Joseph Southall

Encyclopedia

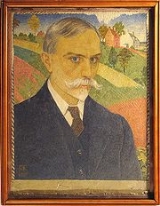

Joseph Edward Southall RWS

NEAC

RBSA

(23 August 1861 – 6 November 1944) was an English

painter

associated with the Arts and Crafts movement

.

A leading figure in the nineteenth century revival of painting in tempera

, Southall was the leader of the Birmingham Group of Artist-Craftsmen—one of the last outposts of Romanticism

in the visual arts, and an important link between the later Pre-Raphaelites and the turn of the century Slade Symbolists

.

A lifelong Quaker, Southall was an active socialist

and pacifist

, initially as a radical member the Liberal Party

and later of the Independent Labour Party

.

in 1861. His father, a grocer, died a little over a year later, and the young Southall and his mother moved to Edgbaston

, Birmingham

to live with his mother's family.

After an education at Quaker schools including Ackworth School

and Bootham School

in York

, Southall returned to Birmingham in 1878 and was articled as a trainee with the leading local architects' practice Martin & Chamberlain

, while studying painting part-time at the Birmingham School of Art

. Both institutions were steeped in the spirit of John Ruskin

and the Arts and Crafts movement

: architect John Henry Chamberlain

was a founder and trustee of the Guild of St George

, while the Principal of the School of Art, Edward R. Taylor

, was a pioneer of Arts and Crafts education and a friend of William Morris

and Edward Burne-Jones

.

Southall however was frustrated by his architectural training, feeling that an architect should have a broader understanding of craft disciplines such as painting and carving. With this in mind he undertook several tours in Europe. In 1882 he visited Bayeux

, Rouen

and Amiens

in Northern France

. The following year, having left Martin & Chamberlain, he spent thirteen weeks in Italy

, visiting Pisa

, Florence

, Siena

, Orvieto

, Rome

, Bologna

, Padua

, Venice

and Milan

.

Italy was to have a profound impact. The frescoes of Benozzo Gozzoli

were to inspire a deep admiration for the painters of the Italian Renaissance

who - before the practice of oil painting

spread to Italy from Northern Europe in the sixteenth century - worked largely in egg-based tempera

. Forty years later Southall recalled:

Southall's decisive moment came while viewing Two Venetian Ladies

by Vittore Carpaccio

in the Museo Correr

in Venice

. Ruskin's discussion of the painting in St Marks' Rest -- the volume that Southall was using as a guide—included Ruskin's remark that "I must note in passing that many of the qualities which I have been in the habit of praising in Tintoret and Carpaccio, as consummate achievements in oil-painting are, as I have found lately, either in tempera altogether or tempera with oil above. And I am disposed to think that ultimately tempera will be found the proper material for the greater number of most delightful subjects." On his return to Birmingham Southall conducted his first experiments in tempera painting at the School of Art.

- a friend of John Ruskin

and Master of Ruskin's Guild of St George

- passed some of Southall's Italian sketches on to Ruskin himself, who remarked that "he had never seen architecture better drawn".

Ruskin was so impressed by Southall's architectural understanding that in 1885 he gave him his first major commission: to design a museum for the Guild of St George to stand on his uncle's land near Bewdley

, Worcestershire

. Southall made a second trip to Italy in 1886 to research this commission, but the project was abandoned when Ruskin revived his original plans to build a museum in Sheffield

. Southall later recalled "my chance as an architect vanished and years of obscurity with not a little bitterness of soul followed".

Southall's experiments with tempera were also taxing throughout the late 1880s, and for a while he returned to oils

Southall's experiments with tempera were also taxing throughout the late 1880s, and for a while he returned to oils

. A third visit to Italy in 1890 re ignited his enthusiasm, however, and from 1893 his increasingly successful works in tempera received the wholehearted support of Edward Burne-Jones

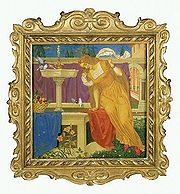

, who expressed particular admiration for Beauty Seeing the Image of her Home in the Fountain and personally submitted Southall's work for exhibition alongside his own.

By the late 1890s Southall's experiments had established a method of painting that, while not identical to those documented by Italian sources such as Cennino Cennini, was practical, viable and a genuine tempera method. Although he was not the first Victorian artist to experiment with tempera (John Roddam Spencer Stanhope

had exhibited a tempera painting in 1880) he was acknowledged as one of the leaders of its revival, exhibiting with the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society

, the Royal Academy

and the Paris Salon

. In 1901 he was prominent among the artists who exhibited at the Modern Paintings in Tempera exhibition at Leighton House Museum

and six months later was one of the founder members of the Society of Painters in Tempera

, writing the first of the society's technical papers on Grounds suitable for painting in Tempera.

Although Southall was never on the staff of the Birmingham School of Art

, he maintained close friendships with the core of staff and pupils at the school who would later be identified as the Birmingham Group of Artist-Craftsmen - introducing artists such as Henry Payne

, Maxwell Armfield

and Arthur Gaskin

(a lifelong friend) to his methods during technical demonstrations at his studio in Edgbaston

.

