Nansen's Fram expedition

Encyclopedia

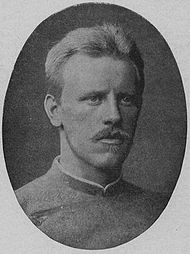

Nansen's Fram expedition, 1893–1896, was an attempt by the Norwegian

explorer Fridtjof Nansen

to reach the geographical North Pole

by harnessing the natural east–west current of the Arctic Ocean

. In the face of much discouragement from other polar explorers Nansen took his ship Fram

to the New Siberian Islands

in the eastern Arctic Ocean, froze her into the pack ice, and waited for the drift to carry her towards the pole. Impatient with the slow speed and erratic character of the drift, after 18 months Nansen and a chosen companion, Hjalmar Johansen

, left the ship with a team of dogs and sledges and made for the pole. They did not reach it, but they achieved a record Farthest North

latitude of 86°13.6'N before a long retreat over ice and water to reach safety in Franz Josef Land

. Meanwhile Fram continued to drift westward, finally emerging in the North Atlantic Ocean.

The idea for the expedition had arisen after items from the American vessel Jeannette

, which had sunk off the north coast of Siberia

in 1881, were discovered three years later off the south-west coast of Greenland

. The wreckage had obviously been carried across the polar ocean, perhaps across the pole itself. Based on this and other debris recovered from the Greenland coast the meteorologist Henrik Mohn

developed a theory of transpolar drift, which led Nansen to believe that a specially designed ship could be frozen in the pack ice and follow the same track as the Jeannette wreckage, thus reaching the vicinity of the pole.

Nansen supervised the construction of a vessel with a rounded hull and other features designed to withstand prolonged pressure from ice. The ship was rarely threatened during her long imprisonment, and emerged unscathed after three years. The scientific observations carried out during this period contributed significantly to the new discipline of oceanography

, which subsequently became the main focus of Nansen's scientific work. Fram's drift and Nansen's sledge journey proved conclusively that there were no significant land masses between the Eurasia

n continents and the North Pole, and confirmed the general character of the north polar region as a deep, ice-covered sea. Although Nansen retired from exploration after this expedition, the methods of travel and survival he developed with Johansen influenced all the polar expeditions, north and south, which followed in the subsequent three decades.

In September 1879 the Jeannette, an ex-Royal Navy

In September 1879 the Jeannette, an ex-Royal Navy

gunboat converted for Arctic exploration and commanded by George Washington De Long, entered the pack ice north of the Bering Strait

. She remained ice-bound for nearly two years, drifting to the area of the New Siberian Islands

, before being crushed and sunk on 13 June 1881. Her crew escaped in boats and made for the Siberian coast; most, including De Long, subsequently perished in the wastelands of the Lena River

delta. Three years later, relics from the Jeannette appeared on the opposite side of the world, in the vicinity of Julianehaab

on the southwest coast of Greenland. These items, frozen into the drifting ice, included clothing bearing crew members' names and documents signed by De Long; they were indisputably genuine.

In a lecture given in 1884 to the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters

Dr. Henrik Mohn

, one of the founders of modern meteorology

, argued that the finding of the Jeannette relics indicated the existence of an ocean current flowing from east to west across the entire Arctic ocean. The Danish governor of Julianehaab, writing of the find, surmised that an expedition frozen into the Siberian sea might, if its ship were to prove strong enough, cross the polar ocean and land in South Greenland. These theories were read with interest by the 23-year-old Fridtjof Nansen, then working as a curator at the Bergen Museum

while completing his doctoral studies. Nansen was already captivated by the frozen north; two years earlier he had experienced a four-month voyage on the sealer

Viking, which had included three weeks trapped in drifting ice. An expert skier, Nansen was making plans to lead the first crossing of the Greenland icecap, an objective delayed by the demands of his academic studies, but triumphantly achieved in 1888–89. Through these years Nansen remembered the east–west Arctic drift theory and its inherent possibilities for further polar exploration, and shortly after his return from Greenland he was ready to announce his plans.

in Oslo

(then called Christiania). After drawing attention to the failures of the many expeditions which had approached the North Pole from the west, he considered the implications of the discovery of the Jeannette items, along with further finds of driftwood and other debris from Siberia or Alaska that had been identified along the Greenland coast. "Putting all this together," Nansen said, "we are driven to the conclusion that a current flows ... from the Siberian Arctic Sea to the east coast of Greenland," probably passing across the Pole. It seemed that the obvious thing to do was "to make our way into the current on that side of the Pole where it flows northward, and by its help to penetrate into those regions which all who have hitherto worked against [the current] have sought in vain to reach."

Nansen's plan required a small, strong and manoeuvrable ship, powered by sail and an engine, capable of carrying fuel and provisions for twelve men for five years. The vessel would follow Jeannette's route to the New Siberian Islands, and in the approximate position of Jeannette's sinking, when ice conditions were right "we shall plough our way in amongst the ice as far as we can." The ship would then drift with the ice towards the pole and eventually reach the sea between Greenland and Spitsbergen. Should the ship founder, a possibility which Nansen thought very unlikely, the party would camp on a floe and allow itself to be carried towards safety. Nansen observed: "If the Jeannette Expedition had had sufficient provisions, and had remained on the ice-floe on which the relics were found, the result would doubtless have been very different from what it was."

When Nansen's plans became public knowledge The New York Times

was enthusiastic, deeming it "highly probable that there is a comparatively short and direct route across the Arctic Ocean by way of the North Pole, and that nature herself has supplied a means of communication across it." However, most experienced polar hands were dismissive. The American explorer Adolphus Greely

called it "an illogical scheme of self-destruction"; his assistant, Lieutenant David Brainerd, called it "one of the most ill-advised schemes ever embarked on", and predicted that it would end in disaster. Sir Allen Young, a veteran of the searches for Sir John Franklin's lost expedition

, did not believe that a ship could be built to withstand the crushing pressure of the ice: "If there is no swell the ice must go through her, whatever material she is made of." Sir Joseph Hooker

, who had sailed south with James Clark Ross

in 1839–43, was of the same opinion, and thought the risks were not worth taking. However, the equally experienced Sir Leopold McClintock

called Nansen's project "the most adventurous programme ever brought under the notice of the Royal Geographical Society". The Swedish philanthropist Oscar Dickson, who had financed Baron Nordenskiöld's conquest of the North-East Passage in 1878–79, was sufficiently impressed to offer to meet Nansen's costs. With Norwegian nationalism on the rise, however, this gesture from their union partner Sweden

provoked hostility in the Norwegian press; Nansen decided to rely solely on Norwegian support, and declined Dickson's proposal.

. The Royal Geographical Society

in London gave £300 ( value about £). Unfortunately, Nansen had underestimated the financing required—the ship alone would cost more than the total at his disposal. A renewed plea to the Storting produced a further NOK 80,000, and a national appeal raised the grand total to NOK 445,000—just under £25,000 ( value about £). According to Nansen's own account, he made up the remaining deficiency from his own resources. However, his biographer Roland Huntford

records that the final deficit of NOK 12,000 was cleared by two wealthy supporters, Axel Heiberg

and an English expatriate, Charles Dick.

, Norway's leading shipbuilder and naval architect. Archer was well-known for a particular hull design that combined seaworthiness with a shallow draught, and had pioneered the design of "double-ended" craft in which the conventional stern was replaced by a point, increasing manoeuvrability. Nansen records that Archer made "plan after plan of the projected ship; one model after another was prepared and abandoned". Finally, agreement was reached on a design, and on 9 June 1891 the two men signed the contract.

