Microbial metabolism

Encyclopedia

Microbial metabolism is the means by which a microbe obtains the energy and nutrients (e.g. carbon

) it needs to live and reproduce. Microbes use many different types of metabolic

strategies and species can often be differentiated from each other based on metabolic characteristics. The specific metabolic properties of a microbe are the major factors in determining that microbe’s ecological niche

, and often allow for that microbe to be useful in industrial processes

or responsible for biogeochemical

cycles.

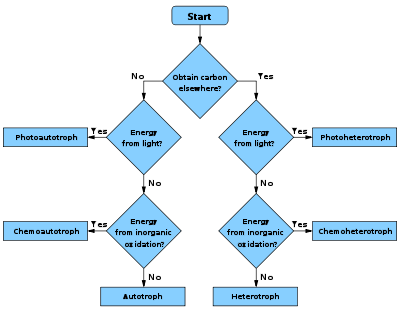

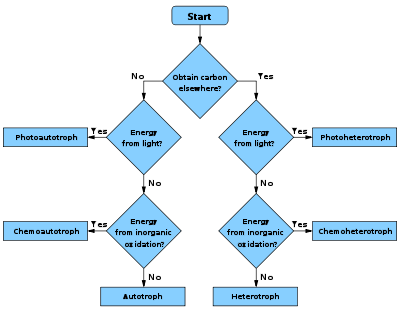

All microbial metabolisms can be arranged according to three principles:

All microbial metabolisms can be arranged according to three principles:

1. How the organism obtains carbon for synthesising cell mass:

2. How the organism obtains reducing equivalent

s used either in energy conservation or in biosynthetic reactions:

3. How the organism obtains energy for living and growing:

In practice, these terms are almost freely combined. Typical examples are as follows:

or parasitism

, properties also found in some bacteria such as Bdellovibrio

(an intracellular parasite of other bacteria, causing death of its victims) and Myxobacteria such as Myxococcus (predators of other bacteria which are killed and lysed by cooperating swarms of many single cells of Myxobacteria). Most pathogen

ic bacteria can be viewed as heterotrophic parasites of humans or the other eukaryotic species they affect. Heterotrophic microbes are extremely abundant in nature and are responsible for the breakdown of large organic polymer

s such as cellulose

, chitin

or lignin

which are generally indigestible to larger animals. Generally, the breakdown of large polymers to carbon dioxide (mineralization

) requires several different organisms, with one breaking down the polymer into its constituent monomers, one able to use the monomers and excreting simpler waste compounds as by-products, and one able to use the excreted wastes. There are many variations on this theme, as different organisms are able to degrade different polymers and secrete different waste products. Some organisms are even able to degrade more recalcitrant compounds such as petroleum compounds or pesticides, making them useful in bioremediation

.

Biochemically, prokaryotic heterotrophic metabolism is much more versatile than that of eukaryotic organisms, although many prokaryotes share the most basic metabolic models with eukaryotes, e. g. using glycolysis

(also called EMP pathway) for sugar metabolism and the citric acid cycle

to degrade acetate

, producing energy in the form of ATP

and reducing power in the form of NADH or quinols. These basic pathways are well conserved because they are also involved in biosynthesis of many conserved building blocks needed for cell growth (sometimes in reverse direction). However, many bacteria

and archaea

utilize alternative metabolic pathways other than glycolysis and the citric acid cycle. A well-studied example is sugar metabolism via the keto-deoxy-phosphogluconate pathway (also called ED pathway) in Pseudomonas

. Moreover, there is a third alternative sugar-catabolic pathway used by some bacteria, the pentose phosphate pathway

. The metabolic diversity and ability of prokaryotes to use a large variety of organic compounds arises from the much deeper evolutionary history and diversity of prokaryotes, as compared to eukaryotes. It is also noteworthy that the mitochondrion

, the small membrane-bound intracellular organelle that is the site of eukaryotic energy metabolism, arose from the endosymbiosis of a bacterium related to obligate intracellular Rickettsia

, and also to plant-associated Rhizobium

or Agrobacterium

. Therefore it is not surprising that all mitrochondriate eukaryotes share metabolic properties with these Proteobacteria

. Most microbes respire

(use an electron transport chain

), although oxygen

is not the only terminal electron acceptor that may be used. As discussed below, the use of terminal electron acceptors other than oxygen has important biogeochemical consequences.

instead of oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor. This means that these organisms do not use an electron transport chain to oxidize NADH to NAD+ and therefore must have an alternative method of using this reducing power and maintaining a supply of NAD+ for the proper functioning of normal metabolic pathways (e.g. glycolysis). As oxygen is not required, fermentative organisms are anaerobic

. Many organisms can use fermentation under anaerobic conditions and aerobic respiration when oxygen is present. These organisms are facultative anaerobes. To avoid the overproduction of NADH, obligately

fermentative organisms usually do not have a complete citric acid cycle. Instead of using an ATPase

as in respiration

, ATP in fermentative organisms is produced by substrate-level phosphorylation

where a phosphate

group is transferred from a high-energy organic compound to ADP

to form ATP. As a result of the need to produce high energy phosphate-containing organic compounds (generally in the form of CoA

-esters) fermentative organisms use NADH and other cofactor

s to produce many different reduced metabolic by-products, often including hydrogen

gas (H2). These reduced organic compounds are generally small organic acid

s and alcohol

s derived from pyruvate, the end product of glycolysis

. Examples include ethanol

, acetate

, lactate

, and butyrate

. Fermentative organisms are very important industrially and are used to make many different types of food products. The different metabolic end products produced by each specific bacterial species are responsible for the different tastes and properties of each food.

Not all fermentative organisms use substrate-level phosphorylation

. Instead, some organisms are able to couple the oxidation of low-energy organic compounds directly to the formation of a proton (or sodium) motive force and therefore ATP synthesis. Examples of these unusual forms of fermentation include succinate fermentation by Propionigenium modestum and oxalate

fermentation by Oxalobacter formigenes

. These reactions are extremely low-energy yielding. Humans and other higher animals also use fermentation to produce lactate

from excess NADH, although this is not the major form of metabolism as it is in fermentative microorganisms.

, methyl amines, formaldehyde

, and formate

. Several other less common substrates may also be used for metabolism, all of which lack carbon-carbon bonds. Examples of methylotrophs include the bacteria Methylomonas

and Methylobacter. Methanotroph

s are a specific type of methylotroph that are also able to use methane

(CH4) as a carbon source by oxidizing it sequentially to methanol (CH3OH), formaldehyde (CH2O), formate (HCOO-), and carbon dioxide CO2 initially using the enzyme methane monooxygenase

. As oxygen is required for this process, all (conventional) methanotrophs are obligate aerobe

s. Reducing power in the form of quinone

s and NADH is produced during these oxidations to produce a proton motive force and therefore ATP generation. Methylotrophs and methanotrophs are not considered as autotrophic, because they are able to incorporate some of the oxidized methane (or other metabolites) into cellular carbon before it is completely oxidized to CO2 (at the level of formaldehyde), using either the serine pathway (Methylosinus, Methylocystis) or the ribulose monophosphate pathway (Methylococcus), depending on the species of methylotroph.

In addition to aerobic methylotrophy, methane can also be oxidized anaerobically. This occurs by a consortium of sulfate-reducing bacteria and relatives of methanogen

ic Archaea

working syntrophically (see below). Little is currently known about the biochemistry and ecology of this process.

