Anglo-Iraqi War

Encyclopedia

The Anglo-Iraqi War was the name of the British campaign against the rebel

government of Rashid Ali in the Kingdom of Iraq

during the Second World War. The war lasted from 2 May to 31 May 1941. The campaign resulted in the re-occupation of Iraq

by British armed forces

and the return to power of the ousted pro-British Regent

of Iraq, Prince

'Abd al-Ilah

. The campaign further fuelled nationalist

resentment in Iraq toward the British-supported Hashemite

monarchy

.

(also referred to as Mesopotamia

) was governed by the United Kingdom

under a League of Nations mandate

; the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, until 1932 when Iraq became nominally independent. Before granting independence, the United Kingdom concluded the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty

of 1930. This treaty had several conditions, which included permission to establish military bases for British use and provide all facilities for the unrestricted movement of British forces through the country upon request to the Iraqi government. The conditions of the treaty were imposed by the United Kingdom to ensure continued control of Iraq's petroleum

resources. Many Iraqis resented these conditions and felt that their country and its monarchy were still under the effective control of the British Government.

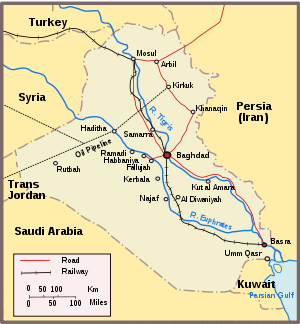

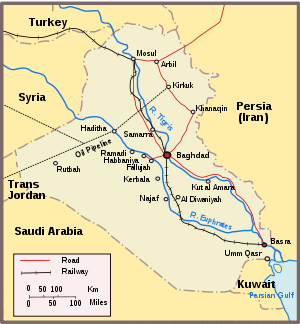

However, following 1937, no British troops were left in Iraq and the Iraqi government had become solely responsible for the internal security of the country. In accordance with the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, the British Royal Air Force

(RAF) had been allowed to retain two bases; RAF Shaibah

, near Basra

, and RAF Habbaniya

, between Ramadi

and Fallujah

. Air Vice-Marshal

H. G. Smart

was the commander of RAF Habbaniya and Air Officer Commanding

of all RAF forces in Iraq

. The bases in Iraq had a dual role: protecting Britain's petroleum interests and maintaining a link in the air route between Egypt

and India

. In addition RAF Habbaniya was also a training base and was protected by a small detachment of RAF ground forces

and locally raised Iraqi troops.

With the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 the Iraqi Government broke off diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany

. However, the United Kingdom wanted the Iraqi Government to take a further step and declare war upon Germany. In March 1940, the nationalist and anti-British Rashid Ali replaced Nuri as-Said

. Ali made covert contacts with German representatives in the Middle East

, though he was not yet an openly pro-Axis supporter.

In June 1940, when Fascist Italy joined the war, on the side of Germany, the Iraqi government did not break off diplomatic relations, as they had done with Germany. Thus the Italian Legation in Baghdad became the chief centre for Axis propaganda and for fomenting anti-British feeling. In this they were aided by Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

. The Grand Mufti had fled from Palestine shortly before the outbreak of war and later received asylum in Baghdad.

In January 1941, there was a political crisis within Iraq and the threat of civil war was looming. Rashid Ali resigned as Prime Minister

of Iraq and was replaced by Taha al-Hashimi

. Public opinion started to change in Iraq as the Italians suffered a series of setbacks in the African and Mediterranean theatre.

of Iraq, Amir Abdul Illah

, learnt of a plot to arrest him and he fled Baghdad

for RAF Habbaniya. From Habbaniya he was flown to Basra and given refuge on the gunboat

HMS Cockchafer

.

On 1 April, Rashid Ali, along with four top level Army and Air Force officers; known as the "Golden Square

," seized power via a coup d'état

and Rashid Ali proclaimed himself Chief of the "National Defence Government." The Golden Square deposed Prime Minister Taha al-Hashimi

and Rashid Ali once again became Prime Minister of Iraq. Rashid Ali did not move to overthrow the monarchy

and named a new Regent to King Faisal II

, Sherif Sharaf. The leaders of the "National Defence Government" proceeded to arrest many pro-British citizens and politicians. However, a good number of those sought managed to escape by various means through Amman

in Transjordan

.

The immediate plans of Iraq's new leaders were to refuse further concessions to the United Kingdom, to retain diplomatic links with Fascist Italy, and to expel most prominent pro-British politicians from the country. The plotters of the coup considered the United Kingdom to be weak and believed that its government would negotiate with their new government regardless of its legality. On 17 April, Rashid Ali, on behalf of the "National Defence Government," asked Germany for military assistance in the event of war with the British. Ultimately, Rashid Ali attempted to restrict British rights guaranteed under Article 5 of the 1930 treaty when he insisted that newly arrived British troops be quickly transported through Iraq and to Palestine.

The RIrA was composed of four infantry divisions with some 60,000 men distributed for the most part into four infantry divisions and one mechanized brigade. The 1st

and 3rd

Divisions were stationed near Baghdad. Also based within Baghdad was the Independent Mechanized Brigade, composed of a light tank company, an armoured car company, two battalions of "mechanized" infantry transported in trucks, a "mechanized" machine-gun company, and a "mechanized" artillery brigade. The Iraqi 2nd Division

was stationed in Kirkuk

and the 4th Division

was in Al Diwaniyah

on the main rail line from Baghdad to Basra. Unlike the modern use of the term "mechanized," in 1941 "mechanized" for the RIrA meant transported by trucks.

In addition to the regular army, the Iraqis fielded some police units and approximately 500 "irregulars

" under Arab guerrilla leader Fawzi al-Qawuqji

. Fawzi al-Qawuqji was a ruthless fighter who did not hesitate to murder or mutilate his prisoners. For the most part, Fawzi al-Qawuqji and his irregulars operated in the area between Rutbah and Ramadi

before being chased back into Syria.

The RIrAF had a total of 116 aircraft in 7 squadrons and a training school. Between 50 and 60 Iraqi aircraft were in serviceable condition. Most Iraqi fighter and bomber aircraft were located at the newly re-named "Rashid Airfield" in Baghdad (formerly RAF Hinaidi

The RIrAF had a total of 116 aircraft in 7 squadrons and a training school. Between 50 and 60 Iraqi aircraft were in serviceable condition. Most Iraqi fighter and bomber aircraft were located at the newly re-named "Rashid Airfield" in Baghdad (formerly RAF Hinaidi

) or in Mosul

. Four squadrons and the Flying Training School were based in Baghdad. Two squadrons with close co-operation and general purpose aircraft were based in Mosul. The Iraqis flew an assortment of aircraft types that included Gladiator

biplane fighters, Breda 65 fighter bombers, Savoia SM79

medium bombers, Northrop/Douglas 8A

fighter bombers, Hawker Nisr

biplane close co-operation aircraft, Vickers Vincent biplane light bombers, de Havilland Dragon

biplane general purpose aircraft, de Havilland Dragonfly

biplane general purpose aircraft, and Tiger Moth

biplane trainers. In addition to the 116 aircraft, the Iraqi Air Force had another 9 aircraft not allocated to specific squadrons and 19 aircraft available in reserve.

The Royal Iraqi Navy (RIrN) had four 100-ton Thornycroft

gunboat

s, one pilot vessel, and one minesweeper

. All were armed and all were based in the Shatt al-Arab waterways.

forces available within Iraq were very limited. Air Vice-Marshal Smart commanded the Royal Air Force

-led inter-service

command

, "British Forces in Iraq

."

Ground forces available to Smart included Number 1 Armoured Car Company RAF

and six companies of Assyrian Levies

. The armoured car company comprised 18 ancient Rolls Royce armoured cars

of World War I

vintage. The Assyrian Levies totaled almost 2,000 locally raised officers and other ranks under the command of about 20 British officers.

