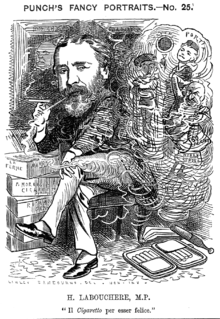

Henry Labouchere

Encyclopedia

- "Henry Labouchere" redirects here. For his uncle, see Henry Labouchere, 1st Baron TauntonHenry Labouchere, 1st Baron TauntonHenry Labouchere, 1st Baron Taunton PC was a prominent British Whig and Liberal Party politician of the mid-19th century.-Background and education:...

Henry Du Pré Labouchère (9 November 1831 – 15 January 1912) was an English politician, writer, publisher and theatre owner in the Victorian

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

and Edwardian eras. He married the actress Henrietta Hodson

Henrietta Hodson

Henrietta Hodson was an English actress and theatre manager best known for her portrayal of comedy roles in the Victorian era. She had a long affair with the journalist-turned-politician Henry Labouchère, later marrying him....

.

Labouchère, who inherited a large fortune, engaged in a number of occupations. He was a junior member of the British diplomatic service, a Member of Parliament in the 1860s and again from 1880 to 1906, and edited and funded his own magazine, Truth

Truth (British periodical)

Truth was a British periodical publication founded by the diplomat and Liberal politician Henry Labouchère after he left a virtual rival publication The World. Truth was noted for its exposures of many kinds of frauds, and was at the centre of several civil lawsuits...

. He is remembered for the Labouchere Amendment

Labouchere Amendment

The Labouchere Amendment, also known as Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 made gross indecency a crime in the United Kingdom. The amendment gave no definition of "gross indecency," as Victorian morality demurred from precise descriptions of activity held to be immoral...

to British law, which for the first time made all male homosexual activity a crime.

Unable to secure the senior positions to which he thought himself suitable, Labouchère left Britain and retired to Italy.

Life and career

Huguenot

The Huguenots were members of the Protestant Reformed Church of France during the 16th and 17th centuries. Since the 17th century, people who formerly would have been called Huguenots have instead simply been called French Protestants, a title suggested by their German co-religionists, the...

extraction. His father, John Peter Labouchère (d. 1863), a banker, was the second son of French parents who had settled in Britain in 1816. His mother, Mary Louisa née Du Pré (1799–1863) was from an English family. Labouchère was the eldest of their three sons and six daughters. He was the nephew of the Whig

British Whig Party

The Whigs were a party in the Parliament of England, Parliament of Great Britain, and Parliament of the United Kingdom, who contested power with the rival Tories from the 1680s to the 1850s. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute rule...

politician Henry Labouchere, 1st Baron Taunton

Henry Labouchere, 1st Baron Taunton

Henry Labouchere, 1st Baron Taunton PC was a prominent British Whig and Liberal Party politician of the mid-19th century.-Background and education:...

, who, despite disapproving of his rebellious nephew, helped the young man's early career and left him a sizeable inheritance when he died leaving no male heir.

Early career

Labouchère was educated at EtonEton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

and Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Trinity has more members than any other college in Cambridge or Oxford, with around 700 undergraduates, 430 graduates, and over 170 Fellows...

, where, he later said, he "diligently attended the racecourse at Newmarket," losing £6,000 in gambling in two years. He was accused of cheating in an examination and his degree was withheld. He left Cambridge and went travelling in Europe, South America and the United States. While he was in the U.S., Labouchère (without his prior knowledge) was found a place in the British diplomatic service by his family. Between 1854 and 1864, Labouchère served as a minor diplomat in Washington, Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

, Stockholm

Stockholm

Stockholm is the capital and the largest city of Sweden and constitutes the most populated urban area in Scandinavia. Stockholm is the most populous city in Sweden, with a population of 851,155 in the municipality , 1.37 million in the urban area , and around 2.1 million in the metropolitan area...

, Frankfurt

Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main , commonly known simply as Frankfurt, is the largest city in the German state of Hesse and the fifth-largest city in Germany, with a 2010 population of 688,249. The urban area had an estimated population of 2,300,000 in 2010...

, St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

, Dresden

Dresden

Dresden is the capital city of the Free State of Saxony in Germany. It is situated in a valley on the River Elbe, near the Czech border. The Dresden conurbation is part of the Saxon Triangle metropolitan area....

