Inventions in the Islamic world

Encyclopedia

A number of invention

s were developed in the medieval Islamic world

, a geopolitical region that has at various times extended from Spain and Africa in the west to the Indian subcontinent

in the east. The inventions listed here were developed during the medieval Islamic world, which covers the period from the early Caliphate

to the later Ottoman

, Safavid

and Mughal

empires. In particular, the majority of inventions here date back to the Islamic Golden Age

, which is traditionally dated from the 8th to the 13th centuries.

Invention

An invention is a novel composition, device, or process. An invention may be derived from a pre-existing model or idea, or it could be independently conceived, in which case it may be a radical breakthrough. In addition, there is cultural invention, which is an innovative set of useful social...

s were developed in the medieval Islamic world

Muslim world

The term Muslim world has several meanings. In a religious sense, it refers to those who adhere to the teachings of Islam, referred to as Muslims. In a cultural sense, it refers to Islamic civilization, inclusive of non-Muslims living in that civilization...

, a geopolitical region that has at various times extended from Spain and Africa in the west to the Indian subcontinent

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent, also Indian Subcontinent, Indo-Pak Subcontinent or South Asian Subcontinent is a region of the Asian continent on the Indian tectonic plate from the Hindu Kush or Hindu Koh, Himalayas and including the Kuen Lun and Karakoram ranges, forming a land mass which extends...

in the east. The inventions listed here were developed during the medieval Islamic world, which covers the period from the early Caliphate

Caliphate

The term caliphate, "dominion of a caliph " , refers to the first system of government established in Islam and represented the political unity of the Muslim Ummah...

to the later Ottoman

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, Safavid

Safavid dynasty

The Safavid dynasty was one of the most significant ruling dynasties of Iran. They ruled one of the greatest Persian empires since the Muslim conquest of Persia and established the Twelver school of Shi'a Islam as the official religion of their empire, marking one of the most important turning...

and Mughal

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire , or Mogul Empire in traditional English usage, was an imperial power from the Indian Subcontinent. The Mughal emperors were descendants of the Timurids...

empires. In particular, the majority of inventions here date back to the Islamic Golden Age

Islamic Golden Age

During the Islamic Golden Age philosophers, scientists and engineers of the Islamic world contributed enormously to technology and culture, both by preserving earlier traditions and by adding their own inventions and innovations...

, which is traditionally dated from the 8th to the 13th centuries.

Chemistry

- Acetic acidAcetic acidAcetic acid is an organic compound with the chemical formula CH3CO2H . It is a colourless liquid that when undiluted is also called glacial acetic acid. Acetic acid is the main component of vinegar , and has a distinctive sour taste and pungent smell...

: Jābir ibn Hayyān isolated acetic acid from vinegar. - Citric acidCitric acidCitric acid is a weak organic acid. It is a natural preservative/conservative and is also used to add an acidic, or sour, taste to foods and soft drinks...

Jābir ibn Hayyān is also credited with the discovery and isolation of citric acid, the sour component of lemons and other unripe fruits. - Nitric acidNitric acidNitric acid , also known as aqua fortis and spirit of nitre, is a highly corrosive and toxic strong acid.Colorless when pure, older samples tend to acquire a yellow cast due to the accumulation of oxides of nitrogen. If the solution contains more than 86% nitric acid, it is referred to as fuming...

, sulfuric acidSulfuric acidSulfuric acid is a strong mineral acid with the molecular formula . Its historical name is oil of vitriol. Pure sulfuric acid is a highly corrosive, colorless, viscous liquid. The salts of sulfuric acid are called sulfates...

, and hydrochloric acidHydrochloric acidHydrochloric acid is a solution of hydrogen chloride in water, that is a highly corrosive, strong mineral acid with many industrial uses. It is found naturally in gastric acid....

: The mineral acids nitric acid, sulfuric acid, and hydrochloric acid were first isolated by Jābir ibn Hayyān. He originally referred to sulfuric acid as the oil of vitriol. - Tartaric acidTartaric acidTartaric acid is a white crystalline diprotic organic acid. It occurs naturally in many plants, particularly grapes, bananas, and tamarinds; is commonly combined with baking soda to function as a leavening agent in recipes, and is one of the main acids found in wine. It is added to other foods to...

: Jābir ibn Hayyān isolated tartaric acid from wine-making residues.

