.gif)

Bloody Sunday (1972)

Encyclopedia

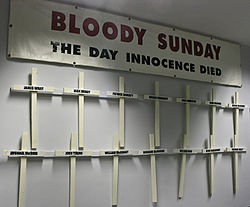

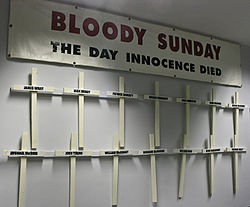

Bloody Sunday —sometimes called the Bogside Massacre—was an incident on 30 January 1972 in the Bogside

area of Derry

, Northern Ireland

, in which twenty-six unarmed civil rights

protesters and bystanders were shot by soldiers of the British Army

. Thirteen males, seven of whom were teenagers, died immediately or soon after, while the death of another man four and a half months later was attributed to the injuries he received on that day. Two protesters were also injured when they were run down by army vehicles. Five of those wounded were shot in the back. The incident occurred during a Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

march; the soldiers involved were the First Battalion of the Parachute Regiment (1 Para).

Two investigations have been held by the British government. The Widgery Tribunal, held in the immediate aftermath of the event, largely cleared the soldiers and British authorities of blame—Widgery described the soldiers' shooting as "bordering on the reckless"—but was criticised as a "whitewash

", including by Jonathan Powell, chief of staff to former prime minister Tony Blair

. The Saville Inquiry, chaired by Lord Saville of Newdigate

, was established in 1998 to reinvestigate the events. Following a twelve-year inquiry, Saville's report was made public on 15 June 2010, and contained findings of fault that could re-open the controversy, and potentially lead to criminal investigations for some soldiers involved in the killings. The report found that all of those shot were unarmed, and that the killings were both "unjustified and unjustifiable." On the publication of the Saville report the British prime minister, David Cameron

, made a formal apology on behalf of the United Kingdom.

The Provisional Irish Republican Army

's (IRA) campaign against the partition of Ireland

had begun in the two years prior to Bloody Sunday, but public perceptions of the day boosted the status of, and recruitment into, the organisation enormously. Bloody Sunday remains among the most significant events in the Troubles

of Northern Ireland, chiefly because it was carried out by the British army and not paramilitaries, in full view of the public and the press.

(NICRA) to mount a non-violent campaign for change. Following attacks on civil rights marchers by Protestant loyalists, as well as members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary

(RUC), anger and violence mounted. In 1969 the Battle of the Bogside

broke out in the aftermath of disturbances following an Apprentice Boys of Derry

march. The residents of the nationalist Bogside erected barricades around the area to resist police incursions, and, after three days of rioting when the RUC had proved unable to restore order, the government of Northern Ireland requested the deployment of the British Army.

While initially welcomed by the Catholics as a neutral force compared to the RUC, relations between the nationalists and the Army soon deteriorated. On 8 July 1971 two rioters, Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beattie, were shot dead in the Bogside by soldiers in disputed circumstances. Soldiers claimed the pair were armed, which was denied by local people, and moderate nationalists including John Hume

and Gerry Fitt

walked out of the Parliament of Northern Ireland

in protest. A British Army memorandum states that as a result of this the situation "changed overnight", with the Provisional IRA's campaign in the city beginning at that time after previously being regarded as "quiescent".

In response to escalating levels of violence across Northern Ireland, internment without trial

was introduced on 9 August 1971. In a quid pro quo

gesture to nationalists, all marches and parades were banned, including the flashpoint march by the Apprentice Boys of Derry which was due to take place on 12 August. There was disorder across Northern Ireland following the introduction of internment, with 21 people being killed in three days of rioting. On 10 August Bombardier Paul Challenor became the first soldier to be killed by the Provisional IRA in Derry, when he was shot by a sniper on the Creggan

estate. A further six soldiers had been killed in Derry by mid-December 1971. 1,932 rounds were fired at the British Army, who also faced 211 explosions and 180 nail bomb

s and who fired 364 rounds in return.

Provisional IRA activity also increased across Northern Ireland with thirty British soldiers being killed in the remaining months of 1971, in contrast to the ten soldiers killed during the pre-internment period of the year. Both the Official IRA

and Provisional IRA had established "no-go" areas for the British Army and RUC in Derry through the use of barricades. By the end of 1971, 29 barricades were in place to prevent access to what was known as Free Derry

, 16 of them impassable even to the British Army's one-ton armoured vehicles. IRA members openly mounted roadblocks in front of the media, and daily clashes took place between nationalist youths and the British Army at a spot known as "aggro corner". Due to rioting and damage to shops caused by incendiary device

s, an estimated total of worth of damage had been done to local businesses.

In January 1972 the NICRA intended, despite the ban, to organise a march in Derry to protest against internment. The authorities who knew of the proposed march decided to allow it to proceed in the nationalist areas of the city, but to stop it from reaching Guildhall Square

, as planned by the organisers. Major General Robert Ford

, then Commander of Land Forces in Northern Ireland, ordered that 1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment (1 PARA) should travel to Derry to be used to arrest possible rioters during the march. 1 PARA arrived in Derry on the morning of Sunday 30 January 1972 and took up positions in the city.

Many details of the day's events are in dispute, with no agreement even on the number of marchers present that day. The organisers, "Insight", claimed that there were 30,000 marchers; Lord Widgery

Many details of the day's events are in dispute, with no agreement even on the number of marchers present that day. The organisers, "Insight", claimed that there were 30,000 marchers; Lord Widgery

, in his now discredited tribunal, said that there were only 3,000 to 5,000. In The Road To Bloody Sunday, local GP

Dr. Raymond McClean estimated the crowd as 15,000, which is the figure that was used by Bernadette Devlin McAliskey

in Parliament.

Numerous books and articles have been written and documentary films have been made on the subject.

, but because of army barricades designed to reroute the march it was redirected to Free Derry

Corner. A group of teenagers broke off from the march and persisted in pushing the barricade and marching on the Guildhall. They attacked the British army

barricade

with stones. At this point, a water cannon, tear gas and rubber bullets were used to disperse the rioters. Such confrontations between soldiers and youths were common, though observers reported that the rioting was not intense. Two civilians, Damien Donaghy and John Johnston were shot and wounded by soldiers on William Street who claimed the former was carrying a black cylindrical object.

At a certain point, reports of an IRA sniper operating in the area were allegedly given to the Army command centre. At Brigade gave the British Parachute Regiment permission to go in to the Bogside. The order to fire live rounds was given, and one young man was shot and killed when he ran down Chamberlain Street away from the advancing troops. This first fatality, Jackie Duddy, was among a crowd who were running away. He was running alongside a priest, Father Edward Daly, when he was shot in the back. Continuing violence by British troops escalated, and eventually the order was given to mobilise the troops in an arrest operation, chasing the tail of the main group of marchers to the edge of the field by Free Derry Corner.

Despite a cease-fire order from the army HQ, over a hundred rounds were fired directly into the fleeing crowds by troops under the command of Major Ted Loden. Twelve more were killed, many of them as they attempted to aid the fallen. Fourteen others were wounded, twelve by shots from the soldiers and two knocked down by armoured personnel carriers.

