Beefsteak Club

Encyclopedia

British Whig Party

The Whigs were a party in the Parliament of England, Parliament of Great Britain, and Parliament of the United Kingdom, who contested power with the rival Tories from the 1680s to the 1850s. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute rule...

concepts of liberty and prosperity.

The first beefsteak club was founded about 1705 in London by the actor Richard Estcourt

Richard Estcourt

Richard Estcourt was an English actor, who began by playing comedy parts in Dublin.His first London appearance was in 1704 as Dominick, in Dryden's Spanish Friar, and he continued to take important parts at Drury Lane, being the original Pounce in Steele's Tender Husband , Sergeant Kite in...

and others in the arts and politics. This club flourished for less than a decade. The Sublime Society of Beef Steaks was established in 1735 by another performer, John Rich

John Rich (producer)

John Rich was an important director and theatre manager in 18th century London. He opened the New Theatre at Lincoln's Inn Fields and then the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden and began putting on ever more lavish productions...

, at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, where he was then manager, and George Lambert

George Lambert (English painter)

George Lambert was an English landscape artist and theatre scene painter. He has been described as the Father of English Landscape Oil Painting.-Life and work:...

, his scenic artist, with two dozen members of the theatre and arts community (Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

joined in 1780). The society became much celebrated, and new members included royalty, statesmen and great soldiers: in 1785, the Prince of Wales

George IV of the United Kingdom

George IV was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and also of Hanover from the death of his father, George III, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later...

joined. At the weekly meetings, the members wore a blue coat and buff waistcoat with brass buttons bearing a gridiron motif and the words "Beef and liberty". The steaks and baked potatoes were accompanied by port

Port wine

Port wine is a Portuguese fortified wine produced exclusively in the Douro Valley in the northern provinces of Portugal. It is typically a sweet, red wine, often served as a dessert wine, and comes in dry, semi-dry, and white varieties...

or porter

Porter (beer)

Porter is a dark-coloured style of beer. The history and development of stout and porter are intertwined. The name was first used in the 18th century from its popularity with the street and river porters of London. It is generally brewed with dark malts...

. After dinner, the evening was given up to noisy revelry. The club met almost continuously until 1867. Sir Henry Irving

Henry Irving

Sir Henry Irving , born John Henry Brodribb, was an English stage actor in the Victorian era, known as an actor-manager because he took complete responsibility for season after season at the Lyceum Theatre, establishing himself and his company as...

continued its tradition in the late nineteenth century. A Sublime Society was established in 1966 which holds many of the original society's relics in safe keeping, includes lineal descendants from the nineteenth century membership and adheres closely to its early rules and customs.

Other "Beefsteak Clubs" included one in Dublin from 1749, for performers and politicians, and several in London and elsewhere. Many used the gridiron as their symbol, and some are even named after it, including the Gridiron Club

Gridiron Club

The Gridiron Club and Foundation, founded in 1885, is the oldest and one of the most prestigious journalistic organizations in Washington, D.C. Its 65 active members represent major newspapers, news services, news magazines and broadcast networks. Membership is by invitation only and has...

of Washington, D.C. In 1876, a Beefsteak Club was formed that became an essential after-theatre club for the bohemian theatre set, including W. S. Gilbert

W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his fourteen comic operas produced in collaboration with the composer Sir Arthur Sullivan, of which the most famous include H.M.S...

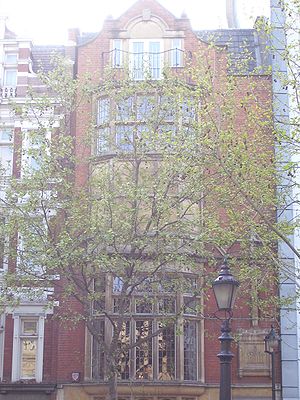

, and still meets today in Irving Street (pictured at right).

Early beefsteak clubs

The first known beefsteak club (the Beef-Stake Club, Beef-Steak Clubb or Honourable Beef-Steak Club) seems to have been that founded in about 1705 in London. It was started by some seceders from the Whiggish Kit-Cat ClubKit-Cat Club

The Kit-Cat Club was an early 18th century English club in London with strong political and literary associations, committed to the furtherance of Whig objectives, meeting at the Trumpet tavern in London, and at Water Oakley in the Berkshire countryside.The first meetings were held at a tavern in...