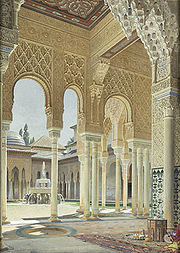

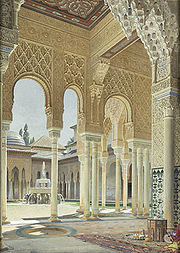

Architecture

- ArabesqueArabesqueThe arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "surface decorations based on rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines, often combined with other elements...

: An elaborative application of repeating geometric forms often found decorating the walls of mosqueMosqueA mosque is a place of worship for followers of Islam. The word is likely to have entered the English language through French , from Portuguese , from Spanish , and from Berber , ultimately originating in — . The Arabic word masjid literally means a place of prostration...

s. - MinaretMinaretA minaret مناره , sometimes مئذنه) is a distinctive architectural feature of Islamic mosques, generally a tall spire with an onion-shaped or conical crown, usually either free standing or taller than any associated support structure. The basic form of a minaret includes a base, shaft, and gallery....

: The minaret is a distinctive architectural feature of Islamic architectureIslamic architectureIslamic architecture encompasses a wide range of both secular and religious styles from the foundation of Islam to the present day, influencing the design and construction of buildings and structures in Islamic culture....

, especially mosques, dating back to the early centuries of Islam. Minarets are generally tall spires with onion-shaped crownsOnion domeAn onion dome is a dome whose shape resembles the onion, after which they are named. Such domes are often larger in diameter than the drum upon which they are set, and their height usually exceeds their width...

, usually either free standing or much taller than any surrounding support structure. The tallest minaret in pre-modern times was the Qutub MinarQutub MinarQutub Minar also Qutb Minar, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Located in Delhi, India. The Qutub Minar is constructed with red sandstone and marble, and is the tallest minaret in India, with a height of 72.5 meters , contains 379 stairs to reach the top, and the diameter of base is 14.3 meters...

, which was 72.5 meters (237.9 ft) tall and was built in the 12th century, and it remains the tallest brick and stone minaret in the world. - Prefabricated homePrefabricated homePrefabricated homes, often referred to as prefab homes, are dwellings manufactured off-site in advance, usually in standard sections that can be easily shipped and assembled....

and movable structure: The first prefabricated homes and movable structures were invented in 16th century Mughal IndiaMughal EmpireThe Mughal Empire , or Mogul Empire in traditional English usage, was an imperial power from the Indian Subcontinent. The Mughal emperors were descendants of the Timurids...

by Akbar the GreatAkbar the GreatAkbar , also known as Shahanshah Akbar-e-Azam or Akbar the Great , was the third Mughal Emperor. He was of Timurid descent; the son of Emperor Humayun, and the grandson of the Mughal Emperor Zaheeruddin Muhammad Babur, the ruler who founded the Mughal dynasty in India...

. These structures were reported by Arif Qandahari in 1579.

Milling

- Bridge mill: The bridge mill was a unique type of watermillWatermillA watermill is a structure that uses a water wheel or turbine to drive a mechanical process such as flour, lumber or textile production, or metal shaping .- History :...

that was built as part of the superstructureSuperstructureA superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships...

of a bridge. The earliest record of a bridge mill is from Córdoba, SpainCórdoba, Spain-History:The first trace of human presence in the area are remains of a Neanderthal Man, dating to c. 32,000 BC. In the 8th century BC, during the ancient Tartessos period, a pre-urban settlement existed. The population gradually learned copper and silver metallurgy...

in the 12th century. - Vertical-axle windmillWindmillA windmill is a machine which converts the energy of wind into rotational energy by means of vanes called sails or blades. Originally windmills were developed for milling grain for food production. In the course of history the windmill was adapted to many other industrial uses. An important...

: A small wind wheel operating an organ is described as early as the 1st century AD by Hero of AlexandriaHero of AlexandriaHero of Alexandria was an ancient Greek mathematician and engineerEnc. Britannica 2007, "Heron of Alexandria" who was active in his native city of Alexandria, Roman Egypt...

. The first vertical-axle windmills were eventually built in SistanSistanSīstān is a border region in eastern Iran , southwestern Afghanistan and northern tip of Southwestern Pakistan .-Etymology:...

, AfghanistanAfghanistanAfghanistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located in the centre of Asia, forming South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East. With a population of about 29 million, it has an area of , making it the 42nd most populous and 41st largest nation in the world...

as described by Muslim geographers. These windmills had long vertical driveshaftDriveshaftA drive shaft, driveshaft, driving shaft, propeller shaft, or Cardan shaft is a mechanical component for transmitting torque and rotation, usually used to connect other components of a drive train that cannot be connected directly because of distance or the need to allow for relative movement...

s with rectangle shaped blades. They may have been constructed as early as the time of the second RashidunRashidunThe Rightly Guided Caliphs or The Righteous Caliphs is a term used in Sunni Islam to refer to the first four Caliphs who established the Rashidun Caliphate. The concept of "Rightly Guided Caliphs" originated with the Abbasid Dynasty...

caliphCaliphThe Caliph is the head of state in a Caliphate, and the title for the ruler of the Islamic Ummah, an Islamic community ruled by the Shari'ah. It is a transcribed version of the Arabic word which means "successor" or "representative"...

UmarUmar`Umar ibn al-Khattāb c. 2 November , was a leading companion and adviser to the Islamic prophet Muhammad who later became the second Muslim Caliph after Muhammad's death....

(634-644 AD), though some argue that this account may have been a 10th century amendment. Made of six to twelve sails covered in reed matting or cloth material, these windmills were used to grind corn and draw up water, and used in the gristmilling and sugarcane industries. Horizontal axle windmills of the type generally used today, however, were developed in Northwestern Europe in the 1180s.

Military

- Marching bandMarching bandMarching band is a physical activity in which a group of instrumental musicians generally perform outdoors and incorporate some type of marching with their musical performance. Instrumentation typically includes brass, woodwinds, and percussion instruments...

and military bandMilitary bandA military band originally was a group of personnel that performs musical duties for military functions, usually for the armed forces. A typical military band consists mostly of wind and percussion instruments. The conductor of a band commonly bears the title of Bandmaster or Director of Music...

: The marching band and military band both have their origins in the Ottoman military bandOttoman military bandOttoman military bands are thought to be the oldest variety of military marching band in the world. Though they are often known by the Persian-derived word mahtar in the West, that word, properly speaking, refers only to a single musician in the band...

, performed by the JanissaryJanissaryThe Janissaries were infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops and bodyguards...

since the 16th century.

Pottery

- AlbarelloAlbarelloAn albarello is a type of maiolica earthenware jar, originally a medicinal jar designed to hold apothecaries' ointments and dry drugs. The development of this type of pharmacy jar had its roots in the Middle East during the time of the Islamic conquests....

: An albarello is a type of maiolicaMaiolicaMaiolica is Italian tin-glazed pottery dating from the Renaissance. It is decorated in bright colours on a white background, frequently depicting historical and legendary scenes.-Name:...

earthenware jar originally designed to hold apothecaries' ointments and dry drugs. The development of this type of pharmacy jar had its roots in the Islamic Middle East. - FritwareFritwareFritware, also known as Islamic stone-paste, is a type of pottery in which frit is added to clay to reduce its fusion temperature. As a result, the mixture can be fired at a lower temperature than clay alone....

: It refers to a type of pottery which was first developed in the Near East, where production is dated to the late 1st millennium AD through the second millennium AD FritFritFrit is a ceramic composition that has been fused in a special fusing oven, quenched to form a glass, and granulated. Frits form an important part of the batches used in compounding enamels and ceramic glazes; the purpose of this pre-fusion is to render any soluble and/or toxic components insoluble...

was a significant ingredient. A recipe for "fritware" dating to c. 1300 AD written by Abu’l Qasim reports that the ratio of quartz to "frit-glass" to white clay is 10:1:1. This type of pottery has also been referred to as "stonepaste" and "faience" among other names. A 9th century corpus of "proto-stonepaste" from BaghdadBaghdadBaghdad is the capital of Iraq, as well as the coterminous Baghdad Governorate. The population of Baghdad in 2011 is approximately 7,216,040...

has "relict glass fragments" in its fabric. - Hispano-Moresque ware: This was a style of Islamic potteryPotteryPottery is the material from which the potteryware is made, of which major types include earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. The place where such wares are made is also called a pottery . Pottery also refers to the art or craft of the potter or the manufacture of pottery...

created in Islamic Spain, after the MoorsMoorsThe description Moors has referred to several historic and modern populations of the Maghreb region who are predominately of Berber and Arab descent. They came to conquer and rule the Iberian Peninsula for nearly 800 years. At that time they were Muslim, although earlier the people had followed...

