Carthaginian Republic

Encyclopedia

Ancient Carthage was a civilization

centered on the Phoenician

city-state

of Carthage

, located in North Africa

on the Gulf of Tunis

, outside what is now Tunis

, Tunisia

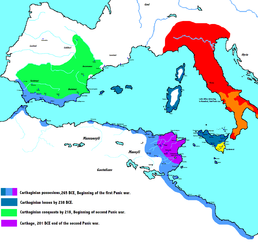

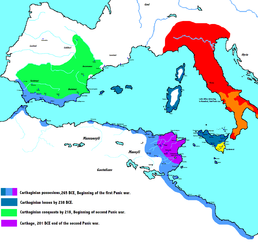

. It was founded in 814 BC. Originally a dependency of Tyre, Carthage gained independence around 650 BC and established a hegemony

over other Phoenician settlements throughout North Africa and what is now Spain which lasted until 146 BC. At the height of the city's prominence, its influence extended over most of the western Mediterranean.

Carthage was in a constant state of struggle with the Roman Republic

, which led to a series of conflicts known as the Punic Wars

. After the third and final Punic War

, Carthage was destroyed and then occupied by Roman forces. Nearly all of the other Phoenician city-states and former Carthaginian dependencies fell into Roman hands from then on.

to the succession of empires that ruled Tyre, Sidon

, and Byblos

, and by fear of complete Greek colonization of that part of the Mediterranean suitable for commerce. The Phoenicians lacked the population or necessity to establish large self-sustaining cities abroad, and most of their colonial cities had fewer than 1,000 inhabitants, but Carthage and a few others developed larger populations.

, and to a much lesser extent, on the arid coast of Libya. The Phoenicians controlled Cyprus

, Sardinia

, Corsica

, and the Balearic Islands

, as well as minor possessions in Crete

and Sicily

; the latter settlements were in perpetual conflict with the Greeks. The Phoenicians managed to control all of Sicily for a limited time. The entire area later came under the leadership and protection of Carthage, which in turn dispatched its own colonists to found new cities or to reinforce those that declined with Tyre and Sidon

.

The first colonies were made on the two paths to Iberia's mineral wealth — along the North African coast and on Sicily

, Sardinia

and the Balearic Islands

. The centre of the Phoenician world was Tyre, serving as an economic and political hub. The power of this city waned following numerous sieges and its eventual destruction by Alexander the Great, and the role as leader passed to Sidon

, and eventually to Carthage. Each colony paid tribute to either Tyre or Sidon, but neither had actual control of the colonies. This changed with the rise of Carthage, since the Carthaginians appointed their own magistrates to rule the towns and Carthage retained much direct control over the colonies. This policy resulted in a number of Iberian towns siding with the Romans during the Punic Wars

.

indicating a division of influence and commercial activities. This is the first known source indicating that Carthage had gained control over Sicily

and Sardinia

.

. The city had conquered most of the old Phoenician colonies e.g. Hadrumetum

, Utica

, and Kerkouane

, subjugated the Libyan

tribes (with the Numidian and Mauretanian kingdoms remaining more or less independent), and taken control of the entire North African coast from modern Morocco

to the borders of Egypt

(not including the Cyrenaica

, which was eventually incorporated into Hellenistic Egypt). Its influence had also extended into the Mediterranean, taking control over Sardinia

, Malta

, the Balearic Islands

, and the western half of Sicily

, where coastal fortresses such as Motya

or Lilybaeum secured its possessions. Important colonies had also been established on the Iberian peninsula

. Their cultural influence in the Iberian Peninsula

is documented, but the degree of their political influence before the conquest by Hamilcar Barca

is disputed.

of Syracuse, the other major power contending for control of the central Mediterranean.

The island of Sicily, lying at Carthage's doorstep, became the arena on which this conflict played out. From their earliest days, both the Greeks and Phoenicians had been attracted to the large island, establishing a large number of colonies and trading posts along its coast; battles had been fought between these settlements for centuries.

By 480 BC, Gelo

, the tyrant

leader of Greek Syracuse

, backed in part by support from other Greek city-states, was attempting to unite the island under his rule. This imminent threat could not be ignored, and Carthage — possibly as part of an alliance with Persia

, then engaged military force, under the leadership of the general Hamilcar

. Traditional accounts give Hamilcar's army a strength of three hundred thousand men; though these are almost certainly exaggerated, it must nonetheless have been of formidable force.

En route to Sicily, however, Hamilcar suffered losses (possibly severe) due to poor weather. Landing at Panormus (modern-day Palermo

), Hamilcar spent 3 days reorganizing his forces and repairing his battered fleet. The Carthaginians marched along the coast to Himera, and made camp before engaging in the Battle of Himera

. Hamilcar was either killed during the battle or committed suicide in shame. As a result the nobility negotiated peace and replaced the old monarchy with a republic.

, strengthened and founded new colonies in North Africa

, Hanno the Navigator

had made his journey down the African coast, and Himilco the Navigator

had explored the European Atlantic coast. Although, in that year, the Iberian colonies seceded — cutting off Carthage's major supply of silver

and copper

— Hannibal Mago

, the grandson of Hamilcar, began preparations to reclaim Sicily, while expeditions were also led into Morocco

and Senegal

, and also into the Atlantic

.

In 409 BC, Hannibal Mago set out for Sicily with his force. He was successful in capturing the smaller cities of Selinus (modern Selinunte

) and Himera

, before returning triumphantly to Carthage with the spoils of war. But the primary enemy, Syracuse, remained untouched and, in 405 BC

, Hannibal Mago led a second Carthaginian expedition to claim the entire island. This time, however, he met with fierce resistance and ill-fortune. During the siege

of Agrigentum, the Carthaginian forces were ravaged by plague, Hannibal Mago himself succumbing to it. Although his successor, Himilco

, successfully extended the campaign by breaking a Greek siege, capturing the city of Gela

and repeatedly defeating the army of Dionysius

, the new tyrant of Syracuse, he, too, was weakened by the plague and forced to sue for peace before returning to Carthage.

In 398 BC, Dionysius had regained his strength and broke the peace treaty, striking at the Carthaginian stronghold of Motya

. Himilco responded decisively, leading an expedition which not only reclaimed Motya, but also captured Messina

. Finally, he laid siege to Syracuse itself. The siege was close to a success throughout 397 BC, but in 396 BC plague again ravaged the Carthaginian forces, and they collapsed.

Sicily by this time had become an obsession for Carthage. Over the next sixty years, Carthaginian and Greek forces engaged in a constant series of skirmishes. By 340 BC, Carthage had been pushed entirely into the southwest corner of the island, and an uneasy peace reigned over the island.

In 315 BC, Agathocles

In 315 BC, Agathocles

, the tyrant (administrating governor) of Syracuse, seized the city of Messene

(present-day Messina). In 311 BC

he invaded the last Carthaginian holdings on Sicily, breaking the terms of the current peace treaty, and laid siege to Akragas.

Hamilcar

, grandson of Hanno the Navigator

, led the Carthaginian response and met with tremendous success. By 310 BC

, he controlled almost all of Sicily and had laid siege to Syracuse itself. In desperation, Agathocles secretly led an expedition of 14,000 men to the mainland, hoping to save his rule by leading a counterstrike against Carthage itself. In this, he was successful: Carthage was forced to recall Hamilcar and most of his army from Sicily to face the new and unexpected threat. Although Agathocles' army was eventually defeated in 307 BC, Agathocles himself escaped back to Sicily and was able to negotiate a peace which maintained Syracuse as a stronghold of Greek power in Sicily.

