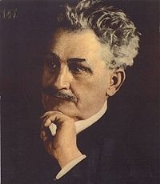

Leoš Janácek

Encyclopedia

Czech people

Czechs, or Czech people are a western Slavic people of Central Europe, living predominantly in the Czech Republic. Small populations of Czechs also live in Slovakia, Austria, the United States, the United Kingdom, Chile, Argentina, Canada, Germany, Russia and other countries...

composer, musical theorist

Music theory

Music theory is the study of how music works. It examines the language and notation of music. It seeks to identify patterns and structures in composers' techniques across or within genres, styles, or historical periods...

, folklorist

Folkloristics

Folkloristics is the formal academic study of folklore. The term derives from a nineteenth century German designation of folkloristik to distinguish between folklore as the content and folkloristics as its study, much as language is distinguished from linguistics...

, publicist and teacher. He was inspired by Moravia

Moravian traditional music

Moravian traditional music represents a part of the European musical culture connected with the regions around the western Carpathian Mountains. It is characterized by a specific melodic and harmonic texture related to the Eastern European musical world...

n and all Slavic

Slavic peoples

The Slavic people are an Indo-European panethnicity living in Eastern Europe, Southeast Europe, North Asia and Central Asia. The term Slavic represents a broad ethno-linguistic group of people, who speak languages belonging to the Slavic language family and share, to varying degrees, certain...

folk music to create an original, modern musical style. Until 1895 he devoted himself mainly to folkloristic research and his early musical output was influenced by contemporaries such as Antonín Dvořák

Antonín Dvorák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák was a Czech composer of late Romantic music, who employed the idioms of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia. Dvořák’s own style is sometimes called "romantic-classicist synthesis". His works include symphonic, choral and chamber music, concerti, operas and many...

. His later, mature works incorporate his earlier studies of national folk music in a modern, highly original synthesis, first evident in the opera Jenůfa

Jenufa

Jenůfa is an opera in three acts by Leoš Janáček to a Czech libretto by the composer, based on the play Její pastorkyňa by Gabriela Preissová. It was first performed at the Brno Theater, Brno, 21 January 1904...

, which was premiered in 1904 in Brno. The success of Jenůfa (often called the "Moravian national opera") at Prague in 1916 gave Janáček access to the world's great opera stages. Janáček's later works are his most celebrated. They include the symphonic poem Sinfonietta

Sinfonietta (Janácek)

The Sinfonietta is a very expressive and festive, late work for large orchestra by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček...

, the oratorio

Oratorio

An oratorio is a large musical composition including an orchestra, a choir, and soloists. Like an opera, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias...

Glagolitic Mass

Glagolitic Mass

The Glagolitic Mass is a composition for soloists , double chorus, organ and orchestra by Leoš Janáček. The work was completed on 15 October 1926...

, the rhapsody Taras Bulba

Taras Bulba (rhapsody)

Taras Bulba is a rhapsody for orchestra by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček. It was composed in 1918 and belongs to the most powerful of Janáček's scores. It is based on the novel by Gogol....

, string quartets, other chamber works and operas. He is considered to rank with Antonín Dvořák and Bedřich Smetana

Bedrich Smetana

Bedřich Smetana was a Czech composer who pioneered the development of a musical style which became closely identified with his country's aspirations to independent statehood. He is thus widely regarded in his homeland as the father of Czech music...

, as one of the most important Czech composers.

Early life

Hukvaldy

Hukvaldy is a village in the Czech Republic, in the Moravian-Silesian Region. Population: 1,900. It lies 150m below the ruins of the third largest castle in the Czech Republic, Hukvaldy Castle , and is the birthplace of the composer Leoš Janáček and palaeontologist Ferdinand Stoliczka.The castle...

, Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

, (then part of the Austrian Empire

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

). He was a gifted child in a family of limited means, and showed an early musical talent in choral singing. His father wanted him to follow the family tradition, and become a teacher, but deferred to Janáček's obvious musical abilities. In 1865 young Janáček enrolled as a ward of the foundation of the Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno, where he took part in choral singing under Pavel Křížkovský

Pavel Krížkovský

Pavel Křížkovský was a Czech choral composer and conductor.Křížkovský was born in Kreuzendorf, Opava District, Austrian Silesia. He was a chorister in a monastery in Opava when young, and studied at the Faculty of Philosophy of University of Olomouc and later in Brno...

and occasionally played the organ

Organ (music)

The organ , is a keyboard instrument of one or more divisions, each played with its own keyboard operated either with the hands or with the feet. The organ is a relatively old musical instrument in the Western musical tradition, dating from the time of Ctesibius of Alexandria who is credited with...

. One of his classmates, František Neumann, later described Janáček as an "excellent pianist, who played Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven was a German composer and pianist. A crucial figure in the transition between the Classical and Romantic eras in Western art music, he remains one of the most famous and influential composers of all time.Born in Bonn, then the capital of the Electorate of Cologne and part of...

symphonies perfectly in a piano duet with a classmate, under Křížkovský's supervision". Křížkovský found him a problematic and wayward student but recommended his entry to the Prague Organ School. Janáček later remembered Křížkovský as a great conductor and teacher.

Janáček originally intended to study piano and organ but eventually devoted himself to composition. He wrote his first vocal compositions while choirmaster of the Svatopluk Artisan's Association (1873–76). In 1874 he enrolled at the Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

organ school, under František Skuherský

František Zdenek Skuherský

František Zdeněk Xavier Alois Skuherský was a Czech composer, pedagogue, and theoretician.Born in Opočno to František Alois Skuherský, the doctor of Duke Colloredo-Mansfeld and founder of the Opočno hospital. He graduated from the Hradec Králové gymnasium and studied philosophy and shortly...

and František Blažek. His student days in Prague were impoverished; with no piano in his room, he had to make do with a keyboard drawn on his tabletop. His criticism of Skuherský's performance of the Gregorian mass was published in the March 1875 edition of the journal Cecilie and led to his expulsion from the school – but Skuherský relented, and on 24 July 1875 Janáček graduated with the best results in his class. On his return to Brno he earned a living as a music teacher, and conducted various amateur choir

Choir

A choir, chorale or chorus is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform.A body of singers who perform together as a group is called a choir or chorus...

s. From 1876 he taught music at Brno's Teachers Institute. Among his pupils there was Zdenka Schulzová, daughter of Emilian Schulz, the Institute director. She was later to be Janáček's wife. In 1876 he also became a piano student of Amálie Wickenhauserová-Nerudová, with whom he co-organized chamber concertos and performed in concerts over the next two years. In February, 1876, he was voted choirmaster of the Beseda brněnská Philharmonic Society. Apart from an interruption from 1879 to 1881, he remained its choirmaster and conductor until 1888.

From October 1879 to February 1880 he studied piano, organ, and composition at the Leipzig Conservatory

Felix Mendelssohn College of Music and Theatre

The University of Music and Theatre "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy" Leipzig is a public university in Leipzig . Founded in 1843 by Felix Mendelssohn as the Conservatory of Music, it is the oldest university school of music in Germany....

. While there, he composed Thema con variazioni for piano in B flat, subtitled Zdenka's Variations. Dissatisfied with his teachers (among them Oskar Paul and Leo Grill), and denied a studentship with Saint-Saëns

Camille Saint-Saëns

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns was a French Late-Romantic composer, organist, conductor, and pianist. He is known especially for The Carnival of the Animals, Danse macabre, Samson and Delilah, Piano Concerto No. 2, Cello Concerto No. 1, Havanaise, Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, and his Symphony...

in Paris, Janáček moved on to the Vienna Conservatory where from April to June 1880 he studied composition with Franz Krenn

Franz Krenn

Franz Krenn was an Austrian composer and composition teacher.Born in Droß, Krenn studied under Ignaz von Seyfried in Vienna. He served as organist in a number of Viennese churches and in 1862 became Kapellmeister of the Vienna Hofkirche...

