Papal conclave, 1800

Encyclopedia

| Papal conclave, 1800 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Popes | ||||||||||||||||||

|

The Papal conclave of 1799–1800 followed the death of Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI , born Count Giovanni Angelo Braschi, was Pope from 1775 to 1799.-Early years:Braschi was born in Cesena...

on 29 August 1799 and led to the selection as pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

of Giorgio Barnaba Luigi Chiaramonti, who took the name Pius VII

Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII , born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti, was a monk, theologian and bishop, who reigned as Pope from 14 March 1800 to 20 August 1823.-Early life:...

, on 14 March 1800. This conclave, the last conclave

Papal conclave

A papal conclave is a meeting of the College of Cardinals convened to elect a Bishop of Rome, who then becomes the Pope during a period of vacancy in the papal office. The Pope is considered by Roman Catholics to be the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and earthly head of the Roman Catholic Church...

to take place outside Rome, was held in Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

. This period was marked by uncertainty for the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

following the invasion of the Papal States

Papal States

The Papal State, State of the Church, or Pontifical States were among the major historical states of Italy from roughly the 6th century until the Italian peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia .The Papal States comprised territories under...

and abduction of Pius VI under the French Directory

French Directory

The Directory was a body of five Directors that held executive power in France following the Convention and preceding the Consulate...

.

Pope Pius VI

Pius VI's reign had been marked by tension between his authority and that of the European monarchs and other institutions, both secular and ecclesiastical. This was largely due to his moderate liberal and reforming pretences. At the beginning of his pontificate he promised to continue the work of his predecessor, Pope Clement XIVPope Clement XIV

Pope Clement XIV , born Giovanni Vincenzo Antonio Ganganelli, was Pope from 1769 to 1774. At the time of his election, he was the only Franciscan friar in the College of Cardinals.-Early life:...

, in whose 1773 brief

Papal brief

The Papal Brief is a formal document emanating from the Pope, in a somewhat simpler and more modern form than a Papal Bull.-History:The introduction of briefs, which occurred at the beginning of the pontificate of Pope Eugenius IV , was clearly prompted for the same desire for greater simplicity...

Dominus ac Redemptor

Dominus ac Redemptor

Dominus ac Redemptor is the papal brief promulgated on 21 July 1773 by which Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Society of Jesus.-Circumstances:...

, the dissolution of the Jesuits

Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus is a Catholic male religious order that follows the teachings of the Catholic Church. The members are called Jesuits, and are also known colloquially as "God's Army" and as "The Company," these being references to founder Ignatius of Loyola's military background and a...

was announced. Pro-Jesuit powers remained in support of Pius, thinking him secretly more inclined to the Society than Clement. The Archduchy of Austria

Archduchy of Austria

The Archduchy of Austria , one of the most important states within the Holy Roman Empire, was the nucleus of the Habsburg Monarchy and the predecessor of the Austrian Empire...

proved a threat when its ruler, Emperor Joseph II

Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Joseph II was Holy Roman Emperor from 1765 to 1790 and ruler of the Habsburg lands from 1780 to 1790. He was the eldest son of Empress Maria Theresa and her husband, Francis I...

, made internal reforms which conflicted with some of the power of the Papacy. Further, German archbishop

Archbishop

An archbishop is a bishop of higher rank, but not of higher sacramental order above that of the three orders of deacon, priest , and bishop...

s had shown independence at the 1786 Congress of Ems

Congress of Ems

The Congress of Ems was a meeting set up by German and Austrian Catholic archbishops, and held in August 1786 in Bad Ems, near Koblenz. Its object was to protest against papal interference in the exercise of episcopal powers, and to fix the future relations between the participating bishops and the...

, but were soon brought into line.

At the outbreak of the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

Pius was compelled to see the independent Gallican Church

Gallican Church

The Gallican Church was the Catholic Church in France from the time of the Declaration of the Clergy of France to that of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy during the French Revolution....

suppressed, the pontifical and ecclesiastical possessions in France confiscated and an effigy of himself burnt by the populace at the Palais Royal

Palais Royal

The Palais-Royal, originally called the Palais-Cardinal, is a palace and an associated garden located in the 1st arrondissement of Paris...

