Kolyma

Encyclopedia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

in what is commonly known as Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

but is actually part of the Russian Far East

Russian Far East

Russian Far East is a term that refers to the Russian part of the Far East, i.e., extreme east parts of Russia, between Lake Baikal in Eastern Siberia and the Pacific Ocean...

. It is bounded by the East Siberian Sea

East Siberian Sea

The East Siberian Sea is a marginal sea in the Arctic Ocean. It is located between the Arctic Cape to the north, the coast of Siberia to the south, the New Siberian Islands to the west and Cape Billings, close to Chukotka, and Wrangel Island to the east...

and the Arctic Ocean

Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean, located in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Arctic north polar region, is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceanic divisions...

in the north and the Sea of Okhotsk

Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean, lying between the Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands on the southeast, the island of Hokkaidō to the far south, the island of Sakhalin along the west, and a long stretch of eastern Siberian coast along the west and...

to the south. The extremely remote region gets its name from the Kolyma River

Kolyma River

The Kolyma River is a river in northeastern Siberia, whose basin covers parts of the Sakha Republic, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, and Magadan Oblast of Russia. Itrises in the mountains north of Okhotsk and Magadan, in the area of and...

and mountain range, parts of which were not discovered until 1926. Today the region consists roughly of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug

Chukotka Autonomous Okrug

Chukotka Autonomous Okrug , or Chukotka , is a federal subject of Russia located in the Russian Far East.Chukotka has a population of 53,824 according to the 2002 Census, and a surface area of . The principal town and the administrative center is Anadyr...

and the Magadan Oblast

Magadan Oblast

Magadan Oblast is a federal subject of Russia in the Far Eastern Federal District. Its administrative center is the city of Magadan....

.

The area, part of which is within the Arctic Circle

Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of the Earth. For Epoch 2011, it is the parallel of latitude that runs north of the Equator....

, has a subarctic climate

Subarctic climate

The subarctic climate is a climate characterized by long, usually very cold winters, and short, cool to mild summers. It is found on large landmasses, away from the moderating effects of an ocean, generally at latitudes from 50° to 70°N poleward of the humid continental climates...

with very cold winters lasting up to six months of the year. Permafrost

Permafrost

In geology, permafrost, cryotic soil or permafrost soil is soil at or below the freezing point of water for two or more years. Ice is not always present, as may be in the case of nonporous bedrock, but it frequently occurs and it may be in amounts exceeding the potential hydraulic saturation of...

and tundra

Tundra

In physical geography, tundra is a biome where the tree growth is hindered by low temperatures and short growing seasons. The term tundra comes through Russian тундра from the Kildin Sami word tūndâr "uplands," "treeless mountain tract." There are three types of tundra: Arctic tundra, alpine...

cover a large part of the region. Average winter temperatures range from -19 °C to -38 °C (even lower in the interior), and average summer temperatures, from +3 °C to +16 °C. There are rich reserves of gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

, silver

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

, tin

Tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a main group metal in group 14 of the periodic table. Tin shows chemical similarity to both neighboring group 14 elements, germanium and lead and has two possible oxidation states, +2 and the slightly more stable +4...

, tungsten

Tungsten

Tungsten , also known as wolfram , is a chemical element with the chemical symbol W and atomic number 74.A hard, rare metal under standard conditions when uncombined, tungsten is found naturally on Earth only in chemical compounds. It was identified as a new element in 1781, and first isolated as...

, mercury

Mercury (element)

Mercury is a chemical element with the symbol Hg and atomic number 80. It is also known as quicksilver or hydrargyrum...

, copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

, antimony

Antimony

Antimony is a toxic chemical element with the symbol Sb and an atomic number of 51. A lustrous grey metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite...

, coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

, oil

Oil

An oil is any substance that is liquid at ambient temperatures and does not mix with water but may mix with other oils and organic solvents. This general definition includes vegetable oils, volatile essential oils, petrochemical oils, and synthetic oils....

, and peat

Peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation matter or histosol. Peat forms in wetland bogs, moors, muskegs, pocosins, mires, and peat swamp forests. Peat is harvested as an important source of fuel in certain parts of the world...

. Twenty-nine zones of possible oil and gas accumulation have been identified on the Sea of Okhotsk

Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean, lying between the Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands on the southeast, the island of Hokkaidō to the far south, the island of Sakhalin along the west, and a long stretch of eastern Siberian coast along the west and...

shelf. Total reserves are estimated at 3.5 billion tons of equivalent fuel, including 1.2 billion tons of oil and 1.5 billion m3 of gas.

