Lilliput and Blefuscu

Encyclopedia

Lilliput and Blefuscu are two fictional island nations

that appear in the first part of the 1726 novel Gulliver's Travels

by Jonathan Swift

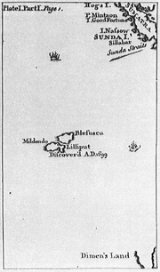

. The two islands are neighbors in the South Indian Ocean

, separated by a channel eight hundred yards wide. Both are inhabited by tiny people who are about one-twelfth the height of ordinary human beings

. Both kingdoms are empires, i.e. realms ruled by a self-styled emperor. The capital of Lilliput is Mildendo.

. Because this area is actually occupied by Australia, and on the basis of other textual evidence, some have concluded that Swift intended to place Lilliput in the Pacific Ocean, to the northeast, not northwest, of Van Diemen's Land.

Lilliput is said to extend 5,000 blustrugs, or twelve miles in circumference. Blefuscu is located northeast of Lilliput, across an 800-yard channel. The only cities mentioned by Swift are Mildendo, the capital of Lilliput, and Blefuscu, capital of Blefuscu.

A modernized Lilliput is the setting of a 1958 sequel children's novel, Castaways in Lilliput, by Henry Winterfeld

. This book provides more geographical detail: other cities in addition to Mildendo include Plips (a major city and cathedral town), Wiggywack (a suburb of Mildendo and seat of the Island Council), Tottenham (on the west coast), and Allenbeck (at the mouth of a river on the west coast).

(who carries a white staff) and several other officials (who later bring articles of impeachment

against Gulliver on grounds of treason

): the galbet or high admiral

, Skyresh Bolgolam; the lord high treasurer

, Flimnap; the general

, Limnoc; the chamberlain

, Lalcom; and the grand justiciary

, Balmuff.

and the kingdom of France

, respectively, as they were in the early 18th century. Only the internal politics of Lilliput are described in detail; these are parodies of British politics, in which the great central issues of the day are belittled and reduced to unimportance.

For instance, the two major political parties of the day were the Whigs

and the Tories. The Tories are parodied as the Tramecksan or "High-Heels" (due to their adhesion to the high church

party of the Church of England

, and their exalted views of royal supremacy), while the Whigs are represented as the Slamecksan or "Low-Heels" (the Whigs inclined toward low church

views, and believed in parliamentary supremacy). These issues, generally considered to be of fundamental importance to the constitution of Great Britain, are reduced by Swift to a difference in fashions.

The Emperor of Lilliput is described as a partisan of the Low-Heels, just as King George I

employed only Whigs in his administration; the Emperor's heir is described as having "one of his heels higher than the other", which describes the encouragement by the Prince of Wales (the future George II

) of the political opposition during his father's life; once he ascended the throne, however, George II was as staunch a favorer of the Whigs as his father had been.

The novel further describes an intra-Lilliputian quarrel over the practice of breaking eggs. Traditionally, Lilliputians broke boiled eggs on the larger end; a few generations ago, an Emperor of Lilliput had decreed that all eggs be broken on the smaller end. The differences between Big-Endians (those who broke their eggs at the larger end) and Little-Endians had given rise to "six rebellions... wherein one Emperor lost his life, and another his crown".

The Big-Endian/Little-Endian controversy reflects, in a much simplified form, British quarrels over religion. England had been, less than 200 years previously, a Catholic (Big-Endian) country; but a series of reforms beginning in the 1530s under King Henry VIII

(ruled 1509-1547), Edward VI

(1547–1553), and Queen Elizabeth I

(1558–1603) had converted most of the country to Protestantism (Little-Endianism), in the episcopalian form of the Church of England

. At the same time, revolution and reform in Scotland (1560) had also converted that country to Presbyterian

Protestantism, which led to fresh difficulties when England and Scotland were united under one ruler, James I

(1603–1625).

