William Mulloy

Encyclopedia

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

anthropologist. While his early research established him as a formidable scholar and skillful fieldwork supervisor in the province of North American Plains archaeology

Plains Indians

The Plains Indians are the Indigenous peoples who live on the plains and rolling hills of the Great Plains of North America. Their colorful equestrian culture and resistance to White domination have made the Plains Indians an archetype in literature and art for American Indians everywhere.Plains...

, he is best known for his studies of Polynesia

Polynesia

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of over 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are termed Polynesians and they share many similar traits including language, culture and beliefs...

n prehistory

Prehistory

Prehistory is the span of time before recorded history. Prehistory can refer to the period of human existence before the availability of those written records with which recorded history begins. More broadly, it refers to all the time preceding human existence and the invention of writing...

, especially his investigations into the production, transportation and erection of the monumental statuary

Monument

A monument is a type of structure either explicitly created to commemorate a person or important event or which has become important to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, or simply as an example of historic architecture...

on Rapa Nui (Easter Island

Easter Island

Easter Island is a Polynesian island in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian triangle. A special territory of Chile that was annexed in 1888, Easter Island is famous for its 887 extant monumental statues, called moai, created by the early Rapanui people...

) known as moai

Moai

Moai , or mo‘ai, are monolithic human figures carved from rock on the Chilean Polynesian island of Easter Island between the years 1250 and 1500. Nearly half are still at Rano Raraku, the main moai quarry, but hundreds were transported from there and set on stone platforms called ahu around the...

.

Early life and education

Mulloy was born May 3, 1917 in Salt Lake City, the only son of William Thomas Mulloy, Sr., a conductor on the Union Pacific RailroadUnion Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , headquartered in Omaha, Nebraska, is the largest railroad network in the United States. James R. Young is president, CEO and Chairman....

, and Barbara Seinsoth Mulloy. His older sister, Mary Grace Mulloy Strauch, recognized and encouraged his early interest in archaeology. On the occasions of his childhood visits to her home in Mesa

Mesa

A mesa or table mountain is an elevated area of land with a flat top and sides that are usually steep cliffs. It takes its name from its characteristic table-top shape....

, Arizona

Arizona

Arizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

, she would drive him to the town dump where he spent days at a time conducting his own stratification studies and enthusiastically reporting his results to her family at suppertime.

Mulloy earned a BA

Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts , from the Latin artium baccalaureus, is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate course or program in either the liberal arts, the sciences, or both...

in anthropology

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

from the University of Utah

University of Utah

The University of Utah, also known as the U or the U of U, is a public, coeducational research university in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States. The university was established in 1850 as the University of Deseret by the General Assembly of the provisional State of Deseret, making it Utah's oldest...

, where he had distinguished himself both in the classroom and on the wrestling team. From 1938 to 1939, he worked for the Louisiana

Louisiana

Louisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

State Archaeological Survey as a field archaeologist. In the Louisiana bayou

Bayou

A bayou is an American term for a body of water typically found in flat, low-lying areas, and can refer either to an extremely slow-moving stream or river , or to a marshy lake or wetland. The name "bayou" can also refer to creeks that see level changes due to tides and hold brackish water which...

, he contracted malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

. From Louisiana, Mulloy went to Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

where he began graduate studies at the University of Chicago

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It was founded by the American Baptist Education Society with a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and incorporated in 1890...

, then one of the world's foremost graduate schools of Anthropology and Archaeology. In the summer of 1940, Mulloy supervised archaeological fieldwork at Pueblo Bonito

Pueblo Bonito

Pueblo Bonito, the largest and best known Great House in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, northern New Mexico, was built by ancestral Pueblo people and occupied between AD 828 and 1126....

in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

. There, among the field crew, he met his future wife, Emily Ross, an archaeology major at the University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico

The University of New Mexico at Albuquerque is a public research university located in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the United States. It is the state's flagship research institution...

.

His graduate studies were interrupted when, shortly after the Attack on Pearl Harbor

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

, Mulloy enlisted in the US Army. At Camp Roberts, California

Camp Roberts, California

Camp Roberts is a California National Guard post in central California, located on both sides of the Salinas River in Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties, now run by the California Army National Guard. It is named after Harold W. Roberts, a World War I Medal of Honor recipient...

, he served first in the Field Artillery Instrument and Survey School

Field artillery

Field artillery is a category of mobile artillery used to support armies in the field. These weapons are specialized for mobility, tactical proficiency, long range, short range and extremely long range target engagement....

. Recognizing his talent and intelligence, the Army sent him to Officer Candidate School

Officer Candidate School

Officer Candidate School or Officer Cadet School are institutions which train civilians and enlisted personnel in order for them to gain a commission as officers in the armed forces of a country....

in North Dakota

North Dakota

North Dakota is a state located in the Midwestern region of the United States of America, along the Canadian border. The state is bordered by Canada to the north, Minnesota to the east, South Dakota to the south and Montana to the west. North Dakota is the 19th-largest state by area in the U.S....

