History of Solidarity

Encyclopedia

The history of Solidarity , a Polish non-governmental trade union, begins in August 1980, at the Lenin Shipyard

s (now Gdańsk Shipyards) at its founding by Lech Wałęsa

and others. In the early 1980s, it became the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country. Solidarity gave rise to a broad, non-violent, anti-communist social movement that, at its height, claimed some 10 million members. It is considered to have contributed greatly to the fall of communism.

Poland's communist government

attempted to destroy the union by instituting martial law

in 1981, followed by several years of political repression, but in the end was forced into negotiation. The Roundtable Talks

between the government and the Solidarity-led opposition resulted in semi-free elections in 1989. By the end of August 1989, a Solidarity-led coalition government had been formed, and, in December 1990, Wałęsa was elected

president. This was soon followed by the dismantling of the communist governmental system and by Poland's transformation into a modern democratic state. Solidarity's early survival represented a break in the hard-line stance of the communist Polish United Workers' Party

(PZPR), and was an unprecedented event; not only for the People's Republic of Poland

—a satellite

of the USSR ruled by a one-party

communist regime

—but for the whole of the Eastern bloc

. Solidarity's example led to the spread of anti-communist ideas and movements throughout the Eastern Bloc, weakening communist governments. This process later culminated in the Revolutions of 1989

.

In the 1990s, Solidarity's influence on Poland's political scene

In the 1990s, Solidarity's influence on Poland's political scene

waned. A political arm of the "Solidarity" movement, Solidarity Electoral Action (AWS), was founded in 1996 and would win the Polish parliamentary elections in 1997

, only to lose the subsequent 2001 elections

. Thereafter, Solidarity had little influence as a political party, though it did become the largest trade union in Poland.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the initial success of Solidarity in particular, and of dissident movements in general, was fed by a deepening crisis within Soviet-incluenced societies. There was declining morale, worsening economic conditions (a shortage economy

In the 1970s and 1980s, the initial success of Solidarity in particular, and of dissident movements in general, was fed by a deepening crisis within Soviet-incluenced societies. There was declining morale, worsening economic conditions (a shortage economy

), and growing stress from the Cold War

. After a brief boom period, from 1975 the policies of the Polish government, led by Party First Secretary Edward Gierek

, precipitated a slide into increasing depression, as foreign debt mounted. In June 1976, the first workers' strikes

took place, involving violent incidents at factories in Płock, Radom

and Ursus

. When these incidents were quelled by the government, the worker's movement received support from intellectual dissidents

, many of them associated with the Committee for Defense of the Workers

, formed in 1976. The following year, KOR was renamed the Committee for Social Self-defence (KSS-KOR).

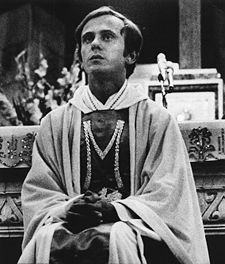

On October 16, 1978, the Bishop of Kraków, Karol Wojtyła, was elected Pope John Paul II

. A year later, during his first pilgrimage to Poland, his masses were attended by millions of his countrymen. The Pope called for the respecting of nation

al and religious

traditions and advocated for freedom and human rights, while denouncing violence. To many Poles, he represented a spiritual and moral force that could be set against brute material forces; he was a bellwether

of change, and became an important symbol—and supporter—of changes to come.

's government, facing economic crisis, decided to raise prices while slowing the growth of wages. At once there ensued a wave of strikes and factory occupations, with the biggest strikes

taking place in the area of Lublin

. The first strike started on July 8, 1980 in the State Aviation Works

in Świdnik

. Although the strike movement had no coordinating center, the workers had developed an information network to spread news of their struggle. A "dissident" group, the Workers' Defence Committee

(KOR), which had originally been set up in 1976 to organize aid for victimized workers, attracted small groups of working-class militants in major industrial centers. At the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk

, the firing of Anna Walentynowicz

, a popular crane operator and activist, galvanized the outraged workers into action.

On August 14, the shipyard workers began their strike, organized by the Free Trade Unions of the Coast

(Wolne Związki Zawodowe Wybrzeża). The workers were led by electrician Lech Wałęsa

, a former shipyard worker who had been dismissed in 1976, and who arrived at the shipyard late in the morning of August 14. The strike committee demanded the rehiring of Walentynowicz and Wałęsa, as well as the according of respect to workers' rights and other social concerns. In addition, they called for the raising of a monument to the shipyard workers

who had been killed in 1970 and for the legalization of independent trade unions.

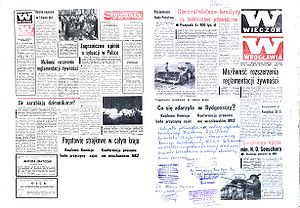

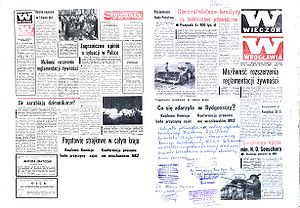

The Polish government enforced censorship, and official media said little about the "sporadic labor disturbances in Gdańsk"; as a further precaution, all phone connections between the coast and the rest of Poland were soon cut. Nonetheless, the government failed to contain the information: a spreading wave of samizdat

The Polish government enforced censorship, and official media said little about the "sporadic labor disturbances in Gdańsk"; as a further precaution, all phone connections between the coast and the rest of Poland were soon cut. Nonetheless, the government failed to contain the information: a spreading wave of samizdat

s , including Robotnik (The Worker), and grapevine gossip

, along with Radio Free Europe

broadcasts that penetrated the Iron Curtain

, ensured that the ideas of the emerging Solidarity movement quickly spread.

On August 16, delegations from other strike committees arrived at the shipyard. Delegates (Bogdan Lis

, Andrzej Gwiazda

and others) together with shipyard strikers agreed to create an Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee

(Międzyzakładowy Komitet Strajkowy, or MKS). On August 17 a priest, Henryk Jankowski

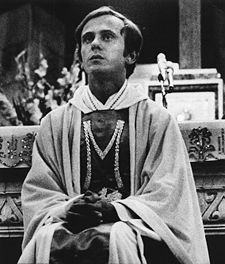

, performed a mass outside the shipyard's gate, at which 21 demands of the MKS

were put forward. The list went beyond purely local matters, beginning with a demand for new, independent trade unions and going on to call for a relaxation of the censorship

, a right to strike, new rights for the Church, the freeing of political prisoners, and improvements in the national health service.

Next day, a delegation of KOR intelligentsia

, including Tadeusz Mazowiecki

, arrived to offer their assistance with negotiations. A bibuła news-sheet, Solidarność, produced on the shipyard's printing press

with KOR assistance, reached a daily print run of 30,000 copies. Meanwhile, Jacek Kaczmarski

's protest song

, Mury

(Walls), gained popularity with the workers.

On August 18, the Szczecin Shipyard

joined the strike, under the leadership of Marian Jurczyk

. A tidal wave of strikes swept the coast, closing ports and bringing the economy to a halt. With KOR assistance and support from many intellectuals, workers occupying factories, mines and shipyards across Poland joined forces. Within days, over 200 factories and enterprises had joined the strike committee. By August 21, most of Poland was affected by the strikes, from coastal shipyards to the mines of the Upper Silesian Industrial Area (in Upper Silesia, the city of Jastrzębie-Zdrój became center of the strikes, with a separate committee organized there). More and more new unions were formed, and joined the federation.