Between 280 and 275 BC, Pyrrhus of Epirus

Between 280 and 275 BC, Pyrrhus of Epirus

waged two major campaigns in the western Mediterranean: one against the emerging power of the Roman Republic

in southern Italy, the other against Carthage in Sicily.

Pyrrhus sent an advance guard to Tarentium under the command of Cineaus with 3,000 infantry

. Pyrrhus marched the main army across the Greek peninsula and engaged in battles with the Thessalians and the Athenian army. After his early success on the march Pyrrhus entered Tarentium to rejoin with his advance guard.

In the midst of Pyrrhus's Italian campaigns, he received envoys from the Sicilian cities of Agrigentum, Syracuse

, and Leontini, asking for military aid to remove the Carthaginian dominance over that island. Pyrrhus agreed, and fortified the Sicilian cities with an army of 20,000 infantry

and 3,000 cavalry

and 20 War Elephants, supported by some 200 ships. Initially, Pyrrhus' Sicilian campaign against Carthage was a success, pushing back the Carthaginian forces, and capturing the city-fortress of Eryx

, even though he was not able to capture Lilybaeum.

Following these losses, Carthage sued for peace, but Pyrrhus refused unless Carthage was willing to renounce its claims on Sicily entirely. According to Plutarch

, Pyrrhus set his sights on conquering Carthage itself, and to this end, began outfitting an expedition. However, his ruthless treatment of the Sicilian cities in his preparations for this expedition, and his execution of two Sicilian rulers whom he claimed were plotting against him led to such a rise in animosity towards the Greeks, that Pyrrhus withdrew from Sicily and returned to deal with events occurring in southern Italy.

Pyrrhus's campaigns in Italy were inconclusive, and Pyrrhus eventually withdrew to Epirus. For Carthage, this meant a return to the status quo. For Rome, however, the failure of Pyrrhus to defend the colonies of Magna Graecia

meant that Rome absorbed them into its "sphere of influence

", bringing it closer to complete domination of the Italian peninsula. Rome's domination of Italy, and proof that Rome could pit its military strength successfully against major international powers, would pave the way to the future Rome-Carthage conflicts of the Punic Wars

.

When Agathocles died in 288 BC, a large company of Italian mercenaries who had previously been held in his service found themselves suddenly without employment. Rather than leave Sicily, they seized the city of Messana. Naming themselves Mamertines

When Agathocles died in 288 BC, a large company of Italian mercenaries who had previously been held in his service found themselves suddenly without employment. Rather than leave Sicily, they seized the city of Messana. Naming themselves Mamertines

(or "sons of Mars"), they became a law unto themselves, terrorizing the surrounding countryside.

The Mamertines became a growing threat to Carthage and Syracuse alike. In 265 BC, Hiero II

, former general of Pyrrhus and the new tyrant of Syracuse, took action against them. Faced with a vastly superior force, the Mamertines divided into two factions, one advocating surrender to Carthage, the other preferring to seek aid from Rome. While the Roman Senate

debated the best course of action, the Carthaginians eagerly agreed to send a garrison to Messana. A Carthaginian garrison was admitted to the city, and a Carthaginian fleet sailed into the Messanan harbor. However, soon afterwards they began negotiating with Hiero; alarmed, the Mamertines sent another embassy to Rome asking them to expel the Carthaginians.

Hiero's intervention had placed Carthage's military forces directly across the narrow channel of water that separated Sicily from Italy. Moreover, the presence of the Carthaginian fleet gave them effective control over this channel, the Strait of Messina

, and demonstrated a clear and present danger to nearby Rome and her interests.

As a result, the Roman Assembly, although reluctant to ally with a band of mercenaries, sent an expeditionary force to return control of Messana to the Mamertines.

The Roman attack on the Carthaginian forces at Messana triggered the first of the Punic Wars

. Over the course of the next century, these three major conflicts between Rome and Carthage would determine the course of Western civilization. The wars included a Carthaginian invasion led by Hannibal

, which nearly prevented the rise of the Roman Empire

.

In 266/265 BC the Romans, under the command of Regulus

, landed in Africa and after suffering some initial defeats the Carthaginian forces eventually repelled the Roman invasion.

Shortly after the First Punic War, Carthage faced a major mercenary revolt

which changed the internal political landscape of Carthage (bringing the Barcid

family to prominence), and affected Carthage's international standing, as Rome used the events of the war to base a claim by which it seized Sardinia

and Corsica

.

The Second Punic War

lasted from 218

to 202 BC

and involved combatants in the western and eastern Mediterranean, with the participation of the Berbers

on Carthage's side. The war is marked by Hannibal's surprising overland journey and his costly crossing of the Alps, followed by his reinforcement by Gaulish allies and crushing victories over Roman armies in the battle of the Trebia

and the giant ambush at Trasimene

. Against his skill on the battlefield the Romans deployed the Fabian strategy

. But because of the increasing unpopularity of this approach, the Romans resorted to a further major field battle. The result was the Roman defeat at Cannae

.

In consequence many Roman allies went over to Carthage, prolonging the war in Italy for over a decade, during which more Roman armies were destroyed on the battlefield. Despite these setbacks, the Roman forces were more capable in siegecraft than the Carthaginians and recaptured all the major cities that had joined the enemy, as well as defeating a Carthaginian attempt to reinforce Hannibal at the battle of the Metaurus

. In the meantime in Iberia, which served as the main source of manpower for the Carthaginian army, a second Roman expedition under Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Major

took New Carthage

by assault and ended Carthaginian rule over Iberia in the battle of Ilipa

. The final showdown was the battle of Zama

in Africa between Scipio Africanus and Hannibal, resulting in the latter's defeat and the imposition of harsh peace conditions on Carthage, which ceased to be a major power and became a Roman client-state.

The Third Punic War

(149 BC

to 146 BC

) was the third and last of the Punic Wars. The war was a much smaller engagement than the two previous Punic Wars and primarily consisted of a single main action, the Battle of Carthage

, but resulted in the complete destruction of the city of Carthage, the annexation of all remaining Carthaginian territory by Rome, and the death or enslavement of the entire Carthaginian population. The Third Punic War ended Carthage's independent existence.

, a variety of Phoenician which was a Semitic

language originating in the Carthaginians' original homeland of Phoenicia

(modern Lebanon).

Carthaginian commerce was by sea throughout the Mediterranean and far into the Atlantic and by land across the Sahara desert. According to Aristotle, the Carthaginians and others had treaties of commerce to regulate their exports and imports.

Carthaginian commerce was by sea throughout the Mediterranean and far into the Atlantic and by land across the Sahara desert. According to Aristotle, the Carthaginians and others had treaties of commerce to regulate their exports and imports.