. In 1943, Mulloy received his commission in the Counter Intelligence Corps

Counter Intelligence Corps

The Counter Intelligence Corps was a World War II and early Cold War intelligence agency within the United States Army. Its role was taken over by the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps in 1961 and, in 1967, by the U.S. Army Intelligence Agency...

. An outstanding linguist, Mulloy first learned Japanese and then became a Japanese language

Japanese language

is a language spoken by over 130 million people in Japan and in Japanese emigrant communities. It is a member of the Japonic language family, which has a number of proposed relationships with other languages, none of which has gained wide acceptance among historical linguists .Japanese is an...

instructor in order to prepare US military officers for the invasion and occupation of Japan. As a reserve officer, Mulloy advanced to the rank of major

Major

Major is a rank of commissioned officer, with corresponding ranks existing in almost every military in the world.When used unhyphenated, in conjunction with no other indicator of rank, the term refers to the rank just senior to that of an Army captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

.

After World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

ended, Mulloy returned to graduate studies in Chicago with his wife, Emily, and their infant daughter Kathy, who was born in 1945. As a graduate student, he worked in the steel mills, in the railroad yards and as janitor in an apartment building in South Chicago. After earning an MA

Master of Arts (postgraduate)

A Master of Arts from the Latin Magister Artium, is a type of Master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The M.A. is usually contrasted with the M.S. or M.Sc. degrees...

from the University of Chicago in 1948, Mulloy accepted a teaching position in what was then the Department of Anthropology

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

, Sociology

Sociology

Sociology is the study of society. It is a social science—a term with which it is sometimes synonymous—which uses various methods of empirical investigation and critical analysis to develop a body of knowledge about human social activity...

and Economics

Economics

Economics is the social science that analyzes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. The term economics comes from the Ancient Greek from + , hence "rules of the house"...

at the University of Wyoming

University of Wyoming

The University of Wyoming is a land-grant university located in Laramie, Wyoming, situated on Wyoming's high Laramie Plains, at an elevation of 7,200 feet , between the Laramie and Snowy Range mountains. It is known as UW to people close to the university...

and moved his family to Laramie

Laramie, Wyoming

Laramie is a city in and the county seat of Albany County, Wyoming, United States. The population was 30,816 at the . Located on the Laramie River in southeastern Wyoming, the city is west of Cheyenne, at the junction of Interstate 80 and U.S. Route 287....

, where both his son, Patrick, and his second daughter, Brigid, were born.

Five years after joining the faculty in Wyoming, Mulloy returned to Chicago and successfully defended his doctoral dissertation, A Preliminary Historical Outline for the Northwest Plains, still a standard work in the field of North American Plains Indian society. The University of Chicago

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It was founded by the American Baptist Education Society with a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and incorporated in 1890...

granted him a PhD

PHD

PHD may refer to:*Ph.D., a doctorate of philosophy*Ph.D. , a 1980s British group*PHD finger, a protein sequence*PHD Mountain Software, an outdoor clothing and equipment company*PhD Docbook renderer, an XML renderer...

in 1953.

University of Wyoming

Even as a junior faculty member of the University of WyomingUniversity of Wyoming

The University of Wyoming is a land-grant university located in Laramie, Wyoming, situated on Wyoming's high Laramie Plains, at an elevation of 7,200 feet , between the Laramie and Snowy Range mountains. It is known as UW to people close to the university...

, Mulloy distinguished himself as a teacher. George Carr Frison

George Carr Frison

George Carr Frison is an internationally-recognized archaeologist and recipient of many prestigious awards including: American Archaeology Lifetime Achievement Award, Paleoarchaeologist of the Century Award, and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences...

, now an emeritus

Emeritus

Emeritus is a post-positive adjective that is used to designate a retired professor, bishop, or other professional or as a title. The female equivalent emerita is also sometimes used.-History:...

Professor

Professor

A professor is a scholarly teacher; the precise meaning of the term varies by country. Literally, professor derives from Latin as a "person who professes" being usually an expert in arts or sciences; a teacher of high rank...

of Anthropology

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

, recalls that when he came to UW

University of Wyoming

The University of Wyoming is a land-grant university located in Laramie, Wyoming, situated on Wyoming's high Laramie Plains, at an elevation of 7,200 feet , between the Laramie and Snowy Range mountains. It is known as UW to people close to the university...

in 1962 as a 37-year-old freshman, except for an occasional visiting lecturer, Mulloy taught all of the courses offered by the university in anthropology.

