Francis Amasa Walker

Encyclopedia

Francis Amasa Walker was an American economist

, statistician

, journalist

, educator, academic administrator, and military officer in the Union Army

. Walker was born into a prominent Boston family, the son of the economist and politician Amasa Walker

, and he graduated from Amherst College

at the age of 20. He received a commission to join the 15th Massachusetts Infantry

and quickly rose through the ranks as an assistant adjutant general

. Walker fought in the Peninsula Campaign

and was injured at the Battle of Chancellorsville

but subsequently participated in the Bristoe

, Overland

, and Richmond-Petersburg Campaigns

before being captured by Confederate forces and held at the infamous Libby Prison

. In July 1866, he was nominated by President

Andrew Johnson

and confirmed by the United States Senate

for the award of the honorary grade of brevet

brigadier general

United States Volunteers

, to rank from March 13, 1865, when he was age 24.

Following the war, Walker served on the editorial staff of the Springfield Republican

before using his family and military connections to gain appointment as the Chief of the Bureau of Statistics from 1869 to 1870 and Superintendent of the 1870 census where he published an award-winning Statistical Atlas visualizing the data for the first time. He joined Yale University

's Sheffield Scientific School

as a professor of political economy

in 1872 and rose to international prominence serving as a chief member of the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition, American representative to the 1878 International Monetary Conference

, President of the American Statistical Association

in 1882, and inaugural President of the American Economic Association

in 1886, and vice president of the National Academy of Sciences

in 1890. Walker also led the 1880 census which resulted in a twenty-two volume census, cementing Walker's reputation as the nation's preeminent statistician.

As an economist, Walker debunked the wage-fund doctrine

and engaged in a prominent scholarly debate with Henry George

on land, rent, and taxes. Although Walker argued that obligations existed between the employer and the employed, he was an opponent of the nascent socialist movement and argued in support of bimetallism

. He published his International Bimetallism at the height of the 1896 presidential election campaign

in which economic issues were prominent. Walker was a prolific writer, authoring ten books on political economy and military history. In recognition of his contributions to economic theory, beginning in 1947, the American Economic Association recognized the lifetime achievement of an individual economist with a "Francis A. Walker Medal".

Walker accepted the presidency of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

in 1881, a position he held for fifteen years until his death. During his tenure, he placed the institution on more stable financial footing by aggressively fund-raising and securing grants from the Massachusetts government and implemented many curricular reforms, oversaw the launch of new academic programs, and expanded the size of the Boston campus, faculty, and student enrollments. MIT's Walker Memorial Hall, a former students' clubhouse and one of the original buildings on the Charles River campus, was dedicated to him in 1916.

, a prominent economist and state politician. The Walkers had three children, Emma (born 1835), Robert (born 1837), and Francis. Because the Walkers' next-door neighbor was Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

, the junior Walker and junior Holmes

were playmates as young children and renewed their friendship later in life. The family moved from Boston to North Brookfield, Massachusetts

in 1843 and remained there. As a boy he had both a noted temper as well as a magnetic personality.

Beginning his schooling at the age of seven, Walker studied Latin at various private and public schools in Brookfield before being sent to the Leicester Academy when he was twelve. He completed his college preparation by the time he was fourteen and spent another year studying Greek and Latin under the future suffragist and abolitionist Lucy Stone

, and entered Amherst College

at the age of fifteen. Although he had planned to matriculate at Harvard

after his first year at Amherst, Walker's father believed his son was too young to enter the larger college and insisted he remain at Amherst. While he had entered with the class of '59, Walker became ill during his first year there and fell back a year. He was a member of the Delta Kappa and Athenian societies as a freshman, joined and withdrew from Alpha Sigma Phi

as a sophomore on account of "rowdyism", and finally joined Delta Kappa Epsilon

. As a student, Walker was awarded the Sweetser Essay Prize and the Hardy Prize for extemporaneous speaking

. He graduated in 1860 as Phi Beta Kappa with a degree in law. After graduation, he joined the law firm of Charles Devens

and George Frisbie Hoar

in Worcester, Massachusetts

.

and Governor

John Andrew

to grant him a commission as a second lieutenant under Devens' command of the 15th Massachusetts. Following his 21st birthday and the First Battle of Bull Run

in July 1861, Walker secured the consent of his father to join the war effort as well as assurances by Devens that he would receive an officer's commission. However, the lieutenancy never materialized and Devens instead offered Walker an appointment as a sergeant major

, which he assumed on August 1, 1861, after re-tailoring his previously ordered lieutenant's uniform to reflect his enlisted status. However, by September 14, 1861, Walker had been recommended by Devens and reassigned to Brig. Gen.

Darius N. Couch

as assistant adjutant general

and promoted to captain. Walker remained in Washington, D.C.

, over the winter of 1861–1862 and did not see combat until May 1862 at the Battle of Williamsburg

. Walker also served at Seven Pines

as well as at the Seven Days Battles

of the Peninsula Campaign

in the summer of 1862 under Maj. Gen.

George B. McClellan

in the Army of the Potomac

.

until his promotion on August 11 to major

and transferral with General Couch to the II Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Although the II Corps later saw action at the battles of Antietam

and Fredericksburg

, the latter being under the new command of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

, Walker and the Corps did not join Burnsides's Mud March

over the winter. Walker was promoted to lieutenant colonel

on January 1, 1863, and remained with the II Corps. He fought the Battle of Chancellorsville

in May 1863, where his hand and wrist were shattered and neck lacerated by an exploding shell. A record of the 1880 Census indicated that he had "compound fracture of the metacarpal bones of the left hand resulting in permanent extension of his hand." Later in 1896, as the President of MIT, he would receive one of the first radiographs in the country, which documented the extent of the damage to his hand. He did not return to service until August 1863. Walker participated in the Bristoe Campaign

and narrowly escaped encirclement during the Battle of Bristoe Station

before withdrawing and encamping near the Berry Hill Plantation

for much of the winter and spending some leave in the North.

After extensive reorganization during the winter of 1863–1864, Walker and the Army of the Potomac fought in the Overland Campaign

through May and June 1864. The Battle of Cold Harbor

in early June took a substantial toll on the ranks of the II Corps and Walker injured his knee during the battle. In the ensuing Richmond-Petersburg Campaign

, Walker was appointed a brevet

colonel

. However, on August 25, 1864, as he rode to find Maj. Gen. John Gibbon

at the front during the Second Battle of Ream's Station

, Walker was surrounded and captured by the 11th Georgia Infantry. On August 27, Walker was able to escape from a marching prisoner column with another prisoner but was recaptured by the 51st North Carolina Infantry after trying to swim across the Appomattox River

and nearly drowning. After being held as a prisoner in Petersburg

, he was transferred to the infamous Libby Prison

in Richmond

, where his older brother was also held. In October 1864, Walker was released with thirty other prisoners as a part of an exchange.