The principal town, Magadan

Magadan

Magadan is a port town on the Sea of Okhotsk and gateway to the Kolyma region. It is the administrative center of Magadan Oblast , in the Russian Far East. Founded in 1929 on the site of an earlier settlement from the 1920s, it was granted the status of town in 1939...

, with a population of 99,399 and an area of 18 square kilometers, is the largest port of north-eastern Russia. It has a large fishing fleet and remains open year-round with the help of icebreakers. Magadan is served by the nearby Sokol Airport

Sokol Airport

Sokol Airport is an airport in Sokol in Magadan Oblast, Russia. The airport is located 70 km north of the Magadan city center. The airport is sometimes confused with Dolinsk-Sokol air base, which was home to the fighters that shot down Korean Air Flight 007.In 1991, the town gained...

. There are many public and private farming enterprises. Gold mining works, pasta and sausage plants, fishing companies, and a distillery form the city's industrial base.

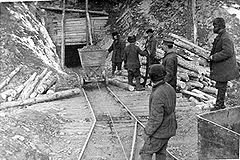

History

Under Joseph StalinJoseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's rule, Kolyma became the most notorious region for the Gulag

Gulag

The Gulag was the government agency that administered the main Soviet forced labor camp systems. While the camps housed a wide range of convicts, from petty criminals to political prisoners, large numbers were convicted by simplified procedures, such as NKVD troikas and other instruments of...

labor camp

Labor camp

A labor camp is a simplified detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons...

s. A million or more people may have died en route to the area or in the Kolyma's series of gold mining

Gold mining

Gold mining is the removal of gold from the ground. There are several techniques and processes by which gold may be extracted from the earth.-History:...

, road building, lumbering, and construction camps between 1932 and 1954. It was Kolyma's reputation that caused Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn was aRussian and Soviet novelist, dramatist, and historian. Through his often-suppressed writings, he helped to raise global awareness of the Gulag, the Soviet Union's forced labor camp system – particularly in The Gulag Archipelago and One Day in the Life of...

, author of The Gulag Archipelago

The Gulag Archipelago

The Gulag Archipelago is a book by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn based on the Soviet forced labor and concentration camp system. The three-volume book is a narrative relying on eyewitness testimony and primary research material, as well as the author's own experiences as a prisoner in a gulag labor camp...

, to characterize it as the "pole of cold and cruelty" in the Gulag system. The Mask of Sorrow

Mask of Sorrow

The Mask of Sorrow is a monument perched on a hill above Magadan, Russia, commemorating the many prisoners who suffered and died in the Gulag prison camps in the Kolyma region of the Soviet Union during the 1930s, 40s, and 50s. It consists of a large stone statue of a face, with tears coming from...

monument in Magadan commemorates all those who died in the Kolyma forced-labour camps and the recently dedicated Church of the Nativity

Church of the Nativity (Magadan)

The Church of the Nativity at Magadan in the Russian Far East serves local Roman Catholics, many of whom survived Stalin's forced labor camps set up in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s to exploit gold in Kolyma's harsh subarctic climate...

remembers the victims in its icons and Stations of the Camps.

Emergence of the Gulag camps

GoldGold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

and platinum

Platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the chemical symbol Pt and an atomic number of 78. Its name is derived from the Spanish term platina del Pinto, which is literally translated into "little silver of the Pinto River." It is a dense, malleable, ductile, precious, gray-white transition metal...

were discovered in the region in the early 20th century. During the time of the USSR's industrialization (beginning with Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's First Five-Year Plan

First Five-Year Plan

The First Five-Year Plan, or 1st Five-Year Plan, of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was a list of economic goals that was designed to strengthen the country's economy between 1928 and 1932, making the nation both militarily and industrially self-sufficient. "We are fifty or a hundred...

, 1928–1932) the need for capital to finance economic development was great. The abundant gold resources of the area seemed tailor-made to provide this capital. A government agency Dalstroy

Dalstroy

Dalstroy , also known as Far North Construction Trust, was an organization set up in 1931 by the Soviet NKVD in order to manage road construction and the mining of gold in the Chukotka region of the Russian Far East, now known as Kolyma. Initially it was established as State Trust for Road and...

was formed to organize the exploitation of the area. Prisoners were being drawn into the Soviet penal system in large numbers during the initial period of Kolyma's development, most notably from the so-called anti-Kulak

Kulak

Kulaks were a category of relatively affluent peasants in the later Russian Empire, Soviet Russia, and early Soviet Union...

campaign and the government's internal war to force collectivization on the USSR's peasantry. These prisoners formed a readily available workforce.