. The murder of the republican agent Hugo Basseville in the streets of Rome (January 1793) gave new ground of offence; the papal court was charged with complicity by the French Convention, and Pius threw in his lot with the First Coalition

First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition was the first major effort of multiple European monarchies to contain Revolutionary France. France declared war on the Habsburg monarchy of Austria on 20 April 1792, and the Kingdom of Prussia joined the Austrian side a few weeks later.These powers initiated a series...

against the French First Republic

French First Republic

The French First Republic was founded on 22 September 1792, by the newly established National Convention. The First Republic lasted until the declaration of the First French Empire in 1804 under Napoleon I...

.

The State of the See

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

invaded the Italian Peninsula

Italian Peninsula

The Italian Peninsula or Apennine Peninsula is one of the three large peninsulas of Southern Europe , spanning from the Po Valley in the north to the central Mediterranean Sea in the south. The peninsula's shape gives it the nickname Lo Stivale...

, defeated the papal troops and occupied Ancona

Ancona

Ancona is a city and a seaport in the Marche region, in central Italy, with a population of 101,909 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region....

and Loreto

Loreto (AN)

Loreto is a hilltown and comune of the Italian province of Ancona, in the Marche. It is mostly famous as the seat of the Basilica della Santa Casa, a popular Catholic pilgrimage site.-Location:...

. He did not continue and conquer Rome, as the French Directory

French Directory

The Directory was a body of five Directors that held executive power in France following the Convention and preceding the Consulate...

ordered, being aware that this would not win favour among the French and Italian populations. Pius sued for peace, which was granted at Tolentino

Tolentino

Tolentino is a town and comune of about 20,000 inhabitants, in the province of Macerata in the Marche region of central Italy.It is located in the middle of the valley of the Chienti.-History:...

on February 19, 1797. The Treaty of Tolentino

Treaty of Tolentino

The Treaty of Tolentino was signed after nine months of negotiations between France and the Papal States on February 19, 1797. It was part of the events following the invasion of Italy in the early stages of the French Revolutionary Wars...

transferred Romagna

Romagna

Romagna is an Italian historical region that approximately corresponds to the south-eastern portion of present-day Emilia-Romagna. Traditionally, it is limited by the Apennines to the south-west, the Adriatic to the east, and the rivers Reno and Sillaro to the north and west...

to Bonaparte's newly formed Cispadane Republic

Cispadane Republic

The Cispadane Republic was a short-lived republic located in Northern Italy, founded in 1796 with the protection of the French army, led by Napoleon Bonaparte. In the following year, it was merged into the Cisalpine Republic....

(founded in December 1796 out of a merger of Reggio

Reggio Emilia

Reggio Emilia is an affluent city in northern Italy, in the Emilia-Romagna region. It has about 170,000 inhabitants and is the main comune of the Province of Reggio Emilia....

, Modena

Modena

Modena is a city and comune on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy....

, Bologna

Bologna

Bologna is the capital city of Emilia-Romagna, in the Po Valley of Northern Italy. The city lies between the Po River and the Apennine Mountains, more specifically, between the Reno River and the Savena River. Bologna is a lively and cosmopolitan Italian college city, with spectacular history,...

and Ferrara

Ferrara

Ferrara is a city and comune in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital city of the Province of Ferrara. It is situated 50 km north-northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream of the Po River, located 5 km north...

) in a hope that the French would not further pursue the Papal lands. Several reforms were made in the French-controlled regions, where much property of the Church was confiscated.

Several factors led to the complete occupation of Rome by the French. Firstly, the entrance of the Russian army into Northern Italy

Northern Italy

Northern Italy is a wide cultural, historical and geographical definition, without any administrative usage, used to indicate the northern part of the Italian state, also referred as Settentrione or Alta Italia...

pushed the French back. Secondly, on December 28, 1797, in a riot created by some Italian and French revolutionists, the French general Mathurin-Léonard Duphot of the French embassy was killed and a new pretext furnished for invasion.

Louis Alexandre Berthier

Louis Alexandre Berthier

Louis Alexandre Berthier, 1st Prince de Wagram, 1st Duc de Valangin, 1st Sovereign Prince de Neuchâtel , was a Marshal of France, Vice-Constable of France beginning in 1808, and Chief of Staff under Napoleon.-Early life:Alexandre was born at Versailles to Lieutenant-Colonel Jean Baptiste Berthier ,...

marched to Rome, entered it unopposed on February 13, 1798, and, proclaiming a Roman Republic

Roman Republic (18th century)

The Roman Republic was proclaimed on February 15, 1798 after Louis Alexandre Berthier, a general of Napoleon, had invaded the city of Rome on February 10....