The empire of Carthage depended heavily on its trade with Tartessos

and other cities of the Iberian peninsula, from which it obtained vast quantities of silver

, lead

, and, even more importantly, tin

ore, which was essential for the manufacture of bronze

objects by the civilizations of antiquity. Its trade relations with the Iberians and the naval might that enforced Carthage's monopoly on trade with tin-rich Britain and the Canary Islands allowed it to be the sole significant broker of tin and maker of bronze. Maintaining this monopoly was one of the major sources of power and prosperity for Carthage, and a Carthaginian merchant would rather crash his ship upon the rocky shores of Britain than reveal to any rival how it could be safely approached. In addition to being the sole significant distributor of tin, its central location in the Mediterranean and control of the waters between Sicily and Tunisia allowed it to control the eastern nations' supply of tin. Carthage was also the Mediterranean's largest producer of silver, mined in Iberia and the North African coast, and, after the tin monopoly, this was one of its most profitable trades. One mine in Iberia provided Hannibal with 300 Roman pounds (3.75 talents) of silver a day.

Carthage's economy began as an extension of that of its parent city, Tyre. Its massive merchant fleet traversed the trade routes mapped out by Tyre, and Carthage inherited from Tyre the art of making the extremely valuable dye Tyrian Purple

. It was one of the most highly valued commodities in the ancient Mediterranean, being worth fifteen to twenty times its weight in gold. High Roman officials could only afford togas with a small stripe of it. Carthage also produced a less-valuable crimson pigment from the kermes

, a scale insect

local to the area.

Carthage produced finely embroidered and dyed textiles of cotton

, linen

, wool

, and silk

, artistic and functional pottery

, faience

, incense

, and perfumes. Its artisans worked with glass, wood, alabaster

, ivory, bronze, brass, lead, gold, silver, and precious stones to create a wide array of goods, including mirrors, highly admired furniture and cabinetry, beds, bedding, and pillows, jewelry, arms, implements, and household items. It traded in salted Atlantic fish and fish sauce, and brokered the manufactured, agricultural, and natural products of almost every Mediterranean people.

In addition to manufacturing, Carthage practised highly advanced and productive agriculture, using iron ploughs, irrigation, and crop rotation. Mago

In addition to manufacturing, Carthage practised highly advanced and productive agriculture, using iron ploughs, irrigation, and crop rotation. Mago

wrote a famous treatise on agriculture which the Romans ordered translated after Carthage was captured. After the Second Punic War, Hannibal

promoted agriculture to help restore Carthage's economy and pay the war indemnity to Rome (10,000 talents or 800,000 Roman pounds of silver), and he was largely successful.

Carthage produced wine, which was highly prized in Rome, Etruria

(the Etruscans), and Greece. Rome was a major consumer of raisin wine, a Carthaginian specialty. Fruits, nuts, grain, grapes, dates, and olives were grown, and olive oil was exported in competition with Greece. Carthage also raised fine horses, similar to today's Arabian horse

s, which were greatly prized and exported.

Carthage's merchant ships, which surpassed even those of the cities of the Levant

, visited every major port of the Mediterranean, Britain, the coast of Africa, and the Canary Islands

. These ships were able to carry over 100 tons of goods. The commercial fleet of Carthage was comparable in size and tonnage to the fleets of major European powers in the 18th century.

Merchants at first favored the ports of the east: Egypt, the Levant, Greece, Cyprus, and Asia Minor. But after Carthage's control of Sicily brought it into conflict with Greek colonists, it established commercial relations in the western Mediterranean, including trade with the Etruscans.

Carthage also sent caravans into the interior of Africa and Persia. It traded its manufactured and agricultural goods to the coastal and interior peoples of Africa for salt, gold, timber, ivory, ebony, apes, peacocks, skins, and hides. Its merchants invented the practice of sale by auction and used it to trade with the African tribes. In other ports, they tried to establish permanent warehouses or sell their goods in open-air markets. They obtained amber from Scandinavia and tin from the Canary Islands. From the Celtiberians, Gauls, and Celts, they obtained amber, tin, silver, and furs. Sardinia and Corsica produced gold and silver for Carthage, and Phoenician settlements on islands such as Malta

and the Balearic Islands

produced commodities that would be sent back to Carthage for large-scale distribution. Carthage supplied poorer civilizations with simple things, such as pottery, metallic products, and ornamentations, often displacing the local manufacturing, but brought its best works to wealthier ones such as the Greeks and Etruscans. Carthage traded in almost every commodity wanted by the ancient world, including spices from Arabia, Africa and India, and slaves (the empire of Carthage temporarily held a portion of Europe and sent conquered white warriors into Northern African slavery).

These trade ships went all the way down the Atlantic coast of Africa to Senegal

and Nigeria. One account has a Carthaginian trading vessel exploring Nigeria, including identification of distinguishing geographic features such as a coastal volcano and an encounter with gorillas (See Hanno the Navigator

). Irregular trade exchanges occurred as far west as Madeira and the Canary Islands

, and as far south as southern Africa. Carthage also traded with India

by traveling through the Red Sea

and the perhaps-mythical lands of Ophir

(India/Arabia?) and Punt

, which may be present-day Somalia

.

Archaeological finds show evidence of all kinds of exchanges, from the vast quantities of tin needed for a bronze-based metals civilization to all manner of textiles, ceramics and fine metalwork. Before and in between the wars, Carthaginian merchants were in every port in the Mediterranean, buying and selling, establishing warehouses where they could, or just bargaining in open-air markets after getting off their ships.

The Etruscan language has not yet been deciphered, but archaeological excavations of Etruscan cities show that the Etruscan civilization was for several centuries a customer and a vendor to Carthage, long before the rise of Rome. The Etruscan city-states were, at times, both commercial partners of Carthage and military allies.

The government of Carthage was an oligarchal

The government of Carthage was an oligarchal

republic

, which relied on a system of checks and balances and ensured a form of public accountability. The Carthaginian heads of state were called Suffets

(thus rendered in Latin by Livy

30.7.5, attested in Punic inscriptions as SPΘM /ʃuftˤim/, meaning "judges" and obviously related to the Biblical

Hebrew

ruler title "Judge

"). Greek and Roman authors more commonly referred to them as "kings". SPΘ /ʃufitˤ/ might originally have been the title of the city's governor, installed by the mother city of Tyre.

In the historically attested period, the two Suffets were elected annually from among the most wealthy and influential families and ruled collegially, similarly to Roman consul

s (and equated with these by Livy). This practice might have descended from the plutocratic

oligarchies that limited the Suffet's power in the first Phoenician cities. The aristocratic families were represented in a supreme council (Roman sources speak of a Carthaginian "Senate

", and Greek ones of a "council of Elders

" or a gerousia

), which had a wide range of powers; however, it is not known whether the Suffets were elected by this council or by an assembly of the people. Suffets appear to have exercised judicial and executive power, but not military .

Although the city's administration was firmly controlled by oligarchs , democratic elements were to be found as well: Carthage had elected legislators, trade unions and town meetings. Aristotle

reported in his Politics

that unless the Suffets and the Council reached a unanimous decision, the Carthaginian popular assembly had the decisive vote - unlike the situation in Greek states with similar constitutions such as Sparta

and Crete

.

Polybius

, in his History book 6, also stated that at the time of the Punic Wars, the Carthaginian public held more sway over the government than the people of Rome held over theirs (a development he regarded as evidence of decline). Finally, there was a body known as the Hundred and Four

, which Aristotle compared to the Spartan ephors. These were judges who oversaw the actions of generals , who could sometimes be sentenced to crucifixion

.

