Polyclonal B cell response

Encyclopedia

Adaptive immune system

The adaptive immune system is composed of highly specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate or prevent pathogenic growth. Thought to have arisen in the first jawed vertebrates, the adaptive or "specific" immune system is activated by the “non-specific” and evolutionarily older innate...

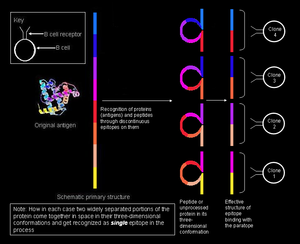

of mammals. It ensures that a single antigen

Antigen

An antigen is a foreign molecule that, when introduced into the body, triggers the production of an antibody by the immune system. The immune system will then kill or neutralize the antigen that is recognized as a foreign and potentially harmful invader. These invaders can be molecules such as...

is recognized and attacked through its overlapping parts, called epitope

Epitope

An epitope, also known as antigenic determinant, is the part of an antigen that is recognized by the immune system, specifically by antibodies, B cells, or T cells. The part of an antibody that recognizes the epitope is called a paratope...

s, by multiple clones

Clone (B-cell biology)

The process of immunological B-cell maturation involves transformation from an undifferentiated B cell to one that secretes antibodies with particular specificity...

of B cell

B cell

B cells are lymphocytes that play a large role in the humoral immune response . The principal functions of B cells are to make antibodies against antigens, perform the role of antigen-presenting cells and eventually develop into memory B cells after activation by antigen interaction...

.

In the course of normal immune response, parts of pathogen

Pathogen

A pathogen gignomai "I give birth to") or infectious agent — colloquially, a germ — is a microbe or microorganism such as a virus, bacterium, prion, or fungus that causes disease in its animal or plant host...

s (e.g. bacteria

Bacteria

Bacteria are a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria have a wide range of shapes, ranging from spheres to rods and spirals...

) are recognized by the immune system as foreign (non-self), and eliminated or effectively neutralized to reduce their potential damage. Such a recognizable substance is called an antigen

Antigen

An antigen is a foreign molecule that, when introduced into the body, triggers the production of an antibody by the immune system. The immune system will then kill or neutralize the antigen that is recognized as a foreign and potentially harmful invader. These invaders can be molecules such as...

. The immune system may respond in multiple ways to an antigen; a key feature of this response is the production of antibodies by B cells (or B lymphocytes) involving an arm of the immune system known as humoral immunity

Humoral immunity

The Humoral Immune Response is the aspect of immunity that is mediated by secreted antibodies produced in the cells of the B lymphocyte lineage . B Cells transform into plasma cells which secrete antibodies...

. The antibodies are soluble and do not require direct cell-to-cell contact between the pathogen and the B-cell to function.

Antigens can be large and complex substances, and any single antibody can only bind to a small, specific area on the antigen. Consequently, an effective immune response often involves the production of many different antibodies by many different B cells against the same antigen. Hence the term "polyclonal", which derives from the words poly, meaning many, and clones ("Klon"=Greek for sprout or twig); a clone is a group of cells arising from a common "mother" cell. The antibodies thus produced in a polyclonal response are known as polyclonal antibodies. The heterogeneous polyclonal antibodies are distinct from monoclonal antibody molecules, which are identical and react against a single epitope only, i.e., are more specific.

Although the polyclonal response confers advantages on the immune system, in particular, greater probability of reacting against pathogens, it also increases chances of developing certain autoimmune diseases resulting from the reaction of the immune system against native molecules produced within the host.

Humoral response to infection

Diseases which can be transmitted from one organism to another are known as infectious diseaseInfectious disease

Infectious diseases, also known as communicable diseases, contagious diseases or transmissible diseases comprise clinically evident illness resulting from the infection, presence and growth of pathogenic biological agents in an individual host organism...

s, and the causative biological agent involved is known as a pathogen

Pathogen

A pathogen gignomai "I give birth to") or infectious agent — colloquially, a germ — is a microbe or microorganism such as a virus, bacterium, prion, or fungus that causes disease in its animal or plant host...

. The process by which the pathogen is introduced into the body is known as inoculation

Inoculation

Inoculation is the placement of something that will grow or reproduce, and is most commonly used in respect of the introduction of a serum, vaccine, or antigenic substance into the body of a human or animal, especially to produce or boost immunity to a specific disease...

,The term "inoculation" is usually used in context of active immunization

Active immunization

Active immunization is the induction of immunity after exposure to an antigen. Antibodies are created by the recipient and may be stored permanently....

, i.e., deliberately introducing the antigenic substance into the host's body. But in many discussions of infectious diseases, it is not uncommon to use the term to imply a spontaneous (that is, without human intervention) event resulting in introduction of the causative organism into the body, say ingesting water contaminated with Salmonella typhi—the causative organism for typhoid fever

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

. In such cases the causative organism itself is known as the inoculum, and the number of organisms introduced as the "dose of inoculum". and the organism it affects is known as a biological host

Host (biology)

In biology, a host is an organism that harbors a parasite, or a mutual or commensal symbiont, typically providing nourishment and shelter. In botany, a host plant is one that supplies food resources and substrate for certain insects or other fauna...

. When the pathogen establishes itself in a step known as colonization

Colonisation

Colonization occurs whenever any one or more species populate an area. The term, which is derived from the Latin colere, "to inhabit, cultivate, frequent, practice, tend, guard, respect", originally related to humans. However, 19th century biogeographers dominated the term to describe the...

, it can result in an infection

Infection

An infection is the colonization of a host organism by parasite species. Infecting parasites seek to use the host's resources to reproduce, often resulting in disease...

