History of the Puritans from 1649

Encyclopedia

From 1649 to 1660 Puritan

s in England were allied to the state power held by the military regime, headed by Oliver Cromwell

until his death in 1658. They broke into numerous sects, of which the Presbyterian group comprised most of the clergy, but was deficient in political power since Cromwell's sympathies were with the Independents

. During this period the term "Puritan" becomes largely moot, therefore, in British terms, though the situation in New England

was very different. After the English Restoration

the Savoy Conference

and Uniformity Act 1662 drove most of the Puritan ministers from the Church of England

, and the outlines of the Puritan movement changed over a few decades into the collections of Presbyterian and Congregational churches, operating as they could as Dissenters under changing regimes.

was a period of religious diversity in England. With the creation of the Commonwealth of England

in 1649, government passed to the English Council of State

, a group dominated by Oliver Cromwell, an advocate of religious liberty. In 1650, at Cromwell's behest, the Rump Parliament abolished the Act of Uniformity 1558, meaning that while England now had an officially established church with Presbyterian polity, there was no legal requirement that anyone attend services in the established church.

In 1646, the Long Parliament

had abolished episcopacy in the Church of England

and replaced it with a presbyterian system, and had voted to replace the Book of Common Prayer

with the Directory of Public Worship

. The actual implementation of these reforms in the church proceeded slowly for a number of reasons:

With the abolition of the Act of Uniformity, even the pretense of religious uniformity broke down. Thus, while the Presbyterians were dominant (at least theoretically) within the established church, those who opposed Presbyterianism were in fact free to start conducting themselves in the way they wanted. Separatists, who had previously organized themselves underground, were able to worship openly. For example, as early as 1616, the first English Baptists had organized themselves in secret, under the leadership of Henry Jacob

, John Lothropp, and Henry Jessey

. Now, however, they were less secretive. Other ministers - who favored the congregationalist New England Way - also began setting up their own congregations outside of the established church.

Many sects were also organized during this time. It is not clear that they should be called "Puritan" sects since they placed less emphasis on the Bible

than is characteristic of Puritans, instead insisting on the role of direct contact with the Holy Spirit

. These groups included the Ranters, the Fifth Monarchists

, the Seekers

, the Muggletonians, and - most prominently and most lastingly - the Quakers.

of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland. The Instrument of Government provided that Protestant sects would enjoy religious liberty, although it also provided that England would continue to have a national Church, but did not detail its structure or beliefs, instead leaving Cromwell with wide discretion as to how to order the national church.

Cromwell felt that the Church of England should not have any set doctrinal or liturgical position, and that the only religious uniformity enforced by the state should be to ensure that fundamental Christian principles were respected and to ensure the church remained Protestant. In March 1654, Cromwell issued an Ordinance establishing a Commission of 38 - commonly referred to as the Triers - which would be responsible for ensuring that candidates presented to benefices in the Church of England met this minimum standard. In August, Cromwell issued a second ordinance established board of local commissioners - referred to as the Ejectors - which had the power to remove unfit ministers from their offices. The Ejectors were forbidden from inquiring into a minister's doctrine, and could only expel a minister for neglect of his parish or for "scandalous behaviour" (e.g. adultery, drunkenness, profaning of Sabbath, etc.).

The Puritan movement split over issues of ecclesiology in the course of the Westminster Assembly. In the course of the 1650s, the movement became further split in the course of a number of controversies. With no means to enforce uniformity in the church and with freedom of the press, these disputes were largely played out in pamphlet warfare throughout the decade.

The Puritan movement split over issues of ecclesiology in the course of the Westminster Assembly. In the course of the 1650s, the movement became further split in the course of a number of controversies. With no means to enforce uniformity in the church and with freedom of the press, these disputes were largely played out in pamphlet warfare throughout the decade.

, the pastor of Coggeshall

, Essex

, a man who was a champion of congregationalism

, who had preached to the Long Parliament, and who had published a number of works denouncing Arminianism

, published his work The Death of Death in the Death of Christ. In this work, he denounced the Arminian doctrine of the unlimited atonement

and argued in favour of the doctrine of a limited atonement

. He also denounced the spread of Amyraldism

in England, a position most associated with John Davenant

, Samuel Ward

and their followers.

In 1649, Richard Baxter

, the minister of Kidderminster

, Worcestershire

and who served as chaplain

to Colonel Edward Whalley

's regiment, published a reply to Owen, entitled Aphorisms of Justification. He argued that the doctrine of unlimited atonement

was more faithful to the words of scripture

. He invoked the authority of dozens of the Reformers

, including John Calvin

, in support of his position.

In the course of the 1650s, Owen and Baxter engaged in a series of replies and counter-replies on the topic. At the same time, both men gained followers for their positions. John Owen preached to the Long Parliament the day after the execution of Charles I, and then accompanied Oliver Cromwell

In the course of the 1650s, Owen and Baxter engaged in a series of replies and counter-replies on the topic. At the same time, both men gained followers for their positions. John Owen preached to the Long Parliament the day after the execution of Charles I, and then accompanied Oliver Cromwell

to Ireland. Cromwell charged Owen with reforming Trinity College, Dublin

. In 1651, after the Presbyterian Vice-Chancellor

of the University of Oxford

, Edward Reynolds

, refused to take the Engagement

, Cromwell appointed Owen as vice-chancellor in his stead. From that post, Owen became the most prominent Independent

churchman of the 1650s.

Baxter also gained a following in the 1650s, publishing prolifically after his return to Kidderminster. Two of his books - The Saints' Everlasting Rest (1650) and The Reformed Pastor (1656) - have been regarded by subsequent generations as Puritan classics. Many clergymen came to see Baxter as the leader of the Presbyterians, the largest party of Puritans, in the course of the 1650s.

, an anti-trinitarian position, had made a few in-roads into England in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Adherents of this position had been brutally oppressed, with a number of high-profile executions, including that of Francis Kett

in 1589, and Bartholomew Legate

and Edward Wightman

in 1612, after they in 1609 published a Latin version of the Racovian Catechism

.

The most prominent Socinian of the 1650s was John Biddle

, often known as the "Father of English Unitarianism

." Biddle was imprisoned in 1645 and 1646 for publicizing his denials of the Trinity

. After being defended in the Long Parliament

by Henry Vane the Younger

, Biddle was released in 1648. In 1652, he was arrested again after he published an anti-trinitarian catechism. John Owen produced several pieces denouncing Biddle's views. However, Cromwell, true to his principle of religious liberty, intervened to ensure that Biddle was not executed, but instead sent to exile on the Isles of Scilly

in 1652.