The years before the outbreak of World War I

The years before the outbreak of World War I

saw Southall at the height of his achievement and fame. He worked on a series of large tempera paintings on mythological subjects that were widely exhibited across Europe

and the United States

. These could take up to two years to complete but were to establish his reputation critically.

He was elected an Associate of the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists

in 1898 and a full Member in 1902, a member of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society

in 1903 and of the Art Workers Guild

and Union Internationale des Beaux-Arts et des Lettres in 1910. In 1907 he was prominent in the first exhibition dedicated to the work of the Birmingham Group held at the Fine Art Society

in London

, and in 1910 he was the subject of a one-man exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit

in Paris

, which was both a critical and a commercial triumph.

In 1903 Southall married Anna Elizabeth Baker. The couple had been close companions since their youth and had always intended to marry, but were cousins and had deliberately put off marriage until she was after child-bearing age.

, as the pacifism

inherent in his Quaker faith led him to devote his energies to anti-war campaigning. His main artistic output during this period were anti-war cartoon

s printed in pamphlets and magazines, which number among his most powerful works.

Post-war, with his reputation well established, Southall produced fewer of the epic (and time consuming) tempera works that made his critical name. Much of his life involved travel: favourite destinations included France

, Italy

, Fowey

in Cornwall

and Southwold

in Suffolk

, and these trips generally resulted in series of landscapes, often in watercolour. Between trips his time was spent painting portraits for wealthy, often Quaker, patrons. He was elected a member of the Royal Watercolour Society

and the New English Art Club

in 1925, and in 1939 was elected President of the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists

- a post he held until his death.

In 1937 Southall underwent an operation from which he never really recovered. After several years of ill health, during which he doggedly continued to paint, he died of heart failure at his home in Edgbaston in 1944.

Southall painted a variety of subjects during his career, including mythological, romantic, and religious subjects, portraits and landscapes. He was known for his mastery of the colour red, the clean and clear light in his works, and for his paintings on the theme of Beauty and the Beast

Southall painted a variety of subjects during his career, including mythological, romantic, and religious subjects, portraits and landscapes. He was known for his mastery of the colour red, the clean and clear light in his works, and for his paintings on the theme of Beauty and the Beast

.

Southall's choice of medium was heavily informed by his Arts and Crafts

belief that the physical act of creation was as important as the act of design. Aesthetically egg tempera provided the luminescence and jewel-like quality that had been so sought after by the Pre-Raphaelites (who never themselves perfected the technique), but it also gave him the opportunity to fashion his own materials by hand. To obtain the egg yolks required he even kept his own chickens.

Although Southall also painted in a variety of other laborious media (such as the watercolour on vellum of his work Hortus Inclusus), lack of patronage limited his work in fresco

- the medium he personally found most interesting. His best known fresco Corporation Street Birmingham in March 1914 - painted for Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

- was described by William Rothenstein

as "perhaps the most perfect painted in the last three centuries".

In common with other Birmingham Group members Southall also practiced a variety of crafts besides painting, including murals, furniture decoration, lace

work, book illustration and engraving

s. Many of his paintings have frames featuring decorative work by his wife or other Birmingham Group figures such as Georgie Gaskin

or Charles Gere - such decoration was considered integral to the work of art.

modernism

. Roger Fry

described him as "a little slightly disgruntled and dyspeptic Quaker artist who does incredible tempera sham Quattrocentro modern sentimental things with a terrible kind of meticulous skill"

With the renewed interest in Victorian art this began to be seen as a misrepresentation. John Russell Taylor

, art critic of The Times

, described him in 1980 as "a natural-born surrealist"; writing that "there is undoubtedly an authentic strangeness in the way he saw things, which comes out most powerfully in his tempera paintings of contemporary life, but also casts a weird light over many of his watercolours ... we are much more likely to find ourselves thinking of Magritte and Balthus

and Chirico than of anyone nearer to this apparently stick-in-the-mud Arts-and-Craftsman." Pablo Picasso

is recorded by Osbert Sitwell

as being so impressed by a Southall painting when visiting Violet Gordon-Woodhouse

in the 1920s that he tried to buy it on the spot for his private collection.

Far from being isolated from developments on the continent, Southall's reputation was if anything higher in France than in England, with exhibitions at the Salon de Champs-Élysées

and the Salon de Champs-de-Mars from the 1890s onwards, and membership of the Union Internationale des Beaux-Arts et des Lettres in 1910 and the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1925. His most successful exhibition was that at the Galerie Georges Petit

in Paris

- one of the main centres of progressive French art.

addressing a Birmingham political meeting might be taken as an early indication of radical interest.