, consequently harming the host directly or through the harmful substances called toxin

Toxin

A toxin is a poisonous substance produced within living cells or organisms; man-made substances created by artificial processes are thus excluded...

s it can produce. This results in the various symptom

Symptom

A symptom is a departure from normal function or feeling which is noticed by a patient, indicating the presence of disease or abnormality...

s and signs

Medical sign

A medical sign is an objective indication of some medical fact or characteristic that may be detected by a physician during a physical examination of a patient....

characteristic of an infectious disease like pneumonia

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung—especially affecting the microscopic air sacs —associated with fever, chest symptoms, and a lack of air space on a chest X-ray. Pneumonia is typically caused by an infection but there are a number of other causes...

or diphtheria

Diphtheria

Diphtheria is an upper respiratory tract illness caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, a facultative anaerobic, Gram-positive bacterium. It is characterized by sore throat, low fever, and an adherent membrane on the tonsils, pharynx, and/or nasal cavity...

.

Countering the various infectious diseases is very important for the survival of the susceptible organism, in particular, and the species, in general. This is achieved by the host by eliminating the pathogen and its toxins or rendering them nonfunctional. The collection of various cell

Cell (biology)

The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of all known living organisms. It is the smallest unit of life that is classified as a living thing, and is often called the building block of life. The Alberts text discusses how the "cellular building blocks" move to shape developing embryos....

s, tissue

Tissue (biology)

Tissue is a cellular organizational level intermediate between cells and a complete organism. A tissue is an ensemble of cells, not necessarily identical, but from the same origin, that together carry out a specific function. These are called tissues because of their identical functioning...

s and organ

Organ (anatomy)

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in structural unit to serve a common function. Usually there is a main tissue and sporadic tissues . The main tissue is the one that is unique for the specific organ. For example, main tissue in the heart is the myocardium, while sporadic are...

s that specializes in protecting the body against infections is known as the immune system

Immune system

An immune system is a system of biological structures and processes within an organism that protects against disease by identifying and killing pathogens and tumor cells. It detects a wide variety of agents, from viruses to parasitic worms, and needs to distinguish them from the organism's own...

. The immune system accomplishes this through direct contact of certain white blood cell

White blood cell

White blood cells, or leukocytes , are cells of the immune system involved in defending the body against both infectious disease and foreign materials. Five different and diverse types of leukocytes exist, but they are all produced and derived from a multipotent cell in the bone marrow known as a...

s with the invading pathogen involving an arm of the immune system known as the cell-mediated immunity

Cell-mediated immunity

Cell-mediated immunity is an immune response that does not involve antibodies but rather involves the activation of macrophages, natural killer cells , antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, and the release of various cytokines in response to an antigen...

, or by producing substances that move to sites distant from where they are produced, "seek" the disease-causing cells and toxins by specificallySpecificity implies that two different pathogens will be actually viewed as two distinct entities, and countered by different antibody molecules. binding with them, and neutralize them in the process–known as the humoral arm

Humoral immunity

The Humoral Immune Response is the aspect of immunity that is mediated by secreted antibodies produced in the cells of the B lymphocyte lineage . B Cells transform into plasma cells which secrete antibodies...

of the immune system. Such substances are known as soluble antibodies and perform important functions in countering infections.Actions of antibodies:

- Coating the pathogen, preventing it from adhering to the host cell, and thus preventing colonization

- Precipitating (making the particles "sink" by attaching to them) the soluble antigens and promoting their clearance by other cells of immune system from the various tissues and blood

- Coating the microorganisms to attract cells that can engulf the pathogen. This is known as opsonizationOpsoninAn opsonin is any molecule that targets an antigen for an immune response. However, the term is usually used in reference to molecules that act as a binding enhancer for the process of phagocytosis, especially antibodies, which coat the negatively-charged molecules on the membrane. Molecules that...

. Thus the antibody acts as an opsonin. The process of engulfing is known as phagocytosis (literally, cell eating) - Activating the complement systemComplement systemThe complement system helps or “complements” the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear pathogens from an organism. It is part of the immune system called the innate immune system that is not adaptable and does not change over the course of an individual's lifetime...

, which most importantly pokes holes into the pathogen's outer covering (its cell membraneCell membraneThe cell membrane or plasma membrane is a biological membrane that separates the interior of all cells from the outside environment. The cell membrane is selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules and controls the movement of substances in and out of cells. It basically protects the cell...

), killing it in the process - Marking up host cells infected by viruses for destruction in a process known as Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)

B cell response

T cell

T cells or T lymphocytes belong to a group of white blood cells known as lymphocytes, and play a central role in cell-mediated immunity. They can be distinguished from other lymphocytes, such as B cells and natural killer cells , by the presence of a T cell receptor on the cell surface. They are...

s (another type of white blood cell), which is a sequential procedure. The major steps involved are:

- Specific or nonspecific recognition of the pathogen (because of its antigens) with its subsequent engulfing by B cells or macrophageMacrophageMacrophages are cells produced by the differentiation of monocytes in tissues. Human macrophages are about in diameter. Monocytes and macrophages are phagocytes. Macrophages function in both non-specific defense as well as help initiate specific defense mechanisms of vertebrate animals...

s. This activates the B cell only partially. - Antigen processingAntigen processingAntigen processing is a biological process that prepares antigens for presentation to special cells of the immune system called T lymphocytes. This process involves two distinct pathways for processing of antigens from an organism's own proteins or intracellular pathogens , or from phagocytosed...

. - Antigen presentationAntigen presentationAntigen presentation is a process in the body's immune system by which macrophages, dendritic cells and other cell types capture antigens and then enable their recognition by T-cells....

