Hungary between the two world wars

Encyclopedia

This article is about the history of Hungary

from October 1918 to November 1940.

was created by revolution that started in Budapest

after the dissolution and break-up of Austria-Hungary

at the end of World War I

. The official proclamation of the republic was on November 16, 1918, and Mihály Károlyi

was named as the republic's Prime Minister. This event also marked the independence of Hungary which had been ruled by the Habsburg Monarchy

for several centuries.

The Hungarian Democratic Republic did not last long. Another revolution in 1919 marked the end of this state and the creation of a new communist state known as Hungarian Soviet Republic.

The rise of the Hungarian Communist Party

The rise of the Hungarian Communist Party

(HCP) to power was rapid. The party was organized in a Moscow

hotel on November 4, 1918, when a group of Hungarian prisoners of war and communist sympathizers formed a Central Committee and dispatched members to Hungary to recruit new members, propagate the party's ideas, and radicalize Károlyi

's government. By February 1919, the party numbered 30,000 to 40,000 members, including many unemployed ex-soldiers, young intellectuals, and Jews. In the same month, Béla Kun

was imprisoned for incitement to riot, but his popularity skyrocketed when a journalist reported that he had been beaten by the police. Kun emerged from jail triumphant when the Social Democrats handed power to a government of "People's Commissars," who proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic on March 21, 1919.

The communists wrote a temporary constitution

guaranteeing freedom of speech

and assembly

; free education, language and cultural rights to minorities

; and other rights. It also provided for suffrage

for people over eighteen years of age except clergy

, "former exploiters," and certain others. Single-list elections took place in April, but members of the parliament were selected indirectly by popularly elected committees. On June 25, Kun's government proclaimed a dictatorship of the proletariat

, nationalized industrial and commercial enterprises, and socialized housing, transport, banking, medicine, cultural institutions, and all landholdings of more than 40.5 hectares. Kun undertook these measures even though the Hungarian communists were relatively few, and the support they enjoyed was based far more on their program to restore Hungary's borders than on their revolutionary agenda. Kun hoped that the Russian government would intervene on Hungary's behalf and that a worldwide workers' revolution

was imminent. In an effort to secure its rule in the interim, the communist government resorted to arbitrary violence. Revolutionary tribunals ordered about 590 executions, including some for "crimes against the revolution." The government also used "red terror

" to expropriate grain from peasants. This violence and the regime's moves against the clergy also shocked many Hungarians.

In late May, Kun attempted to fulfill his promise to restore Hungary's borders

. The Hungarian Red Army marched northward and reoccupied part of Slovakia

. Despite initial military success, however, Kun withdrew his troops about three weeks later when the French

threatened to intervene. This concession shook his popular support. Kun then unsuccessfully turned the Hungarian Red Army on the Romania

ns, who broke through Hungarian lines on July 30, occupied Budapest

, and ousted Kun's Soviet Republic on August 1, 1919. Kun fled first to Vienna

and then to the Russian SFSR, where he was executed during Stalin's purge

of foreign communists in the late 1930s.

" ensued that led to the imprisonment, torture, and execution without trial of communists, socialists, Jews

, leftist intellectuals, sympathizers with the Károlyi and Kun regimes, and others who threatened the traditional Hungarian political order that the officers sought to reestablish. Estimates placed the number of executions at approximately 5,000. In addition, about 75,000 people were jailed. In particular, the Hungarian right wing and the Romanian forces targeted Jews for retribution. Ultimately, the white terror forced nearly 100,000 people to leave the country, most of them socialists, intellectuals, and middle-class Jews.

was named Regent

and Sándor Simonyi-Semadam

was named Prime Minister of the restored Kingdom of Hungary. Charles I of Austria (known as Charles IV, Karl IV, or IV. Károly in Hungary) was the last Emperor of Austria

and the last King of Hungary

. He was not asked to fill the vacant Hungarian throne.

The government of Horthy immediately declared null and void all laws and edicts passed by the Karolyi and Kun regimes, in effect renouncing the 1918 armistice. Horthy's authoritarianism and the violent anti-communist backlash resulted in interwar Hungary having one of the quietest political landscapes in Eastern Europe. Later on, when he wished to take out loans from the West, they pressured him into democratic reforms. Horthy only did as much as he absolutely had to, since the Western powers were geographically distant from Hungary and soon turned their attention to matters elsewhere.

Horthy appointed Pál Teleki

as Prime Minister in July 1920. His right-wing government set quotas effectively limiting admission of Jews to universities, legalized capital punishment, and to quiet rural discontent, took initial steps towards fulfilling a promise of major land reform by dividing about 385,000 hectares from the largest estates into smallholdings. Teleki's government resigned, however, after the former Austrian Emperor, Charles IV, unsuccessfully attempted to retake Hungary's throne in March 1921. King Charles' return split parties between conservatives who favored a Habsburg

restoration and nationalist right-wing radicals who supported election of a Hungarian king. István Bethlen

, a nonaffiliated, right-wing member of the parliament, took advantage of this rift by convincing members of the Christian National Union who opposed Karl's re-enthronement to merge with the Smallholders' Party and form a new Party of Unity with Bethlen as its leader. Horthy then appointed Bethlen Prime Minister.

As Prime Minister, Bethlen dominated Hungarian politics between 1921 and 1931. He fashioned a political machine by amending the electoral law, eliminating peasants from the Party of Unity, providing jobs in the bureaucracy to his supporters, and manipulating elections in rural areas. Bethlen restored order to the country by giving the radical counter-revolutionaries payoffs and government jobs in exchange for ceasing their campaign of terror against Jews and leftists. In 1921, Bethlen made a deal with the Social Democrats and trade unions, agreeing, among other things, to legalize their activities and free political prisoners in return for their pledge to refrain from spreading anti-Hungarian propaganda, calling political strikes, and organizing the peasantry. In May 1922, the Party of Unity captured a large parliamentary majority. Charles IV's death, soon after he failed a second time to reclaim the throne in October 1921, allowed the revision of the Treaty of Trianon

to rise to the top of Hungary's political agenda. Bethlen's strategy to win the treaty's revision was first to strengthen his country's economy and then to build relations with stronger nations that could further Hungary's goals. Revision of the treaty had such a broad backing in Hungary that Bethlen used it, at least in part, to deflect criticism of his economic, social, and political policies. However, Bethlen's only foreign policy success was a treaty of friendship with Italy

in 1927, which had little immediate impact.

