.gif)

History of the United States (1964–1980)

Encyclopedia

The history of the United States from 1964 through 1980 includes the climax and collapse of the African American Civil Rights Movement

; the escalation and ending of the Vietnam War

; the drama of a generational revolt with its sexual freedoms and use of drugs; and the continuation of the Cold War

, with its Space Race

to put a man on the Moon. The economy was prosperous until the early 1970s, then faltered under new foreign competition and high oil prices. By 1980 and the seizure of the American Embassy in Iran, there was a growing sense of national malaise. This period is closed by the victory of conservative Republican Ronald Reagan

, opening the "Age of Reagan" with a dramatic change in national direction.

Memories of the 1960s shaped the political landscape for the next half-century. As Bill Clinton

explained in 2004, "If you look back on the Sixties and think there was more good than bad, you're probably a Democrat

. If you think there was more harm than good, you're probably a Republican

."

(1963–69) in securing congressional passage of his Great Society

programs, including civil rights, the end of segregation, Medicare, extension of welfare, federal aid to education at all levels, subsidies for the arts and humanities, environmental activism, and a series of programs designed to wipe out poverty. As recent historians have explained:

Johnson was rewarded with an electoral landslide in 1964 against conservative Barry Goldwater

, which broke the decades-long control of Congress by the Conservative coalition

. But the Republicans bounced back in 1966, and Republicans elected Richard Nixon

in 1968. Nixon largely continued the New Deal and Great Society programs he inherited; conservative reaction would come with the election of Ronald Reagan

in 1980.

with street protests led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as well as the NAACP

. King skillfully used the media to record instances of brutality against non-violent African-American protesters to tug at the conscience of the public. Activism brought about successful political change when there was an aggrieved group, such as African-Americans or feminists or homosexuals, who felt the sting of bad policy over time, and who conducted long-range campaigns of protest together with media campaigns to change public opinion along with campaigns in the courts to change policy.

The assassination of Kennedy

in 1963 helped change the political mood of the country. The new President

, Lyndon B. Johnson

, capitalized on this situation, using a combination of the national mood and his own political savvy to push Kennedy's agenda; most notably, the Civil Rights Act of 1964

.

In addition, the 1965 Voting Rights Act

had an immediate impact on federal, state and local elections. Within months of its passage on August 6, 1965, one quarter of a million new black voters had been registered, one third by federal examiners. Within four years, voter registration in the South

had more than doubled. In 1965, Mississippi

had the highest black voter turnout, 74%, and had more elected black-leaders than any other state. In 1969, Tennessee

had a 92.1% voter turnout, Arkansas

77.9%, and Texas

77.3%.

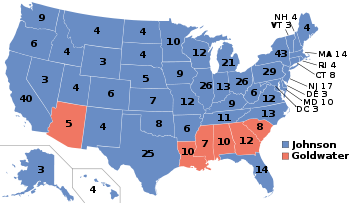

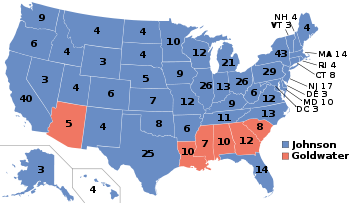

In the election of 1964, Lyndon Johnson positioned himself as a moderate, contrasting himself against his GOP

In the election of 1964, Lyndon Johnson positioned himself as a moderate, contrasting himself against his GOP

opponent, Barry Goldwater

, who the campaign characterized as hardline right-wing. Most famously, the Johnson campaign ran a commercial entitled the "Daisy Girl" ad, which featured a little girl picking petals from a daisy in a field, counting the petals, which then segues into a launch countdown and a nuclear explosion

. Johnson soundly defeated Goldwater in the general election, winning 64.9% of the popular vote, and losing only five states in the Deep South, where blacks were not yet allowed to vote, along with Goldwater's Arizona.

Goldwater's race energized the conservative movement, chiefly inside the Republican party. It looked for a new leader and found one in Ronald Reagan

, elected governor of California in 1966 and reelected in 1970. He ran against President Ford for the 1976 GOP nomination, and narrowly lost, but the stage was set for Reagan in 1980.

domestic agenda of Franklin D. Roosevelt

in the 1930s, but differed sharply in types of programs enacted.

The largest and most enduring federal assistance programs, launched in 1965, were Medicare

, which pays for many of the medical costs of the elderly, and Medicaid

, which aids poor people.

The centerpiece of the War on Poverty

was the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964

, which created an Office of Economic Opportunity

(OEO) to oversee a variety of community-based antipoverty programs. The OEO reflected a fragile consensus among policymakers that the best way to deal with poverty was not simply to raise the incomes of the poor but to help them better themselves through education, job training, and community development. Central to its mission was the idea of "community action

", the participation of the poor in framing and administering the programs designed to help them.

and Cold War

. A social revolution swept through the country to create a more liberated society. As the Civil Rights Movement progressed, feminism

and environmentalism

movements soon grew in the midst of a Sexual Revolution

with its distinctive protest forms, from long hair to rock music. The Hippie

culture, which emphasized peace, love and freedom, was introduced to the mainstream. In 1967, the Summer of Love

, an event in San Francisco where thousands of young people loosely and freely united for a new social experience, helped introduce much of the world to the culture. In addition, the increase use of psychedelic drugs, such as LSD

and marijuana

, also became central to the movement. Music of the time also played a large role with the introduction of folk rock

and later Acid Rock

and Psychedelia which became the voice of the generation. The Counterculture Revolution was exemplified in 1969 with the historic Woodstock Festival

..

Beginning with the Soviet launch of the first satellite, Sputnik 1

Beginning with the Soviet launch of the first satellite, Sputnik 1

, in 1957, the United States competed with the Soviet Union for supremacy in outer space exploration. After the Soviets placed the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin

, in 1961, President John F. Kennedy

pushed for ways in which NASA

could catch up, famously urging action a manned mission to the Moon

: "I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth." The first manned flights produced by this effort came from Project Gemini

(1965–1966) and then by the Apollo program, which despite the tragic loss of the Apollo 1

crew, achieved Kennedy's goal by landing the first astronauts on the Moon with the Apollo 11

mission in 1969.