Thirteen people were shot and killed, with another man later dying of his wounds. The official army position, backed by the British Home Secretary

Thirteen people were shot and killed, with another man later dying of his wounds. The official army position, backed by the British Home Secretary

the next day in the House of Commons, was that the paratroopers had reacted to gun and nail bomb attacks from suspected IRA members. All eyewitnesses (apart from the soldiers), including marchers, local residents, and British and Irish journalists present, maintain that soldiers fired into an unarmed crowd, or were aiming at fleeing people and those tending the wounded, whereas the soldiers themselves were not fired upon. No British soldier was wounded by gunfire or reported any injuries, nor were any bullets or nail bombs recovered to back up their claims.

In the events that followed, irate crowds burned down the British embassy on Merrion Square

in Dublin. Anglo-Irish relations hit one of their lowest ebbs, with Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs

, Patrick Hillery

, going specially to the United Nations

in New York to demand UN involvement in the Northern Ireland "Troubles".

Although there were many IRA men—both Official

and Provisional—present at the protest, it is claimed they were all unarmed, apparently because it was anticipated that the paratroopers would attempt to "draw them out". March organizer and MP Ivan Cooper

had been promised beforehand that no armed IRA men would be near the march. One paratrooper who gave evidence at the Tribunal testified that they were told by an officer to expect a gunfight and "We want some kills". In the event, one man was witnessed by Father Edward Daly

and others haphazardly firing a revolver in the direction of the paratroopers. Later identified as a member of the Official IRA, this man was also photographed in the act of drawing his weapon, but was apparently not seen or targeted by the soldiers. Various other claims have been made to the Saville Inquiry about gunmen on the day.

The city's coroner

, retired British Army Major Hubert O'Neill, issued a statement on 21 August 1973, at the completion of the inquest

into the people killed. He declared:

Two days after Bloody Sunday, the Westminster Parliament adopted a resolution for a tribunal

into the events of the day, resulting in Prime Minister

Edward Heath

commissioning the Lord Chief Justice

, Lord Widgery

to undertake it. Many witnesses intended to boycott

the tribunal as they lacked faith in Widgery's impartiality, but were eventually persuaded to take part. Widgery's quickly produced report—completed within ten weeks (10 April) and published within eleven (19 April)—supported the Army's account of the events of the day. Among the evidence presented to the tribunal were the results of paraffin tests, used to identify lead

residues from firing weapons, and that nail bombs had been found on the body of one of those killed. Tests for traces of explosives on the clothes of eleven of the dead proved negative, while those of the remaining man could not be tested as they had already been washed. Most Irish people and witnesses to the event disputed the report's conclusions and regarded it as a whitewash. It has been argued that firearms residue on some deceased may have come from contact with the soldiers who themselves moved some of the bodies, or that the presence of lead on the hands of one (James Wray) was easily explained by the fact that his occupation involved the use of lead-based solder

. In fact, in 1992, John Major

, writing to John Hume

stated:

Following the events of Bloody Sunday Bernadette Devlin, an Independent Socialist nationalist MP from Northern Ireland, expressed anger at what she perceived as government attempts to stifle accounts being reported about the day. Having witnessed the events firsthand, she was later infuriated that she was consistently denied the chance to speak in Parliament about the day, although parliamentary convention decreed that any MP witnessing an incident under discussion would be granted an opportunity to speak about it in the House.

Following the events of Bloody Sunday Bernadette Devlin, an Independent Socialist nationalist MP from Northern Ireland, expressed anger at what she perceived as government attempts to stifle accounts being reported about the day. Having witnessed the events firsthand, she was later infuriated that she was consistently denied the chance to speak in Parliament about the day, although parliamentary convention decreed that any MP witnessing an incident under discussion would be granted an opportunity to speak about it in the House.

Devlin punched Reginald Maudling

, the Secretary of State for the Home Department in the Conservative

government, when he made a statement to Parliament on the events of Bloody Sunday stating that the British Army had fired only in self-defence.

She was temporarily suspended from Parliament as a result of the incident.

In January 1997, the United Kingdom television station Channel 4

carried a news report that suggested that members of the Royal Anglian Regiment

had also opened fire on the protesters and could have been responsible for three of the fourteen deaths.

On 29 May 2007 it was reported that General Sir Mike Jackson

, second-in-command of 1 Para on Bloody Sunday, said: "I have no doubt that innocent people were shot". This was in sharp contrast to his insistence, for more than 30 years, that those killed on the day had not been innocent.

John Major

rejected John Hume

's requests for a public inquiry

into the killings, his successor, Tony Blair

, decided to start one. A second commission of inquiry, chaired by Lord Saville, was established in January 1998 to re-examine 'Bloody Sunday'. The other judges were John Toohey QC

, a former Justice

of the High Court of Australia

who had worked on Aboriginal issues (he replaced New Zealander Sir Edward Somers QC, who retired from the Inquiry in 2000 for personal reasons), and Mr Justice William Hoyt

QC, former Chief Justice

of New Brunswick

and a member of the Canadian Judicial Council

. The hearings were concluded in November 2004, and the report was published 15 June 2010. The Saville Inquiry was a more comprehensive study than the Widgery Tribunal, interviewing a wide range of witnesses, including local residents, soldiers, journalists and politicians. Lord Saville declined to comment on the Widgery report and made the point that the Saville Inquiry was a judicial inquiry into 'Bloody Sunday', not the Widgery Tribunal.

Evidence given by Martin McGuiness, a senior member of Sinn Féin

and now the deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, to the inquiry stated that he was second-in-command of the Derry City brigade of the Provisional IRA and was present at the march. He did not answer questions about where he had been staying because he said it would compromise the safety of the individuals involved.

A claim was made at the Saville Inquiry that McGuinness was responsible for supplying detonators for nail bombs on Bloody Sunday. Paddy Ward claimed he was the leader of the Fianna Éireann

, the youth wing of the IRA in January 1972. He claimed McGuinness, the second-in-command of the IRA in the city at the time, and another anonymous IRA member gave him bomb parts on the morning of 30 January, the date planned for the civil rights march. He said his organisation intended to attack city-centre premises in Derry on the day when civilians were shot dead by British soldiers. In response McGuinness rejected the claims as "fantasy", while Gerry O'Hara, a Sinn Féin councillor in Derry stated that he and not Ward was the Fianna leader at the time.

Many observers allege that the Ministry of Defence

acted in a way to impede the inquiry. Over 1,000 army photographs and original army helicopter video footage were never made available. Additionally, guns used on the day by the soldiers that could have been evidence in the inquiry were lost by the MoD. The MoD claimed that all the guns had been destroyed, but some were subsequently recovered in various locations (such as Sierra Leone

and Beirut

) despite the obstruction.

By the time the inquiry had retired to write up its findings, it had interviewed over 900 witnesses, over seven years, making it the biggest investigation in British legal

history. The cost of this process has drawn criticism; as of the publication of the Saville Report being .

The inquiry was expected to report in late 2009 but was delayed until after the general election on 6 May 2010.

The inquiry was expected to report in late 2009 but was delayed until after the general election on 6 May 2010.

The report of the inquiry was published on 15 June 2010. The report concluded, "The firing by soldiers of 1 PARA on Bloody Sunday caused the deaths of 13 people and injury to a similar number, none of whom was posing a threat of causing death or serious injury." Saville stated that British paratroopers "lost control", fatally shooting fleeing civilians and those who tried to aid the civilians who had been shot by the British soldiers. The report stated that British soldiers had concocted lies in their attempt to hide their acts. Saville stated that the civilians had not been warned by the British soldiers that they intended to shoot. The report states, contrary to the previously established belief, that no stones and no petrol bombs were thrown by civilians before British soldiers shot at them, and that the civilians were not posing any threat.

