Flying boat

Encyclopedia

Seaplane

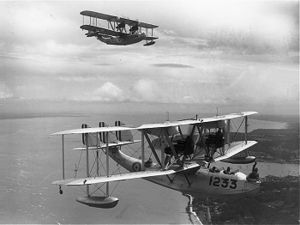

A seaplane is a fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing on water. Seaplanes that can also take off and land on airfields are a subclass called amphibian aircraft...

with a hull

Hull (watercraft)

A hull is the watertight body of a ship or boat. Above the hull is the superstructure and/or deckhouse, where present. The line where the hull meets the water surface is called the waterline.The structure of the hull varies depending on the vessel type...

, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a float plane as it uses a purpose-designed fuselage

Fuselage

The fuselage is an aircraft's main body section that holds crew and passengers or cargo. In single-engine aircraft it will usually contain an engine, although in some amphibious aircraft the single engine is mounted on a pylon attached to the fuselage which in turn is used as a floating hull...

which can float, granting the aircraft buoyancy

Buoyancy

In physics, buoyancy is a force exerted by a fluid that opposes an object's weight. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus a column of fluid, or an object submerged in the fluid, experiences greater pressure at the bottom of the...

. Flying boats may be stabilized by under-wing floats or by wing-like projections (called sponson

Sponson

Sponsons are projections from the sides of a watercraft, for protection, stability, or the mounting of equipment such as armaments or lifeboats, etc...

s) from the fuselage. Flying boats were some of the largest aircraft of the first half of the 20th century, superseded in size only by bomber

Bomber

A bomber is a military aircraft designed to attack ground and sea targets, by dropping bombs on them, or – in recent years – by launching cruise missiles at them.-Classifications of bombers:...

s developed during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. Their advantage lay in using water instead of expensive land-based runways, making them the basis for international airline

Airline

An airline provides air transport services for traveling passengers and freight. Airlines lease or own their aircraft with which to supply these services and may form partnerships or alliances with other airlines for mutual benefit...

s in the interwar period

Interwar period

Interwar period can refer to any period between two wars. The Interbellum is understood to be the period between the end of the Great War or First World War and the beginning of the Second World War in Europe....

. They were also commonly used for maritime patrol and air-sea rescue

Air-sea rescue

Air-sea rescue is the coordinated search and rescue of the survivors of emergency water landings as well as people who have survived the loss of their sea-going vessel. ASR can involve a wide variety of resources including seaplanes, helicopters, submarines, rescue boats and ships...

.

The craft class or type came about after The Daily Mail offered a large monetary prize for an aircraft with transoceanic range in 1914. This prompted a collaboration between British and American air pioneers, resulting in the Curtiss Model H

Curtiss Model H

The Curtiss Model H was a family of classes of early long-range flying boats, the first two of which were developed directly on commission in the United States in response to the ₤10,000 prize challenge issued in 1913 by the London newspaper, the Daily Mail, for the first non-stop aerial crossing...

. Following World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, their use gradually tailed off, partially because of the investments in airports during the war. In the 21st century, flying boats maintain a few niche uses, such as for dropping water on forest fires, air transport around archipelagos, and access to undeveloped or roadless areas. Many modern seaplane variants, whether float or flying boat types are convertible amphibians—planes where either landing gear or flotation modes may be used to land and take off.

Origins

Henri FabreHenri Fabre

Henri Fabre was a French aviator and the inventor of Le Canard, the first seaplane in history.Henri Fabre was born into a prominent family of shipowners in the city of Marseilles. He was educated in the Jesuit College of Marseilles, where he undertook advanced studies in sciences. He then studied...

, a French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

aviator, invented and successfully flight tested a seaplane

Seaplane

A seaplane is a fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing on water. Seaplanes that can also take off and land on airfields are a subclass called amphibian aircraft...

which he named Le Canard

Le Canard

|-See also:-References:* The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft , 1985, Orbis Publishing-External links:*...

; it is acknowledged as the first seaplane in history. It was a "landmark" invention that inspired other aviators. Over the next few years, Fabre designed "Fabre floats" for several other flyers. American pioneer aviator Glenn Curtiss

Glenn Curtiss

Glenn Hammond Curtiss was an American aviation pioneer and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle then motorcycle builder and racer, later also manufacturing engines for airships as early as 1906...

had built experimental floatplane

Floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane, with slender pontoons mounted under the fuselage; only the floats of a floatplane normally come into contact with water, with the fuselage remaining above water...

s before 1910, without proceeding to flight testing. But after Fabre's successful seaplane flights, Curtiss focused mainly on land-based aircraft. He made only small experimental models of floatplanes, and slowly improved upon his earlier work.

In 1911 Curtiss unveiled a development of his floatplane experiments married to a larger version of his successful Curtiss Model D

Curtiss Model D

|-See also:-External links:...

land plane, but with a larger engine and a rudimentary hull

Hull (watercraft)

A hull is the watertight body of a ship or boat. Above the hull is the superstructure and/or deckhouse, where present. The line where the hull meets the water surface is called the waterline.The structure of the hull varies depending on the vessel type...

and fuselage, designated as the Model E

Curtiss Model E

-References:* * *...

. The was the first air plane with a hull, and arguably the creation of the "flying boat" type that dominated long distance air travel for the next four to five decades. Consequently he soon became acquainted with others interested in both seaplane based and long range commercial aviation development two aspects which were hopelessly interrelated in those days when airports were yet to be built throughout most of the world. The design also brought him in contact with Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant Commander is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander...

John Cyril Porte

John Cyril Porte

Lieutenant Commander John Cyril Porte CMG, DSM, Royal Navy was a flying boat pioneer associated with the World War I Seaplane Experimental Station at Felixstowe.-Biography:...

