Save Our Children

Encyclopedia

Save Our Children, Inc. was a political coalition formed in 1977 in Miami, Florida

, U.S. to overturn a recently legislated county ordinance that banned discrimination in areas of housing, employment, and public accommodation based on sexual orientation

. The coalition was publicly headed by celebrity singer Anita Bryant

, who claimed the ordinance discriminated against her right to teach her children biblical morality. It was a well-organized campaign that initiated a bitter political fight between unprepared gay activists and highly motivated Christian fundamentalists. When the repeal of the ordinance went to a vote, it attracted the largest response of any special election in Dade County

's history, passing by 70%.The gay rights ordinance re-enacted by Dade County commissioners in 1998; it survived a repeal attempt by the Christian Coalition in 2003. (Days Without Sunshine: Anita Bryant's Anti-Gay Crusade, Stonewall Library and Archives. Retrieved on October 23, 2010.)

Save Our Children was the first organized opposition to the gay rights movement

, whose beginnings were traced to the Stonewall riots

in 1969. The defeat of the ordinance encouraged groups in other cities to attempt to overturn similar laws. In the next year voters in St. Paul, Minnesota, Wichita, Kansas

, and Eugene, Oregon

overturned ordinances in those cities, sharing many of the same campaign strategies that were used in Miami. Save Our Children was also involved in Seattle, Washington

, where they were unsuccessful, and heavily influenced Proposition 6—a proposed state law in California

that would have made the firing of openly

gay

public school employees mandatory—that was rejected by California voters in 1978.

Historians have since connected the overwhelming success of Save Our Children with the organization of conservative Christian participation in political processes. Although forceful Christian involvement had not taken a widespread role in politics in the United States since 1925, within two years the Reverend Jerry Falwell

developed a coalition of conservative religious groups named the Moral Majority

that influenced the Republican Party

to incorporate a social agenda in national politics. Homosexuality, the Equal Rights Amendment

(ERA), abortion

, and pornography

were among the issues most central to the Moral Majority's priorities until it folded in 1989. For many gay men and lesbian

s, the surprise at the outcome of all the campaigns in 1977 and 1978 instilled a new determination and consolidated activism and communities in many cities where the gay community had not been politically active.

proposed the bill on December 7, 1976 at the request of a gay lobbying organization, named the Dade County Coalition for the Humanistic Rights of Gays, that was less than a year old. The group was headed by three gay activists: Jack Campbell, an owner of 40 gay bathhouse

s across the United States, political and gay activist Bob Basker

, and Bob Kunst, a local publicist and enthusiast of the Human Potential Movement

and proponent of sexual liberation.

of the Florida Legislature actively sought to root out homosexuals in state employment and in public universities across the state, publishing the inflammatory "Purple Pamphlet," which portrayed all homosexuals as predators and a dire threat to the children of Florida. In the 1960s The Miami Herald

ran several stories implying the life of area homosexuals as synonymous with pimp

s and child molesters, and the local NBC

television station aired a documentary entitled "The Homosexual" in 1966 warning viewers that young boys were in danger from predatory men.

The public image of homosexuals changed with liberalized social attitudes of the late 1960s. In 1969, the Stonewall riots

occurred in New York City

, marking the start of the gay rights movement. Though gay life in Miami was intensely closeted, and bars were subject to frequent raids, Christ Metropolitan Community Church

—a congregation for gay and lesbian Christians in Miami—was founded in 1970 as a religious outlet, attracting hundreds of parishioners. The 1972 Democratic National Convention

was held in Miami, featuring, for the first time, a public speech about the rights of gay men and lesbians by openly

gay San Francisco political activist Jim Foster

. Jack Campbell opened the Miami branch of Club Baths

in 1974. When it was raided, he made sure that all charges against those arrested were dropped, filed a lawsuit against the Miami Police Department

prohibiting further harassment, and received a formal apology from the police. Even the depiction of gay men and lesbians in the local newspaper had changed to that of a silent, oppressed minority. By 1977, Miami was one of nearly 40 cities in the U.S. that had passed ordinances outlawing discrimination against gay men and lesbians.

, who was a 36-year-old singer celebrity. Bryant began her career as a local child star on a television show in Oklahoma City

and on Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts

. Her young life was marked by frequent moves; her parents divorced each other twice, and she often lived in poverty conditions, but she became a born again Christian at eight years old, and counted her faith and her participation at church as the stabilizing influences in her life. As a child, she asked God to make her a star. She was, by her own admission, remarkably driven and ambitious. In her older teens she became a beauty pageant contestant, winning Miss Oklahoma

and second runner-up as Miss America

. In 1960, she married a Miami disc jockey

named Bob Green and became a professional singer, finding some success with three gold records featuring popular, patriotic, and Gospel standards. She performed with the Bob Hope Christmas tour, entertaining troops serving overseas, and sang at President Lyndon Johnson's funeral in 1973. Since 1969 she had been employed regionally by the Florida Citrus Commission endorsing Florida orange juice in television commercials. She also advertised for Coca-Cola

, Tupperware

, Kraft Foods

and Holiday Inn

s. Bryant's talent agent was married to Ruth Shack; Bryant had contributed $1,000 to her campaign.

Initially Bryant kept her concerns low-key, despite her pastor's pleadings to become involved. She wrote a letter to the county commission and called Ruth Shack, expressing her concerns. Her most significant objection to the ordinance was that it would allow homosexuals to work in parochial school

s; all four of Bryant's children attended a local private Christian school. She admitted she was largely ignorant of any specific dangers homosexuals presented, but when she was sent graphic images of homosexual acts, and shown photos of child pornography

by a local police sergeant visiting her church, she was horrified.Bryant gave a candid interview to Playboy magazine, printed in May 1978 where she admitted that she knew of homosexuals in show business but was unaware of the "nitty gritty" of their sexual behavior until her husband described them to her. She professed being most astonished that they ate each others' sperm, and equated the act with the immorality of destroying the Seed of Life. Bryant also claimed never to have heard of Alfred Kinsey

's study that estimated one out of five males had had some sexual contact with another male; or any information about homosexual behavior in animals. The interviewer, Ken Kelley, wrote a companion piece to the interview, stating that she was impossible to "pigeonhole" due to her deliberate enigmatic persona: "She is a confection of contradictions: pristine nun and gamy tease. Old pro who's paid her dues and wide-eyed waif who's still seeking the jackpot. Guilt-wracked sinner who's terrified of hell and perfervid white knight who's determined to lead mankind on a forced march into paradise. Independent spirit, cowering wife. Chaplain one minute, warden the next. She is a demonstrably intelligent woman who stays steadfastly ignorant." For months Bryant called Kelley just to talk, even though she knew she would not be portrayed favorably in the magazine. Kelley and a few others concluded that Bryant was simply very lonely. (Young, p. 39.) Bryant credited her inspiration later to her 9-year-old daughter suggesting God could assist with her cause; then she decided to take a more public role.

At the time of the commission's vote in January, the boardroom was crowded with people who held some kind of interest in the issue. Busloads of churchgoers arrived from as far away as Homestead

and picketed outside; there was no corresponding organized show of support for the ordinance. Inside the boardroom, supporters and opposers took the entire allotted time to speak. Bryant reflected most of those opposing the law, telling the Dade County Commission, "The ordinance condones immorality and discriminates against my children's rights to grow up in a healthy, decent community". The few members of the Dade County Coalition for the Humanistic Rights of Gays who were present were stunned, as was Ruth Shack, at the number and force of the hundreds of protesters who filled the commission room, and held placards and pickets outside. But the ordinance passed by a 5-3 vote.

