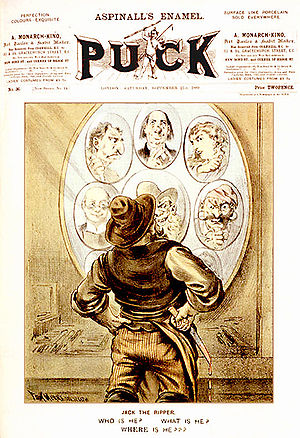

List of proposed Jack the Ripper suspects

Encyclopedia

East End of London

The East End of London, also known simply as the East End, is the area of London, England, United Kingdom, east of the medieval walled City of London and north of the River Thames. Although not defined by universally accepted formal boundaries, the River Lea can be considered another boundary...

from August to November 1888 were blamed on an unidentified assailant known as Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper

"Jack the Ripper" is the best-known name given to an unidentified serial killer who was active in the largely impoverished areas in and around the Whitechapel district of London in 1888. The name originated in a letter, written by someone claiming to be the murderer, that was disseminated in the...

. Since that time, the identity of the killer or killers has been hotly debated, and over one hundred Jack the Ripper suspects have been proposed. Though many theories have been advanced, experts find none widely persuasive, and some can hardly be taken seriously at all.

Contemporaneous police opinion

Metropolitan Police ServiceMetropolitan Police Service

The Metropolitan Police Service is the territorial police force responsible for Greater London, excluding the "square mile" of the City of London which is the responsibility of the City of London Police...

files show that their investigation into the serial killings encompassed eleven separate murders between 1888 and 1891, known in the police docket as the "Whitechapel murders". Five of these—the murders of Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols was one of the Whitechapel murder victims. Her death has been attributed to the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have killed and mutilated five women in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.- Life...

, Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman , born Eliza Ann Smith, was a victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated five women in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.-Life and background:Annie Chapman was born Eliza Ann Smith...

, Elizabeth Stride

Elizabeth Stride

Elizabeth "Long Liz" Stride is believed to be the third victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer called Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated prostitutes in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.She was nicknamed "Long Liz"...

, Catherine Eddowes

Catherine Eddowes

Catherine Eddowes was one of the victims in the Whitechapel murders. She was the second person killed on the night of Sunday 30 September 1888, a night which already had seen the murder of Elizabeth Stride less than an hour earlier...

, and Mary Jane Kelly

Mary Jane Kelly

Mary Jane Kelly , also known as "Marie Jeanette" Kelly, "Fair Emma", "Ginger" and "Black Mary", is widely believed to be the fifth and final victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated prostitutes in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to...

—are generally agreed to be the work of a single killer, known as "Jack the Ripper". They occurred between August and November 1888 within a few streets of each other, and are collectively called the "canonical five". The six other murders—those of Emma Elizabeth Smith

Emma Elizabeth Smith

Emma Elizabeth Smith was a prostitute and murder victim of mysterious origins in late-19th century London. Her killing was the first of the Whitechapel murders, and it is possible she was a victim of the notorious serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, though this is considered unlikely by most...

, Martha Tabram

Martha Tabram

Martha Tabram was an English prostitute whose killing was the second of the Whitechapel murders in late 19th century London...

, Rose Mylett, Alice McKenzie, Frances Coles, and an unidentified woman—have been linked with Jack the Ripper to varying degrees.

The swiftness of the attacks, and the manner of the mutilations performed on some of the bodies, which included disembowelment and removal of organs, led to speculation that the murderer had the skills of a physician or butcher. However, others disagreed strongly, and thought the wounds too crude to be professional. The alibis of local butchers and slaughterers were investigated, with the result that they were eliminated from the enquiry. Over 2000 people were interviewed, "upwards of 300" people were investigated, and 80 people were detained.

During the course of their investigations of the murders, police regarded several men as strong suspects, though none was ever formally charged.

Montague John Druitt

Dorset

Dorset , is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The county town is Dorchester which is situated in the south. The Hampshire towns of Bournemouth and Christchurch joined the county with the reorganisation of local government in 1974...

-born barrister who worked to supplement his income as an assistant schoolmaster in Blackheath, London

Blackheath, London

Blackheath is a district of South London, England. It is named from the large open public grassland which separates it from Greenwich to the north and Lewisham to the west...

, until his dismissal shortly before his suicide

Suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Suicide is often committed out of despair or attributed to some underlying mental disorder, such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, alcoholism, or drug abuse...

by drowning in 1888. His decomposed body was found in the Thames near Chiswick

Chiswick

Chiswick is a large suburb of west London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It is located on a meander of the River Thames, west of Charing Cross and is one of 35 major centres identified in the London Plan. It was historically an ancient parish in the county of Middlesex, with...

on 31 December 1888. Some modern authors suggest that Druitt was homosexual, that he was dismissed because of this and that it may have driven him to suicide. However, his mother and his grandmother both suffered mental health

Mental health

Mental health describes either a level of cognitive or emotional well-being or an absence of a mental disorder. From perspectives of the discipline of positive psychology or holism mental health may include an individual's ability to enjoy life and procure a balance between life activities and...

problems, and it is possible that he was dismissed because of an underlying hereditary psychiatric illness. His death shortly after the last canonical murder (which took place on 9 November 1888) led Assistant Chief Constable

Chief Constable

Chief constable is the rank used by the chief police officer of every territorial police force in the United Kingdom except for the City of London Police and the Metropolitan Police, as well as the chief officers of the three 'special' national police forces, the British Transport Police, Ministry...

Sir Melville Macnaghten

Melville MacNaghten

Sir Melville Leslie Macnaghten CB KPM was Assistant Commissioner of the London Metropolitan Police from 1903 to 1913....

to name him as a suspect in a memorandum of 23 February 1894. However, Macnaghten incorrectly described the 31-year-old barrister as a 41-year-old doctor. On 1 September, the day after the first canonical murder, Druitt was in Dorset playing cricket, and most experts now believe that the killer was local to Whitechapel, whereas Druitt lived miles away on the other side of the Thames in Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

. Inspector Frederick Abberline

Frederick Abberline

Frederick George Abberline was a Chief Inspector for the London Metropolitan Police and was a prominent police figure in the investigation into the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.-Early life:...

appeared to dismiss Druitt as a serious suspect on the basis that the only evidence against him was the coincidental timing of his suicide shortly after a murder considered by some to be the final one in the series.

Seweryn Kłosowski alias George Chapman

Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman , born Eliza Ann Smith, was a victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated five women in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.-Life and background:Annie Chapman was born Eliza Ann Smith...