, and Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

. He was, however, not known for his diplomatic demeanour, and acted impudently on occasion. He went too far when he wrote to the Foreign Secretary to refuse a posting offered to him, "I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of your Lordship's despatch, informing me of my promotion as Second Secretary to Her Majesty's Legation at Buenos Ayres. I beg to state that, if residing at Baden-Baden I can fulfil those duties, I shall be pleased to accept the appointment." He was politely told that there was no further use for his services.

The year after his dismissal, Labouchère was elected at the 1865 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1865

The 1865 United Kingdom general election saw the Liberals, led by Lord Palmerston, increase their large majority over the Earl of Derby's Conservatives to more than 80. The Whig Party changed its name to the Liberal Party between the previous election and this one.Palmerston died later in the same...

as a Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

(MP) for Windsor

Windsor (UK Parliament constituency)

Windsor is a county constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. In its modern form, it elects one Member of Parliament by the first-past-the-post system of election.-Boundaries:...

, as a Liberal

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

. However, that election was overturned on petition on 26 April 1866, and in April 1867 he was elected at a by-election as an MP for Middlesex

Middlesex (UK Parliament constituency)

Middlesex is a former United Kingdom Parliamentary constituency. It was a constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of England then of the Parliament of Great Britain from 1707 to 1800 and of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1885....

. At the 1868 election

United Kingdom general election, 1868

The 1868 United Kingdom general election was the first after passage of the Reform Act 1867, which enfranchised many male householders, thus greatly increasing the number of men who could vote in elections in the United Kingdom...

he narrowly lost his seat, winning only 90 votes less than his Conservative opponent's total of 6,487. Labouchère did not return to the House of Commons for 12 years.

In 1867, Labouchère and his partners engaged the architect C. J. Phipps and the artists Albert Moore

Albert Joseph Moore

Albert Joseph Moore was an English painter, known for his depictions of langorous female figures set against the luxury and decadence of the classical world....

and Telbin to remodel the large St. Martins Hall to create Queen's Theatre, Long Acre

Queen's Theatre, Long Acre

The Queen's Theatre was established in 1867, as a theatre on the site of St Martin's Hall, a large concert room that opened in 1850. It stood on the corner of Long Acre and Endell Street, with entrances in Wilson Street and Long Acre...

. A new company of players was formed, including Charles Wyndham

Charles Wyndham

Sir Charles Wyndham was an English actor-manager, born as Charles Culverwell in Liverpool, the son of a doctor. He was educated abroad, at King's College London and at the College of Surgeons and the Peter Street Anatomical School, Dublin...

, Henry Irving

Henry Irving

Sir Henry Irving , born John Henry Brodribb, was an English stage actor in the Victorian era, known as an actor-manager because he took complete responsibility for season after season at the Lyceum Theatre, establishing himself and his company as...

, J. L. Toole

John Lawrence Toole

John Lawrence Toole was an English comic actor and theatrical producer. He was famous for his roles in farce and in serio-comic melodramas in a career that spanned more than four decades...

, Ellen Terry

Ellen Terry

Dame Ellen Terry, GBE was an English stage actress who became the leading Shakespearean actress in Britain. Among the members of her famous family is her great nephew, John Gielgud....

, and Henrietta Hodson

Henrietta Hodson

Henrietta Hodson was an English actress and theatre manager best known for her portrayal of comedy roles in the Victorian era. She had a long affair with the journalist-turned-politician Henry Labouchère, later marrying him....

. By 1868, Hodson and Labouchère were living together out of wedlock, as they could not marry until her first husband died in 1887. Labouchère bought out his partners and used the theatre to promote Hodson's talents; the theatre made a loss, Hodson retired, and the theatre closed in 1879. The couple finally married in 1887. Their one child together, Mary Dorothea (Dora) Labouchère, had been born in 1884 and later was a daughter-in-law of Emanuele Ruspoli, 1st Prince of Poggio Suasa

Emanuele Ruspoli, 1st Prince of Poggio Suasa

Emanuele Francesco Maria dei Principi Ruspoli was the 1st Principe di Poggio Suasa, son of Bartolomeo dei Principi Ruspoli and wife Carolina Ratti and paternal grandson of Francesco Ruspoli, 3rd Prince of Cerveteri and second wife Countess Maria Leopoldina von Khevenhüller-Metsch and ancestor of...

