Cathar

Encyclopedia

Catharism was a name given to a Christian religious sect with dualistic

and gnostic

elements that appeared in the Languedoc

region of France and other parts of Europe in the 11th century and flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries. Catharism had its roots in the Paulician

movement in Armenia

and the Bogomils

of Bulgaria

which took influences from the Paulicians. Though the term "Cathar" has been used for centuries to identify the movement, whether the movement identified itself with this name is debatable. In Cathar texts, the terms "Good Men" (Bons Hommes) or "Good Christians" are the common terms of self-identification.

. The dualist theology was the most prominent, however, and was based upon an asserted complete incompatibility of love and power. As matter was seen as a manifestation of power, it was believed to be incompatible with love.

The Cathari did not believe in one all-encompassing god, but in two, both equal and comparable in status. They held that the physical world was evil and created by Rex Mundi

(translated from Latin as "king of the world"), who encompassed all that was corporeal, chaotic and powerful; the second god, the one whom they worshipped, was entirely disincarnate: a being or principle of pure spirit and completely unsullied by the taint of matter. He was the god of love, order and peace.

According to some Cathars, the purpose of man's life on Earth was to transcend matter, perpetually renouncing anything connected with the principle of power and thereby attaining union with the principle of love. According to others, man's purpose was to reclaim or redeem matter, spiritualising and transforming it.

Regarding material creation as being intrinsically evil placed them at odds with the Catholic Church, which holds that God not only created matter but was born into the material world in Jesus Christ. The implication is that God, whose word had created the world in the beginning, was a usurper at best and the god of evil / Rex Mundi at worst. (Cf. the Demiurge

idea common to many Gnostics). Consequently the Cathars, considering matter as intrinsically evil, denied that Jesus could become incarnate and still be the son of God. Cathars vehemently repudiated the significance of the crucifixion

and the cross. To the Cathars, Rome's opulent and luxurious Church seemed a palpable embodiment and manifestation on Earth of Rex Mundi's sovereignty.

Faced with the rapid spread of the movement across the Languedoc region, the Church first sought peaceful attempts at conversion, undertaken by Dominicans

. These were not very successful and after the murder on 15 January 1208 of the papal legate Pierre de Castelnau

by an unknown person, presumed by Pope Innocent III

to have been a knight in the employ of Count Raymond of Toulouse, the Church called for a crusade. This was carried out by knights from northern France and Germany and was known as the Albigensian Crusade

.

The papal legate had involved himself in a dispute between the rivals Count of Baux and Count Raymond of Toulouse and it is possible that his assassination had little to do with Catharism. The anti-Cathar Albigensian Crusade, and the inquisition

which followed it, entirely eradicated the Cathars. The Albigensian Crusade had the effect of greatly weakening the semi-independent southern Principalities such as Toulouse

, whose Occitan language was playing an important role in Western Europe, and ultimately bringing them under direct control of the King of France.

and the Byzantine Empire

by way of trade route

s. The name of Bulgarians

(Bougres) was also applied to the Albigenses, and they maintained an association with the similar Christian movement of the Bogomils

("Friends of God") of Thrace

. "That there was a substantial transmission of ritual and ideas from Bogomilism to Catharism is beyond reasonable doubt." Their doctrines have numerous resemblances to those of the Bogomils and the earlier Paulicians

as well as the Manicheans and the Christian Gnostics of the first few centuries AD, although, as many scholars, most notably Mark Pegg

, have pointed out, it would be erroneous to extrapolate direct, historical connections based on theoretical similarities perceived by modern scholars. Much of our existing knowledge of the Cathars is derived from their opponents, the writings of the Cathars mostly having been destroyed because of the doctrinal threat perceived by the Papacy. For this reason it is likely, as with most heretical movements of the period, that we have only a partial view of their beliefs. Conclusions about Cathar ideology continue to be fiercely debated with commentators regularly accusing their opponents of speculation, distortion and bias. There are a few texts from the Cathars themselves which were preserved by their opponents (the Rituel Cathare de Lyon) which give a glimpse of the inner workings of their faith, but these still leave many questions unanswered. One large text which has survived, The Book of Two Principles (Liber de duobus principiis), elaborates the principles of dualistic theology from the point of view of some of the Albanenses

Cathars.

It is now generally agreed by most scholars that identifiable Catharism did not emerge until at least 1143, when the first confirmed report of a group espousing similar beliefs is reported being active at Cologne by the cleric Eberwin of Steinfeld. A landmark in the "institutional history" of the Cathars was the Council

, held in 1167 at Saint-Félix-Lauragais

, attended by many local figures and also by the Bogomil

papa Nicetas

, the Cathar bishop of (northern) France

and a leader of the Cathars of Lombardy

.

Although there are certainly similarities in theology and practice between Gnostic/dualist groups of Late Antiquity (such as the Marcionites

or Manichaeans

) and the Cathars, there was not a direct link between the two; Manichaeanism died out in the West by the 7th century. The Cathars were largely a homegrown, Western European/Latin Christian phenomenon, springing up in the Rhineland cities (particularly Cologne) in the mid-12th century, northern France around the same time, and particularly southern France—the Languedoc—and the northern Italian cities in the mid-late 12th century. In the Languedoc and northern Italy, the Cathars would enjoy their greatest popularity, surviving in the Languedoc, in much reduced form, up to around 1325 and in the Italian cities until the Inquisitions

of the 1260s–1300s finally rooted them out.

from the founders of Christianity, and saw Rome as having betrayed and corrupted the original purity of the message, particularly since Pope Sylvester I accepted the Donation of Constantine

(which at the time was believed to be genuine).

, Cathar sacred texts include The Gospel of the Secret Supper, or John's Interrogation and The Book of the Two Principles.

, of Manichaeism

and of the theology of the Bogomils

. This concept of the human condition within Catharism was most probably due to direct and indirect historical influences from these older Gnostic movements. According to the Cathars, the world had been created by a lesser deity, much like the figure known in classical Gnostic myth as the Demiurge

. This creative force was identified with Satan

. Most forms of classical Gnosticism had not made this explicit link between the Demiurge and Satan. Spirit, the vital essence of humanity, was thus trapped in a polluted world created by a usurper god and ruled by his corrupt minions.

was liberation from the realm of limitation and corruption identified with material existence. The path to liberation first required an awakening to the intrinsic corruption of the medieval "consensus reality", including its ecclesiastical, dogma

tic, and social structures. Once cognizant of the grim existential reality of human existence (the "prison" of matter

), the path to spiritual liberation became obvious: matter's enslaving bonds must be broken. This was a step-by-step process, accomplished in different measures by each individual. The Cathars accepted the idea of reincarnation

. Those who were unable to achieve liberation during their current mortal journey would return another time to continue the struggle for perfection. Thus, it should be understood that being reincarnated was neither inevitable nor desirable, and that it occurred because not all humans could break the enthralling chains of matter within a single lifetime.

(Perfects, Parfaits) and the Credentes

(Believers). The Perfecti formed the core of the movement, though the actual number of Perfecti in Cathar society was always relatively small, numbering perhaps a few thousand at any one time. Regardless of their number, they represented the perpetuating heart of the Cathar tradition, the "true Christian Church", as they styled themselves. (When discussing the tenets of Cathar faith it must be understood that the demands of extreme asceticism

fell only upon the Perfecti.)