. He concealed his opposition to Krenn's neo-romanticism, but he quit Joseph Dachs's classes and further piano study when he was criticised for his piano style and technique. He submitted a violin sonata (now lost) to a Vienna Conservatory competition, but the judges rejected it as "too academic". Janáček left the conservatory in June, 1880, disappointed despite Franz Krenn's very complimentary personal report. He returned to Brno

Brno

Brno by population and area is the second largest city in the Czech Republic, the largest Moravian city, and the historical capital city of the Margraviate of Moravia. Brno is the administrative centre of the South Moravian Region where it forms a separate district Brno-City District...

where on 13 July 1881, he married his young pupil Zdenka Schulzová.

Janáček was appointed director of the organ school, and held this post until 1919, when the school became the Brno Conservatory. In the mid 1880s Janáček began composing more systematically. Among other works, he created the Four male-voice choruses (1886), dedicated to Antonín Dvořák, and his first opera, Šárka (1887–8). During this period he began to collect and study folk music, songs and dances. In the early months of 1887 he sharply criticized the comic opera The Bridegrooms, by Czech composer Karel Kovařovic

Karel Kovarovic

Karel Kovařovic was a Czech composer and conductor.-Life:From 1873 to 1879 he studied clarinet, harp and piano at the Prague Conservatory. He began his career as a harpist...

, in a Hudební listy journal review: "Which melody stuck in your mind? Which motif? Is this dramatic opera? No, I would write on the poster: "Comedy performed together with music", since the music and the libretto aren't connected to each other". Janáček's review apparently led to mutual dislike and later professional difficulties when Kovařovic, as director of the National Theatre in Prague

National Theatre (Prague)

The National Theatre in Prague is known as the Alma Mater of Czech opera, and as the national monument of Czech history and art.The National Theatre belongs to the most important Czech cultural institutions, with a rich artistic tradition which was created and maintained by the most distinguished...

, refused to stage Janáček's opera Jenůfa.

From the early 1890s, Janáček led the mainstream of folklorist activity in Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

and Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

, using a repertoire of folksongs and dances in orchestral and piano arrangements. Most of his achievements in this field were published in 1899–1901 though his interest in folklore would be lifelong. His compositional work was still influenced by the declamatory, dramatic style of Smetana

Bedrich Smetana

Bedřich Smetana was a Czech composer who pioneered the development of a musical style which became closely identified with his country's aspirations to independent statehood. He is thus widely regarded in his homeland as the father of Czech music...

and Dvořák. He expressed very negative opinions on German neo-classicism and especially on Wagner

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner was a German composer, conductor, theatre director, philosopher, music theorist, poet, essayist and writer primarily known for his operas...

in the Hudební listy journal, which he founded in 1884. The death of his second child, Vladimír, in 1890 was followed by an attempted opera, Beginning of the Romance (1891) and the cantata

Cantata

A cantata is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, typically in several movements, often involving a choir....

Amarus

Amarus

Amarus is a cantata composed by Czech composer Leoš Janáček, consisting of five movements. It was completed in 1897, having been started after Janáček's visit to Russia the previous summer....

(1897).

Later years and masterworks

In the first decade of the 20th century Janáček composed choral church music including Otčenáš (Our Father, 1901), Constitutes (1903) and Ave Maria (1904). In 1901 the first part of his piano cycle On an Overgrown Path was published, and gradually became one of his most frequently performed works. In 1902 Janáček visited RussiaRussia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

twice. On the first occasion he took his daughter Olga to St.Petersburg, where she stayed to study Russian. Only three months later, he returned to St. Petersburg with his wife because Olga was very ill. They took her back to Brno, but her health was worsening. Janáček expressed his painful feelings for his daughter in a new work, his opera Jenůfa, in which the suffering of his daughter became Jenůfa's. When Olga died in February 1903, Janáček dedicated Jenůfa to her memory. The opera was performed in Brno in 1904, with reasonable success, but Janáček felt this was no more than a provincial achievement. He aspired to recognition by the more influential Prague opera, but Jenůfa was refused there (twelve years passed before its first performance in Prague). Dejected and emotionally exhausted, Janáček went to Luhačovice

Luhacovice

Luhačovice is a spa town in the Zlín Region, Moravia, Czech Republic.It occupies a valley, whose elevation is a minimum of 250 m above sea level...

spa to recover. There he met Kamila Urválková, whose love story supplied the theme for his next opera, Osud (Destiny).

Petr Bezruc

Petr Bezruč was the pseudonym of Vladimír Vašek , a Czech poet and short story writer who was associated with the region of Austrian Silesia.Bezruč was born in Opava and died in Olomouc.- Works :Poetry...

, with whom he later collaborated, composing several choral works based on Bezruč's poetry. These included Kantor Halfar (1906), Maryčka Magdónova (1908), and Sedmdesát tisíc (1909). Janáček's life in the first decade of the 20th century was complicated by personal and professional difficulties. He still yearned for artistic recognition from Prague. He destroyed some of his works – others remained unfinished. Nevertheless, he continued composing, and would create several remarkable choral, chamber, orchestral and operatic works, the most notable being the 1914 Cantata Věčné evangelium (The Eternal Gospel), Pohádka (Fairy tale) for violoncello and piano (1910), the 1912 piano cycle V mlhách (In the Mist) and his first symphonic poem Šumařovo dítě (A Fiddler's Child). His fifth opera, Výlet pana Broučka do měsíce, composed from 1908 to 1917, has been characterized as the most "purely Czech in subject and treatment" of all Janáček's operas.

In 1916 he started what would be a long professional and personal relationship with theatre critic, dramatist and translator Max Brod

Max Brod

Max Brod was a German-speaking Czech Jewish, later Israeli, author, composer, and journalist. Although he was a prolific writer in his own right, he is most famous as the friend and biographer of Franz Kafka...

.

In the same year Jenůfa, revised by Kovařovic, was finally accepted by the National Theatre; its performance in Prague (1916) was a great success, and brought Janáček his first acclaim. He was 62. Following the Prague première, he began a relationship with singer Gabriela Horváthová, which led to his wife Zdenka's attempted suicide and their "informal" divorce.

A year later (1917) he met Kamila Stösslová

Kamila Stösslová

Kamila Stösslová holds an unusual place in music history. The composer Leoš Janáček, upon meeting her in 1917 in the resort town of Luhačovice, fell deeply in love with her, despite both their marriages and the fact he was almost forty years older than Kamila...

, a young married woman 38 years his junior, who was to inspire him for the remaining years of his life. He conducted an obsessive and (on his side at least), passionate correspondence with her, of nearly 730 letters. From 1917 to 1919, deeply inspired by Stösslová, he composed The Diary of One Who Disappeared. As he completed its final revision, he began his next 'Kamila' work, the opera Káťa Kabanová.

Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore , sobriquet Gurudev, was a Bengali polymath who reshaped his region's literature and music. Author of Gitanjali and its "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse", he became the first non-European Nobel laureate by earning the 1913 Prize in Literature...

, and used a Tagore poem as the basis for the chorus The Wandering Madman (1922). At the same time he encountered the microtonal

Microtonal music

Microtonal music is music using microtones—intervals of less than an equally spaced semitone. Microtonal music can also refer to music which uses intervals not found in the Western system of 12 equal intervals to the octave.-Terminology:...

works of Alois Hába

Alois Hába

Alois Hába was a Czech composer, musical theorist and teacher. He is primarily known for his microtonal compositions, especially using the quarter tone scale, though he used others such as sixth-tones and twelfth-tones....

. In the early 1920s Janáček completed his opera The Cunning Little Vixen, which had been inspired by a serialized novella in the newspaper Lidové noviny

Lidové noviny

Lidové noviny is a daily newspaper published in the Czech Republic. It is the oldest Czech daily. Its profile is nowadays a national news daily covering political, economic, cultural and scientific affairs, mostly with a centre-right, conservative view...

.

