Impalement

Encyclopedia

Impalement is the traumatic penetration of an organism by an elongated foreign object such as a stake, pole, or spear, and this usually implies complete perforation of the central mass of the impaled body. While the term may be used in reference to an unintentional accident, it is more frequently used in reference to the deliberate act as a method of torture

and execution.

and execution, involves the body of a person being pierced with a long stake. The penetration could be through the sides, through the rectum

, through the vagina

, or through the mouth. This method leads to a painful death, sometimes taking days. When the impaling instrument was inserted into a lower orifice, it was necessary to secure the victim in the prone position

; the stake would then be held in place by one of the executioners, while another would hammer the stake deeper using a sledgehammer

. The stake was then planted in the ground, and the impaled victim hoisted up to a vertical position, where the victim would be left to die

.

In some forms of impalement, the stake would be inserted so as to avoid immediate death and would function as a plug to prevent blood loss. After preparation of the victim, perhaps including public torture and rape, the victim was stripped, and an incision was made in the perineum between the genitals and rectum. A stout pole with a blunt end was inserted. A blunt end would push vital organs to the side, greatly slowing death.

The pole would often come out of the body at the top of the sternum and be placed against the lower jaw so that the victim would not slide farther down the pole. Often, the victim was hoisted into the air after partial impalement. Gravity and the victim's own struggles would cause him to slide down the pole.

, such as the Neo-Assyrian empire, is evidenced by carvings and statues from the ancient Near East.

, or for people who had exhibited cowardice.

The French occupiers of Egypt

resorted to this method of execution towards Suleiman al-Halabi

, the Syrian Kurdish student who assassinated General Jean Baptiste Kléber

. This is the only instance of impalement in French justice, and was ordered in respect of local custom.

chief Caupolican

suffered this death as a prisoner during the Spanish conquest of Chile

. The method used was to make him sit on a stake while his wife was forced to watch. In 1578, the chief Juan de Lebú

would be executed by the same manner.

leaders during the Age of Warring States. Early in 1561, the allied forces of Tokugawa Ieyasu

and Oda Nobunaga

defeated the army of the Imagawa clan

in western Mikawa province

, encouraging the Saigo clan of east Mikawa, already chafing under Imagawa control, to defect to Ieyasu's command. Incensed at the rebellious Saigo clan, Imagawa Ujizane

entered the castle-town of Imabashi

, arrested Saigo Masayoshi and twelve others, and had them vertically impaled before the gate of Ryuden Temple, near Yoshida Castle. The deterrent had no effect, and by 1570, the Imagawa clan was stripped of its power.

It has been alleged that Japanese soldiers during World War II

inflicted "bamboo torture

" upon prisoners of war. The victim was supposedly tied securely in place above a young bamboo shoot. Over several days, the sharp, fast growing shoot would first puncture, then completely penetrate the victim's body, eventually emerging through the other side.

Adat

law, the traditional punishment for adultery before the modern age was that of impalement, known in Malay as Hukum Sula. A pole was inserted through the anus

and pushed up to pierce the heart or lungs of the condemned, the pole thereupon being hoisted and inserted into the ground.

region, where it was known as Shul (Bengali: শূল) and in ancient Tamilnadu, in present-day India

, where it was referred to as Kazhuvetram. Impalement was the usual sentence for the crime of treason against the king. A form of impalement existed in medieval Kerala

as a method of execution.

of the late 1960s, one account alleges that a village headman in South Vietnam

who cooperated in some way with the South Vietnamese Army

or with U.S. soldiers might have been impaled by local Viet Cong as a form of punishment for alleged collaboration. The method of impalement was alleged to have been the insertion of a sharpened stake through the anus; the stake was then supposedly planted vertically in the ground in view of his village. The victim was allegedly tortured and humiliated by complete castration

, with the amputated genitalia

being forced into his mouth. Another account alleges that the pregnant wife of a village headman was vertically impaled. There is also an allegation from the Vietnam War of coronal

cranial impalement. In this case, a bamboo

stake was supposedly thrust into the victim's ear and driven though the head until it emerged from the opposite ear opening. The act was allegedly perpetrated on three children of a village chief near Da Nang

.

Impalement and other methods of torture were intended to intimidate civilian peasants at a local level into cooperating with the Viet Cong or discourage them from cooperating with the South Vietnamese Army or its allies. The main culprits for the use of impalement appear to be members of the Viet Cong of South Vietnam. No allegations have been made against soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), nor is there any evidence that either the NVA or the government in Hanoi

ever condoned its use.

s victims and anyone killed during the commission of a crime were punished post mortem with impalement, in much the same way as a vampire

was supposed to be treated. The law designated these deaths as felo de se

(Felony against the Self) and declared the dead person's property forfeit to the Crown. The body was buried at a secret and unconsecrated location at night and a stake was driven through the corpse's heart. The burial location was usually at a crossroads

or at the foot of a gallows

or gibbet

; no mourners nor minister were permitted to attend. This was done to inflict disgrace on what was seen as a shameful act, and to prevent the decedent's spirit from haunting the living.

During the reign of King Henry I, one of his enemies, Robert of Belleme, noted for his cruelty, preferred to torture his prisoners to death, rather than ransom them, as was customary at the time. Among other forms of punishment, Belleme was noted for his fondness of impalement, though he tended to use meat hooks rather than stakes. He died a prisoner of Henry I at Wareham

.

During the Wars of the Roses

, John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester

, having witnessed this form of execution in Vlad the Impaler's Wallachia, notably had thirty men, found guilty of rebellion against King Edward IV, hanged, castrated, then beheaded at Southampton. Following the execution, the bodies were stripped naked and hung by their feet from gibbets on the sea front. The heads were impaled on stakes, and the stakes were then driven into the rectum of the corpse to which the head belonged; with the amputated genitalia stuffed into the mouth. Despite the use of judicial torture at the time, Tiptoft's act aroused dismay and horror, and he was denounced for his cruelty. When King Henry VI regained the throne for a brief period (1470–1471), Tiptoft was captured and beheaded.