. Charles II's most loyal followers - those who had followed him into exile on the continent, like Sir Edward Hyde

- had fought the English Civil War largely in defense of episcopacy and insisted that episcopacy be restored in the Church of England. Nevertheless, in the Declaration of Breda

, issued in April 1660, a month before Charles II's return to England, Charles II proclaimed that while he intended to restore the Church of England, he would also pursue a policy of religious toleration

for non-adherents of the Church of England. Charles II named the only living pre-Civil War bishop William Juxon

as Archbishop of Canterbury

in 1660, but it was widely understood that because of Juxon's age, he would likely die soon and be replaced by Gilbert Sheldon

, who, for the time being, became Bishop of London

. In a show of goodwill, one of the chief Presbyterians, Edward Reynolds

, was named Bishop of Norwich

and chaplain to the king.

Shortly after Charles II's return to England, in early 1661, Fifth Monarchists

Vavasor Powell

and Thomas Venner

attempted a coup against Charles II. Thus, elections were held for the Cavalier Parliament

in a heated atmosphere of anxiety about a further Puritan uprising.

Nevertheless, Charles II had hoped that the Book of Common Prayer

could be reformed in a way that was acceptable to the majority of the Presbyterians, so that when religious uniformity was restored by law, the largest number of Puritans possible could be incorporated inside the Church of England. At the April 1661 Savoy Conference

, held at Gilbert Sheldon

's chambers at Savoy Hospital, twelve bishops and twelve representatives of the Presbyterian party (Edward Reynolds

, Anthony Tuckney

, John Conant

, William Spurstowe

, John Wallis, Thomas Manton

, Edmund Calamy

, Richard Baxter

, Arthur Jackson

, Thomas Case

, Samuel Clarke

, and Matthew Newcomen

) met to discuss Presbyterian proposals for reforming the Book of Common Prayer drawn up by Richard Baxter. Baxter's proposed liturgy was largely rejected at the Conference.

When the Cavalier Parliament met in May 1661, its first action, largely a reaction to the Fifth Monarchist uprising, was to pass the Corporation Act of 1661

, which barred anyone who had not received communion in the Church of England in the past twelve months from holding office in a city or corporation. It also required officeholders to swear the Oath of Allegiance

and Oath of Supremacy

, to swear belief in the Doctrine of Passive Obedience

, and to renounce the Covenant

.

In 1662, the Cavalier Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity of 1662

In 1662, the Cavalier Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity of 1662

, restoring the Book of Common Prayer

as the official liturgy. The Act of Uniformity prescribed that any minister who refused to conform to the Book of Common Prayer by St. Bartholomew's Day 1662 would be ejected from the Church of England. This date became known as Black Bartholomew's Day, among dissenters, a reference to the fact that it occurred on the same day as the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

of 1572.

The majority of ministers who had served in Cromwell's state church conformed to the Book of Common Prayer. Members of Cromwell's state church who chose to conform in 1662 were often labeled Latitudinarians by contemporaries - this group includes John Tillotson

, Simon Patrick

, Thomas Tenison

, William Lloyd, Joseph Glanvill

, and Edward Fowler

. The Latitudinarians formed the basis of what would later become the Low church

wing of the Church of England. The Puritan movement had become particularly fractured in the course of the 1640s and 1650s, and with the decision of the Latitudinarians to conform in 1662, it became even further fractured.

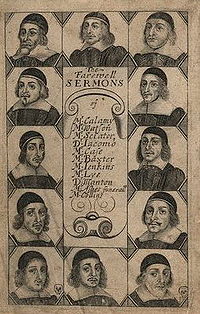

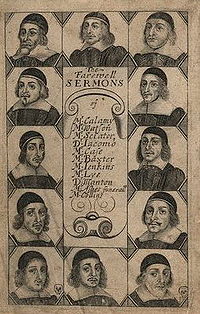

Around two thousand Puritan ministers resigned from their positions as Church of England clergy as a consequence. This group included Richard Baxter

, Edmund Calamy the Elder

, Simeon Ashe

, Thomas Case

, William Jenkyn

, Thomas Manton

, William Sclater

, and Thomas Watson

. After 1662, the term "Puritan" was generally supplanted by "Nonconformist" or "Dissenter" to describe those Puritans who had refused to conform in 1662.

denominations

. The Cavalier Parliament responded hostilely to the continued influence of the non-conforming ministers. In 1664, it passed the Conventicle Act

banning religious assemblies of more than five people outside of the Church of England. In 1665, it passed the Five Mile Act

, forbidding ejected ministers from living within five miles of a parish from which they had been banned, unless they swore an oath never to resist the king, or attempt to alter the government of Church or State. Under the penal laws forbidding religious dissent (generally known to history as the Clarendon Code), many ministers were imprisoned in the latter half of the 1660s. One of the most notable victims of the penal laws during this period (though he was not himself an ejected minister) was John Bunyan

,a Baptist, who was imprisoned from 1660 to 1672.

At the same time that the Cavalier Parliament was ratcheting up the legal penalties against religious dissent, there were various attempts from the side of government and bishops, to establish a basis for "comprehension", a set of circumstances under which some dissenting ministers could return to the Church of England. These schemes for comprehension would have driven a wedge between Presbyterians and the group of Independents; but the discussions that took place between Latitudinarian figures in the Church and leaders such as Baxter and Manton never bridged the gap between Dissenters and the "high church" party in the Church of England, and comprehension ultimately proved impossible to achieve.

with Louis XIV of France

. In this treaty he committed to securing religious toleration for the Roman Catholic recusants in England. In March 1672, Charles issued his Royal Declaration of Indulgence

, which suspended the penal laws against the dissenters and eased restrictions on the private practice of Catholicism. Many imprisoned dissenters (including John Bunyan) were released from prison in response to the Royal Declaration of Indulgence.