Nansen wanted the ship in one year; he was eager to get away before anyone else could adopt his ideas and forestall him. The ship's most significant external feature was the roundness of the hull, designed so that there was nothing upon which the ice could get a grip. Bow, stern and keel were rounded off, and the sides smoothed so that, in Nansen's words, the vessel would "slip like an eel out of the embraces of the ice". To give exceptional strength the hull was sheathed in South American greenheart

, the hardest timber available. The three layers of wood forming the hull provided a combined thickness of between 24 and 28 inches (60–70 cm), increasing to around 48 inches (1.25 metres) at the bow, which was further protected by a protruding iron stem. Added strength was provided by crossbeams and braces throughout the length of the hull.

The ship was rigged as a three-masted schooner

, with a total sail area of 6000 square feet (557.4 m²). Its auxiliary engine of 220 horse-power was capable of speeds up to 7 kn (13.7 km/h; 8.5 mph). However, speed and sailing qualities were secondary to the requirement of providing a safe and warm stronghold for Nansen and his crew during a drift that might extend for several years, so particular attention was paid to the insulation of the living quarters. At around 400 gross register tonnage

, the ship was considerably larger than Nansen had first anticipated, with an overall length of 128 feet (39 m) and a breadth of 36 feet (11 m), a ratio of just over three to one, giving her an unusually stubby appearance. This odd shape was explained by Archer: "A ship that is built with exclusive regard to its suitability for [Nansen's] object must differ essentially from any known vessel." On 6 October 1892, at Archer's yard at Larvik

, the ship was launched by Nansen's wife Eva

after a brief ceremony. The ship was named Fram, meaning "Forward".

, future conqueror of the South Pole, whose mother stopped him from going. The English explorer Frederick Jackson

applied, but Nansen wanted only Norwegians, so Jackson organised his own expedition to Franz Josef Land.

To captain the ship and act as the expedition's second-in-command Nansen chose Otto Sverdrup

, an experienced sailor who had taken part in the Greenland crossing. Theodore Jacobsen, who had experience in the Arctic as skipper of a sloop

, signed on as Fram's mate, and young naval lieutenant Sigurd Scott Hansen took charge of meteorological and magnetic observations. The ship's doctor, and the expedition's botanist, was Henrik Blessing, who graduated in medicine just before Fram's sailing date. Reserve Army lieutenant and dog-driving expert Hjalmar Johansen

was so determined to join the expedition that he agreed to sign on as stoker, the only position by then available. Likewise Adolf Juell, with 20 years' experience at sea as mate and captain, took the post of cook on the Fram voyage. Ivar Mogstad was an official at Gaustad psychiatric hospital

, but his technical abilities as a handyman and mechanic impressed Nansen. The oldest man in the party, at 40, was the chief engineer, Anton Amundsen (no relation of Roald). The second engineer, Lars Pettersen, kept his Swedish nationality from Nansen, and although it was soon discovered by his shipmates, he was allowed to remain with the expedition, the only non-Norwegian in the party. The remaining crew members were Peter Henriksen, Bernhard Nordahl and Bernt Bentzen, the last–named joining the expedition in Tromso at very short notice.

on 1 July (where there was a great banquet in Nansen's honour), Trondheim

on 5 July and Tromsø

, north of the Arctic Circle

, a week later. The last Norwegian port of call was Vardø

, where Fram arrived on 18 July. After the final provisions were taken on board, Nansen, Sverdrup, Hansen and Blessing spent their last hours ashore in a sauna

, being beaten with birch twigs by two young girls.

The first leg of the journey eastward took Fram across the Barents Sea

towards Novaya Zemlya

and then to the North Russian settlement of Khabarova where the first batch of dogs was brought on board. On 3 August Fram weighed anchor and moved cautiously eastward, entering the Kara Sea

the next day. Few ships had sailed the Kara Sea before, and charts were incomplete. On 18 August, in the area of the Yenisei River

delta, an uncharted island was discovered and named Sverdrup Island

after Fram's commander. Fram was now moving towards the Taimyr Peninsula and Cape Chelyuskin

, the most northerly point of the Eurasian continental mass. Heavy ice slowed the expedition's progress, and at the end of August it was held up for four days while the ship's boiler was repaired and cleaned. The crew also experienced the dead water

phenomenon, where a ship's forward progress is impeded by friction caused by a layer of fresh water lying on top of heavier salt water. On 9 September a wide stretch of ice-free water opened up, and next day Fram rounded Cape Chelyuskin—the second ship to do so, after Nordenskiöld's Vega in 1878—and entered the Laptev Sea

.

After being prevented by ice from reaching the mouth of the Olenyok River

, where a second batch of dogs was waiting to be picked up, Fram moved north and east towards the New Siberian Islands. Nansen's hope was to find open water to 80° north latitude and then enter the pack; however, on 20 September ice was sighted just south of 78°. Fram followed the line of the ice before stopping in a small bay beyond the 78° mark. On 28 September it became evident that the ice would not break up, and the dogs were moved from the ship to kennels on the ice. On 5 October the rudder was raised to a position of safety and the ship, in Scott Hansen's words, was "well and truly moored for the winter". The position was 78°49'N, 132°53'E.

After the sun disappeared on 25 October the ship was lit by electric lamps from a wind-powered generator. The crew settled down to a comfortable routine in which boredom and inactivity were the main enemies. Men began to irritate each other, and fights sometimes broke out. Nansen attempted to start a newspaper, but the project soon fizzled out through lack of interest. Small tasks were undertaken and scientific observations maintained, but there was no urgency. Nansen expressed his frustration in his journal: "I feel I must break through this deadness, this inertia, and find some outlet for my energies." And later: "Can't something happen? Could not a hurricane come and tear up this ice?" Only after the turn of the year, in January 1894, did the northerly direction become generally settled. The 80° mark was finally passed on 22 March.

Based on the uncertain direction and slow speed of the drift, Nansen calculated that it might take the ship five years to reach the pole. In January 1894 he had first discussed with both Henriksen and Johansen the possibility of making a sledge journey with the dogs, from Fram to the pole, though they made no immediate plans. Nansen's first attempts to master dog-driving were an embarrassing failure, but he persevered and gradually achieved better results. He also discovered that the normal cross-country skiing speed was the same as that of dogs pulling loaded sledges. Men could travel under their own power, skiing, rather than riding on the sledge, and loads could be correspondingly increased. This, according to biographer and historian Roland Huntford

, amounted to a revolution in polar travel methods.

On 19 May, two days after the celebrations for Norway's National Day

, Fram passed 81°, indicating that the ship's northerly speed was slowly increasing, though it was still barely a mile (1.6 km) a day. With a growing conviction that a sledge journey might be necessary to reach the pole, in September Nansen decreed that everyone would practice skiing for two hours a day. On 16 November he revealed his intention to the crew: he and one companion would leave the ship and start for the pole when the 83° mark was passed. After reaching the pole the pair would make for Franz Josef Land

, and then cross to Spitsbergen where they hoped to find a ship to take them home. Three days later Nansen asked Hjalmar Johansen, the most experienced dog-driver among the crew, to join him on the polar journey.

The crew spent the following months preparing for the forthcoming dash for the pole. They built sledges that would facilitate fast travel over rough terrain and constructed kayaks on the Inuit

model, for use during the expected water crossings. There were endless trials of special clothing and other gear. Violent and prolonged tremors began to shake the ship on 3 January 1895, and two days later the crew disembarked, expecting the ship to be crushed. Instead the pressure lessened, and the crew went back on board and resumed preparations for Nansen's journey. After the excitement it was noted that Fram had drifted beyond Greely's

Farthest North record of 83°24, and on 8 January was at 83°34'N.

had been discovered in 1873 by Julius Payer, and was incompletely mapped. It was, however, apparently the home of countless bears and seals, and Nansen saw it as an excellent food source on his return journey to civilization.

On 14 March, with the ship at 84°4'N, the pair finally began their polar march. This was their third attempt to leave the ship; on 26 February and again on the 28th, damage to sledges had forced them to return after travelling short distances. After these mishaps Nansen thoroughly overhauled his equipment, minimised the travelling stores, recalculated weights and reduced the convoy to three sledges, before giving the order to start again. A supporting party accompanied the pair and shared the first night's camp. The next day, Nansen and Johansen skied on alone.