At RAF Habbaniah, the 4th Service Flying Training School had a wide variety of obsolescent bombers, fighters and trainers. However, many of the 84 aircraft available could not be flown or were not appropriate for offensive use. In addition, at the start of battle, there were about 1000 RAF personnel but only 39 pilots. All told, on 1 April, the British had 3 old Gladiator

biplane fighters, 30 Hawker Audax biplane close co-operation aircraft, 7 Fairey Gordon

biplane bombers, 27 twin-engine Oxford

trainers, 28 Hawker Hart

biplane light bombers (the "bomber" version of the Hawker Audax), 20 Hart trainers, and 1 Bristol Blenheim Mk1

bomber. The Gladiators were used as officers' runabouts. The Hawker Audaxes could carry eight 20 lb bombs (12 Audaxes were modified to carry two 250 lb bombs). The Fairy Gordons could each carry two 250 lb bombs. The Oxfords were converted from carrying smoke bombs to carrying eight 20 lb bombs. The Hawker Harts could carry two 250 lb bombs. The Hawker trainers had no weaponry. The Blenheim left for good on 3 May. There was also an "RAF Iraq Communications Flight" at Habbaniya with 3 Vickers Valentia flying boats.

At RAF Shaibah there was the No. 244 Bomber Squadron

with some Vickers Vincents.

The naval forces available to support British actions in Iraq were part of the East Indies Station

and included vessels from the Royal Navy

, the Royal Australian Navy

, the Royal New Zealand Navy

, and the Royal Indian Navy

.

Winston Churchill

advocated the non-recognition of Rashid Ali or his illegal

"National Defence Government."

On 2 April, Sir

Kinahan Cornwallis

, the new British Ambassador to Iraq, arrived in Baghdad. He had much experience in Mesopotamia

and had spent twenty years in the country as the advisor to King Faisal I

. Cornwallis was highly regarded and he was sent to Iraq with the understanding that he would be able to hold a more forceful line with the new Iraqi government than had hitherto been the case. Unfortunately, Cornwallis arrived in Iraq too late to prevent the outbreak of war.

On 6 April, AVM Smart requested reinforcements, but his request was rejected by Air Officer Commanding

in the Middle East

Sir Arthur Longmore

. At this point in the war

, the situation developing in Iraq did not figure highly in British priorities. Churchill wrote, "Libya

counts first, withdrawal of troops from Greece

second. Tobruk

shipping, unless indispensable to victory, must be fitted in as convenient. Iraq can be ignored and Crete

worked up later."

The British Chiefs-of-Staff

, with the vocal support of the Commander-in-Chief, India

General

Claude Auchinleck

, were in favour of armed intervention. However, the three Commander-in-Chief

s, of the British armed forces in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean area, already heavily committed with fighting in Libya

, in East Africa

, and in Greece

, suggested the only forces they would be able to use against Iraq was a single battalion of infantry, based within Palestine, and the aircraft already based within Iraq. The Government of India

had a long standing commitment to prepare one infantry division in case it should be needed to protect the Anglo-Iranian oilfields and in July 1940 the leading brigade of this division, the 5th Indian Infantry Division, was ordered to be dispatched to Iraq. However, in August the division was placed under the command of Middle East Command

and was diverted to the Sudan

. Since then, India Command had been investigating the move of troops by air from India to RAF Shaibah.

, and asked him what force could be quickly sent from India to Iraq. Amery contacted General Auchinleck and Lord Linlithgow

, Viceroy and Governor-General of India

, the same day. The response from India was that the majority of one brigade group

, that was due to set sail for Malaya

on 10 April, could be diverted to Basra and the rest of the group dispatched ten days later. In addition 390 British infantrymen could be flown from India into RAF Shaibah. It was also stated that when shipping became available this force could quickly be built up to a division in strength. On 10 April this offer was accepted by London and the move of these forces was codenamed Operation Sabine. On the same day General Archibald Wavell

, Commander-in-Chief of Middle East Command, informed London that he could no longer spare the one battalion in Palestine and urged for firm diplomatic action, and possibly a demonstration of air strength, to be taken rather than military intervention.

On 10 April, Major-General William Fraser

assumed control over Iraqforce

, the land forces from India headed for Basra. Fraser was given the following instructions: (i) "The object of his force was to occupy the Basra-Shabai area in order to ensure the safe disembarkation of further reinforcements and to enable a base to be established in that area. (ii) The attitude of the Iraqi Army and local authorities was still uncertain and it was possible that attempts might be made to oppose the disembarkation of his force. In framing his plan for disembarkation, he was, therefore, to act in the closest concert with the officer commanding the Naval Forces. (iii) Should the disembarkation be opposed, he was to overcome the Iraqi forces by force and occupy suitable defensive positions ashore as quickly as possible. (iv) The greatest care was to be taken not to infringe on the neutrality of Iran."

Starting in early April, preparations in case of hostilities were made at Habbaniya. Aircraft were modified to allow them to carry bombs, while light bombers such as the Hawker Audax

were modified to carry larger bombs.

On 12 April, Convoy BP7, left Karachi

. The convoy was composed of eight transports escorted by the Grimsby Class sloop

HMAS Yarra

. The forces transported by the convoy were under the command of Major-General Fraser, the commanding officer of the 10th Indian Infantry Division

. The forces being transported consisted of two senior staff officers from the l0th Indian Division headquarters, the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade

, the personnel of the Royal Artillery's 3rd Field Regiment; but without their guns, and certain ancillary troops.

On 13 April, the Royal Navy

On 13 April, the Royal Navy

force of four ships in the Persian Gulf

were reinforced by the aircraft carrier

HMS Hermes

and two light cruiser

s, the HMS Emerald

and the HMNZS Leander

. The HMS Hermes carried the Fairey Swordfish

torpedo bombers of 814 Squadron

. The naval vessels which covered the disembarkation at Basra consisted of the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes, the light cruiser HMS Emerald, the light cruiser HMNZS Leander, the sloop

HMS Falmouth

, the gunboat HMS Cockchafer, the sloop HMS Seabelle, the minesweeper

sloop HMIS Lawrence, and the sloop HMAS Yarra.

On the morning of 15 April, Convoy BP7 was met at sea by HMS Seabelle from Basra. Later in the day the escort was reinforced by HMS Falmouth. On I7 April, the convoy was joined by HMIS Lawrence and then proceeded towards the entrance of the Shatt al-Arab. On 18 April, the convoy moved up the Shatt al-Arab and arrived at Basra at 0930 hrs. HMS Emerald was already in Basra. On the same day, the HMNZS Leander was released from support duties in the Persian Gulf.

On 16 April, the Iraqi Government was informed that the British were going to invoke the Anglo-Iraq treaty to move troops through the country to Palestine. Rashid Ali raised no objection.

(1st KORR) was flown into RAF Shaibah from Karachi in India. Colonel

Ouvry Roberts

, the Chief Staff Officer of the 10th Indian Infantry Division, arrived with the 1st KORR. By 18 April, the airlift

of the 1st KORR to Shaibah was completed. The troop-carrying aircraft

used for this airlift were 7 Valentias and 4 Atalantas

supplemented by 4 DC-2s

which had recently arrived in India.

On 18 April, the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade landed at Basra. Brigadier

Donald Powell

commanded this brigade. The 20th Indian Infantry Brigade included the 2nd battalion 8th Gurkha Rifles

, 2nd battalion 7th Gurkha Rifles

, and the 3rd battalion 11th Sikh Regiment

. The landing of the force transported by Convoy BP7 was covered by infantry of the 1st KORR which had arrived the previous day by air. The landing was unopposed.

By 19 April, the disembarkation of the force transported by Convoy BP7 at Basra was completed. On the same day, seven aircraft were flown into RAF Habbaniya to bolster the air force there. Following the landing of the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade, Rashid Ali requested that the brigade be moved quickly through the country and that no more troops should arrive until the previous force had left. Sir Kinahan Cornwallis, the British Ambassador to Iraq, referred the issue to London

and London replied that they had no interest in moving the troops out of the country and wanted to establish them within Iraq. Cornwallis was also instructed not to inform Rashid Ali who, as he had taken control of the country via a coup d'état, had no right to be informed about British troop movements.

On 20 April, Churchill had written to Anthony Eden

, the Foreign Secretary, and indicated that it should be made clear to Ambassador Cornwallis that the chief interest in sending troops to Iraq was the covering and establishment of a great assembly base near Basra. It was to be understood that what happened "up country," with the exception of Habbaniya, was at that time on an "altogether lower priority." Churchill went on to indicate that the treaty rights were invoked to cover the disembarkation, but that force would have been used if it had been required. Cornwallis was directed not to make agreements with an Iraqi government which had usurped its power. In addition, he was directed to avoid entangling himself with explanations to the Iraqis.

