History of Missouri

Encyclopedia

The history of Missouri begins with France

claiming the territory and selling it to the U.S. in 1803. Statehood came following a compromise in 1820. Missouri grew rapidly until the Civil War, which saw numerous small battles and control by the Union. Its economy has become diverse and complex, and the state ranks in the middle of many economic and social indicators.

and French trader Louis Jolliet

sailed down the Mississippi River

in canoes along the area that would later become the state of Missouri

. The earliest recorded use of "Missouri" is found on a map drawn by Marquette after his 1673 journey, naming both a group of Native Americans

and a nearby river

. However, the French rarely used the word to refer to the land in the region, instead calling it part of the Illinois Country

. In 1682, after his successful journey from the Great Lakes to the mouth of the Mississippi River at the Gulf of Mexico, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

claimed the Louisiana Territory

for France. During the journey, La Salle built several trading posts in the Illinois Country in an effort to create a trading empire; however, before La Salle could fully implement his plans, he died on a second journey to the region during a mutiny in 1685.

During the late 1680s and 1690s, the French pursued colonization of central North America not only to promote trade, but also to thwart the efforts of England on the continent. In that vein, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville

established Biloxi

in 1699 and Mobile

in 1701 along the Gulf coast, while Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac

established Detroit in 1701 along the Great Lakes. From these outposts departed a variety of fur traders and Jesuit missionaries that enabled France to build strong relationships with indigenous tribes and retain control of the continental interior.

Although both Marquette and La Salle had passed Missouri on their journeys, neither had established bases of operations in what would become the state. Encouraged by the building of Mobile and Biloxi, the first to do so was Pierre Gabriel Marest, a Jesuit priest who in late 1700 established a mission on the west bank of the Mississippi at the mouth of the River Des Peres

. Marest established his mission station with a handful of French settlers and a large band of the Kaskaskia

people, who fled from the eastern Illinois Country to the station in the hope of receiving French protection from the Iroquois. Marest became involved in learning their language and constructed several cabins, a chapel, and a basic fort at the station. However, bands of Sioux

were angry at the encroachment of the Kaskaskia onto Sioux lands at Des Peres; these Sioux forced Marest to move the station south and east in 1703 to a new location in Illinois known as Kaskaskia

.

From this time up until the building of the first railways in the Mississippi Basin in the mid-19th century, the Mississippi-Missouri river system waterways were the main means of communication and transportation in the region. The earliest traffic up the Missouri likely occurred in the 1680s by unlicensed fur traders; the first known ascent occurred in 1693, and within a decade, more than a hundred traders were moving along the Mississippi and Missouri. These early traders met two tribes within what would become Missouri: the Missouri and the Osage

.

The Missouri were a semisedentary people with a major village along the Missouri River in northern Saline County, Missouri; they lived at the village primarily during the spring planting and fall harvesting seasons, while pursued game at other time. The Missouri became an ally of the French, eventually even traveling to Detroit to assist in the defense of the town against a Fox tribe attack. The Osage for their part became a more significant player in the development of Missouri history; they lived along the Osage River

in Vernon County, Missouri and near the Missouri village in Saline County. Like the Missouri, the Osage lived in semi-permanent villages, and they also both had acquired horses.

The exposure to French activities brought significant changes to the indigenous peoples of Missouri. Although interactions were generally positive between them, the introduction of diseases, alcohol, and firearms proved detrimental to traditional lifestyles and cultures. The increased dependence on European goods altered cultural patterns of craft production, and an increased emphasis on hunting due to commercialism changed Osage marriage patterns. Younger Osage hunters who had achieved wealth from trade sought to increase their power in Osage society, and they at various times challenged the established political order of tribal elders. Although both the Osage and the Missouri were exposed to European diseases such as smallpox and typhus, the Osage suffered only slightly compared to the Missouri, who were drastically reduced in population.

to create a joint stock company

to manage colonial growth. Law's Mississippi Company

(renamed the Company of the West in 1717 upon receiving its charter) was given a monopoly on all trade, ownership of all mines, and use of all military posts in Louisiana in return for a ten-year requirement to settle 6,000 white settlers and 3,000 black slaves in the territory. The Illinois Country (which included Missouri) was also to be part of the charter. Investment in the company began in earnest, and in 1719, Law merged the Company of the West with several other joint stock companies to form the Company of the Indies. Appointed as provincial governor of Louisiana by the company, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville founded the city of New Orleans in 1718, and the company appointed Pierre Dugué de Boisbriand

as commander of the Illinois Country.

After Boisbriand's arrival in the Illinois Country, he ordered the construction of Fort de Chartres

about eighteen miles north of Kaskaskia as the base of operations and headquarters for the company in the area. After the construction of Fort de Chartres, the company directed a series of prospecting expeditions to an area 30 miles west of the Mississippi River in present-day Madison

, St. Francois, and Washington

counties. These mining operations generally focused on discovering either lead or silver ore; the company appointed Philip Francois Renault

as commander of the mines, and in 1723 Boisbriand ceded land to Renault in Washington County (in an area now known as the Old Mines) and in the Mine La Motte

area. Because of the unappealing nature of mine work, white laborers demanded high wages; in response, Renault brought five black slaves to work in the mines, the first black slaves in Missouri. Despite these efforts, weather and hostility among indigenous tribes slowed production, and Renault sold his lands in 1742 having made little profit.

Despite severe financial losses in late 1720, in January 1722 the company's directors sent Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont

to Missouri to protect the company's trade networks on the Missouri River from Spanish influence. Bourgmont arrived in New Orleans in September 1722, and he departed from the city for Missouri in February 1723 with a poorly equipped force. In November 1723, Bourgmont and the party arrived in present-day Carroll County in northern Missouri, where they constructed Fort Orleans

. Within a year, Bourgmont negotiated alliances with indigenous tribes along the Missouri River, and in 1725, he brought a party of them to Paris

to visit the French royal court. Bourgmont remained in France when the party returned to North America, and Fort Orleans was abandoned by the company in 1728. The quick abandonment of the fort after its construction was necessitated by the general retreat on the part of the company after the financial losses of 1720, and in 1731, the company returned its charter and control of Louisiana to royal authority.

During the 1730s and 1740s, French control over Missouri remained weak, and no permanent settlements existed on the western bank of the Mississippi River. Despite this lack of permanence, French fur traders continued to ascend the Missouri River and interact with indigenous peoples; one such duo, Paul and Pierre Mallet, journeyed from Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico

in 1739, although future expeditions to New Spain were stopped by Spanish officials. In 1744, the French commander of Fort de Chartres gave five years of fur trading rights along the Missouri River to Joseph Deruisseau, who built a small fort (Fort de Cavagnal

) on the Missouri River near present-day Kansas City, Missouri

. However, the trading post never grew into a full-fledged settlement, and it disappeared by 1764.

French settlers remained on the east bank of the Mississippi at Kaskaskia and Fort de Chartres until 1750, when the new settlement of Ste. Genevieve, Missouri

was constructed. During its early years, Ste. Genevieve grew slowly due to its location on a muddy, flat, floodplain, and in 1752, the town had only 23 full-time residents. Despite its proximity to lead mines and salt springs, the majority of its population came as farmers during the 1750s and 1760s, and they primarily grew wheat, corn and tobacco.

in 1754 (known as the Seven Years' War

in Europe).Foley (1989), 25. The successful English attack on Quebec in 1759

and on Montreal in 1760

virtually guaranteed the loss of French Canada, although France remained in control of Missouri and the rest of the Illinois Country. In January 1762, Spain joined with France against England, but the war quickly turned against them for England. To persuade Spain to sign a peace settlement with England and to compensate for Spanish losses in the war, France secretly offered Spain control of Louisiana in November 1762 in the Treaty of Fontainebleau

. In addition to the loss of Louisiana in the Treaty of Fontainebleau, the final settlement with England, known as the Treaty of Paris

, transferred Canada from French to English control.

