Manfred Clynes

Encyclopedia

Manfred Clynes is a scientist, inventor, and musician. He is best known for his innovations and discoveries in the interpretation of music, and for his contributions to the study of biological systems and neurophysiology

.

and neuroscience

. Clynes' musical achievements embrace performance and interpretation, exploring and clarifying the function of time forms in the expression of music—and of emotions generally—in connection with brain

function in its electrical manifestations. As a concert pianist

, he has recorded outstanding versions of Bach

’s Goldberg Variations

and of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations

. As an inventor, his inventions (about 40 patents) include, besides the CAT computer

for electrical brain

research, the online auto- and cross-correlator, and inventions in the field of ultrasound

(Clynes invented color ultrasound.) as well as telemetering, data recording, and wind energy

. The creative process of computer realizations of classical music

with SuperConductor is based on his discoveries of fundamental principles of musicality. Clynes was the subject of a front page article in the Wall Street Journal, Sept. 21 1991.

with basic expressive time forms, and on the innate power of those forms to generate specific basic emotions. He recognized that we are all familiar with this interlocking in our experiences of laughter

and of yawning, although its scientific importance had been largely swept under the carpet by a Skinner

ian bias and still largely is. According to Clynes’s experimental research these time forms (“sentic forms”), as embodied in the central nervous system

, are primary to the varied modes in which they find expression, such as sound, touch, and gesture. Clynes was able to prove this by systematically deriving sounds from subjects’ expressions of emotions through touch, and then playing those sounds to hearers culturally remote from the original subjects. In one trial, for example, Aborigines

in Central Australia

were able to correctly identify the specific emotional qualities of sounds derived from the touch of white urban Americans. (This experiment was featured on Nova, What Is Music? in 1988). Clynes found in this a confirmation of the existence of biologically fixed, universal, primary dynamic forms that determine expressions of emotion that give rise to much of the experience within human societies.

Some of these dynamic forms appear to be shared by those animals that have time consciousnesses at a similar rate to humans; hence the intuition of pet owners that their dog or cat understands tone of voice and the emotional form of touch. Anger, love, and grief, for example, according to Clynes, have clearly different dynamic expressive forms. Importantly, a cardinal property of this inherent biologic communication language, in Clynes’ findings, is that the more closely an expression follows the precise dynamic form, the more powerful is the generation of the corresponding emotion, in both the person expressing and in the perceiver of the expression. Hence, presumably, such phenomena as charisma (in persons whose performance of emotional expressions closely follows the universal form). His experience with Pablo Casals

confirmed for Clynes the importance of this faithfulness to the natural dynamic form in generating emotionally significant meaning in musical performance.

, and, to some degree, tobacco and alcohol addictions

, as a result of repeated application of this process. Thousands of people have by now experienced sentic cycles, some for years, some even decades. In the 1980s especially, Clynes taught various groups to conduct Sentic Cycles on their own. Nowadays, the Sentic Cycle kit is available on the Internet.

Early work developing sentic cycles in the 1970s had convinced Clynes also that it is easy with it for most people to proceed from experiencing one emotion to another quite rapidly. After three or four minutes of one emotion, a person tended to be being satiated with the current emotion. The ready switching to the next emotion with quite fresh experience pointed to the existence of specific receptors in the brain, he suggested, that become satiated with particular neurohormones; this was later confirmed by the identification of a number of such receptors.

This finding links well with the historic tendency of composers to vary emotions every 4 minutes or so in their compositions. The human need for variety is based on brain receptor properties. As anyone who has seen more than three Charlie Chaplin

movies in a row can testify, laughter

, too, palls after prolonged exposure, and it seems to be for the same reason.

Clynes also studied laughter, "nature's arrow from appearance to reality". In (nonderisive) laughter, according to Clynes, a small element of disorder is suddenly understood to be only apparently disordered, within an actual, larger, order. He then predicted the existence of soundless laughter, in which the sound production is replaced by tactile pressure at the same temporal pattern. In studies at UCSD the mean repetitions of the “ha's” was found to be approximately 5.18 per second. Clynes further hypothesized that couples with unmatched speeds of laughter might not be as readily compatible as those whose laughter was harmoniously coordinated.

Clynes enthusiastically published his realization that love, joy, and reverence were always there to be experienced, capable of being generated through precise expression and accessible by simple means, due to the connection to their biologic roots. Music had always been a special means for this, but now, with this touch artform, it was universally accessible. By this means, even negative emotions, such as grief anger, could be enjoyed in a compassionate non-destructive framework.

In the '70s and in the '80s Clynes had started to write poems, a few of which had found their way into his book Sentics. Later, Marvin Minsky

quoted from them in his book The Society of Mind. In the late 1980s and in the 1990s he wrote his 12 Animal Poems. Boundaries of Compassion is a substantial set of poems growing out of his experience in Germany

while doing experimental work at the Luedenscheid hospital in the summer of 1985, poems in regard to what Germans call “the Jewish Question

.”

Austria

. His family emigrated to Melbourne

, Australia

, in September 1938 to escape the Nazis. In Australia, at fifteen, in his last year at high school, having newly learned calculus

, he invented the inertial guidance method for aircraft using piezoelectric crystals and repeated electronic

integration, but Australian authorities denied that it would work. In fact, the same system Clynes had invented was later used with great success, during the last part of the Second World War. The detailed descriptions of this invention as written by the fifteen-year-old Clynes are rigorous; it was the first of his many inventions to come that worked. (Clynes' earlier attempt, at the age of thirteen, to create a perpetual motion

device was naturally a failure). In 1946 Clynes graduated from the University of Melbourne

having studied both engineering

science and music. His musical talent was recognized by a series of awards, concerto

performances and prizes, one of which provided a three-year graduate fellowship to the Juilliard School of Music. At Juilliard, he was a piano student of Olga Samaroff

and Sascha Gorodnitzki

.

He received his MS

degree from Juilliard in 1949, after having performed Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 1 at the Tanglewood Music Festival

(in 1948) then under the direction of Serge Koussevitzky

in a performance of which the pianist Gerson Yessin, who was present, recently recalled as "monumental." [Yessin: "Manfred played beautifully, outstandingly."]

After graduating from Juilliard (It gave no doctorates then), Clynes retreated to a small log cabin at six thousand feet altitude in the solitude of Wrightwood, California

. There he learned Bach's Goldberg Variations

and other works. He performed them for the first time in October 1949, in Ojai, at J. Krishnamurti's school, and, in 1950, along with other works, in all the capital cities of Australia, to great acclaim. He soon became regarded as one of Australia's outstanding pianists.

In 1952 he was invited to Princeton University

as a graduate student in the Music Department, and issued a green card, to pursue his studies in the Psychology of Music, with a Fulbright and Smith-Mundt Award. There he became aware of the work of G. Becking, who in 1928 had published a sensitive, if nonscientific, study of distinctive motor patterns associated in following the music of individual composers. It was this work that led, in the late 1960s, to Clynes' scientific sentographic studies of what he termed composers' pulses, as their motor manifestation, in which Pablo Casals

and Rudolf Serkin

were to be his first subjects.

Young Clynes had a personal letter of introduction to Albert Einstein

from an elderly lady in Australia, with whom, in her youth, Einstein had exchanged poems. Soon Einstein invited him repeatedly to dinner at his home, and a friendship sprang up between the two men. (See details Michelmore’s Life of Einstein.) Clynes played for Einstein on his fine Bechstein piano, especially Beethoven, Mozart and Schubert. He loved Clynes’ Mozart and Schubert, calling Clynes “a blessed artist” (Ein begnadeter Künstler) In May 1953 Einstein wrote Clynes a personal letter by hand to help him in his forthcoming European tour.

