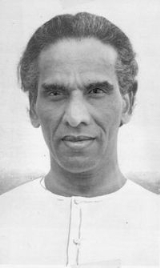

Krishna Menon

Encyclopedia

Vengalil Krishnan Krishna Menon (Malayalam: വി. കെ. കൃഷ്ണമേനോന്, Hindi: वि. के. कृष्ण मेनोन्) (3 May 1896 – 6 October 1974), commonly referred to as Krishna Menon, was an India

n nationalist, diplomat and statesman, described as the second most powerful man in India by Time Magazine and others, after his ally and intimate friend, Jawaharlal Nehru

.

Described as "vitriolic, intolerant, impatient, and exigent – yes, but generous, sensitive, considerate, a great teacher too, and a great man" by Lord Listowell

, the last British secretary of state for India, Menon was an influential and controversial figure on the world scene, and the architect of the Third Bloc

foreign policy of non-alignment. He headed India's diplomatic missions to both the United Kingdom

and United Nations

, and was repeatedly elected to both houses of the Indian Parliament from multiple constituencies, serving as Defence Minister of India

from 1957 to 1962.

Menon cofounded Penguin Books

in 1935 with Sir Allen Lane, and also created the Sainik School

s. He is the first Malayalee to have won the Padma Vibhushan

.

in Kozhikkode, Kerala

, in the Vengalil family of British Malabar

. His father Vakil [Adv] Komathu Krishna Kurup, Ayancheri

, Vatakara

, the son of Orlathiri Udayavarma Raja of Kadathanadu

and Komath Sreedevi Kettilamma Kurup, was a wealthy and influential lawyer. His mother was the granddaughter of Raman Menon who had been the Dewan

of Travancore

between 1815 and 1817, serving Gowri Parvati Bayi. Menon had his early education in Thalassery

. In 1918 he graduated from Presidency College, Chennai

, with a B.A. in History and Economics.

While studying in the Madras Law College, he became involved in Theosophy

and was actively associated with Annie Besant

and the Home Rule Movement

. He was a leading member of the 'Brothers of Service', founded by Annie Besant who spotted his gifts and helped him travel to England

in 1924.

and University College, London, where Harold Laski

described him as the best student he had ever had. In 1930 Menon was awarded an M.A. in Psychology with First Class Honours from University College, London, for a thesis entitled "An Experimental Study of the Mental Processes Involved in Reasoning", and in 1934 he was awarded an M.Sc. in Political Science with First Class Honours from the London School of Economics, for a thesis entitled "English Political Thought in the Seventeenth Century", becoming a barrister at law in the Middle Temple

shortly thereafter.

, as well as such political and intellectual figures as Bertrand Russell

, J.B.S. Haldane, Michael Foot

, Aneurin Bevan

, and E.M. Forster, whose A Passage to India

he secured the publication of, according to Shashi Tharoor

. Menon's legendary relationship with Nehru would later be analogized by Sir Isaiah Berlin as like that of Ezra Pound

and T.S. Eliot.

he was elected borough councillor of St. Pancras

, London. St. Pancras later conferred on him the Freedom of the Borough, the only other person so honoured being Bernard Shaw

. In 1932 he inspired a fact-finding delegation headed by Labour MP Ellen Wilkinson

to visit India

, and edited its report entitled 'Conditions In India', obtaining a preface from his friend Betrand Russell. Menon also worked assiduously to ensure that Nehru would succeed Mahatma Gandhi

as the moral leader and executive of the Indian independence movement

, and to clear the way for Nehru's eventual accession as the first Prime Minister

of an independent India. As Secretary, he built the India League into the most influential Indian lobby in the British Parliament, and actively turned British popular sentiment towards the cause of Indian independence.

The origins of what would become the policy of non-alignment were evident in Menon's personal sympathies even in England, where he simultaneously condemned both the British Empire

and Nazi Germany

, although he did march several times in anti-Nazi demonstrations. When asked whether India would prefer to be ruled by the British or the Nazis, Menon famously replied that "(one) might as well ask a fish if it prefers to be fried in butter or margarine".

, a post in which he remained until 1952. Menon's intense distrust of the West extended to the United Kingdom

itself, and his frequent thwarting of British political maneuvers eventually led MI5

to deem him a "serious menace to security". From 1929 onwards Menon had been kept under surveillance, which only intensified following Menon's 1946 meeting in Paris with Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

, and Indian independence. In 2007, hundreds of pages of MI5 files documenting their coverage of Menon were released, including transcripts of phone conversations and intercepted correspondences with other statesmen and Nehru humself.