Religiously inspired revolts and rebellions followed, in which, indeed, one king, Charles I

(1625–1649) lost his life, and his son James II

lost his crown and fled to France (1685–1688). Some of these conflicts were between Protestants and Catholics; others were between different branches of Protestantism. Swift does not clearly distinguish between these different kinds of religious strife.

Swift has his Lilliputian informant blame the "civil commotions" on the propaganda of the Emperor of Blefuscu, i.e. the King of France; this primarily reflects the encouragement given by King Louis XIV of France

to James II in pursuit of his policies to advance the toleration of Catholicism in Great Britain. He adds that "when (the commotions) were quelled, the (Big-Endian) exiles always fled for refuge to that empire (Blefuscu/France)". This partially reflects the exile of King Charles II

on the Continent (in France, Germany, the Spanish Netherlands, and the Dutch Republic) from 1651 to 1660, but more particularly the exile of the Catholic King James II from 1688-1701. James II was dead by the time Swift wrote Gulliver's Travels, but his heir James Francis Edward Stuart

, also Catholic, maintained his pretensions to the British throne from a court in France (primarily at Saint-Germain-en-Laye

) until 1717, and both Jameses were regarded as a serious threat to the stability of the British monarchy until the end of the reign of George II. The court of the Pretender attracted those Jacobites

, and their Tory sympathizers, whose political activity precluded them staying safely in Great Britain; notable among them was Swift's friend, the Anglican Bishop of Rochester Francis Atterbury

, who was exiled to France in 1722.

Swift's Lilliputian claims that the machinations of "Big-Endian exiles" at the court of the Emperor of Blefuscu have brought about a continuous war between Lilliput and Blefuscu for "six and thirty moons" (Lilliputians calculate time in 'moons', not years; their time-scale is apparently also one-twelfth the size of normal humans.) This is an allusion to the wars fought under King William III

and Queen Anne against France under Louis XIV, the War of the Grand Alliance

(1689–1697) and the War of the Spanish Succession

(1701–1713). In both cases, the claims of the exiled House of Stuart were marginal to other causes of war, but were an important propaganda point in Great Britain itself, as both James II and James Francis Edward were accused of allying with foreigners to force Catholicism on the British people.

In the novel, Gulliver washes up on the shore of Lilliput and is captured by the inhabitants while asleep. He offers his services to the Emperor of Lilliput in his war against Blefuscu, and succeeds in capturing the (one-twelfth sized) Blefuscudian fleet. Despite a triumphant welcome, he soon finds himself at odds with the Emperor of Lilliput, as he declines to conquer the rest of Blefuscu for him and to force the Blefuscudians to adopt Little-Endianism.

This position of Gulliver's reflects the decision of the Tory government of to withdraw from the War of the Spanish Succession, despite the opposition of Britain's allies, on the grounds that the important objects of the war had been met, and that the larger claims which Whig members of Parliament claimed on behalf of Britain were excessive. This withdrawal was seen by the Whigs as a betrayal of British interests; Swift, a Tory, is here engaged in an apology on behalf of the policy.

Gulliver is, after further adventures, condemned as a traitor by the Council of Lilliput, and condemned to be blinded; he escapes his punishment by fleeing to Blefuscu. This condemnation parallels that issued to the chief ministers of the Tory government that had made peace with France, Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Mortimer

, who was impeached and imprisoned in the Tower of London

from 1715 to 1717; and Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke

, who, after his political fall, received vague threats of capital punishment and fled to France in 1715, where he remained until 1723.

Fictional country

A fictional country is a country that is made up for fictional stories, and does not exist in real life, or one that people believe in without proof....

that appear in the first part of the 1726 novel Gulliver's Travels

Gulliver's Travels

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, better known simply as Gulliver's Travels , is a novel by Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift that is both a satire on human nature and a parody of...

by Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

. The two islands are neighbors in the South Indian Ocean

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the world's oceanic divisions, covering approximately 20% of the water on the Earth's surface. It is bounded on the north by the Indian Subcontinent and Arabian Peninsula ; on the west by eastern Africa; on the east by Indochina, the Sunda Islands, and...