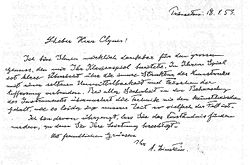

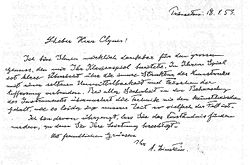

(Translation of Einstein's letter, dated Princeton, 18 May 1953: "Dear Mr. Clynes, I am truly grateful to you for the great enjoyment that your piano playing has given me. Your performance combines a clear insight into the inner structure of the work of art with a rare spontaneity and freshness of conception. With all the secure mastery of your instrument, your technique never supplants the artistic content, as unfortunately so often is the case in our time. I am convinced that you will find the appreciation to which your achievement entitles you. With friendly greetings yours, A. Einstein.")

(Translation of Einstein's letter, dated Princeton, 18 May 1953: "Dear Mr. Clynes, I am truly grateful to you for the great enjoyment that your piano playing has given me. Your performance combines a clear insight into the inner structure of the work of art with a rare spontaneity and freshness of conception. With all the secure mastery of your instrument, your technique never supplants the artistic content, as unfortunately so often is the case in our time. I am convinced that you will find the appreciation to which your achievement entitles you. With friendly greetings yours, A. Einstein.")

. The tour ended with a solo concert before an audience of 2500 at London's Royal Festival Hall

, which had just been built.

, a device about which, at the time, both he and his interviewer were ignorant. In short shrift, however, Clynes mastered that computer, and then within a year created a new analytic method of stabilizing dynamical system

s, which he published as a paper in the IEEE Transactions.

Bogue, the company he was working for, doubled his salary, after a year, unasked. "Only in America!" was Clynes' reaction. (He became a citizen in 1960.)

In 1955, at Clynes' suggestion, Bogue employed his father, then aged 72, from Australia

, as a naval architect

; the elder Clynes had not been permitted to work in his profession in Australia, because he was not British-born. For a time Clynes father and son went to work together every morning (to Clynes’ rejoicing).

As the result of a chance meeting, in 1956, Dr Nathan S. Kline

, Director of the Research Center of Rockland State Hospital, a large mental hospital, offered Clynes a substantial research job at the Center, where he in 1956 became ‘Chief Research Scientist’. Kline was to become the recipient of two Lasker Awards, and had built up that research center to formidable renown. (It is now called the Nathan S. Kline Psychiatric Center.)

(Computer of Average Transients) a $10,000 portable computer permitting the extraction of responses from ongoing electric activity—the needle in the haystack. The CAT quickly came into use in research labs all over the world, marketed by Technical Measurements Corp., advancing the study of the electric activity of the brain (enabling, for example, the clinical detection of deafness in newborns). In this way, Clynes made his fortune by age 37.

Also in 1960, he discovered a biologic law, "Unidirectional Rate Sensitivity," the subject, in 1967, of a two-day symposium held by the New York Academy of Science. This law, related to biologic communication channels of control and information

Also in 1960, he discovered a biologic law, "Unidirectional Rate Sensitivity," the subject, in 1967, of a two-day symposium held by the New York Academy of Science. This law, related to biologic communication channels of control and information

, is basically the consequence of the fact, realized by Clynes, that molecules can only arrive in positive numbers, unlike engineering electric signals, which can be positive or negative. This fact imposes radical limitations on the methods of control that biology

can use. It cannot, for example, simply cancel a signal by sending a signal of opposite polarity, since there is no simple opposite polarity. To cancel, a second channel involving other, different molecules (chemicals) is required. This law explains, among other things, why the sensations of hot and cold need to operate through two separate sensing channels in the body, why we do not actively sense the disappearance of a smell, and why we continue to feel shocked after a near-miss accident. Also in 1960, in collaboration with Nathan S. Kline

Also in 1960, in collaboration with Nathan S. Kline

, Clynes published the cyborg

concept, and its corollary, participant evolution. "Cyborg

" became a household word and was misapplied, much to the dismay of Clynes, in films such as Terminator

. Cyborgology is now a field taught at numerous universities. In 1964 the University of Melbourne

awarded Clynes the degree of D.Sc, a degree superior to Ph. D and rarely given by British universities.

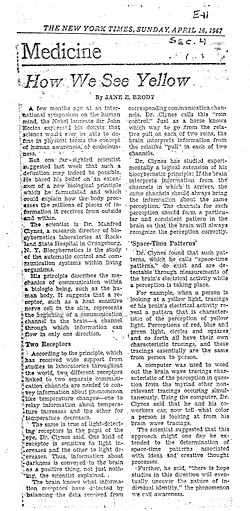

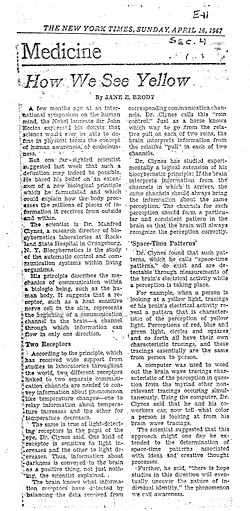

Already in 1960 The New York Times had noted Clynes' remarkable double-stranded gifts. In 1965 he began to give concerts in his newly acquired large mansion on the Hudson, which had a real pipe organ in the living room, and 5 acres (20,234.3 m²) of park-like grounds. Now, with the financial success consequent to his scientific innovations, it became possible for Clynes to return to music. An ardent admirer of the great master musician Pablo Casals

Already in 1960 The New York Times had noted Clynes' remarkable double-stranded gifts. In 1965 he began to give concerts in his newly acquired large mansion on the Hudson, which had a real pipe organ in the living room, and 5 acres (20,234.3 m²) of park-like grounds. Now, with the financial success consequent to his scientific innovations, it became possible for Clynes to return to music. An ardent admirer of the great master musician Pablo Casals

since early childhood, Clynes now attended all Casals' master classes, many with his family.

In 1966, Clynes played both the Diabelli Variations

of Beethoven and Bach

's Goldberg Variations

for Casals, and was invited to join Casals in Puerto Rico

for several months to take part in his music and to accompany some of the master classes at the Casals home in Santurce. Clynes considered this contact with Casals to be a fulfilment of his most cherished lifelong dream. Casals exceeded his expectations in every way, and Clynes considered his friendship with Casals to have been the highpoint of his life. As no one else, Casals had, by Clynes' estimation an immediate contact with the profound in music. After his return to New York City

, Clynes performed Beethoven's Fourth Piano Concerto and also gave several concerts at his mansion for invited audiences that included Erich Fromm

.

electrical responses to the color red from previous black produced similar patterns from several distinct brain sites, for all subjects. Other colors produced their own distinct patterns. These results from 1965 went a long way to help dispel the Skinnerian

notion of tabula rasa. By 1968 he was able to show that it was possible to distinguish which of 100 different objects a person was looking at from his electrical brain

responses alone, with repeated presentations. In other experiments in 1969 he described what he called the R-M function (from Rest to Motion) detectable at the apex of the brain for various modalities of stimulation, showing how two sets of unidirectionally rate sensitive (URS) channels in series could produce an effect corresponding to the mental concepts Rest and Motion.

What could three URS channel sets do in combination? He never found out.

