Maria Callcott

Encyclopedia

Maria Graham later Maria, Lady Callcott (often erroneously styled by modern commentators 'Lady Maria Callcott'), was a British writer of travel books

Travel literature

Travel literature is travel writing of literary value. Travel literature typically records the experiences of an author touring a place for the pleasure of travel. An individual work is sometimes called a travelogue or itinerary. Travel literature may be cross-cultural or transnational in focus, or...

and children's books, and also an accomplished illustrator

Illustrator

An Illustrator is a narrative artist who specializes in enhancing writing by providing a visual representation that corresponds to the content of the associated text...

.

She was born near Cockermouth

Cockermouth

-History:The Romans created a fort at Derventio, now the adjoining village of Papcastle, to protect the river crossing, which had become located on a major route for troops heading towards Hadrian's Wall....

in Cumberland

Cumberland

Cumberland is a historic county of North West England, on the border with Scotland, from the 12th century until 1974. It formed an administrative county from 1889 to 1974 and now forms part of Cumbria....

as Maria Dundas, and didn't see much of her father during her childhood and teenage years, as he was one of the many naval officers that the Scottish Dundas clan

Clan Dundas

Clan Dundas is the name given to one of Scotland's most historically important families. Once widely regarded as one of the most noble in the British Empire...

has raised through the years. George Dundas (1756–1814) (not to be confused with the much more famous naval officer George Heneage Dundas

George Heneage Dundas

Rear Admiral George Heneage Lawrence Dundas CB was a senior naval officer and First Naval Lord.-Family:He was the fifth son of Thomas Dundas by his wife Charlotte, daughter of the third Earl Fitzwilliam.-HMS Queen Charlotte:In February 1800 George Heneage Dundas was aboard Lord Keith's flagship,...

) was made post-captain

Post-Captain

Post-captain is an obsolete alternative form of the rank of captain in the Royal Navy.The term served to distinguish those who were captains by rank from:...

in 1795 and saw plenty of action as commander of HMS Juno

HMS Juno (1780)

HMS Juno was a Royal Navy 32-gun Amazon-class fifth rate. This frigate served during the American War of Independence, and the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.-Construction and commissioning:...

, a Fifth Rate

Fifth-rate

In Britain's Royal Navy during the classic age of fighting sail, a fifth rate was the penultimate class of warships in a hierarchal system of six "ratings" based on size and firepower.-Rating:...

32-gun frigate

Frigate

A frigate is any of several types of warship, the term having been used for ships of various sizes and roles over the last few centuries.In the 17th century, the term was used for any warship built for speed and maneuverability, the description often used being "frigate-built"...

, between 1798 and 1802. In 1803 he was given the command of HMS Elephant

HMS Elephant (1786)

HMS Elephant was a 74-gun third-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy. She was built by George Parsons in Bursledon, Hampshire, and launched on 24 August 1786....

, a 74 gun third-rate

Third-rate

In the British Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks . Years of experience proved that the third rate ships embodied the best compromise between sailing ability , firepower, and cost...

that had been Nelson's

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronté, KB was a flag officer famous for his service in the Royal Navy, particularly during the Napoleonic Wars. He was noted for his inspirational leadership and superb grasp of strategy and unconventional tactics, which resulted in a number of...

flagship

Flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, reflecting the custom of its commander, characteristically a flag officer, flying a distinguishing flag...

during the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, and took her down to Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

to patrol the Caribbean waters until 1806.

In 1808 his sea-fighting years were over and he took an appointment as head of the naval works at the British East India Company

British East India Company

The East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

's dockyard in Bombay. When he went out to India he brought his now 23-year-old daughter along. During the long trip Maria fell in love with a young Scottish naval officer aboard, Thomas Graham, third son to Robert Graham, the last Laird

Laird

A Laird is a member of the gentry and is a heritable title in Scotland. In the non-peerage table of precedence, a Laird ranks below a Baron and above an Esquire.-Etymology:...

of Fintry

Fintry

Fintry is a small village in central Scotland, nestled in the strath of the Endrick Water between the Campsie Fells and the Fintry Hills, some 19 miles north of Glasgow. It is within the local government council area of Stirling...

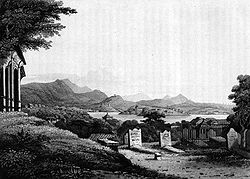

. They married in India in 1809. In 1811, the young couple returned to England, where Maria published her first book, Journal of a Residence in India, followed soon afterwards by Letters on India. A few years later her father was appointed Commissioner of the naval dockyard in Cape Town

Cape Town

Cape Town is the second-most populous city in South Africa, and the provincial capital and primate city of the Western Cape. As the seat of the National Parliament, it is also the legislative capital of the country. It forms part of the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality...

