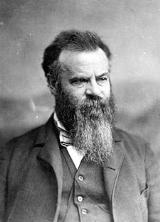

John Wesley Powell

Encyclopedia

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

soldier, geologist

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

, explorer of the American West, and director of major scientific and cultural institutions. He is famous for the 1869 Powell Geographic Expedition

Powell Geographic Expedition of 1869

The Powell Geographic Expedition was a groundbreaking 19th century U.S. exploratory expedition of the American West, led by John Wesley Powell in 1869, that provided the first-ever thorough investigation of the Green and Colorado rivers, including the first known passage through the Grand Canyon...

, a three-month river trip down the Green

Green River (Utah)

The Green River, located in the western United States, is the chief tributary of the Colorado River. The watershed of the river, known as the Green River Basin, covers parts of Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. The Green River is long, beginning in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming and flowing...

and Colorado rivers that included the first known passage through the Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon is a steep-sided canyon carved by the Colorado River in the United States in the state of Arizona. It is largely contained within the Grand Canyon National Park, the 15th national park in the United States...

.

Powell served as second director of the US Geological Survey (1881–1894) and proposed policies for development of the arid West which were prescient for his accurate evaluation of conditions. He was director of the Bureau of Ethnology

Bureau of American Ethnology

The Bureau of American Ethnology was established in 1879 by an act of Congress for the purpose of transferring archives, records and materials relating to the Indians of North America from the Interior Department to the Smithsonian Institution...

at the Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

, where he supported linguistic

Linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. Linguistics can be broadly broken into three categories or subfields of study: language form, language meaning, and language in context....

and sociological research and publications.

Early life and education

Powell was born in Mount Morris, New YorkMount Morris (village), New York

Mount Morris is a village located in the Town of Mount Morris in Livingston County, New York, USA. The population was 3,266 at the 2000 census. The village and town are named after Robert Morris....

, in 1834, the son of Joseph and Mary Powell. His father, a poor itinerant preacher, had emigrated to the U.S. from Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury is the county town of Shropshire, in the West Midlands region of England. Lying on the River Severn, it is a civil parish home to some 70,000 inhabitants, and is the primary settlement and headquarters of Shropshire Council...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, in 1830. His family moved westward to Jackson, Ohio

Jackson, Ohio

Jackson is a city in and the county seat of Jackson County, Ohio, United States. The population was 6,184 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Jackson is located at ....

, then Walworth County, Wisconsin

Walworth County, Wisconsin

Walworth County is a county located in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of 2010, the population was 102,228. Its county seat is Elkhorn.-Geography:According to the U.S...

, before settling in Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

in rural Boone County.

Powell studied at Illinois College

Illinois College

Illinois College is a private, liberal arts college, affiliated with the United Church of Christ and the Presbyterian Church , and located in Jacksonville, Illinois. It was the second college founded in Illinois, but the first to grant a degree . It was founded in 1829 by the Illinois Band,...

, Wheaton College and Oberlin College

Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a private liberal arts college in Oberlin, Ohio, noteworthy for having been the first American institution of higher learning to regularly admit female and black students. Connected to the college is the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, the oldest continuously operating...

, acquiring a knowledge of Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

and Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

. Powell had a restless nature and a deep interest in the natural science

Natural science

The natural sciences are branches of science that seek to elucidate the rules that govern the natural world by using empirical and scientific methods...

s. As a young man he undertook a series of adventures through the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

valley. In 1855, he spent four months walking across Wisconsin

Wisconsin

Wisconsin is a U.S. state located in the north-central United States and is part of the Midwest. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michigan to the northeast, and Lake Superior to the north. Wisconsin's capital is...

. During 1856, he rowed the Mississippi from St. Anthony

Saint Anthony Falls

Saint Anthony Falls, or the Falls of Saint Anthony, located northeast of downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota, was the only natural major waterfall on the Upper Mississippi River. The natural falls was replaced by a concrete overflow spillway after it partially collapsed in 1869...

