Yemenite Jews

Encyclopedia

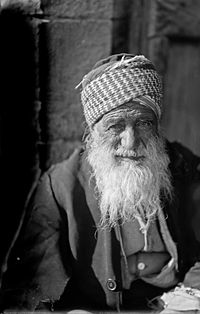

Yemenite Jews are those Jews who live, or whose recent ancestors lived, in Yemen

(תֵּימָן, Standard Teman Tiberian

; "far south"). Between June 1949 and September 1950, the overwhelming majority of Yemen's Jewish population was transported to Israel in Operation Magic Carpet

. Most Yemenite Jews now live in Israel

, with some others in the United States

, and fewer elsewhere. Only a handful remain in Yemen, mostly elderly.

Yemenite Jews have a unique religious tradition that marks them out as separate from Ashkenazi

, Sephardi and other Jewish groups

. It is debatable whether they should be described as "Mizrahi Jews

", as most other Mizrahi groups have over the last few centuries undergone a process of total or partial assimilation to Sephardic culture

and liturgy

. (While the Shami sub-group of Yemenite Jews did adopt a Sephardic-influenced rite, this was for theological reasons and did not reflect a demographic or cultural shift.)

One local Yemenite Jewish tradition dates the earliest settlement of Jews in the Arabian Peninsula to the time of King Solomon

One local Yemenite Jewish tradition dates the earliest settlement of Jews in the Arabian Peninsula to the time of King Solomon

. One explanation is that King Solomon sent Jewish merchant marines to Yemen

to prospect for gold and silver with which to adorn the Temple in Jerusalem

. In 1881, the French vice consulate in Yemen wrote to the leaders of the Alliance in France, that he read a book of the Arab historian Abu-Alfada, that the Jews of Yemen settled in the area in 1451 BC. Another legend places Jewish craftsmen in the region as requested by Bilqis, the Queen of Saba (Sheba). The Beta Israel

or Chabashim (Jews in nearby Ethiopia

) have a sister legend of their origins that places the Queen of Sheba as married to King Solomon. Parts of Yemen

, Eritrea

and Ethiopia

at that time were jointly ruled by Sheba

, possibly with its capital in Yemen.

The Sanaite Jews have a legend that their ancestors settled in Yemen forty-two years before the destruction of the First Temple

. It is said that under the prophet Jeremiah some 75,000 Jews, including priests and Levite

s, traveled to Yemen. The Jews of Habban

in southern Yemen have a legend that they are the descendants of Judeans who settled in the area before the destruction of the Second Temple

. These Judeans supposedly belonged to a brigade dispatched by Herod the Great

to assist the Roman legions fighting in the region.

Another legend states that when Ezra

commanded the Jews to return to Jerusalem they disobeyed, whereupon he pronounced a ban

upon them. According to this legend, as a punishment for this hasty action Ezra was denied burial in Israel

. As a result of this local tradition, which can not be validated historically, it is said that no Jew of Yemen gives the name of Ezra to a child, although all other Biblical appellatives are used. The Yemenite Jews claim that Ezra cursed them to be a poor people for not heeding his call. This seems to have come true in the eyes of some Yemenites, as Yemen is extremely poor. However, some Yemenite sages in Israel today emphatically reject this story as myth, if not outright blasphemy.

The immigration of the majority of Jews into Yemen appears to have taken place about the beginning of the 2nd century AD, although the province is mentioned neither by Josephus

nor by the main books of the Jewish oral law, the Mishnah

and Talmud

. According to some sources, the Jews of Yemen enjoyed prosperity until the 6th century AD The Himyarite King, Abu-Karib Asad Toban converted to Judaism at the end of the 5th century, while laying siege to Medina. His army had marched north to battle the Aksumites who had been fighting for control of Yemen for a hundred years. The Aksumites were only expelled from the region when the newly Jewish king rallied the Jews together from all over Arabia, together with pagan allies. But this victory was short-lived.

In 518 the kingdom was taken over by Zar'a Yusuf, who "was of royal descent, but he was not the son of his predecessor Ma'di Karib Yafur." He too converted to Judaism, and instigated wars to drive the Aksumite Ethiopians from Arabia. Zar'a Yusuf is chiefly known by his cognomen

Dhu Nuwas

, in reference to his "curly hair." Jewish rule lasted until 525 AD (some date it later, to 530), when Christian

s from the Aksumite Kingdom of Ethiopia defeated and killed Dhu Nuwas, and took power in Yemen. According to a number of medieval historians , who depend on the account of John of Ephesus, Dhū Nuwas announced that he would persecute the Christians living in his kingdom because Christian states persecuted his fellow co-religionists in their realms; a letter survives written by Simon, the bishop of Beth Arsham in 524 AD, which recounts the persecution by a person referred to as Dimnon in Najran (modern al-Ukhdud in Saudi Arabia

). The persecution is apparently described and condemned in the Qur'an (al-Buruj:4). According to the contemporary sources , after seizing the throne of the Himyarites, in 518 or 523 AD Dhū Nuwas attacked the Aksumite (mainly Christian) garrison at Zafar, capturing them and burning their churches. He then moved against Najran, a Christian and Aksumite stronghold. After accepting the city's capitulation, he massacred those inhabitants who would not renounce Christianity. Estimates of the death toll from this event range up to 20,000 in some sources. Legends hostile to Dhu Nuwas certainly betray the viewpoints and self-justifications of those who defeated him and later Muslim historiographers, and therefore need to be taken with the due grain of salt. What is clear is that the Jewish Yemenite kings did not force Judaism on their subjects, following the Talmudic view that righteous peoples exist in all cultures and religions and need not convert to Judaism to be saved. As a consequence, it is not clear what percentage of the population was or became Jewish. San'a, however, was said to be a chiefly Jewish city.

, payment of a poll tax imposed on certain non-Muslim monotheists (people of the Book). Active Muslim

persecution of the Jews did not gain full force until the Shiite-Zaydi clan seized power, from the more tolerant Sunni Muslims, early in the 10th century.

As the only visible "outsiders" (though their presence in Yemen predated the introduction and mass conversion of the population to Islam) the Jews of Yemen were treated as pariahs, second-class citizens who needed to be perennially reminded of their submission or conversion to the ruling Islamic faith. The Zaydi enforced a statute known as the Orphan's Decree

, anchored in their own 18th century legal interpretations and enforced at the end of that century. It obligated the Zaydi state to take under its protection and to educate in Islamic ways any dhimmi

(i.e. non-Muslim) child whose parents had died when he or she was a minor. The Orphan's Decree was ignored during the Ottoman

rule (1872–1918), but was renewed during the period of Imam Yahya (1918–1948).

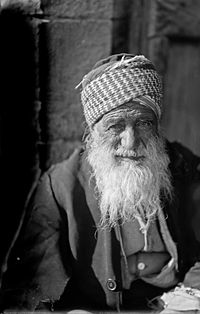

Under the Zaydi rule, the Jews were considered to be impure, and therefore forbidden to touch a Muslim or a Muslim's food. They were obligated to humble themselves before a Muslim, to walk to the left side, and greet him first. They could not build houses higher than a Muslim's or ride a camel or horse, and when riding on a mule or a donkey, they had to sit sideways. Upon entering the Muslim quarter a Jew had to take off his foot-gear and walk barefoot. If attacked with stones or fists by Islamic youth, a Jew was not allowed to defend himself. In such situations he had the option of fleeing or seeking intervention by a merciful Muslim passerby.

The Jews of Yemen had expertise in a wide range of trades normally avoided by Zaydi Muslims. Trades such as silver-smithing, blacksmiths, repairing weapons and tools, weaving, pottery, masonry, carpentry, shoe making, and tailoring were occupations that were exclusively taken by Jews. The division of labor created a sort of covenant, based on mutual economic and social dependency, between the Zaydi Muslim population and the Jews of Yemen. The Muslims produced and supplied food, and the Jews supplied all manufactured products and services that the Yemeni farmers needed.

(200), Sana (10,000), Sada

(1,000), Dhamar

(1,000), and the desert of Beda (2,000). Other significant Jewish communities in Yemen were based in the south central highlands in the cities of: Taiz (the birthplace of one of the most famous of Yemenite Jewish spiritual leaders, Mori Salem Al-Shabazzi Mashtaw), Ba'dan, and other cities and towns in the Shar'ab region. Yemenite Jews were chiefly artisans, including gold-, silver- and blacksmiths in the San'a area, and coffee merchants in the south central highland areas.

