Constitutional history of Canada

Encyclopedia

The constitution

al history of Canada

begins with the 1763 Treaty of Paris

, in which France ceded most of New France

to Great Britain. Canada

was the colony along the St Lawrence River, part of present-day Ontario

and Quebec

. Its government underwent many structural changes over the following century. In 1867 Canada became the name of the new federal Dominion

extending ultimately from the Atlantic to the Pacific and the Arctic coasts. Canada obtained legislative autonomy

from the United Kingdom in 1931, and had its constitution (including a new rights charter

) patriated

in 1982. Canada's constitution

includes the amalgam of constitutional law spanning this history.

(Nova Scotia

) and Cape Breton Island

to Great Britain. A year before, France had secretly signed a treaty

ceding Louisiana to Spain to avoid losing it to the British.

At the time of the signing, the French colony of Canada was already under the control of the British army since the capitulation of the government of New France

in 1760. (See the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal

.)

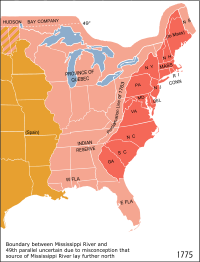

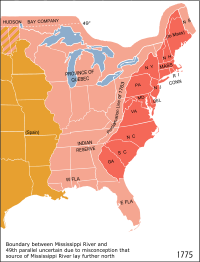

The policy of Great Britain regarding its newly acquired colonies of America was revealed in a Royal Proclamation, issued on October 7, 1763. The proclamation renamed Canada "The Province of Quebec", redefined its borders and established a British-appointed colonial government. Although not a constitutional text, the proclamation expressed the will of the British sovereign to make statutes for its new possessions. The proclamation was thus considered as the de facto constitution of Quebec until 1774. The new governor of the colony was given "the power and direction to summon and call a general assembly of the people's representatives" when the "state and circumstances of the said Colonies will admit thereof".

The policy of Great Britain regarding its newly acquired colonies of America was revealed in a Royal Proclamation, issued on October 7, 1763. The proclamation renamed Canada "The Province of Quebec", redefined its borders and established a British-appointed colonial government. Although not a constitutional text, the proclamation expressed the will of the British sovereign to make statutes for its new possessions. The proclamation was thus considered as the de facto constitution of Quebec until 1774. The new governor of the colony was given "the power and direction to summon and call a general assembly of the people's representatives" when the "state and circumstances of the said Colonies will admit thereof".

The governor was also given the mandate to "make, constitute, and ordain Laws, Statutes, and Ordinances for the Public Peace, Welfare, and good Government of our said Colonies, and of the People and Inhabitants thereof" with the consent of the British-appointed councils and representatives of the people. In the meantime, all British subjects in the colony were guaranteed of the protection of the law of England, and the governor was given the power to erect courts of judicature and public justice to hear all causes, civil or public.

The Royal Proclamation contained elements that conflicted with the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal, which granted Canadians the privilege to maintain their civil laws and practise their religion. The application of British laws such as the penal Laws caused numerous administrative problems and legal irregularities. The requirements of the Test Act

also effectively excluded Catholics from administrative positions in the British Empire.

When James Murray

was commissioned as captain general and governor in chief of the Province of Quebec, a four-year military rule ended, and the civil administration of the colony began. Judging the circumstances to be inappropriate to the establishment of British institutions in the colony, Murray was of the opinion that it would be more practical to keep the current civil institutions. He believed that, over time, the Canadians would recognize the superiority of British civilization and willingly adopt its language, its religion, and its customs. He officially recommended to retain French civil law and to dispense the Canadians from taking the Oath of Supremacy

. Nevertheless, Murray followed his instructions and British institutions began to be established. On September 17, 1764, the Courts of the King's Bench

and Common Pleas

were constituted.

Tensions quickly developed between the British merchants or old subjects, newly established in the colony, and Governor Murray. They were very dissatisfied with the state of the country and demanded that British institutions be created immediately. They demanded that common law

be enforced to protect their business interests and that a house of assembly be created for English-speaking Protestants alone. Murray didn't think very highly of these tradesmen. In a letter to the British Lords of Trade, he referred to them as "licentious fanatics" who would not be satisfied but by "the expulsion of the Canadians".

The conciliatory approach of Murray in dealing with the demands of the Canadians was not well received by the merchants. In May 1764, they petitioned the king for Murray's removal, accusing him of betraying the interests of Great Britain by his defence of the Canadian people's interests. The merchants succeeded in having him recalled to London. He was vindicated, but did not return to the Province of Quebec. In 1768, he was replaced by Sir Guy Carleton, who would contribute to the drafting of the 1774 Quebec Act

.

Murray called in the representatives of the people in 1765; however, his attempt to constitute a representative assembly failed, as, according to historian Francois-Xavier Garneau

, the Canadians were unwilling to renounce their Catholic faith and take the test oath required to hold office.

In December 1773 Canadian landlords submitted a petition and a memorandum in which they asked:

They expressed their opinion that the time was not right for a house of assembly because the colony could not afford it and suggested that a larger council, composed of both new and old subjects, would be a better choice.

In May 1774 the British merchants trading in Quebec responded by submitting their case to the king.

The movement for reform did not receive any support from the Canadians originally.

granted many of the requests of the Canadians. Enacted on June 13, 1774, the act changed the following:

No assembly of representatives was created, which allowed the governor to keep ruling under the advice of his counsellors.

The British merchants of Quebec were not pleased by this new act, which ignored their most important demands. They continued to campaign to abolish the current civil code and establish a house of assembly excluding Catholics and French-speakers.

The Quebec Act was also very negatively received in the British colonies to the south. (See the Intolerable Acts

.) This act was in force in the Province of Quebec when the American Revolutionary War

broke out in April 1775.

attempted to rally the Canadian people to its cause. The delegates wrote three letters (Letters to the inhabitants of Canada) inviting them to join in the revolution. The letters circulated in Canada, mostly in the cities of Montreal and Quebec. The first letter was written on October 26, 1774, and signed by the president of the congress, Henry Middleton

. It was translated into French by Fleury Mesplet

, who printed it in Philadelphia and distributed the copies himself in Montreal.

The letter pleaded the cause of democratic government, the separation of powers

, taxation power

, habeas corpus

, trial by jury

, and freedom of the press

.

The second letter was written on May 25, 1775. Shorter, it urged the inhabitants of Canada not to side against the revolutionary forces. (The congress was aware that the British colonial government had already asked the Canadians to resist the call of the revolutionaries.)

On May 22, 1775, Bishop of Quebec Jean-Olivier Briand

sent out a mandement asking the Canadians to close their ears to the call of the "rebels" and defend their country and their king against the invasion.

Although both the British and the revolutionaries succeeded at recruiting Canadian men for militia, the majority of the people chose not to get involved in the conflict.

In 1778, Frederick Haldimand

became governor in replacement of Guy Carleton. (He served up until 1786, when Guy Carleton (now Lord Dorchester) returned as governor.)

in 1783, the constitutional question resurfaced.

In July 1784, Pierre du Calvet

, a rich French merchant established in Montreal, published a pamphlet entitled Appel à la justice de l'État (Call to the Justice of the State) in London. Printed in French, the document is the first plea in favour of a constitutional reform in Canada. Du Calvet, imprisoned at the same time and for the same reasons as Fleury Mesplet and Valentine Jautard, both suspected of symphatizing and collaborating with the American revolutionaries during the war, undertook to have the injustice committed towards him be publicly known by publishing The Case of Peter du Calvet and, a few months later, his Appel à la justice de l'État.