The pair initially traveled mainly over flat snowfields. Nansen had allowed 50 days to cover the 356 nmi (659.3 km; 409.7 mi) to the pole, requiring an average daily journey of seven nautical miles (13 km; 8.1 mi). On 22 March a sextant

observation showed that the pair had travelled 65 nmi (120.4 km; 74.8 mi) towards the pole at a daily average of over nine nautical miles (17 km; 10 mi). This had been achieved despite very low temperatures, typically around -40 F, and small scale mishaps including the loss of the sledgemeter that recorded mileage. However, as the surfaces became uneven and made skiing more difficult, their speeds slowed. A sextant reading on 29 March of 85°56'N indicated that a week's travel had brought them 47 nmi (87 km; 54.1 mi) nearer to the pole, but also showed that their average daily distances were falling. More worryingly, a theodolite

reading that day suggested that they were at only 85°15'N, and they had no means of knowing which of the readings was correct. They realised that they were fighting a southerly drift, and that distances travelled did not necessarily equate to northerly progression. Johansen's diary indicated his failing spirits: "My fingers are all destroyed. All mittens are frozen stiff ... It is becoming worse and worse ... God knows what will happen to us".

On 3 April, after days of difficult travel, Nansen privately began to wonder if the pole might not, after all, be out of reach. Unless the surface improved, their food would not last them to the pole and then on to Franz Josef Land. The next day they calculated their position at a disappointing 86°3'; Nansen confided in his diary that: "I have become more and more convinced we ought to turn before time." After making camp on 7 April Nansen scouted ahead on snowshoes looking for a path forward, but saw only "a veritable chaos of iceblocks stretching as far as the horizon". He decided that they would go no further north, and would head for Cape Fligely in Franz Josef Land. Nansen recorded the latitude of their final northerly camp as 86°13.6'N, almost three degrees beyond Greely's previous Farthest North mark.

The direction of the drift became northerly, hampering the pair's progress. By 18 April, after 11 days' travel from Farthest North, they had only made 40 nmi (74.1 km; 46 mi) to the south. They now travelled over much more broken terrain with wide open leads of water. On about 20 April they were cheered by the sight of a large piece of driftwood stuck in a floe, the first object from the outside world they had seen since Fram had entered the ice. Johansen carved his and Nansen's initials, with the latitude and date. A day or two later they spotted the tracks of an Arctic fox

, the first trace of a living creature other than their dogs since leaving Fram. Other tracks soon appeared, and Nansen began to believe that land might be near.

The latitude calculated on 9 May, 84°3'N, was disappointing—Nansen had hoped they were further south. However, as May progressed they began to see bear tracks, and by the end of the month seals, gulls and whales were plentiful. By Nansen's calculations, they had reached 82°21'N on 31 May, placing them only 50 nmi (92.6 km; 57.5 mi) from Cape Fligely if his longitude estimate was accurate. In the warmer weather the ice began to break up, making travel more difficult. Since 24 April dogs had been killed at regular intervals to feed the others, and by the beginning of June only seven of the original 28 remained. On 21 June the pair jettisoned all surplus equipment and supplies, planning to travel light and live off the now plentiful supplies of seal and birds. After a day's travel in this manner they decided to rest on a floe, waterproof the kayaks and build up their own strength for the next stage of their journey. They remained camped on the floe for a whole month.

On 23 July, the day after leaving the camp, Nansen had the first indisputable glimpse of land. He wrote: "At last the marvel has come to pass—land, land, and after we had almost given up our belief in it!" In the succeeding days the pair struggled towards this land, which seemingly grew no nearer, although by the end of July they could hear the distant sound of breaking surf. On 4 August they survived a polar bear attack; two days later they reached the edge of the ice, and only water lay between them and the land. On 6 August they shot the last two Samoyed dogs, a male named Kaifas and a female named Suggen, converted the kayaks into a catamaran by lashing sledges and skis across them, and raised a sail.

Nansen called this first land "Hvidtenland" (English: "White Island). After making camp on an ice foot they ascended a slope and looked about them. It was apparent that they were in an archipelago, but what they could see bore no relation to their incomplete map of Franz Josef Land. They could only continue south in the hopes of finding a geographical feature they could pinpoint with certainty. On 16 August Nansen tentatively identified a headland as Cape Felder, marked on Payer's maps as on the western coast of Franz Josef Land. Nansen's objective was now to reach a hut and supplies that had been left by an earlier expedition at a location known as Eira Harbour, at the southern end of the islands. However, contrary winds and loose ice made further progress in the kayak hazardous, and on 28 August Nansen decided that, with another polar winter drawing near, they should stay where they were and await the following spring.

At Christmas the pair celebrated with chocolate and bread from their sledging rations. On New Year's Eve Johansen recorded that Nansen finally adopted the familiar form of address, having until then maintained formalities ("Mr Johansen", "Professor Nansen") throughout the journey. In the New Year they fashioned themselves simple outer clothing—smocks and trousers—from a discarded sleeping bag, in readiness for the resumption of their journey when the weather grew warmer. On 19 May 1896, after weeks of preparation, they were ready. Nansen left a note in the hut to inform a possible finder: "We are going south west, along the land, to cross over to Spitsbergen".

For more than two weeks they followed the shoreline southwards. Nothing they saw seemed to fit with their rudimentary map of Franz Josef Land, and Nansen speculated whether they were in uncharted lands between Franz Josef Land and Spitsbergen. On 4 June a change in conditions allowed them to launch their kayaks for the first time since leaving their winter quarters. A week later, Nansen was forced to dive into the icy waters to rescue the kayaks which, still tied together, had drifted away after being carelessly moored. He managed to reach the craft and, with a last effort, to haul himself aboard. Despite his frozen condition he shot and retrieved two guillemot

s as he paddled the catamaran back.

On 13 June walruses attacked and damaged the kayaks, causing another stop for repairs. On 17 June, as they prepared to leave again, Nansen thought he heard a dog bark and went to investigate. He then heard voices, and a few minutes later encountered a human being. It was Frederick Jackson, who had organised his own expedition to Franz Josef Land after being rejected by Nansen, and had based his headquarters at Cape Flora on Northbrook Island

, the southernmost island of the archipelago. Jackson's own account records that his first reaction to this sudden meeting was to assume the figure to be a shipwrecked sailor, perhaps from the expedition's supply ship Windward which was due to call that summer. As he approached, Jackson saw "a tall man, wearing a soft felt hat, loosely made, voluminous clothes and long shaggy hair and beard, all reeking with black grease". After a moment's awkward hesitation, Jackson recognised his visitor: "You are Nansen, aren't you?", and received the reply "Yes, I am Nansen."

Johansen was rescued, and the pair taken to the base at Cape Flora, where they posed for photographs (in one instance re-enacting the Jackson–Nansen meeting) before taking baths and haircuts. Both men seemed in good health, despite their ordeal; Nansen had put on 21 pounds (9.5 kg) in weight since the start of the expedition, and Johansen 13 pounds (5.9 kg). In honour of his rescuer, Nansen named the island where he had wintered "Frederick Jackson Island". For the next six weeks Nansen had little to do but await the arrival of Windward, worrying that he might have to spend the winter at Cape Flora, and sometimes regretting that he and Johansen had not pressed on to Spitsbergen. Johansen noted in his journal that Nansen had changed from the overbearing personality of the Fram days, and was now subdued and polite, adamant that he would never undertake such a journey again. On 26 July Windward finally arrived; on 7 August, with Nansen and Johansen aboard, she sailed south and on 13 August reached Vardø. A batch of telegrams was sent, informing the world of Nansen's safe return.