Having lost the race to the Moon, the Soviets shifted their attention to orbital space station

s, launching the first (Salyut 1

) in 1971. The U.S. responded with the Skylab

orbital workstation, in use from 1973 through 1974. With détente, a time of relatively improved Cold War relations between the United States and the Soviets, the two superpowers developed a cooperative space mission: the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project. This 1975 joint mission was the last manned space flight for the U.S. until the Space Shuttle

flights of 1981 and has been described as the symbolic end of the Space Race. The Space Race sparked unprecedented increases in spending on education and pure research, which accelerated scientific advancements and led to beneficial spin-off technologies.

policy meant fighting communist expansion where ever it occurred, and the Communist picked where the American allies were weakest. Johnson's primary commitment was to his domestic policy, so he tried to minimize public awareness and congressional oversight of the operations in the war. Most of his advisers were pessimistic about the long run possibilities, and Johnson feared that if Congress took control, it would demand "Why Not Victory", as Barry Goldwater

put it, rather than containment. Although American involvement steadily increased, Johnson refused to allow the reserves or the National Guard to serve in Vietnam, because that would involve congressional oversight. In August 1964 Johnson secured almost unanimous support in Congress for the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

, which gave the president very broad discretion to use military force as he saw fit. In February 1968 the Viet Cong launched an all-out attack on South Vietnamese forces across the country in the Tet Offensive. The ARVN (South Vietnam's army) successfully fought off the attacks and reduce the Viet Cong to a state of ineffectiveness; thereafter, it was the army of North Vietnam that was the main opponent. However the Tet Offensive proved a public relations disaster for Johnson, as the public increasingly realized the United States was deeply involved in a war that few people understood. Republicans, such as California Governor Ronald Reagan

, demanded victory or withdrawal, while on the left strident demands for immediate withdrawal escalated.

Starting in 1964, the antiwar movement began. Some opposed the war on moral grounds, rooting for the peasant Vietnamese against the modernizing capitalistic Americans. Opposition was centered among the black activists of the civil rights movement, and college students at elite universities.

Starting in 1964, the antiwar movement began. Some opposed the war on moral grounds, rooting for the peasant Vietnamese against the modernizing capitalistic Americans. Opposition was centered among the black activists of the civil rights movement, and college students at elite universities.

The Vietnam War was unprecedented for the intensity of media coverage—it has been called the first television war—as well as for the stridency of opposition to the war by the "New Left

".

The divide between pro- and anti-war Americans continued long after the conclusion of the war and became another factor leading to the "culture war

s" that increasingly divides Americans, continuing into the 21st century.

, jumped in on an antiwar platform, building a coalition of intellectuals students, and if I were elements of the party. McCarthy was not nationally known, but came close to Johnson in the critical primary in New Hampshire, thanks to thousands of students who took off their counter-culture garb and go "clean for Gene" to go door-to-door. Johnson no longer commanded majority support in his party, so he took the initiative and dropped out of the race, promising to begin peace talks with the enemy.

Seizing the opportunity caused by Johnson's departure from the race, Robert Kennedy

then joined in and ran for the nomination on an antiwar platform that drew support from ethnics and blacks. Vice President

Hubert Humphrey

was too late to enter the primaries, but he did assemble strong support from traditional factions in the Democratic Party. Humphrey, an ardent New Dealer, supported Johnson's war policy. The greatest outburst of rioting in national history came in April 1968 following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

.

Kennedy was on stage to claim victory over McCarthy in the California primary when he was assassinated; McCarthy was unable to overcome Humphrey's support within the party elite. The the Democratic national convention in Chicago was in a continuous uproar, with police confronting antiwar demonstrators in the streets and parks, and the bitter divisions of the Democratic Party revealing themselves inside the arena. Humphrey, with a coalition state organizations, city bosses such as Mayor Richard Daley, and labor unions won the nomination and ran against Republican Richard Nixon

an independent George Wallace

in the general election. Nixon appealed to what he claimed was the "silent majority" of moderate Americans who disliked the "hippie" counterculture. Nixon also promised "peace with honor" in ending the Vietnam War. He proposed the Nixon Doctrine

to establish the strategy to turn over the fighting of the war to the Vietnamese, which he called "Vietnamization." Nixon won the presidency, but the Democrats continued to control Congress. The profound splits in the Democratic Party lasted for decades.

era. He intervened aggressively in the economy, taking the nation off the gold standard and (for a while) imposing price and wage controls.

Nixon reoriented foreign policy away from containment

and toward detente

with both the Soviet Union and China, playing them off against each other. The detente policy with China is still the basic policy in the 21st century, while the Russians rejected detente and used American toleration to over-expand their operations in Latin America, Asia and Africa. Both Russia and China tolerated American policy in Vietnam, leaving their erstwhile ally North Vietnam stranded. Nixon promoted "Vietnamization," whereby the military of South Vietnam would be greatly enhanced so that U.S. forces could withdraw. The combat troops were gone by 1971 and Nixon could announce a peace treaty in 1973. His promises to Saigon that he would intervene if North Vietnam attacked were validated in 1972, but became worthless when he resigned in 1974. Despite having an elaborate military, South Vietnam was too corrupt and too lacking in self confidence to effectively resist the invasion by North Vietnam in 1975.

In May 1970 the antiwar effort escalated into violence, as National Guard troops shot at student demonstrators in the Kent State shootings

. The nation's higher education system, especially the elite schools, virtually shut down.

Riding on high approval ratings, Nixon was re-elected in 1972, soundly defeating the liberal, anti-war George McGovern

. At the same time, Nixon became a lightning rod for much public hostility regarding the war in Vietnam. The morality of conflict continued to be an issue, and incidents such as the My Lai massacre

further eroded support for the war and increased efforts of Vietnamization.

The growing Watergate scandal

was a major disaster for Nixon, eroding his political support in public opinion and in Washington. However he did manage to secure large-scale funding for South Vietnam, much of which was wasted.

The United States withdrew its troops from Vietnam before the Paris Peace Accords

in 1973. In 1975 North Vietnam invaded with conventional army forces and quickly conquered the South. The U.S. was not involved in the fighting in 1975 but did evacuate many Vietnamese. Later nearly one million managed to flee to the U.S. as refugees. The impact on the U.S. was muted, with few political recriminations, but it did leave a "Vietnam Syndrome

" that cautioned against further military interventions anywhere else. Nixon (and his next two successors Ford and Carter) had dropped the containment policy and were not willing to intervene anywhere.

suppliers were increasingly demanding higher prices. The automobile

, steel

, and electronics industries were also beginning to face stiff competition in the U.S. domestic market by foreign producers who had more modern factories (as Europe and Japan's industrial bases had been largely rebuilt from the ground up following WWII) and higher-quality products.

Nixon promised to tackle sluggish growth and inflation, known as "stagflation

", through higher taxes and lower spending; this met stiff resistance in Congress. As a result, Nixon changed course and opted to control the currency; his appointees to the Federal Reserve sought a contraction of the money supply through higher interest rates but to little avail; the tight money policy did little to curb inflation. The cost of living rose a cumulative 15% during Nixon's first two years in office.