, "desirous of proving substantial beef was as prolific a food for an English wit as pies and custards for a Kit-cat beau." The actor Richard Estcourt

Richard Estcourt

Richard Estcourt was an English actor, who began by playing comedy parts in Dublin.His first London appearance was in 1704 as Dominick, in Dryden's Spanish Friar, and he continued to take important parts at Drury Lane, being the original Pounce in Steele's Tender Husband , Sergeant Kite in...

was its "providore" or president and its most popular member. William Chetwood in A General History of the Stage is the much quoted source that the "chief Wits and great men of the nation" were members of this club. This was the first beefsteak club known to have used a gridiron

Gridiron (cooking)

A gridiron is a metal grate with parallel bars typically used for grilling meat, fish, vegetables, or combinations of such foods. It may also be two such grids, hinged to fold together, to securely hold food while grilling over an open flame.-Development:...

as its badge. In 1708, Dr. William King dedicated his poem "Art of Cookery" to "the Honourable Beef Steak Club". His poem includes the couplet:

He that of Honour, Wit and Mirth partakes,

May be a fit Companion o'er Beef-steaks.

The club originally met at the Imperial Phiz public house in Old Jewry

Old Jewry

Old Jewry is the name of a street in the City of London, in Coleman Street Ward, linking Gresham Street with The Poultry.William the Conqueror encouraged Jews to come to England soon after the Norman Conquest; some settled in cities throughout his new domain, including in London. According to Rev....

in the City of London

City of London

The City of London is a small area within Greater London, England. It is the historic core of London around which the modern conurbation grew and has held city status since time immemorial. The City’s boundaries have remained almost unchanged since the Middle Ages, and it is now only a tiny part of...

, but finding that venue not private enough, it ceased to meet there, and by 1709 it was not known "whether they have healed the breach and returned into the Kit-Cat community [or] … remove from place to place to prevent discovery." Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison was an English essayist, poet, playwright and politician. He was a man of letters, eldest son of Lancelot Addison...

referred to the club in The Spectator

The Spectator (1711)

The Spectator was a daily publication of 1711–12, founded by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in England after they met at Charterhouse School. Eustace Budgell, a cousin of Addison's, also contributed to the publication. Each 'paper', or 'number', was approximately 2,500 words long, and the...

in 1711 as still functioning. The historian Colin J. Horne suggests that the club may have come to an end with the death of Estcourt in 1712. There was also a "Rump-Steak or Liberty Club" (also called "The Patriots Club") of London, which was in existence in 1733–34, whose members were "eager in opposition to Sir Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, KG, KB, PC , known before 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British statesman who is generally regarded as having been the first Prime Minister of Great Britain....

".

Sublime Society of Beef Steaks

The Sublime Society of Beef Steaks was established in 1735 by John RichJohn Rich (producer)

John Rich was an important director and theatre manager in 18th century London. He opened the New Theatre at Lincoln's Inn Fields and then the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden and began putting on ever more lavish productions...

at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, of which he was then manager. One version of its origin has it that the Earl of Peterborough

Charles Mordaunt, 4th Earl of Peterborough

Charles Mordaunt, 4th Earl of Peterborough, 2nd Earl of Monmouth was a British peer and Member of Parliament, styled Viscount Mordaunt from 1710 to 1735....

, supping one night with Rich in his private room, was so delighted with the steak Rich grilled him that he suggested a repetition of the meal the next week. Another version is that George Lambert

George Lambert (English painter)

George Lambert was an English landscape artist and theatre scene painter. He has been described as the Father of English Landscape Oil Painting.-Life and work:...