On November 24, 1784, two petition for a house of assembly, one signed by 1436 "New Subjects" (Canadians) and another signed by 855 "Old Subjects" (British), were sent to the king of Great Britain. The first petition contained 14 demands. "A Plan for a House of Assembly" was also sketched in the same month of November. In December, "An Address to His Majesty in opposition to the House of Assembly and a list of Objections" were printed by the press of Fleury Mesplet

in Montreal. The main objection to the house of assembly was that the colony was not, according to its signatories, in a position to be taxed.

At the time the November 24 petition was submitted to the king, numerous United Empire Loyalists

were already seeking refuge in Quebec and Nova Scotia

. In Quebec, the newly arrived settlers contributed to increase the number of people voicing for a rapid constitutional reform. In Nova Scotia, the immigrants demanded a separate colony.

, as "governor-in-chief" and also governor of each of the four colonies. Carleton, now Lord Dorchester, had been British commander in Canada and governor of Quebec during the American Revolutionary War

. When he returned as governor, he was already informed that the arrival of the Loyalists would require changes.

On October 20, 1789, Home Secretary William Wyndham Grenville wrote a private and secret letter to Carleton, informing him of the plans of the king's counsellors to modify Canada's constitution. The letter leaves little doubt as to the influence that American independence and the taking of the Bastille

(which had just occurred in July) had on the decision. In the first paragraph, Grenville writes: "I am persuaded that it is a point of true Policy to make these Concessions at a time when they may be received as matter of favour, and when it is in Our own power to regulate and direct the manner of applying them, rather than to wait 'till they shall be extorted from Us by a necessity which shall neither leave Us any discretion in the form, nor any merit in the substance of what we give."

Grenville prepared the constitution in August 1789. But he was appointed to the House of Lords before he could submit his project to the House of Commons. Thus, Prime Minister William Pitt

did it in his place.

British merchants established in Quebec sent Adam Lymburner to Britain to present their objections. They objected to the creation of two provinces, suggested an increase in the number of representatives, asked for elections every three years (instead of seven), and requested an electoral division which would have overrepresented the Old Subjects by granting more representatives to the populations of the cities.

Lymburner's revisions were opposed by Whigs such as Charles James Fox

, and in the end only the suggestions related to the frequency of elections and the number of representatives were retained.

This partition ensured that Loyalists would constitute a majority in Upper Canada and allow for the application of exclusively British laws in this province. As soon as the province was divided, a series of acts were passed to abolish the French civil code in Upper Canada. In Lower Canada, the coexistence of French civil law and English criminal law continued.

Although it solved the immediate problems related to the settlement of the Loyalists in Canada, the new constitution brought a whole new set of political problems which were rooted in the constitution. Some of these problems were common to both provinces, while others were unique to Lower Canada or Upper Canada. The problems that eventually affected both provinces were:

In the two provinces, a movement for constitutional reform took shape within the majority party, the Parti canadien

of Lower Canada and the Reformers of Upper Canada. Leader of the Parti Canadien, Pierre-Stanislas Bédard was the first politician of Lower Canada to formulate a project of reform to put an end to the opposition between the elected Legislative Assembly and the Governor and his Council which answered only the Colonial Office

in London. Putting forward the idea of ministerial responsibility, he proposed that the members of the Legislative Council be appointed by the Governor on the recommendation of the elected House.

and his under-secretary Robert John Wilmot-Horton secretly submitted a bill to British House of Commons which projected the legislative union of the two Canadian provinces. Two months after the adjournment of the discussions on the bill, the news arrived in Lower Canada and caused a sharp reaction.

Supported by Governor Dalhousie, anglophone petitioners from the Eastern Townships, Quebec City and Kingston, the bill submitted in London provided, among other things, that each of the two sections of the new united province would have a maximum of 60 representatives, which would have put the French-speaking majority of Lower Canada in a position of minority in the new Parliament.

The mobilization of the citizens of Lower Canada and Upper Canada began in late summer and petitions in opposition to the project were prepared. The subject was discussed as soon as the session at the Parliament of Lower Canada opened on January 11, 1823. Ten days later, on January 21, the Legislative Assembly adopted a resolution authorizing a Lower Canadian delegation to go to London in order to officially present the quasi-unanimous opposition of the representatives of Lower Canada to the project of union. Exceptionally, even the Legislative Council gave its support to this resolution, with a majority of one vote. Having in their possession a petition of some 60 000 signatures, the Speaker of the House of Assembly, Louis-Joseph Papineau

, as well as John Neilson

, Member of Parliament, went to London to present the opinion of the majority of the population which they represented.

Faced with the massive opposition of people most concerned with the bill, the British government finally gave up the union project submitted for adoption by its own Colonial Office.

It reported on July 22 of the same year. It recommended against the union of Upper Canada and Lower Canada and in favour of constitutional and administrative reforms intended to prevent the recurrence of the abuses complained of in Lower Canada.

. They demanded the application of the elective principle to the political institutions of the province, after the American model; but did not advocate, in any explicit way, the introduction of responsible government. Lord Aylmer, the governor-general of Canada at that time, in an analysis of the resolutions, maintained that "eleven of them represented the truth; six contained truth mixed with falsehood; sixteen were wholly false; seventeen were doubtful; twelve were ridiculous; seven repetitions; fourteen consisted of abuse; four were both false and seditious; and the remaining five were indifferent."

. The Royal Commission for the Investigation of all Grievances Affecting His Majesty's Subjects of Lower Canada reported on November 17, 1836 and the Ten resolutions of John Russel were mostly based on it.

Most of the recommendations brought forth by the elected assemblies were systematically ignored by the Executive Councils. This was particularly true in Lower Canada with an assembly consisting mostly of French-Canadian members of the Parti Patriote. This impasse created considerable tensions between the French-Canadian political class and the British government. In 1834 Louis-Joseph Papineau

, a French-Canadian political leader, submitted a document entitled the Ninety-Two Resolutions

to the Crown. The document requested vast democratic reforms such as the transfer of power to elected representatives. The reply came three years later in the form of the Russell Resolutions, which not only rejected the 92 Resolutions but also revoked one of the assembly's few real powers, the power to pass its own budget. This rebuff heightened tensions and escalated into armed rebellions in 1837 and 1838, known as the Lower Canada Rebellion

. The uprisings were short-lived, however, as British troops quickly defeated the rebels and burned their villages in reprisal.

The rebellion was also contained by the Catholic clergy, which, by representing the only French-Canadian institution with independent authority, exercised a tremendous influence over its constituents. During and after the rebellions Catholic priests and the bishop of Montreal told their congregants that questioning established authority was a sin that would prevent them from receiving the sacraments. The Church refused to give Christian burials to supporters of the rebellion. With liberal and progressive forces suppressed in Lower Canada, the Catholic Church's influence dominated the French-speaking side of French Canadian/British relations from the 1840s until the Quiet Revolution

secularized Quebec society in the 1960s.

in the district of Montreal, Governor Gosford suspends, on March 27, 1838, the Constitutional Act of 1791 and sets up a Special Council

.