Walker returned to North Brookfield to recuperate and resigned his commission on January 8, 1865, as a result of his injuries and health. At the end of the war, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock

recommended that Walker be brevetted as a brigadier general of U.S. Volunteers in recognition of his meritorious services during the war and especially his gallant conduct at Chancellorsville. On July 9, 1866, Walker was nominated by President

Andrew Johnson

for the award of the honorary grade of brevet

brigadier general

, U.S. Volunteers, to rank from March 13, 1865 (when he was age 24), for gallant conduct at the battle of Chancellorsville and meritorious services during the war. The U.S. Senate confirmed the award on July 23, 1866.

until being offered an editorial position at the Springfield Republican

by Samuel Bowles

. At the Republican, Walker wrote on Reconstruction era politics, railroad regulation, and representation.

as the Chief of the U.S. Bureau of Statistics and Deputy Special Commissioner of Internal Revenue in January 1869. On January 29, 1869, Major General J.D. Cox

, who had also previously served in McClellan's army and was currently the Secretary of the Interior

under President

Grant

's administration, notified the twenty-nine-year-old Walker that he was being nominated to become the Superintendent of the 1870 census. After he was confirmed

by the Senate

, Walker sought to strike a moderate reformist position free from the inefficient and unscientific methods of the 1850 and 1860 censuses; however, the required legislation was not passed and the census proceeded under the rules governing previous collections. Among the problems facing Walker included a lack of authority to determine, enforce, or control the marshals

' personnel, methods, or timing all of which were regularly manipulated by local political interests. Additionally, the 1870 census would not only occur five years after Civil War but would also be the first in which emancipated

African American

s would be fully counted in the census.

Owing to the confluence of these problems, the Census was completed and tabulated several months behind schedule to much popular criticism, and led indirectly to a deterioration in Walker's health during the spring of 1871. Walker took leave to travel to England with Bowles that summer to recuperate and upon return that fall, despite an offer from The New York Times

to join their editorial board with an annual salary of $8,000 ($ in 2009), accepted Secretary Columbus Delano

's offer to become the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs in November 1871. The appointment was simultaneously a go-around to continue to fund Walker's federal responsibilities as Census superintendent despite Congress' cessation of appropriations for the position as well as a political opportunity to replace a scandal-ridden predecessor. Walker continued to work on the Census for several years thereafter, culminating in the publication of the Statistical Atlas of the United States that was unprecedented in its use of visual statistics and maps to report the results of the Census. The Atlas won him praise from both the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

as well as a First Class medal from the International Geographical Congress

.

to meet various chieftains. Walker echoed Grant's recommendation that the Native Americans be secured on reservations of limited mineral or agricultural value so they could be educated and reformed. In November 1872, an eruption of settler-Indian violence in Oregon known as the Modoc War

hastened Walker's disinterest in the position and he resigned as Commissioner on December 26, 1872 to take a faculty position at Yale. However, Walker also criticized his successors' graft, corruption, and abuse of power in subsequent years and published The Indian Question in 1874.

after failing to recruit Horace White

and Charles Nordhoff for the position. That spring, Walker was nominated to run for the Secretary of the State of Connecticut

, running on a platform that would later be embodied by the "Mugwump

" movement, but ultimately lost to Marvin H. Sanger by a margin of 7,200 votes out of 99,000 cast. In the summer, the faculty of Amherst attempted to recruit him to become the President, but the position went instead to the Rev. Julius Hawley Seelye

to appease the more conservative trustees.

Walker's rise to prominence was further accelerated by his appointment by Charles Francis Adams, Jr.

as the Chief of the Bureau of Awards at the 1876 Centennial Exposition

in Philadelphia. Previous world expositions in Europe were fraught with national factionalism and a superabundance of awards. Walker imposed a much leaner operation replacing juries with judges and being more selective in awarding prizes. Walker won formal international recognition when he was named a "Knight Commander" by Sweden and Norway and a "Comendador" by Spain. He was also invited to serve as Assistant Commissioner General for the 1878 Paris Exposition

. The Centennial Exposition affected Walker's later career by greatly increasing his interest in technical education as well as introducing him to MIT President John D. Runkle and Treasurer John C. Cummings

.

James A. Garfield, had been passed to allow him to appoint trained census enumerators free from political influence. Notably, the 1880 Census's results suggested population throughout the Southern states had increased improbably over Walker's 1870 census but an investigation revealed that the latter had been inaccurately enumerated. Walker publicized the discrepancy even as it effectively discredited the accuracy his 1870 work. The tenth Census resulted in the publication of twenty-two volumes, was popularly regarded as the best census of any up to that time, and definitively established Walker's reputation as the preeminent statistician in the nation. The Census was again delayed as a result of its size and was the subject of praise and criticism on its comprehensiveness and relevance. Walker also used the position as a bully pulpit

to advocate for the creation of a permanent Census Bureau

to not only ensure that professional statisticians could be trained and retained but that the information could be better popularized and disseminated. Following Garfield's 1880 election

, there was wide speculation that he would name Walker to be Secretary of the Interior

, but Walker had accepted the offer to become President of MIT in the spring of 1881 instead.

's vacated post at Yale's

recently established Sheffield Scientific School

led by the mineralogist George Jarvis Brush

. While at Yale, Walker served as a member of the School Committee at New Haven (1877–1880) and the Connecticut Board of Education (1878–1881).

Walker was awarded honorary

or ad eundem

degrees from Amherst (M.A. 1863, Ph.D. 1875, LL.D. 1882), Yale (M.A. 1873, LL.D. 1882), Harvard (LL.D. 1883), Columbia

(LL.D. 1887), St. Andrews (LL.D. 1888), Dublin

(LL.D. 1892), Halle (Ph.D. 1894), and Edinburgh

(LL.D. 1896). He was elected as an honorary member of the Royal Statistical Society

in 1875 and the National Academy of Sciences

in 1878 where he served as the vice president from 1890 until his death. In addition to being elected as the president of the American Statistical Association

in 1882, he helped found and launch the International Statistical Institute

in 1885 and was named its "President-adjoint" in 1893. Walker also served as the inaugural president of the American Economic Association

from 1885 to 1892. He took appointments as a lecturer at Johns Hopkins University

(its first professor of economics) from 1877 to 1879, lecturer at Harvard University

in 1882, 1883, and 1896, and trustee at Amherst College

from 1879 to 1889.