" could also refer to impalement. This derives in part because the term for the one portion of a cross is synonymous with the term for a stake, so that when mentioned in historical sources without specific context, the exact method of execution, whether crucifixion or impalement, can be unclear.

During the 15th century, Vlad III

During the 15th century, Vlad III

, Prince of Wallachia

, is credited as the first notable figure to prefer this method of execution during the late medieval period, and became so notorious for its liberal employment that among his several nicknames he was known as Vlad the Impaler. After being orphaned, betrayed, forced into exile and pursued by his enemies, he retook control of Wallachia in 1456. He dealt harshly with his enemies, especially those who had betrayed his family in the past, or had profited from the misfortunes of Wallachia. Though a variety of methods was employed, he has been most associated with his use of impalement. The liberal use of capital punishment was eventually extended to Saxon settlers, members of a rival clan, and criminals in his domain, whether they were members of the boyar

nobility or peasants, and eventually to any among his subjects that displeased him. Following the multiple campaigns against the invading Ottoman Turks

, Vlad would never show mercy to his prisoners of war. The road to the capital of Wallachia eventually became inundated in a "forest" of 20,000 impaled and decaying corpses, and it is reported that an invading army of Turks turned back after encountering thousands of impaled corpses along the Danube River. Woodblock

prints from the era portray his victims impaled from either the frontal or the dorsal

aspect, but not vertically.

used impalement during the last Siege of Constantinople

in 1453, though possibly earlier. Ottoman soldiers and authorities would later use impalement quite frequently in the same region during the 18th and 19th centuries, especially during some of the more brutal repressions of nationalistic movements, or reprisals following insurrections in Greece and other countries of Southeast Europe

.

During the Ottoman occupation of Greece

, impalement became an important tool of psychological warfare

, intended to put terror into the peasant population. By the 18th century, Greek bandits turned guerrilla insurgents (known as klepht

s) became an increasing annoyance to the Ottoman government. Captured klephts were often impaled, as were peasants that harbored or aided them. Victims were publicly impaled and placed at highly visible points, and had the intended effect on many villages who not only refused to help the klephts, but would even turn them in to the authorities. The Ottomans engaged in active campaigns to capture these insurgents in 1805 and 1806, and were able to enlist Greek villagers, eager to avoid the stake, in the hunt for their outlaw countrymen.

During the Serbian Revolution

(1804–1835) against the Ottoman Empire, about 200 Serbians were impaled in Belgrade

in 1814, as punishment for a riot in the aftermath of Hadži Prodan's Revolt.

The agony of impalement was eventually compounded with being set over a fire, the impaling stake acting as a spit

, so that the impaled victim might be roasted alive. Among other atrocities, Ali Pasha

, an Albania

n-born Ottoman noble who ruled Ioannina

, had rebels, criminals, and even the descendants of those who had wronged him or his family in the past, impaled and roasted alive. During the Greek War of Independence

(1821–1832), Athanasios Diakos

, a klepht and later a rebel military commander, was captured after the Battle of Alamana

(1821), near Thermopylae

, and after refusing to convert to Islam

and join the Ottoman army, he was impaled, roasted over a fire, and died after three days. Others were treated in a similar manner. Diakos became a martyr

for a Greek independence and was later honored as a national hero.

in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

.

During the 17th century, impalement was used by the Swedish

forces in the Second Northern War

(1655–1660) and the Scanian War

(1675–1679). It was employed in particular as a death penalty for members of the pro-Danish

guerrilla resistance known as Snapphane

s, however it is uncertain if live impalement was typical, or if the victim was impaled after execution for public display.

, or prevent a corpse from rising as a vampire, was to drive a wooden stake through the heart before interment. In one story, a Croatia

n peasant named Jure Grando

died and was buried in 1656. It was believed that he returned as a vampire, and at least one villager tried to drive a stake through his heart, but failed in the attempt. Finally, in 1672, the corpse was decapitated

, and the vampire terror was put to rest. The association between vampires and impalement has carried on into 20th century cinema, and it has been portrayed in numerous vampire movies, such as the 1987 American film The Lost Boys

and 1996 film From Dusk till Dawn

.

The 1980 Italian film, Cannibal Holocaust

, directed by Ruggero Deodato

, graphically depicts impalement. The story follows a rescue party searching for a missing documentary film crew in the Amazon Rainforest

. The film's depiction of indigenous tribes, death of animals on set, and the graphic violence (notably the impalement scene) brought on a great deal of controversy, legal investigations, boycotts and protests by concerned social groups, bans in many countries (some of which are still in effect), and heavy censorship in countries where it has not been banned. The impalement scene was so realistic, that Deodato was charged with murder at one point. Deodato had to produce evidence that the "impaled" actress was alive in the aftermath of the scene, and had to further explain how the special effect

was done: the actress sat on a bicycle seat

mounted to a pole while she looked up and held a short stake of balsa

wood in her mouth. The charges were dropped.

A graphic and historically accurate description of the vertical impalement of a Serbian rebel by Ottoman authorities can be found in Ivo Andrić

's novel The Bridge on the Drina

. Andrić was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for the whole of his literary contribution, though this novel was the magnum opus.

In stage magic, the illusion of impalement

is a popular feat of magic that appears to be an act of impalement.

s, atlatl

darts

, or arrow

s, though impalement in these cases is incidental to the kill, and the animal is usually despatched as quickly as possible. In southern Asia, tiger

s have in the past been caught using trapping pit

s with sharpened stakes thrust into the floor. The pit was set on a trail that the tiger used and camouflaged. When the tiger fell into the pit, it would be impaled on the stakes. This method of catching a tiger was simple, effective, and used minimal labor cost; however, it severely damaged the tiger's skin, thus it was probably only put in use against persistent man-eater

s.

