Vere Gordon Childe

Encyclopedia

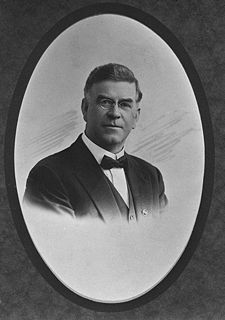

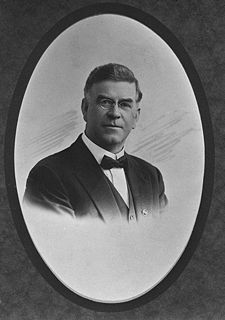

Vere Gordon Childe better known as V. Gordon Childe, was an Australian

archaeologist

and philologist who specialised in the study of European prehistory. A vocal socialist

, Childe accepted the socio-economic theory of Marxism

and was an early proponent of Marxist archaeology

. Childe worked for most of his life as an academic in the United Kingdom, initially at the University of Edinburgh

, and later at the Institute of Archaeology

, London. He also wrote a number of groundbreaking books on the subject of archaeology and prehistory, most notably Man Makes Himself (1936) and What Happened in History (1942).

Born in Sydney

, New South Wales

into a middle class family of English descent, Childe studied at the University of Sydney

before moving to England where he studied at the University of Oxford

. Upon returning to Australia he was prevented from working in academia because of his political views and so took up employment working for the Australian Labor Party

before he once more returned to England, settling down in London. Here he proceeded through a variety of jobs, all the time continuing his research into European prehistory by making various journeys across the continent, and eventually publishing his findings in academic papers and books.

From 1927 through to 1946 he was employed as the Abercromby Professor of Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh, and at that time was responsible for the excavation of the unique Neolithic

settlement of Skara Brae

and the chambered tomb of Maeshowe

, both in Orkney, northern Scotland. Becoming a co-founder and president of the Prehistoric Society, it was also at this time that he came to embrace Marxism and became a noted sympathiser with the Soviet Union, particularly during the Second World War. In 1947 he was offered the post of director at the Institute of Archaeology, something that he took up until 1957, when he retired. That year he committed suicide by jumping off of a cliff in the Australian Blue Mountains near to where he was born.

He has been described as being "the most eminent and influential scholar of European prehistory in the twentieth century". He was noted for synthesizing archaeological data from a variety of sources, thereby developing an understanding of wider European prehistory as a whole. Childe is also remembered for his emphasis on revolutionary developments on human society, such as the Neolithic Revolution

and the Urban Revolution

, in this manner being influenced by Marxist ideas of societal development.

, New South Wales

. He was the only surviving child of the Reverend Stephen Henry and Harriet Eliza Childe, a middle class couple of English descent. Stephen Childe (1807–1923) had been the son of William Childe, a stern English priest and teacher, and had followed in his father's footsteps by being ordained into the Church of England

in 1867 after gaining a BA from the University of Cambridge

. In 1871 he had married a woman named Mary Ellen Latchford, with whom he would have five children, and he went on to earn employment working as a teacher at various schools across Britain. Deciding to emigrate, the couple and their children moved to Australia's New South Wales in 1878, but it was here that Mary died after a few years, and so in 1886 Stephen remarried, this time to Harriet Eliza Gordon (1853–1910), an Englishwoman from a wealthy background who had moved to Australia when still a child. Harriet gave birth to Vere Gordon Childe in 1892, and he was raised along with his five older half-siblings at his father's palatial country house, the Chalet Fontenelle, which was located at Wentworth Falls

in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. In Australia, the Reverend Childe worked as the minister for St. Thomas' Parish, but proved unpopular, getting into many arguments with other members of the community and often taking unscheduled holidays into the countryside when he was supposed to be overseeing religious services.

Being a sickly child, Gordon Childe was home schooled for a number of years, before being sent to gain an education at a private school in North Sydney

. In 1907, he began attending the Sydney Church of England Grammar School

, where he gained his Junior Matriculation in 1909, and then his Senior Matriculation the following year. At the school he studied ancient history, French, Greek, Latin, geometry, algebra and trigonometry, achieving good marks in all subjects, but was bullied because of his strange appearance and unathletic body. In July 1910 his mother, Harriet Childe, died, and his father took a woman named Monica Gardiner to be his third wife soon after. Gordon Childe's relationship with his father was strained, particularly following his mother's death, and they disagreed heavily on the subject of religion and politics, with the Reverend being a devout Christian and a conservative

whilst Gordon Childe was an atheist

and a socialist

.

at the University of Sydney

in 1911, where although he focused on the study of written sources, he first came across classical archaeology

through the works of prominent archaeologists like Heinrich Schliemann

and Sir Arthur Evans. At the University, he became an active member of the Debating Society, at one point arguing in favour of the proposition that "socialism is desirable". He had become increasingly interested in socialism and Marxism

, reading the works of the prominent Marxist theoreticians Karl Marx

and Friedrich Engels

, as well as the works of philosopher G.W.F. Hegel

, whose ideas on dialectical materialism

had been hugely influential on Marxist theory. Ending his studies in 1913, Childe graduated the following year with various honours and prizes, including Professor Francis Anderson

's prize for Philosophy.

Wishing to continue his education, he gained £200 from the Cooper Graduate Scholarship in Classics, allowing him to afford the tuition fees at Queen's College

, a part of the University of Oxford

, England. He set sail for Britain in August 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I

in which Britain, then allied with France and Russia, went to war with Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. At Queen's, Childe was entered for a diploma in classical archaeology followed by a Bachelor of Literature degree, but did not complete the requirements for the former. It was here that he studied under such archaeologists as John Beazley

and Arthur Evans

, the latter of whom acted as his supervisor. In 1915, he published his first academic paper, 'On the Date and Origin of Minyan Ware', which appeared in the Journal of Hellenic Studies

, and the following year produced his B.Litt. thesis, 'The Influence of Indo-Europeans in Prehistoric Greece', which displayed his interest in combining philological and archaeological evidence.

At Oxford he became actively involved with the local socialist movement, something which antagonised the conservative, rightist university authorities. He rose to become a noted member of the Oxford University Fabian Society, then at the height of its power and membership, and was there when, in 1915, it changed its name to the Oxford University Socialist Society following a split from the main Fabian Society

. His best friend and flatmate at the time was Rajani Palme Dutt

, a British citizen born to an Indian father and a Swedish mother who was also a fervent socialist and Marxist. The two would often get drunk and test each other's knowledge about classical history late at night. With Britain being in the midst of World War I, many socialists refused to fight for the British Army despite the government imposed conscription. They believed that the war was merely being waged in the interests of the ruling classes of the European imperialist

nations at the expense of the working classes, and that class war

was the only conflict that they should be concerned with. Dutt was imprisoned for refusing to fight, and Childe campaigned for both his release and the release of other socialists and pacifist conscientious objectors. Childe himself was never required to enlist in the army, most likely because his poor health and poor eyesight would have prevented him from being an effective soldier.