Eratosthenes

, head of the Library of Alexandria

, noted that the Greeks had been wrong to describe all non-Greeks as barbarians, since the Carthaginians as well as the Romans had a constitution. Aristotle

also knew and discussed the Carthaginian constitution in his Politics (Book II, Chapter 11). During the period between the end of the First Punic War and the end of the Second Punic War, members of the Barcid

family dominated in Carthaginian politics. They were given control of the Carthaginian military and all the Carthaginian territories outside of Africa.

), a form of polytheism

. Many of the gods the Carthaginians worshiped were localized and are now known only under their local names. It also had Jewish communities (which still exist; see Tunisian Jews and Algerian Jews).

and Ba'al Hammon. The goddess Astarte

seems to have been popular in early times. At the height of its cosmopolitan era, Carthage seems to have hosted a large array of divinities from the neighbouring civilizations of Greece, Egypt and the Etruscan city-states. A pantheon was presided over by the father of the gods, but a goddess was the principal figure in the Phoenician pantheon.

Cippi and stelae of limestone are characteristic monuments of Punic art and religion, and are found throughout the western Phoenician world in unbroken continuity, both historically and geographically. Most of them were set up over urns containing cremated human remains, placed within open-air sanctuaries. Such sanctuaries constitute striking relics of Punic civilization.

Cippi and stelae of limestone are characteristic monuments of Punic art and religion, and are found throughout the western Phoenician world in unbroken continuity, both historically and geographically. Most of them were set up over urns containing cremated human remains, placed within open-air sanctuaries. Such sanctuaries constitute striking relics of Punic civilization.

. Plutarch

(c. 46–120) mentions the practice, as do Tertullian

, Orosius, Philo

and Diodorus Siculus

. However, Herodotos and Polybius

do not. Skeptics contend that if Carthage's critics were aware of such a practice, however limited, they would have been horrified by it and exaggerated its extent due to their polemical treatment of the Carthaginians. The Hebrew Bible

also mentions child sacrifice practiced by the Canaan

ites, ancestors of the Carthaginians. The Greek and Roman critics, according to Charles Picard, objected not to the killing of children but to the religious nature of it. As in both ancient Greece and Rome, inconvenient children were not uncommonly killed by exposure to the elements. However, the Greeks and Romans engaged in the practice for economic rather than religious reasons.

Modern archaeology

in formerly Punic areas has discovered a number of large cemeteries for children and infants. These cemeteries may have been used as graves for stillborn

infants or children who died very early. Modern archeological excavations have been interpreted as confirming Plutarch's reports of Carthaginian child sacrifice. In a single child cemetery called the Tophet

by archaeologists, an estimated 20,000 urns were deposited between 400 BC and 200 BC, with the practice continuing until the early years of the Christian period. The urns contained the charred bones of newborns and in some cases the bones of fetuses and 2-year-olds. These remains have been interpreted to mean that in the cases of stillborn babies, the parents would sacrifice their youngest child. There is a clear correlation between the frequency of cremation and the well-being of the city. In bad times (war, poor harvests) cremations became more frequent, but it is not possible to know why. The correlation could be because bad times inspired the Carthaginians to pray for divine intervention (via child sacrifice), or because bad times increased child mortality, leading to more child burials (via cremation).

Accounts of child sacrifice in Carthage report that beginning at the founding of Carthage in about 814 BC, mothers and fathers buried their children who had been sacrificed to Ba`al Hammon and Tanit in Tophet. The practice was apparently distasteful even to Carthaginians, and they began to buy children for the purpose of sacrifice or even to raise servant children instead of offering up their own. However, Carthage's priests demanded the flower of their youth in times of crisis or calamity like war, drought or famine. Special ceremonies during extreme crisis saw up to 200 children of the most affluent and powerful families slain and tossed into the burning pyre.

Skeptics suggest that the bodies of children found in Carthaginian and Phoenician cemeteries were merely the cremated remains of children who died naturally. Sergio Ribichini has argued that the Tophet was "a child necropolis designed to receive the remains of infants who had died prematurely of sickness or other natural causes, and who for this reason were "offered" to specific deities and buried in a place different from the one reserved for the ordinary dead". The few Carthaginian texts which have survived make absolutely no mention of child sacrifice, though most of them pertain to matters entirely unrelated to religion, such as the practice of agriculture.

Civilization

Civilization is a sometimes controversial term that has been used in several related ways. Primarily, the term has been used to refer to the material and instrumental side of human cultures that are complex in terms of technology, science, and division of labor. Such civilizations are generally...

centered on the Phoenician

Phoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

city-state

City-state

A city-state is an independent or autonomous entity whose territory consists of a city which is not administered as a part of another local government.-Historical city-states:...

of Carthage

Carthage

Carthage , implying it was a 'new Tyre') is a major urban centre that has existed for nearly 3,000 years on the Gulf of Tunis, developing from a Phoenician colony of the 1st millennium BC...

, located in North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

on the Gulf of Tunis

Gulf of Tunis

Gulf of Tunis is a large gulf in northeastern Tunisia. It is located at around . Tunis, the capital city of Tunisia, lies at the southern edge of the Gulf, as have a series of settled places over the last three millennia....

, outside what is now Tunis

Tunis

Tunis is the capital of both the Tunisian Republic and the Tunis Governorate. It is Tunisia's largest city, with a population of 728,453 as of 2004; the greater metropolitan area holds some 2,412,500 inhabitants....

, Tunisia

Tunisia

Tunisia , officially the Tunisian RepublicThe long name of Tunisia in other languages used in the country is: , is the northernmost country in Africa. It is a Maghreb country and is bordered by Algeria to the west, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Its area...

. It was founded in 814 BC. Originally a dependency of Tyre, Carthage gained independence around 650 BC and established a hegemony

Hegemony

Hegemony is an indirect form of imperial dominance in which the hegemon rules sub-ordinate states by the implied means of power rather than direct military force. In Ancient Greece , hegemony denoted the politico–military dominance of a city-state over other city-states...

over other Phoenician settlements throughout North Africa and what is now Spain which lasted until 146 BC. At the height of the city's prominence, its influence extended over most of the western Mediterranean.

Carthage was in a constant state of struggle with the Roman Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

, which led to a series of conflicts known as the Punic Wars

Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 B.C.E. to 146 B.C.E. At the time, they were probably the largest wars that had ever taken place...

. After the third and final Punic War

Third Punic War

The Third Punic War was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between the former Phoenician colony of Carthage, and the Roman Republic...

, Carthage was destroyed and then occupied by Roman forces. Nearly all of the other Phoenician city-states and former Carthaginian dependencies fell into Roman hands from then on.

Extent of Phoenician settlement

In order to provide safe harbors for their merchant fleets, or to maintain a Phoenician monopoly on an area's natural resources, or to conduct trade free of outside interference, the Phoenicians established numerous colonial cities along the coasts of the Mediterranean. They were also stimulated to found these cities by a need for revitalizing trade in order to pay tributeTribute

A tribute is wealth, often in kind, that one party gives to another as a sign of respect or, as was often the case in historical contexts, of submission or allegiance. Various ancient states, which could be called suzerains, exacted tribute from areas they had conquered or threatened to conquer...

to the succession of empires that ruled Tyre, Sidon

Sidon

Sidon or Saïda is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate of Lebanon, on the Mediterranean coast, about 40 km north of Tyre and 40 km south of the capital Beirut. In Genesis, Sidon is the son of Canaan the grandson of Noah...