By the summer of 1971, Nixon was under strong public pressure to act decisively to reverse the economic tide. On August 15, 1971, he ended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold, which meant the demise of the Bretton Woods system

, in place since World War II. As a result, the U.S. dollar fell in world markets. The devaluation helped stimulate American exports, but it also made the purchase of vital inputs, raw materials, and finished goods from abroad more expensive. Also, on August 15, 1971, under the provisions of the Economic Stabilization Act of 1970

, Nixon implemented "Phase I" of his economic plan: a ninety-day freeze on all wages and prices above their existing levels. In November, "Phase II" entailed mandatory guidelines for wage and price increases to be issued by a federal agency. Inflation subsided temporarily, but the recession continued with rising unemployment. To combat the recession, Nixon reversed course and adopted an expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. In "Phase III", the strict wage and price controls were lifted. As a result, inflation

resumed its upward spiral.

Inflationary pressures led to key shifts in economic policies. Following the Great Depression

of the 1930s, recessions—periods of slow economic growth and high unemployment—were viewed as the greatest of economic threats, which could be counteracted by heavy government spending or cutting taxes so that consumers would spend more. In the 1970s, major price increases, particularly for energy, created a strong fear of inflation; as a result, government leaders concentrated more on controlling inflation than on combating recession by limiting spending, resisting tax cuts, and reining in growth in the money supply.

The erratic economic programs of the Nixon administration were indicative of a broader national confusion about the prospects for future American prosperity. With little understanding of the international forces creating the economic problems, Nixon, American economists, and the public focused on immediate issues and short-term solutions. These underlying problems set the stage for conservative reaction, a more aggressive foreign policy, and a retreat from welfare-based solutions for minorities and the poor that would characterize the subsequent decades.

A new consciousness of the inequality of American women began sweeping the nation, starting with the 1963 publication of Betty Friedan

A new consciousness of the inequality of American women began sweeping the nation, starting with the 1963 publication of Betty Friedan

's best-seller, The Feminine Mystique

, which explained how many housewives felt trapped and unfulfilled, assaulted American culture for its creation of the notion that women could only find fulfillment through their roles as wives, mothers, and keepers of the home, and argued that women were just as able as men to do every type of job. In 1966 Friedan and others established the National Organization for Women

, or NOW, to act as an NAACP for women.

Protests began, and the new "Women's Liberation Movement" grew in size and power, gained much media attention, and, by 1968, had replaced the Civil Rights Movement as the U.S.'s main social revolution. Marches, parades, rallies, boycotts, and pickets brought out thousands, sometimes millions; Friedan's Women's Strike for Equality

(1970) was a nation-wide success. The Movement was split into factions by political ideology early on, however (NOW on the left, the Women's Equity Action League

(WEAL) on the right, the National Women's Political Caucus

(NWPC) in the center, and more radical groups formed by younger women on the far left).

Along with Friedan, Gloria Steinem

was an important feminist leader, co-founding the NWPC, the Women's Action Alliance

, and editing the Movement's magazine, Ms. The proposed Equal Rights Amendment

to the Constitution, passed by Congress in 1972 and favored by about seventy percent of the American public, failed to be ratified in 1982, with only three more states needed to make it law. The nation's conservative women, led by activist Phyllis Schlafly

, defeated the ERA by arguing that it degraded the position of the housewife, and made young women susceptible to the military draft. The failure of the ERA effectively marked the end of the women's liberation movement.

However, many federal laws (i.e. those equalizing pay, employment, education

, employment opportunites, credit

, ending pregnancy discrimination, and requiring NASA

, the Military Academies, and other organizations to admit women), state laws (i.e. those ending spousal abuse and marital rape

), Supreme Court rulings (i.e. ruling the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applied to women), and state ERAs established women's equal status under the law, and social custom and consciousness began to change, accepting women's equality.

in 1973 that women have a constitutional right to choose an abortion, and that cannot be nullified by state laws. Feminists celebrated the decisions but Catholics, who had opposed abortion since the 1890s, formed a coalition with Evangelical Protestants (long the arch-foes of Catholics) to try to reverse the decision. The Republican party began taking anti-abortion positions as the Democrats announced in favor of choice (that is, allowing women the right to choose an abortion). The issue has inflamed state and national politics ever since.

To make matters worse, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) began displaying its strength; oil

To make matters worse, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) began displaying its strength; oil

, fueling automobiles and homes in a country increasingly dominated by suburbs (where large homes and automobile-ownership are more common), became an economic and political tool for Third World nations to begin fighting for their concerns. Following the 1973 Yom Kippur War

, Arab members of OPEC announced they would no longer ship petroleum to nations supporting Israel

, that is, to the United States and Western Europe

. At the same time, other OPEC nations agreed to raise their prices 400%. This resulted in the 1973 world oil shock, during which U.S. motorists faced long lines at gas stations. Public and private facilities closed down to save on heating oil

; and factories cut production and laid off workers. No single factor than the oil embargo did more to produce the soaring inflation of the 1970s, though this event was part of a much larger energy crisis

that characterized the decade.

The U.S. government response to the embargo was quick but of limited effectiveness. A national maximum speed limit

of 55 mph (88 km/h) was imposed to help reduce consumption. President Nixon named William E. Simon

as "Energy Czar

", and in 1977, a cabinet-level Department of Energy was created, leading to the creation of the United States' Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The National Energy Act of 1978 was also a response to this crisis.

The federal government further exacerbated the recession by instilling price controls in the United States, which limited the price of "old oil" (that already discovered) while allowing newly discovered oil to be sold at a higher price, resulting in a withdrawal of old oil from the market and artificial scarcity. The rule had been intended to promote oil exploration. This scarcity was dealt with by rationing of gasoline (which occurred in many countries), with motorists facing long lines at gas stations.

In the U.S., under odd-even rationing

, drivers of vehicles with license plates having an odd number as the last digit (or a vanity license plate) were allowed to purchase gasoline for their cars only on odd-numbered days of the month, while drivers of vehicles with even-numbered license plates were allowed to purchase fuel only on even-numbered days. The rule did not apply on the 31st day of those months containing 31 days.

The crisis also prompted a call for individuals and businesses to conserve energy — most notably a campaign by the Advertising Council using the tag line "Don't Be Fuelish." Many newspapers carried full-page advertisements that featured cut-outs which could be attached to light switches that had the slogan "Last Out, Lights Out: Don't Be Fuelish" emblazoned thereon.

The crisis also prompted a call for individuals and businesses to conserve energy — most notably a campaign by the Advertising Council using the tag line "Don't Be Fuelish." Many newspapers carried full-page advertisements that featured cut-outs which could be attached to light switches that had the slogan "Last Out, Lights Out: Don't Be Fuelish" emblazoned thereon.

The U.S. "Big Three

" automakers' first order of business after Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards were enacted was to downsize existing automobile categories. By the end of the 1970s, 121-inch wheelbase vehicles with a 4,500 pound GVW (gross weight) were a thing of the past. Before the mass production of automatic overdrive transmissions and electronic fuel injection, the traditional front engine/rear wheel drive layout was being phased out for the more efficient and/or integrated front engine/front wheel drive, starting with compact cars. Using the Volkswagen Rabbit as the archetype, much of Detroit went to front wheel drive after 1980 in response to CAFE's 27.5 mpg mandate. Vehicles such as the Ford Fairmont

were short-lived in the early 1980s.