and institutionalism

, he is not readily classified into either. As a Professor of Political Economy, his first major scholarly contribution was on his The Wages Question which set out to debunk the wage-fund doctrine

as well as address the then-radical notion of obligations between the employer and the employed. His theory of wage distribution later came to be known as residual theory and set the stage for contributions by John Bates Clark

on the marginal productivity theory. Despite Walker's advocacy of profit sharing

and expansion of educational opportunities using trade and industrial schools, he was an avowed opponent of the nascent socialist movement and published critiques of Edward Bellamy

's popular novel Looking Backward

.

engaged in a prominent debate over economic rent

s, land

, money, and taxes. Based on a series of lectures delivered at Harvard, Walker published his Land and Its Rent in 1883 as a criticism of George's 1879 Progress and Poverty

. Walker's position on international bimetallism

influenced his arguments that the primary cause of economic depressions was not land speculation, but rather constriction of the money supply. Walker also criticized George's assumptions that technical progress was always labor saving and whether land held for speculation was unproductive or inefficient.

in Paris while also attending the 1878 Exposition. Not only were the attempts by the United States to re-establish an international silver standard

defeated, but Walker also had to scramble to complete the report on the Exposition in only four days. Although he returned to the U.S. in October disheartened by the failure of the conference and exhausted by his obligations at the Exposition, the trip had secured Walker a commanding national and international reputation.

Walker published International Bimetallism in 1896 roundly critiquing the demonetization of silver out of political pressure and the impact of this change on prices and profits as well as worker employment and wages. Walker's reputation and position on the issue isolated him among public figures and made him a target in the press. The book was published in the midst of the 1896 presidential election pitting populist "silver

" candidate William Jennings Bryan

against the capitalist "gold

" candidate William McKinley

and the competing interpretations of the nation's leading economist's stance on the issue became a political football

during the campaign. The presidential candidate and economist were not close allies as Walker advocated a double standard by all leading financial nations while Bryan argued for the United States' unilateral shift to a silver standard. The rift was heightened by the east-west divide on the issue as well as Walker's general distaste for political populism; Walker's position was supported by conservative bankers and statesmen like Henry Lee Higginson

, George F. Hoar, John M. Forbes, and Henry Cabot Lodge

.

criticized the third edition (1888) for being devoid of facts, figures, and mostly full of off-the-cuff judgments on the practices and capacities of native Americans and immigrants, but generally embodying the state of the art of economics at the time.

Walker also took an interest in demographics later in his career, particularly towards the issues of immigration and birth rates. He published The Growth of the United States in 1882 and Restriction on Immigration in 1896 arguing for increasing restrictions out of concern about the diminished industrial and intellectual capacity of the most recent wave of immigrants. Walker also argued that unrestricted immigration was the major reason behind nineteenth-century native American fertility decline, but while the argument was politically popular and became widely accepted in mobilizing restrictions on immigration, it rested upon a surprisingly facile statistical analysis that was later refuted.

Based upon his experiences in the military, Walker published two books describing the history of the Second Army Corps (1886) as well as a biography of General Winfield Scott Hancock

(1884). Walker was elected Commander of the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

in 1883 was also the President of the National Military Historical Association.

Established in 1861 and opened in 1865, the financial position of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Established in 1861 and opened in 1865, the financial position of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

(MIT) was severely undermined following the Panic of 1873

and subsequent Long Depression

. Seventy-five year-old founder William Barton Rogers

was elected interim president in 1878 after John Daniel Runkle

stepped down. Rogers wrote Walker in June 1880 to offer him the Presidency and Walker evidently debated the opportunity for some time as Rogers sent followup inquiries in January and February 1881 requesting his committed decision. Walker ultimately accepted in early May and was formally elected President by the MIT Corporation on May 25, 1881, resigning his Yale appointment in June and his Census directorship in November. However, the assassination attempt on President Garfield in July 1881 and the ensuing illness before his death in September upset Walker's transition and delayed his formal introduction to the faculty of MIT until November 5, 1881. On May 30, 1882, during Walker's first Commencement exercises, Rogers died mid-speech where his last words were famously "bituminous coal

".

MIT's inability to secure a more stable financial footing during this era can largely be attributed to the existence of the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard

MIT's inability to secure a more stable financial footing during this era can largely be attributed to the existence of the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard

. Given the choice between funding technological research at the oldest university in the nation or an independent and adolescent institution, potential benefactors were indifferent or even hostile to funding MIT's competing mission. Earlier overtures from Harvard President Charles William Eliot

towards consolidation of the two schools were rejected or disrupted by Rogers in 1870 and 1878. Despite his tenure at the analogous Sheffield School, Walker remained committed to MIT's independence from the larger institution. Walker also repeatedly received overtures from Leland Stanford

to become the first president of his new university

in Palo Alto, California

but Walker remained committed to MIT owing to his Boston upbringing.

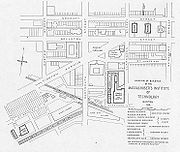

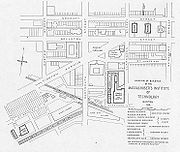

Walker sought to erect a new building on to address the increasingly cramped conditions of the original Boylston Street

Walker sought to erect a new building on to address the increasingly cramped conditions of the original Boylston Street

campus located near Copley Square

. Because the stipulations of the original land grant prevented MIT from covering more than two-ninths of its current lot, Walker announced his intention to build the industrial expansion on a lot directly across from the Trinity Church

fully intending that their opposition would lead to favorable terms for selling the proposed land and funding construction elsewhere. With the financial health of the Institute only beginning to recover, Walker began construction on the partially funded expansion fully expecting the immediacy of the project to be a persuasive tool for raising its funds. The strategy was only partially successful as the 1883 building had laboratory facilities that were second-to-none but also lacked the outward architectural grandeur of its sister building and was generally considered an eyesore on its surroundings. Mechanical shops were moved out of the Rogers Building in the mid 1880s to accommodate other programs and in 1892 the Institute began construction on another Copley Square building. New programs were also launched under Walker's tenure: Electrical Engineering in 1882, Chemical Engineering in 1888, Sanitary Engineering in 1889, Geology in 1890, Naval Architecture in 1893.