White Sea-Baltic Canal

The White Sea – Baltic Sea Canal , often abbreviated to White Sea Canal is a ship canal in Russia opened on 2 August 1933. It connects the White Sea with Lake Onega, which is further connected to the Baltic Sea. Until 1961, its original name was the Stalin White Sea – Baltic Sea Canal...

.) After a gruelling train ride (on the Trans-Siberian Railway

Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway is a network of railways connecting Moscow with the Russian Far East and the Sea of Japan. It is the longest railway in the world...

, the longest in the USSR), prisoners were disembarked at one of several transit camps (such as Nakhodka

Nakhodka

Nakhodka is a port city in Primorsky Krai, Russia, situated on the Trudny Peninsula jutting into the Nakhodka Bay of the Sea of Japan, about east of Vladivostok...

and later Vanino

Vanino, Khabarovsk Krai

Vanino is an urban-type settlement and the administrative center of Vaninsky District of Khabarovsk Krai, Russia. It is an important port on the Strait of Tartary , served by the BAM railway line...

) and transported across the Sea of Okhotsk

Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean, lying between the Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands on the southeast, the island of Hokkaidō to the far south, the island of Sakhalin along the west, and a long stretch of eastern Siberian coast along the west and...

to the natural harbor chosen for Magadan's construction. Conditions aboard the ships were harsh.

In 1932 expeditions pushed their way into the interior of the Kolyma, embarking on the construction of the Kolyma Highway, which was to become known as the Road of Bones. Eventually, about 80 different camps dotted the region of the uninhabited taiga

Taiga

Taiga , also known as the boreal forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests.Taiga is the world's largest terrestrial biome. In North America it covers most of inland Canada and Alaska as well as parts of the extreme northern continental United States and is known as the Northwoods...

.

The original director of the Kolyma camps was Eduard Berzin

Eduard Berzin

Eduard Petrovich Berzin , born in Latvia, was a soldier and Chekist, but is remembered primarily for setting up Dalstroy, which instituted a system of forced-labour camps in Kolyma, North-Eastern Siberia, where hundreds of thousands of prisoners died...

, a Chekist. Berzin was later removed (1937) and shot during the period of the Great Purge

Great Purge

The Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated by Joseph Stalin from 1936 to 1938...

s in the USSR.

The Arctic death camps

In 1937, at the height of the Purges, Stalin ordered an intensification of the hardships prisoners were forced to endure. Aleksandr SolzhenitsynAleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn was aRussian and Soviet novelist, dramatist, and historian. Through his often-suppressed writings, he helped to raise global awareness of the Gulag, the Soviet Union's forced labor camp system – particularly in The Gulag Archipelago and One Day in the Life of...

quotes camp commander Naftaly Frenkel

Naftaly Frenkel

Naftaly Aronovich Frenkel ; was a Soviet citizen and Chekist . Frenkel is best known for his role in the organisation of work in the Gulag, starting from the forced labor camp of the Solovetsky Islands, which is recognised as one of the earliest sites of the Gulag. -Origins:Naftaly Frenkel's...

as establishing the new law of the Archipelago: "We have to squeeze everything out of a prisoner in the first three months — after that we don't need him anymore." The system of hard labor and minimal or no food reduced most prisoners to helpless "goners" (dokhodyaga, in Russian).

Robert Conquest

Robert Conquest

George Robert Ackworth Conquest CMG is a British historian who became a well-known writer and researcher on the Soviet Union with the publication in 1968 of The Great Terror, an account of Stalin's purges of the 1930s...

, Yevgenia Ginzburg

Yevgenia Ginzburg

Yevgenia Ginzburg was a Russian author who served an 18-year sentence in the Gulag. Her given name is often Latinized to Eugenia.-Family and early career:...

, Anne Applebaum

Anne Applebaum

Anne Elizabeth Applebaum is a journalist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author who has written extensively about communism and the development of civil society in Central and Eastern Europe. She has been an editor at The Economist, and a member of the editorial board of The Washington Post...

