the U.S.A. named Brandt as its Man of the Year for 1970, stating, "Willy Brandt is in effect seeking to end World War II by bringing about a fresh relationship between East and West. He is trying to accept the real situation in Europe, which has lasted for 25 years, but he is also trying to bring about a new reality in his bold approach to the Soviet Union and the East Bloc."

In 1971, Brandt received the Nobel Peace Prize

for his work in improving relations with East Germany, Poland

, and the Soviet Union

.

Brandt negotiated a peace treaty between the Federal Republic of Germany and Poland, and agreements on the boundaries between the two countries, signifying the official and long-delayed end of World War II

. Brandt negotiated parallel treaties and agreements between the Federal Republic and Czechoslovakia.

In West Germany, Brandt's Neue Ostpolitik was extremely controversial, dividing the populace into two camps: one camp, embracing all of the conservative parties and most notably the victims i.e. those German-speaking, West German residents and their subsequent families who were driven west ("die Heimatvertriebenen") by Stalinist ethnic cleansing

from Historical Eastern Germany

, especially the part that was arbitrarily given to Poland by the Stalinists; western Czechoslovakia

(the Sudetenland

); and the rest of Eastern Europe, such as in Romania

. These groups of displaced Germans and their descendants loudly voiced their opposition to Brandt's policy, calling it "illegal" and "high treason".

A different camp supported and encouraged Brandt's Neue Ostpolitik as aiming at "Wandel durch Annäherung" ("change through rapprochement

"), encouraging change through a policy of engagement with the (communist) Eastern Bloc, rather than trying to isolate those countries diplomatically and commercially. Brandt's supporters claim that the policy did help to break down the Eastern Bloc's "siege mentality

", and also helped to increase its awareness of the contradictions in its brand of Socialism/Communism, which – together with other events – eventually led to the downfall of Eastern European Communism and Stalinism.

and a general "change of the times" that not all Germans were willing to accept or approve. What had seemed a stable, peaceful nation, happy with its outcome of the "Wirtschaftswunder" ("economic miracle") faced economic turbulence. The German baby-boom generation wanted to come to terms with the deeply conservative, bourgeois, and demanding parent generation. The baby-boomer students were the most outspoken, and they accused their "parental generation" of being outdated and old-fashioned and even of having a Nazi past. Compared to their forebears, the "skeptical generation" was much more capricious, willing to embrace more extreme socialist ideology (such as Maoism), and public heroes (such as Ho Chi Minh

, Fidel Castro

, and Che Guevara

), while living a looser and more promiscuous lifestyle. Students and young apprentices could afford to move out of their parents' homes, and left-wing politics was considered to be chic

, as well as taking part in American-style political demonstrations against having American military forces in South Vietnam

.

, had been a member of the Nazi party, and was a more old-fashioned conservative-liberal intellectual. Brandt, having fought the Nazis and having faced down communist Eastern Germany during several crises while he was the Mayor of Berlin, became a controversial, but credible, figure in several different factions. As the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Kiesinger's grand coalition

cabinet, Brandt helped to gain further international approval for Western Germany, and he laid the foundation stones for his future Neue Ostpolitik. There was a wide public-opinion gap between Kiesinger and Brandt in the West German polls.

Both men had come to their own terms with the new baby boomer lifestyles. Kiesinger considered them to be "a shameful crowd of long-haired drop-outs who needed a bath and someone to discipline them". On the other hand, Brandt needed a while to get into contact with, and to earn credibility among, the "Ausserparlamentarische Opposition

Both men had come to their own terms with the new baby boomer lifestyles. Kiesinger considered them to be "a shameful crowd of long-haired drop-outs who needed a bath and someone to discipline them". On the other hand, Brandt needed a while to get into contact with, and to earn credibility among, the "Ausserparlamentarische Opposition

" (APO) ("the extra-parliamentary opposition"). The students questioned West German society in general, seeking social, legal, and political reforms. Also, the unrest led to a renaissance of right-wing parties in some of the Bundeslands' (German states under the Bundesrepublik) Parliaments.

Brandt, however, represented a figure of change, and he followed a course of social, legal, and political reforms. In 1969, Brandt gained a small majority by forming a coalition with the FDP. In his first speech before the Bundestag as the Chancellor, Brandt set forth his political course of reforms ending the speech with his famous words, "Wir wollen mehr Demokratie wagen" (literally: "We want to take a chance on more Democracy", or more figuratively, "Let's dare more democracy"). This speech made Brandt, as well as the Social Democratic Party, popular among most of the students and other young West German baby-boomers who dreamed of a country that would be more open and more colorful than the frugal and still somewhat-authoritarian Bundesrepublik that had been built after World War II. However, Brandt's Neue Ostpolitik lost for him a large part of the German refugee (from the East) voters who had been significantly pro-SPD in the postwar years.

, “Brandt was anxious that his government should be a reforming administration and a number of reforms were embarked upon”. Within a few years, the education budget rose from 16 billion to 50 billion DM, while one out of every three DM spent by the new government was devoted to welfare purposes. As noted by the journalist and historian Marion Dönhoff

,

“People were seized by a completely new feeling about life. A mania for large scale reforms spraed like wildfire, affecting schools, universities, the administration, family legislation. In the autumn of 1970 Jurgen Wischnewski of the SPD declared, ‘Every week more than three plans for reform come up for decision in cabinet and in the Assembly.’ ”

According to Helmut Schmidt

, Willy Brandt's domestic reform programme had accomplished more than any previous programme for a comparable period. A number of liberal social reforms were instituted whilst the welfare state was significantly expanded (with total public spending on social programs nearly doubling between 1969 and 1975), with health, housing, and social welfare legislation bringing about welcome improvements, and by the end of the Brandt Chancellorship West Germany had one of the most advanced systems of welfare in the world.

Amongst his achievements as Chancellor were:

, Heinz Starke, and Siegfried Zoglmann crossed the floor to join the CDU. On 23 February 1972, SPD deputy Herbert Hupka

, who was also leader of the Bund der Vertriebenen

, joined the CDU in disagreement with Brandt's reconciliatory efforts towards the east. On 23 April 1972, Wilhelm Helms (FDP) left the coalition ; the FDP politicians Knud von Kühlmann-Stumm and Gerhard Kienbaum also declared that they would vote against Brandt; thus, Brandt had lost his majority. On 24 April 1972 a vote of no confidence was proposed and it was voted on three days later. Had this motion passed, Rainer Barzel

would have replaced Brandt as Chancellor. To everyone's surprise, the motion failed: Barzel got only 247 votes out of 260 ballots; for an absolute majority, 249 votes would have been necessary. There were also 10 votes against the motion and 3 invalid ballots. Most deputies of SPD and FDP did not take part in the voting, as not voting had the same effect as voting pro Brandt. It was not revealed until much later that two Bundestag members (Julius Steiner and Leo Wagner, both of the CDU/CSU) had been bribed by the East German Stasi

to vote for Brandt.

