Charles George Gordon

Encyclopedia

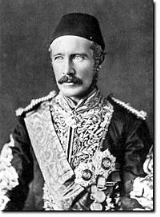

Major-General Charles George Gordon, CB

(28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), known as "Chinese" Gordon, Gordon Pasha

, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British

army officer and administrator.

He saw action in the Crimean War

as an officer in the British army, but he made his military reputation in China

, where he was placed in command of the "Ever Victorious Army

", a force of Chinese soldiers led by European officers. In the early 1860s, Gordon and his men were instrumental in putting down the Taiping Rebellion

, regularly defeating much larger forces. For these accomplishments, he was given the nickname "Chinese" Gordon and honours from both the Emperor of China and the British.

He entered the service of the Khedive

in 1873 (with British government approval) and later became the Governor-General of the Sudan, where he did much to suppress revolts and the slave trade. Exhausted, he resigned and returned to Europe in 1880.

Then a serious revolt broke out in the Sudan, led by a self-proclaimed Mahdi

, Mohammed Ahmed. At the request of the British government, Gordon went to Khartoum

to see to the evacuation of Egyptian soldiers and civilians. Besieged by the Mahdi's forces, Gordon organised a defence that gained him the admiration of the British public, though not the government, which had not wished to become involved. Only when public pressure to act had become too great was a relief force reluctantly sent. It arrived two days after the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed.

, London

, a son of Major-General Henry William Gordon (1786–1865) and Elizabeth (Enderby) Gordon (1792–1873). He was educated at Fullands School, Taunton, Somerset, Taunton School

, and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. He was commissioned in 1852 as a second lieutenant

in the Royal Engineers

, completing his training at Chatham. He was promoted to full lieutenant in 1854.

Gordon was first assigned to construct fortifications at Milford Haven

, Pembrokeshire

, Wales

. When the Crimean War

began, he was sent to the Russian Empire, arriving at Balaklava

in January 1855. He was put to work in the Siege of Sevastopol and took part in the assault of the Redan

from 18 June to 8 September. Gordon took part in the expedition to Kinburn

, and returned to Sevastopol

at the war's end. For his services in the Crimea, he received the Crimean war medal and clasp

. Following the peace

, he was attached to an international commission to mark the new border between the Russian Empire

and the Ottoman Empire

in Bessarabia

. He continued surveying, marking of the boundary into Asia Minor

. Gordon returned to Britain in late 1858, and was appointed as an instructor at Chatham. He was promoted to captain in April 1859.

and the Taiping Rebellion

). He arrived at Tianjin

in September of that year. He was present at the occupation of Beijing

and destruction of the Summer Palace

. The British forces occupied northern China until April 1862, then under General Charles William Dunbar Staveley

, withdrew to Shanghai to protect the European settlement from the rebel Taiping army.

Following the successes in the 1850s in the provinces of Guangxi

, Hunan

and Hubei

, and the capture of Nanjing

in 1853 the rebel advance had slowed. For some years, the Taipings gradually advanced eastwards, but eventually they came close enough to Shanghai to alarm the European inhabitants. A militia of Europeans and Asians

was raised for the defence of the city and placed under the command of an American, Frederick Townsend Ward

, and occupied the country to the west of Shanghai.

The British arrived at a crucial time. Staveley decided to clear the rebels within 30 miles (48.3 km) of Shanghai in cooperation with Ward and a small French force. Gordon was attached to his staff as engineer officer. Jiading

, northwest suburb of present Shanghai, Qingpu and other towns were occupied, and the area was fairly cleared of rebels by the end of 1862.

Ward was killed in the Battle of Cixi

and his successor H. A. Burgevine, an American was disliked by the Imperial Chinese authorities. Li Hongzhang

, the governor of the Jiangsu

province, requested Staveley to appoint a British officer to command the contingent. Staveley selected Gordon, who had been made a brevet

major in December 1862 and the nomination was approved by the British government. In March 1863 Gordon took command of the force at Songjiang

, which had received the name of "Ever Victorious Army

". Without waiting to reorganize his troops, Gordon led them at once to the relief of Chansu

, a town 40 miles north-west of Shanghai. The relief was successfully accomplished and Gordon had quickly won respect from his troops. His task was made easier by the highly innovative military ideas Ward had implemented in the Ever Victorious Army.

He then reorganised his force and advanced against Kunshan

, which was captured at considerable loss. Gordon then took his force through the country, seizing towns until, with the aid of Imperial troops, the city of Suzhou

was captured in November. Following a dispute with Li Hongzhang over the execution of rebel leaders, Gordon withdrew his force from Suzhou and remained inactive at Kunshan until February 1864. Gordon then made a rapprochement with Li and visited him in order to arrange for further operations. The "Ever-Victorious Army" resumed its high tempo advance, culminating in the capture of Changzhou Fu

(see also Battle of Changzhou

) in May, the principal military base of the Taipings in the region. Gordon then returned to Kunshan and disbanded his army.

The Emperor promoted Gordon to the rank of titu (提督: "Chief commander of Jiangsu province"), decorated him with the imperial yellow jacket

, and raised him to Qing's Viscount

of second class. The British Army

promoted Gordon to Lieutenant-Colonel and he was made a Companion of the Bath. He also gained the popular nickname "Chinese Gordon".

, Kent

, the erection of forts for the defence of the River Thames

. In October 1871, he was appointed British representative on the international commission to maintain the navigation of the mouth of the River Danube

, with headquarters at Galatz

. In 1872, Gordon was sent to inspect the British military cemeteries in the Crimea

, and when passing through Constantinople

he made the acquaintance of the Prime Minister of Egypt

, who opened negotiations for Gordon to serve under the Khedive

, Ismail Pasha. In 1873, Gordon received a definite offer from the Khedive, which he accepted with the consent of the British government, and proceeded to Egypt early in 1874. Gordon was made a colonel in the Egyptian army.

The Egyptian authorities had been extending their control southwards since the 1820s. An expedition was sent up the White Nile

, under Sir Samuel Baker

, which reached Khartoum

in February 1870 and Gondokoro

in June 1871. Baker met with great difficulties and managed little beyond establishing a few posts along the Nile

. The Khedive asked for Gordon to succeed Baker as governor of the region. After a short stay in Cairo

, Gordon proceeded to Khartoum via Suakin and Berber. From Khartoum, he proceeded up the White Nile to Gondokoro.

Gordon remained in the Gondokoro provinces until October 1876. He had succeeded in establishing a line of way stations from the Sobat confluence on the White Nile to the frontier of Uganda

, where he proposed to open a route from Mombasa

. In 1874 he built the station at Dufile

on the Albert Nile to reassemble steamers carried there past rapids for the exploration of Lake Albert. Considerable progress was made in the suppression of the slave

trade. However, Gordon had come into conflict with the Egyptian governor of Khartoum and Sudan

. The clash led to Gordon informing the Khedive that he did not wish to return to the Sudan and he left for London

. Ismail Pasha wrote to him saying that he had promised to return, and that he expected him to keep his word. Gordon agreed to return to Cairo, and was asked to take the position of Governor-General of the entire Sudan, which he accepted.