Southall politics were strongly influenced by the pacifism

of his Quaker faith. His opposition to the tide of jingoism

that surrounded the Jameson Raid

in 1895 provoked him into political action, and the outbreak of World War I

in 1914 caused him to switch his allegiance from the Liberal Party

to the anti-war Independent Labour Party

, for whose Birmingham branch he served as secretary from 1914 until 1931.

Southall's obituary in the Birmingham Post

recorded that he was always "an enthusiastic supporter of that Socialism or Communism which William Morris expressed in his News from Nowhere".

Royal Watercolour Society

The Royal Watercolour Society is an English institution of painters working in watercolours...

NEAC

New English Art Club

The New English Art Club was founded in London in 1885 as an alternate venue to the Royal Academy.-History:Young English artists returning from studying art in Paris mounted the first exhibition of the New English Art Club in April 1886...

RBSA

Royal Birmingham Society of Artists

The Royal Birmingham Society of Artists or RBSA is a learned society of artists and an art gallery based in the Jewellery Quarter in Birmingham, England. it is both a registered charity. and a registered company The Royal Birmingham Society of Artists or RBSA is a learned society of artists and an...

(23 August 1861 – 6 November 1944) was an English

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

painter

Painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a surface . The application of the medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush but other objects can be used. In art, the term painting describes both the act and the result of the action. However, painting is...

associated with the Arts and Crafts movement

Arts and Crafts movement

Arts and Crafts was an international design philosophy that originated in England and flourished between 1860 and 1910 , continuing its influence until the 1930s...

.

A leading figure in the nineteenth century revival of painting in tempera

Tempera

Tempera, also known as egg tempera, is a permanent fast-drying painting medium consisting of colored pigment mixed with a water-soluble binder medium . Tempera also refers to the paintings done in this medium. Tempera paintings are very long lasting, and examples from the 1st centuries AD still exist...

, Southall was the leader of the Birmingham Group of Artist-Craftsmen—one of the last outposts of Romanticism

Romanticism

Romanticism was an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe, and gained strength in reaction to the Industrial Revolution...

in the visual arts, and an important link between the later Pre-Raphaelites and the turn of the century Slade Symbolists

Symbolism (arts)

Symbolism was a late nineteenth-century art movement of French, Russian and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts. In literature, the style had its beginnings with the publication Les Fleurs du mal by Charles Baudelaire...

.

A lifelong Quaker, Southall was an active socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

and pacifist

Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war and violence. The term "pacifism" was coined by the French peace campaignerÉmile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress inGlasgow in 1901.- Definition :...

, initially as a radical member the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

and later of the Independent Labour Party

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party was a socialist political party in Britain established in 1893. The ILP was affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 to 1932, when it voted to leave...

.

Early life

Joseph Southall was born to a Quaker family in NottinghamNottingham

Nottingham is a city and unitary authority in the East Midlands of England. It is located in the ceremonial county of Nottinghamshire and represents one of eight members of the English Core Cities Group...

in 1861. His father, a grocer, died a little over a year later, and the young Southall and his mother moved to Edgbaston

Edgbaston

Edgbaston is an area in the city of Birmingham in England. It is also a formal district, managed by its own district committee. The constituency includes the smaller Edgbaston ward and the wards of Bartley Green, Harborne and Quinton....

, Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

to live with his mother's family.

After an education at Quaker schools including Ackworth School

Ackworth School

Ackworth School is an independent school located in the village of High Ackworth, near Pontefract, West Yorkshire, England. It is one of eight Quaker Schools in England. The school is a member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference and SHMIS . The Head is Kathryn Bell, who succeeded...

and Bootham School

Bootham School

Bootham School is an independent Quaker boarding school in the city of York in North Yorkshire, England. It was founded by the Religious Society of Friends in 1823. It is close to York Minster. The current headmaster is Jonathan Taylor. The school's motto Membra Sumus Corporis Magni means "We...

in York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

, Southall returned to Birmingham in 1878 and was articled as a trainee with the leading local architects' practice Martin & Chamberlain

Martin & Chamberlain

John Henry Chamberlain, William Martin, and Frederick Martin were architects in Victorian Birmingham, England. Their names are attributed singly or pairs to many red brick and terracotta buildings, particularly 41 of the forty-odd Birmingham board schools made necessary by the Elementary Education...

, while studying painting part-time at the Birmingham School of Art

Birmingham School of Art

The Birmingham School of Art was a municipal art school based in the centre of Birmingham, England. Although the organisation was absorbed by Birmingham Polytechnic in 1971 and is now part of Birmingham City University's Birmingham Institute of Art and Design, its Grade I listed building on...

. Both institutions were steeped in the spirit of John Ruskin

John Ruskin

John Ruskin was the leading English art critic of the Victorian era, also an art patron, draughtsman, watercolourist, a prominent social thinker and philanthropist. He wrote on subjects ranging from geology to architecture, myth to ornithology, literature to education, and botany to political...

and the Arts and Crafts movement

Arts and Crafts movement

Arts and Crafts was an international design philosophy that originated in England and flourished between 1860 and 1910 , continuing its influence until the 1930s...