, demanded of the pope the renunciation of his temporal authority. Upon his refusal he was taken prisoner, and on February 20 was escorted from the Vatican

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

to Siena

Siena

Siena is a city in Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the province of Siena.The historic centre of Siena has been declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Site. It is one of the nation's most visited tourist attractions, with over 163,000 international arrivals in 2008...

, and thence to the Certosa near Florence. The French declaration of war against Ferdinand III, Grand Duke of Tuscany

Ferdinand III, Grand Duke of Tuscany

Ferdinand III, Grand Duke of Tuscany was Grand Duke of Tuscany from 1790 to 1801 and, after a period of disenfranchisement, again from 1814 to 1824. He was also the Prince-elector and Grand Duke of Salzburg and Grand Duke of Würzburg .-Biography:Ferdinand was born in Florence, Tuscany, into the...

led to Pius' removal, though by this time deathly ill, by way of Parma

Parma

Parma is a city in the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna famous for its ham, its cheese, its architecture and the fine countryside around it. This is the home of the University of Parma, one of the oldest universities in the world....

, Piacenza

Piacenza

Piacenza is a city and comune in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Piacenza...

, Turin

Turin

Turin is a city and major business and cultural centre in northern Italy, capital of the Piedmont region, located mainly on the left bank of the Po River and surrounded by the Alpine arch. The population of the city proper is 909,193 while the population of the urban area is estimated by Eurostat...

and Grenoble

Grenoble

Grenoble is a city in southeastern France, at the foot of the French Alps where the river Drac joins the Isère. Located in the Rhône-Alpes region, Grenoble is the capital of the department of Isère...

to the citadel of Valence

Valence, Drôme

Valence is a commune in southeastern France, the capital of the Drôme department, situated on the left bank of the Rhône, south of Lyon on the railway to Marseilles.Its inhabitants are called Valentinois...

, where he died six weeks later, on August 29, 1799.

The Conclave

With the loss of the Vatican and the pope's other temporal power, the cardinals were left in a remarkable position. They were forced to hold the conclave in VeniceVenice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

, making the conclave the last to be held outside Rome. This followed an ordinance

Ecclesiastical ordinances

Ecclesiastical ordinances are the bylaws of a Christian religious organization, especially that of a diocese or province of a church. They are used in the Anglican Communion, particularly the American Episcopal Church and Roman Catholic Church....

issued by Pius VI in 1798, in which was stated that the conclave, in such a situation, would be held in the city with the greatest number of Cardinals

Cardinal (Catholicism)

A cardinal is a senior ecclesiastical official, usually an ordained bishop, and ecclesiastical prince of the Catholic Church. They are collectively known as the College of Cardinals, which as a body elects a new pope. The duties of the cardinals include attending the meetings of the College and...

among the population. The Benedictine

Benedictine

Benedictine refers to the spirituality and consecrated life in accordance with the Rule of St Benedict, written by Benedict of Nursia in the sixth century for the cenobitic communities he founded in central Italy. The most notable of these is Monte Cassino, the first monastery founded by Benedict...

San Giorgio Monastery

San Giorgio Monastery

The San Giorgio Monastery was a Benedictine monastery in Venice, Italy, located on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. It stands next to the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore, which formerly served the monastic community, and currently serves as the headquarters of the Cini Foundation.-Foundation:The...

, Venice, was the chosen location of the conclave. The city, along with other northern Italian lands, was at the time held by the Archduchy of Austria

Archduchy of Austria

The Archduchy of Austria , one of the most important states within the Holy Roman Empire, was the nucleus of the Habsburg Monarchy and the predecessor of the Austrian Empire...

, whose ruler Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor

Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor

Francis II was the last Holy Roman Emperor, ruling from 1792 until 6 August 1806, when he dissolved the Empire after the disastrous defeat of the Third Coalition by Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz...

agreed to foot the costs of the conclave.