, Minnesota

Minnesota

Minnesota is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. The twelfth largest state of the U.S., it is the twenty-first most populous, with 5.3 million residents. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state...

, to the sea. In 1857, he rowed down the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

from Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh is the second-largest city in the US Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the county seat of Allegheny County. Regionally, it anchors the largest urban area of Appalachia and the Ohio River Valley, and nationally, it is the 22nd-largest urban area in the United States...

to St. Louis

St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis is an independent city on the eastern border of Missouri, United States. With a population of 319,294, it was the 58th-largest U.S. city at the 2010 U.S. Census. The Greater St...

; and in 1858 down the Illinois River

Illinois River

The Illinois River is a principal tributary of the Mississippi River, approximately long, in the State of Illinois. The river drains a large section of central Illinois, with a drainage basin of . This river was important among Native Americans and early French traders as the principal water route...

, then up the Mississippi and the Des Moines River

Des Moines River

The Des Moines River is a tributary river of the Mississippi River, approximately long to its farther headwaters, in the upper Midwestern United States...

to central Iowa

Iowa

Iowa is a state located in the Midwestern United States, an area often referred to as the "American Heartland". It derives its name from the Ioway people, one of the many American Indian tribes that occupied the state at the time of European exploration. Iowa was a part of the French colony of New...

. At age 25 he was elected to the Illinois Natural History Society in 1859.

Civil War and aftermath

Due to Powell's deep Protestant beliefs and social commitments, his loyalties remained with the UnionThe Union

-Political Unions:* The Union states of the United States during the American Civil War* The partnership of the German political parties the Christian Democratic Union and the Christian Social Union* The European Union...

and the cause of abolishing slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

. On May 8, 1861, he enlisted at Hennepin, Illinois, as a private in the 20th Illinois Infantry. He was described as "age 27, height 5' 6-1/2" tall, light complected, gray eyes, auburn hair, occupation—teacher." He was elected sergeant-major of the regiment, and when the 20th Illinois was mustered into the Federal service a month later, Powell was commissioned a second lieutenant. He enlisted in the Union Army as a cartographer, topographer and military engineer

Engineer

An engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems. Engineers design materials, structures, machines and systems while considering the limitations imposed by practicality,...

. During the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

he served first with the 20th Illinois Volunteers. While stationed at Cape Girardeau

Cape Girardeau, Missouri

Cape Girardeau is a city located in Cape Girardeau and Scott counties in Southeast Missouri in the United States. It is located approximately southeast of St. Louis and north of Memphis. As of the 2010 census, the city's population was 37,941. A college town, it is the home of Southeast Missouri...

, Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

, he recruited an artillery company that became Battery "F" of the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery with Powell as captain. On November 28, 1861, Powell took a brief leave to marry the former Emma Dean. At the Battle of Shiloh

Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a major battle in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, fought April 6–7, 1862, in southwestern Tennessee. A Union army under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had moved via the Tennessee River deep into Tennessee and...

, he lost most of one arm when struck by a minie ball

Minié ball

The Minié ball is a type of muzzle-loading spin-stabilising rifle bullet named after its co-developer, Claude-Étienne Minié, inventor of the Minié rifle...

. The raw nerve

Nerve

A peripheral nerve, or simply nerve, is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of peripheral axons . A nerve provides a common pathway for the electrochemical nerve impulses that are transmitted along each of the axons. Nerves are found only in the peripheral nervous system...

endings in his arm would continue to cause him pain the rest of his life. Despite the loss of an arm, he returned to the Army and was present at Champion Hill

Battle of Champion Hill

The Battle of Champion Hill, or Bakers Creek, fought May 16, 1863, was the pivotal battle in the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. Union commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee pursued the retreating Confederate Lt. Gen. John C...