The Cavalier Parliament reacted hostilely to the Royal Declaration of Indulgence. Supporters of the high church party in the Church of England resented the easing of the penal laws, while many across the political nation suspected that Charles II was plotting to restore Catholicism to England. The Cavalier Parliament's hostility forced Charles to withdraw the declaration of indulgence, and the penal laws were again enforceable. In 1673, Parliament passed the first Test Act

, requiring all officeholders in England to abjure the doctrine of transubstantiation

(thus ensuring no Catholics could hold office in England).

and Evangelical trends in the Church of England

. Divisions between Presbyterian and Congregationalist groups in London became clear in the 1690s, and with the Congregationalists following the trend of the older Independents, a split became perpetuated. The Salters' Hall conference of 1719 was a landmark, after which many of the congregations went their own way in theology. In Europe, in the 17th and 18th centuries, a movement within Lutheranism parallel to puritan ideology (which was mostly of a Calvinist orientation) became a strong religious force known as pietism

. In the USA, the Puritan settlement of New England

was a major influence on American Protestantism.

With the start of the English Civil War in 1642, fewer settlers to New England were Puritans. The period fo 1642 to 1659 represented a period of peaceful dominance in English life by the formerly discriminated Puritan population. Consequently, most felt no need to settle in the American colonies. Very few immigrants to Virginia and other early colonies, in any case, were Puritans, with Virginia being a repository for more middle class and "royalist" oriented settlers leaving England following their loss of power during the English Commonwealth. Many migrants to New England who had looked for greater religious freedom found the Puritan theocracy

to be repressive, examples being Roger Williams

, Stephen Bachiler

, Anne Hutchinson

, and Mary Dyer

. Puritan populations in New England, continued to grow, with many large and prosperous Puritan families. (See Estimated Population 1620–1780: Immigration to the USA.)

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

s in England were allied to the state power held by the military regime, headed by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

until his death in 1658. They broke into numerous sects, of which the Presbyterian group comprised most of the clergy, but was deficient in political power since Cromwell's sympathies were with the Independents

Independent (religion)

In English church history, Independents advocated local congregational control of religious and church matters, without any wider geographical hierarchy, either ecclesiastical or political...

. During this period the term "Puritan" becomes largely moot, therefore, in British terms, though the situation in New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

was very different. After the English Restoration

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

the Savoy Conference

Savoy Conference

The Savoy Conference of 1661 was a significant liturgical discussion that took place, after the Restoration of Charles II, in an attempt to effect a reconciliation within the Church of England.-Proceedings:...

and Uniformity Act 1662 drove most of the Puritan ministers from the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

, and the outlines of the Puritan movement changed over a few decades into the collections of Presbyterian and Congregational churches, operating as they could as Dissenters under changing regimes.

Failure of the Presbyterian church, 1649–1654

The English InterregnumEnglish Interregnum

The English Interregnum was the period of parliamentary and military rule by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell under the Commonwealth of England after the English Civil War...

was a period of religious diversity in England. With the creation of the Commonwealth of England

Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the republic which ruled first England, and then Ireland and Scotland from 1649 to 1660. Between 1653–1659 it was known as the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland...

in 1649, government passed to the English Council of State

English Council of State

The English Council of State, later also known as the Protector's Privy Council, was first appointed by the Rump Parliament on 14 February 1649 after the execution of King Charles I....

, a group dominated by Oliver Cromwell, an advocate of religious liberty. In 1650, at Cromwell's behest, the Rump Parliament abolished the Act of Uniformity 1558, meaning that while England now had an officially established church with Presbyterian polity, there was no legal requirement that anyone attend services in the established church.

In 1646, the Long Parliament

Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was made on 3 November 1640, following the Bishops' Wars. It received its name from the fact that through an Act of Parliament, it could only be dissolved with the agreement of the members, and those members did not agree to its dissolution until after the English Civil War and...

had abolished episcopacy in the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

and replaced it with a presbyterian system, and had voted to replace the Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

with the Directory of Public Worship

Directory of Public Worship

The Directory for Public Worship was a manual of directions for worship approved by an ordinance of Parliament early in 1645 to replace the Book of Common Prayer .-Origins:The movement against the Book of Common...

. The actual implementation of these reforms in the church proceeded slowly for a number of reasons:

- In many localities - especially those areas which had been Royalist during the Civil Wars and which had low numbers of Puritans, both the bishops and the Book of Common Prayer were popular, and ministers as well as their congregations simply continued to conduct worship in their ordinary way.

- IndependentsIndependent (religion)In English church history, Independents advocated local congregational control of religious and church matters, without any wider geographical hierarchy, either ecclesiastical or political...

opposed the scheme, and started conducting themselves as gathered churches. - Clergymen who favored presbyterianism nevertheless disliked the Long Parliament's ordinance because it included an Erastian element in the office of "commissioner". Some were thus less than enthusiastic about implementing the Long Parliament's scheme.

- Since the office of bishop had been abolished in the church, with no substitute, there was no one to enforce the new presbyterianism scheme on the church, so the combination of opposition and apathy meant that little was done.

With the abolition of the Act of Uniformity, even the pretense of religious uniformity broke down. Thus, while the Presbyterians were dominant (at least theoretically) within the established church, those who opposed Presbyterianism were in fact free to start conducting themselves in the way they wanted. Separatists, who had previously organized themselves underground, were able to worship openly. For example, as early as 1616, the first English Baptists had organized themselves in secret, under the leadership of Henry Jacob

Henry Jacob

Henry Jacob was an English clergyman of Calvinist views, who founded a separatist congregation associated with the Brownists.-Life:...

, John Lothropp, and Henry Jessey

Henry Jessey

Henry Jessey or Jacie was one of many English Dissenters. He was a founding member of the Puritan religious sect, the Jacobites. Jessey was considered a Hebrew and a rabbinical scholar.-Life:...

. Now, however, they were less secretive. Other ministers - who favored the congregationalist New England Way - also began setting up their own congregations outside of the established church.

Many sects were also organized during this time. It is not clear that they should be called "Puritan" sects since they placed less emphasis on the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

than is characteristic of Puritans, instead insisting on the role of direct contact with the Holy Spirit

Holy Spirit

Holy Spirit is a term introduced in English translations of the Hebrew Bible, but understood differently in the main Abrahamic religions.While the general concept of a "Spirit" that permeates the cosmos has been used in various religions Holy Spirit is a term introduced in English translations of...