An individual entered into the community of Perfecti through a ritual

known as the consolamentum, a rite that was both sacramental and sacerdotal in nature: sacramental in that it granted redemption and liberation from this world; sacerdotal in that those who had received this rite functioned in some ways as the Cathar clergy—though the idea of priesthood was explicitly rejected. The consolamentum was the baptism

of the Holy Spirit

, baptismal regeneration, absolution

, and ordination

all in one. The ritual consisted of the laying on of hands (and the transfer of the spirit) in a manner believed to have been passed down in unbroken succession from Jesus Christ. Upon reception of the consolamentum, the new Perfectus surrendered his or her worldly goods to the community, vested himself in a simple black or blue robe with cord belt, and sought to undertake a life dedicated to following the example of Christ

and his Apostles — an often peripatetic life devoted to purity, prayer, preaching and charitable work. Above all, the Perfecti were dedicated to enabling others to find the road that led from the dark land ruled by the dark lord, to the realm of light which they believed to be humankind's first source and ultimate end.

While the Perfecti pledged themselves to ascetic

lives of simplicity

, frugality and purity, Cathar credentes (believers) were not expected to adopt the same stringent lifestyle. They were, however, expected to refrain from eating meat

and dairy

products, from killing and from swearing oath

s. Catharism was above all a populist religion and the numbers of those who considered themselves "believers" in the late 12th century included a sizeable portion of the population of Languedoc, counting among them many noble families and courts. These individuals often drank, ate meat, and led relatively normal lives within medieval society—in contrast to the Perfecti, whom they honoured as exemplars. Though unable to embrace the life of chastity, the credentes looked toward an eventual time when this would be their calling and path.

Many credentes would also eventually receive the consolamentum as death drew near—performing the ritual of liberation at a moment when the heavy obligations of purity required of Perfecti would be temporally short. Some of those who received the sacrament of the consolamentum upon their death-beds may thereafter have shunned further food or drink in order to speed death. This has been termed the endura. It was claimed by Catharism's opponents that by such self-imposed starvation, the Cathars were committing suicide in order to escape this world. Other than at such moments of extremis, little evidence exists to suggest this was a common Cathar practice.

in the East. Some Cathari adhered to a concept of Jesus that might be called docetistic

, believing that Jesus had been a manifestation of spirit unbounded by the limitations of matter—a sort of divine spirit or feeling manifesting within human beings. Many embraced the Gospel of John

as their most sacred text, and many rejected the traditional view of the Old Testament

—proclaiming that the God of the Old Testament

was really the devil

, or creative demiurge. They proclaimed that there was a higher God—the True God—and Jesus was variously described as being that True God or his messenger. These are views similar to those of Marcion, though Marcion never identified the creative demiurge with Satan, nor said that he was (strictly speaking) evil, merely harsh and dictatorial.

The God found in the Old Testament had nothing to do with the God of Love known to Cathars. The Old Testament God had created the world as a prison

, and demanded from the "prisoners" fearful obedience and worship. The Cathari claimed that this god was in fact a blind usurper who under the most false pretexts, tormented and murdered those whom he called, all too possessively, "his children". The false god was, by the Cathari, called Rex Mundi, or The King of the World. This exegesis

upon the Old Testament was not unique to the Cathars: it echoes views found in earlier Gnostic movements and foreshadows later critical voices. The dogma

of the Trinity

and the sacrament of the Eucharist

, among others, were rejected as abominations. Belief in metempsychosis, or the transmigration of souls

, resulted in the rejection of Hell

and Purgatory

, which were and are dogmas of the Catholic faith. For the Cathars, this world was the only hell

—there was nothing to fear after death, save perhaps rebirth.

While this is the understanding of Cathar theology related by the Catholic Church, crucial to the study of the Cathars is their fundamental disagreement with the Christian interpretation of the Doctrine of "resurrection" (cryptically referred to in and ) as a doctrine of the physical raising of a dead body from the grave. In the book "Massacre at Montségur

" the Cathars are referred to as "Western Buddhists" because of their belief that the Doctrine of "resurrection" taught by Jesus was, in fact, similar to the Buddhist Doctrine of Rebirth (referred to as "reincarnation"). This challenge to the orthodox Christian interpretation of the "resurrection" reflected a conflict previously witnessed during the 2nd and 3rd centuries between Gnosticism and developing orthodox Christian theology.

Sexual intercourse and reproduction propagated the slavery of spirit to flesh, hence procreation was considered undesirable. Informal relationships were considered preferable to marriage among Cathar credentes. Perfecti were supposed to have observed complete celibacy, and eventual separation from a partner would be necessary for those who would become Perfecti. For the credentes however, sexual activity was not prohibited, but procreation was strongly discouraged, resulting in the charge by their opponents of sexual perversion. The common British insult "bugger

" is derived from "Bulgar", the notion that Cathars followed the "Bulgarian heresy

" whose teaching included sexual activities which skirted procreation.

Killing was abhorrent to the Cathars. Consequently, abstention from all animal food (sometimes exempting fish

) was enjoined of the Perfecti. The Perfecti apparently avoided eating anything considered to be a by-product of sexual reproduction — war and capital punishment

were also condemned, an abnormality in the medieval age. As a consequence of their rejection of oaths, Cathars also rejected marriage vows.

Cathar teachings, in theological intent and practical consequence, brought condemnation from Catholic authorities both religious and secular, as being inimical to the Catholic faith and of feudal social order.

In about 1225, during a lull in the Albigensian Crusade

, the bishopric of Razes was added. Bishops were supported by their two assistants, a filius maior and filius minor, typically the former would be the successor, further, these were assisted by deacons. The perfecti were the spiritual elite, highly respected by many of the local people, leading a life of austerity and charity. In the apostolic fashion they ministered to the people travelling in pairs.

sent a legate

to the Cathar district in order to arrest the progress of the Cathars. The few isolated successes of Bernard of Clairvaux

could not obscure the poor results of this mission, which clearly showed the power of the sect in the Languedoc at that period. The missions of Cardinal Peter of St. Chrysogonus to Toulouse and the Toulousain in 1178, and of Henry of Marcy

, cardinal-bishop of Albano, in 1180–81, obtained merely momentary successes. Henry's armed expedition, which took the stronghold at Lavaur

, did not extinguish the movement.

Decisions of Catholic Church councils—in particular, those of the Council of Tours

(1163) and of the Third Council of the Lateran

(1179)—had scarcely more effect upon the Cathars. When Pope Innocent III

came to power in 1198, he was resolved to deal with them.

At first Pope Innocent III tried pacific conversion, and sent a number of legates into the Cathar regions. They had to contend not only with the Cathars, the nobles who protected them, and the people who venerated them, but also with many of the bishop

s of the region, who resented the considerable authority the Pope

had conferred upon his legates. In 1204, Innocent III suspended a number of bishops in Occitania

; in 1205 he appointed a new and vigorous bishop of Toulouse, the former troubadour

Foulques

. In 1206 Diego of Osma and his canon, the future Saint Dominic

, began a programme of conversion in Languedoc; as part of this, Catholic-Cathar public debates were held at Verfeil, Servian, Pamiers

, Montréal

and elsewhere.