. - Activation of the T helper cellT helper cellT helper cells are a sub-group of lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, that play an important role in the immune system, particularly in the adaptive immune system. These cells have no cytotoxic or phagocytic activity; they cannot kill infected host cells or pathogens. Rather, they help other...

s by antigen-presenting cellAntigen-presenting cellAn antigen-presenting cell or accessory cell is a cell that displays foreign antigen complexes with major histocompatibility complex on their surfaces. T-cells may recognize these complexes using their T-cell receptors...

s. - Costimulation of the B cell by activated T cell resulting in its complete activation.

- ProliferationCell growthThe term cell growth is used in the contexts of cell development and cell division . When used in the context of cell division, it refers to growth of cell populations, where one cell grows and divides to produce two "daughter cells"...

Proliferation in this context means multiplication by cell divisionCell divisionCell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two or more daughter cells . Cell division is usually a small segment of a larger cell cycle. This type of cell division in eukaryotes is known as mitosis, and leaves the daughter cell capable of dividing again. The corresponding sort...

and differentiationCellular differentiationIn developmental biology, cellular differentiation is the process by which a less specialized cell becomes a more specialized cell type. Differentiation occurs numerous times during the development of a multicellular organism as the organism changes from a simple zygote to a complex system of...

of B cells with resultant production of soluble antibodies.

Recognition of pathogens

Pathogens synthesize proteinProtein

Proteins are biochemical compounds consisting of one or more polypeptides typically folded into a globular or fibrous form, facilitating a biological function. A polypeptide is a single linear polymer chain of amino acids bonded together by peptide bonds between the carboxyl and amino groups of...

s that can serve as "recognizable

Molecular recognition

The term molecular recognition refers to the specific interaction between two or more molecules through noncovalent bonding such as hydrogen bonding, metal coordination, hydrophobic forces, van der Waals forces, π-π interactions, electrostatic and/or electromagnetic effects...

" antigens; they may express the molecules on their surface or release them into the surroundings (body fluids). What makes these substances recognizable is that they bind very specifically and somewhat strongly to certain host proteins called antibodies. The same antibodies can be anchored to the surface of cells of the immune system, in which case they serve as receptors

Immune receptor

An immune receptor is a receptor, usually on a cell membrane, which binds to a substance and causes a response in the immune system.-Types:...

, or they can be secreted in the blood, known as soluble antibodies. On a molecular scale, the proteins are relatively large, so they cannot be recognized as a whole; instead, their segments, called epitope

Epitope

An epitope, also known as antigenic determinant, is the part of an antigen that is recognized by the immune system, specifically by antibodies, B cells, or T cells. The part of an antibody that recognizes the epitope is called a paratope...

s, can be recognized. An epitope comes in contact with a very small region (of 15–22 amino acids) of the antibody molecule; this region is known as the paratope

Paratope

The paratope is the part of an antibody which recognises an antigen, the antigen-binding site of an antibody. It is a small region of the antibody's Fv region and contains parts of the antibody's heavy and light chains....

. In the immune system, membrane-bound antibodies are the B cell receptor (BCR). Also, while the T cell receptor is not biochemically classified as an antibody, it serves a similar function in that it specifically binds to epitopes complexed with major histocompatibility complex

Major histocompatibility complex

Major histocompatibility complex is a cell surface molecule encoded by a large gene family in all vertebrates. MHC molecules mediate interactions of leukocytes, also called white blood cells , which are immune cells, with other leukocytes or body cells...

(MHC) molecules.The major histocompatibility complex

Major histocompatibility complex

Major histocompatibility complex is a cell surface molecule encoded by a large gene family in all vertebrates. MHC molecules mediate interactions of leukocytes, also called white blood cells , which are immune cells, with other leukocytes or body cells...

is a gene region

Haplotype

A haplotype in genetics is a combination of alleles at adjacent locations on the chromosome that are transmitted together...

on the DNA

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

that codes for the synthesis of Major histocompatibility class I molecule, Major histocompatibility class II molecule and other proteins involved in the function of complement system

Complement system

The complement system helps or “complements” the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear pathogens from an organism. It is part of the immune system called the innate immune system that is not adaptable and does not change over the course of an individual's lifetime...

(MHC class III). The first two products are important in antigen presentation

Antigen presentation

Antigen presentation is a process in the body's immune system by which macrophages, dendritic cells and other cell types capture antigens and then enable their recognition by T-cells....

. MHC-compatibility is a major consideration in organ transplantation, and in humans is also known as the human leukocyte antigen

Human leukocyte antigen

The human leukocyte antigen system is the name of the major histocompatibility complex in humans. The super locus contains a large number of genes related to immune system function in humans. This group of genes resides on chromosome 6, and encodes cell-surface antigen-presenting proteins and...

(HLA). The binding between a paratope and its corresponding antigen is very specific, owing to its structure, and is guided by various noncovalent bonds

Noncovalent bonding

A noncovalent bond is a type of chemical bond, typically between macromolecules, that does not involve the sharing of pairs of electrons, but rather involves more dispersed variations of electromagnetic interactions. The noncovalent bond is the dominant type of bond between supermolecules in...

, not unlike the pairing of other types of ligands

Ligand (biochemistry)

In biochemistry and pharmacology, a ligand is a substance that forms a complex with a biomolecule to serve a biological purpose. In a narrower sense, it is a signal triggering molecule, binding to a site on a target protein.The binding occurs by intermolecular forces, such as ionic bonds, hydrogen...

(any atom, ion or molecule that binds with any receptor with at least some degree of specificity and strength). The specificity of binding does not arise out of a rigid lock and key type of interaction, but rather requires both the paratope and the epitope to undergo slight conformational changes in each other's presence.

Specific recognition of epitope by B cells

Linear epitope

A linear or a sequential epitope is an epitope that is recognized by antibodies by its linear sequence of amino acids, or primary structure. In contrast, most antibodies recognize a conformational epitope that has a specific three-dimensional shape and its protein structure.An antigen is any...

s, as all the amino acids on them are in the same sequence (line). This mode of recognition is possible only when the peptide is small (about six to eight amino acids long), and is employed by the T cells (T lymphocytes).