, which advocated land reform. In March, the parliament annulled both the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713

and the Compromise of 1867, and it restored the Hungarian monarchy but postponed electing a king until civil disorder had subsided. Instead, Admiral Miklós Horthy

— a former commander in chief of the Austro-Hungarian navy—was elected regent

and was empowered, among other things, to appoint Hungary's prime minister, veto legislation, convene or dissolve the parliament, and command the armed forces.

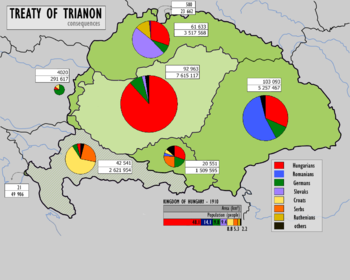

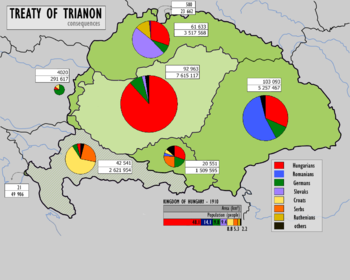

Hungary's signing of the Treaty of Trianon

Hungary's signing of the Treaty of Trianon

on June 4, 1920, ratified the country's dismemberment, limited the size of its armed forces, and required reparations payments. The territorial provisions of the treaty, which ensured continued discord between Hungary and its neighbors, required the Hungarians to surrender more than two-thirds of their prewar lands. Romania

acquired Transylvania

; Yugoslavia

gained Croatia

, Slavonia

, and Vojvodina

; Slovakia

became a part of Czechoslovakia

; and Austria

also acquired a small piece of pre-war Hungarian territory. Hungary also lost about 60 percent of its pre-war population, and about one-third of the 10 million ethnic Hungarians found themselves outside the diminished homeland. The country's ethnic composition was left almost homogeneous. Hungarians constituted about 90 percent of the population

, Germans made up about 6 to 8 percent, and Slovaks, Croats, Romanians, Jews, and other minorities accounted for the remainder.

New international borders separated Hungary's industrial base from its sources of raw materials and its former markets for agricultural and industrial products. Its new circumstances forced Hungary to become a trading nation. Hungary lost 84 percent of its timber resources, 43 percent of its arable land, and 83 percent of its iron ore. Because most of the country's prewar industry was concentrated near Budapest, Hungary retained about 51 percent of its industrial population, 56 percent of its industry, 82 percent of its heavy industry, and 70 percent of its banks.

(1922), the Bethlen government was able to borrow a 50 million USD loan from the League, which in order to protect its investment placed the country in effective receivership, even placing an American banker, Jeremiah Smith, in charge of the country's finances. Hungary's outcast status had prevented it from obtaining any foreign aid in the immediate postwar period, but by the middle of the 1920s, the British decided to extend the hand of friendship to the losers of World War I. Hungary also obtained sympathy from the United States and Mussolini's Italy. Meanwhile, France and Hungary's neighbors vigorously objected.

By the late 1920s, Bethlen's policies had brought order to the economy. The number of factories increased by about 66 percent, inflation subsided, and the national income climbed 20 percent. However, the apparent stability was supported by a rickety framework of constantly revolving foreign credits and high world grain prices; therefore, Hungary remained undeveloped in comparison with the wealthier western Europe

an countries, as most of the foreign loans went for non-productive purposes such as graft, expanding bureaucracy, and monumental public works projects. Agricultural products were subject to unstable prices and the vagaries of the weather. Furthermore, tariffs were commonplace in America and Europe during the 1920s, which frequently made it difficult to export. Hungary was no exception and liberally employed trade barriers to protect its manufacturing base. Exports also had to pass through Hungary's neighbors to reach the West, and as noted above, all but one was hostile.

Despite economic progress, the workers' standard of living remained poor, and consequently the working class never gave Bethlen its political support. The labor movement had never developed in pre-WWI Hungary the way it did in Austria, and the Horthy government remained resolutely opposed to organized labor or social reforms. There was no minimum wage or any sort of labor laws in Hungary almost until the start of World War II, and wages were further undercut by peasants flocking into Budapest who were willing to work for almost nothing. On the whole, workers fared more poorly in interwar Hungary then they had before World War I. The peasants were even worse off than the working class. In the 1920s, about 60 percent of the peasants were either landless or were cultivating plots too small to provide a decent living. Real wages for agricultural workers remained below prewar levels, and the peasants had practically no political voice. Moreover, once Bethlen had consolidated his power, he ignored calls for land reform. The industrial sector failed to expand fast enough to provide jobs for all the peasants and university graduates seeking work. Most peasants lingered in the villages, and in the 1930s Hungarians in rural areas were extremely dissatisfied. Hungary's foreign debt ballooned as Bethlen expanded the bureaucracy to absorb the university graduates who, if left idle, might have threatened civil order. This was because Hungary, like the rest of Eastern Europe, had an educational system primarily focused on the liberal arts and law rather than science, engineering, or other practical subjects that might have helped the country's development. University graduates mostly sought employment in the bureaucracy, where they were guaranteed an easy, secure job. When they could not obtain work, either because they lacked useful skills or because the swollen bureaucracy had no openings available, they would invariably blame their bad luck on Jews. This would contribute to an anti-Semitism in Hungary that would ultimately have tragic consequences.

Following the Wall Street Crash of 1929

in the United States

and the beginning of the Great Depression

, world grain prices plummeted, and the framework supporting Hungary's economy

buckled. Hungary's earnings from grain exports declined as prices and volume dropped, tax revenues fell, foreign credit sources dried up, and short-term loans were called in. The Hungarian national bank depleted its supply of precious metals and foreign currency during a period of a few weeks in 1931. Hungary sought financial relief from the League of Nations

, which insisted on a program of rigid fiscal belt-tightening, resulting in increased unemployment. The peasants reverted to subsistence farming. Industrial production rapidly dropped, and businesses went bankrupt as domestic and foreign demand evaporated. Government workers lost their jobs or suffered severe pay cuts. By 1933 about 18 percent of Budapest's citizens lived in poverty. Unemployment leaped from 5 percent in 1928 to almost 36 percent by 1933.

. Bethlen resigned without warning amid national turmoil in August 1931. His successor, Gyula Károlyi

, failed to quell the crisis. Horthy

then appointed a reactionary demagogue, Gyula Gömbös

, but only after Gömbös agreed to maintain the existing political system, to refrain from calling elections before the parliament's term had expired, and to appoint several Bethlen supporters to head key ministries. Gömbös publicly renounced the vehement antisemitism he had espoused earlier, and his party and government included some Jews

.