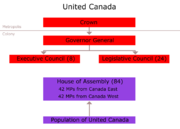

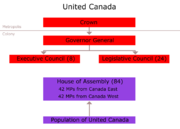

Following the publication of the Report on the Affairs of British North America, the British Parliament adopted, in June 1840, the Act of Union. The new Act, which effected the legislative union of Upper Canada and Lower Canada to form a single province named the Province of Canada, implemented the principal recommendation of John George Lambton's report, but did not grant a "responsible government" to the new political entity. Entering into force as of February 1841, the 62 articles of the Act of Union brought about the following changes:

Following the publication of the Report on the Affairs of British North America, the British Parliament adopted, in June 1840, the Act of Union. The new Act, which effected the legislative union of Upper Canada and Lower Canada to form a single province named the Province of Canada, implemented the principal recommendation of John George Lambton's report, but did not grant a "responsible government" to the new political entity. Entering into force as of February 1841, the 62 articles of the Act of Union brought about the following changes:

As a result, Lower Canada and Upper Canada, with its enormous debt, were united in 1840, and French was banned in the legislature for about eight years. Eight years later, an elected and responsible government

was granted. By this time, the French-speaking majority of Lower Canada had become a political minority in a unified Canada. This, as Lord Durham had recommended in his report, resulted in English political control over the French-speaking part of Canada, and ensured the colony's loyalty to the British crown. On the other hand, continual legislative deadlock between English and French led to a movement to replace unitary government with a federal one. This movement culminated in Canadian Confederation

.

and Robert Baldwin

, form their own Executive Council. The Province of Canada therefore had its first government made up of members taken in the elected House of Assembly. This important change occurred a few months after Governor of Nova Scotia, Sir John Harvey

, let James Boyle Uniacke

form his own government. Nova Scotia thus became the first colony of the British Empire to have a government comparable to that of Great Britain itself.

, doctor and journalist from Quebec City, publish a detailed project of federation. It is the first time that a project of this type is presented publicly since the proposal that John A. Roebuck had made in the same direction to John George Lambton while he was a governor of the Canadas in 1838.

The same year, Alexander T. Galt, Member of Parliament for Sherbrooke, agrees to become a Minister of Finance in the Macdonald-Cartier government provided that his own project of confederation is accepted.

The British North America Act 1867 was the act that established the Dominion of Canada, by the fusion of the North American British colonies of the Province of Canada

The British North America Act 1867 was the act that established the Dominion of Canada, by the fusion of the North American British colonies of the Province of Canada

, Province of New Brunswick

, Province of Nova Scotia

. The former subdivisions of Canada were renamed from Canada West and Canada East

to the Province of Ontario

and Province of Quebec

, respectively. Quebec and Ontario were given equal footing with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in the Parliament of Canada

. This was done to counter the claims of manifest destiny

made by the United States of America, for the defense of Britain's holdings. American claims are evinced by the invasions of the Canadas

during the British-American War (1812) and the British-American War (1776).

Prior to the BNA Act of 1867, the British colonies of the Province of New Brunswick, Province of Nova Scotia, and Province of Prince Edward Island

, discussed the possibility of a fusion to counter the threat of American annexation, and to reduce the costs of governance. The Province of Canada entered these negotiations at the behest of the British government, and this led to the ambivalence of the Province of Prince Edward Island, which later joined the new Dominion. The constitutional conference, ironically, was held on Prince Edward Island, in Charlottetown

. The colony of Newfoundland also participated (at the Quebec Conference) and likewise declined to join.

On May 12, 1870, the British Crown proclaimed the Manitoba Act, enacted by the Parliament of Canada, effectivement giving birth to the province of Manitoba. The 36 articles of the Act established the territorial limits, the subjects' right to vote, the representation in the Canadian House of Commons, the number of senators, the provincial legislature, permitted the use of English and French in the Parliament and in front of the courts and authorized the setting-up of a denominational education system.

The coexistence, on the territory of the province, of French-speaking and Catholic communities (the Métis) as well as English-speaking and Protestant communities (British and Anglo-Canadian immigrants) explains the institutional arrangement copied on that of Quebec.

, but prior to the Canada Act 1982

the British North America Acts were excluded from the operation of the Statute of Westminster and could only be amended by the British Parliament.

, stemming from a new assertiveness and a heightened sense of national identity among Québécois

, dramatically changed the face of Quebec's institutions. The new provincial government headed by Jean Lesage

and operating under the slogans "Il faut que ça change!" and "Maître chez nous" ("It must change!", "Masters in our own house") secularized government institutions, nationalized electricity production and encouraged unionization. The reforms sought to redefine the relations between the vastly working-class francophone Québécois and the mostly anglophone business class. Thus passive Catholic nationalism stylized by Father Lionel Groulx

gave way to a more active pursuit of independence, and in 1963 the first bombings by the Front de libération du Québec

occurred. The FLQ's violent pursuit of a socialist and independent Quebec culminated in the 1970 kidnappings of British diplomat, James Cross

and then the provincial minister of labour, Pierre Laporte

in what is known as the October Crisis

.

The Quiet Revolution also forced the evolution of several political parties, and so, in 1966, a reformed Union Nationale led by Daniel Johnson, Sr., returned to power under the slogan "Equality or Independence". The new premier of Quebec stated, "As a basis for its nationhood, Quebec wants to be master of its own decision-making in what concerns the human growth of its citizens—that is to say education, social security and health in all their aspects—their economic affirmation—the power to set up economic and financial institutions they feel are required—their cultural development—not only the arts and letters, but also the French language—and the Quebec community's external development—its relations with certain countries and international bodies".

. It proposed an amending formula that included unanimous consent of Parliament and all provinces for select areas of jurisdiction, the consent of Parliament and of the provinces concerned for provisions affecting one or more, but not all of the provinces, the consent of Parliament and of all the provinces except Newfoundland in matters of education, and the consent of Parliament and of the legislature of Newfoundland in matters of education in that province. For all other amendments, consent of Parliament and of at least two-thirds of the provincial legislatures representing at least 50 per cent of the population of Canada would be required. Agreement amongst the provinces was not achieved and the proposal was not implemented, but it was revived again with the Fulton-Favreau Formula in 1964, and several components were included in the Constitution Act, 1982

.

of Ontario

, a provincial first ministers' conference was held in Toronto to discuss the Canadian confederation of the future. From this, a first round of what would become annual constitutional meetings of all provincial premiers and the prime minister of Canada, was held in February 1968. On the initiative of Prime Minister Lester Pearson the conference undertook to address the desires of Quebec. Amongst numerous initiatives, the conference members examined the recommendations of a Bilingualism and Biculturalism Commission, the question of a Charter of Rights, regional disparities, and the timelines of a general review of the constitution (the British North America Act).

