William Bradford Huie

Encyclopedia

William Bradford "Bill" Huie (November 13, 1910 – November 20, 1986) was an American

journalist, editor, publisher, television interviewer, screenwriter, lecturer, and novelist.

, Alabama

, Huie was the son of John Bradford and Margaret Lois Brindley Huie, and was the eldest of three children. He attended Morgan County High School and graduated as class valedictorian

. He then attended the University of Alabama

, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1930. From 1932 to 1936, Huie worked for the newspaper The Birmingham Post

. In 1934, he married his grammar school sweetheart, Ruth Puckett. Their wedding took place in her parents' home in Hartselle, and Huie later immortalized the scene in his largely autobiographical first novel, Mud on the Stars (1942).

Huie's first national recognition came with the article "How To Keep Football Stars In College" (Collier's Weekly

, January 1, 1941). This piece was about the University of Alabama football program in the 1940s and included controversial quotations such as: "We who have recruited Alabama's players know who our competitors have been. And we've offered no higher prices than were necessary to compete in the open market." Huie's relationship to the football program was unclear, but the views he reported foreshadow those of the famous Paul "Bear" Bryant

.

During World War II

, he served in the United States Navy

, for a time as aide to Vice Admiral Ben Moreell

of the famous Seabees. While chronicling the wartime activity of the Seabees, Lieutenant Huie had special permission to continue his own writing projects, both fiction and nonfiction, dealing primarily with the war. His Navy experiences, including his participation in D-Day

, would become the basis for his 1959 novel The Americanization of Emily

, adapted into the 1964 film of the same name starring James Garner

and Julie Andrews

. Both Garner and Andrews consider it the personal favorite of their films.

Released from the Navy in 1945, Huie went immediately to the Pacific theater

as a war correspondent. His experiences at Iwo Jima

became the basis for the nonfiction work "The Hero of Iwo Jima," published in The Hero of Iwo Jima and Other Stories in 1962, the tragic story of flag-raiser Ira Hayes

. Huie's account was developed into the 1961 film The Outsider with Tony Curtis

. His experiences in Hawaii

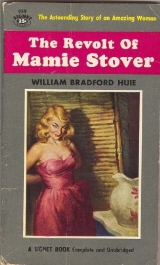

during the war became the basis for the novel The Revolt of Mamie Stover

(1951), which was developed into the 1956 film of the same name

starring Jane Russell

.

Before the war, Huie had been writing for The American Mercury

, the famous literary magazine founded by H.L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan

. Like Mencken, Huie was a critic of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

's "New Deal

" policies during the Great Depression

. After the war, he returned to the Mercury, becoming associate editor, then editor. In 1950, publisher Clendenin J. Ryan

bought the magazine. Ryan and editor Huie sought to develop the magazine into a journal of the fledgling American conservative

intellectual movement, opening its pages to new, mass-appeal writers such as evangelist Billy Graham

and long-time Federal Bureau of Investigations director J. Edgar Hoover

. Young William F. Buckley, future National Review

founder and editor, was one of Huie's early staffers.

By the mid-1950s, however, Huie and Ryan were unable to overcome financial difficulties and were forced to sell the magazine to one of its investors, Russell Maguire. After Huie's departure, Maguire and other owners drove The New American Mercury, in author William A. Rusher

's phrase, "toward the fever swamps of anti-Semitism

," destroying its legitimacy and presaging its demise. To Huie's disgust, the journal which had once featured the work of W.E.B. Du Bois

and Langston Hughes

became a periodical advocating racism

.

From 1950 to 1955, Huie was a popular speaker traveling back and forth across the country on the professional lecture circuit. During the same period, he also became well known through his appearances on the weekly New York City

television

current events program Longines Chronoscope. As a co-editor of the hour-long talk show, he interviewed newsmakers John F. Kennedy

, Joseph McCarthy

, and Clare Booth Luce, as well as international dignitaries, politicians, scientists, and economists. His program coeditors included figures such as Henry Hazlitt

and Max Eastman

. Domestic issues, Congressional activity, military defense, the Olympics

, and foreign policy

were all topics discussed on the program.

Huie and his wife moved their permanent residence back to native Hartselle in the late 1950s. Ruth became a first grade schoolteacher, and he continued to write full-time at home as freelance journalist and novelist, traveling only periodically on work-related matters.