Gömbös's appointment marked the beginning of the radical right

's ascendancy in Hungarian politics, which lasted with few interruptions until 1945. The radical right garnered its support from medium and small farmers, former refugees from Hungary's lost territories, and unemployed civil servants, army officers, and university graduates. Gömbös advocated a one-party government, revision of the Treaty of Trianon

, withdrawal from the League of Nations

, anti-intellectualism, and social reform. He assembled a political machine, but his efforts to fashion a one-party state and fulfill his reform platform were frustrated by a parliament composed mostly of Bethlen's supporters and by Hungary's creditors, who forced Gömbös to follow conventional policies in dealing with the economic and financial crisis. The 1935 elections gave Gömbös more solid support in the parliament, and he succeeded in gaining control of the ministries of finance, industry, and defense and in replacing several key military officers with his supporters. In September 1936, Gömbös informed German officials that he would establish a Nazi-like, one-party government in Hungary within two years, but he died in October without realizing this goal.

In foreign affairs, Gömbös led Hungary towards close relations with Italy

and Germany

; in fact, Gömbös coined the term Axis, which was later adopted by the German-Italian military alliance. Soon after his appointment, Gömbös visited Italian dictator Benito Mussolini

and gained his support for revision of the Treaty of Trianon. Later, Gömbös became the first foreign head of government to visit German chancellor Adolf Hitler

. For a time, Hungary profited handsomely, as Gömbös signed a trade agreement with Germany that drew Hungary's economy out of depression but made Hungary dependent on the German economy for both raw materials and markets. In 1928, Germany had accounted for 19.5 percent of Hungary's imports and 11.7 percent of its exports; by 1939 the figures were 52.5 percent and 52.2 percent, respectively. Hungary's annual rate of economic growth from 1934 to 1940 averaged 10.8 percent. The number of workers in industry doubled in the ten years after 1933, and the number of agricultural workers dropped below 50 percent for the first time in the country's history.

. In 1938, Hungary openly repudiated the treaty's restrictions on its armed forces

. With German help, Hungary extended its territory four times and doubled in size from 1938 to 1941, even fighting a short war with the newly created Slovakia. Hungary regained parts of southern Slovakia

in 1938, Carpatho-Ukraine

in 1939, northern Transylvania

in 1940, and parts of Vojvodina

in 1941.

Hitler

's assistance did not come without a price. After 1938, the Führer used promises of additional territories, economic pressure, and threats of military intervention to pressure the Hungarians into supporting his policies, including those related to Europe's Jews

, which encouraged Hungary's antisemites. The percentage of Jews in business, finance, and the professions far exceeded the percentage of Jews in the overall population. After the depression struck, antisemites made the Jews scapegoats for Hungary's economic plight.

Hungary's Jews suffered the first blows of this renewed anti-Semitism during the government of Gömbös's successor, Kálmán Darányi

, who fashioned a coalition of conservatives and reactionaries and dismantled Gömbös's political machine. After Horthy publicly dashed hopes of land reform, discontented right-wingers took to the streets denouncing the government and baiting the Jews. Darányi's government attempted to appease the anti-Semites and the Nazis by proposing and passing the first so-called Jewish Law, which set quotas limiting Jews to 20 percent of the positions in certain businesses and professions. The law failed to satisfy Hungary's anti-Semitic radicals, however, and when Darányi tried to appease them again, Horthy unseated him in 1938. The regent then appointed the ill-starred Béla Imrédy

, who drafted a second, harsher Jewish Law before political opponents forced his resignation in February 1939 by presenting documents showing that Imrédy's own grandfather was a Jew.

Imrédy's downfall led to Pál Teleki

Imrédy's downfall led to Pál Teleki

's return to the prime minister's office. Teleki dissolved some of the fascist parties but did not alter the fundamental policies of his predecessors. He undertook a bureaucratic reform and launched cultural and educational programs to help the rural poor. But Teleki also oversaw passage of the second Jewish Law, which broadened the definition of "Jewishness," cut the quotas on Jews permitted in the professions and in business, and required that the quotas be attained by the hiring of Gentiles or the firing of Jews.

By the June 1939 elections, Hungarian public opinion had shifted so far to the right that voters gave the Arrow Cross Party

–Hungary's equivalent of Germany's Nazi Party–the second highest number of votes. In September 1940, the Hungarian government allowed German troops

to transit the country on their way to Romania

, and on November 20, 1940, Teleki signed the Tripartite Pact

, which allied the country with Germany, Italy, and Japan

, and ensured Hungary's involvement in the Second World War.

, striking inequalities distinguished the distribution of wealth, power, privilege, and opportunity among social groups. The various social strata had different codes of behavior and distinctive dress, speech, and manners. Respect showed to persons varied according to the source of their wealth. Wealth derived from possession of land was valued more highly than that coming from trade

or banking. The country was predominantly rural, and landownership was the central factor in determining the status and prestige of most families. In some of the middle

and upper strata

of society, noble birth

was also an important criterion as was, in some cases, the holding of certain occupations. An intricate system of ranks and titles distinguished the various social stations. Hereditary titles designated the aristocracy

and gentry

. Persons who had achieved positions of eminence, whether or not they were of noble birth, often received nonhereditary titles from the state. The gradations of rank derived from titles had great significance in social intercourse and in the relations between the individual and the state. Among the rural population, which consisted largely of peasants and which made up the overwhelming majority of the country's people, distinctions derived from such factors as the size of a family's landholding; whether the family owned the land and hired help to work it, owned and worked the land itself, or worked for others; and family reputation. The prestige and respect accompanying landownership were evident in many facets of life in the countryside, from finely shaded modes of polite address, to special church seating, to selection of landed peasants to fill public offices.

Landowners, wealthy bankers, aristocrats and gentry, and various commercial leaders made up the elite. Together, these groups accounted for only 13 percent of the population. Between 10 and 18 percent of the population consisted of the petite bourgeoisie

and the petty gentry, various government officials, intellectuals, retail store owners, and well-to-do professionals. More than two-thirds of the remaining population lived in varying degrees of poverty. Their only real chance for upward mobility lay in becoming civil servants, but such advancement was difficult because of the exclusive nature of the education system. The industrial working class was growing, but the largest group remained the peasantry, most of whom had too little land or none at all.