, and Byblos

Byblos

Byblos is the Greek name of the Phoenician city Gebal . It is a Mediterranean city in the Mount Lebanon Governorate of present-day Lebanon under the current Arabic name of Jubayl and was also referred to as Gibelet during the Crusades...

, and by fear of complete Greek colonization of that part of the Mediterranean suitable for commerce. The Phoenicians lacked the population or necessity to establish large self-sustaining cities abroad, and most of their colonial cities had fewer than 1,000 inhabitants, but Carthage and a few others developed larger populations.

Carthaginian Control

Some 300 colonies were established in Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, IberiaIberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

, and to a much lesser extent, on the arid coast of Libya. The Phoenicians controlled Cyprus

Cyprus

Cyprus , officially the Republic of Cyprus , is a Eurasian island country, member of the European Union, in the Eastern Mediterranean, east of Greece, south of Turkey, west of Syria and north of Egypt. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.The earliest known human activity on the...

, Sardinia

Sardinia

Sardinia is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea . It is an autonomous region of Italy, and the nearest land masses are the French island of Corsica, the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Tunisia and the Spanish Balearic Islands.The name Sardinia is from the pre-Roman noun *sard[],...

, Corsica

Corsica

Corsica is an island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is located west of Italy, southeast of the French mainland, and north of the island of Sardinia....

, and the Balearic Islands

Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago of Spain in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula.The four largest islands are: Majorca, Minorca, Ibiza and Formentera. The archipelago forms an autonomous community and a province of Spain with Palma as the capital...

, as well as minor possessions in Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

and Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

; the latter settlements were in perpetual conflict with the Greeks. The Phoenicians managed to control all of Sicily for a limited time. The entire area later came under the leadership and protection of Carthage, which in turn dispatched its own colonists to found new cities or to reinforce those that declined with Tyre and Sidon

Sidon

Sidon or Saïda is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate of Lebanon, on the Mediterranean coast, about 40 km north of Tyre and 40 km south of the capital Beirut. In Genesis, Sidon is the son of Canaan the grandson of Noah...

.

The first colonies were made on the two paths to Iberia's mineral wealth — along the North African coast and on Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

, Sardinia

Sardinia

Sardinia is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea . It is an autonomous region of Italy, and the nearest land masses are the French island of Corsica, the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Tunisia and the Spanish Balearic Islands.The name Sardinia is from the pre-Roman noun *sard[],...

and the Balearic Islands

Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago of Spain in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula.The four largest islands are: Majorca, Minorca, Ibiza and Formentera. The archipelago forms an autonomous community and a province of Spain with Palma as the capital...

. The centre of the Phoenician world was Tyre, serving as an economic and political hub. The power of this city waned following numerous sieges and its eventual destruction by Alexander the Great, and the role as leader passed to Sidon

Sidon

Sidon or Saïda is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate of Lebanon, on the Mediterranean coast, about 40 km north of Tyre and 40 km south of the capital Beirut. In Genesis, Sidon is the son of Canaan the grandson of Noah...

, and eventually to Carthage. Each colony paid tribute to either Tyre or Sidon, but neither had actual control of the colonies. This changed with the rise of Carthage, since the Carthaginians appointed their own magistrates to rule the towns and Carthage retained much direct control over the colonies. This policy resulted in a number of Iberian towns siding with the Romans during the Punic Wars

Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 B.C.E. to 146 B.C.E. At the time, they were probably the largest wars that had ever taken place...

.

Treaty with Rome

In 509 BC, a treaty was signed between Carthage and RomeAncient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

indicating a division of influence and commercial activities. This is the first known source indicating that Carthage had gained control over Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

and Sardinia

Sardinia

Sardinia is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea . It is an autonomous region of Italy, and the nearest land masses are the French island of Corsica, the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Tunisia and the Spanish Balearic Islands.The name Sardinia is from the pre-Roman noun *sard[],...

.

5th Century

By the beginning of the 5th century BC, Carthage had become the commercial center of the West Mediterranean region, a position it retained until overthrown by the Roman RepublicRoman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

. The city had conquered most of the old Phoenician colonies e.g. Hadrumetum

Hadrumetum

Hadrumetum was a Phoenician colony that pre-dated Carthage and stood on the site of modern-day Sousse, Tunisia.-Ancient history:...

, Utica

Utica, Tunisia

Utica is an ancient city northwest of Carthage near the outflow of the Medjerda River into the Mediterranean Sea, traditionally considered to be the first colony founded by the Phoenicians in North Africa...

, and Kerkouane

Kerkouane

Kerkouane is a Punic city in northeastern Tunisia, near Cape Bon. This Phoenician city was probably abandoned during the First Punic War , and as a result was not rebuilt by the Romans. It had existed for almost 400 years....

, subjugated the Libyan

Ancient Libya

The Latin name Libya referred to the region west of the Nile Valley, generally corresponding to modern Northwest Africa. Climate changes affected the locations of the settlements....

tribes (with the Numidian and Mauretanian kingdoms remaining more or less independent), and taken control of the entire North African coast from modern Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

to the borders of Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

(not including the Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica is the eastern coastal region of Libya.Also known as Pentapolis in antiquity, it was part of the Creta et Cyrenaica province during the Roman period, later divided in Libia Pentapolis and Libia Sicca...

, which was eventually incorporated into Hellenistic Egypt). Its influence had also extended into the Mediterranean, taking control over Sardinia

Sardinia

Sardinia is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea . It is an autonomous region of Italy, and the nearest land masses are the French island of Corsica, the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Tunisia and the Spanish Balearic Islands.The name Sardinia is from the pre-Roman noun *sard[],...

, Malta

Malta

Malta , officially known as the Republic of Malta , is a Southern European country consisting of an archipelago situated in the centre of the Mediterranean, south of Sicily, east of Tunisia and north of Libya, with Gibraltar to the west and Alexandria to the east.Malta covers just over in...

, the Balearic Islands

Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago of Spain in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula.The four largest islands are: Majorca, Minorca, Ibiza and Formentera. The archipelago forms an autonomous community and a province of Spain with Palma as the capital...

, and the western half of Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

, where coastal fortresses such as Motya

Motya

Motya , was an ancient and powerful city on an island off the west coast of Sicily, between Drepanum and Lilybaeum...

or Lilybaeum secured its possessions. Important colonies had also been established on the Iberian peninsula

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

. Their cultural influence in the Iberian Peninsula

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

is documented, but the degree of their political influence before the conquest by Hamilcar Barca

Hamilcar Barca

Hamilcar Barca or Barcas was a Carthaginian general and statesman, leader of the Barcid family, and father of Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Mago. He was also father-in-law to Hasdrubal the Fair....

is disputed.

First Sicilian war

Carthage's economic successes, and its dependence on shipping to conduct most of its trade, led to the creation of a powerful Carthaginian navy. This, coupled with its success and growing hegemony, brought Carthage into increasing conflict with the GreeksGreeks

The Greeks, also known as the Hellenes , are a nation and ethnic group native to Greece, Cyprus and neighboring regions. They also form a significant diaspora, with Greek communities established around the world....

of Syracuse, the other major power contending for control of the central Mediterranean.

The island of Sicily, lying at Carthage's doorstep, became the arena on which this conflict played out. From their earliest days, both the Greeks and Phoenicians had been attracted to the large island, establishing a large number of colonies and trading posts along its coast; battles had been fought between these settlements for centuries.