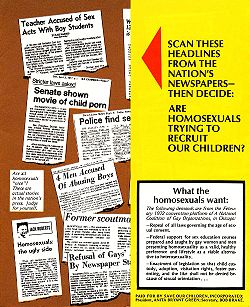

After the ordinance passed, over thirty conservative political professionals and ministers from various faiths met in Bryant and Green's home to discuss a plan to raise publicity and attempt to get at least 10,000 signatures on a petition to force the issue to be decided by a county voter referendum. They approved the name "Save Our Children, Inc.", and voted Bryant their president, Bob Green treasurer and a man named Robert Brake—a devout Catholic with a record of civil rights participation, but increasingly concerned with the liberalization of Miami city politics—its secretary. With the assistance of a Republican-affiliated advertising executive named Mike Thompson, the coalition eschewed subtlety. They held a press conference where Bryant held a pamphlet about homosexuality she claimed was being distributed at area high schools (a statement she later retracted), and said Dade County homosexuals "are trying to recruit our children into homosexuality". Far exceeding the required number of signatures, the coalition delivered more than 64,000 signatures within six weeks demanding a referendum vote, which the commission set for June 7, 1977.

After the ordinance passed, over thirty conservative political professionals and ministers from various faiths met in Bryant and Green's home to discuss a plan to raise publicity and attempt to get at least 10,000 signatures on a petition to force the issue to be decided by a county voter referendum. They approved the name "Save Our Children, Inc.", and voted Bryant their president, Bob Green treasurer and a man named Robert Brake—a devout Catholic with a record of civil rights participation, but increasingly concerned with the liberalization of Miami city politics—its secretary. With the assistance of a Republican-affiliated advertising executive named Mike Thompson, the coalition eschewed subtlety. They held a press conference where Bryant held a pamphlet about homosexuality she claimed was being distributed at area high schools (a statement she later retracted), and said Dade County homosexuals "are trying to recruit our children into homosexuality". Far exceeding the required number of signatures, the coalition delivered more than 64,000 signatures within six weeks demanding a referendum vote, which the commission set for June 7, 1977.

The Save Our Children campaign produced a local television commercial showing the "wholesome entertainment" of the Orange Bowl Parade (which Bryant hosted), contrasting that with highly sexualized images of the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade

, including men in leather harnesses kissing each other, dancing drag queen

s, and topless women. The commercial's announcer accused Miami's gay community of trying to turn Miami into the "hotbed of homosexuality" that San Francisco had become. Full-page newspaper ads were run in The Miami Herald

, showing collections of headlines announcing teachers having sex with their students, children in prostitution rings, and homosexuals involved with youth organizations, followed by the question "Are all homosexuals nice? ... There is no 'human right' to corrupt our children."

Though Miami was not the first community to overturn a sexual orientation civil rights law, the Save Our Children campaign became a national political cause. Bryant became the focus of the campaign, as noted by her husband that she was the "first person with a name" to become vocal about homosexuality; gay activists agreed, saying that other cities "haven't had a major personality come out and create a witch hunt. People have lost sight of the issue; the controversy has become personality oriented". In opposition to her, Bob Kunst, who had experience as the publicist of the local municipal soccer team, the Miami Toros

, was a familiar name to the local press. Kunst, however, remained determined to act as an individual, often taking opportunities to give his views to the press that were not condoned by the Dade County Coalition on the Humanistic Rights of Gays. He took the view that it was the sexually enlightened stance to pass the ordinance, and those who opposed it were uptight, including, near the end of the campaign, Florida Governor Reubin Askew

. He gave interviews addressing sexual liberation for gay and straight people, in which he freely spoke about oral

and anal sex

.

and Jim Foster

from San Francisco, both of whom were gay. Foster and Geto faced battles not only with the Save Our Children campaign, but the disjointed and often closeted

gay community in Miami. When organizations outside of Florida promoted boycott

ing Florida orange juice, Jack Campbell disagreed, worried that an economic backlash in the state would work against local gay men and lesbians. Ruth Shack saw the issue simply, as one of civil rights; Geto and Foster agreed. Bob Kunst soon broke away from the campaign to promote the orange juice boycott, and his views were often printed in the newspapers to Geto's alarm.

Save Our Children also received help from outside the area. North Carolina

senator Jesse Helms

offered his staff and funding from the Congressional Club

, and wrote in his column that he was proud of Bryant: "I have pledged my full support to her ... She is fighting for decency and morality in America—and that makes her, in my book, an all-American lady". Pastor Jerry Falwell

from Lynchburg, Virginia

lent his support during visits and with the appearance of B. Larry Coy, who served as a marriage counselor to Bryant and Green. Coy and Green took over management of Bryant's ministries.Bryant later accused Coy of working with Green to take over her ministries and control her completely, saying they formed a "devil's triangle" to form a "satanically self-righteous conspiracy" to deprive her of all control, including that of her own conscience. Bryant tried to fire him, to no avail. (Jahr, Cliff [December 1980]. "Anita Bryant's Startling Reversal", Ladies Home Journal, p. 62–68)

Two months before the referendum vote, Bob Green, speaking for Bryant, vowed to lead her cause in all cities in the United States that protected sexual orientation from discrimination, saying that gay activists waged a "disguised attack on God", and Bryant would "lead such a crusade to stop it as this country has not seen before". As information was distributed against the referendum, as much literature was spread expressing local dissatisfaction with Bryant. T-shirts and campaign buttons were produced, showing "Anita Bryant Sucks Oranges" and "Squeeze a fruit for Anita".

Communications professor Fred Fejes, mainstream newspapers and magazines in the 1970s were hesitant to cover the issues of homosexuality or Christian fundamentalism in detail. Media prided themselves on objective reporting without Biblical judgment and at the same time, reporting was a homophobic profession that suppressed openly

gay reporters and rarely addressed topics involving homosexuality. As a result, during the 1970s fundamentalist Christians began to develop broadcasting over radio and television in the forms of The 700 Club

run by Pat Robertson

, PTL Club hosted by Jim

and Tammy Faye Bakker, and Jerry Falwell

's Old Time Gospel Hour. These shows originated as praise and worship-oriented, but slowly incorporated political themes interspersed with messages of Christian faith. Bryant's appearances on the 700 Club and the PTL Club netted the Save Our Children campaign $25,000 in donations, and assured her a position as a national spokesperson for traditional Christian values. However, when addressing a secular audience, Bryant was not as successful. During debates with Kunst and Shack she rarely made points that went beyond Bible quotes, and prayed when pressed to provide statistics on homosexuals as child molesters. At another appearance, she broke into "The Battle Hymn of the Republic

" to take up time after she had read a pre-written statement. As California was experiencing a drought, Bryant connected it to their tolerance of liberals and homosexuals, and suggested that other morality laws should be enforced, such as those against adultery

and cohabitation out of wedlock. Mike Thompson and Robert Brake soon restricted her to primarily religious shows.

At the same time, the gay community promoted their causes using specialty magazines and newspapers. The Advocate

, a bi-weekly magazine, dedicated every issue starting in April 1977 to raising awareness of the battle taking place in Miami. It was run by David Goodstein, a friend of Jim Foster's who had worked with Foster to create the first gay Democratic club in the U.S. in the Alice B. Toklas Memorial Democratic Club. Goodstein warned that the fight would not end in Miami if the gay community lost, as did the local gay-focus newspapers of Boston's Gay Community News

and San Francisco's Bay Area Reporter

. Goodstein also suggested Bryant's primary motivation in her actions was furthering her career, or the beginning of "an organized conspiracy to turn (gays) into America's scapegoats".