, where he died in 1814, aged 58, having been promoted rear-admiral just two months earlier.

Widow in Chile

As all other naval officers' wives, Maria spent several years ashore, seldom seeing her husband. Most of these years she lived in London. But while other officers’ wives spent their time with domestic chores, she worked as a translator and book editor. In 1819 she lived in Italy for a time, which resulted in the book Three Months Passed in the Mountains East of Rome, during the Year 1819. Being very interested in the arts, she also wrote a book about the French baroque painter Nicolas PoussinNicolas Poussin

Nicolas Poussin was a French painter in the classical style. His work predominantly features clarity, logic, and order, and favors line over color. His work serves as an alternative to the dominant Baroque style of the 17th century...

, Memoirs of the Life of Nicholas Poussin (French first names were usually Anglicised in those days), in 1820.

HMS Doris (1808)

HMS Doris was a 36-gun fifth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy that served between 1808 and 1829. She was the second ship of the Royal Navy to be named after the mythical Greek sea nymphe Doris....

, a 36 gun frigate under his command. The destination was Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

, and the purpose was to protect British mercantile interests in the area. In April 1822, shortly after the ship had rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn

Cape Horn is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island...

, her husband died of a fever, so HMS Doris arrived in Valparaiso

Valparaíso

Valparaíso is a city and commune of Chile, center of its third largest conurbation and one of the country's most important seaports and an increasing cultural center in the Southwest Pacific hemisphere. The city is the capital of the Valparaíso Province and the Valparaíso Region...

without a captain, but with a distraught captain’s widow. All the naval officers stationed in Valparaiso – British, Chilean and American – tried to help Maria (one American captain even offered to sail her back to Britain), but she was determined to manage on her own. She rented a small cottage, turned her back on the English colony ("I say nothing of the English here, because I do not know them except as very civil vulgar people, with one or two exceptions", she later wrote), and lived among the Chileans for a whole year. Later in 1822, she experienced one of Chile’s worst earthquake

Earthquake

An earthquake is the result of a sudden release of energy in the Earth's crust that creates seismic waves. The seismicity, seismism or seismic activity of an area refers to the frequency, type and size of earthquakes experienced over a period of time...

s in history, and recorded its effects in detail – something nobody had done before.

Tutor to the princess

Brazil

Brazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

and was introduced to the newly appointed Brazilian emperor and his family. The year before, the Brazilians had declared independence from Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

and had asked the resident Portuguese crown prince

Crown Prince

A crown prince or crown princess is the heir or heiress apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The wife of a crown prince is also titled crown princess....

, Dom Pedro to become their emperor. It was agreed that Maria should become the tutor of the young princess Donna Maria, so when she reached London, she just handed over the manuscripts of her two new books to her publisher (Journal of a Residence in Chile during the Year 1822. And a Voyage from Chile to Brazil in 1823 and Journal of a Voyage to Brazil, and Residence There, During Part of the Years 1821, 1822, 1823, illustrated by herself), collected suitable educational material, and returned to Brazil in 1824. She stayed in the royal palace only until October of that year, when she was asked to leave due to courtiers' suspicion of her motives and methods (courtiers seem to have feared, with some justice, that she intended to Anglicize the princess Maria da Gloria). During her few months with the royal family, she developed a close friendship with the empress, Archduchess Maria Leopoldina of Austria, who passionately shared her interests in the natural sciences. After leaving the palace, Maria Graham experienced further difficulties in arranging for her transport home; unwillingly, she remained in Brazil until 1825, when she finally managed to arrange a passport and passage to England. Her treatment by palace courtiers left her with ambivalent feelings about Brazil and its government; she later recorded her version of events in her unpublished manuscript "Memoir of the Life of Don Pedro".

In March 1826, King João VI of Portugal died. His son Pedro inherited the throne, but preferred to remain Emperor of Brazil, so he abdicated the Portuguese throne in favour of his six-year-old daughter after two months. So, Maria Graham’s little chubby pupil suddenly became Maria II, Queen of Portugal.

Second marriage

Having arrived in LondonLondon

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, Maria Graham took rooms in Kensington Gravel Pits, just south of Notting Hill Gate

Notting Hill Gate

Notting Hill Gate is one of the main thoroughfares of Notting Hill, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically the street was a location for toll gates, from which it derives its modern name.- Location :...