: architect John Henry Chamberlain

John Henry Chamberlain

John Henry Chamberlain , generally known professionally as J H Chamberlain, was a nineteenth century English architect....

was a founder and trustee of the Guild of St George

Guild of St George

The Guild of St George is charitable trust founded by John Ruskin in England in the 1870s as a vehicle to implement his ideas about how society should be re-organised. Its members, who are called Companions, were originally required to give a tithe of their income to the Guild...

, while the Principal of the School of Art, Edward R. Taylor

Edward R. Taylor

Edward Richard Taylor RBSA was an English artist and educator. He painted in both oils and watercolours.Taylor taught at the Lincoln School of Art and became influential in the Arts and Crafts movement as the first headmaster at the Birmingham Municipal School of Arts and Crafts from 1877-1903.In...

, was a pioneer of Arts and Crafts education and a friend of William Morris

William Morris

William Morris 24 March 18343 October 1896 was an English textile designer, artist, writer, and socialist associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the English Arts and Crafts Movement...

and Edward Burne-Jones

Edward Burne-Jones

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet was a British artist and designer closely associated with the later phase of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, who worked closely with William Morris on a wide range of decorative arts as a founding partner in Morris, Marshall, Faulkner, and Company...

.

Southall however was frustrated by his architectural training, feeling that an architect should have a broader understanding of craft disciplines such as painting and carving. With this in mind he undertook several tours in Europe. In 1882 he visited Bayeux

Bayeux

Bayeux is a commune in the Calvados department in Normandy in northwestern France.Bayeux is the home of the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England.-Administration:Bayeux is a sub-prefecture of Calvados...

, Rouen

Rouen

Rouen , in northern France on the River Seine, is the capital of the Haute-Normandie region and the historic capital city of Normandy. Once one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe , it was the seat of the Exchequer of Normandy in the Middle Ages...

and Amiens

Amiens

Amiens is a city and commune in northern France, north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in Picardy...

in Northern France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. The following year, having left Martin & Chamberlain, he spent thirteen weeks in Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, visiting Pisa

Pisa

Pisa is a city in Tuscany, Central Italy, on the right bank of the mouth of the River Arno on the Tyrrhenian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa...

, Florence

Florence

Florence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany and of the province of Florence. It is the most populous city in Tuscany, with approximately 370,000 inhabitants, expanding to over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area....

, Siena

Siena

Siena is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena.The historic centre of Siena has been declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Site. It is one of the nation's most visited tourist attractions, with over 163,000 international arrivals in 2008...

, Orvieto

Orvieto

Orvieto is a city and comune in Province of Terni, southwestern Umbria, Italy situated on the flat summit of a large butte of volcanic tuff...

, Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

, Bologna

Bologna

Bologna is the capital city of Emilia-Romagna, in the Po Valley of Northern Italy. The city lies between the Po River and the Apennine Mountains, more specifically, between the Reno River and the Savena River. Bologna is a lively and cosmopolitan Italian college city, with spectacular history,...

, Padua

Padua

Padua is a city and comune in the Veneto, northern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Padua and the economic and communications hub of the area. Padua's population is 212,500 . The city is sometimes included, with Venice and Treviso, in the Padua-Treviso-Venice Metropolitan Area, having...

, Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

and Milan

Milan

Milan is the second-largest city in Italy and the capital city of the region of Lombardy and of the province of Milan. The city proper has a population of about 1.3 million, while its urban area, roughly coinciding with its administrative province and the bordering Province of Monza and Brianza ,...

.

Italy was to have a profound impact. The frescoes of Benozzo Gozzoli

Benozzo Gozzoli

Benozzo Gozzoli was an Italian Renaissance painter from Florence. He is best known for a series of murals in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi depicting festive, vibrant processions with wonderful attention to detail and a pronounced International Gothic influence.-Apprenticeship:He was born Benozzo di...

were to inspire a deep admiration for the painters of the Italian Renaissance

Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance began the opening phase of the Renaissance, a period of great cultural change and achievement in Europe that spanned the period from the end of the 13th century to about 1600, marking the transition between Medieval and Early Modern Europe...

who - before the practice of oil painting

Oil painting

Oil painting is the process of painting with pigments that are bound with a medium of drying oil—especially in early modern Europe, linseed oil. Often an oil such as linseed was boiled with a resin such as pine resin or even frankincense; these were called 'varnishes' and were prized for their body...

spread to Italy from Northern Europe in the sixteenth century - worked largely in egg-based tempera

Tempera

Tempera, also known as egg tempera, is a permanent fast-drying painting medium consisting of colored pigment mixed with a water-soluble binder medium . Tempera also refers to the paintings done in this medium. Tempera paintings are very long lasting, and examples from the 1st centuries AD still exist...