, separated by a channel eight hundred yards wide. Both are inhabited by tiny people who are about one-twelfth the height of ordinary human beings

1:12 scale

1:12 scale is a traditional scale for models and miniatures, in which 12 units on the original is represented by one unit on the model...

. Both kingdoms are empires, i.e. realms ruled by a self-styled emperor. The capital of Lilliput is Mildendo.

Geography

Swift gives the location of Lilliput and Blefuscu as Latitude 30°2′S, to the northwest of Van Diemen's LandVan Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by most Europeans for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to land on the shores of Tasmania...

. Because this area is actually occupied by Australia, and on the basis of other textual evidence, some have concluded that Swift intended to place Lilliput in the Pacific Ocean, to the northeast, not northwest, of Van Diemen's Land.

Lilliput is said to extend 5,000 blustrugs, or twelve miles in circumference. Blefuscu is located northeast of Lilliput, across an 800-yard channel. The only cities mentioned by Swift are Mildendo, the capital of Lilliput, and Blefuscu, capital of Blefuscu.

A modernized Lilliput is the setting of a 1958 sequel children's novel, Castaways in Lilliput, by Henry Winterfeld

Henry Winterfeld

Henry Winterfeld , published under the pseudonym Manfred Michael, was a German writer and artist famous for his children's and young adult novels.-Bibliography:...

. This book provides more geographical detail: other cities in addition to Mildendo include Plips (a major city and cathedral town), Wiggywack (a suburb of Mildendo and seat of the Island Council), Tottenham (on the west coast), and Allenbeck (at the mouth of a river on the west coast).

History and politics

Lilliput is said to be ruled by an Emperor, Golbasto Momarem Evlame Gurdilo Shefin Mully Ully Gue. He is assisted by a first ministerFirst Minister

A First Minister is the leader of a government cabinet.-Canada:In Canada, "First Ministers" is a collective term that refers to all Canadian first ministers of the Crown, otherwise known as heads of government, including the Prime Minister of Canada and the provincial and territorial premiers...

(who carries a white staff) and several other officials (who later bring articles of impeachment

Articles of impeachment

The articles of impeachment are the set of charges drafted against a public official to initiate the impeachment process. The articles of impeachment do not result in the removal of the official, but instead require the enacting body to take further action, such as bringing the articles to a vote...

against Gulliver on grounds of treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

): the galbet or high admiral

Admiral

Admiral is the rank, or part of the name of the ranks, of the highest naval officers. It is usually considered a full admiral and above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet . It is usually abbreviated to "Adm" or "ADM"...

, Skyresh Bolgolam; the lord high treasurer

Lord High Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Act of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third highest ranked Great Officer of State, below the Lord High Chancellor and above the Lord President...

, Flimnap; the general

General

A general officer is an officer of high military rank, usually in the army, and in some nations, the air force. The term is widely used by many nations of the world, and when a country uses a different term, there is an equivalent title given....

, Limnoc; the chamberlain

Chamberlain (office)

A chamberlain is an officer in charge of managing a household. In many countries there are ceremonial posts associated with the household of the sovereign....

, Lalcom; and the grand justiciary

Chief Justice

The Chief Justice in many countries is the name for the presiding member of a Supreme Court in Commonwealth or other countries with an Anglo-Saxon justice system based on English common law, such as the Supreme Court of Canada, the Constitutional Court of South Africa, the Court of Final Appeal of...

, Balmuff.

Satirical interpretations

Lilliput and Blefuscu were intended as, and understood to be, satirical portraits of the kingdom of Great BritainGreat Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

and the kingdom of France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, respectively, as they were in the early 18th century. Only the internal politics of Lilliput are described in detail; these are parodies of British politics, in which the great central issues of the day are belittled and reduced to unimportance.

