History of the Puritans in North America

Encyclopedia

In the early 17th century, thousands of English

Puritans settled in North America

, mainly in New England

. Puritans were generally members of the Church of England

who believed the Church of England was insufficiently Reformed

and who therefore opposed royal ecclesiastical policy under Elizabeth I of England

, James I of England

, and Charles I of England

. Most Puritans were "non-separating Puritans", meaning they did not advocate setting up separate congregations distinct from the Church of England; a small minority of Puritans were "separating Puritans" who advocated setting up congregations outside the Church. One Separatist group, the Pilgrims, established the Plymouth Colony

in 1620. Non-separating Puritans played leading roles in establishing the Massachusetts Bay Colony

in 1629 and the Connecticut Colony

in 1636. The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

was established by settlers expelled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony because of their unorthodox religious opinions. Puritans were also active in the New Hampshire

before it became a crown colony in 1691.

Most Puritans who migrated to North America came in the decade 1630-1640 in what is known as the Great Migration. See the main articles on each of the colonies for information on their political and social history; this article focuses on the religious history of the Puritans in North America.

The early seventeenth century saw the foundation of many joint stock companies, which were commercial ventures designed to profit from trade or the foundation of colonial settlements. In 1606, King James issued a royal charter

to two companies referred to collectively as the Virginia Company

: the London Company

and the Plymouth Company

. While the Virginia Company successfully established the Colony of Virginia in 1608, the Plymouth Company

was initially unsuccessful in its settlements, which explains their interest in granting a patent to the Pilgrims in 1620.

Two of the Pilgrim settlers in Plymouth Colony – Robert Cushman

and Edward Winslow

– believed that Cape Ann

would be a profitable location for a settlement. They therefore organized a company which they named the Dorchester Company and in 1622 sailed to England seeking a patent from the London Company giving them permission to settle there. They were successful and were granted the Sheffield Patent

(named after Edmund Sheffield, 3rd Baron Sheffield, the member of the Plymouth Company who granted the patent). On the basis of this patent, Roger Conant led a group of fishermen to found Salem

in 1626, being replaced as governor by John Endecott

in 1627. During their time in England, Cushman and Winslow convinced Puritan members of the landed gentry

to invest in the Dorchester Company.

in the Virginia Colony, beginning in 1618 with Christopher Lawne

who established a plantation at Lawne's Creek. He died the following year, but several other prominent Puritan merchants soon emigrated there, including the Bennett family of Somerset. Under the leadership of Richard Bennett

, the community moved from Warrascoyack to neighboring Nansemond beginning in 1635, then sought temporary refuge in Maryland in 1648. They returned to Virginia when the "Roundheads" appointed Bennett as governor there in 1652; later, in 1672, all of them, including Bennett, converted to the Quaker faith upon meeting its founder, George Fox

.

A more famous group of these early Puritans had also settled in New England

A more famous group of these early Puritans had also settled in New England

in 1620: the Pilgrims

.

The Pilgrims were Separatists who held views similar to those proclaimed by Robert Browne, John Greenwood, and Henry Barrowe

. The Pilgrims emerged in Elizabethan England at roughly the same time as the Brownists.

The Pilgrims trace their lineage to Richard Clyfton

, minister of Babworth

, Nottinghamshire

. Beginning in the 1580s, Clyfton advocated separation from the Church of England. Clyfton's movement attracted William Brewster

, the postmaster

of Scrooby

. Tobias Matthew

, the Bishop of Durham, who had been part of Archbishop Whitgift's delegation at the Hampton Court Conference, was selected by James to become Archbishop of York

in 1606. He led an anti-Separatist crackdown and Clyfton was removed from his ministry. In response, Brewster offered to organize a dissenting congregation in the manor house in which he lived in Scrooby. Clyfton served as the congregation's pastor, John Robinson

as its teacher, and William Brewster as its chief elder. This congregation was subject to ecclesiastical investigation, and its members faced social hostility from conforming church members, but was not actively persecuted. Nevertheless, disliking the social hostility, and fearing future persecution, the group decided to leave England.

150 members of the congregation made it to Amsterdam

, where they met up with a group of Separatist exiles led by John Smyth

, which had joined the congregation of English exiles led by Francis Johnson

. After a year at Amsterdam, tensions between Smyth and Johnson grew so high, that the Pilgrims decided to move to Leiden. While there, many worked at Leiden University

or in the textile, printing and brewing trades. John Robinson participated in the Calvinist-Arminian Controversy

while at Leiden University, arguing on behalf of the Gomarists.

By 1617, many members of the congregation had grown disillusioned with Leiden and wanted to move somewhere where they could retain their English identity, while also worshipping God in the way they believed was required. As such, the congregation voted to leave Leiden and to found a colony. The group ultimately decided to move to New England

By 1617, many members of the congregation had grown disillusioned with Leiden and wanted to move somewhere where they could retain their English identity, while also worshipping God in the way they believed was required. As such, the congregation voted to leave Leiden and to found a colony. The group ultimately decided to move to New England

. In 1620, after receiving a patent

from the London Company

, the Pilgrims left for New England onboard the Mayflower

, landing at Plymouth Rock

. The colony founded by the Pilgrims was called Plymouth Colony

.

, the Catholic daughter of Henry IV of France

(thus cementing an alliance with France in preparation for war against Spain). As such, at this parliament, Puritan MPs openly worried that Charles was preparing to restrict the recusancy

laws (which Charles was, in fact, planning on doing, having agreed to do so in the secret marriage treaty he negotiated with Louis XIII of France

).

Puritan MP John Pym

Puritan MP John Pym

launched an attack on Richard Montagu in the House of Commons. As a response, Montagu wrote a pamphlet entitled Appello Caesarem (Latin

"I Appeal to Caesar") (a reference to Acts 25:10-12), in which he appealed to Charles to protect him against the Puritans. Charles responded by making Montagu a royal chaplain, signaling that he was willing to defend Montagu against Puritan opposition.

In this atmosphere, Puritan suspicions that Charles was secretly planning to restore Roman Catholicism in England mounted. As such, the Parliament, heavily influenced by its Puritan members, was reluctant to grant Charles revenue, since they feared that any revenue granted might be used to support an army that would re-impose Catholicism on England. For example, since 1414, every English monarch had been authorized by their first Parliament to collect the customs duties of Tonnage and Poundage

for the duration of their reign; the 1625 Parliament, however, voted to allow Charles to collect Tonnage and Poundage for only one year. Furthermore, when Charles wanted to intervene in the Thirty Years' War by declaring war on Spain, Parliament granted him only £140,000, a totally insufficient sum to pursue the war.

The war with Spain went ahead (partially funded by tonnage and poundage collected by Charles even after he was no longer authorized to do so). Buckingham was put in charge of the war effort, and failed miserably. As such, in 1628, Parliament called for Buckingham's replacement, but Charles stuck by Buckingham. Parliament went on to pass the Petition of Right

, a declaration of Parliament's rights. Charles accepted the Petition, though this did not lead to a change in his behaviour.

In August 1628, Buckingham was assassinated by a disillusioned soldier, John Felton

. The nation responded with spontaneous celebration, which angered Charles.