Thanks to popular support within Poland, as well as to international support and media coverage, the Gdańsk workers held out until the government gave in to their demands. On August 21 a Governmental Commission (Komisja Rządowa) including Mieczysław Jagielski arrived in Gdańsk, and another one with Kazimierz Barcikowski

was dispatched to Szczecin. On August 30 and 31, and on September 3, representatives of the workers and the government signed an agreement ratifying many of the workers' demands, including the right to strike. This agreement came to be known as the August or Gdańsk agreement

(Porozumienia sierpniowe). Another agreement was signed in Jastrzębie-Zdrój on September 3. It was called the Jastrzębie agreement (Porozumienia jastrzebskie) and as such is regarded as part of the Gdańsk agreement. Though concerned with labor-union matters, the agreement enabled citizens to introduce democratic changes within the communist political structure and was regarded as a first step toward dismantling the Party's monopoly of power. The workers' main concerns were the establishment of a labor union independent of communist-party control, and recognition of a legal right to strike. Workers’ needs would now receive clear representation. Another consequence of the Gdańsk Agreement was the replacement, in September 1980, of Edward Gierek by Stanisław Kania as Party First Secretary.

, and its famous logo

was conceived by Jerzy Janiszewski

, designer of many Solidarity-related posters. The new union's supreme powers were vested in a legislative body

, the Convention of Delegates (Zjazd Delegatów). The executive branch

was the National Coordinating Commission

(Krajowa Komisja Porozumiewawcza), later renamed the National Commission (Komisja Krajowa). The Union had a regional structure, comprising 38 regions (region) and two districts (okręg). On December 16, 1980, the Monument to Fallen Shipyard Workers

was unveiled in Gdansk, and on June 28, 1981, another monument was unveiled in Poznan, which commemorated the Poznań 1956 protests

. On January 15, 1981, a Solidarity delegation, including Lech Wałęsa, met in Rome with Pope John Paul II

. From September 5 to 10, and from September 26 to October 7, Solidarity's first national congress was held, and Lech Wałęsa was elected its president. Last accord of the congress was adoption of republican

program "Self-governing Republic".

Meanwhile Solidarity had been transforming itself from a trade union into a social movement or more specifically, a revolutionary movement

Meanwhile Solidarity had been transforming itself from a trade union into a social movement or more specifically, a revolutionary movement

. Over the 500 days following the Gdańsk Agreement, 9–10 million workers, intellectuals and students joined it or its suborganizations, such as the Independent Student Union (Niezależne Zrzeszenie Studentów, created in September 1980), the Independent Farmers' Trade Union (NSZZ Rolników Indywidualnych "Solidarność", created in May 1981) and the Independent Craftsmen's Trade Union. It was the only time in recorded history that a quarter of a country's population (some 80% of the total Polish work force) had voluntarily joined a single organization. "History has taught us that there is no bread without freedom," the Solidarity program stated a year later. "What we had in mind was not only bread, butter and sausages, but also justice, democracy, truth, legality, human dignity, freedom of convictions, and the repair of the republic." Tygodnik Solidarność

, a Solidarity-published newspaper, was started in April 1981.

Using strikes and other protest actions, Solidarity sought to force a change in government policies. At the same time, it was careful never to use force or violence, so as to avoid giving the government any excuse to bring security forces into play. After 27 Bydgoszcz Solidarity members, including Jan Rulewski

, were beaten up

on March 19, a four-hour warning strike on March 27

, involving around twelve million people, paralyzed the country. This was the largest strike in the history of the Eastern bloc

, and it forced the government to promise an investigation into the beatings. This concession, and Wałęsa's agreement to defer further strikes, proved a setback to the movement, as the euphoria that had swept Polish society subsided. Nonetheless the Polish communist party—the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR)—had lost its total control over society.

Yet while Solidarity was ready to take up negotiations with the government, the Polish communists were unsure what to do, as they issued empty declarations and bided their time. Against the background of a deteriorating communist shortage economy and unwillingness to negotiate seriously with Solidarity, it became increasingly clear that the Communist government would eventually have to suppress the Solidarity movement as the only way out of the impasse, or face a truly revolutionary situation. The atmosphere was increasingly tense, with various local chapters conducting a growing number of uncoordinated strikes as well as street protests, such as the Summer 1981 hunger demonstrations in Poland

, in response to the worsening economic situation. On December 3, 1981, Solidarity announced that a 24-hour strike would be held if the government were granted additional powers to suppress dissent, and that a general strike would be declared if those powers were used.

, the Polish government was under increasing pressure from the Soviet Union to take action and strengthen its position. Stanisław Kania was viewed by Moscow as too independent, and on October 18, 1981, the Party Central Committee put him in the minority. Kania lost his post as First Secretary, and was replaced by Prime Minister (and Minister of Defence) Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski

, who adopted a strong-arm policy.

On December 13, 1981, Jaruzelski began a crack-down on Solidarity, declaring martial law

and creating a Military Council of National Salvation

(Wojskowa Rada Ocalenia Narodowego, or WRON). Solidarity's leaders, gathered at Gdańsk

, were arrested and isolated in facilities guarded by the Security Service (Służba Bezpieczeństwa or SB), and some 5,000 Solidarity supporters were arrested in the middle of the night. Censorship was expanded, and military forces appeared on the streets. A couple of hundred strikes and occupations occurred, chiefly at the largest plants and at several Silesia

n coal mines, but were broken by ZOMO

paramilitary riot police. One of the largest demonstrations, on December 16, 1981, took place at the Wujek Coal Mine, where government forces opened fire on demonstrators, killing 9 and seriously injuring 22. The next day, during protests at Gdańsk

, government forces again fired at demonstrators, killing 1 and injuring 2. By December 28, 1981, strikes had ceased, and Solidarity appeared crippled. The last strike in the 1981 Poland, which ended on December 28, took place in the Piast coal mine in the Upper Silesian town of Bieruń

. It was the longest underground strike in the history of Poland, lasting 14 days. Some 2000 miners began it on December 14, going 650 meters underground. Out of the initial 2000, half remained until the last day. Starving, they gave up after military authorities promised they would not be prosecuted. On October 8, 1982, Solidarity was banned.

The range of support for the Solidarity was unique: no other movement in the world was supported by Ronald Reagan

and Santiago Carrillo

, Enrico Berlinguer

and the Pope, Margaret Thatcher

and Tony Benn

, peace campaigners and NATO spokesman, Christians and Western communists, conservatives, liberals and socialists. The international community

outside the Iron Curtain

condemned Jaruzelski's actions and declared support for Solidarity; dedicated organizations were formed for that purpose (like Polish Solidarity Campaign

in Great Britain). US President Ronald Reagan imposed economic sanctions

on Poland, which eventually would force the Polish government into liberalizing its policies. Meanwhile the CIA together with the Catholic Church and various Western trade unions such as the AFL-CIO

provided funds, equipment and advice to the Solidarity underground. The political alliance of Reagan and the Pope would prove important to the future of Solidarity. The Polish public also supported what was left of Solidarity; a major medium for demonstrating support of Solidarity became masses held by priests such as Jerzy Popiełuszko.

Besides the communist authorities, Solidarity was also opposed by some of the Polish (emigré) radical right, believing Solidarity or KOR to be disguised communist groups, dominated by Jewish Trotskyite Zionists.

In July 1983, martial law was formally lifted, though many heightened controls on civil liberties and political life, as well as food rationing, remained in place through the mid-to-late 1980s.

Almost immediately after the legal Solidarity leadership had been arrested, underground structures began to arise. On April 12, 1982, Radio Solidarity

Almost immediately after the legal Solidarity leadership had been arrested, underground structures began to arise. On April 12, 1982, Radio Solidarity

began broadcasting. On April 22, Zbigniew Bujak

, Bogdan Lis

, Władysław Frasyniuk and Władysław Hardek created an Interim Coordinating Commission (Tymczasowa Komisja Koordynacyjna) to serve as an underground leadership for Solidarity. On May 6 another underground Solidarity organization, an NSSZ "S" Regional Coordinating Commission (Regionalna Komisja Koordynacyjna NSZZ "S"), was created by Bogdan Borusewicz

, Aleksander Hall

, Stanisław Jarosz, Bogdan Lis

and Marian Świtek. June 1982 saw the creation of a Fighting Solidarity

(Solidarność Walcząca) organization.