Stalemate

Stalemate is a situation in chess where the player whose turn it is to move is not in check but has no legal moves. A stalemate ends the game in a draw. Stalemate is covered in the rules of chess....

between three candidates until March 1800. Thirty-four Cardinals were present at the start, with the late arrival of Cardinal Franziskus Herzan von Harras who was also the imperial commissioner and used the imperial veto of Francis II twice. Ercole Consalvi was almost unanimously voted as secretary of the conclave; he would prove an influential figure in the election of the new pope. Carlo Bellisomi seemed the sure winner, with wide support from the Cardinals, but his unpopularity among the Austrian Cardinals, who preferred Mattei, subjected him to the veto. The conclave added a third possible candidate in Cardinal Hyacinthe Sigismond Gerdil

Hyacinthe Sigismond Gerdil

Hyacinthe Sigismond Gerdil was an Italian theologian and Cardinal.Gerdil was born at Samoëns in Savoie. When fifteen years old, he joined the Barnabites at Annecy, and was sent to Bologna to pursue his theological studies; there he devoted his mind to the various branches of knowledge with great...

CRSP

Barnabites

The Barnabites, or Clerics Regular of Saint Paul is a Roman Catholic order.-Establishment of the Order :It was founded in 1530 by three Italian noblemen: St. Anthony Mary Zaccaria The Barnabites, or Clerics Regular of Saint Paul (Latin: Clerici Regulares Sancti Pauli, abbr. B.) is a Roman Catholic...

but was also vetoed by Austria. As the conclave was in the third month Cardinal Maury, a neutral, suggested Chiaramonti who, with the support of the powerful Conclave secretary, was elected.

Barnaba Luigi Count Chiaramonti was, at the time, the bishop of Imola

Imola

thumb|250px|The Cathedral of Imola.Imola is a town and comune in the province of Bologna, located on the Santerno river, in the Emilia-Romagna region of north-central Italy...

in the Subalpine Republic

Subalpine Republic

The Subalpine Republic was a short-lived republic established in 1800 on the territory of Piedmont during its militar rule by Napoleonic France....

. He had stayed in place after the assumption of his diocese

Diocese

A diocese is the district or see under the supervision of a bishop. It is divided into parishes.An archdiocese is more significant than a diocese. An archdiocese is presided over by an archbishop whose see may have or had importance due to size or historical significance...

by Bonaparte's army in 1797 and famously made a speech in which he stated that good Christians could make good democrats, a speech described as "Jacobin

Jacobin (politics)

A Jacobin , in the context of the French Revolution, was a member of the Jacobin Club, a revolutionary far-left political movement. The Jacobin Club was the most famous political club of the French Revolution. So called from the Dominican convent where they originally met, in the Rue St. Jacques ,...

" by Bonaparte himself. Though he could not save ecclesiastical reform and confiscation under the new rule, he did prevent the church being dissolved, unlike that in France.

Due to its temporary siting in Venice, the Papal coronation

Papal Coronation

A papal coronation was the ceremony of the placing of the Papal Tiara on a newly elected pope. The first recorded papal coronation was that of Pope Celestine II in 1143. Soon after his coronation in 1963, Pope Paul VI abandoned the practice of wearing the tiara. His successors have chosen not to...

was hurried. Having no papal treasures on hand the noblewomen of the city manufactured the famous papier-mâché

Papier-mâché

Papier-mâché , alternatively, paper-mache, is a composite material consisting of paper pieces or pulp, sometimes reinforced with textiles, bound with an adhesive, such as glue, starch, or wallpaper paste....

papal tiara

Papal Tiara

The Papal Tiara, also known incorrectly as the Triple Tiara, or in Latin as the Triregnum, in Italian as the Triregno and as the Trirègne in French, is the three-tiered jewelled papal crown, supposedly of Byzantine and Persian origin, that is a prominent symbol of the papacy...

. It was adorned with their own jewels. Chiaramonti was declared Pope Pius VII and crowned on March 21 in a cramped monastery church.

A new pope

The new Pope headed for Rome, which he entered to the pleasure of the population on July 3. Fearing further invasion he decreed the Papal States

Papal States

The Papal State, State of the Church, or Pontifical States were among the major historical states of Italy from roughly the 6th century until the Italian peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia .The Papal States comprised territories under...

should remain neutral between Napoleonic Italy in the north and the Kingdom of Naples

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples, comprising the southern part of the Italian peninsula, was the remainder of the old Kingdom of Sicily after secession of the island of Sicily as a result of the Sicilian Vespers rebellion of 1282. Known to contemporaries as the Kingdom of Sicily, it is dubbed Kingdom of...

in the south. At the time the latter was ruled by Ferdinand III of Sicily/Ferdinand IV of Naples

Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies

Ferdinand I reigned variously over Naples, Sicily, and the Two Sicilies from 1759 until his death. He was the third son of King Charles III of Spain by his wife Maria Amalia of Saxony. On 10 August 1759, Charles succeeded his elder brother, Ferdinand VI, as King Charles III of Spain...