) (14 December 1865 – 7 April 1903) was born in Poland, but emigrated to the United Kingdom sometime between 1887 and 1888, shortly before the start of the murders. Between 1893 and 1894 he assumed the name of Chapman. He successively poisoned three of his wives, and was hanged for his crimes in 1903. At the time of the Ripper murders, he lived in Whitechapel, London, where he had been working as a barber. According to H. L. Adam, who wrote a book on the poisonings in 1930, Chapman was Inspector Frederick Abberline

Frederick Abberline

Frederick George Abberline was a Chief Inspector for the London Metropolitan Police and was a prominent police figure in the investigation into the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.-Early life:...

's favoured suspect, and the Pall Mall Gazette reported that Abberline suspected Chapman after his conviction. However, others disagree that Chapman is a likely culprit as he murdered his three wives with poison, and it is uncommon (though not unheard of) for a serial killer to make such a drastic change in modus operandi

Modus operandi

Modus operandi is a Latin phrase, approximately translated as "mode of operation". The term is used to describe someone's habits or manner of working, their method of operating or functioning...

.

Aaron Kosminski

Aaron Kosminski (born Aron Mordke Kozminski; 11 September 1865 – 24 March 1919) was a Polish Jew who was admitted to Colney Hatch Lunatic AsylumColney Hatch Lunatic Asylum

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum was an early psychiatric hospital located in Colney Hatch in what is now the London Borough of Barnet. The hospital was in operation from 1851 to 1993....

in 1891. "Kosminski" (without a forename) was named as a suspect by Melville Macnaghten in his 1894 memorandum and by former Chief Inspector Donald Swanson

Donald Swanson

Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson was born in Thurso in Scotland, and was a senior police officer in the Metropolitan Police in London during the notorious Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.-Early life:...

in handwritten comments in the margin of his copy of Assistant Commissioner

Assistant Commissioner

Assistant commissioner is a rank used in many police forces across the globe. It is also a rank used in revenue administrations in many countries.-Australia:...

Sir Robert Anderson

Sir Robert Anderson

Sir Robert Anderson, KCB , was the second Assistant Commissioner of the London Metropolitan Police, from 1888 to 1901. He was also an intelligence officer, theologian and writer.-Early life and education:...

's memoirs. Anderson wrote that a Polish Jew had been identified as the Ripper but that no prosecution was possible because the witness was also Jewish and refused to testify against a fellow Jew. Some authors are skeptical of this, while others use it in their theories. In his memorandum, Macnaghten stated that no one was ever identified as the Ripper, which directly contradicts Anderson's recollection. Kosminski lived in Whitechapel; however, he was largely harmless in the asylum. His insanity took the form of auditory hallucinations, a paranoid fear of being fed by other people, and a refusal to wash or bathe.

Michael Ostrog

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

n-born professional con man

Confidence trick

A confidence trick is an attempt to defraud a person or group by gaining their confidence. A confidence artist is an individual working alone or in concert with others who exploits characteristics of the human psyche such as dishonesty and honesty, vanity, compassion, credulity, irresponsibility,...

. He used numerous aliases and disguises. Among his many dubious claims was that he had once been a surgeon in the Russian Navy

Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy refers to the Tsarist fleets prior to the February Revolution.-First Romanovs:Under Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich, construction of the first three-masted ship, actually built within Russia, was completed in 1636. It was built in Balakhna by Danish shipbuilders from Holstein...

. He was mentioned as a suspect by Macnaghten, who joined the case in 1889, the year after the "canonical five" victims were killed. Researchers have failed to find evidence that he had committed crimes any more serious than fraud and theft. Author Philip Sugden discovered prison records showing that Ostrog was jailed for petty offences in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

during the Ripper murders. Ostrog was last mentioned alive in 1904; the date of his death is unknown.

John Pizer

Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols was one of the Whitechapel murder victims. Her death has been attributed to the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have killed and mutilated five women in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.- Life...

and Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman , born Eliza Ann Smith, was a victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated five women in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.-Life and background:Annie Chapman was born Eliza Ann Smith...

in late August and early September 1888 respectively, Police Sergeant William Thicke arrested Pizer on 10 September 1888. Pizer was known as "Leather Apron", and Thicke apparently believed that he had committed a string of minor assaults on prostitutes. In the early days of the Whitechapel murders, many locals suspected that "Leather Apron" was the killer, even though the investigating inspector reported that "there is no evidence whatsoever against him". He was cleared of suspicion when it turned out that he had alibis for two of the murders. He was staying with relatives at the time of one of the canonical murders, and he was talking with a police officer while watching a spectacular fire on the London Docks

London Docks

The London Docks were one of several sets of docks in the historic Port of London. They were constructed in Wapping downstream from the City of London between 1799 and 1815, at a cost exceeding £5½ million. Traditionally ships had docked at wharves on the River Thames, but by this time, more...

at the time of another. Pizer and Thicke had known each other for years, and Pizer implied that his arrest was based on animosity rather than evidence, though he did have a prior conviction for a stabbing offence. Pizer successfully obtained monetary compensation from at least one newspaper that had named him as the murderer. (Thicke himself was accused of being the Ripper by H. T. Haslewood of Tottenham

Tottenham

Tottenham is an area of the London Borough of Haringey, England, situated north north east of Charing Cross.-Toponymy:Tottenham is believed to have been named after Tota, a farmer, whose hamlet was mentioned in the Domesday Book; hence Tota's hamlet became Tottenham...

in a letter to the Home Office

Home Office

The Home Office is the United Kingdom government department responsible for immigration control, security, and order. As such it is responsible for the police, UK Border Agency, and the Security Service . It is also in charge of government policy on security-related issues such as drugs,...

dated 10 September 1889. The presumably malicious accusation was dismissed as without foundation.)

James Thomas Sadler

Sadler was a friend of Frances Coles, the last victim added to the Whitechapel murders police file. Coles was killed with a wound to the throat on 13 February 1891. Sadler was arrested, but there was little evidence against him. Though briefly considered by the police as a Ripper suspect, he was at sea at the time of the earlier murders, and was released without charge. Sadler was named in Macnaghten's 1894 memorandum in connection with Coles' murder. Though Macnaghten thought Sadler "was a man of ungovernable temper and entirely addicted to drinkAlcoholism

Alcoholism is a broad term for problems with alcohol, and is generally used to mean compulsive and uncontrolled consumption of alcoholic beverages, usually to the detriment of the drinker's health, personal relationships, and social standing...

, and the company of the lowest prostitutes", he thought any connection with the Ripper was unlikely.