By 480 BC, Gelo

Gelo

Gelo , son of Deinomenes, was a 5th century BC ruler of Gela and Syracuse and first of the Deinomenid rulers.- Early life :...

, the tyrant

Tyrant

A tyrant was originally one who illegally seized and controlled a governmental power in a polis. Tyrants were a group of individuals who took over many Greek poleis during the uprising of the middle classes in the sixth and seventh centuries BC, ousting the aristocratic governments.Plato and...

leader of Greek Syracuse

Syracuse, Italy

Syracuse is a historic city in Sicily, the capital of the province of Syracuse. The city is notable for its rich Greek history, culture, amphitheatres, architecture, and as the birthplace of the preeminent mathematician and engineer Archimedes. This 2,700-year-old city played a key role in...

, backed in part by support from other Greek city-states, was attempting to unite the island under his rule. This imminent threat could not be ignored, and Carthage — possibly as part of an alliance with Persia

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

, then engaged military force, under the leadership of the general Hamilcar

Hamilcar

Hamilcar was a common name in the Punic culture. There are several different transcriptions into Greek and Roman scripts. The ruling families of ancient Carthage often named their members with the traditional name Hamilcar...

. Traditional accounts give Hamilcar's army a strength of three hundred thousand men; though these are almost certainly exaggerated, it must nonetheless have been of formidable force.

En route to Sicily, however, Hamilcar suffered losses (possibly severe) due to poor weather. Landing at Panormus (modern-day Palermo

Palermo

Palermo is a city in Southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Province of Palermo. The city is noted for its history, culture, architecture and gastronomy, playing an important role throughout much of its existence; it is over 2,700 years old...

), Hamilcar spent 3 days reorganizing his forces and repairing his battered fleet. The Carthaginians marched along the coast to Himera, and made camp before engaging in the Battle of Himera

Battle of Himera (480 BC)

The Battle of Himera , supposedly fought on the same day as the more famous Battle of Salamis, or on the same day as the Battle of Thermopylae, saw the Greek forces of Gelon, King of Syracuse, and Theron, tyrant of Agrigentum, defeat the Carthaginian force of Hamilcar the Magonid, ending a...

. Hamilcar was either killed during the battle or committed suicide in shame. As a result the nobility negotiated peace and replaced the old monarchy with a republic.

Second Sicilian War

By 410 BC, Carthage had recovered after serious defeats. It had conquered much of modern day TunisiaTunisia

Tunisia , officially the Tunisian RepublicThe long name of Tunisia in other languages used in the country is: , is the northernmost country in Africa. It is a Maghreb country and is bordered by Algeria to the west, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Its area...

, strengthened and founded new colonies in North Africa

Maghreb

The Maghreb is the region of Northwest Africa, west of Egypt. It includes five countries: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania and the disputed territory of Western Sahara...

, Hanno the Navigator

Hanno the Navigator

Hanno the Navigator was a Carthaginian explorer c. 500 BC, best known for his naval exploration of the African coast...

had made his journey down the African coast, and Himilco the Navigator

Himilco the Navigator

Himilco , a Carthaginian navigator and explorer, lived during the height of Carthaginian power, the 5th century BC....

had explored the European Atlantic coast. Although, in that year, the Iberian colonies seceded — cutting off Carthage's major supply of silver

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

and copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

— Hannibal Mago

Hannibal Mago

Hannibal was a grandson of Hamilcar Mago.He was shofet of Carthage in 410 BC and in 409 BC commanded a Carthaginian army sent to Sicily in response to a request from the city of Segesta. He successfully took the Greek city of Selinus and then Himera...

, the grandson of Hamilcar, began preparations to reclaim Sicily, while expeditions were also led into Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

and Senegal

Senegal

Senegal , officially the Republic of Senegal , is a country in western Africa. It owes its name to the Sénégal River that borders it to the east and north...

, and also into the Atlantic

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

.

In 409 BC, Hannibal Mago set out for Sicily with his force. He was successful in capturing the smaller cities of Selinus (modern Selinunte

Selinunte

Selinunte is an ancient Greek archaeological site on the south coast of Sicily, southern Italy, between the valleys of the rivers Belice and Modione in the province of Trapani. The archaeological site contains five temples centered on an acropolis...

) and Himera

Himera

thumb|250px|Remains of the Temple of Victory.thumb|250px|Ideal reconstruction of the Temple of Victory.Himera , was an important ancient Greek city of Sicily, situated on the north coast of the island, at the mouth of the river of the same name , between Panormus and Cephaloedium...

, before returning triumphantly to Carthage with the spoils of war. But the primary enemy, Syracuse, remained untouched and, in 405 BC

405 BC

Year 405 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Tribunate of Barbatus, Capitolinus, Cincinnatus, Medullinus, Iullus and Mamercinus...

, Hannibal Mago led a second Carthaginian expedition to claim the entire island. This time, however, he met with fierce resistance and ill-fortune. During the siege

Siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city or fortress with the intent of conquering by attrition or assault. The term derives from sedere, Latin for "to sit". Generally speaking, siege warfare is a form of constant, low intensity conflict characterized by one party holding a strong, static...

of Agrigentum, the Carthaginian forces were ravaged by plague, Hannibal Mago himself succumbing to it. Although his successor, Himilco

Himilco

Himilco was the Carthaginian sailor a.k.a. Himilco the Navigator.Himilco may also refer to:* Himilco , Carthaginian soldier at Battle of Messene...

, successfully extended the campaign by breaking a Greek siege, capturing the city of Gela

Gela

Gela is a town and comune in the province of Caltanissetta in the south of Sicily, Italy. The city is at about 84 kilometers distance from the city of Caltanissetta, on the Mediterranean Sea. The city has a larger population than the provincial capital, and ranks second in land area.Gela is an...

and repeatedly defeating the army of Dionysius

Dionysius I of Syracuse

Dionysius I or Dionysius the Elder was a Greek tyrant of Syracuse, in what is now Sicily, southern Italy. He conquered several cities in Sicily and southern Italy, opposed Carthage's influence in Sicily and made Syracuse the most powerful of the Western Greek colonies...

, the new tyrant of Syracuse, he, too, was weakened by the plague and forced to sue for peace before returning to Carthage.

In 398 BC, Dionysius had regained his strength and broke the peace treaty, striking at the Carthaginian stronghold of Motya

Motya

Motya , was an ancient and powerful city on an island off the west coast of Sicily, between Drepanum and Lilybaeum...

. Himilco responded decisively, leading an expedition which not only reclaimed Motya, but also captured Messina

Messina, Italy

Messina is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, Italy and the capital of the province of Messina. It has a population of about 250,000 inhabitants in the city proper and about 650,000 in the province...

. Finally, he laid siege to Syracuse itself. The siege was close to a success throughout 397 BC, but in 396 BC plague again ravaged the Carthaginian forces, and they collapsed.

Sicily by this time had become an obsession for Carthage. Over the next sixty years, Carthaginian and Greek forces engaged in a constant series of skirmishes. By 340 BC, Carthage had been pushed entirely into the southwest corner of the island, and an uneasy peace reigned over the island.

Third Sicilian War

Agathocles

Agathocles , , was tyrant of Syracuse and king of Sicily .-Biography:...