Throughout the mid-1980s, Solidarity persevered as an exclusively underground organization. Its activists were dogged by the Security Service (SB), but managed to strike back: on May 1, 1982, a series of anti-government protests brought out thousands of participants—several dozen thousand in Kraków, Warsaw and Gdańsk. On May 3 more protests took place, during celebrations of the Constitution of May 3, 1791

. On that day, communist secret services killed four demonstrators – three in Warsaw and one in Wrocław.

Another wave of demonstrations occurred on August 31, 1982, on the first anniversary of the Gdańsk Agreement (see August 31, 1982 demonstrations in Poland

). Altogether, on that day six demonstrators were killed – three in Lubin

, one in Kielce

, one in Wrocław and one in Gdańsk. Another person was killed on the next day, during a demonstration in Częstochowa

. Further strikes occurred at Gdańsk and Nowa Huta between October 11 and 13. In Nowa Huta, a 20-year old student Bogdan Wlosik was shot by a secret service officer.

On November 14, 1982, Wałęsa

On November 14, 1982, Wałęsa

was released. However on December 9 the SB carried out a large anti-Solidarity operation, arresting over 10,000 activists. On December 27 Solidarity's assets were transferred by the authorities to a pro-government trade union, the All-Poland Alliance of Trade Unions (Ogólnopolskie Porozumienie Związków Zawodowych, or OPZZ). Yet Solidarity was far from broken: by early 1983 the underground had over 70,000 members, whose activities included publishing over 500 underground newspapers. In the first half of 1983 street protests were frequent; on May 1, two persons were killed in Kraków and one in Wrocław. Two days later, two additional demonstrators were killed in Warsaw.

On July 22, 1983, martial law was lifted, and amnesty was granted to many imprisoned Solidarity members, who were released. On October 5, Wałęsa was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

. The Polish government, however, refused to issue him a passport to travel to Oslo

; Wałęsa's prize was accepted on his behalf by his wife. It later transpired that the SB had prepared bogus documents, accusing Wałęsa of immoral and illegal activities that had been given to the Nobel committee in an attempt to derail his nomination.

On October 19, 1984, three agents of the Ministry of Internal Security murdered a popular pro-Solidarity priest, Jerzy Popiełuszko. As the facts emerged, thousands of people declared their solidarity with the murdered priest by attending his funeral, held on November 3, 1984. The government attempted to smooth over the situation by releasing thousands of political prisoner

s; a year later, however, there followed a new wave of arrests. Frasyniuk, Lis and Adam Michnik

, members of the "S" underground, were arrested on February 13, 1985, placed on a show trial

, and sentenced to several years' imprisonment.

On March 11, 1985, power in the Soviet Union was assumed by Mikhail Gorbachev

On March 11, 1985, power in the Soviet Union was assumed by Mikhail Gorbachev

, a leader who represented a new generation of Soviet party members. The worsening economic situation in the entire Eastern Bloc, including the Soviet Union, together with other factors, forced Gorbachev to carry out a number of reforms, not only in the field of economics (uskoreniye

) but in the political and social realms (glasnost

and perestroika

). Gorbachev's policies soon caused a corresponding shift in the policies of Soviet satellites, including the People's Republic of Poland

.

On September 11, 1986, 225 Polish political prisoners were released—the last of those connected with Solidarity, and arrested during the previous years. Following amnesty on September 30, Wałęsa created the first public, legal Solidarity entity since the declaration of martial law—the Temporary Council of NSZZ Solidarność (Tymczasowa Rada NSZZ Solidarność)—with Bogdan Borusewicz

, Zbigniew Bujak

, Władysław Frasyniuk, Tadeusz Janusz Jedynak, Bogdan Lis

, Janusz Pałubicki and Józef Pinior

. Soon afterwards, the new Council was admitted to the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions

. Many local Solidarity chapters now broke their cover throughout Poland, and on October 25, 1987, the National Executive Committee (Solidarity)|National Executive Committee of NSZZ Solidarność (Krajowa Komisja Wykonawcza NSZZ Solidarność) was created. Nonetheless, Solidarity members and activists continued to be persecuted and discriminated, if less so than during the early 1980s. In the late 1980s, a rift between Wałęsa's faction and a more radical Fighting Solidarity

grew as the former wanted to negotiate with the government, while the latter planned for an anti-communist revolution.

By 1988, Poland's economy was in worse condition than it had been eight years earlier. International sanctions, combined with the government's unwillingness to introduce reforms, intensified the old problems. Inefficient government-run planned-economy enterprises

wasted labor

and resources

, producing substandard goods for which there was little demand

. Polish exports were low, both because of the sanctions and because the goods were as unattractive abroad as they were at home. Foreign debt and inflation

mounted. There were no funds to modernize factories, and the promised "market socialism

" materialized as a shortage economy

characterized by long queues and empty shelves. Reforms introduced by Jaruzelski and Mieczysław Rakowski came too little and too late, especially as changes in the Soviet Union had bolstered the public's expectation that change must come, and the Soviets ceased their efforts to prop up Poland's failing regime.

In February 1988, the government hiked food prices by 40%. On April 21, a new wave of strikes hit the country. On May 2, workers at the Gdańsk Shipyard went on strike. That strike was broken by the government between May 5 and May 10, but only temporarily: on August 15, a new strike took place at the "July Manifesto" mine in Jastrzębie Zdrój

. By August 20 the strike had spread to many other mines, and on August 22 the Gdańsk Shipyard joined the strike. Poland's communist government then decided to negotiate.

On August 26, Czesław Kiszczak, the Minister of Internal Affairs, declared on television that the government was willing to negotiate, and five days later he met with Wałęsa. The strikes ended the following day, and on November 30, during a televised debate between Wałęsa and Alfred Miodowicz

On August 26, Czesław Kiszczak, the Minister of Internal Affairs, declared on television that the government was willing to negotiate, and five days later he met with Wałęsa. The strikes ended the following day, and on November 30, during a televised debate between Wałęsa and Alfred Miodowicz

(leader of the pro-government trade union, the All-Poland Alliance of Trade Unions), Wałęsa scored a public-relations victory.

On December 18, a hundred-member Citizens' Committee (Komitet Obywatelski) was formed within Solidarity. It comprised several sections, each responsible for presenting a specific aspect of opposition demands to the government. Wałęsa and the majority of Solidarity leaders supported negotiation, while a minority wanted an anticommunist revolution. Under Wałęsa's leadership, Solidarity decided to pursue a peaceful solution, and the pro-violence faction never attained any substantial power, nor did it take any action.

On January 27, 1989, in a meeting between Wałęsa and Kiszczak, a list was drawn up of members of the main negotiating teams. The conference that began on February 6 would be known as the Polish Round Table Talks

. The 56 participants included 20 from "S", 6 from OPZZ, 14 from the PZPR, 14 "independent authorities", and two priests. The Polish Round Table Talks took place in Warsaw from February 6 to April 4, 1989. The Communists, led by Gen. Jaruzelski, hoped to co-opt prominent opposition leaders into the ruling group without making major changes in the structure of political power. Solidarity, while hopeful, did not anticipate major changes. In fact, the talks would radically alter the shape of the Polish government and society.

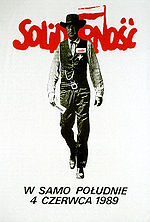

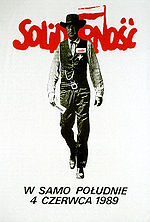

On April 17, 1989, Solidarity was legalized, and its membership soon reached 1.5 million. The Solidarity Citizens' Committee

(Komitet Obywatelski "Solidarność") was given permission to field candidates in the upcoming elections. Election law

allowed Solidarity to put forward candidates for only 35% of the seats in the Sejm

, but there were no restrictions in regard to Senat

candidates. Agitation and propaganda continued legally up to election day. Despite its shortage of resources, Solidarity managed to carry on an electoral campaign. On May 8, the first issue of a new pro-Solidarity newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza

(The Election Gazette), was published. Posters of Wałęsa supporting various candidates, appeared throughout the country.