Francis Tumblety

Misogyny

Misogyny is the hatred or dislike of women or girls. Philogyny, meaning fondness, love or admiration towards women, is the antonym of misogyny. The term misandry is the term for men that is parallel to misogyny...

quack

Quackery

Quackery is a derogatory term used to describe the promotion of unproven or fraudulent medical practices. Random House Dictionary describes a "quack" as a "fraudulent or ignorant pretender to medical skill" or "a person who pretends, professionally or publicly, to have skill, knowledge, or...

. He was connected to the death of one of his patients, but escaped prosecution. In 1865, he was arrested for complicity in the assassination

Abraham Lincoln assassination

The assassination of United States President Abraham Lincoln took place on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, as the American Civil War was drawing to a close. The assassination occurred five days after the commanding General of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee, and his battered Army of...

of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

, but was released without charge. Tumblety was in England in 1888, and was arrested on 7 November, apparently for engaging in homosexuality

Homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic or sexual attraction or behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality refers to "an enduring pattern of or disposition to experience sexual, affectional, or romantic attractions" primarily or exclusively to people of the same...

, which was illegal at the time. Awaiting trial, he fled to France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and then to the United States. Already notorious in the States for his self-promotion and previous criminal charges, his arrest was reported as connected to the Ripper murders. American reports that Scotland Yard tried to extradite

Extradition

Extradition is the official process whereby one nation or state surrenders a suspected or convicted criminal to another nation or state. Between nation states, extradition is regulated by treaties...

him were not confirmed by the British press or the London police, and the New York City Police said, "there is no proof of his complicity in the Whitechapel murders, and the crime for which he is under bond in London is not extraditable". In 1913, Tumblety was mentioned as a Ripper suspect by Chief Inspector John Littlechild

John Littlechild

Detective Chief Inspector John George Littlechild was the first commander of the London Metropolitan Police Special Irish Branch, renamed Special Branch in 1888....

of the Metropolitan Police Service

Metropolitan Police Service

The Metropolitan Police Service is the territorial police force responsible for Greater London, excluding the "square mile" of the City of London which is the responsibility of the City of London Police...

in a letter to journalist and author George R. Sims.

Contemporary press and public opinion

The Whitechapel murders were featured heavily in the media, and attracted the attention of Victorian society at large. Journalists, letter writers, and amateur detectives all suggested names either in press or to the police. Most were not and could not be taken seriously. For example, at the time of the murders Richard MansfieldRichard Mansfield

Richard Mansfield was an English actor-manager best known for his performances in Shakespeare plays, Gilbert and Sullivan operas and for his portrayal of the dual title roles in Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde....

, a famous actor, starred in a theatrical version of Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was a Scottish novelist, poet, essayist and travel writer. His best-known books include Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde....

's book Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The subject matter of horrific murder in the London streets and Mansfield's convincing portrayal led letter writers to accuse him of being the Ripper.

William Henry Bury

Dundee

Dundee is the fourth-largest city in Scotland and the 39th most populous settlement in the United Kingdom. It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firth of Tay, which feeds into the North Sea...

from the East End of London, when he strangled his wife Ellen Elliott, a former prostitute, on 4 February 1889. He inflicted deep wounds to her abdomen after she was dead and packed the body into a trunk. On 10 February, Bury went to the local police and told them his wife had committed suicide. He was arrested, tried, found guilty of her murder, and hanged in Dundee. A link with the Ripper crimes was investigated by police, but Bury denied any connection, despite making a full confession to his wife's homicide. Nevertheless, the hangman, James Berry

James Berry (hangman)

James Berry was an English executioner from 1884 until 1891. Berry was born in Heckmondwike in Yorkshire, where his father worked as a wool-stapler. His most important contribution to the science of hanging was his refinement of the long drop method developed by William Marwood, whom Berry knew...

, promoted the idea that Bury was the Ripper.

Thomas Neill Cream

Glasgow

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

, educated in London and Canada, and entered practice in Canada and later in Chicago, Illinois. In 1881 he was found guilty of the fatal poisoning of his mistress's husband. He was imprisoned in the Illinois State Penitentiary

Joliet Prison

Joliet Correctional Center was a prison in Joliet, Illinois, United States from 1858 to 2002. It is featured in the motion picture The Blues Brothers as the prison from which Jake Blues is released at the beginning of the movie...

in Joliet, Illinois

Joliet, Illinois

Joliet is a city in Will and Kendall Counties in the U.S. state of Illinois, located southwest of Chicago. It is the county seat of Will County. As of the 2010 census, the city was the fourth-most populated in Illinois, with a population of 147,433. It continues to be Illinois' fastest growing...

, from November 1881 until his release on good behaviour on 31 July 1891. He moved to London, where he resumed killing and was soon arrested. He was hanged on 15 November 1892 at Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century, and demolished in 1777...

. According to some sources, his last words were reported as being "I am Jack the...", interpreted to mean Jack the Ripper. However, police officials who attended the execution made no mention of this alleged interrupted confession. As he was still imprisoned at the time of the Ripper murders, most authorities consider it impossible for him to be the culprit. However, Donald Bell suggested that he could have bribed officials and left the prison before his official release, and Sir Edward Marshall-Hall

Edward Marshall-Hall

Sir Edward Marshall Hall, KC, was an English barrister who had a formidable reputation as an orator...

suspected that his prison term may have been served by a look-alike in his place. Such notions are unlikely, and contradict evidence given by the Illinois authorities, newspapers of the time, Cream's solicitors, Cream's family and Cream himself.

Thomas Hayne Cutbush

Thomas Hayne Cutbush (1864–1903) was sent to LambethLambeth

Lambeth is a district of south London, England, and part of the London Borough of Lambeth. It is situated southeast of Charing Cross.-Toponymy:...

Infirmary in 1891 suffering delusions thought to have been caused by syphilis

Syphilis

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum. The primary route of transmission is through sexual contact; however, it may also be transmitted from mother to fetus during pregnancy or at birth, resulting in congenital syphilis...

. After stabbing a woman in the bottom and attempting to stab a second he was pronounced insane and committed to Broadmoor Hospital

Broadmoor Hospital

Broadmoor Hospital is a high-security psychiatric hospital at Crowthorne in the Borough of Bracknell Forest in Berkshire, England. It is the best known of the three high-security psychiatric hospitals in England, the other two being Ashworth and Rampton...

in 1891, where he remained until his death in 1903. The Sun newspaper suggested in a series of articles in 1894 that Cutbush was the Ripper. There is no evidence that police took the idea seriously, and Melville Macnaghten's memorandum naming the three police suspects Druitt, Kosminski and Ostrog was written to refute the idea that Cutbush was the Ripper. Cutbush was the suspect advanced in the 1993 book Jack the Myth by A. P. Wolf, who suggested that Macnaghten wrote his memo to protect Cutbush's uncle who was a fellow police officer.