, which was something of an artists’ enclave. There lived the Royal Academy

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly, London. The Royal Academy of Arts has a unique position in being an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects whose purpose is to promote the creation, enjoyment and...

painter Augustus Wall Callcott

Augustus Wall Callcott

Sir Augustus Wall Callcott was an English landscape painter-Life and work:Callcott was born in Kensington gravel pits, London. His first study was music and he sang for several years in the choir of Westminster Abbey...

and his musician brother John Wall Callcott

John Wall Callcott

John Wall Callcott was an eminent English musical composer.Callcott was born in Kensington, London. He was a pupil of Haydn, and is celebrated mainly for his glee compositions and "catches". In the best known of his catches he ridiculed Sir John Hawkins' History of Music...

, but also painters like John Linnell

John Linnell (painter)

John Linnell was an English landscape painter. Linnell was a naturalist and a rival to John Constable. He had a taste for Northern European art of the Renaissance, particularly Albrecht Dürer. He also associated with William Blake, to whom he introduced Samuel Palmer and others of the...

, David Wilkie

David Wilkie (artist)

Sir David Wilkie was a Scottish painter.- Early life :Wilkie was the son of the parish minister of Cults in Fife. He developed a love for art at an early age. In 1799, after he had attended school at Pitlessie, Kettle and Cupar, his father reluctantly agreed to his becoming a painter...

and William Mulready

William Mulready

William Mulready was an Irish genre painter living in London. He is best known for his romanticizing depictions of rural scenes, and for creating Mulready stationery letter sheets, issued at the same time as the Penny Black postage stamp.-Life and family:William Mulready was born in Ennis, County...

, and musicians such as William Crotch

William Crotch

William Crotch was an English composer, organist and artist.Born in Norwich to a master carpenter he showed early musical talent . The three and a half year old Master William Crotch was taken to London by his ambitious mother, where he not only played on the organ of the Chapel Royal in St....

(the first principal of the Royal Academy of Music

Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music in London, England, is a conservatoire, Britain's oldest degree-granting music school and a constituent college of the University of London since 1999. The Academy was founded by Lord Burghersh in 1822 with the help and ideas of the French harpist and composer Nicolas...

) and William Horsley

William Horsley

William Horsley was an English musician.In 1790 he became the pupil of Theodore Smith, an indifferent musician of the time, who, however, taught him sufficiently well to obtain the position of organist at Ely Chapel, Holborn, in 1794...

(John Callcott’s son-in-law). In addition, this close-knit group was frequently visited by artists like John Varley

John Varley (painter)

John Varley was an English watercolour painter and astrologer, and a close friend of William Blake. They collaborated in 1819–1820 on the book Visionary Heads, written by Varley and illustrated by Blake...

, Edwin Landseer, John Constable

John Constable

John Constable was an English Romantic painter. Born in Suffolk, he is known principally for his landscape paintings of Dedham Vale, the area surrounding his home—now known as "Constable Country"—which he invested with an intensity of affection...

and J.M.W. Turner.

Maria’s lodgings very quickly became a focal point for London’s intellectuals, such as the Scottish poet Thomas Campbell, Maria’s book publisher John Murray

John Murray (publisher)

John Murray is an English publisher, renowned for the authors it has published in its history, including Jane Austen, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Lord Byron, Charles Lyell, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Herman Melville, and Charles Darwin...

and the historian Francis Palgrave

Francis Palgrave

Sir Francis Palgrave FRS, born Francis Ephraim Cohen, was an English historian.- Early life :He was born in London, the son of Meyer Cohen, a Jewish stockbroker by his wife Rachel Levien Cohen . He was initially articled as a clerk to a London solicitor's firm, and remained there as chief clerk...

, but her keen interest and knowledge of painting (she was a skilled illustrator of her own books, and had written the book about Poussin) made it inevitable that she would quickly become part of the artists’ enclave as well.

It must have been love at first sight when Maria Graham and Augustus Callcott met, because they married on his 48th birthday, 20 February 1827. They immediately left for a year-long honeymoon

Honeymoon

-History:One early reference to a honeymoon is in Deuteronomy 24:5 “When a man is newly wed, he need not go out on a military expedition, nor shall any public duty be imposed on him...

to Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

and the Habsburg Monarchy. It was his first trip abroad, and he obviously enjoyed it. From then on he would travel extensively, both to Europe and the Middle East, with Maria as well as with friends like Turner.