, the scene-painter at the theatre, was often too busy to leave the theatre and "contented himself with a beefsteak broiled upon the fire in the painting-room." His visitors so enjoyed sharing this dish that they set up the Sublime Society. William and Robert Chambers, writing in 1869, favour the second version, noting that Peterborough was not one of the original members. A third version, favoured by the historian of the society, Walter Arnold, is that the society was formed out of the regular dinners shared at the theatre by Rich and Lambert, consisting of hot steak dressed by Rich, accompanied by "a bottle of old port

Port wine

Port wine is a Portuguese fortified wine produced exclusively in the Douro Valley in the northern provinces of Portugal. It is typically a sweet, red wine, often served as a dessert wine, and comes in dry, semi-dry, and white varieties...

from the tavern hard by." Whatever the details of its genesis, Rich and Lambert are listed as the first two of the society's twenty-four founding members. Women were not admitted. From the outset, the society strove to avoid the term "club", but the shorter "Beefsteak Club" was soon used by many as an informal alternative.

The early core of the society was made up of actors, artists, writers and musicians, among them William Hogarth

William Hogarth

William Hogarth was an English painter, printmaker, pictorial satirist, social critic and editorial cartoonist who has been credited with pioneering western sequential art. His work ranged from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like series of pictures called "modern moral subjects"...

(a founder-member), David Garrick

David Garrick

David Garrick was an English actor, playwright, theatre manager and producer who influenced nearly all aspects of theatrical practice throughout the 18th century and was a pupil and friend of Dr Samuel Johnson...

(possibly), John Wilkes

John Wilkes

John Wilkes was an English radical, journalist and politician.He was first elected Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he fought for the right of voters—rather than the House of Commons—to determine their representatives...

(elected 1754), Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

(1780), and John Philip Kemble

John Philip Kemble

John Philip Kemble was an English actor. He was born into a theatrical family as the eldest son of Roger Kemble, actor-manager of a touring troupe. His elder sister Sarah Siddons achieved fame with him on the stage of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane...

(1805). The society soon became much celebrated and these men of the arts were joined by noblemen, royalty, statesmen and great soldiers: in 1785, the Prince of Wales

George IV of the United Kingdom

George IV was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and also of Hanover from the death of his father, George III, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later...

joined, and later his brothers the Dukes of Clarence

William IV of the United Kingdom

William IV was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death...

and Sussex

Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex

The Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex , was the sixth son of George III of the United Kingdom and his consort, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. He was the only surviving son of George III who did not pursue an army or naval career.- Early life :His Royal Highness The Prince Augustus...

became members.

Meetings were held every Saturday between November and June. All members were required to wear the society's uniform – a blue coat and buff waistcoat with brass buttons. The buttons bore a gridiron motif and the words "Beef and liberty". The steaks were served on hot pewter plates, with onions and baked potatoes, and were accompanied by port or porter

Porter (beer)

Porter is a dark-coloured style of beer. The history and development of stout and porter are intertwined. The name was first used in the 18th century from its popularity with the street and river porters of London. It is generally brewed with dark malts...

. The only second course offered was toasted cheese. After dinner, the tablecloth was removed, the cook collected the money, and the rest of the evening was given up to noisy revelry.

The society met at Covent Garden until the fire of 1808, when it moved first to the Bedford Coffee House, and thence the following year to the Old Lyceum Theatre. On the burning of the Lyceum in 1830, "The Steaks" met again in the Bedford Coffee House until 1838, when the Lyceum reopened, and a large room there was allotted to the club. These meetings were held till the society ceased to exist in 1867. Its decline in its last twenty or so years was due to changing fashion: many of its members were no longer free on Saturdays, being either engaged in events in London's social season or else away from London at weekends, something much encouraged by the opening of railways. The customary time for dinner had also changed. The society moved its dinner time from 4.00 p.m. in 1808, to 6.00 p.m. in 1833 and to 7.00 p.m. in 1861, and finally to 8.00 p.m. in 1866, but the change inconvenienced the members who preferred the old timing and did not attract new members. Moreover, in Victorian

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

England, its Georgian

Georgian era

The Georgian era is a period of British history which takes its name from, and is normally defined as spanning the reigns of, the first four Hanoverian kings of Great Britain : George I, George II, George III and George IV...

heartiness and ritual, and old-fashioned uniform, no longer appealed. By 1867 the society had only eighteen members, and the average attendance at dinners had dwindled to two. The club was wound up in 1867, and its assets were auctioned at Christie's

Christie's

Christie's is an art business and a fine arts auction house.- History :The official company literature states that founder James Christie conducted the first sale in London, England, on 5 December 1766, and the earliest auction catalogue the company retains is from December 1766...