. Forty years later Southall recalled:

Southall's decisive moment came while viewing Two Venetian Ladies

Two Venetian Ladies

Two Venetian Ladies is a painting by the Italian Renaissance artist Vittore Carpaccio.The painting, believed to be a quarter of the original work, was executed around 1490 and shows two unknown Venetian ladies. The top portion of the panel, called Hunting on the Lagoon is in the Getty Museum, and...

by Vittore Carpaccio

Vittore Carpaccio

Vittore Carpaccio was an Italian painter of the Venetian school, who studied under Gentile Bellini. He is best known for a cycle of nine paintings, The Legend of Saint Ursula. His style was somewhat conservative, showing little influence from the Humanist trends that transformed Italian...

in the Museo Correr

Museo Correr

The Museo Correr is the civic museum of Venice, located in the Piazza San Marco, and is entered by the ceremonial stairway in the Ala Napoleonica at the western end of the Piazza opposite the church of San Marco at the other end...

in Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

. Ruskin's discussion of the painting in St Marks' Rest -- the volume that Southall was using as a guide—included Ruskin's remark that "I must note in passing that many of the qualities which I have been in the habit of praising in Tintoret and Carpaccio, as consummate achievements in oil-painting are, as I have found lately, either in tempera altogether or tempera with oil above. And I am disposed to think that ultimately tempera will be found the proper material for the greater number of most delightful subjects." On his return to Birmingham Southall conducted his first experiments in tempera painting at the School of Art.

Hiatus

Initially, however, Southall's discovery of Italian tempera painting had less effect than his studies of Italian architecture. Southall's uncle George BakerGeorge Baker

George Baker may refer to:*George Baker , English surgeon*Sir George Baker, 1st Baronet , British physician*George Baker...

- a friend of John Ruskin

John Ruskin

John Ruskin was the leading English art critic of the Victorian era, also an art patron, draughtsman, watercolourist, a prominent social thinker and philanthropist. He wrote on subjects ranging from geology to architecture, myth to ornithology, literature to education, and botany to political...

and Master of Ruskin's Guild of St George

Guild of St George

The Guild of St George is charitable trust founded by John Ruskin in England in the 1870s as a vehicle to implement his ideas about how society should be re-organised. Its members, who are called Companions, were originally required to give a tithe of their income to the Guild...

- passed some of Southall's Italian sketches on to Ruskin himself, who remarked that "he had never seen architecture better drawn".

Ruskin was so impressed by Southall's architectural understanding that in 1885 he gave him his first major commission: to design a museum for the Guild of St George to stand on his uncle's land near Bewdley

Bewdley

Bewdley is a town and civil parish in the Wyre Forest District of Worcestershire, England, along the Severn Valley a few miles to the west of Kidderminster...

, Worcestershire

Worcestershire

Worcestershire is a non-metropolitan county, established in antiquity, located in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes it is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three counties that comprise the "Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire" NUTS 2 region...

. Southall made a second trip to Italy in 1886 to research this commission, but the project was abandoned when Ruskin revived his original plans to build a museum in Sheffield

Sheffield

Sheffield is a city and metropolitan borough of South Yorkshire, England. Its name derives from the River Sheaf, which runs through the city. Historically a part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, and with some of its southern suburbs annexed from Derbyshire, the city has grown from its largely...

. Southall later recalled "my chance as an architect vanished and years of obscurity with not a little bitterness of soul followed".

Tempera revival

Oil paint

Oil paint is a type of slow-drying paint that consists of particles of pigment suspended in a drying oil, commonly linseed oil. The viscosity of the paint may be modified by the addition of a solvent such as turpentine or white spirit, and varnish may be added to increase the glossiness of the...

. A third visit to Italy in 1890 re ignited his enthusiasm, however, and from 1893 his increasingly successful works in tempera received the wholehearted support of Edward Burne-Jones

Edward Burne-Jones

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet was a British artist and designer closely associated with the later phase of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, who worked closely with William Morris on a wide range of decorative arts as a founding partner in Morris, Marshall, Faulkner, and Company...

, who expressed particular admiration for Beauty Seeing the Image of her Home in the Fountain and personally submitted Southall's work for exhibition alongside his own.

By the late 1890s Southall's experiments had established a method of painting that, while not identical to those documented by Italian sources such as Cennino Cennini, was practical, viable and a genuine tempera method. Although he was not the first Victorian artist to experiment with tempera (John Roddam Spencer Stanhope

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope

John Roddam Spencer-Stanhope is an English artist associated with Edward Burne-Jones and George Frederic Watts and often regarded as a second-wave pre-Raphaelite. His work is also studied within the context of Aestheticism and British Symbolism. As a painter, Stanhope worked in oil, watercolor,...

had exhibited a tempera painting in 1880) he was acknowledged as one of the leaders of its revival, exhibiting with the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society

Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society

The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society was formed in London in 1887 to promote the exhibition of decorative arts alongside fine arts. Its exhibitions, held annually at the New Gallery from 1888–90, and roughly every three years thereafter, were important in the flowering of the British Arts and...