, and moving to the city he got involved in the socialist and anti-conscription movement that was centred there. In Easter 1918 he was one of the speakers at the Third Inter-State Peace Conference, an event organised by the Australian Union of Democratic Control for the Avoidance of War, a group that was deeply opposed to the plans by Prime Minister Billy Hughes

(then the leader of the centre-right Nationalist Party of Australia

) to introduce conscription for Australian males. The conference had a prominent socialist emphasis, with Peter Simonoff, the Soviet Consul-General for Australia, being present, and its report argued that the best hope for the end to international war was the "abolition of the Capitalist System". News of Childe's participation reached the Principal of St Andrew's College, Dr Harper, who, under pressure from the university authorities, forced Childe to resign from his job because of his political beliefs. With his good academic reputation however, several other members of staff at the University agreed to provide him with a job as a tutor in Ancient History in the Department of Tutorial Classes, but ultimately he was prevented from doing so by the Chancellor of the University, Chief Justice Sir William Cullen

, who feared that Childe would propagate his socialist ideas to students.

Realising that an academic career would be barred from him by the right wing university authorities in Australia, Childe then turned to getting a job within the actual leftist movement itself. In August 1919, he became Private Secretary and speech writer to the politician John Storey

Realising that an academic career would be barred from him by the right wing university authorities in Australia, Childe then turned to getting a job within the actual leftist movement itself. In August 1919, he became Private Secretary and speech writer to the politician John Storey

, a prominent member of the centre-left Australian Labor Party

that was then in opposition to the Nationalist government in the state of New South Wales

. A member of the New South Wales Legislative Council

, where he represented the Sydney suburb of Balmain

, Storey became the state Premier

in 1920 when Labor achieved an electoral victory there. Working for such a senior figure in the Labor Party allowed Childe to gain an "unrivalled grasp of its structure and history", eventually enabling him to write a book on the subject, How Labour Governs (1923). However, the further involved that he got, the more Childe became critical of Labor, believing that they betrayed their socialist ideals once they gained political power and moderated to a more centrist, pro-capitalist stance.

Instead he became involved in the Australian branch of an international revolutionary socialist group called the Industrial Workers of the World

that advocated a specifically Marxist worldview. Although the group had been illegalised by the Australian government who considered it a political threat, it continued to operate with the support of figures like Childe, whose political views were increasingly moving further to the left. Meanwhile, Storey became anxious that the British press be kept updated with accurate news about New South Wales, and so in 1921 he sent Childe to London in order to act in this capacity. In December of that year however, Storey died, and a few days later the New South Wales elections led to the restoration of a Nationalist government under the premiership of George Fuller

. Fuller and his party members did not agree that Childe's job was necessary, and in early 1922 his employment was terminated.

, an area of central London, he initially found it hard to gain work, but spent much time studying at the nearby British Museum

and the library of the Royal Anthropological Institute. He also became an active member of the London socialist movement, associating with other leftists at the 1917 Club in Gerrard Street, Soho

, which was also frequented by such notables as Ramsay MacDonald

, Aldous Huxley

, H.G. Wells, H.N. Brailsford, Elsa Lanchester

and Rose Macauley. Although a socialist, he had not at this time adopted the Marxist views that he would be known for in later life, and for this reason did not join the Communist Party of Great Britain

, of which many of his friends were members.

Meanwhile, Childe had earned himself a reputation as a "prehistorian of exceptional promise", and he began to be invited to travel to other parts of Europe in order to study prehistoric artefacts. In 1922 he travelled to Vienna in Austria where he examined unpublished material about the painted Neolithic

pottery from Schipenitz, Bukowina

that was held in the Prehistoric Department of the Natural History Museum

. He soon published his findings from this visit in the 1923 Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. Childe also used this excursion as an opportunity to visit a number of museums in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, bringing them to the attention of British archaeologists in a 1922 article published in Man

. Returning to London, Childe became a private secretary again in 1922, this time for three British Members of Parliament

, including John Hope Simpson

and Frank Gray

, both of whom were members of the centre-left Liberal Party

. To supplement this income, Childe, who had mastered a variety of European languages, also worked as a translator for the publishers Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co

and occasionally lectured in prehistory at the London School of Economics

.

In 1923 his first book, How Labour Governs, was published by the London Labour Company. The work offered an examination of the Australian Labor Party and its wider connection with the Australian labour movement

, reflecting Childe's increasing dissolutionment with the party, believing that whilst it contained socialist members, the politicians that it managed to get elected had abandoned their socialist ideals in favour of personal comfort. His later biographer Sally Green (1981) noted that How Labour Governs was of particular significance at the time because it was published just as the British Labour Party

was emerging as a major player in British politics, threatening the former two-party dominance of the Conservatives

and Liberals. Indeed in 1924, the year after the book's publication, Labour, under the leadership of Ramsay MacDonald, was elected into power in the U.K. for the very first time in history.

In May 1923 he visited continental Europe once more, journeying to the museums in Lausanne, Berne and Zürich in order to study their collections of prehistoric artefacts, and that same year became a member of the Royal Anthropological Institute. In 1925, the Institute offered him "one of the very few archaeological jobs in Britain", and he became their librarian, and in doing so he helped to cement connections with scholars working in other parts of Europe. This job meant that he came into contact with many of Britain's archaeologists, of whom there were relatively few during the 1920s, and he developed a great friendship with O.G.S. Crawford, the noted Archaeological Officer to the Ordnance Survey

who was himself a devout Marxist.

In 1925, the company Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co published Childe's second book, The Dawn of European Civilisation, in which he synthesised the varied data about European prehistory that he had been exploring for many years. The work was of "outstanding importance", being released at a time when the few archaeologists across Europe were amateur and were focused purely on studying the archaeology of their locality; The Dawn was a rare example of a book that looked at the larger picture across an entire continent. Describing this groundbreaking book many years later, Childe would state that it "aimed at distilling from archaeological remains a preliterate substitute for the conventional politico-military history with cultures, instead of statesmen, as actors, and migrations in place of battles." In 1926 he brought out a successor work, The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins, in which he looked at the theory that civilisation diffused northward and westward from the Near East to the rest of Europe via a linguistic group known as the Aryans. In these works, Childe accepted a moderate diffusionism, believing that although most cultural traits spread from one society to another, it was possible for the same traits to develop independently in different places. Such a theory was at odds with the hyper-diffusionism purported by Sir Grafton Elliot Smith which argued that all the cultural traits associated with civilisation must have originated from a single source.

in Scotland, so named after the Scottish prehistorian Lord John Abercromby, who had established it by deed in his bequest to the university. Although Childe recognised that accepting the post would take him away from London, where all of his friends and socialist activities were centred, he decided to take up the prestigious position, moving to Edinburgh in September 1927. At the age of 35, Childe became the "only academic prehistorian in a teaching post in Scotland", and was disliked by many Scottish archaeologists, who viewed him as an outsider who wasn't even a specialist in Scottish prehistory. This hostility reached such a point that he wrote to one of his friends, telling them that "I live here in an atmosphere of hatred and envy." Despite this, he made a number of friends and allies in Edinburgh, including Sir W. Lindsay Scott, Alexander Curle, J.G. Callender, Walter Grant and Charles G. Darwin. Darwin, who was the grandson of the renowned biologist Charles Darwin

, became a particularly good friend of Childe, and asked him to be the godfather of his youngest son, Edward.

At Edinburgh University, Childe spent much of his time focusing on his own research, and although he was reportedly very kind towards his students, never interacted much with them, to whom he remained largely distant. He had difficulty speaking to large audiences, and organised the BSc

degree course so that it began with studying the Iron Age

, and then progressed chronologically backward, through the Bronze Age

, Neolithic

, Mesolithic

and Palaeolithic, something many students found confusing. He also founded an archaeological society known as the Edinburgh League of Prehistorians, through which he took his more enthusiastic students on excavations and invited guest lecturers to visit them. He would often involve his students in experimental archaeology

, something that he was an early proponent of, for instance knapping flint lithics

in the midst of some of his lectures. Other experiments that he undertook had a clearer purpose, for instance in 1937 he performed experiments to understand the vitrification

process that had occurred at several Iron Age forts in northern Britain.