The report concluded that an Official IRA sniper fired on British soldiers, albeit on the balance of evidence his shot was fired after the Army shots that wounded Damien Donaghey and John Johnston. The Inquiry rejected the sniper's account that this shot had been made in reprisal, stating the view that he and another Official IRA member had already been in position, and the shot had probably been fired simply because the opportunity had presented itself. Ultimately, the Saville Inquiry was inconclusive on Martin McGuiness' role due to a lack of certainty over his movements, concluding that while he was "engaged in paramilitary activity" during Bloody Sunday, and had probably been armed with a Thompson submachine gun

, there was insufficient evidence to make any finding other than they were "sure that he did not engage in any activity that provided any of the soldiers with any justification for opening fire".

Harold Wilson

Harold Wilson

, then the Leader of the Opposition

in the Commons, reiterated his belief that a united Ireland

was the only possible solution to Northern Ireland's Troubles. William Craig, then Stormont Home Affairs Minister, suggested that the west bank of Derry should be ceded to the Republic of Ireland

.

When it was deployed on duty in Northern Ireland, the British Army was welcomed by Roman Catholics as a neutral force there to protect them from Protestant mobs, the Royal Ulster Constabulary

(RUC) and the B-Specials

. After Bloody Sunday many Catholics turned on the British army

, seeing it no longer as their protector but as their enemy. Young nationalists

became increasingly attracted to violent republican

groups. With the Official IRA

and Official Sinn Féin having moved away from mainstream Irish republicanism towards Marxism

, the Provisional IRA began to win the support of newly radicalised, disaffected young people.

In the following twenty years, the Provisional Irish Republican Army

and other smaller republican groups such as the Irish National Liberation Army

(INLA) mounted an armed campaign

against the British, by which they meant the RUC, the British Army, the Ulster Defence Regiment

(UDR) of the British Army (and, according to their critics, the Protestant and unionist establishment). With rival paramilitary organisations appearing in both the nationalist/republican and Irish unionist

/Ulster loyalist communities (the Ulster Defence Association

, Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), etc. on the loyalist side), the Troubles cost the lives of thousands of people. Incidents included the killing of three members of a pop band, the Miami Showband

, by a gang including members of the UVF who were also members of the local army regiment, the UDR, and in uniform at the time, and the killing by the Provisionals of eighteen members of the Parachute Regiment in the Warrenpoint Ambush

-seen by some as revenge for Bloody Sunday.

With the official cessation of violence by some of the major paramilitary organisations and the creation of the power-sharing executive at Stormont

in Belfast

under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, the Saville Inquiry's re-examination of the events of that day is widely hoped to provide a thorough account of the events of Bloody Sunday.

In his speech to the House of Commons on the Inquiry, British Prime Minister David Cameron

stated: "These are shocking conclusions to read and shocking words to have to say. But you do not defend the British Army by defending the indefensible." He acknowledged that all those who died were unarmed when they were killed by British soldiers and that a British soldier had fired the first shot at civilians. He also said that this was not a premeditated action, though "there was no point in trying to soften or equivocate" as "what happened should never, ever have happened". Cameron then apologised on behalf of the British Government by saying he was "deeply sorry".

A survey conducted by Angus Reid Public Opinion

in June 2010 found that 61 per cent of Britons and 70 per cent of Northern Irish agreed with Cameron’s apology for the Bloody Sunday events.

Stephen Pollard, solicitor representing several of the soldiers, said on 15 June 2010 that Saville had cherry-picked the evidence and did not have justification for his findings.

The incident has been commemorated by Irish band, U2

The incident has been commemorated by Irish band, U2

, in their 1983 protest song

"Sunday Bloody Sunday

".Bloody Sunday in popular culture 15 June 2010. www.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2010 June 20.

The John Lennon

album Some Time in New York City

features a song entitled "Sunday Bloody Sunday", inspired by the incident, as well as the song "The Luck of the Irish", which dealt more with the Irish conflict in general. Lennon, who was of Irish descent, also spoke at a protest in New York

in support of the victims and families of Bloody Sunday.

The Roy Harper

song "All Ireland" from the album 'Lifemask

', written in the days following the incident, is critical of the military but takes a long term view with regard to a solution. In Harper's book ('The Passions Of Great Fortune'), his comment on the song ends '..there must always be some hope that the children of 'Bloody Sunday', on both sides, can grow into some wisdom'.

Paul McCartney

(also of Irish descent) issued a single shortly after Bloody Sunday titled "Give Ireland Back to the Irish

", expressing his views on the matter. It was one of few McCartney solo songs to be banned by the BBC

.

Black Sabbath

's Geezer Butler

(also of Irish descent) wrote the lyrics to the Black Sabbath song "Sabbath Bloody Sabbath" on the album of the same name in 1973. Butler stated, "… the Sunday Bloody Sunday thing had just happened in Ireland, when the British troops opened fire on the Irish demonstrators... So I came up with the title ‘Sabbath Bloody Sabbath,’ and sort of put it in how the band was feeling at the time, getting away from management, mixed with the state Ireland was in."

Christy Moore

's song "Minds Locked Shut" on the album "Graffiti Tongue" is all about the events of the day, and names the dead civilians.

The Celtic metal

band Cruachan

addressed the incident in a song "Bloody Sunday" from their 2004 album Folk-Lore

.

The events of the day have been dramatised in the two 2002 television

dramas, Bloody Sunday (starring James Nesbitt

) and Sunday by Jimmy McGovern

.

Brian Friel

's 1973 play The Freedom of the City

deals with the incident from the viewpoint of three civilians.

Irish poet Thomas Kinsella

's 1972 poem Butcher's Dozen is a satirical and angry response to the Widgery Tribunal and the events of Bloody Sunday.

Willie Doherty

, a Derry-born artist has amassed a large body of work which addresses the troubles in Northern Ireland. "30 January 1972" deals specifically with the events of Bloody Sunday.

In mid-2005, the play Bloody Sunday: Scenes from the Saville Inquiry

, a dramatisation based on the Saville Inquiry, opened in London, and subsequently travelled to Derry and Dublin. The writer, journalist Richard Norton-Taylor

, distilled four years of evidence into two hours of stage performance by Tricycle Theatre

. The play received glowing reviews in all the British broadsheets, including The Times: "The Tricycle's latest recreation of a major inquiry is its most devastating"; The Daily Telegraph: "I can't praise this enthralling production too highly ... exceptionally gripping courtroom drama"; and The Independent: "A necessary triumph".

The Wolfe Tones, an Irish rebel music

band, wrote a song also called "Sunday Bloody Sunday" about the event.

Swedish troubadour Fred Åkerström

wrote a song called "Den 30/1-72" about the incident.

In October 2010, T with the Maggies

released the song Domhnach na Fola (Irish

for Bloody Sunday), written by Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh

and Tríona Ní Dhomhnaill

on their debut album

.