, a position he would hold until 1962. He earned a reputation for brilliance in the United Nations

, frequently engineering elegant solutions to complex international political issues, including a peace plan for Korea

, a ceasefire in Indo-China, the deadlocked disarmament talks, and the French

withdrawal from the United Nations over Algeria

. During this period, Menon pioneered a novel foreign policy for India, which he dubbed the non-alignment

in 1952, charting a third course between the USA and USSR. Menon was particularly critical of the United States, and frequently expressed sympathies with Soviet policies, earning the ire of many Indians by voting against a UN resolution calling for the USSR to withdraw troops from Hungary

, although he reversed his stance three weeks later under pressure from New Delhi

.

to the United Nations

, which earned him the enmity of many American

statesmen, including Senator William F. Knowland

. In 1955, Menon intervened in the case of several American airmen who had been held by China, meeting with Chinese premier Zhou En-Lai before flying to Washington to confer with and counsel American President Dwight Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles

, at the request of British Prime Minister Anthony Eden

.

before the latter's death, meeting him on the 17th of February during an executive visit to the Soviet Union

.

, with whom he had previously collaborated in the India League.

plan for resolution, in which Egypt would be allowed to retain control of the Suez Canal. Menon's proposal was initially estimated by US diplomats to have more support than the Dulles plan, and was widely viewed as an attempt to hybridize the Dulles plan with Egypt's claims. Ultimately, the Dulles plan passed, with Menon voting against, alongside Russia

, Indonesia

, and Sri Lanka

. Menon, however, markedly softened his opposition in the final hours, leaving only Soviet Foreign Minister Dimitri Shepilov in absolute contraposition.

’s stand on Kashmir

; to date, the speech is the longest ever delivered in the United Nations Security Council

, covering five hours of the 762nd meeting on the 23 of January, and two hours and forty-eight minutes on the 14th, reportedly concluding with Menon's collapse on the Security Council floor. During the filibuster, Nehru moved swiftly and successfully to consolidate Indian power in Kashmir. Menon's passionate defense of Indian sovereignty in Kashmir enlarged his base of support in India, and led to the Indian press temporarily dubbing him the 'Hero of Kashmir'.

in 1953. On February 3, 1956, he joined the Union Cabinet as Minister without Portfolio.

In 1957, Menon sought a seat in the Lok Sabha

, contesting a constituency from North Bombay. Widely viewed as a hero for his defense of India's sovereignty in Kashmir on the world stage, Menon was met with rapturous receptions on the campaign trail, and ultimately won in a landslide.

Menon also, in the face of intense opposition, began the creation of a domestic military industrial complex to supply the Indian armed forces with weaponry and provisions. Although Menon's oversight of the development of India's military infrastructure was initially overshadowed by India's unpreparedness in the Sino-Indian War

, later analysis and scholarship has increasingly focused on the importance of Menon's vision and foresight in military development, with political figures as varied as President

and Minister of Defence R. Venkataraman

and Chief Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer of the Supreme Court of India

analyzing and defending Menon's role in India's rise as a military power.

In the October 1961, Menon, the sitting Defence Minister, was challenged by the 74-year-old Acharya Kripalani, a prior president of the Indian National Congress

and close associate of the deceased Mohandas Gandhi. The race soon became the highest-profile in India, with the Sunday Standard remarking that "no political campaign in India has ever been so bitter or so remarkable for the nuances it produced". The race, which witnessed the direct intervention of Jawaharlal Nehru

, was widely viewed as of tremendous importance due to personas and influence of the two candidates, who were seen as avatars for two distinct ideologies. Having previously endorsed Menon's foreign policies, Kripalani relentlessly attacked Menon's persona, seeking to avoid direct confrontation with the prestige of Nehru and the Congress Party.

With the race looming, Menon aggressively addressed the issue of Indian sovereignty over the Portuguese colony of Goa

, in a partial reprise of his earlier defense of Indian Kashmir

. In New York, Menon met US Ambassador and twotime presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson behind closed doors, before meeting with President John F. Kennedy

, who had expressed his reservations about Menon's anti-imperialism during the state visit of Jawaharlal Nehru

. Menon lectured Kennedy on the importance of US-Soviet compromise, before returning to India. On 17 December 1961, Menon and the Indian Army overran Goa, leading to widespread western condemnation.In his typical style, Menon dismissed the admonishments of Kennedy and Stevenson as 'vestige(s) of Western imperialism'. Menon's spearheading of the Indian annexation of Goa

had subtle ramifications throughout Asia, as in the case of Indonesian president Sukarno

, who refrained from invading the Portuguese colony of East Timor

partially from fear of being compared to Menon. The invasion also spawned a complex mass of legal issues relating to differences between eastern and western interpretations of United Nations

law and jurisdiction.