In Edinburgh, he initially lodged at Liberton

, although later moved into a semi-residential hotel, the Hotel de Vere, which was located in Eglington Crescent. He travelled down to London on a regular basis, where he would associate with his friends in both the socialist and archaeological communities. In the latter group, one notable friend of Childe's was Stuart Piggott

, another influential British archaeologist who would succeed Childe in his post as Abercromby Professor at Edinburgh. The duo, along with Grahame Clark, got themselves elected on to the committee of the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia, and then proceeded to use their influence over it to convert it into a nationwide organisation, the Prehistoric Society, in 1934–35, to which Childe was soon elected president.

Childe also regularly attended conferences across Europe, becoming fluent in a range of European languages, and in 1935 first visited the Soviet Union

, where he spent 12 days in Leningrad and Moscow. He was impressed with the socialist state that had been created there, and was particularly interested in the role that archaeology was playing within it. Upon his return to Britain he became a vocal Soviet sympathiser who avidly read the Daily Worker (the publication of the Communist Party of Great Britain), although was heavily critical of some of the Soviet government's policies, in particular the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact that they made with Nazi Germany

. His socialist convictions led to his early denunciation of the fascist

movement in Europe, and he was particularly outraged by the Nazi co-opting of prehistoric archaeology to glorify their own conceptions of an Aryan racial heritage. He was supportive of the British government's decision to fight the fascist powers in the Second World War and had made the decision to commit suicide should the Nazis conquer Britain, recognising that he would be one of the first that they would exterminate because of his political beliefs. Despite his opposition to the fascist powers of Germany and Italy however, he was also critical of the imperialist

, capitalist

governments in control of the United Kingdom and United States: regarding the latter, he would often describe it as being full of "loathsome fascist hyenas".

His university position meant that he was obliged to undertake archaeological excavations, something which he loathed and believed that he did poorly. Several of his students recognised that he took little interest in excavation, and was not good at much of it, but instead had a "genius for interpreting evidence". Unlike many of his contemporaries, he was scrupulous with writing up and publishing his findings, producing almost annual reports for the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and also ensured that he acknowledged the help of all of his diggers.

His university position meant that he was obliged to undertake archaeological excavations, something which he loathed and believed that he did poorly. Several of his students recognised that he took little interest in excavation, and was not good at much of it, but instead had a "genius for interpreting evidence". Unlike many of his contemporaries, he was scrupulous with writing up and publishing his findings, producing almost annual reports for the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and also ensured that he acknowledged the help of all of his diggers.

His best known excavation was that undertaken from 1927 through to 1930 at the site of Skara Brae

in the Orkney Islands

. Here, he uncovered a Neolithic village in a good state of preservation that had partially been revealed when heavy storms hit the islands. In 1931, he published the results of his excavation in a book, entitled simply Skara Brae. He got on particularly well with the local populace who lived near the Skara Brae site, and is reported that to them "he was every inch the professor" because of his eccentric appearance and habits.

In 1932, Childe, collaborating with anthropologist C. Daryll Forde, excavated two Iron Age hillforts at Earn's Hugh on the Berwickshire

coast, whilst in June 1935 he excavated a promontory fort at Larriban near to Knocksoghey in Northern Ireland. Together with Wallace Thorneycroft, another Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Childe excavated two vitrified Iron Age forts in Scotland, that at Finavon, Angus

(1933–34) and that at Rahoy, Argyllshire (1936–37).

river, recognising it as the natural boundary dividing the Near East from Europe, and subsequently he believed that it was via the Danube that various new technologies travelled westward in antiquity. In The Danube in Prehistory, Childe introduced the concept of an archaeological culture

(which up until then had been largely restrained purely to German academics), to his British counterparts. This concept would revolutionise the way in which archaeologists understood the past, and would come to be widely accepted in future decades.

Childe's next work, The Bronze Age (1930), dealt with the titular Bronze Age

in Europe, and displayed his increasing acceptance of Marxist theory in understanding how society functioned and changed. He believed that metal was the first indispensable article of commerce, and that metal-smiths were therefore full-time professionals who lived off the social surplus. Within a matter of years he had followed this up with a string of further works: The Forest Cultures of Northern Europe: A Study in Evolution and Diffusion (1931), The Continental Affinities of British Neolithic Pottery (1932) and Neolithic Settlement in the West of Scotland (1934).

In 1933, Childe travelled to Asia, visiting Iraq, a place he thought was "great fun", and then India, which he conversely felt was "detestable" because of the hot weather and the extreme poverty faced by the majority of Indians. During this holiday he toured a number of archaeological sites in the two countries, coming to the opinion that much of what he had written in The Most Ancient Near East was outdated, and so he went on to produce a new book on the subject, New Light on the Most Ancient Near East (1935), in which he applied his Marxist-influenced ideas about the economy to his conclusions.

After another publication dealing with Scottish archaeology, Prehistory of Scotland (1935), Childe produced one of the defining books of his career, Man Makes Himself (1936). Influenced by the Marxist view of history, Childe used the work to argue that the usual distinction between (pre-literate) prehistory and (literate) history was a false dichotomy and that human society has progressed through a series of technological, economic and social revolutions. These included the Neolithic Revolution

, when hunter-gatherers began settling down in permanent communities and began farming, through to the Urban Revolution

, when society progressed from a series of small towns through to the first cities, and right up to more recent times, when the Industrial Revolution

drastically changed the nature of production. With the outbreak of the Second World War, Childe was unable to travel across continental Europe, and so focused on producing a book about the prehistoric archaeology of Britain: the result was Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles (1940).

Childe's pessimism surrounding the outcome of the war led to him adopting the belief that "European Civilization – Capitalist and Stalinist

alike – was irrevocably headed for a Dark Age." It was in this state of mind that he produced what he saw as a sequal to Man Makes Himself entitled What Happened in History (1942), a synthesis of human history from the Palaeolithic through to the fall of the Roman Empire

. Although Oxford University Press

offered to publish the work, he instead chose to release the book through Penguin Books

because they would sell it at a cheaper price, something he believed was pivotal to providing his knowledge to "the masses." This was followed by two short works, Progress and Archaeology (1944) and then The Story of Tools (1944), the latter of which was explicitly Marxist and had been written for the Young Communist League

.

in London. He was anxious to return to the capital, where most of his friends and interests were centred, and as such had kept silent over his disapproval of government policies so that he would not be prevented from getting the job as had happened in Australia. The Institute had been founded in 1937, largely by noted archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler

and his wife Tessa, but until 1946 relied primarily upon volunteer lecturers. When Childe worked there, it was located in St John's Lodge, a building in the Inner Circle of Regent's Park

, although would be moved to Gordon Square in Bloomsbury in 1956. At the Institute, Childe worked alongside Wheeler, a figure who was widely known to the general public in Britain through his frequent television appearances and dominant personality. Wheeler had made a name for himself excavating the Indus Valley civilisation sites of Harappa

and Mohenjo-Daro

and unlike Childe was recognised as a particularly good field archaeologist. The duo did not get on particularly well; Wheeler was conservative and right-wing in his political views whilst also being intolerant of the shortcomings of others, something that Childe made an effort never to be. Whilst working at the Institute, Childe took up residence at Lawn Road Flats near to Hampstead

, an apartment block perhaps recommended to him by the popular crime fiction author Agatha Christie

(the wife of his colleague Max Mallowan

), who had lived there during the Second World War.