Sverdrup's main task now was to keep his crew busy. He ordered a thorough spring cleaning

, and set a party to chip away some of the surrounding ice which was threatening to destabilise the ship. Although there was no immediate danger to Fram, Sverdrup oversaw the repair and overhaul of sledges, and the organisation of provisions should it after all be necessary to abandon ship and march to land. With the arrival of warmer weather as the 1895 summer approached, Sverdrup resumed daily ski practice. Amid these activities a full programme of meteorological, magnetic and oceanographic activities continued under Scott Hansen; Fram had become a moving oceanographic, meteorological and biological laboratory.

As the drift proceeded the ocean became deeper; soundings

gave successive depths of 6000 feet (1,828.8 m), 9000 feet (2,743.2 m) and 2000 feet (609.6 m), a progression which indicated that no undiscovered land mass was nearby. On 15 November 1895 Fram reached 85°55'N, only 19 nmi (35.2 km; 21.9 mi) below Nansen's Farthest North mark. From this point on, the drift was generally to the south and west, although progress was for long periods almost imperceptible. Inactivity and boredom led to increased drinking; Scott Hansen recorded that Christmas and New Year passed "with the usual hot punch and consequent hangover", and wrote that he was "getting more and more disgusted with drunkenness". By mid-March 1896, the position was 84°25'N, 12°50'E, placing the ship north of Spitsbergen. On 13 June a lead opened and, for the first time in nearly three years, Fram became a living ship. It was a further two months, on 13 August 1896, before she found open water and, with a blast from her cannon, left the ice behind. She had emerged from the ice just north and west of Spitsbergen, close to Nansen's original prediction, proving him right and his detractors wrong. Later that same day a ship was sighted—Søstrone, a seal hunter

from Tromsø. Sverdrup rowed across for news, and learned that nothing had been heard from Nansen. Fram called briefly at Spitsbergen, where the Swedish explorer-engineer Salomon Andrée was preparing for the balloon flight that he hoped would take him to the pole. After a short time ashore, Sverdrup and his crew began the trip south to Norway.

, in Siberia, from a supposed Nansen agent, claiming that Nansen had reached the pole and found land there. Charles P. Daly of the American Geographical Society

called this "startling news" and, "if true, the most important discovery that has been made in ages."

Experts were sceptical of all such reports, and Nansen's arrival in Vardø quickly put paid to them. In Vardø, he and Johansen were greeted by Professor Mohn, the originator of the polar drift theory, who was in the town by chance. The pair waited for the weekly mail steamer to take them south, and on 18 August arrived in Hammerfest

to an enthusiastic reception. The lack of news about Fram was preying on Nansen's mind; however, on 20 August he received news that Sverdrup had brought the ship to the tiny port of Skjervøy

, south of Hammerfest, and was now continuing with her to Tromsø. The next day, Nansen and Johansen sailed into Tromsø and joined their comrades in an emotional reunion.

After days of celebration and recuperation the ship left Tromsø on 26 August. The voyage south was a triumphal progress, with receptions at every port. Fram finally arrived in Christiania on 9 September, escorted into the harbour by a squadron of warships and welcomed by thousands—the largest crowds the city had ever seen, according to Huntford. Nansen and his crew were received by King Oscar; on the way to the reception they passed through a triumphal arch formed by 200 gymnasts. Nansen and his family stayed at the palace as special guests of the king; by contrast, Johansen remained in the background, largely overlooked, and writing that "reality, after all, is not so wonderful as it appeared to me in the midst of our hard life."

and Sami

expertise in his methods of travel, had ensured that his expedition was completed without a single casualty or major mishap.

Although it did not achieve the objective of reaching the North Pole, the expedition made major geographical and scientific discoveries. Sir Clements Markham

, president of Britain's Royal Geographical Society

, declared that the expedition had resolved "the whole problem of Arctic geography". It was now established that the North Pole was located not on land, nor on a permanent ice sheet, but on shifting, unpredictable pack ice. The Arctic Ocean was a deep basin, with no significant land masses north of the Eurasian continent—any hidden expanse of land would have blocked the free movement of ice. Nansen had proved the polar drift theory; furthermore, he had noted the presence of a Coriolis force

driving the ice to the right of the wind direction, due to the effect of the Earth's rotation. This discovery would be developed by Nansen's pupil, Vagn Walfrid Ekman

, who later became the leading oceanographer of his age. From its programme of scientific observation the expedition provided the first detailed oceanographic information from the area; in due course the scientific data gathered during the Fram voyage would run to six published volumes.

Throughout the expedition Nansen continued to experiment with equipment and techniques, altering the designs of skis and sledges and investigating types of clothing, tents and cooking apparatus, thereby revolutionising methods of Arctic travel. In the era of polar exploration which followed his return, explorers routinely sought Nansen's advice as to methods and equipment—although sometimes they chose not to follow it, usually to their cost. According to Huntford, the South Pole heroes Amundsen, Scott

and Ernest Shackleton

were all Nansen's acolytes.

Nansen's status was never seriously challenged, although he did not escape criticism. American explorer Robert Peary

wondered why Nansen had not returned to the ship when his polar dash was thwarted after a mere three weeks away. "Was he ashamed to go back after so short an absence, or had there been a row ... or did he go off for Franz Josef Land from sensational motives or business reasons?" Adolphus Greely, who had initially dismissed the entire expedition as infeasible, admitted that he had been proved wrong but nevertheless drew attention to "the single blemish"—Nansen's decision to leave his comrades hundreds of miles from land. "It passes comprehension", Greely wrote, "how Nansen could have thus deviated from the most sacred duty devolving on the commander of a naval expedition." Nansen's reputation nevertheless survived; a hundred years after the expedition the British explorer Wally Herbert

called the Fram voyage "one of the most inspiring examples of courageous intelligence in the history of exploration".

The Fram voyage was Nansen's final expedition. He was appointed to a research professorship at the University of Christiania in 1897, and to a full professorship in oceanography in 1908. He became independently wealthy as a result of the publication of his expedition account; in his later career he served the newly independent kingdom of Norway in different capacities, and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

for 1922, in recognition of his work on behalf of refugees. Hjalmar Johansen never settled back into normal life. After years of drifting, debt and drunkenness he was given the opportunity, through Nansen's influence, to join Roald Amundsen's South Pole expedition in 1910. Johansen quarreled violently with Amundsen at the expedition's base camp, and was omitted from the South Pole party. He committed suicide within a year of his return from Antarctica. Otto Sverdrup remained as captain of Fram, and in 1898 took the ship, with a new crew, to the Canadian Arctic for four years' exploration. In later years Sverdrup helped to raise funds that enabled the ship to be restored and housed in a permanent museum. He died in November 1930, seven months after Nansen's death.

Nansen's farthest north record lasted for just over five years. On 24 April 1900 a party of three from an Italian expedition led by the Duke of the Abruzzi

reached 86°34'N, having left Franz Josef Land with dogs and sledges on 11 March. The party barely made it back; one of their support groups of three men vanished entirely.

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

explorer Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In his youth a champion skier and ice skater, he led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, and won international fame after reaching a...

to reach the geographical North Pole

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is, subject to the caveats explained below, defined as the point in the northern hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface...

by harnessing the natural east–west current of the Arctic Ocean

Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean, located in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Arctic north polar region, is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceanic divisions...

. In the face of much discouragement from other polar explorers Nansen took his ship Fram

Fram

Fram is a ship that was used in expeditions of the Arctic and Antarctic regions by the Norwegian explorers Fridtjof Nansen, Otto Sverdrup, Oscar Wisting, and Roald Amundsen between 1893 and 1912...

to the New Siberian Islands

New Siberian Islands

The New Siberian Islands are an archipelago, located to the North of the East Siberian coast between the Laptev Sea and the East Siberian Sea north of the Sakha Republic....

in the eastern Arctic Ocean, froze her into the pack ice, and waited for the drift to carry her towards the pole. Impatient with the slow speed and erratic character of the drift, after 18 months Nansen and a chosen companion, Hjalmar Johansen

Hjalmar Johansen

Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen was a polar explorer from Norway. He shipped out with Fridtjof Nansen's Fram expedition in 1893–1896, and accompanied Nansen to notch a new Farthest North record near the North Pole on what was then the frozen Arctic Ocean...