RN

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

, an influential British aviation pioneer.

In February 1911, the United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

took delivery of its very first airplane, a Curtiss Model E, and soon tested landing and take-offs from ships using the Curtiss Model D.

The 1913 prizes

In 1913, London's Daily MailDaily Mail

The Daily Mail is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper owned by the Daily Mail and General Trust. First published in 1896 by Lord Northcliffe, it is the United Kingdom's second biggest-selling daily newspaper after The Sun. Its sister paper The Mail on Sunday was launched in 1982...

newspaper put up a ₤10,000 prize

Daily Mail aviation prizes

Between 1907 and 1925 the Daily Mail newspaper, initially on the initiative of its proprietor Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe, awarded numerous prizes for achievements in aviation. The newspaper would stipulate the amount of a prize for the first aviators to perform a particular task in...

for the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic which was soon "enhanced by a further sum" from the "Women's Aerial League of Great Britain". American businessman Rodman Wanamaker

Rodman Wanamaker

Lewis Rodman Wanamaker was a Republican and was a Presidential Elector for Pennsylvania in 1916. Wanamaker created aviation history by financing a two plane experimental seaplane class in response to a prize contest announcement by London's The Daily Mail newspaper in 1913 – the flying boat...

became determined that the prize should go to an American aircraft and commissioned the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company was an American aircraft manufacturer that went public in 1916 with Glenn Hammond Curtiss as president. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the company was the largest aircraft manufacturer in the United States...

to design and build two aircraft capable of making the flight. In Great Britain in 1913, similarly, the boat building firm J. Samuel White

J. Samuel White

J. Samuel White was a British shipbuilding firm based in Cowes, taking its name from John Samuel White . It came to prominence during the Victorian era...

of Cowes

Cowes

Cowes is an English seaport town and civil parish on the Isle of Wight. Cowes is located on the west bank of the estuary of the River Medina facing the smaller town of East Cowes on the east Bank...

on the Isle of Wight

Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight is a county and the largest island of England, located in the English Channel, on average about 2–4 miles off the south coast of the county of Hampshire, separated from the mainland by a strait called the Solent...

set up a new aircraft division and produced a flying boat in the United Kingdom. This was displayed at the London Air Show at Olympia in 1913. In that same year, a collaboration between the S. E. Saunders boatyard of East Cowes

East Cowes

East Cowes is a town and civil parish to the north of the Isle of Wight, on the east bank of the River Medina next to its neighbour on the west bank, Cowes....

and the Sopwith Aviation Company

Sopwith Aviation Company

The Sopwith Aviation Company was a British aircraft company that designed and manufactured aeroplanes mainly for the British Royal Naval Air Service, Royal Flying Corps and later Royal Air Force in the First World War, most famously the Sopwith Camel...

produced the "Bat Boat", an aircraft with a consuta

Consuta

Consuta was a revolutionary form of construction of watertight hulls for boats and marine aircraft, comprising four veneers of mahogany planking interleaved with waterproofed calico and stitched together with copper wire....

laminated hull that could operate from land or on water, which today we call amphibious aircraft

Amphibious aircraft

An amphibious aircraft or amphibian is an aircraft that can take off and land on either land or water. Fixed-wing amphibious aircraft are seaplanes that are equipped with retractable wheels, at the expense of extra weight and complexity, plus diminished range and fuel economy compared to planes...

. The "Bat Boat" completed several landings on sea and on land and was duly awarded the Mortimer Singer Prize. It was the first all-British aeroplane capable of making six return flights over five miles within five hours.

In America, Wanamaker's commission built on Glen Curtiss' previous development and experience with the Model E for the U.S. Navy and soon resulted in the Model H

Curtiss Model H

The Curtiss Model H was a family of classes of early long-range flying boats, the first two of which were developed directly on commission in the United States in response to the ₤10,000 prize challenge issued in 1913 by the London newspaper, the Daily Mail, for the first non-stop aerial crossing...

. The H series began as a conventional biplane

Biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two superimposed main wings. The Wright brothers' Wright Flyer used a biplane design, as did most aircraft in the early years of aviation. While a biplane wing structure has a structural advantage, it produces more drag than a similar monoplane wing...

design with two-bay, unstaggered wings of unequal span with two tractor (pulling, not pushing) inline engines

Inline engine (aviation)

In aviation, an inline engine means any reciprocating engine with banks rather than rows of cylinders, including straight engines, flat engines, V engines and H engines, but excluding radial engines and rotary engines....

mounted side-by-side above the fuselage

Fuselage

The fuselage is an aircraft's main body section that holds crew and passengers or cargo. In single-engine aircraft it will usually contain an engine, although in some amphibious aircraft the single engine is mounted on a pylon attached to the fuselage which in turn is used as a floating hull...

in the interplane gap. Wingtip pontoons were attached directly below the lower wings near their tips. The Model H resembled Curtiss' earlier flying boat designs, but was built considerably larger so it could carry enough fuel to cover 1100 mi (1,770.3 km). The three crew members were accommodated in a fully enclosed cabin.

Trials of the Model H (christened America) began in June 1914, with Lt. Cmdr. Porte as test pilot. Testing soon revealed a serious shortcoming in the design; especially the tendency for the nose of the aircraft to try to submerge as engine power increased while taxiing on water. This phenomenon had not been encountered before, since Curtiss' earlier designs had not used such powerful engines nor large fuel/cargo loads and so were relatively much more buoyant. In order to counteract this effect, Curtiss fitted fins to the sides of the bow to add hydrodynamic lift, but soon replaced these with sponson

Sponson

Sponsons are projections from the sides of a watercraft, for protection, stability, or the mounting of equipment such as armaments or lifeboats, etc...

s, a type of underwater pontoon mounted in pairs on either side of a hull, to add more buoyancy. These sponsons (or their engineering equivalents) would remain a prominent feature of flying boat hull design in the decades to follow. With the problem resolved, preparations for the crossing resumed. While the craft was found to handle "heavily" on take-off, and required rather longer take-off distances than expected, 5 August 1914 was selected as the trans-Atlantic flight date. Porte was to pilot the America.

