.gif)

History of the European Communities (1945-1957)

Encyclopedia

The period saw the first moves towards European unity as the first bodies began to be established in the aftermath of the Second World War. In 1951 the first community, the European Coal and Steel Community

was established and moves on new communities quickly began. Early attempts as military and political unity failed, eventually leading to the Treaties of Rome in 1957.

. Once again, there was a widespread desire amongst European governments to ensure it could never happen again, particularly with the war giving the world nuclear weapon

s and two ideologically opposed superpowers. (See: Cold War

)

In 1946, war-time British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

spoke at the University of Zurich

on "The tragedy of Europe"; in which he called for a "United States of Europe

", to be created on a regional level while strengthening the UN. He described the first step to a "USE" as a "Council of Europe". London would, in 1949, be the location for the signing of the Treaty of London, establishing the separate entity of the Council of Europe

.

In 1948, the Congress of Europe

was convened in the Hague

, under Winston Churchill's chairmanship, by the European unification movements. It was the first time all the movements had come together under one roof and attracted a myriad of statesmen including many who would later become known as founding fathers of the European Union

. The congress discussed the formation of a new Council of Europe and led to the establishment of the European Movement

and the College of Europe

, however it exposed a division between unionist (opposed to a loss of sovereignty) and federalist (desiring a federal Europe) supporters. This unionist-federalist divide was reflected in the establishment of the Council of Europe

in 1949. The Council was designed with two main political bodies, one composed of governments

, the other

of national members of parliament. Based in Strasbourg

, it is an organisation dealing with democracy and human rights

issues (today covering nearly every European state).

With the start of the Cold War

, the Treaty of Brussels

was signed in 1948. It expanded upon the Dunkirk Treaty

which was a military pact between France and the United Kingdom who were concerned about the threat from the USSR following the communist take over in Czechoslovakia

. The new treaty included the Benelux

countries and was to promote cooperation not only in the military matters but in economic, social and cultural spheres. These roles however were rapidly taken over by other organisations. In 1954 it would be amended by the Paris Agreements which created the Western European Union

which would take on European defence and be merged into the EU in later decades. However the signatories of the Brussels treaty quickly realised their common defence was not enough against the USSR. However wider solitary, such as that seen over the Berlin Blockade

in 1949, was seen to provide sufficient deterrent. Hence in 1949 the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation was created. It expanded the Brussels treaty members to include Denmark

, Iceland, Italy

, Norway, Portugal

as well as Canada

and most notably the United States. Military integration in NATO sped up following the first Soviet atomic bomb test

and the start of the Korean War

which prompted a desire for the inclusion of West Germany

.

In the same year as the Brussels treaty, Sweden presented plans for a Scandinavian defence union

(of Sweden

, Denmark and Norway) which would be neutral in regards to the proposed NATO. However due to pressure from the United States, Norway and Denmark joined NATO and the plans collapsed. Although a "‘Scandinavian joint committee for economic cooperation" was established which led to a customs union under the Nordic Council

which held its first meeting in 1953. Similar economic activity was taking place between the Benelux

countries. The Benelux Customs Union became operative between Belgium

, Netherlands and Luxembourg

. During the war, the three governments in exile signed a customs convention between their countries. This followed a monetary agreement which fixed their currencies against each other. This integration would lead to an economic union and the countries cooperating in foreign affairs as the union was out of a desire to strengthen their position as small states. However the Benelux became a precursor and provided ground for later European integration

.

Robert Schuman

Robert Schuman

, as Prime Minister of France 1947-8 and Foreign Minister 1948–53 gradually but completely changed the Gaullist policy in Europe which aimed at weakening Germany and permanently taking over part of its borderlands. He gained increasing support for this policy both in the French Assembly and with European public opinion but it was fiercely opposed both by Gaullists and by Communists, and inside other parties including his own.

On 9 May 1950, the French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman

(on the basis of a text prepared by Schuman's colleagues Paul Reuter

and Bernard Clappier working with Jean Monnet

, Pierre Uri and Etienne Hirsch

) made his Schuman declaration

at the Quai d'Orsay

,. He proposed that: "Franco-German production of coal and steel as a whole be placed under a common High Authority, within the framework of an organisation open to the participation of the other countries of Europe." Such an act was intended to help economic growth and cement peace between France and Germany, who had previously been long time enemies. Coal and steel were particular symbolic as they were the resources necessary to wage war. It would also be a first step to a "European federation

".

The declaration led to the Treaty of Paris (1951)

forming the European Coal and Steel Community

(ECSC), it was formed by "the inner six

": France, Italy, the Benelux

countries (Belgium

, Netherlands and Luxembourg

) together with West Germany

. The United Kingdom refused to participate due to a rejection of supranational authority. The common market was opened on 10 February 1953 for coal, and on 1 May 1953 for steel.

During the existence of the ECSC, steel production would improve and increase fourfold. Coal production however would decline but its technology, safety and environmental quality would improve. ECSC helped deal with crises in the industry and ensured balanced development and distribution of resources. However the treaty, unlike its successors, was designed to expire after 50 years. Therefore, the Community ceased to exist on 2002-07-23 with all its activities and finances being transferred to the European Community.

With the treaty of Paris, the first institutions were created. At its centre was the High Authority (what is now the European Commission

With the treaty of Paris, the first institutions were created. At its centre was the High Authority (what is now the European Commission

), the first ever supranational body which served as the Community's executive, the first president

of which was Jean Monnet. The President was elected by the eight other members he presided over. The nine members were appointed by the member states (two for the larger three states, one for the smaller three) but they did not represent their member states, rather the common interest.

The member states' governments were represented by the Council of Ministers

, the Presidency

of which rotated between each state every three months in alphabetical order. It was added at the request of smaller states, fearing undue influence from the High Authority. Its task was to harmonise the work of national governments with the acts of the High Authority, as well as issue opinions on the work of the Authority when needed. Hence, unlike the modern Council, this body had limited powers as issues relating only to coal and steel were in the Authority's domain, whereas the Council only had to give its consent to decisions outside coal and steel. As a whole, it only scrutinised and advised the executive which was independent.

The Common Assembly, what is now the European Parliament

, was composed of 78 representatives. The Assembly exercised supervisory powers over the executive. The representatives were to be national MPs elected by their Parliaments to the Assembly, or directly elected. Though in practice it was the former as there was no requirement until the Treaties of Rome and no election until 1979

. However, to emphasise that the chamber was not to be that of a traditional international organisation, whereby it would be composed of representatives of national governments, the Treaty of Paris used the term "representatives of the peoples". The Assembly was not originally mentioned in the Schuman Declaration

but put forward by Jean Monnet

on the second day of treaty negotiations. It was still hoped that the Assembly of the Council of Europe would be the active body and the supranational Community would be inserted inside as one of the Council's institutions. The assembly was intended as a democratic counter-weight and check to the High Authority. It had formal powers to sack the High Authority, following investigation of abuse.