However, due to slow transit times, word of the Treaty of Fontainebleau did not arrive in Louisiana until 1765; in that period, the French governor of Louisiana granted a trade monopoly over Missouri to New Orleans merchant Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent

and his partner, Pierre Laclède

. In August 1763, Laclede and his stepson Auguste Chouteau departed New Orleans for Missouri, where in February 1764 they established St. Louis

on high bluffs overlooking the Mississippi.

Although Laclede had brought the news in December 1763 of the transfer of the eastern Illinois Country to the United Kingdom, the French commander Pierre Joseph Neyon de Villiers only received his orders to begin evacuations in April 1764. Villiers departed for New Orleans in June 1764 with 80 families, and he transferred temporary control to his subordinate, Louis St. Ange de Bellerive, who was given responsibility to monitor the remaining settlers in Illinois. Concern about living under British rule led many French settlers to decamp for Missouri, especially with encouragement from Laclede; upon the arrival of the British at Fort de Chartres in October 1765, St. Ange himself departed for St. Louis, where he took temporary command until Spanish representatives could take official control. From that point through the arrival of the Spanish in St. Louis in September 1767, St. Ange was the interim commander of the entire upper Louisiana region.

The first Spanish governor of Louisiana, Antonio de Ulloa

, arrived in New Orleans in March 1766, and in early 1767 he dispatched his subordinate, Francisco Riu, to replace St. Ange as commander of a soon-to-be-built fort at the mouth of the Missouri River. St. Ange, however, remained the administrative authority in the town and south of the Missouri River. The fort that Ulloa had ordered built, known as Fort Don Carlos, ultimately was constructed on the southern bank of the Missouri; however, disputes during the construction led to the dismissal of Riu and his replacement by Pedro Piernas in August 1768.

Weather and ice delayed Piernas's ascent to Fort Don Carlos through April 1769; between his arrival and his departure, the Louisiana Rebellion of 1768 broke out in New Orleans against Spanish rule, and Ulloa was forced to flee. Only 13 days after his arrival to Fort Don Carlos, Piernas received orders to evacuate the fort and return control to St. Ange. When Piernas and his garrison left Louisiana in July 1769, they were the last Spanish forces to leave the territory. Spanish officials acted quickly to crush the rebellion, however, and in August 1769, resistance collapsed. Although the rebellion led to the execution of five rebel leaders in New Orleans, no reprisals were necessary or occurred in Missouri.

Upon the reestablishment of Spanish control of Louisiana, both of Missouri's permanent settlements, Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis, were growing as a result of French immigration from British-held Illinois. Ste. Genevieve continued to suffer from periodic flooding, although during the 1770s its population of 600 made it slightly larger than St. Louis. While the residents of Ste. Genevieve took a balanced approach between fur trading and farming, St. Louisans had a particular focus on fur trading, which led to periodic food shortages and the city's nickname of 'Paincourt', meaning short of bread. South of St. Louis a satellite city known as Carondelet was established in 1767, although it never thrived. A third major settlement was established in 1769, when Louis Blanchette

, a Canadian trader, set up a trading post on the northwest bank of the Missouri River, which eventually grew into the town of St. Charles.

In 1770, Piernas fully replaced St. Ange as administrator of the colony, although he retained the veteran Frenchman as an adviser. Local administrators of Ste. Genevieve also were Spanish-appointed, but frequently were forced to acquiesce to local customs. Throughout the 1770s, Spanish officials were forced to contend not only with the wishes of their predominantly French populations, but also with repeated incursions from British traders and hostile indigenous tribes.

To reduce the influence of British traders, Spain renewed efforts to encourage French settlers to decamp from Illinois to Missouri, and in 1778, the Spanish granted land and basic supplies to Catholic immigrants to Missouri; however, few settlers actually took up the offers to move to the region. A second effort by the Spanish against the British found greater success: starting in the late 1770s, the Spanish officials began openly supporting American rebels fighting against British rule in the American War of Independence. Spanish officials in both St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve were instrumental in supplying George Rogers Clark

during his Illinois campaign of 1779.

However, Spanish aid to the rebels came at a price: in June 1779, Spain declared war on England, and word reached Missouri of the war in February 1780. By March 1780, St. Louis was warned of an impending British attack, and the Spanish government began preparations for a fort at the town, known as Fort San Carlos. In late May, a British war party attacked the town of St. Louis; although the town was saved, 21 were killed, 7 were wounded, and 25 were taken prisoner.

After the American victory in its war of independence, the European countries involved negotiated a set of treaties known as the Peace of Paris

. The Spanish, who retained Louisiana, were forced to contend with large numbers of American immigrants crossing into Missouri from the east. Rather than attempt to stifle the immigration of American Protestants, however, Spanish diplomats began encouraging it in an effort to create an economically successful province.

As part of this effort, in 1789 Spanish diplomats in Philadelphia encouraged George Morgan

, an American military officer, to set up a semi-autonomous colony in southern Missouri across from the mouth of the Ohio River

. Named New Madrid

, the colony began auspiciously but was discouraged by Louisiana's governor, Esteban Rodríguez Miró

, who considered Morgan's infant colony as flawed due to its lack of provisos for ensuring the settlement's loyalty to Spain. New Madrid's early American settlers departed, as did Morgan, and New Madrid became primarily a hunting and trading outpost rather than a full-fledged agricultural city.

Despite Spanish diplomats' efforts, during the early 1790s both Governor Miró and his successor, Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet

, were cool toward the idea of American immigration to Missouri. However, with the onset of the Anglo-Spanish War in 1796, Spain again needed an influx of settlement to defend the region. To that end, Spain began advertising free land and no taxes in Spanish territory throughout American cities, and Americans responded in a wave of immigration. Among these American pioneer

s was Daniel Boone

, who settled with his family after encouragement from the territorial governor.

To better govern the region of Missouri, the Spanish split the province into five administrative districts in the mid-1790s: St. Louis, St. Charles, Ste. Genevieve, Cape Girardeau

and New Madrid.Foley (1989), 84. Of the five administrative districts, the newest was Cape Girardeau, founded in 1792 by trader Louis Lorimier as a trading post and settlement for newly arriving Americans. The largest district, St. Louis, was the provincial capital and center of trade; by 1800, its district population stood at nearly 2,500. Aside from Carondelet, other settlements in the St. Louis district included Florissant

, located 15 miles northwest of St. Louis and settled in 1785, and Bridgeton

, located 5 miles southwest of Florissant and settled in 1794. All three settlements were popular with immigrants from the United States.

However, these American settlers fundamentally changed the makeup of Missouri; by the mid-1790s, Spanish officials realized the American Protestant immigrants were not interested in converting to Catholicism or in serious loyalty to Spain. Despite a brief attempt to restrict immigration to Catholics only, the heavy immigration from the United States changed the lifestyle and even the primary language of Missouri

; by 1804, more than three-fifths of the population were American. With little return on their investment of time and money in the colony, the Spanish negotiated the return of Louisiana, including Missouri, to France in 1800, which was codified in the Treaty of Ildefonso

.

.png) At the time of the transfer to France in 1800, the population of Upper Louisiana was primarily concentrated in the settlements along the Mississippi in present-day Missouri. A dirt roadway linked the towns of Ste. Genevieve and New Madrid, but a trail between St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve was mostly unused due to rough terrain. Most residents traveled between towns on riverboats, primarily canoes, pirogues, and bateaux (later replaced by keelboats). Subsistence agriculture was the primary economic activity, although most farmers also raised livestock. Fur trading, lead mining, and salt making were also significant economic activities for residents during the 1790s.

