The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs

Encyclopedia

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

's first monograph

Monograph

A monograph is a work of writing upon a single subject, usually by a single author.It is often a scholarly essay or learned treatise, and may be released in the manner of a book or journal article. It is by definition a single document that forms a complete text in itself...

, and set out his theory

Theory

The English word theory was derived from a technical term in Ancient Greek philosophy. The word theoria, , meant "a looking at, viewing, beholding", and referring to contemplation or speculation, as opposed to action...

of the formation of coral reef

Coral reef

Coral reefs are underwater structures made from calcium carbonate secreted by corals. Coral reefs are colonies of tiny living animals found in marine waters that contain few nutrients. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, which in turn consist of polyps that cluster in groups. The polyps...

s and atoll

Atoll

An atoll is a coral island that encircles a lagoon partially or completely.- Usage :The word atoll comes from the Dhivehi word atholhu OED...

s. He conceived of the idea during the voyage of the Beagle

Second voyage of HMS Beagle

The second voyage of HMS Beagle, from 27 December 1831 to 2 October 1836, was the second survey expedition of HMS Beagle, under captain Robert FitzRoy who had taken over command of the ship on its first voyage after her previous captain committed suicide...

while still in South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

, before he had seen a coral island, and wrote it out as HMS Beagle

HMS Beagle

HMS Beagle was a Cherokee-class 10-gun brig-sloop of the Royal Navy. She was launched on 11 May 1820 from the Woolwich Dockyard on the River Thames, at a cost of £7,803. In July of that year she took part in a fleet review celebrating the coronation of King George IV of the United Kingdom in which...

crossed the Pacific Ocean

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

, completing his draft by November 1835. At the time there was great scientific interest in the way that coral reefs formed, and Captain Robert FitzRoy

Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy RN achieved lasting fame as the captain of HMS Beagle during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, and as a pioneering meteorologist who made accurate weather forecasting a reality...

's orders from the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

included the investigation of an atoll as an important scientific aim of the voyage. FitzRoy chose to survey the Keeling Islands

Cocos (Keeling) Islands

The Territory of the Cocos Islands, also called Cocos Islands and Keeling Islands, is a territory of Australia, located in the Indian Ocean, southwest of Christmas Island and approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka....

in the Indian Ocean

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the world's oceanic divisions, covering approximately 20% of the water on the Earth's surface. It is bounded on the north by the Indian Subcontinent and Arabian Peninsula ; on the west by eastern Africa; on the east by Indochina, the Sunda Islands, and...

. The results supported Darwin's theory that the various types of coral reefs and atolls could be explained by uplift

Tectonic uplift

Tectonic uplift is a geological process most often caused by plate tectonics which increases elevation. The opposite of uplift is subsidence, which results in a decrease in elevation. Uplift may be orogenic or isostatic.-Orogenic uplift:...

and subsidence

Subsidence

Subsidence is the motion of a surface as it shifts downward relative to a datum such as sea-level. The opposite of subsidence is uplift, which results in an increase in elevation...

of vast areas of the Earth's crust

Oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the part of Earth's lithosphere that surfaces in the ocean basins. Oceanic crust is primarily composed of mafic rocks, or sima, which is rich in iron and magnesium...

under the oceans.

The book was the first volume of three Darwin wrote about the geology

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

he had investigated during the voyage, and was widely recognised as a major scientific work that presented his deductions from all the available observations on this large subject. In 1853, Darwin was awarded the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

's Royal Medal for the monograph and for his work on barnacle

Barnacle

A barnacle is a type of arthropod belonging to infraclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea, and is hence related to crabs and lobsters. Barnacles are exclusively marine, and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters, typically in erosive settings. They are sessile suspension feeders, and have...

s. Darwin's theory that coral reefs formed as the islands and surrounding areas of crust subsided has been supported by modern investigations, and is no longer disputed, the cause of the subsidence and uplift of areas of crust has continued to be a subject of discussion.