, Walter Jens

, and even the soccer player Paul Breitner

. Brandt's Ostpolitik as well as his reformist domestic policies were popular with parts of the young generation and led his SPD party to its best-ever federal election result in late 1972. The "Willy-Wahl", Brandt's landslide win was the beginning of the end; and Brandt's role in government started to decline.

Many of Brandt's reforms met with resistance from state governments (dominated by CDU/CSU). The spirit of reformist optimism was cut short by the 1973 oil crisis

and the major public services strike 1974, which gave Germany's trade unions, led by Heinz Kluncker

, a big wage increase but reduced Brandt's financial leeway for further reforms. Brandt was said to be more a dreamer than a manager and was personally haunted by depression. To counter any notions about being sympathetic to Communism or soft on left-wing extremists, Brandt implemented tough legislation that barred "radicals" from public service ("Radikalenerlass").

, was a spy for the East German intelligence services. Brandt was asked to continue working as usual, and he agreed to do so, even taking a private vacation with Guillaume. Guillaume was arrested on 24 April 1974, and many blamed Brandt for having a communist spy in his inner circle. Thus disgraced, Brandt resigned from his position as the Chancellor on 6 May 1974. However, Brandt remained in the Bundestag

and as the Chairman of the Social Democrats through 1987.

This espionage

affair is widely considered to have been just the trigger for Brandt's resignation, not the fundamental cause. Brandt was dogged by scandals about serial adultery, and reportedly also struggled with alcohol and depression. There was also the economic fallout on West Germany of the 1973 oil crisis

, which almost seems to have been enough stress to finish off Brandt as the Chancellor. As Brandt himself later said, "I was exhausted, for reasons which had nothing to do with the process going on at the time." [Where "the process" seems to have been the unfolding of the Guillaume espionage scandal.]

Guillaume had been an espionage agent for East Germany, who was supervised by Markus Wolf

, the head of the "Main Intelligence Administration" of the East German Ministry for State Security. Wolf stated after the reunification that the resignation of Brandt had never been intended, and that the planting and handling of Guillaume had been one of the largest mistakes of the East German secret services.

Brandt was succeeded as the Chancellor of the Bundesrepublik by his fellow Social Democrat, Helmut Schmidt

. For the rest of his life, Brandt remained suspicious that his fellow Social Democrat (and longtime rival) Herbert Wehner

had been scheming for Brandt's downfall. However, there is scant evidence to corroborate this suspicion.

After his term as the Chancellor, Brandt retained his seat in the Bundestag

After his term as the Chancellor, Brandt retained his seat in the Bundestag

, and he remained the Chairman of the Social Democratic Party through 1987. Beginning in 1987, Brandt stepped down to become the Honorary Chairman of the party. Brandt was also a member of the European Parliament

from 1979 to 1983.

(1976–92), during which period the number of Socialist International's mainly European member parties grew until there were more than a hundred socialist, social democratic, and labour political parties around the world. For the first seven years, this growth in SI membership had been prompted by the efforts of the Socialist International's Secretary-General, the Swede Bernt Carlsson

. However, in early 1983, a dispute arose about what Carlsson perceived as the SI president's authoritarian approach. Carlsson then rebuked Brandt saying: "this is a Socialist International — not a German International".

Next, against some vocal opposition, Brandt decided to move the next Socialist International Congress from Sydney, Australia to Portugal

. Following this SI Congress in April 1983, Brandt retaliated against Carlsson by forcing him to step down from his position. However, the Austria

n Prime Minister

, Bruno Kreisky

, argued on behalf of Brandt: "It is a question of whether it is better to be pure or to have greater numbers".

.

In October 1979, Brandt met with the East German dissident, Rudolf Bahro

In October 1979, Brandt met with the East German dissident, Rudolf Bahro

, who had written The Alternative. Bahro and his supporters were attacked by the East German state security organization Stasi

, headed by Erich Mielke

, for his writings, which had laid the theoretical foundation of a leftist opposition to the ruling SED party and its dependent allies, and which promoted new and changed parties. All of this is now described as "change from within". Brandt had asked for Bahro's release, and Brandt welcomed Bahro's theories, which advanced the debate within his own Social Democratic Party. In late 1989, Brandt became one of the first leftist leaders in West Germany to publicly favor a quick reunification

of Germany, instead of some sort of two-state federation or other kind of interim arrangement. Brandt's public statement "Now grows together what belongs together," was widely quoted in those days.

, following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait

in 1990. Brandt secured the release of a large number of them, and on November 9, 1990, his airplane landed with 174 freed hostages on board at the Frankfurt Airport

.

Willy Brandt died of colon cancer

Willy Brandt died of colon cancer

at his home in Unkel

, a town on the Rhine River, on 8 October 1992, and was given a state funeral

. He was buried at the cemetery at Zehlendorf

in Berlin.

When the SPD moved its headquarters from Bonn back to Berlin in the mid-1990s, the new headquarters was named the "Willy Brandt Haus". One of the buildings of the European Parliament in Brussels

was named after him in 2008.

German artist Johannes Heisig

painted several portraits of Brandt of which one was unveiled as part of a honoring event at German Historical Institute Washington, DC on March 18, 2003. Spokesmen amongst others were former German Federal Minister Egon Bahr and former U.S. Secretary of state Henry Kissinger.

In 2009, the University of Erfurt

renamed its graduate school

of public administration

as the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy. A private

German-language

secondary school

in Warsaw

, Poland

, is also named after Brandt.

In 2012, a newly built airport southeast of Germany's capital Berlin

will be opening. Commemorating the legacy of Willy Brandt the name of the airport will be Berlin Brandenburg Airport "Willy Brandt".

in 1948. Hansen and Brandt had three sons: Peter Brandt (born in 1948), Lars Brandt (born in 1951), and Matthias Brandt (born in 1961). Today Peter is a historian, Lars is an artist, and Matthias is an actor. After 32 years of marriage, Willy Brandt and Rut Hansen Brand divorced in 1980, and from the day that they were divorced, they never saw each other again. On 9 December 1983, Brandt married Brigitte Seebacher (born in 1946).

Rut Hansen Brandt outlived Willy Brandt but died on 28 July 2006 in Berlin.

of his father called "Andenken" ('Remembrance'). This book has been the subject of some controversy. Some see it as a loving memory of the father-son-relationship, but others label it as a ruthless statement of a son who still thinks that he never had a father who really loved him.