, Adam Hochschild

Adam Hochschild

Adam Hochschild is an American author and journalist.-Biography:Hochschild was born in New York City. As a college student, he spent a summer working on an anti-government newspaper in South Africa and subsequently worked briefly as a civil rights worker in Mississippi in 1964...

and others (see bibliography) describe the Kolyma camps in some detail. The suffering of the prisoners was exacerbated by the presence of ordinary criminals, who terrorized the "political" prisoners. Death in the Kolyma camps came in many forms, including: overwork, starvation, malnutrition, mining accidents, exposure, murder at the hands of criminals, and beatings at the hands of guards. A director of the Sevvostlag

Sevvostlag

Sevvostlag was a system of forced labor camps set up to satisfy the workforce requirements of the Dalstroy construction trust in the Kolyma region in April 1932. Organizationally being part of Dalstroy and under the management of the Labor and Defence Council of Sovnarkom, these camps were...

complex of camps, Colonel Sergey Garanin, is said to have personally shot whole brigades of prisoners for not fulfilling their daily quotas in the late 1930s. Escape was difficult, owing to the climate and physical isolation of the region, but some still attempted it. Escapees, if caught, were often torn to shreds by camp guard dogs. The use of torture as punishment was also common. Soviet dissident historian Roy Medvedev

Roy Medvedev

Roy Aleksandrovich Medvedev |Georgia]]) is a Russian historian renowned as the author of the dissident history of Stalinism, Let History Judge , first published in English in 1972...

has compared the conditions in the Kolyma camps to Auschwitz.

Mikhail Kravchuk

Mikhail Filippovich Kravchuk, also Krawtchouk was a Ukrainian mathematician who, despite his early death, was the author of around 180 articles on mathematics....

(Krawtschuk), a Ukrainian mathematician who by the early 1930s had received considerable acclaim in the West. After a summary trial, apparently for not being willing to take part in the accusations of some of his colleagues, he was sent to Kolyma where he died in 1942. Hard work in the Soviet labor camp, harsh climate and meager food, poor health, and last but not least, accusations and abandonment by most of his colleagues, took their toll. Kravchuk perished in Magadan in Eastern Siberia, about 4,000 miles (6,000 km) from the place where he was born. Kravchuk's last article had appeared soon after his arrest in 1938. However, after this publication, Kravchuk's name was stricken from books and journals.

The prisoner population of Kolyma was substantially increased in 1946 with the arrival of thousands of former Soviet POWs liberated by Allied forces or the Red Army at the close of World War II. Those judged guilty of collaboration with the enemy frequently received ten or twenty-five year prison sentences to a gulag, including Kolyma.

There were, however, some exceptions. Léon Theremin

Léon Theremin

Léon Theremin was a Russian and Soviet inventor. He is most famous for his invention of the theremin, one of the first electronic musical instruments. He is also the inventor of interlace, a technique of improving the picture quality of a video signal, widely used in video and television technology...

, an inventor, was rumored to have been seized by Soviet agents in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and forced to return to the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, but actually returned voluntarily. He was, on Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's order, imprisoned at Butyrka and later sent to work in the Kolyma gold mines. Although rumors of his execution were widely circulated, Theremin was, in fact, put to work in a sharashka

Sharashka

Sharashka was an informal name for secret research and development laboratories in the Soviet Gulag labor camp system...

or secret research laboratory, together with other scientists and engineers, including aircraft designer Andrei Tupolev

Andrei Tupolev

Andrei Nikolayevich Tupolev was a pioneering Soviet aircraft designer.During his career, he designed and oversaw the design of more than 100 types of aircraft, some of which set 78 world records...

and rocket scientist Sergei Korolyov (also a Kolyma inmate). The Soviet Union rehabilitated Theremin in 1956.

The Kolyma camps were converted to (mostly) free labor after 1954, and in 1956 Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

ordered a general amnesty that freed many prisoners.

Dalstroy officials

DalstroyDalstroy

Dalstroy , also known as Far North Construction Trust, was an organization set up in 1931 by the Soviet NKVD in order to manage road construction and the mining of gold in the Chukotka region of the Russian Far East, now known as Kolyma. Initially it was established as State Trust for Road and...

was the agency created to manage exploitation of the Kolyma area, based principally on the use of forced labour.

In the words of Azerbaijani prisoner Ayyub Baghirov, "The entire administration of the Dalstroy

Dalstroy

Dalstroy , also known as Far North Construction Trust, was an organization set up in 1931 by the Soviet NKVD in order to manage road construction and the mining of gold in the Chukotka region of the Russian Far East, now known as Kolyma. Initially it was established as State Trust for Road and...