, left the ship with a team of dogs and sledges and made for the pole. They did not reach it, but they achieved a record Farthest North

Farthest North

Farthest North describes the most northerly latitude reached by explorers before the conquest of the North Pole rendered the expression obsolete...

latitude of 86°13.6'N before a long retreat over ice and water to reach safety in Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land, Franz Joseph Land, or Francis Joseph's Land is an archipelago located in the far north of Russia. It is found in the Arctic Ocean north of Novaya Zemlya and east of Svalbard, and is administered by Arkhangelsk Oblast. Franz Josef Land consists of 191 ice-covered islands with a...

. Meanwhile Fram continued to drift westward, finally emerging in the North Atlantic Ocean.

The idea for the expedition had arisen after items from the American vessel Jeannette

USS Jeannette (1878)

The first USS Jeannette was originally HMS Pandora, a Philomel-class gunvessel of the Royal Navy, and was purchased in 1875 by Sir Allen Young for his arctic voyages in 1875-1876. The ship was purchased in 1878 by James Gordon Bennett, Jr., owner of the New York Herald; and renamed Jeannette...

, which had sunk off the north coast of Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

in 1881, were discovered three years later off the south-west coast of Greenland

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

. The wreckage had obviously been carried across the polar ocean, perhaps across the pole itself. Based on this and other debris recovered from the Greenland coast the meteorologist Henrik Mohn

Henrik Mohn

Henrik Mohn was a Norwegian astronomer and meteorologist. Although he enrolled in theology studies after finishing school, he is credited with founding meteorological research in Norway, being a professor at the Royal Frederick University and director of the Norwegian Meteorological Institute from...

developed a theory of transpolar drift, which led Nansen to believe that a specially designed ship could be frozen in the pack ice and follow the same track as the Jeannette wreckage, thus reaching the vicinity of the pole.

Nansen supervised the construction of a vessel with a rounded hull and other features designed to withstand prolonged pressure from ice. The ship was rarely threatened during her long imprisonment, and emerged unscathed after three years. The scientific observations carried out during this period contributed significantly to the new discipline of oceanography

Oceanography

Oceanography , also called oceanology or marine science, is the branch of Earth science that studies the ocean...

, which subsequently became the main focus of Nansen's scientific work. Fram's drift and Nansen's sledge journey proved conclusively that there were no significant land masses between the Eurasia

Eurasia

Eurasia is a continent or supercontinent comprising the traditional continents of Europe and Asia ; covering about 52,990,000 km2 or about 10.6% of the Earth's surface located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres...

n continents and the North Pole, and confirmed the general character of the north polar region as a deep, ice-covered sea. Although Nansen retired from exploration after this expedition, the methods of travel and survival he developed with Johansen influenced all the polar expeditions, north and south, which followed in the subsequent three decades.

Background

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

gunboat converted for Arctic exploration and commanded by George Washington De Long, entered the pack ice north of the Bering Strait

Bering Strait

The Bering Strait , known to natives as Imakpik, is a sea strait between Cape Dezhnev, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia, the easternmost point of the Asian continent and Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, USA, the westernmost point of the North American continent, with latitude of about 65°40'N,...

. She remained ice-bound for nearly two years, drifting to the area of the New Siberian Islands

New Siberian Islands

The New Siberian Islands are an archipelago, located to the North of the East Siberian coast between the Laptev Sea and the East Siberian Sea north of the Sakha Republic....

, before being crushed and sunk on 13 June 1881. Her crew escaped in boats and made for the Siberian coast; most, including De Long, subsequently perished in the wastelands of the Lena River

Lena River

The Lena is the easternmost of the three great Siberian rivers that flow into the Arctic Ocean . It is the 11th longest river in the world and has the 9th largest watershed...

delta. Three years later, relics from the Jeannette appeared on the opposite side of the world, in the vicinity of Julianehaab

Qaqortoq

Qaqortoq is a town in the Kujalleq municipality in southern Greenland. With a population of 3,230 as of 2011, it is the most populous town in southern Greenland, and the fourth-largest town in the country. The name is western Greenlandic and means "[the] white [one]".- History :The area around...

on the southwest coast of Greenland. These items, frozen into the drifting ice, included clothing bearing crew members' names and documents signed by De Long; they were indisputably genuine.

In a lecture given in 1884 to the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters

Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters

The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters is a learned society based in Oslo, Norway.-History:The University of Oslo was established in 1811. The idea of a learned society in Christiania surfaced for the first time in 1841. The city of Throndhjem had no university, but had a learned...

Dr. Henrik Mohn

Henrik Mohn

Henrik Mohn was a Norwegian astronomer and meteorologist. Although he enrolled in theology studies after finishing school, he is credited with founding meteorological research in Norway, being a professor at the Royal Frederick University and director of the Norwegian Meteorological Institute from...

, one of the founders of modern meteorology

Meteorology

Meteorology is the interdisciplinary scientific study of the atmosphere. Studies in the field stretch back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not occur until the 18th century. The 19th century saw breakthroughs occur after observing networks developed across several countries...

, argued that the finding of the Jeannette relics indicated the existence of an ocean current flowing from east to west across the entire Arctic ocean. The Danish governor of Julianehaab, writing of the find, surmised that an expedition frozen into the Siberian sea might, if its ship were to prove strong enough, cross the polar ocean and land in South Greenland. These theories were read with interest by the 23-year-old Fridtjof Nansen, then working as a curator at the Bergen Museum

Bergen Museum

The Bergen Museum is a university museum in Bergen, Norway. Founded in 1825 with the intent of building large collections in the fields of culture and natural history, it became the grounds for most of the academic activity in the city, a tradition which has prevailed since the museum became part...

while completing his doctoral studies. Nansen was already captivated by the frozen north; two years earlier he had experienced a four-month voyage on the sealer

Seal hunting

Seal hunting, or sealing, is the personal or commercial hunting of seals. The hunt is currently practiced in five countries: Canada, where most of the world's seal hunting takes place, Namibia, the Danish region of Greenland, Norway and Russia...

Viking, which had included three weeks trapped in drifting ice. An expert skier, Nansen was making plans to lead the first crossing of the Greenland icecap, an objective delayed by the demands of his academic studies, but triumphantly achieved in 1888–89. Through these years Nansen remembered the east–west Arctic drift theory and its inherent possibilities for further polar exploration, and shortly after his return from Greenland he was ready to announce his plans.

Plan

In February 1890 Nansen addressed a meeting of the Norwegian Geographical SocietyNorwegian Geographical Society

The Norwegian Geographical Society is a Norwegian learned society founded in 1889. Among the initiators was geologist Hans Henrik Reusch, who chaired the society from 1898 to 1903, and again from 1907 to 1909, and was also an honorary member...

in Oslo

Oslo

Oslo is a municipality, as well as the capital and most populous city in Norway. As a municipality , it was established on 1 January 1838. Founded around 1048 by King Harald III of Norway, the city was largely destroyed by fire in 1624. The city was moved under the reign of Denmark–Norway's King...

(then called Christiania). After drawing attention to the failures of the many expeditions which had approached the North Pole from the west, he considered the implications of the discovery of the Jeannette items, along with further finds of driftwood and other debris from Siberia or Alaska that had been identified along the Greenland coast. "Putting all this together," Nansen said, "we are driven to the conclusion that a current flows ... from the Siberian Arctic Sea to the east coast of Greenland," probably passing across the Pole. It seemed that the obvious thing to do was "to make our way into the current on that side of the Pole where it flows northward, and by its help to penetrate into those regions which all who have hitherto worked against [the current] have sought in vain to reach."