In arthropodology, and especially its subfield entomology

, captured arthropod

s and insect

s are routinely killed and prepared for mounted display, whereby they are impaled by a pin to a portable surface, such as a board or display box made of wood, cork, cardboard, or synthetic foam. The pins used are typically 38mm long and 0.46mm in diameter, though smaller and larger pins are available. Impaled specimens of insects, spiders, butterflies, moths, scorpions, and similar organisms are collected, preserved, and displayed in this manner in private, academic, and museum collections around the world.

Torture

Torture is the act of inflicting severe pain as a means of punishment, revenge, forcing information or a confession, or simply as an act of cruelty. Throughout history, torture has often been used as a method of political re-education, interrogation, punishment, and coercion...

and execution.

Methods

Impalement, as a method of tortureTorture

Torture is the act of inflicting severe pain as a means of punishment, revenge, forcing information or a confession, or simply as an act of cruelty. Throughout history, torture has often been used as a method of political re-education, interrogation, punishment, and coercion...

and execution, involves the body of a person being pierced with a long stake. The penetration could be through the sides, through the rectum

Rectum

The rectum is the final straight portion of the large intestine in some mammals, and the gut in others, terminating in the anus. The human rectum is about 12 cm long...

, through the vagina

Vagina

The vagina is a fibromuscular tubular tract leading from the uterus to the exterior of the body in female placental mammals and marsupials, or to the cloaca in female birds, monotremes, and some reptiles. Female insects and other invertebrates also have a vagina, which is the terminal part of the...

, or through the mouth. This method leads to a painful death, sometimes taking days. When the impaling instrument was inserted into a lower orifice, it was necessary to secure the victim in the prone position

Prone position

The term means to lie on bed or ground in a position with chest downwards and back upwards.-Etymology :The word "prone," meaning "naturally inclined to something, apt, liable," has been recorded in English since 1382; the meaning "lying face-down" was first recorded in 1578, but is also referred to...

; the stake would then be held in place by one of the executioners, while another would hammer the stake deeper using a sledgehammer

Sledgehammer

A sledgehammer is a tool consisting of a large, flat head attached to a lever . The head is typically made of metal. The sledgehammer can apply more impulse than other hammers, due to its large size. Along with the mallet, it shares the ability to distribute force over a wide area...

. The stake was then planted in the ground, and the impaled victim hoisted up to a vertical position, where the victim would be left to die

Death

Death is the permanent termination of the biological functions that sustain a living organism. Phenomena which commonly bring about death include old age, predation, malnutrition, disease, and accidents or trauma resulting in terminal injury....

.

In some forms of impalement, the stake would be inserted so as to avoid immediate death and would function as a plug to prevent blood loss. After preparation of the victim, perhaps including public torture and rape, the victim was stripped, and an incision was made in the perineum between the genitals and rectum. A stout pole with a blunt end was inserted. A blunt end would push vital organs to the side, greatly slowing death.

The pole would often come out of the body at the top of the sternum and be placed against the lower jaw so that the victim would not slide farther down the pole. Often, the victim was hoisted into the air after partial impalement. Gravity and the victim's own struggles would cause him to slide down the pole.

History

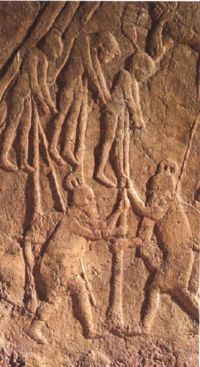

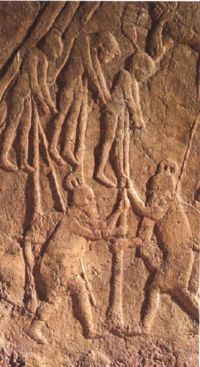

The earliest known use of impalement as a form of execution occurred in civilizations of the Ancient Near EastAncient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia , ancient Egypt, ancient Iran The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia...

, such as the Neo-Assyrian empire, is evidenced by carvings and statues from the ancient Near East.

Africa

The Zulu of South Africa used impalement (ukujoja) as a form of punishment for soldiers who had failed in the execution of their duty, for people accused of witchcraftWitchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

, or for people who had exhibited cowardice.

The French occupiers of Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

resorted to this method of execution towards Suleiman al-Halabi

Suleiman al-Halabi

Suleiman al-Halabi, also known as Soleyman El-Halaby , was a Syrian student who assassinated French general Jean Baptiste Kléber. He was tortured by burning his hand to the bone before being executed by impalement.-Early life:...

, the Syrian Kurdish student who assassinated General Jean Baptiste Kléber

Jean Baptiste Kléber

Jean Baptiste Kléber was a French general during the French Revolutionary Wars. His military career started in Habsburg service, but his plebeian ancestry hindered his opportunities...

. This is the only instance of impalement in French justice, and was ordered in respect of local custom.

Americas

The AraucanianMapuche

The Mapuche are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina. They constitute a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who shared a common social, religious and economic structure, as well as a common linguistic heritage. Their influence extended...

chief Caupolican

Caupolican

Caupolicán was a Toqui, the military leader of the Mapuche people of Chile, that commanded their army during the first Mapuche rising against the Spanish conquistadors from 1553 to 1558....

suffered this death as a prisoner during the Spanish conquest of Chile

Conquest of Chile

The Conquest of Chile is a period in Chilean historiography that starts with the arrival of Pedro de Valdivia to Chile in 1541 and ends with the death of Martín García Óñez de Loyola, in the Battle of Curalaba in 1598 or alternatively with the Destruction of the Seven Cities. This was the period...