Frederick Bailey Deeming

Rainhill

Rainhill is a large village and civil parish of the Metropolitan Borough of St Helens, in Merseyside, England.Historically a part of Lancashire, Rainhill was formerly a township within the ecclesiastical parish of Prescot, and hundred of West Derby...

near St. Helens, Lancashire, in 1891. His crimes went undiscovered and later that year he emigrated to Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

with his second wife, whom he then also murdered. Her body was found buried under their house, and the subsequent investigation led to the discovery of the other bodies in England. He was arrested, sent to trial, and found guilty. He boasted in jail that he was Jack the Ripper, but he was either imprisoned or in South Africa

South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

at the time of the Ripper murders. The police denied any connection between Deeming and the Ripper. He was executed by hanging in Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

.

Carl Feigenbaum

Carl Ferdinand Feigenbaum (executed 27 April 1896) was arrested in 1894 in New York CityNew York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

for cutting the throat of Mrs Juliana Hoffmann. After his execution, his lawyer, William Sanford Lawton, claimed that Feigenbaum had admitted to having a hatred of women and a desire to kill and mutilate them. Lawton further stated that he believed Feigenbaum was Jack the Ripper. Though covered by the press at the time, the idea was not pursued for more than a century. Using Lawton's accusation as a base, author Trevor Marriott, a former British murder squad detective, argued that Feigenbaum was responsible for the Ripper murders as well as other murders in the United States and Germany between 1891 and 1894. According to Wolf Vanderlinden, some of the murders listed by Marriott did not actually occur; the newspapers often embellished or created Ripper-like stories to sell copy. Lawton's accusations were disputed by a partner in his legal firm, Hugh O. Pentecost

Hugh O. Pentecost

Hugh Owen Pentecost was a radical American minister, editor, lawyer, and lecturer.- Early life, preaching, and radicalization :Pentecost was born in 1848 at New Harmony, Indiana, to Emma Flower and Hugh Lockett Pentecost...

, and there is no proof that Feigenbaum was in Whitechapel at the time of the murders.

Robert Donston Stephenson

Robert Donston Stephenson (alias Roslyn D'Onston Stephenson) (20 April 1841 – 9 October 1916) was a journalist and writer interested in the occult and black magic. He admitted himself as a patient at the London Hospital in Whitechapel shortly before the murders started, and left shortly after they ceased. He authored a newspaper article, which claimed that black magic was the motive for the killings and alleged that the Ripper was a Frenchman. Stephenson's strange manner and interest in the crimes resulted in an amateur detective reporting him to Scotland Yard on Christmas Eve, 1888. Two days later Stephenson reported his own suspect, a Dr Morgan Davies of the London Hospital. Subsequently he fell under the suspicion of newspaper editor William Thomas SteadWilliam Thomas Stead

William Thomas Stead was an English journalist and editor who, as one of the early pioneers of investigative journalism, became one of the most controversial figures of the Victorian era. His 'New Journalism' paved the way for today's tabloid press...

. In his books on the case, author and historian Melvin Harris argued that Stephenson was a leading suspect, but the police do not appear to have treated either him or Dr Davies as serious suspects.

Proposed by later authors

Suspects proposed years after the murders include virtually anyone remotely connected to the case by contemporary documents, as well as many famous names, who were not considered in the police investigation at all. As everyone alive at the time is now dead, modern authors are free to accuse anyone they can, "without any need for any supporting historical evidence". Most of their suggestions cannot be taken seriously, and include English novelist George GissingGeorge Gissing

George Robert Gissing was an English novelist who published twenty-three novels between 1880 and 1903. From his early naturalistic works, he developed into one of the most accomplished realists of the late-Victorian era.-Early life:...

, British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

, and syphilitic artist Frank Miles

Frank Miles

George Francis "Frank" Miles was a London artist who specialised in pastel portraits of society ladies, also an architect and a keen plantsman.-Life and career:...

.

Joseph Barnett

Lewis Carroll

Pen name

A pen name, nom de plume, or literary double, is a pseudonym adopted by an author. A pen name may be used to make the author's name more distinctive, to disguise his or her gender, to distance an author from some or all of his or her works, to protect the author from retribution for his or her...

of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) (27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898) was the author of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland is an 1865 novel written by English author Charles Lutwidge Dodgson under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. It tells of a girl named Alice who falls down a rabbit hole into a fantasy world populated by peculiar, anthropomorphic creatures...

and Through the Looking-Glass

Through the Looking-Glass

Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There is a work of literature by Lewis Carroll . It is the sequel to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland...

. He was named as a suspect based upon anagram

Anagram

An anagram is a type of word play, the result of rearranging the letters of a word or phrase to produce a new word or phrase, using all the original letters exactly once; e.g., orchestra = carthorse, A decimal point = I'm a dot in place, Tom Marvolo Riddle = I am Lord Voldemort. Someone who...

s which author Richard Wallace devised for his book Jack the Ripper, Light-Hearted Friend

Jack the Ripper, Light-Hearted Friend

Jack the Ripper, Light-Hearted Friend is a 1996 book by Richard Wallace in which Wallace proposed a theory that British author Lewis Carroll, whose real name was Charles L...

. This claim is not taken seriously by scholars.

David Cohen

David Cohen (1865–1889) was a Polish Jew whose incarceration at Colney Hatch Lunatic AsylumColney Hatch Lunatic Asylum

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum was an early psychiatric hospital located in Colney Hatch in what is now the London Borough of Barnet. The hospital was in operation from 1851 to 1993....

roughly coincided with the end of the murders. Described as violently antisocial, the poor East End local was suggested as a suspect by author and Ripperologist Martin Fido

Martin Fido

Martin Austin Fido is a university teacher, true crime writer and broadcaster. His many books include The Crimes, Detection and Death of Jack the Ripper, The Official Encyclopedia of Scotland Yard, and The Murder Guide to London.After leaving Balliol College, Oxford in 1966 where he had been a...

in his book The Crimes, Detection and Death of Jack the Ripper (1987). Fido claimed that the name "David Cohen" was used at the time to refer to a Jewish immigrant who either could not be positively identified or whose name was too difficult for police to spell, in the same fashion that "John Doe

John Doe

The name "John Doe" is used as a placeholder name in a legal action, case or discussion for a male party, whose true identity is unknown or must be withheld for legal reasons. The name is also used to refer to a male corpse or hospital patient whose identity is unknown...