- economic, administrative, physical and political — was in the hands of one person who was invested with many rights and privileges." The officials in charge of Dalstroy, i.e., the Kolyma Gulag camps were:

- Eduard Petrovich BerzinEduard BerzinEduard Petrovich Berzin , born in Latvia, was a soldier and Chekist, but is remembered primarily for setting up Dalstroy, which instituted a system of forced-labour camps in Kolyma, North-Eastern Siberia, where hundreds of thousands of prisoners died...

, 1932–1937 - Karp Aleksandrovich Pavlov, 1937–1939.

- Ivan Fedorovich Nikishev, 1940–1948.

- Ivan Grigorevich Petrenko, 1948–1950.

- I.L. Mitrakov, from 1950 until Dalstroy was taken over by the Ministry of Metallurgy on 18 March 1953.

Calendar of historical events

A detailed calendar of events:- 1928–1929: Gold mines established in the Kolyma River region. Commencement of regular mining operations

- 13 November 1931: Establishment of DalstroyDalstroyDalstroy , also known as Far North Construction Trust, was an organization set up in 1931 by the Soviet NKVD in order to manage road construction and the mining of gold in the Chukotka region of the Russian Far East, now known as Kolyma. Initially it was established as State Trust for Road and...

- 4 February 1932: Eduard Berzin, Manager of Dalstroy, arrives with the first 10 prisoners.

- 1934: The headcount increases to 30,000 inmates.

- 1937: The number of inmates increases to over 70.000; 51,500 kg of gold mined

- June 1937: Stalin reprimands the Kolyma commandants for their undue leniency towards the inmates.

- December 1937: Berzin is charged with espionage and subsequently tried and shot in August 1938.

- March 4, 1938: Dalstroy is put under the jurisdiction of NKVDNKVDThe People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

, USSR. - December 1938: Osip MandelstamOsip MandelstamOsip Emilyevich Mandelstam was a Russian poet and essayist who lived in Russia during and after its revolution and the rise of the Soviet Union. He was one of the foremost members of the Acmeist school of poets...

, an eminent Russian poet, dies in a transit camp en route to Kolyma. - 1939: Number of inmates now 138,200.

- 11 October 1939: Commandants Pavlov (Dalstroy) and Garanin (Sevvostlag) sacked from their posts. Garanin subsequently shot.

- 1941: Headcount of inmates reaches 190,000. Also some 3,700 Dalstroy contract workers.

- May 23, 1944: US Vice President Henry A. WallaceHenry A. WallaceHenry Agard Wallace was the 33rd Vice President of the United States , the Secretary of Agriculture , and the Secretary of Commerce . In the 1948 presidential election, Wallace was the nominee of the Progressive Party.-Early life:Henry A...

arrives for a NKVD-hosted 25-day tour of Magadan, Kolyma, and the Russian Far East. - October 1945: Camp for the Japanese prisoners of war is established in Magadan, to provide extra labour.

- 1952: 199,726 inmates, the highest ever in the history of the Kolyma camps and Dalstroy.

- May 1952: According to commandant Mitrakov, Sevvoslag is dissolved, Dalstroy transformed into the General Board of Labour Camps

- March 1953: After Stalin's death, Dalstroy transferred to the Ministry of Metallurgy, camp units come under the jurisdiction of the Soviet Ministry of Justice.

- September 1953: Dalstroy camp units taken over by the newly established Management Board of the North-Eastern Corrective Labour Camps. Harsh camp regime gradually relaxed.

- 1953–1956: Period of mass amnesties and the release of most political prisoners. Some camp closures begin.

- 1957: Dalstroy liquidated. Many of the former prisoners continued to work in the mines with a modified status and a few new prisoners arrived, at least until the early 1970s.

Post-Dalstroy developments

The Chukot Autonomous Okrug site provides details of developments after the official closure of the camps. In 1953, the Magadan OblastMagadan Oblast

Magadan Oblast is a federal subject of Russia in the Far Eastern Federal District. Its administrative center is the city of Magadan....

(or region) was established. Dalstroy was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Metallurgy and later to the Ministry of Non-Ferrous Metallurgy.