Also on 29 April, the British Ambassador, Sir Kinahan Cornwallis, advised that all British women and children should leave Baghdad; 230 civilians were escorted by road to Habbaniya and during the following days were gradually airlifted to Shaibah. A further 350 civilians took refuge in the British Embassy and 150 British civilians in the American Legation.

.

to the south of the base. Prior to dawn, reconnaissance aircraft were launched from RAF Habbaniya and reported that at least two battalions, with artillery, had taken up position on the plateau.

By May 1, the Iraqi forces surrounding Habbaniya had swelled to an infantry brigade, two mechanized battalions, a mechanized artillery brigade with 12 3.7-inch howitzers

, a field artillery brigade with 12 18-pounder cannons

and four 4.5-inch howitzers

, 12 Crossley six-wheeled armoured cars

, a number of Fiat light tanks

, a mechanized machine gun company, a mechanized signal company, and a mixed battery of anti-aircraft and anti-tank guns. This totaled 9,000 regular troops along with an undetermined number of tribal irregulars and about 50 guns.

, Air Vice-Marshal

H. G. Smart, stating that the plateau had been occupied for a training exercise. The envoy also informed Air Vice-Marshal Smart that all flying should cease immediately and demanded that no movements, either ground or air, take place from the base. Air Vice-Marshal Smart replied that any interference with the normal training carried out at the base would be treated as an act of war. Sir Kinahan Cornwallis, the British Ambassador located at the British Embassy in Baghdad and in contact with RAF Habbaniya via wireless

, fully supported this action.

British reconnaissance aircraft, already in the air, continued to relay information to the base; they reported that the Iraqi positions on the plateau were being steadily reinforced, they also reported that Iraqi troops had occupied the town of Fallujah

.

At 11:30 hours, the Iraqi envoy again made contact with Air Vice-Marshal Sharp and accused the British of violating the Anglo-Iraqi treaty. Air Vice-Marshal Smart replied that this was a political matter and he would have to refer the accusation to Ambassador Cornwallis. Meanwhile, Iraqi forces had now occupied vital bridges over the Tigris

and Euphrates

rivers as well as reinforcing their garrison at Ramadi

; thus effectively cutting off RAF Habbaniya except from the air.

Air Vice-Marshal Smart controlled a base with a population of around 9,000 civilians that was indefensible with the force of roughly 2,500 men currently available. The 2,500 men included air crew and Assyrian Levies

and the loyalty of the Assyrian Levies had yet to be proven. There was also the possibility that the Iraqi rebels were waiting for dark before attacking. As a result, Air Vice-Marshal Smart decided to accept the tactical risks and stick to Middle East Command's policy of avoiding aggravation in Iraq by, for the moment, not launching a pre-emptive strike.

bombers to RAF Shaibah. The British Ambassador signalled the Foreign Office

that he regarded the Iraqi actions as an act of war, which required an immediate air response. He also informed them that he intended to demand the withdrawal of the Iraqi forces and permission to launch air strikes to restore control, even if the Iraqi troops overlooking Habbaniya did withdraw it would only postpone aerial attacks.

Still in contact with the British Embassy and with the approval of Ambassador Cornwallis, Air Vice-Marshal Smart decided to launch air strikes against the plateau the following morning without issuing an ultimatum

; as with foreknowledge the Iraqi force might start to shell the airbase and halt any attempt to launch aircraft.

s were launched against the Iraqis from RAF Habbaniya. While the largest number of British troops were ultimately assembled in the Basra area, an advance from Basra was not immediately practicable and did not get under way until after Rashid Ali's government was already collapsing.

Initially, the Iraqi siege of RAF Habbaniya and the ability of the besieged

British force there to withstand the siege was the primary focus of the conflict. Air Vice-Marshal Sharp's decision to strike at the Iraqi positions with air power

not only allowed his force to withstand the siege, but to neutralize much of Iraq's air power. While the relief force from Palestine arrived in Habbaniya after the siege was over, it did allow an immediate change over to the offensive.

attacks with as many aircraft as possible. At 05:00 on 2 May, 33 aircraft from Habbaniya, out of the 56 operational aircraft based there, and eight Wellington bombers, from Shaibah, began their attack. Within minutes the Iraqis on the escarpment replied by shelling the base, damaging some planes on the ground. The Royal Iraqi Air Force (RIrAF) also joined in the fray over Habbaniya. RAF attacks were also made against Iraqi air fields near Baghdad, which resulted in 22 aircraft being destroyed on the ground; further attacks were made against the railway and Iraqi positions near Shaibah, with the loss of two planes. Throughout the day the pilots, from Habbaniya, flew 193 sortie

s and claimed direct hits on Iraqi transports, armoured cars and artillery pieces; however five aircraft had been destroyed and several others had been put out of service. On the base 13 people had lost their lives and a further 29 wounded, including nine civilians.

By the end of the day, the Iraqi force, outside of Habbaniya, had grown to roughly a brigade

.

Iraqi army were preparing for morning prayers when the attack was launched. When the news reached the Grand Mufti in Baghdad, he immediately declared a jihad

against the United Kingdom. In addition, the flow of Iraq Petroleum Company

oil to Haifa

was completely severed.

On 3 May, the British bombing of the Iraqis continued; troop and gun positions on the plateau were targeted as well the supply line to Baghdad. The RIrAF base at Rashid was also attacked and an Iraqi Savoia SM 79

bomber was intercepted and shot down heading for Habbaniya. The following day further air attacks were carried out on RIrA troop positions and the RIrAF. A bombing raid was conducted by eight Wellington bombers on Rashid, which was briefly engaged by Iraqi fighters but no losses were suffered. Bristol Blenheim

s, escorted by Hurricanes

, also conducted strafing attacks against airfields at Baghdad, Rashid and Mosul

.

On 5 May, due to a car accident, Air Vice-Marshal Smart was evacuated to Basra and then onward to India. Colonel Roberts assumed de facto

command of the land operations at RAF Habbaniya after the departure of Smart. Air Vice-Marshal John D'Albiac

, from Greece, was to take command over aerial forces at Habbaniya and of all RAF forces in Iraq. Further aerial attacks were conducted against the plateau during the day and following nightfall Colonel Roberts ordered a sortie by the King's Own Royal Regiment

(1st KORR) against the Iraqi positions on the plateau. The attack was supported by the Assyrian levies, some RAF armoured cars and two First World War-era 4.5 inch howitzers

. The 4.5 in howitzers had been put in working order by some British gunners but had previously been decorating the entrance of the base's officers' mess.

, one Italian tank, ten Crossley armoured cars, 79 trucks, three 20 mm anti-aircraft guns with 2,500 shells, 45 Bren light machine-guns, eleven Vickers machine gun

s, and 340 rifles with 500,000 rounds of ammunition.

The investment of Habbaniya, by Iraqi forces, had come to an end. The British garrison had suffered 13 men killed, 21 badly wounded, and four men were suffering battle fatigue

. The garrison had inflicted between 500–1000 casualties on the besieging force and numerous more men had been taken prisoner. On 6 May alone, 408 Iraqi troops were captured. The Chiefs-of-Staff

now ordered that it was essential to continue to hit the Iraqi armed forces hard by every means available but avoiding direct attacks on the civilian population. The British objective was to safeguard British interests from Axis intervention in Iraq, to defeat the rebels and discredit Rashid’s government.

road, occupied by Iraqi troops. The 1st KORR and the Assyrian levies, supported by the RAF armoured cars, assaulted the position driving the Iraqis out and taking over 300 prisoners. The Iraqi force retreating from Habbaniya met with an Iraqi column moving towards Habbaniya from Fallujah in the afternoon. The two Iraqi forces met around 5 miles (8 km) east of Habbaniya on the Fallujah road. The reinforcing Iraqi column was soon spotted and 40 aircraft from RAF Habbaniya arrived to attack; the two Iraqi columns were paralysed and within two hours, more than 1,000 Iraqi casualties were inflicted and further prisoners were taken. Later in the afternoon Iraqi aircraft carried out three raids on the airbase and inflicted some damage.

Over the course of the next few days, the RAF, from Habbaniya and Shaibah, effectively eliminated the RIrAF. However, from 11 May, German Air Force (Luftwaffe

) aircraft took the place of the Iraqi aircraft.