When Parliament resumed sitting in January 1629, Charles was met with outrage over the case of John Rolle, an MP who had been prosecuted for failing to pay Tonnage and Poundage even though Charles had agreed to "no taxation without representation

" (to use a slogan from a later era) in the Petition of Right. John Finch

, the Speaker of the House of Commons

, was famously held down in the Speaker's Chair in order to allow the House to pass a resolution condemning the king.

Charles was so outraged by Parliament's opposition to his policies that he determined to rule without ever calling a parliament again, thus initiating the period known as his Personal Rule

(1629–1640), which his enemies termed the Eleven Years' Tyranny. This period also saw the ascendancy of Laudianism in England (see previous section), which led Puritan critics to term this period the Caroline Captivity of the Church (a reference to the so-called Babylonian Captivity of the Church, which was itself a reference to the Babylonian Captivity

).

to two companies referred to collectively as the Virginia Company

: the London Company

(which successfully established the Colony of Virginia in 1608) and the Plymouth Company

(which was unsuccessful at establishing settlements, which explains why they were eager to grant a patent to the Pilgrims in 1620).

Two of the Pilgrim settlers in Plymouth Colony - Robert Cushman

and Edward Winslow

- believed that Cape Ann

would be a profitable location for a settlement. They therefore organized a company which they named the Dorchester Company and in 1622 sailed to England seeking a patent from the London Company giving them permission to settle there. They were successful and were granted the Sheffield Patent

(named after Edmond, Lord Sheffield, the member of the Plymouth Company who granted the patent). On the basis of this patent, Roger Conant led a group of fishermen to found Salem

in 1626, being replaced as governor by John Endecott

in 1627. The Pilgrims went to New England for a freedom of religion.

During their time in England, Cushman and Winslow had convinced many Puritan members of the landed gentry

to invest in the Dorchester Company. In 1627, the Dorchester Company went bankrupt, but was succeeded by the New England Company (the membership of the Dorchester and New England Companies overlapped). The New England Company sought clearer title to the New England land of the proposed settlement than provided by the Sheffield Patent and in March 1629 succeeded in obtaining from King Charles a royal charter

changing the name of the company to the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England and granting them the land to found the Massachusetts Bay Colony

. It is unclear why Charles agreed to this, but it would appear that he did not realize that the group was dominated by Puritans and believed that it was a purely commercial company.

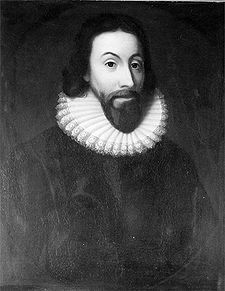

As the Puritans' relationship with the new king soured, Puritan John Winthrop

As the Puritans' relationship with the new king soured, Puritan John Winthrop

, a lawyer who had practiced in the Court of Wards, began to explore the idea of creating a Puritan colony in New England. After all, the Pilgrims at Plymouth Colony had proven that such a colony was viable. Instead of living in England under the rule of a king hostile to their interests, the Puritans could establish a colony in New England far from the king's interference. Throughout 1628 and 1629, Puritans in Winthrop's social circle discussed the possibility of moving to New England. It was noted that the royal charter establishing the Massachusetts Bay Company had not specified where the company's annual meeting should be held; this raised the possibility that the governor of the company could move to the new colony and serve as governor of the colony, while the general court of the company could be transformed into the colony's legislative assembly. John Winthrop participated in these discussions and in March 1629, signed the Cambridge Agreement, by which the non-emigrating shareholders of the company agreed to turn over control of the company to the emigrating shareholders. As Winthrop was the wealthiest of the emigrating shareholders, the company decided to make him governor, and entrusted him with the company charter.

Winthrop sailed for New England in 1630 along with 700 colonists on board eleven ships known collectively as the Winthrop Fleet

. Winthrop himself sailed on board the Arbella

. During the crossing, he preached a sermon entitled "A Model of Christian Charity", in which he called on his fellow settlers to make their new colony a City upon a Hill

(a reference to Matthew 5:14-16), meaning that they would be a model to all the nations of Europe as to what a properly reformed Christian commonwealth should look like. (This was particularly poignant in 1630, since the Thirty Years' War

was going bad for the Protestants and Catholicism was being restored in lands previously reformed - e.g. by the 1629 Edict of Restitution

.)

area. However, the Great Migration

of Puritans was relatively short-lived and not as large as is often believed. It began in earnest in 1629 with the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

and ended in 1642 with the start of the English Civil War when King Charles I

effectively shut off emigration to the colonies. Emigration was officially restricted to conforming churchmen in December 1634 by his Privy Council. From 1629 through 1643 approximately 21,000 Puritans emigrated to New England

The Great Migration of Puritans to New England was primarily an exodus of families. Between 1630 and 1640 over 13,000 men, women, and children sailed to Massachusetts

. The religious and political factors behind the Great Migration influenced the demographics

of the emigrants. Rather than groups of young men seeking economic success (as predominated Virginia colonies), Puritan ships were laden with “ordinary” people, old and young, families as well as individuals. Just a quarter of the emigrants were in their twenties when they boarded ship in the 1630s, making young adults a minority in New England settlements. The New World Puritan population was more of a cross section in age of English population than those of other colonies. This meant that the Massachusetts Bay Colony

retained a relatively “normal” population composition. In contrast to the colony in Virginia – where the ratio of colonist men to women was 4:1 in early decades and at least 2:1 in later decades, and where limited intermarriage with native women took place – nearly half of the Puritan immigrants to the New World were women, and there was little intermarriage with natives. The majority of families who traveled to Massachusetts Bay were families in progress, with parents who were not yet through with their reproductive years and whose continued fertility would make New England’s population growth possible. The women who emigrated were critical agents in the success of the establishment and maintenance of the Puritan colonies in North America. Success in the early colonial economy depended largely on labor, which was conducted by members of Puritan families. It was through this labor that Puritans endeavored to create their “city on a hill”, a productive, morally exemplary colony far from the corruption of the Church of England.

. Thus, although the Puritans in Massachusetts erected their church along Presbyterian-Congregational lines, they technically remained in full communion

with the Church of England. This position led to two major theological controversies with Separating Puritans in the course of the 1630s: the Roger Williams controversy, and the Anne Hutchinson controversy.

, a Separating Puritan minister, arrived in Boston

in 1631. He was almost immediately invited to become the pastor of the local congregation. Williams refused the invitation on the grounds that the congregation had not separated from the Church of England. He then attempted to become pastor of the church at Salem

, but was blocked by Boston political leaders, who objected to his separatism. He thus spent two years with his fellow Separatists in the Plymouth Colony, but ultimately came into conflict with them and returned to Salem. There, he became pastor in May 1635, against the objection of the Boston authorities. Williams set forth a manifesto in which he declared that 1) the Church of England was apostate and fellowship with it was a grievous sin; 2) the Massachusetts Colony's charter falsely said that King Charles was a Christian; 3) that the colony should not be allowed to impose oaths on its citizens because that was forbidden by Matthew 5:33-37

Williams' actions so outraged the Puritan leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony that they expelled him from the colony. In 1636, the exiled Williams founded the city of Providence, Rhode Island

. Williams was one of the first Puritans to advocate separation of church and state

and Rhode Island was one of the first places in the Christian world to recognize freedom of religion

.