Bryant's star power and her extreme views were highlighted in national news stories. Mainstream news outlets such as The New York Times

, Associated Press

and Washington Post reported weekly updates on campaign progress, with smaller local newspapers across the country weighing in their editorial opinions on which side should prevail. Bryant appeared on Good Morning America

andThe Phil Donahue Show

. Her tone and accusations united gay men and lesbians in cities all over the U.S. In the weeks before the vote, almost $55,000 was raised outside of Florida to oppose Save Our Children. Foreshadowing the effectiveness of the Save Our Children campaign, on April 13, 1977, the Florida Legislature

voted not to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment

(ERA), to the astonishment of those anticipating the vote. The connection between the ERA and ordinance 77-4 was obvious to many. Florida Senator Dempsey Barren vocally opposed passing the ERA, fearing it would legalize same-sex marriage

s, force people to use unisex bathrooms, and that it would harm laws meant to protect families. National Organization for Women

founder and ERA proponent Betty Friedan

expressed her disdain, saying "suddenly you have this red herring in Anita Bryant. Suddenly you have this wave of anti-gay hysteria and then that was preempting the air waves behind the scenes".

Washington D.C. mayor Marion Barry

, Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley

, President Jimmy Carter

all expressed support for the ordinance. In The Miami Herald, 51 members of Dutch Parliament, ministers, and civil rights advocates from the Netherlands

ran a full-page ad stating "We, from the land of Anne Frank

, know where prejudices and discrimination can lead to", advising the voters of Miami-Dade to uphold the ordinance to protect the rights of homosexuals. California Assemblyman

Willie Brown

and San Francisco sheriff Richard Hongisto campaigned respectively for Miami's black community and law enforcement. Hongisto returned to California saying that Save Our Children made an issue of the existence of San Francisco when Thompson referred to the city as "a cesspool of perversion gone rampant" and Bob Green expressed doubt that saving San Francisco was possible. Reverend Jerry Falwell spoke at a rally as the vote neared, telling the audience, "I want to tell you we are dealing with a vile and vicious and vulgar gang. They'd kill you as quick as look at you."

served as an officer of the Save Our Children coalition.

Miami's Cuban community came together as never before for the campaign, taking the opportunity to register thousands of voters who had never taken part in politics in the city. Bryant actively campaigned to the Cuban community, telling them at a rally, "You came here to get away from one sin ... and it breaks my heart that if Miami becomes another Sodom and Gomorrah

you may have to leave here, too." A Cuban social worker suggested the cause was representative of an older generation of Cuban emigres, worried that their children were being lost in the depravity of Miami. Miami's archbishop wrote a letter against the gay rights ordinance, and ordered it to be read aloud in all Catholic churches.

The response from Miami's black community was more conflicted. The Miami Times, a widely respected black newspaper, called Bryant's tactics "pure bullshit" and urged local blacks not to vote for anything that would discriminate against anyone. However, black audiences reacted angrily during an appearance featuring Bryant and another with Kunst and white ministers from the Metropolitan Community Church

.

Due to the intensely closeted nature of Miami's gay community at that time, many voters who were not swayed by Bryant's rhetoric were persuaded instead by her campaign's point that the law was unnecessary; they were unable to see the problem of discrimination. Unlike blacks or Cubans, gay men and lesbians were able to find jobs, although they faced dismissal upon their supervisors learning of their sexual orientation. In order to see a complaint through, they would have to remain out, and many lived in constant fear of exposure. Since the advent of second wave feminism earlier in the decade, many lesbians in the U.S. were unable to see themselves as part of the same community with gay men. Accusations from Save Our Children were almost all directed at the behavior of men. As a result, much of the response by gay men was angry and many lesbians took issue with the misogynistic tone gay men used. However, with Bryant representing a common adversary, for the first time in years, gay men and lesbians united to work together on the campaign.

said that the result was "all the evidence anyone could need of the extent and virulence of prejudice against lesbians and gay men in our society".

—who had introduced the first gay civil rights bill in U.S. Congress—was awoken at 2 am by people in the street chanting her name. "It was hard not to feel sad for this crowd", Abzug said of the several hundred people below her window. She was optimistic, telling them the defeat would develop a maturity and determination in gay activism. About the same time that evening, about 3,000 gay men and lesbians spontaneously gathered in what had become the largest gay neighborhood in the United States—Castro Street in San Francisco—furious at the loss in Dade County. The crowd marched around the Castro District, chanting "We Are Your Children!" pulling people out of gay bars to cheers. Local gay activist and future supervisor Harvey Milk

led marchers through a 5 miles (8 km) course through the city, careful not to stop for too long lest rioting began. He addressed the crowd with a bullhorn: "This is the power of the gay community. Anita's going to create a national gay force". The day after the vote, Jean O'Leary and NGTF co-director Bruce Voeller

said Bryant was doing "an enormous favor" for the gay community by focusing national media attention on discrimination against them.

Several weeks later at the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade, 250,000 people attended, becoming the largest attendance at any gay event in U.S. history to that point. The largest group of the parade held large placards of Joseph Stalin

, Adolf Hitler

, Idi Amin

, a burning cross

, and Anita Bryant. Other cities also saw greater participation in Gay Pride events. People marching in New York's Gay Pride observance shouted "No more Miamis". Thousands of people attended events in Seattle, Boston

, Cleveland, and Atlanta. Kansas City

observed its first Gay Pride demonstration with 30 people. The largest gay newspaper in Australia

used the Dade County vote as a warning advising gay men and lesbians there to "Get off Your Butts". More than 300 people held a vigil at the American embassy in the Netherlands, accusing the U.S. government of failing to protect their citizens' human rights. Four thousand marchers in Spain

were dispersed by rubber bullets. Gay activists in Paris

and London

also warned that similar challenges could occur in their cities.

In The New York Times

, conservative columnist William Safire

wrote that Miami's gay activists had been justifiably defeated: "In the eyes of the vast majority, homosexuality is an abnormality, a mental illness, even—to use an old-fashioned word—a sin. Homosexuality is not the 'alternative lifestyle' the gay activists profess; it may be tolerable, even acceptable—but not approvable." Safire, however, tempered the column (titled "Now Ease Up, Anita") cautioning against Bryant's promised nationwide crusade designed to lead to further repeal of homosexuals' "legitimate civil rights".

A Connecticut

-based charity for unprivileged children named Save the Children

filed an injunction in July 1977 against the Miami coalition to prevent them from using the name, and Bryant from using it as a title for a book she was writing; Save the Children lost donations due to the confusion between the names. Briefly, the coalition was known as "Protect the Children" and focused completely on moral legislation against militant homosexuality, pornography, and images of sex and violence on television. It was renamed to Anita Bryant Ministries.

blamed Bryant's rhetoric for his death and 200,000 San Francisco residents joined a memorial demonstration for him. Mrs. Hillsborough brought a $5 million civil suit against Anita Bryant claiming Hillsborough's attackers said "Here's one for Anita". She said, "I didn't think much about Anita Bryant's campaign at first. Now that my son's murder has happened, I think about the Bryant campaign a lot. Anyone who wants to carry on this kind of thing must be sick. My son's blood is on her hands." Bryant, Green, Mike Thompson and Save Our Children were dismissed from the suit in November 1977.