These were the early days of the Civil Rights Movement

, and Huie was called upon by periodicals such as the New York Herald Tribune

and Look

magazine to cover breaking events in the South. His 1956 book Ruby McCollum: Woman in the Suwannee Jail was written in collaboration with Zora Neale Hurston

, who had covered the first Ruby McCollum trial in Live Oak, Florida

for The Pittsburgh Courier. McCollum, a black woman, had shot and killed her physician and white lover, Senator-elect Dr. Leroy Adams, who was being groomed to run for Governor of Florida. Hurston, who was also an African-American, was not allowed to interview McCollum, so she called on Huie, who she thought might stand a better chance to convince the judge in the trial, Hal W. Adams, to grant an interview. However, not only was he not allowed to see McCollum, Huie was thereafter arrested on contempt of court charges, the judge citing him for "meddling" in a trial that "could embarrass the community." Huie was soon freed from jail and eventually pardoned years later. His book was banned

in Florida

, but Ebony, Time

, and other journals disseminated the story worldwide.

Huie also reported on the murder of African-American Chicago teenager Emmett Till

, and after a Mississippi

jury found the accused murderers of Till not guilty, he paid the killers themselves to describe how and why they committed the murders. Since they could not be tried again, the killers complied, and the story was published in Look

magazine. Some mainstream journalists expressed criticism of his "checkbook journalism," but Huie's account revealed the full truth behind the murders for the first time. He also reported on various Ku Klux Klan

activities, including the killing of "Freedom Summer

" workers James Chaney

, Andrew Goodman

, and Michael Schwerner

in articles, stories, and books such as Wolf Whistle (1959), The Klansman

(1965) and Three Lives for Mississippi (1965). Huie's activities caused the KKK

to burn a cross

on his front lawn in 1967.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. himself wrote the Introduction for the second edition of Huie's Three Lives for Mississippi, and he wrote that the book "is a part of the arsenal decent Americans can employ to make democracy for all truly a birthright and not a distant dream. It relates the story of an atrocity committed on our doorstep." Subsequent editions of the work also include an "Afterword" by Juan Williams

. In 1970, Huie published He Slew the Dreamer, the true story of the Memphis

assassination of King, for which he interviewed assassin James Earl Ray

.

Huie's book The Execution of Private Slovik

related the true story of World War II

G.I. Eddie Slovik

, the only soldier since the American Civil War

to be executed for desertion, a fate kept so quiet by the government that even Slovik's widow did not know how that her husband had died. After the book exposed the event and told Eddie's story, Huie and others tried for years to get the government to pay his widow a pension, but with no success, even though the most-watched television

movie before 1974 was NBC's The Execution of Private Slovik

, starring Martin Sheen

.

Ruth, Huie's wife of almost 40 years, died of cancer in 1973, following the death of his father just months before. In 1975, the same year that Alabama's Library Association honored him with Best Fiction Award for In the Hours of Night, Huie met Martha Hunt Robertson of Guntersville, Alabama

, an Art Instructor at a local college. They married in Huntsville, Alabama on July 16, 1977. She continued teaching at the college, and he continued to write, while they divided their time between their Hartselle and Guntersville homes. In a few years, the Huies moved to Scottsboro, Alabama

, and by 1985 they resettled in Guntersville.

On November 20, 1986, Huie died of a heart attack. Left unfinished or unpublished were works titled "The Ray of Hope," "Battle Without Song," "To Live and Die in Dixie," "The Q Secret," "Codsack Chronicles," and "Recollections of a Loner." His widow and sole heir donated the Huie papers to Ohio State University

, and she continues to represent her late husband's literary properties and manages ongoing projects.

Since 1974, the Alabama Authors Collection at Snead Community College's McCain Learning Resource Center, Boaz, Alabama

, has been documenting Huie's life and career and has a variety of artifacts, as well as all of his books. In November, 2006, the City of Hartselle renamed the local public library in honor of Huie. The William Bradford Huie Library of Hartselle has a permanent biographical display of Huie's work, as well as bibliographic resources. In 2007, the Guntersville Museum and Cultural Center added a William Bradford Huie component to its permanent collection.