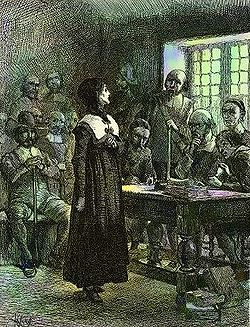

and her family moved from Boston, Lincolnshire

to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634, following their Puritan minister John Cotton. Cotton began pastoring a congregation in Boston, Massachusetts, and Hutchinson joined his congregation. Following the Puritan practice of conventicling, Hutchinson set up a conventicle in her home. At the conventicle, a group would meet during the week to discuss John Cotton's sermon from the previous Sunday. Hutchinson proved to be extremely charismatic at propounding on Cotton's ideas during these conventicles, and eventually the size of her conventicle swelled to 80 people and had to be moved from her home to the church building.

Cotton had long denounced Arminianism

in his sermons. Hutchinson took up the anti-Arminian cause in strong language, propounding an extreme form of double predestination (a view popularized among English Puritans by William Perkins), which held that God chose those who would go to heaven

(the elect

) and those who would go to hell

(the reprobate), and that His decision inevitably and infallibly came to pass. Applying this framework to the Arminian controversy, Hutchinson argued that people were either under a covenant of works (they were relying on good works

for their salvation, and therefore were really damned) or else a covenant of grace

(in which case they were dependent only on God

's grace

, and were therefore really saved

).

By 1637, Hutchinson's teachings had grown controversial within the colony for a number of reasons. First, some Puritans objected to a woman occupying such a prominent role as a teacher in the church. Second, Hutchinson began denouncing various Puritan ministers in the colony as really preaching a "covenant of works" and sometimes spoke as if John Cotton were the only minister in the entire colony who was preaching a "covenant of grace" correctly. Thirdly, some of Hutchinson's views on the "covenant of grace" seemed indistinguishable from the heresy

By 1637, Hutchinson's teachings had grown controversial within the colony for a number of reasons. First, some Puritans objected to a woman occupying such a prominent role as a teacher in the church. Second, Hutchinson began denouncing various Puritan ministers in the colony as really preaching a "covenant of works" and sometimes spoke as if John Cotton were the only minister in the entire colony who was preaching a "covenant of grace" correctly. Thirdly, some of Hutchinson's views on the "covenant of grace" seemed indistinguishable from the heresy

of antinomianism

, the view that the elect did not have to follow the laws of God or morality.

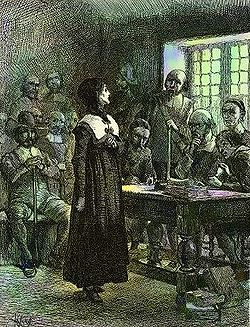

Hutchinson was called before the Massachusetts General Court

to explain herself. She sparred verbally with the magistrates successfully on a number of issues, but was ultimately undone when she said that she had determined that she would be persecuted when she came to New England. When the magistrates asked her how she had determined this, she responded "by an immediate revelation" i.e. God had spoken to her and told her so. The Puritans generally followed the principle of sola scriptura

and believed that God communicated with individuals only through the medium of scripture. As such, for the magistrates of the General Court, who were already suspicious of Hutchinson's orthodoxy, the claim that God was speaking directly to her was the final straw. They therefore voted to banish her from the colony. As a result, in 1638, Hutchinson and several of her followers left the Massachusetts Bay Colony and founded the town of Pocasset, which today is Portsmouth, Rhode Island

.

The struggle between the assertive Church of England and various Presbyterian and Puritan groups extended throughout the English realm in the 17th Century, prompting not only the re-emigration of British Protestants from Ireland to North America (the so-called Scotch-Irish), but prompting emigration from Bermuda

, England's second-oldest overseas territory. Roughly 10,000 Bermudians emigrated before US Independence. Most of these went to the American colonies, founding, or contributing to settlements throughout the South, especially. Many had also gone to the Bahamas, where a number of Bermudian Independent Puritan families, under the leadership of William Sayle

, had established the colony of Eleuthera

in 1648.

In the 1660s the Puritan settlements in the New World were confronted with the challenge posed by an aging first generation. Those who created the colonies were the most fervent in their religious beliefs, and as their numbers began to decline, so did the membership of churches. The demographics of the churches changed because fewer men were joining. The resulting decrease in male religious participation was a problem for the established church (that is, the colony’s official church for which people were taxed and which they were expected to attend), since men were the ones with secular power. If the men who wielded secular power in the colony were absent from the church, its legitimacy would be undermined. As early as 1660, women constituted the great majority of church members. However, since Anne Hutchinson

’s banishment, they were not allowed to talk in church (for more information, see below under "Beliefs"). Puritan ministers, concerned for the continued existence and power of their churches in the colonies, pushed for a solution to declining church membership. This effort led to the creation of the Halfway Covenant, in order to boost participation in the Puritan church.

Emigration resumed under the rule of Cromwell, but not in large numbers as there was no longer any need to "escape persecution" in England. In fact, many Puritans returned to England during the war. "In 1641, when the English Civil War began, some immigrants returned to fight on the Puritan side, and when the Puritans won, many resumed English life under Oliver Cromwell's more congenial Puritan sway."http://www.historynet.com/exploration/great_migrations/3035471.html?page=2&c=y

Some Puritans also migrated to colonies in Central America

and the Caribbean

, see Providence Island Company

, Mosquito Coast

and Providencia Island

.

preached to the Native Tribes of Massachusetts

. His goal was to convert as many Natives as possible. His plan was to move the converted Natives into Praying Towns

, were they could be brought into Puritan society but at a distance from the colonial villages. Many Europeans did not believe that the Natives had a civilized culture because they used oral traditions to pass on their heritage as opposed to the written history of Europe. John Eliot was quoted as saying “As for these poore Indians, they have no principles of their own, nor yet wisdom of their own.”

A missionary criticized Eliot’s attitude by saying, “He did not so unto Indians, but brought them into his towns, civilizing them that they might be Christianized.”

Conflicts arose between the Native Americans and English during the time of these praying towns, the greatest of these being King Philip’s War. After this war many of the towns were disbanded as a way to protect the Puritans living in the area. According to William Wood

, tribes were seen as “scumme of the country…if not for the English.” Warfare was not the only “war” raging between the peoples of Massachusetts, disease was on a rise as well. Plagues of diseases and parasites thrived in the new land and on the Natives. Tribes such as the Pequots, Massachusetts

, Pawtuckets and others were destroyed because of these plagues.

Not all relations were negative however. The English introduced tools such as hoes, spades, fences, iron kettles and fishing lines. Some smaller tribes found protection in the colonists and the relationships were prosperous for both sides.

. This impact of Puritanism on many new colonists led or contributed to the founding of new colonies—Rhode Island

, Pennsylvania

, New Jersey

, Delaware

, New Hampshire

, and others—as religious havens that were created for those who wanted to live outside the oppressive reach of the existing theocracy.

The power and influence of Puritan leaders in New England declined further after the Salem Witch Trials

in Salem, Massachusetts

, in the 1690s. Beginning as a trial of one or several self-avowed witches who admitted to practicing voodoo-type rituals with malicious intent, the trials ended with a number of innocent people being falsely accused, found guilty, and executed. Most of the magistrates never admitted fault in the matter, though Samuel Sewall

, publicly apologized in later life.