Pre-election public-opinion polls had promised victory to the communists. Thus the total defeat of the PZPR and its satellite parties came as a surprise to all involved: after the first round of elections, it became evident that Solidarity had fared extremely well, capturing 160 of 161 contested Sejm seats, and 92 of 100 Senate seats. After the second round, it had won virtually every seat—all 161 in the Sejm, and 99 in the Senate.

Pre-election public-opinion polls had promised victory to the communists. Thus the total defeat of the PZPR and its satellite parties came as a surprise to all involved: after the first round of elections, it became evident that Solidarity had fared extremely well, capturing 160 of 161 contested Sejm seats, and 92 of 100 Senate seats. After the second round, it had won virtually every seat—all 161 in the Sejm, and 99 in the Senate.

These elections, in which anti-communist candidates won a striking victory, inaugurated a series of peaceful anti-communist revolutions

in Central

and Eastern Europe

that eventually culminated in the fall of communism.

The new Contract Sejm

, named for the agreement that had been reached by the communist party and the Solidarity movement during the Polish Round Table Talks

, would be dominated by Solidarity. As agreed beforehand, Wojciech Jaruzelski

was elected president. However, the communist candidate for Prime Minister, Czesław Kiszczak, who replaced Mieczysław Rakowski, failed to gain enough support to form a government.

On June 23, a Solidarity Citizens' Parliamentary Club (Obywatelski Klub Parliamentarny "Solidarność") was formed, led by Bronisław Geremek. It formed a coalition

with two ex-satellite parties of the PZPR—ZSL and SD

—which had now chosen to "rebel" against the PZPR, which found itself in the minority. On August 24, the Sejm elected Tadeusz Mazowiecki

, a Solidarity representative, to be Prime Minister of Poland. Not only was he a first non-communist Polish Prime Minister since 1945, he became the first non-Communist prime minister in Eastern Europe for nearly 40 years. In his speech he talked about the "thick line" (Gruba kreska

) which would separate his government from the communist past By the end of August 1989, a Solidarity-led coalition government

had been formed.

in the history of Poland

and in the history of Solidarity. Having defeated the communist government, Solidarity found itself in a role it was much less prepared for — that of a political party — and soon began to lose popularity. Conflicts among Solidarity factions intensified. Wałęsa was elected Solidarity chairman, but support for him could be seen to be crumbling. One of his main opponents, Władysław Frasyniuk, withdrew from elections altogether. In September 1990, Wałęsa declared that Gazeta Wyborcza

had no right to use the Solidarity logo

.

Later that month, Wałęsa announced his intent to run for president of Poland

. In December 1990, he was elected president. He resigned his Solidarity post and became the first president of Poland ever to be elected by popular vote.

Next year, in February 1991, Marian Krzaklewski

Next year, in February 1991, Marian Krzaklewski

was elected the leader of Solidarity. President Wałęsa's vision and that of the new Solidarity leadership were diverging. Far from supporting Wałęsa, Solidarity was becoming increasingly critical of the government, and decided to create its own political party for action in the upcoming 1991 parliamentary elections

.

The 1991 elections were characterized by a large number of competing parties, many claiming the legacy of anti-communism, and the Solidarity party garnered only 5% of the votes.

On January 13, 1992, Solidarity declared its first strike against the democratically elected government: a one-hour strike against a proposal to raise energy prices. Another, two-hour strike took place on December 14. On May 19, 1993, Solidarity deputies proposed a no-confidence motion

—which passed—against the government of Prime Minister Hanna Suchocka

. President Wałęsa declined to accept the prime minister's resignation, and dismissed the parliament.

It was in the ensuing 1993 parliamentary elections

It was in the ensuing 1993 parliamentary elections

that it became evident how much Solidarity's support had eroded in the previous three years. Even though some Solidarity deputies sought to assume a more left-wing stance and to distance themselves from the right-wing government, Solidarity remained identified in the public mind with that government. Hence it suffered from the growing disillusionment of the populace, as the transition from a communist to a capitalist system failed to generate instant wealth and raise Poland's living standards to those in the West, and the government's financial "shock therapy

" (the Balcerowicz Plan) generated much opposition.

In the elections, Solidarity received only 4.9% of the votes, 0.1% less than the 5% required in order to enter parliament (Solidarity still had 9 senators, 2 fewer than in the previous Senate

). The victorious party was the Democratic Left Alliance

(Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej or SLD), a post-communist left-wing party.

Solidarity now joined forces with its erstwhile enemy, the All-Poland Alliance of Trade Unions (OPZZ), and some protests were organized by both trade unions. The following year, Solidarity organized many strikes over the state of the Polish mining industry. In 1995, a demonstration before the Polish parliament was broken up by the police (now again known as policja

) using batons and water guns. Nonetheless, Solidarity decided to support Wałęsa in the 1995 presidential elections

.

In a second major defeat for the Polish right wing, the elections were won by an SLD candidate, Aleksander Kwaśniewski

, who received 51.72% of votes. A Solidarity call for new elections went unheeded, but the Sejm

still managed to pass a resolution condemning the 1981 martial law (despite the SLD voting against). Meanwhile the left-wing OPZZ trade union had acquired 2.5 million members, twice as many as the contemporary Solidarity (with 1.3 million).

In June 1996, Solidarity Electoral Action

In June 1996, Solidarity Electoral Action

(Akcja Wyborcza Solidarność) was founded as a coalition of over 30 right-wing parties, uniting liberal

, conservative

and Christian-democratic forces. As the public became disillusioned with the SLD and its allies, AWS was victorious in the 1997 parliamentary elections

. Jerzy Buzek

became the new prime minister.

However, controversies over domestic reforms, Poland's 1999 entry into NATO, and the accession process to the European Union, combined with AWS fights with its political allies (the Freedom Union

—Unia Wolności) and infighting within AWS itself, as well as corruption

(reflected in the infamous "TKM

" slogan), eventually resulted in the loss of much public support. AWS leader Marian Krzaklewski

lost the 2000 presidential election

, and in the 2001 parliamentary elections

AWS failed to elect a single deputy to the parliament. After this debacle, Krzaklewski was replaced by Janusz Śniadek

(in 2002) but the union decided to distance itself from politics.

In 2006, Solidarity had some 1.5 million members making it the largest trade union in Poland. Its mission statement

declares that Solidarity, "basing its activities on Christian ethics

and Catholic social teachings, works to protect workers' interests and to fulfill their material, social and cultural aspirations."

Gdansk Shipyard

Gdańsk Shipyard is a large Polish shipyard, located in the city of Gdańsk. The yard gained international fame when Solidarity was founded there in September 1980...

s (now Gdańsk Shipyards) at its founding by Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa is a Polish politician, trade-union organizer, and human-rights activist. A charismatic leader, he co-founded Solidarity , the Soviet bloc's first independent trade union, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983, and served as President of Poland between 1990 and 95.Wałęsa was an electrician...

and others. In the early 1980s, it became the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country. Solidarity gave rise to a broad, non-violent, anti-communist social movement that, at its height, claimed some 10 million members. It is considered to have contributed greatly to the fall of communism.

Poland's communist government

People's Republic of Poland

The People's Republic of Poland was the official name of Poland from 1952 to 1990. Although the Soviet Union took control of the country immediately after the liberation from Nazi Germany in 1944, the name of the state was not changed until eight years later...

attempted to destroy the union by instituting martial law

Martial law in Poland

Martial law in Poland refers to the period of time from December 13, 1981 to July 22, 1983, when the authoritarian government of the People's Republic of Poland drastically restricted normal life by introducing martial law in an attempt to crush political opposition to it. Thousands of opposition...

in 1981, followed by several years of political repression, but in the end was forced into negotiation. The Roundtable Talks

Polish Round Table Agreement

The Polish Round Table Talks took place in Warsaw, Poland from February 6 to April 4, 1989. The government initiated the discussion with the banned trade union Solidarność and other opposition groups in an attempt to defuse growing social unrest.-History:...

between the government and the Solidarity-led opposition resulted in semi-free elections in 1989. By the end of August 1989, a Solidarity-led coalition government had been formed, and, in December 1990, Wałęsa was elected

Polish presidential election, 1990

The 1990 Presidential elections were held in Poland on Sunday, November 25 , and Sunday, December 9 . These were the first direct presidential elections in the history of Poland. Before World War II, presidents were elected by the Sejm, but the Sejm was abolished in 1952. The leader of the...

president. This was soon followed by the dismantling of the communist governmental system and by Poland's transformation into a modern democratic state. Solidarity's early survival represented a break in the hard-line stance of the communist Polish United Workers' Party

Polish United Workers' Party

The Polish United Workers' Party was the Communist party which governed the People's Republic of Poland from 1948 to 1989. Ideologically it was based on the theories of Marxism-Leninism.- The Party's Program and Goals :...