Theory of coral atoll formation

When the Beagle set out in 1831, the formation of coralCoral

Corals are marine animals in class Anthozoa of phylum Cnidaria typically living in compact colonies of many identical individual "polyps". The group includes the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secrete calcium carbonate to form a hard skeleton.A coral "head" is a colony of...

atoll

Atoll

An atoll is a coral island that encircles a lagoon partially or completely.- Usage :The word atoll comes from the Dhivehi word atholhu OED...

s was a scientific puzzle. Advance notice of her sailing, given in the Athenaeum

Athenaeum (magazine)

The Athenaeum was a literary magazine published in London from 1828 to 1921. It had a reputation for publishing the very best writers of the age....

of 24 December, described investigation of this topic as "the most interesting part of the Beagles survey" with the prospect of "many points for investigation of a scientific nature beyond the mere occupation of the surveyor. In 1824 and 1825, French naturalists Quoy

Jean René Constant Quoy

Jean René Constant Quoy was a French zoologist.Along with Joseph Paul Gaimard he served as naturalist aboard La Coquille under Louis Isidore Duperrey during its circumnavigation of the globe , and the Astrolabe under the command of Jules Dumont d'Urville...

and Gaimard

Joseph Paul Gaimard

Joseph Paul Gaimard was a French naval surgeon and naturalist.Along with Jean René Constant Quoy he served as naturalist on the ships L'Uranie under Louis de Freycinet 1817-1820, and L'Astrolabe under Jules Dumont d'Urville 1826-1829...

had observed that the coral organisms lived at relatively shallow depths, but the islands appeared in deep ocean

Ocean

An ocean is a major body of saline water, and a principal component of the hydrosphere. Approximately 71% of the Earth's surface is covered by ocean, a continuous body of water that is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas.More than half of this area is over 3,000...

s. In books that were taken on the Beagle as references, Henry De la Beche

Henry De la Beche

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche FRS was an English geologist and palaeontologist who helped pioneer early geological survey methods.-Biography:...

, Frederick William Beechey

Frederick William Beechey

Frederick William Beechey was an English naval officer and geographer. He was the son of Sir William Beechey, RA., and was born in London.-Career:...

and Charles Lyell

Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, Kt FRS was a British lawyer and the foremost geologist of his day. He is best known as the author of Principles of Geology, which popularised James Hutton's concepts of uniformitarianism – the idea that the earth was shaped by slow-moving forces still in operation...

had published the opinion that the coral had grown on underwater mountains or volcanoes, with atolls taking the shape of underlying volcanic crater

Volcanic crater

A volcanic crater is a circular depression in the ground caused by volcanic activity. It is typically a basin, circular in form within which occurs a vent from which magma erupts as gases, lava, and ejecta. A crater can be of large dimensions, and sometimes of great depth...

s. The Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

instructions for the voyage stated:

As a student at the University of Edinburgh

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1583, is a public research university located in Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The university is deeply embedded in the fabric of the city, with many of the buildings in the historic Old Town belonging to the university...

in 1827, Darwin learnt about marine invertebrates while assisting the investigations of the anatomist

Anatomy

Anatomy is a branch of biology and medicine that is the consideration of the structure of living things. It is a general term that includes human anatomy, animal anatomy , and plant anatomy...

Robert Edmond Grant

Robert Edmond Grant

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS was born in Edinburgh and educated at Edinburgh University as a physician. He became one of the foremost biologists of the early 19th century at Edinburgh and subsequently the first Professor of Comparative Anatomy at University College London...

, and during his last year at the University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

in 1831, he had studied geology

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

under Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick was one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Devonian period of the geological timescale...

. So when he was unexpectedly offered a place on the Beagle expedition, as a gentleman naturalist he was well suited to FitzRoy's aim of having a companion able to examine geology on land while the ship's complement carried out its hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore oil exploration/drilling and related disciplines. Strong emphasis is placed on soundings, shorelines, tides, currents, sea floor and submerged...

. FitzRoy gave Darwin the first volume of Lyell's Principles of Geology

Principles of Geology

Principles of Geology, being an attempt to explain the former changes of the Earth's surface, by reference to causes now in operation, is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell....

before they left. On their first stop ashore at St Jago

Santiago, Cape Verde

Santiago , or Santiagu in Cape Verdean Creole, is the largest island of Cape Verde, its most important agricultural centre and home to half the nation’s population. At the time of Darwin's voyage it was called St. Jago....

island in January 1832, Darwin saw geological formations which he explained using Lyell's uniformitarian

Uniformitarianism (science)

In the philosophy of naturalism, the uniformitarianism assumption is that the same natural laws and processes that operate in the universe now, have always operated in the universe in the past and apply everywhere in the universe. It has included the gradualistic concept that "the present is the...

concept that forces still in operation made land slowly rise or fall over immense periods of time, and thought that he could write his own book on geology. Lyell's first volume included a brief outline of the idea that atolls were based on volcanic craters, and the second volume, which was sent to Darwin during the voyage, gave more detail. Darwin received it in November 1832.