But here were the beginnings of the embodiments of mental concepts in a wordless manner—a way of representing intuitive concepts to the brain

wordlessly.

device.

He turned first to the question of the characteristic pulse in the music of various composers, which had been on his mind since his Princeton years. In 1967 Clynes designed an instrument he called the sentograph to measure the motoric pulse. The experiments required outstanding musicians to "conduct" music on a pressure-sensitive finger rest, as they were thinking the music without sound. Rudolf Serkin

and Pablo Casals

were his first subjects.

Soon it became apparent that the ‘pulse shapes’ for Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and Mendelssohn

were consistently different from each another, but similar across their different pieces (when normalized according to selection of similar tempo).

Encouraged by these positive findings relating outputs to specific inner states of the brain, first presented at a Smithsonian Conference in 1968 at Santa Inez, Clynes then proceeded to measure the expressive form of specific emotions in a similar way, by having subjects generate them by repeatedly expressing them on the finger rest, thus finding specific signatures for the emotions, which he called sentic forms. As in the case of composers' pulses, the form associated with each emotion consistently appeared for that emotion and was distinct from the forms of other emotions.

In 1972 Clynes, whose work had long been supported by NIH Grants, received a grant from the Wenner Gren Foundation in Sweden

, allowing him to collect data in Central Mexico

, Japan

, and Bali

, using the sentograph to investigate emotional expression cross-culturally. Though considerably more limited in scope than the nature of that inquiry would demand, the data were largely confirmatory of Clynes' theories of universal biologically determined time forms for each emotion. At the invitation of the NY Academy of Sciences, Clynes wrote an extensive monograph on his findings and theories to date, which the Academy published in 1973.

That same year he accepted a visiting professorship in the music department of the University of California at San Diego, where he completed his book Sentics, the Touch of Emotion, which he had begun in 1972. In it he summarized the theories and findings on sentics, and outlined hopes for the future that his work contained. In 1970 and 1971, the American Association for the Advancement of Science

held two symposia on Sentics.

Since the sentic cycles suddenly helped individuals feel better without drugs, Clynes' work was now deemed contrary to the line of research sponsored at the Rockland State Research Center, headed by Nathan Kline, whose supporters were the major drug companies. As a result, Clynes was unable to continue the work at that facility. In his new environment, there was no laboratory in which to amass new data. Although dismissed by the NY Times, Sentics was lauded extravagantly in other publications. (The book is considered a classic today). It was read in manuscript with great approval and excitement by several authorities: Yehudi Menuhin volunteered a foreword, itself a remarkable document, welcoming Clynes "as a brother." Rex Hobcroft, the director of the New South Wales State Conservatory in Sydney

, the foremost musical institution in Australia

, compared it to Beethoven's Opus 111, the last of Beethoven's sonata

s and held to be his most profound work. (Hobcroft's endorsement appears on the jacket.) Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

's resident psychiatrist, Dr. H. Bloomfield joined in.

During his three years at UCSD, in La Jolla, Clynes gave a concert at Brubecker Hall, playing the Beethoven Diabelli Variations

, as well as a first performance of a group of 5 songs he composed, called "Sentone Songs," employing the remarkable vocal range of Linda Vickerman who performed them. The songs, in his own avant garde style, contained many varied syllables but no known words of any language.

He did studies of laughter at the brain

Institute of UCLA at that time, unsuccessfully attempting to measure the electric counterpart in the brain of the moment that initiates laughter. He was the first to discover, in studying voice recognition in 1975 that a speaker’s identity, though unimpeded by changes in speed (tempo), was masked by transposition of as little as a semitone in pitch. This seemed to indicate that perfect pitch was involved far more universally than thought possible. He began work on a book on laughter, which, however, was only two thirds completed.

In 1977 Rex Hobcroft, director of Sydney's New South Wales

State Conservatory, who had praised Clynes' Sentics, offered Clynes a substantial position at the Conservatory initially connected with the International Piano Competition held at the time in Sydney. Accordingly, Clynes moved to Sydney in what proved to be the beginning of ten fruitful years of research and music making. In 1978 Clynes gave performances of both the Goldberg Variations

and the Diabelli, as well as works of Mozart, at the Verbruggen Hall in Sydney. These performances were recorded live and are today regarded as unsurpassed. From a concertizing point of view, there were unusual difficulties: Clynes' two big-city performances had not been preceded by the usual shake-down cruise of smaller venues: Clynes had only one chance to get it right—and did.

Hobcroft and the government of New South Wales provided Clynes with a Music Research Center and staff at the Conservatory for his work, supplied be the state of NSW Ministry of Education. The staff were mostly enthusiasts of Clynes' work from the United States.

in Sydney, Clynes and his staff presented no fewer than four papers. With the aid of his new DEC PDP 23 computer

and associated oscillator gear, he discovered the principle of Predictive Amplitude Shaping (a precise rule for how the shaping of each note is influenced by what note is next and when it will occur) applicable to music in general, a result he presented at an international conference in Stockholm

at their invitation.

Encouraged by the enthusiastic reception of this work in Stockholm

, Clynes, on his return to Sydney, now made the major leap to discern how a composer's unique pulse is manifest in each note. It had been known (Leopold Mozart, C.P.E. Bach) that in the work of many composers of the "classic" period, a group of, say, four notes, when notated equally, were not meant to be played equally. The leap was in treating the four durations and loudnesses not as separate entities, but as a group, an interconnected organism, a ‘face’ in which each component played a unique role, but all combined together to form a gestalt. To find this gestalt, and how it worked organically in the music, he intuited a specific combined amplitude

and timing "warp," so that each such group has a configuration—a gestalt

--that is characteristic of the particular composer. (Now there was also a link to the motoric pulse, previously identified, which had contained no information about single notes but gave a motoric identity to the output of the brain in conducting music of a particular composer).

The identification of composers' pulse, and its use in interpreting classical works via computer, was later extended by Clynes, according to his knowledge and experience with dynamic forms, to comprise several levels of time structure.

Shortly after this, in 1983-84 Clynes, with the programming help of N. Nettheim, found a method of allowing computers to design vibrato

suitable for each note, depending on the musical structure, also sometimes anticipating next events.

Further, all these principles could be easily generically adjusted for the requirements of each musical piece. Of course, a work’s interpretation was not robotically created: the computer

needed to get adjustments to correspond to the concept of the interpreter. The computer did not replace the human sensitivity, it empowered it instead

When Clynes' longtime close friend and supporter Hephzibah Menuhin

had launched his book Sentics in 1978 in Australia, small symptoms of her developing throat cancer had made their first appearance. Ms. Menuhin

died in 1981, and Clynes gave a memorial concert for her in the Verbruggen Hall, of the last three sonata

s of Beethoven, Op 109, 110, and 111. He had learned Beethoven's Opus 110 especially for that occasion, never having performed it before. Intensive practice resulted in his losing an exquisite living place in Vaucluse and his subsequent relocation to an apartment in Point Piper, an adjacent suburb in Sydney.

In 1982, Clynes undertook further extensive studies on the nature of the expression of emotions through touch. Subjects were touched on the palm of the hand, from behind a screen, with specific emotional expressions, in order to discover whether they could identify the emotion. In fact, they could. Clynes and Walker extended this work in a research trip to central Australia, to the Yuendumu Reservation, to test if Aborigines

would recognize emotions expressed by touch of white urban dwellers when transformed into sounds that conserved the dynamic shape of the touch.