For instance, the two major political parties of the day were the Whigs

British Whig Party

The Whigs were a party in the Parliament of England, Parliament of Great Britain, and Parliament of the United Kingdom, who contested power with the rival Tories from the 1680s to the 1850s. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute rule...

and the Tories. The Tories are parodied as the Tramecksan or "High-Heels" (due to their adhesion to the high church

High church

The term "High Church" refers to beliefs and practices of ecclesiology, liturgy and theology, generally with an emphasis on formality, and resistance to "modernization." Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term has traditionally been principally associated with the...

party of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

, and their exalted views of royal supremacy), while the Whigs are represented as the Slamecksan or "Low-Heels" (the Whigs inclined toward low church

Low church

Low church is a term of distinction in the Church of England or other Anglican churches initially designed to be pejorative. During the series of doctrinal and ecclesiastic challenges to the established church in the 16th and 17th centuries, commentators and others began to refer to those groups...

views, and believed in parliamentary supremacy). These issues, generally considered to be of fundamental importance to the constitution of Great Britain, are reduced by Swift to a difference in fashions.

The Emperor of Lilliput is described as a partisan of the Low-Heels, just as King George I

George I of Great Britain

George I was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1 August 1714 until his death, and ruler of the Duchy and Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg in the Holy Roman Empire from 1698....

employed only Whigs in his administration; the Emperor's heir is described as having "one of his heels higher than the other", which describes the encouragement by the Prince of Wales (the future George II

George II of Great Britain

George II was King of Great Britain and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Archtreasurer and Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire from 11 June 1727 until his death.George was the last British monarch born outside Great Britain. He was born and brought up in Northern Germany...

) of the political opposition during his father's life; once he ascended the throne, however, George II was as staunch a favorer of the Whigs as his father had been.

The novel further describes an intra-Lilliputian quarrel over the practice of breaking eggs. Traditionally, Lilliputians broke boiled eggs on the larger end; a few generations ago, an Emperor of Lilliput had decreed that all eggs be broken on the smaller end. The differences between Big-Endians (those who broke their eggs at the larger end) and Little-Endians had given rise to "six rebellions... wherein one Emperor lost his life, and another his crown".

The Big-Endian/Little-Endian controversy reflects, in a much simplified form, British quarrels over religion. England had been, less than 200 years previously, a Catholic (Big-Endian) country; but a series of reforms beginning in the 1530s under King Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

(ruled 1509-1547), Edward VI

Edward VI of England

Edward VI was the King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death. He was crowned on 20 February at the age of nine. The son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, Edward was the third monarch of the Tudor dynasty and England's first monarch who was raised as a Protestant...

(1547–1553), and Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

(1558–1603) had converted most of the country to Protestantism (Little-Endianism), in the episcopalian form of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

. At the same time, revolution and reform in Scotland (1560) had also converted that country to Presbyterian

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

Protestantism, which led to fresh difficulties when England and Scotland were united under one ruler, James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

(1603–1625).

Religiously inspired revolts and rebellions followed, in which, indeed, one king, Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

(1625–1649) lost his life, and his son James II

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

lost his crown and fled to France (1685–1688). Some of these conflicts were between Protestants and Catholics; others were between different branches of Protestantism. Swift does not clearly distinguish between these different kinds of religious strife.

Swift has his Lilliputian informant blame the "civil commotions" on the propaganda of the Emperor of Blefuscu, i.e. the King of France; this primarily reflects the encouragement given by King Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

to James II in pursuit of his policies to advance the toleration of Catholicism in Great Britain. He adds that "when (the commotions) were quelled, the (Big-Endian) exiles always fled for refuge to that empire (Blefuscu/France)". This partially reflects the exile of King Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

on the Continent (in France, Germany, the Spanish Netherlands, and the Dutch Republic) from 1651 to 1660, but more particularly the exile of the Catholic King James II from 1688-1701. James II was dead by the time Swift wrote Gulliver's Travels, but his heir James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward, Prince of Wales was the son of the deposed James II of England...