, Big Black River Bridge

Battle of Big Black River Bridge

The Battle of Big Black River Bridge, or Big Black, fought May 17, 1863, was part of the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. Union commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee pursued the retreating Confederate Lt. Gen. John C...

on the Big Black River and in the siege of Vicksburg. Always the geologist he took to studying rocks while in the trenches at Vicksburg. He was made a major

Major (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, major is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel...

and commanded an artillery

Artillery

Originally applied to any group of infantry primarily armed with projectile weapons, artillery has over time become limited in meaning to refer only to those engines of war that operate by projection of munitions far beyond the range of effect of personal weapons...

brigade with the 17th Army Corps

XVII Corps (ACW)

XVII Corps was a corps of the Union Army during the American Civil War. It was organized December 18, 1862 as part of Ulysses S. Grant's Army of the Tennessee. It was most notably commanded by Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson and Maj. Gen. Francis P. Blair II, and served in the Western...

during the Atlanta Campaign

Atlanta Campaign

The Atlanta Campaign was a series of battles fought in the Western Theater of the American Civil War throughout northwest Georgia and the area around Atlanta during the summer of 1864. Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman invaded Georgia from the vicinity of Chattanooga, Tennessee, beginning in May...

. After the fall of Atlanta he was transferred to George H. Thomas' army and participated in the battle of Nashville

Battle of Nashville

The Battle of Nashville was a two-day battle in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign that represented the end of large-scale fighting in the Western Theater of the American Civil War. It was fought at Nashville, Tennessee, on December 15–16, 1864, between the Confederate Army of Tennessee under...

. At the end of the war he was made a brevet

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel is a rank of commissioned officer in the armies and most marine forces and some air forces of the world, typically ranking above a major and below a colonel. The rank of lieutenant colonel is often shortened to simply "colonel" in conversation and in unofficial correspondence...

, but despite this he continued to be referred to as "Major".

After leaving the Army, Powell took the post of professor of geology

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

at Illinois Wesleyan University

Illinois Wesleyan University

Illinois Wesleyan University is an independent undergraduate university located in Bloomington, Illinois. Founded in 1850, the central portion of the present campus was acquired in 1854 with the first building erected in 1856...

. He also lectured at Illinois State Normal University

Illinois State University

Illinois State University , founded in 1857, is the oldest public university in Illinois; it is located in the town of Normal. ISU is considered a "national university" that grants a variety of doctoral degrees and strongly emphasizes research; it is also recognized as one of the top ten largest...

for most of his career. Powell helped found the Illinois Museum of Natural History, where he served as the curator

Curator

A curator is a manager or overseer. Traditionally, a curator or keeper of a cultural heritage institution is a content specialist responsible for an institution's collections and involved with the interpretation of heritage material...

. He declined a permanent appointment in favor of exploration of the American West.

Expeditions

From 1867 Powell led a series of expeditions into the Rocky MountainsRocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains are a major mountain range in western North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch more than from the northernmost part of British Columbia, in western Canada, to New Mexico, in the southwestern United States...

and around the Green

Green River (Utah)

The Green River, located in the western United States, is the chief tributary of the Colorado River. The watershed of the river, known as the Green River Basin, covers parts of Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. The Green River is long, beginning in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming and flowing...

and Colorado rivers. In 1869 he set out to explore the Colorado and the Grand Canyon. Gathering nine men, four boats and food for 10 months, he set out from Green River, Wyoming

Green River, Wyoming

Green River is a city in and the county seat of Sweetwater County, Wyoming, United States, in the southwestern part of the state. The population was 11,808 at the 2000 census....

on May 24. Passing through dangerous rapids, the group passed down the Green River to its confluence

Confluence

Confluence, in geography, describes the meeting of two or more bodies of water.Confluence may also refer to:* Confluence , a property of term rewriting systems...

with the Colorado River (then also known as the Grand River upriver from the junction), near present-day Moab, Utah

Moab, Utah

Moab is a city in Grand County, in eastern Utah, in the western United States. The population was 4,779 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat and largest city in Grand County. Moab hosts a large number of tourists every year, mostly visitors to the nearby Arches and Canyonlands National Parks...

and completed the journey on August 13, 1869. The expedition's route traveled through the Utah canyons of the Colorado River, which Powell described in his published diary as having

". . . wonderful features—carved walls, royal arches, glens, alcove gulches, mounds and monuments. From which of these features shall we select a name? We decide to call it Glen CanyonGlen CanyonGlen Canyon is a canyon that is located in southeastern and south central Utah and northwestern Arizona within the Vermilion Cliffs area. It was carved by the Colorado River....

