Matthew Brettingham

Encyclopedia

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

who rose from humble origins to supervise the construction of Holkham Hall

Holkham Hall

Holkham Hall is an eighteenth-century country house located adjacent to the village of Holkham, on the north coast of the English county of Norfolk...

, and eventually became one of the country's better-known architect

Architect

An architect is a person trained in the planning, design and oversight of the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to offer or render services in connection with the design and construction of a building, or group of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the...

s of his generation. Much of his principal work has since been demolished, particularly his work in London, where he revolutionised the design of the grand townhouse

Townhouse

A townhouse is the term historically used in the United Kingdom, Ireland and in many other countries to describe a residence of a peer or member of the aristocracy in the capital or major city. Most such figures owned one or more country houses in which they lived for much of the year...

. As a result he is often overlooked today, remembered principally for his Palladian remodelling of numerous country houses, many of them situated in the East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

area of Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

. As Brettingham neared the pinnacle of his career, Palladianism began to fall out of fashion and neoclassicism

Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism is the name given to Western movements in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that draw inspiration from the "classical" art and culture of Ancient Greece or Ancient Rome...

was introduced, championed by the young Robert Adam

Robert Adam

Robert Adam was a Scottish neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam , Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and trained under him...

.

Early life

Brettingham was born in 1699, the second son of Launcelot Brettingham (1664–1727), a bricklayerBricklayer

A bricklayer or mason is a craftsman who lays bricks to construct brickwork. The term also refers to personnel who use blocks to construct blockwork walls and other forms of masonry. In British and Australian English, a bricklayer is colloquially known as a "brickie".The training of a trade in...

or stonemason from Norwich

Norwich

Norwich is a city in England. It is the regional administrative centre and county town of Norfolk. During the 11th century, Norwich was the largest city in England after London, and one of the most important places in the kingdom...

, the county town

County town

A county town is a county's administrative centre in the United Kingdom or Ireland. County towns are usually the location of administrative or judicial functions, or established over time as the de facto main town of a county. The concept of a county town eventually became detached from its...

of Norfolk

Norfolk

Norfolk is a low-lying county in the East of England. It has borders with Lincolnshire to the west, Cambridgeshire to the west and southwest and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the North Sea coast and to the north-west the county is bordered by The Wash. The county...

, England. He married Martha Bunn (c. 1697–1783) at St. Augustine's Church, Norwich, on 17 May 1721 and they had nine children together.

His early life is little documented, and one of the earliest recorded references to him is in 1719, when he and his elder brother Robert were admitted to the city of Norwich as freemen bricklayers. A critic of Brettingham's at this time claimed that his work was so poor that it was not worth the nine shilling

Shilling

The shilling is a unit of currency used in some current and former British Commonwealth countries. The word shilling comes from scilling, an accounting term that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times where it was deemed to be the value of a cow in Kent or a sheep elsewhere. The word is thought to derive...

s a week (£ in ) he was paid as a craftsman

Artisan

An artisan is a skilled manual worker who makes items that may be functional or strictly decorative, including furniture, clothing, jewellery, household items, and tools...

bricklayer. Whatever the quality of his bricklaying, he soon advanced himself and became a building contractor

Independent contractor

An independent contractor is a natural person, business, or corporation that provides goods or services to another entity under terms specified in a contract or within a verbal agreement. Unlike an employee, an independent contractor does not work regularly for an employer but works as and when...

.

Local contractor

Cottage

__toc__In modern usage, a cottage is usually a modest, often cozy dwelling, typically in a rural or semi-rural location. However there are cottage-style dwellings in cities, and in places such as Canada the term exists with no connotations of size at all...

s and agricultural buildings. In 1731, it is recorded that he was paid £112 (£ in ) for his work on Norwich Gaol. From then, he appears to have worked regularly as the surveyor to the Justices (the contemporary local authority) on public buildings and bridge

Bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span physical obstacles such as a body of water, valley, or road, for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle...

s throughout the 1740s. Projects of his dating from this time include the remodelling of the Shirehouse in Norwich, the construction of Lenwade

Lenwade

Lenwade is a hamlet in the civil parish of Great Witchingham, Norfolk. Located in the Wensum Valley and adjacent to the A1067 road and being south-east of Fakenham and some north-west of Norwich.- Etymology:...