The test was highly positive: the Aborigines did in fact successfully identify the emotions expressed by the touch, of white urban subjects, from which were produced (through a simple transformation, preserving the dynamic shape) the sounds they heard. The American television program Nova reenacted this experiment in 1986, effectively linking the expression of emotions through touch to musical expression, using Beethoven's Eroica

Funeral March to exemplify grief, and a Haydn sonata

for joy.

In 1986, Clynes gave his (or anyone’s) first classical concert played entirely by computer, according to the three principles he had discovered, to a full house in a free concert at the Joseph Post Hall of the Sydney Conservatory. As a result of the application of those principles, the music, ranging from Bach to Beethoven to Robert Schumann and Felix Mendelssohn was musically expressive and meaningful, even though all sounds, except for the piano, were produced by computer-controlled oscillators, and so did not represent familiar instruments—the real time expressive modification of the canonical orchestral sounds remained elusive until 1993.

In 1986, the Fairlight Company, a maker of top-of-the-line synthesizer

s in the hundred thousand dollar range, immediately opted to license what they called "the best sequencer

in the world." Clynes, at that time, did not even know what a sequencer was. Fairlight started paying royalties

on the patent

; however, not long afterwards, the company went bankrupt, having lost government subsidies through a change of government, before bringing the product to market.

Reaching retirement age in Sydney, Clynes left to be professorial associate in the Psychology Department at Melbourne University and became Sugden Fellow at Queen's College, which he had attended as an undergraduate.

He stayed for three years. During that time he found an analytic equation for an egg, incorporating fractal

s, which also provided, with some modification of the equation, beautiful shapes of flowers and of vases. He also performed as pianist, in a Sunday series at Queens College, twelve of the Beethoven sonatas, lecturing to the Physics Department on Time, (starting with a poem beginning, "What time is it?") and to the Medical Faculty on the biologic nature of dynamic expressive forms.

’s pulse, to see which one subjects actually preferred. There were four groups of subjects: internationally well-known pianists, Juilliard graduate students, students at the Manhattan School of Music

, and college students at the University of Melbourne

, altogether some 150 subjects. The results, published in the journal Cognition, showed that the "correct" pulse was preferred in all groups; more pronouncedly so the higher the musical standing of the subjects. (Among the ‘famous pianist subjects’ were friends of Clynes, Vladimir Ashkenazy

and Paul Badura Skoda.)

Clynes returned to the United States in 1991 and settled in Sonoma, California

. Not long after his return he was featured in a large front page article of The Wall Street Journal

, an outgrowth of his invitation to a Canadian meeting on music. This highly favorable article opened many doors. Two vice presidents from Hewlett Packard flew separately to Clynes' home to learn about his findings. When they arrived, Clynes played versions of the same Mozart sonata

K 330 by six famous artists, including Vladimir Horowitz

, Alicia DeLarocha, Claudio Arrau

, and Mitsuo Uchida, and included the computer

performance at a random position among them. The visitors from HP not only could not identify the computer version, but they rated it second best of the seven. (MIDI versions were considered too musically crude to be included).

As a result, Clynes received a development contract that would for the first time enable the expressive implementation of real instrumental sounds other than the piano, using a workstation made available to him by HP, a $40,000 computer, which was, at 150 MHz

, barely fast enough to do this. Clynes enlisted his gifted son Darius as software engineer on the HP team to help make it possible. Nine months later, a critical demonstration took place to show that the principles Clynes had discovered would work well with real instruments, not just with oscillators, to enable music played with meaningful phrasing and expression. Clynes and the assembled HP researchers first heard the sound of flute, violin, and cello from the HP workstation performing a Haydn trio expressively in real time over the loudspeakers of the vast halls of the HP Research Building. The inanities of MIDI had been conquered.

Once Clynes had successfully developed a real-time

implementation of his principles for musical interpretation via computer, using UNIX

, HP gave Clynes' company, Microsound, Intl, a second development contract to bring this capacity into the burgeoning world of personal computer

s (PCs), which, in 1994, functioned at 60 MHz

. A French division of HP, then in charge of PC development, supported this enthusiastically. Clynes was fortunate to obtain the help of Steve Sweet, a programmer

, to carry out the conversion. However, soon thereafter, HP transferred the PC work to a new division in the United States whose director favored popular music.

of Bach

, and then all of Bach

's solo violin and cello works and the last six quartets of Beethoven. All these works were recorded on CDs.

Clynes further expanded SuperConductor's capacity for real life expressive interpretation of music with a fourth principle he called "Self-tuning Expressive Intonation," which unfixes the equal temperament

tuning and permits the sharpening of the leading tone and other modifications of the sort executed by fine players of stringed instruments and other instruments whose intonation is actively controlled in the playing; now even a piano could exhibit this technique—by means of a laptop computer and synthesizer

. Since it is a melodic tuning, depending on intervals, no transposition

was required. The same interval going up received a different small pitch increment from that interval going down. Moreover, similarly to known use in tones like the leading tone, Clynes found it appropriate to provide quite small, specific increments to all melodic intervals, 24 in all (twelve up and twelve different ones down). A new patent [US 6,924,426] was granted in 2006. This now made it possible for all computer

s and synthesizers to benefit from expressive intonation, a non-static, dynamic tuning, in which the same note has a slightly different pitch depending on the melodic structure (the demise of equal temperament

).

After a four-year absence in Thailand

, Steve Sweet returned to Sonoma and resumed his development work with Clynes, incorporating the new functionality into SuperConductor II. (ref to mp3s on the webpage of SuperConductor)

With SuperConductor, Clynes performed Beethoven's Emperor Concerto at MIT's Kresge Auditorium in 1999 to the astonishment and wonder and thunderous applause of over two thousand people. In 2006, using Self-tuning Expressive Intonation, he performed the Schubert Unfinished Symphony

and Beethoven's Eroica

Symphony at the University of Vienna

in the Kleine Konzertsaal.

It became Clynes' aim gradually to make music better than had ever been possible before: to empower the computer in an enterprise of historic proportions to incrementally improve, and increase in profundity, the musical interpretations of great works of our music heritage. With computers, this work of increasing musical perfection could span years, decades, and even centuries.

Clynes has also kept up his own playing of the piano. In 2002, he gave a very substantial concert program (of which a videotape exists) as a memorial for a prominent resident of Sonoma. The program included including Liszt

’s Sixth Hungarian Rhapsody, Campanella

and Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata as well as several major works of Chopin. In 2007, at the age of 82, Clynes has developed new exercises for piano playing away from the piano, which may permit the improvement of piano technique even for octogenarians. In 2007 he applied for three new patents related to SuperConductor, to enhance computer interpretation of music, through: (1) increased mathematical subtlety of note shaping and resulting timbre variations, as earlier, dependent on musical structure, resulting in (2) ‘instant rehearseless conducting’, and (3) importation of note-specific vibrato and shaping from SuperConductor into MIDI files. [patent numbers when available]

Clynes married in 1951, divorced in 1972 and has three children Darius, Neville, and Raphael, and eight grandchildren.

Neurophysiology

Neurophysiology is a part of physiology. Neurophysiology is the study of nervous system function...

.

Overview

Manfred Clynes' work combines music and science, more particularly, neurophysiologyNeurophysiology

Neurophysiology is a part of physiology. Neurophysiology is the study of nervous system function...

and neuroscience

Neuroscience

Neuroscience is the scientific study of the nervous system. Traditionally, neuroscience has been seen as a branch of biology. However, it is currently an interdisciplinary science that collaborates with other fields such as chemistry, computer science, engineering, linguistics, mathematics,...