."

One man (Goodman) quit after the first month, and another three (Dunn and the Howland brothers) left at Separation Canyon in the third. This was just two days before the group reached the mouth of the Virgin River

Virgin River

The Virgin River is a tributary of the Colorado River in the U.S. states of Utah, Nevada, and Arizona. The river is about long. It was designated Utah's first wild and scenic river in 2009, during the centennial celebration of Zion National Park.-Course:...

on August 30, after traversing almost 930 mi (1,496.7 km). The latter three disappeared; historians have speculated they were killed by the Shivwitz

Shivwitz

The Shivwits Band of Paiutes are a band of the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, a federally recognized tribe of Southern Paiutes located in southwestern Utah.-History:...

band of the Northern Paiute

Paiute

Paiute refers to three closely related groups of Native Americans — the Northern Paiute of California, Idaho, Nevada and Oregon; the Owens Valley Paiute of California and Nevada; and the Southern Paiute of Arizona, southeastern California and Nevada, and Utah.-Origin of name:The origin of...

. How and why they died remains a mystery debated by Powell biographers.

Powell retraced the route in 1871-1872 with another expedition, resulting in photographs (by John K. Hillers

John K. Hillers

John Karl Hillers was an American government photographer.Hillers came to the United States in 1852. He was a policeman and then a soldier in the American Civil War, first with the New York Naval Brigade, then in the army, he re-enlisted after the war and served with the Western garrisons until 1870...

), an accurate map and various papers. In planning this expedition, he employed the services of Jacob Hamblin

Jacob Hamblin

Jacob Vernon Hamblin was a Western pioneer, Mormon missionary, and diplomat to various Native American Tribes of the Southwest and Great Basin. During his life, he helped settle large areas of southern Utah and northern Arizona where he was seen as an honest broker between Mormon settlers and the...

, a Mormon missionary

Missionary

A missionary is a member of a religious group sent into an area to do evangelism or ministries of service, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care and economic development. The word "mission" originates from 1598 when the Jesuits sent members abroad, derived from the Latin...

in southern Utah

Utah

Utah is a state in the Western United States. It was the 45th state to join the Union, on January 4, 1896. Approximately 80% of Utah's 2,763,885 people live along the Wasatch Front, centering on Salt Lake City. This leaves vast expanses of the state nearly uninhabited, making the population the...

and northern Arizona

Arizona

Arizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

, who had cultivated excellent relationships with Native Americans. Before setting out, Powell used Hamblin as a negotiator to ensure the safety of his expedition from local Indian groups. Powell believed they had killed the three men lost from his previous expedition. Wallace Stegner

Wallace Stegner

Wallace Earle Stegner was an American historian, novelist, short story writer, and environmentalist, often called "The Dean of Western Writers"...

states that Powell knew the men had been killed by the Indians in a case of mistaken identity.

Members of the first Powell expedition:

- John Wesley Powell, trip organizer and leader, major in the Civil War

- J. C. Sumner, hunter, trapper, soldier in the Civil War

- William H. Dunn, hunter, trapper from Colorado

- W. H. Powell, captain in the Civil War

- G.Y. Bradley, lieutenant in the Civil War, expedition chronicler

- O. G. Howland, printer, editor, hunter

- Seneca Howland

- Frank Goodman, Englishman, adventurer

- W. R. Hawkins, cook, soldier in Civil War

- Andrew Hall, Scotsman, the youngest of the expedition

- F.M. Bishop, cartographer

After the Colorado

In 1874 the intellectual gatherings Powell hosted in his home were formalized as the Cosmos ClubCosmos Club

The Cosmos Club is a private social club in Washington, D.C., founded by John Wesley Powell in 1878. In addition to Powell, original members included Clarence Edward Dutton, Henry Smith Pritchett, William Harkness, and John Shaw Billings. Among its stated goals is "The advancement of its members in...