Invalid in Italy

In 1831, during a trip in Italy, Maria Callcott ruptured a blood vessel and became an invalid. She could no longer travel, but she could continue to entertain her friends, and could continue her writing.After her return from Brazil in 1825, her publisher, John Murray, had asked her to create a book about the famous and recently completed voyage of HMS Blonde

HMS Blonde (1819)

HMS Blonde was a 46-gun modified Apollo-class fifth-rate frigate of 1,103 tons burthen. She undertook an important voyage to the Pacific in 1824...

to the Sandwich Islands (as Hawaii

Hawaii

Hawaii is the newest of the 50 U.S. states , and is the only U.S. state made up entirely of islands. It is the northernmost island group in Polynesia, occupying most of an archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean, southwest of the continental United States, southeast of Japan, and northeast of...

was then known). King Kamehameha II

Kamehameha II

Kamehameha II was the second king of the Kingdom of Hawaii. His birth name was Liholiho and full name was Kalaninui kua Liholiho i ke kapu Iolani...

of Hawaii and his Queen Kamamalu had been on a visit to London in 1824, when they both died of the measles

Measles

Measles, also known as rubeola or morbilli, is an infection of the respiratory system caused by a virus, specifically a paramyxovirus of the genus Morbillivirus. Morbilliviruses, like other paramyxoviruses, are enveloped, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA viruses...

, against which they had no immunity. HMS Blonde was commissioned by the British Government to return their bodies to the Hawaiian Islands, with George Anson Byron, a cousin of the poet Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, later George Gordon Noel, 6th Baron Byron, FRS , commonly known simply as Lord Byron, was a British poet and a leading figure in the Romantic movement...

, in command. The resulting book contained a history of the exotic royal couple's unfortunate visit to London, a résumé of the discovery of the Hawaiian Islands and visits by British explorers, as well as the story about Blonde’s journey. Maria wrote it with the help of official papers and journals kept by the chaplain, R. Rowland Bloxam; there is also a short section based on the records of the naturalist Andrew Bloxam

Andrew Bloxam

Andrew Bloxam was an English clergyman and naturalist; in his later life he had a particular interest in botany. He was the naturalist on board during its voyage around South America and the Pacific in 1824–26, where he collected mainly birds...

.

In 1828, immediately after returning from their honeymoon, she published A Short History of Spain, and in 1835 her writings during her long convalescence resulted in the publication of two books; Description of the chapel of the Annunziata dell’Arena; or Giotto’s Chapel in Padua, and her first and most famous book for children; Little Arthur’s History of England, which has been reprinted numerous times since then (already in 1851 the 16th edition was published, and it was last reprinted in 1975). Little Arthur was followed in 1836 by a French version; Histoire de France du petit Louis.

Caused geological debate

In the mid 1830s her description of the earthquake in Chile of 1822 started a heated debate in the Geological Society, where she was caught in the middle of a fight between two rivalling schools of thought regarding earthquakes and their role in mountain building. Besides describing the earthquake in her Journal of a Residence in Chile, she had also written about it in more detail in a letter to Henry WarburtonHenry Warburton

Henry Warburton was an English merchant and politician, and also an enthusiastic amateur scientist....

, who was one of the Geological Society’s founding fathers. As this was one of the first detailed eyewitness accounts by "a learned person" of an earthquake, he found it interesting enough to publish in Transactions of the Geological Society of London in 1823.

One of her observations had been that of large areas of land rising from the sea, and in 1830 that observation was included in the groundbreaking work The Principles of Geology by the geologist Charles Lyell

Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, Kt FRS was a British lawyer and the foremost geologist of his day. He is best known as the author of Principles of Geology, which popularised James Hutton's concepts of uniformitarianism – the idea that the earth was shaped by slow-moving forces still in operation...

, as evidence in support of his theory that mountains were formed by volcanoes and earthquakes. Four years later the president of the Society, George Bellas Greenough

George Bellas Greenough

George Bellas Greenough FRS , an English geologist, was born in London.-Biography:Greenough was born George Bellas, named after his father, George Bellas, who had a profitable business in the legal profession as a proctor in Doctor's Commons, St Paul's Churchyard Doctors' Commons and some real...

, decided to attack Lyell’s theories. But instead of attacking Lyell directly, he did it by publicly ridiculing Maria Callcott’s observations.

Maria Callcott, however, was not someone who accepted ridicule. Her husband and her brother offered to duel Greenough, but she said, according to her nephew John Callcott Horsley

John Callcott Horsley

John Callcott Horsley RA , was an English Academic painter of genre and historical scenes, illustrator, and designer of the first Christmas card. He was a member of the artist's colony in Cranbrook.-Life:...