While the Beagle surveyed the coasts of South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

from February 1832 to September 1835, Darwin made several trips inland and found extensive evidence that the continent was gradually rising. After witnessing an erupting volcano from the ship, he experienced an earthquake on 20 February 1835. In the following months he speculated that as the land was uplifted

Tectonic uplift

Tectonic uplift is a geological process most often caused by plate tectonics which increases elevation. The opposite of uplift is subsidence, which results in a decrease in elevation. Uplift may be orogenic or isostatic.-Orogenic uplift:...

, large areas of the ocean bed subsided

Subsidence

Subsidence is the motion of a surface as it shifts downward relative to a datum such as sea-level. The opposite of subsidence is uplift, which results in an increase in elevation...

. It struck him that this could explain the formation of atolls.

Darwin's theory followed from his understanding that coral polyp

Polyp

A polyp in zoology is one of two forms found in the phylum Cnidaria, the other being the medusa. Polyps are approximately cylindrical in shape and elongated at the axis of the body...

s thrive in the clean seas of the tropics where the water is agitated, but can only live within a limited depth of water, starting just below low tide. Where the level of the underlying land stays the same, the corals grow around the coast to form what he called fringing reefs, and can eventually grow out from the shore to become a barrier reef. Where the land is rising, fringing reefs can grow around the coast, but coral raised above sea level dies and becomes white limestone. If the land subsides slowly, the fringing reefs keep pace by growing upwards on a base of dead coral, and form a barrier reef enclosing a lagoon between the reef and the land. A barrier reef can encircle an island, and once the island sinks below sea level a roughly circular atoll of growing coral continues to keep up with the sea level, forming a central lagoon. Should the land subside too quickly or sea level rise too fast, the coral dies as it is below its habitable depth.

Investigation testing Darwin's theory

By the time that the Beagle set out for the Galápagos IslandsGalápagos Islands

The Galápagos Islands are an archipelago of volcanic islands distributed around the equator in the Pacific Ocean, west of continental Ecuador, of which they are a part.The Galápagos Islands and its surrounding waters form an Ecuadorian province, a national park, and a...

on 7 September 1835, Darwin had thought out the essentials of his theory of atoll formation. While he no longer favoured the concept that atolls formed on submerged volcanos, he noted some points on these islands which supported that idea: 16 volcanic craters resembled atolls in being raised slightly more on one side, and five hills appeared roughly equal in height. He then considered a topic which was compatible with either theory, the lack of coral reefs around the Galápagos Islands. One possibility was a lack of calcareous

Calcareous

Calcareous is an adjective meaning mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate, in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.-In zoology:...

matter around the islands, but his main proposal, which FitzRoy had suggested to him, was that the seas were too cold. As they sailed on, Darwin took note of the records of sea temperature kept in the ship's "Weather Journal".

He had his first glimpse of coral atolls as they passed Honden Island

Puka-Puka

Puka-Puka is a small coral atoll in the north-eastern Tuamotu Archipelago, sometimes included as a member of the Disappointment Islands. This atoll is quite isolated, the nearest land being Fakahina, located 182 km to the southwest....

on 9 November and sailed on through the Low or Dangerous Archipelago (Tuamotus

Tuamotus

The Tuamotus or the Tuamotu Archipelago are a chain of islands and atolls in French Polynesia. They form the largest chain of atolls in the world, spanning an area of the Pacific Ocean roughly the size of Western Europe...

). Arriving at Tahiti

Tahiti

Tahiti is the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia, located in the archipelago of the Society Islands in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is the economic, cultural and political centre of French Polynesia. The island was formed from volcanic activity and is high and mountainous...

on 15 November, Darwin saw it "encircled by a Coral reef separated from the shore by channels & basins of still water". He climbed the hills of Tahiti, and was strongly impressed by the sight across to the island of Eimeo

Moorea

Moʻorea is a high island in French Polynesia, part of the Society Islands, 17 km northwest of Tahiti. Its position is . Moʻorea means "yellow lizard" in Tahitian...