Ultimately, Menon won in a landslide, nearly doubling the vote total of Kripalani, and winning outright majorities in all six of North Bombay's districts. The electoral results established Menon as second only to Nehru himself in Indian politics.

In 1962, China invaded India, leading to the brief Sino-Indian War

, and a temporary reversal in India's non-aligned foreign policy. A chagrined Menon, widely blamed for India's lack of military readiness, tendered his resignation as minister of defence.

constituency of Midnapore, running as an independent in a by-election, and defeating his Congress rival by a margin of 106,767 votes in the May of that year.

.

A complex man, Menon dressed expensively in bespoke Savile Row

suits, while maintaining an otherwise ascetic lifestyle, abstaining from tobacco, alcohol, and meat.

Menon was widely reviled by Western statesmen who loathed his arrogance, outspokenness, and fiercely anti-Western stances. Outwardly courteous, American President Dwight Eisenhower considered Menon a "menace... governed by ambition to prove himself the master international manipulator and politician of the age". Western publications routinely referred to him as "India's Rasputin" or "Nehru's Evil Genius.

remarked that "a volcano is extinct".

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ayancheri_Thazhe_Komath_Sri_Durja_Temple_,Vatakara_,Khozhicode_Dt.pdf

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

n nationalist, diplomat and statesman, described as the second most powerful man in India by Time Magazine and others, after his ally and intimate friend, Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru , often referred to with the epithet of Panditji, was an Indian statesman who became the first Prime Minister of independent India and became noted for his “neutralist” policies in foreign affairs. He was also one of the principal leaders of India’s independence movement in the...

.

Described as "vitriolic, intolerant, impatient, and exigent – yes, but generous, sensitive, considerate, a great teacher too, and a great man" by Lord Listowell

William Hare, 5th Earl of Listowel

William Francis Hare, 5th Earl of Listowel GCMG, PC , styled Viscount Ennismore between 1924 and 1931, was a British peer and Labour politician...

, the last British secretary of state for India, Menon was an influential and controversial figure on the world scene, and the architect of the Third Bloc

Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either capitalism and NATO , or communism and the Soviet Union...

foreign policy of non-alignment. He headed India's diplomatic missions to both the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

, and was repeatedly elected to both houses of the Indian Parliament from multiple constituencies, serving as Defence Minister of India

Defence Minister of India

The Ministry of Defence is India's federal department allocated the largest level of budgetary resources and charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government relating directly to national security and the Indian armed forces.The Indian Armed Forces ; the...

from 1957 to 1962.

Menon cofounded Penguin Books

Penguin Books

Penguin Books is a publisher founded in 1935 by Sir Allen Lane and V.K. Krishna Menon. Penguin revolutionised publishing in the 1930s through its high quality, inexpensive paperbacks, sold through Woolworths and other high street stores for sixpence. Penguin's success demonstrated that large...

in 1935 with Sir Allen Lane, and also created the Sainik School

Sainik School

The Sainik Schools are a system of schools in India established and managed by the Sainik Schools Society. They were conceived in 1961 by V. K. Krishna Menon, the then Defence Minister of India, to rectify the regional and class imbalance amongst the Officer cadre of the Indian Military, and to...

s. He is the first Malayalee to have won the Padma Vibhushan

Padma Vibhushan

The Padma Vibhushan is the second highest civilian award in the Republic of India. It consists of a medal and a citation and is awarded by the President of India. It was established on 2 January 1954. It ranks behind the Bharat Ratna and comes before the Padma Bhushan...

.

Early life and education

Menon was born at PanniyankaraPanniyankara

Panniyankara has its origin in the 18th century. The main features are police station, Sathram Bus Stop and southern Railway. It is situated in Calicut district in Kerala, India. Earlier there was a palace named as Kavalapparakottaram , now demolished and the Panniankara Telephone exchange was...

in Kozhikkode, Kerala

Kerala

or Keralam is an Indian state located on the Malabar coast of south-west India. It was created on 1 November 1956 by the States Reorganisation Act by combining various Malayalam speaking regions....

, in the Vengalil family of British Malabar

Malabar District

Malabar District was an administrative district of Madras Presidency in British India and independent India's Madras State. The British district included the present-day districts of Kannur, Kozhikode, Wayanad, Malappuram, Palakkad , and Chavakad Taluk of Thrissur District in the northern part of...

. His father Vakil [Adv] Komathu Krishna Kurup, Ayancheri

Ayancheri

Ayancheri is a village in Kozhikode district in the state of Kerala, India.-Demographics: India census, Ayancheri had a population of 25446 with 12611 males and 12835 females....