Since Huie's death in 1986, dozens of publications have cited, quoted, referenced and analyzed his work. Recent examples include: David Halberstam

's The Fifties; both volumes of Reporting Civil Rights: American Journalism 1941-1963 and 1963-1973; The Race Beat

by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, 2006; and Devin McKinney's "An American Cuss," in Issue 57 of the Oxford American

, 2007. Huie's alma mater, the University of Alabama

, honored him posthumously with a Fine Arts Award as well as induction into the College of Communication and Information Sciences Hall of Fame.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

journalist, editor, publisher, television interviewer, screenwriter, lecturer, and novelist.

Biography

Born in HartselleHartselle, Alabama

Hartselle is the second largest city in Morgan County, Alabama, United States, about south of Decatur, and is included in the Decatur Metropolitan Area, and the Huntsville-Decatur Combined Statistical Area. As of the 2006 census estimates, the population of the city is 13,479. Hartselle was...

, Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

, Huie was the son of John Bradford and Margaret Lois Brindley Huie, and was the eldest of three children. He attended Morgan County High School and graduated as class valedictorian

Valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title conferred upon the student who delivers the closing or farewell statement at a graduation ceremony. Usually, the valedictorian is the highest ranked student among those graduating from an educational institution...

. He then attended the University of Alabama

University of Alabama

The University of Alabama is a public coeducational university located in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, United States....

, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1930. From 1932 to 1936, Huie worked for the newspaper The Birmingham Post

Birmingham Post

The Birmingham Post newspaper was originally published under the name Daily Post in Birmingham, England, in 1857 by John Frederick Feeney. It was the largest selling broadsheet in the West Midlands, though it faced little if any competition in this category. It changed to tabloid size in 2008...

. In 1934, he married his grammar school sweetheart, Ruth Puckett. Their wedding took place in her parents' home in Hartselle, and Huie later immortalized the scene in his largely autobiographical first novel, Mud on the Stars (1942).

Huie's first national recognition came with the article "How To Keep Football Stars In College" (Collier's Weekly

Collier's Weekly

Collier's Weekly was an American magazine founded by Peter Fenelon Collier and published from 1888 to 1957. With the passage of decades, the title was shortened to Collier's....

, January 1, 1941). This piece was about the University of Alabama football program in the 1940s and included controversial quotations such as: "We who have recruited Alabama's players know who our competitors have been. And we've offered no higher prices than were necessary to compete in the open market." Huie's relationship to the football program was unclear, but the views he reported foreshadow those of the famous Paul "Bear" Bryant

Bear Bryant

Paul William "Bear" Bryant was an American college football player and coach. He was best known as the longtime head coach of the University of Alabama football team. During his 25-year tenure as Alabama's head coach, he amassed six national championships and thirteen conference championships...

.

During World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, he served in the United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

, for a time as aide to Vice Admiral Ben Moreell

Ben Moreell

Admiral Ben Moreell was the chief of the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Yards and Docks and of the Civil Engineer Corps. Best known to the American public as the Father of the Navy's Seabees, Admiral Ben Moreell's life spanned eight decades, two world wars, a great depression and the evolution of the...

of the famous Seabees. While chronicling the wartime activity of the Seabees, Lieutenant Huie had special permission to continue his own writing projects, both fiction and nonfiction, dealing primarily with the war. His Navy experiences, including his participation in D-Day

D-Day

D-Day is a term often used in military parlance to denote the day on which a combat attack or operation is to be initiated. "D-Day" often represents a variable, designating the day upon which some significant event will occur or has occurred; see Military designation of days and hours for similar...

, would become the basis for his 1959 novel The Americanization of Emily

The Americanization of Emily

The Americanization of Emily is a 1964 American comedy-drama war film written by Paddy Chayefsky and directed by Arthur Hiller, loosely adapted from the novel of the same name by William Bradford Huie who had been a SeaBee officer on D-Day....

, adapted into the 1964 film of the same name starring James Garner

James Garner

James Garner is an American film and television actor, one of the first Hollywood actors to excel in both media. He has starred in several television series spanning a career of more than five decades...

and Julie Andrews

Julie Andrews

Dame Julia Elizabeth Andrews, DBE is an English film and stage actress, singer, and author. She is the recipient of Golden Globe, Emmy, Grammy, BAFTA, People's Choice Award, Theatre World Award, Screen Actors Guild and Academy Award honors...