, where "The mountains abruptly rise out of a glassy lake, which is separated on all sides, by a narrow defined line of breakers, from the open sea. – Remove the central group of mountains, & there remains a Lagoon Isd." Rather than recording his findings about the coral reefs in his notes about the island, he wrote them up as the first full draft of his theory, an essay titled Coral Islands, dated 1835. They left Tahiti on 3 December, and Darwin probably wrote his essay as they sailed towards New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

where they arrived on 21 December. He described the polyp

Polyp

A polyp in zoology is one of two forms found in the phylum Cnidaria, the other being the medusa. Polyps are approximately cylindrical in shape and elongated at the axis of the body...

species building the coral on the barrier wall, flourishing in the heavy surf of breaking waves particularly on the windward side, and speculated on reasons that corals in the calm lagoon

Lagoon

A lagoon is a body of shallow sea water or brackish water separated from the sea by some form of barrier. The EU's habitat directive defines lagoons as "expanses of shallow coastal salt water, of varying salinity or water volume, wholly or partially separated from the sea by sand banks or shingle,...

did not grow so high. He concluded with a "remark that the general horizontal uplifting which I have proved has & is now raising upwards the greater part of S. America & as it would appear likewise of N. America, would of necessity be compensated by an equal subsidence in some other part of the world."

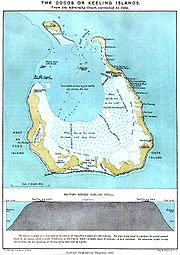

Keeling Islands

Coral

Corals are marine animals in class Anthozoa of phylum Cnidaria typically living in compact colonies of many identical individual "polyps". The group includes the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secrete calcium carbonate to form a hard skeleton.A coral "head" is a colony of...

atoll

Atoll

An atoll is a coral island that encircles a lagoon partially or completely.- Usage :The word atoll comes from the Dhivehi word atholhu OED...

to investigate how coral reef

Coral reef

Coral reefs are underwater structures made from calcium carbonate secreted by corals. Coral reefs are colonies of tiny living animals found in marine waters that contain few nutrients. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, which in turn consist of polyps that cluster in groups. The polyps...

s formed, particularly if they rose from the bottom of the sea or from the summits of extinct volcanoes, and to assess the effects of tide

Tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the moon and the sun and the rotation of the Earth....

s by measurement with specially constructed gauges. FitzRoy chose the Keeling Islands

Cocos (Keeling) Islands

The Territory of the Cocos Islands, also called Cocos Islands and Keeling Islands, is a territory of Australia, located in the Indian Ocean, southwest of Christmas Island and approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka....

in the Indian Ocean

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the world's oceanic divisions, covering approximately 20% of the water on the Earth's surface. It is bounded on the north by the Indian Subcontinent and Arabian Peninsula ; on the west by eastern Africa; on the east by Indochina, the Sunda Islands, and...

, and on arrival there on 1 April 1836, the entire crew set to work, first erecting FitzRoy's new design of a tide gauge that allowed readings to be taken from the shore. Boats were sent all around the island to carry out the survey, and despite being impeded by strong winds, they took numerous soundings

Sounding line

A sounding line or lead line is a length of thin rope with a plummet, generally of lead, at its end. Regardless of the actual composition of the plummet, it is still called a "lead."...

to establish depths around the atoll and in the lagoon

Lagoon

A lagoon is a body of shallow sea water or brackish water separated from the sea by some form of barrier. The EU's habitat directive defines lagoons as "expanses of shallow coastal salt water, of varying salinity or water volume, wholly or partially separated from the sea by sand banks or shingle,...

. FitzRoy noted the smooth and solid rock-like outer wall of the atoll, with most life thriving where the surf was most violent. He had great difficulty in establishing the depth reached by living coral, as pieces were hard to break off and the small anchors, hooks, grappling irons, and chains they used were all snapped off by the swell as soon as they tried to pull them up. He had more success using a sounding line with a bell-shaped lead weight armed with tallow

Tallow

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton fat, processed from suet. It is solid at room temperature. Unlike suet, tallow can be stored for extended periods without the need for refrigeration to prevent decomposition, provided it is kept in an airtight container to prevent oxidation.In industry,...

hardened with lime; this would be indented by any shape that it struck to give an exact impression of the bottom; it would also collect any fragments of coral or grains of sand.