The Court of Justice

was to ensure the observation of ECSC law along with the interpretation and application of the Treaty. The Court was composed of seven judges, appointed by common accord of the national governments for six years. There were no requirements that the judges had to be of a certain nationality, simply that they be qualified and that their independence be beyond doubt. The Court was assisted by two Advocates General.

Finally, there was a Consultative Committee (what is now the Economic and Social Committee

) which had between 30 and 50 members, equally divided between producers, workers, consumers and dealers in the coal and steel sector. This grouping provided a chamber of professional associations for civil society and was in permanent dialogue with the High Authority on policy and proposals for legislation. Its Opinions were necessary before such action could take place. The threefold division of its members prevented any one group, whether business, labour or consumers, from dominating proceedings, as majority voting was required. Its existence curtailed the activity of lobbyists acting to influence governments on such policy. The Consultative Committee had an important action in controlling the budget and expenditures, drawn from the first European tax on coal and steel producers. The Community money was spent on re-employment and social housing activities within the sectors concerned.

Members were appointed for two years and were not bound by any mandate or instruction of the organisations which appointed them. The Committee had a plenary assembly, bureau and a president. The High Authority was obliged to consult the committee in certain cases where it was appropriate and to keep it informed.

of the new community. The treaties allowed for the seat(s) to be decided by common accord of governments yet at a conference of the ECSC members on 23 July 1952 no permanent seat was decided. The seat was contested with Liège

, Luxembourg, Strasbourg

and Turin

all considered. While Saarbrücken

had a status as a "European city", the ongoing dispute over Saarland

made it a problematic choice. Brussels

would have been accepted at the time, but divisions within the then-unstable Belgian government ruled that option out.

To break the deadlock, Joseph Bech, then Prime Minister of Luxembourg, proposed that Luxembourg be made the provisional seat of the institutions until a permanent agreement was reached. However, it was decided that the Common Assembly, which became the Parliament, should instead be based in Strasbourg—the Council of Europe

(CoE) was already based there, in the House of Europe. The chamber of the CoE's Parliamentary Assembly could also serve the Common Assembly, and they did so until 1999, when a new complex of buildings

was built across the river from the Palace.

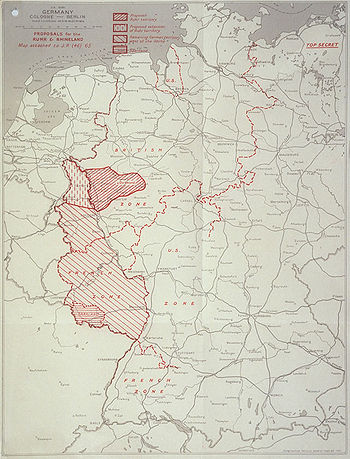

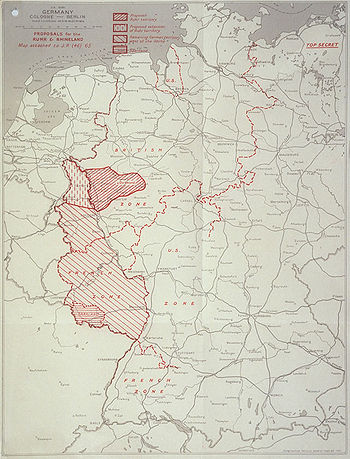

The early French plans were concerned with keeping Germany weak and strengthening the French economy at the expense of that of Germany. (see the Monnet plan

The early French plans were concerned with keeping Germany weak and strengthening the French economy at the expense of that of Germany. (see the Monnet plan

) French foreign policy aimed at dismantling German heavy industry, place the coal rich Ruhr area

and Rhineland

under French control or at a minimum internationalize them, and also to join the coal rich Saarland

with the iron rich province of Lorraine

(which had been handed over from Germany to France again in 1944). When American diplomats reminded the French of what a devastating effect this would have on the German economy, France's response was to suggest the Germans would just have to "make [the] necessary adjustments" to deal with the inevitable foreign exchange deficit"."

At the 1945 Potsdam Conference

the U.S. was operating under the Morgenthau plan

, as a consequence large parts of German industry were to be dismantled.

According to some historians the U.S. government abandoned the Morgenthau plan as policy in September 1946 with Secretary of State James F. Byrnes

' speech Restatement of Policy on Germany

. Others have argued that credit should be given to former U.S.President Herbert Hoover

who in one of his reports from Germany

, dated 18 March 1947, argued for a change in occupation policy, amongst other things stating:

Worries about the sluggish recovery of the European economy, which before the war had depended on the German industrial base, and growing Soviet influence amongst a German population subject to food shortages and economic misery, caused the Joint Chiefs of Staff

, and Generals Clay

and Marshall

to start lobbying the Truman

administration for a change of policy. General Clay stated

In July 1947, President Harry S. Truman

rescinded on "national security grounds" the punitive occupation directive JCS 1067, which had directed the U.S. forces of occupation in Germany to "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany [or] designed to maintain or strengthen the German economy", it was replaced by JCS 1779, which instead noted that "[a]n orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany." It took over two months for General Clay to overcome continued resistance to the new U.S. occupation directive JCS 1779, but on 10 July 1947, it was finally approved at a meeting of the SWNCC

. The final version of the document "was purged of the most important elements of the Morgenthau plan."

The dismantling of the German heavy industry was in its later stages supported mainly by France, the Petersberg Agreement

of November 1949 reduced the levels vastly, though dismantling of minor German factories continued until 1951. The final limitations on German industrial levels were lifted after the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951, though arms manufacture remained prohibited. With U.S. support, (as given in the September 1946 Stuttgart Speech), France in 1947 turned the coal rich Saarland into the Saar protectorate

and integrated it into the French economy. The Franco-German conflict over the Saarland was later to prove one of the major hurdles to the integration of the European communities.

The Ruhr Agreement was imposed on the Germans as a condition for permitting them to establish the Federal Republic of Germany. By controlling the production and distribution of coal and steel (i.e. how much coal and steel the Germans themselves would get), the International Authority for the Ruhr

in effect controlled the entire West German economy, much to the dismay of the Germans. They were however permitted to send their delegations to the authority after the Petersberg agreement. With the West German agreement to join the European Coal and Steel Community in order to lift the restrictions imposed by the IAR, thus also ensuring French security by perpetuating French access to Ruhr coal, the role of the IAR was taken over by the ECSC.

in the Saar with wide ranging powers. Parties advocating a return of the Saar to Germany were banned, with the consequence that West Germany did not recognise the democratic legality of the Saar government. In view of continued conflict between Germany and France over the future of the Saarland efforts were made by the other Western European nations to find a solution to the potentially dangerous problem. Placed under increasing international pressure France finally agreed to a compromise. The Saar territory was to be Europeanised under the context of the Western European Union

. France and Germany agreed in the Paris Agreements that until a peace treaty was signed with Germany, the Saar area would be governed under a "statute" that was to be supervised by a European Commission

er who in turn would be responsible to the Council of Ministers

of the Western European Union. The Saarland would however have to remain in economic union with France.