Methanogenesis

is the biological production of methane. It is carried out by methanogens, strictly anaerobic

Archaea such as Methanococcus

, Methanocaldococcus

, Methanobacterium

,

Methanothermus

, Methanosarcina

, Methanosaeta

and Methanopyrus

. The biochemistry of methanogenesis is unique in nature in its use of a number of unusual cofactor

s to sequentially reduce methanogenic substrates to methane, such as coenzyme M

and methanofuran

. These cofactors are responsible (among other things) for the establishment of a proton

gradient across the outer membrane thereby driving ATP synthesis. Several types of methanogenesis occur, differing in the starting compounds oxidized. Some methanogens reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) to methane (CH4) using electrons (most often) from hydrogen gas (H2) chemolithoautotrophically. These methanogens can often be found in environments containing fermentative organisms. The tight association of methanogens and fermentative bacteria can be considered to be syntrophic (see below) because the methanogens, which rely on the fermentors for hydrogen, relieve feedback inhibition of the fermentors by the build-up of excess hydrogen that would otherwise inhibit their growth. This type of syntrophic relationship is specifically known as interspecies hydrogen transfer. A second group of methanogens use methanol (CH3OH) as a substrate for methanogenesis. These are chemoorganotrophic, but still autotrophic in using CO2 as only carbon source. The biochemistry of this process is quite different from that of the carbon dioxide-reducing methanogens. Lastly, a third group of methanogens produce both methane and carbon dioxide from acetate

(CH3COO-) with the acetate being split between the two carbons. These acetate-cleaving organisms are the only chemoorganoheterotrophic methanogens. All autotrophic methanogens use a variation of the acetyl-CoA pathway to fix CO2 and obtain cellular carbon.

that, on its own, would be energetically unfavorable. The best studied example of this process is the oxidation of fermentative end products (such as acetate, ethanol

and butyrate

) by organisms such as Syntrophomonas. Alone, the oxidation of butyrate to acetate and hydrogen gas is energetically unfavorable. However, when a hydrogenotrophic (hydrogen-using) methanogen is present the use of the hydrogen gas will significantly lower the concentration of hydrogen (down to 10−5 atm) and thereby shift the equilibrium

of the butyrate oxidation reaction under standard conditions (ΔGº’) to non-standard conditions (ΔG’). Because the concentration of one product is lowered, the reaction is "pulled" towards the products and shifted towards net energetically favorable conditions (for butyrate oxidation: ΔGº’= +48.2 kJ/mol, but ΔG' = -8.9 kJ/mol at 10−5 atm hydrogen and even lower if also the initially produced acetate is further metabolized by methanogens). Conversely, the available free energy from methanogenesis is lowered from ΔGº’= -131 kJ/mol under standard conditions to ΔG' = -17 kJ/mol at 10−5 atm hydrogen. This is an example of intraspecies hydrogen transfer. In this way, low energy-yielding carbon sources can be used by a consortium of organisms to achieve further degradation and eventual mineralization

of these compounds. These reactions help prevent the excess sequestration of carbon over geologic time scales, releasing it back to the biosphere in usable forms such as methane and CO2.

s during respiration use oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor, anaerobic organism

s use other electron acceptors. These inorganic compounds have a lower reduction potential than oxygen, meaning that respiration

is less efficient in these organisms and leads to slower growth rates than aerobes. Many facultative anaerobes can use either oxygen or alternative terminal electron acceptors for respiration depending on the environmental conditions.

Most respiring anaerobes are heterotrophs, although some do live autotrophically. All of the processes described below are dissimilative, meaning that they are used during energy production and not to provide nutrients for the cell (assimilative). Assimilative pathways for many forms of anaerobic respiration

are also known.

(NO3-) as a terminal electron acceptor. It is a widespread process that is used by many members of the Proteobacteria. Many facultative anaerobes use denitrification because nitrate, like oxygen, has a high reduction potential. Many denitrifying bacteria can also use ferric iron

(Fe3+) and some organic electron acceptor

s. Denitrification involves the stepwise reduction of nitrate to nitrite

(NO2-), nitric oxide

(NO), nitrous oxide

(N2O), and dinitrogen (N2) by the enzymes nitrate reductase

, nitrite reductase

, nitric oxide reductase, and nitrous oxide reductase, respectively. Protons are transported across the membrane by the initial NADH reductase, quinones, and nitrous oxide reductase to produce the electrochemical gradient critical for respiration. Some organisms (e.g. E. coli) only produce nitrate reductase and therefore can accomplish only the first reduction leading to the accumulation of nitrite. Others (e.g. Paracoccus denitrificans

or Pseudomonas stutzeri

) reduce nitrate completely. Complete denitrification is an environmentally significant process because some intermediates of denitrification (nitric oxide and nitrous oxide) are important greenhouse gas

es that react with sunlight

and ozone

to produce nitric acid, a component of acid rain

. Denitrification is also important in biological wastewater treatment

where it is used to reduce the amount of nitrogen released into the environment thereby reducing eutrophication

.

reduction is a relatively energetically poor process used by many Gram negative bacteria found within the δ-Proteobacteria, Gram-positive organisms relating to Desulfotomaculum

or the archaeon Archaeoglobus

. Hydrogen sulfide

(H2S) is produced as a metabolic end product. For sulfate reduction electron donors and energy are needed.

s, while others are autotrophic, using hydrogen gas (H2) as an electron donor. Some unusual autotrophic sulfate-reducing bacteria (e.g. Desulfotignum phosphitoxidans

) can use phosphite

(HPO3-) as an electron donor whereas others (e.g. Desulfovibrio sulfodismutans

, Desulfocapsa thiozymogenes

, Desulfocapsa sulfoexigens

) are capable of sulfur disproportionation (splitting one compound into two different compounds, in this case an electron donor and an electron acceptor) using elemental sulfur (S0), sulfite (SO), and thiosulfate (S2O32-) to produce both hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and sulfate (SO).

(SO) and AMP

. In organisms that use carbon compounds as electron donors, the ATP consumed is accounted for by fermentation of the carbon substrate. The hydrogen produced during fermentation is actually what drives respiration during sulfate reduction.

in all homoacetogens occurs by the acetyl-CoA pathway. This pathway is also used for carbon fixation by autotrophic sulfate-reducing bacteria and hydrogenotrophic methanogens. Often homoacetogens can also be fermentative, using the hydrogen and carbon dioxide produced as a result of fermentation to produce acetate, which is secreted as an end product.

and Geobacter metallireducens

. Since some ferric iron-reducing bacteria (e.g. G. metallireducens) can use toxic hydrocarbon

s such as toluene

as a carbon source, there is significant interest in using these organisms as bioremediation agents in ferric iron-rich contaminated aquifer

s.

Although ferric iron is the most prevalent inorganic electron acceptor, a number of organisms (including the iron-reducing bacteria mentioned above) can use other inorganic ions in anaerobic respiration. While these processes may often be less significant ecologically, they are of considerable interest for bioremediation, especially when heavy metals

or radionuclide

s are used as electron acceptors. Examples include:

TMAO is a chemical commonly produced by fish

, and when reduced to TMA produces a strong odor. DMSO is a common marine and freshwater chemical which is also odiferous when reduced to DMS. Reductive dechlorination is the process by which chlorinated organic compounds are reduced to form their non-chlorinated endproducts. As chlorinated organic compounds are often important (and difficult to degrade) environmental polutants, reductive dechlorination is an important process in bioremediation.

causing proton pumping via electron transfer to various quinones and cytochrome

s. In many organisms, a second cytoplasmic hydrogenase is used to generate reducing power in the form of NADH, which is subsequently used to fix carbon dioxide via the Calvin cycle

. Hydrogen-oxidizing organisms, such as Cupriavidus necator (formerly Ralstonia eutropha

), often inhabit oxic-anoxic interfaces in nature to take advantage of the hydrogen produced by anaerobic fermentative organisms while still maintaining a supply of oxygen.

(H2SO4). A classic example of a sulfur-oxidizing bacterium is Beggiatoa

, a microbe originally described by Sergei Winogradsky

, one of the founders of environmental microbiology

. Another example is Paracoccus

. Generally, the oxidation of sulfide occurs in stages, with inorganic sulfur being stored either inside or outside of the cell until needed. This two step process occurs because energetically sulfide is a better electron donor than inorganic sulfur or thiosulfate, allowing for a greater number of protons to be translocated across the membrane. Sulfur-oxidizing organisms generate reducing power for carbon dioxide fixation via the Calvin cycle using reverse electron flow

, an energy-requiring process that pushes the electrons against their thermodynamic gradient to produce NADH. Biochemically, reduced sulfur compounds are converted to sulfite (SO) and subsequently converted to sulfate (SO) by the enzyme sulfite oxidase

. Some organisms, however, accomplish the same oxidation using a reversal of the APS reductase system used by sulfate-reducing bacteria (see above). In all cases the energy liberated is transferred to the electron transport chain for ATP and NADH production. In addition to aerobic sulfur oxidation, some organisms (e.g. Thiobacillus denitrificans) use nitrate (NO3-) as a terminal electron acceptor and therefore grow anaerobically.