Bogside

The Bogside is a neighbourhood outside the city walls of Derry, Northern Ireland. The area has been a focus point for many of the events of The Troubles, from the Battle of the Bogside and Bloody Sunday in the 1960s and 1970s...

area of Derry

Derry

Derry or Londonderry is the second-biggest city in Northern Ireland and the fourth-biggest city on the island of Ireland. The name Derry is an anglicisation of the Irish name Doire or Doire Cholmcille meaning "oak-wood of Colmcille"...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

, in which twenty-six unarmed civil rights

Civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a worldwide political movement for equality before the law occurring between approximately 1950 and 1980. In many situations it took the form of campaigns of civil resistance aimed at achieving change by nonviolent forms of resistance. In some situations it was...

protesters and bystanders were shot by soldiers of the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

. Thirteen males, seven of whom were teenagers, died immediately or soon after, while the death of another man four and a half months later was attributed to the injuries he received on that day. Two protesters were also injured when they were run down by army vehicles. Five of those wounded were shot in the back. The incident occurred during a Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association was an organisation which campaigned for equal civil rights for the all the people in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s...

march; the soldiers involved were the First Battalion of the Parachute Regiment (1 Para).

Two investigations have been held by the British government. The Widgery Tribunal, held in the immediate aftermath of the event, largely cleared the soldiers and British authorities of blame—Widgery described the soldiers' shooting as "bordering on the reckless"—but was criticised as a "whitewash

Whitewash (censorship)

To whitewash is a metaphor meaning to gloss over or cover up vices, crimes or scandals or to exonerate by means of a perfunctory investigation or through biased presentation of data. It is especially used in the context of corporations, governments or other organizations.- Etymology :Its first...

", including by Jonathan Powell, chief of staff to former prime minister Tony Blair

Tony Blair

Anthony Charles Lynton Blair is a former British Labour Party politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2 May 1997 to 27 June 2007. He was the Member of Parliament for Sedgefield from 1983 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007...

. The Saville Inquiry, chaired by Lord Saville of Newdigate

Mark Saville, Baron Saville of Newdigate

Mark Oliver Saville, Baron Saville of Newdigate PC, QC is a British judge and former Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom.-Early life:...

, was established in 1998 to reinvestigate the events. Following a twelve-year inquiry, Saville's report was made public on 15 June 2010, and contained findings of fault that could re-open the controversy, and potentially lead to criminal investigations for some soldiers involved in the killings. The report found that all of those shot were unarmed, and that the killings were both "unjustified and unjustifiable." On the publication of the Saville report the British prime minister, David Cameron

David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron is the current Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, First Lord of the Treasury, Minister for the Civil Service and Leader of the Conservative Party. Cameron represents Witney as its Member of Parliament ....

, made a formal apology on behalf of the United Kingdom.

The Provisional Irish Republican Army

Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army is an Irish republican paramilitary organisation whose aim was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and bring about a socialist republic within a united Ireland by force of arms and political persuasion...

's (IRA) campaign against the partition of Ireland

Partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland was the division of the island of Ireland into two distinct territories, now Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland . Partition occurred when the British Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1920...

had begun in the two years prior to Bloody Sunday, but public perceptions of the day boosted the status of, and recruitment into, the organisation enormously. Bloody Sunday remains among the most significant events in the Troubles

The Troubles

The Troubles was a period of ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland which spilled over at various times into England, the Republic of Ireland, and mainland Europe. The duration of the Troubles is conventionally dated from the late 1960s and considered by many to have ended with the Belfast...

of Northern Ireland, chiefly because it was carried out by the British army and not paramilitaries, in full view of the public and the press.

Background

In the late 1960s discrimination against the Catholic minority in electoral boundaries, voting rights, and the allocation of public housing led organisations such as Northern Ireland Civil Rights AssociationNorthern Ireland Civil Rights Association

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association was an organisation which campaigned for equal civil rights for the all the people in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s...

(NICRA) to mount a non-violent campaign for change. Following attacks on civil rights marchers by Protestant loyalists, as well as members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary

Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary was the name of the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2000. Following the awarding of the George Cross in 2000, it was subsequently known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC. It was founded on 1 June 1922 out of the Royal Irish Constabulary...

(RUC), anger and violence mounted. In 1969 the Battle of the Bogside

Battle of the Bogside

The Battle of the Bogside was a very large communal riot that took place during 12–14 August 1969 in Derry, Northern Ireland. The fighting was between residents of the Bogside area and the Royal Ulster Constabulary .The rioting erupted after the RUC attempted to disperse Irish nationalists who...

broke out in the aftermath of disturbances following an Apprentice Boys of Derry

Apprentice Boys of Derry

The Apprentice Boys of Derry is a Protestant fraternal society with a worldwide membership of over 80,000, founded in 1814. They are based in the city of Derry, Northern Ireland. However, there are Clubs and branches across Ireland, Great Britain and further afield...

march. The residents of the nationalist Bogside erected barricades around the area to resist police incursions, and, after three days of rioting when the RUC had proved unable to restore order, the government of Northern Ireland requested the deployment of the British Army.

While initially welcomed by the Catholics as a neutral force compared to the RUC, relations between the nationalists and the Army soon deteriorated. On 8 July 1971 two rioters, Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beattie, were shot dead in the Bogside by soldiers in disputed circumstances. Soldiers claimed the pair were armed, which was denied by local people, and moderate nationalists including John Hume

John Hume

John Hume is a former Irish politician from Derry, Northern Ireland. He was a founding member of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, and was co-recipient of the 1998 Nobel Peace Prize, with David Trimble....

and Gerry Fitt

Gerry Fitt

Gerard Fitt, Baron Fitt was a politician in Northern Ireland. He was a founder and the first leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party , a social democratic and Irish nationalist party.-Early years:...

walked out of the Parliament of Northern Ireland

Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended...

in protest. A British Army memorandum states that as a result of this the situation "changed overnight", with the Provisional IRA's campaign in the city beginning at that time after previously being regarded as "quiescent".

In response to escalating levels of violence across Northern Ireland, internment without trial

Operation Demetrius

Operation Demetrius began in Northern Ireland on the morning of Monday 9 August 1971. Operation Demetrius was launched by the British Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary and involved arresting and interning people accused of being paramilitary members...

was introduced on 9 August 1971. In a quid pro quo

Quid pro quo

Quid pro quo most often means a more-or-less equal exchange or substitution of goods or services. English speakers often use the term to mean "a favour for a favour" and the phrases with almost identical meaning include: "give and take", "tit for tat", "this for that", and "you scratch my back,...

gesture to nationalists, all marches and parades were banned, including the flashpoint march by the Apprentice Boys of Derry which was due to take place on 12 August. There was disorder across Northern Ireland following the introduction of internment, with 21 people being killed in three days of rioting. On 10 August Bombardier Paul Challenor became the first soldier to be killed by the Provisional IRA in Derry, when he was shot by a sniper on the Creggan

Creggan, Derry

Creggan is a large housing estate in Derry in Northern Ireland. It was the first housing estate built in Derry specifically to provide housing for the Catholic majority. It is situated on the outskirts of the city and is built on a hill. The name Creggan is derived from the Gaelic word creagán...

estate. A further six soldiers had been killed in Derry by mid-December 1971. 1,932 rounds were fired at the British Army, who also faced 211 explosions and 180 nail bomb

Nail bomb

The nail bomb is an anti-personnel explosive device packed with nails to increase its wounding ability. The nails act as shrapnel, leading almost certainly to greater loss of life and injury in inhabited areas than the explosives alone would. The nail bomb is also a type of flechette weapon...

s and who fired 364 rounds in return.