. These groups included the Ranters, the Fifth Monarchists

Fifth Monarchists

The Fifth Monarchists or Fifth Monarchy Men were active from 1649 to 1661 during the Interregnum, following the English Civil Wars of the 17th century. They took their name from a prophecy in the Book of Daniel that four ancient monarchies would precede Christ's return...

, the Seekers

Seekers

The Seekers, or Legatine-Arians as they were sometimes known, were a Protestant dissenting group that emerged around the 1620s, probably inspired by the preaching of three brothers – Walter, Thomas, and Bartholomew Legate. Arguably, they are best thought of as forerunners of the Quakers, with whom...

, the Muggletonians, and - most prominently and most lastingly - the Quakers.

Cromwellian State Church, 1654–1660

In 1653, the Instrument of Government saw Oliver Cromwell declared Lord ProtectorLord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland. The Instrument of Government provided that Protestant sects would enjoy religious liberty, although it also provided that England would continue to have a national Church, but did not detail its structure or beliefs, instead leaving Cromwell with wide discretion as to how to order the national church.

Cromwell felt that the Church of England should not have any set doctrinal or liturgical position, and that the only religious uniformity enforced by the state should be to ensure that fundamental Christian principles were respected and to ensure the church remained Protestant. In March 1654, Cromwell issued an Ordinance establishing a Commission of 38 - commonly referred to as the Triers - which would be responsible for ensuring that candidates presented to benefices in the Church of England met this minimum standard. In August, Cromwell issued a second ordinance established board of local commissioners - referred to as the Ejectors - which had the power to remove unfit ministers from their offices. The Ejectors were forbidden from inquiring into a minister's doctrine, and could only expel a minister for neglect of his parish or for "scandalous behaviour" (e.g. adultery, drunkenness, profaning of Sabbath, etc.).

Religious controversies of the Interregnum

Owen—Baxter Debate over the nature of Justification

In 1647, John OwenJohn Owen (theologian)

John Owen was an English Nonconformist church leader, theologian, and academic administrator at the University of Oxford.-Early life:...

, the pastor of Coggeshall

Coggeshall

Coggeshall is a small market town of 3,919 residents in Essex, England, situated between Colchester and Braintree on the Roman road of Stane Street , and intersected by the River Blackwater. It is known for its almost 300 listed buildings and formerly extensive antique trade...

, Essex

Essex

Essex is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East region of England, and one of the home counties. It is located to the northeast of Greater London. It borders with Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent to the South and London to the south west...

, a man who was a champion of congregationalism

Congregationalist polity

Congregationalist polity, often known as congregationalism, is a system of church governance in which every local church congregation is independent, ecclesiastically sovereign, or "autonomous"...

, who had preached to the Long Parliament, and who had published a number of works denouncing Arminianism

Arminianism

Arminianism is a school of soteriological thought within Protestant Christianity based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius and his historic followers, the Remonstrants...

, published his work The Death of Death in the Death of Christ. In this work, he denounced the Arminian doctrine of the unlimited atonement

Unlimited atonement

Unlimited atonement is the majority doctrine in Protestant Christianity that is normally associated with Non-Calvinist and persons who are up to "four-point" Calvinist Christians...

and argued in favour of the doctrine of a limited atonement

Limited atonement

Limited atonement is a doctrine in Christian theology which is particularly associated with the Reformed tradition and is one of the five points of Calvinism...

. He also denounced the spread of Amyraldism

Amyraldism

Amyraldism primarily refers to a modified form of Calvinist theology...

in England, a position most associated with John Davenant

John Davenant

John Davenant was an English academic and bishop of Salisbury from 1621.-Life:He was educated at Queens’ College, Cambridge, elected a fellow there in 1597, and was its President from 1614 to 1621...

, Samuel Ward

Samuel Ward (scholar)

Samuel Ward was an English academic and a master at the University of Cambridge.-Life:He was born at Bishop Middleham, county Durham. He was a scholar of Christ's College, Cambridge, where in 1592 he was admitted B.A. In 1595 he was elected to a fellowship at Emmanuel, and in the following year...

and their followers.

In 1649, Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter was an English Puritan church leader, poet, hymn-writer, theologian, and controversialist. Dean Stanley called him "the chief of English Protestant Schoolmen". After some false starts, he made his reputation by his ministry at Kidderminster, and at around the same time began a long...

, the minister of Kidderminster

Kidderminster

Kidderminster is a town, in the Wyre Forest district of Worcestershire, England. It is located approximately seventeen miles south-west of Birmingham city centre and approximately fifteen miles north of Worcester city centre. The 2001 census recorded a population of 55,182 in the town...

, Worcestershire

Worcestershire

Worcestershire is a non-metropolitan county, established in antiquity, located in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes it is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three counties that comprise the "Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire" NUTS 2 region...

and who served as chaplain

Chaplain

Traditionally, a chaplain is a minister in a specialized setting such as a priest, pastor, rabbi, or imam or lay representative of a religion attached to a secular institution such as a hospital, prison, military unit, police department, university, or private chapel...

to Colonel Edward Whalley

Edward Whalley

Edward Whalley was an English military leader during the English Civil War, and was one of the regicides who signed the death warrant of King Charles I of England.-Early career:The exact dates of his birth and death are unknown...

's regiment, published a reply to Owen, entitled Aphorisms of Justification. He argued that the doctrine of unlimited atonement

Unlimited atonement

Unlimited atonement is the majority doctrine in Protestant Christianity that is normally associated with Non-Calvinist and persons who are up to "four-point" Calvinist Christians...

was more faithful to the words of scripture

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

. He invoked the authority of dozens of the Reformers

Protestant Reformers

Protestant Reformers were those theologians, churchmen, and statesmen whose careers, works, and actions brought about the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century...

, including John Calvin

John Calvin

John Calvin was an influential French theologian and pastor during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism. Originally trained as a humanist lawyer, he broke from the Roman Catholic Church around 1530...

, in support of his position.

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

to Ireland. Cromwell charged Owen with reforming Trinity College, Dublin

Trinity College, Dublin

Trinity College, Dublin , formally known as the College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, was founded in 1592 by letters patent from Queen Elizabeth I as the "mother of a university", Extracts from Letters Patent of Elizabeth I, 1592: "...we...found and...