On 3 May, German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

persuaded German dictator Adolf Hitler

to secretly return Dr. Fritz Grobba

to Iraq to head up a diplomatic mission to channel support to the Rashid Ali regime. The British quickly learned of the German arrangements through intercepted Italian diplomatic transmissions.

On 6 May, in accordance with the Paris Protocols

, Germany concluded a deal with the Vichy French government to release war materials, including aircraft, from sealed stockpiles in Syria

and transport them to the Iraqis. The French also agreed to allow passage of other weapons and material as well as loaning several airbases in northern Syria, to Germany, for the transport of German aircraft to Iraq. Between 9 May and the end of the month, about one-hundred German and about twenty Italian aircraft landed on Syrian airfields.

Werner Junck

received orders that he was to take a small force to Iraq, where they were to operate out of Mosul

. The British quickly learned of the German arrangements through intercepted Italian diplomatic transmissions. Between 10 and 15 May the aircraft arrived in Mosul via Vichy French airbases, in Syria

, and then commenced regular aerial attacks on British forces. The arrival of these aircraft was the direct result of fevered consultations between Baghdad and Berlin in the days following Air Vice-Marshal Smart's strikes on the Iraqi forces above Habbaniya. The Luftwaffe force, under the direction of Lieutenant General Hans Jeschonnek

, was named "Flyer Command Iraq

" (Fliegerführer Irak

) and was under the tactical command of Colonel Werner Junck. At least 20 bombers were initially promised however in the end Junck's unit consisted of between 21 and 29 aircraft all painted with Royal Iraqi Air Force markings..

On 11 May, the first three Luftwaffe planes arrived at Mosul via Syria. On 15 May, an aircraft carrying Major

On 11 May, the first three Luftwaffe planes arrived at Mosul via Syria. On 15 May, an aircraft carrying Major

Axel von Blomberg

flew from Mosul to Baghdad. Axel von Blomberg was part of the military mission to Iraq which had the cover name "Special Staff F

" (Sonderstab F) commanded by General

Hellmuth Felmy

. Axel von Blomberg was tasked with heading up a Brandenburgers Commando

reconnaissance group in Iraq that was to precede Fliegerführer Irak. Axel von Blomberg was also tasked with integrating Fliegerführer Irak with Iraqi forces in operations against the British. On its approach to Baghdad, the aircraft was engaged by Iraqi ground fire. As a result, von Blomberg was shot and was found to be dead when the aircraft landed.

During this time, Germany and the Soviet Union

were still allies (due to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939) and this was reflected in Soviet actions regarding Iraq. On 12 May, according to Time Magazine, the Soviet Union recognized Rashid Ali's "National Defence Government." On 18 May, the New York Times indicated that an Iraqi-Soviet exchange of notes at Ankara

established diplomatic relations between the two governments.

. The Iraqis took delivery of 15,500 rifles, with six-million rounds of ammunition, 200 machine guns, with 900 belts of ammunition, and four 75 mm field guns together with 10,000 shells. Two additional deliveries were made on 26 and 28 May, which included eight 155 mm guns, with 6,000 shells, 354 machine pistols, 30,000 grenades, and 32 trucks.

On 14 May, according to Winston Churchill, the RAF was authorized to act against German aircraft in Syria and on Vichy French airfields. On the same day, two over-laden Heinkel 111 bombers were left in Palmyra

in central Syria because they had damaged rear wheels. British fighters entered French air space and strafed and disabled the damaged Heinkels.

By 18 May, Junck's force had been whittled down to 8 Messerschmitt 110 fighters, 4 Heinkel 111 bombers, and 2 Junkers 52 transports. This represented roughly a 30 percent loss of his original force. With few replacements available, no spares, poor fuel, and aggressive attacks by the British, this rate of attrition did not bode well for Fliegerführer Irak. Indeed, near the end of May, Junck had lost 14 Messerschmitts and 5 Heinkels.

s of the Royal Italian Air Force (Regia Aeronautica Italiana

) arrived at Mosul to operate under German command. By 29 May, Italian aircraft were reported in the skies over Baghdad. According to Churchill, the Italian aircraft accomplished nothing.

Plans were drawn up to supply troops, but the German high command was hesitant and required the permission of Turkey

for passage. In the end the Luftwaffe found conditions in Iraq intolerable, as spare parts were not available and even the quality of aircraft fuel was far below the Luftwaffe's requirements. With each passing day fewer aircraft remained serviceable and, ultimately, all Luftwaffe personnel were evacuated on the last remaining Heinkel He 111.

for the "National Defence Government." On 1 May, the police opened fire on British workers in Rutbah. The police were reportedly joined by the Arab guerilla leader Fawzi al-Qawuqji

and his irregulars

. In response to these Iraqi actions, Major-General Clark had ordered the mechanized squadron of the Transjordan Frontier Force

(TJFF), which was based at H4, to seize the fort for the British. When the members of the TJFF refused, they were marched back to H3 and disarmed.

By the end of the first day of airstrikes, there had been reports that elements of the Royal Iraqi Army (RIrA) was advancing on the town of Rutbah. C Company of the 1st Battalion The Essex Regiment

was ordered to travel from Palestine to pumping station H4, between Haifa and Iraq; from here the company would join a detachment of RAF armoured cars

and defend the position from the Iraqi rebels.

On May 4, Churchill ordered Wavell to dispatch a force from Palestine. On 5 May, Wavell was placed in command of operations in northern Iraq and General

Henry Maitland Wilson

was called back from Greece to take command of forces in Palestine and Transjordan. The Defence Committee and Chiefs-of-Staff

rationale for taking military action against the Iraqi rebels was that they needed to secure the country from Axis intervention and considered Rashid Ali to have been conspiring with the Axis powers. The Chiefs-of-Staff accepted full responsibility for the dispatch of troops to Iraq.

On 8 May, the fort at Rutbah was still occupied by the Iraqi Desert Police and by Fawzi al-Qawuqji's irregulars. But, by this date, the fort was invested by the Arab Legion

. On 9 May, H4-based Blenheims of 203 Squadron

bombed the Iraqis in the fort. However, even with the bombing, the Iraqis maintained control of the fort and the Arab Legion was unable to take it by force of arms. The Legionnaires returned to H3 to replenish water and ammunition supplies. On 10 May, the Iraqis abandoned the fort, and Glubb Pasha and the Arab Legion returned and occupied it.

, short for Habbaniya Force. The force was placed under the command of Major-General George Clark

. Clark was already the commander of the 1st Cavalry Division which included the 4th Cavalry Brigade

, the 5th Cavalry Brigade

, and the 6th Cavalry Brigade

. After Wavell complained that using any of the force stationed in Palestine for service in Iraq would put Palestine and Egypt at risk, Churchill wrote Hastings Ismay, Secretary of the Chiefs-of-Staff Committee, and asked: "Why would the force mentioned, which seems considerable, be deemed insufficient to deal with the Iraq Army?" Concerning the 1st Cavalry Division specifically, he wrote: "Fancy having kept the cavalry division in Palestine all this time without having the rudiments of a mobile column organized!" On balance, Wavell wrote that the 1st Cavalry Division in Palestine had been stripped of its artillery, its Engineers, its Signals, and its transport to provide for the needs of other formations in Greece, North Africa, and East Africa. While one motorised cavalry brigade could be provided, this was only possible by pooling the whole of the divisional motor transport.

It was after the TJFF refused to enter Iraq that Clark decided to divide Habforce into two columns. The first column was a flying column

codenamed Kingcol

. Kingcol was named after its commanding officer, Brigadier

James Kingstone

, and was composed of the 4th Cavalry Brigade

, two companies of the 1st battalion The Essex Regiment, the Number 2 Armoured Car Company RAF

, and a battery of 25 pounder howitzers

from the 60th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery

. The second column, the Habforce main force, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel J. S. Nichols, was composed of the remaining elements of the 1st battalion The Essex Regiment, the remainder of the 60th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, one anti-tank battery, and ancillary services. In addition to Kingcol and the Habforce main force, there was available to Major-General Clark a 400-man strong detachment of the Arab Legion

(al-Jaysh al-Arabī) in the Emirate of Transjordan

. The Arab Legion consisted of three mechanized squadrons transported in a mixture of civilian Ford trucks and equipped with home-made armoured cars

. Unlike the TJFF, the Arab Legion was not part of the British Army

. Instead, the Arab Legion was the regular Army of Transjordan and it was commanded by Lieutenant-General John Bagot Glubb

, also known as "Glubb Pasha."

with orders to reach Habbaniya as quickly as possible. The occasion was the last all-horse exercise in British military history. On 13 May, Kingcol arrived in Rutbah but found no military presence there. Glubb Pasha and the Arab Legion had already moved on. The flying column under Brigadier Kingstone then conducted maintenance at Rutbah before moving on themselves.