2002f, Berliner Ausgabe, Werkauswahl, ed. for Bundeskanzler Willy Brandt Stiftung by Helga Grebing, Gregor Schöllgen and Heinrich August Winkler, 10 volumes, Dietz Verlag, Bonn 2002f, Collected Writings, ISBN 3-8012-0305-0

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

politician, Mayor of West Berlin 1957–1966, Chancellor of West Germany

West Germany

West Germany is the common English, but not official, name for the Federal Republic of Germany or FRG in the period between its creation in May 1949 to German reunification on 3 October 1990....

1969–1974, and leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

(SPD) 1964–1987.

Brandt's most important legacy was Ostpolitik

Ostpolitik

Neue Ostpolitik , or Ostpolitik for short, refers to the normalization of relations between the Federal Republic of Germany and Eastern Europe, particularly the German Democratic Republic beginning in 1969...

, a policy aimed at improving relations with East Germany, Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, and the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. This policy caused considerable controversy in West Germany, but won Brandt the Nobel Peace Prize

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes bequeathed by the Swedish industrialist and inventor Alfred Nobel.-Background:According to Nobel's will, the Peace Prize shall be awarded to the person who...

in 1971.

In 1974, Brandt resigned as Chancellor after Günter Guillaume

Günter Guillaume

Günter Guillaume , was an intelligence agent of East Germany's secret service, the Stasi.Guillame was born in Berlin. During the Hitler era, he was a member of the Nazi party NSDAP. In 1956, he and his wife Christel emigrated to West Germany on Stasi orders to penetrate and spy on West Germany's...

, one of his closest aides, was exposed as an agent of the Stasi

Stasi

The Ministry for State Security The Ministry for State Security The Ministry for State Security (German: Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (MfS), commonly known as the Stasi (abbreviation , literally State Security), was the official state security service of East Germany. The MfS was headquartered...

, the East German secret service

Secret service

A secret service describes a government agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For instance, a country may establish a secret service which has some...

.

Early life, the war

Willy Brandt was born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm in the Free City of Lübeck (German EmpireGerman Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

) to Martha Frahm, an unwed mother who worked as a cashier for a department store. His father was an accountant from Hamburg named John Möller, whom Brandt never met. As his mother worked six days a week, he was mainly brought up by his mother's stepfather Ludwig Frahm and his second wife Dora.

After passing his Abitur

Abitur

Abitur is a designation used in Germany, Finland and Estonia for final exams that pupils take at the end of their secondary education, usually after 12 or 13 years of schooling, see also for Germany Abitur after twelve years.The Zeugnis der Allgemeinen Hochschulreife, often referred to as...

in 1932 at Johanneum zu Lübeck, he became an apprentice at the shipbroker and ship's agent F.H. Bertling. He joined the "Socialist Youth" in 1929 and the Social Democratic Party

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

(SPD) in 1930. He left the SPD to join the more left wing Socialist Workers Party (SAP), which was allied to the POUM

Workers' Party of Marxist Unification

The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification was a Spanish communist political party formed during the Second Republic and mainly active around the Spanish Civil War...

in Spain and the Independent Labour Party

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party was a socialist political party in Britain established in 1893. The ILP was affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 to 1932, when it voted to leave...

in Britain. In 1933, using his connections with the port and its ships, he left Germany for Norway

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

to escape Nazi

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

persecution. It was at this time that he adopted the pseudonym

Pseudonym

A pseudonym is a name that a person assumes for a particular purpose and that differs from his or her original orthonym...

Willy Brandt to avoid detection by Nazi agents. In 1934, he took part in the founding of the International Bureau of Revolutionary Youth Organizations

International Bureau of Revolutionary Youth Organizations

International Bureau of Revolutionary Youth Organizations was an international organization of socialist youth, formed in 1934...

, and was elected to its Secretariat.

Brandt was in Germany from September to December 1936, disguised as a Norwegian student named Gunnar Gaasland. He was married to Gertrud Meyer from Lübeck

Lübeck

The Hanseatic City of Lübeck is the second-largest city in Schleswig-Holstein, in northern Germany, and one of the major ports of Germany. It was for several centuries the "capital" of the Hanseatic League and, because of its Brick Gothic architectural heritage, is listed by UNESCO as a World...

in a fictitious marriage to protect her from deportation. Meyer had joined Brandt in Norway in July 1933. In 1937, during the Civil War

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

, Brandt worked in Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

as a journalist. In 1938, the German government revoked his citizenship, so he applied for Norwegian citizenship

Norwegian nationality law

Norwegian nationality law is based on the principle of Jus sanguinis. In general, Norwegian citizenship is conferred by birth to a Norwegian parent, or by naturalisation in Norway.Norway restricts, but does not absolutely prohibit, dual citizenship....

. In 1940, he was arrested in Norway by occupying German forces, but was not identified as he wore a Norwegian uniform. On his release, he escaped to neutral Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

. In August 1940, he became a Norwegian citizen, receiving his passport from the Norwegian embassy in Stockholm

Stockholm

Stockholm is the capital and the largest city of Sweden and constitutes the most populated urban area in Scandinavia. Stockholm is the most populous city in Sweden, with a population of 851,155 in the municipality , 1.37 million in the urban area , and around 2.1 million in the metropolitan area...

, where he lived until the end of the war. Willy Brandt lectured in Sweden on 1 December 1940 at Bommersvik

Bommersvik

Bommersvik is a Union college built by the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League and is situated outside the municipality of Södertälje in Sweden. Parts of the college grounds encompass a conference centre and recreational facilities that are extensively used by social democratic organizations...

college about problems experienced by the social democrats in Nazi Germany and the occupied countries at the start of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. In exile in Norway and Sweden Brandt learned Norwegian

Norwegian language

Norwegian is a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Norway, where it is the official language. Together with Swedish and Danish, Norwegian forms a continuum of more or less mutually intelligible local and regional variants .These Scandinavian languages together with the Faroese language...

and Swedish

Swedish language

Swedish is a North Germanic language, spoken by approximately 10 million people, predominantly in Sweden and parts of Finland, especially along its coast and on the Åland islands. It is largely mutually intelligible with Norwegian and Danish...

. Brandt spoke Norwegian fluently, and retained a close relationship with Norway.

In late 1946, Brandt returned to Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

, working for the Norwegian government. In 1948, he joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

(SPD) and became a German citizen again, formally adopting the pseudonym, Willy Brandt, as his legal name.

Politician

Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall was a barrier constructed by the German Democratic Republic starting on 13 August 1961, that completely cut off West Berlin from surrounding East Germany and from East Berlin...