Although the inter-war years witnessed considerable cultural and economic progress in the country, the social structure changed little. A great chasm remained between the gentry, both social and intellectual, and the rural "people." Jews held a place of prominence in the country's economic, social, and political life. They constituted the bulk of the middle class. They were well assimilated, worked in a variety of professions, and were of various political persuasions.

Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1946)

The Kingdom of Hungary also known as the Regency, existed from 1920 to 1946 and was a de facto country under Regent Miklós Horthy. Horthy officially represented the abdicated Hungarian monarchy of Charles IV, Apostolic King of Hungary...

from October 1918 to November 1940.

Hungarian Democratic Republic

On October 31, 1918, the Hungarian Democratic RepublicHungarian Democratic Republic

The Hungarian People's Republic was an independent republic proclaimed after the collapse of Austria-Hungary in 1918...

was created by revolution that started in Budapest

Budapest

Budapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

after the dissolution and break-up of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

at the end of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. The official proclamation of the republic was on November 16, 1918, and Mihály Károlyi

Mihály Károlyi

Count Mihály Ádám György Miklós Károlyi de Nagykároly was briefly Hungary's leader in 1918-19 during a short-lived democracy...

was named as the republic's Prime Minister. This event also marked the independence of Hungary which had been ruled by the Habsburg Monarchy

Habsburg Monarchy

The Habsburg Monarchy covered the territories ruled by the junior Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg , and then by the successor House of Habsburg-Lorraine , between 1526 and 1867/1918. The Imperial capital was Vienna, except from 1583 to 1611, when it was moved to Prague...

for several centuries.

The Hungarian Democratic Republic did not last long. Another revolution in 1919 marked the end of this state and the creation of a new communist state known as Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Hungarian Soviet Republic

Hungarian Communist Party

The Communist Party of Hungary , renamed Hungarian Communist Party in 1945, was founded on November 24, 1918, and was in power in Hungary briefly from March to August 1919 under Béla Kun and the Hungarian Soviet Republic. The communist government was overthrown by the Romanian Army and driven...

(HCP) to power was rapid. The party was organized in a Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

hotel on November 4, 1918, when a group of Hungarian prisoners of war and communist sympathizers formed a Central Committee and dispatched members to Hungary to recruit new members, propagate the party's ideas, and radicalize Károlyi

Mihály Károlyi

Count Mihály Ádám György Miklós Károlyi de Nagykároly was briefly Hungary's leader in 1918-19 during a short-lived democracy...

's government. By February 1919, the party numbered 30,000 to 40,000 members, including many unemployed ex-soldiers, young intellectuals, and Jews. In the same month, Béla Kun

Béla Kun

Béla Kun , born Béla Kohn, was a Hungarian Communist politician and a Bolshevik Revolutionary who led the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919.- Early life :...

was imprisoned for incitement to riot, but his popularity skyrocketed when a journalist reported that he had been beaten by the police. Kun emerged from jail triumphant when the Social Democrats handed power to a government of "People's Commissars," who proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic on March 21, 1919.

The communists wrote a temporary constitution

Constitution

A constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed. These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is...

guaranteeing freedom of speech

Freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is the freedom to speak freely without censorship. The term freedom of expression is sometimes used synonymously, but includes any act of seeking, receiving and imparting information or ideas, regardless of the medium used...

and assembly

Freedom of assembly

Freedom of assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue and defend common interests...

; free education, language and cultural rights to minorities

Demographics of Hungary

This article is about the demographic features of the population of Hungary, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.-Historical:...

; and other rights. It also provided for suffrage

Suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply the franchise, distinct from mere voting rights, is the civil right to vote gained through the democratic process...

for people over eighteen years of age except clergy

Clergy

Clergy is the generic term used to describe the formal religious leadership within a given religion. A clergyman, churchman or cleric is a member of the clergy, especially one who is a priest, preacher, pastor, or other religious professional....

, "former exploiters," and certain others. Single-list elections took place in April, but members of the parliament were selected indirectly by popularly elected committees. On June 25, Kun's government proclaimed a dictatorship of the proletariat

Dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist socio-political thought, the dictatorship of the proletariat refers to a socialist state in which the proletariat, or the working class, have control of political power. The term, coined by Joseph Weydemeyer, was adopted by the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in the...

, nationalized industrial and commercial enterprises, and socialized housing, transport, banking, medicine, cultural institutions, and all landholdings of more than 40.5 hectares. Kun undertook these measures even though the Hungarian communists were relatively few, and the support they enjoyed was based far more on their program to restore Hungary's borders than on their revolutionary agenda. Kun hoped that the Russian government would intervene on Hungary's behalf and that a worldwide workers' revolution

World revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class...

was imminent. In an effort to secure its rule in the interim, the communist government resorted to arbitrary violence. Revolutionary tribunals ordered about 590 executions, including some for "crimes against the revolution." The government also used "red terror

Red Terror

The Red Terror in Soviet Russia was the campaign of mass arrests and executions conducted by the Bolshevik government. In Soviet historiography, the Red Terror is described as having been officially announced on September 2, 1918 by Yakov Sverdlov and ended about October 1918...

" to expropriate grain from peasants. This violence and the regime's moves against the clergy also shocked many Hungarians.

In late May, Kun attempted to fulfill his promise to restore Hungary's borders

Greater Hungary (political concept)

Greater Hungary is the informal name of the territory of Hungary before the 1920 Treaty of Trianon. After 1920, between the two World Wars, the official political goal of the Hungary was to restore those borders. After World War II, Hungary abandoned this policy, and today it only remains a...

. The Hungarian Red Army marched northward and reoccupied part of Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

. Despite initial military success, however, Kun withdrew his troops about three weeks later when the French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

threatened to intervene. This concession shook his popular support. Kun then unsuccessfully turned the Hungarian Red Army on the Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

ns, who broke through Hungarian lines on July 30, occupied Budapest

Budapest

Budapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

, and ousted Kun's Soviet Republic on August 1, 1919. Kun fled first to Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

and then to the Russian SFSR, where he was executed during Stalin's purge

Great Purge

The Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated by Joseph Stalin from 1936 to 1938...

of foreign communists in the late 1930s.

Counterrevolution

A militantly anti-communist authoritarian government composed of military officers entered Budapest on the heels of the Romanians. A "white terrorWhite Terror (Hungary)

The White Terror in Hungary was a two-year period of repressive violence by counter-revolutionary soldiers, with the intent of crushing any vestige of Hungary’s brief Communist revolution. Many of its victims were Jewish.-Background:...