, Vatakara

Vatakara

Vatakara is a coastal Municipality in Kozhikode district of Kerala, a South Indian state, spread over an area of 23.33 km2. It is the headquarters of Vatakara taluk. This place is erstwhile Kadathanadu and was part of North Malabar province of Malabar District in Madras State during British...

, the son of Orlathiri Udayavarma Raja of Kadathanadu

Kadathanadu

Kadathanadu was a former Nair Hindu feudatory city-state in present day Kerala state, South India, on the Malabar Coast famed for its anthology of heroic songs, folklores and ballads and for Kalarippayattu.-Geographical location:Geographically, Kadathanadu is part of North Malabar...

and Komath Sreedevi Kettilamma Kurup, was a wealthy and influential lawyer. His mother was the granddaughter of Raman Menon who had been the Dewan

Dewan

The originally Persian title of dewan has, at various points in Islamic history, designated various differing though similar functions.-Etymology:...

of Travancore

Travancore

Kingdom of Travancore was a former Hindu feudal kingdom and Indian Princely State with its capital at Padmanabhapuram or Trivandrum ruled by the Travancore Royal Family. The Kingdom of Travancore comprised most of modern day southern Kerala, Kanyakumari district, and the southernmost parts of...

between 1815 and 1817, serving Gowri Parvati Bayi. Menon had his early education in Thalassery

Thalassery

Thalassery , also known as Tellicherry, is a city on the Malabar Coast of Kerala, India. This is the second largest city of North Malabar in terms of population. The name Tellicherry is the anglicized form of Thalassery. Thalassery municipality has a population just less than 100,000. Established...

. In 1918 he graduated from Presidency College, Chennai

Presidency College, Chennai

Presidency College is an arts, law and science college in the city of Chennai in Tamil Nadu, India. Established as the Madras Preparatory School on October 15, 1840 and later, upgraded to a high school and then, graduate college, the Presidency College is one of the oldest government arts colleges...

, with a B.A. in History and Economics.

While studying in the Madras Law College, he became involved in Theosophy

Theosophy

Theosophy, in its modern presentation, is a spiritual philosophy developed since the late 19th century. Its major themes were originally described mainly by Helena Blavatsky , co-founder of the Theosophical Society...

and was actively associated with Annie Besant

Annie Besant

Annie Besant was a prominent British Theosophist, women's rights activist, writer and orator and supporter of Irish and Indian self rule.She was married at 19 to Frank Besant but separated from him over religious differences. She then became a prominent speaker for the National Secular Society ...

and the Home Rule Movement

Home Rule Movement

The All India Home Rule League was a national political organization founded in 1916 to lead the national demand for self-government, termed Home Rule, and to obtain the status of a Dominion within the British Empire as enjoyed by Australia, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and Newfoundland at the...

. He was a leading member of the 'Brothers of Service', founded by Annie Besant who spotted his gifts and helped him travel to England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

in 1924.

Life and activities in England

In London, Menon pursued further education at the London School of EconomicsLondon School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science is a public research university specialised in the social sciences located in London, United Kingdom, and a constituent college of the federal University of London...

and University College, London, where Harold Laski

Harold Laski

Harold Joseph Laski was a British Marxist, political theorist, economist, author, and lecturer, who served as the chairman of the Labour Party during 1945-1946, and was a professor at the LSE from 1926 to 1950....

described him as the best student he had ever had. In 1930 Menon was awarded an M.A. in Psychology with First Class Honours from University College, London, for a thesis entitled "An Experimental Study of the Mental Processes Involved in Reasoning", and in 1934 he was awarded an M.Sc. in Political Science with First Class Honours from the London School of Economics, for a thesis entitled "English Political Thought in the Seventeenth Century", becoming a barrister at law in the Middle Temple

Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers; the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's Inn and Lincoln's Inn...

shortly thereafter.

India League and the Independence Movement

During these years, Menon became a passionate proponent of India's freedom, working as a journalist and and as secretary of the India League from 1929 to 1947, and a close friend of fellow Indian nationalist leader and future Prime Minister Jawaharlal NehruJawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru , often referred to with the epithet of Panditji, was an Indian statesman who became the first Prime Minister of independent India and became noted for his “neutralist” policies in foreign affairs. He was also one of the principal leaders of India’s independence movement in the...

, as well as such political and intellectual figures as Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, and social critic. At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these things...

, J.B.S. Haldane, Michael Foot

Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot, FRSL, PC was a British Labour Party politician, journalist and author, who was a Member of Parliament from 1945 to 1955 and from 1960 until 1992...