British and American developments

Curtiss and Porte's plans were interrupted by the outbreak of World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. Porte was recalled to service with the Royal Naval Air Service

Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service or RNAS was the air arm of the Royal Navy until near the end of the First World War, when it merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps to form a new service , the Royal Air Force...

. He became commander of the Seaplane Experimental Station

Seaplane Experimental Station

The Seaplane Experimental Station at Royal Naval Air Station Felixstowe was a British aircraft design unit of the early part of the 20th century.-Creation:...

at Felixstowe

Felixstowe

Felixstowe is a seaside town on the North Sea coast of Suffolk, England. The town gives its name to the nearby Port of Felixstowe, which is the largest container port in the United Kingdom and is owned by Hutchinson Ports UK...

in 1915.

Impressed by the capabilities he had witnessed, Porte persuaded the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

to commandeer (and later, purchase) the America and her sister from Curtiss. This was followed by an order for 12 more similar aircraft, one Model H-2 and the remaining as Model H-4's. Four examples of the latter were actually assembled in the UK by Saunders

Saunders-Roe

Saunders-Roe Limited was a British aero- and marine-engineering company based at Columbine Works East Cowes, Isle of Wight.-History:The name was adopted in 1929 after Alliot Verdon Roe and John Lord took a controlling interest in the boat-builders S.E. Saunders...

. All of these were essentially identical to the design of the America, and indeed, were all referred to as Americas in Royal Navy service. The initial batch was followed by an order for 50 more (totalling 64 Americas overall during the war).

Porte also acquired permission to modify and experiment with the Curtiss aircraft.

At Felixstowe, Porte made advancements to flying boat design and developed a practical hull design with the distinctive "Felixstowe notch". The notch could be added to Curtiss' airframe and engine design, creating the Atlantic or Type A flying boat (as it became known in Great Britain). After that initial mass upgrade Porte modified the H4 with a new hull with improved hydrodynamic qualities. This design was later designated the Felixstowe F.1

Felixstowe F.1

-External links:*...

, of which only four were built, as they were deemed underpowered for arduous North Atlantic patrol conditions.

Consequently, Curtiss was asked to develop a larger flying boat, which was designated the "Large America" or Curtiss Model H8 when it became available in 1917, but when some H8s were tested at Felixstowe, they too were found to be underpowered. Porte soon upgraded the H8s with 250 HP Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce Limited

Rolls-Royce Limited was a renowned British car and, from 1914 on, aero-engine manufacturing company founded by Charles Stewart Rolls and Henry Royce on 15 March 1906 as the result of a partnership formed in 1904....

Eagle engines and replaced the hulls with a larger Felixstowe hull variant. These became the Felixstowe F.2 and F.2a variants and saw both wide use and long service.

The innovation of the "Felixstowe notch" enabled the craft to overcome suction from the water more quickly and break free for flight much more easily. This made operating the craft far safer and more reliable.

The "notch" breakthrough would soon after evolve into a "step", with the rear section of the lower hull sharply recessed above the forward lower hull section, and that characteristic became a feature of both flying boat hulls and seaplane floats. The resulting aircraft would be large enough to carry sufficient fuel to fly long distances and could berth alongside ships for refueling.

After several years of war development and upon getting negative reports on the H-8, Curtiss produced upscaled flying boats which by 1917 were designated as the Curtiss Model H12. Porte then designed a similar hull for the H12, designated the Felixstowe F.2a, which was greatly superior to the original Curtiss boat. This entered production and service with about 100 being completed by the end of the War. Another seventy were built later, and these were followed by two F.2c also built at Felixstowe.

In February 1917, the first prototype of the Felixstowe F.3

Felixstowe F.3

-See also:-References:NotesBibliography* Bruce, J.M. "". Flight, 2 December 1955, pp.842—846.* Bruce, J.M. "". Flight, 16 December 1955, pp.895—898.* Bruce, J.M. "". Flight, 23 December 1955, pp. 929—932....

was flown. It was larger and heavier than the F.2, giving it greater range and heavier bomb load, but poorer agility. Approximately 100 Felixstowe F.3s were produced before the end of the war.

The Felixstowe F.5

Felixstowe F.5

-See also:-References:NotesBibliography* Bruce, J.M. " Flight, 2 December 1955, pp. 842—846.* Bruce, J.M. " Flight, 16 December 1955, pp. 895—898.* Bruce, J.M. " Flight, 23 December 1955, pp. 929—932....

was intended to combine the good qualities of the F.2 and F.3, with the prototype first flying in May 1918. The prototype showed superior qualities to its predecessors but, to ease production, the production version was modified to make extensive use of components from the F.3, which resulted in lower performance than the F.2A or F.5.

F.2, F.3, and F.5 flying boats were extensively employed by the Royal Navy for coastal patrols, and to search for German U-boat

U-boat

U-boat is the anglicized version of the German word U-Boot , itself an abbreviation of Unterseeboot , and refers to military submarines operated by Germany, particularly in World War I and World War II...

s.

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company was an American aircraft manufacturer that went public in 1916 with Glenn Hammond Curtiss as president. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the company was the largest aircraft manufacturer in the United States...

independently developed its designs into the small Model "F", the larger Model "K" (several of which were sold to the Russian Naval Air Service), and the Model "C" for the U.S. Navy. Curtiss among others also built the Felixstowe F.5 as the Curtiss F5L, based on the final Porte hull designs and powered by American Liberty engines.