had introduced two ceramic techniques to Europe: glazingCeramic glazeGlaze is a layer or coating of a vitreous substance which has been fired to fuse to a ceramic object to color, decorate, strengthen or waterproof it.-Use:...

with an opaqueOpacity (optics)Opacity is the measure of impenetrability to electromagnetic or other kinds of radiation, especially visible light. In radiative transfer, it describes the absorption and scattering of radiation in a medium, such as a plasma, dielectric, shielding material, glass, etc...

white tin-glaze, and painting in metallic lusters. Hispano-Moresque ware was distinguished from the pottery of ChristendomChristendomChristendom, or the Christian world, has several meanings. In a cultural sense it refers to the worldwide community of Christians, adherents of Christianity...

by the Islamic character of its decoration. - Iznik potteryIznik potteryİznik pottery, named after the town in western Anatolia where it was made, is highly decorated ceramics that was produced between the late 15th and 17th centuries....

: Produced in OttomanOttoman EmpireThe Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

TurkeyTurkeyTurkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

as early as the 15th century AD It consists of a body, slipSlip (ceramics)A slip is a suspension in water of clay and/or other materials used in the production of ceramic ware. Deflocculant, such as sodium silicate, can be added to the slip to disperse the raw material particles...

, and glaze, where the body and glaze are "quartz-frit." The "frits" in both cases "are unusual in that they contain lead oxide as well as sodaSodium oxideSodium oxide is a chemical compound with the formula Na2O. It is used in ceramics and glasses, though not in a raw form. Treatment with water affords sodium hydroxide....

"; the lead oxide would help reduce the thermal expansion coefficient of the ceramic. Microscopic analysis reveals that the material that has been labeled "frit" is "interstitial glass" which serves to connect the quartz particles. - LusterwareLusterwareLusterware or Lustreware is a type of pottery or porcelain with a metallic glaze that gives the effect of iridescence, produced by metallic oxides in an overglaze finish, which is given a second firing at a lower temperature in a "muffle kiln", reduction kiln, which excludes oxygen.The first use...

: Lustre glazes were applied to pottery in MesopotamiaMesopotamiaMesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

in the 9th century; the technique soon became popular in PersiaHistory of IranThe history of Iran has been intertwined with the history of a larger historical region, comprising the area from the Danube River in the west to the Indus River and Jaxartes in the east and from the Caucasus, Caspian Sea, and Aral Sea in the north to the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman and Egypt...

and SyriaSyriaSyria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

. Lusterware was later produced in Egypt during the FatimidFatimidThe Fatimid Islamic Caliphate or al-Fāṭimiyyūn was a Berber Shia Muslim caliphate first centered in Tunisia and later in Egypt that ruled over varying areas of the Maghreb, Sudan, Sicily, the Levant, and Hijaz from 5 January 909 to 1171.The caliphate was ruled by the Fatimids, who established the...

caliphate in the 10th-12th centuries. While the production of lusterware continued in the Middle East, it spread to Europe—first to Al-AndalusAl-AndalusAl-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

, notably at MálagaMálagaMálaga is a city and a municipality in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia, Spain. With a population of 568,507 in 2010, it is the second most populous city of Andalusia and the sixth largest in Spain. This is the southernmost large city in Europe...

, and then to ItalyHistory of Islam in southern ItalyThe history of Islam in southern Italy begins with the Islamic conquest and subsequent rule of Sicily and Malta, a process that started in the 9th century. Islamic rule over Sicily was effective from 902, and the complete rule of the island lasted from 965 until 1061...

, where it was used to enhance maiolicaMaiolicaMaiolica is Italian tin-glazed pottery dating from the Renaissance. It is decorated in bright colours on a white background, frequently depicting historical and legendary scenes.-Name:...

. - Stonepaste ceramicStonewareStoneware is a vitreous or semi-vitreous ceramic ware with a fine texture. Stoneware is made from clay that is then fired in a kiln, whether by an artisan to make homeware, or in an industrial kiln for mass-produced or specialty products...

: Invented in 9th-century Iraq, it was a vitreous or semivitreous ceramic ware of fine texture, made primarily from non-refactory fire clay. - Tin-glazingTin-glazingTin-glazing is the process of giving ceramic items a tin-based glaze which is white, glossy and opaque, normally applied to red or buff earthenware. The opacity and whiteness of tin glaze make it valued by its ability to decorate with colour....