In Janáček's 70th year (1924) his biography was published by Max Brod, and he was interviewed by Olin Downes

Olin Downes

Olin Downes was an American music critic.He studied piano, music theory, and music criticism in New York and Boston, and it was in those two cities that he made his career as a music critic—first with the Boston Post and then with the New York Times...

for the New York Times. In 1925 he retired from teaching, but continued composing and was awarded the first honorary doctorate to be given by Masaryk University

Masaryk University

Masaryk University is the second largest university in the Czech Republic, a member of the Compostela Group and the Utrecht Network. Founded in 1919 in Brno as the third Czech university , it now consists of nine faculties and 42,182 students...

in Brno. In the spring of 1926 he created the monumental orchestral work Sinfonietta, which rapidly gained wide critical acclaim. In the same year he went to England at the invitation of Rosa Newmarch

Rosa Newmarch

Rosa Newmarch was an English writer on music.-Biography:Rosa Harriet Jeaffreson was born in Leamington in 1857. She settled in London in 1880, when she began contributing articles to various literary journals. In 1883 she married Henry Charles Newmarch, thereafter using her married name in her...

. A number of his works were performed in London, including his first string quartet, the wind sextet Youth, and his violin sonata. Shortly after, and still in 1926, he started to compose a setting to an Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Church Slavic was the first literary Slavic language, first developed by the 9th century Byzantine Greek missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius who were credited with standardizing the language and using it for translating the Bible and other Ancient Greek...

text. The result was the large-scale orchestral Glagolitic Mass. Janáček was an atheist, and critical of the organised Church, but religious themes appear frequently in his work. The Glagolitic Mass was partly inspired by the suggestion by a clerical friend, and partly by Janáček's wish to celebrate the anniversary of Czechoslovak independence. In 1927 – the year of Sinfonietta's first performances in New York, Berlin and Brno – he began to compose his final operatic work, From the House of the Dead, the third Act of which was found on his desk after his death. In January 1928 he began his second string quartet, the "Intimate Letters", his "manifesto on love". Meanwhile, Sinfonietta was performed in London, Vienna and Dresden. In his later years, the still-active Janáček became an international celebrity. He became a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts

Akademie der Künste

The Akademie der Künste, Berlin is an arts institution in Berlin, Germany. It was founded in 1696 by Elector Frederick III of Brandenburg as the Prussian Academy of Arts, an academic institution where members could meet and discuss and share ideas...

in Berlin in 1927, along with Arnold Schönberg and Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith was a German composer, violist, violinist, teacher, music theorist and conductor.- Biography :Born in Hanau, near Frankfurt, Hindemith was taught the violin as a child...

. His operas and other works were finally performed at the world stages, though From the House of the Dead was first performed posthumously. In August 1928 he took an excursion to Štramberk

Štramberk

Štramberk is a small town in the Moravian-Silesian Region, Czech Republic, next to Kopřivnice. It lies on the slope of a forested lime hill, dominated by the Trúba castle tower...

with Kamila Stösslová and her son Otto, but caught a chill, which developed into pneumonia. He died on the 12 August 1928 in Ostrava

Ostrava

Ostrava is the third largest city in the Czech Republic and the second largest urban agglomeration after Prague. Located close to the Polish border, it is also the administrative center of the Moravian-Silesian Region and of the Municipality with Extended Competence. Ostrava was candidate for the...

, at the sanatorium of Dr. L. Klein. He was given a large public funeral, to music from the last scene of his Cunning Little Vixen, and was buried in the Field of Honour at the Central Cemetery, Brno.

Personality

Janáček's life was filled with work. He led the organ school, was a Professor at the teachers institute and gymnasium in Brno, collected his "speech tunes" and was composing. From an early age he presented himself as an individualist and his firmly formulated opinions often led to conflict. He unhesitatingly criticized his teachers, who considered him a defiant and anti-authoritarian student. His own students found him strict and uncompromising. Vilém TauskýVilém Tauský

Vilém Tauský CBE was a Czech conductor and composer.-Life:Vilém Tauský was from a musical family: his Viennese mother had sung Mozart at the Vienna State Opera under Gustav Mahler, and her cousin was the operetta composer Leo Fall.Tauský studied with Leoš Janáček and later became a repetiteur at...

, one of his pupils, described his encounters with Janáček as somewhat distressing for someone unused to his personality, and noted that Janáček's characteristically staccato speech rhythms were reproduced in some of his operatic characters. In 1881, Janáček gave up his leading role with the Beseda brněnská, as a response to criticism, but a rapid decline in "Beseda"s performance quality led to his recall in 1882.

His married life, settled and calm in its early years, became increasingly tense and difficult following the death of his daughter, Olga, in 1903. Years of effort in obscurity took their toll, and almost ended his ambitions as a composer.: "I was beaten down", he wrote later; "my own students gave me advices, how to compose, how to speak through orchestra". Success in 1916 – when Karel Kovařovic

Karel Kovarovic

Karel Kovařovic was a Czech composer and conductor.-Life:From 1873 to 1879 he studied clarinet, harp and piano at the Prague Conservatory. He began his career as a harpist...

finally decided to perform Jenůfa in Prague – brought its own problems. Janáček grudgingly resigned himself to the changes forced upon his work. Its success brought him into Prague's music scene and the attentions of soprano Gabriela Horvátová, who guided him through Prague society. Janáček was enchanted by her. On his return to Brno, he appears not to have concealed his new passion from Zdenka, who responded by attempting suicide. Janáček was furious with Zdenka and tried to instigate a divorce, but lost interest in Horvátová. Zdenka, anxious to avoid the public scandal of formal divorce, persuaded him to settle for an "informal" divorce. From then on, until Janáček's death, they would live separate lives in the same household.

In 1917 he began his lifelong, inspirational and unrequited passion for Kamila Stösslová

Kamila Stösslová

Kamila Stösslová holds an unusual place in music history. The composer Leoš Janáček, upon meeting her in 1917 in the resort town of Luhačovice, fell deeply in love with her, despite both their marriages and the fact he was almost forty years older than Kamila...

, who neither sought nor rejected his devotion. Janáček pleaded for first-name terms in their correspondence. In 1927 she finally agreed and signed herself "Tvá Kamila" (Your Kamila) in a letter, which Zdenka found. This revelation provoked a furious quarrel between Zdenka and Janáček, though their living arrangements did not change – Janáček seems to have persuaded her to stay. In 1928, the year of his death, Janáček confessed his intention to publicise his feelings for Stösslová. Max Brod

Max Brod

Max Brod was a German-speaking Czech Jewish, later Israeli, author, composer, and journalist. Although he was a prolific writer in his own right, he is most famous as the friend and biographer of Franz Kafka...

had to dissuade him. Janáček's contemporaries and collaborators described him as mistrustful and reserved, but capable of obsessive passion for those he loved. His overwhelming passion for Stösslová was sincere but verged upon self-destruction. Their letters remain an important source for Janáček's artistic intentions and inspiration. His letters to his long-suffering wife are, by contrast, mundanely descriptive. Zdenka seems to have destroyed all hers to Janáček. Only a few postcards survive.

Style

In 1874 Janáček became friends with Antonín DvořákAntonín Dvorák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák was a Czech composer of late Romantic music, who employed the idioms of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia. Dvořák’s own style is sometimes called "romantic-classicist synthesis". His works include symphonic, choral and chamber music, concerti, operas and many...

, and began composing in a relatively traditional romantic

Romantic music

Romantic music or music in the Romantic Period is a musicological and artistic term referring to a particular period, theory, compositional practice, and canon in Western music history, from 1810 to 1900....

style. After his opera Šárka

Šárka (Janácek)

Šárka is an opera in three acts by Leoš Janáček to a Czech libretto by Julius Zeyer, based on Bohemian legends of Šárka in Dalimil’s Chronicle...

(1887–1888), his style absorbed elements of Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

n and Slovak

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

folk music

Folk music

Folk music is an English term encompassing both traditional folk music and contemporary folk music. The term originated in the 19th century. Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted by mouth, as music of the lower classes, and as music with unknown composers....

.

His musical assimilation of the rhythm, pitch contour

Pitch contour

In linguistics, speech synthesis, and music, the pitch contour of a sound is a function or curve that tracks the perceived pitch of the sound over time....

and inflections of normal Czech speech helped create the very distinctive vocal melodies

Melody

A melody , also tune, voice, or line, is a linear succession of musical tones which is perceived as a single entity...

of his opera Jenůfa

Jenufa

Jenůfa is an opera in three acts by Leoš Janáček to a Czech libretto by the composer, based on the play Její pastorkyňa by Gabriela Preissová. It was first performed at the Brno Theater, Brno, 21 January 1904...