According to the Jewish traveler Jacob Saphir

, the majority of Yemenite Jews during his visit of 1862 entertained belief in the messianic proclamations of Shukr Kuhayl I

. Earlier Yemenite messiah claimants included the anonymous 12th-century messiah who was the subject of Maimonides

' famous Iggeret Teman, the messiah of Bayhan (c.1495), and Suleiman Jamal (c.1667), in what Lenowitz regards as a unified messiah history spanning 600 years.

Yemenite Jews and the Aramaic speaking Kurdish Jews

Yemenite Jews and the Aramaic speaking Kurdish Jews

are the only communities who maintain the tradition of reading the Torah in the synagogue in both Hebrew and the Aramaic Targum

("translation"). Most non-Yemenite synagogues have a hired or specified person called a Baal Koreh, who reads from the Torah scroll when congregants are called to the Torah scroll for an aliyah

. In the Yemenite tradition each person called to the Torah scroll for an aliyah reads for himself. Children under the age of Bar Mitzvah are often given the sixth aliyah. Each verse of the Torah read in Hebrew is followed by the Aramaic translation, usually chanted by a child. Both the sixth aliyah and the Targum have a simplified melody, distinct from the general Torah melody used for the other aliyot.

Like most other Jewish communities, Yemenite Jews chant different melodies for Torah, Prophets (Haftara), Megillat Aicha (Book of Lamentations

), Kohelet (Ecclesiastes, read during Sukkot

), and Megillat Esther

(the Scroll of Esther read on Purim). Unlike in Ashkenazic communities, there are melodies for Mishle (Proverbs) and Psalms

.

In larger Jewish communities, such as Sana'a

and Sad'a, boys were sent to the Ma'lamed at the age of three to begin their religious learning. They attended the Ma'lamed from early dawn to sunset Sunday through Thursday and until noon on Friday. Jewish women were required to have a thorough knowledge of the laws pertaining to Kashrut

and Taharat Mishpachah (family purity) i.e. Niddah

. Some women even mastered the laws of Shechita

, thereby acting as ritual slaughterers.

People also sat on the floors of synagogues instead of chairs, similar to the way many other non-Ashkenazi Jews sat in synagogues. This is in accordance with what Rambam (Maimonides

) wrote in his Mishneh Torah

:

The lack of chairs may also have been to provide more space for prostration, another ancient Jewish observance that the Jews of Yemen continued to practise until very recent times. There are still a few Yemenite Jews who prostrate themselves during the part of every-day Jewish prayer called Tachanun

(Supplication), though such individuals usually do so in privacy. In the small Jewish community that exists today in Bet Harash Prostration is still done during the tachnun prayer. Jews of European origin generally prostrate only during certain portions of special prayers during Rosh Hashanah

(Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur

(Day of Atonement). Prostration was a common practise amongst all Jews until some point during the late Middle Ages or Renaissance period.

Like Yemenite Jewish homes, the synagogues in Yemen had to be lower in height than the lowest mosque in the area. In order to accommodate this, synagogues were built into the ground to give them more space without looking large from the outside. In some parts of Yemen, minyanim would often just meet in homes of Jews instead of the community having a separate building for a synagogue. Beauty and artwork were saved for the ritual objects in the synagogue

and in the home.

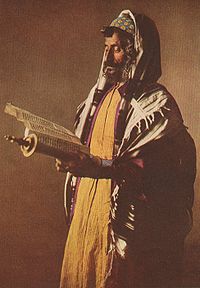

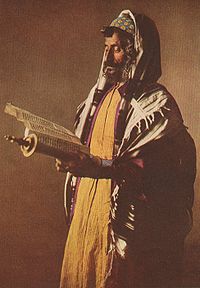

Yemenite Jews also wore a distinctive tallit often found to this day. The Yemenite tallit features a wide atara and large corner patches, embellished with silver or gold thread, and the fringes along the sides of the tallit are netted. According to the Baladi custom, the tzitzits are tied with chulyot, based on the Rambam.

During a Yemenite Jewish wedding, the bride is bedecked with jewelry and wears the traditional wedding costume of Yemenite Jews. Her elaborate headdress is decorated with flowers and rue leaves, which are believed to ward off evil. Gold threads are woven into the fabric of her clothing. Songs are sung as a central part of a seven-day wedding celebration and their lyrics often tell of friendship and love in alternating verses of Hebrew and Arabic.

During a Yemenite Jewish wedding, the bride is bedecked with jewelry and wears the traditional wedding costume of Yemenite Jews. Her elaborate headdress is decorated with flowers and rue leaves, which are believed to ward off evil. Gold threads are woven into the fabric of her clothing. Songs are sung as a central part of a seven-day wedding celebration and their lyrics often tell of friendship and love in alternating verses of Hebrew and Arabic.

Yemenite and other Eastern Jewish communities also perform a henna ceremony, an ancient ritual with Bronze Age

origins, a few weeks or days before the wedding. In the ceremony the bride and her guests hands and feet are decorated in intricate designs with a cosmetic paste derived from the henna

plant. After the paste has remained on the skin for up to two hours it is removed and leaves behind a deep orange stain that fades after two to three weeks.

Yemenites, like other Middle Eastern and North African Jewish communities, had a special affinity for Henna due to biblical and Talmudic references. Henna, in the Bible, is Camphire, and is mentioned in the Song of Solomon, as well as in the Talmud.

Rashi, a Jewish scholar from 11th c France, interpreted this passage that the clusters of henna flowers were a metaphor for forgiveness and absolution, showing that God forgave those who tested Him (the Beloved) in the desert. Henna was grown as a hedgerow around vineyards to hold soil against wind erosion in Israel as it was in other countries. A henna hedge with dense thorny branches protected a vulnerable, valuable crop such as a vineyard from hungry animals. The hedge, which protected and defended the vineyard, also had clusters of fragrant flowers. This would imply a metaphor for henna of a "beloved", who defends, shelters, and delights his lover. In the first millennium BCE, in Canaanite Israel, henna was closely associated with human sexuality and love, and the divine coupling of goddess and consort.

The three main groups of Yemenite Jews are the Baladi, Shami, and the Maimonideans or "Rambamists".

The three main groups of Yemenite Jews are the Baladi, Shami, and the Maimonideans or "Rambamists".

The differences between these groups largely concern the respective influence of the original Yemenite tradition, which was largely based on the works of Maimonides

, and of the Kabbalistic

tradition embodied in the Zohar

and the school of Isaac Luria

, which was increasingly influential from the 17th century on.

Two Jewish travelers, Joseph Halévy

, a French-trained Jewish Orientalist, and Edward Glaser, an Austrian-Jewish astronomer, in particular had a strong influence on a group of young Yemenite Jews, the most outstanding of whom was Rabbi Yiḥyah Qafiḥ. As a result of his contact with Halévy and Glaser, Qafiḥ introduced modern content into the educational system. Qafiḥ opened a new school and, in addition to traditional subjects, introduced arithmetic, Hebrew and Arabic, with the grammar of both languages. The curriculum also included subjects such as natural science, history, geography, astronomy, sports and Turkish.

The Dor Daim and Iqshim dispute about the Zohar literature broke out in 1913, inflamed Sana'a

's Jewish community, and split into two rival groups, that maintained separate communal institutions until the late 1940s. Rabbi Qafiḥ and his friends were the leaders of a group of Maimonideans called Dor Daim

(the "generation of knowledge"). Their goal was to bring Yemenite Jews back to the original Maimonidean method of understanding Judaism that existed in pre-17th century Yemen

.

Similar to certain Spanish and Portuguese Jews

(Western Sephardi Jews

), the Dor Daim

rejected the Zohar

, a book of esoteric mysticism. They felt that the Kabbalah based on the Zohar was irrational, alien, and inconsistent with the true reasonable nature of Judaism. In 1913, when it seemed that Rabbi Qafiḥ, then headmaster of the new Jewish school and working closely with the Ottoman authorities, enjoyed sufficient political support, the Dor Daim made its views public and tried to convince the entire community to accept them. Many of the non-Dor Dai elements of the community rejected the Dor Dai concepts. The opposition, the Iqshim, headed by Rabbi Yaḥya Yiṣḥaq, the Hakham Bashi

, refused to deviate from the accepted customs and the study of Zohar. One of the Iqshim's targets in the fight against Rabbi Qafiḥ was his modern Turkish-Jewish school. Due to the Dor Daim and Iqshim dispute, the school closed 5 years after it was opened, before the educational system could develop a reserve of young people who had been exposed to its ideas.

have a distinct sound, except for the letters ס sāmekh and ש śîn. The Sanaani Hebrew pronunciation (used by the majority) has been indirectly critiqued by Saadia Gaon

since it contains the Hebrew letters jimmel and guf, which he rules is incorrect. There are Yemenite scholars, such as Rabbi Ratzon Arusi, who say that such a perspective is a misunderstanding of Saadia Gaon's words.