Bridge over the river Wensum

River Wensum

The River Wensum is a chalk fed river in Norfolk, England and a tributary of the River Yare despite being the larger of the two rivers. The complete river is a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest and Special Area of Conservation ....

, repairs to Norwich Castle

Norwich Castle

Norwich Castle is a medieval royal fortification in the city of Norwich, in the English county of Norfolk. It was founded in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England when William the Conqueror ordered its construction because he wished to have a fortified place in the important city of...

and Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral is a cathedral located in Norwich, Norfolk, dedicated to the Holy and Undivided Trinity. Formerly a Catholic church, it has belonged to the Church of England since the English Reformation....

, as well as the rebuilding of much of St. Margaret's Church, King's Lynn

King's Lynn

King's Lynn is a sea port and market town in the ceremonial county of Norfolk in the East of England. It is situated north of London and west of Norwich. The population of the town is 42,800....

, which had been severely damaged by the collapse of its spire in 1742. His work on the Shirehouse, which was in the gothic

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is a style of architecture that flourished during the high and late medieval period. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture....

style and showed a versatility of design rare for Brettingham, was to result in a protracted court case that was to rumble on through a large part of his life, with allegations of financial discrepancies. In 1755, the case was eventually closed, and Brettingham was left several hundred pounds

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

out of pocket—several tens of thousands, in present-day terms—and with a stain—if only a local one—on his character. Transcripts of the case suggest that it was Brettingham's brother Robert, to whom he had subcontracted and who was responsible for the flint stonework of the Shirehouse, who may have been the cause of the allegations. Brettingham's brief flirtation with the Gothic style, in the words of Robin Lucas, indicates "the approach of an engineer rather than an antiquary" and is "now seen as outlandish". The Shirehouse was demolished in 1822.

Architect

William Kent

William Kent , born in Bridlington, Yorkshire, was an eminent English architect, landscape architect and furniture designer of the early 18th century.He was baptised as William Cant.-Education:...

and Lord Burlington

Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington

Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and 4th Earl of Cork PC , born in Yorkshire, England, was the son of Charles Boyle, 2nd Earl of Burlington and 3rd Earl of Cork...

, were collaboratively designing a grandiose Palladian country palace

Palace

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word itself is derived from the Latin name Palātium, for Palatine Hill, one of the seven hills in Rome. In many parts of Europe, the...

at Holkham

Holkham

Holkham is a village and civil parish in the north-west of the county of Norfolk, England. Besides the small village, the parish includes the major stately home and estate of Holkham Hall, and an attractive beach at Holkham Gap...

in Norfolk for Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester

Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester (fifth creation)

Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester, KB was a wealthy English land-owner and patron of the arts. He is particularly noted for commissioning the design and construction of Holkham Hall in north Norfolk. Between 1722 and 1728, he was Member of Parliament for Norfolk.He was the son of Edward Coke ...

. Brettingham was appointed Clerk of Works

Clerk of Works

Clerks of Works are the most highly qualified non-commissioned tradesmen in the Royal Engineers. The qualification can be held in three specialisations: Electrical, Mechanical and Construction. The clerk of works , often abbreviated CoW, is employed by the architect or client on a construction site...

(sometimes referred to as executive architect), at an annual salary of £50 (£ per year in ). He retained the position until the Earl's death in 1759. The illustrious architects were mostly absent; indeed Burlington was more of an idealist than an architect, thus Brettingham and the patron Lord Leicester were left to work on the project together, with the practical Brettingham interpreting the architects' plans to Leicester's requirements. It was at Holkham that Brettingham first worked with the fashionable Palladian style, which was to be his trademark. Holkham was to be Brettingham's springboard to fame, as it was through his association with it that he came to the attention of other local patron

Patrón

Patrón is a luxury brand of tequila produced in Mexico and sold in hand-blown, individually numbered bottles.Made entirely from Blue Agave "piñas" , Patrón comes in five varieties: Silver, Añejo, Reposado, Gran Patrón Platinum and Gran Patrón Burdeos. Patrón also sells a tequila-coffee blend known...

s, and further work at Heydon and Honingham established Brettingham as a local country-house architect.