Saint Dominic

met and debated the Cathars in 1203 during his mission to the Languedoc. He concluded that only preachers who displayed real sanctity, humility and asceticism could win over convinced Cathar believers. The official Church as a rule did not possess these spiritual warrants. His conviction led eventually to the establishment of the Dominican Order

in 1216. The order was to live up to the terms of his famous rebuke, "Zeal must be met by zeal, humility by humility, false sanctity by real sanctity, preaching falsehood by preaching truth." However, even St. Dominic managed only a few converts among the Cathari.

was sent to meet the ruler of the area, Count Raymond VI of Toulouse

. Known for excommunicating noblemen who protected the Cathars, Castelnau excommunicated Raymond as an abettor

of heresy following an allegedly fierce argument during which Raymond supposedly threatened Castelnau with violence. Shortly thereafter, Castelnau was murdered as he returned to Rome, allegedly by a knight in the service of Count Raymond. His body was returned and laid to rest in the Abbey at Saint Gilles. As soon as he heard of the murder, the Pope ordered the legates to preach a crusade

against the Cathars and wrote a letter to Phillip Augustus, King of France, appealing for his intervention—or an intervention led by his son, Louis. This was not the first appeal but some have seen the murder of the legate as a turning point in papal policy—whereas it might be more accurate to see it as a fortuitous event in allowing the Pope to excite popular opinion and to renew his pleas for intervention in the south. The entirely biased chronicler of the crusade which was to follow, Peter de Vaux de Cernay, portrays the sequence of events in such a way as to make us believe that, having failed in his effort to peacefully demonstrate the errors of Catharism, the Pope then called a formal crusade, appointing a series of leaders to head the assault. The French King refused to lead the crusade himself, nor could he spare his son—despite his victory against John of England, there were still pressing issues with Flanders and the empire and the threat of an Angevin revival. Phillip did however sanction the participation of some of his more bellicose and ambitious—some might say dangerous—barons, notably Simon de Montfort

and Bouchard de Marly. There followed twenty years of war against the Cathars and their allies in the Languedoc: the Albigensian Crusade

.

This war pitted the nobles of the north of France against those of the south. The widespread northern enthusiasm for the Crusade was partially inspired by a papal decree permitting the confiscation of lands owned by Cathars and their supporters. This not only angered the lords of the south but also the French King, who was at least nominally the suzerain of the lords whose lands were now open to despoliation and seizure. Phillip Augustus wrote to Pope Innocent in strong terms to point this out—but the Pope did not change his policy—and many of those who went to the Midi were aware that the Pope had been equivocal over the siege of Zara and the seizure and looting of Constantinople. As the Languedoc was supposedly teeming with Cathars and Cathar sympathisers, this made the region a target for northern French noblemen looking to acquire new fiefs. The barons of the north headed south to do battle, their first target the lands of the Trencavel, powerful lords of Albi, Carcassonne and the Razes—but a family with few allies in the Midi. Little was thus done to form a regional coalition and the crusading army was able to take Carcassonne, the Trencavel capital by duplicitous methods, incarcerating Raymond Roger in his own citadel where he died, allegedly of natural causes; champions of the Occitan

cause from that day to this believe he was murdered. Simon de Montfort was granted the Trencavel lands by the Pope and did homage for them to the King of France, thus incurring the enmity of Peter of Aragon who had held aloof from the conflict, even acting as a mediator at the time of the siege of Carcassonne. The remainder of the first of the two Cathar wars now essentially focused on Simon's attempt to hold on to his fabulous gains through winters where he was faced, with only a small force of confederates operating from the main winter camp at Fanjeau, with the desertion of local lords who had sworn fealty to him out of necessity—and attempts to enlarge his new found domains in the summer when his forces were greatly augmented by reinforcements from northern France, Germany and elsewhere. Summer campaigns saw him not only retake, sometimes with brutal reprisals, what he had lost in the 'close' season, but also seek to widen his sphere of operation—and we see him in action in the Aveyron at St. Antonin and on the banks of the Rhone at Beaucaire. Simon's greatest triumph was the victory against superior numbers at the Battle of Muret

—a battle which saw not only the defeat of Raymond of Toulouse and his Occitan allies—but also the death of Peter of Aragon—and the effective end of the ambitions of the house of Aragon/Barcelona in the Languedoc. This was in the medium and longer term of much greater significance to the royal house of France than it was to De Montfort—and with the battle of Bouvines was to secure the position of Philip Augustus vis a vis England and the Empire. The Battle of Muret

was a massive step in the creation of the unified French kingdom and the country we know today—although Edward III, the Black Prince and Henry V would threaten later to shake these foundations.

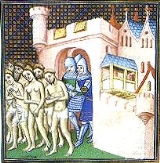

of Cîteaux. In the first significant engagement of the war, the town of Béziers

was besieged

on 22 July 1209. The Catholic inhabitants of the city were granted the freedom to leave unharmed, but many refused and opted to stay and fight alongside the Cathars.

The Cathars spent much of 1209 fending off the crusaders. The leader of the crusaders, Simon de Montfort

, resorted to primitive psychological warfare. He ordered his troops to gouge out the eyes of 100 prisoners, cut off their noses and lips, then send them back to the towers led by a prisoner with one remaining eye. This only served to harden the resolve of the Cathars.

The Béziers army attempted a sortie

but was quickly defeated, then pursued by the crusaders back through the gates and into the city. Arnaud, the Cistercian abbot-commander, is supposed to have been asked how to tell Cathars from Catholics. His reply, recalled by Caesar of Heisterbach

, a fellow Cistercian, thirty years later was ""—"Kill them all, the Lord will recognise His own." The doors of the church of St Mary Magdalene were broken down and the refugees dragged out and slaughtered. Reportedly, 7,000 people died there. Elsewhere in the town many more thousands were mutilated and killed. Prisoners were blinded, dragged behind horses, and used for target practice. What remained of the city was razed by fire. Arnaud wrote to Pope Innocent III

, "Today your Holiness, twenty thousand heretics were put to the sword, regardless of rank, age, or sex." The permanent population of Béziers at that time was then probably no more than 5,000, but local refugees seeking shelter within the city walls could conceivably have increased the number to 20,000.

After the success of his siege of Carcassonne

, which followed the massacre at Béziers, Simon de Montfort

was designated as leader of the Crusader army. Prominent opponents of the Crusaders were Raymond-Roger de Trencavel

, viscount of Carcassonne, and his feudal overlord Peter II

, the king of Aragon

, who held fiefdoms and had a number of vassals in the region. Peter died fighting against the crusade on 12 September 1213 at the Battle of Muret

.

, by which the king of France dispossessed the house of Toulouse of the greater part of its fiefs

, and that of the Trencavels (Viscount

s of Béziers and Carcassonne) of the whole of their fiefs. The independence of the princes of the Languedoc was at an end. But in spite of the wholesale massacre of Cathars during the war, Catharism was not yet extinguished.

In 1215, the bishops of the Catholic Church met at the Fourth Council of the Lateran

under Pope Innocent III

. One of the key goals of the council was to combat the heresy of the Cathars.

The Inquisition

was established in 1229 to uproot the remaining Cathars. Operating in the south at Toulouse, Albi, Carcassonne

and other towns during the whole of the 13th century, and a great part of the 14th, it finally succeeded in extirpating the movement. Cathars who refused to recant were hanged, or burnt at the stake.

From May 1243 to March 1244, the Cathar fortress of Montségur

was besieged by the troops of the seneschal

of Carcassonne and the archbishop of Narbonne. On 16 March 1244, a large and symbolically important massacre took place, where over 200 Cathar Perfect

s were burnt in an enormous fire at the prat dels cremats near the foot of the castle. Moreover, the Church decreed lesser chastisements against laymen suspected of sympathy with Cathars, at the 1235 Council of Narbonne

.

A popular though as yet unsubstantiated theory holds that a small party of Cathar Perfects escaped from the fortress before the massacre at prat dels cremats. It is widely held in the Cathar region to this day that the escapees took with them le tresor cathar. What this treasure consisted of has been a matter of considerable speculation: claims range from sacred Gnostic texts to the Cathars' accumulated wealth.