Imperial German and Imperial Austro-Hungarian developments

Hansa-BrandenburgHansa-Brandenburg

Hansa und Brandenburgische Flugzeugwerke was a German aircraft manufacturing company that operated during World War I. It was created in May 1914 by the purchase of Brandenburgische Flugzeugwerke by Camillo Castiglioni, who relocated the factory from Libau to Brandenburg am Havel...

flying boats.

Lohner-Werke flying boats starting with the Lohner E in 1914 and later (1915) influential Lohner L versions.

Italian developments

Macchi L and M series flying boats. The original Macchi L.1 was a copy of the Austrian Lohner L flying boat of 1915.Between the wars

NC-4

The NC-4 was a Curtiss NC flying boat which was designed by Glenn Curtiss and his team, and manufactured by Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company. In May 1919, the NC-4 became the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, starting in the United States and making the crossing as far as Lisbon,...

became the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic Ocean in 1919, crossing via the Azores

Azores

The Archipelago of the Azores is composed of nine volcanic islands situated in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean, and is located about west from Lisbon and about east from the east coast of North America. The islands, and their economic exclusion zone, form the Autonomous Region of the...

. Of the four that made the attempt, only one completed the flight.

In the 1930s, flying boats made it possible to have regular air transport between the U.S. and Europe, opening up new air travel routes to South America, Africa, and Asia. Foynes

Foynes

Foynes is a village and major port in County Limerick in the midwest of Ireland, located at the edge of hilly land on the southern bank of the Shannon Estuary. The population of the town was 606 as of the 2006 census.-Foynes's role in aviation:...

, Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

and Botwood, Newfoundland and Labrador

Botwood, Newfoundland and Labrador

Northwest: Point LeamingtonNorth: Northern ArmNortheast: Bay of Exploits, Burnt Arm, LaurencetonWest: Division No. 6, Subd. CBotwoodEast: Bay of Exploits, Division No. 6, Subd. A...

were the termini for many early transatlantic flights.In areas where there were no airfields for land-based aircraft, flying boats could stop at small island, river, lake or coastal stations to refuel and resupply. The Pan Am

Pan American World Airways

Pan American World Airways, commonly known as Pan Am, was the principal and largest international air carrier in the United States from 1927 until its collapse on December 4, 1991...

Boeing 314

Boeing 314

The Boeing 314 Clipper was a long-range flying boat produced by the Boeing Airplane Company between 1938 and 1941 and is comparable to the British Short S.26. One of the largest aircraft of the time, it used the massive wing of Boeing’s earlier XB-15 bomber prototype to achieve the range necessary...

"Clipper" planes brought exotic destinations like the Far East within reach of air travelers and came to represent the romance of flight.

In 1923, the first British commercial flying boat service was introduced with flights to and from the Channel Islands

Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago of British Crown Dependencies in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two separate bailiwicks: the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Bailiwick of Jersey...

. The British aviation industry was experiencing rapid growth. The Government decided that nationalization was necessary and ordered five aviation companies to merge to form the state-owned Imperial Airways

Imperial Airways

Imperial Airways was the early British commercial long range air transport company, operating from 1924 to 1939 and serving parts of Europe but especially the Empire routes to South Africa, India and the Far East...

of London (IAL). IAL became the international flag-carrying British airline, providing flying boat passenger and mail transport links between Britain and South Africa

South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

using aircraft such as the Short S.8 Calcutta

Short S.8 Calcutta

-See also:-References:NotesBibliography* Barnes C.H. and D.N. James. Shorts Aircraft since 1900. London: Putnam, 1989. ISBN 0-85177-819-4.*The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft . London: Orbis Publishing, 1985....

.

In 1928, four Supermarine Southampton

Supermarine Southampton

-See also:-References:NotesBibliography* Andrews, C.F. and E.B. Morgan. Supermarine Aircraft since 1914 . London: Putnam, 1987. ISBN 0-85177-800-3....

flying boats of the RAF

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

Far East flight arrived in Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

. The flight was considered proof that flying boats had evolved to become reliable means of long distance transport.

By 1931, mail from Australia was reaching Britain in just 16 days - less than half the time taken by sea. In that year, government tenders on both sides of the world invited applications to run new passenger and mail services between the ends of Empire, and Qantas

Qantas

Qantas Airways Limited is the flag carrier of Australia. The name was originally "QANTAS", an initialism for "Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services". Nicknamed "The Flying Kangaroo", the airline is based in Sydney, with its main hub at Sydney Airport...

and IAL were successful with a joint bid. A company under combined ownership was then formed, Qantas Empire Airways. The new ten day service between Rose Bay, New South Wales

Rose Bay, New South Wales

Rose Bay is a harbourside, eastern suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Rose Bay is located 7 kilometres east of the Sydney central business district, in the local government areas of Waverley Municipal Council and Woollahra Council .Rose Bay has views of both the Sydney...

(near Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

) and Southampton

Southampton

Southampton is the largest city in the county of Hampshire on the south coast of England, and is situated south-west of London and north-west of Portsmouth. Southampton is a major port and the closest city to the New Forest...

was such a success with letter-writers that before long the volume of mail was exceeding aircraft storage space.

A solution to the problem was found by the British government, who in 1933 had requested aviation manufacturer Short Brothers

Short Brothers

Short Brothers plc is a British aerospace company, usually referred to simply as Shorts, that is now based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Founded in 1908, Shorts was the first company in the world to make production aircraft and was a manufacturer of flying boats during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s...

to design a big new long-range monoplane for use by IAL. Partner Qantas agreed to the initiative and undertook to purchase six of the new Short S23 "C" class or "Empire"

Short Empire

The Short Empire was a passenger and mail carrying flying boat, of the 1930s and 1940s, that flew between Britain and British colonies in Africa, Asia and Australia...

flying boats.