Brettingham was commissioned in 1742 to redesign Langley Hall

Langley Hall

Langley Hall is a red-brick building in the Palladian style, located in Loddon, Norfolk. It was built in 1737 for Richard Berney, on land that until the Dissolution of the Monasteries belonged to Langley Abbey, and sold two years later to George Proctor to enable Berney to repay his debts...

, a mansion

Mansion

A mansion is a very large dwelling house. U.S. real estate brokers define a mansion as a dwelling of over . A traditional European mansion was defined as a house which contained a ballroom and tens of bedrooms...

standing in its own park

Park

A park is a protected area, in its natural or semi-natural state, or planted, and set aside for human recreation and enjoyment, or for the protection of wildlife or natural habitats. It may consist of rocks, soil, water, flora and fauna and grass areas. Many parks are legally protected by...

land in South Norfolk. His design was very much in the Palladian style of Holkham, though much smaller: a large principal central block linked to two flanking secondary wings by short corridors. The corner tower

Tower

A tower is a tall structure, usually taller than it is wide, often by a significant margin. Towers are distinguished from masts by their lack of guy-wires....

s, while similar to those later designed by Brettingham at Euston Hall

Euston Hall

Euston Hall is a country house, with park by William Kent and Capability Brown located in Euston, small village located just south of Thetford in Suffolk, England. It is the family home of the Dukes of Grafton....

, were the work of a later owner and architect. The neoclassical

Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism is the name given to Western movements in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that draw inspiration from the "classical" art and culture of Ancient Greece or Ancient Rome...

entrance lodges were a later addition, by Sir John Soane

John Soane

Sir John Soane, RA was an English architect who specialised in the Neo-Classical style. His architectural works are distinguished by their clean lines, massing of simple form, decisive detailing, careful proportions and skilful use of light sources...

. In 1743, Brettingham began work on the construction of Hanworth Hall, Norfolk, also in the Palladian style, with a five-bay facade

Facade

A facade or façade is generally one exterior side of a building, usually, but not always, the front. The word comes from the French language, literally meaning "frontage" or "face"....

of brick

Brick

A brick is a block of ceramic material used in masonry construction, usually laid using various kinds of mortar. It has been regarded as one of the longest lasting and strongest building materials used throughout history.-History:...

with the centre three bays projected with a pediment

Pediment

A pediment is a classical architectural element consisting of the triangular section found above the horizontal structure , typically supported by columns. The gable end of the pediment is surrounded by the cornice moulding...

.

In 1745, Brettingham designed Gunton Hall in Norfolk for Sir William Harbord

Baron Suffield

Baron Suffield, of Suffield in the County of Norfolk, is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1786 for Sir Harbord Harbord, 2nd Baronet, who had previously represented Norwich in the House of Commons for thirty years...

, three years after the former house on the site was gutted by fire. The new house of brick had a principal facade like that of Hanworth Hall, however, this larger house was seven bays deep, and had a large service wing on its western side. His commissions began to come from further afield: Goodwood

Goodwood House

Goodwood House is a country house in West Sussex in southern England. It is the seat of the Dukes of Richmond. Several architects have contributed to the design of the house, including James Wyatt. It was the intention to build the house to a unique octagonal layout, but only three of the eight...

in Sussex and Marble Hill, Twickenham

Twickenham

Twickenham is a large suburban town southwest of central London. It is the administrative headquarters of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames and one of the locally important district centres identified in the London Plan...

.

Euston Hall

Euston Hall is a country house, with park by William Kent and Capability Brown located in Euston, small village located just south of Thetford in Suffolk, England. It is the family home of the Dukes of Grafton....

in East Anglia, the Suffolk country seat of the influential 2nd Duke of Grafton

Charles FitzRoy, 2nd Duke of Grafton

Charles FitzRoy, 2nd Duke of Grafton KG PC was an Irish and English politician.He was born the only child of Henry FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Grafton and Isabella Bennet, 2nd Countess of Arlington...