, "Be quiet, both of you, I am quite capable of fighting my own battles, and intend to do it". She went on to publish a crushing reply to Greenough, and was shortly thereafter backed by none other than Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

, who had observed the same land rising during Chile’s earthquake in 1835, aboard the Beagle

HMS Beagle

HMS Beagle was a Cherokee-class 10-gun brig-sloop of the Royal Navy. She was launched on 11 May 1820 from the Woolwich Dockyard on the River Thames, at a cost of £7,803. In July of that year she took part in a fleet review celebrating the coronation of King George IV of the United Kingdom in which...

.

In 1837 Augustus Callcott was knight

Knight

A knight was a member of a class of lower nobility in the High Middle Ages.By the Late Middle Ages, the rank had become associated with the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct for the perfect courtly Christian warrior....

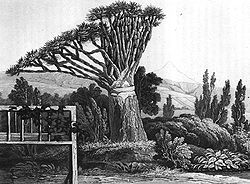

ed, Maria thus becoming Lady Callcott. But shortly afterwards her health began to deteriorate, and in 1842 she died, 57 years old. She continued to write until the very end, and her last book was A Scripture Herbal, an illustrated collection of tidbits and anecdotes about plants and trees mentioned in the Bible, which was published the same year she died.

Augustus Callcott died two years later, at the age of 65, having been made Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures

Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures

The office of the Surveyor of the King's/Queen's Pictures, in the Royal Collection Department of the Royal Household of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom, is responsible for the care and maintenance of the royal collection of pictures owned by the Sovereign in an official capacity – as...

in 1843.

Honoured in 2008

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

, as being one of the first persons to write about the young nation in the English language, the Chilean government

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

paid for the restoration of Maria and Augustus Callcott’s joint grave in Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in Kensal Green, in the west of London, England. It was immortalised in the lines of G. K. Chesterton's poem The Rolling English Road from his book The Flying Inn: "For there is good news yet to hear and fine things to be seen; Before we go to Paradise by way of...

in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

in 2008.

The restoration was finalised with a commemorative plaque

Commemorative plaque

A commemorative plaque, or simply plaque, is a plate of metal, ceramic, stone, wood, or other material, typically attached to a wall, stone, or other vertical surface, and bearing text in memory of an important figure or event...

, unveiled by the Chilean ambassador

Ambassador

An ambassador is the highest ranking diplomat who represents a nation and is usually accredited to a foreign sovereign or government, or to an international organization....

to the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, Rafael Moreno, at a ceremony on 4 September 2008. The plaque names Maria Callcott "a friend of the nation of Chile".

Works

- As Maria Graham:

- Memoirs of the war of the French in Spain (by Albert Jean Rocca) - translation from French (1816)

- Journal of a Residence in India (1812) - translated into French 1818

- Letters on India, with Etchings and a Map (1814)

- Three Months Passed in the Mountains East of Rome, during the Year 1819, 1820 (1821)

- Memoir of the Life of Nicolas Poussin (1820)

- Journal of a Residence in Chile during the Year 1822. And a Voyage from Chile to Brazil in 1823 (1824)

- Journal of a Voyage to Brazil, and Residence There, During Part of the Years 1821, 1822, 1823 (1824)

- Voyage Of The H.M.S. Blonde To The Sandwich Islands, In The Years 1824-1825 (1826)

- As Maria Callcott or Lady Callcott:

- A Short History of Spain (1828)

- Description of the chapel of the Annuziata dell'Arena; or Giotto's Chapel in Padua (1835)

- Little Arthur's History of England (1835)

- Histoire de France du petit Louis (1836)

- Essays Towards the History of Painting (1836)

- The Little Bracken-Burners - A Tale; and Little Mary's Four Saturdays (1841)

- A Scripture Herbal (1842)

Sources

- Recollections of a Royal Academician by John Callcott Horsley. 1903

- The Cherry Tree No. 2, 2004, published by the Cherry Tree Residents' Amenities Association in Kensington, London

External links

- Facsimile online version of Journal of a Voyage to Brazil - with her illustrations Retrieved 27 January 2006

- Paper by Dr. Martina Kölbl-Ebert about Maria Callcott's geological debacle Retrieved 8 September 2008

- The Maria Graham Project Website at Nottingham Trent University This site provides various resources and documents relating to Graham. Retrieved 27 March 2009