In 1968, René Lévesque

's Mouvement souveraineté-association

joined forces with the Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale

and the Ralliement national

to create the Parti Québécois

; Quebec's provincial political party that has since espoused the province's sovereignty. That same year, Pierre Trudeau

became prime minister of Canada by winning the leadership race of the federal Liberal Party. He would undertake numerous legislative measures to enhance the status of Quebec within Canada, including the passage into law in 1969 of the Official Languages Act

, which expanded upon the original official language status of both French and English from the 1867 British North America Act.

and Quebec Liberal Guy Favreau

in the 1960s and approved at a federal-provincial conference in 1965. The formula would have achieved the patriation of the Constitution. Under the formula, all provinces would have to approve amendments that would be relevant to provincial jurisdiction, including the use of the French and English languages, but only the relevant provinces would be needed to approve amendments concerned with a particular region of Canada. The provinces would have been given the right to enact laws amending their respective constitutions, except for provisions concerning the office of Lieutenant Governor. Two-thirds of the provinces representing half of the population, as well as the federal Parliament, would be needed for amendments regarding education. The formula officially died in 1965 when Quebec Premier Jean Lesage

withdrew his support. Modified versions re-emerged in the Victoria Charter (1971) and in the Constitution Act, 1982

.

the Parti Québécois sought a mandate from the people of Quebec to negotiate new terms of association with the rest of Canada. With an 84-per-cent voter turnout, 60 per cent of Quebec voters rejected the proposal.

After the 1980 referendum was defeated, the government of Quebec passed Resolution 176, which stated, "A lasting solution to the constitutional issue presupposes recognition of the Quebec-Canada duality."

Meeting in Ottawa on June 9, 1980, the newly re-appointed Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau and the provincial premiers set an agenda and gave their ministers responsibility for constitutional issues and a mandate to proceed with exploratory discussions to create a new Canadian constitution. However, given the separatist government of Quebec's position that there be two nations established first in accordance with Resolution 176, approval by Quebec of any changes to the BNA Act was impossible. This assertion of national duality was immediately followed with Resolution 177 that stated, "Quebec will never agree, under the existing system, to the patriation of the Constitution and to an amending formula as long as the whole issue of the distribution of powers has not been settled and Quebec has not been guaranteed all the powers it needs for its development." As such, Quebec's government refused to approve the new Canadian constitution a year later. This failure to approve was a highly symbolic act, but one without direct legal consequence as no one questions the authority of the Canadian Constitution within Quebec.

After losing the vote to secede from Canada, the government of Quebec made specific demands as minimum requirements for the Province of Quebec. These demands included control by the government of Quebec over:

The province of Quebec already had theoretically full control over education, health, mineral

resources, supplemental taxation, social services, seniors' retirement pension funds, inter-provincial trade, and other areas affecting the daily lives of its citizens. Many Canadians viewed the additional demands as too greatly reducing the power of the federal government, assigning it the role of tax collector and manager of the national border with the United States. Others viewed these changes as desirable, concentrating power in the hands of Québécois politicians, who were more in tune with Québécois desires and interests.

Though the Parti Québécois government said that the federal government of Canada would be responsible for international relations, Quebec proceeded to open its own representative offices in foreign countries around the world. These quasi-embassies were officially named "Quebec Houses". Today, the international affairs minister is responsible for the less-expensive Quebec delegation system.

). The agreement was enacted as the Canada Act

by the British Parliament, and was proclaimed into law by Queen Elizabeth II on April 17, 1982. In Canada, this was called the patriation

of the Constitution.

This action (including the creation of a new Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

) came from an initiative by Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau to create a multicultural and bilingual society in all of Canada. Some Canadians saw Trudeau's actions as an attempt to "shove French down their throats" (a common phrase at the time). Many Québécois viewed his compromise as a sell-out and useless: Quebec already had a charter enacted in 1975 and was not interested in imposing French on other provinces; rather, it wished to safeguard it inside Quebec. Many Canadians recognize that the province of Quebec is distinct and unique but they do not conclude from this that Quebec merits a position of greater autonomy than the other provinces, which they feel would be the result of granting special powers that are unavailable to the other provinces.

The government of Quebec, in line with its policy of the duality of nations, objected to the new Canadian constitutional arrangement of 1982 (the patriation), because its formula for future constitutional amendments failed to give Quebec veto power over all constitutional changes.

Some believe that the leaders of Quebec used their refusal to agree to the 1982 constitutional amendment as a bargaining tool to gain leverage in future negotiations, because the federal Canadian government desired (though it is not legally necessary) to include all the provinces willingly into the amended constitution. The National Assembly of Quebec rejected the repatriation unanimously. In spite of Quebec's lack of assent, the constitution still applies within Quebec and to all Quebec residents. Many in Quebec felt that the other provinces' adoption of the amendment without Quebec's assent was a betrayal of the central tenets of federalism. They referred to the decision as the "Night of the Long Knives". On the other hand, many federalists believe that Lévesque's goal at the constitutional conference was to sabotage it and prevent any agreement from being reached, so that he could hold it up as another failure of federalism. In this school of thought, patriation without Quebec's consent was the only option.

in 1995 – only narrowly lost – shook Canada to its core, and would bring about the Clarity Act

.

attempted to address these concerns and bring the province into an amended constitution. Quebec's provincial government, then controlled by a party that advocated remaining in Canada on certain conditions (the Parti libéral du Québec), endorsed the accord (called the Meech Lake Accord

). Premier Robert Bourassa

of Quebec referred to it as the "first step" towards gaining new powers from the federal government. The accord failed, however, as the legislature in Manitoba

deadlocked after Elijah Harper

refused consent to speed up the process enough to pass the Accord, and Clyde Wells

refused to grant a vote on the Accord in the Newfoundland House of Assembly.

In 1990, after the Meech Lake Accord had failed, several Quebec representatives of the ruling Progressive Conservative Party

and some members of the Liberal Party of Canada

formed the Bloc Québécois

, a federal political party intent on defending Quebecers' interests while pursuing independence.

. Despite near-unanimous support from the country's political leaders, this second effort at constitutional reform was rejected in a nation-wide October 1992 referendum. Only 32 per cent of British Columbians supported the accord, because it was seen there and in other western provinces as blocking their hopes for future constitutional changes, such as Senate reform. In Quebec 57 per cent opposed the accord, seeing it as a step backwards compared to the Meech Lake Accord.

In the 1993 federal elections the Bloc Québécois became the official opposition. The following year, the provincial Parti Québécois, also separatist, was elected in Quebec. The two parties' popularity led to a second referendum on independence, the 1995 Quebec referendum

.

in December 1999. The Court ruled that Quebec, with less than 23 percent of Canada's population, could not unilaterally secede and only accede to sovereignty if the referendum has a clear majority in favour of a clearly worded question.

Following the Supreme Court's decision, the federal government introduced legislation known as the Clarity Act

which set forth the guidelines for any future referendum undertaken by the government of any province on the subject of separation. Ironically, the definition of "clearly worded" and "clear majority" were never given in the bill. Instead, it stated that the federal government would determine "whether the question is clear" and whether a "clear majority" (with a requisite supermajority

for success being inferred) is attained. Sovereigntists argue that this bill grants veto power to the federal government over referendums on sovereignty.

Consequentially, with a majority vote supported by all members of the House of Commons, except for members of the Bloc Québécois, both houses of the Parliament approved the legislation.

In recent years, some residents of the oil

-rich province of Alberta

have advocated for increased autonomy, following Canada's ratification of the Kyoto Protocol

.