Alan K. Simpson

Alan Kooi Simpson is an American politician who served from 1979 to 1997 as a United States Senator from Wyoming as a member of the Republican Party. His father, Milward L. Simpson, was also a member of the U.S...

; Charles Love, a geologist

Geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth as well as the processes and history that has shaped it. Geologists usually engage in studying geology. Geologists, studying more of an applied science than a theoretical one, must approach Geology using...

on the faculty of Western Wyoming College

Rock Springs, Wyoming

Rock Springs is a city in Sweetwater County, Wyoming, United States. The population was 18,708 at the 2000 census. Rock Springs is the principal city of the Rock Springs micropolitan statistical area, which has a population of 37,975....

and a researcher in Rapa Nui Geology

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

and Archaeology

Archaeology

Archaeology, or archeology , is the study of human society, primarily through the recovery and analysis of the material culture and environmental data that they have left behind, which includes artifacts, architecture, biofacts and cultural landscapes...

; Dr. Dennis J. Stanford, Chair of the Department of Anthropology of the National Museum of Natural History

National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. Admission is free and the museum is open 364 days a year....

at the Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

in Washington DC; and Sergio Rapu Haoa, former director of the anthropological museum on Rapa Nui and the island's first native governor.

During his three-decade academic career in Laramie

Laramie, Wyoming

Laramie is a city in and the county seat of Albany County, Wyoming, United States. The population was 30,816 at the . Located on the Laramie River in southeastern Wyoming, the city is west of Cheyenne, at the junction of Interstate 80 and U.S. Route 287....

, Mulloy perennially received the recognition of his students and faculty colleagues. His engaging classroom presence brought him such honors as the Omicron Delta Kappa

Omicron Delta Kappa

Omicron Delta Kappa, or ΟΔΚ, also known as The Circle, or more commonly ODK, is a national leadership honor society. It was founded December 3, 1914, at Washington & Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, by 15 student and faculty leaders. Chapters, known as Circles, are located on over 300...

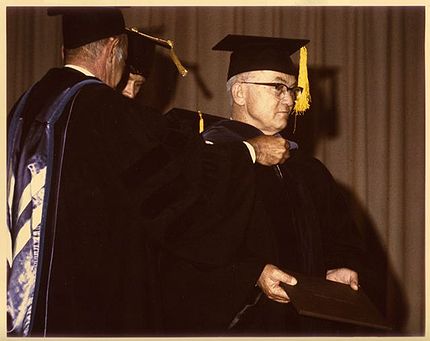

Award for outstanding teaching. The Wyoming Archaeological Society established the William Mulloy Scholarship in his honor in 1960. In 1964, he was the recipient of the George Duke Humphrey Distinguished Faculty Award. In 1976, the University of Wyoming awarded him its highest distinction, the LLD degree, honoris causa

Honorary degree

An honorary degree or a degree honoris causa is an academic degree for which a university has waived the usual requirements, such as matriculation, residence, study, and the passing of examinations...

.

In 1968, Mulloy established the Wyoming Anthropological Museum and served as its curator until his death. His personal collection of modern Rapa Nui folk art now forms part of the University of Wyoming Art Museum.

Plains Archaeology

Mulloy undertook extensive research projects in North American Plains IndianPlains Indians

The Plains Indians are the Indigenous peoples who live on the plains and rolling hills of the Great Plains of North America. Their colorful equestrian culture and resistance to White domination have made the Plains Indians an archetype in literature and art for American Indians everywhere.Plains...

and Southwestern Indian

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

archaeology. He investigated sites in New Mexico

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

, Wyoming

Wyoming

Wyoming is a state in the mountain region of the Western United States. The western two thirds of the state is covered mostly with the mountain ranges and rangelands in the foothills of the Eastern Rocky Mountains, while the eastern third of the state is high elevation prairie known as the High...

, and Montana

Montana

Montana is a state in the Western United States. The western third of Montana contains numerous mountain ranges. Smaller, "island ranges" are found in the central third of the state, for a total of 77 named ranges of the Rocky Mountains. This geographical fact is reflected in the state's name,...

. His monographs on the Hagen Site

Hagen Site

Hagen Site is an archaeological site that explores evidence on life in a Crow Indian community after the Crow tribe had split off from the Hidatsu.It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1964....

in Glendive, Montana

Glendive, Montana

Glendive is a city in and the county seat of Dawson County, Montana, United States. The population was 4,935 at the 2010 census.The town of Glendive is located in South Eastern Montana and is considered by many as an agricultural hub of Eastern Montana...

and the McKean Site

McKean Site

The McKean Site is an archaeological site in Crook County, Wyoming, United States. A premier site of the Great Plains hunting cultures, it is the namesake of the "McKean Complex." Two significant contemporary sites of the same culture are Signal Butte in Nebraska and the LoDaisKa Site in...

in Crook County, Wyoming are still widely consulted.