At the time of the transfer to France in 1800, the population of Upper Louisiana was primarily concentrated in the settlements along the Mississippi in present-day Missouri. A dirt roadway linked the towns of Ste. Genevieve and New Madrid, but a trail between St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve was mostly unused due to rough terrain. Most residents traveled between towns on riverboats, primarily canoes, pirogues, and bateaux (later replaced by keelboats). Subsistence agriculture was the primary economic activity, although most farmers also raised livestock. Fur trading, lead mining, and salt making were also significant economic activities for residents during the 1790s.

Religion in colonial Missouri was a strong element of cultural life, and the Catholic Church had been a significant part of life among the colonists since the earliest settlements.Foley (1989), 102. Although the Jesuits were the primary religious authority in the region, the French expelled the order in 1763 due to its growing wealth and power. Combined with the expulsion of the Jesuits, the transfer of the colony to Spain also caused a shortage of priests, as French priests under Canadian jurisdiction were prohibited from conducting services. Through 1773, Missouri parishes lacked resident priests, and residents were served by traveling priests from the east side of the Mississippi. During the 1770s and 1780s, both Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis gained resident priests, although not without difficulty; during the 1790s, St. Charles and Florissant were forced to share a resident priest, despite both having built parish churches. Throughout the period, both the French and the Spanish provided monetarily for the sustenance of the church; as part of their support, both governments forbade Protestant services in the colony.Foley (1989), 104. However, itinerant Protestant ministers frequently visited the settlements in private, and restrictions on Protestant residency were rarely enforced. According to Missouri historian William E. Foley, colonial Missouri lived under a "de facto form of religious toleration

," with few residents demanding rigid orthodoxy.

Social class was particularly fluid during the colonial period, although there were some distinctions.Foley (1989), 105. The highest class was based upon wealth and constituted of a mixed group of colonial-born merchants linked by familial ties. Below this class were the artisans and craftsmen of the society, followed by laborers of all types, including boatmen, hunters, and soldiers. Near the bottom of the social system were free blacks, servants, and coureur des bois

, with black and Indian slaves forming the bottom class.

Crime and social indiscretions also were a part of life in colonial Missouri; however, government officials quickly dealt with those who broke social norms. In 1770, when a trader mocked Spanish regulations outside the church in St. Louis, he was banished from the colony for ten years; the same year, a laborer was banished for stealing and illicit relations with slave women. During the late 1770s, a series of robberies was ended by the institution of nightly patrols in St. Louis. Spanish soldiers often were responsible for the major crimes; in 1775, a soldier killed a Ste. Genevieve resident in a drunken knife fight, while soldiers in St. Louis frequently were accused of fighting, drunkenness, and stealing.

Women in the region were responsible for a variety of domestic tasks, including food preparation and clothing making. French colonial women were well-known for their cooking, which incorporated both French staples such as soups and fricasses and African and Creole foods such as gumbo. The colonists also ate local meats, including squirrel, rabbits, and bear, although they preferred beef, pork and fowl. Most foods were local, although sugar and liquor were imported until the late colonial period.

Women also were responsible for child-rearing and basic schooling, and for nursing the sick. Diseases such as malaria

, whooping cough, and scarlet fever

were frequent maladies throughout the period, with malaria particularly affecting low-lying settlements such as Ste. Genevieve. Smallpox

only affected the settlements late in the 1700s. Schools were private and classes were tutor-based; small schools operated intermittently during the 1780s and 1790s in both St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve, and a private English-language school opened in New Madrid during the late 1790s. The wealthiest families sometimes sent children to other regions to obtain education: François Vallé

of Ste. Genevieve sent his son to New York City in 1796, while Auguste Chouteau sent his eldest son to Canada in 1802.

The black population of Missouri and the region was not insignificant. In 1772, nearly 38 percent of residents were of African descent, and although suffering a decline, in 1800 it remained nearly 20 percent of the total. The first blacks in Missouri were the handful of slaves of Philippe Renault, but they were followed by groups imported by Spain to work in agriculture. These slaves made significant contributions to regional development through their labor in mines, fields, and in transportation. Both the French and the Spanish used black codes to regulate the use of enslaved Africans in the territory. It had certain protections for what was considered an economic investment, such as prohibitions on imprisonment, mutilation, and death. The Spanish regime continued most of the Code Noir in 1769, but also permitted enslaved blacks to own property, appear as parties to lawsuits, work on their own account, and purchase their freedom.

ended the French expedition. In October 1802, these officials suspended foreign trade at the port of New Orleans, which led the United States to negotiate with France to purchase New Orleans in March 1803. However, the French defeat in Haiti and the desire for money to fight Britain led Napoleon to sell all of Louisiana, including Missouri, to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase

.

Official news of the transfer had reached the region in August 1803 in a letter from the governor of the Indiana Territory

, William Henry Harrison

. Although the transfer of all of Louisiana was formalized in a ceremony in New Orleans in December 1803, a separate ceremony took place in St. Louis in March 1804 to commemorate the transfer of Upper Louisiana.

Even before the purchase President Thomas Jefferson

was planning to explore the region; he sent the Lewis and Clark Expedition

and the Pike expedition

to map the region. In 1805 Congress organized the Louisiana Territory

was with the government seat in St. Louis. The U.S. Army soon built trading and military forts to establish control over the territory, Fort Bellefontaine

was made an Army post near St. Louis in 1804, and Fort Osage

was built along the Missouri River in 1808.

The Mississippi-Ohio river systems were navigated by steamboat

starting in 1811 with the New Orleans steamboat travelling from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

, to New Orleans

. On December 16, 1811, the New Madrid earthquakes smashed the lightly populated region.

became a state in 1812, the remaining Louisiana Territory was renamed the Missouri Territory

. That year, the first general assembly of the Missouri Territory was created, with the five original counties being Cape Girardeau, New Madrid, Saint Charles, Saint Louis, and Ste. Genevieve.

Southerners poured into Missouri Territory during 1804-21. The rapid population growth was facilitated by treaties that extinguished Indian land titles, with settlers attracted by the abundance of high quality inexpensive land, and the easy access provided by the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. By 1810 European Americans dominated the population, demographically, and financially. They overwhelmed the small French-speaking element and sent Native Americans to lands further west. Land in the public domain was quickly surveyed and sold to yeoman farmers

, whose hard work was rapidly rewarded. Ranchers raised cattle; the Missouri woodland had ample grass for natural grazing. European Americans in early Missouri laid the groundwork for the new state, and their stamp remains strong in the landscape into the 21st century.

Missouri was at the western frontier during the War of 1812

, and the main regional headquarters of the U.S. Army was based at Fort Bellefontaine

near St. Louis. Other forts included Fort Cap au Gris

; Fort Osage

was abandoned at the start of the war. Several skirmishes were fought in Missouri, including the Battle of the Sink Hole

, one of the last battles of the war, on May 24, 1815.

In 1817, the first steamboat reached Saint Louis. That year, the commerce from New Orleans to the Falls of the Ohio

at Louisville

was carried in barges and keel-boats having a capacity of 60 to 80 tons each, with 3 to 4 months required to make a single trip. In 1820 steamboats were making the same trip in 15 to 20 days, by 1838 in 6 days or less. By 1834 there were 230 steamboats, having an aggregate tonnage of 39,000 tons, engaged in trade on the Mississippi. Large numbers of flat boats, especially from the Ohio and its tributaries, continued to carry produce

downstream. In 1842 Ohio completed an extensive canal system that connected the Mississippi with the Great Lakes

. These were in turn connected in 1825 by the Erie Canal with the Hudson River

and the Port of New York on the Atlantic Ocean. There was expansive growth of resource commodity, and agricultural products trade throughout the rivers and Great Lakes network.