. Clynes' musical achievements embrace performance and interpretation, exploring and clarifying the function of time forms in the expression of music—and of emotions generally—in connection with brain

Brain

The brain is the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals—only a few primitive invertebrates such as sponges, jellyfish, sea squirts and starfishes do not have one. It is located in the head, usually close to primary sensory apparatus such as vision, hearing,...

function in its electrical manifestations. As a concert pianist

Pianist

A pianist is a musician who plays the piano. A professional pianist can perform solo pieces, play with an ensemble or orchestra, or accompany one or more singers, solo instrumentalists, or other performers.-Choice of genres:...

, he has recorded outstanding versions of Bach

Bạch

Bạch is a Vietnamese surname. The name is transliterated as Bai in Chinese and Baek, in Korean.Bach is the anglicized variation of the surname Bạch.-Notable people with the surname Bạch:* Bạch Liêu...

’s Goldberg Variations

Goldberg Variations

The Goldberg Variations, BWV 988, is a work for harpsichord by Johann Sebastian Bach, consisting of an aria and a set of 30 variations. First published in 1741, the work is considered to be one of the most important examples of variation form...

and of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations

Diabelli Variations

The 33 Variations on a waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120, commonly known as the Diabelli Variations, is a set of variations for the piano written between 1819 and 1823 by Ludwig van Beethoven on a waltz composed by Anton Diabelli...

. As an inventor, his inventions (about 40 patents) include, besides the CAT computer

Computer

A computer is a programmable machine designed to sequentially and automatically carry out a sequence of arithmetic or logical operations. The particular sequence of operations can be changed readily, allowing the computer to solve more than one kind of problem...

for electrical brain

Brain

The brain is the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals—only a few primitive invertebrates such as sponges, jellyfish, sea squirts and starfishes do not have one. It is located in the head, usually close to primary sensory apparatus such as vision, hearing,...

research, the online auto- and cross-correlator, and inventions in the field of ultrasound

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is cyclic sound pressure with a frequency greater than the upper limit of human hearing. Ultrasound is thus not separated from "normal" sound based on differences in physical properties, only the fact that humans cannot hear it. Although this limit varies from person to person, it is...

(Clynes invented color ultrasound.) as well as telemetering, data recording, and wind energy

Wind energy

Wind energy is the kinetic energy of air in motion; see also wind power.Total wind energy flowing through an imaginary area A during the time t is:E = ½ m v2 = ½ v 2...

. The creative process of computer realizations of classical music

Classical music

Classical music is the art music produced in, or rooted in, the traditions of Western liturgical and secular music, encompassing a broad period from roughly the 11th century to present times...

with SuperConductor is based on his discoveries of fundamental principles of musicality. Clynes was the subject of a front page article in the Wall Street Journal, Sept. 21 1991.

Emotion shapes, biologic primacy laws

Clynes concentrated on what he saw as the natural and unalterable interlocking of the central nervous systemCentral nervous system

The central nervous system is the part of the nervous system that integrates the information that it receives from, and coordinates the activity of, all parts of the bodies of bilaterian animals—that is, all multicellular animals except sponges and radially symmetric animals such as jellyfish...

with basic expressive time forms, and on the innate power of those forms to generate specific basic emotions. He recognized that we are all familiar with this interlocking in our experiences of laughter

Laughter

Laughing is a reaction to certain stimuli, fundamentally stress, which serves as an emotional balancing mechanism. Traditionally, it is considered a visual expression of happiness, or an inward feeling of joy. It may ensue from hearing a joke, being tickled, or other stimuli...

and of yawning, although its scientific importance had been largely swept under the carpet by a Skinner

B. F. Skinner

Burrhus Frederic Skinner was an American behaviorist, author, inventor, baseball enthusiast, social philosopher and poet...

ian bias and still largely is. According to Clynes’s experimental research these time forms (“sentic forms”), as embodied in the central nervous system

Central nervous system

The central nervous system is the part of the nervous system that integrates the information that it receives from, and coordinates the activity of, all parts of the bodies of bilaterian animals—that is, all multicellular animals except sponges and radially symmetric animals such as jellyfish...

, are primary to the varied modes in which they find expression, such as sound, touch, and gesture. Clynes was able to prove this by systematically deriving sounds from subjects’ expressions of emotions through touch, and then playing those sounds to hearers culturally remote from the original subjects. In one trial, for example, Aborigines

Australian Aborigines

Australian Aborigines , also called Aboriginal Australians, from the latin ab originem , are people who are indigenous to most of the Australian continentthat is, to mainland Australia and the island of Tasmania...

in Central Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

were able to correctly identify the specific emotional qualities of sounds derived from the touch of white urban Americans. (This experiment was featured on Nova, What Is Music? in 1988). Clynes found in this a confirmation of the existence of biologically fixed, universal, primary dynamic forms that determine expressions of emotion that give rise to much of the experience within human societies.

Some of these dynamic forms appear to be shared by those animals that have time consciousnesses at a similar rate to humans; hence the intuition of pet owners that their dog or cat understands tone of voice and the emotional form of touch. Anger, love, and grief, for example, according to Clynes, have clearly different dynamic expressive forms. Importantly, a cardinal property of this inherent biologic communication language, in Clynes’ findings, is that the more closely an expression follows the precise dynamic form, the more powerful is the generation of the corresponding emotion, in both the person expressing and in the perceiver of the expression. Hence, presumably, such phenomena as charisma (in persons whose performance of emotional expressions closely follows the universal form). His experience with Pablo Casals

Pablo Casals

Pau Casals i Defilló , known during his professional career as Pablo Casals, was a Spanish Catalan cellist and conductor. He is generally regarded as the pre-eminent cellist of the first half of the 20th century, and one of the greatest cellists of all time...

confirmed for Clynes the importance of this faithfulness to the natural dynamic form in generating emotionally significant meaning in musical performance.

Sentic cycles

Drawing on these findings, Clynes also developed an application—a simple touch art form—in which, without music, subjects expressed, through repeated finger pressure, a sequence of emotions timed according to the natural requirements of the sentic forms. The 25-minute sequence, called the Sentic Cycle, comprises: no-emotion, anger, hate, grief, love, sexual desire, joy, and reverence. Subjects reported experiencing calmness and energy. Many also evidenced progress in the alleviation of depressionDepression (mood)

Depression is a state of low mood and aversion to activity that can affect a person's thoughts, behaviour, feelings and physical well-being. Depressed people may feel sad, anxious, empty, hopeless, helpless, worthless, guilty, irritable, or restless...

, and, to some degree, tobacco and alcohol addictions

Substance dependence

The section about substance dependence in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders does not use the word addiction at all. It explains:...

, as a result of repeated application of this process. Thousands of people have by now experienced sentic cycles, some for years, some even decades. In the 1980s especially, Clynes taught various groups to conduct Sentic Cycles on their own. Nowadays, the Sentic Cycle kit is available on the Internet.

Early work developing sentic cycles in the 1970s had convinced Clynes also that it is easy with it for most people to proceed from experiencing one emotion to another quite rapidly. After three or four minutes of one emotion, a person tended to be being satiated with the current emotion. The ready switching to the next emotion with quite fresh experience pointed to the existence of specific receptors in the brain, he suggested, that become satiated with particular neurohormones; this was later confirmed by the identification of a number of such receptors.