(1904), whose 1916 success in Prague was to be the turning point in his career. In Jenůfa, Janáček developed and applied the concept of "speech tunes" to build a unique musical and dramatic style quite independent of "Wagnerian" dramatic method. He studied the circumstances in which "speech tunes" changed, the psychology and temperament of speakers and the coherence within speech, all of which helped render the dramatically truthful roles of his mature operas, and became one of the most significant markers of his style. Janáček took these stylistic principles much farther in his vocal writing than Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky was a Russian composer, one of the group known as 'The Five'. He was an innovator of Russian music in the romantic period...

, and thus anticipates the later work of Béla Bartók

Béla Bartók

Béla Viktor János Bartók was a Hungarian composer and pianist. He is considered one of the most important composers of the 20th century and is regarded, along with Liszt, as Hungary's greatest composer...

. The stylistic basis for his later works originates in the period of 1904–1918, but Janáček composed the majority of his output – and his best known works – in the last decade of his life.

Much of Janáček's work displays great originality and individuality. It employs a vastly expanded view of tonality

Tonality

Tonality is a system of music in which specific hierarchical pitch relationships are based on a key "center", or tonic. The term tonalité originated with Alexandre-Étienne Choron and was borrowed by François-Joseph Fétis in 1840...

, uses unorthodox chord spacings and structures, and often, modality

Musical mode

In the theory of Western music since the ninth century, mode generally refers to a type of scale. This usage, still the most common in recent years, reflects a tradition dating to the middle ages, itself inspired by the theory of ancient Greek music.The word encompasses several additional...

: "there is no music without key

Key (music)

In music theory, the term key is used in many different and sometimes contradictory ways. A common use is to speak of music as being "in" a specific key, such as in the key of C major or in the key of F-sharp. Sometimes the terms "major" or "minor" are appended, as in the key of A minor or in the...

. Atonality

Atonality

Atonality in its broadest sense describes music that lacks a tonal center, or key. Atonality in this sense usually describes compositions written from about 1908 to the present day where a hierarchy of pitches focusing on a single, central tone is not used, and the notes of the chromatic scale...

abolishes definite key, and thus tonal modulation

Modulation (music)

In music, modulation is most commonly the act or process of changing from one key to another. This may or may not be accompanied by a change in key signature. Modulations articulate or create the structure or form of many pieces, as well as add interest...

....Folksong knows of no atonality." Janáček features accompaniment

Accompaniment

In music, accompaniment is the art of playing along with an instrumental or vocal soloist or ensemble, often known as the lead, in a supporting manner...

figures and patterns, with (according to Jim Samson) "the on-going movement of his music...similarly achieved by unorthodox means; often a discourse of short, 'unfinished' phrases

Phrase (music)

In music and music theory, phrase and phrasing are concepts and practices related to grouping consecutive melodic notes, both in their composition and performance...

comprising constant repetitions of short motifs

Motif (music)

In music, a motif or motive is a short musical idea, a salient recurring figure, musical fragment or succession of notes that has some special importance in or is characteristic of a composition....

which gather momentum in a cumulative manner." Janáček named these motifs "sčasovka" in his theoretical works. "Sčasovka" has no strict English equivalent, but John Tyrrell

John Tyrrell

John Tyrrell may refer to:* John Tyrell, 15th century English knight, Speaker of House of Commons* John Tyrrell , English second Admiral of the East Indies...

, a leading specialist on Janáček's music, describes it as "a little flash of time, almost a kind of musical capsule, which Janáček often used in slow music as tiny swift motifs with remarkably characteristic rhythms that are supposed to pepper the musical flow." Janáček's use of these repeated motifs demonstrates a remote similarity to minimalist composers (Sir Charles Mackerras called Janáček "the first minimalist composer").

Legacy

Janáček belongs to a wave of 20th century composers who sought greater realism and greater connection with everyday life, combined with a more all-encompassing use of musical resources. His operas in particular demonstrate the use of "speech"-derived melodic lines, folk and traditional material, and complex modal musical argument. Janáček's works are still regularly performed around the world, and are generally considered popular with audiences. He would also inspire later composers in his homeland, as well as music theorists, among them Jaroslav VolekJaroslav Volek

Jaroslav Volek was a Czech musicologist, semiotician who developed a theory of modal music. His theory included ideas of poly-modality and alteration of notes that he called "flex," which result in what he called the system of flexible diatonics. He applied this theory to the work of Béla Bartók...

, to place modal development alongside harmony

Harmony

In music, harmony is the use of simultaneous pitches , or chords. The study of harmony involves chords and their construction and chord progressions and the principles of connection that govern them. Harmony is often said to refer to the "vertical" aspect of music, as distinguished from melodic...

of importance in music.

Jenufa

Jenůfa is an opera in three acts by Leoš Janáček to a Czech libretto by the composer, based on the play Její pastorkyňa by Gabriela Preissová. It was first performed at the Brno Theater, Brno, 21 January 1904...

(1904), Káťa Kabanová

Káta Kabanová

Káťa Kabanová is an opera in three acts, with music by Leoš Janáček to a libretto by Vincenc Červinka, based on The Storm, a play by Alexander Ostrovsky. The opera was also largely inspired by Janáček's love for Kamila Stösslová...

(1921), The Cunning Little Vixen

The Cunning Little Vixen

The Cunning Little Vixen is an opera by Leoš Janáček, with a libretto adapted by the composer from a serialized novella by Rudolf Těsnohlídek and Stanislav Lolek, which was first published in the newspaper Lidové noviny.-Composition history:When Janáček discovered Těsnohlídek's...

(1924), The Makropulos Affair (1926) and From the House of the Dead

From the House of the Dead

From the House of the Dead is an opera by Leoš Janáček, in three acts. The libretto was translated and adapted by the composer from the novel by Dostoyevsky...

(after a novel by Dostoyevsky

The House of the Dead (novel)

The House of the Dead is a novel published in 1861 in the journal Vremya by Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky, which portrays the life of convicts in a Siberian prison camp...

and premiered posthumously in 1930) are considered his finest works. The Australian conductor Sir Charles Mackerras

Charles Mackerras

Sir Alan Charles Maclaurin Mackerras, AC, CH, CBE was an Australian conductor. He was an authority on the operas of Janáček and Mozart, and the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan...

became very closely associated with Janáček's operas.

Janáček's chamber music, while not especially voluminous, includes works which are generally considered to be "in the standard repertory" as 20th century classics, particularly his two string quartet

String quartet

A string quartet is a musical ensemble of four string players – usually two violin players, a violist and a cellist – or a piece written to be performed by such a group...

s: Quartet No. 1, "The Kreutzer Sonata"

String Quartet No. 1 (Janácek)

Leoš Janáček’s String Quartet No. 1, "Kreutzer Sonata", was written in a very short space of time, between 13 and 28 October 1923, at a time of great creative concentration. The work was revised by the composer in the autograph from 30 October to 7 November 1923.The composition was inspired by Leo...

inspired by the Tolstoy novel

The Kreutzer Sonata

The Kreutzer Sonata is a novella by Leo Tolstoy, published in 1889 and promptly censored by the Russian authorities. The work is an argument for the ideal of sexual abstinence and an in-depth first-person description of jealous rage...

, and the Quartet No. 2, "Intimate Letters"

String Quartet No. 2 (Janácek)

Leoš Janáček's String Quartet No. 2, "Intimate Letters", was written in 1928. It has been referred to as Janáček's "manifesto on love".- Background :...

. Milan Kundera

Milan Kundera

Milan Kundera , born 1 April 1929, is a writer of Czech origin who has lived in exile in France since 1975, where he became a naturalized citizen in 1981. He is best known as the author of The Unbearable Lightness of Being, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, and The Joke. Kundera has written in...

called these compositions the peak of Janáček's output.