" ensued that led to the imprisonment, torture, and execution without trial of communists, socialists, Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

, leftist intellectuals, sympathizers with the Károlyi and Kun regimes, and others who threatened the traditional Hungarian political order that the officers sought to reestablish. Estimates placed the number of executions at approximately 5,000. In addition, about 75,000 people were jailed. In particular, the Hungarian right wing and the Romanian forces targeted Jews for retribution. Ultimately, the white terror forced nearly 100,000 people to leave the country, most of them socialists, intellectuals, and middle-class Jews.

Monarchy restored

In March 1920, Admiral Miklós HorthyMiklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya was the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary during the interwar years and throughout most of World War II, serving from 1 March 1920 to 15 October 1944. Horthy was styled "His Serene Highness the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary" .Admiral Horthy was an officer of the...

was named Regent

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

and Sándor Simonyi-Semadam

Sándor Simonyi-Semadam

Sándor Simonyi-Semadam was a Hungarian politician who served as prime minister for a few months in 1920. He signed the Trianon Peace Treaty after World War I on 4 June 1920. With this treaty Hungary lost a considerable amount of its area...

was named Prime Minister of the restored Kingdom of Hungary. Charles I of Austria (known as Charles IV, Karl IV, or IV. Károly in Hungary) was the last Emperor of Austria

Emperor of Austria

The Emperor of Austria was a hereditary imperial title and position proclaimed in 1804 by the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, a member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, and continually held by him and his heirs until the last emperor relinquished power in 1918. The emperors retained the title of...

and the last King of Hungary

King of Hungary

The King of Hungary was the head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1000 to 1918.The style of title "Apostolic King" was confirmed by Pope Clement XIII in 1758 and used afterwards by all the Kings of Hungary, so after this date the kings are referred to as "Apostolic King of...

. He was not asked to fill the vacant Hungarian throne.

The government of Horthy immediately declared null and void all laws and edicts passed by the Karolyi and Kun regimes, in effect renouncing the 1918 armistice. Horthy's authoritarianism and the violent anti-communist backlash resulted in interwar Hungary having one of the quietest political landscapes in Eastern Europe. Later on, when he wished to take out loans from the West, they pressured him into democratic reforms. Horthy only did as much as he absolutely had to, since the Western powers were geographically distant from Hungary and soon turned their attention to matters elsewhere.

Horthy appointed Pál Teleki

Pál Teleki

Pál Count Teleki de Szék was prime minister of Hungary from 19 July 1920 to 14 April 1921 and from 16 February 1939 to 3 April 1941. He was also a famous expert in geography, a university professor, a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and Chief Scout of the Hungarian Scout Association...

as Prime Minister in July 1920. His right-wing government set quotas effectively limiting admission of Jews to universities, legalized capital punishment, and to quiet rural discontent, took initial steps towards fulfilling a promise of major land reform by dividing about 385,000 hectares from the largest estates into smallholdings. Teleki's government resigned, however, after the former Austrian Emperor, Charles IV, unsuccessfully attempted to retake Hungary's throne in March 1921. King Charles' return split parties between conservatives who favored a Habsburg

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg , also found as Hapsburg, and also known as House of Austria is one of the most important royal houses of Europe and is best known for being an origin of all of the formally elected Holy Roman Emperors between 1438 and 1740, as well as rulers of the Austrian Empire and...

restoration and nationalist right-wing radicals who supported election of a Hungarian king. István Bethlen

István Bethlen

Count István Bethlen de Bethlen was a Hungarian aristocrat and statesman and served as Prime Minister from 1921 to 1931....

, a nonaffiliated, right-wing member of the parliament, took advantage of this rift by convincing members of the Christian National Union who opposed Karl's re-enthronement to merge with the Smallholders' Party and form a new Party of Unity with Bethlen as its leader. Horthy then appointed Bethlen Prime Minister.

As Prime Minister, Bethlen dominated Hungarian politics between 1921 and 1931. He fashioned a political machine by amending the electoral law, eliminating peasants from the Party of Unity, providing jobs in the bureaucracy to his supporters, and manipulating elections in rural areas. Bethlen restored order to the country by giving the radical counter-revolutionaries payoffs and government jobs in exchange for ceasing their campaign of terror against Jews and leftists. In 1921, Bethlen made a deal with the Social Democrats and trade unions, agreeing, among other things, to legalize their activities and free political prisoners in return for their pledge to refrain from spreading anti-Hungarian propaganda, calling political strikes, and organizing the peasantry. In May 1922, the Party of Unity captured a large parliamentary majority. Charles IV's death, soon after he failed a second time to reclaim the throne in October 1921, allowed the revision of the Treaty of Trianon

Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon was the peace agreement signed in 1920, at the end of World War I, between the Allies of World War I and Hungary . The treaty greatly redefined and reduced Hungary's borders. From its borders before World War I, it lost 72% of its territory, which was reduced from to...

to rise to the top of Hungary's political agenda. Bethlen's strategy to win the treaty's revision was first to strengthen his country's economy and then to build relations with stronger nations that could further Hungary's goals. Revision of the treaty had such a broad backing in Hungary that Bethlen used it, at least in part, to deflect criticism of his economic, social, and political policies. However, Bethlen's only foreign policy success was a treaty of friendship with Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

in 1927, which had little immediate impact.

Postwar political and economic conditions

In 1920 and 1921, internal chaos racked Hungary. The white terror continued to plague Jews and leftists, unemployment and inflation soared, and penniless Hungarian refugees poured across the border from neighboring countries and burdened the floundering economy. The government offered the population little succor. In January 1920, Hungarian men and women cast the first secret ballots in the country's political history and elected a large counterrevolutionary and agrarian majority to a unicameral parliament. Two main political parties emerged: the socially conservative Christian National Union and the Independent Smallholders' PartyCivic Freedom Party

The Civic Freedom Party was the last name of one of the two interbellum liberal parties in Hungary.The party was founded in 1921 by Károly Rassay as the Independence Party of Smallholders, Workers and Citizens as an attempt to mobilize voters for liberalism outside the cities...

, which advocated land reform. In March, the parliament annulled both the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713

Pragmatic Sanction of 1713

The Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 was an edict issued by Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI to ensure that the throne of the Archduchy of Austria could be inherited by a daughter....

and the Compromise of 1867, and it restored the Hungarian monarchy but postponed electing a king until civil disorder had subsided. Instead, Admiral Miklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya was the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary during the interwar years and throughout most of World War II, serving from 1 March 1920 to 15 October 1944. Horthy was styled "His Serene Highness the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary" .Admiral Horthy was an officer of the...