Some modern Presbyterian denominations are descended, at least in part, from the Puritans (for example the Presbyterian Church (USA)

), although others pre-date the English influence.

Congregational Churches also trace their lineage back to the Puritans. One example is the Congregational Christian Churches (CCC) denomination in the United States (which merged with the Evangelical and Reformed Church

in 1957 to form the United Church of Christ

). The CCC is the direct descendant of New England Puritan congregations, although in the early 19th century a few of these old congregations adopted Unitarianism

.

Another example is the United Reformed Church

in England and Wales (the modern URC also has congregations in Scotland, but its southern components—the Congregational Church in England and Wales and the Presbyterian Church in England—partly descend from Restoration Dissenters).

A number of contemporary Unitarian

congregations in New England such as The First Church in Salem (founded 1629) and The First Parish in Cambridge

(founded 1632) also trace their roots back to English and New England Puritan congregations.

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

Puritans settled in North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

, mainly in New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

. Puritans were generally members of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

who believed the Church of England was insufficiently Reformed

Reformed churches

The Reformed churches are a group of Protestant denominations characterized by Calvinist doctrines. They are descended from the Swiss Reformation inaugurated by Huldrych Zwingli but developed more coherently by Martin Bucer, Heinrich Bullinger and especially John Calvin...

and who therefore opposed royal ecclesiastical policy under Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

, James I of England

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

, and Charles I of England

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

. Most Puritans were "non-separating Puritans", meaning they did not advocate setting up separate congregations distinct from the Church of England; a small minority of Puritans were "separating Puritans" who advocated setting up congregations outside the Church. One Separatist group, the Pilgrims, established the Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony was an English colonial venture in North America from 1620 to 1691. The first settlement of the Plymouth Colony was at New Plymouth, a location previously surveyed and named by Captain John Smith. The settlement, which served as the capital of the colony, is today the modern town...

in 1620. Non-separating Puritans played leading roles in establishing the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America in the 17th century, in New England, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included much of present-day central New England, including portions...

in 1629 and the Connecticut Colony

Connecticut Colony

The Connecticut Colony or Colony of Connecticut was an English colony located in British America that became the U.S. state of Connecticut. Originally known as the River Colony, it was organized on March 3, 1636 as a haven for Puritan noblemen. After early struggles with the Dutch, the English...

in 1636. The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was one of the original English Thirteen Colonies established on the east coast of North America that, after the American Revolution, became the modern U.S...

was established by settlers expelled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony because of their unorthodox religious opinions. Puritans were also active in the New Hampshire

Province of New Hampshire

The Province of New Hampshire is a name first given in 1629 to the territory between the Merrimack and Piscataqua rivers on the eastern coast of North America. It was formally organized as an English royal colony on October 7, 1691, during the period of English colonization...

before it became a crown colony in 1691.

Most Puritans who migrated to North America came in the decade 1630-1640 in what is known as the Great Migration. See the main articles on each of the colonies for information on their political and social history; this article focuses on the religious history of the Puritans in North America.

Background

- For more information, see History of the Puritans under Elizabeth IHistory of the Puritans under Elizabeth IThe reign of Elizabeth I of England, from 1558 to 1603, saw the rise of the Puritan movement in England, its clash with the authorities of the Church of England, and its temporarily effective suppression in the 1590s by severe judicial means.-Background, to 1559:...

, History of the Puritans under James IHistory of the Puritans under James IUnder James I of England, the Puritan movement co-existed with the conforming Church of England in what was generally an accepted form of episcopal Protestant religion...

, and History of the Puritans under Charles IHistory of the Puritans under Charles IUnder Charles I of England, the Puritans became a political force as well as a religious tendency in the country. Opponents of the royal prerogative became allies of Puritan reformers, who saw the Church of England moving in a direction opposite to what they wanted, and objected to increased Roman...

.

The early seventeenth century saw the foundation of many joint stock companies, which were commercial ventures designed to profit from trade or the foundation of colonial settlements. In 1606, King James issued a royal charter

Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal document issued by a monarch as letters patent, granting a right or power to an individual or a body corporate. They were, and are still, used to establish significant organizations such as cities or universities. Charters should be distinguished from warrants and...

to two companies referred to collectively as the Virginia Company

Virginia Company

The Virginia Company refers collectively to a pair of English joint stock companies chartered by James I on 10 April1606 with the purposes of establishing settlements on the coast of North America...

: the London Company

London Company

The London Company was an English joint stock company established by royal charter by James I of England on April 10, 1606 with the purpose of establishing colonial settlements in North America.The territory granted to the London Company included the coast of North America from the 34th parallel ...

and the Plymouth Company

Plymouth Company

The Plymouth Company was an English joint stock company founded in 1606 by James I of England with the purpose of establishing settlements on the coast of North America.The Plymouth Company was one of two companies, along with the London Company, chartered with such...

. While the Virginia Company successfully established the Colony of Virginia in 1608, the Plymouth Company

Plymouth Company

The Plymouth Company was an English joint stock company founded in 1606 by James I of England with the purpose of establishing settlements on the coast of North America.The Plymouth Company was one of two companies, along with the London Company, chartered with such...

was initially unsuccessful in its settlements, which explains their interest in granting a patent to the Pilgrims in 1620.

Two of the Pilgrim settlers in Plymouth Colony – Robert Cushman

Robert Cushman

Robert Cushman was one of the Pilgrims. He was born in the village of Rolvenden in Kent, England, and was baptized in the parish church there on February 9, 1577/78. He spent part of his early life in Canterbury on Sun Street. Cushman married Sarah Reder on 31 July 1606...

and Edward Winslow

Edward Winslow

Edward Winslow was an English Pilgrim leader on the Mayflower. He served as the governor of Plymouth Colony in 1633, 1636, and finally in 1644...

– believed that Cape Ann

Cape Ann

Cape Ann is a rocky cape in northeastern Massachusetts on the Atlantic Ocean. The cape is located approximately 30 miles northeast of Boston and forms the northern edge of Massachusetts Bay. Cape Ann includes the city of Gloucester, and the towns of Essex, Manchester-by-the-Sea, and...

would be a profitable location for a settlement. They therefore organized a company which they named the Dorchester Company and in 1622 sailed to England seeking a patent from the London Company giving them permission to settle there. They were successful and were granted the Sheffield Patent

Sheffield Patent

The Sheffield Patent, dated January 1, 1623 is a land grant from Edmund Sheffield, 1st Earl of Mulgrave of England to Robert Cushman and Edward Winslow and their associates...

(named after Edmund Sheffield, 3rd Baron Sheffield, the member of the Plymouth Company who granted the patent). On the basis of this patent, Roger Conant led a group of fishermen to found Salem

Salem, Massachusetts

Salem is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 40,407 at the 2000 census. It and Lawrence are the county seats of Essex County...

in 1626, being replaced as governor by John Endecott

John Endecott

John Endecott was an English colonial magistrate, soldier and the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. During all of his years in the colony but one, he held some form of civil, judicial, or military high office...

in 1627. During their time in England, Cushman and Winslow convinced Puritan members of the landed gentry

Landed gentry

Landed gentry is a traditional British social class, consisting of land owners who could live entirely off rental income. Often they worked only in an administrative capacity looking after the management of their own lands....

to invest in the Dorchester Company.