Students who studied under Childe often remarked that he was a kindly eccentric, but had a great deal of fondness for him, leading them to commission a bust of him from Marjorie Maitland-Howard. He was not however thought of as a particularly good lecturer, often mumbling his words or walking into an adjacent room to find something whilst continuing to give his talk. He was also known to refer to the socialist states in eastern Europe by their full official titles (for instance using "German Democratic Republic" over "East Germany" and "Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

" over "Yugoslavia"), and also referred to east European towns with their Slavonic rather than Germanic names, further confusing his students who were familiar with the latter. He was widely seen as being better at giving tutorials and seminars, where he could devote more time to interacting with his students individually.

Whereas he had been required to undertake much fieldwork and excavation whilst at Edinburgh, at the Institute his position as Director meant that this was not necessary, although he did undertake one excavation at Maes Howe, a Neolithic burial tomb plundered by Early Medieaval Norse raiders, during 1954–55. Meanwhile, in 1949 Childe and his friend O.G.S. Crawford resigned their positions as Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries

Whereas he had been required to undertake much fieldwork and excavation whilst at Edinburgh, at the Institute his position as Director meant that this was not necessary, although he did undertake one excavation at Maes Howe, a Neolithic burial tomb plundered by Early Medieaval Norse raiders, during 1954–55. Meanwhile, in 1949 Childe and his friend O.G.S. Crawford resigned their positions as Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries

in protest at the election of James Mann

to the Presidency following the retirement of Cyril Fox

. They believed that Mann, who was the Keeper of the Tower's Armouries at the Tower of London

, was a poor choice and that Mortimer Wheeler, being an actual prehistorian, should have won the election.

In 1952 a group of British Marxist historians began publishing the periodical Past and Present

, with Childe soon joining the editorial board. Similarly, he became a member of the board for The Modern Quarterly (later The Marxist Quarterly) during the early 1950s, working alongside his old friend Rajani Palme Dutt, who held the position of chairman of the board. He also wrote occasional articles for Palme Dutt's socialist journal, the Labour Monthly, but disagreed with him on the issue of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Palme Dutt had defended the Soviet Union's decision to quash the revolution using military force, but Childe, like many western socialists and Marxists at the time, strongly disagreed that this was an appropriate measure to take. The actions of the Soviet government alienated Childe, who lost his formerly firm faith in Joseph Stalin

's administration, but not his belief in socialism and Marxist theory. Despite the events of 1956, Childe retained a love of the Soviet Union, having visited it on a number of occasions prior, and was involved with the Society for Cultural Relations with the USSR, a satellite body of the Communist Party of Great Britain. He was also the president of the Society's National History and Archaeology Section from the early 1950s until his death. In April 1956, he had been awarded the Gold Medal of the Society of Antiquaries for his services to archaeology.

Whilst working at the Institute, Childe continued writing and publishing books dealing with archaeology and prehistory. History (1947) continued his belief that prehistory and literate history must be viewed together, and adopted a Marxist view of history, whilst Prehistoric Migrations (1950) displayed his views on moderate diffusionism. In 1946 he had also published a paper in the Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, entitled "Archaeology and Anthropology" which argued that the two disciplines must be used in tandem, something that would be widely accepted in the decades following his death.

In England he sorted out his affairs, donating most of his personal library, and all of his estate, to the Institute of Archaeology. After a holiday then spent visiting archaeological sites in Gibraltar and Spain in February 1957, he sailed to Australia, reaching Sydney on his 65th birthday. Here, the University of Sydney, which had once barred him from working there, now awarded him an honourary degree. He proceeded to travel around the country for the next six months, visiting various surviving family members and old friends. However he was unimpressed by what he saw of Australian society, coming to the opinion that the nation's society had not progressed in any way since the 1920s, having simply become reactionary, increasingly suburban and un-educated. Meanwhile, he also began to look into the prehistory of Australia, coming to the opinion that there was much for archaeologists to study in this field, and he gave several lectures to various archaeological and leftist groups on this and other topics. In the final week of his life he even gave a talk on Australian radio in which he argued against the racist and dismissive attitude of many Australian academics towards the Indigenous Australian

peoples of the continent.

Shortly before his death he wrote letters to many of his friends that dealt with particularly personal topics. He also wrote a letter to W.F. Grimes, requesting that it not be opened until 1968. In it, he described how he feared old age, and stated his intention to take his own life, remarking that "Life ends best when one is happy and strong." On the morning of 19 October 1957, Childe went walking around the area of the Bridal Veil Falls in the Blue Mountains where he had grown up. He had left his hat, spectacles, compass, pipe and Mackintosh atop Govett's Leap at Blackheath

Shortly before his death he wrote letters to many of his friends that dealt with particularly personal topics. He also wrote a letter to W.F. Grimes, requesting that it not be opened until 1968. In it, he described how he feared old age, and stated his intention to take his own life, remarking that "Life ends best when one is happy and strong." On the morning of 19 October 1957, Childe went walking around the area of the Bridal Veil Falls in the Blue Mountains where he had grown up. He had left his hat, spectacles, compass, pipe and Mackintosh atop Govett's Leap at Blackheath

, before falling 1000 feet to his death. His death certificate issued by the coroner claimed that he had died from an accidental fall whilst studying rock formations, and it would only be in the 1980s, with the publication of his letter to Grimes, that his death became recognised as a suicide.

Later archaeologist Neil Faulkner

believed that part of the reason why Childe decided to take his own life was that his "political illusions had been shattered" after he had begun to lose faith in the direction being taken by the world's foremost socialist state, the Soviet Union. This, Faulkner believed, had been brought about by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev

's denouncement of Joseph Stalin

and the Soviet Union's violent crushing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Faulkner theorised that without contact with members of the New Left

or the Trotskyists

, the two main Marxist currents in Britain that were critical of the Soviet Union at the time, Childe felt alone in his conflicting feelings about the country, and despaired for the future of humanity.

, which had originally been formulated by the 19th century German philosophers and sociologists Karl Marx

and Friedrich Engels

. They put forward their ideas in a series of books, most notably the political pamphlet widely called The Communist Manifesto

(1848) and Marx's several-volume study, Capital

(1867–1894). Taking the ideas of fellow German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel

as a basis, Marx and Engels argued that all of human society rests upon class war

, the concept that different socio-economic classes struggle against one another for their own benefit, with the ruling class inevitably being overthrown through revolution, to be replaced with a new ruling class. This constant struggle, they argued, was the force through which society progressed, and was the reason that human society has developed since the Palaeolithic. Marx and Engels both used historical examples to try and back up their theory. They argued that in early hunter-gatherer

societies, humans lived in "primitive communism

", with no class system being evident. Eventually, as populations grew, slave-based societies emerged having the distinction between slave owners and slaves as their basis. Slave society was, in turn, replaced by feudalism

, in which kings and aristocrats became the ruling class. In turn, these feudal systems were overturned by capitalism

, a system in which the bourgeoisie

, or upper middle class, gained political control.

Childe's approach to understanding the past has been typically associated with Marxist archaeology

. This form of archaeological theory

was first developed in the Soviet Union in 1929, when a young archaeologist named Vladislav I. Ravdonikas (1894–1976) published a report entitled "For a Soviet history of material culture". Within this work, the very discipline of archaeology was criticised as being inherently bourgeoisie

and therefore anti-socialist, and so, as a part of the academic reforms instituted in the Soviet Union under the administration of Premier Joseph Stalin

, a great emphasis was placed on the adoption of Marxist archaeology throughout the country.