, the Royal Academy

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly, London. The Royal Academy of Arts has a unique position in being an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects whose purpose is to promote the creation, enjoyment and...

and the Paris Salon

Paris Salon

The Salon , or rarely Paris Salon , beginning in 1725 was the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France. Between 1748–1890 it was the greatest annual or biannual art event in the Western world...

. In 1901 he was prominent among the artists who exhibited at the Modern Paintings in Tempera exhibition at Leighton House Museum

Leighton House Museum

Leighton House Museum is a museum in Holland Park, London, England. It is housed in the former home of the painter Frederic, Lord Leighton. The first part of the house was designed in 1864 by the architect George Aitchison, although Leighton was not granted a lease on the land until April 1866...

and six months later was one of the founder members of the Society of Painters in Tempera

Society of Painters in Tempera

The Society of Painters in Tempera was founded in 1901 by Christiana Herringham and a group of British painters who were interested in reviving the art of tempera painting. Lady Herringham was an expert copyist of the Italian Old Masters and had translated Il Libro dell' Arte o Trattato della...

, writing the first of the society's technical papers on Grounds suitable for painting in Tempera.

Although Southall was never on the staff of the Birmingham School of Art

Birmingham School of Art

The Birmingham School of Art was a municipal art school based in the centre of Birmingham, England. Although the organisation was absorbed by Birmingham Polytechnic in 1971 and is now part of Birmingham City University's Birmingham Institute of Art and Design, its Grade I listed building on...

, he maintained close friendships with the core of staff and pupils at the school who would later be identified as the Birmingham Group of Artist-Craftsmen - introducing artists such as Henry Payne

Henry Payne (artist)

Henry Arthur Payne RWS was an English stained glass artist, watercolourist and painter of frescoes.Payne was one of the Birmingham Group of Artist-Craftsmen who formed around Joseph Southall and the Birmingham School of Art in the late nineteenth century...

, Maxwell Armfield

Maxwell Armfield

Maxwell Ashby Armfield was an English artist, illustrator and writer.Born to a Quaker family in Ringwood, Hampshire, Armfield was educated at Sidcot School and at Leighton Park School. In 1887 he was admitted to Birmingham School of Art, then under the headmastership of Edward R...

and Arthur Gaskin

Arthur Gaskin

Arthur Joseph Gaskin RBSA was an English illustrator, painter, teacher and designer of jewellery and enamelwork....

(a lifelong friend) to his methods during technical demonstrations at his studio in Edgbaston

Edgbaston

Edgbaston is an area in the city of Birmingham in England. It is also a formal district, managed by its own district committee. The constituency includes the smaller Edgbaston ward and the wards of Bartley Green, Harborne and Quinton....

.

Edwardian heyday

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

saw Southall at the height of his achievement and fame. He worked on a series of large tempera paintings on mythological subjects that were widely exhibited across Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

and the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. These could take up to two years to complete but were to establish his reputation critically.

He was elected an Associate of the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists

Royal Birmingham Society of Artists

The Royal Birmingham Society of Artists or RBSA is a learned society of artists and an art gallery based in the Jewellery Quarter in Birmingham, England. it is both a registered charity. and a registered company The Royal Birmingham Society of Artists or RBSA is a learned society of artists and an...

in 1898 and a full Member in 1902, a member of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society

Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society

The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society was formed in London in 1887 to promote the exhibition of decorative arts alongside fine arts. Its exhibitions, held annually at the New Gallery from 1888–90, and roughly every three years thereafter, were important in the flowering of the British Arts and...

in 1903 and of the Art Workers Guild

Art Workers Guild

The Art Workers Guild or Art-Workers' Guild is an organisation established in 1884 by a group of British architects associated with the ideas of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement. The guild promoted the 'unity of all the arts', denying the distinction between fine and applied art...

and Union Internationale des Beaux-Arts et des Lettres in 1910. In 1907 he was prominent in the first exhibition dedicated to the work of the Birmingham Group held at the Fine Art Society

Fine Art Society

The Fine Art Society is an art dealership with two premises, one in New Bond Street, London and the other in Edinburgh . It was formed in 1876...

in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, and in 1910 he was the subject of a one-man exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit

Georges Petit

Georges Petit was a French art dealer, a key figure in the Paris art world and an important promoter and cultivator of Impressionist artists.-Early career:...

in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, which was both a critical and a commercial triumph.

In 1903 Southall married Anna Elizabeth Baker. The couple had been close companions since their youth and had always intended to marry, but were cousins and had deliberately put off marriage until she was after child-bearing age.

World War I and after

Southall's output as a painter declined considerably with the outbreak of World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, as the pacifism

Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war and violence. The term "pacifism" was coined by the French peace campaignerÉmile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress inGlasgow in 1901.- Definition :...

inherent in his Quaker faith led him to devote his energies to anti-war campaigning. His main artistic output during this period were anti-war cartoon

Cartoon

A cartoon is a form of two-dimensional illustrated visual art. While the specific definition has changed over time, modern usage refers to a typically non-realistic or semi-realistic drawing or painting intended for satire, caricature, or humor, or to the artistic style of such works...

s printed in pamphlets and magazines, which number among his most powerful works.