Nansen's plan required a small, strong and manoeuvrable ship, powered by sail and an engine, capable of carrying fuel and provisions for twelve men for five years. The vessel would follow Jeannette's route to the New Siberian Islands, and in the approximate position of Jeannette's sinking, when ice conditions were right "we shall plough our way in amongst the ice as far as we can." The ship would then drift with the ice towards the pole and eventually reach the sea between Greenland and Spitsbergen. Should the ship founder, a possibility which Nansen thought very unlikely, the party would camp on a floe and allow itself to be carried towards safety. Nansen observed: "If the Jeannette Expedition had had sufficient provisions, and had remained on the ice-floe on which the relics were found, the result would doubtless have been very different from what it was."

When Nansen's plans became public knowledge The New York Times

The New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

was enthusiastic, deeming it "highly probable that there is a comparatively short and direct route across the Arctic Ocean by way of the North Pole, and that nature herself has supplied a means of communication across it." However, most experienced polar hands were dismissive. The American explorer Adolphus Greely

Adolphus Greely

Adolphus Washington Greely , was an American Polar explorer, a United States Army officer and a recipient of the Medal of Honor.-Early military career:...

called it "an illogical scheme of self-destruction"; his assistant, Lieutenant David Brainerd, called it "one of the most ill-advised schemes ever embarked on", and predicted that it would end in disaster. Sir Allen Young, a veteran of the searches for Sir John Franklin's lost expedition

Franklin's lost expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a doomed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845. A Royal Navy officer and experienced explorer, Franklin had served on three previous Arctic expeditions, the latter two as commanding officer...

, did not believe that a ship could be built to withstand the crushing pressure of the ice: "If there is no swell the ice must go through her, whatever material she is made of." Sir Joseph Hooker

Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker OM, GCSI, CB, MD, FRS was one of the greatest British botanists and explorers of the 19th century. Hooker was a founder of geographical botany, and Charles Darwin's closest friend...

, who had sailed south with James Clark Ross

James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross , was a British naval officer and explorer. He explored the Arctic with his uncle Sir John Ross and Sir William Parry, and later led his own expedition to Antarctica.-Arctic explorer:...

in 1839–43, was of the same opinion, and thought the risks were not worth taking. However, the equally experienced Sir Leopold McClintock

Francis Leopold McClintock

Admiral Sir Francis Leopold McClintock or Francis Leopold M'Clintock KCB, FRS was an Irish explorer in the British Royal Navy who is known for his discoveries in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.-Biography:...

called Nansen's project "the most adventurous programme ever brought under the notice of the Royal Geographical Society". The Swedish philanthropist Oscar Dickson, who had financed Baron Nordenskiöld's conquest of the North-East Passage in 1878–79, was sufficiently impressed to offer to meet Nansen's costs. With Norwegian nationalism on the rise, however, this gesture from their union partner Sweden

Union between Sweden and Norway

The Union between Sweden and Norway , officially the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, consisted of present-day Sweden and Norway between 1814 and 1905, when they were united under one monarch in a personal union....

provoked hostility in the Norwegian press; Nansen decided to rely solely on Norwegian support, and declined Dickson's proposal.

Finance

Nansen's original estimate for the total cost of the expedition was , then worth around £16,875 ( value about £). After giving a passionate speech before the Parliament of Norway, Nansen was awarded a grant of NOK 200,000; the balance was raised from private contributions which included 20,000 kroner from King Oscar II of Norway and SwedenOscar II of Sweden

Oscar II , baptised Oscar Fredrik was King of Sweden from 1872 until his death and King of Norway from 1872 until 1905. The third son of King Oscar I of Sweden and Josephine of Leuchtenberg, he was a descendant of Gustav I of Sweden through his mother.-Early life:At his birth in Stockholm, Oscar...

. The Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

in London gave £300 ( value about £). Unfortunately, Nansen had underestimated the financing required—the ship alone would cost more than the total at his disposal. A renewed plea to the Storting produced a further NOK 80,000, and a national appeal raised the grand total to NOK 445,000—just under £25,000 ( value about £). According to Nansen's own account, he made up the remaining deficiency from his own resources. However, his biographer Roland Huntford

Roland Huntford

Roland Huntford is an author, principally of biographies of Polar explorers. He lives in Cambridge, and was formerly Scandinavian correspondent of The Observer, also acting as their winter sports correspondent...

records that the final deficit of NOK 12,000 was cleared by two wealthy supporters, Axel Heiberg

Axel Heiberg

Axel Heiberg was a Norwegian diplomat, financier and patron.He was married to Ragnhild Meyer, daughter of Thorvald Meyer; they had one child, Ingeborg...

and an English expatriate, Charles Dick.

Ship

To design and build his ship Nansen chose Colin ArcherColin Archer

Colin Archer was a Norwegian naval architect and shipbuilder from Larvik, Norway. His parents emigrated from Scotland to Norway in 1825....

, Norway's leading shipbuilder and naval architect. Archer was well-known for a particular hull design that combined seaworthiness with a shallow draught, and had pioneered the design of "double-ended" craft in which the conventional stern was replaced by a point, increasing manoeuvrability. Nansen records that Archer made "plan after plan of the projected ship; one model after another was prepared and abandoned". Finally, agreement was reached on a design, and on 9 June 1891 the two men signed the contract.

Nansen wanted the ship in one year; he was eager to get away before anyone else could adopt his ideas and forestall him. The ship's most significant external feature was the roundness of the hull, designed so that there was nothing upon which the ice could get a grip. Bow, stern and keel were rounded off, and the sides smoothed so that, in Nansen's words, the vessel would "slip like an eel out of the embraces of the ice". To give exceptional strength the hull was sheathed in South American greenheart

Chlorocardium

Chlorocardium rodiei is a member of the family Lauraceae. It is one of two species in the genus Chlorocardium, and was formerly classified in either of the genera Nectandra or Ocotea, as Nectandra rodiei or Ocotea rodiei. Other local names include sipiri, bebeeru and bibiru...

, the hardest timber available. The three layers of wood forming the hull provided a combined thickness of between 24 and 28 inches (60–70 cm), increasing to around 48 inches (1.25 metres) at the bow, which was further protected by a protruding iron stem. Added strength was provided by crossbeams and braces throughout the length of the hull.

The ship was rigged as a three-masted schooner

Schooner

A schooner is a type of sailing vessel characterized by the use of fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts with the forward mast being no taller than the rear masts....

, with a total sail area of 6000 square feet (557.4 m²). Its auxiliary engine of 220 horse-power was capable of speeds up to 7 kn (13.7 km/h; 8.5 mph). However, speed and sailing qualities were secondary to the requirement of providing a safe and warm stronghold for Nansen and his crew during a drift that might extend for several years, so particular attention was paid to the insulation of the living quarters. At around 400 gross register tonnage

Gross Register Tonnage

Gross register tonnage a ship's total internal volume expressed in "register tons", one of which equals to a volume of . It is calculated from the total permanently enclosed capacity of the vessel. The ship's net register tonnage is obtained by reducing the volume of non-revenue-earning spaces i.e...

, the ship was considerably larger than Nansen had first anticipated, with an overall length of 128 feet (39 m) and a breadth of 36 feet (11 m), a ratio of just over three to one, giving her an unusually stubby appearance. This odd shape was explained by Archer: "A ship that is built with exclusive regard to its suitability for [Nansen's] object must differ essentially from any known vessel." On 6 October 1892, at Archer's yard at Larvik

Larvik

is a city and municipality in Vestfold county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Larvik. Larvik kommune - has about 41 364 inhabitants and covers 530 km2....

, the ship was launched by Nansen's wife Eva

Eva Nansen

Eva Helene Nansen was a celebrated Norwegian mezzosoprano singer. She was also a pioneer of women's skiing.-Personal life:...

after a brief ceremony. The ship was named Fram, meaning "Forward".