However, the B memory/naive cells recognize intact proteins present on the pathogen surface. Here, intact implies that the undigested protein is recognized, and not that the paratope on B cell receptor comes in contact with the whole protein structure at the same time; the paratope will still contact only a restricted portion of the antigen exposed on its surface. In this situation, the protein in its tertiary structure is so greatly folded that some loops of amino acids come to lie in the interior of the protein, and the segments that flank them may lie on the surface. The paratope on the B cell receptor comes in contact only with those amino acids that lie on the surface of the protein. The surface amino acids may actually be discontinuous in the protein's primary structure, but get juxtaposed owing to the complex protein folding patterns (as in the adjoining figure). Such epitopes are known as conformational epitopes and tend to be longer (15–22 amino acid residues) than the linear epitopes. Likewise, the antibodies produced by the plasma cells belonging to the same clone would bind to the same conformational epitopes on the pathogen proteins.

The binding of a specific antigen with corresponding BCR molecules results in increased production of the MHC-II molecules. This assumes significance as the same does not happen when the same antigen would be internalized by a relatively nonspecific process called pinocytosis

Pinocytosis

In cellular biology, pinocytosis is a form of endocytosis in which small particles are brought into the cell—forming an invagination, and then suspended within small vesicles that subsequently fuse with lysosomes to hydrolyze, or to break down, the particles...

, in which the antigen with the surrounding fluid is "drunk" as a small vesicle by the B cell. Hence, such an antigen is known as a nonspecific antigen and does not lead to activation of the B cell, or subsequent production of antibodies against it.

Nonspecific recognition by macrophages

Macrophages and related cells employ a different mechanism to recognize the pathogen. Their receptors recognize certain motifs present on the invading pathogen that are very unlikely to be present on a host cell. Such repeating motifs are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) like the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) expressed by the macrophages. Since the same receptor could bind to a given motif present on surfaces of widely disparate microorganismMicroorganism

A microorganism or microbe is a microscopic organism that comprises either a single cell , cell clusters, or no cell at all...

s, this mode of recognition is relatively nonspecific, and constitutes an innate immune response

Innate immune system

The innate immune system, also known as non-specific immune system and secondary line of defence, comprises the cells and mechanisms that defend the host from infection by other organisms in a non-specific manner...

.

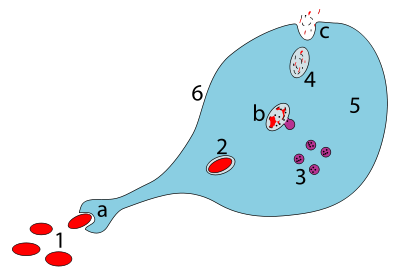

Antigen processing

Macrophage

Macrophages are cells produced by the differentiation of monocytes in tissues. Human macrophages are about in diameter. Monocytes and macrophages are phagocytes. Macrophages function in both non-specific defense as well as help initiate specific defense mechanisms of vertebrate animals...

or B lymphocyte engulfs it completely by a process called phagocytosis. The engulfed particle, along with some material surrounding it, forms the endocytic vesicle (the phagosome

Phagosome

In cell biology, a phagosome is a vacuole formed around a particle absorbed by phagocytosis. The vacuole is formed by the fusion of the cell membrane around the particle. A phagosome is a cellular compartment in which pathogenic microorganisms can be killed and digested...

), which fuses with lysosomes. Within the lysosome, the antigen is broken down into smaller pieces called peptides by protease

Protease

A protease is any enzyme that conducts proteolysis, that is, begins protein catabolism by hydrolysis of the peptide bonds that link amino acids together in the polypeptide chain forming the protein....

s (enzyme

Enzyme

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. In enzymatic reactions, the molecules at the beginning of the process, called substrates, are converted into different molecules, called products. Almost all chemical reactions in a biological cell need enzymes in order to occur at rates...

s that degrade larger proteins). The individual peptides are then complexed with major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC class II

MHC class II

MHC Class II molecules are found only on a few specialized cell types, including macrophages, dendritic cells and B cells, all of which are professional antigen-presenting cells ....

) molecules located in the lysosome – this method of "handling" the antigen is known as the exogenous or endocytic pathway of antigen processing in contrast to the endogenous or cytosolic pathway, which complexes the abnormal proteins produced within the cell (e.g. under the influence of a viral infection

Virus

A virus is a small infectious agent that can replicate only inside the living cells of organisms. Viruses infect all types of organisms, from animals and plants to bacteria and archaea...

or in a tumor

Tumor

A tumor or tumour is commonly used as a synonym for a neoplasm that appears enlarged in size. Tumor is not synonymous with cancer...

cell) with MHC class I

MHC class I

MHC class I molecules are one of two primary classes of major histocompatibility complex molecules and are found on every nucleated cell of the body...

molecules.

An alternate pathway of endocytic processing had also been demonstrated wherein certain proteins like fibrinogen

Fibrinogen

Fibrinogen is a soluble plasma glycoprotein, synthesised by the liver, that is converted by thrombin into fibrin during blood coagulation. This is achieved through processes in the coagulation cascade that activate the zymogen prothrombin to the serine protease thrombin, which is responsible for...

and myoglobin

Myoglobin

Myoglobin is an iron- and oxygen-binding protein found in the muscle tissue of vertebrates in general and in almost all mammals. It is related to hemoglobin, which is the iron- and oxygen-binding protein in blood, specifically in the red blood cells. The only time myoglobin is found in the...

can bind as a whole to MHC-II molecules after they are denatured

Denaturation (biochemistry)

Denaturation is a process in which proteins or nucleic acids lose their tertiary structure and secondary structure by application of some external stress or compound, such as a strong acid or base, a concentrated inorganic salt, an organic solvent , or heat...

and their disulfide bond

Disulfide bond

In chemistry, a disulfide bond is a covalent bond, usually derived by the coupling of two thiol groups. The linkage is also called an SS-bond or disulfide bridge. The overall connectivity is therefore R-S-S-R. The terminology is widely used in biochemistry...

s are reduced

Redox

Redox reactions describe all chemical reactions in which atoms have their oxidation state changed....