, the tyrant (administrating governor) of Syracuse, seized the city of Messene

Messene

Messene , officially Ancient Messene, is a Local Community of the Municipal Unit , Ithomi, of the municipality of Messini within the Regional Unit of Messenia in the Region of Peloponnēsos, one of 7 Regions into which the Hellenic Republic has been divided by the Kallikratis...

(present-day Messina). In 311 BC

311 BC

Year 311 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Brutus and Barbula...

he invaded the last Carthaginian holdings on Sicily, breaking the terms of the current peace treaty, and laid siege to Akragas.

Hamilcar

Hamilcar

Hamilcar was a common name in the Punic culture. There are several different transcriptions into Greek and Roman scripts. The ruling families of ancient Carthage often named their members with the traditional name Hamilcar...

, grandson of Hanno the Navigator

Hanno the Navigator

Hanno the Navigator was a Carthaginian explorer c. 500 BC, best known for his naval exploration of the African coast...

, led the Carthaginian response and met with tremendous success. By 310 BC

310 BC

Year 310 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Rullianus and Censorinus...

, he controlled almost all of Sicily and had laid siege to Syracuse itself. In desperation, Agathocles secretly led an expedition of 14,000 men to the mainland, hoping to save his rule by leading a counterstrike against Carthage itself. In this, he was successful: Carthage was forced to recall Hamilcar and most of his army from Sicily to face the new and unexpected threat. Although Agathocles' army was eventually defeated in 307 BC, Agathocles himself escaped back to Sicily and was able to negotiate a peace which maintained Syracuse as a stronghold of Greek power in Sicily.

Pyrrhic War

Pyrrhus of Epirus

Pyrrhus or Pyrrhos was a Greek general and statesman of the Hellenistic era. He was king of the Greek tribe of Molossians, of the royal Aeacid house , and later he became king of Epirus and Macedon . He was one of the strongest opponents of early Rome...

waged two major campaigns in the western Mediterranean: one against the emerging power of the Roman Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

in southern Italy, the other against Carthage in Sicily.

Pyrrhus sent an advance guard to Tarentium under the command of Cineaus with 3,000 infantry

Infantry

Infantrymen are soldiers who are specifically trained for the role of fighting on foot to engage the enemy face to face and have historically borne the brunt of the casualties of combat in wars. As the oldest branch of combat arms, they are the backbone of armies...

. Pyrrhus marched the main army across the Greek peninsula and engaged in battles with the Thessalians and the Athenian army. After his early success on the march Pyrrhus entered Tarentium to rejoin with his advance guard.

In the midst of Pyrrhus's Italian campaigns, he received envoys from the Sicilian cities of Agrigentum, Syracuse

Syracuse, Italy

Syracuse is a historic city in Sicily, the capital of the province of Syracuse. The city is notable for its rich Greek history, culture, amphitheatres, architecture, and as the birthplace of the preeminent mathematician and engineer Archimedes. This 2,700-year-old city played a key role in...

, and Leontini, asking for military aid to remove the Carthaginian dominance over that island. Pyrrhus agreed, and fortified the Sicilian cities with an army of 20,000 infantry

Infantry

Infantrymen are soldiers who are specifically trained for the role of fighting on foot to engage the enemy face to face and have historically borne the brunt of the casualties of combat in wars. As the oldest branch of combat arms, they are the backbone of armies...

and 3,000 cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

and 20 War Elephants, supported by some 200 ships. Initially, Pyrrhus' Sicilian campaign against Carthage was a success, pushing back the Carthaginian forces, and capturing the city-fortress of Eryx

Erice

Erice is a historic town and comune in the province of Trapani in Sicily, Italy.Erice is located on top of Mount Erice, at around 750m above sea level, overlooking the city of Trapani, the low western coast towards Marsala, the dramatic Punta del Saraceno and Capo san Vito to the north-east, and...

, even though he was not able to capture Lilybaeum.

Following these losses, Carthage sued for peace, but Pyrrhus refused unless Carthage was willing to renounce its claims on Sicily entirely. According to Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

, Pyrrhus set his sights on conquering Carthage itself, and to this end, began outfitting an expedition. However, his ruthless treatment of the Sicilian cities in his preparations for this expedition, and his execution of two Sicilian rulers whom he claimed were plotting against him led to such a rise in animosity towards the Greeks, that Pyrrhus withdrew from Sicily and returned to deal with events occurring in southern Italy.

Pyrrhus's campaigns in Italy were inconclusive, and Pyrrhus eventually withdrew to Epirus. For Carthage, this meant a return to the status quo. For Rome, however, the failure of Pyrrhus to defend the colonies of Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia

Magna Græcia is the name of the coastal areas of Southern Italy on the Tarentine Gulf that were extensively colonized by Greek settlers; particularly the Achaean colonies of Tarentum, Crotone, and Sybaris, but also, more loosely, the cities of Cumae and Neapolis to the north...

meant that Rome absorbed them into its "sphere of influence

Sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence is a spatial region or conceptual division over which a state or organization has significant cultural, economic, military or political influence....

", bringing it closer to complete domination of the Italian peninsula. Rome's domination of Italy, and proof that Rome could pit its military strength successfully against major international powers, would pave the way to the future Rome-Carthage conflicts of the Punic Wars

Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 B.C.E. to 146 B.C.E. At the time, they were probably the largest wars that had ever taken place...

.

The Punic Wars

Mamertines

The Mamertines were mercenaries of Italian origin who had been hired from their home in Campania by Agathocles, the king of Syracuse. After Syracuse lost the Third Sicilian War, the city of Messana was ceded to Carthage in 307 BC. When Agathocles died in 289 BC he left many of his mercenaries idle...

(or "sons of Mars"), they became a law unto themselves, terrorizing the surrounding countryside.

The Mamertines became a growing threat to Carthage and Syracuse alike. In 265 BC, Hiero II

Hiero II of Syracuse

Hieron II , king of Syracuse from 270 to 215 BC, was the illegitimate son of a Syracusan noble, Hierocles, who claimed descent from Gelon. He was a former general of Pyrrhus of Epirus and an important figure of the First Punic War....

, former general of Pyrrhus and the new tyrant of Syracuse, took action against them. Faced with a vastly superior force, the Mamertines divided into two factions, one advocating surrender to Carthage, the other preferring to seek aid from Rome. While the Roman Senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

debated the best course of action, the Carthaginians eagerly agreed to send a garrison to Messana. A Carthaginian garrison was admitted to the city, and a Carthaginian fleet sailed into the Messanan harbor. However, soon afterwards they began negotiating with Hiero; alarmed, the Mamertines sent another embassy to Rome asking them to expel the Carthaginians.

Hiero's intervention had placed Carthage's military forces directly across the narrow channel of water that separated Sicily from Italy. Moreover, the presence of the Carthaginian fleet gave them effective control over this channel, the Strait of Messina

Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina is the narrow passage between the eastern tip of Sicily and the southern tip of Calabria in the south of Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian Sea with the Ionian Sea, within the central Mediterranean...

, and demonstrated a clear and present danger to nearby Rome and her interests.

As a result, the Roman Assembly, although reluctant to ally with a band of mercenaries, sent an expeditionary force to return control of Messana to the Mamertines.

The Roman attack on the Carthaginian forces at Messana triggered the first of the Punic Wars

Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 B.C.E. to 146 B.C.E. At the time, they were probably the largest wars that had ever taken place...