, raising a little over £600.

Other 18th and 19th century clubs

Thomas Sheridan founded a "Beefsteak Club" in Dublin at the Theatre RoyalTheatre Royal, Dublin

At one stage in the history of the theatre in Britain and Ireland, the designation Theatre Royal or Royal Theatre was an indication that the theatre was granted a Royal Patent without which theatrical performances were illegal...

in 1749, and of this Peg Woffington

Margaret Woffington

Margaret "Peg" Woffington was a well-known Irish actress in Georgian London.- Early life :Woffington was born of humble origins in Dublin. Her father is thought to have been a bricklayer, and after his death, the family became impoverished...

was president. According to William and Robert Chambers, writing in 1869, "it could hardly be called a club at all, seeing all expenses were defrayed by Manager Sheridan, who likewise invited the guests – generally peers and members of parliament. … Such weekly meetings were common to all theatres, it being a custom for the principal performers to dine together every Saturday and invite 'authors and other geniuses' to partake of their hospitality."

The Liberty Beef Steak Club sought to show solidarity with the radical John Wilkes

John Wilkes

John Wilkes was an English radical, journalist and politician.He was first elected Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he fought for the right of voters—rather than the House of Commons—to determine their representatives...

MP and met at Appleby's Tavern in Parliament Street, London for an unknown duration after Wilkes's return from exile in France in 1768. John Timbs wrote in 1872 of a "Beef-Steak Club" which met at the Bell Tavern, Church Row, Houndsditch

Houndsditch

Houndsditch is a street in the City of London that connects Bishopsgate in the north west to Aldgate in the south east. The modern street runs through a part of the Portsoken Ward and Bishopsgate Ward Without...

, and was instituted by "Mr Beard, Mr Dunstall, Mr Woodward, Stoppalear, Bencroft, Gifford etc". It is not clear if the Ivy Lane Club

Ivy Lane Club

The Ivy Lane Club was a literary and social club founded by Samuel Johnson in the 1740s. The club met in the King's Head, a beefsteak house in Ivy Lane, Paternoster Row, near St Paul's Cathedral, London....

, of which Dr Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

was a member, was a "Beef-Steak Club", but it met at a famous beef-steak house.

Many beefsteak clubs of the 18th and 19th centuries have used the traditional grilling gridiron as their symbol and some are even named after it: the Gridiron Club of Oxford

Oxford

The city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through...

was founded in 1884, and the Gridiron Club

Gridiron Club

The Gridiron Club and Foundation, founded in 1885, is the oldest and one of the most prestigious journalistic organizations in Washington, D.C. Its 65 active members represent major newspapers, news services, news magazines and broadcast networks. Membership is by invitation only and has...

of Washington D.C. was founded the following year. These two clubs also still exist.

Successors to the Sublime Society

Irving's dinners and the present Sublime SocietySince the closure of the original Sublime Society in 1867, three separate efforts have been made to revive it in various forms. Sir Henry Irving, as proprietor of the Lyceum Theatre, had possession within his theatre of the society's last premises. From about 1878 until his death in 1905, he hosted dinners in the society's dining room. A biographer of Irving wrote, "He wanted the Lyceum to have the same educational and intellectual force that Phelps

Samuel Phelps

Samuel Phelps was an English actor and theatre manager...

' theatre had enjoyed in lslington." A contemporary newspaper reported, "Almost as soon as Mr. Irving undertook the management of the Lyceum he restored this venerable sanctuary to something like its former appearance, and very often now it is the scene of the informal and bright little supper parties which he delights to bring about him. … If the nocturnal gatherings in the room were not of a private character we might say a good deal about them, especially as the guests frequently include men whose names are great."

The Sublime Society of Beef Steaks was re-formed in 1966 and has met continually since then. Several nineteenth century members have lineal descendants among today's membership, who wear the original blue and buff uniform (of a Regency character) and buttons and adhere to the 1735 constitution whenever practicable. This revival started to meet at the Irish Club, Eaton Square, in 1966, then at the Beefsteak Club, Irving Street, and today meets in a private room at the Boisdale Club and Restaurant in Belgravia

Belgravia

Belgravia is a district of central London in the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Noted for its immensely expensive residential properties, it is one of the wealthiest districts in the world...