Despite the endorsement of the statute by West Germany, in the 1955 referendum amongst the Saarlanders that was needed for it to come into effect the statute was rejected by 67.7% of the population. Despite French pre-referendum assertions that a no to the statute would simply result in the Saarland remaining in its previous status as a French controlled territory, the claim of the campaign group for a "no" to the statute that it would lead to unification with West Germany turned out to be correct. The Saarland was politically reintegrated with West Germany in 1 January 1957, but economic reintegration took many additional years. In return for agreeing to return the Saar France demanded and gained the following concessions: France was permitted to extract coal from the Warndt coal deposit until 1981. Germany had to agree to the channelisation of the Moselle. This reduced French freight costs in the Lorraine steel industry. Germany had to agree to the teaching of French as the first foreign language in schools in the Saarland. Although no longer binding, the agreement is still in the main followed.

Following on the heels of the creation of the ECSC, the European Defence Community

Following on the heels of the creation of the ECSC, the European Defence Community

(EDC) was drawn up and signed on 27 May 1952. It would combine national armies and allow West Germany to rearm under the control of the new Community. However in 1954, the treaty was rejected by the French National Assembly

. The rejection also derailed further plans for a European Political Community

, being drawn up by members of the Common Assembly which would have created a federation to ensure democratic control over the future European army

. In response to the rejection of the EDC, Jean Monnet

resigned as President of the High Authority and began work on new integration efforts in the field of the economy. In 1955, the Council of Europe

adopted an emblem for all Europe, twelve golden stars in a circle upon a blue field. It would later be adopted by the European Communities

In 1956, the Egypt

ian government under Gamal Abdel Nasser

nationalised the Suez canal

and closing it to Israel

i traffic, sparking the Suez Crisis

. This was in response to the withdrawal of funding for the Aswan Dam

by the UK and United States due to Egypt's ties to the Soviet Union

. The canal was owned by the UK and French investors and had been a neutral zone under British control. The nationalisation and closure to Israeli traffic prompted a military response by the UK, France and Israel, a move opposed by the United States. It was a military success but a political disaster for the UK and France. The UK in particular saw it could not operate alone, instead turning to the US, and it also prompted the next British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan

, to look towards joining the European Community. Equally France saw its future with the Community but opposed British entry, with then French President Charles de Gaulle

stating he would veto

British entry out of a fear it would lead to US domination.

During the war, Israel gained the Sinai Peninsula

and a UN force guarded the border. However shortly after the UN force was expelled and a Six-Day War

broke out between Israeli and its Arab neighbours. This in turn sparked the 1967 Oil Embargo

which cut off or limited oils supplies to various Israel and the west. Europe was hit especially bad, due mainly to a lack of solidarity and uniformity in embargoing specific countries. As a result of the crisis, the Common Assembly proposed extending the powers of the ECSC to cover other sources of energy. However Jean Monnet desired a separate community to cover nuclear power

and Louis Armand

was put in charge of a study into the prospects of nuclear energy use in Europe. The report concluded further nuclear development was needed to fill the deficit left by the exhaustion of coal deposits and to reduce dependence on oil producers. However the Benelux states and Germany were also keen on creating a general common market

, although it was opposed by France due to its protectionism

and Jean Monnet thought it too large and difficult a task. In the end, Monnet proposed the creating of both, as separate communities, to reconcile both groups.

As a result of the Messina Conference

of 1955, Paul-Henri Spaak

was appointed as chairman of a preparatory committee (Spaak Committee

) charged with the preparation of a report on the creation of a common European market.

The Spaak Report

drawn up by the Spaak Committee provided the basis for further progress and was accepted at the Venice Conference

(29 and 30 May 1956) where the decision was taken to organize an Intergovernmental Conference

. The report formed the cornerstone of the Intergovernmental Conference on the Common Market and Euratom

at Val Duchesse

in 1956. The outcome of the conference was that new communities would share the Common Assembly (now Parliamentary Assembly) with the ECSC, as it would with the Court of Justice

. However they would not share the ECSC's Council of High Authority. The two new High Authorities would be called Commissions, this was due to a reduction in their powers. France was reluctant to agree to more supranational powers and hence the new Commissions would only have basic powers and important decisions would have to be approved by the Council, which now adopted majority voting. Thus, on 25 March 1957, the Treaties of Rome were signed. They came into force on 1958-01-01 establishing the European Economic Community

(EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community

(Euratom). The latter body fostered co-operation in the nuclear field, at the time a very popular area, and the EEC was to create a full customs union between members. Louis Armand became the first President of Euratom Commission and Walter Hallstein

became the first President of the EEC Commission.

Organisation for European Economic Cooperation

Hungarian Revolution of 1956

European Youth Campaign

European Coal and Steel Community

The European Coal and Steel Community was a six-nation international organisation serving to unify Western Europe during the Cold War and create the foundation for the modern-day developments of the European Union...

was established and moves on new communities quickly began. Early attempts as military and political unity failed, eventually leading to the Treaties of Rome in 1957.

Beginnings of cooperation

The Second World War from 1939 to 1945 saw an unprecedented human and economic cost, in which Europe was affected particularly severely through the totality of modern warfare and large scale massacres such as the HolocaustThe Holocaust

The Holocaust , also known as the Shoah , was the genocide of approximately six million European Jews and millions of others during World War II, a programme of systematic state-sponsored murder by Nazi...

. Once again, there was a widespread desire amongst European governments to ensure it could never happen again, particularly with the war giving the world nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

s and two ideologically opposed superpowers. (See: Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

)

In 1946, war-time British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

spoke at the University of Zurich

University of Zurich

The University of Zurich , located in the city of Zurich, is the largest university in Switzerland, with over 25,000 students. It was founded in 1833 from the existing colleges of theology, law, medicine and a new faculty of philosophy....

on "The tragedy of Europe"; in which he called for a "United States of Europe

United States of Europe

Since the 1950s, European integration has seen the development of a supranational system of governance, as its institutions move further from the concept of simple intergovernmentalism. However, with the Maastricht Treaty of 1993, new intergovernmental elements have been introduced alongside the...