. In Brandt's first year as Mayor, he also served as the President of the Bundesrat

Bundesrat of Germany

The German Bundesrat is a legislative body that represents the sixteen Länder of Germany at the federal level...

in Bonn

Bonn

Bonn is the 19th largest city in Germany. Located in the Cologne/Bonn Region, about 25 kilometres south of Cologne on the river Rhine in the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, it was the capital of West Germany from 1949 to 1990 and the official seat of government of united Germany from 1990 to 1999....

. Brandt was outspoken against the Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

repression of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution

1956 Hungarian Revolution

The Hungarian Revolution or Uprising of 1956 was a spontaneous nationwide revolt against the government of the People's Republic of Hungary and its Soviet-imposed policies, lasting from 23 October until 10 November 1956....

and against Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

's 1958 proposal that Berlin receive the status of a "free city

Free city

Free city may refer to:* City-state, region controlled exclusively by a sovereign city* Free city a self-governed city during the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial eras* Free City , album by the St...

". He was supported by the influential publisher Axel Springer

Axel Springer

Axel Springer , was a German journalist and the founder and owner of the Axel Springer AG publishing company.-Early life:...

. As Mayor of West Berlin, Brandt accomplished much in the way of urban development. New hotels, office-blocks and flats were constructed, while both Schloss Charlottenburg and the Reichstag

Reichstag

Reichstag may refer to:*Reichstag – the diets or parliaments of the Holy Roman Empire, of the Austrian-Hungarian monarchy, and of Germany from 1871 to 1945** Reichstag ** Reichstag...

were restored. Sections of the "Stadtring" Bundesautobahn 100

Bundesautobahn 100

is an Autobahn in Germany. The A 100 encloses the city centre of the German capital Berlin, running from the Wedding district of the Berlin-Mitte borough in a southwestern bow through Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf and Tempelhof-Schöneberg to Neukölln...

inner-city motorway were opened, while a major housing programme was carried out, with roughly 20,000 new dwellings built each year during his time in office.

At the start of 1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy saw Brandt as the wave of the future in West Germany and was hoping he would replace Konrad Adenauer as chancellor following elections later in the year. Kennedy made this preference clear by inviting Brandt, the West German opposition leader, to an official meeting at the White House a month before meeting with Adenauer, the country’s leader. The diplomatic snub strained relations between Kennedy and Adenauer further during an especially tense time for Berlin. However, following the building of the Berlin Wall in August 1961, Brandt was disappointed and angry with Kennedy. Speaking in Berlin three days later, Brandt criticized Kennedy, asserting "Berlin expects more than words. It expects political action." He also wrote Kennedy a highly critical public letter in which he warned that the development was liable "to arouse doubts about the ability of the three [Allied] Powers to react and their determination" and he called the situation "a state of accomplished extortion"."

Brandt became the Chairman of the SPD in 1964, a post that he retained until 1987, longer than any other party Chairman since its foundation by August Bebel

August Bebel

Ferdinand August Bebel was a German Marxist politician, writer, and orator. He is best remembered as one of the founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.-Early years:...

. Brandt was the SPD candidate for the Chancellorship in 1961, but he lost to Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer was a German statesman. He was the chancellor of the West Germany from 1949 to 1963. He is widely recognised as a person who led his country from the ruins of World War II to a powerful and prosperous nation that had forged close relations with old enemies France,...

's conservative Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU). In 1965, Brandt ran again, but lost to the popular Ludwig Erhard

Ludwig Erhard

Ludwig Wilhelm Erhard was a German politician affiliated with the CDU and Chancellor of West Germany from 1963 until 1966. He is notable for his leading role in German postwar economic reform and economic recovery , particularly in his role as Minister of Economics under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer...

. Erhard's government was short-lived, however, and in 1966 a grand coalition

Grand coalition

A grand coalition is an arrangement in a multi-party parliamentary system in which the two largest political parties of opposing political ideologies unite in a coalition government...

between the SPD and CDU was formed, with Brandt as Foreign Minister and Vice-Chancellor.

Chancellor

At the 1969 elections, again with Brandt as the leading candidate, the SPD became stronger, and after three weeks of negotiations, the SPD formed a coalitionSocial-liberal coalition

Social-liberal coalition in Germany refers to a governmental coalition formed by the Social Democratic Party and the Free Democratic Party .The term stems from social democracy of the SPD and the liberalism of the FDP...

government with the smaller Free Democratic Party of Germany (FDP). Brandt was elected Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Foreign policy

As Chancellor, Brandt developed his Neue OstpolitikOstpolitik

Neue Ostpolitik , or Ostpolitik for short, refers to the normalization of relations between the Federal Republic of Germany and Eastern Europe, particularly the German Democratic Republic beginning in 1969...

(New Eastern Policy). Brandt was active in creating a degree of rapprochement with East Germany, and also in improving relations with the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, and other Eastern Bloc

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

(communist) countries. A seminal moment came in December 1970 with the famous Warschauer Kniefall

Warschauer Kniefall

Kniefall von Warschau refers to a gesture of humility and penance by social democratic Chancellor of Germany Willy Brandt towards the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.-Incident:...

in which Brandt, apparently spontaneously, knelt down at the monument to victims of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the Jewish resistance that arose within the Warsaw Ghetto in German occupied Poland during World War II, and which opposed Nazi Germany's effort to transport the remaining ghetto population to Treblinka extermination camp....

. The uprising occurred during the Nazi German military occupation of Poland, and the monument is to those killed by the German troops who suppressed the uprising and deported remaining ghetto residents to the concentration camps for extermination.

Time

Time (magazine)

Time is an American news magazine. A European edition is published from London. Time Europe covers the Middle East, Africa and, since 2003, Latin America. An Asian edition is based in Hong Kong...

magazine in the U.S.A. named Brandt as its Man of the Year for 1970, stating, "Willy Brandt is in effect seeking to end World War II by bringing about a fresh relationship between East and West. He is trying to accept the real situation in Europe, which has lasted for 25 years, but he is also trying to bring about a new reality in his bold approach to the Soviet Union and the East Bloc."

In 1971, Brandt received the Nobel Peace Prize

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes bequeathed by the Swedish industrialist and inventor Alfred Nobel.-Background:According to Nobel's will, the Peace Prize shall be awarded to the person who...

for his work in improving relations with East Germany, Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, and the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

.

Brandt negotiated a peace treaty between the Federal Republic of Germany and Poland, and agreements on the boundaries between the two countries, signifying the official and long-delayed end of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. Brandt negotiated parallel treaties and agreements between the Federal Republic and Czechoslovakia.