. Both Garner and Andrews consider it the personal favorite of their films.

Released from the Navy in 1945, Huie went immediately to the Pacific theater

Pacific Ocean theater of World War II

The Pacific Ocean theatre was one of four major naval theatres of war of World War II, which pitted the forces of Japan against those of the United States, the British Commonwealth, the Netherlands and France....

as a war correspondent. His experiences at Iwo Jima

Iwo Jima

Iwo Jima, officially , is an island of the Japanese Volcano Islands chain, which lie south of the Ogasawara Islands and together with them form the Ogasawara Archipelago. The island is located south of mainland Tokyo and administered as part of Ogasawara, one of eight villages of Tokyo...

became the basis for the nonfiction work "The Hero of Iwo Jima," published in The Hero of Iwo Jima and Other Stories in 1962, the tragic story of flag-raiser Ira Hayes

Ira Hayes

Ira Hamilton Hayes was a Pima Native American and an American Marine who was one of the six men immortalized in the iconic photograph of the flag raising on Iwo Jima during World War II. Hayes was an enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Community in Sacaton, Arizona, and enlisted in the Marine...

. Huie's account was developed into the 1961 film The Outsider with Tony Curtis

Tony Curtis

Tony Curtis was an American film actor whose career spanned six decades, but had his greatest popularity during the 1950s and early 1960s. He acted in over 100 films in roles covering a wide range of genres, from light comedy to serious drama...

. His experiences in Hawaii

Hawaii

Hawaii is the newest of the 50 U.S. states , and is the only U.S. state made up entirely of islands. It is the northernmost island group in Polynesia, occupying most of an archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean, southwest of the continental United States, southeast of Japan, and northeast of...

during the war became the basis for the novel The Revolt of Mamie Stover

The Revolt of Mamie Stover

The Revolt of Mamie Stover is a 1951 novel by William Bradford Huie about a Mississippi prostitute, later a war profiteer in Honolulu. A movie version directed by Raoul Walsh was filmed in 1956 with Jane Russell in the title role....

(1951), which was developed into the 1956 film of the same name

The Revolt of Mamie Stover (film)

The Revolt of Mamie Stover is a romantic drama film made by Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation. It was directed by Raoul Walsh and produced by Buddy Adler from a screenplay by Sydney Boehm based on the novel of the same name by William Bradford Huie.The film stars Jane Russell and Richard Egan...

starring Jane Russell

Jane Russell

Jane Russell was an American film actress and was one of Hollywood's leading sex symbols in the 1940s and 1950s....

.

Before the war, Huie had been writing for The American Mercury

The American Mercury

The American Mercury was an American magazine published from 1924 to 1981. It was founded as the brainchild of H. L. Mencken and drama critic George Jean Nathan. The magazine featured writing by some of the most important writers in the United States through the 1920s and 1930s...

, the famous literary magazine founded by H.L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan

George Jean Nathan

George Jean Nathan was an American drama critic and editor.-Early life:Nathan was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana...

. Like Mencken, Huie was a critic of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

's "New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

" policies during the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

. After the war, he returned to the Mercury, becoming associate editor, then editor. In 1950, publisher Clendenin J. Ryan

Clendenin J. Ryan

Clendenin James Ryan, Jr. was an American businessman best known as the publisher and owner of The American Mercury magazine, published in Baltimore, Maryland in the early 1950s when McCarthyism was at it strongest....

bought the magazine. Ryan and editor Huie sought to develop the magazine into a journal of the fledgling American conservative

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

intellectual movement, opening its pages to new, mass-appeal writers such as evangelist Billy Graham

Billy Graham

William Franklin "Billy" Graham, Jr. is an American evangelical Christian evangelist. As of April 25, 2010, when he met with Barack Obama, Graham has spent personal time with twelve United States Presidents dating back to Harry S. Truman, and is number seven on Gallup's list of admired people for...

and long-time Federal Bureau of Investigations director J. Edgar Hoover

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover was the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the United States. Appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation—predecessor to the FBI—in 1924, he was instrumental in founding the FBI in 1935, where he remained director until his death in 1972...