Though not required by legislation, the sport of auto racing voluntarily sought reductions. The 24 Hours of Daytona was canceled in 1974. Also in 1974, NASCAR

reduced all race distances by 10%. At the Indianapolis 500

, qualifying was reduced from four days down to two, and several days of practice were eliminated.

s sought each other's help. In February 1972, Nixon made a historic visit to Communist China. Relations with that country had been largely hostile since the Korean War, and the United States still maintained that the Nationalist regime in Taiwan was the legitimate government of China. There had been a number of diplomatic meetings with Chinese officials in Warsaw over the years however, and President Kennedy had planned to reestablish ties in his second term. However, his death, along with the Vietnam War and the Cultural Revolution caused any chance of normalized relations to disappear for the next several years. Nixon, once a staunch supporter of Chiang Kai-shek

, came increasingly to believe in restoring relations with the Communist government by the late 1960s. In August 1971, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

made a secret trip to Beijing. The official visit by the president was a nationally televised event, and the US delegation met with Chairman Mao Zedong

and other Chinese leaders. Restoring relations between China and the US was also an important matter of Cold War politics. Since the Soviet Union had become bitterly hostile to China since the Cultural Revolution, both nations decided that, regardless of political and ideological differences, the saying "the enemy of my enemy is my friend" held true. After the China trip, Nixon met Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev

and signed the SALT Treaty in Vienna.

Détente had both strategic and economic benefits for both superpowers. Arms control enabled both superpowers to slow the spiraling increases in their bloated defense budgets. Before, the Johnson Administration failed to defeat Communist forces, his deficit-spending to sustain the war effort weakened the U.S. economy for decades to come, contributing to a decade of "stagflation." Meanwhile, the Soviets

could neither stop bloody clashes between Soviet and Chinese troops along their common border nor bolster a Soviet economy declining, in part, because of heavy military expenditures. But the détente suffered amid outbreaks in the Middle East

and Africa, especially southern and eastern Africa.

In 1972, Nixon won the GOP nomination. The antiwar left now made him their primary enemy and the Democrats ran Massachusetts Senator George McGovern

In 1972, Nixon won the GOP nomination. The antiwar left now made him their primary enemy and the Democrats ran Massachusetts Senator George McGovern

for president, but Nixon effectively took away any major issue he could run on by having ended the draft, began pulling out of Vietnam, and restored ties with China. McGovern was ridiculed as the candidate of "acid, amnesty, and abortion" and on Election Day, Nixon carried every state except Massachusetts for the most lopsided presidential election since 1820.

Nixon was investigated for the instigation and cover-up of the burglary of the Democratic Party offices at the Watergate

office complex. The House of Representatives

Judiciary Committee opened formal and public impeachment

hearings against Nixon on May 9, 1974. Rather than face impeachment by the House of Representatives and a possible conviction by the Senate

, he resigned, effective August 9, 1974. His successor, Gerald R. Ford, a moderate Republican, issued a pre-emptive pardon of Nixon, ending the investigations of him.

, who retired in 2010. During Ford's administration, the nation also celebrated its 200th birthday on July 4, 1976. The event brought some enthusiasm to an American populace that was feeling highly cynical and disillusioned from Vietnam, Watergate, and economic difficulties. Ford's pardon of Nixon just before the 1974 midterm elections was not well received, and the Democrats made major gains, bringing to power a generation of young liberal activists, many of them suspicious of the military and the CIA.

Governor Jimmy Carter

, a Washington, DC outsider known for his integrity, prevailed over nationally better-known politicians in the Democratic Party Presidential primaries in 1976. Faith in government was at a low ebb, and so was voter turnout. Carter became the first candidate from the Deep South

to be elected President since the American Civil War

. He stressed the fact that he was an outsider not part of the Beltway political system, and also the fact that he was not a lawyer. Carter undertook various populist measures such as walking to the Capitol for his inauguration and wearing a sweater in the Oval Office to encourage energy conservation. The new president began his administration with a Democrat Congress. Carter's major accomplishments consisted of the creation of a national energy policy and the consolidation of governmental agencies, resulting in two new cabinet departments, the United States Department of Energy

and the United States Department of Education

. Congress successfully deregulated the trucking, airline, rail, finance, communications, and oil industries, and bolstered the social security

system. Carter appointed record numbers of women and minorities to significant government and judicial posts, but nevertheless managed to feud with feminist leaders. Environmentalists promoted strong legislation on environmental protection, through the expansion of the National Park Service

in Alaska

, creating 103 million new acres of land. Even with all of these successes, Carter failed to implement a national health plan or to reform the tax system, as he had promised in his campaign.

Emphasizing the energy crisis, he mandated restrictions on speed limits and the heating of buildings. But the voters grew increasingly worried about the economy—stagnation combined with high inflation became "stagflation". In 1979, Carter gave a nationally televised address in which he blamed the nation's troubles on the crisis of confidence among the American people. This "malaise speech" further damaged his reelection bid because it seemed to express a pessimistic outlook and blamed the American people for his own failed policies.

In foreign affairs, Carter's accomplishments consisted of the Camp David Accords

, the Panama Canal Treaties, the creation of full diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China

, and the negotiation of the SALT II Treaty. In addition, he championed human rights throughout the world and used human rights as the center of his administration's foreign policy.

Although foreign policy remained quiet during Carter's first two years, the Soviet Union appeared to be getting stronger. It was expanding its influence into the Third World along with the help of allies such as Cuba, and the pace of Soviet military spending steadily rose. In 1979, Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan to prop up a Marxist regime there. After nine years of fighting, the Soviets were unable to suppress Afghan rebels and pulled out of the country. Meanwhile, American forces in Europe, neglected during the Vietnam War, were expected to face the Soviets with 1950s-era weaponry. The US military nearly disintegrated in the aftermath of Vietnam with low morale, racial tensions, and drug use.

The high point of Carter's foreign-policy came in 1978, when he mediated the Camp David Accords

between Egypt and Israel, ending the state of war that had existed between those two countries since 1967.

In 1979, Carter completed the process begun by Nixon of restoring ties with China. Full diplomatic relations were established on January 1 of that year despite protests from Senator Barry Goldwater

and some other conservative Republicans. Unofficial relations with Taiwan were maintained. Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping

then visited the US in February 1979.

Carter also tried to place another cap on the arms race with a SALT II agreement in 1979, and faced the Islamic Revolution

in Iran

, the Nicaraguan Revolution

, and the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan. In 1979, Carter allowed the former Iranian Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi into the United States for medical treatment. In response Iranian militants seized the American embassy in Iranian hostage crisis, taking 52 Americans hostage and demanded the Shah's return to Iran for trial and execution. The hostage crisis continued for 444 days and dominated the last year of Carter's presidency, ruining the Presidents tattered reputation for competence in foreign affairs. Carter's responses to the crisis, from a "Rose Garden strategy" of staying inside the White House

to the failed military attempt to rescue the hostages, did not inspire confidence in the administration by the American people.