(PZPR), and was an unprecedented event; not only for the People's Republic of Poland

People's Republic of Poland

The People's Republic of Poland was the official name of Poland from 1952 to 1990. Although the Soviet Union took control of the country immediately after the liberation from Nazi Germany in 1944, the name of the state was not changed until eight years later...

—a satellite

Satellite state

A satellite state is a political term that refers to a country that is formally independent, but under heavy political and economic influence or control by another country...

of the USSR ruled by a one-party

Single-party state

A single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a type of party system government in which a single political party forms the government and no other parties are permitted to run candidates for election...

communist regime

Communist state

A communist state is a state with a form of government characterized by single-party rule or dominant-party rule of a communist party and a professed allegiance to a Leninist or Marxist-Leninist communist ideology as the guiding principle of the state...

—but for the whole of the Eastern bloc

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

. Solidarity's example led to the spread of anti-communist ideas and movements throughout the Eastern Bloc, weakening communist governments. This process later culminated in the Revolutions of 1989

Revolutions of 1989

The Revolutions of 1989 were the revolutions which overthrew the communist regimes in various Central and Eastern European countries.The events began in Poland in 1989, and continued in Hungary, East Germany, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and...

.

Politics of Poland

The politics of Poland take place in the framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic, whereby the Prime Minister is the head of government of a multi-party system and the President is the head of state....

waned. A political arm of the "Solidarity" movement, Solidarity Electoral Action (AWS), was founded in 1996 and would win the Polish parliamentary elections in 1997

Polish parliamentary election, 1997

The Polish parliamentary election in 1997 to the Sejm and Senate of Poland was held on the 21 September. In the Sejm elections, 47.93% of citizens cast their votes, 96.12% of which were counted as valid...

, only to lose the subsequent 2001 elections

Polish parliamentary election, 2001

Polish parliamentary election in 2001 to Sejm and Senate of Poland were held on the 23rd September. In Sejm elections, 46.29% of citizens cast their votes, 96.01% of those were counted as valid...

. Thereafter, Solidarity had little influence as a political party, though it did become the largest trade union in Poland.

Pre–1980 roots

Shortage economy

Shortage economy is a term coined by the Hungarian economist, János Kornai. He used this term to criticize the old centrally-planned economies of the communist states of the Eastern Bloc...

), and growing stress from the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

. After a brief boom period, from 1975 the policies of the Polish government, led by Party First Secretary Edward Gierek

Edward Gierek

Edward Gierek was a Polish communist politician.He was born in Porąbka, outside of Sosnowiec. He lost his father to a mining accident in a pit at the age of four. His mother married again and emigrated to northern France, where he was raised. He joined the French Communist Party in 1931 and was...

, precipitated a slide into increasing depression, as foreign debt mounted. In June 1976, the first workers' strikes

June 1976 protests

June 1976 is the name of a series of protests and demonstrations in People's Republic of Poland. The protests took place after Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz revealed the plan for a sudden increase in the price of many basic commodities, particularly foodstuffs...

took place, involving violent incidents at factories in Płock, Radom

Radom

Radom is a city in central Poland with 223,397 inhabitants . It is located on the Mleczna River in the Masovian Voivodeship , having previously been the capital of Radom Voivodeship ; 100 km south of Poland's capital, Warsaw.It is home to the biennial Radom Air Show, the largest and...

and Ursus

Ursus (district in Warsaw)

Ursus is a district of Warsaw, one of the 18 such units into which the city is divided. Between 1952 and 1977 it a was separate city, a legacy of which are Ursus' poor road connections with the Warsaw city centre...

. When these incidents were quelled by the government, the worker's movement received support from intellectual dissidents

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

, many of them associated with the Committee for Defense of the Workers

Workers' Defence Committee

The Workers’ Defense Committee was a Polish civil society group that emerged under communist rule to give aid to prisoners & their families after the June 1976 protests & government crackdown...

, formed in 1976. The following year, KOR was renamed the Committee for Social Self-defence (KSS-KOR).

On October 16, 1978, the Bishop of Kraków, Karol Wojtyła, was elected Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II

Blessed Pope John Paul II , born Karol Józef Wojtyła , reigned as Pope of the Catholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at of age. His was the second-longest documented pontificate, which lasted ; only Pope Pius IX ...

. A year later, during his first pilgrimage to Poland, his masses were attended by millions of his countrymen. The Pope called for the respecting of nation

Nation

A nation may refer to a community of people who share a common language, culture, ethnicity, descent, and/or history. In this definition, a nation has no physical borders. However, it can also refer to people who share a common territory and government irrespective of their ethnic make-up...

al and religious

Religion

Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that establishes symbols that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to...

traditions and advocated for freedom and human rights, while denouncing violence. To many Poles, he represented a spiritual and moral force that could be set against brute material forces; he was a bellwether

Bellwether

A bellwether is any entity in a given arena that serves to create or influence trends or to presage future happenings.The term is derived from the Middle English bellewether and refers to the practice of placing a bell around the neck of a castrated ram leading his flock of sheep.The movements of...

of change, and became an important symbol—and supporter—of changes to come.

Early strikes (1980)

Strikes did not occur merely due to problems that had emerged shortly before the labor unrest, but due to governmental and economic difficulties spanning more than a decade. In July 1980, Edward GierekEdward Gierek

Edward Gierek was a Polish communist politician.He was born in Porąbka, outside of Sosnowiec. He lost his father to a mining accident in a pit at the age of four. His mother married again and emigrated to northern France, where he was raised. He joined the French Communist Party in 1931 and was...

's government, facing economic crisis, decided to raise prices while slowing the growth of wages. At once there ensued a wave of strikes and factory occupations, with the biggest strikes

Lublin 1980 strikes

The Lublin 1980 strikes were the series of workers’ strikes in the area of the eastern city of Lublin , demanding better salaries and lower prices of food products. They began on July 8, 1980, at the State Aviation Works in Świdnik, a town located on the outskirts of Lublin...

taking place in the area of Lublin

Lublin

Lublin is the ninth largest city in Poland. It is the capital of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 350,392 . Lublin is also the largest Polish city east of the Vistula river...

. The first strike started on July 8, 1980 in the State Aviation Works

PZL

PZL was the main Polish aerospace manufacturer of the interwar period, based in Warsaw, functioning in 1928-1939...

in Świdnik

Swidnik

Świdnik is a town in eastern Poland with 42,797 inhabitants , situated in the Lublin Voivodeship, very near the city of Lublin. It is the capital of Świdnik County.-History:The village of Świdnik is first mentioned in historical records from 1392...

. Although the strike movement had no coordinating center, the workers had developed an information network to spread news of their struggle. A "dissident" group, the Workers' Defence Committee

Workers' Defence Committee

The Workers’ Defense Committee was a Polish civil society group that emerged under communist rule to give aid to prisoners & their families after the June 1976 protests & government crackdown...

(KOR), which had originally been set up in 1976 to organize aid for victimized workers, attracted small groups of working-class militants in major industrial centers. At the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk

Gdansk

Gdańsk is a Polish city on the Baltic coast, at the centre of the country's fourth-largest metropolitan area.The city lies on the southern edge of Gdańsk Bay , in a conurbation with the city of Gdynia, spa town of Sopot, and suburban communities, which together form a metropolitan area called the...