Delivering the mail as quickly as possible generated a lot of competition and some innovative designs. One variant of the Short Empire flying boats was the strange-looking "Maia and Mercury

Short Mayo Composite

The Short Mayo Composite was a piggy-back long-range seaplane/flying boat combination produced by Short Brothers to provide a reliable long-range air transport service to the United States and the far reaches of the British Empire and the Commonwealth....

". It was a four-engined floatplane

Floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane, with slender pontoons mounted under the fuselage; only the floats of a floatplane normally come into contact with water, with the fuselage remaining above water...

"Mercury" (the winged messenger) fixed on top of "Maia", a heavily modified Short Empire flying boat. The larger Maia took off, carrying the smaller Mercury loaded to a weight greater than it could take off with. This allowed the Mercury to carry sufficient fuel for a direct trans-Atlantic flight with the mail. Unfortunately this was of limited usefulness, and the Mercury had to be returned from America by ship. The Mercury did set a number of distance records before in-flight refuelling was adopted.

Sir Alan Cobham

Alan Cobham

Sir Alan John Cobham, KBE, AFC was an English aviation pioneer.A member of the Royal Flying Corps in World War I, Alan Cobham became famous as a pioneer of long distance aviation. After the war he became a test pilot for the de Havilland aircraft company, and was the first pilot for the newly...

devised a method of in-flight refuelling in the 1930s. In the air, the Short Empire could be loaded with more fuel than it could take off with. Short Empire flying boats serving the trans-Atlantic crossing were refueled over Foynes; with the extra fuel load, they could make a direct trans-Atlantic flight. A Handley Page H.P.54 Harrow

Handley Page H.P.54 Harrow

|-See also:-Bibliography:* Barnes, C.H. Handley Page Aircraft since 1907. London: Putnam Publishing, 1987. ISBN 0-85177-803-8.* Clayton, Donald C. Handley Page, an Aircraft Album. Shepperton, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Ltd., 1969. ISBN 0-7110-0094-8....

was used as the fuel tanker.

Sponson

Sponsons are projections from the sides of a watercraft, for protection, stability, or the mounting of equipment such as armaments or lifeboats, etc...

s, to stabilize it on the water without the need for wing-mounted outboard floats. This feature was pioneered by Claudius Dornier

Claudius Dornier

Claude Honoré Desiré Dornier born in Kempten im Allgäu was a German airplane builder and founder of Dornier GmbH...

during World War I on his Dornier Rs. I giant flying boat, and perfected on the Dornier Wal

Dornier Do J

The Dornier Do J Wal was a twin-engine German flying boat of the 1920s designed by Dornier Flugzeugwerke. The Do J was designated the Do 16 by the Reich Air Ministry under its aircraft designation system of 1933....

in 1924. The enormous Do X was powered by 12 engines and carried 170 persons. It flew to America in 1929, crossing the Atlantic via an indirect route. It was the largest flying boat of its time, but was severely underpowered and was limited by a very low operational ceiling. Only three were built, with a variety of different engines installed, in an attempt to overcome the lack of power. Two of these were sold to Italy.

World War II

The military value of flying boats was well-recognized, and every country bordering on water operated them in a military capacity at the outbreak of the war. They were utilized in various tasks from anti-submarine patrol to air-sea rescueAir-sea rescue

Air-sea rescue is the coordinated search and rescue of the survivors of emergency water landings as well as people who have survived the loss of their sea-going vessel. ASR can involve a wide variety of resources including seaplanes, helicopters, submarines, rescue boats and ships...

and gunfire spotting

Artillery observer

A military artillery observer or spotter is responsible for directing artillery fire and close air support onto enemy positions. Because artillery is an indirect fire weapon system, the guns are rarely in line-of-sight of their target, often located tens of miles away...

for battleships. Aircraft such as the PBY Catalina

PBY Catalina

The Consolidated PBY Catalina was an American flying boat of the 1930s and 1940s produced by Consolidated Aircraft. It was one of the most widely used multi-role aircraft of World War II. PBYs served with every branch of the United States Armed Forces and in the air forces and navies of many other...

, Short Sunderland

Short Sunderland

The Short S.25 Sunderland was a British flying boat patrol bomber developed for the Royal Air Force by Short Brothers. It took its service name from the town and port of Sunderland in northeast England....

, and Grumman Goose

Grumman Goose

The Grumman G-21 Goose amphibious aircraft was designed as an eight-seat "commuter" plane for businessmen in the Long Island area. The Goose was Grumman’s first monoplane to fly, its first twin-engined aircraft, and its first aircraft to enter commercial airline service...

recovered downed airmen and operated as scout aircraft over the vast distances of the Pacific Theater

Pacific Theater of Operations

The Pacific Theater of Operations was the World War II area of military activity in the Pacific Ocean and the countries bordering it, a geographic scope that reflected the operational and administrative command structures of the American forces during that period...

and Atlantic. They also sank numerous submarines and found enemy ships. In May 1941 the German battleship Bismarck

German battleship Bismarck

Bismarck was the first of two s built for the German Kriegsmarine during World War II. Named after Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, the primary force behind the German unification in 1871, the ship was laid down at the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg in July 1936 and launched nearly three years later...

was discovered by a PBY Catalina flying out of Castle Archdale Flying boat base

RAF Castle Archdale

RAF Castle Archdale, also known for a while as RAF Lough Erne was a Royal Air Force station used by the RAF and the Royal Canadian Air Force station in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland.-WWII History:...