Post-war, with his reputation well established, Southall produced fewer of the epic (and time consuming) tempera works that made his critical name. Much of his life involved travel: favourite destinations included France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, Fowey

Fowey

Fowey is a small town, civil parish and cargo port at the mouth of the River Fowey in south Cornwall, United Kingdom. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 2,273.-Early history:...

in Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

and Southwold

Southwold

Southwold is a town on the North Sea coast, in the Waveney district of the English county of Suffolk. It is located on the North Sea coast at the mouth of the River Blyth within the Suffolk Coast and Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The town is around south of Lowestoft and north-east...

in Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in East Anglia, England. It has borders with Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south. The North Sea lies to the east...

, and these trips generally resulted in series of landscapes, often in watercolour. Between trips his time was spent painting portraits for wealthy, often Quaker, patrons. He was elected a member of the Royal Watercolour Society

Royal Watercolour Society

The Royal Watercolour Society is an English institution of painters working in watercolours...

and the New English Art Club

New English Art Club

The New English Art Club was founded in London in 1885 as an alternate venue to the Royal Academy.-History:Young English artists returning from studying art in Paris mounted the first exhibition of the New English Art Club in April 1886...

in 1925, and in 1939 was elected President of the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists

Royal Birmingham Society of Artists

The Royal Birmingham Society of Artists or RBSA is a learned society of artists and an art gallery based in the Jewellery Quarter in Birmingham, England. it is both a registered charity. and a registered company The Royal Birmingham Society of Artists or RBSA is a learned society of artists and an...

- a post he held until his death.

In 1937 Southall underwent an operation from which he never really recovered. After several years of ill health, during which he doggedly continued to paint, he died of heart failure at his home in Edgbaston in 1944.

Work

Beauty and the Beast

Beauty and the Beast is a traditional fairy tale. The first published version of the fairy tale was a rendition by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, published in La jeune américaine, et les contes marins in 1740...

.

Southall's choice of medium was heavily informed by his Arts and Crafts

Arts and Crafts movement

Arts and Crafts was an international design philosophy that originated in England and flourished between 1860 and 1910 , continuing its influence until the 1930s...

belief that the physical act of creation was as important as the act of design. Aesthetically egg tempera provided the luminescence and jewel-like quality that had been so sought after by the Pre-Raphaelites (who never themselves perfected the technique), but it also gave him the opportunity to fashion his own materials by hand. To obtain the egg yolks required he even kept his own chickens.

Although Southall also painted in a variety of other laborious media (such as the watercolour on vellum of his work Hortus Inclusus), lack of patronage limited his work in fresco

Fresco

Fresco is any of several related mural painting types, executed on plaster on walls or ceilings. The word fresco comes from the Greek word affresca which derives from the Latin word for "fresh". Frescoes first developed in the ancient world and continued to be popular through the Renaissance...

- the medium he personally found most interesting. His best known fresco Corporation Street Birmingham in March 1914 - painted for Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery is a museum and art gallery in Birmingham, England.Entrance to the Museum and Art Gallery is free, but some major exhibitions in the Gas Hall incur an entrance fee...

- was described by William Rothenstein

William Rothenstein

Sir William Rothenstein was an English painter, draughtsman and writer on art.-Life and work:William Rothenstein was born into a German-Jewish family in Bradford, West Yorkshire. His father, Moritz, emigrated from Germany in 1859 to work in Bradford's burgeoning textile industry...

as "perhaps the most perfect painted in the last three centuries".

In common with other Birmingham Group members Southall also practiced a variety of crafts besides painting, including murals, furniture decoration, lace

Lace

Lace is an openwork fabric, patterned with open holes in the work, made by machine or by hand. The holes can be formed via removal of threads or cloth from a previously woven fabric, but more often open spaces are created as part of the lace fabric. Lace-making is an ancient craft. True lace was...

work, book illustration and engraving

Engraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design on to a hard, usually flat surface, by cutting grooves into it. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an intaglio printing plate, of copper or another metal, for printing...

s. Many of his paintings have frames featuring decorative work by his wife or other Birmingham Group figures such as Georgie Gaskin

Georgie Gaskin

Georgina Evelyn Cave Gaskin , known as Georgie Gaskin, was an English jewellery and metalwork designer....

or Charles Gere - such decoration was considered integral to the work of art.

Influence and reputation

As with many Victorian artists, Southall's critical reputation declined through the twentieth century, as he was seen as an backward-looking English artist rendered anachronistic by the rising tide of FrenchFrance

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

modernism

Modernism

Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society...