. Young William F. Buckley, future National Review

National Review

National Review is a biweekly magazine founded by the late author William F. Buckley, Jr., in 1955 and based in New York City. It describes itself as "America's most widely read and influential magazine and web site for conservative news, commentary, and opinion."Although the print version of the...

founder and editor, was one of Huie's early staffers.

By the mid-1950s, however, Huie and Ryan were unable to overcome financial difficulties and were forced to sell the magazine to one of its investors, Russell Maguire. After Huie's departure, Maguire and other owners drove The New American Mercury, in author William A. Rusher

William A. Rusher

William Allen Rusher was an American lawyer, author, activist, speaker, debater, and conservative syndicated columnist. He was one of the founders of the conservative movement and was one of its most prominent spokesmen for thirty years.- Early life :Rusher was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1923...

's phrase, "toward the fever swamps of anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

," destroying its legitimacy and presaging its demise. To Huie's disgust, the journal which had once featured the work of W.E.B. Du Bois

W.E.B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author, and editor. Born in Massachusetts, Du Bois attended Harvard, where he was the first African American to earn a doctorate...

and Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance...

became a periodical advocating racism

Racism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

.

From 1950 to 1955, Huie was a popular speaker traveling back and forth across the country on the professional lecture circuit. During the same period, he also became well known through his appearances on the weekly New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

television

Television

Television is a telecommunication medium for transmitting and receiving moving images that can be monochrome or colored, with accompanying sound...

current events program Longines Chronoscope. As a co-editor of the hour-long talk show, he interviewed newsmakers John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

, Joseph McCarthy

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond "Joe" McCarthy was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957...

, and Clare Booth Luce, as well as international dignitaries, politicians, scientists, and economists. His program coeditors included figures such as Henry Hazlitt

Henry Hazlitt

Henry Stuart Hazlitt was an American economist, philosopher, literary critic and journalist for such publications as The Wall Street Journal, The Nation, The American Mercury, Newsweek, and The New York Times...

and Max Eastman

Max Eastman

Max Forrester Eastman was an American writer on literature, philosophy and society, a poet, and a prominent political activist. For many years, Eastman was a supporter of socialism, a leading patron of the Harlem Renaissance and an activist for a number of liberal and radical causes...

. Domestic issues, Congressional activity, military defense, the Olympics

Olympic Games

The Olympic Games is a major international event featuring summer and winter sports, in which thousands of athletes participate in a variety of competitions. The Olympic Games have come to be regarded as the world’s foremost sports competition where more than 200 nations participate...

, and foreign policy

Foreign policy

A country's foreign policy, also called the foreign relations policy, consists of self-interest strategies chosen by the state to safeguard its national interests and to achieve its goals within international relations milieu. The approaches are strategically employed to interact with other countries...

were all topics discussed on the program.

Huie and his wife moved their permanent residence back to native Hartselle in the late 1950s. Ruth became a first grade schoolteacher, and he continued to write full-time at home as freelance journalist and novelist, traveling only periodically on work-related matters.

These were the early days of the Civil Rights Movement

Civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a worldwide political movement for equality before the law occurring between approximately 1950 and 1980. In many situations it took the form of campaigns of civil resistance aimed at achieving change by nonviolent forms of resistance. In some situations it was...

, and Huie was called upon by periodicals such as the New York Herald Tribune

New York Herald Tribune

The New York Herald Tribune was a daily newspaper created in 1924 when the New York Tribune acquired the New York Herald.Other predecessors, which had earlier merged into the New York Tribune, included the original The New Yorker newsweekly , and the Whig Party's Log Cabin.The paper was home to...

and Look

Look (American magazine)

Look was a bi-weekly, general-interest magazine published in Des Moines, Iowa from 1937 to 1971, with more of an emphasis on photographs than articles...

magazine to cover breaking events in the South. His 1956 book Ruby McCollum: Woman in the Suwannee Jail was written in collaboration with Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston was an American folklorist, anthropologist, and author during the time of the Harlem Renaissance...