Early in his career, Mulloy analyzed and interpreted the data collected at a prehistoric campsite near Red Lodge, Montana

Red Lodge, Montana

Red Lodge is a city in and the county seat of Carbon County, Montana, United States. It is part of the Billings, Montana Metropolitan Statistical Area...

by parties from the Montana Archaeological Survey during their field work in 1937 and 1938.

From 1951 through 1954, Mulloy supervised the investigation of an 8000 year-old bison-kill site near Laramie. Named for James Allen of Cody, Wyoming, who brought the location to Mulloy’s attention in 1949, the site yielded a class of long, parallel-sided, unstemmed, concave-based projectile points used by paleo-Indians to hunt Bison occidentalis

Bison occidentalis

Bison occidentalis is an extinct species of bison that lived in North America during the Pleistocene. It probably evolved from Bison priscus. B. occidentalis was smaller and smaller horned than the steppe bison. Unlike any bison before it, its horns pointed upward, parallel to the plane of its face...

during the Pleistocene

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene is the epoch from 2,588,000 to 11,700 years BP that spans the world's recent period of repeated glaciations. The name pleistocene is derived from the Greek and ....

era. Mulloy designated the extraordinarily skillful example of oblique parallel flaking an Allen point.

In 1955, Mulloy and Dr. H. Marie Wormington, then Director of the Colorado Museum of Natural History

Denver Museum of Nature and Science

The Denver Museum of Nature & Science is a municipal natural history and science museum in Denver, Colorado. It is a resource for informal science education in the Rocky Mountain region. A variety of exhibitions, programs, and activities help museum visitors learn about the natural history of...

and long acknowledged doyenne of North American Plains Archaeology, served as co-directors of archaeological survey work in Alberta, Canada conducted under the auspices of the Glenbow Museum Foundation

Glenbow Museum

The Glenbow Museum in Calgary is one of Western Canada's largest museums, with over 93,000 square feet of exhibition space in more than 20 galleries, showcasing a selection of the Glenbow's collection of over a million objects....

.

Rapa Nui Archaeology

Kon-Tiki

Kon-Tiki was the raft used by Norwegian explorer and writer Thor Heyerdahl in his 1947 expedition across the Pacific Ocean from South America to the Polynesian islands. It was named after the Inca sun god, Viracocha, for whom "Kon-Tiki" was said to be an old name...

Expedition (1947), the Norwegian

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

explorer Thor Heyerdahl

Thor Heyerdahl

Thor Heyerdahl was a Norwegian ethnographer and adventurer with a background in zoology and geography. He became notable for his Kon-Tiki expedition, in which he sailed by raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands...

assembled a team of specialists to conduct archaeological research at various sites throughout Eastern Polynesia

Polynesia

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of over 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are termed Polynesians and they share many similar traits including language, culture and beliefs...

. Acting on the recommendation of Dr. H. Marie Wormington, Heyerdahl invited Mulloy to participate in the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition

Thor Heyerdahl

Thor Heyerdahl was a Norwegian ethnographer and adventurer with a background in zoology and geography. He became notable for his Kon-Tiki expedition, in which he sailed by raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands...

(1955–56). In Panama, Mulloy joined Arne Skjølsvold, of the University of Oslo

University of Oslo

The University of Oslo , formerly The Royal Frederick University , is the oldest and largest university in Norway, situated in the Norwegian capital of Oslo. The university was founded in 1811 and was modelled after the recently established University of Berlin...

, Carlyle S. Smith, of the University of Kansas

University of Kansas

The University of Kansas is a public research university and the largest university in the state of Kansas. KU campuses are located in Lawrence, Wichita, Overland Park, and Kansas City, Kansas with the main campus being located in Lawrence on Mount Oread, the highest point in Lawrence. The...

, Edwin N. Ferdon, Jr., of the Arizona State Museum at the University of Arizona

University of Arizona

The University of Arizona is a land-grant and space-grant public institution of higher education and research located in Tucson, Arizona, United States. The University of Arizona was the first university in the state of Arizona, founded in 1885...

, and Gonzalo Figueroa García-Huidobro of the University of Chile aboard the Christian Bjelland, a chartered Norwegian ship. Apart from Rapa Nui, the team of archaeologists visited Rapa Iti

Rapa Iti

Rapa or Rapa Iti as it is sometimes called in more recent years , is the largest and only inhabited island of the Bass Islands in French Polynesia. An older name for the island is Oparo Its area is 40 km2 with a population of almost 500 and a max elevation of 650 m...