African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)

The African-American Civil Rights Movement refers to the movements in the United States aimed at outlawing racial discrimination against African Americans and restoring voting rights to them. This article covers the phase of the movement between 1955 and 1968, particularly in the South...

; the escalation and ending of the Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

; the drama of a generational revolt with its sexual freedoms and use of drugs; and the continuation of the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

, with its Space Race

Space Race

The Space Race was a mid-to-late 20th century competition between the Soviet Union and the United States for supremacy in space exploration. Between 1957 and 1975, Cold War rivalry between the two nations focused on attaining firsts in space exploration, which were seen as necessary for national...

to put a man on the Moon. The economy was prosperous until the early 1970s, then faltered under new foreign competition and high oil prices. By 1980 and the seizure of the American Embassy in Iran, there was a growing sense of national malaise. This period is closed by the victory of conservative Republican Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

, opening the "Age of Reagan" with a dramatic change in national direction.

Memories of the 1960s shaped the political landscape for the next half-century. As Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson "Bill" Clinton is an American politician who served as the 42nd President of the United States from 1993 to 2001. Inaugurated at age 46, he was the third-youngest president. He took office at the end of the Cold War, and was the first president of the baby boomer generation...

explained in 2004, "If you look back on the Sixties and think there was more good than bad, you're probably a Democrat

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

. If you think there was more harm than good, you're probably a Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

."

Climax of liberalism

The climax of liberalism came in the mid-1960s with the success of President Lyndon B. JohnsonLyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

(1963–69) in securing congressional passage of his Great Society

Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States promoted by President Lyndon B. Johnson and fellow Democrats in Congress in the 1960s. Two main goals of the Great Society social reforms were the elimination of poverty and racial injustice...

programs, including civil rights, the end of segregation, Medicare, extension of welfare, federal aid to education at all levels, subsidies for the arts and humanities, environmental activism, and a series of programs designed to wipe out poverty. As recent historians have explained:

- "Gradually, liberal intellectuals crafted a new vision for achieving economic and social justice. The liberalism of the early 1960s contained no hint of radicalism, little disposition to revive new deal era crusades against concentrated economic power, and no intention to fast and class passions or redistribute wealth or restructure existing institutions. Internationally it was strongly anti-Communist. It aimed to defend the free world, to encourage economic growth at home, and to ensure that the resulting plenty was fairly distributed. Their agenda-much influenced by Keynesian economic theory-envisioned massive public expenditure that would speed economic growth, thus providing the public resources to fund larger welfare, housing, health, and educational programs."

Johnson was rewarded with an electoral landslide in 1964 against conservative Barry Goldwater

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater was a five-term United States Senator from Arizona and the Republican Party's nominee for President in the 1964 election. An articulate and charismatic figure during the first half of the 1960s, he was known as "Mr...

, which broke the decades-long control of Congress by the Conservative coalition

Conservative coalition

In the United States, the conservative coalition was an unofficial Congressional coalition bringing together the conservative majority of the Republican Party and the conservative, mostly Southern, wing of the Democratic Party...

. But the Republicans bounced back in 1966, and Republicans elected Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

in 1968. Nixon largely continued the New Deal and Great Society programs he inherited; conservative reaction would come with the election of Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

in 1980.

Civil rights

The 1960s were marked by street protests, demonstrations, rioting, civil unrest, antiwar protests, and a cultural revolution. African-American youth protested following victories in the courts regarding civil rightsCivil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

with street protests led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as well as the NAACP

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, usually abbreviated as NAACP, is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909. Its mission is "to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to...

. King skillfully used the media to record instances of brutality against non-violent African-American protesters to tug at the conscience of the public. Activism brought about successful political change when there was an aggrieved group, such as African-Americans or feminists or homosexuals, who felt the sting of bad policy over time, and who conducted long-range campaigns of protest together with media campaigns to change public opinion along with campaigns in the courts to change policy.

The assassination of Kennedy

John F. Kennedy assassination

John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the thirty-fifth President of the United States, was assassinated at 12:30 p.m. Central Standard Time on Friday, November 22, 1963, in Dealey Plaza, Dallas, Texas...

in 1963 helped change the political mood of the country. The new President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

, Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

, capitalized on this situation, using a combination of the national mood and his own political savvy to push Kennedy's agenda; most notably, the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation in the United States that outlawed major forms of discrimination against African Americans and women, including racial segregation...

.

In addition, the 1965 Voting Rights Act

Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of national legislation in the United States that outlawed discriminatory voting practices that had been responsible for the widespread disenfranchisement of African Americans in the U.S....

had an immediate impact on federal, state and local elections. Within months of its passage on August 6, 1965, one quarter of a million new black voters had been registered, one third by federal examiners. Within four years, voter registration in the South

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

had more than doubled. In 1965, Mississippi

Mississippi

Mississippi is a U.S. state located in the Southern United States. Jackson is the state capital and largest city. The name of the state derives from the Mississippi River, which flows along its western boundary, whose name comes from the Ojibwe word misi-ziibi...

had the highest black voter turnout, 74%, and had more elected black-leaders than any other state. In 1969, Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

had a 92.1% voter turnout, Arkansas

Arkansas

Arkansas is a state located in the southern region of the United States. Its name is an Algonquian name of the Quapaw Indians. Arkansas shares borders with six states , and its eastern border is largely defined by the Mississippi River...

77.9%, and Texas

Texas

Texas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

77.3%.

Election of 1964

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

opponent, Barry Goldwater

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater was a five-term United States Senator from Arizona and the Republican Party's nominee for President in the 1964 election. An articulate and charismatic figure during the first half of the 1960s, he was known as "Mr...

, who the campaign characterized as hardline right-wing. Most famously, the Johnson campaign ran a commercial entitled the "Daisy Girl" ad, which featured a little girl picking petals from a daisy in a field, counting the petals, which then segues into a launch countdown and a nuclear explosion

Nuclear explosion

A nuclear explosion occurs as a result of the rapid release of energy from an intentionally high-speed nuclear reaction. The driving reaction may be nuclear fission, nuclear fusion or a multistage cascading combination of the two, though to date all fusion based weapons have used a fission device...

. Johnson soundly defeated Goldwater in the general election, winning 64.9% of the popular vote, and losing only five states in the Deep South, where blacks were not yet allowed to vote, along with Goldwater's Arizona.

Goldwater's race energized the conservative movement, chiefly inside the Republican party. It looked for a new leader and found one in Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

, elected governor of California in 1966 and reelected in 1970. He ran against President Ford for the 1976 GOP nomination, and narrowly lost, but the stage was set for Reagan in 1980.