Several suicides were connected to the campaign, including a Cuban gay activist in Miami named Ovidio "Herbie" Ramos, who was stunned at the vehemence against homosexuals. He and several other Cuban gay activists participated in a radio call-in show to hear people say homosexuals should be deported, forced into concentration camps, or executed. Ramos shot himself several nights following the show, after telling a friend, "I didn't know they hated us so much". Another Cuban gay activist named Manolo Gomez was fired from his job and severely beaten, after which he decided to leave Miami. Gay activists in New Orleans tried to discourage Bryant's performance with the New Orleans Pops orchestra by connecting local suicides to her campaign. Bryant responded to violence saying, "It made me sad and shocked me that anyone would think I had anything to do with it, but my conscience is clear. I can't be responsible for how people react to what happened in Dade County. My stand was not taken out of homophobia, but of love for them."

canceled negotiations for a television variety show. She was replaced after ten years of hosting the Orange Bowl Parade by Rita Moreno

, who was older and who had recently performed in a gay-themed film, The Ritz. Bryant and Green held a press conference and claimed Bryant was being blacklist

ed; a national conspiracy was underway by the nation's homosexuals to deprive her of her livelihood. Time

magazine called the charge "unlikely", and network executives denied gay pressure was behind their decision. Bryant's claim of being blacklisted brought a tide of condemnation against the perceived pressure by gay organizations. Three major newspapers supported Bryant's right to free speech. Years later, she admitted that some of the statements made about her cancellations were exaggerated for effect, but that the tactic worked against her, as more organizations and companies canceled her performances.

Bryant became the butt of jokes on television shows and film, even by former colleague Bob Hope

. Everywhere she went in the days after the vote she was met with noisy protests: Norfolk, Virginia

—where demonstrators interrupted her presentation so forcefully she began crying—Chicago

, and dozens of other cities. The Ku Klux Klan

appeared at one of Bryant's appearances in Huntington, West Virginia

claiming they were there to protect her. She attracted the largest gay demonstration in Canadian history when she appeared at a Toronto

religious performance. Though she performed and spoke only at revivals and other religious shows, audiences were often less than half the expected number, and many would leave when she came on stage. In Houston Bryant was invited to perform for the Texas State Bar Association

two weeks after the Dade County vote. With no cohesive political community, a few gay organizers invited people to protest her appearance at the Hyatt Regency. An organizer estimated for police that 500 people might participate, but guessed because no gay community had responded to a cause before; police prepared for that number. However, thousands of people swarmed around the hotel chanting loudly enough to drown Bryant's performance; a conservative estimate of the participants' numbers was 2,000. The audience inside could not hear Bryant, and at one point attorneys working with the American Civil Liberties Union

walked out and joined the protesters. One of the organizers said that he had never seen so many gay people in one place before, and then made a speech thanking Bryant: "If God in his infinite wisdom had not created Anita Bryant, we would have had to invent her". He claimed the protest had the same result in Houston as the Stonewall riots

.

The Florida Citrus Commission reiterated its commitment to Bryant by stating that it "wholeheartedly support(ed)" her right to free speech, praising her "courageous leadership on a moral issue that it is tearing up religious and other organizations which have become involved". The commission received thousands of letters both supporting Bryant's stance and condemning the commission; at one point the U.S. Postal Service installed bomb detection equipment for the mail collected for delivery to the Florida Citrus Commission. The publicity director for the Florida Department of Citrus told a reporter from the Associated Press, "The whole Anita thing is a mess. No matter what we decide, we're only going to lose. I wish she would just resign." Although in 1979 the commission extended their $100,000 annual contract with Bryant, they did not renew it in 1980.

, and Palm Beach, Florida

, and Austin, Texas

, all rejected ordinances to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development overturned its own rules they had set earlier in the year to allow unmarried and same-sex couples federally financed housing. Newsweek

reported that a county government employee who had worked in her position for 15 years had been fired. An openly gay aide to future U.S. senator Paula Hawkins

had also been dismissed. Despite the success of the Dade County campaign, activists worked quietly in liberal towns of Aspen, Colorado

, Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, Iowa City, Iowa

, Wichita, Kansas

, and the very liberal Eugene, Oregon

to pass gay rights ordinances.

was defeated. The loss was due in large part to the efforts of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, and once more, caught gay activists completely by surprise. The Twin Cities' gay community was much more active than Miami's; both Minneapolis and St. Paul had passed gay rights laws three years before. State senator Allan Spear

—the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in the U.S.—served in St. Paul. Spear called it a "victory for bigots" on the senate floor, then went into his office and cried. A group of guerrilla activists struck the archbishop a week after the vote by throwing a chocolate cream pie at him as he spoke to receive the National Brotherhood Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews.

Following the pie attack on the archbishop, two of Allan Spear's colleagues invited Anita Bryant to come to St. Paul to overturn their three-year-old gay rights ordinance, and announced Save Our Children would be opening a branch there. Local activists did not think much of their chances; a local gay political group invited gays and lesbians in Miami to live in Minneapolis—St. Paul. In an act representing Bryant's diminished national public profile, in October 1977 Bryant and her husband were in Des Moines, Iowa

Following the pie attack on the archbishop, two of Allan Spear's colleagues invited Anita Bryant to come to St. Paul to overturn their three-year-old gay rights ordinance, and announced Save Our Children would be opening a branch there. Local activists did not think much of their chances; a local gay political group invited gays and lesbians in Miami to live in Minneapolis—St. Paul. In an act representing Bryant's diminished national public profile, in October 1977 Bryant and her husband were in Des Moines, Iowa

, discussing an upcoming concert at a press conference when Thom Higgins, an activist affiliated with organizers in Minneapolis, walked up to her in front of cameras and mashed a strawberry rhubarb pie

in her face. Bryant was stunned and bowed her head as she and Green held hands and prayed for Higgins. Though she quickly quipped "At least it's a fruit pie," she was sobbing within moments. An image of her covered with the pastry appeared on the front page of The New York Times the next day.

In December 1977, however, a petition drive was organized by Temple Baptist Church to put St. Paul's ordinance to a city-wide vote. Volunteers endured below freezing temperatures to collect more than 7,000 signatures; their leader, Richard Angwin, pastor of Temple Baptist reasoned, "I don't want to live in a community that gives respect to homosexuals." Angwin used the same strategy as the Miami campaign, tapping the resources of Bryant, Green, and their pastor in Miami. Jerry Falwell held a rally where Bryant was advertised to appear, but Green replaced her at the last minute. At the rally Angwin told the audience "Homosexuality is a murderous, horrendous, twisted act. It is a sin and a powerful, addictive lust."

Gay activists in St. Paul also borrowed from Miami, taking Jack Campbell's donor list and some strategies. However, similar to Miami, many gays and lesbians in St. Paul were hesitant to come out and could not make a solid case for discrimination; most of the activists were from Minneapolis. Gay activists were also split in strategy, much like in Miami. A more mainstream group named the St. Paul Citizens for Human Rights (SPCHR) opted to treat the issue as one of civil and human rights. A more radical group of gays named the Target City Coalition—those who had arranged the pieing of the archbishop—saw the issue as one of sexual liberation and grabbed the most media attention by highlighting some of the more flamboyant parts of the gay community. The Advocate wrote that they were "the most stoned-out, off-the-wall, bona-fide crackpots yet to appear in the gay rights cause." The Target City Coalition invited Bob Kunst to St. Paul, where he spoke of sexual liberation and the need to reach out to gay youth. Allan Spear, supportive ministers, and other members of SPCHR went on local television to debate the civil rights issue. Reverend Angwin stumped Spear and his cohorts by showing them an advertisement placed by the Target City Coalition in a local gay paper appealing to gay teenagers, that offered them "free prostate rubs."

St. Paul's special election day was April 25, 1978. Again, more than the usual number of voters appeared for a special election, who again, overturned the city's gay rights ordinance by more than two to one.

spent their summers there. A housewife named Lynne Greene rejected the Biblical rhetoric offered by Bryant and instead argued that gays already had the protection they needed under the law; further legislation was unnecessary. Since homosexuality was a chosen lifestyle, they reasoned, homosexuals were not a minority and needed no protection. Acknowledging the rights of gays would lead the law to give them rights to marry, and adopt children. Though gay rights advocates worked differently in Eugene, registering many new voters and seeing lesbians significantly working the campaign for the first time, their opposition worked steadily by canvassing neighborhoods. Most of their volunteers were members of conservative churches, and the message was similar to recent campaigns: "Keep it straight. Our children come first," but the Eugene campaign lacked the sensational aspect as those in Miami and St. Paul.