Puritan settlement in Virginia Colony (1618)

One small group of Puritans had already settled in Warrascoyack CountyWarrosquyoake Shire

Warrosquoake Shire was officially formed in 1634 in the Virginia colony, but had already been known as "Warascoyack County" before this...

in the Virginia Colony, beginning in 1618 with Christopher Lawne

Christopher Lawne

Christopher Lawne was an English merchant and Puritan of note, born in Blandford, Dorset, who emigrated to Virginia Colony on the Marygold in May 1618 and died the following year....

who established a plantation at Lawne's Creek. He died the following year, but several other prominent Puritan merchants soon emigrated there, including the Bennett family of Somerset. Under the leadership of Richard Bennett

Richard Bennett (Governor)

Richard Bennett was an English Governor of the Colony of Virginia.Born in Wiveliscombe, Somerset, Bennett served as governor from 30 April 1652, until 2 March 1655...

, the community moved from Warrascoyack to neighboring Nansemond beginning in 1635, then sought temporary refuge in Maryland in 1648. They returned to Virginia when the "Roundheads" appointed Bennett as governor there in 1652; later, in 1672, all of them, including Bennett, converted to the Quaker faith upon meeting its founder, George Fox

George Fox

George Fox was an English Dissenter and a founder of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as the Quakers or Friends.The son of a Leicestershire weaver, Fox lived in a time of great social upheaval and war...

.

The Pilgrims (1620)

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

in 1620: the Pilgrims

Pilgrims

Pilgrims , or Pilgrim Fathers , is a name commonly applied to early settlers of the Plymouth Colony in present-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, United States...

.

The Pilgrims were Separatists who held views similar to those proclaimed by Robert Browne, John Greenwood, and Henry Barrowe

Henry Barrowe

Henry Barrowe was an English Puritan and Separatist, executed for his views.-Life:He was born about 1550, in Norfolk, of a family related by marriage to Nicholas Bacon, and probably to John Aylmer, Bishop of London. He matriculated at Clare Hall, Cambridge, in November 1566, and graduated B.A. in...

. The Pilgrims emerged in Elizabethan England at roughly the same time as the Brownists.

The Pilgrims trace their lineage to Richard Clyfton

Richard Clyfton

Richard Clyfton was an English Brownist minister, at Scrooby, Nottinghamshire, and then in Amsterdam.-Life:He is identified with the Richard Clifton who, on 12 February 1585, was instituted to the vicarage of Marnham, near Newark, and on 11 July 1586 to the rectory of Babworth, near Retford, and...

, minister of Babworth

Babworth

Babworth is a village and civil parish in the Bassetlaw district of Nottinghamshire, England, about 1½ miles west of Retford. According to the 2001 census the parish had a population of 1,329...

, Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire is a county in the East Midlands of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west...

. Beginning in the 1580s, Clyfton advocated separation from the Church of England. Clyfton's movement attracted William Brewster

William Brewster (Pilgrim)

Elder William Brewster was a Mayflower passenger and a Pilgrim colonist leader and preacher.-Origins:Brewster was probably born at Doncaster, Yorkshire, England, circa 1566/1567, although no birth records have been found, and died at Plymouth, Massachusetts on April 10, 1644 around 9- or 10pm...

, the postmaster

Postmaster

A postmaster is the head of an individual post office. Postmistress is not used anymore in the United States, as the "master" component of the word refers to a person of authority and has no gender quality...

of Scrooby

Scrooby

Scrooby is a small village, on the River Ryton and near Bawtry, in the northern part of the English county of Nottinghamshire. At the time of the 2001 census it had a population of 329. Until 1766, it was on the Great North Road so became a stopping-off point for numerous important figures...

. Tobias Matthew

Tobias Matthew

Tobias Matthew was Archbishop of York.-Life:He was the son of Sir John Matthew of Ross in Herefordshire, England, and of his wife Eleanor Crofton of Ludlow. He was born at Bristol and was educated at Wells, Somerset, and then in succession at University College and Christ Church, Oxford...

, the Bishop of Durham, who had been part of Archbishop Whitgift's delegation at the Hampton Court Conference, was selected by James to become Archbishop of York

Archbishop of York

The Archbishop of York is a high-ranking cleric in the Church of England, second only to the Archbishop of Canterbury. He is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and metropolitan of the Province of York, which covers the northern portion of England as well as the Isle of Man...

in 1606. He led an anti-Separatist crackdown and Clyfton was removed from his ministry. In response, Brewster offered to organize a dissenting congregation in the manor house in which he lived in Scrooby. Clyfton served as the congregation's pastor, John Robinson

John Robinson (pastor)

John Robinson was the pastor of the "Pilgrim Fathers" before they left on the Mayflower. He became one of the early leaders of the English Separatists, minister of the Pilgrims, and is regarded as one of the founders of the Congregational Church.-Early life:Robinson was born in Sturton le Steeple...

as its teacher, and William Brewster as its chief elder. This congregation was subject to ecclesiastical investigation, and its members faced social hostility from conforming church members, but was not actively persecuted. Nevertheless, disliking the social hostility, and fearing future persecution, the group decided to leave England.

150 members of the congregation made it to Amsterdam

Amsterdam

Amsterdam is the largest city and the capital of the Netherlands. The current position of Amsterdam as capital city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is governed by the constitution of August 24, 1815 and its successors. Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 within city limits, an urban population...

, where they met up with a group of Separatist exiles led by John Smyth

John Smyth (1570-1612)

John Smyth was an early Baptist minister of England and a defender of the principle of religious liberty. Historians consider John Smyth as a founder of the Baptist denomination.-Early life:...

, which had joined the congregation of English exiles led by Francis Johnson

Francis Johnson (Brownist)

Francis Johnson was an English presbyterian separatist minister, pastor to an English exile congregation in the Netherlands.-Early life:...

. After a year at Amsterdam, tensions between Smyth and Johnson grew so high, that the Pilgrims decided to move to Leiden. While there, many worked at Leiden University

Leiden University

Leiden University , located in the city of Leiden, is the oldest university in the Netherlands. The university was founded in 1575 by William, Prince of Orange, leader of the Dutch Revolt in the Eighty Years' War. The royal Dutch House of Orange-Nassau and Leiden University still have a close...

or in the textile, printing and brewing trades. John Robinson participated in the Calvinist-Arminian Controversy

History of Calvinist-Arminian debate

The Calvinist-Arminian debate is best known as a dispute between Dutch Protestants in the early seventeenth century. The theological points remain at issue as the basis of current disagreements amongst some Protestants, particularly evangelicals...

while at Leiden University, arguing on behalf of the Gomarists.

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

. In 1620, after receiving a patent

Land grant

A land grant is a gift of real estate – land or its privileges – made by a government or other authority as a reward for services to an individual, especially in return for military service...

from the London Company

London Company

The London Company was an English joint stock company established by royal charter by James I of England on April 10, 1606 with the purpose of establishing colonial settlements in North America.The territory granted to the London Company included the coast of North America from the 34th parallel ...