, the firing of Anna Walentynowicz

Anna Walentynowicz

Anna Walentynowicz was a Polish free trade union activist. Her firing in August 1980 was the event that ignited the strike at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk that very quickly paralyzed the Baltic coast and a giant wave of strikes in Poland...

, a popular crane operator and activist, galvanized the outraged workers into action.

On August 14, the shipyard workers began their strike, organized by the Free Trade Unions of the Coast

Free Trade Unions of the Coast

Free Trade Unions of the Coast were a government-independent trade union in the People's Republic of Poland.This trade union was founded in Gdańsk on 29 April 1978 by Andrzej Gwiazda, Krzysztof Wyszkowski and Antoni Sokołowski...

(Wolne Związki Zawodowe Wybrzeża). The workers were led by electrician Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa is a Polish politician, trade-union organizer, and human-rights activist. A charismatic leader, he co-founded Solidarity , the Soviet bloc's first independent trade union, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983, and served as President of Poland between 1990 and 95.Wałęsa was an electrician...

, a former shipyard worker who had been dismissed in 1976, and who arrived at the shipyard late in the morning of August 14. The strike committee demanded the rehiring of Walentynowicz and Wałęsa, as well as the according of respect to workers' rights and other social concerns. In addition, they called for the raising of a monument to the shipyard workers

Monument to fallen Shipyard Workers

The Monument to the fallen Shipyard Workers 1970 was unveiled on 16 December 1980 near the entrance to what was then the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, Poland. It commemorates the 42 or more people killed during the Coastal cities events in December 1970...

who had been killed in 1970 and for the legalization of independent trade unions.

Samizdat

Samizdat was a key form of dissident activity across the Soviet bloc in which individuals reproduced censored publications by hand and passed the documents from reader to reader...

s , including Robotnik (The Worker), and grapevine gossip

Grapevine (gossip)

To hear something through the grapevine is to learn of something informally and unofficially by means of gossip and rumor.The usual implication is that the information was passed person to person by word of mouth, perhaps in a confidential manner among friends or colleagues. It can also imply an...

, along with Radio Free Europe

Radio Free Europe

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty is a broadcaster funded by the U.S. Congress that provides news, information, and analysis to countries in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Middle East "where the free flow of information is either banned by government authorities or not fully developed"...

broadcasts that penetrated the Iron Curtain

Iron Curtain

The concept of the Iron Curtain symbolized the ideological fighting and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1989...

, ensured that the ideas of the emerging Solidarity movement quickly spread.

On August 16, delegations from other strike committees arrived at the shipyard. Delegates (Bogdan Lis

Bogdan Lis

Bogdan Lis is a Polish politician, known for his involvement with the anti-communist Solidarity social movement.Born in Gdańsk in 1952, he worked in Port of Gdańsk and Elmor company. Between 1971 and 1972 he was imprisoned for his participation in the anti-governmental coastal cities protests...

, Andrzej Gwiazda

Andrzej Gwiazda

Andrzej Gwiazda in Gdańsk engineer and prominent opposition leader, who participated in Polish March 1968 Events and December 1970 Events; one of the founders of Free Trade Unions, Member of the Presiding Committee of the Strike at Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk in August 1980, Vice President of the...

and others) together with shipyard strikers agreed to create an Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee

Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee

Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee was an action strike committee formed in Gdańsk Shipyard, People's Republic of Poland on 16 August 1980...

(Międzyzakładowy Komitet Strajkowy, or MKS). On August 17 a priest, Henryk Jankowski

Henryk Jankowski

Father Henryk Jankowski was a Polish Roman Catholic priest. Member of Solidarity movement and one of the leading priests supporting that movement in opposition to the communist government in the 1980s, he was also a long serving provost of St. Bridget's church in Gdańsk...

, performed a mass outside the shipyard's gate, at which 21 demands of the MKS

21 demands of MKS

21 demands of MKS were a list of demands issued on 17 August 1980 by the Interfactory Strike Committee . The first demand was the right to create independent trade unions...

were put forward. The list went beyond purely local matters, beginning with a demand for new, independent trade unions and going on to call for a relaxation of the censorship

Censorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

, a right to strike, new rights for the Church, the freeing of political prisoners, and improvements in the national health service.

Next day, a delegation of KOR intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

, including Tadeusz Mazowiecki

Tadeusz Mazowiecki

Tadeusz Mazowiecki is a Polish author, journalist, philanthropist and Christian-democratic politician, formerly one of the leaders of the Solidarity movement, and the first non-communist prime minister in Central and Eastern Europe after World War II.-Biography:Mazowiecki comes from a Polish...

, arrived to offer their assistance with negotiations. A bibuła news-sheet, Solidarność, produced on the shipyard's printing press

Printing press

A printing press is a device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium , thereby transferring the ink...

with KOR assistance, reached a daily print run of 30,000 copies. Meanwhile, Jacek Kaczmarski

Jacek Kaczmarski

Jacek Kaczmarski was a Polish singer, songwriter, poet and author.Kaczmarski was a voice of the Solidarity trade union movement in 1980s Poland, for his commitment to a free Poland, independent of Soviet rule. His songs criticized the ruling communist regime and appealed to the tradition of...

's protest song

Protest song

A protest song is a song which is associated with a movement for social change and hence part of the broader category of topical songs . It may be folk, classical, or commercial in genre...

, Mury

Mury (song)

Mury was a sung poetry protest song written by Polish singer Jacek Kaczmarski in 1978. In People's Republic of Poland, in the early eighties of 20th century it became a symbol of the opposition to the communist regime...

(Walls), gained popularity with the workers.

On August 18, the Szczecin Shipyard

Szczecin Shipyard

Szczecin Shipyard or New Szczecin Shipyard was a shipyard in northwestern city of Szczecin, Poland. Formerly known as Stocznia Szczecińska Porta Holding S.A. or Stocznia im. Adolfa Warskiego. The shipyard specialized in the construction of container ships, chemicals transport ships, multi-purpose...

joined the strike, under the leadership of Marian Jurczyk

Marian Jurczyk

Marian Jurczyk is a Polish politician and Solidarity trade union activist.He was a Senator in the Polish Senate from 1997 to 2000, and Mayor of Szczecin from 18 November 1998 to 24 January 2000...

. A tidal wave of strikes swept the coast, closing ports and bringing the economy to a halt. With KOR assistance and support from many intellectuals, workers occupying factories, mines and shipyards across Poland joined forces. Within days, over 200 factories and enterprises had joined the strike committee. By August 21, most of Poland was affected by the strikes, from coastal shipyards to the mines of the Upper Silesian Industrial Area (in Upper Silesia, the city of Jastrzębie-Zdrój became center of the strikes, with a separate committee organized there). More and more new unions were formed, and joined the federation.

Thanks to popular support within Poland, as well as to international support and media coverage, the Gdańsk workers held out until the government gave in to their demands. On August 21 a Governmental Commission (Komisja Rządowa) including Mieczysław Jagielski arrived in Gdańsk, and another one with Kazimierz Barcikowski

Kazimierz Barcikowski

Kazimierz Barcikowski was a Polish politician. Member of Polish United Workers Party, served on the Central Committee of the Party and on Political Bureau. Among his other posts were those of deputy to Sejm and minister of agriculture. Head of government negotiations with striking workers in...

was dispatched to Szczecin. On August 30 and 31, and on September 3, representatives of the workers and the government signed an agreement ratifying many of the workers' demands, including the right to strike. This agreement came to be known as the August or Gdańsk agreement

Gdansk Agreement

The Gdańsk Agreement was an accord reached as a direct result of the strikes that took place in Gdańsk, Poland...