, also Catholic, maintained his pretensions to the British throne from a court in France (primarily at Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Saint-Germain-en-Laye is a commune in the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France in north-central France. It is located in the western suburbs of Paris from the centre.Inhabitants are called Saint-Germanois...

) until 1717, and both Jameses were regarded as a serious threat to the stability of the British monarchy until the end of the reign of George II. The court of the Pretender attracted those Jacobites

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was the political movement in Britain dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England, Scotland, later the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Ireland...

, and their Tory sympathizers, whose political activity precluded them staying safely in Great Britain; notable among them was Swift's friend, the Anglican Bishop of Rochester Francis Atterbury

Francis Atterbury

Francis Atterbury was an English man of letters, politician and bishop.-Early life:He was born at Milton Keynes in Buckinghamshire, where his father was rector. He was educated at Westminster School and Christ Church, Oxford, where he became a tutor...

, who was exiled to France in 1722.

Swift's Lilliputian claims that the machinations of "Big-Endian exiles" at the court of the Emperor of Blefuscu have brought about a continuous war between Lilliput and Blefuscu for "six and thirty moons" (Lilliputians calculate time in 'moons', not years; their time-scale is apparently also one-twelfth the size of normal humans.) This is an allusion to the wars fought under King William III

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

and Queen Anne against France under Louis XIV, the War of the Grand Alliance

War of the Grand Alliance

The Nine Years' War – often called the War of the Grand Alliance, the War of the Palatine Succession, or the War of the League of Augsburg – was a major war of the late 17th century fought between King Louis XIV of France, and a European-wide coalition, the Grand Alliance, led by the Anglo-Dutch...

(1689–1697) and the War of the Spanish Succession

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was fought among several European powers, including a divided Spain, over the possible unification of the Kingdoms of Spain and France under one Bourbon monarch. As France and Spain were among the most powerful states of Europe, such a unification would have...

(1701–1713). In both cases, the claims of the exiled House of Stuart were marginal to other causes of war, but were an important propaganda point in Great Britain itself, as both James II and James Francis Edward were accused of allying with foreigners to force Catholicism on the British people.

In the novel, Gulliver washes up on the shore of Lilliput and is captured by the inhabitants while asleep. He offers his services to the Emperor of Lilliput in his war against Blefuscu, and succeeds in capturing the (one-twelfth sized) Blefuscudian fleet. Despite a triumphant welcome, he soon finds himself at odds with the Emperor of Lilliput, as he declines to conquer the rest of Blefuscu for him and to force the Blefuscudians to adopt Little-Endianism.

This position of Gulliver's reflects the decision of the Tory government of to withdraw from the War of the Spanish Succession, despite the opposition of Britain's allies, on the grounds that the important objects of the war had been met, and that the larger claims which Whig members of Parliament claimed on behalf of Britain were excessive. This withdrawal was seen by the Whigs as a betrayal of British interests; Swift, a Tory, is here engaged in an apology on behalf of the policy.

Gulliver is, after further adventures, condemned as a traitor by the Council of Lilliput, and condemned to be blinded; he escapes his punishment by fleeing to Blefuscu. This condemnation parallels that issued to the chief ministers of the Tory government that had made peace with France, Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Mortimer

Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Mortimer

Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer KG was a British politician and statesman of the late Stuart and early Georgian periods. He began his career as a Whig, before defecting to a new Tory Ministry. Between 1711 and 1714 he served as First Lord of the Treasury, effectively Queen...

, who was impeached and imprisoned in the Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

from 1715 to 1717; and Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke

Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke

Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke was an English politician, government official and political philosopher. He was a leader of the Tories, and supported the Church of England politically despite his atheism. In 1715 he supported the Jacobite rebellion of 1715 which sought to overthrow the...