Anti-poverty programs

Two main goals of the Great Society social reforms were the elimination of poverty and racial injustice. New major spending programs that addressed education, medical care, urban problems, and transportation were launched during this period. The Great Society in scope and sweep resembled the New DealNew Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

domestic agenda of Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

in the 1930s, but differed sharply in types of programs enacted.

The largest and most enduring federal assistance programs, launched in 1965, were Medicare

Medicare (United States)

Medicare is a social insurance program administered by the United States government, providing health insurance coverage to people who are aged 65 and over; to those who are under 65 and are permanently physically disabled or who have a congenital physical disability; or to those who meet other...

, which pays for many of the medical costs of the elderly, and Medicaid

Medicaid

Medicaid is the United States health program for certain people and families with low incomes and resources. It is a means-tested program that is jointly funded by the state and federal governments, and is managed by the states. People served by Medicaid are U.S. citizens or legal permanent...

, which aids poor people.

The centerpiece of the War on Poverty

War on Poverty

The War on Poverty is the unofficial name for legislation first introduced by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. This legislation was proposed by Johnson in response to a national poverty rate of around nineteen percent...

was the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964

Economic Opportunity Act of 1964

Signed by Lyndon B. Johnson on August 20, 1964, the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 was central to Johnson's Great Society campaign and its War on Poverty. Implemented by the since disbanded Office of Economic Opportunity, the Act included several social programs to promote the health, education,...

, which created an Office of Economic Opportunity

Office of Economic Opportunity

The Office of Economic Opportunity was the agency responsible for administering most of the War on Poverty programs created as part of United States President Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society legislative agenda.- History :...

(OEO) to oversee a variety of community-based antipoverty programs. The OEO reflected a fragile consensus among policymakers that the best way to deal with poverty was not simply to raise the incomes of the poor but to help them better themselves through education, job training, and community development. Central to its mission was the idea of "community action

Community Action Agencies

In the United States and its territories, Community Action Agencies are local private and public non-profit organizations that carry out the Community Action Program , which was founded by the 1964 Economic Opportunity Act to fight poverty by empowering the poor as part of the War on Poverty.CAAs...

", the participation of the poor in framing and administering the programs designed to help them.

Generational revolt and counterculture

As the 1960s progressed, increasing numbers of young people began to revolt against the social norms and conservatism from the 1950s and early 1960s as well as the escalation of the Vietnam WarVietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

and Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

. A social revolution swept through the country to create a more liberated society. As the Civil Rights Movement progressed, feminism

Feminism

Feminism is a collection of movements aimed at defining, establishing, and defending equal political, economic, and social rights and equal opportunities for women. Its concepts overlap with those of women's rights...

and environmentalism

Environmentalism

Environmentalism is a broad philosophy, ideology and social movement regarding concerns for environmental conservation and improvement of the health of the environment, particularly as the measure for this health seeks to incorporate the concerns of non-human elements...

movements soon grew in the midst of a Sexual Revolution

Sexual revolution

The sexual revolution was a social movement that challenged traditional codes of behavior related to sexuality and interpersonal relationships throughout the Western world from the 1960s into the 1980s...

with its distinctive protest forms, from long hair to rock music. The Hippie

Hippie

The hippie subculture was originally a youth movement that arose in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to other countries around the world. The etymology of the term 'hippie' is from hipster, and was initially used to describe beatniks who had moved into San Francisco's...

culture, which emphasized peace, love and freedom, was introduced to the mainstream. In 1967, the Summer of Love

Summer of Love

The Summer of Love was a social phenomenon that occurred during the summer of 1967, when as many as 100,000 people converged on the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, creating a cultural and political rebellion...

, an event in San Francisco where thousands of young people loosely and freely united for a new social experience, helped introduce much of the world to the culture. In addition, the increase use of psychedelic drugs, such as LSD

LSD

Lysergic acid diethylamide, abbreviated LSD or LSD-25, also known as lysergide and colloquially as acid, is a semisynthetic psychedelic drug of the ergoline family, well known for its psychological effects which can include altered thinking processes, closed and open eye visuals, synaesthesia, an...

and marijuana

Cannabis (drug)

Cannabis, also known as marijuana among many other names, refers to any number of preparations of the Cannabis plant intended for use as a psychoactive drug or for medicinal purposes. The English term marijuana comes from the Mexican Spanish word marihuana...

, also became central to the movement. Music of the time also played a large role with the introduction of folk rock

Folk rock

Folk rock is a musical genre combining elements of folk music and rock music. In its earliest and narrowest sense, the term referred to a genre that arose in the United States and the UK around the mid-1960s...

and later Acid Rock

Acid rock

Acid rock is a form of psychedelic rock, which is characterized with long instrumental solos, few lyrics and musical improvisation. Tom Wolfe describes the LSD-influenced music of The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Pink Floyd, The Doors, Iron Butterfly, Big Brother & The Holding Company, Cream,...

and Psychedelia which became the voice of the generation. The Counterculture Revolution was exemplified in 1969 with the historic Woodstock Festival

Woodstock Festival

Woodstock Music & Art Fair was a music festival, billed as "An Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music". It was held at Max Yasgur's 600-acre dairy farm in the Catskills near the hamlet of White Lake in the town of Bethel, New York, from August 15 to August 18, 1969...

..

Conclusion of the Space Race

Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 ) was the first artificial satellite to be put into Earth's orbit. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957. The unanticipated announcement of Sputnik 1s success precipitated the Sputnik crisis in the United States and ignited the Space...

, in 1957, the United States competed with the Soviet Union for supremacy in outer space exploration. After the Soviets placed the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin

Yuri Gagarin

Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin was a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut. He was the first human to journey into outer space, when his Vostok spacecraft completed an orbit of the Earth on April 12, 1961....

, in 1961, President John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

pushed for ways in which NASA

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration is the agency of the United States government that is responsible for the nation's civilian space program and for aeronautics and aerospace research...

could catch up, famously urging action a manned mission to the Moon

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

: "I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth." The first manned flights produced by this effort came from Project Gemini

Project Gemini

Project Gemini was the second human spaceflight program of NASA, the civilian space agency of the United States government. Project Gemini was conducted between projects Mercury and Apollo, with ten manned flights occurring in 1965 and 1966....

(1965–1966) and then by the Apollo program, which despite the tragic loss of the Apollo 1

Apollo 1

Apollo 1 was scheduled to be the first manned mission of the Apollo manned lunar landing program, with a target launch date of February 21, 1967. A cabin fire during a launch pad test on January 27 at Launch Pad 34 at Cape Canaveral killed all three crew members: Command Pilot Virgil "Gus"...

crew, achieved Kennedy's goal by landing the first astronauts on the Moon with the Apollo 11

Apollo 11

In early 1969, Bill Anders accepted a job with the National Space Council effective in August 1969 and announced his retirement as an astronaut. At that point Ken Mattingly was moved from the support crew into parallel training with Anders as backup Command Module Pilot in case Apollo 11 was...

mission in 1969.