Walker also sought to improve the state of student life and alumni relations by supporting the creation of a gymnasium, dormitories, and the Technology Club which served to foster a stronger identity and loyalty among the largely commuter student body. Walker also won considerable praise from the student body by reducing the required time spent in recitation and preparation, limited the faculty to examinations lasting no longer than three hours, expanded entrance examinations to other cities, started a summer curriculum, and launched masters and doctoral graduate degree programs. These reforms were largely a response to Walker's on-going defense of the Institute and its curriculum from outside accusations of overwork, poor writing, inapplicable skills, and status as a "mere" trade school. Between 1881 and 1897, enrollments quadrupled from 302 to 1,198 students, annual degrees granted increased from 28 to 179, faculty appointments quadrupled from 38 to 156, and the endowment grew thirteenfold from $137,000 to $1,798,000 ($ to $ in 2009 dollars).

While MIT is a private institution, Walker's extensive civic activities as President set the precedent for future presidents to use the post to fulfill civic and cultural obligations throughout Boston. He served as a member of the Massachusetts Board of Education

(1882–1890), Boston School Committee (1885–1888), Boston Art Commission (1885–1897), Boston Park Commission (1890–1896), Massachusetts Historical Society

(1883–1897), and a trustee of the Boston Public Library

in 1896. Walker was committed to a variety of reforms in public and normal schools such as secular curricula, expanding the emphasis on arithmetic, reducing the emphasis on ineffectual home exercises, and increasing the pay and training of teachers.

Following a trip to a dedication in the "wilderness of Northern New York" in December 1896, Walker returned exhausted and ill. He died on January 5, 1897 as a result of apoplexy

. His funeral service was conducted at the Trinity Church and Walker was buried at Walnut Grove cemetery in North Brookfield, Massachusetts. His grave can be found in Section 1 Lot 72.

effectively made it superfluous. The medal was awarded to Wesley Clair Mitchell

in 1947, John Maurice Clark

in 1952, Frank Knight

in 1957, Jacob Viner

in 1962, Alvin Hansen

in 1967, Theodore Schultz

in 1972, and Simon Kuznets

in 1977.

Following his death, alumni and students began to raise funds to construct a monument to Walker and his fifteen years as leader of the university. Although the funds were easily raised, plans were delayed for over twenty years as MIT also made plans to move to a new campus on the western bank of the Charles River

Following his death, alumni and students began to raise funds to construct a monument to Walker and his fifteen years as leader of the university. Although the funds were easily raised, plans were delayed for over twenty years as MIT also made plans to move to a new campus on the western bank of the Charles River

in Cambridge

. The new Beaux-Arts campus opened in 1916 and featured the Walker Memorial housing a gymnasium, students' club and lounge, and a commons room.

Despite his prominence and leadership in the fields of economics, statistics, and political economy, Walker's Course IX on General Studies was dissolved shortly after his death and a seventy year debate followed over what was the appropriate role and scope of humanistic and social studies at MIT. Since 1975, all MIT undergraduate students are required to take eight classes distributed across the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences before receiving their degrees.

Economist

An economist is a professional in the social science discipline of economics. The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy...

, statistician

Statistician

A statistician is someone who works with theoretical or applied statistics. The profession exists in both the private and public sectors. The core of that work is to measure, interpret, and describe the world and human activity patterns within it...

, journalist

Journalist

A journalist collects and distributes news and other information. A journalist's work is referred to as journalism.A reporter is a type of journalist who researchs, writes, and reports on information to be presented in mass media, including print media , electronic media , and digital media A...

, educator, academic administrator, and military officer in the Union Army

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

. Walker was born into a prominent Boston family, the son of the economist and politician Amasa Walker

Amasa Walker

Amasa Walker was an American economist and United States Representative, and was the father of Francis Amasa Walker.-Biography:...

, and he graduated from Amherst College

Amherst College

Amherst College is a private liberal arts college located in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. Amherst is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution and enrolled 1,744 students in the fall of 2009...

at the age of 20. He received a commission to join the 15th Massachusetts Infantry

15th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

The 15th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served from the State of Massachusetts during the American Civil War from 1861-1864. A part of the II Corps of the Army of the Potomac, the regiment was engaged in many battles from Ball's Bluff to Petersburg, and...

and quickly rose through the ranks as an assistant adjutant general

Adjutant general

An Adjutant General is a military chief administrative officer.-Imperial Russia:In Imperial Russia, the General-Adjutant was a Court officer, who was usually an army general. He served as a personal aide to the Tsar and hence was a member of the H. I. M. Retinue...

. Walker fought in the Peninsula Campaign

Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B...

and was injured at the Battle of Chancellorsville

Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville was a major battle of the American Civil War, and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville Campaign. It was fought from April 30 to May 6, 1863, in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, near the village of Chancellorsville. Two related battles were fought nearby on...

but subsequently participated in the Bristoe

Bristoe Campaign

The Bristoe Campaign was a series of minor battles fought in Virginia during October and November 1863, in the American Civil War. Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commanding the Union Army of the Potomac, began to maneuver in an unsuccessful attempt to defeat Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern...

, Overland

Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union armies, directed the actions of the Army of the...

, and Richmond-Petersburg Campaigns

Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg Campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War...

before being captured by Confederate forces and held at the infamous Libby Prison

Libby Prison

Libby Prison was a Confederate Prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. It gained an infamous reputation for the harsh conditions under which prisoners from the Union Army were kept.- Overview :...

. In July 1866, he was nominated by President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson was the 17th President of the United States . As Vice-President of the United States in 1865, he succeeded Abraham Lincoln following the latter's assassination. Johnson then presided over the initial and contentious Reconstruction era of the United States following the American...

and confirmed by the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

for the award of the honorary grade of brevet

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

brigadier general

Brigadier general (United States)

A brigadier general in the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, is a one-star general officer, with the pay grade of O-7. Brigadier general ranks above a colonel and below major general. Brigadier general is equivalent to the rank of rear admiral in the other uniformed...

United States Volunteers

United States Volunteers

United States Volunteers also known as U.S. Volunteers, U. S. Vol., or U.S.V.Starting as early as 1861 these regiments were often referred to as the "volunteer army" of the United States but not officially named that until 1898.During the nineteenth century this was the United States federal...

, to rank from March 13, 1865, when he was age 24.

Following the war, Walker served on the editorial staff of the Springfield Republican

Springfield Republican

The Republican is a newspaper based in Springfield, Massachusetts. It is owned by Newhouse Newspapers, a division of Advance Publications. It played important roles in the United States Republican Party's founding, Charles Dow's career, and the invention of the pronoun "Ms."-Beginning:Established...

before using his family and military connections to gain appointment as the Chief of the Bureau of Statistics from 1869 to 1870 and Superintendent of the 1870 census where he published an award-winning Statistical Atlas visualizing the data for the first time. He joined Yale University

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

's Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School was founded in 1847 as a school of Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut for instruction in science and engineering. Originally named the Yale Scientific School, it was renamed in 1861 in honor of Joseph E. Sheffield, the railroad executive. The school was...

as a professor of political economy

Political economy

Political economy originally was the term for studying production, buying, and selling, and their relations with law, custom, and government, as well as with the distribution of national income and wealth, including through the budget process. Political economy originated in moral philosophy...

in 1872 and rose to international prominence serving as a chief member of the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition, American representative to the 1878 International Monetary Conference

International Monetary Conferences

The international monetary conferences were a series of assemblies held in the second half of the 19th century. They were held with a view to reaching agreement on matters relating to international banking...