Industrial and economic evolution

Industrial gold-mining started in 1958 leading to the development of mining settlements, industrial enterprises, power plants, hydro-electric dams, power transmission lines and improved roads. By the 1960s, the region's population exceeded 100,000.With the dissolution of Dalstroy, the Soviets adopted new labor policies. While the prison labor was still important, it mainly consisted of common criminals. New manpower was recruited from all Soviet nationalities on a voluntary basis, to make up for the sudden lack of political prisoner

Political prisoner

According to the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, a political prisoner is ‘someone who is in prison because they have opposed or criticized the government of their own country’....

s. Young men and women were lured to the frontier land of Kolyma with the promise of high earnings and better living. But many decided to leave.

The region's prosperity suffered under Soviet liberal policies in the end of the 1980s and 1990s with a considerable reduction in population, apparently by 40% in Magadan. A U.S. report from the late 1990s gives details of the region's economic shortfall citing outdated equipment, bankruptcies of local companies and lack of central support. It does however report substantial investments from the United States and the governor's optimism for future prosperity based on revival of the mining industries.

Last political prisoners

Dalstroy and the camps did not close down completely. The Kolyma authority, which was reorganised in 1958/59 (31 December 1958), finally closed in 1968. However the mining activities did not stop. Indeed, government structures still exist today under the Ministry of Natural Resources. In some cases, the same individuals seem to have stayed on over the years under new management.There are indications that the political prisoner

Political prisoner

According to the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, a political prisoner is ‘someone who is in prison because they have opposed or criticized the government of their own country’....

s were gradually phased out over the years but it was only as a result of Boris Yeltsin

Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin was the first President of the Russian Federation, serving from 1991 to 1999.Originally a supporter of Mikhail Gorbachev, Yeltsin emerged under the perestroika reforms as one of Gorbachev's most powerful political opponents. On 29 May 1990 he was elected the chairman of...

's far reaching reforms in the 1990s that the very last prisoners were released from Kolyma.

The Russian author Andrei Amalrik

Andrei Amalrik

Andrei Alekseevich Amalrik , alternatively spelled Andrei or Andrey, was a Russian writer and dissident....

appears to have been one of the last high-profile political prisoner

Political prisoner

According to the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, a political prisoner is ‘someone who is in prison because they have opposed or criticized the government of their own country’....

s to be sent to Kolyma. In 1970, he published two books: Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984? and Involuntary Journey to Siberia. As a result, he was arrested for "defaming the Soviet state" in November 1970 and sentenced to hard labour, apparently in Kolyma, for what turned out to be a total of almost five years.

Accounts of the Kolyma Gulag

A detailed description of conditions in the camps is provided by Varlam ShalamovVarlam Shalamov

Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov , baptized as Varlaam, was a Russian writer, journalist, poet and Gulag survivor.-Early life:Varlam Shalamov was born in Vologda, Vologda Governorate, a Russian city with a rich culture famous for its wooden architecture, to a family of a hereditary Russian Orthodox...

in his Kolyma Tales. In Dry Rations he writes: "Each time they brought in the soup... it made us all want to cry. We were ready to cry for fear that the soup would be thin. And when a miracle occurred and the soup was thick we couldn’t believe it and ate it as slowly as possible. But even with thick soup in a warm stomach there remained a sucking pain; we’d been hungry for too long. All human emotions—love, friendship, envy, concern for one’s fellow man, compassion, longing for fame, honesty — had left us with the flesh that had melted from our bodies...."

During and after the Second World War the region saw major influxes of Ukrainians

Ukrainians

Ukrainians are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine, which is the sixth-largest nation in Europe. The Constitution of Ukraine applies the term 'Ukrainians' to all its citizens...

, Polish

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

, German

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

, Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

ese, and Korea

Korea

Korea ) is an East Asian geographic region that is currently divided into two separate sovereign states — North Korea and South Korea. Located on the Korean Peninsula, Korea is bordered by the People's Republic of China to the northwest, Russia to the northeast, and is separated from Japan to the...

n prisoners. There is a particularly memorable account written by a Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

n survivor, Michael Solomon, in his book Magadan (see Bibliography below) which gives us a vivid picture of both the transit camps leading to the Kolyma and the region itself. The Hungarian, George Bien, author of the Lost Years, also recounts the horrors of Kolyma. His story has also led to a film.

Soviet Gold, the first autobiographical book written by Vladimir Nikolayevich Petrov, is almost entirely a description of the author's life in Magadan and the Kolyma gold fields.