: The tin-glazing of ceramics was invented by Muslim potters in 8th-century BasraBasraBasra is the capital of Basra Governorate, in southern Iraq near Kuwait and Iran. It had an estimated population of two million as of 2009...

, Iraq. The first examples of this technique can be found as blue-painted ware in 8th-century Basra. The oldest fragments found to-date were excavated from the palace of SamarraSamarraSāmarrā is a city in Iraq. It stands on the east bank of the Tigris in the Salah ad-Din Governorate, north of Baghdad and, in 2003, had an estimated population of 348,700....

about fifty miles north of Baghdad.

Other

- Attempt at glidingGlider aircraftGlider aircraft are heavier-than-air craft that are supported in flight by the dynamic reaction of the air against their lifting surfaces, and whose free flight does not depend on an engine. Mostly these types of aircraft are intended for routine operation without engines, though engine failure can...

: According to the 17th century historian Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari, Abbas Ibn FirnasAbbas Ibn FirnasAbbas Ibn Firnas , also known as Abbas Qasim Ibn Firnas and عباس بن فرناس , was a Muslim Andalusian polymath: an inventor, engineer, aviator, physician, Arabic poet, and Andalusian musician. Of Berber descent, he was born in Izn-Rand Onda, Al-Andalus , and lived in the Emirate of Córdoba...

of Islamic Spain made in 875 the first − unsuccessful − attempt at a heavier-than-air glider flight in aviation historyAviation historyThe history of aviation has extended over more than two thousand years from the earliest attempts in kites and gliders to powered heavier-than-air, supersonic and hypersonic flight.The first form of man-made flying objects were kites...

. It may have inspired the attempt by Eilmer of MalmesburyEilmer of MalmesburyEilmer of Malmesbury was an 11th-century English Benedictine monk best known for his early attempt at a gliding flight using wings.- Life :...

between 1000 and 1010 in EnglandEnglandEngland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, recorded by the medieval historian William of MalmesburyWilliam of MalmesburyWilliam of Malmesbury was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. C. Warren Hollister so ranks him among the most talented generation of writers of history since Bede, "a gifted historical scholar and an omnivorous reader, impressively well versed in the literature of classical,...

in about 1125, although there is no evidence that the earlier recorded event in Anglo-Saxon England took place with foreign stimulus. - CoffeeCoffeeCoffee is a brewed beverage with a dark,init brooo acidic flavor prepared from the roasted seeds of the coffee plant, colloquially called coffee beans. The beans are found in coffee cherries, which grow on trees cultivated in over 70 countries, primarily in equatorial Latin America, Southeast Asia,...

: The earliest credible evidence of either coffee drinking or knowledge of the coffee tree appears in the middle of the 15th century, in the Sufi monasteries of the YemenYemenThe Republic of Yemen , commonly known as Yemen , is a country located in the Middle East, occupying the southwestern to southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, the Red Sea to the west, and Oman to the east....

in southern Arabia. It was in Yemen that coffee beans were first roasted and brewed as they are today. From Mocha, coffee spread to EgyptEgyptEgypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

and North Africa, and by the 16th century, it had reached the rest of the Middle East, Persia and TurkeyTurkeyTurkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

. From the Muslim worldMuslim worldThe term Muslim world has several meanings. In a religious sense, it refers to those who adhere to the teachings of Islam, referred to as Muslims. In a cultural sense, it refers to Islamic civilization, inclusive of non-Muslims living in that civilization...

, coffee drinking spread to Italy, then to the rest of Europe, and coffee plants were transported by the Dutch to the East IndiesEast IndiesEast Indies is a term used by Europeans from the 16th century onwards to identify what is now known as Indian subcontinent or South Asia, Southeastern Asia, and the islands of Oceania, including the Malay Archipelago and the Philippines...

and to the Americas. - MadrasahMadrasahMadrasah is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, whether secular or religious...

: The earliest mosque schools were the Madrasa of Al-Karaouine in Fez, Morocco, (founded 859) and the Al-Azhar in Cairo, Egypt (founded around 970).

See also

- Islamic Golden AgeIslamic Golden AgeDuring the Islamic Golden Age philosophers, scientists and engineers of the Islamic world contributed enormously to technology and culture, both by preserving earlier traditions and by adding their own inventions and innovations...

- Science in medieval Islam

- Timeline of science and engineering in the Islamic world