. Hodson's cousin was the theatre producer George Musgrove

George Musgrove

George Musgrove was an English-born Australian theatre producer.-Early life:Musgrove was born at Surbiton, England, the son of Thomas John Watson Musgrove, an accountant, and his wife, Fanny Hodson, an actress and sister of Georgiana Rosa Hodson who married William Saurin Lyster...

.

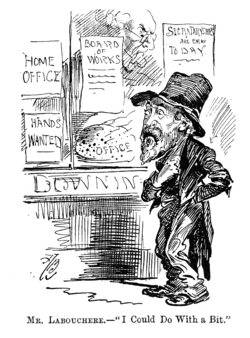

Journalist and writer; 1879 altercation

Truth (British periodical)

Truth was a British periodical publication founded by the diplomat and Liberal politician Henry Labouchère after he left a virtual rival publication The World. Truth was noted for its exposures of many kinds of frauds, and was at the centre of several civil lawsuits...

(started in 1877), which was often sued for libel. With his inherited wealth, he could afford to defend such suits. Labouchère's claims to being impartial were ridiculed by his critics, including W. S. Gilbert

W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his fourteen comic operas produced in collaboration with the composer Sir Arthur Sullivan, of which the most famous include H.M.S...

(who had been an object of Labouchère's theatrical criticism) in Gilbert's comic opera

Comic opera

Comic opera denotes a sung dramatic work of a light or comic nature, usually with a happy ending.Forms of comic opera first developed in late 17th-century Italy. By the 1730s, a new operatic genre, opera buffa, emerged as an alternative to opera seria...

His Excellency

His Excellency (opera)

His Excellency is a two-act comic opera with a libretto by W. S. Gilbert and music by F. Osmond Carr. The piece concerns a practical-joking governor whose pranks threaten to make everyone miserable, until the Prince Regent kindly foils the governor's plans...

(see illustration at right). In 1877, Gilbert had engaged in a public feud with Labouchère's lover, Henrietta Hodson.

Labouchère was a vehement opponent of feminism; he campaigned in Truth against the suffrage movement, ridiculing and belittling women who sought the right to vote. He was also a virulent anti-semite, opposed to Jewish participation in British life, using Truth to campaign against "Hebrew barons" and their supposedly excessive influence, "Jewish exclusivity" and "Jewish cowardice". One of the victims of his attacks was Edward Levy-Lawson

Edward Levy-Lawson, 1st Baron Burnham

Edward Levy-Lawson, 1st Baron Burnham KCVO , known as Sir Edward Levy-Lawson, 1st Baronet, from 1892 to 1903, was a British newspaper proprietor....

, proprietor of The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph is a daily morning broadsheet newspaper distributed throughout the United Kingdom and internationally. The newspaper was founded by Arthur B...

. In 1879 there was a much-reported court case following a fracas on the doorstep of the Beefsteak Club

Beefsteak Club

Beefsteak Club is the name, nickname and historically common misnomer applied by sources to several 18th and 19th century male dining clubs that celebrated the beefsteak as a symbol of patriotic and often Whig concepts of liberty and prosperity....

between Labouchère and Levy-Lawson. The committee of the club expelled Labouchère, who successfully sought a court ruling that they had no right to do so.

Return to Parliament

Labouchère returned to Parliament in the 1880 electionUnited Kingdom general election, 1880

-Seats summary:-References:*F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987* British Electoral Facts 1832-1999, compiled and edited by Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher *...

, when he and Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh was a political activist and one of the most famous English atheists of the 19th century. He founded the National Secular Society in 1866.-Early life:...

, both Liberals, won the two seats for Northampton

Northampton (UK Parliament constituency)

Northampton was a parliamentary constituency centred on the town of Northampton which existed until 1974.It returned two Members of Parliament to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom until its representation was reduced to one member for the 1918 general election...

. (Bradlaugh's then-controversial atheism led Labouchère, a closet agnostic, to refer sardonically to himself as "the Christian member for Northampton".)