Rabbi Mazuz postulates this hypothesis through the Jerban (Tunisia

) Jewish dialect's use of gimmel and quf, switching to jimmel and guf when talking with Gentiles in the Arabic dialect of Jerba. Some feel that the Shar'abi pronunciation of Yemen is more accurate and similar to the Babylonian

dialect since they both use a gimmel and quf instead of the jimmel and guf. While Jewish boys learned Hebrew since the age of 3, it was used primarily as a liturgical and scholarly language. In daily life, Yemenite Jews spoke in regional Judeo-Arabic

.

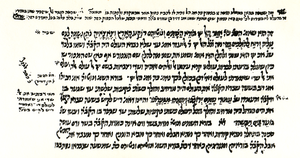

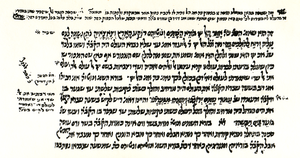

The oldest Yemenite manuscripts are those of the Hebrew Bible

The oldest Yemenite manuscripts are those of the Hebrew Bible

, which the Yemenite Jews call "Taj" ("crown"). The oldest texts dating from the 9th century, and each of them has a short Masoretic introduction, while many contain Arabic commentaries.

Yemenite Jews were acquainted with the works of Saadia Gaon

, Rashi

, Kimhi, Nahmanides

, Yehudah ha Levy and Isaac Arama, besides producing a number of exegetes from among themselves. In the 14th century Nathanael ben Isaiah wrote an Arabic commentary on the Bible; in the second half of the 15th century Saadia ben David al-Adani was the author of a commentary on Leviticus

, Numbers

, and Deuteronomy

. Abraham ben Solomon wrote on the Prophets

.

Among the midrash

collections from Yemen mention should be made of the Midrash ha-Gadol

of David bar Amram al-'Adani. Between 1413 and 1430 the physician Yaḥya Zechariah b. Solomon wrote a compilation entitled "Midrash ha-Ḥefeẓ," which included the Pentateuch, Lamentations

, Book of Esther

, and other sections of the Hebrew Bible

. Between 1484 and 1493 David al-Lawani composed his "Midrash al-Wajiz al-Mughni."

Among the Yemenite poets who wrote Hebrew and Arabic hymns modeled after the Spanish school, mention may be made of Yaḥya al-Dhahri and the members of the Al-Shabbezi family. A single non-religious work, inspired by Ḥariri, was written in 1573 by Zechariah ben Saadia (identical with the Yaḥya al-Dhahri mentioned above), under the title "Sefer ha-Musar." The philosophical writers include: Saadia b. Jabeẓ and Saadia b. Mas'ud, both at the beginning of the 14th century; Ibn al-Ḥawas, the author of a treatise in the form of a dialogue written in rimed prose, and termed by its author the "Flower of Yemen"; Ḥasan al-Dhamari; and Joseph ha-Levi b. Jefes, who wrote the philosophical treatises "Ner Yisrael" (1420) and "Kitab al-Masaḥah."

shows a common link, with most communities sharing similar paternal genetic profiles. Furthermore, the Y-chromosome signatures of the Yemenite Jews are also similar to those of other Middle Eastern populations.

One point in which Yemenite Jews appear to differ from Ashkenazi Jews

and most Near Eastern Jewish

communities is in the proportion of sub-Saharan African maternally-transferred gene types (mitochondrial DNA

, or mtDNA) which have entered their gene pool

s. One study found that some Arabic-speaking populations—Palestinians, Jordan

ians, Syria

ns, Iraq

is, and Bedouin

s—have what appears to be substantial mtDNA gene flow from sub-Saharan Africa

, amounting to 10-15% of lineages within the past three millennia. In the case of Yemenites

, the average is actually higher at 35%. Of particular historic interest might be the finding that with almost no exceptions the sub-Saharan gene flow was exclusively female, as stated in this excerpt from the study:

Yemenite Jews, as a traditionally Arabic-speaking community of local Yemenite and Israelite ancestries, are included within the findings for Yemenites, though they average a quarter of the frequency of the non-Jewish Yemenite sample. In other Arabic-speaking populations not mentioned, the African gene types are rarely shared. Other Middle Eastern populations, particularly non-Arabic speakers—Turks

, Persians

, Kurds, Armenians

, Azeris, and Georgians

—have few or no such lineages.

A study performed by the Department of Biological Sciences at Stanford University

found a possible genetic similarity between 11 Ethiopian Jews and 4 Yemenite Jews who took part in the testing. The differentiation statistic and genetic distances for the 11 Ethiopian Jews and 4 Yemenite Jews tested were quite low, among the smallest of comparisons that involved either of these populations. Ethiopian Jewish Y-Chromosomal haplotype are often present in Yemenite and other Jewish populations, but analysis of Y-Chromosomal haplotype frequencies does not indicate a close relationship between Ethiopian Jewish groups. It is possible that the 4 Yemenite Jews from this study may be descendants of reverse migrants of African origin, who crossed Ethiopia to Yemen

. The result from this study suggests that gene flow between Ethiopia and Yemen as a possible explanation. The study also suggests that the gene flow between Ethiopian and Yemenite Jewish populations may not have been direct, but instead could have been between Jewish and non-Jewish populations of both regions.

and the other in Hadramaut. The Jews of Aden lived in and around the city, and flourished during the British protectorate. The Jews of Hadramaut

lived a much more isolated life, and the community was not known to the outside world until the early 20th century. In the early 20th century they had numbered about 50,000; they currently number only a few hundred individuals and reside largely in Sa'dah

and Rada'a.

From 1881 to 1882 a few hundred Jews left Sanaa and several nearby settlements. This wave was followed by other Jews from central Yemen who continued to move into Palestine until 1914. The majority of these groups moved into Jerusalem and Jaffa. Before World War I there was another wave that began in 1906 and continued until 1914. Hundreds of Yemenite Jews made their way to Palestine and chose to settle in the agricultural settlements. It was after these movements that the World Zionist Organization sent Shmuel Yavne'eli to Yemen to encourage Jews to emigrate to Palestine. Yavne'eli reached Yemen at the beginning of 1911 and returned to Palestine in April 1912. Due to Yavne'eli's efforts about 1,000 Jews left central and southern Yemen with several hundred more arriving before 1914.

.jpg) In 1922, the government of Yemen, under Imam Yahya reintroduced an ancient Islamic law entitled the "orphans decree". The law dictated that, if a Jewish boy or girl under the age of twelve was orphaned, they were to be forcibly converted to Islam, their connection to their family and community was to be severed and they had to be handed over to a Muslim foster family. The rule was based on the law that the prophet Mohammed is "the father of the orphans," and on the fact that the Jews in Yemen were considered "under protection" and the ruler was obligated to care for them.

In 1922, the government of Yemen, under Imam Yahya reintroduced an ancient Islamic law entitled the "orphans decree". The law dictated that, if a Jewish boy or girl under the age of twelve was orphaned, they were to be forcibly converted to Islam, their connection to their family and community was to be severed and they had to be handed over to a Muslim foster family. The rule was based on the law that the prophet Mohammed is "the father of the orphans," and on the fact that the Jews in Yemen were considered "under protection" and the ruler was obligated to care for them.

A prominent example is Abdul Rahman al-Iryani

, the President of the Yemen Arab Republic

who was alleged to be of Jewish descent by Dorit Mizrahi, a writer in the Israeli ultra-Orthodox weekly Mishpaha. She claimed to be his niece due to him being her mother's brother. According to her recollection of events, he was born Zekharia Hadad in 1910 to a Yemenite Jewish family in Ibb. He lost his parents in a major disease epidemic at the age of eight and together with his 5-year-old sister, was forcibly converted to Islam and put under the care of separate foster families. He was raised in the powerful al-Iryani family and adopted an Islamic name. al-Iryani would later serve as minister of religious endowments under northern Yemen's first national government and became the only civilian to have led northern Yemen.

However, yemenionline, an online newspaper claimed to have conducted several interviews with several members of the al-Iryani family and residents of Iryan, and allege that this claim of Jewish descent is merely a "fantasy" started in 1967 by Haolam Hazeh, an Israeli tabloid. It states that Zekharia Haddad is in fact, Abdul Raheem al-Haddad, Al-Iryani's foster brother and bodyguard who died in 1980.Abdul Raheem is survived by tens of sons and grandsons.

The most part of both communities emigrated to Israel

after the declaration of the state. The State of Israel in beginning of 1948 initiated Operation Magic Carpet

and airlifted most of Yemen's Jews to Israel.