", to be created on a regional level while strengthening the UN. He described the first step to a "USE" as a "Council of Europe". London would, in 1949, be the location for the signing of the Treaty of London, establishing the separate entity of the Council of Europe

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe is an international organisation promoting co-operation between all countries of Europe in the areas of legal standards, human rights, democratic development, the rule of law and cultural co-operation...

.

In 1948, the Congress of Europe

Hague Congress (1948)

The Hague Congress was held in the Congress of Europe in Hague from 7–11 May 1948 with 750 delegates participating from around Europe as well as observers from Canada and the United States....

was convened in the Hague

The Hague

The Hague is the capital city of the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. With a population of 500,000 inhabitants , it is the third largest city of the Netherlands, after Amsterdam and Rotterdam...

, under Winston Churchill's chairmanship, by the European unification movements. It was the first time all the movements had come together under one roof and attracted a myriad of statesmen including many who would later become known as founding fathers of the European Union

Founding fathers of the European Union

The Founding Fathers of the European Union are a number of men who have been recognised as making a major contribution to the development of European unity and what is now the European Union. There is no official list of founding fathers or a single event defining them so some ideas vary.-Europe's...

. The congress discussed the formation of a new Council of Europe and led to the establishment of the European Movement

European Movement

The European Movement International is a lobbying association that coordinates the efforts of associations and national councils with the goal of promoting European integration, and disseminating information about it.-History:...

and the College of Europe

College of Europe

The College of Europe is an independent university institute of postgraduate European studies with the main campus in Bruges, Belgium...

, however it exposed a division between unionist (opposed to a loss of sovereignty) and federalist (desiring a federal Europe) supporters. This unionist-federalist divide was reflected in the establishment of the Council of Europe

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe is an international organisation promoting co-operation between all countries of Europe in the areas of legal standards, human rights, democratic development, the rule of law and cultural co-operation...

in 1949. The Council was designed with two main political bodies, one composed of governments

Committee of Ministers

The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe or commonly the Committee of Ministers is the Council of Europe's decision-making body. It comprises the Foreign Affairs Ministers of all the member states, or their permanent diplomatic representatives in Strasbourg...

, the other

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe , which held its first session in Strasbourg on 10 August 1949, can be considered the oldest international parliamentary assembly with a pluralistic composition of democratically elected members of parliament established on the basis of an...

of national members of parliament. Based in Strasbourg

Strasbourg

Strasbourg is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in eastern France and is the official seat of the European Parliament. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capital of the Bas-Rhin département. The city and the region of Alsace are historically German-speaking,...

, it is an organisation dealing with democracy and human rights

Human rights

Human rights are "commonly understood as inalienable fundamental rights to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being." Human rights are thus conceived as universal and egalitarian . These rights may exist as natural rights or as legal rights, in both national...

issues (today covering nearly every European state).

With the start of the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

, the Treaty of Brussels

Treaty of Brussels

The Treaty of Brussels was signed on 17 March 1948 between Belgium, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, as an expansion to the preceding year's defence pledge, the Dunkirk Treaty signed between Britain and France...

was signed in 1948. It expanded upon the Dunkirk Treaty

Dunkirk Treaty

The Treaty of Dunkirk was signed on 4 March 1947, between France and the United Kingdom in Dunkirk as a Treaty of Alliance and Mutual Assistance against a possible German attack in the aftermath of World War II. The Dunkirk Treaty entered into force on 8 September 1947 and it preceded the Treaty...

which was a military pact between France and the United Kingdom who were concerned about the threat from the USSR following the communist take over in Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

. The new treaty included the Benelux

Benelux

The Benelux is an economic union in Western Europe comprising three neighbouring countries, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. These countries are located in northwestern Europe between France and Germany...

countries and was to promote cooperation not only in the military matters but in economic, social and cultural spheres. These roles however were rapidly taken over by other organisations. In 1954 it would be amended by the Paris Agreements which created the Western European Union

Western European Union

The Western European Union was an international organisation tasked with implementing the Modified Treaty of Brussels , an amended version of the original 1948 Treaty of Brussels...

which would take on European defence and be merged into the EU in later decades. However the signatories of the Brussels treaty quickly realised their common defence was not enough against the USSR. However wider solitary, such as that seen over the Berlin Blockade

Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War and the first resulting in casualties. During the multinational occupation of post-World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway and road access to the sectors of Berlin under Allied...

in 1949, was seen to provide sufficient deterrent. Hence in 1949 the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation was created. It expanded the Brussels treaty members to include Denmark

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

, Iceland, Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, Norway, Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

as well as Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

and most notably the United States. Military integration in NATO sped up following the first Soviet atomic bomb test

Joe 1

The RDS-1 , also known as First Lightning , was the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test. In the west, it was code-named Joe-1, in reference to Joseph Stalin. It was test-exploded on 29 August 1949, at Semipalatinsk, Kazakh SSR, after a top-secret R&D project...

and the start of the Korean War

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

which prompted a desire for the inclusion of West Germany

West Germany

West Germany is the common English, but not official, name for the Federal Republic of Germany or FRG in the period between its creation in May 1949 to German reunification on 3 October 1990....

.

In the same year as the Brussels treaty, Sweden presented plans for a Scandinavian defence union

Scandinavian defence union

A Scandinavian defence union between Sweden, Norway, Finland and Denmark was planned after the end of World War II. Finland had fought two wars against the Soviet Union, Denmark and Norway had been occupied by Germany between 1940 and 1945, and Sweden, having been a neutral state throughout the...

(of Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

, Denmark and Norway) which would be neutral in regards to the proposed NATO. However due to pressure from the United States, Norway and Denmark joined NATO and the plans collapsed. Although a "‘Scandinavian joint committee for economic cooperation" was established which led to a customs union under the Nordic Council

Nordic Council

The Nordic Council is a geo-political, inter-parliamentary forum for co-operation between the Nordic countries. It was established following World War II and its first concrete result was the introduction in 1952 of a common labour market and free movement across borders without passports for the...

which held its first meeting in 1953. Similar economic activity was taking place between the Benelux

Benelux

The Benelux is an economic union in Western Europe comprising three neighbouring countries, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. These countries are located in northwestern Europe between France and Germany...

countries. The Benelux Customs Union became operative between Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

, Netherlands and Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Luxembourg , officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg , is a landlocked country in western Europe, bordered by Belgium, France, and Germany. It has two principal regions: the Oesling in the North as part of the Ardennes massif, and the Gutland in the south...

. During the war, the three governments in exile signed a customs convention between their countries. This followed a monetary agreement which fixed their currencies against each other. This integration would lead to an economic union and the countries cooperating in foreign affairs as the union was out of a desire to strengthen their position as small states. However the Benelux became a precursor and provided ground for later European integration

European integration

European integration is the process of industrial, political, legal, economic integration of states wholly or partially in Europe...

.