Ferrous iron

is a soluble form of iron that is stable at extremely low pH

s or under anaerobic conditions. Under aerobic, moderate pH conditions ferrous iron is oxidized spontaneously to the ferric (Fe3+) form and is hydrolyzed abiotically to insoluble ferric hydroxide (Fe(OH)3). There are three distinct types of ferrous iron-oxidizing microbes. The first are acidophile

s, such as the bacteria Acidithiobacillus ferooxidans and Leptospirrillum ferrooxidans, as well as the archaeon Ferroplasma

. These microbes oxidize iron in environments that have a very low pH and are important in acid mine drainage

. The second type of microbes oxidize ferrous iron at cirum-neutral pH. These micro-organisms (for example Gallionella ferruginea or Leptothrix ochracea) live at the oxic-anoxic interfaces and are microaerophiles. The third type of iron-oxidizing microbes are anaerobic photosynthetic bacteria such as Rhodopseudomonas, which use ferrous iron to produce NADH for autotrophic carbon dioxide fixation. Biochemically, aerobic iron oxidation is a very energetically poor process which therefore requires large amounts of iron to be oxidized by the enzyme rusticyanin to facilitate the formation of proton motive force. Like sulfur oxidation, reverse electron flow must be used to form the NADH used for carbon dioxide fixation via the Calvin cycle.

(NH3) is converted to nitrate (NO3-). Nitrification is actually the net result of two distinct processes: oxidation of ammonia to nitrite (NO2-) by nitrosifying bacteria (e.g. Nitrosomonas

) and oxidation of nitrite to nitrate by the nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (e.g. Nitrobacter

). Both of these processes are extremely energetically poor leading to very slow growth rates for both types of organisms. Biochemically, ammonia oxidation occurs by the stepwise oxidation of ammonia to hydroxylamine

(NH2OH) by the enzyme ammonia monooxygenase in the cytoplasm

, followed by the oxidation of hydroxylamine to nitrite by the enzyme hydroxylamine oxidoreductase in the periplasm.

Electron and proton cycling are very complex but as a net result only one proton is translocated across the membrane per molecule of ammonia oxidized. Nitrite reduction is much simpler, with nitrite being oxidized by the enzyme nitrite oxidoreductase

coupled to proton translocation by a very short electron transport chain, again leading to very low growth rates for these organisms. Oxygen is required in both ammonia and nitrite oxidation, meaning that both nitrosifying and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria are aerobes. As in sulfur and iron oxidation, NADH for carbon dioxide fixation using the Calvin cycle is generated by reverse electron flow, thereby placing a further metabolic burden on an already energy-poor process.

(e.g. Candidatus Brocadia anammoxidans

) and involves the coupling of ammonia oxidation to nitrite reduction. As oxygen is not required for this process these organisms are strict anaerobes. Amazingly, hydrazine

(N2H4 - rocket fuel) is produced as an intermediate during anammox metabolism. To deal with the high toxicity of hydrazine, anammox bacteria contain a hydrazine-containing intracellular organelle called the anammoxasome, surrounded by highly compact (and unusual) ladderane

lipid membrane. These lipids are unique in nature, as is the use of hydrazine as a metabolic intermediate. Anammox organisms are autotrophs although the mechanism for carbon dioxide fixation is unclear. Because of this property, these organisms could be used in industry to remove nitrogen in wastewater treatment

processes. Anammox has also been shown have widespread occurrence in anaerobic aquatic systems and has been speculated to account for approximately 50% of nitrogen gas production in the ocean.

and organic compound

s such as carbohydrate

s, lipid

s, and protein

s. Of these, algae

are particularly significant because they are oxygenic, using water as an electron donor

for electron transfer during photosynthesis. Phototrophic bacteria are found in the phyla Cyanobacteria, Chlorobi, Proteobacteria

, Chloroflexi

, and Firmicutes

. Along with plants these microbes are responsible for all biological generation of oxygen gas on Earth

. Because chloroplast

s were derived from a lineage of the Cyanobacteria, the general principles of metabolism in these endosymbiont

s can also be applied to chloroplasts. In addition to oxygenic photosynthesis, many bacteria can also photosynthesize anaerobically, typically using sulfide (H2S) as an electron donor to produce sulfate. Inorganic sulfur (S0), thiosulfate (S2O32-) and ferrous iron (Fe2+) can also be used by some organisms. Phylogenetically, all oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria are Cyanobacteria, while anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria belong to the purple bacteria (Proteobacteria), Green sulfur bacteria

(e.g. Chlorobium

), Green non-sulfur bacteria (e.g. Chloroflexus), or the heliobacteria

(Low %G+C Gram positives). In addition to these organisms, some microbes (e.g. the Archaeon Halobacterium

or the bacterium Roseobacter, among others) can utilize light to produce energy using the enzyme bacteriorhodopsin

, a light-driven proton pump. However, there are no known Archaea that carry out photosynthesis.

As befits the large diversity of photosynthetic bacteria, there are many different mechanisms by which light is converted into energy for metabolism. All photosynthetic organisms locate their photosynthetic reaction centers within a membrane, which may be invaginations of the cytoplasmic membrane (Proteobacteria), thylakoid membranes (Cyanobacteria), specialized antenna structures called chlorosome

s (Green sulfur and non-sulfur bacteria), or the cytoplasmic membrane itself (heliobacteria). Different photosynthetic bacteria also contain different photosynthetic pigments, such as chlorophyll

s and carotenoids, allowing them to take advantage of different portions of the electromagnetic spectrum

and thereby inhabit different niche

s. Some groups of organisms contain more specialized light-harvesting structures (e.g. phycobilisome

s in Cyanobacteria and chlorosomes in Green sulfur and non-sulfur bacteria), allowing for increased efficiency in light utilization.

Biochemically, anoxygenic photosynthesis is very different from oxygenic photosynthesis. Cyanobacteria (and by extension, chloroplasts) use the Z scheme of electron flow in which electrons eventually are used to form NADH. Two different reaction centers (photosystems) are used and proton motive force is generated both by using cyclic electron flow and the quinone pool. In anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria, electron flow is cyclic, with all electrons used in photosynthesis eventually being transferred back to the single reaction center. A proton motive force is generated using only the quinone pool. In heliobacteria, Green sulfur, and Green non-sulfur bacteria, NADH is formed using the protein ferredoxin

, an energetically favorable reaction. In purple bacteria, NADH is formed by reverse electron flow due to the lower chemical potential of this reaction center. In all cases, however, a proton motive force is generated and used to drive ATP production via an ATPase.

Most photosynthetic microbes are autotrophic, fixing carbon dioxide via the Calvin cycle. Some photosynthetic bacteria (e.g. Chloroflexus) are photoheterotrophs, meaning that they use organic carbon compounds as a carbon source for growth. Some photosynthetic organisms also fix nitrogen (see below).

, dinitrogen gas (N2) is generally biologically inaccessible due to its high activation energy

. Throughout all of nature, only specialized bacteria and Archaea are capable of nitrogen fixation, converting dinitrogen gas into ammonia (NH3), which is easily assimilated by all organisms. These prokaryotes, therefore, are very important ecologically and are often essential for the survival of entire ecosystems. This is especially true in the ocean, where nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria are often the only sources of fixed nitrogen, and in soils, where specialized symbioses exist between legumes and their nitrogen-fixing partners to provide the nitrogen needed by these plants for growth.

Nitrogen fixation can be found distributed throughout nearly all bacterial lineages and physiological classes but is not a universal property. Because the enzyme nitrogenase

, responsible for nitrogen fixation, is very sensitive to oxygen which will inhibit it irreversibly, all nitrogen-fixing organisms must possess some mechanism to keep the concentration of oxygen low. Examples include:

The production and activity of nitrogenases is very highly regulated, both because nitrogen fixation is an extremely energetically expensive process (16-24 ATP are used per N2 fixed) and due to the extreme sensitivity of the nitrogenase to oxygen.

Carbon

Carbon is the chemical element with symbol C and atomic number 6. As a member of group 14 on the periodic table, it is nonmetallic and tetravalent—making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds...

) it needs to live and reproduce. Microbes use many different types of metabolic

Metabolism

Metabolism is the set of chemical reactions that happen in the cells of living organisms to sustain life. These processes allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. Metabolism is usually divided into two categories...

strategies and species can often be differentiated from each other based on metabolic characteristics. The specific metabolic properties of a microbe are the major factors in determining that microbe’s ecological niche

Ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is a term describing the relational position of a species or population in its ecosystem to each other; e.g. a dolphin could potentially be in another ecological niche from one that travels in a different pod if the members of these pods utilize significantly different food...