, a member of the House of Bourbon

House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon is a European royal house, a branch of the Capetian dynasty . Bourbon kings first ruled Navarre and France in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Bourbon dynasty also held thrones in Spain, Naples, Sicily, and Parma...

.

Ercole Consalvi, the secretary of the conclave, ascended to the College of Cardinals

College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church.A function of the college is to advise the pope about church matters when he summons them to an ordinary consistory. It also convenes on the death or abdication of a pope as a papal conclave to elect a successor...

and became the Secretary of the Papal State on 11 August. On July 15 France officially rerecognised Catholicism

Catholicism

Catholicism is a broad term for the body of the Catholic faith, its theologies and doctrines, its liturgical, ethical, spiritual, and behavioral characteristics, as well as a religious people as a whole....

as its majority (not state) religion in the Concordat of 1801

Concordat of 1801

The Concordat of 1801 was an agreement between Napoleon and Pope Pius VII, signed on 15 July 1801. It solidified the Roman Catholic Church as the majority church of France and brought back most of its civil status....

, and the Church was granted a measure of freedom with a Gallician constitution of the clergy. The Concordat further recognised the Papal States and that which it had confiscated and sold during the occupation of the area. In 1803 the reinstatement of the Papal States was made official by the Treaty of Lunéville

Treaty of Lunéville

The Treaty of Lunéville was signed on 9 February 1801 between the French Republic and the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, negotiating both on behalf of his own domains and of the Holy Roman Empire...

.

Napoleon pursued secularisation of smaller, independent lands and, through diplomatic pressure, the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

(1806). The relations between the Church and the First French Empire

First French Empire

The First French Empire , also known as the Greater French Empire or Napoleonic Empire, was the empire of Napoleon I of France...

declined following the Pope's refusal to divorce Jérôme Bonaparte

Jérôme Bonaparte

Jérôme-Napoléon Bonaparte, French Prince, King of Westphalia, 1st Prince of Montfort was the youngest brother of Napoleon, who made him king of Westphalia...

and Elizabeth Patterson

Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte

Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte , known as "Betsy", was the daughter of a Baltimore, Maryland merchant, and was the first wife of Jérôme Bonaparte, and sister-in-law of Emperor Napoleon I of France.-Ancestry:Elizabeth's father, William Patterson, had been born in Ireland and came to North America...

in 1805. The newly-crowned Emperor of the French restarted his expansionist policies and assumed control over Ancona

Ancona

Ancona is a city and a seaport in the Marche region, in central Italy, with a population of 101,909 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region....

, Naples (following the Battle of Austerlitz

Battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz, also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of Napoleon's greatest victories, where the French Empire effectively crushed the Third Coalition...

, making his brother Joseph Bonaparte

Joseph Bonaparte

Joseph-Napoléon Bonaparte was the elder brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, who made him King of Naples and Sicily , and later King of Spain...

its new monarch), Pontecorvo and Benevento

Benevento

Benevento is a town and comune of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, 50 km northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill 130 m above sea-level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino and Sabato...

. The changes angered the pope, and following his refusal to accept them, Napoleon, in February 1808, demanded he subsidise France's military conflict with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

. The pope again refused, leading to further confiscations of territory such as Urbino

Urbino

Urbino is a walled city in the Marche region of Italy, south-west of Pesaro, a World Heritage Site notable for a remarkable historical legacy of independent Renaissance culture, especially under the patronage of Federico da Montefeltro, duke of Urbino from 1444 to 1482...

, Ancona

Ancona

Ancona is a city and a seaport in the Marche region, in central Italy, with a population of 101,909 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region....

and Macerata

Macerata

Macerata is a city and comune in central Italy, the capital of the province of Macerata in the Marche region.The historical city center is located on a hill between the Chienti and Potenza rivers. It consisted of the Picenes city named Ricina, then, after the romanization, Recina and Helvia Recina...

. Finally in 1809, on May 17, the Papal states were formally annexed to the First French Empire and Pius VII was taken to the Château de Fontainebleau

Château de Fontainebleau

The Palace of Fontainebleau, located 55 kilometres from the centre of Paris, is one of the largest French royal châteaux. The palace as it is today is the work of many French monarchs, building on an early 16th century structure of Francis I. The building is arranged around a series of courtyards...