(breaking the bond by adding hydrogen

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with atomic number 1. It is represented by the symbol H. With an average atomic weight of , hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant chemical element, constituting roughly 75% of the Universe's chemical elemental mass. Stars in the main sequence are mainly...

atom

Atom

The atom is a basic unit of matter that consists of a dense central nucleus surrounded by a cloud of negatively charged electrons. The atomic nucleus contains a mix of positively charged protons and electrically neutral neutrons...

s across it). The proteases then degrade the exposed regions of the protein-MHC II-complex.

Antigen presentation

After the processed antigen (peptide) is complexed to the MHC molecule, they both migrate together to the cell membraneCell membrane

The cell membrane or plasma membrane is a biological membrane that separates the interior of all cells from the outside environment. The cell membrane is selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules and controls the movement of substances in and out of cells. It basically protects the cell...

, where they are exhibited (elaborated) as a complex that can be recognized by the CD 4+ (T helper cell)

T helper cell

T helper cells are a sub-group of lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, that play an important role in the immune system, particularly in the adaptive immune system. These cells have no cytotoxic or phagocytic activity; they cannot kill infected host cells or pathogens. Rather, they help other...

– a type of white blood cell.There are many types of white blood cells. The common way of classifying them is according to their appearance under the light microscope after they are stained by chemical dyes. But with advancing technology newer methods of classification has emerged. One of the methods employs the use of monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are monospecific antibodies that are the same because they are made by identical immune cells that are all clones of a unique parent cell....

, which can bind specifically to each type of cell. Moreover, the same type of white blood cell would express molecules typical to it on its cell membrane at various stages of development. The monoclonal antibodies that can specifically bind with a particular surface molecule would be regarded as one cluster of differentiation

Cluster of differentiation

The cluster of differentiation is a protocol used for the identification and investigation of cell surface molecules present on white blood cells, providing targets for immunophenotyping of cells...

(CD). Any monoclonal antibody or group of monoclonal antibodies that does not react with known surface molecules of lymphocytes, but rather to a yet-unrecognized surface molecule would be clubbed as a new cluster of differentiation and numbered accordingly. Each cluster of differentiation is abbreviated as "CD", and followed by a number (usually indicating the order of discovery). So, a cell possessing a surface molecule (called ligand

Ligand (biochemistry)

In biochemistry and pharmacology, a ligand is a substance that forms a complex with a biomolecule to serve a biological purpose. In a narrower sense, it is a signal triggering molecule, binding to a site on a target protein.The binding occurs by intermolecular forces, such as ionic bonds, hydrogen...

) that binds specifically to cluster of differentiation 4 would be known as CD4+ cell. Likewise, a CD8+ cell is one that would possess the CD8 ligand and bind to CD8 monoclonal antibodies. This is known as antigen presentation. However, the epitopes (conformational epitopes) that are recognized by the B cell prior to their digestion may not be the same as that presented to the T helper cell. Additionally, a B cell may present different peptides complexed to different MHC-II molecules.

T helper cell stimulation

The CD 4+ cells through their T cell receptor-CD3 complex recognize the epitope-bound MHC II molecules on the surface of the antigen presenting cells, and get 'activated'Immunologic activation

In immunology, activation is the transition of leucocytes and other cell types involved in the immune system. On the other hand, deactivation is the transition in the reverse direction...

. Upon this activation, these T cells proliferate and differentiate into Th2 cells. This makes them produce soluble chemical signals that promote their own survival. However, another important function that they carry out is the stimulation of B cell by establishing direct physical contact with them.

Costimulation of B cell by activated T helper cell

Complete stimulation of T helper cells requires the B7B7 (protein)

B7 is a type of peripheral membrane protein found on activated antigen presenting cells that, when paired with either a CD28 or CD152 surface protein on a T cell, can produce a costimulatory signal to enhance or decrease the activity of a MHC-TCR signal between the APC and the T cell, respectively...

molecule present on the antigen presenting cell to bind with CD28

CD28

CD28 is one of the molecules expressed on T cells that provide co-stimulatory signals, which are required for T cell activation. CD28 is the receptor for CD80 and CD86 . When activated by Toll-like receptor ligands, the CD80 expression is upregulated in antigen presenting cells...

molecule present on the T cell surface (in close proximity with the T cell receptor). Likewise, a second interaction between the CD40 ligand or CD154 (CD40L) present on T cell surface and CD40 present on B cell surface, is also necessary. The same interactions that stimulate the T helper cell also stimulate the B cell, hence the term costimulation. The entire mechanism ensures that an activated T cell only stimulates a B cell that recognizes the antigen containing the same epitope as recognized by the T cell receptor of the "costimulating" T helper cell. The B cell gets stimulated, apart from the direct costimulation, by certain growth factors, viz., interleukins 2, 4, 5, and 6 in a paracrine

Paracrine signalling

Paracrine signalling is a form of cell signalling in which the target cell is near the signal-releasing cell.-Local action:Some signalling molecules degrade very quickly, limiting the scope of their effectiveness to the immediate surroundings...

fashion. These factors are usually produced by the newly activated T helper cell. However, this activation occurs only after the B cell receptor present on a memory

Memory B cell

Memory B cells are a B cell sub-type that are formed following primary infection.-Primary response, paratopes, and epitopes:In wake of first infection involving a particular antigen, the responding naïve cells proliferate to produce a colony of cells, most of which differentiate into the plasma...

or a naive B cell itself would have bound to the corresponding epitope, without which the initiating steps of phagocytosis and antigen processing would not have occurred.