, who, after his political fall, received vague threats of capital punishment and fled to France in 1715, where he remained until 1723.

Later history

Winterfeld's sequel children's chapter book Castaways in Lilliput provides further details of Lilliputian history. The Emperor of Gulliver's time, Mully Ully Gue, is said to have reigned 1657-1746. (This contradicts Swift's account, in which the Emperor is only 28 years old and has reigned about seven years when Gulliver arrives in 1699.) His descendant, Alice, is the reigning Queen in the 1950s when three Australian children visit the island. English has become the official language, due to a decision of the Council of the Island in 1751. The monetary system has apparently also been changed, the sprug of Swift's novel replaced by the onze, equal to ten dimelings or 100 bims. Technology has kept pace with the outside world, so the Lilliputians have trains, automobiles, helicopters, telephones, and telegraphs.Flag of Lilliput

Winterfeld describes the flag of Lilliput as having blue and white stripes with a golden crown on a red field. These symbols are also painted on the police helicopters.Other references

- Lilliput is reputedly named after the real area of Lilliput on the shores of Lough EnnellLough EnnellLough Ennell is a lake near the town of Mullingar, County Westmeath, Ireland. It is situated beside the N52 road, off the Mullingar/Kilbeggan road. It is approximately 4.5 miles long by 2 miles wide, with an area of about...

in Dysart, MullingarMullingarMullingar is the county town of County Westmeath in Ireland. The Counties of Meath and Westmeath Act of 1542, proclaimed Westmeath a county, separating it from Meath. Mullingar became the administrative centre for County Westmeath...

, County WestmeathCounty Westmeath-Economy:Westmeath has a strong agricultural economy. Initially, development occurred around the major market centres of Mullingar, Moate, and Kinnegad. Athlone developed due to its military significance, and its strategic location on the main Dublin–Galway route across the River Shannon. Mullingar...

in Ireland. Swift was a regular visitor to the RochfortRobert RochfortRobert Rochfort was attorney-general, judge and speaker of the Irish House of Commons.Rochfort was probably born on 9 December 1652. He was the second son of Lieutenant-Colonel James "Prime-Iron " Rochfort , a Cromwellian soldier, and Thomasina Pigot...

family at Gaulstown House. It's said that it was when Swift looked across the expanse of Lough Ennell one day and saw the tiny human figures on the opposite shore of the lake that he conceived the idea of the Lilliputians featured in Gulliver's Travels. There is also an early Christian association - St. Patrick’s sister, Lupita, is known to the Lilliput area, which may recall her name. In fact, the townland known from ancient times as Nure was renamed Lileput or Lilliput shortly after the publication of Gulliver's Travels in honour of Swift's association with the area. Lilliput House has stood in the locality since the Eighteenth Century.

- Lilliput and Blefuscu were the names used for Britain and France, respectively, in a series of semi-fictional transcripts (with mutated names of people and places) of debates in the British Parliament. This series was written by William GuthrieWilliam Guthrie (historian)William Guthrie was a Scottish writer and journalist, now remembered as a historian.-Life:The son of an Episcopalian clergyman, he was born at Brechin, Forfarshire, in 1708...

, Samuel JohnsonSamuel JohnsonSamuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

, and John Hawkesworth, and was printed in Edward CaveEdward CaveEdward Cave was an English printer, editor and publisher. In The Gentleman's Magazine he created the first general-interest "magazine" in the modern sense....

's periodical The Gentleman's MagazineThe Gentleman's MagazineThe Gentleman's Magazine was founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term "magazine" for a periodical...

from 1738 to 1746.

- The word lilliputian has become an adjective meaning "very small in size", or "petty or trivial". When used as a noun, it means either "a tiny person" or "a person with a narrow outlook, who minds the petty and trivial things."