(Porozumienia sierpniowe). Another agreement was signed in Jastrzębie-Zdrój on September 3. It was called the Jastrzębie agreement (Porozumienia jastrzebskie) and as such is regarded as part of the Gdańsk agreement. Though concerned with labor-union matters, the agreement enabled citizens to introduce democratic changes within the communist political structure and was regarded as a first step toward dismantling the Party's monopoly of power. The workers' main concerns were the establishment of a labor union independent of communist-party control, and recognition of a legal right to strike. Workers’ needs would now receive clear representation. Another consequence of the Gdańsk Agreement was the replacement, in September 1980, of Edward Gierek by Stanisław Kania as Party First Secretary.

First Solidarity (1980–1981)

Encouraged by the success of the August strikes, on September 17 workers' representatives, including Lech Wałęsa, formed a nationwide labor union, Solidarity (Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy (NSZZ) "Solidarność"). It was the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country. Its name was suggested by Karol ModzelewskiKarol Modzelewski

Karol Modzelewski is a Polish historian, writer and politician.He is the adopted son of Zygmunt Modzelewski. Professor at the University of Wroclaw and the University of Warsaw, he was a member of the Polish United Workers Party but was expelled from it in 1964 for opposition to some policies of...

, and its famous logo

Solidarity logo

The Solidarity logo designed by Jerzy Janiszewski in 1980 is considered as an important example of Polish Poster School creations. The logo was awarded the Grand Prix of the Biennale of Posters, Katowice 1981. By this time it was already well known in Poland and became an internationally...

was conceived by Jerzy Janiszewski

Jerzy Janiszewski

Jerzy Janiszewski is a Polish artist, best known for designing the Solidarity logo in 1980.He received a diploma of Gdansk Academy of Fine Arts in 1976. His creations include logotypes, posters, scenogaphies and open-air installations....

, designer of many Solidarity-related posters. The new union's supreme powers were vested in a legislative body

Legislature

A legislature is a kind of deliberative assembly with the power to pass, amend, and repeal laws. The law created by a legislature is called legislation or statutory law. In addition to enacting laws, legislatures usually have exclusive authority to raise or lower taxes and adopt the budget and...

, the Convention of Delegates (Zjazd Delegatów). The executive branch

Executive (government)

Executive branch of Government is the part of government that has sole authority and responsibility for the daily administration of the state bureaucracy. The division of power into separate branches of government is central to the idea of the separation of powers.In many countries, the term...

was the National Coordinating Commission

National Coordinating Commission

National Coordinating Commission , later called the National Commission was the executive branch of the Solidarity trade union...

(Krajowa Komisja Porozumiewawcza), later renamed the National Commission (Komisja Krajowa). The Union had a regional structure, comprising 38 regions (region) and two districts (okręg). On December 16, 1980, the Monument to Fallen Shipyard Workers

Monument to fallen Shipyard Workers

The Monument to the fallen Shipyard Workers 1970 was unveiled on 16 December 1980 near the entrance to what was then the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, Poland. It commemorates the 42 or more people killed during the Coastal cities events in December 1970...

was unveiled in Gdansk, and on June 28, 1981, another monument was unveiled in Poznan, which commemorated the Poznań 1956 protests

Poznan 1956 protests

The Poznań 1956 protests, also known as Poznań 1956 uprising or Poznań June , were the first of several massive protests of the Polish people against the communist government of the People's Republic of Poland...

. On January 15, 1981, a Solidarity delegation, including Lech Wałęsa, met in Rome with Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II

Blessed Pope John Paul II , born Karol Józef Wojtyła , reigned as Pope of the Catholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at of age. His was the second-longest documented pontificate, which lasted ; only Pope Pius IX ...

. From September 5 to 10, and from September 26 to October 7, Solidarity's first national congress was held, and Lech Wałęsa was elected its president. Last accord of the congress was adoption of republican

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

program "Self-governing Republic".

Revolutionary movement

Revolutionary movement is a specific type of social movement dedicated to carrying out a revolution. Charles Tilly defines it as a social movement advancing exclusive competing claims to control of the state, or some segment of it. An example of a revolutionary movement is the Armenian...

. Over the 500 days following the Gdańsk Agreement, 9–10 million workers, intellectuals and students joined it or its suborganizations, such as the Independent Student Union (Niezależne Zrzeszenie Studentów, created in September 1980), the Independent Farmers' Trade Union (NSZZ Rolników Indywidualnych "Solidarność", created in May 1981) and the Independent Craftsmen's Trade Union. It was the only time in recorded history that a quarter of a country's population (some 80% of the total Polish work force) had voluntarily joined a single organization. "History has taught us that there is no bread without freedom," the Solidarity program stated a year later. "What we had in mind was not only bread, butter and sausages, but also justice, democracy, truth, legality, human dignity, freedom of convictions, and the repair of the republic." Tygodnik Solidarność

Tygodnik Solidarnosc

Tygodnik Solidarność is Polish conservative newspaper. Started and published by the Solidarity movement on 3 April 1981, it was banned by the People's Republic of Poland following the martial law declaration from 13 December 1981 and the thaw of 1989...

, a Solidarity-published newspaper, was started in April 1981.

Using strikes and other protest actions, Solidarity sought to force a change in government policies. At the same time, it was careful never to use force or violence, so as to avoid giving the government any excuse to bring security forces into play. After 27 Bydgoszcz Solidarity members, including Jan Rulewski

Jan Rulewski

Jan Rulewski is a Polish politician, activist of Solidarity; a Member of the Polish Sejm and a Senator .He was in charge of the Bydgoszcz region of Solidarity...

, were beaten up

Bydgoszcz events

Bydgoszcz events refers to a turning point in the early history of the Solidarity movement. Following the registration of the Solidarity by the communist authorities of Poland in 1980, the farmers were also pushing for creation of a separate trade union, independent from the official system of power...

on March 19, a four-hour warning strike on March 27

1981 warning strike in Poland

In the early spring of 1981, the quickly growing Solidarity movement faced one of the biggest challenges in its short history, when during the Bydgoszcz events, several members of Solidarity, including Jan Rulewski, Mariusz Łabentowicz and Roman Bartoszcze, were brutally "pacified" by the...

, involving around twelve million people, paralyzed the country. This was the largest strike in the history of the Eastern bloc

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

, and it forced the government to promise an investigation into the beatings. This concession, and Wałęsa's agreement to defer further strikes, proved a setback to the movement, as the euphoria that had swept Polish society subsided. Nonetheless the Polish communist party—the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR)—had lost its total control over society.

Yet while Solidarity was ready to take up negotiations with the government, the Polish communists were unsure what to do, as they issued empty declarations and bided their time. Against the background of a deteriorating communist shortage economy and unwillingness to negotiate seriously with Solidarity, it became increasingly clear that the Communist government would eventually have to suppress the Solidarity movement as the only way out of the impasse, or face a truly revolutionary situation. The atmosphere was increasingly tense, with various local chapters conducting a growing number of uncoordinated strikes as well as street protests, such as the Summer 1981 hunger demonstrations in Poland

Summer 1981 hunger demonstrations in Poland

In mid-1981, amid widespread economic crisis and food shortages, thousands of Poles, mainly women and their children, took part in several hunger demonstrations, organized in cities and towns across the country. The protests were peaceful, without rioting, and the biggest one took place on July 30,...

, in response to the worsening economic situation. On December 3, 1981, Solidarity announced that a 24-hour strike would be held if the government were granted additional powers to suppress dissent, and that a general strike would be declared if those powers were used.

Martial law (1981–83)

After the Gdańsk AgreementGdansk Agreement

The Gdańsk Agreement was an accord reached as a direct result of the strikes that took place in Gdańsk, Poland...

, the Polish government was under increasing pressure from the Soviet Union to take action and strengthen its position. Stanisław Kania was viewed by Moscow as too independent, and on October 18, 1981, the Party Central Committee put him in the minority. Kania lost his post as First Secretary, and was replaced by Prime Minister (and Minister of Defence) Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski is a retired Polish military officer and Communist politician. He was the last Communist leader of Poland from 1981 to 1989, Prime Minister from 1981 to 1985 and the country's head of state from 1985 to 1990. He was also the last commander-in-chief of the Polish People's...