Proliferation and differentiation of B cell

A naive (or inexperienced) B cell is one which belongs to a clone which has never encountered the epitope to which it is specific. In contrast, a memory B cell is one which derives from an activated naive or memory B cell. The activation of a naive or a memory B cell is followed by a manifold proliferation of that particular B cell, most of the progeny of which terminally differentiate into plasma B cells;The plasma cells secrete antibodies that bind to the same structure that had stimulated the B cell in the first place by binding to its B cell receptor. the rest survive as memory B cells. So, when the naive cells belonging to a particular clone encounter their specific antigen to give rise to the plasma cells, and also leave a few memory cells, this is known as the primary immune response. In the course of proliferation of this clone, the B cell receptor geneGene

A gene is a molecular unit of heredity of a living organism. It is a name given to some stretches of DNA and RNA that code for a type of protein or for an RNA chain that has a function in the organism. Living beings depend on genes, as they specify all proteins and functional RNA chains...

s can undergo frequent (one in every two cell divisions) mutation

Mutation

In molecular biology and genetics, mutations are changes in a genomic sequence: the DNA sequence of a cell's genome or the DNA or RNA sequence of a virus. They can be defined as sudden and spontaneous changes in the cell. Mutations are caused by radiation, viruses, transposons and mutagenic...

s in the genes coding for paratopes of antibodies. These frequent mutations are termed somatic hypermutation

Somatic hypermutation

Somatic hypermutation is a mechanism inside cells that is part of the way the immune system adapts to the new foreign elements that confront it . SHM diversifies the receptors used by the immune system to recognize foreign elements and allows the immune system to adapt its response to new threats...

. Each such mutation alters the epitope-binding ability of the paratope slightly, creating new clones of B cells in the process. Some of the newly created paratopes bind more strongly to the same epitope (leading to the selection

Clonal selection

The clonal selection hypothesis has become a widely accepted model for how the immune system responds to infection and how certain types of B and T lymphocytes are selected for destruction of specific antigens invading the body....

of the clones possessing them), which is known as affinity maturation

Affinity maturation

In immunology, affinity maturation is the process by which B cells produce antibodies with increased affinity for antigen during the course of an immune response. With repeated exposures to the same antigen, a host will produce antibodies of successively greater affinities. A secondary response...

.Affinity roughly translates as attraction from Latin. See also: Definition of Affinity from Online Etymology Dictionary and Definition of Affinity from TheFreeDictionary by Farlex Other paratopes bind better to epitopes that are slightly different from the original epitope that had stimulated proliferation. Variations in the epitope structure are also usually produced by mutations in the genes of pathogen coding for their antigen. Somatic hypermutation, thus, makes the B cell receptors and the soluble antibodies in subsequent encounters with antigens, more inclusive in their antigen recognition potential of altered epitopes, apart from bestowing greater specificity for the antigen that induced proliferation in the first place. When the memory cells get stimulated by the antigen to produce plasma cells (just like in the clone's primary response), and leave even more memory cells in the process, this is known as a secondary immune response, which translates into greater numbers of plasma cells and faster rate of antibody production lasting for longer periods. The memory B cells produced as a part of secondary response recognize the corresponding antigen faster and bind more strongly with it (i.e., greater affinity of binding) owing to affinity maturation. The soluble antibodies produced by the clone show a similar enhancement in antigen binding.

Basis of polyclonality

Responses are polyclonal in nature as each clone somewhat specializes in producing antibodies against a given epitope, and because, each antigen contains multiple epitopes, each of which in turn can be recognized by more than one clone of B cells. But, to be able to react to innumerable antigens, as well as, multiple constituent epitopes, the immune system requires the ability to recognize a very great number of epitopes in all, i.e., there should be a great diversity of B cell clones.Clonality of B cells

MemoryMemory B cell

Memory B cells are a B cell sub-type that are formed following primary infection.-Primary response, paratopes, and epitopes:In wake of first infection involving a particular antigen, the responding naïve cells proliferate to produce a colony of cells, most of which differentiate into the plasma...

and naïve B cells normally exist in relatively small numbers. As the body needs to be able to respond to a large number of potential pathogens, it maintains a pool of B cells with a wide range of specificities. Consequently, while there is almost always at least one B (naive or memory) cell capable of responding to any given epitope (of all that the immune system can react against), there are very few exact duplicates. However, when a single B cell encounters an antigen to which it can bind, it can proliferate very rapidly. Such a group of cells with identical specificity towards the epitope is known as a clone

Clone (cell biology)

A clone is a group of identical cells that share a common ancestry, meaning they are derived from the same mother cell.Clonality implies the state of a cell or a substance being derived from one source or the other...

, and is derived from a common "mother" cell. All the "daughter" B cells match the original "mother" cell in their epitope specificity, and they secrete antibodies with identical paratopes. So, in this context, a polyclonal response is one in which multiple clones of B cells react to the same antigen.

Single antigen contains multiple overlapping epitopes

Multiple clones recognize single epitope

In addition to different B cells reacting to different epitopes on the same antigen, B cells belonging to different clones may also be able to react to the same epitope. An epitope that can be attacked by many different B cells is said to be highly immunogenic. In these cases, the binding affinities for respective epitope-paratope pairs vary, with some B cell clones producing antibodies that bind strongly to the epitope, and others producing antibodies that bind weakly.Clonal selection

The clones that bind to a particular epitope with greater strength are more likely to be selectedClonal selection

The clonal selection hypothesis has become a widely accepted model for how the immune system responds to infection and how certain types of B and T lymphocytes are selected for destruction of specific antigens invading the body....

for further proliferation in the germinal centers of the follicles in various lymphoid tissues like the lymph nodes. This is not unlike natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

: clones are selected for their fitness to attack the epitopes (strength of binding) on the encountered pathogen.