In 1947, after the partition vote of the British Mandate of Palestine, Arab Muslim rioters, assisted by the local police force, engaged in a bloody pogrom in Aden that killed 82 Jews and destroyed hundreds of Jewish homes. Aden's Jewish community was economically paralyzed, as most of the Jewish stores and businesses were destroyed. Early in 1948, the unfounded rumour of the ritual murder of two girls led to looting.

This increasingly perilous situation led to the emigration of virtually the entire Yemenite Jewish community between June 1949 and September 1950 in Operation Magic Carpet. During this period, over 50,000 Jews emigrated to Israel

.

A smaller, continuous migration was allowed to continue into 1962, when a civil war put an abrupt halt to any further Jewish exodus.

According to an official statement by Alaska Airlines

:

In 2001 a seven-year public inquiry commission concluded that the accusations that Yemenite children were kidnapped are not true. The commission has unequivocally rejected claims of a plot to take children away from Yemenite immigrants. The report determined that documentation exists for 972 of the 1,033 missing children. Five additional missing babies were found to be alive. The commission was unable to discover what happened in another 56 cases. With regard to these unresolved 56 cases, the commission deemed it "possible" that the children were handed over for adoption following decisions made by individual local social workers, but not as part of an official policy.

In Yemen itself, there exists today a small Jewish community in the town of Bayt Harash (2 km away from Raydah

). They have a rabbi, a functioning synagogue and a mikvah

. They also have a boys yeshiva

and a girls seminary, funded by a Satmarer

affiliated Hasidic

organization of Monsey

, New York

, USA.

A small Jewish enclave also exists in the town of Raydah

, which lies approximately 45 mile north of Sana'a. The town hosts a yeshiva

, also funded by a Satmar affiliated organization.

The Yemeni defense forces have gone to great lengths to try to convince the Jews to stay in their towns. These attempts, however, failed and the authorities were forced to provide financial aid for the Jews so they would be able to rent accommodation in safer areas.

In December, 2008, 30 year old Rabbi Moshe Ya'ish al-Nahari of Raydah

was shot and killed by a disturbed mentally ill person who also had previously killed his own wife. After initially being ordered to pay only a fine, the culprit, a former Yemeni Air Force officer who proudly confessed to the crime, was eventually sentenced to death by an appeals court. The murder of al-Nahari, and continual threats against Jews, prompted approximately 20 other Jewish residents of Raydah to emigrate to Israel.

On November 1, 2009 the Wall Street Journal reported that in June 2009, an estimated 350 Jews were left in Yemen, and by October 2009, 60 had immigrated to the United States and 100 were considering to do so. BBC estimated the community at 370 and dwindling.

, 1998, 1979 and 1978 winners Dana International

, Gali Atari

and Izhar Cohen

, 1983 runner-up Ofra Haza

, and 2008 top 10 finalist Boaz Mauda, are Yemenite Jews. Harel Skaat

, who competed at Oslo in 2010, is of a Yemenite Jewish father.

Yemen

The Republic of Yemen , commonly known as Yemen , is a country located in the Middle East, occupying the southwestern to southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, the Red Sea to the west, and Oman to the east....

(תֵּימָן, Standard Teman Tiberian

Tiberian vocalization

The Tiberian vocalization is a system of diacritics devised by the Masoretes to add to the consonantal Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible; this system soon became used to vocalize other texts as well...

; "far south"). Between June 1949 and September 1950, the overwhelming majority of Yemen's Jewish population was transported to Israel in Operation Magic Carpet

Operation Magic Carpet (Yemen)

Operation Magic Carpet is a widely-known nickname for Operation On Wings of Eagles , an operation between June 1949 and September 1950 that brought 49,000 Yemenite Jews to the new state of Israel. British and American transport planes made some 380 flights from Aden, in a secret operation that was...

. Most Yemenite Jews now live in Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

, with some others in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, and fewer elsewhere. Only a handful remain in Yemen, mostly elderly.

Yemenite Jews have a unique religious tradition that marks them out as separate from Ashkenazi

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews, also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim , are the Jews descended from the medieval Jewish communities along the Rhine in Germany from Alsace in the south to the Rhineland in the north. Ashkenaz is the medieval Hebrew name for this region and thus for Germany...

, Sephardi and other Jewish groups

Jewish ethnic divisions

Jewish ethnic divisions refers to a number of distinct communities within the world's ethnically Jewish population. Although considered one single self-identifying ethnicity, there are distinct ethnic divisions among Jews, most of which are primarily the result of geographic branching from an...

. It is debatable whether they should be described as "Mizrahi Jews

Mizrahi Jews

Mizrahi Jews or Mizrahiyim, , also referred to as Adot HaMizrach are Jews descended from the Jewish communities of the Middle East, North Africa and the Caucasus...

", as most other Mizrahi groups have over the last few centuries undergone a process of total or partial assimilation to Sephardic culture

Sephardi Jews

Sephardi Jews is a general term referring to the descendants of the Jews who lived in the Iberian Peninsula before their expulsion in the Spanish Inquisition. It can also refer to those who use a Sephardic style of liturgy or would otherwise define themselves in terms of the Jewish customs and...

and liturgy

Sephardic Judaism

Sephardic law and customs means the practice of Judaism as observed by the Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews, so far as it is peculiar to themselves and not shared with other Jewish groups such as the Ashkenazim...

. (While the Shami sub-group of Yemenite Jews did adopt a Sephardic-influenced rite, this was for theological reasons and did not reflect a demographic or cultural shift.)

Early history

Solomon

Solomon , according to the Book of Kings and the Book of Chronicles, a King of Israel and according to the Talmud one of the 48 prophets, is identified as the son of David, also called Jedidiah in 2 Samuel 12:25, and is described as the third king of the United Monarchy, and the final king before...

. One explanation is that King Solomon sent Jewish merchant marines to Yemen

Yemen

The Republic of Yemen , commonly known as Yemen , is a country located in the Middle East, occupying the southwestern to southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, the Red Sea to the west, and Oman to the east....

to prospect for gold and silver with which to adorn the Temple in Jerusalem

Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem or Holy Temple , refers to one of a series of structures which were historically located on the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem, the current site of the Dome of the Rock. Historically, these successive temples stood at this location and functioned as the centre of...

. In 1881, the French vice consulate in Yemen wrote to the leaders of the Alliance in France, that he read a book of the Arab historian Abu-Alfada, that the Jews of Yemen settled in the area in 1451 BC. Another legend places Jewish craftsmen in the region as requested by Bilqis, the Queen of Saba (Sheba). The Beta Israel

Beta Israel

Beta Israel Israel, Ge'ez: ቤተ እስራኤል - Bēta 'Isrā'ēl, modern Bēte 'Isrā'ēl, EAE: "Betä Ǝsraʾel", "Community of Israel" also known as Ethiopian Jews , are the names of Jewish communities which lived in the area of Aksumite and Ethiopian Empires , nowadays divided between Amhara and Tigray...

or Chabashim (Jews in nearby Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

) have a sister legend of their origins that places the Queen of Sheba as married to King Solomon. Parts of Yemen

Yemen

The Republic of Yemen , commonly known as Yemen , is a country located in the Middle East, occupying the southwestern to southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, the Red Sea to the west, and Oman to the east....

, Eritrea

Eritrea

Eritrea , officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa. Eritrea derives it's name from the Greek word Erethria, meaning 'red land'. The capital is Asmara. It is bordered by Sudan in the west, Ethiopia in the south, and Djibouti in the southeast...

and Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

at that time were jointly ruled by Sheba

Sheba

Sheba was a kingdom mentioned in the Jewish scriptures and the Qur'an...

, possibly with its capital in Yemen.

The Sanaite Jews have a legend that their ancestors settled in Yemen forty-two years before the destruction of the First Temple

Solomon's Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple, was the main temple in ancient Jerusalem, on the Temple Mount , before its destruction by Nebuchadnezzar II after the Siege of Jerusalem of 587 BCE....

. It is said that under the prophet Jeremiah some 75,000 Jews, including priests and Levite

Levite

In Jewish tradition, a Levite is a member of the Hebrew tribe of Levi. When Joshua led the Israelites into the land of Canaan, the Levites were the only Israelite tribe that received cities but were not allowed to be landowners "because the Lord the God of Israel himself is their inheritance"...

s, traveled to Yemen. The Jews of Habban

Habbani Jews

The Habbani Jews are a Jewish tribal group from the Habban region in eastern Yemen .-Ancient and medieval history:...

in southern Yemen have a legend that they are the descendants of Judeans who settled in the area before the destruction of the Second Temple

Second Temple

The Jewish Second Temple was an important shrine which stood on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem between 516 BCE and 70 CE. It replaced the First Temple which was destroyed in 586 BCE, when the Jewish nation was exiled to Babylon...