On 15 May, the first contact was made with the Iraqi military when a Blenheim bomber strafed the column and dropped a bomb; however, no damage was inflicted and no casualties were sustained. On 16 May, further bombing attacks was made against the column when it was attacked by the Luftwaffe, again no damage was sustained however there were a few casualties.

Also on 15 May, Fraser went sick and was replaced as the commander of the 10th Indian Division; His illness had led to him losing the confidence of his own staff and he was replaced by the newly promoted Major-General William Slim

. Slim would go onto show himself as one of the most dynamic and innovative British commanders of the war. Also in early May, Longmore was replaced as Air Officer Commanding in the Middle East by his deputy, Sir Arthur Tedder.

was holding the town and bridge of Fallujah denying the road to Baghdad; a further Brigade group was holding the town of Ramadi, west of Habbaniya, barring all movement westwards. Colonel Roberts dismissed the idea of attacking Ramadi because it was still garrisoned heavily by the Iraqi Army and was largely cut off by self-imposed flooding. Roberts would leave Ramadi isolated and, instead, secure the strategically important bridge over the Euphrates at Fallujah.

In the week following the withdrawal of the Iraqi forces near Habbaniya, Colonel Roberts formed what became known as, the "Habbaniya Brigade." The brigade was formed by grouping the 1st battalion The Essex Regiment from Kingcol with further infantry reinforcements that had arrived from Basra, the 2nd battalion 4th Gurkha Rifles, and some light artillery.

During the night of the 17–18 May, elements of the Gurkha battalion, a company of RAF Assyrian Levies, RAF Armoured Cars and some captured Iraqi howitzers crossed the Euphrates using improvised cable ferries. They crossed the river at Sin el Dhibban and approached Falluja from the village of Saqlawiyah

. During the early hours of the day, one company of the 1st battalion KORR were air transported by 4 Valentias and landed on the Baghdad road beyond the town near Notch Fall. A company of RAF Assyrian Levies, supported by artillery from Kingcol, was ordered to secure the bridge across the river. Throughout the day the RAF bombed positions in the town and along the Baghdad road, avoiding a general bombardment of the town because of the civilian population. On 19 May, 57 aircraft began bombarding Iraqi positions within and around Fallujah before dropping leaflets requesting the garrison to surrender; no response was given and further bombing operations took place. The RAF dropped ten tons of bombs on Fallujah in 134 sorties. During the afternoon a ten minute bombardment of Iraqi trenches near the bridge was made before the Assyrian Levies advanced, covered by artillery fire. Facing little opposition they captured the bridge within 30 minutes, they were then met by an Iraqi envoy who offered the surrender of the garrison and the town. 300 prisoners were taken and no casualties had been sustained by the British force. The Luftwaffe responded to the British capture of the city by attacking the H airfield, destroying and damaging several aircraft and inflicting a number of casualties.

On 18 May, Major-General Clark and AVM D'Albiac arrived in Habbaniya by air. They determined not to interfere with the ongoing operations of Colonel Roberts. On 21 May, having secured Fallujah, Roberts returned to Shaibah and to his duties with the 10th Indian Infantry Division.

On 22 May, the Iraqi 6th Infantry Brigade, of the Iraqi 3rd Infantry Division

On 22 May, the Iraqi 6th Infantry Brigade, of the Iraqi 3rd Infantry Division

, conducted a counterattack

against the British forces within Fallujah. The Iraqi attack started at 02:30 hours supported by a number of Italian-built light tanks

. By 03:00 the Iraqis reached the north-eastern outskirts of the town. Two light tanks, which had penetrated into the town, were quickly destroyed. By dawn British counterattacks had pushed the Iraqis out of north-eastern Fallujah. The Iraqis now switched their attack to the south-eastern edge of the town. But this attack met stiff resistance from the start and made no progress. By 10:00 Kingstone arrived with reinforcements, from Habbaniya, who were immediately thrown into battle. The newly arrived infantry companies, of the Essex Regiment, methodically cleared the Iraqi positions house-by-house. By 18:00 the remaining Iraqis had fled or were taken prisoner, sniper fire was silenced, six Iraqi light tanks were captured, and the town was secure.

On 23 May, aircraft of Fliegerführer Irak made a belated appearance. British positions at Fallujuh were strafed on three separate occasions. But, while a nuisance, the attacks by the Luftwaffe accomplished little. Only one day earlier an air assault coordinated with Iraqi ground forces might have changed the outcome of the counterattack.

, under Brigadier Powell, were used to occupy these sites. Between 18 April and 29 April, two convoys had landed this brigade in the Basra area. 2nd battalion 8th Gurkha Rifles

guarded the RAF airfield at Shabaih, 3rd battalion 11th Sikh Regiment

secured the Maqil docks, and 2nd battalion 7th Gurkha Rifles

was held in reserve. Otherwise, no major operations took place in the Basra area. The principal difficulty was that there were insufficient troops to take over Maqil, Ashar, and Basra City concurrently. While the Iraqi troops in Basra agreed to withdraw on 2 May, they failed to do so.

On 6 May, the 21st Indian Infantry Brigade

under the command of Brigadier C. J. Weld

arrived and disembarked at Basra. This was the 10th Indian Infantry Division's second brigade to arrive in Iraq. The 21st Indian Infantry Brigade included 4th battalion 13th Frontier Force Rifles

, 2nd battalion 4th Gurkha Rifles, and 2nd battalion 10th Gurkha Rifles

.

On 8 May, operations in Iraq were passed, from under the control of Auchinleck's India Command, to the command of Wavell’s Middle East Command. Lieutenant-General Edward Quinan

On 8 May, operations in Iraq were passed, from under the control of Auchinleck's India Command, to the command of Wavell’s Middle East Command. Lieutenant-General Edward Quinan

arrived from India to replace Fraser as commander of Iraqforce. Quinan's immediate task was to secure Basra as a base. He was ordered by Wavell not to advance north until the co-operation of the local tribes was fully assured. Quinan could also not contemplate any move north for three months on account of the flooding of the Tigris and Euphrates. Directives were issued to Quinan prior to his assuming command. On 2 May, he had been directed as follows: "(a) Develop and organise the port of Basra to any extent necessary to enable such forces, our own or Allied, as might be required to operate in the Middle East including Egypt, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran, to be maintained. (b) Secure control of all means of communication, including all aerodromes and landing grounds in Iraq, and develop these to the extent requisite to enable the Port of Basra to function to its fullest capacity." Quinan was further instructed to "begin at once to plan a system of defences to protect the Basra Base against attack by armoured forces supported by strong air forces, and also to be ready to take special measures to protect: (i) Royal Air Force installations and personnel at Habbaniya and Shaiba. (ii) The lives of British subjects in Baghdad and elsewhere in Iraq. (iii) The Kirkuk oilfields and the pipe line to Haifa." Lastly, Quinan was directed "to make plans to protect the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company's installations and its British employees in South West Iran if necessary." Quinan was informed that "it was the intention to increase his force up to three infantry divisions and possibly also an armoured division, as soon as these troops could be despatched from India."

On 27 May, the forces from Basra started to advance northwards. In Operation Regulta, the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade, known as the "Euphrates Brigade," advanced along the Euphrates by boat and by road. In Operation Regatta, the 21st Indian Infantry Brigade, known as the "Tigris Brigade," advanced up the Tigris by boat to Kut

.

On May 30, the 10th Indian Infantry Division's third brigade, 25th Indian Infantry Brigade

under Brigadier Ronald Mountain

, arrived and disembarked at Basra. The 25th Indian Infantry Brigade included 3rd battalion 9th Jat Regiment

, 2nd battalion 11th Royal Sikh Regiment

, and 1st battalion 5th Mahratta Light Infantry

.