, precipitating increasing unrest. Relations between Egypt and Abyssinia (later renamed Ethiopia

) had become strained due to a dispute over the district of Bogos, and war broke out in 1875. An Egyptian expedition was completely defeated near Gundet. A second and larger expedition, under Prince Hassan, was sent the following year and was routed at Gura. Matters then remained quiet until March 1877, when Gordon proceeded to Massawa, hoping to make peace with the Abyssinian

s. He went up to Bogos and wrote to the king proposing terms. However, he received no reply as the king had gone southwards to fight with the Shoa. Gordon, seeing that the Abyssinian difficulty could wait, proceeded to Khartoum.

An insurrection

had broken out in Darfur

and Gordon went to deal with it. The insurgents were numerous and he saw that diplomacy had a better chance of success. Gordon, accompanied only by an interpreter, rode into the enemy camp to discuss the situation. This bold move proved successful, as many of the insurgents joined him, though the remainder retreated to the south. Gordon visited the provinces of Berber and Dongola, and then returned to the Abyssinian frontier, before ending up back in Khartoum in January 1878. Gordon was summoned to Cairo, and arrived in March to be appointed president of a commission. The khedive was deposed in 1879 in favour of his son.

Gordon returned south and proceeded to Harrar, south of Abyssinia, and, finding the administration in poor standing, dismissed the governor. He then returned to Khartoum, and went again into Darfur to suppress the slave traders. His subordinate, Gessi Pasha

, fought with great success in the Bahr-el-Ghazal

district in putting an end to the revolt there. Gordon then tried another peace mission to Abyssinia. The matter ended with Gordon's imprisonment and transfer to Massawa. Thence he returned to Cairo and resigned his Sudan appointment. He was exhausted by years of incessant work.

In the early months of 1880, he recovered for a couple of weeks in the Hotel du Faucon in Lausanne, famous for its views on Lake Geneva and because celebrities such as Giuseppe Garibaldi

(one of Gordon's heroes, possibly one of the reasons Gordon had chosen this hotel) had stayed there.

in Brussels

and was invited to take charge of the Congo Free State

. In April, the government of the Cape Colony

offered him the position of commandant of the Cape local forces. In May, the Marquess of Ripon

, who had been given the post of Governor-General of India

, asked Gordon to go with him as private secretary. Gordon accepted the offer, but shortly after arriving in India he resigned.

Hardly had he resigned when he was invited by Sir Robert Hart, 1st Baronet

, inspector-general of customs in China, to Beijing. He arrived in China in July and met Li Hongzhang, and learned that there was risk of war with Russia. Gordon proceeded to Beijing and used all his influence to ensure peace.

Gordon returned to Britain and rented an apartment on 8 Victoria Grove in London. But in April 1881 left for Mauritius

as Commanding Royal Engineer. He remained in Mauritius until March 1882, when he was promoted to major-general. He was sent to the Cape to aid in settling affairs in Basutoland

. He returned to the United Kingdom after only a few months.

Being unemployed, Gordon decided to go to Palestine

, a country he had long desired to visit; he would remain there for a year (1882–83). After his visit, Gordon suggested in his book Reflections in Palestine a different location for Golgotha

, the site of Christ

's crucifixion

. The site lies north of the traditional site at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

and is now known as "The Garden Tomb

", or sometimes as "Gordon's Calvary". Gordon's interest was prompted by his religious beliefs, as he had become an evangelical Christian

in 1854.

King Leopold II then asked him again to take charge of the Congo Free State. He accepted and returned to London to make preparations, but soon after his arrival the British requested that he proceed immediately to the Sudan, where the situation had deteriorated badly after his departure — another revolt had arisen, led by the self-proclaimed Mahdi

, Mohammed Ahmed

.

. By September 1882, the Sudanese position had grown perilous. In December 1883, the British government ordered Egypt to abandon the Sudan, but that was difficult to carry out, as it involved the withdrawal of thousands of Egyptian soldiers, civilian employees, and their families. The British government asked Gordon to proceed to Khartoum to report on the best method of carrying out the evacuation.

Gordon started for Cairo in January 1884, accompanied by Lt. Col. J. D. H. Stewart

. At Cairo, he received further instructions from Sir Evelyn Baring

, and was appointed governor-general with executive powers. Travelling through Korosko and Berber, he arrived at Khartoum on February 18, where he offered his earlier foe, the slaver-king Sebehr Rahma, release from prison in exchange for leading troops against Ahmed. Gordon commenced the task of sending the women and children and the sick and wounded to Egypt, and about 2,500 had been removed before the Mahdi's forces closed in. Gordon hoped to have the influential local leader Sebehr Rahma appointed to take control of Sudan, but the British government refused to support a former slaver.

The advance of the rebels against Khartoum was combined with a revolt in the eastern Sudan; the Egyptian troops at Suakin were repeatedly defeated. A British force was sent to Suakin under General Sir Gerald Graham

, and forced the rebels away in several hard-fought actions. Gordon urged that the road from Suakin to Berber be opened, but his request was refused by the government in London, and in April Graham and his forces were withdrawn and Gordon and the Sudan were abandoned. The garrison at Berber surrendered in May, and Khartoum was completely isolated.

Gordon organised the defence of Khartoum. A siege by the Mahdist forces started on March 18, 1884. The British had decided to abandon the Sudan, but it was clear that Gordon had other plans, and the public increasingly called for a relief expedition. It was not until August that the government decided to take steps to relieve Gordon, and only by November was the British relief force, called the Nile Expedition

, or, more popularly, the Khartoum Relief Expedition or Gordon Relief Expedition (a title that Gordon strongly deprecated), under the command of Field Marshal Garnet Wolseley, ready.

The force consisted of two groups, a "flying column" of camel-borne troops from Wadi Halfa

. The troops reached Korti towards the end of December, and arrived at Metemma on January 20, 1885. There they found four gunboats which had been sent north by Gordon four months earlier, and prepared them for the trip back up the Nile. On January 24, two of the steamers started for Khartoum, but on arriving there on January 28, they found that the city had been captured and Gordon had been killed two days previously (two days before his 52nd birthday).

The British press criticised the army for arriving two days late but it was later argued that the Mahdi's forces had good intelligence and if the army had advanced earlier, the attack on Khartoum would also have come earlier.

(1966) with Charlton Heston

as Gordon.

Gordon was killed around dawn fighting the warriors of the Mahdi. As recounted in Bernard M. Allen’s article “How Khartoum Fell” (1941), the Mahdi had given strict orders to his three Khalifas not to kill Gordon. However, the orders were not obeyed. Gordon died on the steps of a stairway in the northwestern corner of the palace, where he and his personal bodyguard, Agha Khalil Orphali, had been firing at the enemy. Orphali was knocked unconscious and did not see Gordon die. When he woke up again that afternoon, he found Gordon's body covered with flies and the head cut off. Reference is made to an 1889 account of the General surrendering his sword

to a senior Mahdist officer, then being struck and subsequently speared in the side as he rolled down the staircase. When Gordon's head was unwrapped at the Mahdi's feet, he ordered the head transfixed between the branches of a tree "....where all who passed it could look in disdain, children could throw stones at it and the hawks of the desert could sweep and circle above." After the reconquest of the Sudan, in 1898, several attempts were made to locate Gordon's remains, but in vain.

Many of Gordon's papers were saved and collected by two of his sisters, Helen Clark Gordon, who married Gordon's medical colleague in China, Dr. Moffit, and Mary, who married Gerald Henry Blunt. Gordon's papers, as well as some of his grandfather's (Samuel Enderby III), were accepted by the British Library around 1937.

in West End, Surrey

near Woking

was dedicated to his memory. Gordon was supposedly Queen Victoria's favourite general, hence the fact that the school was commissioned by Queen Victoria

. Gordon Lodge, close to Queen Victoria's Osborne House

on the Isle of Wight, was demolished in the 1980s to be replaced by a retirement complex of the same name.