. These Judeans supposedly belonged to a brigade dispatched by Herod the Great

Herod the Great

Herod , also known as Herod the Great , was a Roman client king of Judea. His epithet of "the Great" is widely disputed as he is described as "a madman who murdered his own family and a great many rabbis." He is also known for his colossal building projects in Jerusalem and elsewhere, including his...

to assist the Roman legions fighting in the region.

Another legend states that when Ezra

Ezra

Ezra , also called Ezra the Scribe and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra. According to the Hebrew Bible he returned from the Babylonian exile and reintroduced the Torah in Jerusalem...

commanded the Jews to return to Jerusalem they disobeyed, whereupon he pronounced a ban

Cherem

Cherem , is the highest ecclesiastical censure in the Jewish community. It is the total exclusion of a person from the Jewish community. It is a form of shunning, and is similar to excommunication in the Catholic Church...

upon them. According to this legend, as a punishment for this hasty action Ezra was denied burial in Israel

History of ancient Israel and Judah

Israel and Judah were related Iron Age kingdoms of ancient Palestine. The earliest known reference to the name Israel in archaeological records is in the Merneptah stele, an Egyptian record of c. 1209 BCE. By the 9th century BCE the Kingdom of Israel had emerged as an important local power before...

. As a result of this local tradition, which can not be validated historically, it is said that no Jew of Yemen gives the name of Ezra to a child, although all other Biblical appellatives are used. The Yemenite Jews claim that Ezra cursed them to be a poor people for not heeding his call. This seems to have come true in the eyes of some Yemenites, as Yemen is extremely poor. However, some Yemenite sages in Israel today emphatically reject this story as myth, if not outright blasphemy.

The immigration of the majority of Jews into Yemen appears to have taken place about the beginning of the 2nd century AD, although the province is mentioned neither by Josephus

Josephus

Titus Flavius Josephus , also called Joseph ben Matityahu , was a 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian and hagiographer of priestly and royal ancestry who recorded Jewish history, with special emphasis on the 1st century AD and the First Jewish–Roman War, which resulted in the Destruction of...

nor by the main books of the Jewish oral law, the Mishnah

Mishnah

The Mishnah or Mishna is the first major written redaction of the Jewish oral traditions called the "Oral Torah". It is also the first major work of Rabbinic Judaism. It was redacted c...

and Talmud

Talmud

The Talmud is a central text of mainstream Judaism. It takes the form of a record of rabbinic discussions pertaining to Jewish law, ethics, philosophy, customs and history....

. According to some sources, the Jews of Yemen enjoyed prosperity until the 6th century AD The Himyarite King, Abu-Karib Asad Toban converted to Judaism at the end of the 5th century, while laying siege to Medina. His army had marched north to battle the Aksumites who had been fighting for control of Yemen for a hundred years. The Aksumites were only expelled from the region when the newly Jewish king rallied the Jews together from all over Arabia, together with pagan allies. But this victory was short-lived.

In 518 the kingdom was taken over by Zar'a Yusuf, who "was of royal descent, but he was not the son of his predecessor Ma'di Karib Yafur." He too converted to Judaism, and instigated wars to drive the Aksumite Ethiopians from Arabia. Zar'a Yusuf is chiefly known by his cognomen

Cognomen

The cognomen nōmen "name") was the third name of a citizen of Ancient Rome, under Roman naming conventions. The cognomen started as a nickname, but lost that purpose when it became hereditary. Hereditary cognomina were used to augment the second name in order to identify a particular branch within...

Dhu Nuwas

Dhu Nuwas

Yūsuf Dhū Nuwas, was the last king of the Himyarite kingdom of Yemen and a convert to Judaism....

, in reference to his "curly hair." Jewish rule lasted until 525 AD (some date it later, to 530), when Christian

Christian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

s from the Aksumite Kingdom of Ethiopia defeated and killed Dhu Nuwas, and took power in Yemen. According to a number of medieval historians , who depend on the account of John of Ephesus, Dhū Nuwas announced that he would persecute the Christians living in his kingdom because Christian states persecuted his fellow co-religionists in their realms; a letter survives written by Simon, the bishop of Beth Arsham in 524 AD, which recounts the persecution by a person referred to as Dimnon in Najran (modern al-Ukhdud in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia , commonly known in British English as Saudi Arabia and in Arabic as as-Sa‘ūdiyyah , is the largest state in Western Asia by land area, constituting the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and the second-largest in the Arab World...

). The persecution is apparently described and condemned in the Qur'an (al-Buruj:4). According to the contemporary sources , after seizing the throne of the Himyarites, in 518 or 523 AD Dhū Nuwas attacked the Aksumite (mainly Christian) garrison at Zafar, capturing them and burning their churches. He then moved against Najran, a Christian and Aksumite stronghold. After accepting the city's capitulation, he massacred those inhabitants who would not renounce Christianity. Estimates of the death toll from this event range up to 20,000 in some sources. Legends hostile to Dhu Nuwas certainly betray the viewpoints and self-justifications of those who defeated him and later Muslim historiographers, and therefore need to be taken with the due grain of salt. What is clear is that the Jewish Yemenite kings did not force Judaism on their subjects, following the Talmudic view that righteous peoples exist in all cultures and religions and need not convert to Judaism to be saved. As a consequence, it is not clear what percentage of the population was or became Jewish. San'a, however, was said to be a chiefly Jewish city.

Rise of Islam in Yemen

As Ahl al-Kitab, protected Peoples of the Scriptures, the Jews were assured freedom of religion only in exchange for the jizyaJizya

Under Islamic law, jizya or jizyah is a per capita tax levied on a section of an Islamic state's non-Muslim citizens, who meet certain criteria...

, payment of a poll tax imposed on certain non-Muslim monotheists (people of the Book). Active Muslim

Muslim

A Muslim, also spelled Moslem, is an adherent of Islam, a monotheistic, Abrahamic religion based on the Quran, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God as revealed to prophet Muhammad. "Muslim" is the Arabic term for "submitter" .Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable...

persecution of the Jews did not gain full force until the Shiite-Zaydi clan seized power, from the more tolerant Sunni Muslims, early in the 10th century.

As the only visible "outsiders" (though their presence in Yemen predated the introduction and mass conversion of the population to Islam) the Jews of Yemen were treated as pariahs, second-class citizens who needed to be perennially reminded of their submission or conversion to the ruling Islamic faith. The Zaydi enforced a statute known as the Orphan's Decree

Orphans' Decree

The Orphans' Decree was introduced in Yemen and obligated the Zaydi state to take under its protection and to educate in Islamic ways any dhimmi child whose parents had died when he or she was a minor...

, anchored in their own 18th century legal interpretations and enforced at the end of that century. It obligated the Zaydi state to take under its protection and to educate in Islamic ways any dhimmi

Dhimmi

A , is a non-Muslim subject of a state governed in accordance with sharia law. Linguistically, the word means "one whose responsibility has been taken". This has to be understood in the context of the definition of state in Islam...

(i.e. non-Muslim) child whose parents had died when he or she was a minor. The Orphan's Decree was ignored during the Ottoman

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

rule (1872–1918), but was renewed during the period of Imam Yahya (1918–1948).

Under the Zaydi rule, the Jews were considered to be impure, and therefore forbidden to touch a Muslim or a Muslim's food. They were obligated to humble themselves before a Muslim, to walk to the left side, and greet him first. They could not build houses higher than a Muslim's or ride a camel or horse, and when riding on a mule or a donkey, they had to sit sideways. Upon entering the Muslim quarter a Jew had to take off his foot-gear and walk barefoot. If attacked with stones or fists by Islamic youth, a Jew was not allowed to defend himself. In such situations he had the option of fleeing or seeking intervention by a merciful Muslim passerby.

The Jews of Yemen had expertise in a wide range of trades normally avoided by Zaydi Muslims. Trades such as silver-smithing, blacksmiths, repairing weapons and tools, weaving, pottery, masonry, carpentry, shoe making, and tailoring were occupations that were exclusively taken by Jews. The division of labor created a sort of covenant, based on mutual economic and social dependency, between the Zaydi Muslim population and the Jews of Yemen. The Muslims produced and supplied food, and the Jews supplied all manufactured products and services that the Yemeni farmers needed.

Yemenite Jews and Maimonides

Yemenite Jews have lived principally in AdenAden

Aden is a seaport city in Yemen, located by the eastern approach to the Red Sea , some 170 kilometres east of Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000. Aden's ancient, natural harbour lies in the crater of an extinct volcano which now forms a peninsula, joined to the mainland by a...