, the Pilgrims left for New England onboard the Mayflower

Mayflower

The Mayflower was the ship that transported the English Separatists, better known as the Pilgrims, from a site near the Mayflower Steps in Plymouth, England, to Plymouth, Massachusetts, , in 1620...

, landing at Plymouth Rock

Plymouth Rock

Plymouth Rock is the traditional site of disembarkation of William Bradford and the Mayflower Pilgrims who founded Plymouth Colony in 1620. It is an important symbol in American history...

. The colony founded by the Pilgrims was called Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony was an English colonial venture in North America from 1620 to 1691. The first settlement of the Plymouth Colony was at New Plymouth, a location previously surveyed and named by Captain John Smith. The settlement, which served as the capital of the colony, is today the modern town...

.

Background: The Religious and Political Situation in England, 1625-1629

The controversy over Richard Montagu's New Gagg was still on parliamentarians' minds when Parliament met in May 1625. Furthermore, shortly before the opening of the parliament, Charles was married by proxy to Henrietta Maria of FranceHenrietta Maria of France

Henrietta Maria of France ; was the Queen consort of England, Scotland and Ireland as the wife of King Charles I...

, the Catholic daughter of Henry IV of France

Henry IV of France

Henry IV , Henri-Quatre, was King of France from 1589 to 1610 and King of Navarre from 1572 to 1610. He was the first monarch of the Bourbon branch of the Capetian dynasty in France....

(thus cementing an alliance with France in preparation for war against Spain). As such, at this parliament, Puritan MPs openly worried that Charles was preparing to restrict the recusancy

Recusancy

In the history of England and Wales, the recusancy was the state of those who refused to attend Anglican services. The individuals were known as "recusants"...

laws (which Charles was, in fact, planning on doing, having agreed to do so in the secret marriage treaty he negotiated with Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and of Navarre from 1610 to 1643.Louis was only eight years old when he succeeded his father. His mother, Marie de Medici, acted as regent during Louis' minority...

).

John Pym

John Pym was an English parliamentarian, leader of the Long Parliament and a prominent critic of James I and then Charles I.- Early life and education :...

launched an attack on Richard Montagu in the House of Commons. As a response, Montagu wrote a pamphlet entitled Appello Caesarem (Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

"I Appeal to Caesar") (a reference to Acts 25:10-12), in which he appealed to Charles to protect him against the Puritans. Charles responded by making Montagu a royal chaplain, signaling that he was willing to defend Montagu against Puritan opposition.

In this atmosphere, Puritan suspicions that Charles was secretly planning to restore Roman Catholicism in England mounted. As such, the Parliament, heavily influenced by its Puritan members, was reluctant to grant Charles revenue, since they feared that any revenue granted might be used to support an army that would re-impose Catholicism on England. For example, since 1414, every English monarch had been authorized by their first Parliament to collect the customs duties of Tonnage and Poundage

Tonnage and Poundage

Tonnage and Poundage were certain duties and taxes first levied in Edward II's reign on every tun of imported wine, which came mostly from Spain and Portugal, and on every pound weight of merchandise exported or imported. Traditionally tonnage and poundage was granted by Parliament to the king...

for the duration of their reign; the 1625 Parliament, however, voted to allow Charles to collect Tonnage and Poundage for only one year. Furthermore, when Charles wanted to intervene in the Thirty Years' War by declaring war on Spain, Parliament granted him only £140,000, a totally insufficient sum to pursue the war.

The war with Spain went ahead (partially funded by tonnage and poundage collected by Charles even after he was no longer authorized to do so). Buckingham was put in charge of the war effort, and failed miserably. As such, in 1628, Parliament called for Buckingham's replacement, but Charles stuck by Buckingham. Parliament went on to pass the Petition of Right

Petition of right

In English law, a petition of right was a remedy available to subjects to recover property from the Crown.Before the Crown Proceedings Act 1947, the British Crown could not be sued in contract...

, a declaration of Parliament's rights. Charles accepted the Petition, though this did not lead to a change in his behaviour.

In August 1628, Buckingham was assassinated by a disillusioned soldier, John Felton

John Felton

John Felton was a lieutenant in the English army who stabbed George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham to death in Portsmouth on 23 August 1628.-Background:...

. The nation responded with spontaneous celebration, which angered Charles.

When Parliament resumed sitting in January 1629, Charles was met with outrage over the case of John Rolle, an MP who had been prosecuted for failing to pay Tonnage and Poundage even though Charles had agreed to "no taxation without representation

No taxation without representation

"No taxation without representation" is a slogan originating during the 1750s and 1760s that summarized a primary grievance of the British colonists in the Thirteen Colonies, which was one of the major causes of the American Revolution...

" (to use a slogan from a later era) in the Petition of Right. John Finch

John Finch

John Finch, 1st Baron Finch was an English judge, and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1614 and 1629. He was Speaker of the House of Commons.-Early life:...

, the Speaker of the House of Commons

Speaker of the British House of Commons

The Speaker of the House of Commons is the presiding officer of the House of Commons, the United Kingdom's lower chamber of Parliament. The current Speaker is John Bercow, who was elected on 22 June 2009, following the resignation of Michael Martin...

, was famously held down in the Speaker's Chair in order to allow the House to pass a resolution condemning the king.

Charles was so outraged by Parliament's opposition to his policies that he determined to rule without ever calling a parliament again, thus initiating the period known as his Personal Rule

Personal Rule

The Personal Rule was the period from 1629 to 1640, when King Charles I of England, Scotland and Ireland ruled without recourse to Parliament...

(1629–1640), which his enemies termed the Eleven Years' Tyranny. This period also saw the ascendancy of Laudianism in England (see previous section), which led Puritan critics to term this period the Caroline Captivity of the Church (a reference to the so-called Babylonian Captivity of the Church, which was itself a reference to the Babylonian Captivity

Babylonian captivity

The Babylonian captivity was the period in Jewish history during which the Jews of the ancient Kingdom of Judah were captives in Babylon—conventionally 587–538 BCE....

).

The "Great Migration" and the foundation of Puritan New England, 1630-1642

The events of 1629 convinced many Puritans that King Charles was an ardent foe of further church reforms who would enforce Laudianism on the Church of England throughout his reign. Since King Charles was only 29 years old in 1629, they were thus faced with the prospect of countless decades without reforms and with their proposals being suppressed. Given this situation, some Puritans began considering founding their own colony where they could worship in a fully reformed church, far from the prying eyes of King Charles and the bishops. This was a far different view of the church than that held by the Separatists of Plymouth Colony.John Winthrop and the foundation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1630

The early seventeenth century saw the foundation of many joint stock companies, which were commercial ventures designed to profit from trade or the foundation of colonial settlements. The most famous of the joint stock companies was the Honourable East India Company, chartered in 1600. In 1606, King James had issued a royal charterRoyal Charter

A royal charter is a formal document issued by a monarch as letters patent, granting a right or power to an individual or a body corporate. They were, and are still, used to establish significant organizations such as cities or universities. Charters should be distinguished from warrants and...

to two companies referred to collectively as the Virginia Company

Virginia Company

The Virginia Company refers collectively to a pair of English joint stock companies chartered by James I on 10 April1606 with the purposes of establishing settlements on the coast of North America...