, President of the American Statistical Association

American Statistical Association

The American Statistical Association , is the main professional US organization for statisticians and related professions. It was founded in Boston, Massachusetts on November 27, 1839, and is the second oldest, continuously operating professional society in the United States...

in 1882, and inaugural President of the American Economic Association

American Economic Association

The American Economic Association, or AEA, is a learned society in the field of economics, headquartered in Nashville, Tennessee. It publishes one of the most prestigious academic journals in economics: the American Economic Review...

in 1886, and vice president of the National Academy of Sciences

United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences is a corporation in the United States whose members serve pro bono as "advisers to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine." As a national academy, new members of the organization are elected annually by current members, based on their distinguished and...

in 1890. Walker also led the 1880 census which resulted in a twenty-two volume census, cementing Walker's reputation as the nation's preeminent statistician.

As an economist, Walker debunked the wage-fund doctrine

Wage-fund doctrine

The Wage-Fund Doctrine is an expression that comes from early economic theory that seeks to show that the amount of money a worker earns in wages, paid to them from a fixed amount of funds available to employers each year , is determined by the relationship of wages and capital to any changes in...

and engaged in a prominent scholarly debate with Henry George

Henry George

Henry George was an American writer, politician and political economist, who was the most influential proponent of the land value tax, also known as the "single tax" on land...

on land, rent, and taxes. Although Walker argued that obligations existed between the employer and the employed, he was an opponent of the nascent socialist movement and argued in support of bimetallism

Bimetallism

In economics, bimetallism is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent both to a certain quantity of gold and to a certain quantity of silver; such a system establishes a fixed rate of exchange between the two metals...

. He published his International Bimetallism at the height of the 1896 presidential election campaign

United States presidential election, 1896

The United States presidential election held on November 3, 1896, saw Republican William McKinley defeat Democrat William Jennings Bryan in a campaign considered by political scientists to be one of the most dramatic and complex in American history....

in which economic issues were prominent. Walker was a prolific writer, authoring ten books on political economy and military history. In recognition of his contributions to economic theory, beginning in 1947, the American Economic Association recognized the lifetime achievement of an individual economist with a "Francis A. Walker Medal".

Walker accepted the presidency of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a private research university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT has five schools and one college, containing a total of 32 academic departments, with a strong emphasis on scientific and technological education and research.Founded in 1861 in...

in 1881, a position he held for fifteen years until his death. During his tenure, he placed the institution on more stable financial footing by aggressively fund-raising and securing grants from the Massachusetts government and implemented many curricular reforms, oversaw the launch of new academic programs, and expanded the size of the Boston campus, faculty, and student enrollments. MIT's Walker Memorial Hall, a former students' clubhouse and one of the original buildings on the Charles River campus, was dedicated to him in 1916.

Background

Walker was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the youngest son of Hanna (née Ambrose) and Amasa WalkerAmasa Walker

Amasa Walker was an American economist and United States Representative, and was the father of Francis Amasa Walker.-Biography:...

, a prominent economist and state politician. The Walkers had three children, Emma (born 1835), Robert (born 1837), and Francis. Because the Walkers' next-door neighbor was Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. was an American physician, professor, lecturer, and author. Regarded by his peers as one of the best writers of the 19th century, he is considered a member of the Fireside Poets. His most famous prose works are the "Breakfast-Table" series, which began with The Autocrat...

, the junior Walker and junior Holmes

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1902 to 1932...

were playmates as young children and renewed their friendship later in life. The family moved from Boston to North Brookfield, Massachusetts

North Brookfield, Massachusetts

North Brookfield is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 4,680 at the 2010 census.For geographic and demographic information on the census-designated place North Brookfield, please see the article North Brookfield , Massachusetts.- History :North Brookfield...

in 1843 and remained there. As a boy he had both a noted temper as well as a magnetic personality.

Beginning his schooling at the age of seven, Walker studied Latin at various private and public schools in Brookfield before being sent to the Leicester Academy when he was twelve. He completed his college preparation by the time he was fourteen and spent another year studying Greek and Latin under the future suffragist and abolitionist Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone was a prominent American abolitionist and suffragist, and a vocal advocate and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone was the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a college degree. She spoke out for women's rights and against slavery at a time when women were discouraged...

, and entered Amherst College

Amherst College

Amherst College is a private liberal arts college located in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. Amherst is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution and enrolled 1,744 students in the fall of 2009...

at the age of fifteen. Although he had planned to matriculate at Harvard

Harvard College

Harvard College, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is one of two schools within Harvard University granting undergraduate degrees...

after his first year at Amherst, Walker's father believed his son was too young to enter the larger college and insisted he remain at Amherst. While he had entered with the class of '59, Walker became ill during his first year there and fell back a year. He was a member of the Delta Kappa and Athenian societies as a freshman, joined and withdrew from Alpha Sigma Phi

Alpha Sigma Phi

Alpha Sigma Phi Fraternity is a social fraternity with 71 active chapters and 9 colonies. Founded at Yale in 1845, it is the 10th oldest fraternity in the United States....

as a sophomore on account of "rowdyism", and finally joined Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon is a fraternity founded at Yale College in 1844 by 15 men of the sophomore class who had not been invited to join the two existing societies...

. As a student, Walker was awarded the Sweetser Essay Prize and the Hardy Prize for extemporaneous speaking

Extemporaneous speaking

Extemporaneous Speaking, also known as extemp, is a competitive event popular in United States high schools and colleges, in which students speak persuasively or informatively about current events and politics...

. He graduated in 1860 as Phi Beta Kappa with a degree in law. After graduation, he joined the law firm of Charles Devens

Charles Devens

Charles Devens was an American lawyer, jurist and statesman. He also served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.-Early life and career:...

and George Frisbie Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar was a prominent United States politician and United States Senator from Massachusetts. Hoar was born in Concord, Massachusetts...

in Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester is a city and the county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, as of the 2010 Census the city's population is 181,045, making it the second largest city in New England after Boston....

.