In June 1941, additional British forces arrived in Basra from India. On 9 June, the 17th Indian Infantry Brigade

arrived and, on 16 June, the 24th Indian Infantry Brigade

arrived.

after successfully defending Fallujah. Major-General Clark decided to maintain the momentum because he expected that the Iraqis did not appreciate just how small and just how vulnerable his forces actually were. Clark had a total of about 1,450 men to attack at least 20,000 Iraqi defenders. However, Clark did enjoy an advantage in the air

.

, and many members of the "National Defence Government" fled to Persia. After Persia, they went on to Germany

.

On the morning of 31 May, the Mayor of Baghdad and a delegation approached British forces at the Washash Bridge. With the Mayor was Sir Kinahan Cornwallis

, the British Ambassador, who had been confined to the British Embassy in Baghdad for the past four weeks. Terms were quickly reached and an armistice

was signed. The Iraqi armed forces in the vicinity of Baghdad still greatly outnumbered the British and the British decided not to occupy Baghdad immediately. This was done partly to disguise the weakness of British forces outside the city. On 1 June, Abdul Illah

returned to Baghdad as the Regent and the monarchy and a pro-British government were put back in place. On 2 June, Jamil al-Midfai

was named Prime Minister.

. Much of the violence was channelled towards the city's Jewish Quarter

. Some 120 Jewish residents

lost their lives and about 850 were injured before the Iraqi police were ordered to restore order with live ammunition.

At least two British accounts of the conflict praised the efforts of the air and ground forces at RAF Habbaniya. According to Churchill, the landing of the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade at Basra on 18 April was "timely." In his opinion, the landing forced Rashid Ali into premature action. However, Churchill added that the "spirited defence" of Habbaniya by the Flying School was a "prime factor" in British success. Wavell wrote that the "gallant defence" of Habbaniya and the bold advance of Habforce discouraged the Iraqi Army, while the Germans in their turn were prevented from sending further reinforcements by "the desperate resistance of our troops in Crete, and their crippling losses in men and aircraft."

On 18 June, Lieutenant-General Quinan was given command of all British and Commonwealth forces in Iraq. Before this, Iraqforce was more or less limited to the forces landed at and advancing from Basra.

After the Anglo-Iraq War, elements of Iraqforce (known as Iraq Command from 21 June) were used to attack the Vichy French-held Mandate of Syria during the Syria-Lebanon campaign

, which started 8 June and ended 14 July. Iraq Command (known as Persia and Iraq Force from 1 September) was also used to attack Persia during the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Persia

, which took place in August to September 1941. Forward defences against a possible German invasion from the north through the Caucasus

were created in 1942 and the strength of Persia and Iraq Force (Paiforce

) peaked at the equivalent of over 10 brigades before the Russians halted the German threat at the Battle of Stalingrad

. After 1942, Iraq and Persia were used to transit war material

to the Soviet Union

and the British military presence became mainly lines of communication troops.

On 20 June, Churchill told Wavell that he was to be replaced by Auchinleck. Of Wavell, Auchinleck wrote: "In no sense do I wish to infer that I found an unsatisfactory situation on my arrival - far from it. Not only was I greatly impressed by the solid foundations laid by my predecessor, but I was also able the better to appreciate the vastness of the problems with which he had been confronted and the greatness of his achievements, in a command in which some 40 different languages are spoken by the British and Allied Forces."

British forces were to remain in Iraq until 26 October 1947 and the country remained effectively under British control. The British considered the occupation of Iraq necessary to ensure that access to its strategic oil resources be maintained. On 18 August 1942, General Maitland Wilson was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Persia and Iraq Command

. By 15 September, he was headquartered in Baghdad. Wilson's primary task was "to secure at all costs from land and air attack the oil fields and oil installations in Persia and Iraq." His secondary task was "to ensure the transport from the Persian Gulf ports of supplies to Russia to the maximum extent possible without prejudicing [his] primary task."

While Rashid Ali and his supporters were in alliance with the Nazi regime in Germany, the war demonstrated that Iraq's independence was at best conditional on British approval of the government's actions. Rashid Ali and the Mufti of Jerusalem

fled to Persia, then to Turkey

, then to Italy, and finally to Berlin

, Germany, where Ali was welcomed by Hitler as head of the Iraqi government-in-exile.

Rebellion

Rebellion, uprising or insurrection, is a refusal of obedience or order. It may, therefore, be seen as encompassing a range of behaviors aimed at destroying or replacing an established authority such as a government or a head of state...

government of Rashid Ali in the Kingdom of Iraq

Kingdom of Iraq

The Kingdom of Iraq was the sovereign state of Iraq during and after the British Mandate of Mesopotamia. The League of Nations mandate started in 1920. The kingdom began in August 1921 with the coronation of Faisal bin al-Hussein bin Ali al-Hashemi as King Faisal I...

during the Second World War. The war lasted from 2 May to 31 May 1941. The campaign resulted in the re-occupation of Iraq

Iraq

Iraq ; officially the Republic of Iraq is a country in Western Asia spanning most of the northwestern end of the Zagros mountain range, the eastern part of the Syrian Desert and the northern part of the Arabian Desert....

by British armed forces

British Armed Forces

The British Armed Forces are the armed forces of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.Also known as Her Majesty's Armed Forces and sometimes legally the Armed Forces of the Crown, the British Armed Forces encompasses three professional uniformed services, the Royal Navy, the...

and the return to power of the ousted pro-British Regent

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

of Iraq, Prince

Prince

Prince is a general term for a ruler, monarch or member of a monarch's or former monarch's family, and is a hereditary title in the nobility of some European states. The feminine equivalent is a princess...

'Abd al-Ilah

'Abd al-Ilah

Crown Prince Abd al-Ilāh of Hejaz, GCB, GCMG, GCVO was a cousin and brother-in-law of King Ghazi of the Kingdom of Iraq. Abdul Ilah served as Regent for King Faisal II from April 4, 1939 to May 2, 1953, when Faisal came of age...

. The campaign further fuelled nationalist

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

resentment in Iraq toward the British-supported Hashemite

Hashemite

Hashemite is the Latinate version of the , transliteration: Hāšimī, and traditionally refers to those belonging to the Banu Hashim, or "clan of Hashim", a clan within the larger Quraish tribe...

monarchy

Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which the office of head of state is usually held until death or abdication and is often hereditary and includes a royal house. In some cases, the monarch is elected...

.

Background

The Kingdom of IraqKingdom of Iraq

The Kingdom of Iraq was the sovereign state of Iraq during and after the British Mandate of Mesopotamia. The League of Nations mandate started in 1920. The kingdom began in August 1921 with the coronation of Faisal bin al-Hussein bin Ali al-Hashemi as King Faisal I...

(also referred to as Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

) was governed by the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

under a League of Nations mandate

League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administering the territory on behalf of the League...

; the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, until 1932 when Iraq became nominally independent. Before granting independence, the United Kingdom concluded the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty

Anglo-Iraqi Treaty (1930)

The Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930 was a treaty of alliance between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the British-Mandate-controlled administration of the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq. The treaty was between the governments of George V of the United Kingdom and Faisal I of Iraq...

of 1930. This treaty had several conditions, which included permission to establish military bases for British use and provide all facilities for the unrestricted movement of British forces through the country upon request to the Iraqi government. The conditions of the treaty were imposed by the United Kingdom to ensure continued control of Iraq's petroleum

Petroleum

Petroleum or crude oil is a naturally occurring, flammable liquid consisting of a complex mixture of hydrocarbons of various molecular weights and other liquid organic compounds, that are found in geologic formations beneath the Earth's surface. Petroleum is recovered mostly through oil drilling...

resources. Many Iraqis resented these conditions and felt that their country and its monarchy were still under the effective control of the British Government.

However, following 1937, no British troops were left in Iraq and the Iraqi government had become solely responsible for the internal security of the country. In accordance with the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, the British Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

(RAF) had been allowed to retain two bases; RAF Shaibah

RAF Shaibah

RAF Shaibah was an RAF station situated at Shaibah about 13 miles south west of the city of Basrah in Iraq. The area was the site of a battle with Turkish Forces during the Mesopotamian campaign of the First World War....

, near Basra

Basra

Basra is the capital of Basra Governorate, in southern Iraq near Kuwait and Iran. It had an estimated population of two million as of 2009...