In 1818, Saint Louis University

was founded, a Catholic Jesuit Seminary that was the first college west of the Mississippi River. It expanded its programs to include secular instruction.

cleared the way for Missouri's entry to the union as a slave state, along with Maine

, a free state, to preserve the balance. Additionally, the Missouri Compromise stated that the remaining portion of the Louisiana Territory above the 36°30′ line was to be free from slavery. This same year, the first Missouri constitution was adopted. The following year, 1821, Missouri was admitted as the 24th state, with the state capital temporarily located in Saint Charles until a permanent capital could be built. Missouri was the first state entirely west of the Mississippi River

to be admitted to the Union. The state capital moved to Jefferson City in 1826.

and Tennessee

moved into the bottomland of "Little Dixie

" region in the central part of the state. They bought up large tracts of fertile land, and brought in slaves to do the work of growing hemp (for rope making) and tobacco, traditional crops of the Upper South. Slaves were expensive, with the average price of $700 in 1860, the equivalent of three or four years' pay for a free worker. In most of the state, slavery was unprofitable, and in 7/8 of the counties, farmers had no slaves.

In 1824, the Missouri State Supreme Court

ruled that free blacks could not be re-enslaved, a principle known as "once free, always free." In 1846, the Dred Scott v. Sandford

case began. Dred and Harriet Scott

, who were slaves, sued for freedom in state courts. This was on the premise that they had previously lived in a free state. This case continued until 1857, culminating in a landmark United States Supreme Court decision rejecting Scott's arguments and sustaining slavery. In 1860, 3600 free blacks lived in Missouri.

The proportion of slaves in the state population peaked at 18 percent in 1830; by 1860 the proportion was 9.8 percent in 1860, following heavy Irish and German immigration from the 1840s, as well as continued migration from the eastern United States. In St. Louis, nine percent of the 14,000 residents in 1840 were slaves, and only one percent of the 57,000 residents in 1860, Although few Missouri families owned slaves, many whites of southern origin thought that slavery was basically a good idea, and that freeing the slaves would be a calamity for the white population. The state officially abolished slavery in January 1865 when the governor signed the Ordinance of Emancipation

.

in the Kansas City West Bottoms

. Land in what is now northwest Missouri was deeded to the Iowa (tribe) and the combined Sac (tribe)

and Fox (tribe). Following encroachments on the land by white settlers—most notably Joseph Robidoux

-- William Clark persuaded the tribes to agree give up their land in exchange for $7,500 in the 1836 Platte Purchase

. The land was ratified by Congress in 1837. The purchase received widespread support from Southern Congressmen since it would mean adding territory to the only slave state north of Missouri's southern border. An area only somewhat smaller than the combined area of Rhode Island

and Delaware

was added to Missouri. It consisted of the Andrew

, Atchison

, Buchanan

, Holt

, Nodaway

and Platte

counties.

After the California Gold Rush

began in 1848, Saint Louis, Independence

, Westport

and especially Saint Joseph

became departure points for those joining wagon trains to the West. They bought supplies and outfits in these cities to make the six-month overland trek to California, earning Missouri the nickname "Gateway to the West". This is memorialized by the Gateway Arch in St. Louis.

In 1848, Kansas City

was incorporated on the banks of the Missouri River. In 1860, the Pony Express

began its short-lived run carrying mail from Saint Joseph to Sacramento, California

.

. They introduced the upper South agricultural-economic pattern, with its mix of hog and corn production practiced by small-scale farmers and cattle and tobacco production practiced by large-scale farmers. Families typically moved to the region not as solitary units but as elements of large kin-based networks that maintained geographic integrity by purchasing clustered tracts of land.

Missouri was nationally famous for the quality and quantity of its mules. The state produced a superior breed from Mexican and Eastern stock. Some were used on the western trails, and a larger number were used on southern plantations. The industry provided a full-time livelihood for a few traders, feeders and breeders, but it supplemented the income for a far larger number of farmers. Horses, which are larger and more expensive to maintain, but which can do more work, remained the favorite animal on Missouri farms.

that western Missouri, specifically the area around Independence

, and other areas of western Missouri, were to become Zion

and a place of gathering. By the early 1830s, Mormons came into the area, at first to Independence and its nearby environs. The neighbors refused to tolerate the newcomers because the Mormons would vote in blocks and congregate in concentrated areas, and would typically trade only amongst themselves, and they would not hold slaves. Open claims by the Mormons that the area was given to them by God only worsened the situation. By the mid 1830s, Mormons had effectively been driven from the Independence area, but they relocated to counties north and a little east. By 1838, open hostility was peaking again. Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs

issued Missouri Executive Order 44, which encouraged Missourians to expel Mormons by all means possible or exterminate them if they would not leave. Skirmishes and small battles occurred and a number of people were killed, mostly Mormons. Joseph Smith, Jr., was jailed, along with other LDS leaders and held in several jails for more than five months, with no hope of a trial or court hearing. Smith was allowed to escape and he and his church moved to Illinois to form the city of Nauvoo

in 1839. Missouri still holds many important sites still considered significant by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Community of Christ

. In 1976 Missouri officially revoked the extermination order.

. When war broke out in April 1861 sympathies ran for both sides, the Confederacy

and the Union, and it was in Saint Louis where the first blood was spilled in the "Camp Jackson Affair". Union military forces quickly seized control of all strategic points and drove the Confederate government into exile.

The majority of St. Louis business leaders supported the Union and rejected efforts by Confederate sympathizers to take control of the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce in January 1862. Federal authorities intervened in this struggle but the conflict splintered the Chamber of Commerce into two organizations. The pro-Unionists finally gained the ascendancy and St. Louis became a major supply base for the Union forces in the entire Mississippi Valley.

In 1861, Union General John C. Fremont

issued a proclamation that freed slaves who had been owned by those that had taken up arms against the Union. Lincoln immediately reversed this unauthorized action. Secessionists tried to form their own state government, joining the Confederacy and establishing a Confederate government in exile

first in Neosho

, Missouri and later in Texas (at Marshall, Texas

). By the end of the war, Missouri had supplied 110,000 troops for the Union Army

and 40,000 troops for the Confederate Army.

commanded by Sterling Price

initiated a long retreat from Boonville

to the Southwestern portion of the state in 1861. In Carthage

, the Guard defeated a heavy detachment of Federal regulars commanded by Col. Franz Sigel

. Shortly afterward, the 12,000-man force of the combined elements of the Missouri State Guard, Arkansas State Guard, and Confederate regulars soundly defeated the Federal army of Nathaniel Lyon

at Wilson's Creek

or "Oak Hills".

Following the success at Wilson's Creek, southern forces pushed northward and captured the 3500-strong garrison at the first Battle of Lexington

. Federal forces contrived to campaign to retake Missouri, causing the Southern forces to retreat from the state and head for Arkansas and later Mississippi.

In Arkansas, the Missourians fought at the battle of Pea Ridge, meeting defeat. In Mississippi, elements of the Missouri State Guard participated in the struggles at Corinth

and Iuka

, where they suffered heavy losses.