, Tubuai, and Ra'ivavae

Raivavae

Raivavae is an island that is part of the Austral Islands in French Polynesia.It sustains a population of 905 people on of land. Its highest point is the top of a dead volcano which is 437 meters high.It was annexed by France in 1880....

in the Austral Islands

Austral Islands

The Austral Islands are the southernmost group of islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in the South Pacific. Geographically, they consist of two separate archipelagos, namely in the northwest the Tubuai Islands consisting of the Îles Maria, Rimatara, Rurutu, Tubuai...

, as well as Hiva 'Oa

Hiva Oa

Hiva Oa is the second largest island in the Marquesas Islands, in French Polynesia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. It is the largest island of the Southern Marquesas group. According to local religion, the gods created the islands as their home. Therefore all islands have...

and Nuku Hiva

Nuku Hiva

Nuku Hiva is the largest of the Marquesas Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. It was formerly also known as Île Marchand and Madison Island....

in the Marquesas Islands

Marquesas Islands

The Marquesas Islands enana and Te Fenua `Enata , both meaning "The Land of Men") are a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France in the southern Pacific Ocean. The Marquesas are located at 9° 00S, 139° 30W...

during their ten-month tour. Together with his colleagues, Mulloy began preliminary investigations of the fascinating and little-known archaeological sites of Rapa Nui. The international research staff that Heyerdahl brought together subsequently published the results of their investigations in Volume I of The Archaeology of Easter Island (1961).

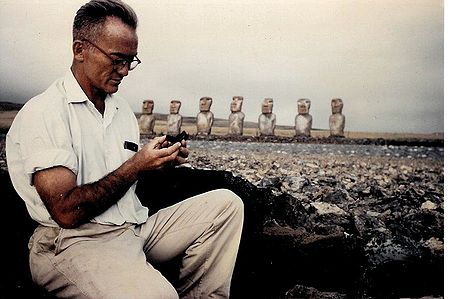

Shortly after his initial survey of Rapa Nui, Mulloy recognized the tremendously rich archaeological character of the island, its significance for understanding Oceanic prehistory and its potential to become an outstanding open-air museum of Polynesian culture. From 1955 to his untimely death in 1978, Mulloy would make more than twenty trips to Rapa Nui.

Upon his arrival on Rapa Nui in 1955, Mulloy met Father Sebastian Englert

Sebastian Englert

Father Sebastian Englert OFM Cap., was a Capuchin Franciscan friar, Roman Catholic priest, missionary, linguist and ethnologist from Germany....

, OFM Cap., a Roman Catholic priest

Priest

A priest is a person authorized to perform the sacred rites of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, rites of sacrifice to, and propitiation of, a deity or deities...

from Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

, for whose understanding of Rapa Nui culture and prehistory he developed the deepest respect. During the period of his missionary service on Rapa Nui, Father Sebastian compiled systematic field notes in the island's archaeology

Easter Island

Easter Island is a Polynesian island in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian triangle. A special territory of Chile that was annexed in 1888, Easter Island is famous for its 887 extant monumental statues, called moai, created by the early Rapanui people...

, ethnology

Ethnology

Ethnology is the branch of anthropology that compares and analyzes the origins, distribution, technology, religion, language, and social structure of the ethnic, racial, and/or national divisions of humanity.-Scientific discipline:Compared to ethnography, the study of single groups through direct...

and language, which he shared with Mulloy, who found them an important source of original research regarding all aspects of Rapa Nui culture. Mulloy later edited and translated a series of radio-broadcast lectures on Rapa Nui ethnology and prehistory that Padre Sebastián had originally prepared for Chilean naval personnel

Military of Chile

Chile's armed forces are subject to civilian control exercised by the president through the Minister of Defense. Military service of 12 to 24 months is mandatory for all male citizens upon turning 18. This conscription service can be postponed for educational or religious reasons...

stationed in Antarctica. With Mulloy's support, the Englert lectures were published in the United States under the title Island at the Center of the World.

Ahu Akivi

Ahu Akivi is an ahu with seven moai on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. The ahu and its moai were restored in 1960 by the American archaeologist William Mulloy and his Chilean colleague, Gonzalo Figueroa García-Huidobro...

and the physical restoration of Ahu Akivi

Ahu Akivi

Ahu Akivi is an ahu with seven moai on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. The ahu and its moai were restored in 1960 by the American archaeologist William Mulloy and his Chilean colleague, Gonzalo Figueroa García-Huidobro...