Constitution of Canada

The Constitution of Canada is the supreme law in Canada; the country's constitution is an amalgamation of codified acts and uncodified traditions and conventions. It outlines Canada's system of government, as well as the civil rights of all Canadian citizens and those in Canada...

al history of Canada

History of Canada

The history of Canada covers the period from the arrival of Paleo-Indians thousands of years ago to the present day. Canada has been inhabited for millennia by distinctive groups of Aboriginal peoples, among whom evolved trade networks, spiritual beliefs, and social hierarchies...

begins with the 1763 Treaty of Paris

Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, often called the Peace of Paris, or the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763, by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement. It ended the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War...

, in which France ceded most of New France

New France

New France was the area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Spain and Great Britain in 1763...

to Great Britain. Canada

Canada, New France

Canada was the name of the French colony that once stretched along the St. Lawrence River; the other colonies of New France were Acadia, Louisiana and Newfoundland. Canada, the most developed colony of New France, was divided into three districts, each with its own government: Quebec,...

was the colony along the St Lawrence River, part of present-day Ontario

Ontario

Ontario is a province of Canada, located in east-central Canada. It is Canada's most populous province and second largest in total area. It is home to the nation's most populous city, Toronto, and the nation's capital, Ottawa....

and Quebec

Quebec

Quebec or is a province in east-central Canada. It is the only Canadian province with a predominantly French-speaking population and the only one whose sole official language is French at the provincial level....

. Its government underwent many structural changes over the following century. In 1867 Canada became the name of the new federal Dominion

Dominion

A dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

extending ultimately from the Atlantic to the Pacific and the Arctic coasts. Canada obtained legislative autonomy

Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

from the United Kingdom in 1931, and had its constitution (including a new rights charter

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms is a bill of rights entrenched in the Constitution of Canada. It forms the first part of the Constitution Act, 1982...

) patriated

Canada Act 1982

The Canada Act 1982 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that was passed at the request of the Canadian federal government to "patriate" Canada's constitution, ending the necessity for the country to request certain types of amendment to the Constitution of Canada to be made by the...

in 1982. Canada's constitution

Constitution of Canada

The Constitution of Canada is the supreme law in Canada; the country's constitution is an amalgamation of codified acts and uncodified traditions and conventions. It outlines Canada's system of government, as well as the civil rights of all Canadian citizens and those in Canada...

includes the amalgam of constitutional law spanning this history.

Treaty of Paris (1763)

On February 10, 1763, France ceded most of New France to Great Britain. The 1763 Treaty of Paris confirmed the cession of Canada, including all its dependencies, AcadiaAcadia

Acadia was the name given to lands in a portion of the French colonial empire of New France, in northeastern North America that included parts of eastern Quebec, the Maritime provinces, and modern-day Maine. At the end of the 16th century, France claimed territory stretching as far south as...

(Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

) and Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America. It likely corresponds to the word Breton, the French demonym for Brittany....

to Great Britain. A year before, France had secretly signed a treaty

Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762)

The Treaty of Fontainebleau was a secret agreement in which France ceded Louisiana to Spain. The treaty followed the last battle in the French and Indian War, the Battle of Signal Hill in September 1762, which confirmed British control of Canada. However, the associated Seven Years War continued...

ceding Louisiana to Spain to avoid losing it to the British.

At the time of the signing, the French colony of Canada was already under the control of the British army since the capitulation of the government of New France

New France

New France was the area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Spain and Great Britain in 1763...

in 1760. (See the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal

Articles of Capitulation of Montreal

The Articles of Capitulation of Montreal were agreed upon between the Governor General of New France, Pierre François de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal, and Major-General Jeffrey Amherst on behalf of the French and British crowns...

.)

Royal proclamation (1763)

The governor was also given the mandate to "make, constitute, and ordain Laws, Statutes, and Ordinances for the Public Peace, Welfare, and good Government of our said Colonies, and of the People and Inhabitants thereof" with the consent of the British-appointed councils and representatives of the people. In the meantime, all British subjects in the colony were guaranteed of the protection of the law of England, and the governor was given the power to erect courts of judicature and public justice to hear all causes, civil or public.

The Royal Proclamation contained elements that conflicted with the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal, which granted Canadians the privilege to maintain their civil laws and practise their religion. The application of British laws such as the penal Laws caused numerous administrative problems and legal irregularities. The requirements of the Test Act

Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and Nonconformists...

also effectively excluded Catholics from administrative positions in the British Empire.

When James Murray

James Murray (military officer)

James Murray FRS was a British soldier, whose lengthy career included service as colonial administrator and governor of the Province of Quebec and later as Governor of Minorca from 1778 to 1782.-Early life:He was a younger son of Alexander Murray, 4th Lord Elibank, and his wife Elizabeth...

was commissioned as captain general and governor in chief of the Province of Quebec, a four-year military rule ended, and the civil administration of the colony began. Judging the circumstances to be inappropriate to the establishment of British institutions in the colony, Murray was of the opinion that it would be more practical to keep the current civil institutions. He believed that, over time, the Canadians would recognize the superiority of British civilization and willingly adopt its language, its religion, and its customs. He officially recommended to retain French civil law and to dispense the Canadians from taking the Oath of Supremacy

Oath of Supremacy

The Oath of Supremacy, originally imposed by King Henry VIII of England through the Act of Supremacy 1534, but repealed by his daughter, Queen Mary I of England and reinstated under Mary's sister, Queen Elizabeth I of England under the Act of Supremacy 1559, provided for any person taking public or...

. Nevertheless, Murray followed his instructions and British institutions began to be established. On September 17, 1764, the Courts of the King's Bench

King's Bench

The Queen's Bench is the superior court in a number of jurisdictions within some of the Commonwealth realms...

and Common Pleas

Court of Common Pleas (England)

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century after splitting from the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common...

were constituted.

Tensions quickly developed between the British merchants or old subjects, newly established in the colony, and Governor Murray. They were very dissatisfied with the state of the country and demanded that British institutions be created immediately. They demanded that common law

Common law

Common law is law developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals rather than through legislative statutes or executive branch action...

be enforced to protect their business interests and that a house of assembly be created for English-speaking Protestants alone. Murray didn't think very highly of these tradesmen. In a letter to the British Lords of Trade, he referred to them as "licentious fanatics" who would not be satisfied but by "the expulsion of the Canadians".

The conciliatory approach of Murray in dealing with the demands of the Canadians was not well received by the merchants. In May 1764, they petitioned the king for Murray's removal, accusing him of betraying the interests of Great Britain by his defence of the Canadian people's interests. The merchants succeeded in having him recalled to London. He was vindicated, but did not return to the Province of Quebec. In 1768, he was replaced by Sir Guy Carleton, who would contribute to the drafting of the 1774 Quebec Act

Quebec Act

The Quebec Act of 1774 was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain setting procedures of governance in the Province of Quebec...

.

Murray called in the representatives of the people in 1765; however, his attempt to constitute a representative assembly failed, as, according to historian Francois-Xavier Garneau

François-Xavier Garneau

François-Xavier Garneau was a nineteenth century French Canadian notary, poet, civil servant and liberal who wrote a three-volume history of the French Canadian nation entitled Histoire du Canada between 1845 and 1848.Born in Quebec City, Garneau argued that Conquest was a tragedy, the consequence...

, the Canadians were unwilling to renounce their Catholic faith and take the test oath required to hold office.