This finding links well with the historic tendency of composers to vary emotions every 4 minutes or so in their compositions. The human need for variety is based on brain receptor properties. As anyone who has seen more than three Charlie Chaplin

Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer "Charlie" Chaplin, KBE was an English comic actor, film director and composer best known for his work during the silent film era. He became the most famous film star in the world before the end of World War I...

movies in a row can testify, laughter

Laughter

Laughing is a reaction to certain stimuli, fundamentally stress, which serves as an emotional balancing mechanism. Traditionally, it is considered a visual expression of happiness, or an inward feeling of joy. It may ensue from hearing a joke, being tickled, or other stimuli...

, too, palls after prolonged exposure, and it seems to be for the same reason.

Clynes also studied laughter, "nature's arrow from appearance to reality". In (nonderisive) laughter, according to Clynes, a small element of disorder is suddenly understood to be only apparently disordered, within an actual, larger, order. He then predicted the existence of soundless laughter, in which the sound production is replaced by tactile pressure at the same temporal pattern. In studies at UCSD the mean repetitions of the “ha's” was found to be approximately 5.18 per second. Clynes further hypothesized that couples with unmatched speeds of laughter might not be as readily compatible as those whose laughter was harmoniously coordinated.

Clynes enthusiastically published his realization that love, joy, and reverence were always there to be experienced, capable of being generated through precise expression and accessible by simple means, due to the connection to their biologic roots. Music had always been a special means for this, but now, with this touch artform, it was universally accessible. By this means, even negative emotions, such as grief anger, could be enjoyed in a compassionate non-destructive framework.

In the '70s and in the '80s Clynes had started to write poems, a few of which had found their way into his book Sentics. Later, Marvin Minsky

Marvin Minsky

Marvin Lee Minsky is an American cognitive scientist in the field of artificial intelligence , co-founder of Massachusetts Institute of Technology's AI laboratory, and author of several texts on AI and philosophy.-Biography:...

quoted from them in his book The Society of Mind. In the late 1980s and in the 1990s he wrote his 12 Animal Poems. Boundaries of Compassion is a substantial set of poems growing out of his experience in Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

while doing experimental work at the Luedenscheid hospital in the summer of 1985, poems in regard to what Germans call “the Jewish Question

Jewish Question

The Jewish question encompasses the issues and resolutions surrounding the historically unequal civil, legal and national statuses between minority Ashkenazi Jews and non-Jews, particularly in Europe. The first issues discussed and debated by societies, politicians and writers in western and...

.”

Early invention of inertial guidance at age 15

Manfred Clynes was born on August 14, 1925, in ViennaVienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

. His family emigrated to Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, in September 1938 to escape the Nazis. In Australia, at fifteen, in his last year at high school, having newly learned calculus

Calculus

Calculus is a branch of mathematics focused on limits, functions, derivatives, integrals, and infinite series. This subject constitutes a major part of modern mathematics education. It has two major branches, differential calculus and integral calculus, which are related by the fundamental theorem...

, he invented the inertial guidance method for aircraft using piezoelectric crystals and repeated electronic

Electronics

Electronics is the branch of science, engineering and technology that deals with electrical circuits involving active electrical components such as vacuum tubes, transistors, diodes and integrated circuits, and associated passive interconnection technologies...

integration, but Australian authorities denied that it would work. In fact, the same system Clynes had invented was later used with great success, during the last part of the Second World War. The detailed descriptions of this invention as written by the fifteen-year-old Clynes are rigorous; it was the first of his many inventions to come that worked. (Clynes' earlier attempt, at the age of thirteen, to create a perpetual motion

Perpetual motion

Perpetual motion describes hypothetical machines that operate or produce useful work indefinitely and, more generally, hypothetical machines that produce more work or energy than they consume, whether they might operate indefinitely or not....

device was naturally a failure). In 1946 Clynes graduated from the University of Melbourne

University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public university located in Melbourne, Victoria. Founded in 1853, it is the second oldest university in Australia and the oldest in Victoria...

having studied both engineering

Engineering

Engineering is the discipline, art, skill and profession of acquiring and applying scientific, mathematical, economic, social, and practical knowledge, in order to design and build structures, machines, devices, systems, materials and processes that safely realize improvements to the lives of...

science and music. His musical talent was recognized by a series of awards, concerto

Concerto

A concerto is a musical work usually composed in three parts or movements, in which one solo instrument is accompanied by an orchestra.The etymology is uncertain, but the word seems to have originated from the conjunction of the two Latin words...

performances and prizes, one of which provided a three-year graduate fellowship to the Juilliard School of Music. At Juilliard, he was a piano student of Olga Samaroff

Olga Samaroff

Olga Samaroff was a pianist, music critic, and teacher. Her second husband was conductor Leopold Stokowski.Samaroff was born Lucy Mary Agnes Hickenlooper in San Antonio, Texas, and grew up in Galveston, where her family owned a business later wiped out in the Great 1900 Galveston hurricane...

and Sascha Gorodnitzki

Sascha Gorodnitzki

Sascha Gorodnitzki .Born in Kiev, he emigrated as an infant to Brooklyn, NY, where his parents founded a college of music. He was a child prodigy; his teachers included his mother, then Percy Goetschius, Rubin Goldmark, William J. Henderson and Krehbiel at the Institute of Musical Art. At...

.

He received his MS

Master of Science

A Master of Science is a postgraduate academic master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is typically studied for in the sciences including the social sciences.-Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay:...

degree from Juilliard in 1949, after having performed Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 1 at the Tanglewood Music Festival

Tanglewood Music Festival

The Tanglewood Music Festival is a music festival held every summer on the Tanglewood estate in Lenox, Massachusetts in the Berkshire Hills in western Massachusetts....

(in 1948) then under the direction of Serge Koussevitzky

Serge Koussevitzky

Serge Koussevitzky , was a Russian-born Jewish conductor, composer and double-bassist, known for his long tenure as music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1924 to 1949.-Early career:...

in a performance of which the pianist Gerson Yessin, who was present, recently recalled as "monumental." [Yessin: "Manfred played beautifully, outstandingly."]

After graduating from Juilliard (It gave no doctorates then), Clynes retreated to a small log cabin at six thousand feet altitude in the solitude of Wrightwood, California

Wrightwood, California

Wrightwood is a census-designated place in San Bernardino County, California. It sits at an elevation of . The population was 4,525 at the 2010 census.-History:...

. There he learned Bach's Goldberg Variations

Goldberg Variations

The Goldberg Variations, BWV 988, is a work for harpsichord by Johann Sebastian Bach, consisting of an aria and a set of 30 variations. First published in 1741, the work is considered to be one of the most important examples of variation form...

and other works. He performed them for the first time in October 1949, in Ojai, at J. Krishnamurti's school, and, in 1950, along with other works, in all the capital cities of Australia, to great acclaim. He soon became regarded as one of Australia's outstanding pianists.

In 1952 he was invited to Princeton University

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

as a graduate student in the Music Department, and issued a green card, to pursue his studies in the Psychology of Music, with a Fulbright and Smith-Mundt Award. There he became aware of the work of G. Becking, who in 1928 had published a sensitive, if nonscientific, study of distinctive motor patterns associated in following the music of individual composers. It was this work that led, in the late 1960s, to Clynes' scientific sentographic studies of what he termed composers' pulses, as their motor manifestation, in which Pablo Casals

Pablo Casals

Pau Casals i Defilló , known during his professional career as Pablo Casals, was a Spanish Catalan cellist and conductor. He is generally regarded as the pre-eminent cellist of the first half of the 20th century, and one of the greatest cellists of all time...

and Rudolf Serkin

Rudolf Serkin

Rudolf Serkin , was a Bohemian-born pianist.-Life and early career:Serkin was born in Eger, Bohemia, Austro-Hungarian Empire to a Russian-Jewish family....

were to be his first subjects.