. In 1651, after the Presbyterian Vice-Chancellor

Chancellor (education)

A chancellor or vice-chancellor is the chief executive of a university. Other titles are sometimes used, such as president or rector....

of the University of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

, Edward Reynolds

Edward Reynolds

Edward Reynolds was a bishop of Norwich in the Church of England and an author.He was born in Holyrood parish Southampton, the son of Augustine Reynolds, one of the customers of the city, and his wife, Bridget....

, refused to take the Engagement

Engagement controversy

The Engagement Controversy was a debate in England from 1649-1652 regarding loyalty to the new regime after the execution of Charles I. During this period hundreds of pamphlets were published in England supporting 'engagement' to the new regime or denying the right of English citizens to shift...

, Cromwell appointed Owen as vice-chancellor in his stead. From that post, Owen became the most prominent Independent

Independent (religion)

In English church history, Independents advocated local congregational control of religious and church matters, without any wider geographical hierarchy, either ecclesiastical or political...

churchman of the 1650s.

Baxter also gained a following in the 1650s, publishing prolifically after his return to Kidderminster. Two of his books - The Saints' Everlasting Rest (1650) and The Reformed Pastor (1656) - have been regarded by subsequent generations as Puritan classics. Many clergymen came to see Baxter as the leader of the Presbyterians, the largest party of Puritans, in the course of the 1650s.

Socinian controversy

SocinianismSocinianism

Socinianism is a system of Christian doctrine named for Fausto Sozzini , which was developed among the Polish Brethren in the Minor Reformed Church of Poland during the 15th and 16th centuries and embraced also by the Unitarian Church of Transylvania during the same period...

, an anti-trinitarian position, had made a few in-roads into England in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Adherents of this position had been brutally oppressed, with a number of high-profile executions, including that of Francis Kett

Francis Kett

-Life:Kett was born in Wymondham, Norfolk, the son of Thomas and Agnes Kett, and the nephew of the rebel Robert Kett, the main instigator of Kett's Rebellion....

in 1589, and Bartholomew Legate

Bartholomew Legate

Bartholomew Legate was an English anti-Trinitarian martyr.Legate was born in Essex and became a dealer in cloth. In the 1590s, Bartholomew and his two brothers, Walter and Thomas, began preaching around the London area. Their unorthodox message rejected the Roman Catholic Church, the Church of...

and Edward Wightman

Edward Wightman

Edward Wightman was an English radical Anabaptist, executed at Lichfield for his activities promoting himself as the divine Paraclete and Savior of the world...

in 1612, after they in 1609 published a Latin version of the Racovian Catechism

Racovian Catechism

The Racovian Catechism is a nontrinitarian statement of faith from the 16th century. The title Racovian comes from the publishers, the Polish Brethren, who had founded a sizeable town in Raków, Kielce County, where the Racovian Academy and printing press was founded by Jakub Sienieński in...

.

The most prominent Socinian of the 1650s was John Biddle

John Biddle (Unitarian)

John Biddle or Bidle was an influential English nontrinitarian, and Unitarian. He is often called "the Father of English Unitarianism".- Life :...

, often known as the "Father of English Unitarianism

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

." Biddle was imprisoned in 1645 and 1646 for publicizing his denials of the Trinity

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity defines God as three divine persons : the Father, the Son , and the Holy Spirit. The three persons are distinct yet coexist in unity, and are co-equal, co-eternal and consubstantial . Put another way, the three persons of the Trinity are of one being...

. After being defended in the Long Parliament

Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was made on 3 November 1640, following the Bishops' Wars. It received its name from the fact that through an Act of Parliament, it could only be dissolved with the agreement of the members, and those members did not agree to its dissolution until after the English Civil War and...

by Henry Vane the Younger

Henry Vane the Younger

Sir Henry Vane , son of Henry Vane the Elder , was an English politician, statesman, and colonial governor...

, Biddle was released in 1648. In 1652, he was arrested again after he published an anti-trinitarian catechism. John Owen produced several pieces denouncing Biddle's views. However, Cromwell, true to his principle of religious liberty, intervened to ensure that Biddle was not executed, but instead sent to exile on the Isles of Scilly

Isles of Scilly

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago off the southwestern tip of the Cornish peninsula of Great Britain. The islands have had a unitary authority council since 1890, and are separate from the Cornwall unitary authority, but some services are combined with Cornwall and the islands are still part...

in 1652.

Puritans and the Restoration, 1660

The largest Puritan faction - the Presbyterians - had been deeply dissatisfied with the state of the church under Cromwell. They wanted to restore religious uniformity throughout England and they believed that only a restoration of the English monarchy could achieve this and suppress the sectaries. Most Presbyterians were therefore supportive of the Restoration of Charles IICharles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

. Charles II's most loyal followers - those who had followed him into exile on the continent, like Sir Edward Hyde

Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon

Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon was an English historian and statesman, and grandfather of two English monarchs, Mary II and Queen Anne.-Early life:...

- had fought the English Civil War largely in defense of episcopacy and insisted that episcopacy be restored in the Church of England. Nevertheless, in the Declaration of Breda

Declaration of Breda

The Declaration of Breda was a proclamation by Charles II of England in which he promised a general pardon for crimes committed during the English Civil War and the Interregnum for all those who recognised Charles as the lawful king; the retention by the current owners of property purchased during...

, issued in April 1660, a month before Charles II's return to England, Charles II proclaimed that while he intended to restore the Church of England, he would also pursue a policy of religious toleration

Religious toleration

Toleration is "the practice of deliberately allowing or permitting a thing of which one disapproves. One can meaningfully speak of tolerating, ie of allowing or permitting, only if one is in a position to disallow”. It has also been defined as "to bear or endure" or "to nourish, sustain or preserve"...

for non-adherents of the Church of England. Charles II named the only living pre-Civil War bishop William Juxon

William Juxon

William Juxon was an English churchman, Bishop of London from 1633 to 1649 and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1660 until his death.-Life:...

as Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

in 1660, but it was widely understood that because of Juxon's age, he would likely die soon and be replaced by Gilbert Sheldon

Gilbert Sheldon

Gilbert Sheldon was an English Archbishop of Canterbury.-Early life:He was born in Stanton, Staffordshire in the parish of Ellastone, on 19 July 1598, the youngest son of Roger Sheldon; his father worked for Gilbert Talbot, 7th Earl of Shrewsbury. He was educated at Trinity College, Oxford; he...

, who, for the time being, became Bishop of London

Bishop of London

The Bishop of London is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury.The diocese covers 458 km² of 17 boroughs of Greater London north of the River Thames and a small part of the County of Surrey...