A popular though as yet unsubstantiated theory holds that a small party of Cathar Perfects escaped from the fortress before the massacre at prat dels cremats. It is widely held in the Cathar region to this day that the escapees took with them le tresor cathar. What this treasure consisted of has been a matter of considerable speculation: claims range from sacred Gnostic texts to the Cathars' accumulated wealth.

Hunted by the Inquisition and deserted by the nobles of their districts, the Cathars became more and more scattered fugitives: meeting surreptitiously in forests and mountain wilds. Later insurrections broke out under the leadership of Bernard of Foix, Aimery of Narbonne

and Bernard Délicieux (a Franciscan friar later prosecuted for his adherence to another heretical movement, that of the Spiritual Franciscans) at the beginning of the 14th century. But by this time the Inquisition had grown very powerful. Consequently, many were summoned to appear before it. Precise indications of this are found in the registers of the Inquisitors, Bernard of Caux, Jean de St Pierre, Geoffroy d'Ablis, and others. The parfaits only rarely recanted, and hundreds were burnt. Repentant lay believers were punished, but their lives were spared as long as they did not relapse. Having recanted, they were obliged to sew yellow crosses onto their outdoor clothing and to live apart from other Catholics, at least for a while.

, was executed in 1321.

Other movements, such as the Waldensians

and the pantheistic Brethren of the Free Spirit

, which suffered persecution in the same area survived in remote areas and in small numbers into the 14th and 15th centuries. Some Waldensian ideas were absorbed into early Protestant sects, such as the Hussites, Lollards, and the Moravian Church (Herrnhuters of Germany

). It is possible that Cathar ideas were too.

Any use of the term "Cathar" to refer to people after the suppression of Catharism in the 14th century is a cultural or ancestral reference, and has no religious implication. Nevertheless, interest in the Cathars, their history, legacy and beliefs continues.

The publication of the book Crusade against the Grail by the young German Otto Rahn

in the 1930s rekindled interest in the connection between the Cathars and the Holy Grail

. Rahn was convinced that the 13th century work Parzival

by Wolfram von Eschenbach

was a veiled account of the Cathars. His research attracted the attention of the Nazi government and in particular of Heinrich Himmler

, who made him archaeologist in the SS. Also, the Cathars have been depicted in popular books such as The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail

and Labryinth.

The term Pays Cathare, French meaning "Cathar Country" is used to highlight the Cathar heritage and history of the region where Catharism was traditionally strongest. This area is centred around fortresses such as Montségur

The term Pays Cathare, French meaning "Cathar Country" is used to highlight the Cathar heritage and history of the region where Catharism was traditionally strongest. This area is centred around fortresses such as Montségur

and Carcassonne

; also the French département of the Aude

uses the title Pays Cathare in tourist brochures. These areas have ruins from the wars against the Cathars which are still visible today.

Some criticise the promotion of the identity of Pays Cathare as an exaggeration for tourist

purposes. Actually, most of the promoted Cathar castles

were not built by Cathars but by local lords and later many of them were rebuilt and extended for strategic purposes. Good examples of these are the magnificent castles of Queribus and Peyrepetuse which are both perched on the side of precipitous drops on the last folds of the Corbieres mountains. They were for several hundred years frontier fortresses belonging to the French crown and most of what you will see there today in their well preserved remains dates from a post-Cathar era. The Cathars sought refuge at these sites. Many consider the County of Foix

to be the actual historical centre of Catharism.

.

Dualism

Dualism denotes a state of two parts. The term 'dualism' was originally coined to denote co-eternal binary opposition, a meaning that is preserved in metaphysical and philosophical duality discourse but has been diluted in general or common usages. Dualism can refer to moral dualism, Dualism (from...

and gnostic

Gnosticism

Gnosticism is a scholarly term for a set of religious beliefs and spiritual practices common to early Christianity, Hellenistic Judaism, Greco-Roman mystery religions, Zoroastrianism , and Neoplatonism.A common characteristic of some of these groups was the teaching that the realisation of Gnosis...

elements that appeared in the Languedoc

Languedoc

Languedoc is a former province of France, now continued in the modern-day régions of Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrénées in the south of France, and whose capital city was Toulouse, now in Midi-Pyrénées. It had an area of approximately 42,700 km² .-Geographical Extent:The traditional...

region of France and other parts of Europe in the 11th century and flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries. Catharism had its roots in the Paulician

Paulicianism

Paulicians were a Christian Adoptionist sect and militarized revolt movement, also accused by medieval sources as Gnostic and quasi Manichaean Christian. They flourished between 650 and 872 in Armenia and the Eastern Themes of the Byzantine Empire...

movement in Armenia

Armenia

Armenia , officially the Republic of Armenia , is a landlocked mountainous country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia...

and the Bogomils

Bogomilism

Bogomilism was a Gnostic religiopolitical sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Petar I in the 10th century...

of Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

which took influences from the Paulicians. Though the term "Cathar" has been used for centuries to identify the movement, whether the movement identified itself with this name is debatable. In Cathar texts, the terms "Good Men" (Bons Hommes) or "Good Christians" are the common terms of self-identification.

Introduction

Like many medieval movements, there were various schools of thought and practice amongst the Cathari; some were dualistic (believing in a god of Good and a god of Evil), others Gnostic, some closer to orthodoxy while abstaining from an acceptance of CatholicismCatholicism

Catholicism is a broad term for the body of the Catholic faith, its theologies and doctrines, its liturgical, ethical, spiritual, and behavioral characteristics, as well as a religious people as a whole....

. The dualist theology was the most prominent, however, and was based upon an asserted complete incompatibility of love and power. As matter was seen as a manifestation of power, it was believed to be incompatible with love.

The Cathari did not believe in one all-encompassing god, but in two, both equal and comparable in status. They held that the physical world was evil and created by Rex Mundi

Rex Mundi

Rex Mundi is Latin for King of the World.Rex Mundi may also refer to:* Rex Mundi , a comic book series* Rex Mundi , a fictional character in Malibu Comics' Ultraverse imprint...

(translated from Latin as "king of the world"), who encompassed all that was corporeal, chaotic and powerful; the second god, the one whom they worshipped, was entirely disincarnate: a being or principle of pure spirit and completely unsullied by the taint of matter. He was the god of love, order and peace.

According to some Cathars, the purpose of man's life on Earth was to transcend matter, perpetually renouncing anything connected with the principle of power and thereby attaining union with the principle of love. According to others, man's purpose was to reclaim or redeem matter, spiritualising and transforming it.

Regarding material creation as being intrinsically evil placed them at odds with the Catholic Church, which holds that God not only created matter but was born into the material world in Jesus Christ. The implication is that God, whose word had created the world in the beginning, was a usurper at best and the god of evil / Rex Mundi at worst. (Cf. the Demiurge

Demiurge

The demiurge is a concept from the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy for an artisan-like figure responsible for the fashioning and maintenance of the physical universe. The term was subsequently adopted by the Gnostics...

idea common to many Gnostics). Consequently the Cathars, considering matter as intrinsically evil, denied that Jesus could become incarnate and still be the son of God. Cathars vehemently repudiated the significance of the crucifixion

Crucifixion

Crucifixion is an ancient method of painful execution in which the condemned person is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross and left to hang until dead...

and the cross. To the Cathars, Rome's opulent and luxurious Church seemed a palpable embodiment and manifestation on Earth of Rex Mundi's sovereignty.