(1960); the investigation and restoration of Ahu Ko Te Riku

Ahu Tahai

The Tahai Ceremonial Complex is an archaeological site on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. Restored in 1974 by the late Dr. William Mulloy, an American archaeologist, Tahai comprises three principal ahu from north to south: Ko Te Riku , Tahai, and Vai Ure...

and Ahu Vai Uri

Ahu Tahai

The Tahai Ceremonial Complex is an archaeological site on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. Restored in 1974 by the late Dr. William Mulloy, an American archaeologist, Tahai comprises three principal ahu from north to south: Ko Te Riku , Tahai, and Vai Ure...

and the Tahai Ceremonial Complex

Ahu Tahai

The Tahai Ceremonial Complex is an archaeological site on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. Restored in 1974 by the late Dr. William Mulloy, an American archaeologist, Tahai comprises three principal ahu from north to south: Ko Te Riku , Tahai, and Vai Ure...

(1970); the investigation and restoration of two ahu at Hanga Kio'e (1972); the investigation and restoration of the ceremonial village at Orongo

Orongo

‘Orongo is a stone village and ceremonial centre at the southwestern tip of Rapa Nui . The first half of the ceremonial village's 53 stone masonry houses were investigated and restored in 1974 by American archaeologist William Mulloy...

(1974) and numerous other archaeological surveys throughout the island. In particular, Mulloy's restoration projects on the island earned him the great respect of Rapa Nui islanders, many of whom collaborated with him at multiple venues. Among his chief collaborators were Juan Edmunds Rapahango

Juan Edmunds Rapahango

Juan Edmunds Rapahango is a retired Rapa Nui politician, the former Mayor of Hanga Roa, the municipality of Rapa Nui , in Chilean Polynesia. He is the son of Henry Percy Edmunds, director of the Williamson-Balfour Company, and Victoria Rapahango, an important native respondent for early...

, Martín Rapu Pua and Germán Hotu Teave, whose daughter, Melania Carolina Hotu Hey

Melania Carolina Hotu Hey

Melania Carolina Hotu Hey served as the provincial governor of Easter Island , in Chilean Polynesia, from March 11, 2006 to March 18, 2010. She was appointed in 2006 by newly elected Chilean President Michelle Bachelet Jeria as part of the President's undertaking to increase female representation...

, is a former Provincial

Province

A province is a territorial unit, almost always an administrative division, within a country or state.-Etymology:The English word "province" is attested since about 1330 and derives from the 13th-century Old French "province," which itself comes from the Latin word "provincia," which referred to...

Governor

Governor

A governor is a governing official, usually the executive of a non-sovereign level of government, ranking under the head of state...

of Rapa Nui.

In 1978, in recognition of his distinguished and unselfish work on behalf of the Rapa Nui community

Rapanui

The Rapa Nui or Rapanui are the native Polynesian inhabitants of Easter Island, or Rapa Nui, in the Pacific Ocean. The easternmost Polynesian culture, the Rapa Nui people make up 60% of Easter Island's population, with some living also in mainland Chile...

, Mulloy was named Illustrious Citizen of Easter Island, by then mayor Juan Edmunds Rapahango

Juan Edmunds Rapahango

Juan Edmunds Rapahango is a retired Rapa Nui politician, the former Mayor of Hanga Roa, the municipality of Rapa Nui , in Chilean Polynesia. He is the son of Henry Percy Edmunds, director of the Williamson-Balfour Company, and Victoria Rapahango, an important native respondent for early...

. Earlier that year, the Chilean government had bestowed upon him their highest civilian honor, the Orden de Don Bernardo O'Higgins.

Legacy

Mulloy died of lung cancerLung cancer

Lung cancer is a disease characterized by uncontrolled cell growth in tissues of the lung. If left untreated, this growth can spread beyond the lung in a process called metastasis into nearby tissue and, eventually, into other parts of the body. Most cancers that start in lung, known as primary...

in Laramie

Laramie, Wyoming

Laramie is a city in and the county seat of Albany County, Wyoming, United States. The population was 30,816 at the . Located on the Laramie River in southeastern Wyoming, the city is west of Cheyenne, at the junction of Interstate 80 and U.S. Route 287....

on March 25, 1978. His remains were interred on Rapa Nui in full view of the Tahai Ceremonial Complex

Ahu Tahai

The Tahai Ceremonial Complex is an archaeological site on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. Restored in 1974 by the late Dr. William Mulloy, an American archaeologist, Tahai comprises three principal ahu from north to south: Ko Te Riku , Tahai, and Vai Ure...

, one of his more important restoration projects. His widow, Emily Ross Mulloy, his son Patrick, his daughter Brigid and his grandson Phineas Kelly were present. Colleagues and friends joined the Rapa Nui community in paying their respects to the scientist whose work had brought their island to the attention of the world.

The Mulloy restoration projects at Ahu Akivi

Ahu Akivi

Ahu Akivi is an ahu with seven moai on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. The ahu and its moai were restored in 1960 by the American archaeologist William Mulloy and his Chilean colleague, Gonzalo Figueroa García-Huidobro...