At the Frankfurt am Main Festival of Modern Music in 1927 Ilona Štěpánová-Kurzová

Ilona Štepánová-Kurzová

Ilona Štěpánová-Kurzová was a Czech concert pianist and piano teacher, a professor at the Prague Academy of Arts. Her students included Ivan Moravec. Ilona Štěpánová-Kurzová was the mother of pianist Pavel Štěpán.- Biography :Ilona Štěpánová-Kurzová belongs to notable representatives of the Czech...

performed the world premiere of Janáček's lyrical Concertino

Concertino (Janácek)

Concertino for piano, two violins, viola, clarinet, french horn and bassoon is a composition by Czech composer Leoš Janáček.- Background :The composition was written in first months of 1925, but Janáček decided on its inception in the end of 1924. He was impressed by the skills of pianist Jan...

for piano, two violins, viola, clarinet, French horn and bassoon; the Czech premiere took place in Brno

Brno

Brno by population and area is the second largest city in the Czech Republic, the largest Moravian city, and the historical capital city of the Margraviate of Moravia. Brno is the administrative centre of the South Moravian Region where it forms a separate district Brno-City District...

on 16 February 1926. A comparable chamber work for an even more unusual set of instruments, the Capriccio

Capriccio (Janácek)

The Capriccio for Piano Left-Hand and Chamber Ensemble is a composition by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček. The work was written in the autumn of 1926 and is remarkable not just in the context of Janáček's output, but it also occupies an exceptional position in the literature written for piano...

for piano left hand, flute, two trumpets, three trombones and tenor tuba, was written for pianist Otakar Hollmann

Otakar Hollmann

Otakar Hollmann was a Czech pianist who was notable in the repertoire for left-handed pianists. Although little known now, he was considered second only to Paul Wittgenstein in the promotion of the left-hand repertoire. He commissioned works for the left hand from a number of composers, most...

, who lost the use of his right hand during World War I. After its premiere in Prague on 2 March 1928, it gained considerable acclaim in the musical world.

Other well known pieces by Janáček include the Sinfonietta

Sinfonietta (Janácek)

The Sinfonietta is a very expressive and festive, late work for large orchestra by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček...

, the Glagolitic Mass

Glagolitic Mass

The Glagolitic Mass is a composition for soloists , double chorus, organ and orchestra by Leoš Janáček. The work was completed on 15 October 1926...

(the text written in Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Church Slavic was the first literary Slavic language, first developed by the 9th century Byzantine Greek missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius who were credited with standardizing the language and using it for translating the Bible and other Ancient Greek...

), and the rhapsody Taras Bulba

Taras Bulba (rhapsody)

Taras Bulba is a rhapsody for orchestra by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček. It was composed in 1918 and belongs to the most powerful of Janáček's scores. It is based on the novel by Gogol....

. These pieces and the above mentioned five late operas were all written in the last decade of Janáček's life.

Janáček established a school of composition in Brno. Among his notable pupils were Jan Kunc

Jan Kunc

Jan Kunc was a Czech composer, pedagogue and writer.- Life :He was a pupil of Czech composer Leoš Janáček in teacher's institution and organ school . He studied composition with Vítězslav Novák from 1905 to 1906...

, Václav Kaprál

Václav Kaprál

Václav Kaprál was a Czech pianist and composer.Kaprál studied composition with Leoš Janáček in the Brno Organ School and with Vítězslav Novák in Prague. Later, he studied piano interpretation with Alfred Cortot in Paris .Kaprál composed about fifty opuses, mainly solo piano, vocal, and chamber...

, Vilém Petrželka

Vilém Petrželka

Vilém Petrželka was a prominent Czech composer and conductor.Petrželka was a pupil of Leoš Janáček, Vítězslav Novák and Karel Hoffmeister...

, Jaroslav Kvapil

Jaroslav Kvapil (composer)

Jaroslav Kvapil was a Czech composer, teacher, conductor and pianist.Born in Fryšták, he studied with Josef Nešvera and worked as a chorister in Olomouc from 1902 to 1906. He then studied at the Brno School of Organists under Leoš Janáček, earning a diploma in 1909...

, Osvald Chlubna

Osvald Chlubna

Osvald Chlubna was a prominent Czech composer. Intending originally to study engineering, Chlubna switched his major and from 1914 to 1924, he studied composition with Leoš Janáček. Until 1953, he worked as a clerk. Later, he taught at the Organ School in Brno for many years. He worked in many art...

, Břetislav Bakala

Bretislav Bakala

Břetislav Bakala was a Czech conductor, pianist, and composer.Bakala was born at Fryšták, Moravia. He studied conducting at the Brno Conservatory with František Neumann, composition with Leoš Janáček at the organ school. In 1922 he continued his studies at the Master school at the Conservatory...

, and Pavel Haas

Pavel Haas

Pavel Haas was a Czech composer who was murdered during the Holocaust. He was an exponent of Leoš Janáček's school of composition, and also utilized elements of folk music and jazz. Although his output was not large, he is notable particularly for his song cycles and string quartets.-Pre-war:Haas...

. Most of his students neither imitated nor developed Janáček's style, which left him no direct stylistic descendants. According to Milan Kundera, Janáček developed a personal, modern style in relative isolation from contemporary modernist movements but was in close contact with developments in modern European music. His path towards the innovative "modernism" of his later years was long and solitary, and he achieved true individuation as a composer around his 50th year.

Sir Charles Mackerras, the Australian conductor who helped promote Janáček's works on the world's opera stages, described his style as "... completely new and original, different from anything else ... and impossible to pin down to any one style". According to Mackerras, Janáček's use of whole-tone scale differs from that of Debussy

Claude Debussy

Claude-Achille Debussy was a French composer. Along with Maurice Ravel, he was one of the most prominent figures working within the field of impressionist music, though he himself intensely disliked the term when applied to his compositions...

, his folk music inspiration is absolutely dissimilar from Dvořák's and Smetana's, and his characteristically complex rhythms differ from the techniques of the young Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky ; 6 April 1971) was a Russian, later naturalized French, and then naturalized American composer, pianist, and conductor....

.

The French conductor and composer Pierre Boulez

Pierre Boulez

Pierre Boulez is a French composer of contemporary classical music, a pianist, and a conductor.-Early years:Boulez was born in Montbrison, Loire, France. As a child he began piano lessons and demonstrated aptitude in both music and mathematics...

, who interpreted Janáček's operas and orchestral works, called his music surprisingly modern and fresh: "Its repetitive pulse varies through changes in rhythm, tone and direction." He described his opera From the House of the Dead as "primitive, in the best sense, but also extremely strong, like the paintings of Léger, where the rudimentary character allows a very vigorous kind of expression".

Janáček's life has featured in several films. In 1974 Eva Marie Kaňková made a short documentary Fotograf a muzika (The Photographer and the Music) about the Czech photographer Josef Sudek

Josef Sudek

Josef Sudek was a Czech photographer, best known for his photographs of Prague.Originally a bookbinder. During The First World War he was drafted into Austro-Hungarian Army. In 1915 and served on the Italian Front until he was wounded in the right arm in 1916...

and his relationship to Janáček's work. In 1983 the Brothers Quay

Brothers Quay

Stephen and Timothy Quay are American identical twin brothers better known as the Brothers Quay or Quay Brothers. They are influential stop-motion animators...

produced a stop motion

Stop motion

Stop motion is an animation technique to make a physically manipulated object appear to move on its own. The object is moved in small increments between individually photographed frames, creating the illusion of movement when the series of frames is played as a continuous sequence...

animated film, Leoš Janáček: Intimate Excursions, about Janáček's life and work, and in 1986 the Czech director Jaromil Jireš made Lev s bílou hřívou (Lion with the White Mane), which showed the amorous inspiration behind Janáček's works. In Search of Janáček

In Search of Janacek

In Search of Janáček is a documentary film about life of composer Leoš Janáček.The film, written and directed by Petr Kaňka, received Special Mention at the International Television Festival Golden Prague in 2003. It was released in 2004 to celebrate 150 years anniversary of Janáček...

is a Czech documentary directed in 2004 by Petr Kaňka, made to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Janáček's birth. An animated cartoon version of The Cunning Little Vixen

The Cunning Little Vixen

The Cunning Little Vixen is an opera by Leoš Janáček, with a libretto adapted by the composer from a serialized novella by Rudolf Těsnohlídek and Stanislav Lolek, which was first published in the newspaper Lidové noviny.-Composition history:When Janáček discovered Těsnohlídek's...

was made in 2003 by the BBC

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

, with music performed by the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

The Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin is an orchestra based in Berlin, Germany. It was founded in 1946 by American occupation forces as the RIAS-Symphonie-Orchester . It was also known as the American Sector Symphony Orchestra...

and conducted by Kent Nagano

Kent Nagano

__FORCETOC__Kent George Nagano is an American conductor and opera administrator. He is currently the music director of the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal and the Bavarian State Opera.-Biography:...