, and often allow for that microbe to be useful in industrial processes

Biotechnology

Biotechnology is a field of applied biology that involves the use of living organisms and bioprocesses in engineering, technology, medicine and other fields requiring bioproducts. Biotechnology also utilizes these products for manufacturing purpose...

or responsible for biogeochemical

Biogeochemistry

Biogeochemistry is the scientific discipline that involves the study of the chemical, physical, geological, and biological processes and reactions that govern the composition of the natural environment...

cycles.

Types of microbial metabolism

1. How the organism obtains carbon for synthesising cell mass:

- autotrophAutotrophAn autotroph, or producer, is an organism that produces complex organic compounds from simple inorganic molecules using energy from light or inorganic chemical reactions . They are the producers in a food chain, such as plants on land or algae in water...

ic – carbon is obtained from carbon dioxideCarbon dioxideCarbon dioxide is a naturally occurring chemical compound composed of two oxygen atoms covalently bonded to a single carbon atom...

(CO2) - heterotrophHeterotrophA heterotroph is an organism that cannot fix carbon and uses organic carbon for growth. This contrasts with autotrophs, such as plants and algae, which can use energy from sunlight or inorganic compounds to produce organic compounds such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins from inorganic carbon...

ic – carbon is obtained from organic compoundOrganic compoundAn organic compound is any member of a large class of gaseous, liquid, or solid chemical compounds whose molecules contain carbon. For historical reasons discussed below, a few types of carbon-containing compounds such as carbides, carbonates, simple oxides of carbon, and cyanides, as well as the...

s - mixotrophMixotrophA mixotroph is a microorganism that can use a mix of different sources of energy and carbon. Possible are alternations between photo- and chemotrophy, between litho- and organotrophy, between auto- and heterotrophy or a combination of it...

ic – carbon is obtained from both organic compounds and by fixing carbon dioxide

2. How the organism obtains reducing equivalent

Reducing equivalent

In biochemistry, the term reducing equivalent refers to any of a number of chemical species which transfer the equivalent of one electron in redox reactions...

s used either in energy conservation or in biosynthetic reactions:

- lithotrophLithotrophA lithotroph is an organism that uses an inorganic substrate to obtain reducing equivalents for use in biosynthesis or energy conservation via aerobic or anaerobic respiration. Known chemolithotrophs are exclusively microbes; No known macrofauna possesses the ability to utilize inorganic...

ic – reducing equivalents are obtained from inorganic compoundInorganic compoundInorganic compounds have traditionally been considered to be of inanimate, non-biological origin. In contrast, organic compounds have an explicit biological origin. However, over the past century, the classification of inorganic vs organic compounds has become less important to scientists,...

s - organotrophOrganotrophAn organotroph is an organism that obtains hydrogen or electrons from organic substrates . Antonym: Lithotroph- See also :* Lithotroph* Heterotroph* Primary nutritional groups...

ic – reducing equivalents are obtained from organic compounds

3. How the organism obtains energy for living and growing:

- chemotrophChemotrophChemotrophs are organisms that obtain energy by the oxidation of electron donors in their environments. These molecules can be organic or inorganic . The chemotroph designation is in contrast to phototrophs, which utilize solar energy...

ic – energy is obtained from external chemical compoundChemical compoundA chemical compound is a pure chemical substance consisting of two or more different chemical elements that can be separated into simpler substances by chemical reactions. Chemical compounds have a unique and defined chemical structure; they consist of a fixed ratio of atoms that are held together...

s - phototrophPhototrophPhototrophs are the organisms that carry out photosynthesis to acquire energy. They use the energy from sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into organic material to be utilized in cellular functions such as biosynthesis and respiration.Most phototrophs are autotrophs, also known as...

ic – energy is obtained from light

In practice, these terms are almost freely combined. Typical examples are as follows:

- chemolithoautotrophs obtain energy from the oxidation of inorganic compounds and carbon from the fixation of carbon dioxide. Examples: Nitrifying bacteria, Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria, Iron-oxidizing bacteria, Knallgas-bacteriaKnallgas-bacteriaHydrogen oxidizing bacteria, or sometimes Knallgas-bacteria, are bacteria which oxidize hydrogen. See microbial metabolism . These bacteria include Hydrogenobacter thermophilus, Hydrogenovibrio marinus, and Helicobacter pylori. There are both Gram positive and Gram negative knallgas bacteria.Most...

- photolithoautotrophs obtain energy from light and carbon from the fixation of carbon dioxide, using reducing equivalents from inorganic compounds. Examples: Cyanobacteria (water (H2O) as reducing equivalent donor), Chlorobiaceae, ChromatiaceaeChromatiaceaeThe Chromatiaceae are the main family of purple sulfur bacteria. They are distinguished by producing sulfur globules within their cells. These are an intermediate in the oxidization of sulfide, which is ultimately converted into sulfate, and may serve as a reserve. Members are found in both...

(hydrogen sulfide (H2S) as reducing equivalent donor), Chloroflexus (hydrogen (H2) as reducing equivalent donor) - chemolithoheterotrophs obtain energy from the oxidation of inorganic compounds, but cannot fix carbon dioxide (CO2). Examples: some ThiobacilusHydrogenophilaceaeThe Hydrogenophilaceae are a family of Betaproteobacteria, with two genera. Like all Proteobacteria they are Gram-negative. Hydrogenophilus are thermophilic, growing around 50 °C and obtaining their energy from oxidizing hydrogen. It includes the genera Hydrogenophilus and Thiobacillus...

, some BeggiatoaBeggiatoaBeggiatoa is a genus of bacteria in the order Thiotrichales. They are named after the Italian medic and botanist F.S. Beggiato. The organisms live in sulfur-rich environments...

, some NitrobacterNitrobacterNitrobacter is genus of mostly rod-shaped, gram-negative, and chemoautotrophic bacteria.Nitrobacter plays an important role in the nitrogen cycle by oxidizing nitrite into nitrate in soil...

spp., Wolinella (with H2 as reducing equivalent donor), some Knallgas-bacteriaKnallgas-bacteriaHydrogen oxidizing bacteria, or sometimes Knallgas-bacteria, are bacteria which oxidize hydrogen. See microbial metabolism . These bacteria include Hydrogenobacter thermophilus, Hydrogenovibrio marinus, and Helicobacter pylori. There are both Gram positive and Gram negative knallgas bacteria.Most...

, some sulfate-reducing bacteriaSulfate-reducing bacteriaSulfate-reducing bacteria are those bacteria and archaea that can obtain energy by oxidizing organic compounds or molecular hydrogen while reducing sulfate to hydrogen sulfide... - chemoorganoheterotrophs obtain energy, carbon, and reducing equivalents for biosynthetic reactions from organic compounds. Examples: most bacteria, e. g. Escherichia coliEscherichia coliEscherichia coli is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms . Most E. coli strains are harmless, but some serotypes can cause serious food poisoning in humans, and are occasionally responsible for product recalls...

, BacillusBacillusBacillus is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria and a member of the division Firmicutes. Bacillus species can be obligate aerobes or facultative anaerobes, and test positive for the enzyme catalase. Ubiquitous in nature, Bacillus includes both free-living and pathogenic species...

spp., ActinobacteriaActinobacteriaActinobacteria are a group of Gram-positive bacteria with high guanine and cytosine content. They can be terrestrial or aquatic. Actinobacteria is one of the dominant phyla of the bacteria.... - photoorganoheterotrophs obtain energy from light, carbon and reducing equivalents for biosynthetic reactions from organic compounds. Some species are strictly heterotrophic, many others can also fix carbon dioxide and are mixotrophic. Examples: RhodobacterRhodobacterIn taxonomy, Rhodobacter is a genus of the Rhodobacteraceae.The most famous species of Rhodobacter is Rhodobacter sphaeroides, which is commonly used to express proteins.-External links:...