" is used in the United States today. Fido identified Cohen with "Leather Apron" (see John Pizer above), and speculated that Cohen's true identity was Nathan Kaminsky, a bootmaker living in Whitechapel who had been treated at one time for syphilis and who could not be traced after mid-1888—the same time that Cohen appeared. Fido believed that police officials confused the name Kaminsky with Kosminski, resulting in the wrong man coming under suspicion (see Aaron Kosminski above). Cohen exhibited violent, destructive tendencies while at the asylum, and had to be restrained. He died at the asylum in October 1889. In his book The Cases That Haunt Us, former FBI criminal profiler John Douglas

John E. Douglas

John Edward Douglas , is a former special agent with the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation , one of the first criminal profilers, and criminal psychology author.-Early life:...

has asserted that behavioural clues gathered from the murders all point to a person "known to the police as David Cohen ... or someone very much like him".

William Withey Gull

Sir William Withey Gull (31 December 1816 – 29 January 1890) was physician-in-ordinary to Queen VictoriaVictoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India....

. He was named as the Ripper as part of the evolution of the widely discredited Masonic

Freemasonry

Freemasonry is a fraternal organisation that arose from obscure origins in the late 16th to early 17th century. Freemasonry now exists in various forms all over the world, with a membership estimated at around six million, including approximately 150,000 under the jurisdictions of the Grand Lodge...

/royal conspiracy theory outlined in such books as Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution. Coachman John Netley

John Netley

John Charles Netley was a cab driver who is notable because of claims that he was involved in the 'Whitechapel Murders' committed by Jack the Ripper.-Biography:...

has been named as his accomplice. Thanks to the popularity of this theory among fiction writers and for its dramatic nature, Gull shows up as the Ripper in a number of books and films (including the 1988 TV film Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper (1988 TV series)

Jack the Ripper is a 1988 four-part television movie/mini-series portraying a fictionalized account of the hunt for Jack the Ripper, the unidentified serial killer responsible for the Whitechapel murders of 1888...

starring Michael Caine

Michael Caine

Sir Michael Caine, CBE is an English actor. He won Academy Awards for best supporting actor in both Hannah and Her Sisters and The Cider House Rules ....

; and the 2000 graphic novel, compiled from the comic book series that ran from 1991 to 1996, From Hell

From Hell

From Hell is a comic book series by writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell, originally published from 1991 to 1996, speculating upon the identity and motives of Jack the Ripper. The title is taken from the first words of the "From Hell" letter, which some authorities believe was an authentic...

written by Alan Moore

Alan Moore

Alan Oswald Moore is an English writer primarily known for his work in comic books, a medium where he has produced a number of critically acclaimed and popular series, including Watchmen, V for Vendetta, and From Hell...

with art by Eddie Campbell

Eddie Campbell

Eddie Campbell is a Scottish comics artist and cartoonist who now lives in Australia. Probably best known as the illustrator and publisher of From Hell , Campbell is also the creator of the semi-autobiographical Alec stories collected in Alec: The Years Have Pants, and Bacchus , a wry adventure...

, as well as its 2001 subsequent film adaptation

From Hell (film)

From Hell is a 2001 American crime drama horror mystery film directed by the Hughes brothers. It is an adaptation of the comic book series of the same name by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell about the Jack the Ripper murders.-Plot:...

).

George Hutchinson

George Hutchinson was a labourer. On 12 November 1888, he went to the London police to make a statement claiming that on 9 November 1888 he watched the room that Mary Jane Kelly lived in after he saw her with a man of conspicuous appearance. He gave a very detailed description of a suspect despite the darkness of that night. The accuracy of Hutchinson's statement was later disputed among the senior police of the time. Inspector Frederick Abberline, after interviewing Hutchinson, believed that Hutchinson's account was truthful. However, Robert Anderson, head of the CID, later claimed that the only witness who got a good look at the killer was Jewish. Hutchinson was not a Jew, and thus not that witness. Some modern scholars have suggested that Hutchinson was the Ripper himself, trying to confuse the police with a false description, but others suggest he may have just been an attention seeker who made up a story he hoped to sell to the press.James Kelly

James Kelly (no known relation to the Ripper victim Mary Kelly) murdered his wife in 1883 by stabbing her in the neck. Deemed insane, he was committed to the Broadmoor Asylum

Broadmoor Hospital

Broadmoor Hospital is a high-security psychiatric hospital at Crowthorne in the Borough of Bracknell Forest in Berkshire, England. It is the best known of the three high-security psychiatric hospitals in England, the other two being Ashworth and Rampton...

, from which he later escaped in early 1888, using a key he fashioned himself. After the last Ripper murder in London in November 1888, the police searched for Kelly at what had been his residence prior his wife's murder, but they were not able to locate him. In 1927, almost forty years after his escape, he unexpectedly turned himself back in to officials at the Broadmoor Asylum. He died two years later, presumably of natural causes.

A retired NYPD cold-case detective named Ed Norris examined the Jack the Ripper case for a Discovery Channel program called "Jack the Ripper in America." In it, Norris claims that James Kelly was not only Jack the Ripper's real identity, he was also responsible for multiple murders in cities around the United States. Norris highlights a few features of the Kelly story to support his contention. He worked as a furniture upholsterer, a job that requires handiness with a knife. He also claimed to have resided in the United States and left behind a journal that spoke of his strong disapproval of the immorality of prostitutes and of his having been on the "warpath" during his time as a fugitive. Norris claims Kelly was in New York at the time of a Ripper-like murder of a prostitute named Carrie Brown as well as in a number of cities while each experienced, according to Norris, one or two brutal murders of prostitutes while Kelly was there.

James Maybrick

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

cotton merchant. His wife Florence was convicted of poisoning him with arsenic

Arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As, atomic number 33 and relative atomic mass 74.92. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in conjunction with sulfur and metals, and also as a pure elemental crystal. It was first documented by Albertus Magnus in 1250.Arsenic is a metalloid...

in a sensational, and possibly unjust, trial presided over by Sir James Fitzjames Stephen

James Fitzjames Stephen

Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, 1st Baronet was an English lawyer, judge and writer. He was created 1st Baronet Stephen by Queen Victoria.-Early life:...

, the father of another modern suspect James Kenneth Stephen

James Kenneth Stephen

James Kenneth Stephen was an English poet, and tutor to Prince Albert Victor, eldest son of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales.-Early life:...