(200), Sana (10,000), Sada

Sada

Sada as a surname may refer to:*Daniel Sada , Mexican writer*Eugenio Garza Sada , Mexican businessman and philanthropist*Georges Sada , Iraqi author and statesman*Masashi Sada , Japanese folk singer...

(1,000), Dhamar

Dhamar, Yemen

Dhamar is a city in southwestern Yemen. It is located at , at an elevation of around 2400 metres.-Overview:Dhamar is situated 100 km to the south of Sana'a, north of Ibb, and west of Al-Beidha, 2700 m above sea level. Its name “Dhamar” goes back to the king of Sheba and Dou-Reddan at 15-35 AD...

(1,000), and the desert of Beda (2,000). Other significant Jewish communities in Yemen were based in the south central highlands in the cities of: Taiz (the birthplace of one of the most famous of Yemenite Jewish spiritual leaders, Mori Salem Al-Shabazzi Mashtaw), Ba'dan, and other cities and towns in the Shar'ab region. Yemenite Jews were chiefly artisans, including gold-, silver- and blacksmiths in the San'a area, and coffee merchants in the south central highland areas.

19th-century Yemenite messianic movements

During this period messianic expectations were very intense among the Jews of Yemen (and among many Arabs as well). The three pseudo-messiahs of this period, and their years of activity, are:- Shukr Kuhayl IShukr Kuhayl IShukr ben Salim Kuhayl I , also known as Mari Shukr Kuhayl I , was a Yemenite messianic claimant of the 19th century....

(1861–65) - Shukr Kuhayl II (1868–75)

- Joseph Abdallah (1888–93)

According to the Jewish traveler Jacob Saphir

Jacob Saphir

Jacob Saphir was a Meshulach and traveler of Rumanian descent, born in Oshmyany, government of Wilna.While still a boy he went to Palestine with his parents, who settled at Safed, and at their death in 1836 he moved to Jerusalem...

, the majority of Yemenite Jews during his visit of 1862 entertained belief in the messianic proclamations of Shukr Kuhayl I

Shukr Kuhayl I

Shukr ben Salim Kuhayl I , also known as Mari Shukr Kuhayl I , was a Yemenite messianic claimant of the 19th century....

. Earlier Yemenite messiah claimants included the anonymous 12th-century messiah who was the subject of Maimonides

Maimonides

Moses ben-Maimon, called Maimonides and also known as Mūsā ibn Maymūn in Arabic, or Rambam , was a preeminent medieval Jewish philosopher and one of the greatest Torah scholars and physicians of the Middle Ages...

' famous Iggeret Teman, the messiah of Bayhan (c.1495), and Suleiman Jamal (c.1667), in what Lenowitz regards as a unified messiah history spanning 600 years.

Religious traditions

Kurdish Jews

Kurdish Jews or Kurdistani Jews are the ancient Eastern Jewish communities, inhabiting the region known as Kurdistan in northern Mesopotamia, roughly covering parts of Iran, northern Iraq, Syria and eastern Turkey. Their clothing and culture is similar to neighbouring Kurdish Muslims and Christian...

are the only communities who maintain the tradition of reading the Torah in the synagogue in both Hebrew and the Aramaic Targum

Targum

Taekwondo is a Korean martial art and the national sport of South Korea. In Korean, tae means "to strike or break with foot"; kwon means "to strike or break with fist"; and do means "way", "method", or "path"...

("translation"). Most non-Yemenite synagogues have a hired or specified person called a Baal Koreh, who reads from the Torah scroll when congregants are called to the Torah scroll for an aliyah

Aliyah (Torah)

An aliyah is the calling of a member of a Jewish congregation to the bimah for a segment of reading from the Torah. The person who receives the aliyah goes up to the bimah before the reading and recites a blessing. After the reading, the recipient then recites another concluding blessing...

. In the Yemenite tradition each person called to the Torah scroll for an aliyah reads for himself. Children under the age of Bar Mitzvah are often given the sixth aliyah. Each verse of the Torah read in Hebrew is followed by the Aramaic translation, usually chanted by a child. Both the sixth aliyah and the Targum have a simplified melody, distinct from the general Torah melody used for the other aliyot.

Like most other Jewish communities, Yemenite Jews chant different melodies for Torah, Prophets (Haftara), Megillat Aicha (Book of Lamentations

Book of Lamentations

The Book of Lamentations ) is a poetic book of the Hebrew Bible composed by the Jewish prophet Jeremiah. It mourns the destruction of Jerusalem and the Holy Temple in the 6th Century BCE....

), Kohelet (Ecclesiastes, read during Sukkot

Sukkot

Sukkot is a Biblical holiday celebrated on the 15th day of the month of Tishrei . It is one of the three biblically mandated festivals Shalosh regalim on which Hebrews were commanded to make a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem.The holiday lasts seven days...

), and Megillat Esther

Esther

Esther , born Hadassah, is the eponymous heroine of the Biblical Book of Esther.According to the Bible, she was a Jewish queen of the Persian king Ahasuerus...

(the Scroll of Esther read on Purim). Unlike in Ashkenazic communities, there are melodies for Mishle (Proverbs) and Psalms

Psalms

The Book of Psalms , commonly referred to simply as Psalms, is a book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Bible...

.

- Every Yemenite Jew knew how to read from the Torah Scroll with the correct pronunciation and tune, exactly right in every detail. Each man who was called up to the Torah read his section by himself. All this was possible because children right from the start learned to read without any vowels. Their diction is much more correct than the Sephardic and Ashkenazic dialect. The results of their education are outstanding, for example if someone is speaking with his neighbor and needs to quote a verse from the Bible, he speaks it out by heart, without pause or effort, with its melody.

In larger Jewish communities, such as Sana'a

Sana'a

-Districts:*Al Wahdah District*As Sabain District*Assafi'yah District*At Tahrir District*Ath'thaorah District*Az'zal District*Bani Al Harith District*Ma'ain District*Old City District*Shu'aub District-Old City:...

and Sad'a, boys were sent to the Ma'lamed at the age of three to begin their religious learning. They attended the Ma'lamed from early dawn to sunset Sunday through Thursday and until noon on Friday. Jewish women were required to have a thorough knowledge of the laws pertaining to Kashrut

Kashrut

Kashrut is the set of Jewish dietary laws. Food in accord with halakha is termed kosher in English, from the Ashkenazi pronunciation of the Hebrew term kashér , meaning "fit" Kashrut (also kashruth or kashrus) is the set of Jewish dietary laws. Food in accord with halakha (Jewish law) is termed...

and Taharat Mishpachah (family purity) i.e. Niddah

Niddah

Niddah is a Hebrew term describing a woman during menstruation, or a woman who has menstruated and not yet completed the associated requirement of immersion in a mikveh ....

. Some women even mastered the laws of Shechita

Shechita

Shechita is the ritual slaughter of mammals and birds according to Jewish dietary laws...

, thereby acting as ritual slaughterers.

People also sat on the floors of synagogues instead of chairs, similar to the way many other non-Ashkenazi Jews sat in synagogues. This is in accordance with what Rambam (Maimonides

Maimonides

Moses ben-Maimon, called Maimonides and also known as Mūsā ibn Maymūn in Arabic, or Rambam , was a preeminent medieval Jewish philosopher and one of the greatest Torah scholars and physicians of the Middle Ages...

) wrote in his Mishneh Torah

Mishneh Torah

The Mishneh Torah subtitled Sefer Yad ha-Hazaka is a code of Jewish religious law authored by Maimonides , one of history's foremost rabbis...

:

- "We are to practise respect in synagogues... and all of the People of Israel in Spain, and in the West, and in the area of Iraq, and in the Land of Israel, are accustomed to light lanterns in the synagogues, and to lay out mats on the ground, in order to sit upon them. But in the cities of Edom (portions of Europe), there they sit on chairs."

- - Hilchot Tefila 11:5

- "..and because of this (prostration) all of Israel is accustomed to lay mats in their synagogues on the stone floors, or types of straw and hay, to separate between their faces and the stones."

- - Hilchot Avodah Zarah 6:7

The lack of chairs may also have been to provide more space for prostration, another ancient Jewish observance that the Jews of Yemen continued to practise until very recent times. There are still a few Yemenite Jews who prostrate themselves during the part of every-day Jewish prayer called Tachanun

Tachanun

Tachanun or , also called nefillat apayim is part of Judaism's morning and afternoon services, after the recitation of the Amidah, the central part of the daily Jewish prayer services...

(Supplication), though such individuals usually do so in privacy. In the small Jewish community that exists today in Bet Harash Prostration is still done during the tachnun prayer. Jews of European origin generally prostrate only during certain portions of special prayers during Rosh Hashanah

Rosh Hashanah

Rosh Hashanah , , is the Jewish New Year. It is the first of the High Holy Days or Yamim Nora'im which occur in the autumn...

(Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur , also known as Day of Atonement, is the holiest and most solemn day of the year for the Jews. Its central themes are atonement and repentance. Jews traditionally observe this holy day with a 25-hour period of fasting and intensive prayer, often spending most of the day in synagogue...

(Day of Atonement). Prostration was a common practise amongst all Jews until some point during the late Middle Ages or Renaissance period.

Like Yemenite Jewish homes, the synagogues in Yemen had to be lower in height than the lowest mosque in the area. In order to accommodate this, synagogues were built into the ground to give them more space without looking large from the outside. In some parts of Yemen, minyanim would often just meet in homes of Jews instead of the community having a separate building for a synagogue. Beauty and artwork were saved for the ritual objects in the synagogue

Synagogue

A synagogue is a Jewish house of prayer. This use of the Greek term synagogue originates in the Septuagint where it sometimes translates the Hebrew word for assembly, kahal...

and in the home.

Yemenite Jews also wore a distinctive tallit often found to this day. The Yemenite tallit features a wide atara and large corner patches, embellished with silver or gold thread, and the fringes along the sides of the tallit are netted. According to the Baladi custom, the tzitzits are tied with chulyot, based on the Rambam.

Weddings and marriage traditions

Yemenite and other Eastern Jewish communities also perform a henna ceremony, an ancient ritual with Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

origins, a few weeks or days before the wedding. In the ceremony the bride and her guests hands and feet are decorated in intricate designs with a cosmetic paste derived from the henna

Henna

Henna is a flowering plant used since antiquity to dye skin, hair, fingernails, leather and wool. The name is also used for dye preparations derived from the plant, and for the art of temporary tattooing based on those dyes...

plant. After the paste has remained on the skin for up to two hours it is removed and leaves behind a deep orange stain that fades after two to three weeks.

Yemenites, like other Middle Eastern and North African Jewish communities, had a special affinity for Henna due to biblical and Talmudic references. Henna, in the Bible, is Camphire, and is mentioned in the Song of Solomon, as well as in the Talmud.

- "My Beloved is unto me as a cluster of Camphire in the vineyards of En-Gedi" Song of Solomon, 1:14

Rashi, a Jewish scholar from 11th c France, interpreted this passage that the clusters of henna flowers were a metaphor for forgiveness and absolution, showing that God forgave those who tested Him (the Beloved) in the desert. Henna was grown as a hedgerow around vineyards to hold soil against wind erosion in Israel as it was in other countries. A henna hedge with dense thorny branches protected a vulnerable, valuable crop such as a vineyard from hungry animals. The hedge, which protected and defended the vineyard, also had clusters of fragrant flowers. This would imply a metaphor for henna of a "beloved", who defends, shelters, and delights his lover. In the first millennium BCE, in Canaanite Israel, henna was closely associated with human sexuality and love, and the divine coupling of goddess and consort.

Religious groups

The differences between these groups largely concern the respective influence of the original Yemenite tradition, which was largely based on the works of Maimonides

Maimonides

Moses ben-Maimon, called Maimonides and also known as Mūsā ibn Maymūn in Arabic, or Rambam , was a preeminent medieval Jewish philosopher and one of the greatest Torah scholars and physicians of the Middle Ages...

, and of the Kabbalistic

Kabbalah

Kabbalah/Kabala is a discipline and school of thought concerned with the esoteric aspect of Rabbinic Judaism. It was systematized in 11th-13th century Hachmei Provence and Spain, and again after the Expulsion from Spain, in 16th century Ottoman Palestine...

tradition embodied in the Zohar

Zohar

The Zohar is the foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah and scriptural interpretations as well as material on Mysticism, mythical cosmogony, and mystical psychology...

and the school of Isaac Luria

Isaac Luria

Isaac Luria , also called Yitzhak Ben Shlomo Ashkenazi acronym "The Ari" "Ari-Hakadosh", or "Arizal", meaning "The Lion", was a foremost rabbi and Jewish mystic in the community of Safed in the Galilee region of Ottoman Palestine...

, which was increasingly influential from the 17th century on.

- The Baladi Jews (from Arabic balad, country) generally follow the legal rulingsHalakhaHalakha — also transliterated Halocho , or Halacha — is the collective body of Jewish law, including biblical law and later talmudic and rabbinic law, as well as customs and traditions.Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life; Jewish...

of the Rambam (MaimonidesMaimonidesMoses ben-Maimon, called Maimonides and also known as Mūsā ibn Maymūn in Arabic, or Rambam , was a preeminent medieval Jewish philosopher and one of the greatest Torah scholars and physicians of the Middle Ages...

) as codified in his work the Mishneh TorahMishneh TorahThe Mishneh Torah subtitled Sefer Yad ha-Hazaka is a code of Jewish religious law authored by Maimonides , one of history's foremost rabbis...

. Their liturgy was developed by a rabbi known as the MaharitzYihhyah SalahhRabbi Yiḥyah Salaḥ, known as the Maharitz , was an 18th century Yemenite rabbi. He was the author of a prayer book in which he attempted to preserve as much as possible of the traditional Yemenite rite, while making some concessions to the needs of those who followed the Kabbalah as taught by...

(Mori Ha-Rav Yihye Tzalahh), in an attempt to break the deadlock between the pre-existing followers of Maimonides and the new followers of the mystic, Isaac Luria. It substantially follows the older Yemenite tradition, with only a few concessions to the usages of the AriIsaac LuriaIsaac Luria , also called Yitzhak Ben Shlomo Ashkenazi acronym "The Ari" "Ari-Hakadosh", or "Arizal", meaning "The Lion", was a foremost rabbi and Jewish mystic in the community of Safed in the Galilee region of Ottoman Palestine...

. A Baladi Jew may or may not accept the Kabbalah theologically: if he does, he regards himself as following Luria's own advice that every Jew should follow his ancestral tradition.

- The Shami Jews (from Arabic ash-Sham, the north, referring to Palestine or DamascusDamascusDamascus , commonly known in Syria as Al Sham , and as the City of Jasmine , is the capital and the second largest city of Syria after Aleppo, both are part of the country's 14 governorates. In addition to being one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, Damascus is a major...

) represent those who accepted the Zohar in the 17th century and modified their siddurSiddurA siddur is a Jewish prayer book, containing a set order of daily prayers. This article discusses how some of these prayers evolved, and how the siddur, as it is known today has developed...

(prayer book) to accommodate the usages of the AriIsaac LuriaIsaac Luria , also called Yitzhak Ben Shlomo Ashkenazi acronym "The Ari" "Ari-Hakadosh", or "Arizal", meaning "The Lion", was a foremost rabbi and Jewish mystic in the community of Safed in the Galilee region of Ottoman Palestine...

to the maximum extent. The text of their siddur largely follows the SephardicSephardic JudaismSephardic law and customs means the practice of Judaism as observed by the Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews, so far as it is peculiar to themselves and not shared with other Jewish groups such as the Ashkenazim...

tradition, though the pronunciation, chant and customs are still Yemenite in flavour. They generally base their legal rulingsHalakhaHalakha — also transliterated Halocho , or Halacha — is the collective body of Jewish law, including biblical law and later talmudic and rabbinic law, as well as customs and traditions.Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life; Jewish...

both on the Rambam (MaimonidesMaimonidesMoses ben-Maimon, called Maimonides and also known as Mūsā ibn Maymūn in Arabic, or Rambam , was a preeminent medieval Jewish philosopher and one of the greatest Torah scholars and physicians of the Middle Ages...

) and on the Shulchan AruchShulchan AruchThe Shulchan Aruch also known as the Code of Jewish Law, is the most authoritative legal code of Judaism. It was authored in Safed, Israel, by Yosef Karo in 1563 and published in Venice two years later...

(Code of Jewish Law). In their interpretation of Jewish lawHalakhaHalakha — also transliterated Halocho , or Halacha — is the collective body of Jewish law, including biblical law and later talmudic and rabbinic law, as well as customs and traditions.Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life; Jewish...

Shami Yemenite Jews were strongly influenced by SyrianSyrian JewsSyrian Jews are Jews who inhabit the region of the modern state of Syria, and their descendants born outside Syria. Syrian Jews derive their origin from two groups: from the Jews who inhabited the region of today's Syria from ancient times Syrian Jews are Jews who inhabit the region of the modern...

Sephardi JewsSephardi JewsSephardi Jews is a general term referring to the descendants of the Jews who lived in the Iberian Peninsula before their expulsion in the Spanish Inquisition. It can also refer to those who use a Sephardic style of liturgy or would otherwise define themselves in terms of the Jewish customs and...