, Lower Lough Erne

Lough Erne

Lough Erne, sometimes Loch Erne , is the name of two connected lakes in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. The lakes are widened sections of the River Erne. The river begins by flowing north, and then curves west into the Atlantic. The southern lake is further up the river and so is named Upper...

, Northern Ireland.

The largest flying boat of the war was the Blohm & Voss BV 238, which was also the heaviest plane to fly during World War II and the largest aircraft built and flown by any of the Axis Powers

Axis Powers

The Axis powers , also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, was an alignment of great powers during the mid-20th century that fought World War II against the Allies. It began in 1936 with treaties of friendship between Germany and Italy and between Germany and...

.

In November 1939, IAL was restructured into three separate companies: British European Airways

British European Airways

British European Airways or British European Airways Corporation was a British airline which existed from 1946 until 1974. The airline operated European and North African routes from airports around the United Kingdom...

, British Overseas Airways Corporation

British Overseas Airways Corporation

The British Overseas Airways Corporation was the British state airline from 1939 until 1946 and the long-haul British state airline from 1946 to 1974. The company started life with a merger between Imperial Airways Ltd. and British Airways Ltd...

(BOAC), and British South American Airways

British South American Airways

British South American Airways or British South American Airways Corporation was a state-run airline in Britain in the 1940s. It was originally called British Latin American Air Lines Ltd....

(which merged with BOAC in 1949), with the change being made official in 1 April 1940. BOAC continued to operate flying boat services from the (slightly) safer confines of Poole Harbour

Poole Harbour

Poole Harbour is a large natural harbour in Dorset, southern England, with the town of Poole on its shores. The harbour is a drowned valley formed at the end of the last ice age and is the estuary of several rivers, the largest being the Frome. The harbour has a long history of human settlement...

during wartime, returning to Southampton

Southampton

Southampton is the largest city in the county of Hampshire on the south coast of England, and is situated south-west of London and north-west of Portsmouth. Southampton is a major port and the closest city to the New Forest...

in 1947.

The Martin Company produced the prototype XPB2M Mars based on their PBM Mariner patrol bomber, with flight tests between 1941 and 1943. The Mars was converted by the Navy into a transport aircraft designated the XPB2M-1R. Satisfied with the performance, 20 of the modified JRM-1 Mars were ordered. The first, named Hawaii Mars, was delivered in June 1945, but the Navy scaled back their order at the end of World War II, buying only the five aircraft which were then on the production line. The five Mars were completed, and the last delivered in 1947.

Post World War II

Hughes H-4 Hercules

The Hughes H-4 Hercules is a prototype heavy transport aircraft designed and built by the Hughes Aircraft company. The aircraft made its only flight on November 2, 1947 and the project was never advanced beyond the single example produced...

, in development in the U.S. during the war, was even larger than the BV 238 but it did not fly until 1947. The "Spruce Goose", as the H-4 was nicknamed, was the largest flying boat ever to fly. That short 1947 hop of the "Flying Lumberyard" was to be its last, however; it became a victim of post-war cutbacks and the disappearance of its intended mission as a transatlantic transport.

In 1944, the Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

began development of a small jet-powered flying boat that it intended to use as an air defence aircraft optimised for the Pacific, where the relatively calm sea conditions made the use of seaplanes easier. By making the aircraft jet powered, it was possible to design it with a hull rather than making it a floatplane

Floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane, with slender pontoons mounted under the fuselage; only the floats of a floatplane normally come into contact with water, with the fuselage remaining above water...

. The Saunders-Roe SR.A/1

Saunders-Roe SR.A/1

|-See also:-References:*London, Peter. British Flying Boats. Stroud, UK:Sutton Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-7509-2695-3.*Mason, Francis K.The British Fighter since 1912. Annapolis, Maryland, USA:Naval Institute Press, 1992. ISBN 1-55750-082-7....

prototype first flew in 1947 and was relatively successful in terms of its performance and handling. However, by the end of the war, carrier based aircraft were becoming more sophisticated, and the need for the SR.A/1 evaporated.

During the Berlin Airlift (which lasted from June 1948 until August 1949) ten Sunderlands

Short Sunderland

The Short S.25 Sunderland was a British flying boat patrol bomber developed for the Royal Air Force by Short Brothers. It took its service name from the town and port of Sunderland in northeast England....

and two Hythes were used to transport goods from Finkenwerder

Finkenwerder

Finkenwerder is a quarter of Hamburg, Germany in the borough Hamburg-Mitte. It is the location of a plant of Airbus and its airport...

on the Elbe

Elbe

The Elbe is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Krkonoše Mountains of the northwestern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia , then Germany and flowing into the North Sea at Cuxhaven, 110 km northwest of Hamburg...

near Hamburg

Hamburg

-History:The first historic name for the city was, according to Claudius Ptolemy's reports, Treva.But the city takes its modern name, Hamburg, from the first permanent building on the site, a castle whose construction was ordered by the Emperor Charlemagne in AD 808...

to the isolated city, landing on the Havelsee beside RAF Gatow

RAF Gatow

Known for most of its operational life as Royal Air Force Station Gatow, or more commonly RAF Gatow, this former British Royal Air Force military airbase is in the district of Gatow in south-western Berlin, west of the Havel river, in the borough of Spandau...

until it iced over. The Sunderlands were particularly used for transporting salt, as their airframes were already protected against corrosion from seawater. Transporting salt in standard aircraft risked rapid and severe structural corrosion in the event of a spillage. In addition, three Aquila

Aquila Airways

Aquila Airways was a Southampton, Hampshire based British independentindependent from government-owned corporations airline, formed on 18 May 1948.-Early operations:...

flying boats were used during the airlift. This is the only known operational use of flying boats within central Europe.