Coal and Steel

Robert Schuman

Robert Schuman was a noted Luxembourgish-born French statesman. Schuman was a Christian Democrat and an independent political thinker and activist...

, as Prime Minister of France 1947-8 and Foreign Minister 1948–53 gradually but completely changed the Gaullist policy in Europe which aimed at weakening Germany and permanently taking over part of its borderlands. He gained increasing support for this policy both in the French Assembly and with European public opinion but it was fiercely opposed both by Gaullists and by Communists, and inside other parties including his own.

On 9 May 1950, the French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman

Robert Schuman

Robert Schuman was a noted Luxembourgish-born French statesman. Schuman was a Christian Democrat and an independent political thinker and activist...

(on the basis of a text prepared by Schuman's colleagues Paul Reuter

Paul Reuter

Paul Julius Freiherr von Reuter was a German entrepreneur and later naturalized British citizen...

and Bernard Clappier working with Jean Monnet

Jean Monnet

Jean Omer Marie Gabriel Monnet was a French political economist and diplomat. He is regarded by many as a chief architect of European Unity and is regarded as one of its founding fathers...

, Pierre Uri and Etienne Hirsch

Étienne Hirsch

Étienne Hirsch was a French civil engineer and administrator who served as President of the Commission of the European Atomic Energy Community between 1959–1962 .*...

) made his Schuman declaration

Schuman Declaration

The Schuman Declaration of 9 May 1950 was a governmental proposal by then-French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman to create a new form of organization of States in Europe called a supranational Community. Following the experiences of two world wars, France recognized that certain values such as...

at the Quai d'Orsay

Quai d'Orsay

The Quai d'Orsay is a quai in the VIIe arrondissement of Paris, part of the left bank of the Seine, and the name of the street along it. The Quai becomes the Quai Anatole France east of the Palais Bourbon, and the Quai de Branly west of the Pont de l'Alma.The French Ministry of Foreign Affairs is...

,. He proposed that: "Franco-German production of coal and steel as a whole be placed under a common High Authority, within the framework of an organisation open to the participation of the other countries of Europe." Such an act was intended to help economic growth and cement peace between France and Germany, who had previously been long time enemies. Coal and steel were particular symbolic as they were the resources necessary to wage war. It would also be a first step to a "European federation

United States of Europe

Since the 1950s, European integration has seen the development of a supranational system of governance, as its institutions move further from the concept of simple intergovernmentalism. However, with the Maastricht Treaty of 1993, new intergovernmental elements have been introduced alongside the...

".

The declaration led to the Treaty of Paris (1951)

Treaty of Paris (1951)

The Treaty of Paris was signed on 18 April 1951 between France, West Germany, Italy and the three Benelux countries , establishing the European Coal and Steel Community , which subsequently became part of the European Union...

forming the European Coal and Steel Community

European Coal and Steel Community

The European Coal and Steel Community was a six-nation international organisation serving to unify Western Europe during the Cold War and create the foundation for the modern-day developments of the European Union...

(ECSC), it was formed by "the inner six

Inner Six

The Inner Six, or simply The Six, are the six founding member states of the European Communities. This was in contrast to the outer seven who formed the European Free Trade Association rather than be involved in supranational European integration .-History:The inner six are those who responded to...

": France, Italy, the Benelux

Benelux

The Benelux is an economic union in Western Europe comprising three neighbouring countries, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. These countries are located in northwestern Europe between France and Germany...

countries (Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

, Netherlands and Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Luxembourg , officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg , is a landlocked country in western Europe, bordered by Belgium, France, and Germany. It has two principal regions: the Oesling in the North as part of the Ardennes massif, and the Gutland in the south...

) together with West Germany

West Germany

West Germany is the common English, but not official, name for the Federal Republic of Germany or FRG in the period between its creation in May 1949 to German reunification on 3 October 1990....

. The United Kingdom refused to participate due to a rejection of supranational authority. The common market was opened on 10 February 1953 for coal, and on 1 May 1953 for steel.

During the existence of the ECSC, steel production would improve and increase fourfold. Coal production however would decline but its technology, safety and environmental quality would improve. ECSC helped deal with crises in the industry and ensured balanced development and distribution of resources. However the treaty, unlike its successors, was designed to expire after 50 years. Therefore, the Community ceased to exist on 2002-07-23 with all its activities and finances being transferred to the European Community.

First institutions

European Commission

The European Commission is the executive body of the European Union. The body is responsible for proposing legislation, implementing decisions, upholding the Union's treaties and the general day-to-day running of the Union....

), the first ever supranational body which served as the Community's executive, the first president

President of the European Commission

The President of the European Commission is the head of the European Commission ― the executive branch of the :European Union ― the most powerful officeholder in the EU. The President is responsible for allocating portfolios to members of the Commission and can reshuffle or dismiss them if needed...

of which was Jean Monnet. The President was elected by the eight other members he presided over. The nine members were appointed by the member states (two for the larger three states, one for the smaller three) but they did not represent their member states, rather the common interest.

The member states' governments were represented by the Council of Ministers

Council of the European Union

The Council of the European Union is the institution in the legislature of the European Union representing the executives of member states, the other legislative body being the European Parliament. The Council is composed of twenty-seven national ministers...

, the Presidency

Presidency of the Council of the European Union

The Presidency of the Council of the European Union is the responsibility for the functioning of the Council of the European Union that rotates between the member states of the European Union every six months. The presidency is not a single president but rather the task is undertaken by a national...

of which rotated between each state every three months in alphabetical order. It was added at the request of smaller states, fearing undue influence from the High Authority. Its task was to harmonise the work of national governments with the acts of the High Authority, as well as issue opinions on the work of the Authority when needed. Hence, unlike the modern Council, this body had limited powers as issues relating only to coal and steel were in the Authority's domain, whereas the Council only had to give its consent to decisions outside coal and steel. As a whole, it only scrutinised and advised the executive which was independent.

The Common Assembly, what is now the European Parliament

European Parliament

The European Parliament is the directly elected parliamentary institution of the European Union . Together with the Council of the European Union and the Commission, it exercises the legislative function of the EU and it has been described as one of the most powerful legislatures in the world...

, was composed of 78 representatives. The Assembly exercised supervisory powers over the executive. The representatives were to be national MPs elected by their Parliaments to the Assembly, or directly elected. Though in practice it was the former as there was no requirement until the Treaties of Rome and no election until 1979

European Parliament election, 1979

The 1979 European elections were parliamentary elections held across all 9 European Community member states. They were the first European elections to be held, allowing citizens to elect 410 MEPs to the European Parliament, and also the first international election in history.Seats in the...