: the London Company

London Company

The London Company was an English joint stock company established by royal charter by James I of England on April 10, 1606 with the purpose of establishing colonial settlements in North America.The territory granted to the London Company included the coast of North America from the 34th parallel ...

(which successfully established the Colony of Virginia in 1608) and the Plymouth Company

Plymouth Company

The Plymouth Company was an English joint stock company founded in 1606 by James I of England with the purpose of establishing settlements on the coast of North America.The Plymouth Company was one of two companies, along with the London Company, chartered with such...

(which was unsuccessful at establishing settlements, which explains why they were eager to grant a patent to the Pilgrims in 1620).

Two of the Pilgrim settlers in Plymouth Colony - Robert Cushman

Robert Cushman

Robert Cushman was one of the Pilgrims. He was born in the village of Rolvenden in Kent, England, and was baptized in the parish church there on February 9, 1577/78. He spent part of his early life in Canterbury on Sun Street. Cushman married Sarah Reder on 31 July 1606...

and Edward Winslow

Edward Winslow

Edward Winslow was an English Pilgrim leader on the Mayflower. He served as the governor of Plymouth Colony in 1633, 1636, and finally in 1644...

- believed that Cape Ann

Cape Ann

Cape Ann is a rocky cape in northeastern Massachusetts on the Atlantic Ocean. The cape is located approximately 30 miles northeast of Boston and forms the northern edge of Massachusetts Bay. Cape Ann includes the city of Gloucester, and the towns of Essex, Manchester-by-the-Sea, and...

would be a profitable location for a settlement. They therefore organized a company which they named the Dorchester Company and in 1622 sailed to England seeking a patent from the London Company giving them permission to settle there. They were successful and were granted the Sheffield Patent

Sheffield Patent

The Sheffield Patent, dated January 1, 1623 is a land grant from Edmund Sheffield, 1st Earl of Mulgrave of England to Robert Cushman and Edward Winslow and their associates...

(named after Edmond, Lord Sheffield, the member of the Plymouth Company who granted the patent). On the basis of this patent, Roger Conant led a group of fishermen to found Salem

Salem, Massachusetts

Salem is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 40,407 at the 2000 census. It and Lawrence are the county seats of Essex County...

in 1626, being replaced as governor by John Endecott

John Endecott

John Endecott was an English colonial magistrate, soldier and the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. During all of his years in the colony but one, he held some form of civil, judicial, or military high office...

in 1627. The Pilgrims went to New England for a freedom of religion.

During their time in England, Cushman and Winslow had convinced many Puritan members of the landed gentry

Landed gentry

Landed gentry is a traditional British social class, consisting of land owners who could live entirely off rental income. Often they worked only in an administrative capacity looking after the management of their own lands....

to invest in the Dorchester Company. In 1627, the Dorchester Company went bankrupt, but was succeeded by the New England Company (the membership of the Dorchester and New England Companies overlapped). The New England Company sought clearer title to the New England land of the proposed settlement than provided by the Sheffield Patent and in March 1629 succeeded in obtaining from King Charles a royal charter

Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal document issued by a monarch as letters patent, granting a right or power to an individual or a body corporate. They were, and are still, used to establish significant organizations such as cities or universities. Charters should be distinguished from warrants and...

changing the name of the company to the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England and granting them the land to found the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America in the 17th century, in New England, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included much of present-day central New England, including portions...

. It is unclear why Charles agreed to this, but it would appear that he did not realize that the group was dominated by Puritans and believed that it was a purely commercial company.

John Winthrop

John Winthrop was a wealthy English Puritan lawyer, and one of the leading figures in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the first major settlement in New England after Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led the first large wave of migrants from England in 1630, and served as governor for 12 of...

, a lawyer who had practiced in the Court of Wards, began to explore the idea of creating a Puritan colony in New England. After all, the Pilgrims at Plymouth Colony had proven that such a colony was viable. Instead of living in England under the rule of a king hostile to their interests, the Puritans could establish a colony in New England far from the king's interference. Throughout 1628 and 1629, Puritans in Winthrop's social circle discussed the possibility of moving to New England. It was noted that the royal charter establishing the Massachusetts Bay Company had not specified where the company's annual meeting should be held; this raised the possibility that the governor of the company could move to the new colony and serve as governor of the colony, while the general court of the company could be transformed into the colony's legislative assembly. John Winthrop participated in these discussions and in March 1629, signed the Cambridge Agreement, by which the non-emigrating shareholders of the company agreed to turn over control of the company to the emigrating shareholders. As Winthrop was the wealthiest of the emigrating shareholders, the company decided to make him governor, and entrusted him with the company charter.

Winthrop sailed for New England in 1630 along with 700 colonists on board eleven ships known collectively as the Winthrop Fleet

Winthrop Fleet

The Winthrop Fleet was a group of eleven sailing ships under the leadership of John Winthrop that carried approximately 700 Puritans plus livestock and provisions from England to New England over the summer of 1630.-Motivation:...

. Winthrop himself sailed on board the Arbella

Arbella

The Arbella or Arabella was the flagship of the Winthrop Fleet on which, between April 8 and June 12, 1630, Governor John Winthrop, other members of the Company and Puritan emigrants transported themselves and the Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company from England to Salem, thereby giving legal...

. During the crossing, he preached a sermon entitled "A Model of Christian Charity", in which he called on his fellow settlers to make their new colony a City upon a Hill

City upon a Hill

A City Upon A Hill is a phrase from the parable of Salt and Light in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount. In Matthew 5:14, he tells his listeners, "You are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden."-American usage:...

(a reference to Matthew 5:14-16), meaning that they would be a model to all the nations of Europe as to what a properly reformed Christian commonwealth should look like. (This was particularly poignant in 1630, since the Thirty Years' War

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most countries in Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history....

was going bad for the Protestants and Catholicism was being restored in lands previously reformed - e.g. by the 1629 Edict of Restitution

Edict of Restitution

The Edict of Restitution, passed eleven years into the Thirty Years' Wars on March 6, 1629 following Catholic successes at arms, was a belated attempt by Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor to impose and restore the religious and territorial situations reached in the Peace of Augsburg...

.)

Logistics of the Great Migration

Most of the Puritans who emigrated settled in the New EnglandNew England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

area. However, the Great Migration

Great Migration (Puritan)

The Puritan migration to New England was marked in its effects in the two decades from 1620 to 1640, after which it declined sharply for a while. The term Great Migration usually refers to the migration in this period of English settlers, primarily Puritans to Massachusetts and the warm islands of...

of Puritans was relatively short-lived and not as large as is often believed. It began in earnest in 1629 with the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America in the 17th century, in New England, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included much of present-day central New England, including portions...

and ended in 1642 with the start of the English Civil War when King Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

effectively shut off emigration to the colonies. Emigration was officially restricted to conforming churchmen in December 1634 by his Privy Council. From 1629 through 1643 approximately 21,000 Puritans emigrated to New England

The Great Migration of Puritans to New England was primarily an exodus of families. Between 1630 and 1640 over 13,000 men, women, and children sailed to Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

. The religious and political factors behind the Great Migration influenced the demographics

Demographics

Demographics are the most recent statistical characteristics of a population. These types of data are used widely in sociology , public policy, and marketing. Commonly examined demographics include gender, race, age, disabilities, mobility, home ownership, employment status, and even location...