, the ceremonial village of Orongo

Orongo

‘Orongo is a stone village and ceremonial centre at the southwestern tip of Rapa Nui . The first half of the ceremonial village's 53 stone masonry houses were investigated and restored in 1974 by American archaeologist William Mulloy...

, Vinapu

Ahu Vinapu

Ahu Vinapu is an archaeological site on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia.The ceremonial center of Vinapu includes one of the larger ahu on Rapa Nui. The ahu exhibits extraordinary stonemasonry consisting of large, carefully fitted slabs of basalt...

, Ahu Ko Te Riku

Ahu Tahai

The Tahai Ceremonial Complex is an archaeological site on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. Restored in 1974 by the late Dr. William Mulloy, an American archaeologist, Tahai comprises three principal ahu from north to south: Ko Te Riku , Tahai, and Vai Ure...

, Ahu Vai Ure

Ahu Tahai

The Tahai Ceremonial Complex is an archaeological site on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. Restored in 1974 by the late Dr. William Mulloy, an American archaeologist, Tahai comprises three principal ahu from north to south: Ko Te Riku , Tahai, and Vai Ure...

and the rest of the ceremonial center at Tahai

Ahu Tahai

The Tahai Ceremonial Complex is an archaeological site on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. Restored in 1974 by the late Dr. William Mulloy, an American archaeologist, Tahai comprises three principal ahu from north to south: Ko Te Riku , Tahai, and Vai Ure...

now constitute an integral part of the Rapa Nui National Park

Rapa Nui National Park

Rapa Nui National Park is a World Heritage Site located on Easter Island, Chile. The park is divided into seven sections:*Rano Kau *Puna Pau ....

, designated by UNESCO

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations...

as a World Heritage site.

Following his death, in May 1978, the Trustees of the University of Wyoming

University of Wyoming

The University of Wyoming is a land-grant university located in Laramie, Wyoming, situated on Wyoming's high Laramie Plains, at an elevation of 7,200 feet , between the Laramie and Snowy Range mountains. It is known as UW to people close to the university...

named him Distinguished Professor of Anthropology

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

. In 1997, the Department of Anthropology at the University of Wyoming established the annual Mulloy Lecture Series in recognition of Mulloy's "four-field" approach, which integrated archaeology

Archaeology

Archaeology, or archeology , is the study of human society, primarily through the recovery and analysis of the material culture and environmental data that they have left behind, which includes artifacts, architecture, biofacts and cultural landscapes...

, biological anthropology

Biological anthropology

Biological anthropology is that branch of anthropology that studies the physical development of the human species. It plays an important part in paleoanthropology and in forensic anthropology...

, cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans, collecting data about the impact of global economic and political processes on local cultural realities. Anthropologists use a variety of methods, including participant observation,...

and linguistic anthropology

Linguistic anthropology

Linguistic anthropology is the interdisciplinary study of how language influences social life. It is a branch of anthropology that originated from the endeavor to document endangered languages, and has grown over the past 100 years to encompass almost any aspect of language structure and...

into a unified program at UW. In 2003, twenty-five years after his death, the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Wyoming named him to their roster of Outstanding Former Faculty.

Rapanui

The Rapa Nui or Rapanui are the native Polynesian inhabitants of Easter Island, or Rapa Nui, in the Pacific Ocean. The easternmost Polynesian culture, the Rapa Nui people make up 60% of Easter Island's population, with some living also in mainland Chile...

protegé, Sergio Rapu Haoa, completed a BA degree in anthropology at the University of Wyoming and went on to graduate studies at the University of Hawai'i

University of Hawaii

The University of Hawaii System, formally the University of Hawaii and popularly known as UH, is a public, co-educational college and university system that confers associate, bachelor, master, and doctoral degrees through three university campuses, seven community college campuses, an employment...

. Upon his return to the Rapa Nui, Rapu directed the island's archaeology museum and conducted his own research and restoration projects, notably at Ahu Nau Nau

Anakena

Anakena is a white coral sand beach in Rapa Nui National Park on Rapa Nui , a Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean. Anakena has two ahus, one with a single moai and the other with six...

in the Anakena

Anakena

Anakena is a white coral sand beach in Rapa Nui National Park on Rapa Nui , a Chilean island in the Pacific Ocean. Anakena has two ahus, one with a single moai and the other with six...

district of the island. Rapu would later become the island's first Rapa Nui governor.

Mulloy's personal library forms the core of a research collection now located on Rapa Nui at the Father Sebastian Englert Anthropological Museum

Father Sebastian Englert Anthropological Museum

The Father Sebastian Englert Anthropological Museum is a museum in the town of Hanga Roa on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. Named for the Bavarian missionary, Fr. Sebastian Englert, OFM Cap., the museum was founded in 1973 and is dedicated to the conservation of the Rapa Nui cultural patrimony...