. A rearrangement of the opening of the Sinfonietta was used by the progressive rock band Emerson, Lake & Palmer

Emerson, Lake & Palmer

Emerson, Lake & Palmer, also known as ELP, are an English progressive rock supergroup. They found success in the 1970s and sold over forty million albums and headlined large stadium concerts. The band consists of Keith Emerson , Greg Lake and Carl Palmer...

for its song Knife-Edge on their debut album.

The Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra

Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra

The Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra is a noted orchestra based in Ostrava in the northeast of the Czech Republic. It is named after the famous Czech composer Leoš Janáček. The orchestra was established in 1954 and has toured all across the world...

was established in 1954. Today the 116-piece ensemble is associated with mostly contemporary music but also regularly performs works from the classical repertoire. The orchestra is resident at the House of Culture Vítkovice (Dům kultury Vítkovice) in Ostrava

Ostrava

Ostrava is the third largest city in the Czech Republic and the second largest urban agglomeration after Prague. Located close to the Polish border, it is also the administrative center of the Moravian-Silesian Region and of the Municipality with Extended Competence. Ostrava was candidate for the...

, Czech Republic. The orchestra tours extensively and has performed in Europe, the U.S., Australia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan

Taiwan

Taiwan , also known, especially in the past, as Formosa , is the largest island of the same-named island group of East Asia in the western Pacific Ocean and located off the southeastern coast of mainland China. The island forms over 99% of the current territory of the Republic of China following...

. Its current music director is Theodore Kuchar

Theodore Kuchar

Theodore Kuchar is a Ukrainian American conductor of classical music and a violist.-Biography:Kuchar was born in 1960 in New York City. He started to learn to play the violin at ten years of age, later switching to viola...

.

Criticism

Czech musicology at the beginning of the 20th century was strongly influenced by Romanticism, in particular by the styles of Wagner and Smetana. Performance practises were conservative, and actively resistant to stylistic innovation. During his lifetime, Janáček reluctantly conceded to Karel Kovařovic's instrumental rearrangement of Jenůfa, most noticeably in the finale, in which Kovařovic added a more 'festive' sound of trumpets and French horns, and doubled some instruments to support Janáček's "poor" instrumentation. The score of Jenůfa was later restored by Charles Mackerras, and is now performed according to Janáček's original intentions.Another important Czech musicologist, Zdeněk Nejedlý

Zdenek Nejedlý

Zdeněk Nejedlý was a Czech musicologist, music critic, author, and politician whose ideas dominated the cultural life of what is now the Czech Republic for most of the twentieth century...

, a great admirer of Smetana and later a communist Minister of Culture, condemned Janáček as an author who could accumulate a lot of material, but was unable to do anything with it. He called Janáček's style "unanimated", and his operatic duets "only speech melodies", without polyphonic strength. Nejedlý considered Janáček rather an amateurish composer, whose music did not conform to the style of Smetana. According to Charles Mackerras, he tried to professionally destroy Janáček. Josef Bartoš, the Czech aesthetician and music critic, called Janáček a "musical eccentric" who clung tenaciously to an imperfect, improvising style, but Bartoš appreciated some elements of Janáček's works and judged him more positively than Nejedlý.

Janáček's friend and collaborator Václav Talich

Václav Talich

Václav Talich was a Czech conductor, violinist and pedagogue.- Life :Born in Kroměříž, Moravia, he started his musical career in a student orchestra in Klatovy. From 1897 to 1903 he studied at the conservatory in Prague with Otakar Ševčík...

, former chief-conductor of the Czech Philharmonic, sometimes adjusted Janáček's scores, mainly for their instrumentation and dynamics; some critics sharply attacked him for doing so. Talich re-orchestrated Taras Bulba and the Suite from Cunning Little Vixen justifying the latter with the claim that "it was not possible to perform it in the Prague National Theatre unless it was entirely re-orchestrated". Talich's rearrangement rather emasculated the specific sounds and contrasts of Janáček's original, but was the standard version for many years. Charles Mackerras started to research Janáček's music in 1960s, and gradually restored the composer's distinctive scoring. The critical edition of Janáček's scores is published by the Czech Editio Janáček.

Inspiration

Janáček's style and thematic inspiration make use of several fundamental sources.Folklore

Janáček was deeply influenced by folklore, and by Moravian folk music in particular, but not by the pervasive, idealized 19th century romantic folklore variant. He took a realistic, descriptive and analytic approach to the material. Janáček partly composed the original piano accompaniments to more than 150 folk songs, respectful of their original function and context, and partly used folk inspiration in his own works, especially in his mature compositions. His work in this area was not stylistically imitative; instead, he developed a new and original musical aesthetic based on a deep study of the fundamentals of folk music. Through his systematic notation of folk songs as he heard them, Janáček developed an exceptional sensitivity to the melodies and rhythms of speech, from which he compiled a collection of distinctive segments he called "speech tunes". He used these "essences" of spoken language in his vocal and instrumental works. The roots of his style, marked by the lilts of human speech, emerge from the world of folk music.

Russia

Janáček's deep and lifelong affection for Russia and Russian culture represents another important element of his musical inspiration. In 1888 he attended the Prague performance of Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian: Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский ; often "Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky" in English. His names are also transliterated "Piotr" or "Petr"; "Ilitsch", "Il'ich" or "Illyich"; and "Tschaikowski", "Tschaikowsky", "Chajkovskij"...

's music, and met the older composer. Janáček profoundly admired Tchaikovsky, and particularly appreciated his highly developed musical thought in connection with the use of Russian folk motifs. Janáček's Russian inspiration is especially apparent in his later chamber, symphonic and operatic output. He closely followed developments in Russian music from his early years, and in 1896, following his first visit of Russia, he founded a Russian Circle in Brno. Janáček read Russian authors in their original language. Their literature offered him an enormous and reliable source of inspiration, though this did not blind him to the problems of Russian society. He was twenty-two years old when he wrote his first composition based on a Russian theme: a melodrama, "Death", set to Lermontov's

Mikhail Lermontov

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov , a Russian Romantic writer, poet and painter, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucasus", became the most important Russian poet after Alexander Pushkin's death in 1837. Lermontov is considered the supreme poet of Russian literature alongside Pushkin and the greatest...

poem. In his later works, he often used literary models with sharply contoured plots. In 1910 Zhukovsky's Tale of Tsar Berendei inspired him to write the Fairy Tale for Cello and Piano. He composed the rhapsody Taras Bulba (1918) to Gogol's

Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol was a Ukrainian-born Russian dramatist and novelist.Considered by his contemporaries one of the preeminent figures of the natural school of Russian literary realism, later critics have found in Gogol's work a fundamentally romantic sensibility, with strains of Surrealism...

short story, and five years later, in 1923, completed his first string quartet, inspired by Tolstoy´s

Leo Tolstoy

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy was a Russian writer who primarily wrote novels and short stories. Later in life, he also wrote plays and essays. His two most famous works, the novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina, are acknowledged as two of the greatest novels of all time and a pinnacle of realist...

Kreutzer Sonata

The Kreutzer Sonata

The Kreutzer Sonata is a novella by Leo Tolstoy, published in 1889 and promptly censored by the Russian authorities. The work is an argument for the ideal of sexual abstinence and an in-depth first-person description of jealous rage...