. The original house, built circa 1666 in the French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

style, was built around a central court

Courtyard

A court or courtyard is an enclosed area, often a space enclosed by a building that is open to the sky. These areas in inns and public buildings were often the primary meeting places for some purposes, leading to the other meanings of court....

with large pavilions

Pavilion (structure)

In architecture a pavilion has two main meanings.-Free-standing structure:Pavilion may refer to a free-standing structure sited a short distance from a main residence, whose architecture makes it an object of pleasure. Large or small, there is usually a connection with relaxation and pleasure in...

at each corner. While keeping the original layout, Brettingham formalised the fenestration

Window

A window is a transparent or translucent opening in a wall or door that allows the passage of light and, if not closed or sealed, air and sound. Windows are usually glazed or covered in some other transparent or translucent material like float glass. Windows are held in place by frames, which...

and imposed a more classically severe order whereby the pavilions were transformed to towers in the Palladian fashion (similar to those of Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones is the first significant British architect of the modern period, and the first to bring Italianate Renaissance architecture to England...

's at Wilton House

Wilton House

Wilton House is an English country house situated at Wilton near Salisbury in Wiltshire. It has been the country seat of the Earls of Pembroke for over 400 years....

). The pavilions' dome

Dome

A dome is a structural element of architecture that resembles the hollow upper half of a sphere. Dome structures made of various materials have a long architectural lineage extending into prehistory....

s were replaced by low pyramid

Pyramid

A pyramid is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge at a single point. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilateral, or any polygon shape, meaning that a pyramid has at least three triangular surfaces...

roofs similar to those at Holkham. Brettingham also created the large service courtyard at Euston that now acts as the entrance court to the mansion, which today is only a fraction of its former size.

The Euston commission seems to have brought Brettingham firmly to the notice of other wealthy patrons. In 1751, he began work for the Earl of Egremont

Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont

Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont, PC and Catherine née Seymour, succeeded his uncle, Algernon Seymour, 7th Duke of Somerset, as 2nd Earl of Egremont in 1750...

at Petworth House

Petworth House

Petworth House in Petworth, West Sussex, England, is a late 17th-century mansion, rebuilt in 1688 by Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset, and altered in the 1870s by Anthony Salvin...

, Sussex. He continued work intermittently at Petworth for the next twelve years, including designing a new picture gallery from 1754. Over the same period his country-house work included alterations at Moor Park, Hertfordshire

Moor Park, Hertfordshire

Moor Park Estate is a private residential estate in north-west London. The area borders Northwood, London and is part of the affluent suburb of Ruislip. It takes its name from Moor Park, a country house which was originally built in 1678–9 for James, Duke of Monmouth, and was reconstructed...

; Wortley Hall

Wortley Hall

Wortley Hall is a stately home in the small South Yorkshire village of Wortley, located west of Barnsley. For more than five decades the hall has been chiefly associated with the British Labour movement...

, Yorkshire; Wakefield Lodge, Northamptonshire; and Benacre House, Suffolk.

London townhouses

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

as well as Norwich. This period marks a turning point in his career, as he was now no longer designing country houses and farm buildings just for the local aristocrats and the Norfolk gentry

Gentry

Gentry denotes "well-born and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past....

, but for the greater aristocracy based in London.

One of Brettingham's greatest solo commissions came when he was asked to design a town house for the 9th Duke of Norfolk

Edward Howard, 9th Duke of Norfolk

Edward Howard, 9th Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal was a British peer. The son of Lord Thomas Howard and Mary Elizabeth Savile, he succeeded as Duke of Norfolk in 1732, after the death of his brother, Thomas Howard, 8th Duke of Norfolk.He married Mary Blount , daughter of Edward Blount and Anne...

in St. James's Square

St. James's Square

St. James's Square is the only square in the exclusive St James's district of the City of Westminster. It has predominantly Georgian and neo-Georgian architecture and a private garden in the centre...

, London. Completed in 1756, the exterior of this mansion was similar to those of many of the great palazzi in Italian cities: bland and featureless, the piano nobile

Piano nobile

The piano nobile is the principal floor of a large house, usually built in one of the styles of classical renaissance architecture...

distinguishable only by its tall pedimented windows. This arrangement, devoid of pilaster

Pilaster

A pilaster is a slightly-projecting column built into or applied to the face of a wall. Most commonly flattened or rectangular in form, pilasters can also take a half-round form or the shape of any type of column, including tortile....

s and a pediment giving prominence to the central bays at roof height, was initially too severe for the English taste, even by the fashionable Palladian standards of the day. Early critics declared the design "insipid".