, who had covered the first Ruby McCollum trial in Live Oak, Florida

Live Oak, Florida

Live Oak is a city in Suwannee County, Florida. The city is the county seat of Suwannee County and is located east of Tallahassee, Florida. The population was 6,480 at the 2000 census. As of 2004, the population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau is 6,828 ....

for The Pittsburgh Courier. McCollum, a black woman, had shot and killed her physician and white lover, Senator-elect Dr. Leroy Adams, who was being groomed to run for Governor of Florida. Hurston, who was also an African-American, was not allowed to interview McCollum, so she called on Huie, who she thought might stand a better chance to convince the judge in the trial, Hal W. Adams, to grant an interview. However, not only was he not allowed to see McCollum, Huie was thereafter arrested on contempt of court charges, the judge citing him for "meddling" in a trial that "could embarrass the community." Huie was soon freed from jail and eventually pardoned years later. His book was banned

Censorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

in Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

, but Ebony, Time

Time (magazine)

Time is an American news magazine. A European edition is published from London. Time Europe covers the Middle East, Africa and, since 2003, Latin America. An Asian edition is based in Hong Kong...

, and other journals disseminated the story worldwide.

Huie also reported on the murder of African-American Chicago teenager Emmett Till

Emmett Till

Emmett Louis "Bobo" Till was an African-American boy who was murdered in Mississippi at the age of 14 after reportedly flirting with a white woman. Till was from Chicago, Illinois visiting his relatives in the Mississippi Delta region when he spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the married...

, and after a Mississippi

Mississippi

Mississippi is a U.S. state located in the Southern United States. Jackson is the state capital and largest city. The name of the state derives from the Mississippi River, which flows along its western boundary, whose name comes from the Ojibwe word misi-ziibi...

jury found the accused murderers of Till not guilty, he paid the killers themselves to describe how and why they committed the murders. Since they could not be tried again, the killers complied, and the story was published in Look

Look (American magazine)

Look was a bi-weekly, general-interest magazine published in Des Moines, Iowa from 1937 to 1971, with more of an emphasis on photographs than articles...

magazine. Some mainstream journalists expressed criticism of his "checkbook journalism," but Huie's account revealed the full truth behind the murders for the first time. He also reported on various Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

activities, including the killing of "Freedom Summer

Freedom Summer

Freedom Summer was a campaign in the United States launched in June 1964 to attempt to register as many African American voters as possible in Mississippi which had historically excluded most blacks from voting...

" workers James Chaney

James Chaney

James Earl "J.E." Chaney , from Meridian, Mississippi, was one of three American civil rights workers who were murdered during Freedom Summer by members of the Ku Klux Klan near Philadelphia...

, Andrew Goodman

Andrew Goodman

Andrew Goodman was one of three American civil rights activists murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi, during Freedom Summer in 1964 by members of the Ku Klux Klan.-Early life and education:...

, and Michael Schwerner

Michael Schwerner

Michael Henry Schwerner , was one of three Congress of Racial Equality field workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, by the Ku Klux Klan in response to their civil rights work, which included promoting voting registration among Mississippi African Americans...

in articles, stories, and books such as Wolf Whistle (1959), The Klansman

The Klansman

The Klansman is a 1974 American motion picture drama based on the book of the same name by William Bradford Huie. It was directed by Terence Young and starred Lee Marvin, Richard Burton, O.J. Simpson,Lola Falana and Linda Evans.-Plot:...

(1965) and Three Lives for Mississippi (1965). Huie's activities caused the KKK

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

to burn a cross

Cross burning

Cross burning or cross lighting is a practice widely associated with the Ku Klux Klan, although the historical practice long predates the Klan's inception...

on his front lawn in 1967.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. himself wrote the Introduction for the second edition of Huie's Three Lives for Mississippi, and he wrote that the book "is a part of the arsenal decent Americans can employ to make democracy for all truly a birthright and not a distant dream. It relates the story of an atrocity committed on our doorstep." Subsequent editions of the work also include an "Afterword" by Juan Williams

Juan Williams

Juan Williams is an American journalist and political analyst for Fox News Channel, he was born in Panama on April 10, 1954. He also writes for several newspapers including The Washington Post, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal and has been published in magazines such as The Atlantic...

. In 1970, Huie published He Slew the Dreamer, the true story of the Memphis

Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the southwestern corner of the U.S. state of Tennessee, and the county seat of Shelby County. The city is located on the 4th Chickasaw Bluff, south of the confluence of the Wolf and Mississippi rivers....

assassination of King, for which he interviewed assassin James Earl Ray

James Earl Ray

James Earl Ray was an American criminal convicted of the assassination of civil rights and anti-war activist Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr....