. The club has continued, with members elected to the club for their contributions to scholarship and civic activism

Activism

Activism consists of intentional efforts to bring about social, political, economic, or environmental change. Activism can take a wide range of forms from writing letters to newspapers or politicians, political campaigning, economic activism such as boycotts or preferentially patronizing...

.

In 1881, Powell was appointed the second director of the US Geological Survey, a post he held until 1894. He was also the director of the Bureau of Ethnology

Bureau of American Ethnology

The Bureau of American Ethnology was established in 1879 by an act of Congress for the purpose of transferring archives, records and materials relating to the Indians of North America from the Interior Department to the Smithsonian Institution...

at the Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

until his death. Under his leadership, the Smithsonian published an influential classification of North American Indian languages.

In 1875, Powell published a book based on his explorations of the Colorado, originally titled Report of the Exploration of the Columbia River of the West and Its Tributaries. It was revised and reissued in 1895 as The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons

The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons

The Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons by John Wesley Powell is a classic of American exploration literature. It is about the Powell Geographic Expedition of 1869 which was the first trip down the Colorado River by boat, including the first trip through the Grand Canyon.Powell's...

.

Legacy and honors

- In recognition of his national service, Powell was buried in Arlington National CemeteryArlington National CemeteryArlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, is a military cemetery in the United States of America, established during the American Civil War on the grounds of Arlington House, formerly the estate of the family of Confederate general Robert E. Lee's wife Mary Anna Lee, a great...

. - Lake PowellLake PowellLake Powell is a huge reservoir on the Colorado River, straddling the border between Utah and Arizona . It is the second largest man-made reservoir in the United States behind Lake Mead, storing of water when full...

, a reservoirReservoirA reservoir , artificial lake or dam is used to store water.Reservoirs may be created in river valleys by the construction of a dam or may be built by excavation in the ground or by conventional construction techniques such as brickwork or cast concrete.The term reservoir may also be used to...

on the Colorado RiverColorado RiverThe Colorado River , is a river in the Southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico, approximately long, draining a part of the arid regions on the western slope of the Rocky Mountains. The watershed of the Colorado River covers in parts of seven U.S. states and two Mexican states...

, was named in his honor. It straddles the border between UtahUtahUtah is a state in the Western United States. It was the 45th state to join the Union, on January 4, 1896. Approximately 80% of Utah's 2,763,885 people live along the Wasatch Front, centering on Salt Lake City. This leaves vast expanses of the state nearly uninhabited, making the population the...

and ArizonaArizonaArizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

. It is the second-largest man-made reservoir in the United States behind Lake MeadLake MeadLake Mead is the largest reservoir in the United States. It is located on the Colorado River about southeast of Las Vegas, Nevada, in the states of Nevada and Arizona. Formed by water impounded by the Hoover Dam, it extends behind the dam, holding approximately of water.-History:The lake was...

. It is part of the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, a popular summer destination. - In Powell's honor, in 1974 the USGS National Center in Reston, VirginiaReston, VirginiaReston is a census-designated place in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States, within the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. The population was 58,404, at the 2010 Census and 56,407 at the 2000 census...

, was dedicated as The John Wesley Powell Federal Building. In addition, the USGS's highest award to persons outside the federal government is named the John Wesley Powell AwardJohn Wesley Powell AwardThe John Wesley Powell Award is a United States Geological Survey honor award that recognizes an individual or group, not employed by the U.S...

.

Beliefs and Ideas

As an ethnologist and early anthropologistAnthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

, Powell was a student of the pioneering anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan. Powell divided human societies into "savagery," "barbarism" and "civilization" based on levels of technology, family and social organization, property relations, and intellectual development. In his view, all societies progressed toward civilization. He was a champion of preservation and conservation. It was his conviction that part of the natural progression of society included a combination of efforts to maximize and make the best use of resources.