.

A unique conclave

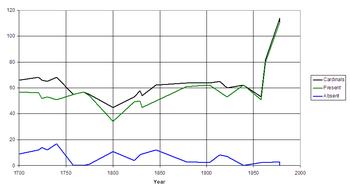

As the graph on the left demonstrates, the conclave was conducted with the fewest cardinals present since 1534, a total of 34. Indeed, due to the political situation in which the church found itself at the time it had just 45 cardinals in total, the lowest number since the 31 of 1513.

At 105 days (30 November–14 March) this also happens to be the longest conclave to date since its immediate predecessor, which lasted from October 5, 1774, until February 15, 1775, — a total of 133 days.

The extent to which the successor was debated, and the contentiousness of certain nominations, may be seen in the fact that the Austrian Emperor presented the veto twice — a unique occurrence in the history of the conclave; the Empire then included Venice, and had already denied the use of St. Mark's to the Cardinals for declining to accept the Austrian candidate. Typically, a single veto would have been used by a represented kingdom, to ensure that a particular objectionable candidate would not succeed.

List of participants

- Gian Francesco AlbaniGian Francesco AlbaniGian Francesco Albani was a Roman Catholic Cardinal. He was a member of the Albani family.Albani was born in Rome, the son of Carlo Albani, Duke of Soriano; his grand-uncle was Pope Clement XI...

, da Urbino, bishop of Ostia and Velletri - Henry Benedict StuartHenry Benedict StuartHenry Benedict Stuart was a Roman Catholic Cardinal, as well as the fourth and final Jacobite heir to publicly claim the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Unlike his father, James Francis Edward Stuart, and brother, Charles Edward Stuart, Henry made no effort to seize the throne...

, bishop of Frascati - Leonardo AntonelliLeonardo AntonelliLeonardo Antonelli was an Italian Cardinal in the Roman Catholic Church.A native of Senigallia, Antonelli was the nephew of Cardinal Nicolò Maria Antonelli...

, bishop of Palestrina - Luigi Valenti-Gonzaga, bishop of Albano

- Francesco Carafa di Trajetto

- Francesco Saverio de ZeladaFrancesco Saverio de ZeladaFrancesco Saverio [de] Zelada was a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, born of a Spanish family, who served in the Papal Curia and in the diplomatic service of the Holy See....

- Guido Calcagnini, bishop of Osimo e Cingoli

- Bernardino Honorati, bishop of Senigallia

- Andrea Gioannetti, archbishop of Bologna

- Hyacinthe Sigismond GerdilHyacinthe Sigismond GerdilHyacinthe Sigismond Gerdil was an Italian theologian and Cardinal.Gerdil was born at Samoëns in Savoie. When fifteen years old, he joined the Barnabites at Annecy, and was sent to Bologna to pursue his theological studies; there he devoted his mind to the various branches of knowledge with great...

, CRSPBarnabitesThe Barnabites, or Clerics Regular of Saint Paul is a Roman Catholic order.-Establishment of the Order :It was founded in 1530 by three Italian noblemen: St. Anthony Mary Zaccaria The Barnabites, or Clerics Regular of Saint Paul (Latin: Clerici Regulares Sancti Pauli, abbr. B.) is a Roman Catholic... - Carlo Giuseppe Filippo di Martiniana, bishop of Vercelli

- Alessandro MatteiAlessandro MatteiAlessandro Mattei was an Italian Cardinal, and a significant figure in papal diplomacy of the Napoleonic period. He was from the Roman aristocratic House of Mattei.He became Archbishop of Ferrara in 1777, and was created cardinal in 1779....

- Franziskus Herzan von Harras

- Giovanni Andrea ArchettiGiovanni Andrea ArchettiGiovanni Andrea Archetti was an Italian Roman Catholic CardinalBorn in Brescia, Lombardy, Archetti studied canon and civil law in La Sapienza University of Rome. He was ordained priest on September 10, 1775, elected titular archbishop of Chalcedon on the next day, and named Apostolic nuncio in...

, Archbishop-bishop of Ascoli Piceno - Giuseppe Maria Doria-Pamphili

- Gregorio Barnaba Chiaramonti, OSBOrder of Saint BenedictThe Order of Saint Benedict is a Roman Catholic religious order of independent monastic communities that observe the Rule of St. Benedict. Within the order, each individual community maintains its own autonomy, while the organization as a whole exists to represent their mutual interests...