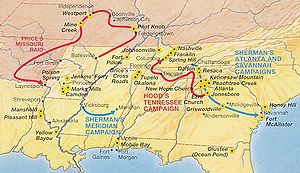

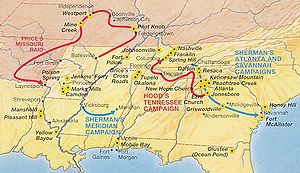

In 1864, Sterling Price plotted to liberate Missouri, launching his 1864 raid on the state

In 1864, Sterling Price plotted to liberate Missouri, launching his 1864 raid on the state

. Striking in the southeastern portion of the state, Price moved north, and attempted to capture Fort Davidson

but failed. Next, Price sought to attack St. Louis but found it too heavily fortified. He then broke west in a parallel course with the Missouri River. The Federals attempted to retard Price's advance through both minor and substantial skirmishing such as at Glasgow

and Lexington

. Price made his way to the extreme western portion of the state, taking part in a series of bitter battles at the Little Blue

, Independence, and Byram's Ford. His Missouri campaign culminated in the battle of Westport

in which over 30,000 troops fought, leading to the defeat of the Southern army. The Missourians retreated through Kansas

and Oklahoma

into Arkansas, where they stayed for the remainder of the war.

In 1865, Missouri abolished slavery, doing so before the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

, by an ordinance of immediate emancipation. Missouri adopted a new constitution, one that denied voting rights and had prohibitions against certain occupations for former Confederacy supporters.

. In such a bitterly divided state, neighbors frequently used the excuse of war to settle personal grudges and took up arms against neighbors. Roving insurgent

bands such as Quantrill's Raiders

and the men of Bloody Bill Anderson terrorized the countryside, striking both military installations and civilian settlements. Because of the widespread guerrilla conflict, and support by citizens in border counties, Federal leaders issued General Order No. 11 in 1863, and evacuated areas of Jackson, Cass, and Bates counties. They forced the residents out to reduce support for the guerrillas. Union cavalry could sweep through and track down Confederate guerrillas, who no longer had places to hide and people and infrastructure to support them. On short notice, the army forced almost 20,000 people, mostly women, children, and the elderly, to leave their homes. Many never returned, and the affected counties were economically devastated for years after the end of the war. Families passed stories of their bitter experiences down through several generations.

Western Missouri was the scene of brutal guerrilla warfare during the Civil War, and some marauding units became organized criminal gangs after the war. In 1882, the bank robber and ex-Confederate guerrilla Jesse James

was killed in Saint Joseph

. Vigilante groups appeared in remote areas where law enforcement was weak, to deal with the lawlessness left over from the guerrilla warfare phase. For example, the Bald Knobbers

were the term for several law-and-order vigilante groups in the Ozarks. In some cases, they too turned to illegal gang activity.

was a private agency based in St. Louis that was a rival of the larger U.S. Sanitary Commission. It operated during the war to help the U.S. Army deal with sick and wounded soldiers. It was led by abolitionists and especially after the war focused more on the needs of Freedmen. It was founded in August 1861, under the leadership of Reverend William Greenleaf Eliot

(1811-87), a Yankee, to care for the wounded soldiers after the opening battles. It was supported by private fundraising in the city of St. Louis, as well as from donors in California and New England. Parrish explains it selected nurses, provided hospital supplies, set up several hospitals, and outfitted several hospital ships. It also provided clothing and places to stay for freedmen and refugees, and set up schools for black children. It continued to finance various philanthropic projects until 1886.

The state convention began deliberating on January 7, 1865 in the Mercantile Exchange Library Building in St. Louis; the group was, like the General Assembly, dominated by relatively young Radical Republicans. Among the first measures taken by the convention was the passage of an emancipation

ordinance on January 11 that took effect immediately. With the passage of the ordinance, spontaneous celebrations broke out in major cities, and Governor Thomas Clement Fletcher

issued an official proclamation in honor of the event. St. Louis held an official celebration on January 14, which included a reading of the proclamation, interracial social events, and a fireworks display.

as a compromise candidate for governor of Missouri. During the Civil War, Hardin had supported the Union cause, and from the 1850s to the early 1870s, he had served three terms in the Missouri House and two terms in the Missouri Senate. The Democrats nominated agriculturalist Norman Jay Colman

as candidate for lieutenant governor, who drew support from rural areas due to his endorsement of Free Silver

and his desire to repeal the National Bank Act. With Colman's popularity, Hardin was elected in November 1874 with support from 81 of 114 Missouri counties.

In May 1875, delegates from Missouri met in Jefferson City to consider a new state constitution to replace the state's Reconstruction era constitution. The majority of the delegates were conservative, well-educated, and generally had ties to the American South. 35 of the 68 delegates either served with the Confederacy or were allied to its cause; the presiding officer, Waldo P. Johnson

, had been expelled from the U.S. Senate in 1862 after he joined the Confederacy. The document produced by the convention was a reaction to the radicalism of the 1860s and 1870s, and it encouraged local control and a reduction in the powers of the state. The document removed the ability of the state to suspend the writ of habeas corpus

, increased the standards required to prove the crime of treason, limited the ability of the state and local governments to tax, and reduced the restrictions on churches being able to own property. It also required a two-third vote by citizens to authorize the issuance of bonds, and it restricted the ability of state legislators to craft legislation that would benefit their localities. The proposal was submitted for popular vote on August 2, 1875, and the constitution passed overwhelmingly.

to commerce. When the war was over, the prosperity of the South was temporarily ruined. Hundreds of steamboats had been destroyed, and levees had been damaged by warfare and flooding. Much of the commerce of the West had been turned from New Orleans, via the Mississippi, to the Atlantic seaboard

, via the Great Lakes

and by the rapidly multiplying new lines of railways connecting through Chicago. Some revival of commerce on the Mississippi took place following the war, but this was checked by a sandbar at the mouth of the Southwest Pass in its delta on the Gulf of Mexico. Ead's jetties created a new shipping passage at the mouth of the South Pass in 1879, but the facilities for the transfer of freight in New Orleans were far inferior to those employed by the railways, and the steamboat companies did not prosper.

Up to the 1880s, the six southeastern counties of Missouri's Bootheel

, swampy and subject to flooding, remained heavily forested, underdeveloped, and underpopulated. Beginning in the 1880s, railroads opened up the Bootheel to logging. In 1905, the Little River Drainage District constructed an elaborate system of ditches, canals, and levees to drain swampland. As a result, population more than tripled from 1880 to 1930, and cotton cultivation flourished. By 1920 it was the chief crop, attracting newcomers to the farms from Arkansas and Tennessee.

The Hall brothers, Joyce, Rollie, and William, emerged from poverty in Nebraska in the 1900s by opening a bookstore. When the European craze for sending postcards reached America, the brothers quickly began merchandizing them and became the postcard jobber for the Great Plains. As business boomed they relocated to Kansas City in 1910 and eventually founded the Hallmark Cards

gift card company, which soon came to dominate a national market. Allen Percival "Percy" Green operated the A. P. Green Company in Mexico, Missouri. Green bought a struggling brickworks in 1910 and found a national market by transforming it into a leading manufacturer of "fire bricks," bricks designed to withstand high temperatures for use in steel plants and lining the boilers of ships. In 1913, in the town of Clinton, Royal Booth, then a high school junior, began a business breeding purebred chickens. After serving in the Army in World War I, Booth returned to his booming enterprise. The growth of his Booth Farms and Hatchery had encouraged other area entrepreneurs to enter the poultry breeding business. Booth rebuilt his operation after a 1924 fire, and concentrated on breeding hens that laid eggs all year long. By 1930, Clinton's hatcheries had an annual capacity of over three million eggs, making Clinton the "Baby Chick Capital of the World" and benefiting thousands of farmers throughout the region; however, the industry declined and the hatchery closed in 1967.