Provisional IRA activity also increased across Northern Ireland with thirty British soldiers being killed in the remaining months of 1971, in contrast to the ten soldiers killed during the pre-internment period of the year. Both the Official IRA

Official IRA

The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA is an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to create a "32-county workers' republic" in Ireland. It emerged from a split in the Irish Republican Army in December 1969, shortly after the beginning of "The Troubles"...

and Provisional IRA had established "no-go" areas for the British Army and RUC in Derry through the use of barricades. By the end of 1971, 29 barricades were in place to prevent access to what was known as Free Derry

Free Derry

Free Derry was a self-declared autonomous nationalist area of Derry, Northern Ireland, between 1969 and 1972. Its name was taken from a sign painted on a gable wall in the Bogside in January 1969 which read, “You are now entering Free Derry"...

, 16 of them impassable even to the British Army's one-ton armoured vehicles. IRA members openly mounted roadblocks in front of the media, and daily clashes took place between nationalist youths and the British Army at a spot known as "aggro corner". Due to rioting and damage to shops caused by incendiary device

Incendiary device

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices or incendiary bombs are bombs designed to start fires or destroy sensitive equipment using materials such as napalm, thermite, chlorine trifluoride, or white phosphorus....

s, an estimated total of worth of damage had been done to local businesses.

In January 1972 the NICRA intended, despite the ban, to organise a march in Derry to protest against internment. The authorities who knew of the proposed march decided to allow it to proceed in the nationalist areas of the city, but to stop it from reaching Guildhall Square

Guildhall, Derry

The Guildhall in Derry, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, is a building in which the elected members of Derry City Council meet. It was built in 1890....

, as planned by the organisers. Major General Robert Ford

Robert Ford (British Army officer)

General Sir Robert Cyril Ford GCB CBE is a former Adjutant-General to the Forces.-Military career:Born in Devon to John and Gladys Ford, Robert Ford was educated at Musgrave's College and was later commissioned into the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards in 1943. He served in North West Europe during...

, then Commander of Land Forces in Northern Ireland, ordered that 1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment (1 PARA) should travel to Derry to be used to arrest possible rioters during the march. 1 PARA arrived in Derry on the morning of Sunday 30 January 1972 and took up positions in the city.

Events of the day

John Widgery, Baron Widgery

John Passmore Widgery, Baron Widgery, OBE, TD, QC, PC was an English judge who served as Lord Chief Justice of England from 1971 to 1980...

, in his now discredited tribunal, said that there were only 3,000 to 5,000. In The Road To Bloody Sunday, local GP

General practitioner

A general practitioner is a medical practitioner who treats acute and chronic illnesses and provides preventive care and health education for all ages and both sexes. They have particular skills in treating people with multiple health issues and comorbidities...

Dr. Raymond McClean estimated the crowd as 15,000, which is the figure that was used by Bernadette Devlin McAliskey

Bernadette Devlin McAliskey

Josephine Bernadette Devlin McAliskey , also known as Bernadette Devlin and Bernadette McAliskey, is a socialist republican political activist...

in Parliament.

Numerous books and articles have been written and documentary films have been made on the subject.

Narrative of events

The people planned on marching to the GuildhallGuildhall, Derry

The Guildhall in Derry, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, is a building in which the elected members of Derry City Council meet. It was built in 1890....

, but because of army barricades designed to reroute the march it was redirected to Free Derry

Free Derry

Free Derry was a self-declared autonomous nationalist area of Derry, Northern Ireland, between 1969 and 1972. Its name was taken from a sign painted on a gable wall in the Bogside in January 1969 which read, “You are now entering Free Derry"...

Corner. A group of teenagers broke off from the march and persisted in pushing the barricade and marching on the Guildhall. They attacked the British army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

barricade

Barricade

Barricade, from the French barrique , is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction...

with stones. At this point, a water cannon, tear gas and rubber bullets were used to disperse the rioters. Such confrontations between soldiers and youths were common, though observers reported that the rioting was not intense. Two civilians, Damien Donaghy and John Johnston were shot and wounded by soldiers on William Street who claimed the former was carrying a black cylindrical object.

At a certain point, reports of an IRA sniper operating in the area were allegedly given to the Army command centre. At Brigade gave the British Parachute Regiment permission to go in to the Bogside. The order to fire live rounds was given, and one young man was shot and killed when he ran down Chamberlain Street away from the advancing troops. This first fatality, Jackie Duddy, was among a crowd who were running away. He was running alongside a priest, Father Edward Daly, when he was shot in the back. Continuing violence by British troops escalated, and eventually the order was given to mobilise the troops in an arrest operation, chasing the tail of the main group of marchers to the edge of the field by Free Derry Corner.

Despite a cease-fire order from the army HQ, over a hundred rounds were fired directly into the fleeing crowds by troops under the command of Major Ted Loden. Twelve more were killed, many of them as they attempted to aid the fallen. Fourteen others were wounded, twelve by shots from the soldiers and two knocked down by armoured personnel carriers.

The dead

- John (Jackie) Duddy (17). Shot in the chest in the car park of Rossville flats. Four witnesses stated Duddy was unarmed and running away from the paratroopers when he was killed. Three of them saw a soldier take deliberate aim at the youth as he ran. He is the uncle of the Irish boxer John DuddyJohn DuddyJohn Francis Duddy is a retired middleweight professional boxer, from Derry, Northern Ireland. Duddy fought under the moniker of "Ireland's John Duddy" or "The Derry Destroyer"....

.

- Patrick Joseph Doherty (31). Shot from behind while attempting to crawl to safety in the forecourt of Rossville flats. Doherty was the subject of a series of photographs, taken before and after he died by French journalist Gilles PeressGilles PeressGilles Peress is an internationally renowned French photojournalist known for his documentation of war and strife, including in Northern Ireland, Yugoslavia, Iran, and Rwanda. His work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Du magazine, Life, Stern, Geo, Paris-Match, Parkett, Aperture and...

. Despite testimony from "Soldier F" that he had fired at a man holding and firing a pistol, Widgery acknowledged that the photographs showed Doherty was unarmed, and that forensic tests on his hands for gunshot residue proved negative.

- Bernard McGuigan (41). Shot in the back of the head when he went to help Patrick Doherty. He had been waving a white handkerchief at the soldiers to indicate his peaceful intentions.

- Hugh Pious Gilmour (17). Shot through his right elbow, the bullet then entering his chest as he ran from the paratroopers on Rossville Street. Widgery acknowledged that a photograph taken seconds after Gilmour was hit corroborated witness reports that he was unarmed, and that tests for gunshot residue were negative.

- Kevin McElhinney (17). Shot from behind while attempting to crawl to safety at the front entrance of the Rossville Flats. Two witnesses stated McElhinney was unarmed.

- Michael Gerald Kelly (17). Shot in the stomach while standing near the rubble barricade in front of Rossville Flats. Widgery accepted that Kelly was unarmed.

- John Pius Young (17). Shot in the head while standing at the rubble barricade. Two witnesses stated Young was unarmed.

- William Noel Nash (19). Shot in the chest near the barricade. Witnesses stated Nash was unarmed and going to the aid of another when killed.

- Michael M. McDaid (20). Shot in the face at the barricade as he was walking away from the paratroopers. The trajectory of the bullet indicated he could have been killed by soldiers positioned on the Derry Walls.

- James Joseph Wray (22). Wounded then shot again at close range while lying on the ground. Witnesses who were not called to the Widgery Tribunal stated that Wray was calling out that he could not move his legs before he was shot the second time.

- Gerald DonaghyGerald DonaghyGerald V. Donaghy was a native of the Bogside, Derry who was killed by the Parachute Regiment on Bloody Sunday in Derry, Northern Ireland.-Boyhood:...