. In her book, Jack the Ripper: The American Connection author Shirley Harrison asserted James Maybrick was both Jack the Ripper and the Servant Girl Annihilator

Servant Girl Annihilator

An unknown serial killer, popularly known today as the Servant Girl Annihilator, preyed upon the city of Austin, Texas during the years 1884 and 1885...

of Austin, Texas. A diary purportedly by Maybrick, published in the 1990s by Michael Barrett, contains a confession to the Ripper murders. In 1995, Barrett confessed to writing the diary himself, and described the process of counterfeiting the diary in detail. He swore under oath that he and his wife, Anne, had forged it. Anne Barrett, after their divorce, later denied forgery, and their story changed several times over the years. The diary was discredited by historians who pointed to factual errors in relation to some of the crimes, and document experts pronounced the diary a fake; the handwriting does not match that of Maybrick's will, and the ink contains a preservative not marketed until 1974.

Alexander Pedachenko

Alexander Pedachenko (alleged dates 1857–1908) was named in the 1923 memoirs of William Le QueuxWilliam Le Queux

William Tufnell Le Queux was an Anglo-French journalist and writer. He was also a diplomat , a traveller , a flying buff who officiated at the first British air meeting at Doncaster in 1909, and a wireless pioneer who broadcast music from his own station long...

, Things I Know about Kings, Celebrities and Crooks. Le Queux claimed to have seen a manuscript in French written by Rasputin stating that Jack the Ripper was an insane Russian doctor named Alexander Pedachenko, an agent of the Okhrana (the Secret Police of Imperial Russia

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

), whose aim in committing the murders was to discredit Scotland Yard. He was supposedly assisted by two accomplices: "Levitski" and a tailoress called Winberg. However, there is no hard evidence that Pedachenko ever existed, and many parts of the story as recounted by Le Queux fall apart when examined closely. For example, one of the sources named in the manuscript was a London-based Russian journalist called Nideroest, who was known for inventing sensational stories. Reviewers of Le Queux's book were aware of Nideroest's background, and unabashedly referred to him as an "unscrupulous liar". Pedachenko was promoted as a suspect by Donald McCormick

Donald McCormick

George Donald King McCormick was a British journalist and popular historian, who also wrote under the pseudonyms Richard Deacon and Lichade Digen....

, who may have developed the story by adding his own inventions.

Walter Sickert

.jpg)

Donald McCormick

George Donald King McCormick was a British journalist and popular historian, who also wrote under the pseudonyms Richard Deacon and Lichade Digen....

's 1959 book The Identity of Jack the Ripper. Sickert subsequently appeared as a character in the well-known royal/masonic conspiracy theory concocted by Joseph Gorman, who claimed to be Sickert's illegitimate son. The theory was later developed by author Jean Overton Fuller

Jean Overton Fuller

Jean Overton Fuller was a British author best known for her book Madeleine, the story of Noor-un-nisa Inayat Khan, GC, MBE, CdG, an Indian heroine of World War II....

, and by crime novelist Patricia Cornwell

Patricia Cornwell

Patricia Cornwell is a contemporary American crime writer. She is widely known for writing a popular series of novels featuring the heroine Dr. Kay Scarpetta, a medical examiner.-Early life:...

in her book Portrait of a Killer

Portrait of a Killer

Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper—Case Closed is a 2002 nonfiction book by crime novelist Patricia Cornwell which presents the theory that Walter Sickert, a British painter, was the 19th-century serial killer known as Jack the Ripper.Jean Overton Fuller, in her 1990 book Sickert and the Ripper...

. However, Sickert is not considered a serious suspect by most who study the case, and strong evidence shows he was in France at the time of most of the Ripper murders.

Joseph Silver

In 2007 South African historian Charles van OnselenCharles van Onselen

Professor Charles van Onselen is a researcher and historian, based at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. He resides in Johannesburg.He was formerly employed at the University of the Witwatersrand, where he headed the Institute of Advanced Social Research...

claimed, in the book The Fox and the Flies: The World of Joseph Silver, Racketeer and Psychopath, that Joseph Silver, also known as Joseph Lis, a Polish Jew, was Jack the Ripper. Critics note, among other things, that van Onselen provides no evidence that Silver was ever in London during the time of the murders, and that the accusation is based entirely upon speculation. Van Onselen has responded by saying that the number of circumstances involved should make Silver a suspect.

James Kenneth Stephen

Michael Harrison (writer)

Michael Harrison was the pen name of English detective fiction and fantasy author Maurice Desmond Rohan.- Biography :Michael Harrison was born in Milton, Kent, England, on 25 April 1907...

. Harrison dismissed the idea that Albert Victor was the Ripper but instead suggested that Stephen, a poet and one of Albert Victor's tutors from Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Trinity has more members than any other college in Cambridge or Oxford, with around 700 undergraduates, 430 graduates, and over 170 Fellows...

, was a more likely suspect. Harrison's suggestion was based on Stephen's misogynistic writings and on similarities between his handwriting and that of the "From Hell" letter

From Hell letter

The "From Hell" letter is a letter posted in 1888 by a person who claimed to be the serial killer known as Jack the Ripper....

, supposedly written by the Ripper. Harrison supposed that Stephen may have had sexual feelings for Albert Victor, and that Stephen's hatred of women arose from jealousy because Albert Victor preferred female company and did not reciprocate Stephen's feelings. However, Harrison's analysis was rebutted by professional document examiners. There is no proof that Stephen was ever in love with Albert Victor, although he did starve himself to death very shortly after hearing of Albert Victor's death.

In 1978, Frank Spiering further developed the theory in his book Prince Jack, which depicted Albert Victor as the murderer and Stephen as his lover. The book is widely dismissed as a sensational fiction based on previous theories rather than genuine historical research. Spiering claimed to have discovered a copy of some private notes written by another suspect, Sir William Gull, in the library of the New York Academy of Medicine

New York Academy of Medicine

The New York Academy of Medicine was founded in 1847 by a group of leading New York City metropolitan area physicians as a voice for the medical profession in medical practice and public health reform...

and that the notes included a confession by Albert Victor under a state of hypnosis

Hypnosis

Hypnosis is "a trance state characterized by extreme suggestibility, relaxation and heightened imagination."It is a mental state or imaginative role-enactment . It is usually induced by a procedure known as a hypnotic induction, which is commonly composed of a long series of preliminary...