. The method used was to make him sit on a stake while his wife was forced to watch. In 1578, the chief Juan de Lebú

Juan de Lebú

Juan de Lebú was a Moluche cacique or Ulmen of the Lebu region, captured by the Spanish sometime before 1568. He was sent to Peru and the Spaniards had baptized him with the name of Juan. He returned in 1568, with the new Governor Melchor Bravo de Saravia. When he had the chance he escaped and...

would be executed by the same manner.

Japan

Impalement was only occasionally used by samuraiSamurai

is the term for the military nobility of pre-industrial Japan. According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning to wait upon or accompany a person in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau...

leaders during the Age of Warring States. Early in 1561, the allied forces of Tokugawa Ieyasu

Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan , which ruled from the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Ieyasu seized power in 1600, received appointment as shogun in 1603, abdicated from office in 1605, but...

and Oda Nobunaga

Oda Nobunaga

was the initiator of the unification of Japan under the shogunate in the late 16th century, which ruled Japan until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was also a major daimyo during the Sengoku period of Japanese history. His opus was continued, completed and finalized by his successors Toyotomi...

defeated the army of the Imagawa clan

Imagawa clan

The was a Japanese clan that claimed descent from Emperor Seiwa . It was a branch of the Minamoto clan by the Ashikaga clan.-Origins:Ashikaga Kuniuji, grandson of Ashikaga Yoshiuji, established himself in the 13th century at Imagawa and took its name.Imagawa Norikuni received from his cousin the...

in western Mikawa province

Mikawa Province

is an old province in the area that today forms the eastern half of Aichi Prefecture. It was sometimes called . Mikawa bordered on Owari, Mino, Shinano, and Tōtōmi Provinces....

, encouraging the Saigo clan of east Mikawa, already chafing under Imagawa control, to defect to Ieyasu's command. Incensed at the rebellious Saigo clan, Imagawa Ujizane

Imagawa Ujizane

was a Japanese daimyo who lived from the mid-Sengoku through early Edo periods. He was the son of Imagawa Yoshimoto, and the father of Imagawa Norimochi and Shinagawa Takahisa.-Early life:Ujizane was born in Sunpu; he was the eldest son of Imagawa Yoshimoto...

entered the castle-town of Imabashi

Toyohashi, Aichi

is a city located in Aichi Prefecture, Japan.The city was founded on August 1, 1906. As of January 1, 2010, the city has an estimated population of 383,691 and a density of 1,468.62 persons per km². The total area is . By size, Toyohashi was Aichi Prefecture's second-largest city until March 31,...

, arrested Saigo Masayoshi and twelve others, and had them vertically impaled before the gate of Ryuden Temple, near Yoshida Castle. The deterrent had no effect, and by 1570, the Imagawa clan was stripped of its power.

It has been alleged that Japanese soldiers during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

inflicted "bamboo torture

Bamboo torture

Bamboo torture is a form of torture where a bamboo shoot is grown through the body of a victim. Bamboo torture was allegedly used in East and South Asia. Accounts accuse Japanese soldiers of practicing the torture technique during World War II....

" upon prisoners of war. The victim was supposedly tied securely in place above a young bamboo shoot. Over several days, the sharp, fast growing shoot would first puncture, then completely penetrate the victim's body, eventually emerging through the other side.

Malay Islands

In MalayMalay people

Malays are an ethnic group of Austronesian people predominantly inhabiting the Malay Peninsula, including the southernmost parts of Thailand, the east coast of Sumatra, the coast of Borneo, and the smaller islands which lie between these locations...

Adat

Adat

Adat in Indonesian-Malay culture is the set of cultural norms, values, customs and practices found among specific ethnic groups in Indonesia, the southern Philippines and Malaysia...

law, the traditional punishment for adultery before the modern age was that of impalement, known in Malay as Hukum Sula. A pole was inserted through the anus

Anus

The anus is an opening at the opposite end of an animal's digestive tract from the mouth. Its function is to control the expulsion of feces, unwanted semi-solid matter produced during digestion, which, depending on the type of animal, may be one or more of: matter which the animal cannot digest,...

and pushed up to pierce the heart or lungs of the condemned, the pole thereupon being hoisted and inserted into the ground.

Southern Asia

Impalement is known to have been employed in several regions of southern Asia, such as in the BengalBengal

Bengal is a historical and geographical region in the northeast region of the Indian Subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. Today, it is mainly divided between the sovereign land of People's Republic of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, although some regions of the previous...

region, where it was known as Shul (Bengali: শূল) and in ancient Tamilnadu, in present-day India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

, where it was referred to as Kazhuvetram. Impalement was the usual sentence for the crime of treason against the king. A form of impalement existed in medieval Kerala

Kerala

or Keralam is an Indian state located on the Malabar coast of south-west India. It was created on 1 November 1956 by the States Reorganisation Act by combining various Malayalam speaking regions....

as a method of execution.

Vietnam

During the Vietnam WarVietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

of the late 1960s, one account alleges that a village headman in South Vietnam

South Vietnam

South Vietnam was a state which governed southern Vietnam until 1975. It received international recognition in 1950 as the "State of Vietnam" and later as the "Republic of Vietnam" . Its capital was Saigon...

who cooperated in some way with the South Vietnamese Army

Army of the Republic of Vietnam

The Army of the Republic of Viet Nam , sometimes parsimoniously referred to as the South Vietnamese Army , was the land-based military forces of the Republic of Vietnam , which existed from October 26, 1955 until the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975...

or with U.S. soldiers might have been impaled by local Viet Cong as a form of punishment for alleged collaboration. The method of impalement was alleged to have been the insertion of a sharpened stake through the anus; the stake was then supposedly planted vertically in the ground in view of his village. The victim was allegedly tortured and humiliated by complete castration

Castration

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which a male loses the functions of the testicles or a female loses the functions of the ovaries.-Humans:...