, Rhodopseudomonas, Rhodospirillum, Rhodomicrobium, Rhodocyclus, Heliobacterium, Chloroflexus (alternatively to photolithoautotrophy with hydrogen)

Heterotrophic microbial metabolism

Most microbes are heterotrophic (more precisely chemoorganoheterotrophic), using organic compounds as both carbon and energy sources. Heterotrophic microbes live off of nutrients that they scavenge from living hosts (as commensals or parasites) or find in dead organic matter of all kind (saprophages). Microbial metabolism is the main contribution for the bodily decay of all organisms after death. Many eukaryotic microorganisms are heterotrophic by predationPredation

In ecology, predation describes a biological interaction where a predator feeds on its prey . Predators may or may not kill their prey prior to feeding on them, but the act of predation always results in the death of its prey and the eventual absorption of the prey's tissue through consumption...

or parasitism

Parasitism

Parasitism is a type of symbiotic relationship between organisms of different species where one organism, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the other, the host. Traditionally parasite referred to organisms with lifestages that needed more than one host . These are now called macroparasites...

, properties also found in some bacteria such as Bdellovibrio

Bdellovibrio

Bdellovibrio is a genus of Gram-negative, obligate aerobic bacteria.One of the more notable characteristics of this genus is that members parasitize other Gram-negative bacteria by entering into their periplasmic space and feeding on the biopolymers, e.g. proteins and nucleic acids, of their hosts...

(an intracellular parasite of other bacteria, causing death of its victims) and Myxobacteria such as Myxococcus (predators of other bacteria which are killed and lysed by cooperating swarms of many single cells of Myxobacteria). Most pathogen

Pathogen

A pathogen gignomai "I give birth to") or infectious agent — colloquially, a germ — is a microbe or microorganism such as a virus, bacterium, prion, or fungus that causes disease in its animal or plant host...

ic bacteria can be viewed as heterotrophic parasites of humans or the other eukaryotic species they affect. Heterotrophic microbes are extremely abundant in nature and are responsible for the breakdown of large organic polymer

Polymer

A polymer is a large molecule composed of repeating structural units. These subunits are typically connected by covalent chemical bonds...

s such as cellulose

Cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to over ten thousand β linked D-glucose units....

, chitin

Chitin

Chitin n is a long-chain polymer of a N-acetylglucosamine, a derivative of glucose, and is found in many places throughout the natural world...

or lignin

Lignin

Lignin or lignen is a complex chemical compound most commonly derived from wood, and an integral part of the secondary cell walls of plants and some algae. The term was introduced in 1819 by de Candolle and is derived from the Latin word lignum, meaning wood...

which are generally indigestible to larger animals. Generally, the breakdown of large polymers to carbon dioxide (mineralization

Mineralization

Mineralization may refer to:* Mineralization , the process through which an organic substance becomes impregnated by inorganic substances...

) requires several different organisms, with one breaking down the polymer into its constituent monomers, one able to use the monomers and excreting simpler waste compounds as by-products, and one able to use the excreted wastes. There are many variations on this theme, as different organisms are able to degrade different polymers and secrete different waste products. Some organisms are even able to degrade more recalcitrant compounds such as petroleum compounds or pesticides, making them useful in bioremediation

Bioremediation

Bioremediation is the use of microorganism metabolism to remove pollutants. Technologies can be generally classified as in situ or ex situ. In situ bioremediation involves treating the contaminated material at the site, while ex situ involves the removal of the contaminated material to be treated...

.

Biochemically, prokaryotic heterotrophic metabolism is much more versatile than that of eukaryotic organisms, although many prokaryotes share the most basic metabolic models with eukaryotes, e. g. using glycolysis

Glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose C6H12O6, into pyruvate, CH3COCOO− + H+...

(also called EMP pathway) for sugar metabolism and the citric acid cycle

Citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle — also known as the tricarboxylic acid cycle , the Krebs cycle, or the Szent-Györgyi-Krebs cycle — is a series of chemical reactions which is used by all aerobic living organisms to generate energy through the oxidization of acetate derived from carbohydrates, fats and...

to degrade acetate

Acetate

An acetate is a derivative of acetic acid. This term includes salts and esters, as well as the anion found in solution. Most of the approximately 5 billion kilograms of acetic acid produced annually in industry are used in the production of acetates, which usually take the form of polymers. In...

, producing energy in the form of ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine-5'-triphosphate is a multifunctional nucleoside triphosphate used in cells as a coenzyme. It is often called the "molecular unit of currency" of intracellular energy transfer. ATP transports chemical energy within cells for metabolism...

and reducing power in the form of NADH or quinols. These basic pathways are well conserved because they are also involved in biosynthesis of many conserved building blocks needed for cell growth (sometimes in reverse direction). However, many bacteria

Bacteria

Bacteria are a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria have a wide range of shapes, ranging from spheres to rods and spirals...

and archaea

Archaea

The Archaea are a group of single-celled microorganisms. A single individual or species from this domain is called an archaeon...

utilize alternative metabolic pathways other than glycolysis and the citric acid cycle. A well-studied example is sugar metabolism via the keto-deoxy-phosphogluconate pathway (also called ED pathway) in Pseudomonas

Pseudomonas

Pseudomonas is a genus of gammaproteobacteria, belonging to the family Pseudomonadaceae containing 191 validly described species.Recently, 16S rRNA sequence analysis has redefined the taxonomy of many bacterial species. As a result, the genus Pseudomonas includes strains formerly classified in the...

. Moreover, there is a third alternative sugar-catabolic pathway used by some bacteria, the pentose phosphate pathway

Pentose phosphate pathway

The pentose phosphate pathway is a process that generates NADPH and pentoses . There are two distinct phases in the pathway. The first is the oxidative phase, in which NADPH is generated, and the second is the non-oxidative synthesis of 5-carbon sugars...

. The metabolic diversity and ability of prokaryotes to use a large variety of organic compounds arises from the much deeper evolutionary history and diversity of prokaryotes, as compared to eukaryotes. It is also noteworthy that the mitochondrion

Mitochondrion

In cell biology, a mitochondrion is a membrane-enclosed organelle found in most eukaryotic cells. These organelles range from 0.5 to 1.0 micrometers in diameter...

, the small membrane-bound intracellular organelle that is the site of eukaryotic energy metabolism, arose from the endosymbiosis of a bacterium related to obligate intracellular Rickettsia

Rickettsia

Rickettsia is a genus of non-motile, Gram-negative, non-sporeforming, highly pleomorphic bacteria that can present as cocci , rods or thread-like . Being obligate intracellular parasites, the Rickettsia survival depends on entry, growth, and replication within the cytoplasm of eukaryotic host cells...

, and also to plant-associated Rhizobium

Rhizobium

Rhizobium is a genus of Gram-negative soil bacteria that fix nitrogen. Rhizobium forms an endosymbiotic nitrogen fixing association with roots of legumes and Parasponia....

or Agrobacterium

Agrobacterium

Agrobacterium is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria established by H. J. Conn that uses horizontal gene transfer to cause tumors in plants. Agrobacterium tumefaciens is the most commonly studied species in this genus...

. Therefore it is not surprising that all mitrochondriate eukaryotes share metabolic properties with these Proteobacteria

Proteobacteria

The Proteobacteria are a major group of bacteria. They include a wide variety of pathogens, such as Escherichia, Salmonella, Vibrio, Helicobacter, and many other notable genera....

. Most microbes respire

Cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the set of the metabolic reactions and processes that take place in the cells of organisms to convert biochemical energy from nutrients into adenosine triphosphate , and then release waste products. The reactions involved in respiration are catabolic reactions that involve...

(use an electron transport chain

Electron transport chain

An electron transport chain couples electron transfer between an electron donor and an electron acceptor with the transfer of H+ ions across a membrane. The resulting electrochemical proton gradient is used to generate chemical energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate...

), although oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

is not the only terminal electron acceptor that may be used. As discussed below, the use of terminal electron acceptors other than oxygen has important biogeochemical consequences.

Fermentation

Fermentation is a specific type of heterotrophic metabolism that uses organic carbonOrganic compound

An organic compound is any member of a large class of gaseous, liquid, or solid chemical compounds whose molecules contain carbon. For historical reasons discussed below, a few types of carbon-containing compounds such as carbides, carbonates, simple oxides of carbon, and cyanides, as well as the...

instead of oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor. This means that these organisms do not use an electron transport chain to oxidize NADH to NAD+ and therefore must have an alternative method of using this reducing power and maintaining a supply of NAD+ for the proper functioning of normal metabolic pathways (e.g. glycolysis). As oxygen is not required, fermentative organisms are anaerobic

Anaerobic organism

An anaerobic organism or anaerobe is any organism that does not require oxygen for growth. It could possibly react negatively and may even die if oxygen is present...