In Bitter Days of Kolyma, Ayyub Baghirov, an Azerbaijani accountant who was finally rehabilitated, provides details of his arrest, torture and sentencing to eight (finally to become 18) years imprisonment in a labour camp for refusing to incriminate a fellow official for financial irregularities. Describing the train journey to Siberia, he writes: "The terrible heat, the lack of fresh air, the unbearable overcrowded conditions all exhausted us. We were all half starved. Some of the elderly prisoners, who had become so weak and emaciated, died along the way. Their corpses were left abandoned alongside the railroad tracks."

A vivid account of the conditions in Kolyma is that of Brother Gene Thompson of Kiev's Faith Mission. He recounts how he met Vyacheslav Palman, a prisoner who survived because he knew how to grow cabbages. Palman spoke of how guards read out the names of those to be shot every evening. On one occasion a group of 169 men were shot and thrown into a pit. Their fully clothed bodies were found after the ice melted in 1998.

One of the most famous political prisoners in Kolyma was Vadim Kozin

Vadim Kozin

Vadim Kozin was a Russian tenor.Vadim Alexeych Kozin was born the son of a merchant in Saint Petersburg to Alexei Gavrilovich Kozin and Vera Ilinskaya in 1903. His mother was a gypsy and often sang in the local gypsy choir...

, possibly Russia's most popular romantic tenor

Tenor

The tenor is a type of male singing voice and is the highest male voice within the modal register. The typical tenor voice lies between C3, the C one octave below middle C, to the A above middle C in choral music, and up to high C in solo work. The low extreme for tenors is roughly B2...

, who was sent to the camps in February 1945, apparently for refusing to write a song about Stalin. Although he was initially freed in 1950 and could return to his singing career, he was soon framed by his enemies on charges of homosexuality and sent back to the camps. Though released once again several years later, he was never officially rehabilitated and remained in exile in Magadan where he died in 1994. Speaking to journalists in 1982, he explained how he had been forced to tour the camps: "The Polit bureau formed brigades which would, under surveillance, go on tours of the concentration camps and perform for the prisoners and the guards, including those of the highest rank."

- In July 1993 Vadim Kozin told his story, sang and played his piano probably for the last time in the documentary on the Gulag in the far east of Siberia GOUD Vergeten in Siberië aka GOLD Lost in Siberia www.imdb.comhttp://www.imdb.com/title/tt0827767 by Dutch author Gerard Jacobs and filmmaker Theo UittenbogaardTheo UittenbogaardTheo Uittenbogaard is a Dutch radio & TV-producer, who worked for almost all nationwide public networks in The Netherlands since 1965. His training was on-the-job, since no school or academy geared to that profession existed in The Netherlands those days. He started as a 19-year old apprentice...

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm2320931/

Finally, Ukrainian prisoner Nikolai Getman

Nikolai Getman

Nikolai Getman , an artist, was born in 1917 in Kharkiv, Ukraine, and died at his home inOrel, Russia, in August 2004. He was a prisoner from 1946 to 1953 in forced labor camps in Siberia and Kolyma, where he survived as a result of his ability to sketch for the propaganda requirements of the...

who spent the years 1945-1953 in Kolyma, records his testimony in pictures rather than words. But he does have a plea: "Some may say that the Gulag is a forgotten part of history and that we do not need to be reminded. But I have witnessed monstrous crimes. It is not too late to talk about them and reveal them. It is essential to do so. Some have expressed fear on seeing some of my paintings that I might end up in Kolyma again — this time for good. But the people must be reminded... of one of the harshest acts of political repression in the Soviet Union. My paintings may help achieve this." The Jamestown Foundation provides access to all 50 of Getman's paintings together with explanations of their significance.

Estimating the number of victims

While comparatively complete lists of the prisoners in the Nazi concentration campsNazi concentration camps

Nazi Germany maintained concentration camps throughout the territories it controlled. The first Nazi concentration camps set up in Germany were greatly expanded after the Reichstag fire of 1933, and were intended to hold political prisoners and opponents of the regime...

have survived, the amount of hard evidence in regard to Kolyma is extremely limited. Unfortunately, no reliable archives exist about the total number of victims of Stalinism

Stalinism

Stalinism refers to the ideology that Joseph Stalin conceived and implemented in the Soviet Union, and is generally considered a branch of Marxist–Leninist ideology but considered by some historians to be a significant deviation from this philosophy...