Crew

For his Greenland expedition of 1888–89 Nansen had departed from the traditional dependence on large-scale personnel, ships and backup, relying instead on a small well-trained group. Using the same principle for the Fram voyage, Nansen chose a party of just twelve from the thousands of applications that poured in from all over the world. One applicant was the 20-year-old Roald AmundsenRoald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He led the first Antarctic expedition to reach the South Pole between 1910 and 1912 and he was the first person to reach both the North and South Poles. He is also known as the first to traverse the Northwest Passage....

, future conqueror of the South Pole, whose mother stopped him from going. The English explorer Frederick Jackson

Frederick George Jackson

Frederick George Jackson , British Arctic explorer, was educated at Denstone College and Edinburgh University.-Biography:...

applied, but Nansen wanted only Norwegians, so Jackson organised his own expedition to Franz Josef Land.

To captain the ship and act as the expedition's second-in-command Nansen chose Otto Sverdrup

Otto Sverdrup

Otto Neumann Knoph Sverdrup was a Norwegian sailor and Arctic explorer.-Early and personal life:...

, an experienced sailor who had taken part in the Greenland crossing. Theodore Jacobsen, who had experience in the Arctic as skipper of a sloop

Sloop

A sloop is a sail boat with a fore-and-aft rig and a single mast farther forward than the mast of a cutter....

, signed on as Fram's mate, and young naval lieutenant Sigurd Scott Hansen took charge of meteorological and magnetic observations. The ship's doctor, and the expedition's botanist, was Henrik Blessing, who graduated in medicine just before Fram's sailing date. Reserve Army lieutenant and dog-driving expert Hjalmar Johansen

Hjalmar Johansen

Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen was a polar explorer from Norway. He shipped out with Fridtjof Nansen's Fram expedition in 1893–1896, and accompanied Nansen to notch a new Farthest North record near the North Pole on what was then the frozen Arctic Ocean...

was so determined to join the expedition that he agreed to sign on as stoker, the only position by then available. Likewise Adolf Juell, with 20 years' experience at sea as mate and captain, took the post of cook on the Fram voyage. Ivar Mogstad was an official at Gaustad psychiatric hospital

Gaustad Hospital

Gaustad Hospital is a psychiatric hospital located at Gaustad in Oslo, Norway. Founded in 1855, it is part of Aker University Hospital. Since 1 January 2009, Aker University Hospital has been part of Oslo University Hospital, a subsidiary of the Southern and Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority....

, but his technical abilities as a handyman and mechanic impressed Nansen. The oldest man in the party, at 40, was the chief engineer, Anton Amundsen (no relation of Roald). The second engineer, Lars Pettersen, kept his Swedish nationality from Nansen, and although it was soon discovered by his shipmates, he was allowed to remain with the expedition, the only non-Norwegian in the party. The remaining crew members were Peter Henriksen, Bernhard Nordahl and Bernt Bentzen, the last–named joining the expedition in Tromso at very short notice.

Voyage

Journey to the ice

Before the start of the voyage Nansen decided to deviate from his original plan: instead of following Jeannette's route to the New Siberian Islands by way of the Bering Strait, he would make a shorter journey, taking Nordenskiöld's North-East Passage along the northern coast of Siberia. Fram left Christiania on 24 June 1893, seen on her way by a cannon salute from the fort and the cheers of thousands of well-wishers. This was the first of a series of farewells as Fram sailed round the coast and moved northward, reaching BergenBergen

Bergen is the second largest city in Norway with a population of as of , . Bergen is the administrative centre of Hordaland county. Greater Bergen or Bergen Metropolitan Area as defined by Statistics Norway, has a population of as of , ....

on 1 July (where there was a great banquet in Nansen's honour), Trondheim

Trondheim

Trondheim , historically, Nidaros and Trondhjem, is a city and municipality in Sør-Trøndelag county, Norway. With a population of 173,486, it is the third most populous municipality and city in the country, although the fourth largest metropolitan area. It is the administrative centre of...

on 5 July and Tromsø

Tromsø

Tromsø is a city and municipality in Troms county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Tromsø.Tromsø city is the ninth largest urban area in Norway by population, and the seventh largest city in Norway by population...

, north of the Arctic Circle

Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of the Earth. For Epoch 2011, it is the parallel of latitude that runs north of the Equator....

, a week later. The last Norwegian port of call was Vardø

Vardø

is a town and a municipality in Finnmark county in the extreme northeast part of Norway.Vardø was established as a municipality on 1 January 1838 . The law required that all cities should be separated from their rural districts, but because of a low population and very few voters, this was...

, where Fram arrived on 18 July. After the final provisions were taken on board, Nansen, Sverdrup, Hansen and Blessing spent their last hours ashore in a sauna

Sauna

A sauna is a small room or house designed as a place to experience dry or wet heat sessions, or an establishment with one or more of these and auxiliary facilities....

, being beaten with birch twigs by two young girls.

The first leg of the journey eastward took Fram across the Barents Sea

Barents Sea

The Barents Sea is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located north of Norway and Russia. Known in the Middle Ages as the Murman Sea, the sea takes its current name from the Dutch navigator Willem Barents...

towards Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya , also known in Dutch as Nova Zembla and in Norwegian as , is an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean in the north of Russia and the extreme northeast of Europe, the easternmost point of Europe lying at Cape Flissingsky on the northern island...

and then to the North Russian settlement of Khabarova where the first batch of dogs was brought on board. On 3 August Fram weighed anchor and moved cautiously eastward, entering the Kara Sea

Kara Sea

The Kara Sea is part of the Arctic Ocean north of Siberia. It is separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya....

the next day. Few ships had sailed the Kara Sea before, and charts were incomplete. On 18 August, in the area of the Yenisei River

Yenisei River

Yenisei , also written as Yenisey, is the largest river system flowing to the Arctic Ocean. It is the central of the three great Siberian rivers that flow into the Arctic Ocean...

delta, an uncharted island was discovered and named Sverdrup Island

Sverdrup Island (Kara Sea)

Sverdrup Island or Svordrup Island is an isolated island in the southern region of the Kara Sea. This island is covered with tundra vegetation. It is located 120 km North of Dikson in the coast of Siberia. The nearest land are the Arkticheskiy Institut Islands, about 90 km to the NE.This...

after Fram's commander. Fram was now moving towards the Taimyr Peninsula and Cape Chelyuskin

Cape Chelyuskin

Cape Chelyuskin is the northernmost point of the Eurasian continent , and the northernmost point of mainland Russia. It is situated at the tip of the Taymyr Peninsula, south of Severnaya Zemlya archipelago, in Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia...

, the most northerly point of the Eurasian continental mass. Heavy ice slowed the expedition's progress, and at the end of August it was held up for four days while the ship's boiler was repaired and cleaned. The crew also experienced the dead water

Dead water

Dead water is the nautical term for a strange phenomenon which can occur when a layer of fresh or brackish water rests on top of denser salt water, without the two layers mixing. A ship powered by direct thrust under the waterline , traveling in such conditions may be hard to maneuver or can even...

phenomenon, where a ship's forward progress is impeded by friction caused by a layer of fresh water lying on top of heavier salt water. On 9 September a wide stretch of ice-free water opened up, and next day Fram rounded Cape Chelyuskin—the second ship to do so, after Nordenskiöld's Vega in 1878—and entered the Laptev Sea

Laptev Sea

The Laptev Sea is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is located between the northern coast of Siberia, the Taimyr Peninsula, Severnaya Zemlya and the New Siberian Islands. Its northern boundary passes from the Arctic Cape to a point with co-ordinates of 79°N and 139°E, and ends at the Anisiy...

.

After being prevented by ice from reaching the mouth of the Olenyok River

Olenyok River

The Olenyok River is a major river in northern Siberian Russia, west of the lower Lena River and east of the Anabar River. It is long, of which around is navigable. Average water discharge is 1210 m³/s...