. Many organisms can use fermentation under anaerobic conditions and aerobic respiration when oxygen is present. These organisms are facultative anaerobes. To avoid the overproduction of NADH, obligately

Obligate anaerobe

Obligate anaerobes are microorganisms that live and grow in the absence of molecular oxygen; some of these are killed by oxygen. -Metabolism:...

fermentative organisms usually do not have a complete citric acid cycle. Instead of using an ATPase

ATPase

ATPases are a class of enzymes that catalyze the decomposition of adenosine triphosphate into adenosine diphosphate and a free phosphate ion. This dephosphorylation reaction releases energy, which the enzyme harnesses to drive other chemical reactions that would not otherwise occur...

as in respiration

Cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the set of the metabolic reactions and processes that take place in the cells of organisms to convert biochemical energy from nutrients into adenosine triphosphate , and then release waste products. The reactions involved in respiration are catabolic reactions that involve...

, ATP in fermentative organisms is produced by substrate-level phosphorylation

Substrate-level phosphorylation

Substrate-level phosphorylation is a type of metabolism that results in the formation and creation of adenosine triphosphate or guanosine triphosphate by the direct transfer and donation of a phosphoryl group to adenosine diphosphate or guanosine diphosphate from a phosphorylated reactive...

where a phosphate

Phosphate

A phosphate, an inorganic chemical, is a salt of phosphoric acid. In organic chemistry, a phosphate, or organophosphate, is an ester of phosphoric acid. Organic phosphates are important in biochemistry and biogeochemistry or ecology. Inorganic phosphates are mined to obtain phosphorus for use in...

group is transferred from a high-energy organic compound to ADP

Adenosine diphosphate

Adenosine diphosphate, abbreviated ADP, is a nucleoside diphosphate. It is an ester of pyrophosphoric acid with the nucleoside adenosine. ADP consists of the pyrophosphate group, the pentose sugar ribose, and the nucleobase adenine....

to form ATP. As a result of the need to produce high energy phosphate-containing organic compounds (generally in the form of CoA

COA

COA can refer to:*Codename Amscray*Cash on Arrival*Cause of action*CedarOpenAccounts*Center of Attention*Certificate of Appealability*Certificate of Approval for marriage or civil partnership in the United Kingdom*Certificate of Authenticity...

-esters) fermentative organisms use NADH and other cofactor

Cofactor

Cofactor may refer to any of the following:* Cofactor , the signed minor of a matrix* Minor , an alternative name for the determinant of a smaller matrix than that which it describes...

s to produce many different reduced metabolic by-products, often including hydrogen

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with atomic number 1. It is represented by the symbol H. With an average atomic weight of , hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant chemical element, constituting roughly 75% of the Universe's chemical elemental mass. Stars in the main sequence are mainly...

gas (H2). These reduced organic compounds are generally small organic acid

Acid

An acid is a substance which reacts with a base. Commonly, acids can be identified as tasting sour, reacting with metals such as calcium, and bases like sodium carbonate. Aqueous acids have a pH of less than 7, where an acid of lower pH is typically stronger, and turn blue litmus paper red...

s and alcohol

Alcohol

In chemistry, an alcohol is an organic compound in which the hydroxy functional group is bound to a carbon atom. In particular, this carbon center should be saturated, having single bonds to three other atoms....

s derived from pyruvate, the end product of glycolysis

Glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose C6H12O6, into pyruvate, CH3COCOO− + H+...

. Examples include ethanol

Ethanol

Ethanol, also called ethyl alcohol, pure alcohol, grain alcohol, or drinking alcohol, is a volatile, flammable, colorless liquid. It is a psychoactive drug and one of the oldest recreational drugs. Best known as the type of alcohol found in alcoholic beverages, it is also used in thermometers, as a...

, acetate

Acetate

An acetate is a derivative of acetic acid. This term includes salts and esters, as well as the anion found in solution. Most of the approximately 5 billion kilograms of acetic acid produced annually in industry are used in the production of acetates, which usually take the form of polymers. In...

, lactate

Lactic acid

Lactic acid, also known as milk acid, is a chemical compound that plays a role in various biochemical processes and was first isolated in 1780 by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. Lactic acid is a carboxylic acid with the chemical formula C3H6O3...

, and butyrate

Butyrate

Butyrate is the traditional name for the conjugate base of butanoic acid . The formula of the butanoate ion is C4H7O2-. The archaic name is used as part of the name of butyrates or butanoates, or esters and salts of butyric acid, a short chain fatty acid...

. Fermentative organisms are very important industrially and are used to make many different types of food products. The different metabolic end products produced by each specific bacterial species are responsible for the different tastes and properties of each food.

Not all fermentative organisms use substrate-level phosphorylation

Phosphorylation

Phosphorylation is the addition of a phosphate group to a protein or other organic molecule. Phosphorylation activates or deactivates many protein enzymes....

. Instead, some organisms are able to couple the oxidation of low-energy organic compounds directly to the formation of a proton (or sodium) motive force and therefore ATP synthesis. Examples of these unusual forms of fermentation include succinate fermentation by Propionigenium modestum and oxalate

Oxalate

Oxalate , is the dianion with formula C2O42− also written 22−. Either name is often used for derivatives, such as disodium oxalate, 2C2O42−, or an ester of oxalic acid Oxalate (IUPAC: ethanedioate), is the dianion with formula C2O42− also written (COO)22−. Either...

fermentation by Oxalobacter formigenes

Oxalobacter formigenes

Oxalobacter formigenes is an oxalate-degrading anaerobic bacterium that colonizes the large intestine of numerous vertebrates, including humans. O. formigenes and humans share a beneficial symbiosis....

. These reactions are extremely low-energy yielding. Humans and other higher animals also use fermentation to produce lactate

Lactate

Lactate may refer to:*The act of lactation*The conjugate base of lactic acid...

from excess NADH, although this is not the major form of metabolism as it is in fermentative microorganisms.

Methylotrophy

Methylotrophy refers to the ability of an organism to use C1-compounds as energy sources. These compounds include methanolMethanol

Methanol, also known as methyl alcohol, wood alcohol, wood naphtha or wood spirits, is a chemical with the formula CH3OH . It is the simplest alcohol, and is a light, volatile, colorless, flammable liquid with a distinctive odor very similar to, but slightly sweeter than, ethanol...

, methyl amines, formaldehyde

Formaldehyde

Formaldehyde is an organic compound with the formula CH2O. It is the simplest aldehyde, hence its systematic name methanal.Formaldehyde is a colorless gas with a characteristic pungent odor. It is an important precursor to many other chemical compounds, especially for polymers...

, and formate

Formate

Formate or methanoate is the ion CHOO− or HCOO− . It is the simplest carboxylate anion. It is produced in large amounts in the hepatic mitochondria of embryonic cells and in cancer cells by the folate cycle Formate or methanoate is the ion CHOO− or HCOO− (formic acid minus one hydrogen ion). It...

. Several other less common substrates may also be used for metabolism, all of which lack carbon-carbon bonds. Examples of methylotrophs include the bacteria Methylomonas

Methylomonas

The Methylomonas are a genus of bacteria that obtain their carbon and energy from methane, a metabolic process called methanotrophy....

and Methylobacter. Methanotroph

Methanotroph

Methanotrophs are bacteria that are able to metabolize methane as their only source of carbon and energy. They can grow aerobically or anaerobically and require single-carbon compounds to survive...

s are a specific type of methylotroph that are also able to use methane

Methane

Methane is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is the simplest alkane, the principal component of natural gas, and probably the most abundant organic compound on earth. The relative abundance of methane makes it an attractive fuel...

(CH4) as a carbon source by oxidizing it sequentially to methanol (CH3OH), formaldehyde (CH2O), formate (HCOO-), and carbon dioxide CO2 initially using the enzyme methane monooxygenase

Methane monooxygenase

Methane monooxygenase, or MMO, is an enzyme capable of oxidizing the C-H bond in methane as well as other alkanes. Methane monooxygenase belongs to the class of oxidoreductase enzymes ....

