Irish National Liberation Army

Encyclopedia

The Irish National Liberation Army or INLA is an Irish republican

socialist

paramilitary group that was formed on 8 December 1974. Its goal is to remove Northern Ireland

from the United Kingdom

and create a socialist united Ireland

.

Sharing a common Marxist

ideology with its political wing, the Irish Republican Socialist Party

(IRSP), it enjoyed its peak of influence in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In its earliest days, the INLA was known as the People's Liberation Army (PLA). During the PLA period, the group's purpose was primarily to protect IRSP members from attacks.

After a twenty-four year armed campaign, the INLA declared a ceasefire

on 22 August 1998. In August 1999, it stated that "There is no political or moral argument to justify a resumption of the campaign". In October 2009, the INLA formally vowed to pursue its aims through peaceful political means.

The organisation is classified as a proscribed terrorist

group in the UK and as an illegal organisation in the Republic of Ireland

.

and other activists who had left or been forced out of the Official IRA in the wake of the OIRA's 1972 ceasefire and the increasingly reformist approach of Official Sinn Féin. Costello espoused a mixture of traditional republican militarism and Marxist-oriented politics. Shortly after it was founded, the INLA came under attack from their former comrades in the OIRA, who wanted to destroy the new grouping before it could get off the ground.

On 20 February 1975, Hugh Ferguson, an INLA member and an IRSP branch chairperson, was the first person to be killed in the feud. One of the first military operations of the INLA was the shooting of OIRA leader Sean Garland

in Dublin on 1 March. Although shot six times he survived. After several more shootings a truce was arranged, but fighting started again. The most prominent victim of the re-started feud was Billy McMillen

, the commander of the OIRA in Belfast, shot by INLA member Gerard Steenson. His murder was unauthorised and was condemned by Costello. This was followed by several more assassinations on both sides, the most prominent victim being Seamus Costello, who was shot dead on the North Strand Road

in Dublin on 6 October 1977. Costello's death was a severe blow to the INLA, as he was their most able political and military leader.

It has also recently been claimed by some in the Republican Socialist Movement that one of their members killed in 1975, Brendan McNamee (who was involved in the killing of Billy McMillen), was actually killed by Provisional Irish Republican Army

members. The Officials had denied involvement at the time of the killing and had instead blamed it on the Provisionals (Provos

) who also denied involvement. This has not however been confirmed by the IRSP officially.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the INLA developed a modest organisation in Northern Ireland

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the INLA developed a modest organisation in Northern Ireland

, particularly based on Divis Flats in west Belfast

, which as a result became colloquially known as "the planet of the Irps" (a reference to the Irish Republican Socialist Party

and the film Planet of the Apes

). During this period, the INLA competed with the Provisional Irish Republican Army

for members, with both groups attacking the British Army

and the Royal Ulster Constabulary

. The first action to bring the INLA to international notice was its assassination on 30 March 1979 of Airey Neave

, one of Margaret Thatcher

's closest political supporters.

The INLA lost another of its founding leadership in 1980, when Ronnie Bunting

, a Protestant republican

, was assassinated at his home. Noel Lyttle, who was also a Protestant member of INLA, was killed in the same incident. Another leading INLA member, Miriam Daly

, was killed by loyalist

assassins in the same year. Although no group claimed responsibility, the INLA claimed that the SAS

was involved in the killings of Bunting and Lyttle.

Offensive INLA actions at this time included the 1982 bombing of the Mount Gabriel

radar station in County Cork

, which the INLA alleged was providing assistance to North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, allegedly in violation of Irish neutrality

. Their most bloody attack came on 6 December 1982 – the Ballykelly disco bombing

of the Droppin' Well Bar in Ballykelly, County Londonderry

, which catered to British military personnel, in which 11 soldiers and 6 civilians were killed.

Members of the INLA participated in the 1980 and 1981 hunger strikes

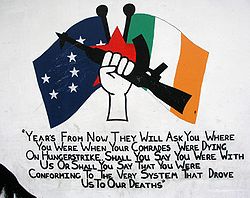

Members of the INLA participated in the 1980 and 1981 hunger strikes

for the recognition of the political status of paramilitary prisoners. Three INLA members died during the latter hunger strike – Patsy O'Hara

, Kevin Lynch, and Michael Devine, along with seven Provisional IRA members.

On 20 November 1983, three members of the congregation in the Mountain Lodge Pentecostal Church, Darkley near Keady

, County Armagh

were shot dead during a Sunday service. The attack was claimed by the Catholic Reaction Force

, a cover name for a small group of people, including one member of the INLA. The weapon used came from an INLA arms dump, but Tim Pat Coogan

claims in his book The IRA that the weapon had been given to the INLA member to assassinate a known loyalist and the attack on the church was not sanctioned. The INLA's then chief of staff, Dominic McGlinchey

, came out of hiding to condemn the attack.