Restoration movement (1764-1774)

On October 29, 1764, 94 Canadian subjects submitted a petition demanding that the orders of the king be available in French and that they be allowed to participate in the government.In December 1773 Canadian landlords submitted a petition and a memorandum in which they asked:

- That the ancient laws, privileges, and customs be restored in full

- That the province be extended to its former boundaries

- That the law of Britain be applied to all subjects without distinction

They expressed their opinion that the time was not right for a house of assembly because the colony could not afford it and suggested that a larger council, composed of both new and old subjects, would be a better choice.

In May 1774 the British merchants trading in Quebec responded by submitting their case to the king.

Reform movement (1765-1791)

As early as 1765, British merchants established in Quebec City address a petition to the King to ask for "the establishment of a house of representatives in this province as in all the other provinces" of the continent. Indeed, all the other colonies of British America had parliamentary institutions, even Nova Scotia which obtained its Parliament in 1758.The movement for reform did not receive any support from the Canadians originally.

Quebec Act (1774)

The Quebec ActQuebec Act

The Quebec Act of 1774 was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain setting procedures of governance in the Province of Quebec...

granted many of the requests of the Canadians. Enacted on June 13, 1774, the act changed the following:

- The boundaries of the Province of Quebec were greatly expanded to the west and south. The territory now covered the whole of the Great Lakes BasinGreat Lakes BasinThe Great Lakes Basin consists of the Great Lakes and the surrounding lands of the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin in the United States, and the province of Ontario in Canada, whose direct surface runoff and watersheds form a large...

. - The free practice of the Catholic faith was confirmed. The Roman Catholic Church was officially recognized and permitted to operate under British sovereignty.

- The Canadians were dispensed of the test oath, which was replaced by an oath to George III that had no reference to Protestantism. This made it possible for Canadians to hold positions in the colonial administration.

- French civil law was fully restored and British criminal law was established. The seigneurial method of land tenancy was thus maintained.

- A British criminal code was established.

No assembly of representatives was created, which allowed the governor to keep ruling under the advice of his counsellors.

The British merchants of Quebec were not pleased by this new act, which ignored their most important demands. They continued to campaign to abolish the current civil code and establish a house of assembly excluding Catholics and French-speakers.

The Quebec Act was also very negatively received in the British colonies to the south. (See the Intolerable Acts

Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts or the Coercive Acts are names used to describe a series of laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 relating to Britain's colonies in North America...

.) This act was in force in the Province of Quebec when the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

broke out in April 1775.

Letters to the inhabitants of the Province of Quebec (1774-1775)

During the revolution, the Continental CongressContinental Congress

The Continental Congress was a convention of delegates called together from the Thirteen Colonies that became the governing body of the United States during the American Revolution....

attempted to rally the Canadian people to its cause. The delegates wrote three letters (Letters to the inhabitants of Canada) inviting them to join in the revolution. The letters circulated in Canada, mostly in the cities of Montreal and Quebec. The first letter was written on October 26, 1774, and signed by the president of the congress, Henry Middleton

Henry Middleton

Henry Middleton was a plantation owner and public official from South Carolina. He was the second President of the Continental Congress from October 22, 1774, until Peyton Randolph was able to resume his duties briefly beginning on May 10, 1775.-Early life:Henry Middleton was born in 1717 near...

. It was translated into French by Fleury Mesplet

Fleury Mesplet

Fleury Mesplet was a French-born Canadian printer.Born in Marseille and apprenticed in Lyon, he emigrated to London in 1773 where he set up shop in Covent Garden. In 1774 he emigrated to Philadelphia; it is thought that he may have been persuaded to do so by Benjamin Franklin...

, who printed it in Philadelphia and distributed the copies himself in Montreal.

The letter pleaded the cause of democratic government, the separation of powers

Separation of powers

The separation of powers, often imprecisely used interchangeably with the trias politica principle, is a model for the governance of a state. The model was first developed in ancient Greece and came into widespread use by the Roman Republic as part of the unmodified Constitution of the Roman Republic...

, taxation power

No taxation without representation

"No taxation without representation" is a slogan originating during the 1750s and 1760s that summarized a primary grievance of the British colonists in the Thirteen Colonies, which was one of the major causes of the American Revolution...

, habeas corpus

Habeas corpus

is a writ, or legal action, through which a prisoner can be released from unlawful detention. The remedy can be sought by the prisoner or by another person coming to his aid. Habeas corpus originated in the English legal system, but it is now available in many nations...

, trial by jury

Trial by Jury

Trial by Jury is a comic opera in one act, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert. It was first produced on 25 March 1875, at London's Royalty Theatre, where it initially ran for 131 performances and was considered a hit, receiving critical praise and outrunning its...

, and freedom of the press

Freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the freedom of communication and expression through vehicles including various electronic media and published materials...

.

The second letter was written on May 25, 1775. Shorter, it urged the inhabitants of Canada not to side against the revolutionary forces. (The congress was aware that the British colonial government had already asked the Canadians to resist the call of the revolutionaries.)

On May 22, 1775, Bishop of Quebec Jean-Olivier Briand

Jean-Olivier Briand

Jean-Olivier Briand was the Bishop of the Roman Catholic diocese of Quebec from 1766 to 1784.He was ordained as a priest in 1739 and left for Canada in 1741 with another priest, Abbé René-Jean Allenou de Lavillangevin and the newly appointed bishop of Quebec, Henri-Marie Dubreil de Pontbriand, in...

sent out a mandement asking the Canadians to close their ears to the call of the "rebels" and defend their country and their king against the invasion.

Although both the British and the revolutionaries succeeded at recruiting Canadian men for militia, the majority of the people chose not to get involved in the conflict.

In 1778, Frederick Haldimand

Frederick Haldimand

Sir Frederick Haldimand, KB was a military officer best known for his service in the British Army in North America during the Seven Years' War and the American Revolutionary War...

became governor in replacement of Guy Carleton. (He served up until 1786, when Guy Carleton (now Lord Dorchester) returned as governor.)

Resumption of the reform movement (1784)

Soon after the war, which ended with the signing of the Treaty of ParisTreaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain on the one hand and the United States of America and its allies on the other. The other combatant nations, France, Spain and the Dutch Republic had separate agreements; for details of...

in 1783, the constitutional question resurfaced.

In July 1784, Pierre du Calvet

Pierre du Calvet

Pierre du Calvet was a Montreal trader, justice of the peace, political prisoner and epistle writer of French Huguenot origin.- Family :...

, a rich French merchant established in Montreal, published a pamphlet entitled Appel à la justice de l'État (Call to the Justice of the State) in London. Printed in French, the document is the first plea in favour of a constitutional reform in Canada. Du Calvet, imprisoned at the same time and for the same reasons as Fleury Mesplet and Valentine Jautard, both suspected of symphatizing and collaborating with the American revolutionaries during the war, undertook to have the injustice committed towards him be publicly known by publishing The Case of Peter du Calvet and, a few months later, his Appel à la justice de l'État.

On November 24, 1784, two petition for a house of assembly, one signed by 1436 "New Subjects" (Canadians) and another signed by 855 "Old Subjects" (British), were sent to the king of Great Britain. The first petition contained 14 demands. "A Plan for a House of Assembly" was also sketched in the same month of November. In December, "An Address to His Majesty in opposition to the House of Assembly and a list of Objections" were printed by the press of Fleury Mesplet

Fleury Mesplet

Fleury Mesplet was a French-born Canadian printer.Born in Marseille and apprenticed in Lyon, he emigrated to London in 1773 where he set up shop in Covent Garden. In 1774 he emigrated to Philadelphia; it is thought that he may have been persuaded to do so by Benjamin Franklin...

in Montreal. The main objection to the house of assembly was that the colony was not, according to its signatories, in a position to be taxed.