Once more in nearly a two to one margin, the gay rights ordinance was defeated in Eugene. A poll taken after the vote showed that liberal voters who were not gay simply declined to show up and vote, and those who opposed the ordinance were much more motivated.

with newspaper clippings connecting gays to child molestation. They raised approximately $50,000 and used the network of churches, local media, and a highly organized grassroots voter registration and mobilization drive. Campaign literature focused on the aspect gay visibility, and the dangers of gays as role models for children: "There is a real danger that homosexual teachers, social workers or counselors, simply by public acknowledgment of their lifestyles, can encourage sexual deviation in children." In comparison, the very small and closeted gay community raised only $6,000; the National Gay Task Force was so pessimistic they offered no assistance at all. Bryant attended a rally stating the law would give homosexuals "special rights ... and next you will have thieves, prostitutes and people who have relations with St. Bernards asking for the same rights". The Wichita ordinance was defeated by a five to one margin. Ron Adrian was ecstatic.

Estes' organization attracted a $3,000 donation from Anita Bryant, and her pastor traveled to Seattle to give advice on Estes' campaign. However, where Estes planned to use the network of conservative churches in the city, many members were discouraged from working with him because he was a Mormon. The tone of the advertising for the campaign was more dire than in Miami; ads claimed homosexuals were responsible for half the murders and suicides in major cities and half the cases of syphilis

. Perhaps the most significant factor of the campaign was Estes' co-chair, a police officer named Dennis Falk. Two months before election day, Falk shot and killed a suspect who turned out to be a black, mentally retarded, young boy. The black community was furious with Falk, and transferred their anger to Initiative Thirteen.

The tone of the Seattle campaign against Initiative Thirteen was different from those in Miami and St. Paul; it focused consistently on privacy and civil rights. Instead of educating the public about different subcultures in the gay community, they printed effective posters showing an eye peeping through a keyhole and a family living in a fishbowl. High-profile liberal figures, labor unions, and other large organizations including the Church Council of Greater Seattle opposed Initiative Thirteen. David Estes did not have the enthusiasm and momentum modeled by Bryant and other communities though his campaign used many of their tactics. On election day, Initiative Thirteen was rejected by 63%.

, from Fullerton

was in the crowd with Anita Bryant the night she and Save Our Children won the Dade County vote. Greatly impressed by the voter turnout, Briggs had designs to win the race for governor of California for 1978. When he returned from Miami, since there was no gay rights law to overturn, he proposed a law to forbid employing openly gay public school teachers and other workers. The bill, Proposition 6—nicknamed the Briggs Initiative—was written so broadly that it also allowed the dismissal of any public school employee for supporting gay rights including voting against Proposition 6, regardless of their sexual orientation. He stated, "What I am after is to remove those homosexual teachers who through word, thought or deed want to be a public homosexual, to entice young impressionable children into their lifestyle". Briggs announced the proposition on the steps of San Francisco City Hall

, after notifying several local gay organizations of his intentions. The city had experienced an influx of so many gay people in the past ten years that they counted as a quarter of its voting population.

Gay activists, newly alarmed at the threat to their rights, confronted vice president Walter Mondale

at a political rally in San Francisco two weeks after the announcement of Proposition 6. Mondale ran with Jimmy Carter in 1976 on a platform highlighting human rights as their first priority, and he was there to address the subject pertaining to Latin America

. When gay activists interrupted him and demanded he address their issues, he quickly left without a response, and San Francisco Democratic organizers and liberal politicians were furious at the gay activists.

Briggs named his organization California Defend Our Children (CDOC) to avoid legal problems with the Connecticut charity, and used the same strategies as Save Our Children: collages of newspaper headlines about child molesters, and because a proposition was on the ballot regarding the death penalty in California, CDOC campaign literature urged voters to "act now to help protect your family from vicious killers and defend your children from homosexual teachers". Briggs placed minister Lou Sheldon

in charge of CDOC.

A significant difference between the community components in Miami and California was that both Los Angeles and San Francisco had very active and visible gay communities. Founder of Metropolitan Community Church Reverend Troy Perry

, who began his career as a charismatic preacher in the Church of God of Prophecy

but was rejected for being gay, went on a 16-day fast to raise $100,000 and succeeded. Hollywood stars Bette Midler

, Lily Tomlin

, and Richard Pryor

came out in force for the cause, raising another $100,000. In January 1978 Harvey Milk

took office as a supervisor of San Francisco, and the first openly gay man to be elected to office in California. Briggs campaigned for the measure throughout the state, and held a series of public and televised debates with Milk who was very well received by the media, quick to quip and give print-friendly comments. He often made the front page in newspapers in San Francisco with the outrageous things he said. Milk spoke to 350,000 participants of 1978's San Francisco Gay Freedom Day; similar numbers were seen in Los Angeles.

The strategies of gay activists were once again split. David Goodstein and other professional gay men paid an advertising agency to outline their message, which focused on the threat to privacy and the rights of teachers. In The Advocate, Goodstein urged gays not to live up to stereotypes and let the professionals try to win. However, grassroots efforts by longtime activists such as Morris Kight

, who went on a walk across the state to promote voting down the Briggs Initiative, were also effective. Women were highly visible in the campaign, raising about the same amount of money as men. However, when California law was revealed to state that anyone who gave more than $50 to the campaign would have to release his or her name, most of the donations came in at $49, including one by Rock Hudson

.

Due to the broad nature of the law, as it would have allowed the firing of public school employees for the way they voted or spoke their opinions in favor of gay rights, conservative Republican politicians spoke out against it. Primarily, former governor Ronald Reagan

voiced his opinion, saying "Prop. 6 is not needed to protect our children. We have that legal protection now. It could be very costly to implement and has the potential for causing undue harm to people." Reagan's statement turned public opinion against the proposition almost overnight. Gay activists were not optimistic in light of the record of voter turnout against them in the previous year, but they were overwhelmed to learn that on election day more than a million voters turned out to strike down the proposition.

and gave a candid interview to Ladies Home Journal in 1980 where she told the details of her marriage during the campaign. She claimed she had been "married for the wrong reasons" and that she and Green had fought regularly, often considering divorce. Green became her manager and she claimed exhaustion due to being booked for every event available, making $700,000 in 1976. She had checked herself into a Christian psychiatric facility in 1973, and regularly saw psychiatrists and marriage counselors. Her anxiety manifested itself in chest pains, tremors, difficulty swallowing food, and a bout with 24-hour paralysis during a trip to Israel with the Falwell family. Bryant revealed she had received severe criticism from Christians following her divorce. One Canadian pastor expressed doubt to her that she had "ever met the Lord", to her humiliation. As a result of the backlash she received from Christians, Bryant had softened her stances on gay rights: "The church needs to be more loving, unconditionally, and willing to see these people as human beings, to minister to them and try to understand. If I had it to do over, I'd do it again, but not in the same way," and feminism: "The church needs to wake up and find some way to cope with divorce and women's problems that are based on Biblical principles. I believe in the long run God will vindicate me. I've about given up on the fundamentalists, who have become so legalistic and letter-bound to the Bible."

Bryant's career did not recover. She attempted to stage comebacks in Eureka Springs, Arkansas

in 1992, Branson, Missouri

in 1994 ("People who come to my performances are hungry for the truth. They thank me for reminding them of the importance of God and country."), and Pigeon Forge, Tennessee

in 1997. However, at each venue her audiences dwindled and investors were non-existent. By 2002, Bryant and her second husband Charlie Dry had claimed bankruptcy

in three states. As of 2006 Bryant was living in Oklahoma City.