The extent to which Childe's interpretation of the past fits the Marxist conception of history has however been called into question. His biographer Sally Green noted that "his beliefs were never dogmatic, always idiosyncretic, and were continually changing throughout his life" but that "Marxist views on a model of the past were largely accepted by Childe offering as they do a structural analysis of culture in terms of economy, sociology and ideology, and a principle for cultural change through economy." She went on to note however that "Childe's Marxism frequently differed from contemporary 'orthodox' Marxism; partly because he had studied Hegel, Marx and Engels as far back as 1913 and still referred to the original texts rather than later interpretations, and partly because he was selective in his acceptance of their writings." Childe's Marxism was further critiqued by later Marxist archaeologist Neil Faulkner

, who argued that although Childe "was a deeply committed socialist heavily influenced by Marxism", he did not appear to accept the existence of class struggle

as an instrument of social change, something which was a core tenet of Marxist thought.

Faulkner instead believed that Childe's approach to archaeological interpretation was not that of a Marxist archaeologist, but was instead a precursor to the processual archaeological

approach that would be widely adopted in the discipline during the 1960s. This contrasted with the claims of the archaeologist Peter Ucko

, who was one of Childe's successors as director of the Institute of Archaeology. Ucko highlighted that in his writings, Childe accepted the subjectivity

of archaeological interpretation, something which was in stark contrast to the processualists' insistence that archaeological interpretation could be objective. In this manner Childe's approach would have had more in common with that put forward by the post-processual archaeologists

who emerged in the late 1970s and 1980s.

Childe himself was an atheist, and remained highly critical of religion, something he saw as being based in superstition, a viewpoint shared by orthodox Marxists. In History (1947) he discussed religion and magic, commenting that "Magic is a way of making people believe they are going to get what they want, whereas religion is a system for persuading them that they ought to want what they get."

Childe was fond of cars and driving them, writing a letter in 1931 in which he stated that "I love driving (when I'm the chaffeur) passionately; one has such a feeling of power." He was fond of telling people a story about how he had raced at a high speed down Piccadilly

in London at three o'clock in the morning for the sheer enjoyment of it, only to be pulled over by a policeman for such illegal and potentially dangerous activity. He was also known for his love of practical jokes, and he allegedly used to keep a halfpenny in his pocket in order to trick pickpockets. On another occasion he played a joke on the assembled delegates at a Prehistoric Society conference by lecturing them on a theory that the Neolithic monument of Woodhenge

had been constructed as an imitation of Stonehenge

by a nouveau riche chieftain. Several members of his audience failed to realise that he was being tongue in cheek.

Childe's other hobbies included going for walks in the British hillsides, attending classical music concerts and playing the card game contract bridge

. He was fond of poetry, with his favourite poet being John Keats

, although his favourite poems were William Wordsworth

's "Ode to Duty

" and Robert Browning

's "A Grammarian's Funeral". He was not particularly interested in reading novels but his favourite was D.H. Lawrence's Kangaroo

(1923), a book set in Australia that echoed many of Childe's own feelings about his homeland. He was also a fan of good quality food and drink, and frequented a number of restaurants.

Childe always wore his wide-brimmed black hat, which he had purchased from a hatter in Jermyn Street

, central London, as well as a tie, which was usually red, a colour chosen to symbolise his socialist beliefs. He also regularly wore a shiny black Mackintosh

raincoat, often carrying it over his arm or draped over his shoulders like a cape. In summer he instead frequently wore particularly short shorts, with socks, sock suspenders and large boots.

that had been presented as revolutions by Sir John Lubbock and others in the late 19th century. Such concepts as the "Neolithic Revolution

" and "Urban Revolution

" did not begin with him but he welded them into a new synthesis of economic periods based on what could be known from the artifacts, rather than from a supposed ethnology

of an unknown past. Thanks to his presentations and influence this synthesis is now accepted as vital in prehistoric studies. Childe traveled throughout Greece, Central Europe and the Balkans studying the archaeological literature. Harris said of him:

Childe placed considerable importance on human culture as a social construct rather than a product of environmental or technological contexts. Basically, he rejected Herbert Spencer's theory of parallel cultural evolution in favor of his own theory which was divergence with modifications of convergence.

Childe is referenced in the American blockbuster film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008). Directed by Steven Spielberg

and George Lucas

, the motion picture was the fourth film in the Indiana Jones

series that dealt with the eponymous fictional archaeologist and university professor. In the film, Jones is heard advising one of his students that to understand the concept of diffusion they must read the words of Childe.

Vere Gordon Childe (14 April 1892 – 19 October 1957), better known as V. Gordon Childe, was an Australian

archaeologist

and philologist who specialised in the study of European prehistory. A vocal socialist

, Childe accepted the socio-economic theory of Marxism

and was an early proponent of Marxist archaeology

. Childe worked for most of his life as an academic in the United Kingdom, initially at the University of Edinburgh

, and later at the Institute of Archaeology

, London. He also wrote a number of groundbreaking books on the subject of archaeology and prehistory, most notably Man Makes Himself (1936) and What Happened in History (1942).

Born in Sydney

, New South Wales

into a middle class family of English descent, Childe studied at the University of Sydney

before moving to England where he studied at the University of Oxford

. Upon returning to Australia he was prevented from working in academia because of his political views and so took up employment working for the Australian Labor Party

before he once more returned to England, settling down in London. Here he proceeded through a variety of jobs, all the time continuing his research into European prehistory by making various journeys across the continent, and eventually publishing his findings in academic papers and books.

From 1927 through to 1946 he was employed as the Abercromby Professor of Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh, and at that time was responsible for the excavation of the unique Neolithic

settlement of Skara Brae

and the chambered tomb of Maeshowe

, both in Orkney, northern Scotland. Becoming a co-founder and president of the Prehistoric Society, it was also at this time that he came to embrace Marxism and became a noted sympathiser with the Soviet Union, particularly during the Second World War. In 1947 he was offered the post of director at the Institute of Archaeology, something that he took up until 1957, when he retired. That year he committed suicide by jumping off of a cliff in the Australian Blue Mountains near to where he was born.

He has been described as being "the most eminent and influential scholar of European prehistory in the twentieth century". He was noted for synthesizing archaeological data from a variety of sources, thereby developing an understanding of wider European prehistory as a whole. Childe is also remembered for his emphasis on revolutionary developments on human society, such as the Neolithic Revolution

and the Urban Revolution

, in this manner being influenced by Marxist ideas of societal development.

, New South Wales

. He was the only surviving child of the Reverend Stephen Henry and Harriet Eliza Childe, a middle class couple of English descent. Stephen Childe (1807–1923) had been the son of William Childe, a stern English priest and teacher, and had followed in his father's footsteps by being ordained into the Church of England

in 1867 after gaining a BA from the University of Cambridge

. In 1871 he had married a woman named Mary Ellen Latchford, with whom he would have five children, and he went on to earn employment working as a teacher at various schools across Britain. Deciding to emigrate, the couple and their children moved to Australia's New South Wales in 1878, but it was here that Mary died after a few years, and so in 1886 Stephen remarried, this time to Harriet Eliza Gordon (1853–1910), an Englishwoman from a wealthy background who had moved to Australia when still a child. Harriet gave birth to Vere Gordon Childe in 1892, and he was raised along with his five older half-siblings at his father's palatial country house, the Chalet Fontenelle, which was located at Wentworth Falls

in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. In Australia, the Reverend Childe worked as the minister for St. Thomas' Parish, but proved unpopular, getting into many arguments with other members of the community and often taking unscheduled holidays into the countryside when he was supposed to be overseeing religious services.