15th Massachusetts Infantry

As tensions between the North and South increased over the winter of 1860–1861, Walker equipped himself and began drilling with Major Devens' 3rd Battalion of Rifles in Worcester and New York. Despite his older brother Robert serving in the 34th Massachusetts Infantry, his father objected to his youngest son mobilizing with the first wave of volunteers. Walker returned to Worcester but began to lobby William SchoulerWilliam Schouler

William Schouler was an American journalist, politician and general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.-Biography:...

and Governor

Governor of Massachusetts

The Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the executive magistrate of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States. The current governor is Democrat Deval Patrick.-Constitutional role:...

John Andrew

John Albion Andrew

John Albion Andrew was a U.S. political figure. He served as the 25th Governor of Massachusetts between 1861 and 1866 during the American Civil War. He was a guiding force behind the creation of some of the first U.S. Army units of black men—including the famed 54th Massachusetts Infantry.-Early...

to grant him a commission as a second lieutenant under Devens' command of the 15th Massachusetts. Following his 21st birthday and the First Battle of Bull Run

First Battle of Bull Run

First Battle of Bull Run, also known as First Manassas , was fought on July 21, 1861, in Prince William County, Virginia, near the City of Manassas...

in July 1861, Walker secured the consent of his father to join the war effort as well as assurances by Devens that he would receive an officer's commission. However, the lieutenancy never materialized and Devens instead offered Walker an appointment as a sergeant major

Sergeant Major

Sergeants major is a senior non-commissioned rank or appointment in many militaries around the world. In Commonwealth countries, Sergeants Major are usually appointments held by senior non-commissioned officers or warrant officers...

, which he assumed on August 1, 1861, after re-tailoring his previously ordered lieutenant's uniform to reflect his enlisted status. However, by September 14, 1861, Walker had been recommended by Devens and reassigned to Brig. Gen.

Brigadier general (United States)

A brigadier general in the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, is a one-star general officer, with the pay grade of O-7. Brigadier general ranks above a colonel and below major general. Brigadier general is equivalent to the rank of rear admiral in the other uniformed...

Darius N. Couch

Darius N. Couch

Darius Nash Couch was an American soldier, businessman, and naturalist. He served as a career U.S. Army officer during the Mexican-American War, the Second Seminole War, and as a general officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War.During the Civil War, Couch fought notably in the...

as assistant adjutant general

Adjutant general

An Adjutant General is a military chief administrative officer.-Imperial Russia:In Imperial Russia, the General-Adjutant was a Court officer, who was usually an army general. He served as a personal aide to the Tsar and hence was a member of the H. I. M. Retinue...

and promoted to captain. Walker remained in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, over the winter of 1861–1862 and did not see combat until May 1862 at the Battle of Williamsburg

Battle of Williamsburg

The Battle of Williamsburg, also known as the Battle of Fort Magruder, took place on May 5, 1862, in York County, James City County, and Williamsburg, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War...

. Walker also served at Seven Pines

Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of an offensive up the Virginia Peninsula by Union Maj. Gen....

as well as at the Seven Days Battles

Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles was a series of six major battles over the seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, away from...

of the Peninsula Campaign

Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B...

in the summer of 1862 under Maj. Gen.

Major general (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Marine Corps, and United States Air Force, major general is a two-star general-officer rank, with the pay grade of O-8. Major general ranks above brigadier general and below lieutenant general...

George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

in the Army of the Potomac

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the major Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War.-History:The Army of the Potomac was created in 1861, but was then only the size of a corps . Its nucleus was called the Army of Northeastern Virginia, under Brig. Gen...

.

Second Army Corps

Walker remained at the Berkeley PlantationBerkeley Plantation

Berkeley Plantation, one of the first great estates in America, comprises about on the banks of the James River on State Route 5 in Charles City County, Virginia. Berkeley Plantation was originally called Berkeley Hundred and named after one of its founders of the 1618 land grant, Richard Berkeley...

until his promotion on August 11 to major

Major (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, major is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel...

and transferral with General Couch to the II Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Although the II Corps later saw action at the battles of Antietam

Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam , fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek, as part of the Maryland Campaign, was the first major battle in the American Civil War to take place on Northern soil. It was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, with about 23,000...

and Fredericksburg

Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, between General Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside...

, the latter being under the new command of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside was an American soldier, railroad executive, inventor, industrialist, and politician from Rhode Island, serving as governor and a U.S. Senator...

, Walker and the Corps did not join Burnsides's Mud March

Mud March (American Civil War)

The Mud March was an abortive attempt at a winter offensive in January 1863 by Union Army Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside in the American Civil War....

over the winter. Walker was promoted to lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Air Force, and United States Marine Corps, a lieutenant colonel is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of major and just below the rank of colonel. It is equivalent to the naval rank of commander in the other uniformed services.The pay...

on January 1, 1863, and remained with the II Corps. He fought the Battle of Chancellorsville

Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville was a major battle of the American Civil War, and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville Campaign. It was fought from April 30 to May 6, 1863, in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, near the village of Chancellorsville. Two related battles were fought nearby on...

in May 1863, where his hand and wrist were shattered and neck lacerated by an exploding shell. A record of the 1880 Census indicated that he had "compound fracture of the metacarpal bones of the left hand resulting in permanent extension of his hand." Later in 1896, as the President of MIT, he would receive one of the first radiographs in the country, which documented the extent of the damage to his hand. He did not return to service until August 1863. Walker participated in the Bristoe Campaign

Bristoe Campaign

The Bristoe Campaign was a series of minor battles fought in Virginia during October and November 1863, in the American Civil War. Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commanding the Union Army of the Potomac, began to maneuver in an unsuccessful attempt to defeat Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern...

and narrowly escaped encirclement during the Battle of Bristoe Station

Battle of Bristoe Station

The Battle of Bristoe Station was fought on October 14, 1863, at Bristoe Station, Virginia, between Union forces under Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren and Confederate forces under Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill during the Bristoe Campaign of the American Civil War...

before withdrawing and encamping near the Berry Hill Plantation

Berry Hill Plantation

Berry Hill Plantation, also known simply as Berry Hill, is located in Halifax County, Virginia, USA, near South Boston. It was one of the largest plantations to ever exist in Virginia. The plantation was originally owned by Isaac Coles, and began using black slaves in 1803. In 1814 and 1841, the...

for much of the winter and spending some leave in the North.

After extensive reorganization during the winter of 1863–1864, Walker and the Army of the Potomac fought in the Overland Campaign

Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union armies, directed the actions of the Army of the...

through May and June 1864. The Battle of Cold Harbor

Battle of Cold Harbor

The Battle of Cold Harbor was fought from May 31 to June 12, 1864 . It was one of the final battles of Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign during the American Civil War, and is remembered as one of American history's bloodiest, most lopsided battles...

in early June took a substantial toll on the ranks of the II Corps and Walker injured his knee during the battle. In the ensuing Richmond-Petersburg Campaign

Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg Campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War...