. Over the course of the next century, these three major conflicts between Rome and Carthage would determine the course of Western civilization. The wars included a Carthaginian invasion led by Hannibal

Hannibal Barca

Hannibal, son of Hamilcar Barca Hannibal's date of death is most commonly given as 183 BC, but there is a possibility it could have taken place in 182 BC. was a Carthaginian military commander and tactician. He is generally considered one of the greatest military commanders in history...

, which nearly prevented the rise of the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

.

In 266/265 BC the Romans, under the command of Regulus

Regulus

Regulus is the brightest star in the constellation Leo and one of the brightest stars in the night sky, lying approximately 77.5 light years from Earth. Regulus is a multiple star system composed of four stars which are organized into two pairs...

, landed in Africa and after suffering some initial defeats the Carthaginian forces eventually repelled the Roman invasion.

Shortly after the First Punic War, Carthage faced a major mercenary revolt

Mercenary War

The Mercenary War — also called the Libyan War and the Truceless War by Polybius — was an uprising of mercenary armies formerly employed by Carthage, backed by Libyan settlements revolting against Carthaginian control....

which changed the internal political landscape of Carthage (bringing the Barcid

Barcid

The Barcid family was a notable family in the ancient city of Carthage; many of its members were fierce enemies of the Roman Republic. "Barcid" is an adjectival form coined by historians ; the actual byname was Barca or Barcas, which means lightning...

family to prominence), and affected Carthage's international standing, as Rome used the events of the war to base a claim by which it seized Sardinia

Sardinia

Sardinia is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea . It is an autonomous region of Italy, and the nearest land masses are the French island of Corsica, the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Tunisia and the Spanish Balearic Islands.The name Sardinia is from the pre-Roman noun *sard[],...

and Corsica

Corsica

Corsica is an island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is located west of Italy, southeast of the French mainland, and north of the island of Sardinia....

.

The Second Punic War

Second Punic War

The Second Punic War, also referred to as The Hannibalic War and The War Against Hannibal, lasted from 218 to 201 BC and involved combatants in the western and eastern Mediterranean. This was the second major war between Carthage and the Roman Republic, with the participation of the Berbers on...

lasted from 218

218 BC

Year 218 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Scipio and Longus...

to 202 BC

202 BC

Year 202 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Geminus and Nero...

and involved combatants in the western and eastern Mediterranean, with the participation of the Berbers

Berber people

Berbers are the indigenous peoples of North Africa west of the Nile Valley. They are continuously distributed from the Atlantic to the Siwa oasis, in Egypt, and from the Mediterranean to the Niger River. Historically they spoke the Berber language or varieties of it, which together form a branch...

on Carthage's side. The war is marked by Hannibal's surprising overland journey and his costly crossing of the Alps, followed by his reinforcement by Gaulish allies and crushing victories over Roman armies in the battle of the Trebia

Battle of the Trebia

The Battle of the Trebia was the first major battle of the Second Punic War, fought between the Carthaginian forces of Hannibal and the Roman Republic in December of 218 BC, on or around the winter solstice...

and the giant ambush at Trasimene

Battle of Lake Trasimene

The Battle of Lake Trasimene was a Roman defeat in the Second Punic War between the Carthaginians under Hannibal and the Romans under the consul Gaius Flaminius...

. Against his skill on the battlefield the Romans deployed the Fabian strategy

Fabian strategy

The Fabian strategy is a military strategy where pitched battles and frontal assaults are avoided in favor of wearing down an opponent through a war of attrition and indirection. While avoiding decisive battles, the side employing this strategy harasses its enemy through skirmishes to cause...

. But because of the increasing unpopularity of this approach, the Romans resorted to a further major field battle. The result was the Roman defeat at Cannae

Battle of Cannae

The Battle of Cannae was a major battle of the Second Punic War, which took place on August 2, 216 BC near the town of Cannae in Apulia in southeast Italy. The army of Carthage under Hannibal decisively defeated a numerically superior army of the Roman Republic under command of the consuls Lucius...

.

In consequence many Roman allies went over to Carthage, prolonging the war in Italy for over a decade, during which more Roman armies were destroyed on the battlefield. Despite these setbacks, the Roman forces were more capable in siegecraft than the Carthaginians and recaptured all the major cities that had joined the enemy, as well as defeating a Carthaginian attempt to reinforce Hannibal at the battle of the Metaurus

Battle of the Metaurus

The Battle of the Metaurus was a pivotal battle in the Second Punic War between Rome and Carthage, fought in 207 BC near the Metauro River in present-day Italy. The battle gets a chapter in the classic The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World by Sir Edward Shepherd Creasy...

. In the meantime in Iberia, which served as the main source of manpower for the Carthaginian army, a second Roman expedition under Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Major

Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus , also known as Scipio Africanus and Scipio the Elder, was a general in the Second Punic War and statesman of the Roman Republic...

took New Carthage

Cartagena, Spain

Cartagena is a Spanish city and a major naval station located in the Region of Murcia, by the Mediterranean coast, south-eastern Spain. As of January 2011, it has a population of 218,210 inhabitants being the Region’s second largest municipality and the country’s 6th non-Province capital...

by assault and ended Carthaginian rule over Iberia in the battle of Ilipa

Battle of Ilipa

The Battle of Ilipa in 206 BC was considered Scipio Africanus’s most brilliant victory in his military career during the Second Punic War. Though it may not seem to be as original as Hannibal’s tactic at Cannae, Scipio’s pre-battle maneuver and his Reverse Cannae formation was still a culmination...

. The final showdown was the battle of Zama

Battle of Zama

The Battle of Zama, fought around October 19, 202 BC, marked the final and decisive end of the Second Punic War. A Roman army led by Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus defeated a Carthaginian force led by the legendary commander Hannibal...

in Africa between Scipio Africanus and Hannibal, resulting in the latter's defeat and the imposition of harsh peace conditions on Carthage, which ceased to be a major power and became a Roman client-state.

The Third Punic War

Third Punic War

The Third Punic War was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between the former Phoenician colony of Carthage, and the Roman Republic...

(149 BC

149 BC

Year 149 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Censorinus and Manilius...

to 146 BC

146 BC

Year 146 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Lentulus and Achaicus...

) was the third and last of the Punic Wars. The war was a much smaller engagement than the two previous Punic Wars and primarily consisted of a single main action, the Battle of Carthage

Battle of Carthage (c.149 BC)

The Battle of Carthage was the major act of the Third Punic War between the Phoenician city of Carthage in Africa and the Roman Republic...

, but resulted in the complete destruction of the city of Carthage, the annexation of all remaining Carthaginian territory by Rome, and the death or enslavement of the entire Carthaginian population. The Third Punic War ended Carthage's independent existence.

Language

Carthaginians spoke PunicPunic language

The Punic language or Carthagian language is an extinct Semitic language formerly spoken in the Mediterranean region of North Africa and several Mediterranean islands, by people of the Punic culture.- Description :...

, a variety of Phoenician which was a Semitic

Semitic

In linguistics and ethnology, Semitic was first used to refer to a language family of largely Middle Eastern origin, now called the Semitic languages...

language originating in the Carthaginians' original homeland of Phoenicia

Phoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

(modern Lebanon).

Economy

The empire of Carthage depended heavily on its trade with Tartessos

Tartessos