In 2007 Bob Green counted the campaign and its aftermath as factors in strengthening his faith. The breakdown of the marriage he attributes on the pressures put on Bryant, and blames gays and lesbians for his emotional devastation after the divorce: "Their goal was to put (Bryant) out of business and destroy her career. And that's what they did. It's unfair." However, Green said he would not do it again if he had to: "It just wasn't worth it... The trauma, the battling we all got caught up in. I don't want to ever go back to that."

about the legality of teaching evolution

in public schools in 1925 had religious organizations made earnest attempts to influence politics on such a wide scale. The Roe vs. Wade decision legalizing abortion

in 1973, and the introduction of the Equal Rights Amendment

in 1974 that proposed giving women equality in many areas of life not previously considered fueled conservative politics. Fred Fejes credits the Save Our Children campaign as a significant factor in the rise of conservative Christian activism, noting "This was the beginning of the culture wars". Ruth Shack points to the connection between the rise of the New Right

and the Save Our Children campaign: "Back in 1977, there was no organized religious right per se. Anita Bryant was a pioneer."

In the late 1970s the Reverend Jerry Falwell

moved from presiding over the megachurch

Thomas Road Baptist Church

in Lynchburg, Virginia

and hosting the Old Time Gospel Hour, to being involved in politics. Falwell took credit for defeating the Dade County gay rights ordinance and the failure of the ERA in Florida. He developed a campaign called Clean Up America in 1977 that was a fundraising vehicle for his television show. Falwell sent letters asking for donations, which included questionnaires asking “Do you approve of known practicing homosexuals teaching in public schools?” that he promised would be sent to politicians; he distributed information about how to put together political groups to influence elections and lawmakers. In 1979 Falwell spearheaded a coalition of religious groups that included Catholics, fundamentalist Protestants, Mormons, and Orthodox Jews that he called the Moral Majority

, which developed a branch dedicated to political action. Falwell declared in 1965 that he had no business in politics, but justified his involvement and the inevitable mix of religion and government with evidence that the social problems of abortion, pornography

, sexual immorality, and drugs were bringing the United States to a dangerous precipice where communism

would prevail over Christianity.

Falwell claimed that the grassroots

efforts of the Moral Majority—registering millions of voters, informing the public, and using the media—had been a significant factor in the election of President Ronald Reagan

. By 1982 they had a budget of $1 million and millions of volunteers. Around the same time, gay men were being stricken with AIDS

, desperate for money for research and services. Spokesmen for the Moral Majority connected it to God's will, asserting the general public needed protection from "the gay plague", and warned, "If homosexuals are not stopped they will infect the entire nation and America will be destroyed."

sponsored an exhibition of the events surrounding the Save Our Children campaign and displayed it at the Broward County Public Library. According to the curator of the exhibit, Bryant is considered "the best thing to happen to the gay rights movement. She and her cohorts were so over the top that it just completely galvanized the gay rights movement".

San Francisco author Armistead Maupin

was writing his installments of individual stories in a column for the San Francisco Chronicle titled Tales of the City

in 1977. He remembered, "I know what the battle did for me: It forced me to confront my own residual self-loathing and stare it down once and for all by coming out." Maupin used the next installment of Tales to have one of his gay characters come out to his parents who, by remarkable coincidence, Maupin had previously established as Florida citrus growers.

Political activism in American gay communities was transformed by the arrival of AIDS in the early 1980s. When gay men tried in several desperate measures to follow established political channels to bring attention to a disease that afflicted the most cast out members of society only to meet silence from the government, some used direct action

tactics. AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power

(ACT UP), formed by Larry Kramer

in 1987 was a response not only to government forces that downplayed or ignored the seriousness of AIDS in the United States, but also to a timid gay community who were not militant enough. Their first act was to march on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in New York City to protest the FDA for delaying the release of experimental drugs to treat HIV

. They blocked rush hour traffic, had 17 protesters arrested, and appeared on the evening news. ACT UP inspired the establishment of direct action groups Queer Nation

, and the Lesbian Avengers

, that concentrated on gay and lesbian rights and protection.

Miami, Florida

Miami is a city located on the Atlantic coast in southeastern Florida and the county seat of Miami-Dade County, the most populous county in Florida and the eighth-most populous county in the United States with a population of 2,500,625...

, U.S. to overturn a recently legislated county ordinance that banned discrimination in areas of housing, employment, and public accommodation based on sexual orientation

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation describes a pattern of emotional, romantic, or sexual attractions to the opposite sex, the same sex, both, or neither, and the genders that accompany them. By the convention of organized researchers, these attractions are subsumed under heterosexuality, homosexuality,...

. The coalition was publicly headed by celebrity singer Anita Bryant

Anita Bryant

Anita Jane Bryant is an American singer, former Miss Oklahoma beauty pageant winner, and gay rights opponent. She scored four Top 40 hits in the United States in the late 1950s and early 1960s, including "Paper Roses", which reached #5...

, who claimed the ordinance discriminated against her right to teach her children biblical morality. It was a well-organized campaign that initiated a bitter political fight between unprepared gay activists and highly motivated Christian fundamentalists. When the repeal of the ordinance went to a vote, it attracted the largest response of any special election in Dade County

Miami-Dade County, Florida

Miami-Dade County is a county located in the southeastern part of the state of Florida. As of 2010 U.S. Census, the county had a population of 2,496,435, making it the most populous county in Florida and the eighth-most populous county in the United States...

's history, passing by 70%.The gay rights ordinance re-enacted by Dade County commissioners in 1998; it survived a repeal attempt by the Christian Coalition in 2003. (Days Without Sunshine: Anita Bryant's Anti-Gay Crusade, Stonewall Library and Archives. Retrieved on October 23, 2010.)

Save Our Children was the first organized opposition to the gay rights movement

LGBT social movements

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender social movements share inter-related goals of social acceptance of sexual and gender minorities. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people and their allies have a long history of campaigning for what is generally called LGBT rights, also called gay...

, whose beginnings were traced to the Stonewall riots

Stonewall riots

The Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City...

in 1969. The defeat of the ordinance encouraged groups in other cities to attempt to overturn similar laws. In the next year voters in St. Paul, Minnesota, Wichita, Kansas

Wichita, Kansas

Wichita is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kansas.As of the 2010 census, the city population was 382,368. Located in south-central Kansas on the Arkansas River, Wichita is the county seat of Sedgwick County and the principal city of the Wichita metropolitan area...

, and Eugene, Oregon

Eugene, Oregon

Eugene is the second largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon and the seat of Lane County. It is located at the south end of the Willamette Valley, at the confluence of the McKenzie and Willamette rivers, about east of the Oregon Coast.As of the 2010 U.S...

overturned ordinances in those cities, sharing many of the same campaign strategies that were used in Miami. Save Our Children was also involved in Seattle, Washington

Seattle, Washington

Seattle is the county seat of King County, Washington. With 608,660 residents as of the 2010 Census, Seattle is the largest city in the Northwestern United States. The Seattle metropolitan area of about 3.4 million inhabitants is the 15th largest metropolitan area in the country...

, where they were unsuccessful, and heavily influenced Proposition 6—a proposed state law in California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

that would have made the firing of openly

Coming out

Coming out is a figure of speech for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people's disclosure of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity....

gay

Gay

Gay is a word that refers to a homosexual person, especially a homosexual male. For homosexual women the specific term is "lesbian"....

public school employees mandatory—that was rejected by California voters in 1978.