. As oxygen is required for this process, all (conventional) methanotrophs are obligate aerobe

Obligate aerobe

An obligate aerobe is an aerobic organism that requires oxygen to grow. Through cellular respiration, these organisms use oxygen to oxidize substances, like sugars or fats, in order to obtain energy. During respiration, they use oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor...

s. Reducing power in the form of quinone

Quinone

A quinone is a class of organic compounds that are formally "derived from aromatic compounds [such as benzene or naphthalene] by conversion of an even number of –CH= groups into –C– groups with any necessary rearrangement of double bonds," resulting in "a fully conjugated cyclic dione structure."...

s and NADH is produced during these oxidations to produce a proton motive force and therefore ATP generation. Methylotrophs and methanotrophs are not considered as autotrophic, because they are able to incorporate some of the oxidized methane (or other metabolites) into cellular carbon before it is completely oxidized to CO2 (at the level of formaldehyde), using either the serine pathway (Methylosinus, Methylocystis) or the ribulose monophosphate pathway (Methylococcus), depending on the species of methylotroph.

In addition to aerobic methylotrophy, methane can also be oxidized anaerobically. This occurs by a consortium of sulfate-reducing bacteria and relatives of methanogen

Methanogen

Methanogens are microorganisms that produce methane as a metabolic byproduct in anoxic conditions. They are classified as archaea, a group quite distinct from bacteria...

ic Archaea

Archaea

The Archaea are a group of single-celled microorganisms. A single individual or species from this domain is called an archaeon...

working syntrophically (see below). Little is currently known about the biochemistry and ecology of this process.

Methanogenesis

Methanogenesis

Methanogenesis or biomethanation is the formation of methane by microbes known as methanogens. Organisms capable of producing methane have been identified only from the domain Archaea, a group phylogenetically distinct from both eukaryotes and bacteria, although many live in close association with...

is the biological production of methane. It is carried out by methanogens, strictly anaerobic

Anaerobic organism

An anaerobic organism or anaerobe is any organism that does not require oxygen for growth. It could possibly react negatively and may even die if oxygen is present...

Archaea such as Methanococcus

Methanococcus

In taxonomy, Methanococcus is a genus of the Methanococcaceae.Methanococcus is a genus of coccoid methanogens. They are all mesophiles, except the thermophilic M. thermolithotrophicus and the hyperthermophilic M. jannaschii...

, Methanocaldococcus

Methanocaldococcus

In taxonomy, Methanocaldococcus is a genus of the Methanocaldococcaceae.Methanocaldococcus formerly known as Methanococcus is a genus of coccoid methanogens. They are all mesophiles, except the thermophilic M. thermolithotrophicus and the hyperthermophilic M. jannaschii...

, Methanobacterium

Methanobacterium

In taxonomy, Methanobacterium is a genus of the Methanobacteriaceae.- External links :...

,

Methanothermus

Methanothermus

In taxonomy, Methanothermus is a genus of the Methanothermaceae.-External links:...

, Methanosarcina

Methanosarcina

Methanosarcina are the only known anaerobic methanogens to produce methane using all three known metabolic pathways for methanogenesis. Most methanogens make methane from carbon dioxide and hydrogen gas. Some others utilize acetate in the acetoclastic pathway...

, Methanosaeta

Methanosaeta

In taxonomy, Methanosaeta is a genus of the Methanosaetaceae.-External links:...

and Methanopyrus

Methanopyrus

In taxonomy, Methanopyrus is a genus of the Methanopyraceae.Methanopyrus is a genus of methanogen, with a single described species, M. kandleri. It is a hyperthermophile, discovered on the wall of a black smoker from the Gulf of California at a depth of 2000 m, at temperatures of 84-110 °C...

. The biochemistry of methanogenesis is unique in nature in its use of a number of unusual cofactor

Cofactor (biochemistry)

A cofactor is a non-protein chemical compound that is bound to a protein and is required for the protein's biological activity. These proteins are commonly enzymes, and cofactors can be considered "helper molecules" that assist in biochemical transformations....

s to sequentially reduce methanogenic substrates to methane, such as coenzyme M

Coenzyme M

Coenzyme M is a coenzyme required for methyl-transfer reactions in the metabolism of methanogens. The coenzyme is an anion with the formula . It is named 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate and abbreviated HS–CoM. The cation is unimportant, but the sodium salt is most available...

and methanofuran

Methanofuran

Methanofuran describes a family of chemical compounds found in methanogenic archaea. These species feature a 2-aminomethylfuran linked to phenoxy group...

. These cofactors are responsible (among other things) for the establishment of a proton

Proton

The proton is a subatomic particle with the symbol or and a positive electric charge of 1 elementary charge. One or more protons are present in the nucleus of each atom, along with neutrons. The number of protons in each atom is its atomic number....

gradient across the outer membrane thereby driving ATP synthesis. Several types of methanogenesis occur, differing in the starting compounds oxidized. Some methanogens reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) to methane (CH4) using electrons (most often) from hydrogen gas (H2) chemolithoautotrophically. These methanogens can often be found in environments containing fermentative organisms. The tight association of methanogens and fermentative bacteria can be considered to be syntrophic (see below) because the methanogens, which rely on the fermentors for hydrogen, relieve feedback inhibition of the fermentors by the build-up of excess hydrogen that would otherwise inhibit their growth. This type of syntrophic relationship is specifically known as interspecies hydrogen transfer. A second group of methanogens use methanol (CH3OH) as a substrate for methanogenesis. These are chemoorganotrophic, but still autotrophic in using CO2 as only carbon source. The biochemistry of this process is quite different from that of the carbon dioxide-reducing methanogens. Lastly, a third group of methanogens produce both methane and carbon dioxide from acetate

Acetate

An acetate is a derivative of acetic acid. This term includes salts and esters, as well as the anion found in solution. Most of the approximately 5 billion kilograms of acetic acid produced annually in industry are used in the production of acetates, which usually take the form of polymers. In...

(CH3COO-) with the acetate being split between the two carbons. These acetate-cleaving organisms are the only chemoorganoheterotrophic methanogens. All autotrophic methanogens use a variation of the acetyl-CoA pathway to fix CO2 and obtain cellular carbon.

Syntrophy

Syntrophy, in the context of microbial metabolism, refers to the pairing of multiple species to achieve a chemical reactionChemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Chemical reactions can be either spontaneous, requiring no input of energy, or non-spontaneous, typically following the input of some type of energy, such as heat, light or electricity...

that, on its own, would be energetically unfavorable. The best studied example of this process is the oxidation of fermentative end products (such as acetate, ethanol

Ethanol

Ethanol, also called ethyl alcohol, pure alcohol, grain alcohol, or drinking alcohol, is a volatile, flammable, colorless liquid. It is a psychoactive drug and one of the oldest recreational drugs. Best known as the type of alcohol found in alcoholic beverages, it is also used in thermometers, as a...

and butyrate

Butyrate

Butyrate is the traditional name for the conjugate base of butanoic acid . The formula of the butanoate ion is C4H7O2-. The archaic name is used as part of the name of butyrates or butanoates, or esters and salts of butyric acid, a short chain fatty acid...

) by organisms such as Syntrophomonas. Alone, the oxidation of butyrate to acetate and hydrogen gas is energetically unfavorable. However, when a hydrogenotrophic (hydrogen-using) methanogen is present the use of the hydrogen gas will significantly lower the concentration of hydrogen (down to 10−5 atm) and thereby shift the equilibrium

Chemical equilibrium

In a chemical reaction, chemical equilibrium is the state in which the concentrations of the reactants and products have not yet changed with time. It occurs only in reversible reactions, and not in irreversible reactions. Usually, this state results when the forward reaction proceeds at the same...

of the butyrate oxidation reaction under standard conditions (ΔGº’) to non-standard conditions (ΔG’). Because the concentration of one product is lowered, the reaction is "pulled" towards the products and shifted towards net energetically favorable conditions (for butyrate oxidation: ΔGº’= +48.2 kJ/mol, but ΔG' = -8.9 kJ/mol at 10−5 atm hydrogen and even lower if also the initially produced acetate is further metabolized by methanogens). Conversely, the available free energy from methanogenesis is lowered from ΔGº’= -131 kJ/mol under standard conditions to ΔG' = -17 kJ/mol at 10−5 atm hydrogen. This is an example of intraspecies hydrogen transfer. In this way, low energy-yielding carbon sources can be used by a consortium of organisms to achieve further degradation and eventual mineralization

Mineralization

Mineralization may refer to:* Mineralization , the process through which an organic substance becomes impregnated by inorganic substances...

of these compounds. These reactions help prevent the excess sequestration of carbon over geologic time scales, releasing it back to the biosphere in usable forms such as methane and CO2.