Gordon's memory (as well as his work in supervising the town's riverside fortifications) is commemorated in Gravesend

; the embankment of the Riverside Leisure Area is known as the Gordon Promenade, while Khartoum Place lies just to the south. Located in the town centre of his birthplace of Woolwich is General Gordon Square.

In 1888 a statue of Gordon by Hamo Thornycroft

was erected in Trafalgar Square

, London

, exactly halfway between the two fountains. It was removed in 1943. In a House of Commons speech on 5 May 1948, then opposition leader Winston Churchill

spoke out in favour of the statue's return to its original location: “Is the right honourable Gentleman (the Minister of Works) aware that General Gordon was not only a military commander, who gave his life for his country, but, in addition, was considered very widely throughout this country as a model of a Christian hero, and that very many cherished ideals are associated with his name? Would not the right honourable Gentleman consider whether this statue [...] might not receive special consideration [...]? General Gordon was a figure outside and above the ranks of military and naval commanders.” However, in 1953 the statue minus a large slice of its pedestal was reinstalled on the Victoria Embankment

, in front of the newly built Ministry of Defence.

An identical statue by Thornycroft - but with the pedestal intact - is located in a small park called Gordon Reserve, near Parliament House

in Melbourne

, Australia

(a statue of the unrelated poet, Adam Lindsay Gordon

, lies in the same reserve). Funded by donations from 100,000 citizens, it was unveiled in 1889.

The Corps of Royal Engineers, Gordon's own Corps, commissioned a statue of Gordon on a camel. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy

in 1890 and then erected in Brompton Barracks, Chatham, the home of the Royal School of Military Engineering, where it still stands. Much later a second casting was made. In 1902 it was placed at the junction of St Martin's Lane and Charing Cross Road in London. In 1904 it was moved to Khartoum, where it stood at the intersection of Gordon Avenue and Victoria Avenue, 200 meters south of the new palace that had been built in 1899. It was removed in 1958, shortly after the Sudan became independent. This is the figure which, since 1960, stands at the Gordon's School in Woking.

The Royal Engineers Museum adjoining the barracks has many artefacts relating to Gordon including personal possessions. There are also memorials to Gordon in the nearby Rochester Cathedral

.

A statue of General Gordon can be found in Aberdeen

outside the main gates of The Robert Gordon University.

In St Paul's Cathedral

, London, a slightly larger than life-size effigy of Gordon is flanked by a relief commemorating general Herbert Stewart

(1843–1885), who had commanded the "flying column" of camel-borne troops, and who was mortally wounded on 19 January 1885. Stewart's grave can still be found at the Jakdul Wells in the Bayuda Desert. The commander of the Khartoum Relief Expedition 1884-1885, Sir Garnet Wolseley, lies buried beneath the effigies of Gordon and Stewart in the crypt of St Paul's.

There is a bust of Gordon in Westminster Abbey

, just to the left of the main entrance when entering the building, above a doorway.

A rather fine stained-glass portrait is to be found on the main stairs of the Booloominbah building at the University of New England

, in Armidale, New South Wales

, Australia

.

The Fairey Gordon

Bomber

, designed to act as part of the RAF's colonial 'aerial police force' in the Imperial territories that he helped conquer (India and North Africa), was named in his honour.

The City of Geelong, Australia created a memorial in the form of the Gordon Technical College, which was later renamed the Gordon Institute of Technology. Part of the Institute continues under the name Gordon Institute of TAFE

and the remainder was amalgamated with the Geelong State College to become Deakin University

.

The suburbs of Gordon

in northern Sydney

and Gordon Park in northern Brisbane were named after General Gordon, as was the former Shire of Gordon

in Victoria, Australia. An elementary school in Vancouver, British Columbia, is named after General Gordon. Gordon Memorial College

is a school in Khartoum. A grammar school

in Medway

, Kent

, England

, called Sir Joseph Williamson's Mathematical School

, has a house named in honour of Charles George Gordon, called Gordon.

In Gloucester

, there is a rugby union club called Gordon League which was formed in 1888 by Agnes Jane Waddy. The club plays in Western Counties North. The Gordon League Fishing Club uses the rugby club as it home. Gordon's Boys' Clubs were organised after General Gordon's death and the Gloucester Gordon League may be the last remaining example.

The Church Missionary Society (CMS) work in Sudan was undertaken under the name of the Gordon Memorial Mission. This was a very evangelical branch of CMS and was able to start work in Sudan in 1900 as soon as the Anglo-Eygyptian Condominium took control after the fall of Khartoum in 1899. In 1885 at a meeting in London, £3,000 were allocated to a Gordon Memorial Mission in Sudan.

In Khartoum, there is a small shrine to Gordon in the back of Republican Palace Museum. The museum was previously the city's largest Anglican Church, and is now dedicated primarily to gifts to Sudanese Heads of State. In the rear corner, there is a plaque commemorating those who fell with Gordon during the siege. Above is an encomium in brass letters, most of which have long since fallen off the wall leaving only silhouettes. It reads "Charles George Gordan, Servant of Jesus Christ, Whose Labour Was Not in Vain with the Lord".

in Kent

.

He was an eccentric who believed amongst other things that the Earth was enclosed in a hollow sphere with God's throne directly above the altar of the Temple in Jerusalem, the Devil inhabiting the opposite point of the globe near Pitcairn Island in the Pacific. He also believed that the Garden of Eden

was on the island of Praslin

in the Seychelles

.

Gordon believed in reincarnation

. In 1877, he wrote in a letter: "This life is only one of a series of lives which our incarnated part has lived. I have little doubt of our having pre-existed; and that also in the time of our pre-existence we were actively employed. So, therefore, I believe in our active employment in a future life, and I like the thought.”

played Gordon in the 1966 epic film Khartoum

, which deals with the siege.

Gordon's heroics have also been drawn on in the 2005 novel The Triumph of the Sun by Wilbur Smith

.

The 2008 novel After Omdurman by John Ferry deals with the reconquest of the Sudan and highlights how the Anglo-Egyptian army was driven to avenge Gordon's death.

Many biographies have been written of Gordon, most of them of a highly hagiographic

nature. Gordon is one of the four subjects discussed in Eminent Victorians

by Lytton Strachey

, one of the first texts about Gordon that portrays some of his (supposed) weaknesses. Another attempt to debunk Gordon was Anthony Nutting's Gordon, Martyr & Misfit (1966). In his "Mission to Khartum - The Apotheosis of General Gordon" (1969) John Marlowe portrays Gordon as "a colourful eccentric - a soldier of fortune, a skilled guerrilla leader, a religious crank, a minor philantropist, a gadfly buzzing about on the outskirts of public life" who would have been no more than a footnote in today's history books, had it not been for "his mission to Khartoum and the manner of his death" which were elevated by the media "into a kind of contemporary Passion Play".

More balanced biographies are Charley Gordon - An Eminent Victorian Reassessed (1978) by Charles Chenevix Trench and Gordon - the Man Behind the Legend (1988) by John Pollock.