Historians have since connected the overwhelming success of Save Our Children with the organization of conservative Christian participation in political processes. Although forceful Christian involvement had not taken a widespread role in politics in the United States since 1925, within two years the Reverend Jerry Falwell

Jerry Falwell

Jerry Lamon Falwell, Sr. was an evangelical fundamentalist Southern Baptist pastor, televangelist, and a conservative commentator from the United States. He was the founding pastor of the Thomas Road Baptist Church, a megachurch in Lynchburg, Virginia...

developed a coalition of conservative religious groups named the Moral Majority

Moral Majority

The Moral Majority was a political organization of the United States which had an agenda of evangelical Christian-oriented political lobbying...

that influenced the Republican Party

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

to incorporate a social agenda in national politics. Homosexuality, the Equal Rights Amendment

Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment was a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution. The ERA was originally written by Alice Paul and, in 1923, it was introduced in the Congress for the first time...

(ERA), abortion

Abortion

Abortion is defined as the termination of pregnancy by the removal or expulsion from the uterus of a fetus or embryo prior to viability. An abortion can occur spontaneously, in which case it is usually called a miscarriage, or it can be purposely induced...

, and pornography

Pornography

Pornography or porn is the explicit portrayal of sexual subject matter for the purposes of sexual arousal and erotic satisfaction.Pornography may use any of a variety of media, ranging from books, magazines, postcards, photos, sculpture, drawing, painting, animation, sound recording, film, video,...

were among the issues most central to the Moral Majority's priorities until it folded in 1989. For many gay men and lesbian

Lesbian

Lesbian is a term most widely used in the English language to describe sexual and romantic desire between females. The word may be used as a noun, to refer to women who identify themselves or who are characterized by others as having the primary attribute of female homosexuality, or as an...

s, the surprise at the outcome of all the campaigns in 1977 and 1978 instilled a new determination and consolidated activism and communities in many cities where the gay community had not been politically active.

Background

On January 18, 1977, the Dade County Commission approved a law that would outlaw discrimination against homosexuals in employment, housing, and public services. Commissioner Ruth ShackRuth Shack

Ruth Shack was the sponsor of the 1977 Human Rights Ordinance in Miami-Dade County, Florida.Shack was elected to the Metro-Dade County Commission in 1976, 1978 and 1982...

proposed the bill on December 7, 1976 at the request of a gay lobbying organization, named the Dade County Coalition for the Humanistic Rights of Gays, that was less than a year old. The group was headed by three gay activists: Jack Campbell, an owner of 40 gay bathhouse

Gay bathhouse

Gay bathhouses, also known as gay saunas or steam baths, are commercial bathhouses for men to have sex with other men. In gay slang in some regions these venues are also known colloquially as "the baths" or "the tubs," and should not be confused with public bathing.Not all men who visit gay...

s across the United States, political and gay activist Bob Basker

Bob Basker

Bob Basker was a civil rights activist. He first became active in the student peace movement in the 1930s and was politically active throughout his life....

, and Bob Kunst, a local publicist and enthusiast of the Human Potential Movement

Human Potential Movement

The Human Potential Movement arose out of the social and intellectual milieu of the 1960s and formed around the concept of cultivating extraordinary potential that its advocates believed to lie largely untapped in all people...

and proponent of sexual liberation.

Homosexuality in Miami

The general attitude about homosexuality in Miami mirrored many other cities' across the country. Though gay nightlife in the city had enjoyed the same boisterous existence as other forms of entertainment in the 1930s, by the 1950s, the city government worked to shut down as many gay bars as possible and enacted laws making homosexuality and cross-dressing illegal. From 1956 to 1966, the Johns CommitteeFlorida Legislative Investigation Committee

The Florida Legislative Investigation Committee was established by the Florida Legislature in 1956, during the era of the Second Red Scare and the Lavender Scare...

of the Florida Legislature actively sought to root out homosexuals in state employment and in public universities across the state, publishing the inflammatory "Purple Pamphlet," which portrayed all homosexuals as predators and a dire threat to the children of Florida. In the 1960s The Miami Herald

The Miami Herald

The Miami Herald is a daily newspaper owned by The McClatchy Company headquartered on Biscayne Bay in the Omni district of Downtown Miami, Florida, United States...

ran several stories implying the life of area homosexuals as synonymous with pimp

Pimp

A pimp is an agent for prostitutes who collects part of their earnings. The pimp may receive this money in return for advertising services, physical protection, or for providing a location where she may engage clients...

s and child molesters, and the local NBC

NBC

The National Broadcasting Company is an American commercial broadcasting television network and former radio network headquartered in the GE Building in New York City's Rockefeller Center with additional major offices near Los Angeles and in Chicago...

television station aired a documentary entitled "The Homosexual" in 1966 warning viewers that young boys were in danger from predatory men.

The public image of homosexuals changed with liberalized social attitudes of the late 1960s. In 1969, the Stonewall riots

Stonewall riots

The Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City...

occurred in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, marking the start of the gay rights movement. Though gay life in Miami was intensely closeted, and bars were subject to frequent raids, Christ Metropolitan Community Church

Metropolitan Community Church

The Metropolitan Community Church or The Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches is an international Protestant Christian denomination...

—a congregation for gay and lesbian Christians in Miami—was founded in 1970 as a religious outlet, attracting hundreds of parishioners. The 1972 Democratic National Convention

1972 Democratic National Convention

The 1972 Democratic National Convention was the presidential nominating convention of the Democratic Party for the 1972 presidential election. It was held at Miami Beach Convention Center in Miami Beach, Florida on July 10–13, 1972....

was held in Miami, featuring, for the first time, a public speech about the rights of gay men and lesbians by openly

Coming out

Coming out is a figure of speech for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people's disclosure of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity....

gay San Francisco political activist Jim Foster

Jim Foster (activist)

James M. "Jim" Foster was an American LGBT rights and Democratic activist. Foster became active in the early gay rights movement when he moved to San Francisco following his undesirable discharge from the United States Army in 1959 for being homosexual...

. Jack Campbell opened the Miami branch of Club Baths

Club Baths

thumb|2005, Club WashingtonClub Baths is a chain of gay bathhouses in the United States and Canada with particular prominence from the 1960s through the 1990s.At its peak it included 42 bathhouses. It claimed to have at least 500,000 members...

in 1974. When it was raided, he made sure that all charges against those arrested were dropped, filed a lawsuit against the Miami Police Department

Miami Police Department

The Miami Police Department or MPD, often referred to as the City of Miami Police, is the chief police department of the U.S. city of Miami, Florida. Their jurisdiction lies within the actual city limits of Miami, but have mutual aid agreements with neighboring police departments. The current...

prohibiting further harassment, and received a formal apology from the police. Even the depiction of gay men and lesbians in the local newspaper had changed to that of a silent, oppressed minority. By 1977, Miami was one of nearly 40 cities in the U.S. that had passed ordinances outlawing discrimination against gay men and lesbians.

Reaction to the ordinance

When the news of the ordinance proposal was reported in December 1976, a small ripple of protest spread from local churches. Northwest Baptist Church announced it from the pulpit. The news worried one of the church members named Anita BryantAnita Bryant

Anita Jane Bryant is an American singer, former Miss Oklahoma beauty pageant winner, and gay rights opponent. She scored four Top 40 hits in the United States in the late 1950s and early 1960s, including "Paper Roses", which reached #5...

, who was a 36-year-old singer celebrity. Bryant began her career as a local child star on a television show in Oklahoma City

Oklahoma city

Oklahoma City is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma.Oklahoma City may also refer to:*Oklahoma City metropolitan area*Downtown Oklahoma City*Uptown Oklahoma City*Oklahoma City bombing*Oklahoma City National Memorial...

and on Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts

Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts

Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts is an American radio and television variety show which ran on CBS from 1946 until 1958...