. In a show of goodwill, one of the chief Presbyterians, Edward Reynolds

Edward Reynolds

Edward Reynolds was a bishop of Norwich in the Church of England and an author.He was born in Holyrood parish Southampton, the son of Augustine Reynolds, one of the customers of the city, and his wife, Bridget....

, was named Bishop of Norwich

Bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury.The diocese covers most of the County of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. The see is in the City of Norwich where the seat is located at the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided...

and chaplain to the king.

Shortly after Charles II's return to England, in early 1661, Fifth Monarchists

Fifth Monarchists

The Fifth Monarchists or Fifth Monarchy Men were active from 1649 to 1661 during the Interregnum, following the English Civil Wars of the 17th century. They took their name from a prophecy in the Book of Daniel that four ancient monarchies would precede Christ's return...

Vavasor Powell

Vavasor Powell

Vavasor Powell was a Welsh Nonconformist Puritan preacher, evangelist, church leader and writer.-Life:He was born in Knucklas, Radnorshire and was educated at Jesus College, Oxford...

and Thomas Venner

Thomas Venner

Thomas Venner was a cooper and rebel who became the last leader of the Fifth Monarchy Men, who tried unsuccessfully to overthrow Oliver Cromwell in 1657, and subsequently led a coup in London against the newly-restored government of Charles II...

attempted a coup against Charles II. Thus, elections were held for the Cavalier Parliament

Cavalier Parliament

The Cavalier Parliament of England lasted from 8 May 1661 until 24 January 1679. It was the longest English Parliament, enduring for nearly 18 years of the quarter century reign of Charles II of England...

in a heated atmosphere of anxiety about a further Puritan uprising.

Nevertheless, Charles II had hoped that the Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

could be reformed in a way that was acceptable to the majority of the Presbyterians, so that when religious uniformity was restored by law, the largest number of Puritans possible could be incorporated inside the Church of England. At the April 1661 Savoy Conference

Savoy Conference

The Savoy Conference of 1661 was a significant liturgical discussion that took place, after the Restoration of Charles II, in an attempt to effect a reconciliation within the Church of England.-Proceedings:...

, held at Gilbert Sheldon

Gilbert Sheldon

Gilbert Sheldon was an English Archbishop of Canterbury.-Early life:He was born in Stanton, Staffordshire in the parish of Ellastone, on 19 July 1598, the youngest son of Roger Sheldon; his father worked for Gilbert Talbot, 7th Earl of Shrewsbury. He was educated at Trinity College, Oxford; he...

's chambers at Savoy Hospital, twelve bishops and twelve representatives of the Presbyterian party (Edward Reynolds

Edward Reynolds

Edward Reynolds was a bishop of Norwich in the Church of England and an author.He was born in Holyrood parish Southampton, the son of Augustine Reynolds, one of the customers of the city, and his wife, Bridget....

, Anthony Tuckney

Anthony Tuckney

Anthony Tuckney was an English Puritan theologian and scholar.-Life:Anthony Tuckney was educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and a fellow there from 1619 to 1630...

, John Conant

John Conant

Rev. John Conant D.D. was an English clergyman, theologian, and Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University.-Life:John Conant was born at Yettington, Bicton, in southeast Devon, England, the eldest son of Robert Conant, son of Richard Conant and his wife, Elizabeth Morris...

, William Spurstowe

William Spurstowe

William Spurstowe was an English clergyman, theologian, and member of the Westminster Assembly. He was one of the Smectymnuus group of Presbyterian clergy, supplying the final WS of the acronym.-Life:...

, John Wallis, Thomas Manton

Thomas Manton

Thomas Manton was an English Puritan clergyman.-Life:Thomas Manton was baptized March 31, 1620 at Lydeard St Lawrence, Somerset, a remote southwestern portion of England. His grammar school education was possibly at Blundell's School, in Tiverton, Devon...

, Edmund Calamy

Edmund Calamy the Elder

Edmund Calamy was an English Presbyterian church leader and divine. Known as "the elder", he was the first of four generations of nonconformist ministers bearing the same name.-Early life:...

, Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter was an English Puritan church leader, poet, hymn-writer, theologian, and controversialist. Dean Stanley called him "the chief of English Protestant Schoolmen". After some false starts, he made his reputation by his ministry at Kidderminster, and at around the same time began a long...

, Arthur Jackson

Arthur Jackson (minister)

Arthur Jackson was an English clergyman of strong Presbyterian and royalist views. He was imprisoned in 1651 for suspected complicity in the ‘presbyterian plot’ of Christopher Love, and ejected after the Act of Uniformity 1662.-Life:...

, Thomas Case

Thomas Case

Thomas Case was an English clergyman of Presbyterian beliefs, member of the Westminster Assembly where he was one of the strongest advocates of theocracy, and sympathizer with the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy.-Life:...

, Samuel Clarke

Samuel Clarke

thumb|right|200px|Samuel ClarkeSamuel Clarke was an English philosopher and Anglican clergyman.-Early life and studies:...

, and Matthew Newcomen

Matthew Newcomen

Matthew Newcomen was an English nonconformist churchman.His exact date of birth is unknown. He was educated at St John's College, Cambridge . In 1636 he became lecturer at Dedham in Essex, and led the church reform party in that county. He assisted Edmund Calamy the Elder in writing Smectymnuus ,...

) met to discuss Presbyterian proposals for reforming the Book of Common Prayer drawn up by Richard Baxter. Baxter's proposed liturgy was largely rejected at the Conference.

When the Cavalier Parliament met in May 1661, its first action, largely a reaction to the Fifth Monarchist uprising, was to pass the Corporation Act of 1661

Corporation Act 1661

The Corporation Act of 1661 is an Act of the Parliament of England . It belongs to the general category of test acts, designed for the express purpose of restricting public offices in England to members of the Church of England....

, which barred anyone who had not received communion in the Church of England in the past twelve months from holding office in a city or corporation. It also required officeholders to swear the Oath of Allegiance

Oath of allegiance

An oath of allegiance is an oath whereby a subject or citizen acknowledges a duty of allegiance and swears loyalty to monarch or country. In republics, modern oaths specify allegiance to the country's constitution. For example, officials in the United States, a republic, take an oath of office that...

and Oath of Supremacy

Oath of Supremacy

The Oath of Supremacy, originally imposed by King Henry VIII of England through the Act of Supremacy 1534, but repealed by his daughter, Queen Mary I of England and reinstated under Mary's sister, Queen Elizabeth I of England under the Act of Supremacy 1559, provided for any person taking public or...