Being a sickly child, Gordon Childe was home schooled for a number of years, before being sent to gain an education at a private school in North Sydney

. In 1907, he began attending the Sydney Church of England Grammar School

, where he gained his Junior Matriculation in 1909, and then his Senior Matriculation the following year. At the school he studied ancient history, French, Greek, Latin, geometry, algebra and trigonometry, achieving good marks in all subjects, but was bullied because of his strange appearance and unathletic body. In July 1910 his mother, Harriet Childe, died, and his father took a woman named Monica Gardiner to be his third wife soon after. Gordon Childe's relationship with his father was strained, particularly following his mother's death, and they disagreed heavily on the subject of religion and politics, with the Reverend being a devout Christian and a conservative

whilst Gordon Childe was an atheist

and a socialist

.

at the University of Sydney

in 1911, where although he focused on the study of written sources, he first came across classical archaeology

through the works of prominent archaeologists like Heinrich Schliemann

and Sir Arthur Evans. At the University, he became an active member of the Debating Society, at one point arguing in favour of the proposition that "socialism is desirable". He had become increasingly interested in socialism and Marxism

, reading the works of the prominent Marxist theoreticians Karl Marx

and Friedrich Engels

, as well as the works of philosopher G.W.F. Hegel

, whose ideas on dialectical materialism

had been hugely influential on Marxist theory. Ending his studies in 1913, Childe graduated the following year with various honours and prizes, including Professor Francis Anderson

's prize for Philosophy.

Wishing to continue his education, he gained £200 from the Cooper Graduate Scholarship in Classics, allowing him to afford the tuition fees at Queen's College

, a part of the University of Oxford

, England. He set sail for Britain in August 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I

in which Britain, then allied with France and Russia, went to war with Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. At Queen's, Childe was entered for a diploma in classical archaeology followed by a Bachelor of Literature degree, but did not complete the requirements for the former. It was here that he studied under such archaeologists as John Beazley

and Arthur Evans

, the latter of whom acted as his supervisor. In 1915, he published his first academic paper, 'On the Date and Origin of Minyan Ware', which appeared in the Journal of Hellenic Studies

, and the following year produced his B.Litt. thesis, 'The Influence of Indo-Europeans in Prehistoric Greece', which displayed his interest in combining philological and archaeological evidence.

At Oxford he became actively involved with the local socialist movement, something which antagonised the conservative, rightist university authorities. He rose to become a noted member of the Oxford University Fabian Society, then at the height of its power and membership, and was there when, in 1915, it changed its name to the Oxford University Socialist Society following a split from the main Fabian Society

. His best friend and flatmate at the time was Rajani Palme Dutt

, a British citizen born to an Indian father and a Swedish mother who was also a fervent socialist and Marxist. The two would often get drunk and test each other's knowledge about classical history late at night. With Britain being in the midst of World War I, many socialists refused to fight for the British Army despite the government imposed conscription. They believed that the war was merely being waged in the interests of the ruling classes of the European imperialist

nations at the expense of the working classes, and that class war

was the only conflict that they should be concerned with. Dutt was imprisoned for refusing to fight, and Childe campaigned for both his release and the release of other socialists and pacifist conscientious objectors. Childe himself was never required to enlist in the army, most likely because his poor health and poor eyesight would have prevented him from being an effective soldier.

, and moving to the city he got involved in the socialist and anti-conscription movement that was centred there. In Easter 1918 he was one of the speakers at the Third Inter-State Peace Conference, an event organised by the Australian Union of Democratic Control for the Avoidance of War, a group that was deeply opposed to the plans by Prime Minister Billy Hughes

(then the leader of the centre-right Nationalist Party of Australia

) to introduce conscription for Australian males. The conference had a prominent socialist emphasis, with Peter Simonoff, the Soviet Consul-General for Australia, being present, and its report argued that the best hope for the end to international war was the "abolition of the Capitalist System". News of Childe's participation reached the Principal of St Andrew's College, Dr Harper, who, under pressure from the university authorities, forced Childe to resign from his job because of his political beliefs. With his good academic reputation however, several other members of staff at the University agreed to provide him with a job as a tutor in Ancient History in the Department of Tutorial Classes, but ultimately he was prevented from doing so by the Chancellor of the University, Chief Justice Sir William Cullen

, who feared that Childe would propagate his socialist ideas to students.

Realising that an academic career would be barred from him by the right wing university authorities in Australia, Childe then turned to getting a job within the actual leftist movement itself. In August 1919, he became Private Secretary and speech writer to the politician John Storey

Realising that an academic career would be barred from him by the right wing university authorities in Australia, Childe then turned to getting a job within the actual leftist movement itself. In August 1919, he became Private Secretary and speech writer to the politician John Storey

, a prominent member of the centre-left Australian Labor Party

that was then in opposition to the Nationalist government in the state of New South Wales

. A member of the New South Wales Legislative Council

, where he represented the Sydney suburb of Balmain

, Storey became the state Premier

in 1920 when Labor achieved an electoral victory there. Working for such a senior figure in the Labor Party allowed Childe to gain an "unrivalled grasp of its structure and history", eventually enabling him to write a book on the subject, How Labour Governs (1923). However, the further involved that he got, the more Childe became critical of Labor, believing that they betrayed their socialist ideals once they gained political power and moderated to a more centrist, pro-capitalist stance.

Instead he became involved in the Australian branch of an international revolutionary socialist group called the Industrial Workers of the World

that advocated a specifically Marxist worldview. Although the group had been illegalised by the Australian government who considered it a political threat, it continued to operate with the support of figures like Childe, whose political views were increasingly moving further to the left. Meanwhile, Storey became anxious that the British press be kept updated with accurate news about New South Wales, and so in 1921 he sent Childe to London in order to act in this capacity. In December of that year however, Storey died, and a few days later the New South Wales elections led to the restoration of a Nationalist government under the premiership of George Fuller

. Fuller and his party members did not agree that Childe's job was necessary, and in early 1922 his employment was terminated.

, an area of central London, he initially found it hard to gain work, but spent much time studying at the nearby British Museum

and the library of the Royal Anthropological Institute. He also became an active member of the London socialist movement, associating with other leftists at the 1917 Club in Gerrard Street, Soho

, which was also frequented by such notables as Ramsay MacDonald

, Aldous Huxley

, H.G. Wells, H.N. Brailsford, Elsa Lanchester

and Rose Macauley. Although a socialist, he had not at this time adopted the Marxist views that he would be known for in later life, and for this reason did not join the Communist Party of Great Britain

, of which many of his friends were members.

Meanwhile, Childe had earned himself a reputation as a "prehistorian of exceptional promise", and he began to be invited to travel to other parts of Europe in order to study prehistoric artefacts. In 1922 he travelled to Vienna in Austria where he examined unpublished material about the painted Neolithic

pottery from Schipenitz, Bukowina

that was held in the Prehistoric Department of the Natural History Museum

. He soon published his findings from this visit in the 1923 Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. Childe also used this excursion as an opportunity to visit a number of museums in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, bringing them to the attention of British archaeologists in a 1922 article published in Man

. Returning to London, Childe became a private secretary again in 1922, this time for three British Members of Parliament

, including John Hope Simpson

and Frank Gray

, both of whom were members of the centre-left Liberal Party

. To supplement this income, Childe, who had mastered a variety of European languages, also worked as a translator for the publishers Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co

and occasionally lectured in prehistory at the London School of Economics

.