In "Khartoum - The Ultimate Imperial Adventure" (2005) Michael Asher

puts Gordon's works in the Sudan

in a broad context. Asher concludes: "He did not save the country from invasion or disaster, but among the British heroes of all ages, there is perhaps no other who stands out so prominently as an individualist, a man ready to die for his principles. Here was one man among men who did not do what he was told, but what he believed to be right. In a world moving inexorably towards conformity, it would be well to remember Gordon of Khartoum."

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

(28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), known as "Chinese" Gordon, Gordon Pasha

Pasha

Pasha or pascha, formerly bashaw, was a high rank in the Ottoman Empire political system, typically granted to governors, generals and dignitaries. As an honorary title, Pasha, in one of its various ranks, is equivalent to the British title of Lord, and was also one of the highest titles in...

, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

army officer and administrator.

He saw action in the Crimean War

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining...

as an officer in the British army, but he made his military reputation in China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, where he was placed in command of the "Ever Victorious Army

Ever Victorious Army

The Ever Victorious Army was the name given to an imperial army in late-19th–century China. The Ever Victorious Army fought for the Qing Dynasty against the rebels of the Nien and Taiping Rebellions....

", a force of Chinese soldiers led by European officers. In the early 1860s, Gordon and his men were instrumental in putting down the Taiping Rebellion

Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion was a widespread civil war in southern China from 1850 to 1864, led by heterodox Christian convert Hong Xiuquan, who, having received visions, maintained that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ, against the ruling Manchu-led Qing Dynasty...

, regularly defeating much larger forces. For these accomplishments, he was given the nickname "Chinese" Gordon and honours from both the Emperor of China and the British.

He entered the service of the Khedive

Khedive

The term Khedive is a title largely equivalent to the English word viceroy. It was first used, without official recognition, by Muhammad Ali Pasha , the Wāli of Egypt and Sudan, and vassal of the Ottoman Empire...

in 1873 (with British government approval) and later became the Governor-General of the Sudan, where he did much to suppress revolts and the slave trade. Exhausted, he resigned and returned to Europe in 1880.

Then a serious revolt broke out in the Sudan, led by a self-proclaimed Mahdi

Mahdi

In Islamic eschatology, the Mahdi is the prophesied redeemer of Islam who will stay on Earth for seven, nine or nineteen years- before the Day of Judgment and, alongside Jesus, will rid the world of wrongdoing, injustice and tyranny.In Shia Islam, the belief in the Mahdi is a "central religious...

, Mohammed Ahmed. At the request of the British government, Gordon went to Khartoum

Khartoum

Khartoum is the capital and largest city of Sudan and of Khartoum State. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile flowing north from Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile flowing west from Ethiopia. The location where the two Niles meet is known as "al-Mogran"...

to see to the evacuation of Egyptian soldiers and civilians. Besieged by the Mahdi's forces, Gordon organised a defence that gained him the admiration of the British public, though not the government, which had not wished to become involved. Only when public pressure to act had become too great was a relief force reluctantly sent. It arrived two days after the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed.

Early life

Gordon was born in WoolwichWoolwich

Woolwich is a district in south London, England, located in the London Borough of Greenwich. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.Woolwich formed part of Kent until 1889 when the County of London was created...

, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, a son of Major-General Henry William Gordon (1786–1865) and Elizabeth (Enderby) Gordon (1792–1873). He was educated at Fullands School, Taunton, Somerset, Taunton School

Taunton School

Taunton School is a co-educational independent school in the county town of Taunton in Somerset in South West England. It serves boarding and day-school pupils from the ages of 13 to 18....

, and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. He was commissioned in 1852 as a second lieutenant

Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces.- United Kingdom and Commonwealth :The rank second lieutenant was introduced throughout the British Army in 1871 to replace the rank of ensign , although it had long been used in the Royal Artillery, Royal...

in the Royal Engineers

Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually just called the Royal Engineers , and commonly known as the Sappers, is one of the corps of the British Army....

, completing his training at Chatham. He was promoted to full lieutenant in 1854.

Gordon was first assigned to construct fortifications at Milford Haven

Milford Haven

Milford Haven is a town and community in Pembrokeshire, Wales. It is situated on the north side of the Milford Haven Waterway, a natural harbour used as a port since the Middle Ages. The town was founded in 1790 on the north side of the Waterway, from which it takes its name...

, Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire is a county in the south west of Wales. It borders Carmarthenshire to the east and Ceredigion to the north east. The county town is Haverfordwest where Pembrokeshire County Council is headquartered....

, Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

. When the Crimean War

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining...

began, he was sent to the Russian Empire, arriving at Balaklava

Balaklava

Balaklava is a former city on the Crimean peninsula and part of the city of Sevastopol which carries a special administrative status in Ukraine. It was a city in its own right until 1957 when it was formally incorporated into the municipal borders of Sevastopol by the Soviet government...

in January 1855. He was put to work in the Siege of Sevastopol and took part in the assault of the Redan

Redan

Redan is a term related to fortifications. It is a work in a V-shaped salient angle toward an expected attack...

from 18 June to 8 September. Gordon took part in the expedition to Kinburn

Battle of Kinburn (1855)

The Battle of Kinburn/Kil-Bouroun was a naval engagement during the final stage of the Crimean War. It took place on the tip of the Kinburn Peninsula on 17 October 1855...

, and returned to Sevastopol

Sevastopol

Sevastopol is a city on rights of administrative division of Ukraine, located on the Black Sea coast of the Crimea peninsula. It has a population of 342,451 . Sevastopol is the second largest port in Ukraine, after the Port of Odessa....

at the war's end. For his services in the Crimea, he received the Crimean war medal and clasp

Crimea Medal

The Crimea Medal was a campaign medal approved in 1854, for issue to officers and men of British units which fought in the Crimean War of 1854-56 against Russia....

. Following the peace

Treaty of Paris (1856)

The Treaty of Paris of 1856 settled the Crimean War between Russia and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire, Second French Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The treaty, signed on March 30, 1856 at the Congress of Paris, made the Black Sea neutral territory, closing it to all...

, he was attached to an international commission to mark the new border between the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

and the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

in Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

. He continued surveying, marking of the boundary into Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

. Gordon returned to Britain in late 1858, and was appointed as an instructor at Chatham. He was promoted to captain in April 1859.

China

In 1860 Gordon volunteered to serve in China (see the Second Opium WarSecond Opium War

The Second Opium War, the Second Anglo-Chinese War, the Second China War, the Arrow War, or the Anglo-French expedition to China, was a war pitting the British Empire and the Second French Empire against the Qing Dynasty of China, lasting from 1856 to 1860...

and the Taiping Rebellion

Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion was a widespread civil war in southern China from 1850 to 1864, led by heterodox Christian convert Hong Xiuquan, who, having received visions, maintained that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ, against the ruling Manchu-led Qing Dynasty...

). He arrived at Tianjin

Tianjin

' is a metropolis in northern China and one of the five national central cities of the People's Republic of China. It is governed as a direct-controlled municipality, one of four such designations, and is, thus, under direct administration of the central government...

in September of that year. He was present at the occupation of Beijing

Beijing

Beijing , also known as Peking , is the capital of the People's Republic of China and one of the most populous cities in the world, with a population of 19,612,368 as of 2010. The city is the country's political, cultural, and educational center, and home to the headquarters for most of China's...

and destruction of the Summer Palace

Old Summer Palace

The Old Summer Palace, known in China as Yuan Ming Yuan , and originally called the Imperial Gardens, was a complex of palaces and gardens in Beijing...