These soundings were taken personally by FitzRoy, and the tallow from each sounding was cut off and taken on board to be examined by Darwin. The impressions taken on the steep outside slope of the reef were marked with the shapes of living corals, and otherwise were clean down to about 10 fathom

Fathom

A fathom is a unit of length in the imperial and the U.S. customary systems, used especially for measuring the depth of water.There are 2 yards in an imperial or U.S. fathom...

s (18 m); then at increasing depths, the tallow showed fewer such impressions and collected more grains of sand until it was evident that there were no living corals below about 20–30 fathom

Fathom

A fathom is a unit of length in the imperial and the U.S. customary systems, used especially for measuring the depth of water.There are 2 yards in an imperial or U.S. fathom...

s (36–55 m). Darwin carefully noted the location of the different types of coral around the reef and in the lagoon. In his diary, he described, "examining the very interesting yet simple structure & origin of these islands. The water being unusually smooth, I waded in as far as the living mounds of coral on which the swell of the open sea breaks. In some of the gullies & hollows, there were beautiful green & other colored fishes, & the forms & tints of many of the Zoophites were admirable. It is excusable to grow enthusiastic over the infinite numbers of organic beings with which the sea of the tropics, so prodigal of life, teems", though he cautioned against the "rather exuberant language" used by some naturalists.

As they left the islands after eleven days, Darwin wrote out a summary of his theory in his diary:

Publication of theory

When the Beagle returned on 2 October 1836, Darwin was already a celebrity in scientific circles, as in December 1835 University of CambridgeUniversity of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

Professor of Botany John Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow was an English clergyman, botanist and geologist. He is best remembered as friend and mentor to his pupil Charles Darwin.- Early life :...

had fostered his former pupil’s reputation by giving selected naturalists a pamphlet of Darwin’s geological letters. Charles Lyell eagerly met Darwin for the first time on 29 October, enthusiastic about the support this gave to his uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism (science)

In the philosophy of naturalism, the uniformitarianism assumption is that the same natural laws and processes that operate in the universe now, have always operated in the universe in the past and apply everywhere in the universe. It has included the gradualistic concept that "the present is the...

, and in May wrote to John Herschel

John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet KH, FRS ,was an English mathematician, astronomer, chemist, and experimental photographer/inventor, who in some years also did valuable botanical work...

that he was "very full of Darwin's new theory of Coral Islands, and have urged Whewell to make him read it at our next meeting. I must give up my volcanic crater theory for ever, though it cost me a pang at first, for it accounted for so much... the whole theory is knocked on the head, and the annular shape and central lagoon have nothing to do with volcanoes, nor even with a crateriform bottom.... Coral islands are the last efforts of drowning continents to lift their heads above water. Regions of elevation and subsidence in the ocean may be traced by the state of the coral reefs." Darwin presented his findings and theory in a paper which he read to the Geological Society of London

Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London is a learned society based in the United Kingdom with the aim of "investigating the mineral structure of the Earth"...

on 31 May 1837.

Darwin's first literary project was his Journal and Remarks on the natural history

Natural history

Natural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

of the expedition, now known as The Voyage of the Beagle

The Voyage of the Beagle

The Voyage of the Beagle is a title commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his Journal and Remarks, bringing him considerable fame and respect...

. In it he expanded his diary notes into a section on this theory, emphasising how the presence or absence of coral reefs and atolls can show whether the ocean bed is elevating or subsiding. At the same time he was privately speculating intensively about transmutation of species

Transmutation of species

Transmutation of species was a term used by Jean Baptiste Lamarck in 1809 for his theory that described the altering of one species into another, and the term is often used to describe 19th century evolutionary ideas that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection...

, and taking on other projects. He finished writing out his journal around the end of September, but then had the work of correcting proofs.

His tasks included finding experts to examine and report on his collections from the voyage. Darwin proposed to edit these reports, writing his own forewords and notes, and used his contacts to lobby for government sponsorship of publication of these findings as a large book. When a Treasury grant of £

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

1,000 was allocated at the end of August 1837, Darwin stretched the project to include the geology book that he had conceived in April 1832 at the first landfall in the voyage. He selected Smith, Elder & Co.

Smith, Elder & Co.