(17). Shot in the stomach while attempting to run to safety between Glenfada Park and Abbey Park. Donaghy was brought to a nearby house by bystanders where he was examined by a doctor. His pockets were turned out in an effort to identify him. A later policeRoyal Ulster ConstabularyThe Royal Ulster Constabulary was the name of the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2000. Following the awarding of the George Cross in 2000, it was subsequently known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC. It was founded on 1 June 1922 out of the Royal Irish Constabulary...

photograph of Donaghy's corpse showed nail bombNail bombThe nail bomb is an anti-personnel explosive device packed with nails to increase its wounding ability. The nails act as shrapnel, leading almost certainly to greater loss of life and injury in inhabited areas than the explosives alone would. The nail bomb is also a type of flechette weapon...

s in his pockets. Neither those who searched his pockets in the house nor the British army medical officer (Soldier 138) who pronounced him dead shortly afterwards say they saw any bombs. Donaghy had been a member of Fianna ÉireannFianna ÉireannThe name Fianna Éireann , also written Fianna na hÉireann and Na Fianna Éireann , has been used by various Irish republican youth movements throughout the 20th and 21st centuries...

, an IRA-linked Republican youth movement. Paddy Ward, a police informer who gave evidence at the Saville Inquiry, claimed that he had given two nail bombs to Donaghy several hours before he was shot dead.

- Gerald (James) McKinney (34). Shot just after Gerald Donaghy. Witnesses stated that McKinney had been running behind Donaghy, and he stopped and held up his arms, shouting "Don't shoot! Don't shoot!", when he saw Donaghy fall. He was then shot in the chest.

- William Anthony McKinney (27). Shot from behind as he attempted to aid Gerald McKinney (no relation). He had left cover to try to help Gerald.

- John Johnston (59). Shot in the leg and left shoulder on William Street 15 minutes before the rest of the shooting started. Johnston was not on the march, but on his way to visit a friend in Glenfada Park. He died 4½ months later; his death has been attributed to the injuries he received on the day. He was the only one not to die immediately or soon after being shot.

Perspectives and analyses on the day

Home Secretary

The Secretary of State for the Home Department, commonly known as the Home Secretary, is the minister in charge of the Home Office of the United Kingdom, and one of the country's four Great Offices of State...

the next day in the House of Commons, was that the paratroopers had reacted to gun and nail bomb attacks from suspected IRA members. All eyewitnesses (apart from the soldiers), including marchers, local residents, and British and Irish journalists present, maintain that soldiers fired into an unarmed crowd, or were aiming at fleeing people and those tending the wounded, whereas the soldiers themselves were not fired upon. No British soldier was wounded by gunfire or reported any injuries, nor were any bullets or nail bombs recovered to back up their claims.

In the events that followed, irate crowds burned down the British embassy on Merrion Square

Merrion Square

Merrion Square is a Georgian square on the southside of Dublin city centre. It was laid out after 1762 and was largely complete by the beginning of the 19th century. It is considered one of the city's finest surviving squares...

in Dublin. Anglo-Irish relations hit one of their lowest ebbs, with Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs

Minister for Foreign Affairs (Ireland)

The Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade is the senior minister at the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in the Government of Ireland. Its headquarters are at Iveagh House, on St Stephen's Green in Dublin; "Iveagh House" is often used as a metonym for the department as a whole.The current...

, Patrick Hillery

Patrick Hillery

Patrick John "Paddy" Hillery was an Irish politician and the sixth President of Ireland from 1976 until 1990. First elected at the 1951 general election as a Fianna Fáil Teachta Dála for Clare, he remained in Dáil Éireann until 1973...

, going specially to the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

in New York to demand UN involvement in the Northern Ireland "Troubles".

Although there were many IRA men—both Official

Official IRA

The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA is an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to create a "32-county workers' republic" in Ireland. It emerged from a split in the Irish Republican Army in December 1969, shortly after the beginning of "The Troubles"...

and Provisional—present at the protest, it is claimed they were all unarmed, apparently because it was anticipated that the paratroopers would attempt to "draw them out". March organizer and MP Ivan Cooper

Ivan Cooper

Ivan Averill Cooper is a former politician from Northern Ireland who was a Member of the Parliament of Northern Ireland, and founding member of the SDLP...

had been promised beforehand that no armed IRA men would be near the march. One paratrooper who gave evidence at the Tribunal testified that they were told by an officer to expect a gunfight and "We want some kills". In the event, one man was witnessed by Father Edward Daly

Edward Daly (bishop)

Edward Daly , D.D., was the Catholic Lord Bishop of Derry from 1974 to 1993.- Early life & priestly ministry :...

and others haphazardly firing a revolver in the direction of the paratroopers. Later identified as a member of the Official IRA, this man was also photographed in the act of drawing his weapon, but was apparently not seen or targeted by the soldiers. Various other claims have been made to the Saville Inquiry about gunmen on the day.

The city's coroner

Coroner

A coroner is a government official who* Investigates human deaths* Determines cause of death* Issues death certificates* Maintains death records* Responds to deaths in mass disasters* Identifies unknown dead* Other functions depending on local laws...

, retired British Army Major Hubert O'Neill, issued a statement on 21 August 1973, at the completion of the inquest

Inquest

Inquests in England and Wales are held into sudden and unexplained deaths and also into the circumstances of discovery of a certain class of valuable artefacts known as "treasure trove"...

into the people killed. He declared:

Two days after Bloody Sunday, the Westminster Parliament adopted a resolution for a tribunal

Tribunal

A tribunal in the general sense is any person or institution with the authority to judge, adjudicate on, or determine claims or disputes—whether or not it is called a tribunal in its title....

into the events of the day, resulting in Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Edward Heath

Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George "Ted" Heath, KG, MBE, PC was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and as Leader of the Conservative Party ....

commissioning the Lord Chief Justice

Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales

The Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales is the head of the judiciary and President of the Courts of England and Wales. Historically, he was the second-highest judge of the Courts of England and Wales, after the Lord Chancellor, but that changed as a result of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005,...

, Lord Widgery

John Widgery, Baron Widgery

John Passmore Widgery, Baron Widgery, OBE, TD, QC, PC was an English judge who served as Lord Chief Justice of England from 1971 to 1980...

to undertake it. Many witnesses intended to boycott

Boycott

A boycott is an act of voluntarily abstaining from using, buying, or dealing with a person, organization, or country as an expression of protest, usually for political reasons...

the tribunal as they lacked faith in Widgery's impartiality, but were eventually persuaded to take part. Widgery's quickly produced report—completed within ten weeks (10 April) and published within eleven (19 April)—supported the Army's account of the events of the day. Among the evidence presented to the tribunal were the results of paraffin tests, used to identify lead

Lead

Lead is a main-group element in the carbon group with the symbol Pb and atomic number 82. Lead is a soft, malleable poor metal. It is also counted as one of the heavy metals. Metallic lead has a bluish-white color after being freshly cut, but it soon tarnishes to a dull grayish color when exposed...

residues from firing weapons, and that nail bombs had been found on the body of one of those killed. Tests for traces of explosives on the clothes of eleven of the dead proved negative, while those of the remaining man could not be tested as they had already been washed. Most Irish people and witnesses to the event disputed the report's conclusions and regarded it as a whitewash. It has been argued that firearms residue on some deceased may have come from contact with the soldiers who themselves moved some of the bodies, or that the presence of lead on the hands of one (James Wray) was easily explained by the fact that his occupation involved the use of lead-based solder

Solder

Solder is a fusible metal alloy used to join together metal workpieces and having a melting point below that of the workpiece.Soft solder is what is most often thought of when solder or soldering are mentioned and it typically has a melting range of . It is commonly used in electronics and...