_house_pall_mall.jpg)

Norfolk House

Norfolk House, at 31 St James's Square, London, was built in 1722 for the Duke of Norfolk. It was a royal residence for a short time only, when Frederick, Prince of Wales, father of King George III, lived there 1737-1741, after his marriage in 1736 to Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, daughter of...

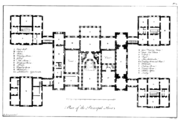

was to define the London town house for the next century. The floor plan was based on an adaptation of one of the secondary wings he had built at Holkham Hall

Holkham Hall

Holkham Hall is an eighteenth-century country house located adjacent to the village of Holkham, on the north coast of the English county of Norfolk...

. A circuit of reception rooms centred on a grand staircase, with the staircase hall replacing the Italian traditional inner courtyard or two-storey hall. This arrangement of salons allowed guests at large parties to circulate, having been received at the head of the staircase, without doubling back on arriving guests. The second advantage was that while each room had access to the next, it also had access to the central stairs, thus allowing only one or two rooms to be used at a time for smaller functions. Previously, guests in London houses had had to reach the principal salon through a long enfilade of minor reception rooms. In this square and compact way, Brettingham came close to recreating the layout of an original Palladian Villa. He transformed what Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio was an architect active in the Republic of Venice. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily by Vitruvius, is widely considered the most influential individual in the history of Western architecture...

had conceived as a country retreat into a London mansion appropriate for the lifestyle of the British aristocracy, with its reversal of the usual Italian domestic pattern of a large palazzo in town, and a smaller villa in the country. As happened so often in Brettingham's career, Robert Adam later developed this design concept further, and was credited with its success. However, Brettingham's plan for Norfolk House was to serve as the prototype

Prototype

A prototype is an early sample or model built to test a concept or process or to act as a thing to be replicated or learned from.The word prototype derives from the Greek πρωτότυπον , "primitive form", neutral of πρωτότυπος , "original, primitive", from πρῶτος , "first" and τύπος ,...

for many London mansions over the next few decades.

Brettingham's additional work in London included two more houses in St. James's Square: No. 5 for the 2nd Earl of Strafford

William Wentworth, 2nd Earl of Strafford (1722-1791)

William Wentworth, 2nd Earl of Strafford , styled Viscount Wentworth until 1739 was a peer and member of the House of Lords of Great Britain.-Ancestry and career:...

and No. 13 for the 1st Lord Ravensworth

Henry Liddell, 1st Baron Ravensworth

Henry Liddell, 1st Baron Ravensworth succeeded to the Baronetcy of Ravensworth Castle, and to the family estates and mining interests, at the age of fifteen, on the death of his grandfather in 1723...

. Lord Egremont, for whom Brettingham was working in the country at Petworth, gave Brettingham another opportunity to design a grandiose London mansion—the Egremont family's town house. Begun in 1759, this Palladian palace, known at the time as Egremont House, or more modestly as 94 Piccadilly, is one of the few great London town houses still standing. It later came to be known as Cambridge House

Cambridge House

Cambridge House is a grade I listed mansion on the northern side of Piccadilly in central London, England. It was built for Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont, by architect Matthew Brettingham in 1756-1761. It was initially known as Egremont House. The house is in a late Palladian style. It has...

and was the home of Lord Palmerston

Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, KG, GCB, PC , known popularly as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman who served twice as Prime Minister in the mid-19th century...

, and then of the Naval & Military Club

Naval & Military Club

The Naval and Military Club is a gentlemen's club in London, England. It was founded in 1862 because the three then existing military clubs in London - the United Service, the Junior United Service and the Army and Navy - were all full. The membership was long restricted to military officers...

; as of October 2007, it is in the process of conversion into a luxury hotel.

Kedleston Hall

James Gibbs

James Gibbs was one of Britain's most influential architects. Born in Scotland, he trained as an architect in Rome, and practised mainly in England...