, Aneurin Bevan

Aneurin Bevan

Aneurin "Nye" Bevan was a British Labour Party politician who was the Deputy Leader of the Labour Party from 1959 until his death in 1960. The son of a coal miner, Bevan was a lifelong champion of social justice and the rights of working people...

, and E.M. Forster, whose A Passage to India

A Passage to India

A Passage to India is a novel by E. M. Forster set against the backdrop of the British Raj and the Indian independence movement in the 1920s. It was selected as one of the 100 great works of English literature by the Modern Library and won the 1924 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction. Time...

he secured the publication of, according to Shashi Tharoor

Shashi Tharoor

Shashi Tharoor is an Indian politician and a Member of Parliament from the Thiruvananthapuram constituency in Kerala...

. Menon's legendary relationship with Nehru would later be analogized by Sir Isaiah Berlin as like that of Ezra Pound

Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound was an American expatriate poet and critic and a major figure in the early modernist movement in poetry...

and T.S. Eliot.

Founding of Penguin and Pelican Books

During the 1930s he worked as an editor for Bodley Head and Twentieth Century Library, and in 1934 cofounded Penguin and Pelican Books with colleague Sir Allen Lane. In 1934 he was admitted to the English bar, and after joining the Labour PartyLabour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

he was elected borough councillor of St. Pancras

St Pancras, London

St Pancras is an area of London. For many centuries the name has been used for various officially-designated areas, but now is used informally and rarely having been largely superseded by several other names for overlapping districts.-Ancient parish:...

, London. St. Pancras later conferred on him the Freedom of the Borough, the only other person so honoured being Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60...

. In 1932 he inspired a fact-finding delegation headed by Labour MP Ellen Wilkinson

Ellen Wilkinson

Ellen Cicely Wilkinson was the Labour Member of Parliament for Middlesbrough and later for Jarrow on Tyneside. She was one of the first women in Britain to be elected as a Member of Parliament .- History :...

to visit India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

, and edited its report entitled 'Conditions In India', obtaining a preface from his friend Betrand Russell. Menon also worked assiduously to ensure that Nehru would succeed Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi , pronounced . 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was the pre-eminent political and ideological leader of India during the Indian independence movement...

as the moral leader and executive of the Indian independence movement

Indian independence movement

The term Indian independence movement encompasses a wide area of political organisations, philosophies, and movements which had the common aim of ending first British East India Company rule, and then British imperial authority, in parts of South Asia...

, and to clear the way for Nehru's eventual accession as the first Prime Minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

of an independent India. As Secretary, he built the India League into the most influential Indian lobby in the British Parliament, and actively turned British popular sentiment towards the cause of Indian independence.

The origins of what would become the policy of non-alignment were evident in Menon's personal sympathies even in England, where he simultaneously condemned both the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

and Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

, although he did march several times in anti-Nazi demonstrations. When asked whether India would prefer to be ruled by the British or the Nazis, Menon famously replied that "(one) might as well ask a fish if it prefers to be fried in butter or margarine".

High Commissioner to the United Kingdom

After India gained independence in 1947, Menon was appointed high commissioner to the United KingdomUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, a post in which he remained until 1952. Menon's intense distrust of the West extended to the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

itself, and his frequent thwarting of British political maneuvers eventually led MI5

MI5

The Security Service, commonly known as MI5 , is the United Kingdom's internal counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its core intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service focused on foreign threats, Government Communications Headquarters and the Defence...

to deem him a "serious menace to security". From 1929 onwards Menon had been kept under surveillance, which only intensified following Menon's 1946 meeting in Paris with Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

, and Indian independence. In 2007, hundreds of pages of MI5 files documenting their coverage of Menon were released, including transcripts of phone conversations and intercepted correspondences with other statesmen and Nehru humself.

Diplomacy and Non-Alignment

In 1952, Menon accepted the command of the Indian delegation to the United NationsUnited Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

, a position he would hold until 1962. He earned a reputation for brilliance in the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

, frequently engineering elegant solutions to complex international political issues, including a peace plan for Korea

Korea

Korea ) is an East Asian geographic region that is currently divided into two separate sovereign states — North Korea and South Korea. Located on the Korean Peninsula, Korea is bordered by the People's Republic of China to the northwest, Russia to the northeast, and is separated from Japan to the...

, a ceasefire in Indo-China, the deadlocked disarmament talks, and the French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

withdrawal from the United Nations over Algeria

Algeria

Algeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

. During this period, Menon pioneered a novel foreign policy for India, which he dubbed the non-alignment

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement is a group of states considering themselves not aligned formally with or against any major power bloc. As of 2011, the movement had 120 members and 17 observer countries...

in 1952, charting a third course between the USA and USSR. Menon was particularly critical of the United States, and frequently expressed sympathies with Soviet policies, earning the ire of many Indians by voting against a UN resolution calling for the USSR to withdraw troops from Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

, although he reversed his stance three weeks later under pressure from New Delhi

New Delhi

New Delhi is the capital city of India. It serves as the centre of the Government of India and the Government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi. New Delhi is situated within the metropolis of Delhi. It is one of the nine districts of Delhi Union Territory. The total area of the city is...