. In fact, in 1992, John Major

John Major

Sir John Major, is a British Conservative politician, who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990–1997...

, writing to John Hume

John Hume

John Hume is a former Irish politician from Derry, Northern Ireland. He was a founding member of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, and was co-recipient of the 1998 Nobel Peace Prize, with David Trimble....

stated:

Devlin punched Reginald Maudling

Reginald Maudling

Reginald Maudling was a British politician who held several Cabinet posts, including Chancellor of the Exchequer. He had been spoken of as a prospective Conservative leader since 1955, and was twice seriously considered for the post; he was Edward Heath's chief rival in 1965...

, the Secretary of State for the Home Department in the Conservative

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

government, when he made a statement to Parliament on the events of Bloody Sunday stating that the British Army had fired only in self-defence.

She was temporarily suspended from Parliament as a result of the incident.

In January 1997, the United Kingdom television station Channel 4

Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British public-service television broadcaster which began working on 2 November 1982. Although largely commercially self-funded, it is ultimately publicly owned; originally a subsidiary of the Independent Broadcasting Authority , the station is now owned and operated by the Channel...

carried a news report that suggested that members of the Royal Anglian Regiment

Royal Anglian Regiment

The Royal Anglian Regiment is an infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Queen's Division.The regiment was formed on 1 September 1964 as the first of the new large infantry regiments, through the amalgamation of the four regiments of the East Anglian Brigade.* 1st Battalion from the...

had also opened fire on the protesters and could have been responsible for three of the fourteen deaths.

On 29 May 2007 it was reported that General Sir Mike Jackson

Mike Jackson

General Sir Michael David "Mike" Jackson, is a retired British Army officer and one of its most high-profile generals since the Second World War. Originally commissioned into the Intelligence Corps in 1963, he transferred to the Parachute Regiment, with whom he served two of his three tours of...

, second-in-command of 1 Para on Bloody Sunday, said: "I have no doubt that innocent people were shot". This was in sharp contrast to his insistence, for more than 30 years, that those killed on the day had not been innocent.

The Saville Inquiry

Although British Prime MinisterPrime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

John Major

John Major

Sir John Major, is a British Conservative politician, who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990–1997...

rejected John Hume

John Hume

John Hume is a former Irish politician from Derry, Northern Ireland. He was a founding member of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, and was co-recipient of the 1998 Nobel Peace Prize, with David Trimble....

's requests for a public inquiry

Public inquiry

A Tribunal of Inquiry is an official review of events or actions ordered by a government body in Common Law countries such as the United Kingdom, Ireland or Canada. Such a public inquiry differs from a Royal Commission in that a public inquiry accepts evidence and conducts its hearings in a more...

into the killings, his successor, Tony Blair

Tony Blair

Anthony Charles Lynton Blair is a former British Labour Party politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2 May 1997 to 27 June 2007. He was the Member of Parliament for Sedgefield from 1983 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007...

, decided to start one. A second commission of inquiry, chaired by Lord Saville, was established in January 1998 to re-examine 'Bloody Sunday'. The other judges were John Toohey QC

Queen's Counsel

Queen's Counsel , known as King's Counsel during the reign of a male sovereign, are lawyers appointed by letters patent to be one of Her [or His] Majesty's Counsel learned in the law...

, a former Justice

Judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as part of a panel of judges. The powers, functions, method of appointment, discipline, and training of judges vary widely across different jurisdictions. The judge is supposed to conduct the trial impartially and in an open...

of the High Court of Australia

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

who had worked on Aboriginal issues (he replaced New Zealander Sir Edward Somers QC, who retired from the Inquiry in 2000 for personal reasons), and Mr Justice William Hoyt

William Lloyd Hoyt

William Lloyd Hoyt, is a Canadian lawyer and judge. He was Chief Justice of New Brunswick from 1993 to 1998.Born in Saint John, New Brunswick, Hoyt received a Bachelor of Arts degree and a Master of Arts degree from Acadia University in 1952...

QC, former Chief Justice

Chief Justice

The Chief Justice in many countries is the name for the presiding member of a Supreme Court in Commonwealth or other countries with an Anglo-Saxon justice system based on English common law, such as the Supreme Court of Canada, the Constitutional Court of South Africa, the Court of Final Appeal of...

of New Brunswick

New Brunswick

New Brunswick is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the only province in the federation that is constitutionally bilingual . The provincial capital is Fredericton and Saint John is the most populous city. Greater Moncton is the largest Census Metropolitan Area...

and a member of the Canadian Judicial Council

Canadian Judicial Council

The Canadian Judicial Council is a federal body created under the Judges Act , with the mandate to "promote efficiency, uniformity, and accountability, and to improve quality of judicial service in the superior courts of Canada". The Council is also mandated to review "any complaint or allegation"...

. The hearings were concluded in November 2004, and the report was published 15 June 2010. The Saville Inquiry was a more comprehensive study than the Widgery Tribunal, interviewing a wide range of witnesses, including local residents, soldiers, journalists and politicians. Lord Saville declined to comment on the Widgery report and made the point that the Saville Inquiry was a judicial inquiry into 'Bloody Sunday', not the Widgery Tribunal.

Evidence given by Martin McGuiness, a senior member of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin is a left wing, Irish republican political party in Ireland. The name is Irish for "ourselves" or "we ourselves", although it is frequently mistranslated as "ourselves alone". Originating in the Sinn Féin organisation founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith, it took its current form in 1970...

and now the deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, to the inquiry stated that he was second-in-command of the Derry City brigade of the Provisional IRA and was present at the march. He did not answer questions about where he had been staying because he said it would compromise the safety of the individuals involved.

A claim was made at the Saville Inquiry that McGuinness was responsible for supplying detonators for nail bombs on Bloody Sunday. Paddy Ward claimed he was the leader of the Fianna Éireann

Fianna Éireann

The name Fianna Éireann , also written Fianna na hÉireann and Na Fianna Éireann , has been used by various Irish republican youth movements throughout the 20th and 21st centuries...

, the youth wing of the IRA in January 1972. He claimed McGuinness, the second-in-command of the IRA in the city at the time, and another anonymous IRA member gave him bomb parts on the morning of 30 January, the date planned for the civil rights march. He said his organisation intended to attack city-centre premises in Derry on the day when civilians were shot dead by British soldiers. In response McGuinness rejected the claims as "fantasy", while Gerry O'Hara, a Sinn Féin councillor in Derry stated that he and not Ward was the Fianna leader at the time.

Many observers allege that the Ministry of Defence

Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom)

The Ministry of Defence is the United Kingdom government department responsible for implementation of government defence policy and is the headquarters of the British Armed Forces....

acted in a way to impede the inquiry. Over 1,000 army photographs and original army helicopter video footage were never made available. Additionally, guns used on the day by the soldiers that could have been evidence in the inquiry were lost by the MoD. The MoD claimed that all the guns had been destroyed, but some were subsequently recovered in various locations (such as Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone , officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Guinea to the north and east, Liberia to the southeast, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west and southwest. Sierra Leone covers a total area of and has an estimated population between 5.4 and 6.4...

and Beirut

Beirut

Beirut is the capital and largest city of Lebanon, with a population ranging from 1 million to more than 2 million . Located on a peninsula at the midpoint of Lebanon's Mediterranean coastline, it serves as the country's largest and main seaport, and also forms the Beirut Metropolitan...