The large German American

population, most immigrants and their descendants from the 1840s, specialized in brewing beer, and established numerous beer gardens in St. Louis and other cities. Eberhard Anheuser

created the E. Anheuser & Company Bavarian Brewery in St. Louis, in 1860 and in 1869 made a full partner of Adolphus Busch, who later utilized pasteurization and refrigeration to keep beer fresh, and marketed Anheuser-Busch

products nationally. Busch introduced Budweiser to America, eventually making it the world's most popular brand through extensive advertising, including television commercials. The Busch family maintained control until it sold out to European interests in 2008 for $52 billion.

Edward Leavy, head of Pierce Petroleum company, identified the potential of the Ozark region as a tourist attraction in the 1920s. Pierce Petroleum opened roadside taverns and expanded to include gas stations, hotels, restaurants, and a variety of services for automobile travelers. The Great Depression

forced Pierce Petroleum to sell out to Sinclair Consolidated Oil Corporation, but by then many other entrepreneurs saw the opportunity for tours expansion in the Ozarks.

Only dairy farming survived the pressure of livestock production. By the 1970s, however, agriculture in the Ozarks had come full circle. Many modern farmers survived only by becoming part-time farmers. Much of the population commutes to paid employment for most of their income, in much the same way as the pioneers had been forced to diversify their efforts.

women was to be good, diligent, submissive, and silent housewives. The historical records show more variety, with many being cantankerous, complaining, and unwilling to subordinate themselves. Some were dirty and lazy, and completely unlike the hausfrau stereotype. These nonconformists exerted a greater influence on the community scene than they could by strict conformity to generally accepted behavior.

Throughout the century, most rural families lived traditional lifestyles, based on male dominance. Efforts to modernize rural life, and upgrade the status of women, were reflected in numerous movements, including women's church activities, temperance reform, and the campaign for woman suffrage. Reformers sought to modernize the rural home by transforming its women from producers to consumers. The Missouri Women Farmers' Club (MWFC) and its management was especially active.

The great majority of women were full-time homemakers, whose labor created materials and clothing, food, agriculture and basics of life for their families. After the Civil War some women became wage earners in industrializing cities. It was common for widows to operate boardinghouses or small shops; younger women worked in tobacco, shoe, and clothing factories. Some women helped their husbands publish local newspapers, which flourished in every county seat and small city. In 1876, women began to attend the Missouri Press Association's meetings; by 1896 the women formed their own press association, and at the end of the century, women were editing or publishing 25 newspapers in Missouri. They were especially active in developing features to entertain their women readers, and to help women with their housework and child-rearing.

In highly traditional, remote parts of the Ozark Mountains, there was little demand for modern medicine. Childbirth, aches, pains and broken bones were handled by local practitioners of folk medicine, most of whom were women. Their herbs, salves and other remedies often healed sick people, but their methods relied especially on recognizing and ministering to their patients' psychological, spiritual, and physical needs.

Before the war, the police and municipal judges used their powers to regulate rather than eliminate the sex trades. In antebellum

St. Louis, prostitutes working in orderly, discreet brothels were seldom arrested or harassed - unless they were unusually boisterous, engaged in sexual activities outside of their established district, or violated other rules of appropriate conduct. In 1861, St. Louis passed a vagrancy ordinance, criminalizing any woman who walked on the streets after sunset. In 1871, the city passed a law forbidding women from working in bars and saloons, even if the women were owners. These laws were meant to keep prostitution at a minimum but adversely affected women who were legitimately employed.

Middle-class women demanded entry into higher education, and the state colleges reluctantly admitted them. Culver-Stockton College opened in the 1850s as a coeducational school, the first west of the Mississippi. Women were first admitted to the normal school of Missouri State University at Columbia in 1868, but they had second-class status. They were shunted into a few narrow academic programs, restricted in their use of the library, separated from the men, and forced to wear uniforms. They were not allowed to live on campus. President Samuel Spahr Laws was the most restrictive administrator, enforcing numerous rules and the wearing of drab uniforms. Still, the number of women students at the school grew despite the difficulties. When the Missouri School of Mines and Metallurgy opened at Rolla in 1871, its first class had 21 male and six female students. Well into the 20th century, the women who attended the school were given an arts and music program that was little better than a high school education.

Josephine Silone Yates (1859–1912) was as African-American activist who devoted her career to combating discrimination and uplifting her race. She taught at the Lincoln Institute in Jefferson City, and served as the first president of the Women's League of Kansas City; she was later president of the National Association of Colored Women

. Yates tried to prepare women for roles as wage earners in Northern cities. She also encouraged black ownership of land for those who remained in the South. Since whites judged blacks by the behavior of the lower class, she argued that advancement of the race ultimately depended on working-class adherence to a strict moral code.

reform movement which involved prominent educators and social workers and a coalition of citizens' groups. The first commission began in 1915 to develop proposals to protect children from harsh working conditions and deal with delinquency, neglect, and child welfare welfare. Its proposals were rejected by the conservative legislature. Appointed in 1917, the second commission revised the earlier proposals and actively engaged in an educational promotional campaign, gaining the support of various organizations such as the Women's Christian Temperance Union, The Red Cross, women's clubs, suffrage groups, and others. The Missouri Children's Code was finally passed in 1919.

In 1919, Missouri became the 11th state to ratify the 19th amendment

, which granted women the right to vote.

During the Progressive Era

in the early twentieth century, there were three competing visions of appropriate control and use of water resources of the Missouri River; they were expressed by three organizations: the Kansas City Commercial Club (KCCC), the Missouri River Sanitary Conference (MRSC), and the Missouri Valley Public Health Association (MVPHA). The KCCC's vision of commercial development envisioned the "Economic River." MRSC's vision of a shared water supply requiring protection through community cooperation emphasized the "Healthy River." MVPHA's vision of commercial development coupled with individual efforts to prevent pollution was a compromise blending of the first two. The "Economic River" represents the Progressive approach focused on professional elites and federal solutions, whereas the "Healthy River" represents the approach focused on community leadership and solutions, as well as an early example of holistic, locally oriented conservation.

Sarvis (2000, 2002) traces the controversy over the creation of the Ozark National Scenic Riverways

(ONSR) in southeastern Missouri. Boasting clear rivers and spectacular landscape, the area saw a political contest for control of river recreational development between two federal agencies, the National Park Service

(NPS) and the Forest Service

. Local residents opposed NPS plans that included eminent domain acquisition of private property. Both agencies presented rival bills in Congress, and in 1964 the NPS plan was selected by Congress. In the long run the NPS has successfully accommodated and supervised OSNR recreation for two million visitors a year. By contrast, the Forest Service's nearby recreational activities have handled no more than 16,000 visitors yearly.

, began promoting voluntary guidelines for increased farm production and reduced consumer use of items in short supply, Missouri met, and in many cases exceeded, the national standards.

affected nearly every aspect of Missouri's economy, particularly mining, railroading, and retailing. In 1933, the Missouri Pacific railroad declared bankruptcy; retail sales declined statewide by 50 percent, and more than 300 Missouri banks failed in the early 1930s. St. Louis manufacturing declined in value from more than $600 million in 1929 to $339 million in 1935; despite industrial diversification in the city, output fell more and unemployment was greater than the rest of country by the mid-1930s. The brick and tile industry of St. Louis virtually collapsed, dramatically altering the economic conditions of neighborhoods such as The Hill

. In response to rising discontent with the economy, the St. Louis police surveilled and harassed unemployed leftist workers, and in July 1932, a protest by the unemployed was violently broken up by police. The Depression also threatened Missouri cultural institutions such as the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, which nearly folded in 1933. Kansas City suffered from the Depression as well, although not as severely as St. Louis. Manufacturing fell in value from $220 million in 1929 to $122 million in 1935; charities were feeding 10 percent of the population by late 1932. Unlike St. Louis, Kansas City was able to supply work to many of its unemployed citizens via a $50 million bond issue that allowed for several large public works projects.