In West Germany, Brandt's Neue Ostpolitik was extremely controversial, dividing the populace into two camps: one camp, embracing all of the conservative parties and most notably the victims i.e. those German-speaking, West German residents and their subsequent families who were driven west ("die Heimatvertriebenen") by Stalinist ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic orreligious group from certain geographic areas....

from Historical Eastern Germany

Historical Eastern Germany

The former eastern territories of Germany are those provinces or regions east of the current eastern border of Germany which were lost by Germany during and after the two world wars. These territories include the Province of Posen and East Prussia, Farther Pomerania, East Brandenburg and Lower...

, especially the part that was arbitrarily given to Poland by the Stalinists; western Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

(the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

); and the rest of Eastern Europe, such as in Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

. These groups of displaced Germans and their descendants loudly voiced their opposition to Brandt's policy, calling it "illegal" and "high treason".

A different camp supported and encouraged Brandt's Neue Ostpolitik as aiming at "Wandel durch Annäherung" ("change through rapprochement

Rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word rapprocher , is a re-establishment of cordial relations, as between two countries...

"), encouraging change through a policy of engagement with the (communist) Eastern Bloc, rather than trying to isolate those countries diplomatically and commercially. Brandt's supporters claim that the policy did help to break down the Eastern Bloc's "siege mentality

Siege mentality

Siege mentality is a shared feeling of victimization and defensiveness. It is a state of mind whereby one believes that one is being constantly attacked, oppressed, or isolated and makes one frightened of surrounding people...

", and also helped to increase its awareness of the contradictions in its brand of Socialism/Communism, which – together with other events – eventually led to the downfall of Eastern European Communism and Stalinism.

Political and social changes

West Germany in the late 1960s was shaken by student disturbancesGerman student movement

The German student movement was a protest movement that took place during the late 1960s in West Germany. It was largely a reaction against the perceived authoritarianism and hypocrisy of the German government and other Western governments, and the poor living conditions of students...

and a general "change of the times" that not all Germans were willing to accept or approve. What had seemed a stable, peaceful nation, happy with its outcome of the "Wirtschaftswunder" ("economic miracle") faced economic turbulence. The German baby-boom generation wanted to come to terms with the deeply conservative, bourgeois, and demanding parent generation. The baby-boomer students were the most outspoken, and they accused their "parental generation" of being outdated and old-fashioned and even of having a Nazi past. Compared to their forebears, the "skeptical generation" was much more capricious, willing to embrace more extreme socialist ideology (such as Maoism), and public heroes (such as Ho Chi Minh

Ho Chi Minh

Hồ Chí Minh , born Nguyễn Sinh Cung and also known as Nguyễn Ái Quốc, was a Vietnamese Marxist-Leninist revolutionary leader who was prime minister and president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam...

, Fidel Castro

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz is a Cuban revolutionary and politician, having held the position of Prime Minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976, and then President from 1976 to 2008. He also served as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba from the party's foundation in 1961 until 2011...

, and Che Guevara

Che Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara , commonly known as el Che or simply Che, was an Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, intellectual, guerrilla leader, diplomat and military theorist...

), while living a looser and more promiscuous lifestyle. Students and young apprentices could afford to move out of their parents' homes, and left-wing politics was considered to be chic

Radical chic

Radical chic is a term coined by journalist Tom Wolfe in his 1970 essay "Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny's," to describe the adoption and promotion of radical political causes by celebrities, socialites, and high society...

, as well as taking part in American-style political demonstrations against having American military forces in South Vietnam

South Vietnam

South Vietnam was a state which governed southern Vietnam until 1975. It received international recognition in 1950 as the "State of Vietnam" and later as the "Republic of Vietnam" . Its capital was Saigon...

.

Brandt's popularity

Brandt's predecessor as Chancellor, Kurt Georg KiesingerKurt Georg Kiesinger

Kurt Georg Kiesinger was a German politician affiliated with the CDU and Chancellor of West Germany from 1 December 1966 until 21 October 1969.-Early career and wartime activities:...

, had been a member of the Nazi party, and was a more old-fashioned conservative-liberal intellectual. Brandt, having fought the Nazis and having faced down communist Eastern Germany during several crises while he was the Mayor of Berlin, became a controversial, but credible, figure in several different factions. As the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Kiesinger's grand coalition

Grand coalition

A grand coalition is an arrangement in a multi-party parliamentary system in which the two largest political parties of opposing political ideologies unite in a coalition government...

cabinet, Brandt helped to gain further international approval for Western Germany, and he laid the foundation stones for his future Neue Ostpolitik. There was a wide public-opinion gap between Kiesinger and Brandt in the West German polls.

Ausserparlamentarische Opposition

The Außerparlamentarische Opposition , was a political protest movement active in West Germany during the latter half of the 1960s and early 1970s, forming a central part of the German student movement...

" (APO) ("the extra-parliamentary opposition"). The students questioned West German society in general, seeking social, legal, and political reforms. Also, the unrest led to a renaissance of right-wing parties in some of the Bundeslands' (German states under the Bundesrepublik) Parliaments.

Brandt, however, represented a figure of change, and he followed a course of social, legal, and political reforms. In 1969, Brandt gained a small majority by forming a coalition with the FDP. In his first speech before the Bundestag as the Chancellor, Brandt set forth his political course of reforms ending the speech with his famous words, "Wir wollen mehr Demokratie wagen" (literally: "We want to take a chance on more Democracy", or more figuratively, "Let's dare more democracy"). This speech made Brandt, as well as the Social Democratic Party, popular among most of the students and other young West German baby-boomers who dreamed of a country that would be more open and more colorful than the frugal and still somewhat-authoritarian Bundesrepublik that had been built after World War II. However, Brandt's Neue Ostpolitik lost for him a large part of the German refugee (from the East) voters who had been significantly pro-SPD in the postwar years.

Chancellor of domestic reform

Although Brandt is perhaps best known for his achievements in foreign policy, his government oversaw the implementation of a broad range of social reforms, and was known as a "Kanzler der inneren Reformen" ('Chancellor of domestic reform'). Acording to the historian David ChildsDavid Childs

David M. Childs is the Consulting Design Partner at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. He is best known for his redesign of the new One World Trade Center in New York....

, “Brandt was anxious that his government should be a reforming administration and a number of reforms were embarked upon”. Within a few years, the education budget rose from 16 billion to 50 billion DM, while one out of every three DM spent by the new government was devoted to welfare purposes. As noted by the journalist and historian Marion Dönhoff

Marion Dönhoff

Marion Hedda Ilse Gräfin von Dönhoff was a German journalist who participated in the resistance against Hitler's National Socialists with Helmuth James Graf von Moltke, Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, and Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg. After the war, she became one of the leading German...