Faced with the rapid spread of the movement across the Languedoc region, the Church first sought peaceful attempts at conversion, undertaken by Dominicans

Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

. These were not very successful and after the murder on 15 January 1208 of the papal legate Pierre de Castelnau

Pierre de Castelnau

Pierre de Castelnau , French ecclesiastic, was born in the diocese of Montpellier.In 1199 he was archdeacon of Maguelonne, and was appointed by Pope Innocent III as one of the legates for the suppression of the Cathar heresy in Languedoc.In 1202, when a monk in the Cistercian abbey of Fontfroide,...

by an unknown person, presumed by Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III was Pope from 8 January 1198 until his death. His birth name was Lotario dei Conti di Segni, sometimes anglicised to Lothar of Segni....

to have been a knight in the employ of Count Raymond of Toulouse, the Church called for a crusade. This was carried out by knights from northern France and Germany and was known as the Albigensian Crusade

Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade or Cathar Crusade was a 20-year military campaign initiated by the Catholic Church to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc...

.

The papal legate had involved himself in a dispute between the rivals Count of Baux and Count Raymond of Toulouse and it is possible that his assassination had little to do with Catharism. The anti-Cathar Albigensian Crusade, and the inquisition

Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

which followed it, entirely eradicated the Cathars. The Albigensian Crusade had the effect of greatly weakening the semi-independent southern Principalities such as Toulouse

Toulouse

Toulouse is a city in the Haute-Garonne department in southwestern FranceIt lies on the banks of the River Garonne, 590 km away from Paris and half-way between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea...

, whose Occitan language was playing an important role in Western Europe, and ultimately bringing them under direct control of the King of France.

Origins

The Cathars' beliefs are thought to have come originally from Eastern EuropeEastern Europe

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of Europe. The term has widely disparate geopolitical, geographical, cultural and socioeconomic readings, which makes it highly context-dependent and even volatile, and there are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region"...

and the Byzantine Empire

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the Roman Empire or Romania to its inhabitants and neighbours, the Empire was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State...

by way of trade route

Trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a single trade route contains long distance arteries which may further be connected to several smaller networks of commercial...

s. The name of Bulgarians

Bulgarians

The Bulgarians are a South Slavic nation and ethnic group native to Bulgaria and neighbouring regions. Emigration has resulted in immigrant communities in a number of other countries.-History and ethnogenesis:...

(Bougres) was also applied to the Albigenses, and they maintained an association with the similar Christian movement of the Bogomils

Bogomilism

Bogomilism was a Gnostic religiopolitical sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Petar I in the 10th century...

("Friends of God") of Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

. "That there was a substantial transmission of ritual and ideas from Bogomilism to Catharism is beyond reasonable doubt." Their doctrines have numerous resemblances to those of the Bogomils and the earlier Paulicians

Paulicianism

Paulicians were a Christian Adoptionist sect and militarized revolt movement, also accused by medieval sources as Gnostic and quasi Manichaean Christian. They flourished between 650 and 872 in Armenia and the Eastern Themes of the Byzantine Empire...

as well as the Manicheans and the Christian Gnostics of the first few centuries AD, although, as many scholars, most notably Mark Pegg

Mark Gregory Pegg

Mark Gregory Pegg is an Australian professor of medieval history, currently teaching in the United States at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. He specializes in scholarship of the Albigensian Crusade and the Inquisition, the history of heresy, and the history of holiness...

, have pointed out, it would be erroneous to extrapolate direct, historical connections based on theoretical similarities perceived by modern scholars. Much of our existing knowledge of the Cathars is derived from their opponents, the writings of the Cathars mostly having been destroyed because of the doctrinal threat perceived by the Papacy. For this reason it is likely, as with most heretical movements of the period, that we have only a partial view of their beliefs. Conclusions about Cathar ideology continue to be fiercely debated with commentators regularly accusing their opponents of speculation, distortion and bias. There are a few texts from the Cathars themselves which were preserved by their opponents (the Rituel Cathare de Lyon) which give a glimpse of the inner workings of their faith, but these still leave many questions unanswered. One large text which has survived, The Book of Two Principles (Liber de duobus principiis), elaborates the principles of dualistic theology from the point of view of some of the Albanenses

Albanenses

The Albanenses were a group of Manichaeans who lived in Albania, probably about the eighth century.Little is known about them, except that they were one of the numerous sects through which the original Manichaeism continued to flourish. The Albanenses were a group of Manichaeans who lived in...

Cathars.

It is now generally agreed by most scholars that identifiable Catharism did not emerge until at least 1143, when the first confirmed report of a group espousing similar beliefs is reported being active at Cologne by the cleric Eberwin of Steinfeld. A landmark in the "institutional history" of the Cathars was the Council

Council of Saint-Félix

The Council of Saint-Félix, a landmark in the organisation of the Cathars, was held at Saint-Felix-de-Caraman, now called Saint-Félix-Lauragais, in 1167...

, held in 1167 at Saint-Félix-Lauragais

Saint-Félix-Lauragais

Saint-Félix-Lauragais is a commune in the Haute-Garonne department in southwestern France.-History:The village was previously called Saint-Félix-de-Caraman or Carmaing...

, attended by many local figures and also by the Bogomil

Bogomilism

Bogomilism was a Gnostic religiopolitical sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Petar I in the 10th century...

papa Nicetas

Nicetas, Bogomil bishop

Nicetas, known only from Latin sources who call him papa Nicetas, is said to have been the Bogomil bishop of Constantinople. In the 1160s he went to Lombardy...

, the Cathar bishop of (northern) France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and a leader of the Cathars of Lombardy

Lombardy

Lombardy is one of the 20 regions of Italy. The capital is Milan. One-sixth of Italy's population lives in Lombardy and about one fifth of Italy's GDP is produced in this region, making it the most populous and richest region in the country and one of the richest in the whole of Europe...

.

Although there are certainly similarities in theology and practice between Gnostic/dualist groups of Late Antiquity (such as the Marcionites

Marcionism

Marcionism was an Early Christian dualist belief system that originated in the teachings of Marcion of Sinope at Rome around the year 144; see also Christianity in the 2nd century....

or Manichaeans

Manichaeism

Manichaeism in Modern Persian Āyin e Māni; ) was one of the major Iranian Gnostic religions, originating in Sassanid Persia.Although most of the original writings of the founding prophet Mani have been lost, numerous translations and fragmentary texts have survived...

) and the Cathars, there was not a direct link between the two; Manichaeanism died out in the West by the 7th century. The Cathars were largely a homegrown, Western European/Latin Christian phenomenon, springing up in the Rhineland cities (particularly Cologne) in the mid-12th century, northern France around the same time, and particularly southern France—the Languedoc—and the northern Italian cities in the mid-late 12th century. In the Languedoc and northern Italy, the Cathars would enjoy their greatest popularity, surviving in the Languedoc, in much reduced form, up to around 1325 and in the Italian cities until the Inquisitions

Medieval Inquisition

The Medieval Inquisition is a series of Inquisitions from around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition and later the Papal Inquisition...

of the 1260s–1300s finally rooted them out.

General beliefs

Cathars, in general, formed an anti-sacerdotal party in opposition to the Catholic Church, protesting against what they perceived to be the moral, spiritual and political corruption of the Church. They claimed an Apostolic successionApostolic Succession

Apostolic succession is a doctrine, held by some Christian denominations, which asserts that the chosen successors of the Twelve Apostles, from the first century to the present day, have inherited the spiritual, ecclesiastical and sacramental authority, power, and responsibility that were...

from the founders of Christianity, and saw Rome as having betrayed and corrupted the original purity of the message, particularly since Pope Sylvester I accepted the Donation of Constantine

Donation of Constantine

The Donation of Constantine is a forged Roman imperial decree by which the emperor Constantine I supposedly transferred authority over Rome and the western part of the Roman Empire to the pope. During the Middle Ages, the document was often cited in support of the Roman Church's claims to...