.

China and the United Nations

Menon also supported the admission of ChinaChina

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

to the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

, which earned him the enmity of many American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

statesmen, including Senator William F. Knowland

William F. Knowland

William Fife Knowland was a United States politician, newspaperman, and Republican Party leader. He was a U.S. Senator representing California from 1945 to 1959. He served as Senate Majority Leader from 1953-1955, and as Minority Leader from 1955-1959. He was defeated in his 1958 run for...

. In 1955, Menon intervened in the case of several American airmen who had been held by China, meeting with Chinese premier Zhou En-Lai before flying to Washington to confer with and counsel American President Dwight Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles served as U.S. Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959. He was a significant figure in the early Cold War era, advocating an aggressive stance against communism throughout the world...

, at the request of British Prime Minister Anthony Eden

Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, KG, MC, PC was a British Conservative politician, who was Prime Minister from 1955 to 1957...

.

Soviet Russia

In 1953, Menon was the last foreign official to visit Joseph StalinJoseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

before the latter's death, meeting him on the 17th of February during an executive visit to the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

.

Nuclear Disarmament

Menon was a passionate opponent of nuclear weapons, and partnered with many in his quest against their proliferation. Throughout the 1950s, Menon liased with Bertrand RussellBertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, and social critic. At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these things...

, with whom he had previously collaborated in the India League.

Suez Crisis

During the Suez crisis, Menon attempted to persuade a recalcitrant Gamal Nasser to compromise with the West, and was instrumental in moving Western powers towards an awareness that Nasser might prove willing to compromise. During the emergency conference on Suez convened in London, Menon offered a counterproposal to John Foster DullesJohn Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles served as U.S. Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959. He was a significant figure in the early Cold War era, advocating an aggressive stance against communism throughout the world...

plan for resolution, in which Egypt would be allowed to retain control of the Suez Canal. Menon's proposal was initially estimated by US diplomats to have more support than the Dulles plan, and was widely viewed as an attempt to hybridize the Dulles plan with Egypt's claims. Ultimately, the Dulles plan passed, with Menon voting against, alongside Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, Indonesia

Indonesia

Indonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

, and Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka is a country off the southern coast of the Indian subcontinent. Known until 1972 as Ceylon , Sri Lanka is an island surrounded by the Indian Ocean, the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait, and lies in the vicinity of India and the...

. Menon, however, markedly softened his opposition in the final hours, leaving only Soviet Foreign Minister Dimitri Shepilov in absolute contraposition.

Speech on Kashmir

On 23 January 1957 Menon delivered an unprecedented eight-hour speech defending IndiaIndia

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

’s stand on Kashmir

Kashmir

Kashmir is the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term Kashmir geographically denoted only the valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal mountain range...

; to date, the speech is the longest ever delivered in the United Nations Security Council

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council is one of the principal organs of the United Nations and is charged with the maintenance of international peace and security. Its powers, outlined in the United Nations Charter, include the establishment of peacekeeping operations, the establishment of...

, covering five hours of the 762nd meeting on the 23 of January, and two hours and forty-eight minutes on the 14th, reportedly concluding with Menon's collapse on the Security Council floor. During the filibuster, Nehru moved swiftly and successfully to consolidate Indian power in Kashmir. Menon's passionate defense of Indian sovereignty in Kashmir enlarged his base of support in India, and led to the Indian press temporarily dubbing him the 'Hero of Kashmir'.

Minister Without Portfolio, 1956-7

Krishna Menon became a member of the Rajya SabhaRajya Sabha

The Rajya Sabha or Council of States is the upper house of the Parliament of India. Rajya means "state," and Sabha means "assembly hall" in Sanskrit. Membership is limited to 250 members, 12 of whom are chosen by the President of India for their expertise in specific fields of art, literature,...

in 1953. On February 3, 1956, he joined the Union Cabinet as Minister without Portfolio.

In 1957, Menon sought a seat in the Lok Sabha

Lok Sabha

The Lok Sabha or House of the People is the lower house of the Parliament of India. Members of the Lok Sabha are elected by direct election under universal adult suffrage. As of 2009, there have been fifteen Lok Sabhas elected by the people of India...