, with the amputated genitalia

Male reproductive system (human)

The human male reproductive system consists of a number of sex organs that are a part of the human reproductive process...

being forced into his mouth. Another account alleges that the pregnant wife of a village headman was vertically impaled. There is also an allegation from the Vietnam War of coronal

Coronal

Coronal may refer to:* anything relating to a corona* Coronal plane, an anatomical term of location* The coronal direction on a tooth* Coronal consonant, a consonant that is articulated with the front part of the tongue...

cranial impalement. In this case, a bamboo

Bamboo

Bamboo is a group of perennial evergreens in the true grass family Poaceae, subfamily Bambusoideae, tribe Bambuseae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family....

stake was supposedly thrust into the victim's ear and driven though the head until it emerged from the opposite ear opening. The act was allegedly perpetrated on three children of a village chief near Da Nang

Da Nang

Đà Nẵng , occasionally Danang, is a major port city in the South Central Coast of Vietnam, on the coast of the South China Sea at the mouth of the Han River. It is the commercial and educational center of Central Vietnam; its well-sheltered, easily accessible port and its location on the path of...

.

Impalement and other methods of torture were intended to intimidate civilian peasants at a local level into cooperating with the Viet Cong or discourage them from cooperating with the South Vietnamese Army or its allies. The main culprits for the use of impalement appear to be members of the Viet Cong of South Vietnam. No allegations have been made against soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), nor is there any evidence that either the NVA or the government in Hanoi

Hanoi

Hanoi , is the capital of Vietnam and the country's second largest city. Its population in 2009 was estimated at 2.6 million for urban districts, 6.5 million for the metropolitan jurisdiction. From 1010 until 1802, it was the most important political centre of Vietnam...

ever condoned its use.

England

Until the early nineteenth century, suicideSuicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Suicide is often committed out of despair or attributed to some underlying mental disorder, such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, alcoholism, or drug abuse...

s victims and anyone killed during the commission of a crime were punished post mortem with impalement, in much the same way as a vampire

Vampire

Vampires are mythological or folkloric beings who subsist by feeding on the life essence of living creatures, regardless of whether they are undead or a living person...

was supposed to be treated. The law designated these deaths as felo de se

Felo de se

Felo de se, Latin for "felon of himself", is an archaic legal term meaning suicide. In early English common law, an adult who committed suicide was literally a felon, and the crime was punishable by forfeiture of property to the king and what was considered a shameful burial – typically with...

(Felony against the Self) and declared the dead person's property forfeit to the Crown. The body was buried at a secret and unconsecrated location at night and a stake was driven through the corpse's heart. The burial location was usually at a crossroads

Crossroads

Crossroads, or crossroad, or cross road may refer to:* Intersection , a road junction where two or more roads meet-Music:* "Cross Road Blues", a blues song by Robert Johnson, later recorded as "Crossroads" by many other musicians...

or at the foot of a gallows

Gallows

A gallows is a frame, typically wooden, used for execution by hanging, or by means to torture before execution, as was used when being hanged, drawn and quartered...

or gibbet

Gibbet

A gibbet is a gallows-type structure from which the dead bodies of executed criminals were hung on public display to deter other existing or potential criminals. In earlier times, up to the late 17th century, live gibbeting also took place, in which the criminal was placed alive in a metal cage...

; no mourners nor minister were permitted to attend. This was done to inflict disgrace on what was seen as a shameful act, and to prevent the decedent's spirit from haunting the living.

During the reign of King Henry I, one of his enemies, Robert of Belleme, noted for his cruelty, preferred to torture his prisoners to death, rather than ransom them, as was customary at the time. Among other forms of punishment, Belleme was noted for his fondness of impalement, though he tended to use meat hooks rather than stakes. He died a prisoner of Henry I at Wareham

Wareham, Dorset

Wareham is an historic market town and, under the name Wareham Town, a civil parish, in the English county of Dorset. The town is situated on the River Frome eight miles southwest of Poole.-Situation and geography:...

.

During the Wars of the Roses

Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses were a series of dynastic civil wars for the throne of England fought between supporters of two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: the houses of Lancaster and York...

, John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester

John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester

John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester KG , English nobleman and scholar, was the son of John Tiptoft, 1st Baron Tiptoft and Joyce Cherleton, co-heiress of Edward Charleton, 5th Baron Cherleton. He was also known as the Butcher of England...

, having witnessed this form of execution in Vlad the Impaler's Wallachia, notably had thirty men, found guilty of rebellion against King Edward IV, hanged, castrated, then beheaded at Southampton. Following the execution, the bodies were stripped naked and hung by their feet from gibbets on the sea front. The heads were impaled on stakes, and the stakes were then driven into the rectum of the corpse to which the head belonged; with the amputated genitalia stuffed into the mouth. Despite the use of judicial torture at the time, Tiptoft's act aroused dismay and horror, and he was denounced for his cruelty. When King Henry VI regained the throne for a brief period (1470–1471), Tiptoft was captured and beheaded.

Roman Empire

In ancient Rome, the term "crucifixionCrucifixion

Crucifixion is an ancient method of painful execution in which the condemned person is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross and left to hang until dead...

" could also refer to impalement. This derives in part because the term for the one portion of a cross is synonymous with the term for a stake, so that when mentioned in historical sources without specific context, the exact method of execution, whether crucifixion or impalement, can be unclear.

Romania

Vlad III the Impaler

Vlad III, Prince of Wallachia , also known by his patronymic Dracula , and posthumously dubbed Vlad the Impaler , was a three-time Voivode of Wallachia, ruling mainly from 1456 to 1462, the period of the incipient Ottoman conquest of the Balkans...