, bishop of Imola (Elected Pope Pius VII) - Carlo Bellisomi, bishop of Cesena

- Francisco Antonio de LorenzanaFrancisco Antonio de LorenzanaFrancisco Antonio de Lorenzana y Butron was a Catholic Cardinal.After the completion of his studies at the Jesuit College of his native city, he entered the ecclesiastical state and was appointed, at an early date, to a canonry in Toledo. In 1765 he was named Bishop of Plasencia...

, archbishop of Toledo, Spain - Ignazio BuscaIgnazio BuscaIgnazio Busca was an Italian cardinal and Secretary of State of the Holy See. He was the last son of Lodovico Busca, marquess of Lomagna and Bianca Arconati Visconti. he took a degree in utroque iure in 1759 at the Università La Sapienza of Rome...

- Stefano BorgiaStefano BorgiaThe Most Rev. Dr. Stefano Cardinal Borgia was a senior Italian prelate, theologian, antiquarian and historian.Cardinal Borgia belonged to a well known family of Velletri, where he was born, and was a distant relative of the House of Borgia. His early education was controlled by his uncle...

- Giambattista Caprara

- Antonio Dugnani

- Ippolito Vicenti-Mareri

- Jean-Sifrein MauryJean-Sifrein MauryJean-Sifrein Maury was a French cardinal and Archbishop of Paris.-Biography:The son of a poor cobbler, he was born on at Valréas in the Comtat-Venaissin, the enclave within France that belonged to the pope. His acuteness was observed by the priests of the seminary at Avignon, where he was educated...

, Archbishop of ParisArchbishop of ParisThe Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Paris is one of twenty-three archdioceses of the Roman Catholic Church in France. The original diocese is traditionally thought to have been created in the 3rd century by St. Denis and corresponded with the Civitas Parisiorum; it was elevated to an archdiocese on...

, France - Giambattista Bussi de Pretis, bishop of Jesi

- Francesco Maria Pignatelli

- Aurelio Roverella

- Giulio Maria della SomagliaGiulio Maria della Somaglia-External links:*...

- Antonmaria Doria-Pamphili

- Romualdo Braschi-Onesti

- Filippo Carandini

- Ludovico Flangini Giovanelli

- Fabrizio Dionigi RuffoFabrizio RuffoFabrizio Ruffo was an Italian cardinal and politician, who led the popular anti-republican Sanfedismo movement .-Biography:...

- Giovanni Rinuccini

List of absentees

- Christoph Anton von Migazzi von Waal und Sonnenthurn, archbishop of ViennaArchbishop of ViennaThe Archbishop of Vienna is the prelate of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vienna who is concurrently the metropolitan bishop of its ecclesiastical province which includes the dioceses of Eisenstadt, Linz and St. Pölten....

, Austria - Dominique de La RochefoucauldDominique de La RochefoucauldDominique de La Rochefoucauld was a French abbot, bishop, archbishop, and Cardinal.- Before the French Revolution :...

, archbishop of RouenArchbishop of RouenThe Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Rouen is an Archdiocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church in France. As one of the fifteen Archbishops of France, the ecclesiastical province of the archdiocese comprises the majority of Normandy....

, France - Joannes-Henricus de FranckenbergJoannes-Henricus de FranckenbergJohann Heinrich, Graf von Frankenberg was Archbishop of Mechelen, Primate of the Low Countries, and a cardinal...

, archbishop of Mechlin, Belgium - Louis-René-Eduard de Rohan-Guéménée, archbishop of Strasbourg

- Giuseppe Maria Capece Zurlo Theat., archbishop of Naples

- Vicenzo Ranuzzi, bishop of Ancona e Umana

- Muzio Gallo

- Carlo Livizzani Forni

- José Francisco de Mendonça, patriarch of LisbonPatriarch of LisbonThe Patriarch of Lisbon is an honorary title possessed by the archbishop of the Archdiocese of Lisbon.The first patriarch of Lisbon was D. Tomás de Almeida, who was appointed in 1716 by Pope Clement XI...

, Portugal - Antonio de Sentmenat y Castella, patriarch of the Western Indies, Spain

- Louis-Joseph de Laval-MontmorencyLouis-Joseph de Laval-MontmorencyLouis-Joseph de Montmorency-Laval was a French cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was the bishop of Orléans, left the position after four years, only to become bishop of Condom for two years, and later bishop of Metz and "grand aumônier" of the French court...