Homophobia

Homophobia is a term used to refer to a range of negative attitudes and feelings towards lesbian, gay and in some cases bisexual, transgender people and behavior, although these are usually covered under other terms such as biphobia and transphobia. Definitions refer to irrational fear, with the...

, drafted the Labouchere Amendment

Labouchere Amendment

The Labouchere Amendment, also known as Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 made gross indecency a crime in the United Kingdom. The amendment gave no definition of "gross indecency," as Victorian morality demurred from precise descriptions of activity held to be immoral...

, outlawing "gross indecency"; sodomy

Sodomy

Sodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

was already a crime, but Labouchère's Amendment now criminalised any sexual activity between men. Frank Harris

Frank Harris

Frank Harris was a Irish-born, naturalized-American author, editor, journalist and publisher, who was friendly with many well-known figures of his day...

, a contemporary, wrote that Labouchere proposed the amendment in order to make the law seem "ridiculous" and thus discredit it in its entirety; some historians agree, citing Labouchere's habitual obstructionism and other attempts to sink this bill by the same means, while others write that his role in the Cleveland Street scandal

Cleveland Street scandal

The Cleveland Street scandal occurred in 1889, when a homosexual male brothel in Cleveland Street, Fitzrovia, London, was discovered by police. At the time, sexual acts between men were illegal in Britain, and the brothel's clients faced possible prosecution and certain social ostracism if discovered...

and the context of the law in controlling male sexuality suggest a sincere attempt. Ten years later the Labouchere Amendment allowed for the prosecution of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s...

, who was given the maximum sentence of two years' imprisonment with hard labour.

During the 1880s, the Liberal Party faced a split between a Radical wing (led by Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain was an influential British politician and statesman. Unlike most major politicians of the time, he was a self-made businessman and had not attended Oxford or Cambridge University....

) and a Whig wing (led by the Marquess of Hartington

Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire

Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire KG, GCVO, PC, PC , styled Lord Cavendish of Keighley between 1834 and 1858 and Marquess of Hartington between 1858 and 1891, was a British statesman...

), with its party leader, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

straddling the middle. Labouchère was a firm and vocal Radical, who tried to create a governing coalition between the Radicals and the Irish Nationalists that would exclude or marginalize the Whigs. This plan was wrecked in 1886, when, after Gladstone came out for Home Rule

Home rule

Home rule is the power of a constituent part of a state to exercise such of the state's powers of governance within its own administrative area that have been devolved to it by the central government....

, a large contingent of both Radicals and Whigs chose to leave the Liberal Party to form a "Unionist" party allied with the Conservatives

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

.

Between 1886 and 1892, a Conservative government was in power, and Labouchère worked tirelessly to remove them from office. When the government was turned out in 1892, and Gladstone was called to form an administration, Labouchère expected to be rewarded with a cabinet post. Queen Victoria refused to allow Gladstone to offer Labouchère an office, however (he had insulted the Royal Family). This was the last time a British monarch vetoed a prime minister's appointment of a cabinet minister. Likewise, the new foreign secretary, Lord Rosebery, a personal enemy of Labouchère, declined to offer him the ambassadorship to Washington for which Labouchère had asked.

In 1897, Labouchère was accused in the press of share-rigging, using Truth to disparage companies, advising shareholders to dispose of their shares and, when the share prices fell as a result, buying them himself at a low price. When he failed to reply to the accusations, his reputation suffered accordingly. After being snubbed for a second time by the Liberal leadership after their victory in the 1906 election

United Kingdom general election, 1906

-Seats summary:-See also:*MPs elected in the United Kingdom general election, 1906*The Parliamentary Franchise in the United Kingdom 1885-1918-External links:***-References:*F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987**...

, Labouchère resigned his seat and retired to Florence. He died there seven years later, leaving a fortune of some two million pounds sterling to his daughter Dora, who was by then married to Carlo, Marchese di Rudini.

External links

- "The Brown Man's Burden" (1899), a parody by Labouchère of Rudyard Kipling's "The White Man's BurdenThe White Man's Burden"The White Man's Burden" is a poem by the English poet Rudyard Kipling. It was originally published in the popular magazine McClure's in 1899, with the subtitle The United States and the Philippine Islands...

"; published in Truth, a London journal