(which at the time was believed to be genuine).

Sacred texts

Besides the New TestamentNew Testament

The New Testament is the second major division of the Christian biblical canon, the first such division being the much longer Old Testament....

, Cathar sacred texts include The Gospel of the Secret Supper, or John's Interrogation and The Book of the Two Principles.

Human condition

The Cathars believed there existed within mankind a spark of divine light. This light, or spirit, had fallen into captivity within a realm of corruption identified with the physical body and world. This was a distinct feature of classical GnosticismGnosticism

Gnosticism is a scholarly term for a set of religious beliefs and spiritual practices common to early Christianity, Hellenistic Judaism, Greco-Roman mystery religions, Zoroastrianism , and Neoplatonism.A common characteristic of some of these groups was the teaching that the realisation of Gnosis...

, of Manichaeism

Manichaeism

Manichaeism in Modern Persian Āyin e Māni; ) was one of the major Iranian Gnostic religions, originating in Sassanid Persia.Although most of the original writings of the founding prophet Mani have been lost, numerous translations and fragmentary texts have survived...

and of the theology of the Bogomils

Bogomilism

Bogomilism was a Gnostic religiopolitical sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Petar I in the 10th century...

. This concept of the human condition within Catharism was most probably due to direct and indirect historical influences from these older Gnostic movements. According to the Cathars, the world had been created by a lesser deity, much like the figure known in classical Gnostic myth as the Demiurge

Demiurge

The demiurge is a concept from the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy for an artisan-like figure responsible for the fashioning and maintenance of the physical universe. The term was subsequently adopted by the Gnostics...

. This creative force was identified with Satan

Satan

Satan , "the opposer", is the title of various entities, both human and divine, who challenge the faith of humans in the Hebrew Bible...

. Most forms of classical Gnosticism had not made this explicit link between the Demiurge and Satan. Spirit, the vital essence of humanity, was thus trapped in a polluted world created by a usurper god and ruled by his corrupt minions.

Eschatology

The goal of Cathar eschatologyEschatology

Eschatology is a part of theology, philosophy, and futurology concerned with what are believed to be the final events in history, or the ultimate destiny of humanity, commonly referred to as the end of the world or the World to Come...

was liberation from the realm of limitation and corruption identified with material existence. The path to liberation first required an awakening to the intrinsic corruption of the medieval "consensus reality", including its ecclesiastical, dogma

Dogma

Dogma is the established belief or doctrine held by a religion, or a particular group or organization. It is authoritative and not to be disputed, doubted, or diverged from, by the practitioners or believers...

tic, and social structures. Once cognizant of the grim existential reality of human existence (the "prison" of matter

Matter

Matter is a general term for the substance of which all physical objects consist. Typically, matter includes atoms and other particles which have mass. A common way of defining matter is as anything that has mass and occupies volume...

), the path to spiritual liberation became obvious: matter's enslaving bonds must be broken. This was a step-by-step process, accomplished in different measures by each individual. The Cathars accepted the idea of reincarnation

Reincarnation

Reincarnation best describes the concept where the soul or spirit, after the death of the body, is believed to return to live in a new human body, or, in some traditions, either as a human being, animal or plant...

. Those who were unable to achieve liberation during their current mortal journey would return another time to continue the struggle for perfection. Thus, it should be understood that being reincarnated was neither inevitable nor desirable, and that it occurred because not all humans could break the enthralling chains of matter within a single lifetime.

Consolamentum

Cathar society was divided into two general categories, the PerfectiCathar Perfect

Perfect was the name given to a monk of the medieval French Christian religious movement commonly referred to as the Cathars. The term reflects that such a person was seen by the Catholic Church as the "perfect heretic"...

(Perfects, Parfaits) and the Credentes

Credentes

Credentes or Believers, were the ordinary followers of what became known as the Cathar or Albigensian movement, a Christian sect which flourished in western Europe during the 11th, 12th and 13th Centuries. Credentes constituted up the main part of the Cathar community in the region...

(Believers). The Perfecti formed the core of the movement, though the actual number of Perfecti in Cathar society was always relatively small, numbering perhaps a few thousand at any one time. Regardless of their number, they represented the perpetuating heart of the Cathar tradition, the "true Christian Church", as they styled themselves. (When discussing the tenets of Cathar faith it must be understood that the demands of extreme asceticism

Asceticism

Asceticism describes a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from various sorts of worldly pleasures often with the aim of pursuing religious and spiritual goals...

fell only upon the Perfecti.)

An individual entered into the community of Perfecti through a ritual

Ritual

A ritual is a set of actions, performed mainly for their symbolic value. It may be prescribed by a religion or by the traditions of a community. The term usually excludes actions which are arbitrarily chosen by the performers....

known as the consolamentum, a rite that was both sacramental and sacerdotal in nature: sacramental in that it granted redemption and liberation from this world; sacerdotal in that those who had received this rite functioned in some ways as the Cathar clergy—though the idea of priesthood was explicitly rejected. The consolamentum was the baptism

Baptism

In Christianity, baptism is for the majority the rite of admission , almost invariably with the use of water, into the Christian Church generally and also membership of a particular church tradition...

of the Holy Spirit

Holy Spirit

Holy Spirit is a term introduced in English translations of the Hebrew Bible, but understood differently in the main Abrahamic religions.While the general concept of a "Spirit" that permeates the cosmos has been used in various religions Holy Spirit is a term introduced in English translations of...

, baptismal regeneration, absolution

Absolution

Absolution is a traditional theological term for the forgiveness experienced in the Sacrament of Reconciliation. This concept is found in the Roman Catholic Church, as well as the Eastern Orthodox churches, the Anglican churches, and most Lutheran churches....

, and ordination

Ordination

In general religious use, ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart as clergy to perform various religious rites and ceremonies. The process and ceremonies of ordination itself varies by religion and denomination. One who is in preparation for, or who is...

all in one. The ritual consisted of the laying on of hands (and the transfer of the spirit) in a manner believed to have been passed down in unbroken succession from Jesus Christ. Upon reception of the consolamentum, the new Perfectus surrendered his or her worldly goods to the community, vested himself in a simple black or blue robe with cord belt, and sought to undertake a life dedicated to following the example of Christ

Christ

Christ is the English term for the Greek meaning "the anointed one". It is a translation of the Hebrew , usually transliterated into English as Messiah or Mashiach...

and his Apostles — an often peripatetic life devoted to purity, prayer, preaching and charitable work. Above all, the Perfecti were dedicated to enabling others to find the road that led from the dark land ruled by the dark lord, to the realm of light which they believed to be humankind's first source and ultimate end.

While the Perfecti pledged themselves to ascetic

Asceticism

Asceticism describes a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from various sorts of worldly pleasures often with the aim of pursuing religious and spiritual goals...

lives of simplicity

Simplicity

Simplicity is the state or quality of being simple. It usually relates to the burden which a thing puts on someone trying to explain or understand it. Something which is easy to understand or explain is simple, in contrast to something complicated...