.

Huie's book The Execution of Private Slovik

The Execution of Private Slovik

The Execution of Private Slovik is a nonfiction book by William Bradford Huie, published in 1954, and an American made-for-television movie that aired on NBC on March 13, 1974. The film was written for the screen by...

related the true story of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

G.I. Eddie Slovik

Eddie Slovik

Edward Donald Slovik was a private in the United States Army during World War II and the only American soldier to be court-martialled and executed for desertion since the American Civil War....

, the only soldier since the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

to be executed for desertion, a fate kept so quiet by the government that even Slovik's widow did not know how that her husband had died. After the book exposed the event and told Eddie's story, Huie and others tried for years to get the government to pay his widow a pension, but with no success, even though the most-watched television

Television

Television is a telecommunication medium for transmitting and receiving moving images that can be monochrome or colored, with accompanying sound...

movie before 1974 was NBC's The Execution of Private Slovik

The Execution of Private Slovik

The Execution of Private Slovik is a nonfiction book by William Bradford Huie, published in 1954, and an American made-for-television movie that aired on NBC on March 13, 1974. The film was written for the screen by...

, starring Martin Sheen

Martin Sheen

Ramón Gerardo Antonio Estévez , better known by his stage name Martin Sheen, is an American film actor best known for his performances in the films Badlands and Apocalypse Now , and in the television series The West Wing from 1999 to 2006.He is considered one of the best actors never to be...

.

Ruth, Huie's wife of almost 40 years, died of cancer in 1973, following the death of his father just months before. In 1975, the same year that Alabama's Library Association honored him with Best Fiction Award for In the Hours of Night, Huie met Martha Hunt Robertson of Guntersville, Alabama

Guntersville, Alabama

Guntersville is a city in Marshall County, Alabama, United States and is included in the Huntsville-Decatur Combined Statistical Area. At the 2010 census, the population of the city was 8,197. The city is the county seat of Marshall County. Guntersville is located in a HUBZone as identified by the...

, an Art Instructor at a local college. They married in Huntsville, Alabama on July 16, 1977. She continued teaching at the college, and he continued to write, while they divided their time between their Hartselle and Guntersville homes. In a few years, the Huies moved to Scottsboro, Alabama

Scottsboro, Alabama

Scottsboro is a city in Jackson County, Alabama, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population of the city is 14,770. Named for its founder Robert Scott, the city is the county seat of Jackson County....

, and by 1985 they resettled in Guntersville.

On November 20, 1986, Huie died of a heart attack. Left unfinished or unpublished were works titled "The Ray of Hope," "Battle Without Song," "To Live and Die in Dixie," "The Q Secret," "Codsack Chronicles," and "Recollections of a Loner." His widow and sole heir donated the Huie papers to Ohio State University

Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly referred to as Ohio State, is a public research university located in Columbus, Ohio. It was originally founded in 1870 as a land-grant university and is currently the third largest university campus in the United States...

, and she continues to represent her late husband's literary properties and manages ongoing projects.

Since 1974, the Alabama Authors Collection at Snead Community College's McCain Learning Resource Center, Boaz, Alabama

Boaz, Alabama

Boaz is a city in Etowah and Marshall Counties in the U.S. state of Alabama. It is part of the 'Gadsden, Alabama Metropolitan Statistical Area'. As of the 2010 census, the population of the city is 9,551. Boaz is known mainly for its outlet shops....

, has been documenting Huie's life and career and has a variety of artifacts, as well as all of his books. In November, 2006, the City of Hartselle renamed the local public library in honor of Huie. The William Bradford Huie Library of Hartselle has a permanent biographical display of Huie's work, as well as bibliographic resources. In 2007, the Guntersville Museum and Cultural Center added a William Bradford Huie component to its permanent collection.

Since Huie's death in 1986, dozens of publications have cited, quoted, referenced and analyzed his work. Recent examples include: David Halberstam

David Halberstam

David Halberstam was an American Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, author and historian, known for his early work on the Vietnam War, his work on politics, history, the Civil Rights Movement, business, media, American culture, and his later sports journalism.-Early life and education:Halberstam...