, who adopted a strong-arm policy.

On December 13, 1981, Jaruzelski began a crack-down on Solidarity, declaring martial law

Martial law in Poland

Martial law in Poland refers to the period of time from December 13, 1981 to July 22, 1983, when the authoritarian government of the People's Republic of Poland drastically restricted normal life by introducing martial law in an attempt to crush political opposition to it. Thousands of opposition...

and creating a Military Council of National Salvation

Military Council of National Salvation

The Military Council of National Salvation was a military dictatorship administering the People's Republic of Poland during the period of the martial law in Poland ....

(Wojskowa Rada Ocalenia Narodowego, or WRON). Solidarity's leaders, gathered at Gdańsk

Gdansk

Gdańsk is a Polish city on the Baltic coast, at the centre of the country's fourth-largest metropolitan area.The city lies on the southern edge of Gdańsk Bay , in a conurbation with the city of Gdynia, spa town of Sopot, and suburban communities, which together form a metropolitan area called the...

, were arrested and isolated in facilities guarded by the Security Service (Służba Bezpieczeństwa or SB), and some 5,000 Solidarity supporters were arrested in the middle of the night. Censorship was expanded, and military forces appeared on the streets. A couple of hundred strikes and occupations occurred, chiefly at the largest plants and at several Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

n coal mines, but were broken by ZOMO

ZOMO

Zmotoryzowane Odwody Milicji Obywatelskiej , were paramilitary-police formations during the Communist Era, in the People's Republic of Poland...

paramilitary riot police. One of the largest demonstrations, on December 16, 1981, took place at the Wujek Coal Mine, where government forces opened fire on demonstrators, killing 9 and seriously injuring 22. The next day, during protests at Gdańsk

Gdansk

Gdańsk is a Polish city on the Baltic coast, at the centre of the country's fourth-largest metropolitan area.The city lies on the southern edge of Gdańsk Bay , in a conurbation with the city of Gdynia, spa town of Sopot, and suburban communities, which together form a metropolitan area called the...

, government forces again fired at demonstrators, killing 1 and injuring 2. By December 28, 1981, strikes had ceased, and Solidarity appeared crippled. The last strike in the 1981 Poland, which ended on December 28, took place in the Piast coal mine in the Upper Silesian town of Bieruń

Bierun

Bieruń is a town in Upper Silesia, in southern Poland, about south of Katowice. The town belongs to the Silesian Voivodeship since its formation in 1999, previously to Katowice Voivodeship and, before World War II, was part of the Polish Autonomous Silesian Voivodeship.-Geography:It is located...

. It was the longest underground strike in the history of Poland, lasting 14 days. Some 2000 miners began it on December 14, going 650 meters underground. Out of the initial 2000, half remained until the last day. Starving, they gave up after military authorities promised they would not be prosecuted. On October 8, 1982, Solidarity was banned.

The range of support for the Solidarity was unique: no other movement in the world was supported by Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

and Santiago Carrillo

Santiago Carrillo

Santiago Carrillo Solares is a Spanish politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of Spain from 1960 to 1982.- Childhood and early youth :...

, Enrico Berlinguer

Enrico Berlinguer

Enrico Berlinguer was an Italian politician; he was national secretary of the Italian Communist Party from 1972 until his death.-Early career:...

and the Pope, Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

and Tony Benn

Tony Benn

Anthony Neil Wedgwood "Tony" Benn, PC is a British Labour Party politician and a former MP and Cabinet Minister.His successful campaign to renounce his hereditary peerage was instrumental in the creation of the Peerage Act 1963...

, peace campaigners and NATO spokesman, Christians and Western communists, conservatives, liberals and socialists. The international community

International community

The international community is a term used in international relations to refer to all peoples, cultures and governments of the world or to a group of them. The term is used to imply the existence of common duties and obligations between them...

outside the Iron Curtain

Iron Curtain

The concept of the Iron Curtain symbolized the ideological fighting and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1989...

condemned Jaruzelski's actions and declared support for Solidarity; dedicated organizations were formed for that purpose (like Polish Solidarity Campaign

Polish Solidarity Campaign

Britain's Polish Solidarity Campaign was a campaign in solidarity with Solidarity and other democratic forces in Poland. It was founded in August 1980 by Robin Blick, Karen Blick, and Adam Westoby, and continued its activities into the first half of the 1990s...

in Great Britain). US President Ronald Reagan imposed economic sanctions

Economic sanctions

Economic sanctions are domestic penalties applied by one country on another for a variety of reasons. Economic sanctions include, but are not limited to, tariffs, trade barriers, import duties, and import or export quotas...

on Poland, which eventually would force the Polish government into liberalizing its policies. Meanwhile the CIA together with the Catholic Church and various Western trade unions such as the AFL-CIO

AFL-CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, commonly AFL–CIO, is a national trade union center, the largest federation of unions in the United States, made up of 56 national and international unions, together representing more than 11 million workers...

provided funds, equipment and advice to the Solidarity underground. The political alliance of Reagan and the Pope would prove important to the future of Solidarity. The Polish public also supported what was left of Solidarity; a major medium for demonstrating support of Solidarity became masses held by priests such as Jerzy Popiełuszko.

Besides the communist authorities, Solidarity was also opposed by some of the Polish (emigré) radical right, believing Solidarity or KOR to be disguised communist groups, dominated by Jewish Trotskyite Zionists.

In July 1983, martial law was formally lifted, though many heightened controls on civil liberties and political life, as well as food rationing, remained in place through the mid-to-late 1980s.

Underground Solidarity (1982–88)

Radio Solidarity

Radio Solidarity is the name of a radio show produced by the anarchist Workers Solidarity Movement, based in Ireland. Its is broadcast on Near 90fm and podcast globally, covering current issues, politics and struggle in Ireland and further afield....

began broadcasting. On April 22, Zbigniew Bujak

Zbigniew Bujak

Zbigniew Bujak was an electrician and foreman in 1980 at the Ursus tractor factory near Warsaw, Poland. He became engaged with trade union activists, and during the strike action, he organized strike committees at the Ursus factory...

, Bogdan Lis

Bogdan Lis

Bogdan Lis is a Polish politician, known for his involvement with the anti-communist Solidarity social movement.Born in Gdańsk in 1952, he worked in Port of Gdańsk and Elmor company. Between 1971 and 1972 he was imprisoned for his participation in the anti-governmental coastal cities protests...

, Władysław Frasyniuk and Władysław Hardek created an Interim Coordinating Commission (Tymczasowa Komisja Koordynacyjna) to serve as an underground leadership for Solidarity. On May 6 another underground Solidarity organization, an NSSZ "S" Regional Coordinating Commission (Regionalna Komisja Koordynacyjna NSZZ "S"), was created by Bogdan Borusewicz

Bogdan Borusewicz

Bogdan Michał Borusewicz, is the Speaker in the Polish Senate since 20 October 2005. Borusewicz was a democratic opposition activist under the Communist regime, a member of the Polish parliament for three terms and first Senate Speaker to serve two terms in this office.Borusewicz briefly served...

, Aleksander Hall

Aleksander Hall

Aleksander Hall was a Polish conservative politician. Activist of Movement for Defense of Human and Civic Rights, later a politician and member of Solidarity Electoral Action. In 2001, he quit politics to focus on research. Author of many books and articles on history, patriotism, etc. He is...

, Stanisław Jarosz, Bogdan Lis

Bogdan Lis

Bogdan Lis is a Polish politician, known for his involvement with the anti-communist Solidarity social movement.Born in Gdańsk in 1952, he worked in Port of Gdańsk and Elmor company. Between 1971 and 1972 he was imprisoned for his participation in the anti-governmental coastal cities protests...

and Marian Świtek. June 1982 saw the creation of a Fighting Solidarity

Fighting Solidarity