— a former commander in chief of the Austro-Hungarian navy—was elected regent

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

and was empowered, among other things, to appoint Hungary's prime minister, veto legislation, convene or dissolve the parliament, and command the armed forces.

Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon was the peace agreement signed in 1920, at the end of World War I, between the Allies of World War I and Hungary . The treaty greatly redefined and reduced Hungary's borders. From its borders before World War I, it lost 72% of its territory, which was reduced from to...

on June 4, 1920, ratified the country's dismemberment, limited the size of its armed forces, and required reparations payments. The territorial provisions of the treaty, which ensured continued discord between Hungary and its neighbors, required the Hungarians to surrender more than two-thirds of their prewar lands. Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

acquired Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

; Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia refers to three political entities that existed successively on the western part of the Balkans during most of the 20th century....

gained Croatia

Croatia

Croatia , officially the Republic of Croatia , is a unitary democratic parliamentary republic in Europe at the crossroads of the Mitteleuropa, the Balkans, and the Mediterranean. Its capital and largest city is Zagreb. The country is divided into 20 counties and the city of Zagreb. Croatia covers ...

, Slavonia

Slavonia

Slavonia is a geographical and historical region in eastern Croatia...

, and Vojvodina

Vojvodina

Vojvodina, officially called Autonomous Province of Vojvodina is an autonomous province of Serbia. Its capital and largest city is Novi Sad...

; Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

became a part of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

; and Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

also acquired a small piece of pre-war Hungarian territory. Hungary also lost about 60 percent of its pre-war population, and about one-third of the 10 million ethnic Hungarians found themselves outside the diminished homeland. The country's ethnic composition was left almost homogeneous. Hungarians constituted about 90 percent of the population

Demographics of Hungary

This article is about the demographic features of the population of Hungary, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.-Historical:...

, Germans made up about 6 to 8 percent, and Slovaks, Croats, Romanians, Jews, and other minorities accounted for the remainder.

New international borders separated Hungary's industrial base from its sources of raw materials and its former markets for agricultural and industrial products. Its new circumstances forced Hungary to become a trading nation. Hungary lost 84 percent of its timber resources, 43 percent of its arable land, and 83 percent of its iron ore. Because most of the country's prewar industry was concentrated near Budapest, Hungary retained about 51 percent of its industrial population, 56 percent of its industry, 82 percent of its heavy industry, and 70 percent of its banks.

Economic development

When Bethlen took office, the government was all-but-bankrupt. Tax revenues were so paltry that he turned to domestic gold and foreign-currency reserves to meet about half of the 1921-22 budget and almost 80 percent of the 1922-23 budget. To improve his country's economic circumstances, Bethlen undertook development of industry. He imposed tariffs on finished goods and earmarked the revenues to subsidize new industries. Bethlen squeezed the agricultural sector to increase cereal exports, which generated foreign currency to pay for imports critical to the industrial sector. Further compounding Hungary's problems was the fact that of its four neighbors, three (Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia) were enemies and kept troops stationed on their borders at all times, even though Hungary had an army of only 20,000 men. The fourth, Austria, was a struggling nation and little more than an economic competitor. In 1924, after the white terror had waned and Hungary had gained admission to the League of NationsLeague of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

(1922), the Bethlen government was able to borrow a 50 million USD loan from the League, which in order to protect its investment placed the country in effective receivership, even placing an American banker, Jeremiah Smith, in charge of the country's finances. Hungary's outcast status had prevented it from obtaining any foreign aid in the immediate postwar period, but by the middle of the 1920s, the British decided to extend the hand of friendship to the losers of World War I. Hungary also obtained sympathy from the United States and Mussolini's Italy. Meanwhile, France and Hungary's neighbors vigorously objected.

By the late 1920s, Bethlen's policies had brought order to the economy. The number of factories increased by about 66 percent, inflation subsided, and the national income climbed 20 percent. However, the apparent stability was supported by a rickety framework of constantly revolving foreign credits and high world grain prices; therefore, Hungary remained undeveloped in comparison with the wealthier western Europe

Western Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

an countries, as most of the foreign loans went for non-productive purposes such as graft, expanding bureaucracy, and monumental public works projects. Agricultural products were subject to unstable prices and the vagaries of the weather. Furthermore, tariffs were commonplace in America and Europe during the 1920s, which frequently made it difficult to export. Hungary was no exception and liberally employed trade barriers to protect its manufacturing base. Exports also had to pass through Hungary's neighbors to reach the West, and as noted above, all but one was hostile.

Despite economic progress, the workers' standard of living remained poor, and consequently the working class never gave Bethlen its political support. The labor movement had never developed in pre-WWI Hungary the way it did in Austria, and the Horthy government remained resolutely opposed to organized labor or social reforms. There was no minimum wage or any sort of labor laws in Hungary almost until the start of World War II, and wages were further undercut by peasants flocking into Budapest who were willing to work for almost nothing. On the whole, workers fared more poorly in interwar Hungary then they had before World War I. The peasants were even worse off than the working class. In the 1920s, about 60 percent of the peasants were either landless or were cultivating plots too small to provide a decent living. Real wages for agricultural workers remained below prewar levels, and the peasants had practically no political voice. Moreover, once Bethlen had consolidated his power, he ignored calls for land reform. The industrial sector failed to expand fast enough to provide jobs for all the peasants and university graduates seeking work. Most peasants lingered in the villages, and in the 1930s Hungarians in rural areas were extremely dissatisfied. Hungary's foreign debt ballooned as Bethlen expanded the bureaucracy to absorb the university graduates who, if left idle, might have threatened civil order. This was because Hungary, like the rest of Eastern Europe, had an educational system primarily focused on the liberal arts and law rather than science, engineering, or other practical subjects that might have helped the country's development. University graduates mostly sought employment in the bureaucracy, where they were guaranteed an easy, secure job. When they could not obtain work, either because they lacked useful skills or because the swollen bureaucracy had no openings available, they would invariably blame their bad luck on Jews. This would contribute to an anti-Semitism in Hungary that would ultimately have tragic consequences.