, Prince of Wallachia

Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians...

, is credited as the first notable figure to prefer this method of execution during the late medieval period, and became so notorious for its liberal employment that among his several nicknames he was known as Vlad the Impaler. After being orphaned, betrayed, forced into exile and pursued by his enemies, he retook control of Wallachia in 1456. He dealt harshly with his enemies, especially those who had betrayed his family in the past, or had profited from the misfortunes of Wallachia. Though a variety of methods was employed, he has been most associated with his use of impalement. The liberal use of capital punishment was eventually extended to Saxon settlers, members of a rival clan, and criminals in his domain, whether they were members of the boyar

Boyar

A boyar, or bolyar , was a member of the highest rank of the feudal Moscovian, Kievan Rus'ian, Bulgarian, Wallachian, and Moldavian aristocracies, second only to the ruling princes , from the 10th century through the 17th century....

nobility or peasants, and eventually to any among his subjects that displeased him. Following the multiple campaigns against the invading Ottoman Turks

Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks were the Turkish-speaking population of the Ottoman Empire who formed the base of the state's military and ruling classes. Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks is scarce, but they take their Turkish name, Osmanlı , from the house of Osman I The Ottoman...

, Vlad would never show mercy to his prisoners of war. The road to the capital of Wallachia eventually became inundated in a "forest" of 20,000 impaled and decaying corpses, and it is reported that an invading army of Turks turned back after encountering thousands of impaled corpses along the Danube River. Woodblock

Woodcut

Woodcut—occasionally known as xylography—is a relief printing artistic technique in printmaking in which an image is carved into the surface of a block of wood, with the printing parts remaining level with the surface while the non-printing parts are removed, typically with gouges...

prints from the era portray his victims impaled from either the frontal or the dorsal

Dorsum (anatomy)

In anatomy, the dorsum is the upper side of animals that typically run, fly, or swim in a horizontal position, and the back side of animals that walk upright. In vertebrates the dorsum contains the backbone. The term dorsal refers to anatomical structures that are either situated toward or grow...

aspect, but not vertically.

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireOttoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

used impalement during the last Siege of Constantinople

Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire, which occurred after a siege by the Ottoman Empire, under the command of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, against the defending army commanded by Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI...

in 1453, though possibly earlier. Ottoman soldiers and authorities would later use impalement quite frequently in the same region during the 18th and 19th centuries, especially during some of the more brutal repressions of nationalistic movements, or reprisals following insurrections in Greece and other countries of Southeast Europe

Southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe is a relatively recent political designation for the states of the Balkans. Writers such as Maria Todorova and Vesna Goldsworthy have suggested the use of the term Southeastern Europe to replace the word Balkans for the region, to minimize potential...

.

During the Ottoman occupation of Greece

Ottoman Greece

Most of Greece gradually became part of the Ottoman Empire from the 15th century until its declaration of independence in 1821, a historical period also known as Tourkokratia ....

, impalement became an important tool of psychological warfare

Psychological warfare

Psychological warfare , or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations , have been known by many other names or terms, including Psy Ops, Political Warfare, “Hearts and Minds,” and Propaganda...

, intended to put terror into the peasant population. By the 18th century, Greek bandits turned guerrilla insurgents (known as klepht

Klepht

Klephts were self-appointed armatoloi, anti-Ottoman insurgents, and warlike mountain-folk who lived in the countryside when Greece was a part of the Ottoman Empire...

s) became an increasing annoyance to the Ottoman government. Captured klephts were often impaled, as were peasants that harbored or aided them. Victims were publicly impaled and placed at highly visible points, and had the intended effect on many villages who not only refused to help the klephts, but would even turn them in to the authorities. The Ottomans engaged in active campaigns to capture these insurgents in 1805 and 1806, and were able to enlist Greek villagers, eager to avoid the stake, in the hunt for their outlaw countrymen.

During the Serbian Revolution

Serbian revolution

Serbian revolution or Revolutionary Serbia refers to the national and social revolution of the Serbian people taking place between 1804 and 1835, during which this territory evolved from an Ottoman province into a constitutional monarchy and a modern nation-state...

(1804–1835) against the Ottoman Empire, about 200 Serbians were impaled in Belgrade

Belgrade

Belgrade is the capital and largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers, where the Pannonian Plain meets the Balkans. According to official results of Census 2011, the city has a population of 1,639,121. It is one of the 15 largest cities in Europe...

in 1814, as punishment for a riot in the aftermath of Hadži Prodan's Revolt.

The agony of impalement was eventually compounded with being set over a fire, the impaling stake acting as a spit

Rotisserie

Rotisserie is a style of roasting where meat is skewered on a spit - a long solid rod used to hold food while it is being cooked over a fire in a fireplace or over a campfire, or roasted in an oven. This method is generally used for cooking large joints of meat or entire animals, such as pigs,...

, so that the impaled victim might be roasted alive. Among other atrocities, Ali Pasha

Ali Pasha

Ali Pasha of Tepelena or of Yannina, surnamed Aslan, "the Lion", or the "Lion of Yannina", Ali Pashë Tepelena was an Ottoman Albanian ruler of the western part of Rumelia, the Ottoman Empire's European territory which was also called Pashalik of Yanina. His court was in Ioannina...

, an Albania

Albania

Albania , officially known as the Republic of Albania , is a country in Southeastern Europe, in the Balkans region. It is bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast, the Republic of Macedonia to the east and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea...

n-born Ottoman noble who ruled Ioannina

Ioannina

Ioannina , often called Jannena within Greece, is the largest city of Epirus, north-western Greece, with a population of 70,203 . It lies at an elevation of approximately 500 meters above sea level, on the western shore of lake Pamvotis . It is located within the Ioannina municipality, and is the...