, to swear belief in the Doctrine of Passive Obedience

Passive obedience

Passive obedience is a religious and political doctrine advocating the absolute supremacy of the Crown and the treatment of any dissent as sinful and unlawful...

, and to renounce the Covenant

Solemn League and Covenant

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians. It was agreed to in 1643, during the First English Civil War....

.

The Great Ejection, 1662

Act of Uniformity 1662

The Act of Uniformity was an Act of the Parliament of England, 13&14 Ch.2 c. 4 ,The '16 Charles II c. 2' nomenclature is reference to the statute book of the numbered year of the reign of the named King in the stated chapter...

, restoring the Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

as the official liturgy. The Act of Uniformity prescribed that any minister who refused to conform to the Book of Common Prayer by St. Bartholomew's Day 1662 would be ejected from the Church of England. This date became known as Black Bartholomew's Day, among dissenters, a reference to the fact that it occurred on the same day as the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

St. Bartholomew's Day massacre

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations, followed by a wave of Roman Catholic mob violence, both directed against the Huguenots , during the French Wars of Religion...

of 1572.

The majority of ministers who had served in Cromwell's state church conformed to the Book of Common Prayer. Members of Cromwell's state church who chose to conform in 1662 were often labeled Latitudinarians by contemporaries - this group includes John Tillotson

John Tillotson

John Tillotson was an Archbishop of Canterbury .-Curate and rector:Tillotson was the son of a Puritan clothier at Haughend, Sowerby, Yorkshire. He entered as a pensioner of Clare Hall, Cambridge, in 1647, graduated in 1650 and was made fellow of his college in 1651...

, Simon Patrick

Simon Patrick

Simon Patrick was an English theologian and bishop.-Life:He was born at Gainsborough, Lincolnshire, on 8 September 1626, and attended Boston Grammar School. He entered Queens College, Cambridge, in 1644, and after taking orders in 1651 became successively chaplain to Sir Walter St. John and vicar...

, Thomas Tenison

Thomas Tenison

Thomas Tenison was an English church leader, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1694 until his death. During his primacy, he crowned two British monarchs.-Life:...

, William Lloyd, Joseph Glanvill

Joseph Glanvill

Joseph Glanvill was an English writer, philosopher, and clergyman. Not himself a scientist, he has been called "the most skillful apologist of the virtuosi", or in other words the leading propagandist for the approach of the English natural philosophers of the later 17th century.-Life:He was...

, and Edward Fowler

Edward Fowler

Edward Fower was an English churchman, Bishop of Gloucester from 1691 until his death.- Early life and education :He was born at Westerleigh, Gloucestershire, and was educated at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, later moving to Trinity College, Cambridge.- Writings :Fower was suspected of Pelagian...

. The Latitudinarians formed the basis of what would later become the Low church

Low church

Low church is a term of distinction in the Church of England or other Anglican churches initially designed to be pejorative. During the series of doctrinal and ecclesiastic challenges to the established church in the 16th and 17th centuries, commentators and others began to refer to those groups...

wing of the Church of England. The Puritan movement had become particularly fractured in the course of the 1640s and 1650s, and with the decision of the Latitudinarians to conform in 1662, it became even further fractured.

Around two thousand Puritan ministers resigned from their positions as Church of England clergy as a consequence. This group included Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter was an English Puritan church leader, poet, hymn-writer, theologian, and controversialist. Dean Stanley called him "the chief of English Protestant Schoolmen". After some false starts, he made his reputation by his ministry at Kidderminster, and at around the same time began a long...

, Edmund Calamy the Elder

Edmund Calamy the Elder

Edmund Calamy was an English Presbyterian church leader and divine. Known as "the elder", he was the first of four generations of nonconformist ministers bearing the same name.-Early life:...

, Simeon Ashe

Simeon Ashe

Simeon Ashe or Ash was an English nonconformist clergyman, a member of the Westminster Assembly and chaplain to the Parliamentary leader Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester.-Life:He was educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge...

, Thomas Case

Thomas Case

Thomas Case was an English clergyman of Presbyterian beliefs, member of the Westminster Assembly where he was one of the strongest advocates of theocracy, and sympathizer with the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy.-Life:...

, William Jenkyn

William Jenkyn

William Jenkyn was an English clergyman, imprisoned during the Interregnum for his part in the ‘presbyterian plot’ of Christopher Love, ejected minister in 1662, and imprisoned at the end of his life for nonconformity.-Life:...

, Thomas Manton

Thomas Manton

Thomas Manton was an English Puritan clergyman.-Life:Thomas Manton was baptized March 31, 1620 at Lydeard St Lawrence, Somerset, a remote southwestern portion of England. His grammar school education was possibly at Blundell's School, in Tiverton, Devon...

, William Sclater

William Sclater

-Life:He was second son of Anthony Sclater, who is said to have held the benefice of Leighton Buzzard in Bedfordshire for fifty years, and to have died in 1620, aged 100. William Sclater was born at Leighton in October 1575. A king's scholar at Eton College, he was admitted scholar of King's...

, and Thomas Watson

Thomas Watson (Puritan)

Thomas Watson was an English, non-conformist, Puritan preacher and author.He was educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he was noted for remarkably intense study. In 1646 he commenced a sixteen year pastorate at St. Stephen's, Walbrook...

. After 1662, the term "Puritan" was generally supplanted by "Nonconformist" or "Dissenter" to describe those Puritans who had refused to conform in 1662.

Persecution of Dissenters, 1662-72

Though expelled from their pulpits in 1662, many of the non-conforming ministers continued to preach to their followers in private homes and other locations. These private meetings were known as conventicles. The congregations that they formed around the non-conforming ministers at this time form the nucleus for the later English Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and BaptistBaptist

Baptists comprise a group of Christian denominations and churches that subscribe to a doctrine that baptism should be performed only for professing believers , and that it must be done by immersion...

denominations

Christian denomination

A Christian denomination is an identifiable religious body under a common name, structure, and doctrine within Christianity. In the Orthodox tradition, Churches are divided often along ethnic and linguistic lines, into separate churches and traditions. Technically, divisions between one group and...