. Spiering further suggested that Albert Victor died due to an overdose of morphine

Morphine

Morphine is a potent opiate analgesic medication and is considered to be the prototypical opioid. It was first isolated in 1804 by Friedrich Sertürner, first distributed by same in 1817, and first commercially sold by Merck in 1827, which at the time was a single small chemists' shop. It was more...

, administered to him on the order of Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and possibly Albert Victor's own father, Edward VII of the United Kingdom

Edward VII of the United Kingdom

Edward VII was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910...

. The New York Academy of Medicine denies possessing the records Spiering mentioned, and when Spiering was offered access to the Royal Archives

Royal Archives

The Royal Archives, also known as the Queen's Archives, are a division of the Royal Household of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom. It is operationally under the control of the Keeper of the Royal Archives, who is customarily the Private Secretary to the Sovereign.Although Sovereigns have kept...

, he retorted: "I don't want to see any files."

Francis Thompson

Francis Thompson (18 December 1859 – 13 November 1907) was a member of the Aesthetic movementAestheticism

Aestheticism was a 19th century European art movement that emphasized aesthetic values more than socio-political themes for literature, fine art, the decorative arts, and interior design...

and influenced the young J. R. R. Tolkien

J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, CBE was an English writer, poet, philologist, and university professor, best known as the author of the classic high fantasy works The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion.Tolkien was Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College,...

, who purchased the Works of Francis Thompson in 1913–14. Perceived as a devout Catholic

Catholicism

Catholicism is a broad term for the body of the Catholic faith, its theologies and doctrines, its liturgical, ethical, spiritual, and behavioral characteristics, as well as a religious people as a whole....

, in 1889 Thompson wrote the short story "Finis Coronat Opus" (Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

: "The End Crowns the Work"). It features a young poet sacrificing women to pagan

Paganism

Paganism is a blanket term, typically used to refer to non-Abrahamic, indigenous polytheistic religious traditions....

gods

Deity

A deity is a recognized preternatural or supernatural immortal being, who may be thought of as holy, divine, or sacred, held in high regard, and respected by believers....

, seeking hell

Hell

In many religious traditions, a hell is a place of suffering and punishment in the afterlife. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hells as endless. Religions with a cyclic history often depict a hell as an intermediary period between incarnations...

's inspiration for his poetry in order to gain the fame he desires. Thompson is alternatively seen as a religious fanatic or a madman committing the actions described in his story. In 1877 Thompson failed the priesthood

Priesthood (Catholic Church)

The ministerial orders of the Catholic Church include the orders of bishops, deacons and presbyters, which in Latin is sacerdos. The ordained priesthood and common priesthood are different in function and essence....

and in the Autumn 1878 he entered his name on the Manchester Royal Infirmary

Manchester Royal Infirmary

The Manchester Royal Infirmary is a hospital in Manchester, England which was founded by Charles White in 1752 as a cottage hospital capable of caring for twelve patients. Manchester Royal Infirmary is part of a larger NHS Trust incorporating several hospitals called Central Manchester University...

register. The infirmary, in which he studied for the next six years as a surgeon

Surgeon

In medicine, a surgeon is a specialist in surgery. Surgery is a broad category of invasive medical treatment that involves the cutting of a body, whether human or animal, for a specific reason such as the removal of diseased tissue or to repair a tear or breakage...

, required that its students have a strong physique for the gruelling workload. The study of anatomy

Anatomy

Anatomy is a branch of biology and medicine that is the consideration of the structure of living things. It is a general term that includes human anatomy, animal anatomy , and plant anatomy...

, with dissection

Dissection

Dissection is usually the process of disassembling and observing something to determine its internal structure and as an aid to discerning the functions and relationships of its components....

classes, was a major part of study from the first term. Between 1885 and 1888 Thompson spent the majority of his time homeless

Homelessness

Homelessness describes the condition of people without a regular dwelling. People who are homeless are unable or unwilling to acquire and maintain regular, safe, and adequate housing, or lack "fixed, regular, and adequate night-time residence." The legal definition of "homeless" varies from country...

, living in the Docks area south of Whitechapel. Thompson tried a number of occupations. As well as a surgeon and a priest, Thompson tried being a soldier, but was dismissed for failing in drill. He also worked in a medical factory. This may have been where, apart from his years as a surgeon, Thompson procured the dissecting scalpel

Scalpel

A scalpel, or lancet, is a small and extremely sharp bladed instrument used for surgery, anatomical dissection, and various arts and crafts . Scalpels may be single-use disposable or re-usable. Re-usable scalpels can have attached, resharpenable blades or, more commonly, non-attached, replaceable...

which he claimed to have possessed when he wrote to the editor of the ‘Merry England’ in January 1889 of his need to swap to a razor for shaving.

Duke of Clarence

Philippe Jullian

Philippe Jullian was a French illustrator, art historian, biographer, aesthete, novelist and dandy.Jullian was born in Bordeaux in 1922...

published a biography of Clarence's father, Edward VII of the United Kingdom

Edward VII of the United Kingdom

Edward VII was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910...

. Jullian made a passing reference to rumours that Clarence might have been responsible for the murders. Though Jullian did not detail the dates or sources of the rumour, it is possible that the rumour derived indirectly from Dr. Thomas E. A. Stowell

Thomas E. A. Stowell

Thomas Edmund Alexander Stowell CBE, FRCS was a British physician.Stowell was educated at St Paul's School, followed by St Thomas' Hospital. From 1910, he took clinical training at St Thomas's Hospital, Grimsby and District Hospital, and the Royal Southern Hospital, Liverpool. He qualified as a...

. In 1960, Stowell told the rumour to writer Colin Wilson

Colin Wilson

Colin Henry Wilson is a prolific English writer who first came to prominence as a philosopher and novelist. Wilson has since written widely on true crime, mysticism and other topics. He prefers calling his philosophy new existentialism or phenomenological existentialism.- Early biography:Born and...

, who in turn told Harold Nicolson

Harold Nicolson

Sir Harold George Nicolson KCVO CMG was an English diplomat, author, diarist and politician. He was the husband of writer Vita Sackville-West, their unusual relationship being described in their son's book, Portrait of a Marriage.-Early life:Nicolson was born in Tehran, Persia, the younger son of...

, a biographer loosely credited as a source of "hitherto unpublished anecdotes" in Jullian's book. Nicolson could have communicated Stowell's theory to Jullian. The theory was brought to major public attention in 1970 when Stowell published an article in The Criminologist which revealed his suspicion that Clarence had committed the murders after being driven mad by syphilis

Syphilis

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum. The primary route of transmission is through sexual contact; however, it may also be transmitted from mother to fetus during pregnancy or at birth, resulting in congenital syphilis...