Anaerobic respiration

While aerobic organismAerobic organism

An aerobic organism or aerobe is an organism that can survive and grow in an oxygenated environment.Faculitative anaerobes grow and survive in an oxygenated environment and so do aerotolerant anaerobes.-Glucose:...

s during respiration use oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor, anaerobic organism

Anaerobic organism

An anaerobic organism or anaerobe is any organism that does not require oxygen for growth. It could possibly react negatively and may even die if oxygen is present...

s use other electron acceptors. These inorganic compounds have a lower reduction potential than oxygen, meaning that respiration

Cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the set of the metabolic reactions and processes that take place in the cells of organisms to convert biochemical energy from nutrients into adenosine triphosphate , and then release waste products. The reactions involved in respiration are catabolic reactions that involve...

is less efficient in these organisms and leads to slower growth rates than aerobes. Many facultative anaerobes can use either oxygen or alternative terminal electron acceptors for respiration depending on the environmental conditions.

Most respiring anaerobes are heterotrophs, although some do live autotrophically. All of the processes described below are dissimilative, meaning that they are used during energy production and not to provide nutrients for the cell (assimilative). Assimilative pathways for many forms of anaerobic respiration

Anaerobic respiration

Anaerobic respiration is a form of respiration using electron acceptors other than oxygen. Although oxygen is not used as the final electron acceptor, the process still uses a respiratory electron transport chain; it is respiration without oxygen...

are also known.

Denitrification - nitrate as electron acceptor

Denitrification is the utilization of nitrateNitrate

The nitrate ion is a polyatomic ion with the molecular formula NO and a molecular mass of 62.0049 g/mol. It is the conjugate base of nitric acid, consisting of one central nitrogen atom surrounded by three identically-bonded oxygen atoms in a trigonal planar arrangement. The nitrate ion carries a...

(NO3-) as a terminal electron acceptor. It is a widespread process that is used by many members of the Proteobacteria. Many facultative anaerobes use denitrification because nitrate, like oxygen, has a high reduction potential. Many denitrifying bacteria can also use ferric iron

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

(Fe3+) and some organic electron acceptor

Electron acceptor

An electron acceptor is a chemical entity that accepts electrons transferred to it from another compound. It is an oxidizing agent that, by virtue of its accepting electrons, is itself reduced in the process....

s. Denitrification involves the stepwise reduction of nitrate to nitrite

Nitrite

The nitrite ion has the chemical formula NO2−. The anion is symmetric with equal N-O bond lengths and a O-N-O bond angle of ca. 120°. On protonation the unstable weak acid nitrous acid is produced. Nitrite can be oxidised or reduced, with product somewhat dependent on the oxidizing/reducing agent...

(NO2-), nitric oxide

Nitric oxide

Nitric oxide, also known as nitrogen monoxide, is a diatomic molecule with chemical formula NO. It is a free radical and is an important intermediate in the chemical industry...

(NO), nitrous oxide

Nitrous oxide

Nitrous oxide, commonly known as laughing gas or sweet air, is a chemical compound with the formula . It is an oxide of nitrogen. At room temperature, it is a colorless non-flammable gas, with a slightly sweet odor and taste. It is used in surgery and dentistry for its anesthetic and analgesic...

(N2O), and dinitrogen (N2) by the enzymes nitrate reductase

Nitrate reductase

Nitrate reductases are molybdoenzymes that reduce nitrate to nitrite .* Eukaryotic nitrate reductases are part of the sulfite oxidase family of molybdoenzymes....

, nitrite reductase

Nitrite reductase

Nitrite reductase refers to any of several classes of enzymes that catalyze the reduction of nitrite. There are two classes of NIR's. A multi haem enzyme reduces NO2 to a variety of products. Copper containing enzymes carry out a single electron transfer to produce nitric oxide.- Iron based...

, nitric oxide reductase, and nitrous oxide reductase, respectively. Protons are transported across the membrane by the initial NADH reductase, quinones, and nitrous oxide reductase to produce the electrochemical gradient critical for respiration. Some organisms (e.g. E. coli) only produce nitrate reductase and therefore can accomplish only the first reduction leading to the accumulation of nitrite. Others (e.g. Paracoccus denitrificans

Paracoccus denitrificans

Paracoccus denitrificans, is a coccoid bacterium known for its nitrate reducing properties, its ability to replicate under conditions of hypergravity and for being the possible ancestor of the eukaryotic mitochondrion .-Description:...

or Pseudomonas stutzeri

Pseudomonas stutzeri

Pseudomonas stutzeri is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped, motile, single polar-flagellated, soil bacterium first isolated from human spinal fluid.. It is a denitrifying bacterium, and strain KC of P. stutzeri may be used for bioremediation as it is able to degrade carbon tetrachloride. It is also an...

) reduce nitrate completely. Complete denitrification is an environmentally significant process because some intermediates of denitrification (nitric oxide and nitrous oxide) are important greenhouse gas

Greenhouse gas

A greenhouse gas is a gas in an atmosphere that absorbs and emits radiation within the thermal infrared range. This process is the fundamental cause of the greenhouse effect. The primary greenhouse gases in the Earth's atmosphere are water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone...

es that react with sunlight

Sunlight

Sunlight, in the broad sense, is the total frequency spectrum of electromagnetic radiation given off by the Sun. On Earth, sunlight is filtered through the Earth's atmosphere, and solar radiation is obvious as daylight when the Sun is above the horizon.When the direct solar radiation is not blocked...

and ozone

Ozone

Ozone , or trioxygen, is a triatomic molecule, consisting of three oxygen atoms. It is an allotrope of oxygen that is much less stable than the diatomic allotrope...

to produce nitric acid, a component of acid rain

Acid rain

Acid rain is a rain or any other form of precipitation that is unusually acidic, meaning that it possesses elevated levels of hydrogen ions . It can have harmful effects on plants, aquatic animals, and infrastructure. Acid rain is caused by emissions of carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen...

. Denitrification is also important in biological wastewater treatment

Wastewater Treatment

Wastewater treatment may refer to:* Sewage treatment* Industrial wastewater treatment...

where it is used to reduce the amount of nitrogen released into the environment thereby reducing eutrophication

Eutrophication

Eutrophication or more precisely hypertrophication, is the movement of a body of water′s trophic status in the direction of increasing plant biomass, by the addition of artificial or natural substances, such as nitrates and phosphates, through fertilizers or sewage, to an aquatic system...

.

Sulfate reduction - sulfate as electron acceptor

SulfateSulfate

In inorganic chemistry, a sulfate is a salt of sulfuric acid.-Chemical properties:...

reduction is a relatively energetically poor process used by many Gram negative bacteria found within the δ-Proteobacteria, Gram-positive organisms relating to Desulfotomaculum

Desulfotomaculum

Desulfotomaculum is a genus of Gram-positive, obligately anaerobic soil bacteria. A type of sulfate-reducing bacteria, Desulfotomaculum can cause food spoilage in poorly processed canned foods . Their presence can be identified by the release of hydrogen sulfide gas with its rotten egg smell when...

or the archaeon Archaeoglobus

Archaeoglobus

Archaeoglobus is a genus of the phylum Euryarchaeota. Archaeoglobus can be found in high-temperature oil fields where they may contribute to oil field souring.- Metabolism :...

. Hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless, very poisonous, flammable gas with the characteristic foul odor of expired eggs perceptible at concentrations as low as 0.00047 parts per million...

(H2S) is produced as a metabolic end product. For sulfate reduction electron donors and energy are needed.

Electron donors

Many sulfate reducers are heterotrophic, using carbon compounds such as lactate and pyruvate (among many others) as electron donorElectron donor

An electron donor is a chemical entity that donates electrons to another compound. It is a reducing agent that, by virtue of its donating electrons, is itself oxidized in the process....

s, while others are autotrophic, using hydrogen gas (H2) as an electron donor. Some unusual autotrophic sulfate-reducing bacteria (e.g. Desulfotignum phosphitoxidans

Desulfobacteraceae

The Desulfobacteraceae are a family of Proteobacteria. They are reducing sulfates to sulfides to obtain energy and are strictly anaerobe.-References:Garrity, George M.; Brenner, Don J.; Krieg, Noel R.; Staley, James T....

) can use phosphite

Phosphite