, and RAF Habbaniya

RAF Habbaniya

Royal Air Force Station Habbaniya, more commonly known as RAF Habbaniya, was a Royal Air Force station at Habbaniyah, about west of Baghdad in modern day Iraq, on the banks of the Euphrates near Lake Habbaniyah...

, between Ramadi

Ramadi

Ramadi is a city in central Iraq, about west of Baghdad. It is the capital of Al Anbar Governorate.-History:Ramadi is located in a fertile, irrigated, alluvial plain.The Ottoman Empire founded Ramadi in 1869...

and Fallujah

Fallujah

Fallujah is a city in the Iraqi province of Al Anbar, located roughly west of Baghdad on the Euphrates. Fallujah dates from Babylonian times and was host to important Jewish academies for many centuries....

. Air Vice-Marshal

Air Vice-Marshal

Air vice-marshal is a two-star air-officer rank which originated in and continues to be used by the Royal Air Force. The rank is also used by the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence and it is sometimes used as the English translation of an equivalent rank in...

H. G. Smart

Harry George Smart

Harry George Smart, CBE, DFC, AFC, is best known as the commander of RAF Habbaniya during the first part of the Anglo-Iraqi War. Smart was a British officer in the British Army, the Royal Flying Corps, the Royal Australian Air Force, and the Royal Air Force...

was the commander of RAF Habbaniya and Air Officer Commanding

Air Officer Commanding

Air Officer Commanding is a title given in the air forces of Commonwealth nations to an air officer who holds a command appointment. Thus, an air vice marshal might be the AOC 38 Group...

of all RAF forces in Iraq

RAF Iraq Command

Iraq Command was the RAF commanded inter-service command in charge of British forces in Iraq in the 1920s and early 1930s, during the period of the British Mandate of Mesopotamia. It continued as British Forces in Iraq until 1941 when it was replaced by AHQ Iraq...

. The bases in Iraq had a dual role: protecting Britain's petroleum interests and maintaining a link in the air route between Egypt

Kingdom of Egypt

The Kingdom of Egypt was the first modern Egyptian state, lasting from 1922 to 1953. The Kingdom was created in 1922 when the British government unilaterally ended its protectorate over Egypt, in place since 1914. Sultan Fuad I became the first king of the new state...

and India

British Raj

British Raj was the British rule in the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947; The term can also refer to the period of dominion...

. In addition RAF Habbaniya was also a training base and was protected by a small detachment of RAF ground forces

RAF Regiment

The Royal Air Force Regiment is a specialist airfield defence corps founded by Royal Warrant in 1942. After a 32 week trainee gunner course, its members are trained and equipped to prevent a successful enemy attack in the first instance; minimise the damage caused by a successful attack; and...

and locally raised Iraqi troops.

With the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939 the Iraqi Government broke off diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

. However, the United Kingdom wanted the Iraqi Government to take a further step and declare war upon Germany. In March 1940, the nationalist and anti-British Rashid Ali replaced Nuri as-Said

Nuri as-Said

Nuri Pasha al-Said was an Iraqi politician during the British Mandate and during the Kingdom of Iraq. He served in various key cabinet positions, and served seven terms as Prime Minister of Iraq....

. Ali made covert contacts with German representatives in the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

, though he was not yet an openly pro-Axis supporter.

In June 1940, when Fascist Italy joined the war, on the side of Germany, the Iraqi government did not break off diplomatic relations, as they had done with Germany. Thus the Italian Legation in Baghdad became the chief centre for Axis propaganda and for fomenting anti-British feeling. In this they were aided by Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

Haj Mohammed Effendi Amin el-Husseini was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in the British Mandate of Palestine. From as early as 1920, in order to secure the independence of Palestine as an Arab state he actively opposed Zionism, and was implicated as a leader of a violent riot...

, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem is the Sunni Muslim cleric in charge of Jerusalem's Islamic holy places, including the Al-Aqsa Mosque.-Ottoman era:...

. The Grand Mufti had fled from Palestine shortly before the outbreak of war and later received asylum in Baghdad.

In January 1941, there was a political crisis within Iraq and the threat of civil war was looming. Rashid Ali resigned as Prime Minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

of Iraq and was replaced by Taha al-Hashimi

Taha al-Hashimi

Taha al-Hashimi served briefly as prime minister of Iraq for two months, from February 1, 1941, to April 1, 1941. He was appointed prime minister by the regent, 'Abd al-Ilah, following the first ouster of the pro-Axis government of Rashid Ali al-Kaylani during World War II...

. Public opinion started to change in Iraq as the Italians suffered a series of setbacks in the African and Mediterranean theatre.

Coup d'état

On 31 March, the RegentRegent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

of Iraq, Amir Abdul Illah

'Abd al-Ilah

Crown Prince Abd al-Ilāh of Hejaz, GCB, GCMG, GCVO was a cousin and brother-in-law of King Ghazi of the Kingdom of Iraq. Abdul Ilah served as Regent for King Faisal II from April 4, 1939 to May 2, 1953, when Faisal came of age...

, learnt of a plot to arrest him and he fled Baghdad

Baghdad

Baghdad is the capital of Iraq, as well as the coterminous Baghdad Governorate. The population of Baghdad in 2011 is approximately 7,216,040...

for RAF Habbaniya. From Habbaniya he was flown to Basra and given refuge on the gunboat

Insect class gunboat

The Insect class patrol boats were a class of small, but well-armed Royal Navy ships designed for use in shallow rivers or inshore. They were intended for use on the Danube...

HMS Cockchafer

HMS Cockchafer (1915)

HMS Cockchafer was a Royal Navy Insect class gunboat. She was built by Barclay Curle and launched on 17 December 1915 as the 5th Royal Navy ship to carry this name...

.

On 1 April, Rashid Ali, along with four top level Army and Air Force officers; known as the "Golden Square

Golden Square (Iraq)

The Golden Square was a group of four officers of the Iraqi armed forces who played a part in Iraqi politics throughout the 1930s and early 1940s...

," seized power via a coup d'état

Iraq coup (1941)

The 1941 Iraqi coup d'état, also known as the Rashid Ali Al-Gaylani coup or the Golden Square coup was a pro-Nazi military coup in Iraq on April 1, 1941 that overthrew the regime of Regent 'Abd al-Ilah and installed Rashid Ali as Prime Minister...

and Rashid Ali proclaimed himself Chief of the "National Defence Government." The Golden Square deposed Prime Minister Taha al-Hashimi

Taha al-Hashimi

Taha al-Hashimi served briefly as prime minister of Iraq for two months, from February 1, 1941, to April 1, 1941. He was appointed prime minister by the regent, 'Abd al-Ilah, following the first ouster of the pro-Axis government of Rashid Ali al-Kaylani during World War II...

and Rashid Ali once again became Prime Minister of Iraq. Rashid Ali did not move to overthrow the monarchy

Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which the office of head of state is usually held until death or abdication and is often hereditary and includes a royal house. In some cases, the monarch is elected...

and named a new Regent to King Faisal II

Faisal II of Iraq

Faisal II was the last King of Iraq. He reigned from 4 April 1939 until July 1958, when he was killed during the "14 July Revolution" together with several members of his family...

, Sherif Sharaf. The leaders of the "National Defence Government" proceeded to arrest many pro-British citizens and politicians. However, a good number of those sought managed to escape by various means through Amman

Amman

Amman is the capital of Jordan. It is the country's political, cultural and commercial centre and one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. The Greater Amman area has a population of 2,842,629 as of 2010. The population of Amman is expected to jump from 2.8 million to almost...

in Transjordan

Transjordan

The Emirate of Transjordan was a former Ottoman territory in the Southern Levant that was part of the British Mandate of Palestine...

.

The immediate plans of Iraq's new leaders were to refuse further concessions to the United Kingdom, to retain diplomatic links with Fascist Italy, and to expel most prominent pro-British politicians from the country. The plotters of the coup considered the United Kingdom to be weak and believed that its government would negotiate with their new government regardless of its legality. On 17 April, Rashid Ali, on behalf of the "National Defence Government," asked Germany for military assistance in the event of war with the British. Ultimately, Rashid Ali attempted to restrict British rights guaranteed under Article 5 of the 1930 treaty when he insisted that newly arrived British troops be quickly transported through Iraq and to Palestine.