,

“People were seized by a completely new feeling about life. A mania for large scale reforms spraed like wildfire, affecting schools, universities, the administration, family legislation. In the autumn of 1970 Jurgen Wischnewski of the SPD declared, ‘Every week more than three plans for reform come up for decision in cabinet and in the Assembly.’ ”

According to Helmut Schmidt

Helmut Schmidt

Helmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt is a German Social Democratic politician who served as Chancellor of West Germany from 1974 to 1982. Prior to becoming chancellor, he had served as Minister of Defence and Minister of Finance. He had also served briefly as Minister of Economics and as acting...

, Willy Brandt's domestic reform programme had accomplished more than any previous programme for a comparable period. A number of liberal social reforms were instituted whilst the welfare state was significantly expanded (with total public spending on social programs nearly doubling between 1969 and 1975), with health, housing, and social welfare legislation bringing about welcome improvements, and by the end of the Brandt Chancellorship West Germany had one of the most advanced systems of welfare in the world.

Amongst his achievements as Chancellor were:

- Substantial increases in social security benefits such as injury and sickness benefits, pensions, unemployment benefits, housing allowances, basic subsistence aid allowances, and family allowances and living allowances. In the government’s first budget, sickness benefits were increased by 9.3%, pensions for war widows by 25%, pensions for the war wounded by 16%, and recruitment pensions by 5%. Numerically, pensions went up by 6.4% (1970), 5.5% (1971), 9.5% (1972), 11.4% (1973), and 11.2% (1974). Adjusted for changes in the annual price index, pensions went up in real terms by 3.1% (1970), 0.3% (1971), 3.9% (1972), 4.4% (1973), and 4.2% (1974). Between 1972 and 1974, the purchasing power of pensioners increased by 19%.

- Improvements in sick pay provision.

- An expanded sickness insurance scheme, with the inclusion of preventative treatment.

- The allocation of more funds towards housing, transportation, schools, and communication.

- The index-linking of the income limit for compulsory sickness insurance to changes in the wage level (1970).

- The incorporation of pupils, students and children in kindergartens into the accident insurance scheme (1971), which benefited 11 million children.

- The introduction of generous public stipends for students to cover their living costs.

- The conversion of West German universities from elite schools into mass institutions.

- The Farmers’ Sickness Insurance Law (1972), which introduced compulsory sickness insurance for independent farmers, family workers in agriculture, and pensioners under the farmers’ pension scheme, medical benefits for all covered groups, and cash benefits for family workers under compulsory coverage for pension insurance.

- The introduction of voluntary retirement at 63 with no deductions in the level of benefits.

- The index-linking of war victim’s pensions to wage increases.

- An increase in spending on research and education by nearly 300% between 1970 and 1974.

- The raising of the school leaving age to 16.

- The abolition of fees for higher or further education.

- A considerable increase in the number of higher education institutions.

- The introduction of grants for pupils from lower income groups to stay on at school.

- The introduction of grants for those going into any kind of higher or further education.

- Increases in educational allowances.

- Greater spending on science.

- The introduction of "Vergleichmieten" ('comparable rents'), a loose form of rent regulation.

- A significant rise in the income limit for social housing (1971).

- Increased levels of protection and support for low-income tenants and householders, which led to a drop in the number of eviction notices. By 1974, three times as much was paid out in rent subsidies as in 1969, and nearly one and a half million households received rental assistance.

- Increases in public housing subsidies, as characterised by a 36% increase in the social housing budget in 1970 and by the introduction of a programme for the construction of 200,000 public housing units (1971).

- The establishment of a federal environmental programme (1971).

- Reforms to the armed forces, as characterised by a reduction in basic military training from eighteen to fifteen months and a reorganisation of education and training, as well as personnel and procurement procedures.

- The establishment of a women’s policy machinery at the national level (1972).

- The establishment of a Federal Environment Agency (1974) to conduct research into environmental issues and prevent pollution.

- The introduction of redundancy allowances in cases of bankruptcies (1974).

- Improvements in income and work conditions for home workers.

- The introduction of new provisions for the rehabilitation of severely disabled people ("Schwerbehinderte") and accident victims.

- The introduction of guaranteed minimum pension benefits for all West Germans.

- The introduction of fixed minimum rates for women in receipt of very low pensions, and equal treatment for war widows.

- An amendment to the Labour Management Act (1971) which granted workers co-determination on the shop floor.

- The Factory Constitution Law (1971), which strengthened the rights of individual employees “to be informed and to be heard on matters concerning their place of work.” The Works’ Council was provided with greater authority while trade unions were given the right of entry into the factory “provided they informed the employer of their intention to do so”.

- The passage of a law to encourage wider share ownership by workers and other rank-and-file employees.

- An increase in federal aid to sports’ organisations.

- Efforts to improve the railways and motorways.

- A new Factory Management Law (1972) which extended co-determination at the factory level.

- The passing of a law in 1974 to allow for worker representation on the boards of large firms (although this change was not enacted until 1976, after alterations were made).

- The extension of accident insurance to non-working adults.

- The introduction of greater legal rights for women, as exemplified by the standardisation of pensions, divorce laws, regulations governing use of surnames, and the introduction of measures to bring more women into politics.

- The Town Planning Act (1971), which encouraged the preservation of historical heritage and helped open up the way to the future of many German cities.

- An addition to the Basic Law which gave the Federal Government some responsibility for educational planning.

- A big increase in spending on education, with educational expenses per head of the population multiplied by five.

- The passing of the Severely Disabled Persons Act (1974), which obliged all employers with more than fifteen employees to ensure that 6% of their workforce was persons officially recognised as being severely disabled. Employers who failed to do so were assessed 100 DM per month for every job falling before the required quota. These compensatory payments were used to subsidise the adaptation of workplaces to the requirements of those who were severely disabled.

- Amendments to the Federal Social Assistance Act (1974). “Help for the vulnerable” was renamed “help for overcoming particular social difficulties,” and the numbers of people eligible for assistance was greatly extended to include all those “whose own capabilities cannot meet the increasing demands of modern industrial society.” The intention of these amendments was to include especially such groups as discharged prisoners, drug and narcotic addicts, alcoholics, and the homeless. As a result of these changes, people who formerly had to be supported by their relatives were now entitled to social assistance.

- The passing of a Foreign Tax Act, which limited the possibility of tax evasion.

- The Urban Renewal Act (1971), which helped the states to restore their inner cities and to develop new neighbourhoods.

- The lowering of the voting age from 21 to 18.

- Improvements in pension provision for women and the self-employed.

- The introduction of a new minimum pension for workers with at least twenty-five years’ insurance.

- The Second Sickness Insurance Modification Law (1972), which linked the indexation of the income-limit for compulsory employee coverage to the development of the pension insurance contribution ceiling (75% of the ceiling), obliged employers to pay half of the contributions in the case of voluntary membership, extended the criteria for voluntary membership of employees, and introduced preventive medical check-ups for certain groups.