. Roger Fry

Roger Fry

Roger Eliot Fry was an English artist and art critic, and a member of the Bloomsbury Group. Establishing his reputation as a scholar of the Old Masters, he became an advocate of more recent developments in French painting, to which he gave the name Post-Impressionism...

described him as "a little slightly disgruntled and dyspeptic Quaker artist who does incredible tempera sham Quattrocentro modern sentimental things with a terrible kind of meticulous skill"

With the renewed interest in Victorian art this began to be seen as a misrepresentation. John Russell Taylor

John Russell Taylor

John Russell Taylor is an English critic and author. He is the author of critical studies of British theatre; of critical biographies of such important figures in Anglo-American film as Alfred Hitchcock, Alec Guinness, Orson Welles, Vivien Leigh, and Ingrid Bergman; of Strangers in Paradise: The...

, art critic of The Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

, described him in 1980 as "a natural-born surrealist"; writing that "there is undoubtedly an authentic strangeness in the way he saw things, which comes out most powerfully in his tempera paintings of contemporary life, but also casts a weird light over many of his watercolours ... we are much more likely to find ourselves thinking of Magritte and Balthus

Balthus

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola , best known as Balthus, was an esteemed but controversial Polish-French modern artist....

and Chirico than of anyone nearer to this apparently stick-in-the-mud Arts-and-Craftsman." Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso known as Pablo Ruiz Picasso was a Spanish expatriate painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, and stage designer, one of the greatest and most influential artists of the...

is recorded by Osbert Sitwell

Osbert Sitwell

Sir Francis Osbert Sacheverell Sitwell, 5th Baronet, was an English writer. His elder sister was Dame Edith Louisa Sitwell and his younger brother was Sir Sacheverell Sitwell; like them he devoted his life to art and literature....

as being so impressed by a Southall painting when visiting Violet Gordon-Woodhouse

Violet Gordon-Woodhouse

Violet Gordon-Woodhouse was an acclaimed British harpsichordist and clavichordist, highly influential in bringing both instruments back into fashion.-Family:...

in the 1920s that he tried to buy it on the spot for his private collection.

Far from being isolated from developments on the continent, Southall's reputation was if anything higher in France than in England, with exhibitions at the Salon de Champs-Élysées

Paris Salon

The Salon , or rarely Paris Salon , beginning in 1725 was the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France. Between 1748–1890 it was the greatest annual or biannual art event in the Western world...

and the Salon de Champs-de-Mars from the 1890s onwards, and membership of the Union Internationale des Beaux-Arts et des Lettres in 1910 and the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1925. His most successful exhibition was that at the Galerie Georges Petit

Georges Petit

Georges Petit was a French art dealer, a key figure in the Paris art world and an important promoter and cultivator of Impressionist artists.-Early career:...

in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

- one of the main centres of progressive French art.

Political activism

Southall's interest in radical politics may have been awakened by his uncle George Baker, whose family had a history of radicalism going back to the seventeenth century. Southall's 1885 sketch of John BrightJohn Bright

John Bright , Quaker, was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, associated with Richard Cobden in the formation of the Anti-Corn Law League. He was one of the greatest orators of his generation, and a strong critic of British foreign policy...

addressing a Birmingham political meeting might be taken as an early indication of radical interest.

Southall politics were strongly influenced by the pacifism

Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war and violence. The term "pacifism" was coined by the French peace campaignerÉmile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress inGlasgow in 1901.- Definition :...

of his Quaker faith. His opposition to the tide of jingoism

Jingoism

Jingoism is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as extreme patriotism in the form of aggressive foreign policy. In practice, it is a country's advocation of the use of threats or actual force against other countries in order to safeguard what it perceives as its national interests...

that surrounded the Jameson Raid

Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid was a botched raid on Paul Kruger's Transvaal Republic carried out by a British colonial statesman Leander Starr Jameson and his Rhodesian and Bechuanaland policemen over the New Year weekend of 1895–96...

in 1895 provoked him into political action, and the outbreak of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

in 1914 caused him to switch his allegiance from the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

to the anti-war Independent Labour Party

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party was a socialist political party in Britain established in 1893. The ILP was affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 to 1932, when it voted to leave...

, for whose Birmingham branch he served as secretary from 1914 until 1931.

Southall's obituary in the Birmingham Post

Birmingham Post

The Birmingham Post newspaper was originally published under the name Daily Post in Birmingham, England, in 1857 by John Frederick Feeney. It was the largest selling broadsheet in the West Midlands, though it faced little if any competition in this category. It changed to tabloid size in 2008...

recorded that he was always "an enthusiastic supporter of that Socialism or Communism which William Morris expressed in his News from Nowhere".

Further reading

- Joseph Southall 1861-1944, Artist - Craftsman. Birmingham Art Gallery catalogue, 1980.ISBN 0-7093-0057-3

- George Breeze, Southall, Joseph Edward (1861–1944), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/64535, accessed 14 July 2007.

External links

- Joseph Edward Southall Tate Collection

- Biography for Joseph Edward Southall Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery Information Centre

- Apollo magazine, April 2005 - a review of a Southall retrospective.

- Southall on Victorian Web