. However, to emphasise that the chamber was not to be that of a traditional international organisation, whereby it would be composed of representatives of national governments, the Treaty of Paris used the term "representatives of the peoples". The Assembly was not originally mentioned in the Schuman Declaration

Schuman Declaration

The Schuman Declaration of 9 May 1950 was a governmental proposal by then-French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman to create a new form of organization of States in Europe called a supranational Community. Following the experiences of two world wars, France recognized that certain values such as...

but put forward by Jean Monnet

Jean Monnet

Jean Omer Marie Gabriel Monnet was a French political economist and diplomat. He is regarded by many as a chief architect of European Unity and is regarded as one of its founding fathers...

on the second day of treaty negotiations. It was still hoped that the Assembly of the Council of Europe would be the active body and the supranational Community would be inserted inside as one of the Council's institutions. The assembly was intended as a democratic counter-weight and check to the High Authority. It had formal powers to sack the High Authority, following investigation of abuse.

The Court of Justice

European Court of Justice

The Court can sit in plenary session, as a Grand Chamber of 13 judges, or in chambers of three or five judges. Plenary sitting are now very rare, and the court mostly sits in chambers of three or five judges...

was to ensure the observation of ECSC law along with the interpretation and application of the Treaty. The Court was composed of seven judges, appointed by common accord of the national governments for six years. There were no requirements that the judges had to be of a certain nationality, simply that they be qualified and that their independence be beyond doubt. The Court was assisted by two Advocates General.

Finally, there was a Consultative Committee (what is now the Economic and Social Committee

Economic and Social Committee

The European Economic and Social Committee is a body of the European Union established in 1958. It is a consultative assembly composed of employers , employees and representatives of various other interests...

) which had between 30 and 50 members, equally divided between producers, workers, consumers and dealers in the coal and steel sector. This grouping provided a chamber of professional associations for civil society and was in permanent dialogue with the High Authority on policy and proposals for legislation. Its Opinions were necessary before such action could take place. The threefold division of its members prevented any one group, whether business, labour or consumers, from dominating proceedings, as majority voting was required. Its existence curtailed the activity of lobbyists acting to influence governments on such policy. The Consultative Committee had an important action in controlling the budget and expenditures, drawn from the first European tax on coal and steel producers. The Community money was spent on re-employment and social housing activities within the sectors concerned.

Members were appointed for two years and were not bound by any mandate or instruction of the organisations which appointed them. The Committee had a plenary assembly, bureau and a president. The High Authority was obliged to consult the committee in certain cases where it was appropriate and to keep it informed.

Provisional seats

The treaty however made no decision on where to base the institutionsLocation of European Union institutions

The governing institutions of the European Union are not concentrated in a single capital city; they are instead spread across three cities with other EU agencies and bodies based further away...

of the new community. The treaties allowed for the seat(s) to be decided by common accord of governments yet at a conference of the ECSC members on 23 July 1952 no permanent seat was decided. The seat was contested with Liège

Liège

Liège is a major city and municipality of Belgium located in the province of Liège, of which it is the economic capital, in Wallonia, the French-speaking region of Belgium....

, Luxembourg, Strasbourg

Strasbourg

Strasbourg is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in eastern France and is the official seat of the European Parliament. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capital of the Bas-Rhin département. The city and the region of Alsace are historically German-speaking,...

and Turin

Turin

Turin is a city and major business and cultural centre in northern Italy, capital of the Piedmont region, located mainly on the left bank of the Po River and surrounded by the Alpine arch. The population of the city proper is 909,193 while the population of the urban area is estimated by Eurostat...

all considered. While Saarbrücken

Saarbrücken

Saarbrücken is the capital of the state of Saarland in Germany. The city is situated at the heart of a metropolitan area that borders on the west on Dillingen and to the north-east on Neunkirchen, where most of the people of the Saarland live....

had a status as a "European city", the ongoing dispute over Saarland

Saar (protectorate)

The Saar Protectorate was a German borderland territory twice temporarily made a protectorate state. Since rejoining Germany the second time in 1957, it is the smallest Federal German Area State , the Saarland, not counting the city-states Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen...

made it a problematic choice. Brussels

Brussels

Brussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

would have been accepted at the time, but divisions within the then-unstable Belgian government ruled that option out.

To break the deadlock, Joseph Bech, then Prime Minister of Luxembourg, proposed that Luxembourg be made the provisional seat of the institutions until a permanent agreement was reached. However, it was decided that the Common Assembly, which became the Parliament, should instead be based in Strasbourg—the Council of Europe

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe is an international organisation promoting co-operation between all countries of Europe in the areas of legal standards, human rights, democratic development, the rule of law and cultural co-operation...

(CoE) was already based there, in the House of Europe. The chamber of the CoE's Parliamentary Assembly could also serve the Common Assembly, and they did so until 1999, when a new complex of buildings

Seat of the European Parliament in Strasbourg

The city of Strasbourg is the official seat of the European Parliament. The institution is legally bound to meet there twelve sessions a year lasting about four days each. Other work takes place in Brussels and Luxembourg City...

was built across the river from the Palace.

Germany

Monnet Plan

The Monnet plan was proposed by French civil servant Jean Monnet after the end of World War II. It was a reconstruction plan for France that proposed giving France control over the German coal and steel areas of the Ruhr area and Saar and using these resources to bring France to 150% of pre-war...

) French foreign policy aimed at dismantling German heavy industry, place the coal rich Ruhr area

Ruhr Area

The Ruhr, by German-speaking geographers and historians more accurately called Ruhr district or Ruhr region , is an urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With 4435 km² and a population of some 5.2 million , it is the largest urban agglomeration in Germany...

and Rhineland

Rhineland

Historically, the Rhinelands refers to a loosely-defined region embracing the land on either bank of the River Rhine in central Europe....

under French control or at a minimum internationalize them, and also to join the coal rich Saarland

Saarland

Saarland is one of the sixteen states of Germany. The capital is Saarbrücken. It has an area of 2570 km² and 1,045,000 inhabitants. In both area and population, it is the smallest state in Germany other than the city-states...

with the iron rich province of Lorraine

Lorraine (province)

The Duchy of Upper Lorraine was an historical duchy roughly corresponding with the present-day northeastern Lorraine region of France, including parts of modern Luxembourg and Germany. The main cities were Metz, Verdun, and the historic capital Nancy....

(which had been handed over from Germany to France again in 1944). When American diplomats reminded the French of what a devastating effect this would have on the German economy, France's response was to suggest the Germans would just have to "make [the] necessary adjustments" to deal with the inevitable foreign exchange deficit"."

At the 1945 Potsdam Conference

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

the U.S. was operating under the Morgenthau plan

Morgenthau Plan

The Morgenthau Plan, proposed by United States Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr., advocated that the Allied occupation of Germany following World War II include measures to eliminate Germany's ability to wage war.-Overview:...