; all numbers are estimates. In his book, Stalin (1996), Edvard Radzinsky

Edvard Radzinsky

Edvard Stanislavovich Radzinsky is a Russian playwright, writer, TV personality, and film screenwriter. He is also known as an author of several books on history which were characterized as "folk history" by journalists and academic historians.-Biography:Edvard Stanislavovich Radzinsky was born...

explains how Stalin, while systematically destroying his comrades-in-arms "at once obliterated every trace of them in history. He personally directed the constant and relentless purging of the archives." That practice continued to exist after the death of the dictator.

In an account of a visit to Magadan by Harry Wu

Harry Wu

Harry Wu is an activist for human rights in the People's Republic of China. Now a resident and citizen of the United States, Wu spent 19 years in Chinese labor camps. In 1992, he founded the Laogai Research Foundation. In 1996 the Columbia Human Rights Law Review awarded Wu its second Award for...

in 1999, there is a reference to the efforts of Alexander Biryukov, a Magadan lawyer to document the terror. He is said to have compiled a book listing every one of the 11,000 people documented to have been shot in Kolyma camps by the state security organ, the NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

. Biryukov, whose father was in the Gulag at the time he was born, has begun researching the location of graves. He believed some of the bodies were still partially preserved in the permafrost.

It is therefore impossible to provide final figures on the number of victims who died in Kolyma. Robert Conquest, author of The Great Terror, now admits that his original estimate of three million victims was far too high. In his article Death Tolls for the Man-made Megadeaths of the 20th Century, Matthew White

Matthew White

Matt White or Matthew White is the name of:*Matt White , left-handed baseball pitcher and rock entrepreneur*Matt White , Australian cyclist*Matt White , American ice hockey player...

estimates the number of those who died at 500,000. In Stalin's Slave Ships, Martin Bollinger undertakes a careful analysis of the number of prisoners who could have been transported by ship to Magadan between 1932 and 1953 (some 900,000) and the probable number of deaths each year (averaging 27%). This produces figures significantly below earlier estimates but, as the author emphasizes, his calculations are by no means definitive. In addition to the number of deaths, the dreadful conditions of the camps and the hardships experienced by the prisoners over the years need to be taken into account. In his review of Bollinger's book, Norman Polmar independently estimates there were more than 3,000,000 victims who died at Kolyma. As Bollinger reports in his book, the 3,000,000 estimate originated with the CIA in the 1950s and appears to be a flawed estimate. This number is also estimated by the last survivors.

Anne Applebaum

Anne Applebaum

Anne Elizabeth Applebaum is a journalist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author who has written extensively about communism and the development of civil society in Central and Eastern Europe. She has been an editor at The Economist, and a member of the editorial board of The Washington Post...

, a Pulitzer Prize winner, carried out an extensive investigation of the gulags, and explained in a lecture in 2003, that it's extremely difficult not only to document the facts given the extent of the cover-up but to bring the truth home.

External links

- Kolyma; the Land of Gold and Death A personal on-line account in nine chapters by Stanislaw J. Kowalski, a Polish prisoner in Kolyma, with numerous references

- The Soviet Gulag Era in Pictures, 1927-1953 Photographs, several of Kolyma, collected by James Duncan

- Crimes of Soviet Communists Wide collection of sources and links about GULAG also in Kolyma

- Kolyma - Stalin's Notorious Prison Camps in Siberia, Personal Account by Ayyub Baghirov in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 14:1 (Spring 2006), pp. 58-71.

- The White Crematorium Background information on the Gulag and the Kolyma camps by Jens Alstrup who cycled across Russia to Magadan in 1997 and has frequently returned to continue his research. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- Kolyma, Mikhail Mikheev's 1995 documentary film winner of both the Amsterdam and Berlin film festivals

- Work in the Gulag from the Stalin's Gulag section of the Online Gulag Museum with a short description and images of Kolyma

- GULAG: Many Days, Many Lives, Online Exhibit, Center for History and New Media, George Mason University

- Virtual Gulag Museum The Saint-Petersburg Research and Information Centre “Memorial” linking to museums in Russia, eastern Europe and Asia on the history of Soviet Terror, the Gulag and the resistance

- Gulag prisoners at work, 1936-1937 Photoalbum at the New York Public Library's Digital Gallery

- Italian-American artist Thomas Sgovio (1916–1997) created a series of drawings and paintings, based on his life as a prisoner in the Soviet Gulag

- Russian-language history of Dalstroy from Kolyma.ru

Links to Maps

- Detailed Russian map of the Kolyma Gulag from the site Jewish Community in Magadan

- Russian Map of the Gulag camps across the Soviet Union from the Memorial site