of the emigrants. Rather than groups of young men seeking economic success (as predominated Virginia colonies), Puritan ships were laden with “ordinary” people, old and young, families as well as individuals. Just a quarter of the emigrants were in their twenties when they boarded ship in the 1630s, making young adults a minority in New England settlements. The New World Puritan population was more of a cross section in age of English population than those of other colonies. This meant that the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America in the 17th century, in New England, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included much of present-day central New England, including portions...

retained a relatively “normal” population composition. In contrast to the colony in Virginia – where the ratio of colonist men to women was 4:1 in early decades and at least 2:1 in later decades, and where limited intermarriage with native women took place – nearly half of the Puritan immigrants to the New World were women, and there was little intermarriage with natives. The majority of families who traveled to Massachusetts Bay were families in progress, with parents who were not yet through with their reproductive years and whose continued fertility would make New England’s population growth possible. The women who emigrated were critical agents in the success of the establishment and maintenance of the Puritan colonies in North America. Success in the early colonial economy depended largely on labor, which was conducted by members of Puritan families. It was through this labor that Puritans endeavored to create their “city on a hill”, a productive, morally exemplary colony far from the corruption of the Church of England.

New England theological controversies, 1632-1642

As noted earlier, the vast majority of Puritans who settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony were non-separating Puritans. This meant that, while they deeply abhorred many of the practices of the Church of England, they refused to separate from the Church of England because they placed an extremely high value on the doctrine of the unity of the Church. They denounced the Separating Puritans as schismaticsSchism (religion)

A schism , from Greek σχίσμα, skhísma , is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization or movement religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a break of communion between two sections of Christianity that were previously a single body, or to a division within...

. Thus, although the Puritans in Massachusetts erected their church along Presbyterian-Congregational lines, they technically remained in full communion

Full communion

In Christian ecclesiology, full communion is a relationship between church organizations or groups that mutually recognize their sharing the essential doctrines....

with the Church of England. This position led to two major theological controversies with Separating Puritans in the course of the 1630s: the Roger Williams controversy, and the Anne Hutchinson controversy.

The Roger Williams controversy

Roger WilliamsRoger Williams (theologian)

Roger Williams was an English Protestant theologian who was an early proponent of religious freedom and the separation of church and state. In 1636, he began the colony of Providence Plantation, which provided a refuge for religious minorities. Williams started the first Baptist church in America,...

, a Separating Puritan minister, arrived in Boston

Boston

Boston is the capital of and largest city in Massachusetts, and is one of the oldest cities in the United States. The largest city in New England, Boston is regarded as the unofficial "Capital of New England" for its economic and cultural impact on the entire New England region. The city proper had...

in 1631. He was almost immediately invited to become the pastor of the local congregation. Williams refused the invitation on the grounds that the congregation had not separated from the Church of England. He then attempted to become pastor of the church at Salem

Salem, Massachusetts

Salem is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 40,407 at the 2000 census. It and Lawrence are the county seats of Essex County...

, but was blocked by Boston political leaders, who objected to his separatism. He thus spent two years with his fellow Separatists in the Plymouth Colony, but ultimately came into conflict with them and returned to Salem. There, he became pastor in May 1635, against the objection of the Boston authorities. Williams set forth a manifesto in which he declared that 1) the Church of England was apostate and fellowship with it was a grievous sin; 2) the Massachusetts Colony's charter falsely said that King Charles was a Christian; 3) that the colony should not be allowed to impose oaths on its citizens because that was forbidden by Matthew 5:33-37

Williams' actions so outraged the Puritan leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony that they expelled him from the colony. In 1636, the exiled Williams founded the city of Providence, Rhode Island

Providence, Rhode Island

Providence is the capital and most populous city of Rhode Island and was one of the first cities established in the United States. Located in Providence County, it is the third largest city in the New England region...

. Williams was one of the first Puritans to advocate separation of church and state

Separation of church and state

The concept of the separation of church and state refers to the distance in the relationship between organized religion and the nation state....

and Rhode Island was one of the first places in the Christian world to recognize freedom of religion

Freedom of religion

Freedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance; the concept is generally recognized also to include the freedom to change religion or not to follow any...

.

The Anne Hutchinson controversy

Anne HutchinsonAnne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson was one of the most prominent women in colonial America, noted for her strong religious convictions, and for her stand against the staunch religious orthodoxy of 17th century Massachusetts...

and her family moved from Boston, Lincolnshire

Boston, Lincolnshire

Boston is a town and small port in Lincolnshire, on the east coast of England. It is the largest town of the wider Borough of Boston local government district and had a total population of 55,750 at the 2001 census...

to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634, following their Puritan minister John Cotton. Cotton began pastoring a congregation in Boston, Massachusetts, and Hutchinson joined his congregation. Following the Puritan practice of conventicling, Hutchinson set up a conventicle in her home. At the conventicle, a group would meet during the week to discuss John Cotton's sermon from the previous Sunday. Hutchinson proved to be extremely charismatic at propounding on Cotton's ideas during these conventicles, and eventually the size of her conventicle swelled to 80 people and had to be moved from her home to the church building.

Cotton had long denounced Arminianism

Arminianism

Arminianism is a school of soteriological thought within Protestant Christianity based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius and his historic followers, the Remonstrants...

in his sermons. Hutchinson took up the anti-Arminian cause in strong language, propounding an extreme form of double predestination (a view popularized among English Puritans by William Perkins), which held that God chose those who would go to heaven

Heaven

Heaven, the Heavens or Seven Heavens, is a common religious cosmological or metaphysical term for the physical or transcendent place from which heavenly beings originate, are enthroned or inhabit...

(the elect

Predestination

Predestination, in theology is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God. John Calvin interpreted biblical predestination to mean that God willed eternal damnation for some people and salvation for others...

) and those who would go to hell

Hell in Christian beliefs

Christian views on Hell vary, but in general traditionally agree that hell is a place or a state in which the souls of the unsaved suffer the consequences of sin....

(the reprobate), and that His decision inevitably and infallibly came to pass. Applying this framework to the Arminian controversy, Hutchinson argued that people were either under a covenant of works (they were relying on good works

Good works

Good works, or simply works, within Christian theology are a person's actions or deeds, contrasting with interior qualities such as grace or faith.The New Testament exhibits a tension between two aspects of grace:...

for their salvation, and therefore were really damned) or else a covenant of grace

Covenant Theology

Covenant theology is a conceptual overview and interpretive framework for understanding the overall flow of the Bible...

(in which case they were dependent only on God

God

God is the English name given to a singular being in theistic and deistic religions who is either the sole deity in monotheism, or a single deity in polytheism....

's grace

Divine grace

In Christian theology, grace is God’s gift of God’s self to humankind. It is understood by Christians to be a spontaneous gift from God to man - "generous, free and totally unexpected and undeserved" - that takes the form of divine favour, love and clemency. It is an attribute of God that is most...

, and were therefore really saved

Salvation

Within religion salvation is the phenomenon of being saved from the undesirable condition of bondage or suffering experienced by the psyche or soul that has arisen as a result of unskillful or immoral actions generically referred to as sins. Salvation may also be called "deliverance" or...

).

Christian heresy