, contesting a constituency from North Bombay. Widely viewed as a hero for his defense of India's sovereignty in Kashmir on the world stage, Menon was met with rapturous receptions on the campaign trail, and ultimately won in a landslide.

Minister of Defence

After his electoral victory, he was named Minister of Defence in the April of that year. Menon was a substantially more powerful and high-profile figure than his predecessors, and brought with him a degree of governmental, public, and international attention that India's military had not previously known. He upended the seniority system within the army, replacing it with a merit-based method of promotion, and extensively restructured much of India's military command system, eventually leading to the resignation of the Chief of the Army Staff, General K.S. Thimayya. Critics accused Menon of disregarding tradition in favor of personal caprice; Menon countered that he was seeking to improve the efficiency of the military.Menon also, in the face of intense opposition, began the creation of a domestic military industrial complex to supply the Indian armed forces with weaponry and provisions. Although Menon's oversight of the development of India's military infrastructure was initially overshadowed by India's unpreparedness in the Sino-Indian War

Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War , also known as the Sino-Indian Border Conflict , was a war between China and India that occurred in 1962. A disputed Himalayan border was the main pretext for war, but other issues played a role. There had been a series of violent border incidents after the 1959 Tibetan...

, later analysis and scholarship has increasingly focused on the importance of Menon's vision and foresight in military development, with political figures as varied as President

President of India

The President of India is the head of state and first citizen of India, as well as the Supreme Commander of the Indian Armed Forces. President of India is also the formal head of all the three branches of Indian Democracy - Legislature, Executive and Judiciary...

and Minister of Defence R. Venkataraman

R. Venkataraman

Ramaswamy Venkataraman was an Indian lawyer, Indian independence activist and politician who served as a Union minister and as the eighth President of India....

and Chief Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer of the Supreme Court of India

Supreme Court of India

The Supreme Court of India is the highest judicial forum and final court of appeal as established by Part V, Chapter IV of the Constitution of India...

analyzing and defending Menon's role in India's rise as a military power.

Elections in North Bombay

In the October 1961, Menon, the sitting Defence Minister, was challenged by the 74-year-old Acharya Kripalani, a prior president of the Indian National Congress

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress is one of the two major political parties in India, the other being the Bharatiya Janata Party. It is the largest and one of the oldest democratic political parties in the world. The party's modern liberal platform is largely considered center-left in the Indian...

and close associate of the deceased Mohandas Gandhi. The race soon became the highest-profile in India, with the Sunday Standard remarking that "no political campaign in India has ever been so bitter or so remarkable for the nuances it produced". The race, which witnessed the direct intervention of Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru , often referred to with the epithet of Panditji, was an Indian statesman who became the first Prime Minister of independent India and became noted for his “neutralist” policies in foreign affairs. He was also one of the principal leaders of India’s independence movement in the...

, was widely viewed as of tremendous importance due to personas and influence of the two candidates, who were seen as avatars for two distinct ideologies. Having previously endorsed Menon's foreign policies, Kripalani relentlessly attacked Menon's persona, seeking to avoid direct confrontation with the prestige of Nehru and the Congress Party.

Invasion of Goa

With the race looming, Menon aggressively addressed the issue of Indian sovereignty over the Portuguese colony of Goa

Goa

Goa , a former Portuguese colony, is India's smallest state by area and the fourth smallest by population. Located in South West India in the region known as the Konkan, it is bounded by the state of Maharashtra to the north, and by Karnataka to the east and south, while the Arabian Sea forms its...

, in a partial reprise of his earlier defense of Indian Kashmir

Kashmir

Kashmir is the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term Kashmir geographically denoted only the valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal mountain range...

. In New York, Menon met US Ambassador and twotime presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson behind closed doors, before meeting with President John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

, who had expressed his reservations about Menon's anti-imperialism during the state visit of Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru , often referred to with the epithet of Panditji, was an Indian statesman who became the first Prime Minister of independent India and became noted for his “neutralist” policies in foreign affairs. He was also one of the principal leaders of India’s independence movement in the...

. Menon lectured Kennedy on the importance of US-Soviet compromise, before returning to India. On 17 December 1961, Menon and the Indian Army overran Goa, leading to widespread western condemnation.In his typical style, Menon dismissed the admonishments of Kennedy and Stevenson as 'vestige(s) of Western imperialism'. Menon's spearheading of the Indian annexation of Goa

Goa

Goa , a former Portuguese colony, is India's smallest state by area and the fourth smallest by population. Located in South West India in the region known as the Konkan, it is bounded by the state of Maharashtra to the north, and by Karnataka to the east and south, while the Arabian Sea forms its...

had subtle ramifications throughout Asia, as in the case of Indonesian president Sukarno

Sukarno

Sukarno, born Kusno Sosrodihardjo was the first President of Indonesia.Sukarno was the leader of his country's struggle for independence from the Netherlands and was Indonesia's first President from 1945 to 1967...