. For many years, the William Mulloy Library

William Mulloy Library

The William Mulloy Library is a research library administered by the Father Sebastian Englert Anthropological Museum on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. Named for the late Dr...

had been maintained in Viña del Mar, Chile by the Easter Island Foundation

Easter Island Foundation

The Easter Island Foundation is an American non-profit organization that promotes the conservation and protection of the fragile cultural heritage of Rapa Nui and other Polynesian islands.-Background of the Foundation:...

, who supported it, added to its collection and planned its eventual transfer to the island.

Emily Ross Mulloy, who died in 2003 at her home at 'Ualapu'e

Molokai

Molokai or Molokai is an island in the Hawaiian archipelago. It is 38 by 10 miles in size with a land area of , making it the fifth largest of the main Hawaiian Islands and the 27th largest island in the United States. It lies east of Oahu across the 25-mile wide Kaiwi Channel and north of...

on Moloka'i

Molokai

Molokai or Molokai is an island in the Hawaiian archipelago. It is 38 by 10 miles in size with a land area of , making it the fifth largest of the main Hawaiian Islands and the 27th largest island in the United States. It lies east of Oahu across the 25-mile wide Kaiwi Channel and north of...

in Hawai'i

Hawaii

Hawaii is the newest of the 50 U.S. states , and is the only U.S. state made up entirely of islands. It is the northernmost island group in Polynesia, occupying most of an archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean, southwest of the continental United States, southeast of Japan, and northeast of...

, is now buried with her husband at Tahai

Ahu Tahai

The Tahai Ceremonial Complex is an archaeological site on Rapa Nui in Chilean Polynesia. Restored in 1974 by the late Dr. William Mulloy, an American archaeologist, Tahai comprises three principal ahu from north to south: Ko Te Riku , Tahai, and Vai Ure...

. The Mulloys have three children, Kathy, Patrick and Brigid; three grandchildren, Francisco Nahoe, Josefina Nahoe and Phineas Kelly; and two great-grandchildren, Rowan Kelly and Liam Kelly. Two of the Mulloy grandchildren, Francisco and Josefina, are ethnic Rapa Nui through their father, Guillermo Nahoe Pate.

Selected bibliography

- Mulloy, W.T. 1943 A Prehistoric Campsite Near Red Lodge, Montana. American Antiquity 9:170-179.

- Mulloy, W.T. 1953. A Preliminary Historical Outline for the Northwestern Plains. Chicago: Ill. University of Chicago.

- Mulloy, W.T. 1954. The Ash Coulee Site. American Antiquity 25:112-116.

- Mulloy, W.T. 1954. The McKean Site in Northeastern Wyoming. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 10:432-460.

- Mulloy, W.T. 1959. The Ceremonial Center of Vinapu. Actas del XXXIII Congreso Internacional de Americanistas. San José, Costa Rica.

- Mulloy, W.T. 1968. Preliminary Report of Archaeological Field Work, February-July, 1968, Easter Island. New York, N.Y.: Easter Island Committee, International Fund for Monuments.

- Mulloy, W.T. 1970. Preliminary Report of the Restoration of Ahu Vai Uri Easter Island. Bulletin of the International Fund for Monuments, No. 2.

- Mulloy, W.T. 1974. Contemplate the Navel of the World. Americas 26 (4): 25-33.

- Mulloy, W.T. 1975. Investigation and Restoration of the Ceremonial Center of Orongo, Easter Island. Bulletin of the International Fund for Monuments, No. 4.

- Mulloy, W.T., E.C. Olson, R. Snodgrasse, and H.H. Turney-High. 1976. The Hagen Site: A Prehistoric Village on the Lower Yellowstone. Lincoln, Neb.: J & L Reprint Co.

- Mulloy, W.T., and G. Figueroa. 1978. The A Kivi-Vai Teka Complex and its Relationship to Easter Island Architectural Prehistory. Honolulu: Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

- Mulloy, W.T., and S.R. Fischer. 1993. Easter Island Studies: Contributions to the History of Rapanui in Memory of William T. Mulloy. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Mulloy, W.T., World Monuments Fund, and Easter Island Foundation. 1995. The Easter Island Bulletins of William Mulloy. New York; Houston: World Monuments Fund; Easter Island Foundation.

- Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the East Pacific, T. Heyerdahl, E.N. Ferdon, W.T. Mulloy, A. Skjølsvold, C.S. Smith. 1961. Archaeology of Easter Island. Stockholm; Santa Fe, N.M.: Forum Pub. House; distributed by The School of American Research.

- Reiter, P., W.T. Mulloy, and E.H. Blumenthal. 1940. Preliminary Report of the Jemez Excavation at Nanishagi, New Mexico. Albuquerque, N.M., University of New Mexico Press.