Following the Wall Street Crash of 1929

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 , also known as the Great Crash, and the Stock Market Crash of 1929, was the most devastating stock market crash in the history of the United States, taking into consideration the full extent and duration of its fallout...

in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and the beginning of the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

, world grain prices plummeted, and the framework supporting Hungary's economy

Economy of Hungary

The economy of Hungary is a medium-sized, structurally, politically and institutionally open economy in Central Europe and is part of the European Union's single market...

buckled. Hungary's earnings from grain exports declined as prices and volume dropped, tax revenues fell, foreign credit sources dried up, and short-term loans were called in. The Hungarian national bank depleted its supply of precious metals and foreign currency during a period of a few weeks in 1931. Hungary sought financial relief from the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

, which insisted on a program of rigid fiscal belt-tightening, resulting in increased unemployment. The peasants reverted to subsistence farming. Industrial production rapidly dropped, and businesses went bankrupt as domestic and foreign demand evaporated. Government workers lost their jobs or suffered severe pay cuts. By 1933 about 18 percent of Budapest's citizens lived in poverty. Unemployment leaped from 5 percent in 1928 to almost 36 percent by 1933.

Shift to the right

As the standard of living dropped, the political mood of the country shifted further towards the rightRight-wing politics

In politics, Right, right-wing and rightist generally refer to support for a hierarchical society justified on the basis of an appeal to natural law or tradition. To varying degrees, the Right rejects the egalitarian objectives of left-wing politics, claiming that the imposition of equality is...

. Bethlen resigned without warning amid national turmoil in August 1931. His successor, Gyula Károlyi

Gyula Károlyi

Gyula Count Károlyi de Nagykároly was a conservative Hungarian politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 1931 to 1932. He had previously been Prime Minister of the counter-revolutionary government in Szeged for several months in 1919...

, failed to quell the crisis. Horthy

Miklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya was the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary during the interwar years and throughout most of World War II, serving from 1 March 1920 to 15 October 1944. Horthy was styled "His Serene Highness the Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary" .Admiral Horthy was an officer of the...

then appointed a reactionary demagogue, Gyula Gömbös

Gyula Gömbös

Gyula Gömbös de Jákfa was the conservative prime minister of Hungary from 1932 to 1936.-Background:Gömbös was born in the Tolna County village of Murga, Hungary, which had a mixed Hungarian and ethnic German population. His father was the village schoolmaster. The family belonged to the ...

, but only after Gömbös agreed to maintain the existing political system, to refrain from calling elections before the parliament's term had expired, and to appoint several Bethlen supporters to head key ministries. Gömbös publicly renounced the vehement antisemitism he had espoused earlier, and his party and government included some Jews

History of the Jews in Hungary

Hungarian Jews have existed since at least the 11th century. After struggling against discrimination throughout the Middle Ages, by the early 20th century the community grew to be 5% of Hungary's population , and were prominent in science, the arts and business...

.

Gömbös's appointment marked the beginning of the radical right

Radical Right

Radical Right is a generally pejorative term used to describe various political movements on the right that are conspiracist, attuned to anti-American or anti-Christian agents of foreign powers, and "politically radical." The term was first used by social scientists in the 1950s regarding small...

's ascendancy in Hungarian politics, which lasted with few interruptions until 1945. The radical right garnered its support from medium and small farmers, former refugees from Hungary's lost territories, and unemployed civil servants, army officers, and university graduates. Gömbös advocated a one-party government, revision of the Treaty of Trianon

Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon was the peace agreement signed in 1920, at the end of World War I, between the Allies of World War I and Hungary . The treaty greatly redefined and reduced Hungary's borders. From its borders before World War I, it lost 72% of its territory, which was reduced from to...

, withdrawal from the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

, anti-intellectualism, and social reform. He assembled a political machine, but his efforts to fashion a one-party state and fulfill his reform platform were frustrated by a parliament composed mostly of Bethlen's supporters and by Hungary's creditors, who forced Gömbös to follow conventional policies in dealing with the economic and financial crisis. The 1935 elections gave Gömbös more solid support in the parliament, and he succeeded in gaining control of the ministries of finance, industry, and defense and in replacing several key military officers with his supporters. In September 1936, Gömbös informed German officials that he would establish a Nazi-like, one-party government in Hungary within two years, but he died in October without realizing this goal.

In foreign affairs, Gömbös led Hungary towards close relations with Italy

Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

The Kingdom of Italy was a state forged in 1861 by the unification of Italy under the influence of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which was its legal predecessor state...

and Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

; in fact, Gömbös coined the term Axis, which was later adopted by the German-Italian military alliance. Soon after his appointment, Gömbös visited Italian dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

and gained his support for revision of the Treaty of Trianon. Later, Gömbös became the first foreign head of government to visit German chancellor Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

. For a time, Hungary profited handsomely, as Gömbös signed a trade agreement with Germany that drew Hungary's economy out of depression but made Hungary dependent on the German economy for both raw materials and markets. In 1928, Germany had accounted for 19.5 percent of Hungary's imports and 11.7 percent of its exports; by 1939 the figures were 52.5 percent and 52.2 percent, respectively. Hungary's annual rate of economic growth from 1934 to 1940 averaged 10.8 percent. The number of workers in industry doubled in the ten years after 1933, and the number of agricultural workers dropped below 50 percent for the first time in the country's history.

On the eve of World War II

The Kingdom of Hungary also used its relationship with Germany to chip away at the Treaty of TrianonTreaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon was the peace agreement signed in 1920, at the end of World War I, between the Allies of World War I and Hungary . The treaty greatly redefined and reduced Hungary's borders. From its borders before World War I, it lost 72% of its territory, which was reduced from to...

. In 1938, Hungary openly repudiated the treaty's restrictions on its armed forces

Military of Hungary

The Hungarian Defence Force is the national military of Hungary. It currently has two branches, the Hungarian Ground Force and the Hungarian Air Force....

. With German help, Hungary extended its territory four times and doubled in size from 1938 to 1941, even fighting a short war with the newly created Slovakia. Hungary regained parts of southern Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

in 1938, Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine

Carpatho-Ukraine was an autonomous region within Czechoslovakia from late 1938 to March 15, 1939. It declared itself an independent republic on March 15, 1939, but was occupied by Hungary between March 15 and March 18, 1939, remaining under Hungarian control until the Nazi occupation of Hungary in...

in 1939, northern Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

in 1940, and parts of Vojvodina

Vojvodina

Vojvodina, officially called Autonomous Province of Vojvodina is an autonomous province of Serbia. Its capital and largest city is Novi Sad...

in 1941.

Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

's assistance did not come without a price. After 1938, the Führer used promises of additional territories, economic pressure, and threats of military intervention to pressure the Hungarians into supporting his policies, including those related to Europe's Jews

History of the Jews in Europe

Judaism in Europe has a long history, beginning with the conquest of the Eastern Mediterranean by Pompey in 63 BCE, thus beginning the History of the Jews in the Roman Empire, though likely Alexandrian Jews had migrated to Rome slightly before Pompey's conquest of the East.The pre-World War...