What makes the analogy even stronger is that the B lymphocytes have to compete with each other for signals that promote their survival in the germinal centers.

Diversity of B cell clones

Although there are many diverse pathogens, many of which are constantly mutating, it is a surprise that a majority of individuals remain free of infections. Thus, maintenance of health requires the body to recognize all pathogens (antigens they present or produce) likely to exist. This is achieved by maintaining a pool of immensely large (about 109) clones of B cells, each of which reacts against a specific epitope by recognizing and producing antibodies against it. However, at any given time very few clones actually remain receptive to their specific epitope. Thus, approximately 107 different epitopes can be recognized by all the B cell clones combined. Moreover, in a lifetime, an individual usually requires the generation of antibodies against very few antigens in comparison with the number that the body can recognize and respond against.Increased probability of recognizing any antigen

If an antigen can be recognized by more than one component of its structure, it is less likely to be "missed" by the immune system.Analogically, if in a crowded place, one is supposed to recognize a person, it is better to know as many physical features as possible. If you know the person only by the hairstyle, there is a chance of overlooking the person if that changes. Whereas, if apart from the hairstyle, if you also happen to know the facial features and what the person will wear on a particular day, it becomes much more unlikely that you will miss that person. Mutation of pathogenic organisms can result in modification of antigen—and, hence, epitope—structure. If the immune system "remembers" what the other epitopes look like, the antigen, and the organism, will still be recognized and subjected to the body's immune response. Thus, the polyclonal response widens the range of pathogens that can be recognized.Limitation of immune system against rapidly mutating viruses

Many viruses undergo frequent mutationMutation

In molecular biology and genetics, mutations are changes in a genomic sequence: the DNA sequence of a cell's genome or the DNA or RNA sequence of a virus. They can be defined as sudden and spontaneous changes in the cell. Mutations are caused by radiation, viruses, transposons and mutagenic...

s that result in changes in amino acid composition of their important proteins. Epitopes located on the protein may also undergo alterations in the process. Such an altered epitope binds less strongly with the antibodies specific to the unaltered epitope that would have stimulated the immune system. This is unfortunate because somatic hypermutation does give rise to clones capable of producing soluble antibodies that would have bound the altered epitope avidly enough to neutralize it. But these clones would consist of naive cells which are not allowed to proliferate by the weakly binding antibodies produced by the priorly stimulated clone. This doctrine is known as the original antigenic sin

Original antigenic sin

Original antigenic sin, also known as the Hoskins effect, refers to the propensity of the body's immune system to preferentially utilize immunological memory based on a previous infection when a second slightly different version, of that foreign entity is encountered...

. This phenomenon comes into play particularly in immune responses against influenza

Orthomyxoviridae

The Orthomyxoviridae are a family of RNA viruses that includes five genera: Influenzavirus A, Influenzavirus B, Influenzavirus C, Isavirus and Thogotovirus. A sixth has recently been described...

, dengue

Dengue fever

Dengue fever , also known as breakbone fever, is an infectious tropical disease caused by the dengue virus. Symptoms include fever, headache, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin rash that is similar to measles...

and HIV

HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus is a lentivirus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome , a condition in humans in which progressive failure of the immune system allows life-threatening opportunistic infections and cancers to thrive...

viruses. This limitation, however, is not imposed by the phenomenon of polyclonal response, but rather, against it by an immune response that is biased in favor of experienced memory cells against the "novice" naive cells.

Increased chances of autoimmune reactions

In autoimmunityAutoimmunity

Autoimmunity is the failure of an organism to recognize its own constituent parts as self, which allows an immune response against its own cells and tissues. Any disease that results from such an aberrant immune response is termed an autoimmune disease...

the immune system wrongly recognizes certain native molecules in the body as foreign (self-antigen), and mounts an immune response against them. Since these native molecules, as normal parts of the body, will naturally always exist in the body, the attacks against them can get stronger over time (akin to secondary immune response). Moreover, many organisms exhibit molecular mimicry

Molecular mimicry

Molecular mimicry is defined as the theoretical possibility that sequence similarities between foreign and self-peptides are sufficient to result in the cross-activation of autoreactive T or B cells by pathogen-derived peptides...

, which involves showing those antigens on their surface that are antigenically similar to the host proteins. This has two possible consequences: first, either the organism will be spared as a self antigen; or secondly, that the antibodies produced against it will also bind to the mimicked native proteins. The antibodies will attack the self-antigens and the tissues harboring them by activating various mechanisms like the complement activation and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Hence, wider the range of antibody-specificities, greater the chance that one or the other will react against self-antigens (native molecules of the body).

Difficulty in producing monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodiesMonoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are monospecific antibodies that are the same because they are made by identical immune cells that are all clones of a unique parent cell....

are structurally identical immunoglobulin molecules with identical epitope-specificity (all of them bind with the same epitope with same affinity) as against their polyclonal counterparts which have varying affinities for the same epitope.

They are usually not produced in a natural immune response, but only in diseased states like multiple myeloma

Multiple myeloma

Multiple myeloma , also known as plasma cell myeloma or Kahler's disease , is a cancer of plasma cells, a type of white blood cell normally responsible for the production of antibodies...

, or through specialized laboratory techniques. Because of their specificity, monoclonal antibodies are used in certain applications to quantify or detect the presence of substances (which act as antigen for the monoclonal antibodies), and for targeting individual cells (e.g. cancer cells). Monoclonal antibodies find use in various diagnostic modalities (see: western blot

Western blot

The western blot is a widely used analytical technique used to detect specific proteins in the given sample of tissue homogenate or extract. It uses gel electrophoresis to separate native proteins by 3-D structure or denatured proteins by the length of the polypeptide...

and immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence is a technique used for light microscopy with a fluorescence microscope and is used primarily on biological samples. This technique uses the specificity of antibodies to their antigen to target fluorescent dyes to specific biomolecule targets within a cell, and therefore allows...