, frugality and purity, Cathar credentes (believers) were not expected to adopt the same stringent lifestyle. They were, however, expected to refrain from eating meat

Meat

Meat is animal flesh that is used as food. Most often, this means the skeletal muscle and associated fat and other tissues, but it may also describe other edible tissues such as organs and offal...

and dairy

Dairy

A dairy is a business enterprise established for the harvesting of animal milk—mostly from cows or goats, but also from buffalo, sheep, horses or camels —for human consumption. A dairy is typically located on a dedicated dairy farm or section of a multi-purpose farm that is concerned...

products, from killing and from swearing oath

Oath

An oath is either a statement of fact or a promise calling upon something or someone that the oath maker considers sacred, usually God, as a witness to the binding nature of the promise or the truth of the statement of fact. To swear is to take an oath, to make a solemn vow...

s. Catharism was above all a populist religion and the numbers of those who considered themselves "believers" in the late 12th century included a sizeable portion of the population of Languedoc, counting among them many noble families and courts. These individuals often drank, ate meat, and led relatively normal lives within medieval society—in contrast to the Perfecti, whom they honoured as exemplars. Though unable to embrace the life of chastity, the credentes looked toward an eventual time when this would be their calling and path.

Many credentes would also eventually receive the consolamentum as death drew near—performing the ritual of liberation at a moment when the heavy obligations of purity required of Perfecti would be temporally short. Some of those who received the sacrament of the consolamentum upon their death-beds may thereafter have shunned further food or drink in order to speed death. This has been termed the endura. It was claimed by Catharism's opponents that by such self-imposed starvation, the Cathars were committing suicide in order to escape this world. Other than at such moments of extremis, little evidence exists to suggest this was a common Cathar practice.

Theology

The Catharist concept of Jesus resembled modalistic monarchianism (Sabellianism) in the West and adoptionismAdoptionism

Adoptionism, sometimes called dynamic monarchianism, is a minority Christian belief that Jesus was adopted as God's son at his baptism...

in the East. Some Cathari adhered to a concept of Jesus that might be called docetistic

Docetism

In Christianity, docetism is the belief that Jesus' physical body was an illusion, as was his crucifixion; that is, Jesus only seemed to have a physical body and to physically die, but in reality he was incorporeal, a pure spirit, and hence could not physically die...

, believing that Jesus had been a manifestation of spirit unbounded by the limitations of matter—a sort of divine spirit or feeling manifesting within human beings. Many embraced the Gospel of John

Gospel of John

The Gospel According to John , commonly referred to as the Gospel of John or simply John, and often referred to in New Testament scholarship as the Fourth Gospel, is an account of the public ministry of Jesus...

as their most sacred text, and many rejected the traditional view of the Old Testament

Old Testament

The Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

—proclaiming that the God of the Old Testament

Old Testament

The Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

was really the devil

Devil

The Devil is believed in many religions and cultures to be a powerful, supernatural entity that is the personification of evil and the enemy of God and humankind. The nature of the role varies greatly...

, or creative demiurge. They proclaimed that there was a higher God—the True God—and Jesus was variously described as being that True God or his messenger. These are views similar to those of Marcion, though Marcion never identified the creative demiurge with Satan, nor said that he was (strictly speaking) evil, merely harsh and dictatorial.

The God found in the Old Testament had nothing to do with the God of Love known to Cathars. The Old Testament God had created the world as a prison

Prison

A prison is a place in which people are physically confined and, usually, deprived of a range of personal freedoms. Imprisonment or incarceration is a legal penalty that may be imposed by the state for the commission of a crime...

, and demanded from the "prisoners" fearful obedience and worship. The Cathari claimed that this god was in fact a blind usurper who under the most false pretexts, tormented and murdered those whom he called, all too possessively, "his children". The false god was, by the Cathari, called Rex Mundi, or The King of the World. This exegesis

Exegesis

Exegesis is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text, especially a religious text. Traditionally the term was used primarily for exegesis of the Bible; however, in contemporary usage it has broadened to mean a critical explanation of any text, and the term "Biblical exegesis" is used...

upon the Old Testament was not unique to the Cathars: it echoes views found in earlier Gnostic movements and foreshadows later critical voices. The dogma

Dogma

Dogma is the established belief or doctrine held by a religion, or a particular group or organization. It is authoritative and not to be disputed, doubted, or diverged from, by the practitioners or believers...

of the Trinity

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity defines God as three divine persons : the Father, the Son , and the Holy Spirit. The three persons are distinct yet coexist in unity, and are co-equal, co-eternal and consubstantial . Put another way, the three persons of the Trinity are of one being...

and the sacrament of the Eucharist

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

, among others, were rejected as abominations. Belief in metempsychosis, or the transmigration of souls

Reincarnation

Reincarnation best describes the concept where the soul or spirit, after the death of the body, is believed to return to live in a new human body, or, in some traditions, either as a human being, animal or plant...

, resulted in the rejection of Hell

Hell

In many religious traditions, a hell is a place of suffering and punishment in the afterlife. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hells as endless. Religions with a cyclic history often depict a hell as an intermediary period between incarnations...

and Purgatory

Purgatory

Purgatory is the condition or process of purification or temporary punishment in which, it is believed, the souls of those who die in a state of grace are made ready for Heaven...

, which were and are dogmas of the Catholic faith. For the Cathars, this world was the only hell

Hell

In many religious traditions, a hell is a place of suffering and punishment in the afterlife. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hells as endless. Religions with a cyclic history often depict a hell as an intermediary period between incarnations...

—there was nothing to fear after death, save perhaps rebirth.

While this is the understanding of Cathar theology related by the Catholic Church, crucial to the study of the Cathars is their fundamental disagreement with the Christian interpretation of the Doctrine of "resurrection" (cryptically referred to in and ) as a doctrine of the physical raising of a dead body from the grave. In the book "Massacre at Montségur

Montségur

The Château de Montségur is a former fortress near Montségur, a commune in the Ariège department in southwestern France. Its ruins are the site of a razed stronghold of the Cathars. The present fortress on the site, though described as one of the "Cathar castles," is actually of a later period...

" the Cathars are referred to as "Western Buddhists" because of their belief that the Doctrine of "resurrection" taught by Jesus was, in fact, similar to the Buddhist Doctrine of Rebirth (referred to as "reincarnation"). This challenge to the orthodox Christian interpretation of the "resurrection" reflected a conflict previously witnessed during the 2nd and 3rd centuries between Gnosticism and developing orthodox Christian theology.

Social relationships

From the theological underpinnings of the Cathar faith there came practical injunctions that were considered destabilising to the morals of medieval society. For instance, Cathars rejected the giving of oaths as wrongful; an oath served to place one under the domination of the Demiurge and the world. To reject oaths in this manner was seen as anarchic in a society where illiteracy was widespread and almost all business transactions and pledges of allegiance were based on the giving of oaths.Sexual intercourse and reproduction propagated the slavery of spirit to flesh, hence procreation was considered undesirable. Informal relationships were considered preferable to marriage among Cathar credentes. Perfecti were supposed to have observed complete celibacy, and eventual separation from a partner would be necessary for those who would become Perfecti. For the credentes however, sexual activity was not prohibited, but procreation was strongly discouraged, resulting in the charge by their opponents of sexual perversion. The common British insult "bugger

Bugger

Bugger is a slang word used in the vernacular British English, Australian English, Canadian English, New Zealand English, South African English, Caribbean English, Sri Lankan English and occasionally also in Malaysian English and Singaporean English, and rarely American English...

" is derived from "Bulgar", the notion that Cathars followed the "Bulgarian heresy

Bogomilism

Bogomilism was a Gnostic religiopolitical sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar Petar I in the 10th century...

" whose teaching included sexual activities which skirted procreation.