Young Clynes had a personal letter of introduction to Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

from an elderly lady in Australia, with whom, in her youth, Einstein had exchanged poems. Soon Einstein invited him repeatedly to dinner at his home, and a friendship sprang up between the two men. (See details Michelmore’s Life of Einstein.) Clynes played for Einstein on his fine Bechstein piano, especially Beethoven, Mozart and Schubert. He loved Clynes’ Mozart and Schubert, calling Clynes “a blessed artist” (Ein begnadeter Künstler) In May 1953 Einstein wrote Clynes a personal letter by hand to help him in his forthcoming European tour.

Concert tours in 1953 Goldberg Variations

In 1953, helped by the letter from Einstein, Clynes toured Europe with great critical success, playing the Goldberg VariationsGoldberg Variations

The Goldberg Variations, BWV 988, is a work for harpsichord by Johann Sebastian Bach, consisting of an aria and a set of 30 variations. First published in 1741, the work is considered to be one of the most important examples of variation form...

. The tour ended with a solo concert before an audience of 2500 at London's Royal Festival Hall

Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is a 2,900-seat concert, dance and talks venue within Southbank Centre in London. It is situated on the South Bank of the River Thames, not far from Hungerford Bridge. It is a Grade I listed building - the first post-war building to become so protected...

, which had just been built.

Inventions and scientific discoveries

In 1954, in order to provide for his parents and to raise funds necessary to underwrite his musical career, Clynes, on the basis of his scientific training, took a job working with a new analog computerAnalog computer

An analog computer is a form of computer that uses the continuously-changeable aspects of physical phenomena such as electrical, mechanical, or hydraulic quantities to model the problem being solved...

, a device about which, at the time, both he and his interviewer were ignorant. In short shrift, however, Clynes mastered that computer, and then within a year created a new analytic method of stabilizing dynamical system

Dynamical system

A dynamical system is a concept in mathematics where a fixed rule describes the time dependence of a point in a geometrical space. Examples include the mathematical models that describe the swinging of a clock pendulum, the flow of water in a pipe, and the number of fish each springtime in a...

s, which he published as a paper in the IEEE Transactions.

Bogue, the company he was working for, doubled his salary, after a year, unasked. "Only in America!" was Clynes' reaction. (He became a citizen in 1960.)

In 1955, at Clynes' suggestion, Bogue employed his father, then aged 72, from Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, as a naval architect

Architect

An architect is a person trained in the planning, design and oversight of the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to offer or render services in connection with the design and construction of a building, or group of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the...

; the elder Clynes had not been permitted to work in his profession in Australia, because he was not British-born. For a time Clynes father and son went to work together every morning (to Clynes’ rejoicing).

As the result of a chance meeting, in 1956, Dr Nathan S. Kline

Nathan S. Kline

Nathan S. Kline, M.D. was a man of diverse talents and interests whose mind was ever open to new ideas. He was best known for his pioneering work with psychopharmacologic drugs....

, Director of the Research Center of Rockland State Hospital, a large mental hospital, offered Clynes a substantial research job at the Center, where he in 1956 became ‘Chief Research Scientist’. Kline was to become the recipient of two Lasker Awards, and had built up that research center to formidable renown. (It is now called the Nathan S. Kline Psychiatric Center.)

CAT computer

An autodidact in physiology, Clynes applied dynamic systems analysis to the homeostatic and other control processes of the body so successfully in the next three years, that he received a series of awards, including, for the best paper published in 1960 - Clynes' annus mirabilis (miracle year), the IRE W.R.G. Baker Award (1961). In 1960 he invented the CAT computerComputer

A computer is a programmable machine designed to sequentially and automatically carry out a sequence of arithmetic or logical operations. The particular sequence of operations can be changed readily, allowing the computer to solve more than one kind of problem...

(Computer of Average Transients) a $10,000 portable computer permitting the extraction of responses from ongoing electric activity—the needle in the haystack. The CAT quickly came into use in research labs all over the world, marketed by Technical Measurements Corp., advancing the study of the electric activity of the brain (enabling, for example, the clinical detection of deafness in newborns). In this way, Clynes made his fortune by age 37.

URS law

Information

Information in its most restricted technical sense is a message or collection of messages that consists of an ordered sequence of symbols, or it is the meaning that can be interpreted from such a message or collection of messages. Information can be recorded or transmitted. It can be recorded as...

, is basically the consequence of the fact, realized by Clynes, that molecules can only arrive in positive numbers, unlike engineering electric signals, which can be positive or negative. This fact imposes radical limitations on the methods of control that biology

Biology

Biology is a natural science concerned with the study of life and living organisms, including their structure, function, growth, origin, evolution, distribution, and taxonomy. Biology is a vast subject containing many subdivisions, topics, and disciplines...

can use. It cannot, for example, simply cancel a signal by sending a signal of opposite polarity, since there is no simple opposite polarity. To cancel, a second channel involving other, different molecules (chemicals) is required. This law explains, among other things, why the sensations of hot and cold need to operate through two separate sensing channels in the body, why we do not actively sense the disappearance of a smell, and why we continue to feel shocked after a near-miss accident.

Nathan S. Kline

Nathan S. Kline, M.D. was a man of diverse talents and interests whose mind was ever open to new ideas. He was best known for his pioneering work with psychopharmacologic drugs....

, Clynes published the cyborg

Cyborg

A cyborg is a being with both biological and artificial parts. The term was coined in 1960 when Manfred Clynes and Nathan S. Kline used it in an article about the advantages of self-regulating human-machine systems in outer space. D. S...

concept, and its corollary, participant evolution. "Cyborg

Cyborg

A cyborg is a being with both biological and artificial parts. The term was coined in 1960 when Manfred Clynes and Nathan S. Kline used it in an article about the advantages of self-regulating human-machine systems in outer space. D. S...

" became a household word and was misapplied, much to the dismay of Clynes, in films such as Terminator

Terminator

-Science:*Terminator , the line between the day and night sides of a planetary body*Terminator , the end of a gene for transcription-Technology:*Terminator , a resistor at the end of a transmission line to prevent signal reflection...

. Cyborgology is now a field taught at numerous universities. In 1964 the University of Melbourne

University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public university located in Melbourne, Victoria. Founded in 1853, it is the second oldest university in Australia and the oldest in Victoria...

awarded Clynes the degree of D.Sc, a degree superior to Ph. D and rarely given by British universities.

Towards synthesis of scientific and musical work

Pablo Casals

Pau Casals i Defilló , known during his professional career as Pablo Casals, was a Spanish Catalan cellist and conductor. He is generally regarded as the pre-eminent cellist of the first half of the 20th century, and one of the greatest cellists of all time...

since early childhood, Clynes now attended all Casals' master classes, many with his family.