, as a consequence large parts of German industry were to be dismantled.

According to some historians the U.S. government abandoned the Morgenthau plan as policy in September 1946 with Secretary of State James F. Byrnes

James F. Byrnes

James Francis Byrnes was an American statesman from the state of South Carolina. During his career, Byrnes served as a member of the House of Representatives , as a Senator , as Justice of the Supreme Court , as Secretary of State , and as the 104th Governor of South Carolina...

' speech Restatement of Policy on Germany

Restatement of Policy on Germany

"Restatement of Policy on Germany" is a famous speech by James F. Byrnes, the United States Secretary of State, held in Stuttgart on September 6, 1946.Also known as the "Speech of hope" it set the tone of future U.S...

. Others have argued that credit should be given to former U.S.President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

who in one of his reports from Germany

The President's Economic Mission to Germany and Austria

The President's Economic Mission to Germany and Austria was a series of reports commissioned by US President Harry S. Truman and written by former US President Herbert Hoover....

, dated 18 March 1947, argued for a change in occupation policy, amongst other things stating:

- "There is the illusion that the New Germany left after the annexations can be reduced to a 'pastoral state'. It cannot be done unless we exterminate or move 25,000,000 people out of it."

Worries about the sluggish recovery of the European economy, which before the war had depended on the German industrial base, and growing Soviet influence amongst a German population subject to food shortages and economic misery, caused the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff is a body of senior uniformed leaders in the United States Department of Defense who advise the Secretary of Defense, the Homeland Security Council, the National Security Council and the President on military matters...

, and Generals Clay

Lucius D. Clay

General Lucius Dubignon Clay was an American officer and military governor of the United States Army known for his administration of Germany immediately after World War II. Clay was deputy to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1945; deputy military governor, Germany 1946; commander in chief, U.S....

and Marshall

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall was an American military leader, Chief of Staff of the Army, Secretary of State, and the third Secretary of Defense...

to start lobbying the Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

administration for a change of policy. General Clay stated

- "There is no choice between being a communist on 1,500 calories a day and a believer in democracy on a thousand".

In July 1947, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

rescinded on "national security grounds" the punitive occupation directive JCS 1067, which had directed the U.S. forces of occupation in Germany to "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany [or] designed to maintain or strengthen the German economy", it was replaced by JCS 1779, which instead noted that "[a]n orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany." It took over two months for General Clay to overcome continued resistance to the new U.S. occupation directive JCS 1779, but on 10 July 1947, it was finally approved at a meeting of the SWNCC

SWNCC

The State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee was a United States federal government committee created in December 1944 to address the political-military issues involved in the occupation of the Axis powers following the end of World War II....

. The final version of the document "was purged of the most important elements of the Morgenthau plan."

The dismantling of the German heavy industry was in its later stages supported mainly by France, the Petersberg Agreement

Petersberg agreement

The Petersberg Agreement is an international treaty that extended the rights of the Federal Government of Germany vis-a-vis the occupying forces of Britain, France, and the United States, and is viewed as the first major step of Federal Republic of Germany towards sovereignty...

of November 1949 reduced the levels vastly, though dismantling of minor German factories continued until 1951. The final limitations on German industrial levels were lifted after the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951, though arms manufacture remained prohibited. With U.S. support, (as given in the September 1946 Stuttgart Speech), France in 1947 turned the coal rich Saarland into the Saar protectorate

Saar (protectorate)

The Saar Protectorate was a German borderland territory twice temporarily made a protectorate state. Since rejoining Germany the second time in 1957, it is the smallest Federal German Area State , the Saarland, not counting the city-states Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen...

and integrated it into the French economy. The Franco-German conflict over the Saarland was later to prove one of the major hurdles to the integration of the European communities.

The Ruhr Agreement was imposed on the Germans as a condition for permitting them to establish the Federal Republic of Germany. By controlling the production and distribution of coal and steel (i.e. how much coal and steel the Germans themselves would get), the International Authority for the Ruhr

International Authority for the Ruhr

The International Authority for the Ruhr was an international body established in 1949 by the Allied powers to control the coal and steel industry of the Ruhr Area in West Germany....

in effect controlled the entire West German economy, much to the dismay of the Germans. They were however permitted to send their delegations to the authority after the Petersberg agreement. With the West German agreement to join the European Coal and Steel Community in order to lift the restrictions imposed by the IAR, thus also ensuring French security by perpetuating French access to Ruhr coal, the role of the IAR was taken over by the ECSC.

The Europeanisation of the Saarland

France had broken off the coal rich Saar from Germany and made it into a protectorate, economically integrated with France and nominally politically independent although security and foreign policy was dictated from France. In addition, France maintained a High CommissionerHigh Commissioner

High Commissioner is the title of various high-ranking, special executive positions held by a commission of appointment.The English term is also used to render various equivalent titles in other languages.-Bilateral diplomacy:...

in the Saar with wide ranging powers. Parties advocating a return of the Saar to Germany were banned, with the consequence that West Germany did not recognise the democratic legality of the Saar government. In view of continued conflict between Germany and France over the future of the Saarland efforts were made by the other Western European nations to find a solution to the potentially dangerous problem. Placed under increasing international pressure France finally agreed to a compromise. The Saar territory was to be Europeanised under the context of the Western European Union

Western European Union

The Western European Union was an international organisation tasked with implementing the Modified Treaty of Brussels , an amended version of the original 1948 Treaty of Brussels...

. France and Germany agreed in the Paris Agreements that until a peace treaty was signed with Germany, the Saar area would be governed under a "statute" that was to be supervised by a European Commission

European Commission

The European Commission is the executive body of the European Union. The body is responsible for proposing legislation, implementing decisions, upholding the Union's treaties and the general day-to-day running of the Union....

er who in turn would be responsible to the Council of Ministers

Council of the European Union

The Council of the European Union is the institution in the legislature of the European Union representing the executives of member states, the other legislative body being the European Parliament. The Council is composed of twenty-seven national ministers...

of the Western European Union. The Saarland would however have to remain in economic union with France.

Despite the endorsement of the statute by West Germany, in the 1955 referendum amongst the Saarlanders that was needed for it to come into effect the statute was rejected by 67.7% of the population. Despite French pre-referendum assertions that a no to the statute would simply result in the Saarland remaining in its previous status as a French controlled territory, the claim of the campaign group for a "no" to the statute that it would lead to unification with West Germany turned out to be correct. The Saarland was politically reintegrated with West Germany in 1 January 1957, but economic reintegration took many additional years. In return for agreeing to return the Saar France demanded and gained the following concessions: France was permitted to extract coal from the Warndt coal deposit until 1981. Germany had to agree to the channelisation of the Moselle. This reduced French freight costs in the Lorraine steel industry. Germany had to agree to the teaching of French as the first foreign language in schools in the Saarland. Although no longer binding, the agreement is still in the main followed.