, though on some issues they rejected the later European codes of Jewish law, and instead followed the earlier decisions of Maimonides. Most Yemenite Jews living today follow the Shami customs. The Shami rite was always more prevalent, even 50 years ago.

- The "Rambamists" are followers of, or to some extent influenced by, the Dor DaimDor DaimThe Dardaim or Dor daim , are adherents of the Dor Deah movement in Judaism. That movement was founded in 19th century Yemen by Rabbi Yiḥyah Qafiḥ, and had its own network of synagogues and schools.Its objects were:...

movement, and are strict followers of Talmudic law as compiled by MaimonidesMaimonidesMoses ben-Maimon, called Maimonides and also known as Mūsā ibn Maymūn in Arabic, or Rambam , was a preeminent medieval Jewish philosopher and one of the greatest Torah scholars and physicians of the Middle Ages...

, aka "Rambam". They are regarded as a subdivision of the Baladi Jews, and claim to preserve the Baladi tradition in its pure form. They generally reject the ZoharZoharThe Zohar is the foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah and scriptural interpretations as well as material on Mysticism, mythical cosmogony, and mystical psychology...

and LurianicIsaac LuriaIsaac Luria , also called Yitzhak Ben Shlomo Ashkenazi acronym "The Ari" "Ari-Hakadosh", or "Arizal", meaning "The Lion", was a foremost rabbi and Jewish mystic in the community of Safed in the Galilee region of Ottoman Palestine...

Kabbalah altogether. Many of them object to terms like "Rambamist". In their eyes, they are simply following the most ancient preservation of Torah, which (according to their research) was recorded in the Mishneh Torah.

Dor Daim and Iqshim dispute

Towards the end of the 19th century new ideas began to reach Yemenite Jews from abroad. Hebrew newspapers began to arrive, and relations developed with Sephardic Jews, who came to Yemen from various Ottoman provinces to trade with the army and government officials.Two Jewish travelers, Joseph Halévy

Joseph Halévy

Joseph Halévy was an Ottoman born Jewish-French Orientalist and traveller.He did his most notable work was done in Yemen, which he crossed during 1869 to 1870 in search of Sabaean inscriptions, no European having traversed that land since AD 24; the result was a most valuable collection of 800...

, a French-trained Jewish Orientalist, and Edward Glaser, an Austrian-Jewish astronomer, in particular had a strong influence on a group of young Yemenite Jews, the most outstanding of whom was Rabbi Yiḥyah Qafiḥ. As a result of his contact with Halévy and Glaser, Qafiḥ introduced modern content into the educational system. Qafiḥ opened a new school and, in addition to traditional subjects, introduced arithmetic, Hebrew and Arabic, with the grammar of both languages. The curriculum also included subjects such as natural science, history, geography, astronomy, sports and Turkish.

The Dor Daim and Iqshim dispute about the Zohar literature broke out in 1913, inflamed Sana'a

Sana'a

-Districts:*Al Wahdah District*As Sabain District*Assafi'yah District*At Tahrir District*Ath'thaorah District*Az'zal District*Bani Al Harith District*Ma'ain District*Old City District*Shu'aub District-Old City:...

's Jewish community, and split into two rival groups, that maintained separate communal institutions until the late 1940s. Rabbi Qafiḥ and his friends were the leaders of a group of Maimonideans called Dor Daim

Dor Daim

The Dardaim or Dor daim , are adherents of the Dor Deah movement in Judaism. That movement was founded in 19th century Yemen by Rabbi Yiḥyah Qafiḥ, and had its own network of synagogues and schools.Its objects were:...

(the "generation of knowledge"). Their goal was to bring Yemenite Jews back to the original Maimonidean method of understanding Judaism that existed in pre-17th century Yemen

Yemen

The Republic of Yemen , commonly known as Yemen , is a country located in the Middle East, occupying the southwestern to southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, the Red Sea to the west, and Oman to the east....

.

Similar to certain Spanish and Portuguese Jews

Spanish and Portuguese Jews

Spanish and Portuguese Jews are a distinctive sub-group of Sephardim who have their main ethnic origins within the Jewish communities of the Iberian peninsula and who shaped communities mainly in Western Europe and the Americas from the late 16th century on...

(Western Sephardi Jews

Sephardi Jews

Sephardi Jews is a general term referring to the descendants of the Jews who lived in the Iberian Peninsula before their expulsion in the Spanish Inquisition. It can also refer to those who use a Sephardic style of liturgy or would otherwise define themselves in terms of the Jewish customs and...

), the Dor Daim

Dor Daim

The Dardaim or Dor daim , are adherents of the Dor Deah movement in Judaism. That movement was founded in 19th century Yemen by Rabbi Yiḥyah Qafiḥ, and had its own network of synagogues and schools.Its objects were:...

rejected the Zohar

Zohar

The Zohar is the foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah and scriptural interpretations as well as material on Mysticism, mythical cosmogony, and mystical psychology...

, a book of esoteric mysticism. They felt that the Kabbalah based on the Zohar was irrational, alien, and inconsistent with the true reasonable nature of Judaism. In 1913, when it seemed that Rabbi Qafiḥ, then headmaster of the new Jewish school and working closely with the Ottoman authorities, enjoyed sufficient political support, the Dor Daim made its views public and tried to convince the entire community to accept them. Many of the non-Dor Dai elements of the community rejected the Dor Dai concepts. The opposition, the Iqshim, headed by Rabbi Yaḥya Yiṣḥaq, the Hakham Bashi

Hakham Bashi

Hakham Bashi is the Turkish name for the Chief Rabbi of the nation's Jewish community.-History:The institution of the Hakham Bashi was established by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, as part of the millet system for governing exceedingly diverse subjects according to their own laws and authorities...

, refused to deviate from the accepted customs and the study of Zohar. One of the Iqshim's targets in the fight against Rabbi Qafiḥ was his modern Turkish-Jewish school. Due to the Dor Daim and Iqshim dispute, the school closed 5 years after it was opened, before the educational system could develop a reserve of young people who had been exposed to its ideas.

Form of Hebrew

There are two main pronunciations of Yemenite Hebrew, considered by many scholars to be the most accurate modern day form of Biblical Hebrew, although there are technically a total of five that relate to the regions of Yemen. In the Yemenite dialect, all Hebrew lettersHebrew alphabet

The Hebrew alphabet , known variously by scholars as the Jewish script, square script, block script, or more historically, the Assyrian script, is used in the writing of the Hebrew language, as well as other Jewish languages, most notably Yiddish, Ladino, and Judeo-Arabic. There have been two...

have a distinct sound, except for the letters ס sāmekh and ש śîn. The Sanaani Hebrew pronunciation (used by the majority) has been indirectly critiqued by Saadia Gaon

Saadia Gaon

Saʻadiah ben Yosef Gaon was a prominent rabbi, Jewish philosopher, and exegete of the Geonic period.The first important rabbinic figure to write extensively in Arabic, he is considered the founder of Judeo-Arabic literature...

since it contains the Hebrew letters jimmel and guf, which he rules is incorrect. There are Yemenite scholars, such as Rabbi Ratzon Arusi, who say that such a perspective is a misunderstanding of Saadia Gaon's words.

- Pronunciation Chart 1

- Pronunciation Chart 2

Rabbi Mazuz postulates this hypothesis through the Jerban (Tunisia

Tunisia

Tunisia , officially the Tunisian RepublicThe long name of Tunisia in other languages used in the country is: , is the northernmost country in Africa. It is a Maghreb country and is bordered by Algeria to the west, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Its area...

) Jewish dialect's use of gimmel and quf, switching to jimmel and guf when talking with Gentiles in the Arabic dialect of Jerba. Some feel that the Shar'abi pronunciation of Yemen is more accurate and similar to the Babylonian

History of the Jews in Iraq

The history of the Jews in Iraq is documented from the time of the Babylonian captivity c. 586 BCE. Iraqi Jews constitute one of the world's oldest and most historically significant Jewish communities....

dialect since they both use a gimmel and quf instead of the jimmel and guf. While Jewish boys learned Hebrew since the age of 3, it was used primarily as a liturgical and scholarly language. In daily life, Yemenite Jews spoke in regional Judeo-Arabic

Judeo-Yemenite

Judeo-Yemeni Arabic is a variety of Arabic spoken by Jews living or formerly living in Yemen. 50,000 speakers now live in Israel, 1,000 remain in Yemen. The language is quite different from mainstream Yemeni Arabic. The language may be split into the subdialects of San`a, `Aden, Be:da, and Habban....

.

Writings

Tanakh