. Her young life was marked by frequent moves; her parents divorced each other twice, and she often lived in poverty conditions, but she became a born again Christian at eight years old, and counted her faith and her participation at church as the stabilizing influences in her life. As a child, she asked God to make her a star. She was, by her own admission, remarkably driven and ambitious. In her older teens she became a beauty pageant contestant, winning Miss Oklahoma

Miss Oklahoma

The Miss Oklahoma competition selects a winner to compete on behalf of Oklahoma in the Miss America pageant. Miss Oklahoma has won the crown on five occasions. Also, in the years when city representatives were common, Norma Smallwood won, competing as Miss Tulsa, giving the state of Oklahoma a...

and second runner-up as Miss America

Miss America

The Miss America pageant is a long-standing competition which awards scholarships to young women from the 50 states plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands...

. In 1960, she married a Miami disc jockey

Disc jockey

A disc jockey, also known as DJ, is a person who selects and plays recorded music for an audience. Originally, "disc" referred to phonograph records, not the later Compact Discs. Today, the term includes all forms of music playback, no matter the medium.There are several types of disc jockeys...

named Bob Green and became a professional singer, finding some success with three gold records featuring popular, patriotic, and Gospel standards. She performed with the Bob Hope Christmas tour, entertaining troops serving overseas, and sang at President Lyndon Johnson's funeral in 1973. Since 1969 she had been employed regionally by the Florida Citrus Commission endorsing Florida orange juice in television commercials. She also advertised for Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola

Coca-Cola is a carbonated soft drink sold in stores, restaurants, and vending machines in more than 200 countries. It is produced by The Coca-Cola Company of Atlanta, Georgia, and is often referred to simply as Coke...

, Tupperware

Tupperware

Tupperware is the name of a home products line that includes preparation, storage, containment, and serving products for the kitchen and home, which were first introduced to the public in 1946....

, Kraft Foods

Kraft Foods

Kraft Foods Inc. is an American confectionery, food and beverage conglomerate. It markets many brands in more than 170 countries. 12 of its brands annually earn more than $1 billion worldwide: Cadbury, Jacobs, Kraft, LU, Maxwell House, Milka, Nabisco, Oscar Mayer, Philadelphia, Trident, Tang...

and Holiday Inn

Holiday Inn

Holiday Inn is a brand of hotels, formally a economy motel chain, forming part of the British InterContinental Hotels Group . It is one of the world's largest hotel chains with 238,440 bedrooms and 1,301 hotels globally. There are currently 5 hotels in the pipeline...

s. Bryant's talent agent was married to Ruth Shack; Bryant had contributed $1,000 to her campaign.

Initially Bryant kept her concerns low-key, despite her pastor's pleadings to become involved. She wrote a letter to the county commission and called Ruth Shack, expressing her concerns. Her most significant objection to the ordinance was that it would allow homosexuals to work in parochial school

Parochial school

A parochial school is a school that provides religious education in addition to conventional education. In a narrower sense, a parochial school is a Christian grammar school or high school which is part of, and run by, a parish.-United Kingdom:...

s; all four of Bryant's children attended a local private Christian school. She admitted she was largely ignorant of any specific dangers homosexuals presented, but when she was sent graphic images of homosexual acts, and shown photos of child pornography

Child pornography

Child pornography refers to images or films and, in some cases, writings depicting sexually explicit activities involving a child...

by a local police sergeant visiting her church, she was horrified.Bryant gave a candid interview to Playboy magazine, printed in May 1978 where she admitted that she knew of homosexuals in show business but was unaware of the "nitty gritty" of their sexual behavior until her husband described them to her. She professed being most astonished that they ate each others' sperm, and equated the act with the immorality of destroying the Seed of Life. Bryant also claimed never to have heard of Alfred Kinsey

Alfred Kinsey

Alfred Charles Kinsey was an American biologist and professor of entomology and zoology, who in 1947 founded the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, now known as the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction, as well as producing the Kinsey Reports and the Kinsey...

's study that estimated one out of five males had had some sexual contact with another male; or any information about homosexual behavior in animals. The interviewer, Ken Kelley, wrote a companion piece to the interview, stating that she was impossible to "pigeonhole" due to her deliberate enigmatic persona: "She is a confection of contradictions: pristine nun and gamy tease. Old pro who's paid her dues and wide-eyed waif who's still seeking the jackpot. Guilt-wracked sinner who's terrified of hell and perfervid white knight who's determined to lead mankind on a forced march into paradise. Independent spirit, cowering wife. Chaplain one minute, warden the next. She is a demonstrably intelligent woman who stays steadfastly ignorant." For months Bryant called Kelley just to talk, even though she knew she would not be portrayed favorably in the magazine. Kelley and a few others concluded that Bryant was simply very lonely. (Young, p. 39.) Bryant credited her inspiration later to her 9-year-old daughter suggesting God could assist with her cause; then she decided to take a more public role.

At the time of the commission's vote in January, the boardroom was crowded with people who held some kind of interest in the issue. Busloads of churchgoers arrived from as far away as Homestead

Homestead, Florida

Homestead is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States nestled between Biscayne National Park to the east and Everglades National Park to the west. Homestead is primarily a Miami suburb and a major agricultural area....

and picketed outside; there was no corresponding organized show of support for the ordinance. Inside the boardroom, supporters and opposers took the entire allotted time to speak. Bryant reflected most of those opposing the law, telling the Dade County Commission, "The ordinance condones immorality and discriminates against my children's rights to grow up in a healthy, decent community". The few members of the Dade County Coalition for the Humanistic Rights of Gays who were present were stunned, as was Ruth Shack, at the number and force of the hundreds of protesters who filled the commission room, and held placards and pickets outside. But the ordinance passed by a 5-3 vote.

Dade County ordinance 77-4

Strategy

Mike Thompson discovered in a poll taken in March 1977 that women in Dade County opposed repealing the measure two to one; they saw their gay friends as relatively harmless. Save Our Children's strategy, therefore, worked to prove that homosexuals were amoral, promiscuous, and defiant of traditional gender roles, and that they were a specific danger to children. Bryant took this strategy as a crusade, delivering speeches that intoned that Dade County's passing of the ordinance "guts the law on the side of the unrighteous. If homosexuals are allowed to change the law in their favor, why not prostitutes, thieves, or murderers?" She specifically connected homosexuals with child molesters, saying "Some of the stories I could tell you of child recruitment and child abuse by homosexuals would turn your stomach." Bryant resented the media depiction of her as hateful, saying that her inspiration came "out of love—not only love for God's commandment and His word, but love for my children and yours. Yes, and even love for all sinners—even homosexuals."The Save Our Children campaign produced a local television commercial showing the "wholesome entertainment" of the Orange Bowl Parade (which Bryant hosted), contrasting that with highly sexualized images of the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade

San Francisco Pride

The San Francisco Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Pride Celebration, usually known as San Francisco Pride, is a parade and festival held in June each year in San Francisco to celebrate the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people and their allies...

, including men in leather harnesses kissing each other, dancing drag queen

Drag queen

A drag queen is a man who dresses, and usually acts, like a caricature woman often for the purpose of entertaining. There are many kinds of drag artists and they vary greatly, from professionals who have starred in films to people who just try it once. Drag queens also vary by class and culture and...

s, and topless women. The commercial's announcer accused Miami's gay community of trying to turn Miami into the "hotbed of homosexuality" that San Francisco had become. Full-page newspaper ads were run in The Miami Herald

The Miami Herald

The Miami Herald is a daily newspaper owned by The McClatchy Company headquartered on Biscayne Bay in the Omni district of Downtown Miami, Florida, United States...

, showing collections of headlines announcing teachers having sex with their students, children in prostitution rings, and homosexuals involved with youth organizations, followed by the question "Are all homosexuals nice? ... There is no 'human right' to corrupt our children."