Iraqi forces

Before the war, the United Kingdom provided support and training to the Royal Iraqi Army (RIrA) and the Royal Iraqi Air Force (RIrAF) through a small military mission based in Baghdad. From 1938, Major-General G. G. Waterhouse commanded the British mission.The RIrA was composed of four infantry divisions with some 60,000 men distributed for the most part into four infantry divisions and one mechanized brigade. The 1st

1st Division (Iraq)

The 1st Division, Iraqi Army is a formation of the Army formed c.2005-2007.The 1st Division was originally formed from the battalions of the Iraqi Intervention Force....

and 3rd

3rd Division (Iraq)

The 3rd Division is a formation of the Iraqi Army. It was active by 1941, disbanded along with the rest of the Iraqi Army in 2003, but reactivated by 2005.-History:...

Divisions were stationed near Baghdad. Also based within Baghdad was the Independent Mechanized Brigade, composed of a light tank company, an armoured car company, two battalions of "mechanized" infantry transported in trucks, a "mechanized" machine-gun company, and a "mechanized" artillery brigade. The Iraqi 2nd Division

2nd Division (Iraq)

The 2nd Division is a formation of the Iraqi Army. It is headquartered at Mosul. The 2nd Division is one of the most experienced formations in the Iraqi Army. The division is today engaged in totality in the city of Mosul to assure its security....

was stationed in Kirkuk

Kirkuk

Kirkuk is a city in Iraq and the capital of Kirkuk Governorate.It is located in the Iraqi governorate of Kirkuk, north of the capital, Baghdad...

and the 4th Division

4th Division (Iraq)

The 4th Division is a infantry formation of the Iraqi Army. It was formed before 1941, disbanded in 2003, but reactivated after 2004.It was one of the four original divisions of the Iraqi Army, being active in 1941. At the beginning of the Anglo-Iraqi War it was in Al Diwaniyah on the main rail...

was in Al Diwaniyah

Al Diwaniyah

Al Diwaniyah is the capital city of Iraq's Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate. In 2002, its population was estimated at 440,927. The area around Al Diwaniyah, which is well irrigated from the nearby Euphrates river, is often considered to be one on the most fertile parts of Iraq, and is heavily cultivated...

on the main rail line from Baghdad to Basra. Unlike the modern use of the term "mechanized," in 1941 "mechanized" for the RIrA meant transported by trucks.

In addition to the regular army, the Iraqis fielded some police units and approximately 500 "irregulars

Irregular military

Irregular military refers to any non-standard military. Being defined by exclusion, there is significant variance in what comes under the term. It can refer to the type of military organization, or to the type of tactics used....

" under Arab guerrilla leader Fawzi al-Qawuqji

Fawzi Al-Qawuqji

Fawzi al-Qawuqji was the field commander of the Arab Liberation Army during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War in Palestine, and a rival of the principal Palestinian Arab leader, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini.-Biography:...

. Fawzi al-Qawuqji was a ruthless fighter who did not hesitate to murder or mutilate his prisoners. For the most part, Fawzi al-Qawuqji and his irregulars operated in the area between Rutbah and Ramadi

Ramadi

Ramadi is a city in central Iraq, about west of Baghdad. It is the capital of Al Anbar Governorate.-History:Ramadi is located in a fertile, irrigated, alluvial plain.The Ottoman Empire founded Ramadi in 1869...

before being chased back into Syria.

RAF Hinaidi

Royal Air Force Station Hinaidi, more commonly known as RAF Hinaida, was a British Royal Air Force station near Baghdad in the Kingdom of Iraq...

) or in Mosul

Mosul

Mosul , is a city in northern Iraq and the capital of the Ninawa Governorate, some northwest of Baghdad. The original city stands on the west bank of the Tigris River, opposite the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh on the east bank, but the metropolitan area has now grown to encompass substantial...

. Four squadrons and the Flying Training School were based in Baghdad. Two squadrons with close co-operation and general purpose aircraft were based in Mosul. The Iraqis flew an assortment of aircraft types that included Gladiator

Gloster Gladiator

The Gloster Gladiator was a British-built biplane fighter. It was used by the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy and was exported to a number of other air forces during the late 1930s. It was the RAF's last biplane fighter aircraft and was rendered obsolete by newer monoplane designs even as it...

biplane fighters, Breda 65 fighter bombers, Savoia SM79

Savoia-Marchetti SM.79

The Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero was a three-engined Italian medium bomber with a wood and metal structure. Originally designed as a fast passenger aircraft, this low-wing monoplane, in the years 1937–39, set 26 world records that qualified it for some time as the fastest medium bomber in the...

medium bombers, Northrop/Douglas 8A

Northrop A-17

The Northrop A-17, a development of the Northrop Gamma 2F was a two seat, single engine, monoplane, attack bomber built in 1935 by the Northrop Corporation for the US Army Air Corps.-Development and design:...

fighter bombers, Hawker Nisr

Hawker Hart

The Hawker Hart was a British two-seater biplane light bomber of the Royal Air Force , which had a prominent role during the RAF's inter-war period. The Hart was designed during the 1920s by Sydney Camm and built by Hawker Aircraft...

biplane close co-operation aircraft, Vickers Vincent biplane light bombers, de Havilland Dragon

De Havilland Dragon

|-See also:-References:Bibliography ISBN 0-85177-813-5...

biplane general purpose aircraft, de Havilland Dragonfly

De Havilland Dragonfly

-References:*The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft . London: Orbis Publishing.*Hayes, P & King, B. de Havilland biplane transports. Coulsden: Gatwick Aviation Society ISBN 0 95304132 8...

biplane general purpose aircraft, and Tiger Moth

Tiger moth

Tiger moths are moths of the family Arctiidae.Tiger moth may also refer to:*de Havilland Tiger Moth, an aircraft; an aerobatic and trainer tailwheel biplane*de Havilland DH.71 Tiger Moth, an earlier monoplane produced by de Havilland...

biplane trainers. In addition to the 116 aircraft, the Iraqi Air Force had another 9 aircraft not allocated to specific squadrons and 19 aircraft available in reserve.

The Royal Iraqi Navy (RIrN) had four 100-ton Thornycroft

John I. Thornycroft & Company

John I. Thornycroft & Company Limited, usually known simply as Thornycroft was a British shipbuilding firm started by John Isaac Thornycroft in the 19th century.-History:...

gunboat

Gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.-History:...

s, one pilot vessel, and one minesweeper

Minesweeper (ship)

A minesweeper is a small naval warship designed to counter the threat posed by naval mines. Minesweepers generally detect then neutralize mines in advance of other naval operations.-History:...

. All were armed and all were based in the Shatt al-Arab waterways.

British and commonwealth forces

On 1 April 1941, when the Iraqi coup d'état took place, the British and CommonwealthCommonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, normally referred to as the Commonwealth and formerly known as the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organisation of fifty-four independent member states...

forces available within Iraq were very limited. Air Vice-Marshal Smart commanded the Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

-led inter-service

British Armed Forces

The British Armed Forces are the armed forces of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.Also known as Her Majesty's Armed Forces and sometimes legally the Armed Forces of the Crown, the British Armed Forces encompasses three professional uniformed services, the Royal Navy, the...

command

Command (military formation)

A command in military terminology is an organisational unit that the individual in Military command has responsibility for. A Commander will normally be specifically appointed into the role in order to provide a legal framework for the authority bestowed...

, "British Forces in Iraq

RAF Iraq Command

Iraq Command was the RAF commanded inter-service command in charge of British forces in Iraq in the 1920s and early 1930s, during the period of the British Mandate of Mesopotamia. It continued as British Forces in Iraq until 1941 when it was replaced by AHQ Iraq...

."

Ground forces available to Smart included Number 1 Armoured Car Company RAF

Number 1 Armoured Car Company RAF

The Number 1 Armoured Car Company RAF was a military unit of the Britain's Royal Air Force which played a role in the defense of RAF Habbaniya during World War II.- Creation :...

and six companies of Assyrian Levies

Assyrian Levies

The Iraq Levies was the first Iraqi military forces established by the British in British controlled Iraq. The Iraq Levies were a most noteworthy feature of the Kingdom of Iraq, and especially of northern Iraq during the years of the mandate, and no account of the Assyrians or indeed of Iraq itself...

. The armoured car company comprised 18 ancient Rolls Royce armoured cars

Rolls-Royce Armoured Car