, Walker was appointed a brevet

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

colonel

Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, colonel is a senior field grade military officer rank just above the rank of lieutenant colonel and just below the rank of brigadier general...

. However, on August 25, 1864, as he rode to find Maj. Gen. John Gibbon

John Gibbon

John Gibbon was a career United States Army officer who fought in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.-Early life:...

at the front during the Second Battle of Ream's Station

Second Battle of Ream's Station

The Second Battle of Ream's Station was fought during the Siege of Petersburg in the American Civil War on August 25, 1864, in Dinwiddie County, Virginia. A Union force under Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock began destroying part of the Weldon Railroad, which was a vital supply line for Gen. Robert...

, Walker was surrounded and captured by the 11th Georgia Infantry. On August 27, Walker was able to escape from a marching prisoner column with another prisoner but was recaptured by the 51st North Carolina Infantry after trying to swim across the Appomattox River

Appomattox River

The Appomattox River is a tributary of the James River, approximately long, in central and eastern Virginia in the United States, named for the Appomattocs Indian tribe who lived along its lower banks in the 17th century...

and nearly drowning. After being held as a prisoner in Petersburg

Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city in Virginia, United States located on the Appomattox River and south of the state capital city of Richmond. The city's population was 32,420 as of 2010, predominantly of African-American ethnicity...

, he was transferred to the infamous Libby Prison

Libby Prison

Libby Prison was a Confederate Prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. It gained an infamous reputation for the harsh conditions under which prisoners from the Union Army were kept.- Overview :...

in Richmond

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

, where his older brother was also held. In October 1864, Walker was released with thirty other prisoners as a part of an exchange.

Walker returned to North Brookfield to recuperate and resigned his commission on January 8, 1865, as a result of his injuries and health. At the end of the war, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock

Winfield Scott Hancock was a career U.S. Army officer and the Democratic nominee for President of the United States in 1880. He served with distinction in the Army for four decades, including service in the Mexican-American War and as a Union general in the American Civil War...

recommended that Walker be brevetted as a brigadier general of U.S. Volunteers in recognition of his meritorious services during the war and especially his gallant conduct at Chancellorsville. On July 9, 1866, Walker was nominated by President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson was the 17th President of the United States . As Vice-President of the United States in 1865, he succeeded Abraham Lincoln following the latter's assassination. Johnson then presided over the initial and contentious Reconstruction era of the United States following the American...

for the award of the honorary grade of brevet

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

brigadier general

Brigadier general (United States)

A brigadier general in the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, is a one-star general officer, with the pay grade of O-7. Brigadier general ranks above a colonel and below major general. Brigadier general is equivalent to the rank of rear admiral in the other uniformed...

, U.S. Volunteers, to rank from March 13, 1865 (when he was age 24), for gallant conduct at the battle of Chancellorsville and meritorious services during the war. The U.S. Senate confirmed the award on July 23, 1866.

Postbellum activity

By late spring 1865, Walker regained sufficient strength and began to assist his father by lecturing on political economy at Amherst as well as assisting him in the preparation of The Science of Wealth. He also taught Latin, Greek, and mathematics at the Williston Seminary in Easthampton, MassachusettsEasthampton, Massachusetts

Easthampton is the second largest city in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. The town is on the southeastern edge of an area called the Pioneer Valley near the five colleges in the college towns of Northampton and Amherst, MA...

until being offered an editorial position at the Springfield Republican

Springfield Republican

The Republican is a newspaper based in Springfield, Massachusetts. It is owned by Newhouse Newspapers, a division of Advance Publications. It played important roles in the United States Republican Party's founding, Charles Dow's career, and the invention of the pronoun "Ms."-Beginning:Established...

by Samuel Bowles

Samuel Bowles (journalist)

Samuel Bowles III was an American journalist born in Springfield, Massachusetts. Beginning in 1844 he was the publisher and editor of The Republican , a position he held until his death in 1878....

. At the Republican, Walker wrote on Reconstruction era politics, railroad regulation, and representation.

1870 Census

While his editorial career was moving forward, Walker called upon his own as well as his father's political contacts to secure an appointment under David Ames WellsDavid Ames Wells

David Ames Wells was an American engineer, textbook author, economist and advocate of low tariffs.-Biography:...

as the Chief of the U.S. Bureau of Statistics and Deputy Special Commissioner of Internal Revenue in January 1869. On January 29, 1869, Major General J.D. Cox

Jacob Dolson Cox

Jacob Dolson Cox, was a lawyer, a Union Army general during the American Civil War, and later a Republican politician from Ohio. He served as the 28th Governor of Ohio and as United States Secretary of the Interior....

, who had also previously served in McClellan's army and was currently the Secretary of the Interior

United States Secretary of the Interior

The United States Secretary of the Interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior.The US Department of the Interior should not be confused with the concept of Ministries of the Interior as used in other countries...

under President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

's administration, notified the twenty-nine-year-old Walker that he was being nominated to become the Superintendent of the 1870 census. After he was confirmed

Appointments Clause

Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, known as the Appointments Clause, empowers the President of the United States to appoint certain public officials with the "advice and consent" of the U.S. Senate...

by the Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

, Walker sought to strike a moderate reformist position free from the inefficient and unscientific methods of the 1850 and 1860 censuses; however, the required legislation was not passed and the census proceeded under the rules governing previous collections. Among the problems facing Walker included a lack of authority to determine, enforce, or control the marshals

United States Marshals Service

The United States Marshals Service is a United States federal law enforcement agency within the United States Department of Justice . The office of U.S. Marshal is the oldest federal law enforcement office in the United States; it was created by the Judiciary Act of 1789...

' personnel, methods, or timing all of which were regularly manipulated by local political interests. Additionally, the 1870 census would not only occur five years after Civil War but would also be the first in which emancipated

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly...

African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

s would be fully counted in the census.

Owing to the confluence of these problems, the Census was completed and tabulated several months behind schedule to much popular criticism, and led indirectly to a deterioration in Walker's health during the spring of 1871. Walker took leave to travel to England with Bowles that summer to recuperate and upon return that fall, despite an offer from The New York Times

The New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

to join their editorial board with an annual salary of $8,000 ($ in 2009), accepted Secretary Columbus Delano

Columbus Delano

Columbus Delano, was a lawyer and a statesman and a member of the prominent Delano family.At the age of eight, Columbus Delano's family moved to Mount Vernon in Knox County, Ohio, a place he would call home for the rest of his life. After completing his primary education, he studied law and was...