, had rebels, criminals, and even the descendants of those who had wronged him or his family in the past, impaled and roasted alive. During the Greek War of Independence

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution was a successful war of independence waged by the Greek revolutionaries between...

(1821–1832), Athanasios Diakos

Athanasios Diakos

Athanasios Diakos , a Greek military commander during the Greek War of Independence and a national hero, was born Athanasios Nikolaos Massavetas in the village of Ano Mousounitsa, Phocis.-Early life:...

, a klepht and later a rebel military commander, was captured after the Battle of Alamana

Battle of Alamana

The Battle of Alamana was fought between the Greeks and the Ottoman Empire during the Greek War of Independence on April 22nd, 1821.-Battle:...

(1821), near Thermopylae

Thermopylae

Thermopylae is a location in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur springs. "Hot gates" is also "the place of hot springs and cavernous entrances to Hades"....

, and after refusing to convert to Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

and join the Ottoman army, he was impaled, roasted over a fire, and died after three days. Others were treated in a similar manner. Diakos became a martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

for a Greek independence and was later honored as a national hero.

Other countries

Impalement was also used in other European countries, though to a more limited degree. From the 14th to the 18th century, impalement was a method of execution for high treasonHigh treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

.

During the 17th century, impalement was used by the Swedish

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

forces in the Second Northern War

Second Northern War

The Second Northern War was fought between Sweden and its adversaries the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth , Russia , Brandenburg-Prussia , the Habsburg Monarchy and Denmark–Norway...

(1655–1660) and the Scanian War

Scanian War

The Scanian War was a part of the Northern Wars involving the union of Denmark-Norway, Brandenburg and Sweden. It was fought mainly on Scanian soil, in the former Danish provinces along the border with Sweden and in Northern Germany...

(1675–1679). It was employed in particular as a death penalty for members of the pro-Danish

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

guerrilla resistance known as Snapphane

Snapphane

A snapphane was a member of a 17th century pro-Danish guerrilla organization that fought against the Swedes in the Second Northern and Scanian Wars, primarily in the former eastern Danish provinces which in the course of these wars became southern Sweden....

s, however it is uncertain if live impalement was typical, or if the victim was impaled after execution for public display.

Cultural references

In classic European folklore, it was believed that one method to "kill" a vampireVampire

Vampires are mythological or folkloric beings who subsist by feeding on the life essence of living creatures, regardless of whether they are undead or a living person...

, or prevent a corpse from rising as a vampire, was to drive a wooden stake through the heart before interment. In one story, a Croatia

Croatia

Croatia , officially the Republic of Croatia , is a unitary democratic parliamentary republic in Europe at the crossroads of the Mitteleuropa, the Balkans, and the Mediterranean. Its capital and largest city is Zagreb. The country is divided into 20 counties and the city of Zagreb. Croatia covers ...

n peasant named Jure Grando

Jure Grando

Jure Grando or Giure Grando was the first classical vampire to be mentioned in documented records. In his native Istria, which is in present day Croatia, he was referred to as a štrigon or štrigun, a local word for something resembling a vampire and a warlock.-Story:Jure Grando was a peasant who...

died and was buried in 1656. It was believed that he returned as a vampire, and at least one villager tried to drive a stake through his heart, but failed in the attempt. Finally, in 1672, the corpse was decapitated

Decapitation

Decapitation is the separation of the head from the body. Beheading typically refers to the act of intentional decapitation, e.g., as a means of murder or execution; it may be accomplished, for example, with an axe, sword, knife, wire, or by other more sophisticated means such as a guillotine...

, and the vampire terror was put to rest. The association between vampires and impalement has carried on into 20th century cinema, and it has been portrayed in numerous vampire movies, such as the 1987 American film The Lost Boys

The Lost Boys

The Lost Boys is a 1987 American teen comedy horror film directed by Joel Schumacher and starring Jason Patric, Corey Haim, Kiefer Sutherland, Jami Gertz, Corey Feldman, Dianne Wiest, Edward Herrmann, Alex Winter, Jamison Newlander, and Barnard Hughes....

and 1996 film From Dusk till Dawn

From Dusk Till Dawn

From Dusk till Dawn is a 1996 horror film directed by Robert Rodriguez and written by Quentin Tarantino. The movie stars Harvey Keitel, George Clooney, Quentin Tarantino and Juliette Lewis.-Plot:...

.

The 1980 Italian film, Cannibal Holocaust

Cannibal Holocaust

Cannibal Holocaust is a 1980 Italian horror film directed by Ruggero Deodato from a screenplay by Gianfranco Clerici. Filmed in the Amazon Rainforest and dealing with indigenous tribes, it was cast mostly with United States actors and filmed in English to achieve wider distribution...

, directed by Ruggero Deodato

Ruggero Deodato

Ruggero Deodato is an Italian film director and screen writer, best known for directing violent and gory horror films. Deodato is infamous for his 1980 film Cannibal Holocaust.- Biography :...

, graphically depicts impalement. The story follows a rescue party searching for a missing documentary film crew in the Amazon Rainforest

Amazon Rainforest

The Amazon Rainforest , also known in English as Amazonia or the Amazon Jungle, is a moist broadleaf forest that covers most of the Amazon Basin of South America...