, one of the leading architects of the day, but Curzon wanted his new house to match the style and taste of Holkham. Lord Leicester, Holkham's owner and Brettingham's employer, was a particular hero of Curzon's. Curzon was a Tory

Tory

Toryism is a traditionalist and conservative political philosophy which grew out of the Cavalier faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It is a prominent ideology in the politics of the United Kingdom, but also features in parts of The Commonwealth, particularly in Canada...

from a very old Derbyshire family, and he wished to create a showpiece to rival the nearby Chatsworth House

Chatsworth House

Chatsworth House is a stately home in North Derbyshire, England, northeast of Bakewell and west of Chesterfield . It is the seat of the Duke of Devonshire, and has been home to his family, the Cavendish family, since Bess of Hardwick settled at Chatsworth in 1549.Standing on the east bank of the...

owned by the Whig

British Whig Party

The Whigs were a party in the Parliament of England, Parliament of Great Britain, and Parliament of the United Kingdom, who contested power with the rival Tories from the 1680s to the 1850s. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute rule...

Duke of Devonshire

Duke of Devonshire

Duke of Devonshire is a title in the peerage of England held by members of the Cavendish family. This branch of the Cavendish family has been one of the richest and most influential aristocratic families in England since the 16th century, and have been rivalled in political influence perhaps only...

, whose family were relative newcomers in the county, having arrived little more than two hundred years earlier. However, the Duke of Devonshire's influence, wealth, and title were far superior to Curzon's, and Curzon was unable to complete his house or to match the Devonshires' influence (William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire

William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire

William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, KG, PC , styled Lord Cavendish before 1729 and Marquess of Hartington between 1729 and 1755, was a British Whig statesman who was briefly nominal Prime Minister of Great Britain...

, had been Prime Minister in the 1750s). This commission might have been the ultimate accolade Brettingham was seeking, to recreate Holkham but this time with full credit. Kedleston Hall

Kedleston Hall

Kedleston Hall is an English country house in Kedleston, Derbyshire, approximately four miles north-west of Derby, and is the seat of the Curzon family whose name originates in Notre-Dame-de-Courson in Normandy...

was designed by Brettingham on a plan by Palladio for the unbuilt Villa Mocenigo. The design by Brettingham, similar to that of Holkham Hall, was for a massive principal central block flanked by four secondary wings, each a miniature country house, themselves linked by quadrant

Quadrant (architecture)

Quadrant in architecture refers to a curve in a wall or a vaulted ceiling. Generally considered to be an arc of 90 degrees - one quarter of a circle, or a half of the more commonly seen architectural feature - a crescent....

corridors. From the outset of the project, Curzon seems to have presented Brettingham with rivals. In 1759, while Brettingham was still supervising the construction of the initial phase, the northeast family block, Curzon employed architect James Paine, the most notable architect of the day, to supervise the kitchen block and quadrants. Paine also went on to supervise the construction of Brettingham's great north front. However, this was a critical moment for architecture in England. Palladianism was being challenged by a new taste for neoclassical designs, one exponent of which was Robert Adam

Robert Adam

Robert Adam was a Scottish neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam , Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and trained under him...

. Curzon had met Adam as early as 1758, and had been impressed by the young architect newly returned from Rome. He employed Adam to design some garden pavilions

Pavilion (structure)

In architecture a pavilion has two main meanings.-Free-standing structure:Pavilion may refer to a free-standing structure sited a short distance from a main residence, whose architecture makes it an object of pleasure. Large or small, there is usually a connection with relaxation and pleasure in...

for the new Kedleston. So impressed was Curzon by Adam's work that by April 1760 he had put Adam in sole charge of the design of the new mansion, replacing both Brettingham and Paine. Adam completed the north facade of the mansion much as Brettingham had designed it, only altering Brettingham's intended portico. The basic layout of the house remained loyal to Brettingham's original plan, although only two of the proposed four secondary wings were executed.

Brettingham moved on to other projects. In the 1760s, he was approached by his most illustrious patron, the Duke of York (brother of King George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

), to design one of the greatest mansions in Pall Mall

Pall Mall, London

Pall Mall is a street in the City of Westminster, London, and parallel to The Mall, from St. James's Street across Waterloo Place to the Haymarket; while Pall Mall East continues into Trafalgar Square. The street is a major thoroughfare in the St James's area of London, and a section of the...