Smith, Elder & Co. was a firm of British publishers who were most noted for the works they published in the 19th century.The firm was founded by George Smith and Alexander Elder and successfully continued by George Murray Smith .They are notable for producing the first edition of the Dictionary...

as the publisher, and gave them unrealistic commitments on the timing of providing the text and illustrations. He assured the Treasury that the work would be good value, as the publisher would only require a small commission profit, and he himself would have no profit. From October he planned what became the multi-volume Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle

Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle

The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Under the Command of Captain Fitzroy, R.N., during the Years 1832 to 1836 is a 5-part book published unbound in nineteen numbers as they were ready, between February 1838 and October 1843...

on his collections, and began writing about the geology of volcanic islands.

In January 1838, Smith, Elder & Co. advertised the first part of Darwin's geology book, Geological observations on volcanic islands and coral formations, as a single octavo volume to be published that year. By the end of the month Darwin thought that his geology was "covering so much paper, & will take so much time" that it could be split into separate volumes (eventually Coral reefs was published first, followed by Volcanic islands in 1844, and South America in 1846). He also doubted that the treasury funds could cover all the geological writings. The first part of the zoology was published in February 1838, but Darwin found it a struggle to get the experts to produce their reports on his collections, and overwork led to illness. After a break to visit Scotland, he wrote up a major paper on the geological "roads" of Glen Roy

Glen Roy

Glen Roy in the Lochaber area of the Highlands of Scotland is a National Nature Reserve and is noted for the geological puzzle of the three roads ....

. On 5 October 1838 he noted in his diary, "Began Coral Paper: requires much reading".

In November 1838 Darwin proposed to his cousin Emma

Emma Darwin

Emma Darwin was the wife and first cousin of Charles Darwin, the English naturalist, scientist and author of On the Origin of Species...

, and they married in January 1839. As well as his other projects he continued to work on his ideas of evolution

Evolution

Evolution is any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations. Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organisation, including species, individual organisms and molecules such as DNA and proteins.Life on Earth...

as his "prime hobby", but repeated delays were caused by his illness

Charles Darwin's illness

For much of his adult life, Charles Darwin's health was repeatedly compromised by an uncommon combination of symptoms, leaving him severely debilitated for long periods of time...

. He sporadically restarted work on Coral Reefs, and on 9 May 1842 wrote to Emma, telling her he was

Publication and subsequent editions

The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs was published in May 1842, priced at 15 shillingShilling

The shilling is a unit of currency used in some current and former British Commonwealth countries. The word shilling comes from scilling, an accounting term that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times where it was deemed to be the value of a cow in Kent or a sheep elsewhere. The word is thought to derive...

s, and was well received. A second edition was published in 1874, extensively revised and rewritten to take into account James Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana was an American geologist, mineralogist and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcanic activity, and the origin and structure of continents and oceans around the world.-Early life and career:...

's 1872 publication Corals and Coral Islands, and work by Joseph Jukes

Joseph Jukes

Joseph Beete Jukes , born to John and Sophia Jukes at Summer Hill, Birmingham, England, was a renowned geologist, author of several geological manuals and served as a naturalist on the expeditions of HMS Fly .Jukes was educated at Wolverhampton, King Edward's School, Birmingham and St John's...

.

Structure of book

The book has a tightly logical structure, and presents a bold argument. Illustrations are used as an integral part of the argument, with numerous detailed charts and one large world map marked in colour showing all reefs known at that time. A brief introduction sets out the aims of the book..jpg)

Coral reef

Coral reefs are underwater structures made from calcium carbonate secreted by corals. Coral reefs are colonies of tiny living animals found in marine waters that contain few nutrients. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, which in turn consist of polyps that cluster in groups. The polyps...

, each chapter starting with a section giving a detailed description of the reef Darwin had most information about, which he presents as a typical example of the type. Subsequent sections in each chapter then describe other reefs in comparison with the typical example. In the first chapter, Darwin describes atoll

Atoll

An atoll is a coral island that encircles a lagoon partially or completely.- Usage :The word atoll comes from the Dhivehi word atholhu OED...

s and lagoon

Lagoon

A lagoon is a body of shallow sea water or brackish water separated from the sea by some form of barrier. The EU's habitat directive defines lagoons as "expanses of shallow coastal salt water, of varying salinity or water volume, wholly or partially separated from the sea by sand banks or shingle,...

islands, taking as his typical example his own detailed findings and the Beagle survey findings on the Keeling Islands

Cocos (Keeling) Islands

The Territory of the Cocos Islands, also called Cocos Islands and Keeling Islands, is a territory of Australia, located in the Indian Ocean, southwest of Christmas Island and approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka....