/Victoria

Victoria, London

Victoria is a commercial and residential area of inner city London, lying wholly within the City of Westminster, and named after Queen Victoria....

and, annually, at White's Club in St James’s, where it is able to dine at the early society's nineteenth century table and where it also keeps the early society's original "President’s Chair", which Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom

Elizabeth II is the constitutional monarch of 16 sovereign states known as the Commonwealth realms: the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Jamaica, Barbados, the Bahamas, Grenada, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Belize,...

gave to the current society in 1969. Although other of the society's relics (such as the original Grid Iron, Sword of State, Halberts and early members' chairs, rings, glasses, documents, etc) have passed down to members of the current society from ancestors in the original society, the current society "leaves such items in safety, keeping less fragile replicas and proxy items for its normal meetings in Central London". Other early customs of the original society, such as the singing and composition of songs, are also encouraged by the current society.

Beefsteak Club, Irving Street

The Beefsteak Club that today has premises at 9 Irving Street, London, was established in 1876. When it was founded as a successor to the Sublime Society, its members hoped to rent the society's dining room at the Lyceum. As that room was not available, the club held its first meeting, on 11 March 1876, in rooms above the Folly Theatre

Folly Theatre

The Folly Theatre was a London theatre of the late 19th century, in William IV Street, near Charing Cross, in the City of Westminster. It was converted from the house of a religious order, and became a small theatre, with a capacity of 900 seated and standing. The theatre specialised in presenting...

in King William IV Street. Two features of the club were, and are, that all members and guests sit together at a single long table, and that by tradition the club steward and the waiters are all addressed as "Charles".

The Beefsteak became an essential after-theatre club for such men as the dramatists F. C. Burnand and W. S. Gilbert

W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his fourteen comic operas produced in collaboration with the composer Sir Arthur Sullivan, of which the most famous include H.M.S...

, performers Corney Grain, J. L. Toole

John Lawrence Toole

John Lawrence Toole was an English comic actor and theatrical producer. He was famous for his roles in farce and in serio-comic melodramas in a career that spanned more than four decades...

, John Hare

John Hare (actor)

Sir John Hare , born John Fairs, was an English actor and manager of the Garrick Theatre in London from 1889 to 1895.-Biography:Hare was born in Giggleswick in Yorkshire and was educated at Giggleswick school...

, Henry Irving and W. H. Kendal, and theatre managers and writers Henry Labouchère

Henry Labouchere

Henry Du Pré Labouchère was an English politician, writer, publisher and theatre owner in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. He married the actress Henrietta Hodson....

and Bram Stoker

Bram Stoker

Abraham "Bram" Stoker was an Irish novelist and short story writer, best known today for his 1897 Gothic novel Dracula...

, and their peers. Restaurant critic Nathaniel Newnham-Davis

Nathaniel Newnham-Davis

Nathaniel Newnham-Davis , generally known as Lieutenant Colonel Newnham-Davis, was a food writer and gourmet. After a military career, he took up journalism, and was chiefly known for his restaurant reports from London establishments of the last decade of the 19th century and the first decade of...

was also a member around the turn of the 20th century. The club moved to Green Street, in Mayfair

Mayfair

Mayfair is an area of central London, within the City of Westminster.-History:Mayfair is named after the annual fortnight-long May Fair that took place on the site that is Shepherd Market today...

, and, in 1896, to its present address. There were 250 members, some of whom occasionally performed amateur plays for their own amusement and to raise funds for charities. For example, in 1878, they performed The Forty Thieves

The Forty Thieves

The Forty Thieves is a "Pantomime Burlesque" written by Robert Reece, W. S. Gilbert, F. C. Burnand and Henry J. Byron, created in 1878 as an amateur production for the Beefsteak Club of London. The Beefsteak Club still meets in Irving Street, London. It was founded by actor John Lawrence Toole...