, who refrained from invading the Portuguese colony of East Timor

East Timor

The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, commonly known as East Timor , is a state in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the nearby islands of Atauro and Jaco, and Oecusse, an exclave on the northwestern side of the island, within Indonesian West Timor...

partially from fear of being compared to Menon. The invasion also spawned a complex mass of legal issues relating to differences between eastern and western interpretations of United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

law and jurisdiction.

Ultimately, Menon won in a landslide, nearly doubling the vote total of Kripalani, and winning outright majorities in all six of North Bombay's districts. The electoral results established Menon as second only to Nehru himself in Indian politics.

The Sino-Indian War

In 1962, China invaded India, leading to the brief Sino-Indian War

Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War , also known as the Sino-Indian Border Conflict , was a war between China and India that occurred in 1962. A disputed Himalayan border was the main pretext for war, but other issues played a role. There had been a series of violent border incidents after the 1959 Tibetan...

, and a temporary reversal in India's non-aligned foreign policy. A chagrined Menon, widely blamed for India's lack of military readiness, tendered his resignation as minister of defence.

Election to Parliament from Midnapore

In 1969, Menon contested a seat in the Lok Sabha from the BengalBengal

Bengal is a historical and geographical region in the northeast region of the Indian Subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. Today, it is mainly divided between the sovereign land of People's Republic of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, although some regions of the previous...

constituency of Midnapore, running as an independent in a by-election, and defeating his Congress rival by a margin of 106,767 votes in the May of that year.

Election to Parliament from Trivandrum

In 1971 Menon contested and won a seat in Parliament from Trivandrum, in his homestate of KeralaKerala

or Keralam is an Indian state located on the Malabar coast of south-west India. It was created on 1 November 1956 by the States Reorganisation Act by combining various Malayalam speaking regions....

.

Personal life

Menon was an intensely controversial figure during his life, and has remained so even well after his death. Widely described as brilliant and arrogant, he was known for the sheer force of his personality.A complex man, Menon dressed expensively in bespoke Savile Row

Savile Row

Savile Row is a shopping street in Mayfair, central London, famous for its traditional men's bespoke tailoring. The term "bespoke" is understood to have originated in Savile Row when cloth for a suit was said to "be spoken for" by individual customers...

suits, while maintaining an otherwise ascetic lifestyle, abstaining from tobacco, alcohol, and meat.

Menon was widely reviled by Western statesmen who loathed his arrogance, outspokenness, and fiercely anti-Western stances. Outwardly courteous, American President Dwight Eisenhower considered Menon a "menace... governed by ambition to prove himself the master international manipulator and politician of the age". Western publications routinely referred to him as "India's Rasputin" or "Nehru's Evil Genius.

Death

Menon died at the age of 78 on October 6, 1974, whereupon Indian Prime Minister Indira GandhiIndira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhara was an Indian politician who served as the third Prime Minister of India for three consecutive terms and a fourth term . She was assassinated by Sikh extremists...

remarked that "a volcano is extinct".

Further reading

- V. K. Krishna Menon: a personal memoir by Janaki RamJanaki RamJanaki Ram is an Indian-American author who has written biographies and collections of short stories, as well as a prominent figure in Asian art auctions. She is a relative of Krishna Menon and Sir C.P. Ramaswami Iyer and a member of the powerful South Indian Vengalil family. She was a founder and...

(1997) - Vengalil Krishnan Krishna Menon

- P. N. HaksarP. N. HaksarParmeshwar Narayan Haksar was one of the earliest and most important political strategists in the political democracy of independent India. His most important role was in the political ascent of Indira Gandhi, as the Prime Minister in her own right and personal political strength, and the...

: Krishna: As I knew him - Statements by V. K. Krishna Menon at the United Nations

- T. J. S. GeorgeT. J. S. GeorgeThayil Jacob Sony George , better known as TJS George, is a writer and biographer who received a Padma Bhushan award in 2011 in the field of literature and education. The fourth of eight siblings, TJS was born in Kerala, India to Thayil Thomas Jacob, a magistrate, and Chachiamma Jacob, a housewife....

: `Krishna Menon, Jonathan Cape, 1964. - Theft of two statues of Menon from a London park

- Neglect of Krishna Menon memorial project alleged

- `Yours Krishna Menon', play on Krishna Menon by Lalit Mohan Joshi

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ayancheri_Thazhe_Komath_Sri_Durja_Temple_,Vatakara_,Khozhicode_Dt.pdf