. The British forces occupied northern China until April 1862, then under General Charles William Dunbar Staveley

Charles William Dunbar Staveley

General Sir Charles William Dunbar Staveley GCB was a British Army officer.-Early life:He was born at Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, the son of Lt-General William Staveley and Sarah Mather, and educated at the Scottish military and naval academy, Edinburgh.-Career:He was commissioned as second...

, withdrew to Shanghai to protect the European settlement from the rebel Taiping army.

Following the successes in the 1850s in the provinces of Guangxi

Guangxi

Guangxi, formerly romanized Kwangsi, is a province of southern China along its border with Vietnam. In 1958, it became the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China, a region with special privileges created specifically for the Zhuang people.Guangxi's location, in...

, Hunan

Hunan

' is a province of South-Central China, located to the south of the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and south of Lake Dongting...

and Hubei

Hubei

' Hupeh) is a province in Central China. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Lake Dongting...

, and the capture of Nanjing

Nanjing

' is the capital of Jiangsu province in China and has a prominent place in Chinese history and culture, having been the capital of China on several occasions...

in 1853 the rebel advance had slowed. For some years, the Taipings gradually advanced eastwards, but eventually they came close enough to Shanghai to alarm the European inhabitants. A militia of Europeans and Asians

Asian people

Asian people or Asiatic people is a term with multiple meanings that refers to people who descend from a portion of Asia's population.- Central Asia :...

was raised for the defence of the city and placed under the command of an American, Frederick Townsend Ward

Frederick Townsend Ward

Frederick Townsend Ward was an American sailor, mercenary, and soldier of fortune famous for his military victories for Imperial China during the Taiping Rebellion.-Early life:...

, and occupied the country to the west of Shanghai.

The British arrived at a crucial time. Staveley decided to clear the rebels within 30 miles (48.3 km) of Shanghai in cooperation with Ward and a small French force. Gordon was attached to his staff as engineer officer. Jiading

Jiading

Jiading may refer to:*Jiading District, in Shanghai, China*Jiading, Kaohsiung, township in Kaohsiung County, Taiwan*Roman Catholic Diocese of Jiading, diocese located in Chongqing, China...

, northwest suburb of present Shanghai, Qingpu and other towns were occupied, and the area was fairly cleared of rebels by the end of 1862.

Ward was killed in the Battle of Cixi

Battle of Cixi

The Battle of Cixi or Battle of Tzeki was a decisive victory for Qing imperial forces led by the American soldier of fortune, Frederick Townsend Ward against Taiping Rebels in late Qing Dynasty China. By 1862 Ward, who recently scored several victories for the imperial forces, had raised an army...

and his successor H. A. Burgevine, an American was disliked by the Imperial Chinese authorities. Li Hongzhang

Li Hongzhang

Li Hongzhang or Li Hung-chang , Marquis Suyi of the First Class , GCVO, was a leading statesman of the late Qing Empire...

, the governor of the Jiangsu

Jiangsu

' is a province of the People's Republic of China, located along the east coast of the country. The name comes from jiang, short for the city of Jiangning , and su, for the city of Suzhou. The abbreviation for this province is "苏" , the second character of its name...

province, requested Staveley to appoint a British officer to command the contingent. Staveley selected Gordon, who had been made a brevet

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

major in December 1862 and the nomination was approved by the British government. In March 1863 Gordon took command of the force at Songjiang

Songjiang

Songjiang may refer to the following in China:* Songjiang District , a suburban district of Shanghai, formerly Songjiang County* Songjiang , former province, merged into Heilongjiang in 1954Towns * Songjiang, Antu County, Jilin...

, which had received the name of "Ever Victorious Army

Ever Victorious Army

The Ever Victorious Army was the name given to an imperial army in late-19th–century China. The Ever Victorious Army fought for the Qing Dynasty against the rebels of the Nien and Taiping Rebellions....

". Without waiting to reorganize his troops, Gordon led them at once to the relief of Chansu

Changshu

Changshu is a county-level city under the jurisdiction of Suzhou, and is located in the south-eastern part of eastern-China’s Jiangsu Province as well as the Yangtze River Delta...

, a town 40 miles north-west of Shanghai. The relief was successfully accomplished and Gordon had quickly won respect from his troops. His task was made easier by the highly innovative military ideas Ward had implemented in the Ever Victorious Army.

He then reorganised his force and advanced against Kunshan

Kunshan

Kunshan is a satellite city in the greater Suzhou region. Administratively, it is a county-level city within the prefecture-level city of Suzhou. It is located in southeastearn part of Jiangsu Province, China, adjacent to Jiangsu's border with the Shanghai Municipality.The total area of Kunshan...

, which was captured at considerable loss. Gordon then took his force through the country, seizing towns until, with the aid of Imperial troops, the city of Suzhou

Suzhou

Suzhou , previously transliterated as Su-chou, Suchow, and Soochow, is a major city located in the southeast of Jiangsu Province in Eastern China, located adjacent to Shanghai Municipality. The city is situated on the lower reaches of the Yangtze River and on the shores of Taihu Lake and is a part...

was captured in November. Following a dispute with Li Hongzhang over the execution of rebel leaders, Gordon withdrew his force from Suzhou and remained inactive at Kunshan until February 1864. Gordon then made a rapprochement with Li and visited him in order to arrange for further operations. The "Ever-Victorious Army" resumed its high tempo advance, culminating in the capture of Changzhou Fu

Changzhou

Changzhou is a prefecture-level city in southern Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It was previously known as Yanling, Lanling, Jinling, and Wujin. Located on the southern bank of the Yangtze River, Changzhou borders the provincial capital of Nanjing to the west, Zhenjiang to the...

(see also Battle of Changzhou

Battle of Changzhou

Battle of Changzhou occurred during the Taiping Rebellion. It was won by the Qing Dynasty, who regained control over all of Jiangsu....

) in May, the principal military base of the Taipings in the region. Gordon then returned to Kunshan and disbanded his army.

The Emperor promoted Gordon to the rank of titu (提督: "Chief commander of Jiangsu province"), decorated him with the imperial yellow jacket

Imperial yellow jacket

The imperial yellow jacket was a symbol of high honour during China's Qing Dynasty. As yellow was a forbidden color, representing the Emperor, the jacket was given only to high-ranking officials and to the Emperor's body guards.-Wearing the jacket:...

, and raised him to Qing's Viscount

Viscount

A viscount or viscountess is a member of the European nobility whose comital title ranks usually, as in the British peerage, above a baron, below an earl or a count .-Etymology:...

of second class. The British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

promoted Gordon to Lieutenant-Colonel and he was made a Companion of the Bath. He also gained the popular nickname "Chinese Gordon".

Service with the Khedive

Gordon returned to Britain and commanded the Royal Engineers' efforts around GravesendGravesend, Kent

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, on the south bank of the Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. It is the administrative town of the Borough of Gravesham and, because of its geographical position, has always had an important role to play in the history and communications of this part of...

, Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

, the erection of forts for the defence of the River Thames

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

. In October 1871, he was appointed British representative on the international commission to maintain the navigation of the mouth of the River Danube

Danube

The Danube is a river in the Central Europe and the Europe's second longest river after the Volga. It is classified as an international waterway....