Rural Missouri suffered under the economic effects of both the Depression of natural forces. In 1930, a statewide drought struck the Ozarks and the Bootheel regions particularly hard, followed by equally deleterious droughts in 1934 and 1936. In addition, grasshoppers attacked Missouri cropland in 1936, destroying nearly a million acres of corn and other crops. Farm prices declined, and banks and insurance companies took ownership of foreclosed farmland in the Ozarks. Despite these hardships, the farm population of Missouri increased during the early years of the Depression, and unemployed urban workers sought subsistence farms throughout the state and particularly in the Ozarks.

Banks in the Ozarks frequently arranged rentals to tenant farmers, who in turn hired their sharecroppers for labor. The tenant-sharecropper system began before the Great Depression, but by 1938, there was increasing mechanization on farms. This shift allowed a single farmer to work more land, putting the sharecroppers out of work. Left-wing elements from the local Socialist movement, and from St. Louis, moved in to organize the sharecroppers into the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union. They had a highly visible, violent confrontation with state authorities in 1939.

By the late 1930s, some of the industries of the state had recovered, although not to their pre-1929 levels. Both Anheuser-Busch and the St. Louis Car Company had resumed profitable operations, and clothing and electrical product manufacturing were expanding. By 1938, the St. Louis airport handled nearly double the passengers it had in 1932, while the Kraft Cheese Company established a milk processing plant in Springfield in 1939, indicating the status of recovery in the state. However, in 1939, manufacturing as a whole remained 25 percent below its 1929 level, wholesaling was 32 percent below the 1929 level, and retail sales were 22 percent lower than they were in 1929. In early 1940, the Missouri unemployment rate remained higher than 8 percent, while urban areas had a rate at higher than 10 percent. Both St. Louis and Kansas City lost ground as industrial producers in the country.

, and roughly two-thirds were conscripted. More than 8,000 Missourians died in the conflict, the first of whom was George Whitman, killed during the Attack on Pearl Harbor

, while hospitals such as O'Reilly General in Springfield were used as military hospitals. Several Missouri soldiers became prominent during the war, such as Mildred H. McAfee

, commander of the WAVES

, Dorothy C. Stratton

, commander of the SPARS

, Walter Krueger

, commander of the Sixth United States Army, Jimmy Doolittle

, leader of the Doolittle Raid

, and Maxwell D. Taylor

, commander of the 101st Airborne Division

. The most well-known of the 89 generals and admirals from Missouri was Omar Bradley

, who led combat forces in Europe and led the single largest field command in U.S. history.

At home, Missouri residents organized air raid drills and participated in rationing and scrap drives. Missourians also purchased more than $3 billion in war bonds during the eight drives conducted for the war. Local groups and well-known figures supported the war effort as well. Missouri painter Thomas Hart Benton

created a mural series known as the The Year of Peril, and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra performed at concerts sponsored by the United Service Organizations

(USO).

The economy of Missouri was dramatically affected by the war: unemployment virtually disappeared during the early years of the war, and both St. Louis and Kansas City took steps to ensure workers were involved in essential industries. Rural areas lost population as underemployed workers, especially Southern African Americans, moved to cities to find jobs. Both teenagers and women also entered the labor force in greater numbers; in Jackson County, Missouri, roughly half of the workers at an ordnance factory and an aircraft plant were women. As a result of the departure of soldiers and higher employment rates among adults, juvenile delinquency

The economy of Missouri was dramatically affected by the war: unemployment virtually disappeared during the early years of the war, and both St. Louis and Kansas City took steps to ensure workers were involved in essential industries. Rural areas lost population as underemployed workers, especially Southern African Americans, moved to cities to find jobs. Both teenagers and women also entered the labor force in greater numbers; in Jackson County, Missouri, roughly half of the workers at an ordnance factory and an aircraft plant were women. As a result of the departure of soldiers and higher employment rates among adults, juvenile delinquency

increased, leading many Missouri communities to establish curfews and build recreational facilities for youth.Kirkendall (2004), 257.

The war brought a surge of prosperity to Missouri agriculture, and farming became a major war industry in the state. Farmers were encouraged to increase food production and to conserve other materials as much as possible, and rationing of machinery, tires, and other equipment. Despite these difficulties, many farmers modernized and learned new techniques due to the efforts of federal programs such as the Cooperative Extension Service

, the Soil Conservation Service, and the Rural Electrification Administration. The Farm Security Administration

provided loans and information to low-income farmers, and it also recruited and trained farm laborers in Missouri. As in World War I, most of the young men on the farms were deferred from the draft. Despite the significance of the agricultural industry, the population of Missouri working on farms declined 59 percent from 1939 to 1945, and the overall rural population declined 24 percent, a continuation of the trend toward urbanization in the state. The greatest declines in farm population were in agriculturally poor regions of the state, and in more suitable areas, remaining farm populations increased their mechanization of agriculture.

Manufacturing in Missouri also benefited from the war; both St. Louis and Kansas City were home to major war industries, particularly aviation in St. Louis. Kansas City also was a hub of aircraft manufacturing and development, although the city also produced a variety of military equipment as well. Railroading experienced a revival statewide with an increase in passenger and freight traffic; more than 300 freight trains and 200 passenger or troop trains transited Kansas City daily by the beginning of 1945.

The state also became home to a large military installation, Fort Leonard Wood, construction of which began in 1940 near the town of Waynesville

. Construction of the base displaced rural families, but it ultimately brought thousands of workers and economic stimulus to the area. After its construction, Fort Leonard Wood operated as a training facility for combat engineers and as a base of operations for several infantry and artillery units.

were weakened by the Depression, while black churches often provided little assistance to the needy. The black press and the National Urban League

continued to pressure local governments for equal treatment and an end to discrimination. The popularity of black nationalism also rose as a result of the Depression.

During World War II, racial tension increased in both rural and urban Missouri; in early 1942 in Sikeston

, a white mob lynched a black man in public by a white mob. Because of the potential for the incident to be used as propaganda against the United States, the the United States Department of Justice

investigated the lynching, the first time since Reconstruction that the federal government had tried to prosecute such a case. Despite the investigation, the government did not file indictments, as witnesses refused to cooperate. The following summer in Kansas City, a race riot nearly broke out after a white city police officer killed a black man.

of Kansas City and Ladue

and Creve Coeur

of St. Louis continued to exert influence beyond their size during the late 20th century. Many suburban communities began to accumulate traits of traditional, comprehensive cities by luring business and annexing area. Although the two cities of St. Louis and Kansas City continued to be the urban anchors of the state, five of the six other largest cities grew in population from 1960 to 2000.

Another area of economic change during the late 20th century was the decline of lumbering and milling. During the 1920s, as a result of overcutting, the Long-Bell Lumber Company

moved most of its Missouri operations to other states, and much of Missouri's woodlands were depleted by the 1950s. By the late 20th century, shortleaf pine forests had been largely replaced by smaller woods of hardwood trees. Despite its decline from importance, in 2001, lumbering was a $3 billion industry.

During the 1960s, lead mining again became a significant industry in Missouri as a result of the 1948 discovery of the Viburnum Trend in the New Lead Belt region of the Southeast Missouri lead district. The Old Lead Belt (also part of the Southeast Missouri lead district) suffered a slow decline, however, and the last of the mines in that region closed by 1972. Both iron and coal mining also expanded during the late 1960s; however, employment in mining declined overall during the late 20th century.