. The film's depiction of indigenous tribes, death of animals on set, and the graphic violence (notably the impalement scene) brought on a great deal of controversy, legal investigations, boycotts and protests by concerned social groups, bans in many countries (some of which are still in effect), and heavy censorship in countries where it has not been banned. The impalement scene was so realistic, that Deodato was charged with murder at one point. Deodato had to produce evidence that the "impaled" actress was alive in the aftermath of the scene, and had to further explain how the special effect

Special effect

The illusions used in the film, television, theatre, or entertainment industries to simulate the imagined events in a story are traditionally called special effects ....

was done: the actress sat on a bicycle seat

Bicycle seat

A bicycle seat, unlike a bicycle saddle, is designed to support the rider's buttocks and back, usually in a semi-reclined position. Arthur Garford is credited with inventing the padded bicycle seat in 1892, and they are now usually found on recumbent bicycles.Bicycle seats come in three main...

mounted to a pole while she looked up and held a short stake of balsa

Balsa

Ochroma pyramidale, commonly known as the balsa tree , is a species of flowering plant in the mallow family, Malvaceae. It is a large, fast-growing tree that can grow up to tall. It is the source of balsa wood, a very lightweight material with many uses...

wood in her mouth. The charges were dropped.

A graphic and historically accurate description of the vertical impalement of a Serbian rebel by Ottoman authorities can be found in Ivo Andrić

Ivo Andric

Ivan "Ivo" Andrić was a Yugoslav novelist, short story writer, and the 1961 winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. His writings dealt mainly with life in his native Bosnia under the Ottoman Empire...

's novel The Bridge on the Drina

The Bridge on the Drina

The Bridge on the Drina , sometimes restyled as The Bridge Over the Drina, is a novel by Yugoslav writer Ivo Andrić. Andrić wrote the novel while living quietly in Belgrade during World War II, publishing it in 1945...

. Andrić was later awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for the whole of his literary contribution, though this novel was the magnum opus.

In stage magic, the illusion of impalement

Impaled (illusion)

Impaled is a classic stage illusion in which a performer appears to be impaled on or by a sword or pole. The name is most commonly associated with an illusion that was created by designer Ken Whitaker in the 1970s and which is sometimes also referred to as "Beyond Belief" or "Impaled Beyond...

is a popular feat of magic that appears to be an act of impalement.

Animals

The reviewed literature does not record any culturally sanctioned use of intentionally prolonged impalement, as punishment or utility, against live animals. Animals have been hunted with so-called "primitive weapons", such as spearSpear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head.The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with bamboo spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fastened to the shaft, such as flint, obsidian, iron, steel or...

s, atlatl

Atlatl

An atlatl or spear-thrower is a tool that uses leverage to achieve greater velocity in dart-throwing.It consists of a shaft with a cup or a spur at the end that supports and propels the butt of the dart. The atlatl is held in one hand, gripped near the end farthest from the cup...

darts

Dart (missile)

Darts are missile weapons, designed to fly such that a sharp, often weighted point will strike first. They can be distinguished from javelins by fletching and a shaft that is shorter and/or more flexible, and from arrows by the fact that they are not of the right length to use with a normal...

, or arrow

Arrow

An arrow is a shafted projectile that is shot with a bow. It predates recorded history and is common to most cultures.An arrow usually consists of a shaft with an arrowhead attached to the front end, with fletchings and a nock at the other.- History:...

s, though impalement in these cases is incidental to the kill, and the animal is usually despatched as quickly as possible. In southern Asia, tiger

Tiger

The tiger is the largest cat species, reaching a total body length of up to and weighing up to . Their most recognizable feature is a pattern of dark vertical stripes on reddish-orange fur with lighter underparts...

s have in the past been caught using trapping pit

Trapping pit

Trapping pits are deep pits dug into the ground, or built from stone, in order to trap animals.European rock drawings and cave paintings reveal that the elk and moose have been hunted since the stone age using trapping pits. In Northern Scandinavia one can still find remains of trapping pits used...

s with sharpened stakes thrust into the floor. The pit was set on a trail that the tiger used and camouflaged. When the tiger fell into the pit, it would be impaled on the stakes. This method of catching a tiger was simple, effective, and used minimal labor cost; however, it severely damaged the tiger's skin, thus it was probably only put in use against persistent man-eater

Man-eater

Man-eater is a colloquial term for an animal that preys upon humans. This does not include scavenging. Although human beings can be attacked by many kinds of animals, man-eaters are those that have incorporated human flesh into their usual diet...

s.

In arthropodology, and especially its subfield entomology

Entomology

Entomology is the scientific study of insects, a branch of arthropodology...

, captured arthropod

Arthropod

An arthropod is an invertebrate animal having an exoskeleton , a segmented body, and jointed appendages. Arthropods are members of the phylum Arthropoda , and include the insects, arachnids, crustaceans, and others...

s and insect

Insect

Insects are a class of living creatures within the arthropods that have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body , three pairs of jointed legs, compound eyes, and two antennae...

s are routinely killed and prepared for mounted display, whereby they are impaled by a pin to a portable surface, such as a board or display box made of wood, cork, cardboard, or synthetic foam. The pins used are typically 38mm long and 0.46mm in diameter, though smaller and larger pins are available. Impaled specimens of insects, spiders, butterflies, moths, scorpions, and similar organisms are collected, preserved, and displayed in this manner in private, academic, and museum collections around the world.

See also

- Impalement artsImpalement artsImpalement arts are a type of performing art in which a performer plays the role of human target for a fellow performer who demonstrates accuracy skills in disciplines such as knife throwing and archery. Impalement is actually what the performers endeavour to avoid - the thrower or marksman aims...

- Iron maiden

- Penetrating traumaPenetrating traumaPenetrating trauma is an injury that occurs when an object pierces the skin and enters a tissue of the body, creating an open wound. In blunt, or non-penetrating trauma, there may be an impact, but the skin is not necessarily broken. The penetrating object may remain in the tissues, come back out...

- PunishmentPunishmentPunishment is the authoritative imposition of something negative or unpleasant on a person or animal in response to behavior deemed wrong by an individual or group....