) despite the obstruction.

By the time the inquiry had retired to write up its findings, it had interviewed over 900 witnesses, over seven years, making it the biggest investigation in British legal

Law of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom has three legal systems. English law, which applies in England and Wales, and Northern Ireland law, which applies in Northern Ireland, are based on common-law principles. Scots law, which applies in Scotland, is a pluralistic system based on civil-law principles, with common law...

history. The cost of this process has drawn criticism; as of the publication of the Saville Report being .

The report of the inquiry was published on 15 June 2010. The report concluded, "The firing by soldiers of 1 PARA on Bloody Sunday caused the deaths of 13 people and injury to a similar number, none of whom was posing a threat of causing death or serious injury." Saville stated that British paratroopers "lost control", fatally shooting fleeing civilians and those who tried to aid the civilians who had been shot by the British soldiers. The report stated that British soldiers had concocted lies in their attempt to hide their acts. Saville stated that the civilians had not been warned by the British soldiers that they intended to shoot. The report states, contrary to the previously established belief, that no stones and no petrol bombs were thrown by civilians before British soldiers shot at them, and that the civilians were not posing any threat.

The report concluded that an Official IRA sniper fired on British soldiers, albeit on the balance of evidence his shot was fired after the Army shots that wounded Damien Donaghey and John Johnston. The Inquiry rejected the sniper's account that this shot had been made in reprisal, stating the view that he and another Official IRA member had already been in position, and the shot had probably been fired simply because the opportunity had presented itself. Ultimately, the Saville Inquiry was inconclusive on Martin McGuiness' role due to a lack of certainty over his movements, concluding that while he was "engaged in paramilitary activity" during Bloody Sunday, and had probably been armed with a Thompson submachine gun

Thompson submachine gun

The Thompson is an American submachine gun, invented by John T. Thompson in 1919, that became infamous during the Prohibition era. It was a common sight in the media of the time, being used by both law enforcement officers and criminals...

, there was insufficient evidence to make any finding other than they were "sure that he did not engage in any activity that provided any of the soldiers with any justification for opening fire".

Impact on Northern Ireland divisions

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, FSS, PC was a British Labour Member of Parliament, Leader of the Labour Party. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s, winning four general elections, including a minority government after the...

, then the Leader of the Opposition

Leader of the Opposition (UK)

The Leader of Her Majesty's Most Loyal Opposition in the United Kingdom is the politician who leads the Official Opposition in the United Kingdom. There is also a Leader of the Opposition in the House of Lords...

in the Commons, reiterated his belief that a united Ireland

United Ireland

A united Ireland is the term used to refer to the idea of a sovereign state which covers all of the thirty-two traditional counties of Ireland. The island of Ireland includes the territory of two independent sovereign states: the Republic of Ireland, which covers 26 counties of the island, and the...

was the only possible solution to Northern Ireland's Troubles. William Craig, then Stormont Home Affairs Minister, suggested that the west bank of Derry should be ceded to the Republic of Ireland

Republic of Ireland

Ireland , described as the Republic of Ireland , is a sovereign state in Europe occupying approximately five-sixths of the island of the same name. Its capital is Dublin. Ireland, which had a population of 4.58 million in 2011, is a constitutional republic governed as a parliamentary democracy,...

.

When it was deployed on duty in Northern Ireland, the British Army was welcomed by Roman Catholics as a neutral force there to protect them from Protestant mobs, the Royal Ulster Constabulary

Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary was the name of the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2000. Following the awarding of the George Cross in 2000, it was subsequently known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC. It was founded on 1 June 1922 out of the Royal Irish Constabulary...

(RUC) and the B-Specials

Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary was a reserve police force in Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the founding of Northern Ireland. It was an armed corps, organised partially on military lines and called out in times of emergency, such as war or insurgency...

. After Bloody Sunday many Catholics turned on the British army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

, seeing it no longer as their protector but as their enemy. Young nationalists

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

became increasingly attracted to violent republican

Irish Republicanism

Irish republicanism is an ideology based on the belief that all of Ireland should be an independent republic.In 1801, under the Act of Union, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland merged to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

groups. With the Official IRA

Official IRA

The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA is an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to create a "32-county workers' republic" in Ireland. It emerged from a split in the Irish Republican Army in December 1969, shortly after the beginning of "The Troubles"...

and Official Sinn Féin having moved away from mainstream Irish republicanism towards Marxism

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

, the Provisional IRA began to win the support of newly radicalised, disaffected young people.

In the following twenty years, the Provisional Irish Republican Army

Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army is an Irish republican paramilitary organisation whose aim was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and bring about a socialist republic within a united Ireland by force of arms and political persuasion...

and other smaller republican groups such as the Irish National Liberation Army

Irish National Liberation Army

The Irish National Liberation Army or INLA is an Irish republican socialist paramilitary group that was formed on 8 December 1974. Its goal is to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and create a socialist united Ireland....

(INLA) mounted an armed campaign

Provisional IRA campaign 1969–1997

From 1969 until 1997, the Provisional Irish Republican Army conducted an armed paramilitary campaign in Northern Ireland and England, aimed at ending British rule in Northern Ireland in order to create a united Ireland....

against the British, by which they meant the RUC, the British Army, the Ulster Defence Regiment

Ulster Defence Regiment

The Ulster Defence Regiment was an infantry regiment of the British Army which became operational in 1970, formed on similar lines to other British reserve forces but with the operational role of defence of life or property in Northern Ireland against armed attack or sabotage...

(UDR) of the British Army (and, according to their critics, the Protestant and unionist establishment). With rival paramilitary organisations appearing in both the nationalist/republican and Irish unionist

Unionism in Ireland

Unionism in Ireland is an ideology that favours the continuation of some form of political union between the islands of Ireland and Great Britain...

/Ulster loyalist communities (the Ulster Defence Association

Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association is the largest although not the deadliest loyalist paramilitary and vigilante group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 and undertook a campaign of almost twenty-four years during "The Troubles"...

, Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), etc. on the loyalist side), the Troubles cost the lives of thousands of people. Incidents included the killing of three members of a pop band, the Miami Showband

Miami Showband killings

The Miami Showband killings was a paramilitary attack at Buskhill, County Down, Northern Ireland, in the early morning of 31 July 1975. It left five people dead at the hands of Ulster Volunteer Force gunmen, including three members of The Miami Showband...

, by a gang including members of the UVF who were also members of the local army regiment, the UDR, and in uniform at the time, and the killing by the Provisionals of eighteen members of the Parachute Regiment in the Warrenpoint Ambush

Warrenpoint Ambush

The Warrenpoint ambush or the Warrenpoint massacre was a guerrilla assault by the Provisional Irish Republican Army on 27 August 1979. The IRA attacked a British Army convoy with two large bombs at Narrow Water Castle , Northern Ireland...

-seen by some as revenge for Bloody Sunday.

With the official cessation of violence by some of the major paramilitary organisations and the creation of the power-sharing executive at Stormont

Parliament Buildings (Northern Ireland)

The Parliament Buildings, known as Stormont because of its location in the Stormont area of Belfast is the seat of the Northern Ireland Assembly and the Northern Ireland Executive...

in Belfast

Belfast