. The Cavalier Parliament responded hostilely to the continued influence of the non-conforming ministers. In 1664, it passed the Conventicle Act

Conventicle Act 1664

The Conventicle Act of 1664 was an Act of the Parliament of England that forbade conventicles...

banning religious assemblies of more than five people outside of the Church of England. In 1665, it passed the Five Mile Act

Five Mile Act 1665

The Five Mile Act, or Oxford Act, or Nonconformists Act 1665, is an Act of the Parliament of England , passed in 1665 with the long title "An Act for restraining Non-Conformists from inhabiting in Corporations". It was one of the English penal laws that sought to enforce conformity to the...

, forbidding ejected ministers from living within five miles of a parish from which they had been banned, unless they swore an oath never to resist the king, or attempt to alter the government of Church or State. Under the penal laws forbidding religious dissent (generally known to history as the Clarendon Code), many ministers were imprisoned in the latter half of the 1660s. One of the most notable victims of the penal laws during this period (though he was not himself an ejected minister) was John Bunyan

John Bunyan

John Bunyan was an English Christian writer and preacher, famous for writing The Pilgrim's Progress. Though he was a Reformed Baptist, in the Church of England he is remembered with a Lesser Festival on 30 August, and on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church on 29 August.-Life:In 1628,...

,a Baptist, who was imprisoned from 1660 to 1672.

At the same time that the Cavalier Parliament was ratcheting up the legal penalties against religious dissent, there were various attempts from the side of government and bishops, to establish a basis for "comprehension", a set of circumstances under which some dissenting ministers could return to the Church of England. These schemes for comprehension would have driven a wedge between Presbyterians and the group of Independents; but the discussions that took place between Latitudinarian figures in the Church and leaders such as Baxter and Manton never bridged the gap between Dissenters and the "high church" party in the Church of England, and comprehension ultimately proved impossible to achieve.

The Road to Religious Toleration for the Dissenters, 1672-89

In 1670, Charles II had signed the Secret Treaty of DoverSecret treaty of Dover

The Treaty of Dover, also known as the Secret Treaty of Dover, was a treaty between England and France signed at Dover on June 1 in 1670. It required France to assist England in the king's aim that it would rejoin the Roman Catholic Church and England to assist France in her war of conquest...

with Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

. In this treaty he committed to securing religious toleration for the Roman Catholic recusants in England. In March 1672, Charles issued his Royal Declaration of Indulgence

Royal Declaration of Indulgence

The Royal Declaration of Indulgence was Charles II of England's attempt to extend religious liberty to Protestant nonconformists and Roman Catholics in his realms, by suspending the execution of the penal laws that punished recusants from the Church of England...

, which suspended the penal laws against the dissenters and eased restrictions on the private practice of Catholicism. Many imprisoned dissenters (including John Bunyan) were released from prison in response to the Royal Declaration of Indulgence.

The Cavalier Parliament reacted hostilely to the Royal Declaration of Indulgence. Supporters of the high church party in the Church of England resented the easing of the penal laws, while many across the political nation suspected that Charles II was plotting to restore Catholicism to England. The Cavalier Parliament's hostility forced Charles to withdraw the declaration of indulgence, and the penal laws were again enforceable. In 1673, Parliament passed the first Test Act

Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and Nonconformists...

, requiring all officeholders in England to abjure the doctrine of transubstantiation

Transubstantiation

In Roman Catholic theology, transubstantiation means the change, in the Eucharist, of the substance of wheat bread and grape wine into the substance of the Body and Blood, respectively, of Jesus, while all that is accessible to the senses remains as before.The Eastern Orthodox...

(thus ensuring no Catholics could hold office in England).

Later trends

Puritan experience underlay the later LatitudinarianLatitudinarian

Latitudinarian was initially a pejorative term applied to a group of 17th-century English theologians who believed in conforming to official Church of England practices but who felt that matters of doctrine, liturgical practice, and ecclesiastical organization were of relatively little importance...

and Evangelical trends in the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

. Divisions between Presbyterian and Congregationalist groups in London became clear in the 1690s, and with the Congregationalists following the trend of the older Independents, a split became perpetuated. The Salters' Hall conference of 1719 was a landmark, after which many of the congregations went their own way in theology. In Europe, in the 17th and 18th centuries, a movement within Lutheranism parallel to puritan ideology (which was mostly of a Calvinist orientation) became a strong religious force known as pietism

Pietism

Pietism was a movement within Lutheranism, lasting from the late 17th century to the mid-18th century and later. It proved to be very influential throughout Protestantism and Anabaptism, inspiring not only Anglican priest John Wesley to begin the Methodist movement, but also Alexander Mack to...

. In the USA, the Puritan settlement of New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

was a major influence on American Protestantism.

With the start of the English Civil War in 1642, fewer settlers to New England were Puritans. The period fo 1642 to 1659 represented a period of peaceful dominance in English life by the formerly discriminated Puritan population. Consequently, most felt no need to settle in the American colonies. Very few immigrants to Virginia and other early colonies, in any case, were Puritans, with Virginia being a repository for more middle class and "royalist" oriented settlers leaving England following their loss of power during the English Commonwealth. Many migrants to New England who had looked for greater religious freedom found the Puritan theocracy

Theocracy

Theocracy is a form of organization in which the official policy is to be governed by immediate divine guidance or by officials who are regarded as divinely guided, or simply pursuant to the doctrine of a particular religious sect or religion....

to be repressive, examples being Roger Williams

Roger Williams (theologian)

Roger Williams was an English Protestant theologian who was an early proponent of religious freedom and the separation of church and state. In 1636, he began the colony of Providence Plantation, which provided a refuge for religious minorities. Williams started the first Baptist church in America,...

, Stephen Bachiler

Stephen Bachiler

Stephen Bachiler was an English clergyman who was an early proponent of the separation of church and state in America.-Early life:...

, Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson was one of the most prominent women in colonial America, noted for her strong religious convictions, and for her stand against the staunch religious orthodoxy of 17th century Massachusetts...

, and Mary Dyer

Mary Dyer

Mary Baker Dyer was an English Puritan turned Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony , for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony...

. Puritan populations in New England, continued to grow, with many large and prosperous Puritan families. (See Estimated Population 1620–1780: Immigration to the USA.)