At the time the November 24 petition was submitted to the king, numerous United Empire Loyalists

United Empire Loyalists

The name United Empire Loyalists is an honorific given after the fact to those American Loyalists who resettled in British North America and other British Colonies as an act of fealty to King George III after the British defeat in the American Revolutionary War and prior to the Treaty of Paris...

were already seeking refuge in Quebec and Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

. In Quebec, the newly arrived settlers contributed to increase the number of people voicing for a rapid constitutional reform. In Nova Scotia, the immigrants demanded a separate colony.

Parliamentary constitution project (1789)

In 1786, the British government appointed Guy CarletonGuy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester

Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester, KB , known between 1776 and 1786 as Sir Guy Carleton, was an Irish-British soldier and administrator...

, as "governor-in-chief" and also governor of each of the four colonies. Carleton, now Lord Dorchester, had been British commander in Canada and governor of Quebec during the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

. When he returned as governor, he was already informed that the arrival of the Loyalists would require changes.

On October 20, 1789, Home Secretary William Wyndham Grenville wrote a private and secret letter to Carleton, informing him of the plans of the king's counsellors to modify Canada's constitution. The letter leaves little doubt as to the influence that American independence and the taking of the Bastille

Storming of the Bastille

The storming of the Bastille occurred in Paris on the morning of 14 July 1789. The medieval fortress and prison in Paris known as the Bastille represented royal authority in the centre of Paris. While the prison only contained seven inmates at the time of its storming, its fall was the flashpoint...

(which had just occurred in July) had on the decision. In the first paragraph, Grenville writes: "I am persuaded that it is a point of true Policy to make these Concessions at a time when they may be received as matter of favour, and when it is in Our own power to regulate and direct the manner of applying them, rather than to wait 'till they shall be extorted from Us by a necessity which shall neither leave Us any discretion in the form, nor any merit in the substance of what we give."

Grenville prepared the constitution in August 1789. But he was appointed to the House of Lords before he could submit his project to the House of Commons. Thus, Prime Minister William Pitt

William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger was a British politician of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He became the youngest Prime Minister in 1783 at the age of 24 . He left office in 1801, but was Prime Minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806...

did it in his place.

British merchants established in Quebec sent Adam Lymburner to Britain to present their objections. They objected to the creation of two provinces, suggested an increase in the number of representatives, asked for elections every three years (instead of seven), and requested an electoral division which would have overrepresented the Old Subjects by granting more representatives to the populations of the cities.

Lymburner's revisions were opposed by Whigs such as Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox PC , styled The Honourable from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned thirty-eight years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries and who was particularly noted for being the arch-rival of William Pitt the Younger...

, and in the end only the suggestions related to the frequency of elections and the number of representatives were retained.

Constitutional Act (1791)

On June 10, 1791, the Constitutional Act was enacted in London and gave Canada its first parliamentary constitution. Containing 50 articles, the act brought the following changes:- The Province of Quebec was divided into two distinct provinces, Province of Lower CanadaLower CanadaThe Province of Lower Canada was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence...

(present-day Quebec) and Province of Upper CanadaUpper CanadaThe Province of Upper Canada was a political division in British Canada established in 1791 by the British Empire to govern the central third of the lands in British North America and to accommodate Loyalist refugees from the United States of America after the American Revolution...

(present-day Ontario). - Each province was given an elected Legislative Assembly, an appointed Legislative Council, and an appointed Executive Council.

- Upper Canada was to be administered by a lieutenant governor appointed by the governor general, while Lower Canada was to be administered by a direct representative of the governor general.

- The Legislative Councils were to be established with no fewer than seven members in Upper Canada and fifteen members in Lower Canada. The members were to hold their seat for life.

- The Legislative Assembly was to be established with no less than sixteen members in Upper Canada and fifty members in Lower Canada.

- The governor was given the power to appoint the speaker of the Legislative Assembly, to fix the time and place of the elections and to give or withhold assent to bills.

- Provisions were made to allot clergy reserves to the Protestant churches in each province.

This partition ensured that Loyalists would constitute a majority in Upper Canada and allow for the application of exclusively British laws in this province. As soon as the province was divided, a series of acts were passed to abolish the French civil code in Upper Canada. In Lower Canada, the coexistence of French civil law and English criminal law continued.

Although it solved the immediate problems related to the settlement of the Loyalists in Canada, the new constitution brought a whole new set of political problems which were rooted in the constitution. Some of these problems were common to both provinces, while others were unique to Lower Canada or Upper Canada. The problems that eventually affected both provinces were:

- The Legislative Assemblies did not have full control over the revenues of the provinces

- The Executive and Legislative Councils were not responsible to the Legislative Assembly

In the two provinces, a movement for constitutional reform took shape within the majority party, the Parti canadien

Parti canadien

The Parti canadien or Parti patriote was a political party in what is now Quebec founded by members of the liberal elite of Lower Canada at the beginning of the 19th century...

of Lower Canada and the Reformers of Upper Canada. Leader of the Parti Canadien, Pierre-Stanislas Bédard was the first politician of Lower Canada to formulate a project of reform to put an end to the opposition between the elected Legislative Assembly and the Governor and his Council which answered only the Colonial Office

Secretary of State for the Colonies

The Secretary of State for the Colonies or Colonial Secretary was the British Cabinet minister in charge of managing the United Kingdom's various colonial dependencies....

in London. Putting forward the idea of ministerial responsibility, he proposed that the members of the Legislative Council be appointed by the Governor on the recommendation of the elected House.

Union Bill (1822)

In 1822, the Secretary of Colonial Office Lord BathurstHenry Bathurst, 3rd Earl Bathurst

Henry Bathurst, 3rd Earl Bathurst KG PC was a British politician.-Background and education:Lord Bathurst was the elder son of Henry Bathurst, 2nd Earl Bathurst, by his wife Tryphena, daughter of Thomas Scawen...

and his under-secretary Robert John Wilmot-Horton secretly submitted a bill to British House of Commons which projected the legislative union of the two Canadian provinces. Two months after the adjournment of the discussions on the bill, the news arrived in Lower Canada and caused a sharp reaction.

Supported by Governor Dalhousie, anglophone petitioners from the Eastern Townships, Quebec City and Kingston, the bill submitted in London provided, among other things, that each of the two sections of the new united province would have a maximum of 60 representatives, which would have put the French-speaking majority of Lower Canada in a position of minority in the new Parliament.

The mobilization of the citizens of Lower Canada and Upper Canada began in late summer and petitions in opposition to the project were prepared. The subject was discussed as soon as the session at the Parliament of Lower Canada opened on January 11, 1823. Ten days later, on January 21, the Legislative Assembly adopted a resolution authorizing a Lower Canadian delegation to go to London in order to officially present the quasi-unanimous opposition of the representatives of Lower Canada to the project of union. Exceptionally, even the Legislative Council gave its support to this resolution, with a majority of one vote. Having in their possession a petition of some 60 000 signatures, the Speaker of the House of Assembly, Louis-Joseph Papineau

Louis-Joseph Papineau

Louis-Joseph Papineau , born in Montreal, Quebec, was a politician, lawyer, and the landlord of the seigneurie de la Petite-Nation. He was the leader of the reformist Patriote movement before the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837–1838. His father was Joseph Papineau, also a famous politician in Quebec...