Killing was abhorrent to the Cathars. Consequently, abstention from all animal food (sometimes exempting fish

Pescetarianism

Pescetarianism is the practice of a diet that includes seafood but not the flesh of other animals.In addition to fish and/or shellfish, a pescetarian diet typically includes all of vegetables, fruit, nuts, grains, beans, eggs and dairy...

) was enjoined of the Perfecti. The Perfecti apparently avoided eating anything considered to be a by-product of sexual reproduction — war and capital punishment

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

were also condemned, an abnormality in the medieval age. As a consequence of their rejection of oaths, Cathars also rejected marriage vows.

Cathar teachings, in theological intent and practical consequence, brought condemnation from Catholic authorities both religious and secular, as being inimical to the Catholic faith and of feudal social order.

Organization

The Cathar Church of the Languedoc had a relatively flat structure distinguishing between perfecti (a term they did not use, instead bonhommes) and credentes. By about 1140 liturgy and a system of doctrine had been established. It created a number of bishoprics, first at Albi (around 1165)- hence the term Albigensians - , and after the 1167 Council at Saint-Félix-Lauragais sites at Toulouse, Carcassonne and Agen, so that by 1200 four bishoprics were in existence.In about 1225, during a lull in the Albigensian Crusade

Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade or Cathar Crusade was a 20-year military campaign initiated by the Catholic Church to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc...

, the bishopric of Razes was added. Bishops were supported by their two assistants, a filius maior and filius minor, typically the former would be the successor, further, these were assisted by deacons. The perfecti were the spiritual elite, highly respected by many of the local people, leading a life of austerity and charity. In the apostolic fashion they ministered to the people travelling in pairs.

Suppression

In 1147, Pope Eugene IIIPope Eugene III

Pope Blessed Eugene III , born Bernardo da Pisa, was Pope from 1145 to 1153. He was the first Cistercian to become Pope.-Early life:...

sent a legate

Papal legate

A papal legate – from the Latin, authentic Roman title Legatus – is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic Church. He is empowered on matters of Catholic Faith and for the settlement of ecclesiastical matters....

to the Cathar district in order to arrest the progress of the Cathars. The few isolated successes of Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, O.Cist was a French abbot and the primary builder of the reforming Cistercian order.After the death of his mother, Bernard sought admission into the Cistercian order. Three years later, he was sent to found a new abbey at an isolated clearing in a glen known as the Val...

could not obscure the poor results of this mission, which clearly showed the power of the sect in the Languedoc at that period. The missions of Cardinal Peter of St. Chrysogonus to Toulouse and the Toulousain in 1178, and of Henry of Marcy

Henry of Marcy

Blessed Henry of Marcy was a Cistercian abbot first of Hautecombe and then of Clairvaux from 1177 until 1179. He was created Cardinal Bishop of Albano at the Third Lateran Council in 1179....

, cardinal-bishop of Albano, in 1180–81, obtained merely momentary successes. Henry's armed expedition, which took the stronghold at Lavaur

Lavaur, Tarn

Lavaur is a commune in the Tarn department in southern France.It lies 37 km southeast of Montauban by rail.-History:Lavaur was taken in 1211 by Simon de Montfort during the wars of the Albigenses, a monument marking the site where Dame Giraude de Laurac was killed, being thrown down a well...

, did not extinguish the movement.

Decisions of Catholic Church councils—in particular, those of the Council of Tours

Tours

Tours is a city in central France, the capital of the Indre-et-Loire department.It is located on the lower reaches of the river Loire, between Orléans and the Atlantic coast. Touraine, the region around Tours, is known for its wines, the alleged perfection of its local spoken French, and for the...

(1163) and of the Third Council of the Lateran

Third Council of the Lateran

The Third Council of the Lateran met in March 1179 as the eleventh ecumenical council. Pope Alexander III presided and 302 bishops attended.By agreement reached at the Peace of Venice in 1177 the bitter conflict between Alexander III and Emperor Frederick I was brought to an end...

(1179)—had scarcely more effect upon the Cathars. When Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III was Pope from 8 January 1198 until his death. His birth name was Lotario dei Conti di Segni, sometimes anglicised to Lothar of Segni....

came to power in 1198, he was resolved to deal with them.

At first Pope Innocent III tried pacific conversion, and sent a number of legates into the Cathar regions. They had to contend not only with the Cathars, the nobles who protected them, and the people who venerated them, but also with many of the bishop

Bishop

A bishop is an ordained or consecrated member of the Christian clergy who is generally entrusted with a position of authority and oversight. Within the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Churches, in the Assyrian Church of the East, in the Independent Catholic Churches, and in the...

s of the region, who resented the considerable authority the Pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

had conferred upon his legates. In 1204, Innocent III suspended a number of bishops in Occitania

Occitania

Occitania , also sometimes lo País d'Òc, "the Oc Country"), is the region in southern Europe where Occitan was historically the main language spoken, and where it is sometimes still used, for the most part as a second language...

; in 1205 he appointed a new and vigorous bishop of Toulouse, the former troubadour

Troubadour

A troubadour was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages . Since the word "troubadour" is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a trobairitz....

Foulques

Folquet de Marselha

Folquet de Marselha, alternatively Folquet de Marseille, Foulques de Toulouse, Fulk of Toulouse came from a Genoese merchant family who lived in Marseille...

. In 1206 Diego of Osma and his canon, the future Saint Dominic

Saint Dominic

Saint Dominic , also known as Dominic of Osma, often called Dominic de Guzmán and Domingo Félix de Guzmán was the founder of the Friars Preachers, popularly called the Dominicans or Order of Preachers , a Catholic religious order...

, began a programme of conversion in Languedoc; as part of this, Catholic-Cathar public debates were held at Verfeil, Servian, Pamiers

Pamiers

Pamiers is a commune in the Ariège department in the Midi-Pyrénées region in southwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department. Although Pamiers is the largest city in Ariège, the capital is the smaller town of Foix...

, Montréal

Montréal, Aude

Montréal is a commune just south of Carcassonne in the Aude department, a part of the ancient Languedoc province and the present-day Languedoc-Roussillon region in southern France.-Population:-References:*...

and elsewhere.

Saint Dominic

Saint Dominic

Saint Dominic , also known as Dominic of Osma, often called Dominic de Guzmán and Domingo Félix de Guzmán was the founder of the Friars Preachers, popularly called the Dominicans or Order of Preachers , a Catholic religious order...

met and debated the Cathars in 1203 during his mission to the Languedoc. He concluded that only preachers who displayed real sanctity, humility and asceticism could win over convinced Cathar believers. The official Church as a rule did not possess these spiritual warrants. His conviction led eventually to the establishment of the Dominican Order

Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

in 1216. The order was to live up to the terms of his famous rebuke, "Zeal must be met by zeal, humility by humility, false sanctity by real sanctity, preaching falsehood by preaching truth." However, even St. Dominic managed only a few converts among the Cathari.

Albigensian Crusade

In January 1208 the papal legate, Pierre de CastelnauPierre de Castelnau

Pierre de Castelnau , French ecclesiastic, was born in the diocese of Montpellier.In 1199 he was archdeacon of Maguelonne, and was appointed by Pope Innocent III as one of the legates for the suppression of the Cathar heresy in Languedoc.In 1202, when a monk in the Cistercian abbey of Fontfroide,...

was sent to meet the ruler of the area, Count Raymond VI of Toulouse

Raymond VI of Toulouse

Raymond VI was count of Toulouse and marquis of Provence from 1194 to 1222. He was also count of Melgueil from 1173 to 1190.-Early life:...

. Known for excommunicating noblemen who protected the Cathars, Castelnau excommunicated Raymond as an abettor

Abettor