. The second chapter similarly describes a typical barrier reef then compares it to others, and the third chapter gives a similar description of what Darwin called fringing or shore reefs. Having described the principal kinds of reef in detail, his finding was that the actual surface of the reef did not differ much. An atoll differs from an encircling barrier reef only in lacking the central island, and a barrier reef differs from a fringing reef only in its distance from the land and in enclosing a lagoon.

The fourth chapter on the distribution and growth of coral reefs examines the conditions in which they flourish, their rate of growth and the depths at which the reef building polyp

Polyp

A polyp in zoology is one of two forms found in the phylum Cnidaria, the other being the medusa. Polyps are approximately cylindrical in shape and elongated at the axis of the body...

s can live, showing that they can only flourish at a very limited depth. In the fifth chapter he sets out his theory as a unified explanation for the findings of the previous chapters, overcoming the difficulties of treating the various kinds of reef as separate and the problem of reliance on the improbable assumption that underwater mountains just happened to be at the exact depth below sea level, by showing how barrier reefs and then atolls form as the land subsides, and fringing reefs are found along with evidence that the land is being elevated. This chapter ends with a summary of his theory illustrated with two woodcuts each showing two different stages of reef formation in relation to sea level.

In the sixth chapter he examines the geographical distribution of types of reef and its geological implications, using the large coloured map of the world to show vast areas of atolls and barrier reefs where the ocean bed was subsiding with no active volcanos, and vast areas with fringing reefs and volcanic outbursts where the land was rising. This chapter ends with a recapitulation which summarises the findings of each chapter and concludes by describing the global image as "a magnificent and harmonious picture of the movements, which the crust of the earth has within a late period undergone". A large appendix gives a detailed and exhaustive description of all the information he had been able to obtain on the reefs of the world.

This logical structure can be seen as a prototype for the organisation of On the Origin of Species, presenting the detail of various aspects of the problem, then setting out a theory explaining the phenomena, followed by a demonstration of the wider explanatory power of the theory. Unlike the Origin which was hurriedly put together as an abstract

Abstract (summary)

An abstract is a brief summary of a research article, thesis, review, conference proceeding or any in-depth analysis of a particular subject or discipline, and is often used to help the reader quickly ascertain the paper's purpose. When used, an abstract always appears at the beginning of a...

of his planned "big book", Coral Reefs is fully supported by citations and material gathered together in the Appendix. Coral Reefs is arguably the first volume of Darwin's huge treatise on his philosophy of nature, like his succeeding works showing how slow gradual change can account for the history of life. In presenting types of reef as an evolutionary series it demonstrated a rigorous methodology for historical sciences, interpreting patterns visible in the present as the results of history. In one passage he presents a particularly Malthusian

Malthusianism

Malthusianism refers primarily to ideas derived from the political/economic thought of Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus, as laid out initially in his 1798 writings, An Essay on the Principle of Population, which describes how unchecked population growth is exponential while the growth of the food...

view of a struggle for survival – "In an old-standing reef, the corals, which are so different in kind on different parts of it, are probably all adapted to the stations they occupy, and hold their places, like other organic beings, by a struggle one with another, and with external nature; hence we may infer that their growth would generally be slow, except under peculiarly favourable circumstances."

Reception

Having successfully completed and published the other books on the geology and zoology of the voyage, Darwin spent eight years on a major study of barnacleBarnacle

A barnacle is a type of arthropod belonging to infraclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea, and is hence related to crabs and lobsters. Barnacles are exclusively marine, and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters, typically in erosive settings. They are sessile suspension feeders, and have...

s. Two volumes on Lepadidae (goose barnacles) were published in 1851. While he was still working on two volumes on the remaining barnacles, Darwin learnt to his delight in 1853 that the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

had awarded him the Royal Medal for Natural Science. Joseph Dalton Hooker

Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker OM, GCSI, CB, MD, FRS was one of the greatest British botanists and explorers of the 19th century. Hooker was a founder of geographical botany, and Charles Darwin's closest friend...

wrote telling him that "Pordock proposed you for the Coral Islands & Lepadidae, Bell followed seconding on the Lepadidae alone, & then followed such a shout of paeans for the Barnacles that you would have [smiled] to hear."