, with headquarters at Galatz

Galatz

Galatz may refer to:* Yiddish and German name of Galaţi, a town in Romania* Galil Tzalafim , a sniper version of the Israeli IMI Galil assault rifle* Galey Tzahal , an abbreviation of the Israel Army Radio network* Galgalatz...

. In 1872, Gordon was sent to inspect the British military cemeteries in the Crimea

Crimea

Crimea , or the Autonomous Republic of Crimea , is a sub-national unit, an autonomous republic, of Ukraine. It is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea, occupying a peninsula of the same name...

, and when passing through Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

he made the acquaintance of the Prime Minister of Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, who opened negotiations for Gordon to serve under the Khedive

Khedive

The term Khedive is a title largely equivalent to the English word viceroy. It was first used, without official recognition, by Muhammad Ali Pasha , the Wāli of Egypt and Sudan, and vassal of the Ottoman Empire...

, Ismail Pasha. In 1873, Gordon received a definite offer from the Khedive, which he accepted with the consent of the British government, and proceeded to Egypt early in 1874. Gordon was made a colonel in the Egyptian army.

The Egyptian authorities had been extending their control southwards since the 1820s. An expedition was sent up the White Nile

White Nile

The White Nile is a river of Africa, one of the two main tributaries of the Nile from Egypt, the other being the Blue Nile. In the strict meaning, "White Nile" refers to the river formed at Lake No at the confluence of the Bahr al Jabal and Bahr el Ghazal rivers...

, under Sir Samuel Baker

Samuel Baker

Sir Samuel White Baker, KCB, FRS, FRGS was a British explorer, officer, naturalist, big game hunter, engineer, writer and abolitionist. He also held the titles of Pasha and Major-General in the Ottoman Empire and Egypt. He served as the Governor-General of the Equatorial Nile Basin between Apr....

, which reached Khartoum

Khartoum

Khartoum is the capital and largest city of Sudan and of Khartoum State. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile flowing north from Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile flowing west from Ethiopia. The location where the two Niles meet is known as "al-Mogran"...

in February 1870 and Gondokoro

Gondokoro

Gondokoro was a trading-station on the east bank of the White Nile in Southern Sudan, 750 miles south of Khartoum. Its importance lay in the fact that it was within a few miles of the limit of navigability of the Nile from Khartoum upstream...

in June 1871. Baker met with great difficulties and managed little beyond establishing a few posts along the Nile

Nile

The Nile is a major north-flowing river in North Africa, generally regarded as the longest river in the world. It is long. It runs through the ten countries of Sudan, South Sudan, Burundi, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda and Egypt.The Nile has two major...

. The Khedive asked for Gordon to succeed Baker as governor of the region. After a short stay in Cairo

Cairo

Cairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

, Gordon proceeded to Khartoum via Suakin and Berber. From Khartoum, he proceeded up the White Nile to Gondokoro.

Gordon remained in the Gondokoro provinces until October 1876. He had succeeded in establishing a line of way stations from the Sobat confluence on the White Nile to the frontier of Uganda

Uganda

Uganda , officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. Uganda is also known as the "Pearl of Africa". It is bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by South Sudan, on the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by...

, where he proposed to open a route from Mombasa

Mombasa

Mombasa is the second-largest city in Kenya. Lying next to the Indian Ocean, it has a major port and an international airport. The city also serves as the centre of the coastal tourism industry....

. In 1874 he built the station at Dufile

Dufile

Dufile was originally a fort built by Emin Pasha, the Governor of Equatoria, in 1879; it is located on the Albert Nile just inside Uganda, close to a site chosen in 1874 by then-Colonel Charles George Gordon to assemble steamers that were carried there overland. Emin and A.J...

on the Albert Nile to reassemble steamers carried there past rapids for the exploration of Lake Albert. Considerable progress was made in the suppression of the slave

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

trade. However, Gordon had come into conflict with the Egyptian governor of Khartoum and Sudan

Sudan

Sudan , officially the Republic of the Sudan , is a country in North Africa, sometimes considered part of the Middle East politically. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the...

. The clash led to Gordon informing the Khedive that he did not wish to return to the Sudan and he left for London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. Ismail Pasha wrote to him saying that he had promised to return, and that he expected him to keep his word. Gordon agreed to return to Cairo, and was asked to take the position of Governor-General of the entire Sudan, which he accepted.

Governor-General of the Sudan

As governor, Gordon faced a variety of challenges. During the 1870s, European initiatives against the slave trade caused an economic crisis in northern SudanSudan

Sudan , officially the Republic of the Sudan , is a country in North Africa, sometimes considered part of the Middle East politically. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the...

, precipitating increasing unrest. Relations between Egypt and Abyssinia (later renamed Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

) had become strained due to a dispute over the district of Bogos, and war broke out in 1875. An Egyptian expedition was completely defeated near Gundet. A second and larger expedition, under Prince Hassan, was sent the following year and was routed at Gura. Matters then remained quiet until March 1877, when Gordon proceeded to Massawa, hoping to make peace with the Abyssinian

Abyssinian

Abyssinian may refer to:* Abyssinian, Habesha people and things from parts of Ethiopia and Eritrea, formerly known as Abyssinia* Abyssinian , a cat breed* Abyssinian, a breed of guinea pig* The Abyssinians, a Jamaican roots reggae group...

s. He went up to Bogos and wrote to the king proposing terms. However, he received no reply as the king had gone southwards to fight with the Shoa. Gordon, seeing that the Abyssinian difficulty could wait, proceeded to Khartoum.

An insurrection

Insurgency

An insurgency is an armed rebellion against a constituted authority when those taking part in the rebellion are not recognized as belligerents...

had broken out in Darfur

Darfur

Darfur is a region in western Sudan. An independent sultanate for several hundred years, it was incorporated into Sudan by Anglo-Egyptian forces in 1916. The region is divided into three federal states: West Darfur, South Darfur, and North Darfur...

and Gordon went to deal with it. The insurgents were numerous and he saw that diplomacy had a better chance of success. Gordon, accompanied only by an interpreter, rode into the enemy camp to discuss the situation. This bold move proved successful, as many of the insurgents joined him, though the remainder retreated to the south. Gordon visited the provinces of Berber and Dongola, and then returned to the Abyssinian frontier, before ending up back in Khartoum in January 1878. Gordon was summoned to Cairo, and arrived in March to be appointed president of a commission. The khedive was deposed in 1879 in favour of his son.

Gordon returned south and proceeded to Harrar, south of Abyssinia, and, finding the administration in poor standing, dismissed the governor. He then returned to Khartoum, and went again into Darfur to suppress the slave traders. His subordinate, Gessi Pasha

Romolo Gessi

Romolo Gessi , also called Gessi Pasha, was an Italian soldier and an explorer of north-east Africa, especially Sudan and the Nile River....

, fought with great success in the Bahr-el-Ghazal

Bahr el Ghazal

The Bahr el Ghazal is a region of western South Sudan. Its name comes from the river Bahr el Ghazal.- Geography :The region consists of the states of Northern Bahr el Ghazal, Western Bahr el Ghazal, Lakes, and Warrap. It borders Central African Republic to the west...

district in putting an end to the revolt there. Gordon then tried another peace mission to Abyssinia. The matter ended with Gordon's imprisonment and transfer to Massawa. Thence he returned to Cairo and resigned his Sudan appointment. He was exhausted by years of incessant work.