Development of new Communities

European Defence Community

The European Defense Community was a plan proposed in 1950 by René Pleven, the French President of the Council , in response to the American call for the rearmament of West Germany...

(EDC) was drawn up and signed on 27 May 1952. It would combine national armies and allow West Germany to rearm under the control of the new Community. However in 1954, the treaty was rejected by the French National Assembly

French National Assembly

The French National Assembly is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of France under the Fifth Republic. The upper house is the Senate ....

. The rejection also derailed further plans for a European Political Community

European Political Community

The European Political Community was proposed in 1952 as a combination of the existing European Coal and Steel Community and the proposed European Defence Community...

, being drawn up by members of the Common Assembly which would have created a federation to ensure democratic control over the future European army

Military of the European Union

The military of the European Union today comprises the several national armed forces of the Union's 27 member states, as the policy area of defence has remained primarily the domain of nation states...

. In response to the rejection of the EDC, Jean Monnet

Jean Monnet

Jean Omer Marie Gabriel Monnet was a French political economist and diplomat. He is regarded by many as a chief architect of European Unity and is regarded as one of its founding fathers...

resigned as President of the High Authority and began work on new integration efforts in the field of the economy. In 1955, the Council of Europe

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe is an international organisation promoting co-operation between all countries of Europe in the areas of legal standards, human rights, democratic development, the rule of law and cultural co-operation...

adopted an emblem for all Europe, twelve golden stars in a circle upon a blue field. It would later be adopted by the European Communities

In 1956, the Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

ian government under Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein was the second President of Egypt from 1956 until his death. A colonel in the Egyptian army, Nasser led the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 along with Muhammad Naguib, the first president, which overthrew the monarchy of Egypt and Sudan, and heralded a new period of...

nationalised the Suez canal

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal , also known by the nickname "The Highway to India", is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows water transportation between Europe and Asia without navigation...

and closing it to Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

i traffic, sparking the Suez Crisis

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also referred to as the Tripartite Aggression, Suez War was an offensive war fought by France, the United Kingdom, and Israel against Egypt beginning on 29 October 1956. Less than a day after Israel invaded Egypt, Britain and France issued a joint ultimatum to Egypt and Israel,...

. This was in response to the withdrawal of funding for the Aswan Dam

Aswan Dam

The Aswan Dam is an embankment dam situated across the Nile River in Aswan, Egypt. Since the 1950s, the name commonly refers to the High Dam, which is larger and newer than the Aswan Low Dam, which was first completed in 1902...

by the UK and United States due to Egypt's ties to the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. The canal was owned by the UK and French investors and had been a neutral zone under British control. The nationalisation and closure to Israeli traffic prompted a military response by the UK, France and Israel, a move opposed by the United States. It was a military success but a political disaster for the UK and France. The UK in particular saw it could not operate alone, instead turning to the US, and it also prompted the next British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, OM, PC was Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 January 1957 to 18 October 1963....

, to look towards joining the European Community. Equally France saw its future with the Community but opposed British entry, with then French President Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

stating he would veto

Veto

A veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

British entry out of a fear it would lead to US domination.

During the war, Israel gained the Sinai Peninsula

Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula or Sinai is a triangular peninsula in Egypt about in area. It is situated between the Mediterranean Sea to the north, and the Red Sea to the south, and is the only part of Egyptian territory located in Asia as opposed to Africa, effectively serving as a land bridge between two...

and a UN force guarded the border. However shortly after the UN force was expelled and a Six-Day War

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War , also known as the June War, 1967 Arab-Israeli War, or Third Arab-Israeli War, was fought between June 5 and 10, 1967, by Israel and the neighboring states of Egypt , Jordan, and Syria...

broke out between Israeli and its Arab neighbours. This in turn sparked the 1967 Oil Embargo

1967 Oil Embargo

The 1967 Oil Embargo began on June 6, 1967, one day after the beginning of the Six-Day War, with a joint Arab decision to deter any countries from supporting Israel militarily. Several Middle Eastern countries eventually limited their oil shipments, some embargoing only the United States and the...

which cut off or limited oils supplies to various Israel and the west. Europe was hit especially bad, due mainly to a lack of solidarity and uniformity in embargoing specific countries. As a result of the crisis, the Common Assembly proposed extending the powers of the ECSC to cover other sources of energy. However Jean Monnet desired a separate community to cover nuclear power

Nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of sustained nuclear fission to generate heat and electricity. Nuclear power plants provide about 6% of the world's energy and 13–14% of the world's electricity, with the U.S., France, and Japan together accounting for about 50% of nuclear generated electricity...

and Louis Armand

Louis Armand

For the writer and critical theorist, see Louis Armand Louis Armand was a French engineer who managed several public companies and had a significant role during World War II as an officer in the Resistance...

was put in charge of a study into the prospects of nuclear energy use in Europe. The report concluded further nuclear development was needed to fill the deficit left by the exhaustion of coal deposits and to reduce dependence on oil producers. However the Benelux states and Germany were also keen on creating a general common market

Single market

A single market is a type of trade bloc which is composed of a free trade area with common policies on product regulation, and freedom of movement of the factors of production and of enterprise and services. The goal is that the movement of capital, labour, goods, and services between the members...

, although it was opposed by France due to its protectionism

Protectionism

Protectionism is the economic policy of restraining trade between states through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, restrictive quotas, and a variety of other government regulations designed to allow "fair competition" between imports and goods and services produced domestically.This...

and Jean Monnet thought it too large and difficult a task. In the end, Monnet proposed the creating of both, as separate communities, to reconcile both groups.

As a result of the Messina Conference

Messina Conference

The Messina Conference was held from 1 to 3 June 1955 at the Italian city of Messina, Sicily. The conference of the Foreign Ministers of the six Member States of the European Coal and Steel Community would lead to the creation of the European Economic Community in 1958...

of 1955, Paul-Henri Spaak

Paul-Henri Spaak

Paul Henri Charles Spaak was a Belgian Socialist politician and statesman.-Early life:Paul-Henri Spaak was born on 25 January 1899 in Schaerbeek, Belgium, to a distinguished Belgian family. His grandfather, Paul Janson was an important member of the Liberal Party...

was appointed as chairman of a preparatory committee (Spaak Committee

Spaak Committee

The Spaak Committee was an Intergovernmental Committee set up by the Foreign Ministers of the six Member States of the European Coal and Steel Community as a result of the Messina Conference of 1955. The Spaak Committee started its work on 9 July 1955 and ended on 20 April 1956, when the Heads of...

) charged with the preparation of a report on the creation of a common European market.

The Spaak Report

Spaak Report