Having lost the race to the Moon, the Soviets shifted their attention to orbital space station

Space station

A space station is a spacecraft capable of supporting a crew which is designed to remain in space for an extended period of time, and to which other spacecraft can dock. A space station is distinguished from other spacecraft used for human spaceflight by its lack of major propulsion or landing...

s, launching the first (Salyut 1

Salyut 1

Salyut 1 was the first space station of any kind, launched by the USSR on April 19, 1971. It was launched unmanned using a Proton-K rocket. Its first crew came later in Soyuz 10, but was unable to dock completely; its second crew launched in Soyuz 11 and remained on board for 23 days...

) in 1971. The U.S. responded with the Skylab

Skylab

Skylab was a space station launched and operated by NASA, the space agency of the United States. Skylab orbited the Earth from 1973 to 1979, and included a workshop, a solar observatory, and other systems. It was launched unmanned by a modified Saturn V rocket, with a mass of...

orbital workstation, in use from 1973 through 1974. With détente, a time of relatively improved Cold War relations between the United States and the Soviets, the two superpowers developed a cooperative space mission: the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project. This 1975 joint mission was the last manned space flight for the U.S. until the Space Shuttle

Space Shuttle

The Space Shuttle was a manned orbital rocket and spacecraft system operated by NASA on 135 missions from 1981 to 2011. The system combined rocket launch, orbital spacecraft, and re-entry spaceplane with modular add-ons...

flights of 1981 and has been described as the symbolic end of the Space Race. The Space Race sparked unprecedented increases in spending on education and pure research, which accelerated scientific advancements and led to beneficial spin-off technologies.

Vietnam War

The ContainmentContainment

Containment was a United States policy using military, economic, and diplomatic strategies to stall the spread of communism, enhance America’s security and influence abroad, and prevent a "domino effect". A component of the Cold War, this policy was a response to a series of moves by the Soviet...

policy meant fighting communist expansion where ever it occurred, and the Communist picked where the American allies were weakest. Johnson's primary commitment was to his domestic policy, so he tried to minimize public awareness and congressional oversight of the operations in the war. Most of his advisers were pessimistic about the long run possibilities, and Johnson feared that if Congress took control, it would demand "Why Not Victory", as Barry Goldwater

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater was a five-term United States Senator from Arizona and the Republican Party's nominee for President in the 1964 election. An articulate and charismatic figure during the first half of the 1960s, he was known as "Mr...

put it, rather than containment. Although American involvement steadily increased, Johnson refused to allow the reserves or the National Guard to serve in Vietnam, because that would involve congressional oversight. In August 1964 Johnson secured almost unanimous support in Congress for the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

The Tonkin Gulf Resolution was a joint resolution which the United States Congress passed on August 10, 1964 in response to a sea battle between the North Vietnamese Navy's Torpedo Squadron 10135 and the destroyer on August 2 and an alleged second naval engagement between North Vietnamese boats...

, which gave the president very broad discretion to use military force as he saw fit. In February 1968 the Viet Cong launched an all-out attack on South Vietnamese forces across the country in the Tet Offensive. The ARVN (South Vietnam's army) successfully fought off the attacks and reduce the Viet Cong to a state of ineffectiveness; thereafter, it was the army of North Vietnam that was the main opponent. However the Tet Offensive proved a public relations disaster for Johnson, as the public increasingly realized the United States was deeply involved in a war that few people understood. Republicans, such as California Governor Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

, demanded victory or withdrawal, while on the left strident demands for immediate withdrawal escalated.

Antiwar movement

The Vietnam War was unprecedented for the intensity of media coverage—it has been called the first television war—as well as for the stridency of opposition to the war by the "New Left

New Left

The New Left was a term used mainly in the United Kingdom and United States in reference to activists, educators, agitators and others in the 1960s and 1970s who sought to implement a broad range of reforms, in contrast to earlier leftist or Marxist movements that had taken a more vanguardist...

".

The divide between pro- and anti-war Americans continued long after the conclusion of the war and became another factor leading to the "culture war

Culture war

The culture war in American usage is a metaphor used to claim that political conflict is based on sets of conflicting cultural values. The term frequently implies a conflict between those values considered traditionalist or conservative and those considered progressive or liberal...

s" that increasingly divides Americans, continuing into the 21st century.

1968 and the breakup of the Democratic Party

In 1968, Johnson saw his overwhelming coalition in 1964 disintegrate. Liberal and moderate Republicans returned to their party, and supported Richard Nixon for the GOP nomination. George Wallace pulled off the majority of Southern whites, for a century the core of the Solid South in the Democratic Party. Increasingly, the blacks, students, and intellectuals were fiercely opposed to Johnson's policy. With Robert Kennedy hesitant about joining the contest, Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthyEugene McCarthy

Eugene Joseph "Gene" McCarthy was an American politician, poet, and a long-time member of the United States Congress from Minnesota. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1949 to 1959 and the U.S. Senate from 1959 to 1971.In the 1968 presidential election, McCarthy was the first...

, jumped in on an antiwar platform, building a coalition of intellectuals students, and if I were elements of the party. McCarthy was not nationally known, but came close to Johnson in the critical primary in New Hampshire, thanks to thousands of students who took off their counter-culture garb and go "clean for Gene" to go door-to-door. Johnson no longer commanded majority support in his party, so he took the initiative and dropped out of the race, promising to begin peace talks with the enemy.

Seizing the opportunity caused by Johnson's departure from the race, Robert Kennedy

Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis "Bobby" Kennedy , also referred to by his initials RFK, was an American politician, a Democratic senator from New York, and a noted civil rights activist. An icon of modern American liberalism and member of the Kennedy family, he was a younger brother of President John F...

then joined in and ran for the nomination on an antiwar platform that drew support from ethnics and blacks. Vice President

Vice President of the United States

The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term...

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey, Jr. , served under President Lyndon B. Johnson as the 38th Vice President of the United States. Humphrey twice served as a United States Senator from Minnesota, and served as Democratic Majority Whip. He was a founder of the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party and...

was too late to enter the primaries, but he did assemble strong support from traditional factions in the Democratic Party. Humphrey, an ardent New Dealer, supported Johnson's war policy. The greatest outburst of rioting in national history came in April 1968 following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for being an iconic figure in the advancement of civil rights in the United States and around the world, using nonviolent methods following the...

.