, which encouraged Hungary's antisemites. The percentage of Jews in business, finance, and the professions far exceeded the percentage of Jews in the overall population. After the depression struck, antisemites made the Jews scapegoats for Hungary's economic plight.

Hungary's Jews suffered the first blows of this renewed anti-Semitism during the government of Gömbös's successor, Kálmán Darányi

Kálmán Darányi

Kálmán Darányi de Pusztaszentgyörgy et Tetétlen was a Hungarian politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 1936 to 1938. He also served as Speaker of the House of Representatives of Hungary from 5 December 1938 to 12 June 1939 and from 15 June 1939 to 1 November 1939...

, who fashioned a coalition of conservatives and reactionaries and dismantled Gömbös's political machine. After Horthy publicly dashed hopes of land reform, discontented right-wingers took to the streets denouncing the government and baiting the Jews. Darányi's government attempted to appease the anti-Semites and the Nazis by proposing and passing the first so-called Jewish Law, which set quotas limiting Jews to 20 percent of the positions in certain businesses and professions. The law failed to satisfy Hungary's anti-Semitic radicals, however, and when Darányi tried to appease them again, Horthy unseated him in 1938. The regent then appointed the ill-starred Béla Imrédy

Béla Imrédy

Béla vitéz Imrédy de Ómoravicza was Prime Minister of Hungary from 1938 to 1939....

, who drafted a second, harsher Jewish Law before political opponents forced his resignation in February 1939 by presenting documents showing that Imrédy's own grandfather was a Jew.

Pál Teleki

Pál Count Teleki de Szék was prime minister of Hungary from 19 July 1920 to 14 April 1921 and from 16 February 1939 to 3 April 1941. He was also a famous expert in geography, a university professor, a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and Chief Scout of the Hungarian Scout Association...

's return to the prime minister's office. Teleki dissolved some of the fascist parties but did not alter the fundamental policies of his predecessors. He undertook a bureaucratic reform and launched cultural and educational programs to help the rural poor. But Teleki also oversaw passage of the second Jewish Law, which broadened the definition of "Jewishness," cut the quotas on Jews permitted in the professions and in business, and required that the quotas be attained by the hiring of Gentiles or the firing of Jews.

By the June 1939 elections, Hungarian public opinion had shifted so far to the right that voters gave the Arrow Cross Party

Arrow Cross Party

The Arrow Cross Party was a national socialist party led by Ferenc Szálasi, which led in Hungary a government known as the Government of National Unity from October 15, 1944 to 28 March 1945...

–Hungary's equivalent of Germany's Nazi Party–the second highest number of votes. In September 1940, the Hungarian government allowed German troops

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

to transit the country on their way to Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

, and on November 20, 1940, Teleki signed the Tripartite Pact

Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also the Three-Power Pact, Axis Pact, Three-way Pact or Tripartite Treaty was a pact signed in Berlin, Germany on September 27, 1940, which established the Axis Powers of World War II...

, which allied the country with Germany, Italy, and Japan

Showa period

The , or Shōwa era, is the period of Japanese history corresponding to the reign of the Shōwa Emperor, Hirohito, from December 25, 1926 through January 7, 1989.The Shōwa period was longer than the reign of any previous Japanese emperor...

, and ensured Hungary's involvement in the Second World War.

Social structure

Until World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, striking inequalities distinguished the distribution of wealth, power, privilege, and opportunity among social groups. The various social strata had different codes of behavior and distinctive dress, speech, and manners. Respect showed to persons varied according to the source of their wealth. Wealth derived from possession of land was valued more highly than that coming from trade

Trade

Trade is the transfer of ownership of goods and services from one person or entity to another. Trade is sometimes loosely called commerce or financial transaction or barter. A network that allows trade is called a market. The original form of trade was barter, the direct exchange of goods and...

or banking. The country was predominantly rural, and landownership was the central factor in determining the status and prestige of most families. In some of the middle

Middle class

The middle class is any class of people in the middle of a societal hierarchy. In Weberian socio-economic terms, the middle class is the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the working class and upper class....

and upper strata

Upper class

In social science, the "upper class" is the group of people at the top of a social hierarchy. Members of an upper class may have great power over the allocation of resources and governmental policy in their area.- Historical meaning :...

of society, noble birth

Nobility

Nobility is a social class which possesses more acknowledged privileges or eminence than members of most other classes in a society, membership therein typically being hereditary. The privileges associated with nobility may constitute substantial advantages over or relative to non-nobles, or may be...

was also an important criterion as was, in some cases, the holding of certain occupations. An intricate system of ranks and titles distinguished the various social stations. Hereditary titles designated the aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

and gentry

Gentry

Gentry denotes "well-born and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past....

. Persons who had achieved positions of eminence, whether or not they were of noble birth, often received nonhereditary titles from the state. The gradations of rank derived from titles had great significance in social intercourse and in the relations between the individual and the state. Among the rural population, which consisted largely of peasants and which made up the overwhelming majority of the country's people, distinctions derived from such factors as the size of a family's landholding; whether the family owned the land and hired help to work it, owned and worked the land itself, or worked for others; and family reputation. The prestige and respect accompanying landownership were evident in many facets of life in the countryside, from finely shaded modes of polite address, to special church seating, to selection of landed peasants to fill public offices.

Landowners, wealthy bankers, aristocrats and gentry, and various commercial leaders made up the elite. Together, these groups accounted for only 13 percent of the population. Between 10 and 18 percent of the population consisted of the petite bourgeoisie

Petite bourgeoisie

Petit-bourgeois or petty bourgeois is a term that originally referred to the members of the lower middle social classes in the 18th and early 19th centuries...

and the petty gentry, various government officials, intellectuals, retail store owners, and well-to-do professionals. More than two-thirds of the remaining population lived in varying degrees of poverty. Their only real chance for upward mobility lay in becoming civil servants, but such advancement was difficult because of the exclusive nature of the education system. The industrial working class was growing, but the largest group remained the peasantry, most of whom had too little land or none at all.

Although the inter-war years witnessed considerable cultural and economic progress in the country, the social structure changed little. A great chasm remained between the gentry, both social and intellectual, and the rural "people." Jews held a place of prominence in the country's economic, social, and political life. They constituted the bulk of the middle class. They were well assimilated, worked in a variety of professions, and were of various political persuasions.