's offer to become the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs in November 1871. The appointment was simultaneously a go-around to continue to fund Walker's federal responsibilities as Census superintendent despite Congress' cessation of appropriations for the position as well as a political opportunity to replace a scandal-ridden predecessor. Walker continued to work on the Census for several years thereafter, culminating in the publication of the Statistical Atlas of the United States that was unprecedented in its use of visual statistics and maps to report the results of the Census. The Atlas won him praise from both the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

as well as a First Class medal from the International Geographical Congress

International Geographical Union

The International Geographical Union is an international geographical society. The first International Geographical Congress was held in Antwerp in 1871. Subsequent meetings led to the establishment of the permanent organization in Brussels, Belgium, in 1922. The Union has 34 Commissions and four...

.

Indian Bureau

Despite his Census-related efforts, Walker did not neglect his obligations as Indian Affairs Superintendent. In the post-war era, the government redoubled efforts to issue western land grants to settlers, ranchers, miners, and railroads which only served to heighten tensions with the Native American tribes whom had already been displaced from their homelands as well as stripped of their ostensible sovereignty following an 1872 act of Congress. The U.S. Army and various Indian tribes engaged in open hostilities throughout the 1860s and 1870s. Walker harbored no benevolence for the Indians, characterizing them as "voluptuary," "garrulous," "lazy," "cowardly in battle," and "beggar-like" even after an expedition along the Platte RiverPlatte River

The Platte River is a major river in the state of Nebraska and is about long. Measured to its farthest source via its tributary the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which in turn is a tributary of the Mississippi River which flows to...

to meet various chieftains. Walker echoed Grant's recommendation that the Native Americans be secured on reservations of limited mineral or agricultural value so they could be educated and reformed. In November 1872, an eruption of settler-Indian violence in Oregon known as the Modoc War

Modoc War

The Modoc War, or Modoc Campaign , was an armed conflict between the Native American Modoc tribe and the United States Army in southern Oregon and northern California from 1872–1873. The Modoc War was the last of the Indian Wars to occur in California or Oregon...

hastened Walker's disinterest in the position and he resigned as Commissioner on December 26, 1872 to take a faculty position at Yale. However, Walker also criticized his successors' graft, corruption, and abuse of power in subsequent years and published The Indian Question in 1874.

Other engagements

1876 was a busy year for Walker. Henry Brooks Adams sought to recruit Walker to be the Editor-in-Chief of his Boston PostBoston Post

The Boston Post was the most popular daily newspaper in New England for over a hundred years before it folded in 1956. The Post was founded in November 1831 by two prominent Boston businessmen, Charles G...

after failing to recruit Horace White

Horace White (writer)

Horace White was an United States journalist and financial expert, noted for his connection with the Chicago Tribune, the New York Evening Post and The Nation.-Biography:...

and Charles Nordhoff for the position. That spring, Walker was nominated to run for the Secretary of the State of Connecticut

Secretary of the State of Connecticut

The Secretary of the State of Connecticut is one of the constitutional officers of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is an elected position in the state government and has a term length of four years....

, running on a platform that would later be embodied by the "Mugwump

Mugwump

The Mugwumps were Republican political activists who bolted from the United States Republican Party by supporting Democratic candidate Grover Cleveland in the United States presidential election of 1884. They switched parties because they rejected the financial corruption associated with Republican...

" movement, but ultimately lost to Marvin H. Sanger by a margin of 7,200 votes out of 99,000 cast. In the summer, the faculty of Amherst attempted to recruit him to become the President, but the position went instead to the Rev. Julius Hawley Seelye

Julius Hawley Seelye

Julius Hawley Seelye was a missionary, author, United States Representative, and former president of Amherst College. The system of Latin Honors in use at many universities worldwide is said to have been created by him....

to appease the more conservative trustees.

Walker's rise to prominence was further accelerated by his appointment by Charles Francis Adams, Jr.

Charles Francis Adams, Jr.

Charles Francis Adams II was a member of the prominent Adams family, and son of Charles Francis Adams, Sr. He served as a colonel in the Union Army during the American Civil War...

as the Chief of the Bureau of Awards at the 1876 Centennial Exposition

Centennial Exposition

The Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, the first official World's Fair in the United States, was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from May 10 to November 10, 1876, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. It was officially...

in Philadelphia. Previous world expositions in Europe were fraught with national factionalism and a superabundance of awards. Walker imposed a much leaner operation replacing juries with judges and being more selective in awarding prizes. Walker won formal international recognition when he was named a "Knight Commander" by Sweden and Norway and a "Comendador" by Spain. He was also invited to serve as Assistant Commissioner General for the 1878 Paris Exposition

Exposition Universelle (1878)

The third Paris World's Fair, called an Exposition Universelle in French, was held from 1 May through to 10 November 1878. It celebrated the recovery of France after the 1870 Franco-Prussian War.-Construction:...

. The Centennial Exposition affected Walker's later career by greatly increasing his interest in technical education as well as introducing him to MIT President John D. Runkle and Treasurer John C. Cummings

John C. Cummings

John Cummings served as the president of Shawmut Bank for 32 years, from 1868 until 1898. Owner of a farm and tannery in Woburn, Massachusetts. John Cummings also served in both the Massachusetts House of Representatives and Massachusetts Senate. He ran for Congress, unsuccessfully, in 1876...

.

1880 Census

Walker accepted a re-appointment as the superintendent of the 1880 Census because a new law, spearheaded by CongressmanOhio's 19th congressional district

Ohio's 19th congressional district was created following the 1830 census and was eliminated after the 2000 census.From 1992-2002 it included all of Lake County and Ashtabula County together with a collection of Eastern suburbs of Cleveland...

James A. Garfield, had been passed to allow him to appoint trained census enumerators free from political influence. Notably, the 1880 Census's results suggested population throughout the Southern states had increased improbably over Walker's 1870 census but an investigation revealed that the latter had been inaccurately enumerated. Walker publicized the discrepancy even as it effectively discredited the accuracy his 1870 work. The tenth Census resulted in the publication of twenty-two volumes, was popularly regarded as the best census of any up to that time, and definitively established Walker's reputation as the preeminent statistician in the nation. The Census was again delayed as a result of its size and was the subject of praise and criticism on its comprehensiveness and relevance. Walker also used the position as a bully pulpit

Bully pulpit

A bully pulpit is a public office or other position of authority of sufficiently high rank that provides the holder with an opportunity to speak out and be listened to on any matter...

to advocate for the creation of a permanent Census Bureau

United States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau is the government agency that is responsible for the United States Census. It also gathers other national demographic and economic data...