's The Fifties; both volumes of Reporting Civil Rights: American Journalism 1941-1963 and 1963-1973; The Race Beat

The Race Beat

The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation is a Pulitzer Prize-winning book written in 2006 by journalists Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff. The book is about the African-American Civil Rights Movement in the United States, specifically about the role of...

by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, 2006; and Devin McKinney's "An American Cuss," in Issue 57 of the Oxford American

Oxford American

The Oxford American is an American quarterly literary magazine "dedicated to featuring the very best in Southern writing while documenting the complexity and vitality of the American South."-First publication:...

, 2007. Huie's alma mater, the University of Alabama

University of Alabama

The University of Alabama is a public coeducational university located in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, United States....

, honored him posthumously with a Fine Arts Award as well as induction into the College of Communication and Information Sciences Hall of Fame.

See also

- African-American Civil Rights Movement

- Civil Rights MovementCivil rights movementThe civil rights movement was a worldwide political movement for equality before the law occurring between approximately 1950 and 1980. In many situations it took the form of campaigns of civil resistance aimed at achieving change by nonviolent forms of resistance. In some situations it was...

- ConservatismConservatismConservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

Fiction

- Mud on the Stars (1942; reprinted with new material 1996) - (1960 film, Wild River)

- The Revolt of Mamie StoverThe Revolt of Mamie StoverThe Revolt of Mamie Stover is a 1951 novel by William Bradford Huie about a Mississippi prostitute, later a war profiteer in Honolulu. A movie version directed by Raoul Walsh was filmed in 1956 with Jane Russell in the title role....

(1951) - (1956 film) - The Americanization of EmilyThe Americanization of EmilyThe Americanization of Emily is a 1964 American comedy-drama war film written by Paddy Chayefsky and directed by Arthur Hiller, loosely adapted from the novel of the same name by William Bradford Huie who had been a SeaBee officer on D-Day....

(1959) - (1964 film) - Hotel Mamie Stover (1963)

- The KlansmanThe KlansmanThe Klansman is a 1974 American motion picture drama based on the book of the same name by William Bradford Huie. It was directed by Terence Young and starred Lee Marvin, Richard Burton, O.J. Simpson,Lola Falana and Linda Evans.-Plot:...

(1967) - (1974 film) - In the Hours of the Night (1975)

Nonfiction

- How To Keep Football Stars In College (1941)

- The Fight for Air Power (1942)

- Seabee Roads to Victory (1944)

- Can Do!: The Story of the Seabees (1944; reprinted with new material 1997)

- From Omaha to Okinawa: The Story of the Seabees (1945; reprinted with new material 1999)

- The Case against the Admirals: Why We Must Have a Unified Command (1946)

- Ruby McCollum: Woman in the Suwannee Jail (with Zora Neale Hurston) (1956)

- The Execution of Private SlovikThe Execution of Private SlovikThe Execution of Private Slovik is a nonfiction book by William Bradford Huie, published in 1954, and an American made-for-television movie that aired on NBC on March 13, 1974. The film was written for the screen by...

(1954; reprinted with new material 2004) - (1974 film) - Wolf Whistle and Other Stories (1959, retitled The Outsider and Other Stories in the UK, The Outsider 1961 film)

- The Hiroshima Pilot: The Case of Major Claude Eatherly (1964)

- Three Lives for Mississippi (1965; reprinted with new material 2000)

- He Slew the Dreamer: My Search with James Earl Ray for the Truth about the Murder of Martin Luther King (1970)

- A New Life To Live: Jimmy Putnam's Story (editor 1977)

- It's Me O Lord! (1979)

External links

- William Bradford Huie celebrated on The Southern Literary Trail

- "I’m In The Truth Business: William Bradford Huie" - The television series The Alabama Experience, produced by The University of Alabama Center for Public Television, profiles one of this century’s most successful and controversial writers. Copies of the show are available on DVD and VHS.

- "Slate: The Murder of Emmett Till" -- 2005 Slate overview of WBH's role in the investigation of the Emmett Till murder.

- "The Shocking Story of Approved Killing in Mississippi" by William Bradford Huie, Look Magazine, 1956

- Jonathan Yardley (Washington Post): "Mamie Stover: Blond Ambition"

- The Execution of Private Slovik by William Bradford Huie.

- Longines Chronoscope with Rep. John F. Kennedy (1952) William Bradford Huie and Harold Levine talk with Rep. John F. Kennedy