Kennedy was on stage to claim victory over McCarthy in the California primary when he was assassinated; McCarthy was unable to overcome Humphrey's support within the party elite. The the Democratic national convention in Chicago was in a continuous uproar, with police confronting antiwar demonstrators in the streets and parks, and the bitter divisions of the Democratic Party revealing themselves inside the arena. Humphrey, with a coalition state organizations, city bosses such as Mayor Richard Daley, and labor unions won the nomination and ran against Republican Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

an independent George Wallace

George Wallace

George Corley Wallace, Jr. was the 45th Governor of Alabama, serving four terms: 1963–1967, 1971–1979 and 1983–1987. "The most influential loser" in 20th-century U.S. politics, according to biographers Dan T. Carter and Stephan Lesher, he ran for U.S...

in the general election. Nixon appealed to what he claimed was the "silent majority" of moderate Americans who disliked the "hippie" counterculture. Nixon also promised "peace with honor" in ending the Vietnam War. He proposed the Nixon Doctrine

Nixon Doctrine

The Nixon Doctrine was put forth in a press conference in Guam on July 25, 1969 by U.S. President Richard Nixon. He stated that the United States henceforth expected its allies to take care of their own military defense, but that the U.S. would aid in defense as requested...

to establish the strategy to turn over the fighting of the war to the Vietnamese, which he called "Vietnamization." Nixon won the presidency, but the Democrats continued to control Congress. The profound splits in the Democratic Party lasted for decades.

The Nixon Administration

As President Richard Nixon adopted many liberal positions, especially regarding health care, welfare spending, environmentalism and support for the arts and humanities. He maintained the high taxes and strong economic regulations of the New DealNew Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

era. He intervened aggressively in the economy, taking the nation off the gold standard and (for a while) imposing price and wage controls.

Nixon reoriented foreign policy away from containment

Containment

Containment was a United States policy using military, economic, and diplomatic strategies to stall the spread of communism, enhance America’s security and influence abroad, and prevent a "domino effect". A component of the Cold War, this policy was a response to a series of moves by the Soviet...

and toward detente

Détente

Détente is the easing of strained relations, especially in a political situation. The term is often used in reference to the general easing of relations between the Soviet Union and the United States in the 1970s, a thawing at a period roughly in the middle of the Cold War...

with both the Soviet Union and China, playing them off against each other. The detente policy with China is still the basic policy in the 21st century, while the Russians rejected detente and used American toleration to over-expand their operations in Latin America, Asia and Africa. Both Russia and China tolerated American policy in Vietnam, leaving their erstwhile ally North Vietnam stranded. Nixon promoted "Vietnamization," whereby the military of South Vietnam would be greatly enhanced so that U.S. forces could withdraw. The combat troops were gone by 1971 and Nixon could announce a peace treaty in 1973. His promises to Saigon that he would intervene if North Vietnam attacked were validated in 1972, but became worthless when he resigned in 1974. Despite having an elaborate military, South Vietnam was too corrupt and too lacking in self confidence to effectively resist the invasion by North Vietnam in 1975.

In May 1970 the antiwar effort escalated into violence, as National Guard troops shot at student demonstrators in the Kent State shootings

Kent State shootings

The Kent State shootings—also known as the May 4 massacre or the Kent State massacre—occurred at Kent State University in the city of Kent, Ohio, and involved the shooting of unarmed college students by members of the Ohio National Guard on Monday, May 4, 1970...

. The nation's higher education system, especially the elite schools, virtually shut down.

Riding on high approval ratings, Nixon was re-elected in 1972, soundly defeating the liberal, anti-war George McGovern

George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern is an historian, author, and former U.S. Representative, U.S. Senator, and the Democratic Party nominee in the 1972 presidential election....

. At the same time, Nixon became a lightning rod for much public hostility regarding the war in Vietnam. The morality of conflict continued to be an issue, and incidents such as the My Lai massacre

My Lai Massacre

The My Lai Massacre was the Vietnam War mass murder of 347–504 unarmed civilians in South Vietnam on March 16, 1968, by United States Army soldiers of "Charlie" Company of 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade of the Americal Division. Most of the victims were women, children , and...

further eroded support for the war and increased efforts of Vietnamization.

The growing Watergate scandal

Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a political scandal during the 1970s in the United States resulting from the break-in of the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C., and the Nixon administration's attempted cover-up of its involvement...

was a major disaster for Nixon, eroding his political support in public opinion and in Washington. However he did manage to secure large-scale funding for South Vietnam, much of which was wasted.

The United States withdrew its troops from Vietnam before the Paris Peace Accords

Paris Peace Accords

The Paris Peace Accords of 1973 intended to establish peace in Vietnam and an end to the Vietnam War, ended direct U.S. military involvement, and temporarily stopped the fighting between North and South Vietnam...

in 1973. In 1975 North Vietnam invaded with conventional army forces and quickly conquered the South. The U.S. was not involved in the fighting in 1975 but did evacuate many Vietnamese. Later nearly one million managed to flee to the U.S. as refugees. The impact on the U.S. was muted, with few political recriminations, but it did leave a "Vietnam Syndrome

Vietnam Syndrome

Vietnam Syndrome is a term used in the United States, in public political rhetoric and political analysis, to describe the perceived impact of the domestic controversy over the Vietnam War on US foreign policy after the end of that war in 1975....

" that cautioned against further military interventions anywhere else. Nixon (and his next two successors Ford and Carter) had dropped the containment policy and were not willing to intervene anywhere.

"Stagflation"

At the same time that President Johnson persuaded Congress to accept a tax cut in 1964, he was rapidly increasing spending for both domestic programs and for the war in Vietnam. The result was a major expansion of the money supply, resting largely on government deficits, which pushed prices rapidly upward. However, inflation also rested on the nation's steadily declining supremacy in international trade and, moreover, the decline in the global economic, geopolitical, commercial, technological, and cultural preponderance of the United States since the end of World War II. After 1945, the U.S. enjoyed easy access to raw materials and substantial markets for its goods abroad; the U.S. was responsible for around a third of the world's industrial output because of the devastation of postwar Europe. By the 1960s, not only were the industrialized nations now competing for increasingly scarce raw commodities, but Third WorldThird World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either capitalism and NATO , or communism and the Soviet Union...

suppliers were increasingly demanding higher prices. The automobile

Automobile

An automobile, autocar, motor car or car is a wheeled motor vehicle used for transporting passengers, which also carries its own engine or motor...

, steel

Steel

Steel is an alloy that consists mostly of iron and has a carbon content between 0.2% and 2.1% by weight, depending on the grade. Carbon is the most common alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used, such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten...

, and electronics industries were also beginning to face stiff competition in the U.S. domestic market by foreign producers who had more modern factories (as Europe and Japan's industrial bases had been largely rebuilt from the ground up following WWII) and higher-quality products.

Nixon promised to tackle sluggish growth and inflation, known as "stagflation

Stagflation

In economics, stagflation is a situation in which the inflation rate is high and the economic growth rate slows down and unemployment remains steadily high...

", through higher taxes and lower spending; this met stiff resistance in Congress. As a result, Nixon changed course and opted to control the currency; his appointees to the Federal Reserve sought a contraction of the money supply through higher interest rates but to little avail; the tight money policy did little to curb inflation. The cost of living rose a cumulative 15% during Nixon's first two years in office.