In the early months of 1880, he recovered for a couple of weeks in the Hotel du Faucon in Lausanne, famous for its views on Lake Geneva and because celebrities such as Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Garibaldi was an Italian military and political figure. In his twenties, he joined the Carbonari Italian patriot revolutionaries, and fled Italy after a failed insurrection. Garibaldi took part in the War of the Farrapos and the Uruguayan Civil War leading the Italian Legion, and...

(one of Gordon's heroes, possibly one of the reasons Gordon had chosen this hotel) had stayed there.

Other offers

In March 1880, Gordon visited King Leopold II of BelgiumLeopold II of Belgium

Leopold II was the second king of the Belgians. Born in Brussels the second son of Leopold I and Louise-Marie of Orléans, he succeeded his father to the throne on 17 December 1865 and remained king until his death.Leopold is chiefly remembered as the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free...

in Brussels

Brussels

Brussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

and was invited to take charge of the Congo Free State

Congo Free State

The Congo Free State was a large area in Central Africa which was privately controlled by Leopold II, King of the Belgians. Its origins lay in Leopold's attracting scientific, and humanitarian backing for a non-governmental organization, the Association internationale africaine...

. In April, the government of the Cape Colony

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony, part of modern South Africa, was established by the Dutch East India Company in 1652, with the founding of Cape Town. It was subsequently occupied by the British in 1795 when the Netherlands were occupied by revolutionary France, so that the French revolutionaries could not take...

offered him the position of commandant of the Cape local forces. In May, the Marquess of Ripon

George Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon

George Frederick Samuel Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon KG, GCSI, CIE, PC , known as Viscount Goderich from 1833 to 1859 and as the Earl de Grey and Ripon from 1859 to 1871, was a British politician who served in every Liberal cabinet from 1861 until his death forty-eight years later.-Background...

, who had been given the post of Governor-General of India

Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India was the head of the British administration in India, and later, after Indian independence, the representative of the monarch and de facto head of state. The office was created in 1773, with the title of Governor-General of the Presidency of Fort William...

, asked Gordon to go with him as private secretary. Gordon accepted the offer, but shortly after arriving in India he resigned.

Hardly had he resigned when he was invited by Sir Robert Hart, 1st Baronet

Sir Robert Hart, 1st Baronet

Sir Robert Hart, 1st Baronet, GCMG , was a British consular official in China, who served as the second Inspector General of China's Imperial Maritime Custom Service from 1863 to 1911.-Early life:...

, inspector-general of customs in China, to Beijing. He arrived in China in July and met Li Hongzhang, and learned that there was risk of war with Russia. Gordon proceeded to Beijing and used all his influence to ensure peace.

Gordon returned to Britain and rented an apartment on 8 Victoria Grove in London. But in April 1881 left for Mauritius

Mauritius

Mauritius , officially the Republic of Mauritius is an island nation off the southeast coast of the African continent in the southwest Indian Ocean, about east of Madagascar...

as Commanding Royal Engineer. He remained in Mauritius until March 1882, when he was promoted to major-general. He was sent to the Cape to aid in settling affairs in Basutoland

Basutoland

Basutoland or officially the Territory of Basutoland, was a British Crown colony established in 1884 after the Cape Colony's inability to control the territory...

. He returned to the United Kingdom after only a few months.

Being unemployed, Gordon decided to go to Palestine

Palestine

Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

, a country he had long desired to visit; he would remain there for a year (1882–83). After his visit, Gordon suggested in his book Reflections in Palestine a different location for Golgotha

Calvary

Calvary or Golgotha was the site, outside of ancient Jerusalem’s early first century walls, at which the crucifixion of Jesus is said to have occurred. Calvary and Golgotha are the English names for the site used in Western Christianity...

, the site of Christ

Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth , commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity...

's crucifixion

Crucifixion of Jesus

The crucifixion of Jesus and his ensuing death is an event that occurred during the 1st century AD. Jesus, who Christians believe is the Son of God as well as the Messiah, was arrested, tried, and sentenced by Pontius Pilate to be scourged, and finally executed on a cross...

. The site lies north of the traditional site at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, also called the Church of the Resurrection by Eastern Christians, is a church within the walled Old City of Jerusalem. It is a few steps away from the Muristan....

and is now known as "The Garden Tomb

Garden Tomb

The Garden Tomb , located in Jerusalem, outside the city walls and close to the Damascus Gate, is a rock-cut tomb considered by some to be the site of the burial and resurrection of Jesus, and to be adjacent to Golgotha, in contradistinction to the traditional site for these—the Church of the Holy...

", or sometimes as "Gordon's Calvary". Gordon's interest was prompted by his religious beliefs, as he had become an evangelical Christian

Evangelicalism

Evangelicalism is a Protestant Christian movement which began in Great Britain in the 1730s and gained popularity in the United States during the series of Great Awakenings of the 18th and 19th century.Its key commitments are:...

in 1854.

King Leopold II then asked him again to take charge of the Congo Free State. He accepted and returned to London to make preparations, but soon after his arrival the British requested that he proceed immediately to the Sudan, where the situation had deteriorated badly after his departure — another revolt had arisen, led by the self-proclaimed Mahdi

Mahdi

In Islamic eschatology, the Mahdi is the prophesied redeemer of Islam who will stay on Earth for seven, nine or nineteen years- before the Day of Judgment and, alongside Jesus, will rid the world of wrongdoing, injustice and tyranny.In Shia Islam, the belief in the Mahdi is a "central religious...

, Mohammed Ahmed

Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah was a religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, on June 29, 1881, proclaimed himself as the Mahdi or messianic redeemer of the Islamic faith...

.

The Mahdist revolt

The Egyptian forces in the Sudan were insufficient to cope with the rebels, and the northern government was occupied in the suppression of the Urabi RevoltUrabi Revolt

The Urabi Revolt or Orabi Revolt , also known as the Orabi Revolution, was an uprising in Egypt in 1879-82 against the Khedive and European influence in the country...

. By September 1882, the Sudanese position had grown perilous. In December 1883, the British government ordered Egypt to abandon the Sudan, but that was difficult to carry out, as it involved the withdrawal of thousands of Egyptian soldiers, civilian employees, and their families. The British government asked Gordon to proceed to Khartoum to report on the best method of carrying out the evacuation.

Gordon started for Cairo in January 1884, accompanied by Lt. Col. J. D. H. Stewart

John Donald Hamill Stewart

Colonel John Donald Hamill Stewart was a British soldier. He accompanied General Gordon to Khartoum in 1884 as his assistant. He died in September 1884 attempting to run the blockade from the besieged city at the hands of the Manasir tribesmen and followers of Muhammad Ahmad Al-Mahdi.-...

. At Cairo, he received further instructions from Sir Evelyn Baring

Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer

Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer, GCB, OM, GCMG, KCSI, CIE, PC, FRS , was a British statesman, diplomat and colonial administrator....

, and was appointed governor-general with executive powers. Travelling through Korosko and Berber, he arrived at Khartoum on February 18, where he offered his earlier foe, the slaver-king Sebehr Rahma, release from prison in exchange for leading troops against Ahmed. Gordon commenced the task of sending the women and children and the sick and wounded to Egypt, and about 2,500 had been removed before the Mahdi's forces closed in. Gordon hoped to have the influential local leader Sebehr Rahma appointed to take control of Sudan, but the British government refused to support a former slaver.