- The Pension Reform Law (1972), which guaranteed all retirees a minimum pension regardless of their contributions and institutionalized the norm that the standard pension (of average earners with forty years of contributions) should not fall below 50% of current gross earnings. The 1972 pension reforms improved eligibility conditions and benefits for nearly every subgroup of the West German population. The income replacement rate for employees who made full contributions was raised to 70% of average earnings. The reform also replaced 65 as the mandatory retirement age with a “retirement window” ranging between 63 and 65 for employees who had worked for at least thirty-five years. Employees who qualified as disabled and had worked for at least thirty-five years were extended a more generous retirement window, which ranged between the ages of 60 and 62. Women who had worked for at least fifteen years (ten of which had to be after the age of age 40), and the long-term unemployed were also granted the same retirement window as the disabled. In addition, there were no benefit reductions for employees who had decided to retire earlier than the age of 65.. The legislation also changed the way in which pensions were calculated for low-income earners who had been covered for twenty-five or more years. If the pension benefit fell below a specified level, then such workers were allowed to substitute a wage figure of 75% of the average wage during this period, thus creating something like a minimum wage benefit..

- The introduction of a pension reform package, which incorporated an additional year of insurance for mothers.

- The liberalisation of the penal code.

- An increase in tax-free allowances for children, which enabled 1,000,000 families to claim an allowance for the second child, compared to 300,000 families previously.

- The exemption of pensioners from paying a 2% health insurance contribution.

- The Hospital Financing Law (1972), which secured the supply of hospitals and reduced the cost of hospital care, “defined the financing of hospital investment as a public responsibility, single states to issue plans for hospital development, and the federal government to bear the cost of hospital investment covered in the plans, rates for hospital care thus based on running costs alone, hospitals to ensure that public subsidies together with insurance fund payments for patients cover total costs”.

- A new fund of 100 million marks for disabled children.

- The granting of equal rights to illegitimate children (1970).

- A law for the creation of property for workers, under which a married worker would normally keep up to 95% of his pay, and graded tax remission for married wage-earners applied up to a wage of 48,000 marks, which indicated the economic prosperity of West Germany at that time.

- The Benefit Improvement Law (1973), which made entitlement to hospital care legally binding (entitlements already enjoyed in practice), abolished time limits for hospital care, introduced entitlement to household assistance under specific conditions, and also introduced entitlement to leave of absence from work and cash benefits in the event of a child’s illness.

- Increased allowances for retraining and advanced training and for refugees from East Germany.

- The Seventh Modification Law (1973), which linked the indexation of farmers’ pensions to the indexation of the general pension insurance scheme.

- An increase in federal grants for sport.

- The Third Modification Law (1974), which extended individual entitlements to social assistance by means of higher-income limits compatible with receipt of benefits and lowered age limits for certain special benefits. Rehabilitation measures were also extended, child supplements were expressed as percentages of standard amounts and were thus indexed to their changes, and grandparents of recipients were exempted from potential liability to reimburse expenditure of social assistance carrier.

- An amendment to a federal civil service reform bill (1971) which enabled fathers to apply for part-time civil service work.

- The allocation to local communities of matching grants covering 90% of infrastructure development. This led to a dramatic increase in the number of public swimming pools and other facilities of consumptive infrastructure throughout West Germany.

- A modernization of the federal crime-fighting apparatus.

- The Third Social Welfare Amendment Act (1974), which brought considerable improvements for the handicapped, those in need of care, and older persons.

- The introduction of a matching fund program for 15 million employees, which stimulated them to accumulate capital.

- A much needed school and college construction program.

- The Industrial Relations Law (1972) and the Personnel Representation Act (1974), which not only broadened the rights of employees in matters which immediately affected their places of work, but also improved the possibilities for codetermination on operations committees, together with access of trade unions to companies.

- The introduction of substantial federal benefits for farmers.

- The passage of a progressive anticartel law.

- The introduction of legislation which ensured continued payment of wages for workers disabled by illness (1970).

- A modernization of the armed forces establishment.

- The introduction of postgraduate support for highly qualified graduates, providing them with the opportunity to earn their doctorates or undertake research studies.

- The introduction of a contributory medical service for 23 million panel patients.

- The Third Law for the Liberalization of the Penal Code (1970), which liberalized “the right to political demonstration”.

- The introduction of free hospital care for 9 million recipients of social relief.

- The lowering of the age of eligibility for political office to twenty-one.

- Increases in the pensions of 2.5 million war victims.

- The lowering of the office age of majority to eighteen (March 1974).

- An increase in the number of teachers.

- The passage of a law which guaranteed “amnesty in minor offences connected with demonstrations.”

- The attainment of a lower rate of inflation than in other industrialised countries at that time.

- A rise in the standard of living, helped by the floating and revaluation of the mark. This was characterised by the real incomes of employees increasing more sharply than incomes from entrepreneurial work, with the proportion of employees’ incomes in the overall national income rising from 65% to 70% between 1969 and 1973, while the proportion of income from entrepreneurial work and property fell over that same period from just under 35% to 30.%

First cabinet

- Willy Brandt (SPDSocial Democratic Party of GermanyThe Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

) - Chancellor - Walter ScheelWalter ScheelWalter Scheel is a German politician . He served as Federal Minister of Economic Cooperation and Development from 1961 to 1966, Foreign Minister of Germany and Vice Chancellor from 1969 to 1974, acting Chancellor of Germany from 7 May to 16 May 1974 , and finally as President of the Federal...

(FDP) - Vice Chancellor and Minister of Foreign Affairs - Helmut SchmidtHelmut SchmidtHelmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt is a German Social Democratic politician who served as Chancellor of West Germany from 1974 to 1982. Prior to becoming chancellor, he had served as Minister of Defence and Minister of Finance. He had also served briefly as Minister of Economics and as acting...

(SPD) - Minister of Defense - Hans-Dietrich GenscherHans-Dietrich GenscherHans-Dietrich Genscher is a German politician of the liberal Free Democratic Party . He served as Foreign Minister and Vice Chancellor of Germany from 1974 to 1982 and, after a two-week pause, from 1982 to 1992, making him Germany's longest serving Foreign Minister and Vice Chancellor...

(FDP) - Minister of the Interior - Alex MöllerAlex MöllerAlexander Johann Heinrich Friedrich Möller, known as Alex Möller was a German politician .Möller was born in Dortmund. He was a member of the Landtag of Baden-Württemberg from 1946 to October 5, 1961, when he was elected to the Bundestag. His successor was Walther Wäldele...