. The suggestion was widely dismissed as Albert Victor had strong alibis for the murders, and it is unlikely that he suffered from syphilis. Stowell later denied implying that Clarence was the Ripper but efforts to investigate his claims further were hampered as Stowell was an old man, and he died from natural causes just days after the publication of his article. The same week, Stowell's son reported that he had burned his father's papers, saying "I read just sufficient to make certain that there was nothing of importance."

Subsequently, conspiracy theorists

Conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory explains an event as being the result of an alleged plot by a covert group or organization or, more broadly, the idea that important political, social or economic events are the products of secret plots that are largely unknown to the general public.-Usage:The term "conspiracy...

, such as Stephen Knight in Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, have elaborated on the supposed involvement of Clarence in the murders. Rather than implicate Albert Victor directly, they claim that he secretly married and had a daughter with a Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

shop assistant, and that Queen Victoria, British Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Lord Salisbury, his Freemason friends, and the London Metropolitan Police conspired to murder anyone aware of Albert Victor's supposed child. Many facts contradict this theory and its originator, Joseph Gorman (also known as Joseph Sickert), later retracted the story and admitted to the press that it was a hoax. Variations of the theory involve the physician Sir William Gull, the artist Walter Sickert

Walter Sickert

Walter Richard Sickert , born in Munich, Germany, was a painter who was a member of the Camden Town Group in London. He was an important influence on distinctively British styles of avant-garde art in the 20th century....

, and the poet James Kenneth Stephen

James Kenneth Stephen

James Kenneth Stephen was an English poet, and tutor to Prince Albert Victor, eldest son of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales.-Early life:...

to greater or lesser degrees, and have been fictionalised in novels and films, such as Murder by Decree

Murder by Decree

Murder by Decree is an Anglo-Canadian thriller film involving Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson in the case of the serial murderer Jack the Ripper...

and From Hell

From Hell

From Hell is a comic book series by writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell, originally published from 1991 to 1996, speculating upon the identity and motives of Jack the Ripper. The title is taken from the first words of the "From Hell" letter, which some authorities believe was an authentic...

.

Sir John Williams

Sir John Williams was obstetrician to Queen Victoria'sVictoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India....

daughter Princess Beatrice

Princess Beatrice of the United Kingdom

The Princess Beatrice was a member of the British Royal Family. She was the fifth daughter and youngest child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Juan Carlos, King of Spain, is her great-grandson...

, and was accused of the Ripper crimes in a 2005 book, Uncle Jack, written by one of the surgeon's descendants, Tony Williams, and Humphrey Price. The authors claim that the victims knew the doctor personally, that they were killed and mutilated in an attempt to research the causes of infertility, and that a badly blunted surgical knife, which belonged to Williams, was the murder weapon. Jennifer Pegg demonstrated in two articles that much of the research in the book was flawed; for example, the version of the notebook entry used to argue that Williams had met Ripper victim Mary Ann Nichols had been altered for print and did not match the original document, and the line as found in the original document was in handwriting that did not match the rest of the notebook.

Further theories

Other named suspects include Swiss butcher Jacob Isenschmid, German hairdresser Charles Ludwig, apothecary and mental patient Oswald Puckridge (1838–1900), insane medical student John Sanders (1862–1901), Swedish tramp Nikaner Benelius, and even social reformer Thomas Barnardo, who claimed he had met one of the victims (Elizabeth StrideElizabeth Stride

Elizabeth "Long Liz" Stride is believed to be the third victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer called Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated prostitutes in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.She was nicknamed "Long Liz"...

) shortly before her murder. Isenschmid and Ludwig were exonerated after another murder was committed while they were in custody. There was no evidence against Barnardo, Benelius, Puckridge or Sanders. According to Donald McCormick

Donald McCormick

George Donald King McCormick was a British journalist and popular historian, who also wrote under the pseudonyms Richard Deacon and Lichade Digen....

, other suspects included mountebank L. Forbes Winslow

L. Forbes Winslow

Lyttelton Stewart Forbes Winslow MRCP was a British psychiatrist famous for his involvement in the Jack the Ripper and Georgina Weldon cases during the late Victorian era.-Career:...

, whose own suspect in the case was a religious maniac, G. Wentworth Bell Smith. Most recently, morgue assistant Robert Mann was added to the long list of suspects.

Named suspects who may be entirely fictional include "Dr Stanley", cult leader Nicolai Vasiliev, Norwegian sailor "Fogelma", and Russian needlewoman Olga Tchkersoff.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle DL was a Scottish physician and writer, most noted for his stories about the detective Sherlock Holmes, generally considered a milestone in the field of crime fiction, and for the adventures of Professor Challenger...

advanced theories involving a female murderer dubbed "Jill the Ripper". Supporters of this theory believe that the murderer worked, or posed, as a midwife, who could be seen with bloody clothes without attracting suspicion and would be more easily trusted by the victims than a man. One woman proposed as the Ripper was the convicted murderer Mary Pearcey

Mary Pearcey

Mary Pearcey was an English woman who was convicted of murdering her lover's wife, Mrs. Phoebe Hogg, and child, Phoebe, on 24 October 1890 and executed for the crime on 23 December of the same year...

, who killed her lover's wife and child in October 1890, though there is no indication she was ever a midwife. E. J. Wagner, in The Science of Sherlock Holmes, offers in passing another possible suspect, Constance Kent, who had served 20 years for the murder of her younger brother when she was sixteen.

Some Ripper authors, such as Patricia Cornwell

Patricia Cornwell

Patricia Cornwell is a contemporary American crime writer. She is widely known for writing a popular series of novels featuring the heroine Dr. Kay Scarpetta, a medical examiner.-Early life:...

, believe that the killer sent letters to the police and press. DNA analysis of the gum used on a postage stamp of one of these letters was "inconclusive" and "not forensically reliable". The available material has been handled many times and is therefore too contaminated to provide any meaningful results. Moreover, most authorities consider the letters hoaxes.

Several theorists suggest that "Jack the Ripper" was actually more than one killer. Stephen Knight argued that the murders were a conspiracy involving multiple miscreants, whereas others supposed each murder was committed by an unconnected individual acting independently.

The police believed the Ripper was a local Whitechapel resident. The Ripper's apparent ability to immediately disappear after the killings suggests an intimate knowledge of the Whitechapel neighbourhood, including its back alleys and hiding places. However, the population of Whitechapel was transient, impoverished and often used aliases. The lives of many of its residents were little recorded. The Ripper's true identity will almost certainly never be known.