- The use of the terms "Big-Endian" and "Little-Endian" in the story is the source of the computing term endiannessEndiannessIn computing, the term endian or endianness refers to the ordering of individually addressable sub-components within the representation of a larger data item as stored in external memory . Each sub-component in the representation has a unique degree of significance, like the place value of digits...

.

- Neela Mahendra, the love interest in Salman Rushdie's novel FuryFury (novel)Fury is the seventh novel written by Salman Rushdie. It was published in 2001.-Plot summary:Malik Solanka, a Cambridge-educated millionaire from Bombay, is looking for an escape from himself...

, is an "Indo-Lilly", a member of the Indian Diaspora from the politically unstable country of Lilliput-and-Blefuscu.

- Several craters on Mars' moon PhobosPhobos (moon)Phobos is the larger and closer of the two natural satellites of Mars. Both moons were discovered in 1877. With a mean radius of , Phobos is 7.24 times as massive as Deimos...

are named after Lilliputians. Perhaps inspired by Johannes KeplerJohannes KeplerJohannes Kepler was a German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer. A key figure in the 17th century scientific revolution, he is best known for his eponymous laws of planetary motion, codified by later astronomers, based on his works Astronomia nova, Harmonices Mundi, and Epitome of Copernican...

(and quoting Kepler's third lawKepler's laws of planetary motionIn astronomy, Kepler's laws give a description of the motion of planets around the Sun.Kepler's laws are:#The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci....

), Swift's satire Gulliver's Travels refers to two moons in Part 3, Chapter 3 (the "Voyage to LaputaLaputaLaputa is a fictional place from the book Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift.Laputa is a fictional flying island or rock, about 4.5 miles in diameter, with an adamantine base, which its inhabitants can maneuver in any direction using magnetic levitation...

"), in which the astronomers of Laputa are described as having discovered two satellites of Mars orbiting at distances of 3 and 5 Martian diameters, and periods of 10 and 21.5 hours, respectively.

- Lilliput is mentioned throughout the recent Malplaquet trilogy of children's novels by Andrew Dalton. Taking much of their initial inspiration from T.H. White's, Mistress Masham's ReposeMistress Masham's ReposeMistress Masham's Repose is a novel by T. H. White that describes the adventures of a girl who discovers a group of Lilliputians, a race of tiny people from Jonathan Swift's satirical classic Gulliver's Travels...

, the books describe the adventures of a large colony of Lilliputians living secretly in the enormous and mysterious grounds of an English Country House (Stowe HouseStowe HouseStowe House is a Grade I listed country house located in Stowe, Buckinghamshire, England. It is the home of Stowe School, an independent school. The gardens , a significant example of the English Landscape Garden style, along with part of the Park, passed into the ownership of The National Trust...

in BuckinghamshireBuckinghamshireBuckinghamshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan home county in South East England. The county town is Aylesbury, the largest town in the ceremonial county is Milton Keynes and largest town in the non-metropolitan county is High Wycombe....

). Their longed-for return to their ancestral homeland is one of the major themes of the stories.

See also

- Gulliver's TravelsGulliver's TravelsTravels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, better known simply as Gulliver's Travels , is a novel by Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift that is both a satire on human nature and a parody of...

- BrobdingnagBrobdingnagBrobdingnag is a fictional land in Jonathan Swift's satirical novel Gulliver's Travels occupied by giants. Lemuel Gulliver visits the land after the ship on which he is travelling is blown off course and he is separated from a party exploring the unknown land.The adjective Brobdingnagian has come...

- HouyhnhnmHouyhnhnmHouyhnhnms are a race of intelligent horses described in the last part of Jonathan Swift's satirical Gulliver's Travels. The name is pronounced either or ....

- StruldbrugStruldbrugIn Jonathan Swift's novel Gulliver's Travels, the name struldbrug is given to those humans in the nation of Luggnagg who are born seemingly normal, but are in fact immortal. However, although struldbrugs do not die, they do nonetheless continue aging...

- Yahoo (Gulliver's Travels)