After World War II the use of flying boats rapidly declined, though the U.S. Navy continued to operate them (notably the Martin P5M Marlin) until the early 1970s. The Navy even attempted to build a jet-powered seaplane bomber, the Martin Seamaster. Several factors contributed to the decline. The ability to land on water became less of an advantage owing to the considerable increase in the number and length of land based runways during World War II. Further, as the speed and range of land-based aircraft increased, the commercial competitiveness of flying boats diminished; their design compromised aerodynamic efficiency and speed to accomplish the feat of waterborne takeoff and landing. Competing with new civilian jet aircraft like the de Havilland Comet

De Havilland Comet

The de Havilland DH 106 Comet was the world's first commercial jet airliner to reach production. Developed and manufactured by de Havilland at the Hatfield, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom headquarters, it first flew in 1949 and was a landmark in aeronautical design...

and Boeing 707

Boeing 707

The Boeing 707 is a four-engine narrow-body commercial passenger jet airliner developed by Boeing in the early 1950s. Its name is most commonly pronounced as "Seven Oh Seven". The first airline to operate the 707 was Pan American World Airways, inaugurating the type's first commercial flight on...

proved impossible.

BOAC ceased flying boat services out of Southampton in November 1950.

Bucking the trend, in 1948 Aquila Airways

Aquila Airways

Aquila Airways was a Southampton, Hampshire based British independentindependent from government-owned corporations airline, formed on 18 May 1948.-Early operations:...

was founded to serve destinations that were still inaccessible to land-based aircraft. This company operated Short S.25 and Short S.45

Short Solent

- External links :* * *...

flying boats out of Southampton on routes to Madeira

Madeira

Madeira is a Portuguese archipelago that lies between and , just under 400 km north of Tenerife, Canary Islands, in the north Atlantic Ocean and an outermost region of the European Union...

, Las Palmas, Lisbon

Lisbon

Lisbon is the capital city and largest city of Portugal with a population of 545,245 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Lisbon extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of 3 million on an area of , making it the 9th most populous urban...

, Jersey

Jersey

Jersey, officially the Bailiwick of Jersey is a British Crown Dependency off the coast of Normandy, France. As well as the island of Jersey itself, the bailiwick includes two groups of small islands that are no longer permanently inhabited, the Minquiers and Écréhous, and the Pierres de Lecq and...

, Majorca, Marseilles, Capri

Capri

Capri is an Italian island in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrentine Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples, in the Campania region of Southern Italy...

, Genoa

Genoa

Genoa |Ligurian]] Zena ; Latin and, archaically, English Genua) is a city and an important seaport in northern Italy, the capital of the Province of Genoa and of the region of Liguria....

, Montreux

Montreux

Montreux is a municipality in the district of Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut in the canton of Vaud in Switzerland.It is located on Lake Geneva at the foot of the Alps and has a population, , of and nearly 90,000 in the agglomeration.- History :...

and Santa Margherita

Santa Margherita Ligure

thumb|250px|Villa Durazzo.Santa Margherita Ligure is a comune in the province of Genoa in the Italian region Liguria, located about 35 km southeast of Genoa, in the Tigullio traditional area.left|220px|thumb|16th century castle....

. From 1950 to 1957, Aquila also operated a service from Southampton

Southampton

Southampton is the largest city in the county of Hampshire on the south coast of England, and is situated south-west of London and north-west of Portsmouth. Southampton is a major port and the closest city to the New Forest...

to Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

and Glasgow

Glasgow

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

. The flying boats of Aquila Airways were also chartered for one-off trips, usually to deploy troops where scheduled services did not exist or where there were political considerations. The longest charter, in 1952, was from Southampton to the Falkland Islands

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands are an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean, located about from the coast of mainland South America. The archipelago consists of East Falkland, West Falkland and 776 lesser islands. The capital, Stanley, is on East Falkland...

. In 1953 the flying boats were chartered for troop deployment trips to Freetown

Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone, a country in West Africa. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean located in the Western Area of the country, and had a city proper population of 772,873 at the 2004 census. The city is the economic, financial, and cultural center of...

and Lagos

Lagos

Lagos is a port and the most populous conurbation in Nigeria. With a population of 7,937,932, it is currently the third most populous city in Africa after Cairo and Kinshasa, and currently estimated to be the second fastest growing city in Africa...

and there was a special trip from Hull

Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull , usually referred to as Hull, is a city and unitary authority area in the ceremonial county of the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It stands on the River Hull at its junction with the Humber estuary, 25 miles inland from the North Sea. Hull has a resident population of...

to Helsinki

Helsinki

Helsinki is the capital and largest city in Finland. It is in the region of Uusimaa, located in southern Finland, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, an arm of the Baltic Sea. The population of the city of Helsinki is , making it by far the most populous municipality in Finland. Helsinki is...

to relocate a ship's crew. The airline ceased operations on 30 September 1958.

Saunders-Roe Princess

-See also:-Bibliography:* Bridgman, Leonard. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1952-53. London: Jane's, 1953.* . Flight, 6 July 1951. pp. 10–11.* Flight, 16 March 1950, pp. 344–345....

first flew in 1952 and later received a certificate of airworthiness. Despite being the pinnacle of flying boat development none were sold, though Aquila Airways

Aquila Airways

Aquila Airways was a Southampton, Hampshire based British independentindependent from government-owned corporations airline, formed on 18 May 1948.-Early operations:...

reportedly attempted to buy them. Of the three Princesses

Saunders-Roe Princess

-See also:-Bibliography:* Bridgman, Leonard. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1952-53. London: Jane's, 1953.* . Flight, 6 July 1951. pp. 10–11.* Flight, 16 March 1950, pp. 344–345....

that were built, two never flew, and all were scrapped in 1967. In the late 1940s Saunders-Roe also produced the jet-powered SR.A/1

Saunders-Roe SR.A/1

|-See also:-References:*London, Peter. British Flying Boats. Stroud, UK:Sutton Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-7509-2695-3.*Mason, Francis K.The British Fighter since 1912. Annapolis, Maryland, USA:Naval Institute Press, 1992. ISBN 1-55750-082-7....

flying boat fighter, which did not progress beyond flying prototypes.