, where a second batch of dogs was waiting to be picked up, Fram moved north and east towards the New Siberian Islands. Nansen's hope was to find open water to 80° north latitude and then enter the pack; however, on 20 September ice was sighted just south of 78°. Fram followed the line of the ice before stopping in a small bay beyond the 78° mark. On 28 September it became evident that the ice would not break up, and the dogs were moved from the ship to kennels on the ice. On 5 October the rudder was raised to a position of safety and the ship, in Scott Hansen's words, was "well and truly moored for the winter". The position was 78°49'N, 132°53'E.

Drift (first phase)

On 9 October Fram had her first experience of ice pressure. Archer's design was quickly vindicated as the ship rose and fell, the ice being unable to grip the hull. Otherwise the first weeks in the ice were disappointing, as the unpredictable drift moved Fram in gyratory fashion, sometimes north, sometimes south; by 19 November, after six weeks, Fram was south of the latitude at which she had entered the ice.After the sun disappeared on 25 October the ship was lit by electric lamps from a wind-powered generator. The crew settled down to a comfortable routine in which boredom and inactivity were the main enemies. Men began to irritate each other, and fights sometimes broke out. Nansen attempted to start a newspaper, but the project soon fizzled out through lack of interest. Small tasks were undertaken and scientific observations maintained, but there was no urgency. Nansen expressed his frustration in his journal: "I feel I must break through this deadness, this inertia, and find some outlet for my energies." And later: "Can't something happen? Could not a hurricane come and tear up this ice?" Only after the turn of the year, in January 1894, did the northerly direction become generally settled. The 80° mark was finally passed on 22 March.

Based on the uncertain direction and slow speed of the drift, Nansen calculated that it might take the ship five years to reach the pole. In January 1894 he had first discussed with both Henriksen and Johansen the possibility of making a sledge journey with the dogs, from Fram to the pole, though they made no immediate plans. Nansen's first attempts to master dog-driving were an embarrassing failure, but he persevered and gradually achieved better results. He also discovered that the normal cross-country skiing speed was the same as that of dogs pulling loaded sledges. Men could travel under their own power, skiing, rather than riding on the sledge, and loads could be correspondingly increased. This, according to biographer and historian Roland Huntford

Roland Huntford

Roland Huntford is an author, principally of biographies of Polar explorers. He lives in Cambridge, and was formerly Scandinavian correspondent of The Observer, also acting as their winter sports correspondent...

, amounted to a revolution in polar travel methods.

On 19 May, two days after the celebrations for Norway's National Day

Norwegian Constitution Day

Norwegian Constitution Day is the National Day of Norway and is an official national holiday observed on May 17 each year. Among Norwegians, the day is referred to simply as syttende mai or syttande mai , Nasjonaldagen or Grunnlovsdagen , although the latter is less frequent.- Historical...

, Fram passed 81°, indicating that the ship's northerly speed was slowly increasing, though it was still barely a mile (1.6 km) a day. With a growing conviction that a sledge journey might be necessary to reach the pole, in September Nansen decreed that everyone would practice skiing for two hours a day. On 16 November he revealed his intention to the crew: he and one companion would leave the ship and start for the pole when the 83° mark was passed. After reaching the pole the pair would make for Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land, Franz Joseph Land, or Francis Joseph's Land is an archipelago located in the far north of Russia. It is found in the Arctic Ocean north of Novaya Zemlya and east of Svalbard, and is administered by Arkhangelsk Oblast. Franz Josef Land consists of 191 ice-covered islands with a...

, and then cross to Spitsbergen where they hoped to find a ship to take them home. Three days later Nansen asked Hjalmar Johansen, the most experienced dog-driver among the crew, to join him on the polar journey.

The crew spent the following months preparing for the forthcoming dash for the pole. They built sledges that would facilitate fast travel over rough terrain and constructed kayaks on the Inuit

Inuit

The Inuit are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic regions of Canada , Denmark , Russia and the United States . Inuit means “the people” in the Inuktitut language...

model, for use during the expected water crossings. There were endless trials of special clothing and other gear. Violent and prolonged tremors began to shake the ship on 3 January 1895, and two days later the crew disembarked, expecting the ship to be crushed. Instead the pressure lessened, and the crew went back on board and resumed preparations for Nansen's journey. After the excitement it was noted that Fram had drifted beyond Greely's

Adolphus Greely

Adolphus Washington Greely , was an American Polar explorer, a United States Army officer and a recipient of the Medal of Honor.-Early military career:...

Farthest North record of 83°24, and on 8 January was at 83°34'N.

March for the Pole

On 17 February 1895 Nansen began a farewell letter to his wife, Eva, writing that should he come to grief "you will know that your image will be the last I see." He was also reading everything he could about Franz Josef Land, his intended destination after the pole. The archipelagoArchipelago

An archipelago , sometimes called an island group, is a chain or cluster of islands. The word archipelago is derived from the Greek ἄρχι- – arkhi- and πέλαγος – pélagos through the Italian arcipelago...

had been discovered in 1873 by Julius Payer, and was incompletely mapped. It was, however, apparently the home of countless bears and seals, and Nansen saw it as an excellent food source on his return journey to civilization.

On 14 March, with the ship at 84°4'N, the pair finally began their polar march. This was their third attempt to leave the ship; on 26 February and again on the 28th, damage to sledges had forced them to return after travelling short distances. After these mishaps Nansen thoroughly overhauled his equipment, minimised the travelling stores, recalculated weights and reduced the convoy to three sledges, before giving the order to start again. A supporting party accompanied the pair and shared the first night's camp. The next day, Nansen and Johansen skied on alone.

The pair initially traveled mainly over flat snowfields. Nansen had allowed 50 days to cover the 356 nmi (659.3 km; 409.7 mi) to the pole, requiring an average daily journey of seven nautical miles (13 km; 8.1 mi). On 22 March a sextant

Sextant

A sextant is an instrument used to measure the angle between any two visible objects. Its primary use is to determine the angle between a celestial object and the horizon which is known as the altitude. Making this measurement is known as sighting the object, shooting the object, or taking a sight...

observation showed that the pair had travelled 65 nmi (120.4 km; 74.8 mi) towards the pole at a daily average of over nine nautical miles (17 km; 10 mi). This had been achieved despite very low temperatures, typically around -40 F, and small scale mishaps including the loss of the sledgemeter that recorded mileage. However, as the surfaces became uneven and made skiing more difficult, their speeds slowed. A sextant reading on 29 March of 85°56'N indicated that a week's travel had brought them 47 nmi (87 km; 54.1 mi) nearer to the pole, but also showed that their average daily distances were falling. More worryingly, a theodolite

Theodolite

A theodolite is a precision instrument for measuring angles in the horizontal and vertical planes. Theodolites are mainly used for surveying applications, and have been adapted for specialized purposes in fields like metrology and rocket launch technology...

reading that day suggested that they were at only 85°15'N, and they had no means of knowing which of the readings was correct. They realised that they were fighting a southerly drift, and that distances travelled did not necessarily equate to northerly progression. Johansen's diary indicated his failing spirits: "My fingers are all destroyed. All mittens are frozen stiff ... It is becoming worse and worse ... God knows what will happen to us".

On 3 April, after days of difficult travel, Nansen privately began to wonder if the pole might not, after all, be out of reach. Unless the surface improved, their food would not last them to the pole and then on to Franz Josef Land. The next day they calculated their position at a disappointing 86°3'; Nansen confided in his diary that: "I have become more and more convinced we ought to turn before time." After making camp on 7 April Nansen scouted ahead on snowshoes looking for a path forward, but saw only "a veritable chaos of iceblocks stretching as far as the horizon". He decided that they would go no further north, and would head for Cape Fligely in Franz Josef Land. Nansen recorded the latitude of their final northerly camp as 86°13.6'N, almost three degrees beyond Greely's previous Farthest North mark.

Retreat to Franz Josef Land