In 1923 his first book, How Labour Governs, was published by the London Labour Company. The work offered an examination of the Australian Labor Party and its wider connection with the Australian labour movement

, reflecting Childe's increasing dissolutionment with the party, believing that whilst it contained socialist members, the politicians that it managed to get elected had abandoned their socialist ideals in favour of personal comfort. His later biographer Sally Green (1981) noted that How Labour Governs was of particular significance at the time because it was published just as the British Labour Party

was emerging as a major player in British politics, threatening the former two-party dominance of the Conservatives

and Liberals. Indeed in 1924, the year after the book's publication, Labour, under the leadership of Ramsay MacDonald, was elected into power in the U.K. for the very first time in history.

In May 1923 he visited continental Europe once more, journeying to the museums in Lausanne, Berne and Zürich in order to study their collections of prehistoric artefacts, and that same year became a member of the Royal Anthropological Institute. In 1925, the Institute offered him "one of the very few archaeological jobs in Britain", and he became their librarian, and in doing so he helped to cement connections with scholars working in other parts of Europe. This job meant that he came into contact with many of Britain's archaeologists, of whom there were relatively few during the 1920s, and he developed a great friendship with O.G.S. Crawford, the noted Archaeological Officer to the Ordnance Survey

who was himself a devout Marxist.

In 1925, the company Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co published Childe's second book, The Dawn of European Civilisation, in which he synthesised the varied data about European prehistory that he had been exploring for many years. The work was of "outstanding importance", being released at a time when the few archaeologists across Europe were amateur and were focused purely on studying the archaeology of their locality; The Dawn was a rare example of a book that looked at the larger picture across an entire continent. Describing this groundbreaking book many years later, Childe would state that it "aimed at distilling from archaeological remains a preliterate substitute for the conventional politico-military history with cultures, instead of statesmen, as actors, and migrations in place of battles." In 1926 he brought out a successor work, The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins, in which he looked at the theory that civilisation diffused northward and westward from the Near East to the rest of Europe via a linguistic group known as the Aryans. In these works, Childe accepted a moderate diffusionism, believing that although most cultural traits spread from one society to another, it was possible for the same traits to develop independently in different places. Such a theory was at odds with the hyper-diffusionism purported by Sir Grafton Elliot Smith which argued that all the cultural traits associated with civilisation must have originated from a single source.

in Scotland, so named after the Scottish prehistorian Lord John Abercromby, who had established it by deed in his bequest to the university. Although Childe recognised that accepting the post would take him away from London, where all of his friends and socialist activities were centred, he decided to take up the prestigious position, moving to Edinburgh in September 1927. At the age of 35, Childe became the "only academic prehistorian in a teaching post in Scotland", and was disliked by many Scottish archaeologists, who viewed him as an outsider who wasn't even a specialist in Scottish prehistory. This hostility reached such a point that he wrote to one of his friends, telling them that "I live here in an atmosphere of hatred and envy." Despite this, he made a number of friends and allies in Edinburgh, including Sir W. Lindsay Scott, Alexander Curle, J.G. Callender, Walter Grant and Charles G. Darwin. Darwin, who was the grandson of the renowned biologist Charles Darwin

, became a particularly good friend of Childe, and asked him to be the godfather of his youngest son, Edward.

At Edinburgh University, Childe spent much of his time focusing on his own research, and although he was reportedly very kind towards his students, never interacted much with them, to whom he remained largely distant. He had difficulty speaking to large audiences, and organised the BSc

degree course so that it began with studying the Iron Age

, and then progressed chronologically backward, through the Bronze Age

, Neolithic

, Mesolithic

and Palaeolithic, something many students found confusing. He also founded an archaeological society known as the Edinburgh League of Prehistorians, through which he took his more enthusiastic students on excavations and invited guest lecturers to visit them. He would often involve his students in experimental archaeology

, something that he was an early proponent of, for instance knapping flint lithics

in the midst of some of his lectures. Other experiments that he undertook had a clearer purpose, for instance in 1937 he performed experiments to understand the vitrification

process that had occurred at several Iron Age forts in northern Britain.

In Edinburgh, he initially lodged at Liberton

, although later moved into a semi-residential hotel, the Hotel de Vere, which was located in Eglington Crescent. He travelled down to London on a regular basis, where he would associate with his friends in both the socialist and archaeological communities. In the latter group, one notable friend of Childe's was Stuart Piggott

, another influential British archaeologist who would succeed Childe in his post as Abercromby Professor at Edinburgh. The duo, along with Grahame Clark, got themselves elected on to the committee of the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia, and then proceeded to use their influence over it to convert it into a nationwide organisation, the Prehistoric Society, in 1934–35, to which Childe was soon elected president.

Childe also regularly attended conferences across Europe, becoming fluent in a range of European languages, and in 1935 first visited the Soviet Union

, where he spent 12 days in Leningrad and Moscow. He was impressed with the socialist state that had been created there, and was particularly interested in the role that archaeology was playing within it. Upon his return to Britain he became a vocal Soviet sympathiser who avidly read the Daily Worker (the publication of the Communist Party of Great Britain), although was heavily critical of some of the Soviet government's policies, in particular the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact that they made with Nazi Germany

. His socialist convictions led to his early denunciation of the fascist

movement in Europe, and he was particularly outraged by the Nazi co-opting of prehistoric archaeology to glorify their own conceptions of an Aryan racial heritage. He was supportive of the British government's decision to fight the fascist powers in the Second World War and had made the decision to commit suicide should the Nazis conquer Britain, recognising that he would be one of the first that they would exterminate because of his political beliefs. Despite his opposition to the fascist powers of Germany and Italy however, he was also critical of the imperialist

, capitalist

governments in control of the United Kingdom and United States: regarding the latter, he would often describe it as being full of "loathsome fascist hyenas".

His university position meant that he was obliged to undertake archaeological excavations, something which he loathed and believed that he did poorly. Several of his students recognised that he took little interest in excavation, and was not good at much of it, but instead had a "genius for interpreting evidence". Unlike many of his contemporaries, he was scrupulous with writing up and publishing his findings, producing almost annual reports for the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and also ensured that he acknowledged the help of all of his diggers.

His university position meant that he was obliged to undertake archaeological excavations, something which he loathed and believed that he did poorly. Several of his students recognised that he took little interest in excavation, and was not good at much of it, but instead had a "genius for interpreting evidence". Unlike many of his contemporaries, he was scrupulous with writing up and publishing his findings, producing almost annual reports for the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and also ensured that he acknowledged the help of all of his diggers.

His best known excavation was that undertaken from 1927 through to 1930 at the site of Skara Brae

in the Orkney Islands

. Here, he uncovered a Neolithic village in a good state of preservation that had partially been revealed when heavy storms hit the islands. In 1931, he published the results of his excavation in a book, entitled simply Skara Brae. He got on particularly well with the local populace who lived near the Skara Brae site, and is reported that to them "he was every inch the professor" because of his eccentric appearance and habits.