Powell is credited with coining the word "acculturation

Acculturation

Acculturation explains the process of cultural and psychological change that results following meeting between cultures. The effects of acculturation can be seen at multiple levels in both interacting cultures. At the group level, acculturation often results in changes to culture, customs, and...

", first using it in an 1880 report by the U.S. Bureau of American Ethnography

Ethnography

Ethnography is a qualitative method aimed to learn and understand cultural phenomena which reflect the knowledge and system of meanings guiding the life of a cultural group...

. In 1883 Powell defined "acculturation" to be the psychological changes induced by cross-cultural imitation.

Powell' s expeditions led to his belief that the arid West was not suitable for agricultural development, except for about 2% of the lands that were near water sources. His Report on the Lands of the Arid Regions of the United States proposed irrigation

Irrigation

Irrigation may be defined as the science of artificial application of water to the land or soil. It is used to assist in the growing of agricultural crops, maintenance of landscapes, and revegetation of disturbed soils in dry areas and during periods of inadequate rainfall...

systems and state boundaries based on watershed

Drainage basin

A drainage basin is an extent or an area of land where surface water from rain and melting snow or ice converges to a single point, usually the exit of the basin, where the waters join another waterbody, such as a river, lake, reservoir, estuary, wetland, sea, or ocean...

areas (to avoid squabbles). For the remaining lands, he proposed conservation and low-density, open grazing.

The railroad companies, who owned vast tracts of lands (183000000 acres (740,575.4 km²)) granted in return for building the lines, did not agree with his opinion. They aggressively lobbied Congress to reject Powell's policy proposals and to encourage farming instead, as they wanted to develop their lands. The politicians agreed and developed policies that encouraged pioneer settlement based on agriculture. They based such policy on a theory developed by Professor Cyrus Thomas

Cyrus Thomas

Cyrus Thomas was a U.S. ethnologist and entomologist prominent in the late 19th century and noted for his studies of the natural history of the American West.-Biography:Thomas was born in Kingsport, Tennessee...

and promoted by Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley was an American newspaper editor, a founder of the Liberal Republican Party, a reformer, a politician, and an outspoken opponent of slavery...

. He suggested that agricultural development of land causes arid lands to generate higher amounts of rain ("rain follows the plow"). At an 1883 irrigation conference, Powell would remark: "Gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply the land." Powell's recommendations for development of the West were largely ignored until after the Dust Bowl

Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl, or the Dirty Thirties, was a period of severe dust storms causing major ecological and agricultural damage to American and Canadian prairie lands from 1930 to 1936...

of the 1920s and 1930s, resulting in untold suffering associated with pioneer subsistence farms that failed due to insufficient rain.

External links

- Biographical sketch (1903) by Frederick S. Dellenbaugh

- http://www.nps.gov/archive/grca/photos/powell/index.htm NPS John Wesley Powell Photograph Index

- John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference at Illinois Wesleyan UniversityIllinois Wesleyan UniversityIllinois Wesleyan University is an independent undergraduate university located in Bloomington, Illinois. Founded in 1850, the central portion of the present campus was acquired in 1854 with the first building erected in 1856...

- John Wesley Powell Collection of Pueblo Pottery at Illinois Wesleyan UniversityIllinois Wesleyan UniversityIllinois Wesleyan University is an independent undergraduate university located in Bloomington, Illinois. Founded in 1850, the central portion of the present campus was acquired in 1854 with the first building erected in 1856...

Ames Library - Powell Museum, Page, ArizonaPage, ArizonaPage is a city in Coconino County, Arizona, United States, near the Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell. According to 2005 Census Bureau estimates, the population of the city is 6,794.-Geography:Page is located at ....

- John Wesley Powell River History Museum, Green River, UtahGreen River, UtahGreen River is a city in Emery County, Utah, United States. The population was 973 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Green River is located at , on the banks of the Green River, after which the city is named. The San Rafael Swell region is to the west of Green River, while Canyonlands National Park...

- "John Wesley Powell" by James M. Aton in the Western Writers Series Digital Editions at Boise State University