, namely York House. The rectangular mansion that Brettingham designed was built in the Palladian style on two principal floors, with the state room

State room

A state room in a large European mansion is usually one of a suite of very grand rooms which were designed to impress. The term was most widely used in the 17th and 18th centuries. They were the most lavishly decorated in the house and contained the finest works of art...

s as at Norfolk House, arranged in a circuit around the central staircase hall. The house was a mere pastiche

Pastiche

A pastiche is a literary or other artistic genre or technique that is a "hodge-podge" or imitation. The word is also a linguistic term used to describe an early stage in the development of a pidgin language.-Hodge-podge:...

of Norfolk House, but for Brettingham it had the kudos of a royal occupant.

Legacy

Packington Hall

Packington Hall is a 17th century mansion situated at Great Packington, near Meriden, Warwickshire, England the seat of the Earl of Aylesford. It is a Grade II* listed building....

, Warwickshire. In 1761, he published his plans of Holkham Hall, calling himself the architect, which led critics, including Horace Walpole, to decry him as a purloiner of Kent's designs. Brettingham died in 1769 at his house outside St. Augustine's Gate, Norwich, and was buried in the aisle of the parish church. Throughout his long career, Brettingham did much to popularise the Palladian movement. His clients included a Royal Duke and at least twenty-one assorted peers

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

and peeresses. He is not a household name today largely because his provincial work was heavily influenced by Kent and Burlington, and unlike his contemporary Giacomo Leoni

Giacomo Leoni

Giacomo Leoni , also known as James Leoni, was an Italian architect, born in Venice. He was a devotee of the work of Florentine Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti, who had also been an inspiration for Andrea Palladio. Leoni thus served as a prominent exponent of Palladianism in English...

he did not develop, or was not given the opportunity to develop, a strong personal stamp to his work on country houses. Ultimately, he and many of his contemporary architects were eclipsed by the designs of Robert Adam. Adam remodelled Brettingham's York House in 1780 and, in addition to Kedleston Hall, went on to replace James Paine as architect at Nostell Priory

Nostell Priory

Nostell Priory is a Palladian house located in Nostell, near Crofton close to Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England, approached by the Doncaster road from Wakefield...

, Alnwick Castle

Alnwick Castle

Alnwick Castle is a castle and stately home in the town of the same name in the English county of Northumberland. It is the residence of the Duke of Northumberland, built following the Norman conquest, and renovated and remodelled a number of times. It is a Grade I listed building.-History:Alnwick...

, and Syon House

Syon House

Syon House, with its 200-acre park, is situated in west London, England. It belongs to the Duke of Northumberland and is now his family's London residence...

. In spite of this, Adam and Paine remained great friends; Brettingham's relationships with his fellow architects are unrecorded.

Brettingham's principal contribution to architecture is perhaps the design of the grand town house, unremarkable for its exterior but with a circulating plan for reception rooms suitable for entertaining within on a forgotten scale of lavishness. Many of these anachronistic palaces are now long demolished or have been transformed for other uses and are inaccessible for public viewing. Hence, what little remains in London of his work is unknown to the general public. Of Brettingham's work, only the buildings he remodelled have survived, and for this reason Brettingham now tends to be thought of as an "improver" rather than an architect of country houses.

There is no evidence that Brettingham ever formally studied architecture or travelled abroad. Reports of him making two trips to Continental Europe, are the result of confusion with his son, Matthew Brettingham the Younger. That he enjoyed success in his own lifetime is beyond doubt—Robert Adam calculated that when Brettingham sent his son, Matthew, on the Grand Tour

Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the traditional trip of Europe undertaken by mainly upper-class European young men of means. The custom flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale rail transit in the 1840s, and was associated with a standard itinerary. It served as an educational rite of passage...

(1747), he went with a sum of money in his pocket of around £15,000 (£ in ), an enormous amount at the time. However, part of this sum was probably used to acquire the statuary in Italy (documented as supplied by Matthew Brettingham the Younger) for the nearly completed Holkham Hall. Matthew Brettingham the Younger wrote that his father "considered the building of Holkham as the great work of his life". While the design of that great monumental house, which still stands, cannot truly be accredited to him, it is the building for which Brettingham is best remembered.