. Two of his later operas were based on Russian themes: Káťa Kabanová, composed in 1921 to Alexander Ostrovsky's play, The Storm: and his last work, From the House of the Dead, which transformed Dostoyevsky's vision of the world into an exciting collective drama.

Janáček always deeply admired Antonín Dvořák, to whom he dedicated some of his works. He rearranged part of Dvořák's Moravian Duets

Moravian Duets

Moravian Duets by Antonín Dvořák is a cycle of 23 Moravian folk poetry settings for two voices with piano accompaniment, composed between 1875 and 1881. The Duets, published in three volumes, Op. 20 , Op. 32 , and Op. 38 , occupy an important position among Dvořák's other works. The fifteen duets...

for mixed choir with original piano accompaniment. In the early years of the 20th century, Janáček became increasingly interested in the music of other European composers. His opera Destiny was a response to another significant and famous work in contemporary Bohemia – Louise

Louise (opera)

Louise is an opera in four acts by Gustave Charpentier to an original French libretto by the composer, with some contributions by Saint-Pol-Roux, a symbolist poet and inspiration of the surrealists....

, by the French composer Gustave Charpentier

Gustave Charpentier

Gustave Charpentier, , born in Dieuze, Moselle on 25 June 1860, died Paris, 18 February 1956) was a French composer, best known for his opera Louise.-Life and career:...

. The influence of Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini was an Italian composer whose operas, including La bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, and Turandot, are among the most frequently performed in the standard repertoire...

is apparent particularly in Janáček's later works, for example in his opera Káťa Kabanová. Although he carefully observed developments in European music, his operas remained firmly connected with Czech and Slavic themes.

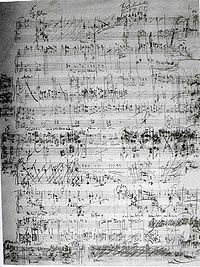

Music theorist

MusicologyJanáček created his music theory works, essays and articles over a period of fifty years, from 1877 to 1927. He wrote and edited the Hudební listy journal, and contributed to many specialist music journals, such as Cecílie, Hlídka and Dalibor. He also completed several extensive studies, as Úplná nauka o harmonii (The Complete Harmony Theory), O skladbě souzvukův a jejich spojův (On the Construction of Chords and Their Connections) and Základy hudebního sčasování (Basics of Music "sčasování"). In his essays and books, Janáček examined various musical topics, forms, melody and harmony theories, dyad and triad chords, counterpoint (or "opora", meaning "support") and devoted himself to the study of the mental composition. His theoretical works stress the Czech term "sčasování", Janáček's specific word for rhythm, which has relation to time ("čas" in Czech), and the handling of time in music composition. He distinguished several types of rhythm (sčasovka): "znící" (sounding) – meaning any rhythm, "čítací" (counting) – meaning smaller units measuring the course of rhythm; and "scelovací" (summing) – a long value comprising the length of a rhythmical unit. Janáček used the combination of their mutual action widely in his own works.

Other writing

Leoš Janáček's literary legacy represents an important illustration of his life, public work and art between 1875 and 1928. He contributed not only to music journals, but wrote essays, reports, reviews, feuilletons, articles and books. His work in this area comprises around 380 individual items. His writing changed over time, and appeared in many genres. Nevertheless, the critical and theoretical sphere remained his main area of interest.

Folk music research

Janáček came from a region characterized by its deeply rooted folk cultureFolk culture

Folk culture refers to the lifestyle of a culture. Historically, handed down through oral tradition, it demonstrates the "old ways" over novelty and relates to a sense of community. Folk culture is quite often imbued with a sense of place...

, which he explored as a young student under Pavel Křížkovský. His meeting with the folklorist and dialectologist František Bartoš

František Bartoš (folklorist)

František Bartoš was a Moravian ethnomusicologist, folklorist, folksong collector, and dialectologist. He is viewed as the successor of František Sušil, the pioneer of Moravian ethnomusicology...

(1837–1906) was decisive in his own development as a folklorist and composer, and led to their collaborative and systematic collections of folk songs. Janáček became an important collector in his own right, especially of Lachian

Lach dialects

The Lach dialects , are a group of dialects of Silesian language. They represent a hybrid or mix of the West Slavic languages.The Lach dialects are spoken in parts of Czech Silesia, the Hlučín region, and northeastern Moravia, as well as in some adjacent villages in Poland...

, Moravian Slovakia

Moravian Slovakia

Moravian Slovakia or Slovácko is a cultural region in the southeastern part of the Czech Republic on the border with Slovakia and Austria, known for its characteristic folklore, music, wine, costumes and traditions...

n, Moravian Wallachia

Moravian Wallachia

Moravian Wallachia is a mountainous region located in the easternmost part of Moravia, Czech Republic, near the Slovakian border. The name Wallachia was formerly applied to all the highlands of Moravia and neighboring Silesia, although in the nineteenth century a smaller area came to be defined...

n and Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

n songs. From 1879, his collections included transcribed speech intonations. He was one of the organizers of the Czech-Slavic Folklore Exhibition, an important event in Czech culture at the end of 19th century. From 1905 he was President of the newly instituted Working Committee for Czech National Folksong in Moravia and Silesia, a branch of the Austrian institute Das Volkslied in Österreich (Folksong in Austria), which was established in 1902 by the Viennese publishing house Universal Edition

Universal Edition

Universal Edition is a classical music publishing firm. Founded in 1901 in Vienna, and originally intended to provide the core classical works and educational works to the Austrian market...

. Janáček was a pioneer and propagator of ethnographic

Ethnography

Ethnography is a qualitative method aimed to learn and understand cultural phenomena which reflect the knowledge and system of meanings guiding the life of a cultural group...

photography in Moravia and Silesia. In October 1909 he acquired an Edison

Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices that greatly influenced life around the world, including the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and a long-lasting, practical electric light bulb. In addition, he created the world’s first industrial...

phonograph and became one of the first to use phonographic recording as a folklore research tool. Several of these recording sessions have been preserved, and were reissued in 1998.

Operas

Leoš Janáček counts among the first opera composers who used prose for his libretti, not verse. He even wrote his own libretti to his last three operas. His libretti were translated into German by Max BrodMax Brod

Max Brod was a German-speaking Czech Jewish, later Israeli, author, composer, and journalist. Although he was a prolific writer in his own right, he is most famous as the friend and biographer of Franz Kafka...

.

- ŠárkaŠárka (Janácek)Šárka is an opera in three acts by Leoš Janáček to a Czech libretto by Julius Zeyer, based on Bohemian legends of Šárka in Dalimil’s Chronicle...

, libretto by Julius ZeyerJulius ZeyerJulius Zeyer was a Czech prose writer, poet, and playwright.Zeyer was born into a father of German-French nobility, and mother of Jewish family, and learned the Czech language from his nanny. He was expected to take over the family's factory but instead decided to learn carpentering...

(1887) - Počátek RománuPocátek RománuThe Beginning of a Romance is an opera by Leoš Janáček to a Czech libretto by Jaroslav Tichý after a short story by Gabriela Preissová, itself suggested by a painting by Jaroslav Věšín...

, "The Beginning of a Romance", libretto by Jaroslav Tichý after Gabriela PreissováGabriela PreissováGabriela Preissová, née Gabriela Sekerová, sometimes used pen name Matylda Dumontová , was a Czech writer and playwright. Her play Její pastorkyňa was the basis for the opera Jenůfa by Leoš Janáček...

(1894) - Její pastorkyňaJenufaJenůfa is an opera in three acts by Leoš Janáček to a Czech libretto by the composer, based on the play Její pastorkyňa by Gabriela Preissová. It was first performed at the Brno Theater, Brno, 21 January 1904...

, "Her Stepdaughter", known in the English-speaking world as Jenůfa, libretto by the composer after Gabriela Preissová (1904) - OsudDestiny (Janácek)Destiny is an opera in three acts by Leoš Janáček to a Czech libretto by the composer and Fedora Bartošová. Janáček began the work in 1903 and completed it in 1907. The inspiration for the opera came from a visit by Janáček in the summer of 1903, after the death of his daughter Olga, to the spa...