In 1932, Childe, collaborating with anthropologist C. Daryll Forde, excavated two Iron Age hillforts at Earn's Hugh on the Berwickshire

coast, whilst in June 1935 he excavated a promontory fort at Larriban near to Knocksoghey in Northern Ireland. Together with Wallace Thorneycroft, another Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Childe excavated two vitrified Iron Age forts in Scotland, that at Finavon, Angus

(1933–34) and that at Rahoy, Argyllshire (1936–37).

river, recognising it as the natural boundary dividing the Near East from Europe, and subsequently he believed that it was via the Danube that various new technologies travelled westward in antiquity. In The Danube in Prehistory, Childe introduced the concept of an archaeological culture

(which up until then had been largely restrained purely to German academics), to his British counterparts. This concept would revolutionise the way in which archaeologists understood the past, and would come to be widely accepted in future decades.

Childe's next work, The Bronze Age (1930), dealt with the titular Bronze Age

in Europe, and displayed his increasing acceptance of Marxist theory in understanding how society functioned and changed. He believed that metal was the first indispensable article of commerce, and that metal-smiths were therefore full-time professionals who lived off the social surplus. Within a matter of years he had followed this up with a string of further works: The Forest Cultures of Northern Europe: A Study in Evolution and Diffusion (1931), The Continental Affinities of British Neolithic Pottery (1932) and Neolithic Settlement in the West of Scotland (1934).

In 1933, Childe travelled to Asia, visiting Iraq, a place he thought was "great fun", and then India, which he conversely felt was "detestable" because of the hot weather and the extreme poverty faced by the majority of Indians. During this holiday he toured a number of archaeological sites in the two countries, coming to the opinion that much of what he had written in The Most Ancient Near East was outdated, and so he went on to produce a new book on the subject, New Light on the Most Ancient Near East (1935), in which he applied his Marxist-influenced ideas about the economy to his conclusions.

After another publication dealing with Scottish archaeology, Prehistory of Scotland (1935), Childe produced one of the defining books of his career, Man Makes Himself (1936). Influenced by the Marxist view of history, Childe used the work to argue that the usual distinction between (pre-literate) prehistory and (literate) history was a false dichotomy and that human society has progressed through a series of technological, economic and social revolutions. These included the Neolithic Revolution

, when hunter-gatherers began settling down in permanent communities and began farming, through to the Urban Revolution

, when society progressed from a series of small towns through to the first cities, and right up to more recent times, when the Industrial Revolution

drastically changed the nature of production. With the outbreak of the Second World War, Childe was unable to travel across continental Europe, and so focused on producing a book about the prehistoric archaeology of Britain: the result was Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles (1940).

Childe's pessimism surrounding the outcome of the war led to him adopting the belief that "European Civilization – Capitalist and Stalinist

alike – was irrevocably headed for a Dark Age." It was in this state of mind that he produced what he saw as a sequal to Man Makes Himself entitled What Happened in History (1942), a synthesis of human history from the Palaeolithic through to the fall of the Roman Empire

. Although Oxford University Press

offered to publish the work, he instead chose to release the book through Penguin Books

because they would sell it at a cheaper price, something he believed was pivotal to providing his knowledge to "the masses." This was followed by two short works, Progress and Archaeology (1944) and then The Story of Tools (1944), the latter of which was explicitly Marxist and had been written for the Young Communist League

.

in London. He was anxious to return to the capital, where most of his friends and interests were centred, and as such had kept silent over his disapproval of government policies so that he would not be prevented from getting the job as had happened in Australia. The Institute had been founded in 1937, largely by noted archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler

and his wife Tessa, but until 1946 relied primarily upon volunteer lecturers. When Childe worked there, it was located in St John's Lodge, a building in the Inner Circle of Regent's Park

, although would be moved to Gordon Square in Bloomsbury in 1956. At the Institute, Childe worked alongside Wheeler, a figure who was widely known to the general public in Britain through his frequent television appearances and dominant personality. Wheeler had made a name for himself excavating the Indus Valley civilisation sites of Harappa

and Mohenjo-Daro

and unlike Childe was recognised as a particularly good field archaeologist. The duo did not get on particularly well; Wheeler was conservative and right-wing in his political views whilst also being intolerant of the shortcomings of others, something that Childe made an effort never to be. Whilst working at the Institute, Childe took up residence at Lawn Road Flats near to Hampstead

, an apartment block perhaps recommended to him by the popular crime fiction author Agatha Christie

(the wife of his colleague Max Mallowan

), who had lived there during the Second World War.

Students who studied under Childe often remarked that he was a kindly eccentric, but had a great deal of fondness for him, leading them to commission a bust of him from Marjorie Maitland-Howard. He was not however thought of as a particularly good lecturer, often mumbling his words or walking into an adjacent room to find something whilst continuing to give his talk. He was also known to refer to the socialist states in eastern Europe by their full official titles (for instance using "German Democratic Republic" over "East Germany" and "Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

" over "Yugoslavia"), and also referred to east European towns with their Slavonic rather than Germanic names, further confusing his students who were familiar with the latter. He was widely seen as being better at giving tutorials and seminars, where he could devote more time to interacting with his students individually.

Whereas he had been required to undertake much fieldwork and excavation whilst at Edinburgh, at the Institute his position as Director meant that this was not necessary, although he did undertake one excavation at Maes Howe, a Neolithic burial tomb plundered by Early Medieaval Norse raiders, during 1954–55. Meanwhile, in 1949 Childe and his friend O.G.S. Crawford resigned their positions as Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries

Whereas he had been required to undertake much fieldwork and excavation whilst at Edinburgh, at the Institute his position as Director meant that this was not necessary, although he did undertake one excavation at Maes Howe, a Neolithic burial tomb plundered by Early Medieaval Norse raiders, during 1954–55. Meanwhile, in 1949 Childe and his friend O.G.S. Crawford resigned their positions as Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries

in protest at the election of James Mann

to the Presidency following the retirement of Cyril Fox

. They believed that Mann, who was the Keeper of the Tower's Armouries at the Tower of London

, was a poor choice and that Mortimer Wheeler, being an actual prehistorian, should have won the election.

In 1952 a group of British Marxist historians began publishing the periodical Past and Present

, with Childe soon joining the editorial board. Similarly, he became a member of the board for The Modern Quarterly (later The Marxist Quarterly) during the early 1950s, working alongside his old friend Rajani Palme Dutt, who held the position of chairman of the board. He also wrote occasional articles for Palme Dutt's socialist journal, the Labour Monthly, but disagreed with him on the issue of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Palme Dutt had defended the Soviet Union's decision to quash the revolution using military force, but Childe, like many western socialists and Marxists at the time, strongly disagreed that this was an appropriate measure to take. The actions of the Soviet government alienated Childe, who lost his formerly firm faith in Joseph Stalin

's administration, but not his belief in socialism and Marxist theory. Despite the events of 1956, Childe retained a love of the Soviet Union, having visited it on a number of occasions prior, and was involved with the Society for Cultural Relations with the USSR, a satellite body of the Communist Party of Great Britain. He was also the president of the Society's National History and Archaeology Section from the early 1950s until his death. In April 1956, he had been awarded the Gold Medal of the Society of Antiquaries for his services to archaeology.

Whilst working at the Institute, Childe continued writing and publishing books dealing with archaeology and prehistory. History (1947) continued his belief that prehistory and literate history must be viewed together, and adopted a Marxist view of history, whilst Prehistoric Migrations (1950) displayed his views on moderate diffusionism. In 1946 he had also published a paper in the Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, entitled "Archaeology and Anthropology" which argued that the two disciplines must be used in tandem, something that would be widely accepted in the decades following his death.