Among the fastest growing segments of the economy was the accommodation and food services industry, but it was paired with a steep decline in manufacturing. Among the greatest declines was that of stockyards and meatpacking; in 1944, Kansas City was the second-largest meatpacking city in the United States, but by the 1990s, the city had neither packing plants nor stockyards. In addition, garment manufacturing, which had previously employed thousands of workers in Kansas City prior to the 1950s, fell out of existence by the late 1990s. Statewide, another industry that declined dramatically was shoemaking, which employed fewer than 3,000 Missourians in 2001.

Despite its decline, manufacturing continued to play a role in the state's economy. Kansas City maintained a manufacturing base in its eastern Leeds industrial district, including automotive plants and an atomic weapon components plant. St. Louis maintained an industrial base with Anheuser-Busch, Monsanto, Ralston Purina, and several automotive plants. In the other four urban areas of the state (Springfield, St. Joseph, Joplin, and Columbia), the largest economic sector was manufacturing, with a combined output of more than $10 billion.

A relatively new sector of the Missouri economy developed in 1994 with the legalization of riverboat gambling in the state. The United States Army Corps of Engineers

denied riverboat gambling cruises, which in practice led to permanently moored barges with extensive superstructures. Missouri gambling also included a lottery, which had been in place for several years prior to the legalization of casino gaming.

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

claiming the territory and selling it to the U.S. in 1803. Statehood came following a compromise in 1820. Missouri grew rapidly until the Civil War, which saw numerous small battles and control by the Union. Its economy has become diverse and complex, and the state ranks in the middle of many economic and social indicators.

Explorations and indigenous peoples

In May 1673, Jesuit priest Jacques MarquetteJacques Marquette

Father Jacques Marquette S.J. , sometimes known as Père Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Ste. Marie, and later founded St. Ignace, Michigan...

and French trader Louis Jolliet

Louis Jolliet

Louis Jolliet , also known as Louis Joliet, was a French Canadian explorer known for his discoveries in North America...

sailed down the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

in canoes along the area that would later become the state of Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

. The earliest recorded use of "Missouri" is found on a map drawn by Marquette after his 1673 journey, naming both a group of Native Americans

Missouri tribe

The Missouria or Missouri are a Native American tribe that originated in the Great Lakes region of United States before European contact. The tribe belongs to the Chiwere division of the Siouan language family, together with the Iowa and Otoe...

and a nearby river

Missouri River

The Missouri River flows through the central United States, and is a tributary of the Mississippi River. It is the longest river in North America and drains the third largest area, though only the thirteenth largest by discharge. The Missouri's watershed encompasses most of the American Great...

. However, the French rarely used the word to refer to the land in the region, instead calling it part of the Illinois Country

Illinois Country

The Illinois Country , also known as Upper Louisiana, was a region in what is now the Midwestern United States that was explored and settled by the French during the 17th and 18th centuries. The terms referred to the entire Upper Mississippi River watershed, though settlement was concentrated in...

. In 1682, after his successful journey from the Great Lakes to the mouth of the Mississippi River at the Gulf of Mexico, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, or Robert de LaSalle was a French explorer. He explored the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, the Mississippi River, and the Gulf of Mexico...

claimed the Louisiana Territory

Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805 until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed to Missouri Territory...

for France. During the journey, La Salle built several trading posts in the Illinois Country in an effort to create a trading empire; however, before La Salle could fully implement his plans, he died on a second journey to the region during a mutiny in 1685.

During the late 1680s and 1690s, the French pursued colonization of central North America not only to promote trade, but also to thwart the efforts of England on the continent. In that vein, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville pronounced as described in note] Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville pronounced as described in note] Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville pronounced as described in note] (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1702 (probable)was a soldier, ship captain, explorer, colonial administrator, knight of...

and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienvillepronounce] was a colonizer, born in Montreal, Quebec and an early, repeated governor of French Louisiana, appointed 4 separate times during 1701-1743. He was a younger brother of explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville...

established Biloxi

Biloxi, Mississippi

Biloxi is a city in Harrison County, Mississippi, in the United States. The 2010 census recorded the population as 44,054. Along with Gulfport, Biloxi is a county seat of Harrison County....

in 1699 and Mobile

Mobile, Alabama

Mobile is the third most populous city in the Southern US state of Alabama and is the county seat of Mobile County. It is located on the Mobile River and the central Gulf Coast of the United States. The population within the city limits was 195,111 during the 2010 census. It is the largest...

in 1701 along the Gulf coast, while Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac

Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac

Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac was a French explorer and adventurer in New France, now an area of North America stretching from Eastern Canada in the north to Louisiana in the south. Rising from a modest beginning in Acadia in 1683 as an explorer, trapper, and a trader of alcohol...

established Detroit in 1701 along the Great Lakes. From these outposts departed a variety of fur traders and Jesuit missionaries that enabled France to build strong relationships with indigenous tribes and retain control of the continental interior.

Although both Marquette and La Salle had passed Missouri on their journeys, neither had established bases of operations in what would become the state. Encouraged by the building of Mobile and Biloxi, the first to do so was Pierre Gabriel Marest, a Jesuit priest who in late 1700 established a mission on the west bank of the Mississippi at the mouth of the River Des Peres

River des Peres

The River des Peres is a metropolitan river in St. Louis, Missouri. It is the backbone of sanitary and stormwater systems in the city of St. Louis and portions of St. Louis County...

. Marest established his mission station with a handful of French settlers and a large band of the Kaskaskia

Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation or Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in the Great Lakes region...

people, who fled from the eastern Illinois Country to the station in the hope of receiving French protection from the Iroquois. Marest became involved in learning their language and constructed several cabins, a chapel, and a basic fort at the station. However, bands of Sioux

Sioux

The Sioux are Native American and First Nations people in North America. The term can refer to any ethnic group within the Great Sioux Nation or any of the nation's many language dialects...

were angry at the encroachment of the Kaskaskia onto Sioux lands at Des Peres; these Sioux forced Marest to move the station south and east in 1703 to a new location in Illinois known as Kaskaskia

Kaskaskia, Illinois

Kaskaskia is a village in Randolph County, Illinois, United States. In the 2010 census the population was 14, making it the second-smallest incorporated community in the State of Illinois in terms of population. A major French colonial town of the Illinois Country, its peak population was about...

.

From this time up until the building of the first railways in the Mississippi Basin in the mid-19th century, the Mississippi-Missouri river system waterways were the main means of communication and transportation in the region. The earliest traffic up the Missouri likely occurred in the 1680s by unlicensed fur traders; the first known ascent occurred in 1693, and within a decade, more than a hundred traders were moving along the Mississippi and Missouri. These early traders met two tribes within what would become Missouri: the Missouri and the Osage

Osage Nation

The Osage Nation is a Native American Siouan-language tribe in the United States that originated in the Ohio River valley in present-day Kentucky. After years of war with invading Iroquois, the Osage migrated west of the Mississippi River to their historic lands in present-day Arkansas, Missouri,...

.

The Missouri were a semisedentary people with a major village along the Missouri River in northern Saline County, Missouri; they lived at the village primarily during the spring planting and fall harvesting seasons, while pursued game at other time. The Missouri became an ally of the French, eventually even traveling to Detroit to assist in the defense of the town against a Fox tribe attack. The Osage for their part became a more significant player in the development of Missouri history; they lived along the Osage River

Osage River

The Osage River is a tributary of the Missouri River in central Missouri in the United States. The Osage River is one of the larger rivers in Missouri. The river drains a mostly rural area of . The watershed includes an area of east-central Kansas and a large portion of west-central and central...

in Vernon County, Missouri and near the Missouri village in Saline County. Like the Missouri, the Osage lived in semi-permanent villages, and they also both had acquired horses.