(SPD) - Minister of Finance - Gerhard JahnGerhard JahnGerhard Jahn was a German politician and a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany...

(SPD) - Minister of Justice - Karl SchillerKarl SchillerKarl August Fritz Schiller was a German scientist and politician of the Social Democratic Party . From 1966 to 1972, he was Federal Minister of Economic Affairs and from 1971 to 1972 Federal Minister of Finance...

(SPD) - Minister of Economics - Walter Arendt (SPD) - Minister of Labour and Social Affairs

- Josef Ertl (FDP) - Minister of Food, Agriculture, and Forestry

- Georg LeberGeorg LeberGeorg Leber is a German politician in the Social Democratic Party of Germany .After serving in the Luftwaffe in World War 2, he joined the SPD in 1947...

(SPD) - Minister of Transport, Posts, and Communications - Lauritz LauritzenLauritz LauritzenLauritz Lauritzen was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany . He was born in Kiel and died in Bad Honnef....

(SPD) - Minister of Construction - Käte StrobelKäte StrobelKäte Strobel was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany .Born in Nuremberg, from 1923 to 1938 Käte Müller worked in the office of agricultural organisations in Bavaria. In 1928, she married Hans Strobel, who in 1934 was arrested for planning high treason against the Nazis...

(SPD) - Minister of Youth, Family, and Health - Hans LeussinkHans LeussinkHans Leussink was a German teacher and politician. He served as the country's Minister for Education and Research from 1969 to 1972....

- Minister of Education and Science - Erhard EpplerErhard EpplerErhard Eppler is a German Social Democratic politician and founder of the GTZ .- Early years :Born in Ulm, Erhard Eppler grew up in Schwäbisch Hall, where his father was the headmaster of the local grammar school. From 1943 to 1945 he served as a soldier in an anti-aircraft unit...

(SPD) - Minister of Economic Cooperation - Horst EhmkeHorst EhmkeHorst Paul August Ehmke is a German lawyer, law professor and politician of the Social Democratic Party . He served as Federal Minister of Justice , Chief of Staff at the German Chancellery and Federal Minister for Special Affairs and Federal Minister for Research, Technology, and Post...

(SPD) - Minister of Special Tasks - Egon Franke (SPD) - Minister of Intra-German Relations

Cabinet changes

- 13 May 1971 - Karl SchillerKarl SchillerKarl August Fritz Schiller was a German scientist and politician of the Social Democratic Party . From 1966 to 1972, he was Federal Minister of Economic Affairs and from 1971 to 1972 Federal Minister of Finance...

(SPD) succeeds Möller as Minister of Finance, remaining also Minister of Economics - 15 March 1972 - Klaus von DohnanyiKlaus von DohnanyiKlaus von Dohnanyi is a German politician and a member of the Social Democratic Party . Dohnanyi is the son of Hans and Christine Dohnanyi, and thus a nephew of Dietrich Bonhoeffer...

(SPD) succeeds Leussink as Minister of Education and Science. - 7 July 1972 - Helmut SchmidtHelmut SchmidtHelmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt is a German Social Democratic politician who served as Chancellor of West Germany from 1974 to 1982. Prior to becoming chancellor, he had served as Minister of Defence and Minister of Finance. He had also served briefly as Minister of Economics and as acting...

(SPD) succeeds Schiller as Minister of Finance and Economics. Georg LeberGeorg LeberGeorg Leber is a German politician in the Social Democratic Party of Germany .After serving in the Luftwaffe in World War 2, he joined the SPD in 1947...

(SPD) succeeds Schmidt as Minister of Defence. Lauritz LauritzenLauritz LauritzenLauritz Lauritzen was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany . He was born in Kiel and died in Bad Honnef....

(SPD) succeeds Leber as Minister of Transport, Posts, and Communications, remaining also Minister of Construction.

1972 crisis

Brandt's Ostpolitik led to a meltdown of the narrow majority Brandt's coalition enjoyed in the Bundestag. In October 1970, FDP deputies Erich MendeErich Mende

Dr. Erich Mende was a German politician of the FDP and CDU. He was the leader of FDP 1960 - 1968.-Early life:Mende was born in Gross-Strehlitz, Upper Silesia,...

, Heinz Starke, and Siegfried Zoglmann crossed the floor to join the CDU. On 23 February 1972, SPD deputy Herbert Hupka

Herbert Hupka

Herbert Hupka was a German journalist and politician .Hupka was born in Diyatalawa, Sri Lanka, to a Silesian German Catholic professor Erich Hupka and a Jewish-German Lutheran mother Sara Rosenthal. Herbert Hupka raised in Ratibor, Upper Silesia...

, who was also leader of the Bund der Vertriebenen

Federation of Expellees

The Federation of Expellees or Bund der Vertriebenen is a non-profit organization formed to represent the interests of Germans who either fled their homes in parts of Central and Eastern Europe, or were expelled following World War II....

, joined the CDU in disagreement with Brandt's reconciliatory efforts towards the east. On 23 April 1972, Wilhelm Helms (FDP) left the coalition ; the FDP politicians Knud von Kühlmann-Stumm and Gerhard Kienbaum also declared that they would vote against Brandt; thus, Brandt had lost his majority. On 24 April 1972 a vote of no confidence was proposed and it was voted on three days later. Had this motion passed, Rainer Barzel

Rainer Barzel

Rainer Candidus Barzel was a German politician of the CDU.Born in Braunsberg, East Prussia , Barzel served as Chairman of the CDU from 1971 and 1973 and ran as the CDU's candidate for Chancellor of Germany in the 1972 federal elections, losing to Willy Brandt's SPD.The 1972 election is commonly...

would have replaced Brandt as Chancellor. To everyone's surprise, the motion failed: Barzel got only 247 votes out of 260 ballots; for an absolute majority, 249 votes would have been necessary. There were also 10 votes against the motion and 3 invalid ballots. Most deputies of SPD and FDP did not take part in the voting, as not voting had the same effect as voting pro Brandt. It was not revealed until much later that two Bundestag members (Julius Steiner and Leo Wagner, both of the CDU/CSU) had been bribed by the East German Stasi

Stasi

The Ministry for State Security The Ministry for State Security The Ministry for State Security (German: Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (MfS), commonly known as the Stasi (abbreviation , literally State Security), was the official state security service of East Germany. The MfS was headquartered...

to vote for Brandt.

New elections

Though Brandt remained Chancellor, he had lost his majority. Subsequent initiatives in parliament, most notably on the budget, failed. Because of this stalemate, the Bundestag was dissolved and new elections were called. During the 1972 campaign, many popular West German artists, intellectuals, writers, actors and professors supported Brandt and the SPD. Among them were Günter GrassGünter Grass