Darwin's findings and modern views

Darwin's interest on the biology of reef organisms was focussed on aspects related to his geological idea of subsidence; in particular, he was looking for confirmation that the reef building organisms could only live at shallow depths. FitzRoy's soundingsSounding line

A sounding line or lead line is a length of thin rope with a plummet, generally of lead, at its end. Regardless of the actual composition of the plummet, it is still called a "lead."...

at the Keeling Islands gave a depth limit for live coral of about 20 fathoms (37 m), and taking into account numerous observations by others, Darwin worked with a probable limit of 30 fathoms (55 m). Modern findings suggest a limit of around 100 m, still a small fraction of the depth of the ocean floor at 3000–5000 m. Darwin recognised the importance of red algae

Red algae

The red algae are one of the oldest groups of eukaryotic algae, and also one of the largest, with about 5,000–6,000 species of mostly multicellular, marine algae, including many notable seaweeds...

, and he reviewed other organisms that could have helped to build the reefs. He thought they lived at similarly shallow depths, but banks formed at greater depths were found in the 1880s. Darwin reviewed the distribution of different species of coral across a reef. He thought that the seaward reefs most exposed to wind and waves were formed by massive corals and red algae; this would be the most active area of reef growth and so would cause a tendency for reefs to grow outwards once they reach sea level. He believed that higher temperatures and the calmer water of the lagoons favoured the greatest coral diversity. These ecological

Ecology

Ecology is the scientific study of the relations that living organisms have with respect to each other and their natural environment. Variables of interest to ecologists include the composition, distribution, amount , number, and changing states of organisms within and among ecosystems...

ideas are still current, and research on the details continues.

Parrotfish

Parrotfishes are a group of fishes that traditionally had been considered a family , but now often are considered a subfamily of the wrasses. They are found in relatively shallow tropical and subtropical oceans throughout the world, but with the largest species richness in the Indo-Pacific...

browsed on the living coral, he dissected specimens to find finely ground coral in their intestines. He concluded that such fish, and coral eating invertebrates such as Holothuroidea, could account for the banks of fine grained mud he found at the Keeling Islands; it showed also "that there are living checks to the growth of coral-reefs, and that the almost universal law of 'consume and be consumed,' holds good even with the polypifers forming those massive bulwarks, which are able to withstand the force of the open ocean."

His observations on the part played by organisms in the formation of the various features of reefs anticipated modern studies. To establish the thickness of coral barrier reefs, he relied on the old nautical rule of thumb to project the slope of the land to that below sea level, and then applied his idea that the coral reef would slope much more steeply than the underlying land. He was fortunate to guess that the maximum depth of coral would be around 5,000 ft (1,500 m), as the first test bores conducted by the United States Atomic Energy Commission

United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by Congress to foster and control the peace time development of atomic science and technology. President Harry S...

on Enewetak

Enewetak

Enewetak Atoll is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean, and forms a legislative district of the Ralik Chain of the Marshall Islands. Its land area totals less than , surrounding a deep central lagoon, in circumference...

Atoll in 1952 drilled down through 4610 ft (1,405 m) of coral before reaching the volcanic foundations. In Darwin's time no comparable thickness of fossil coral had been found on the continents, and when this was raised as a criticism of his theory neither he nor Lyell could find a satisfactory explanation. It is now thought that fossil reefs are usually broken up by tectonic movements

Tectonics

Tectonics is a field of study within geology concerned generally with the structures within the lithosphere of the Earth and particularly with the forces and movements that have operated in a region to create these structures.Tectonics is concerned with the orogenies and tectonic development of...

, but at least two continental fossil reef complexes have been discovered to be about 3,000 ft (1,000 m) thick. While these findings have confirmed his argument that the islands were subsiding, his other attempts to show evidence of subsidence have been superseded by the discovery that glacial effects can cause changes in sea level.

In Darwin's global hypothesis, vast areas where the seabed was being elevated were marked by fringing reefs, sometimes around active volcanoes, and similarly huge areas where the ocean floor was subsiding were indicated by barrier reefs or atolls based on inactive volcanoes. These views received general support from deep sea drilling results in the 1980s. His idea that rising land would be balanced by subsidence in ocean areas has been superseded by modern plate tectonics

Plate tectonics

Plate tectonics is a scientific theory that describes the large scale motions of Earth's lithosphere...

, which he did not anticipate.