In 1966, Clynes played both the Diabelli Variations

Diabelli Variations

The 33 Variations on a waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120, commonly known as the Diabelli Variations, is a set of variations for the piano written between 1819 and 1823 by Ludwig van Beethoven on a waltz composed by Anton Diabelli...

of Beethoven and Bach

Bạch

Bạch is a Vietnamese surname. The name is transliterated as Bai in Chinese and Baek, in Korean.Bach is the anglicized variation of the surname Bạch.-Notable people with the surname Bạch:* Bạch Liêu...

's Goldberg Variations

Goldberg Variations

The Goldberg Variations, BWV 988, is a work for harpsichord by Johann Sebastian Bach, consisting of an aria and a set of 30 variations. First published in 1741, the work is considered to be one of the most important examples of variation form...

for Casals, and was invited to join Casals in Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico , officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico , is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of both the United States Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.Puerto Rico comprises an...

for several months to take part in his music and to accompany some of the master classes at the Casals home in Santurce. Clynes considered this contact with Casals to be a fulfilment of his most cherished lifelong dream. Casals exceeded his expectations in every way, and Clynes considered his friendship with Casals to have been the highpoint of his life. As no one else, Casals had, by Clynes' estimation an immediate contact with the profound in music. After his return to New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, Clynes performed Beethoven's Fourth Piano Concerto and also gave several concerts at his mansion for invited audiences that included Erich Fromm

Erich Fromm

Erich Seligmann Fromm was a Jewish German-American social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was associated with what became known as the Frankfurt School of critical theory.-Life:Erich Fromm was born on March 23, 1900, at Frankfurt am...

.

Color and the brain

With his new CAT computer, Clynes studied the relation of color processing in the brain and the dynamics to sound, and, jointly with M.Kohn, to color of the pupil of the eye. He showed that brainBrain

The brain is the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals—only a few primitive invertebrates such as sponges, jellyfish, sea squirts and starfishes do not have one. It is located in the head, usually close to primary sensory apparatus such as vision, hearing,...

electrical responses to the color red from previous black produced similar patterns from several distinct brain sites, for all subjects. Other colors produced their own distinct patterns. These results from 1965 went a long way to help dispel the Skinnerian

B. F. Skinner

Burrhus Frederic Skinner was an American behaviorist, author, inventor, baseball enthusiast, social philosopher and poet...

notion of tabula rasa. By 1968 he was able to show that it was possible to distinguish which of 100 different objects a person was looking at from his electrical brain

Brain

The brain is the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals—only a few primitive invertebrates such as sponges, jellyfish, sea squirts and starfishes do not have one. It is located in the head, usually close to primary sensory apparatus such as vision, hearing,...

responses alone, with repeated presentations. In other experiments in 1969 he described what he called the R-M function (from Rest to Motion) detectable at the apex of the brain for various modalities of stimulation, showing how two sets of unidirectionally rate sensitive (URS) channels in series could produce an effect corresponding to the mental concepts Rest and Motion.

What could three URS channel sets do in combination? He never found out.

But here were the beginnings of the embodiments of mental concepts in a wordless manner—a way of representing intuitive concepts to the brain

Brain

The brain is the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals—only a few primitive invertebrates such as sponges, jellyfish, sea squirts and starfishes do not have one. It is located in the head, usually close to primary sensory apparatus such as vision, hearing,...

wordlessly.

The brain as an output device

His work until around 1967 had been concerned with the brain as an input device i.e. for perception; now he began to study it as an outputOutput

Output is the term denoting either an exit or changes which exit a system and which activate/modify a process. It is an abstract concept, used in the modeling, system design and system exploitation.-In control theory:...

device.

He turned first to the question of the characteristic pulse in the music of various composers, which had been on his mind since his Princeton years. In 1967 Clynes designed an instrument he called the sentograph to measure the motoric pulse. The experiments required outstanding musicians to "conduct" music on a pressure-sensitive finger rest, as they were thinking the music without sound. Rudolf Serkin

Rudolf Serkin

Rudolf Serkin , was a Bohemian-born pianist.-Life and early career:Serkin was born in Eger, Bohemia, Austro-Hungarian Empire to a Russian-Jewish family....

and Pablo Casals

Pablo Casals

Pau Casals i Defilló , known during his professional career as Pablo Casals, was a Spanish Catalan cellist and conductor. He is generally regarded as the pre-eminent cellist of the first half of the 20th century, and one of the greatest cellists of all time...

were his first subjects.

Soon it became apparent that the ‘pulse shapes’ for Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Barthóldy , use the form 'Mendelssohn' and not 'Mendelssohn Bartholdy'. The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians gives ' Felix Mendelssohn' as the entry, with 'Mendelssohn' used in the body text...

were consistently different from each another, but similar across their different pieces (when normalized according to selection of similar tempo).

Encouraged by these positive findings relating outputs to specific inner states of the brain, first presented at a Smithsonian Conference in 1968 at Santa Inez, Clynes then proceeded to measure the expressive form of specific emotions in a similar way, by having subjects generate them by repeatedly expressing them on the finger rest, thus finding specific signatures for the emotions, which he called sentic forms. As in the case of composers' pulses, the form associated with each emotion consistently appeared for that emotion and was distinct from the forms of other emotions.

In 1972 Clynes, whose work had long been supported by NIH Grants, received a grant from the Wenner Gren Foundation in Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

, allowing him to collect data in Central Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

, and Bali

Bali

Bali is an Indonesian island located in the westernmost end of the Lesser Sunda Islands, lying between Java to the west and Lombok to the east...

, using the sentograph to investigate emotional expression cross-culturally. Though considerably more limited in scope than the nature of that inquiry would demand, the data were largely confirmatory of Clynes' theories of universal biologically determined time forms for each emotion. At the invitation of the NY Academy of Sciences, Clynes wrote an extensive monograph on his findings and theories to date, which the Academy published in 1973.

That same year he accepted a visiting professorship in the music department of the University of California at San Diego, where he completed his book Sentics, the Touch of Emotion, which he had begun in 1972. In it he summarized the theories and findings on sentics, and outlined hopes for the future that his work contained. In 1970 and 1971, the American Association for the Advancement of Science

American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science is an international non-profit organization with the stated goals of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsibility, and supporting scientific education and science outreach for the...

held two symposia on Sentics.

Since the sentic cycles suddenly helped individuals feel better without drugs, Clynes' work was now deemed contrary to the line of research sponsored at the Rockland State Research Center, headed by Nathan Kline, whose supporters were the major drug companies. As a result, Clynes was unable to continue the work at that facility. In his new environment, there was no laboratory in which to amass new data. Although dismissed by the NY Times, Sentics was lauded extravagantly in other publications. (The book is considered a classic today). It was read in manuscript with great approval and excitement by several authorities: Yehudi Menuhin volunteered a foreword, itself a remarkable document, welcoming Clynes "as a brother." Rex Hobcroft, the director of the New South Wales State Conservatory in Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

, the foremost musical institution in Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, compared it to Beethoven's Opus 111, the last of Beethoven's sonata

Sonata

Sonata , in music, literally means a piece played as opposed to a cantata , a piece sung. The term, being vague, naturally evolved through the history of music, designating a variety of forms prior to the Classical era...

s and held to be his most profound work. (Hobcroft's endorsement appears on the jacket.) Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi , born Mahesh Prasad Varma , developed the Transcendental Meditation technique and was the leader and guru of the TM movement, characterised as a new religious movement and also as non-religious...

's resident psychiatrist, Dr. H. Bloomfield joined in.

During his three years at UCSD, in La Jolla, Clynes gave a concert at Brubecker Hall, playing the Beethoven Diabelli Variations

Diabelli Variations