The advance of the rebels against Khartoum was combined with a revolt in the eastern Sudan; the Egyptian troops at Suakin were repeatedly defeated. A British force was sent to Suakin under General Sir Gerald Graham

Gerald Graham

Lieutenant General Sir Gerald Graham, VC GCB GCMG was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.-Early life:He was born in Acton, Middlesex, and after studying at...

, and forced the rebels away in several hard-fought actions. Gordon urged that the road from Suakin to Berber be opened, but his request was refused by the government in London, and in April Graham and his forces were withdrawn and Gordon and the Sudan were abandoned. The garrison at Berber surrendered in May, and Khartoum was completely isolated.

Gordon organised the defence of Khartoum. A siege by the Mahdist forces started on March 18, 1884. The British had decided to abandon the Sudan, but it was clear that Gordon had other plans, and the public increasingly called for a relief expedition. It was not until August that the government decided to take steps to relieve Gordon, and only by November was the British relief force, called the Nile Expedition

Nile Expedition

The Nile Expedition, sometimes called the Gordon Relief Expedition , was a British mission to relieve Major-General Charles George Gordon at Khartoum, Sudan. Gordon had been sent to the Sudan to help Egyptians evacuate from Sudan after Britain decided to abandon the country in the face of a...

, or, more popularly, the Khartoum Relief Expedition or Gordon Relief Expedition (a title that Gordon strongly deprecated), under the command of Field Marshal Garnet Wolseley, ready.

The force consisted of two groups, a "flying column" of camel-borne troops from Wadi Halfa

Wadi Halfa

Wadi Halfa is a city in the state of Northern, in northern Sudan, on the shores of Lake Nubia . It is the terminus of a rail line from Khartoum and the point where goods are transferred from rail to ferries going down the Lake Nasser...

. The troops reached Korti towards the end of December, and arrived at Metemma on January 20, 1885. There they found four gunboats which had been sent north by Gordon four months earlier, and prepared them for the trip back up the Nile. On January 24, two of the steamers started for Khartoum, but on arriving there on January 28, they found that the city had been captured and Gordon had been killed two days previously (two days before his 52nd birthday).

The British press criticised the army for arriving two days late but it was later argued that the Mahdi's forces had good intelligence and if the army had advanced earlier, the attack on Khartoum would also have come earlier.

Death

The manner of his death is uncertain but it was romanticised in a popular painting by George William Joy - General Gordon's Last Stand (1885, currently in the Leeds City Art Gallery) - and again in the film KhartoumKhartoum (film)

Khartoum is a 1966 film written by Robert Ardrey and directed by Basil Dearden. It stars Charlton Heston as General Gordon and Laurence Olivier as the Mahdi and is based on Gordon's defence of the Sudanese city of Khartoum from the forces of the Mahdist army during the Siege of Khartoum.Khartoum...

(1966) with Charlton Heston

Charlton Heston

Charlton Heston was an American actor of film, theatre and television. Heston is known for heroic roles in films such as The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor, El Cid, and Planet of the Apes...

as Gordon.

Gordon was killed around dawn fighting the warriors of the Mahdi. As recounted in Bernard M. Allen’s article “How Khartoum Fell” (1941), the Mahdi had given strict orders to his three Khalifas not to kill Gordon. However, the orders were not obeyed. Gordon died on the steps of a stairway in the northwestern corner of the palace, where he and his personal bodyguard, Agha Khalil Orphali, had been firing at the enemy. Orphali was knocked unconscious and did not see Gordon die. When he woke up again that afternoon, he found Gordon's body covered with flies and the head cut off. Reference is made to an 1889 account of the General surrendering his sword

Sword

A sword is a bladed weapon used primarily for cutting or thrusting. The precise definition of the term varies with the historical epoch or the geographical region under consideration...

to a senior Mahdist officer, then being struck and subsequently speared in the side as he rolled down the staircase. When Gordon's head was unwrapped at the Mahdi's feet, he ordered the head transfixed between the branches of a tree "....where all who passed it could look in disdain, children could throw stones at it and the hawks of the desert could sweep and circle above." After the reconquest of the Sudan, in 1898, several attempts were made to locate Gordon's remains, but in vain.

Many of Gordon's papers were saved and collected by two of his sisters, Helen Clark Gordon, who married Gordon's medical colleague in China, Dr. Moffit, and Mary, who married Gerald Henry Blunt. Gordon's papers, as well as some of his grandfather's (Samuel Enderby III), were accepted by the British Library around 1937.

Memorials

Gordon's SchoolGordon's School

Gordon's School is a voluntary-aided comprehensive secondary school in Woking, Surrey. It was founded in 1886 by public subscription as a memorial to Gordon of Khartoum, and officer of the Corps of Royal Engineers, who was killed in 1885. The school website claims that the idea came from Queen...

in West End, Surrey

Surrey

Surrey is a county in the South East of England and is one of the Home Counties. The county borders Greater London, Kent, East Sussex, West Sussex, Hampshire and Berkshire. The historic county town is Guildford. Surrey County Council sits at Kingston upon Thames, although this has been part of...

near Woking

Woking

Woking is a large town and civil parish that shares its name with the surrounding local government district, located in the west of Surrey, UK. It is part of the Greater London Urban Area and the London commuter belt, with frequent trains and a journey time of 24 minutes to Waterloo station....

was dedicated to his memory. Gordon was supposedly Queen Victoria's favourite general, hence the fact that the school was commissioned by Queen Victoria

Victoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India....

. Gordon Lodge, close to Queen Victoria's Osborne House

Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, UK. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat....

on the Isle of Wight, was demolished in the 1980s to be replaced by a retirement complex of the same name.

Gordon's memory (as well as his work in supervising the town's riverside fortifications) is commemorated in Gravesend

Gravesend, Kent

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, on the south bank of the Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. It is the administrative town of the Borough of Gravesham and, because of its geographical position, has always had an important role to play in the history and communications of this part of...

; the embankment of the Riverside Leisure Area is known as the Gordon Promenade, while Khartoum Place lies just to the south. Located in the town centre of his birthplace of Woolwich is General Gordon Square.

In 1888 a statue of Gordon by Hamo Thornycroft

Hamo Thornycroft

Sir William "Hamo" Thornycroft, RA was a British sculptor, responsible for several London landmarks.-Biography:...

was erected in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square is a public space and tourist attraction in central London, England, United Kingdom. At its centre is Nelson's Column, which is guarded by four lion statues at its base. There are a number of statues and sculptures in the square, with one plinth displaying changing pieces of...

, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, exactly halfway between the two fountains. It was removed in 1943. In a House of Commons speech on 5 May 1948, then opposition leader Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

spoke out in favour of the statue's return to its original location: “Is the right honourable Gentleman (the Minister of Works) aware that General Gordon was not only a military commander, who gave his life for his country, but, in addition, was considered very widely throughout this country as a model of a Christian hero, and that very many cherished ideals are associated with his name? Would not the right honourable Gentleman consider whether this statue [...] might not receive special consideration [...]? General Gordon was a figure outside and above the ranks of military and naval commanders.” However, in 1953 the statue minus a large slice of its pedestal was reinstalled on the Victoria Embankment

Victoria Embankment

The Victoria Embankment is part of the Thames Embankment, a road and river walk along the north bank of the River Thames in London. Victoria Embankment extends from the City of Westminster into the City of London.-Construction:...

, in front of the newly built Ministry of Defence.

An identical statue by Thornycroft - but with the pedestal intact - is located in a small park called Gordon Reserve, near Parliament House

Parliament House, Melbourne