, written by members Robert Reece

Robert Reece

Robert Reece was a British comic playwright and librettist active in the Victorian era. He wrote many successful musical burlesques, comic operas, farces and adaptations from the French, including the English-language adaptation of the operetta Les cloches de Corneville, which became the...

, Gilbert, Burnand, and Henry J. Byron. In 1879 there was a much-reported court case following a fracas on the doorstep of the club between Labouchère and Edward Levy-Lawson

Edward Levy-Lawson, 1st Baron Burnham

Edward Levy-Lawson, 1st Baron Burnham KCVO , known as Sir Edward Levy-Lawson, 1st Baronet, from 1892 to 1903, was a British newspaper proprietor....

, proprietor of The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph is a daily morning broadsheet newspaper distributed throughout the United Kingdom and internationally. The newspaper was founded by Arthur B...

. The committee of the club expelled Labouchère, who successfully sought a court ruling that they had no right to do so.

The club has had at least one prime minister in its ranks: in 1957 the members gave a dinner to Harold Macmillan

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, OM, PC was Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 January 1957 to 18 October 1963....

"to mark the occasion of his becoming Prime Minister, and in recognition of his services to the club as their senior trustee." Who's Who

Who's Who (UK)

Who's Who is an annual British publication of biographies which vary in length of about 30,000 living notable Britons.-History:...

lists 791 men, living and dead, who have been members of the present Beefsteak Club. As well as men of the theatre, they include politicians such as R. A. Butler, Roy Jenkins

Roy Jenkins

Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead OM, PC was a British politician.The son of a Welsh coal miner who later became a union official and Labour MP, Roy Jenkins served with distinction in World War II. Elected to Parliament as a Labour member in 1948, he served in several major posts in...

and Robert Gascoyne-Cecil

Marquess of Salisbury

Marquess of Salisbury is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1789 for the 7th Earl of Salisbury. Most of the holders of the title have been prominent in British political life over the last two centuries, particularly the 3rd Marquess, who served three times as Prime Minister...

, poets including John Betjeman

John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman, CBE was an English poet, writer and broadcaster who described himself in Who's Who as a "poet and hack".He was a founding member of the Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture...

, musicians including Edward Elgar

Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet OM, GCVO was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestral works including the Enigma Variations, the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, concertos...

and Malcolm Sargent

Malcolm Sargent

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works...

, filmmakers and broadcasters such as Richard Attenborough

Richard Attenborough

Richard Samuel Attenborough, Baron Attenborough , CBE is a British actor, director, producer and entrepreneur. As director and producer he won two Academy Awards for the 1982 film Gandhi...

, Peter Bazalgette

Peter Bazalgette

Peter "Baz" Bazalgette is a British media expert who helped create the independent TV production sector in the UK and went on to be the leading creative figure in the global TV company Endemol....

, Richard Dimbleby

Richard Dimbleby

Richard Dimbleby CBE was an English journalist and broadcaster widely acknowledged as one of the greatest figures in British broadcasting history.-Early life:...

and Barry Humphries

Barry Humphries

John Barry Humphries, AO, CBE is an Australian comedian, satirist, dadaist, artist, author and character actor, best known for his on-stage and television alter egos Dame Edna Everage, a Melbourne housewife and "gigastar", and Sir Les Patterson, Australia's foul-mouthed cultural attaché to the...

, and philosophers including A. J. Ayer and A. C. Grayling

A. C. Grayling

Anthony Clifford Grayling is a British philosopher. In 2011 he founded and became the first Master of New College of the Humanities, a private undergraduate college in London. Until June 2011, he was Professor of Philosophy at Birkbeck, University of London, where he taught from 1991...

, as well as figures from other spheres such as Robert Baden-Powell, Osbert Lancaster

Osbert Lancaster

Sir Osbert Lancaster, CBE was an English cartoonist, author, art critic and stage designer, best known to the public at large for his cartoons published in the Daily Express.-Biography:Lancaster was born in London, England...

and Edwin Lutyens

Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens, OM, KCIE, PRA, FRIBA was a British architect who is known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era...

.

Further reading

- Thompson, Charles Willis, "Thirty Years of Gridiron Club Dinners", The New York TimesThe New York TimesThe New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

, 24 October 1915, p. SM16