, as well as John Neilson

John Neilson

John Neilson was a Scots-Quebecer editor of the newspaper La Gazette de Québec/The Quebec Gazette and a politician.- Biography :...

, Member of Parliament, went to London to present the opinion of the majority of the population which they represented.

Faced with the massive opposition of people most concerned with the bill, the British government finally gave up the union project submitted for adoption by its own Colonial Office.

Report of the Special Committee of the House of Commons (1828)

A Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Civil Government of Canada was appointed on May 2, 1828 "to enquire into the state of the civil government of Canada, as established by the Act 31 Geo. III., chap. 31, and to report their observations and opinions thereupon to the house."It reported on July 22 of the same year. It recommended against the union of Upper Canada and Lower Canada and in favour of constitutional and administrative reforms intended to prevent the recurrence of the abuses complained of in Lower Canada.

The Ninety-Two Resolutions of the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada (1834)

These constituted a sort of declaration of rights on the part of the patriote party. They were drafted by A. N. Morin, but were inspired by Louis-Joseph PapineauLouis-Joseph Papineau

Louis-Joseph Papineau , born in Montreal, Quebec, was a politician, lawyer, and the landlord of the seigneurie de la Petite-Nation. He was the leader of the reformist Patriote movement before the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837–1838. His father was Joseph Papineau, also a famous politician in Quebec...

. They demanded the application of the elective principle to the political institutions of the province, after the American model; but did not advocate, in any explicit way, the introduction of responsible government. Lord Aylmer, the governor-general of Canada at that time, in an analysis of the resolutions, maintained that "eleven of them represented the truth; six contained truth mixed with falsehood; sixteen were wholly false; seventeen were doubtful; twelve were ridiculous; seven repetitions; fourteen consisted of abuse; four were both false and seditious; and the remaining five were indifferent."

Royal Commission for the Investigation of all Grievances Affecting His Majesty's Subjects of Lower Canada (1835)

Following the adoption of the Ninety-Two Resolutions, the Governor Gosford arrived in Lower Canada to replace governor Aylmer. Gosford set up royal commission of inquiry conducted by Charles E. Gray and George GippsGeorge Gipps

Sir George Gipps was Governor of the colony of New South Wales, Australia, for eight years, between 1838 and 1846. His governorship was during a period of great change for New South Wales and Australia, as well as for New Zealand, which was administered as part of New South Wales for much of this...

. The Royal Commission for the Investigation of all Grievances Affecting His Majesty's Subjects of Lower Canada reported on November 17, 1836 and the Ten resolutions of John Russel were mostly based on it.

John Russell's Ten Resolutions (1837)

On March 2, 1837, John Russell, then British Colonial Secretary, submits ten resolutions to the Parliament in response to the ninety-two resolutions. The Parliament adopts the resolutions on March 6.Most of the recommendations brought forth by the elected assemblies were systematically ignored by the Executive Councils. This was particularly true in Lower Canada with an assembly consisting mostly of French-Canadian members of the Parti Patriote. This impasse created considerable tensions between the French-Canadian political class and the British government. In 1834 Louis-Joseph Papineau

Louis-Joseph Papineau

Louis-Joseph Papineau , born in Montreal, Quebec, was a politician, lawyer, and the landlord of the seigneurie de la Petite-Nation. He was the leader of the reformist Patriote movement before the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837–1838. His father was Joseph Papineau, also a famous politician in Quebec...

, a French-Canadian political leader, submitted a document entitled the Ninety-Two Resolutions

Ninety-Two Resolutions

The Ninety-Two Resolutions were drafted by Louis-Joseph Papineau and other members of the Parti patriote of Lower Canada in 1834. The resolutions were a long series of demands for political reforms in the British-governed colony....

to the Crown. The document requested vast democratic reforms such as the transfer of power to elected representatives. The reply came three years later in the form of the Russell Resolutions, which not only rejected the 92 Resolutions but also revoked one of the assembly's few real powers, the power to pass its own budget. This rebuff heightened tensions and escalated into armed rebellions in 1837 and 1838, known as the Lower Canada Rebellion

Lower Canada Rebellion

The Lower Canada Rebellion , commonly referred to as the Patriots' War by Quebeckers, is the name given to the armed conflict between the rebels of Lower Canada and the British colonial power of that province...

. The uprisings were short-lived, however, as British troops quickly defeated the rebels and burned their villages in reprisal.

The rebellion was also contained by the Catholic clergy, which, by representing the only French-Canadian institution with independent authority, exercised a tremendous influence over its constituents. During and after the rebellions Catholic priests and the bishop of Montreal told their congregants that questioning established authority was a sin that would prevent them from receiving the sacraments. The Church refused to give Christian burials to supporters of the rebellion. With liberal and progressive forces suppressed in Lower Canada, the Catholic Church's influence dominated the French-speaking side of French Canadian/British relations from the 1840s until the Quiet Revolution

Quiet Revolution

The Quiet Revolution was the 1960s period of intense change in Quebec, Canada, characterized by the rapid and effective secularization of society, the creation of a welfare state and a re-alignment of politics into federalist and separatist factions...

secularized Quebec society in the 1960s.

Suspension of the Constitutional Act (1838)

Approximately four months after having proclaimed martial lawMartial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

in the district of Montreal, Governor Gosford suspends, on March 27, 1838, the Constitutional Act of 1791 and sets up a Special Council

Special Council of Lower Canada

The Special Council of Lower Canada was an appointed body which administered Lower Canada until the Union Act of 1840 created the Province of Canada. Following the Lower Canada Rebellion, on March 27, 1838, the Constitutional Act of 1791 was suspended and both the Legislative Assembly and...

.

Report on the Affairs of British North America (1839)

Following the rebellions, in May 1838, the British government sent Governor General Lord Durham to Lower and Upper Canada in order to investigate the uprisings and to bring forth solutions. His recommendations were formulated in what is known as "Lord Durham's Report" and suggested the forced union of the Canadas with the expressed purpose of "making [Lower Canada] an English Province [that] should never again be placed in any hands but those of an English population." Doing so, he claimed, would speed up the assimilation of the French-Canadian population, "a people with no history, and no literature" into a homogenized English population. This would prevent what he considered to be ethnic conflicts.Act of Union (1840)

- The provinces of Upper Canada and Lower Canada were unified to form the Province of Canada;

- The parliamentary institutions of the former provinces were abolished and replaced by a single Parliament of Canada;

- Each of the two sections of the province corresponding to the old provinces were allotted an equal number of elected representatives;

- The old electoral districts were redrawn in order to overrepresent the population of former Upper Canada and underrepresent the population of former Lower Canada;

- The candidates to the legislative elections had to prove from then on that they were the owners of a land worth at least 500 pounds sterling;

- The mandates, proclamations, laws, procedures and journals had from then on to be published and archived in the English language only;

As a result, Lower Canada and Upper Canada, with its enormous debt, were united in 1840, and French was banned in the legislature for about eight years. Eight years later, an elected and responsible government

Responsible government