, "Destiny", libretto by Fedora Bartošová (1904) - Výlety páně BroučkovyThe Excursions of Mr. Broucek on the Moon and in the 15th CenturyThe Excursions of Mr. Brouček to the Moon and to the 15th Century is the complete title of Leoš Janáček’s fifth opera, based on two Svatopluk Čech novels, Pravý výlet pana Broučka do Měsíce and Nový epochální výlet pana Broučka, tentokráte do XV...

, "The Excursions of Mr. Broucek", libretto by Viktor DykViktor DykViktor Dyk was a well-known Czech poet, prose writer, playwright, politician and political writer....

and František Sarafínský Procházka (1920) - Káťa KabanováKáta KabanováKáťa Kabanová is an opera in three acts, with music by Leoš Janáček to a libretto by Vincenc Červinka, based on The Storm, a play by Alexander Ostrovsky. The opera was also largely inspired by Janáček's love for Kamila Stösslová...

, "Katya Kabanova", libretto by Vincenc Cervinka, after Alexander Ostrovsky's The Storm (1921) - Příhody lišky BystrouškyThe Cunning Little VixenThe Cunning Little Vixen is an opera by Leoš Janáček, with a libretto adapted by the composer from a serialized novella by Rudolf Těsnohlídek and Stanislav Lolek, which was first published in the newspaper Lidové noviny.-Composition history:When Janáček discovered Těsnohlídek's...

, "The Cunning Little Vixen", libretto by the composer (1924) - Věc Makropulos, "The Makropoulos Affair", libretto by the composer, after Karel ČapekKarel CapekKarel Čapek was Czech writer of the 20th century.-Biography:Born in 1890 in the Bohemian mountain village of Malé Svatoňovice to an overbearing, emotional mother and a distant yet adored father, Čapek was the youngest of three siblings...

(1926) - Z mrtvého domuFrom the House of the DeadFrom the House of the Dead is an opera by Leoš Janáček, in three acts. The libretto was translated and adapted by the composer from the novel by Dostoyevsky...

, "From the House of the Dead", libretto by the composer, after Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1927)

Orchestral

The early orchestral works are influenced by Romantic style, and especially by orchestral works of Dvořák. In his later works, created after 1900, Janáček found his own, original expression.- Suite for Strings

- Lachian DancesLachian DancesThe Lachian Dances was the first mature work by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček. Originally titled Wallachian Dances after the Moravian Wallachia region, Janáček later changed the title when the region's name also changed, since it reflects folk songs from that specific area.- Background :Janáček...

- Moravian Dances

- Suite for Orchestra (1891)

- Jealousy , overture for Orchestra (1894)

- The Fiddler's Child (1912–14)

- Taras BulbaTaras Bulba (rhapsody)Taras Bulba is a rhapsody for orchestra by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček. It was composed in 1918 and belongs to the most powerful of Janáček's scores. It is based on the novel by Gogol....

(1918) - Dunaj (Danube) Symphony (1923–25)

- SinfoniettaSinfonietta (Janácek)The Sinfonietta is a very expressive and festive, late work for large orchestra by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček...

(1926) - The Wandering of a Little SoulThe Wandering of a Little SoulThe Wandering of a Little Soul is a violin concerto by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček. The work is also known in English as "Pilgrimage of a Little Soul", "Pilgrimage of a Dear Soul" or simply as "Pilgrimage of the Soul"...

(violin concerto), (1926–27)

Vocal and choral

Janáček's choral works, known particularly in the Czech Republic, are considered extremely complicated. He wrote several choruses to the words of Czech poet Petr BezručPetr Bezruc

Petr Bezruč was the pseudonym of Vladimír Vašek , a Czech poet and short story writer who was associated with the region of Austrian Silesia.Bezruč was born in Opava and died in Olomouc.- Works :Poetry...

.

- Lord, have mercy (1896)

- AmarusAmarusAmarus is a cantata composed by Czech composer Leoš Janáček, consisting of five movements. It was completed in 1897, having been started after Janáček's visit to Russia the previous summer....

(1897) - Otče náš (The Lord's Prayer. 1901. 5-movement work for tenor solo, chorus, harp, and organ.)

- Elegy on the Death of Daughter OlgaElegy on the Death of Daughter OlgaElegy on the Death of Daughter Olga, JW 4/30 is a cantata for tenor solo, mixed choir and pianoforte, written by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček in 1903. It was written to commemorate the death of composer's daughter, Olga Janáčková...

(1903) - Kantor Halfar (Teacher Halfar) (1906)

- Maryčka Magdónova (1908)

- Sedmdesát tisíc (Seventy Thousand) (1909)

- The Eternal Gospel (1914)

- The Diary of One Who DisappearedThe Diary of One Who DisappearedThe Diary of One Who Disappeared is a song cycle for tenor, alto, three female voices and piano, written by Czech composer Leoš Janáček.- Background :...

(1919) - The Wandering MadmanThe Wandering MadmanThe Wandering Madman is a choral composition for soprano, tenor, baritone and male chorus, written in 1922 by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček to the words of a poem by Rabindranath Tagore. It was inspired by Tagore's 1921 lecture in Czechoslovakia...

(1922) - Glagolitic MassGlagolitic MassThe Glagolitic Mass is a composition for soloists , double chorus, organ and orchestra by Leoš Janáček. The work was completed on 15 October 1926...

(1926)

Chamber and instrumental

His string quartets became a standard repertoire of 20th century classical music, other notable chamber works are often written with unusual instrumentation.- Pohádka (Fairy Tale), for cello and pianoPohádka (Janáček)Pohádka is a chamber composition for cello and piano by Czech composer Leoš Janáček....

(1910) - Violin SonataViolin Sonata (Janácek)Violin Sonata for violin and piano is a work of the Czech composer Leoš Janáček . It was written in the summer of 1914, but it was not Janáček’s first attempt to create such a composition. He resolved to compose violin sonata already as a student at the conservatoire in Leipzig in 1880, and later...

(1914) - String Quartet No. 1, Kreutzer SonataString Quartet No. 1 (Janácek)Leoš Janáček’s String Quartet No. 1, "Kreutzer Sonata", was written in a very short space of time, between 13 and 28 October 1923, at a time of great creative concentration. The work was revised by the composer in the autograph from 30 October to 7 November 1923.The composition was inspired by Leo...

(1923) - YouthYouth (wind sextet)The woodwind sextet Youth , is a chamber composition by Czech composer Leoš Janáček. It was composed for flute, oboe, clarinet, French horn, bassoon and bass clarinet.- Background :...

(1924), wind sextet - Concertino for piano and chamber ensembleConcertino (Janácek)Concertino for piano, two violins, viola, clarinet, french horn and bassoon is a composition by Czech composer Leoš Janáček.- Background :The composition was written in first months of 1925, but Janáček decided on its inception in the end of 1924. He was impressed by the skills of pianist Jan...

(1925) - Capriccio for piano (left hand) and wind ensembleCapriccio (Janácek)The Capriccio for Piano Left-Hand and Chamber Ensemble is a composition by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček. The work was written in the autumn of 1926 and is remarkable not just in the context of Janáček's output, but it also occupies an exceptional position in the literature written for piano...

(1926) - String Quartet No. 2, Intimate LettersString Quartet No. 2 (Janácek)Leoš Janáček's String Quartet No. 2, "Intimate Letters", was written in 1928. It has been referred to as Janáček's "manifesto on love".- Background :...

(1928)

Piano

Janáček composed his major piano works in a relatively short period of twelve years, from 1901 to 1912. His early Thema con variazioni (subtitled Zdenka's variations) is a student work composed to the styles of famous composers.- 1. X. 19051. X. 19051. X. 1905, also known as Piano Sonata 1.X.1905, is a two-movement piano composition which Leoš Janáček composed in 1905...

(Piano Sonata) (1905) - On an Overgrown PathOn an Overgrown PathOn an Overgrown Path is a cycle of thirteen piano pieces written by Leoš Janáček and organized into two volumes.- Background :...