Helicopter

Helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by one or more engine-driven rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forwards, backwards, and laterally...

s ultimately took over the air-sea rescue role.

The land-based P-3 Orion

P-3 Orion

The Lockheed P-3 Orion is a four-engine turboprop anti-submarine and maritime surveillance aircraft developed for the United States Navy and introduced in the 1960s. Lockheed based it on the L-188 Electra commercial airliner. The aircraft is easily recognizable by its distinctive tail stinger or...

and carrier

Aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship designed with a primary mission of deploying and recovering aircraft, acting as a seagoing airbase. Aircraft carriers thus allow a naval force to project air power worldwide without having to depend on local bases for staging aircraft operations...

-based S-3 Viking

S-3 Viking

The Lockheed S-3 Viking is a four-seat twin-engine jet aircraft that was used by the U.S. Navy to identify, track, and destroy enemy submarines. In the late 1990s, the S-3B's mission focus shifted to surface warfare and aerial refueling. The Viking also provided electronic warfare and surface...

became the U.S. Navy's fixed-wing anti-submarine patrol aircraft.

Ansett Australia

Ansett Australia

Ansett Australia, Ansett, Ansett Airlines of Australia, or ANSETT-ANA as it was commonly known in earlier years, was a major Australian airline group, based in Melbourne. The airlines flew domestically within Australia and to destinations in Asia during its operation in 1996...

operated a flying boat service from Rose Bay to Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, directly east of mainland Port Macquarie, and about from Norfolk Island. The island is about 11 km long and between 2.8 km and 0.6 km wide with an area of...

until 1974, using Short Sandringham

Short Sandringham

- External links :* -See also:-References:NotesBibliography* Jackson, A.J British Civil Aircraft since 1919 - Volume Three. London: Putnam & Company Ltd, 1974. ISBN 0-370-10014-X....

s.

Modern versions

The shape of the Short Empire was a harbinger of the shape of later aircraft yet to come, and the type also contributed much to the designs of later ekranoplans. However, true flying boats have largely been replaced by seaplanes with floats and amphibian aircraft with wheels. The Beriev Be-200Beriev Be-200

The Beriev Be-200 Altair is a multipurpose amphibious aircraft designed by the Beriev Aircraft Company and manufactured by Irkut. Marketed as being designed for fire fighting, search and rescue, maritime patrol, cargo, and passenger transportation, it has a capacity of 12 tonnes of water, or up...

twin-jet amphibious aircraft has been one of the closest "living" descendants of the earlier flying boats, along with the larger amphibious planes used for fighting forest fires. There are also several experimental/kit amphibians such as the Volmer Sportsman, Quikkit Glass Goose

Quikkit Glass Goose

The Quikkit Glass Goose is a two-seat biplane amphibious aircraft marketed for homebuilding. It was designed by Garry LeGare in 1982 and sold through his firm Aero Gare as the Sea Hawk and, later, Sea Hawker...

, Airmax Sea Max

Airmax Sea Max

-External links:http://seamaxusa.com Website with specifications and photographs...

, Aeroprakt A-24, and Seawind 300C

Seawind 300C

The Seawinds are a family of composite, four-seat, amphibian airplanes that all feature a single tail-mounted engine.The Seawind line consists of the kit-built Seawind 2000 and Seawind 3000 that were marketed by SNA Inc. of Kimberton, Pennsylvania, USA and the Seawind 300C that was developed by...

.

The ShinMaywa US-2 (Japanese: 新明和 US-2) is a large STOL amphibious aircraft designed for air-sea rescue work. The US-2 is operated by the Japan Maritime Self Defense Force.

The Canadair CL-215

Canadair CL-215

The Canadair CL-215 was the first model in a series of firefighting flying boat amphibious aircraft built by Canadair and later Bombardier. The CL-215 is a twin-engine, high-wing aircraft designed to operate well at low speed and in gust-loading circumstances, as are found over forest fires...

and successor Bombardier 415 are examples of modern flying boats and are used for forest fire suppression.

Dornier announced plans in May 2010 to build CD2 SeaStar composite flying boats in Quebec, Canada.

The Iran

Iran

Iran , officially the Islamic Republic of Iran , is a country in Southern and Western Asia. The name "Iran" has been in use natively since the Sassanian era and came into use internationally in 1935, before which the country was known to the Western world as Persia...

ian military unveiled a squadron of flying boats, named Bavar 2, equipped with machine guns in September 2010.

External links

- When Boats Had Wings, June 1963 detail article Popular SciencePopular SciencePopular Science is an American monthly magazine founded in 1872 carrying articles for the general reader on science and technology subjects. Popular Science has won over 58 awards, including the ASME awards for its journalistic excellence in both 2003 and 2004...

- Flying boat newsreels at British Pathe

- The Flying Boat Web Site

- Flying Boats of the World - A Complete Reference

- Sunderland Flying Boats Windermere

- Flying Clippers Pan American's Fabulous Flying Ships

- The Boeing B-314

- Pan Am Clipper Airliners

- Foynes Flying Boat Museum

- The Dornier Do X

- Russian WWI and Civilian War Flying Boats

- Cyril Porte and Glenn H.Curtiss

- Centaur Seaplane (present day)

- Martin Mars (present day)

- SeaMax USA (present day)