) and therapies

Monoclonal antibody therapy

Monoclonal antibody therapy is the use of monoclonal antibodies to specifically bind to target cells or proteins. This may then stimulate the patient's immune system to attack those cells...

—particularly of cancer and diseases with autoimmune component. But, since virtually all responses in nature are polyclonal, it makes production of immensely useful monoclonal antibodies less straightforward.

History

Kitasato Shibasaburō

Baron was a Japanese physician and bacteriologist. He is remembered as the co-discoverer of the infectious agent of bubonic plague in Hong Kong in 1894, almost simultaneously with Alexandre Yersin.-Biography:...

in 1890 developed effective serum against diphtheria. This they did by transferring serum produced from animals immunized against diphtheria to animals suffering from it. Transferring the serum thus could cure the infected animals. Behring was awarded the Nobel Prize

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes are annual international awards bestowed by Scandinavian committees in recognition of cultural and scientific advances. The will of the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the prizes in 1895...

for this work in 1901.

At this time though the chemical nature of what exactly in the blood conferred this protection was not known. In a few decades to follow it could be shown that the protective serum could neutralize and precipitate toxins, and clump bacteria. All these functions were attributed to different substances in the serum, and named accordingly as antitoxin, precipitin and agglutinin. That all the three substances were one entity (gamma globulin

Gamma globulin

Gamma globulins are a class of globulins, identified by their position after serum protein electrophoresis. The most significant gamma globulins are immunoglobulins , more commonly known as antibodies, although some Igs are not gamma globulins, and some gamma globulins are not Igs.-Use as medical...

s) was demonstrated by Elvin A. Kabat

Elvin A. Kabat

Elvin Abraham Kabat was an Americanbiomedical scientist who is considered one of the founding fathers of modern quantitative immunochemistry together with his mentor Michael Heidelberger...

in 1939. In the preceding year itself Kabat had demonstrated amazing heterogeneity of antibodies through ultracentrifugation studies of horses' sera.

Until this time cell-mediated immunity and humoral immunity were considered to be contending theories to explain effective immune response, but the former lagged behind owing to lack of advanced techniques. Cell-mediated immunity got an impetus in its recognition and study when in 1942, Merrill Chase

Merrill Chase

Merrill W. Chase was an immunologist working at the Rockefeller University in New York City who is credited with discovering cell-mediated immunology in the early 1940s. While working with Dr. Karl Landsteiner, Dr. Chase discovered that white blood cells, and not antibodies alone, were important...

successfully transferred immunity against tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

between pigs by transferring white blood cells.

It was later shown in 1948 by Astrid Fagraeus in her doctoral thesis that the plasma B cells are specifically involved in antibody production. The role of lymphocytes in mediating both cell-mediated and humoral responses was demonstrated by James Gowans in 1959.

In order to account for the wide range of antigens the immune system can recognize, Paul Ehrlich

Paul Ehrlich

Paul Ehrlich was a German scientist in the fields of hematology, immunology, and chemotherapy, and Nobel laureate. He is noted for curing syphilis and for his research in autoimmunity, calling it "horror autotoxicus"...

in 1900 had hypothesized that preexisting "side chain receptors" bind a given pathogen, and that this interaction induces the cell exhibiting the receptor to multiply and produce more copies of the same receptor. This theory, called the selective theory was not proven for next five decades, and had been challenged by several instructional theories which were based on the notion that an antibody would assume its effective structure by folding around the antigen. In the late 1950s however, the works of three scientists—Jerne

Niels Kaj Jerne

Niels Kaj Jerne, FRS was a Danish immunologist. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1984. The citation read "For theories concerning the specificity in development and control of the immune system and the discovery of the principle for production of monoclonal antibodies"....

, Talmage

David Talmage

David W. Talmage is an American immunologist. He made significant contributions to the clonal selection theory.-Career:Talmage received his MD from Washington University in St. Louis in 1944. From 1959 he was Professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Professor of microbiology from 1960...

and Burnet

Frank Macfarlane Burnet

Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, , usually known as Macfarlane or Mac Burnet, was an Australian virologist best known for his contributions to immunology....

(who largely modified the theory) gave rise to the clonal selection theory, which proved all the elements of Ehrlich's hypothesis except that the specific receptors that could neutralize the agent were soluble and not membrane-bound.

The clonal selection theory was proved to be correct when Sir Gustav Nossal

Gustav Nossal

Sir Gustav Victor Joseph Nossal, AC, CBE, FRS, FAA is an Australian research biologist.-Life and career:Gustav Nossal's family was from Vienna, Austria. He was born four weeks prematurely in Bad Ischl while his mother was on holiday...

showed that one clone of B cell always produces only one antibody.

Subsequently the role of MHC in antigen presentation was demonstrated by Rolf Zinkernagel and Peter C. Doherty in 1974.

See also

- Polyclonal antibodies

- Antigen processingAntigen processingAntigen processing is a biological process that prepares antigens for presentation to special cells of the immune system called T lymphocytes. This process involves two distinct pathways for processing of antigens from an organism's own proteins or intracellular pathogens , or from phagocytosed...

- AntiserumAntiserumAntiserum is blood serum containing polyclonal antibodies. Antiserum is used to pass on passive immunity to many diseases. Passive antibody transfusion from a previous human survivor is the only known effective treatment for Ebola infection .The most common use of antiserum in humans is as...

, a polyclonal antibody preparation used to treat envenomation