On 14 April 1992, the INLA carried out its first killing in England after the death of Airey Neave, when they shot dead a recruiting Army Sergeant in Derby

. (In June 2010, Declan Duffy was charged with the murder.)

. Harry Kirkpatrick

, an INLA volunteer, was arrested in February 1983 on charges of five murders and subsequently agreed to give evidence against other INLA members.

The INLA kidnapped his wife Elizabeth, and later kidnapped his sister and his stepfather too. All were released physically unharmed. INLA Chief of Staff Dominic McGlinchey

is alleged to have killed Kirkpatrick's lifelong friend Gerard 'Sparky' Barkley because he may have revealed the whereabouts of the Kirkpatrick family members to the police.

In May 1983, ten men were charged with various offences on the basis of evidence from Kirkpatrick. Those charged included Irish Republican Socialist Party vice-chairman Kevin McQuillan and former councillor Sean Flynn. IRSP chairman and INLA member James Brown

was charged with the murder of a police officer. Others escaped; Jim Barr, an IRSP member named by Kirkpatrick as part of the INLA, fled to the US where, having spent 17 months in jail, he won political asylum in 1993.

In December 1985, 27 people were convicted on the basis of Kirkpatrick's statements. By December 1986, 24 of them would have their convictions overturned. Gerard Steenson

was given five life sentences for the deaths of the same five individuals that Kirkpatrick himself had been convicted of. These included UDR soldier Colin Quinn shot in Belfast in December 1980.

The distrust and division that they sowed were the final act in splitting former comrades into warring factions and leading to the formation of the Irish People's Liberation Organisation

by Jimmy Brown and Gerard Steenson, both of whom had been convicted under the supergrass scheme. This led to that organisation's feud with the INLA in which 16 people would be killed.

(IPLO), an organisation founded by people who had resigned or been expelled from the INLA. The IPLO's initial aim was to destroy the INLA and replace it with their organisation. Five members of the INLA were killed by the IPLO, including their leaders Ta Power and John O'Reilly. The INLA retaliated with several killings of their own. After the INLA killed the IPLO's leader, Gerard Steenson

, a truce was reached. Although severely damaged by the IPLO's attacks, the INLA continued to exist. The IPLO, which was heavily involved in drug dealing, was put out of existence by the Provisional IRA in a large scale operation in 1992.

Directly after the feud in October 1987, the INLA received more damaging publicity when Dessie O'Hare

, an erstwhile INLA volunteer set up his own group called the 'Irish Revolutionary Brigade' and kidnapped a Dublin dentist named John O'Grady. O'Hare cut off two of O'Grady's fingers and sent them to his family in order to secure a ransom

. O'Grady was eventually rescued and O'Hare's group arrested after several shootouts with armed Gardaí. The INLA disassociated itself from the action, issuing a statement saying O'Hare 'is not a member of the INLA'. O'Hare later rejoined the INLA while in prison.

In 1995, four members of the INLA, including chief of staff Hugh Torney

, were arrested by Gardaí in Balbriggan

while trying to smuggle weapons from Dublin to Belfast

. Torney, with the support of two of his co-accused, called a ceasefire in exchange for favourable treatment by the Irish Government

. Since Torney, who was chief of staff, under the INLA's rules lacked the authority to call a ceasefire (because he was incarcerated), he and the two men who supported him were expelled from the INLA.

Torney and one of those men, Dessie McCleery, and founder member John Fennell were not going to surrender the leadership of the organisation. Their faction, known as the INLA/GHQ, assassinated the new INLA chief of staff, Gino Gallagher

. After the INLA killed both McCleery and Torney in 1996, the rest of Torney's faction quietly disbanded.

was the founder and leader of the Loyalist Volunteer Force

(LVF). Since July 1996, the group had launched a string of attacks on civilians (whom they identified as Catholics), killing at least five. In April 1997, Wright was sentenced to eight years in Maze Prison

. On the morning of 27 December 1997, he was assassinated by three INLA prisoners – Christopher "Crip" McWilliams, John "Sonny" Glennon and John Kennaway – who were armed with two pistol

s. He was shot as he travelled in a prison van (alongside another LVF prisoner, Norman Green and one prison officer) from one part of the prison to another. Kennaway held the driver hostage and Glennon gave cover with a .22 Derringer pistol while McWilliams opened the side door and fired seven shots at Wright with his PA63 semi-automatic

. After killing Wright, the three volunteers handed themselves over to prison guards. They also handed over a statement, which read:

That night, LVF gunmen opened fire on a disco

in a mainly nationalist area of Dungannon

. Four civilians were wounded and a former Provisional IRA volunteer was killed in the attack.

The nature of Wright's killing led to speculation that prison authorities colluded with the INLA to have him killed, as he was a danger to the peace process. The INLA strongly denied these rumours, and published a detailed account of the assassination in the March/April 1999 issue of The Starry Plough

newspaper.

– an arrangement it had opposed during the 1998 referendum – by the people of Ireland.

'The will of the Irish people is clear. It is now time to silence the guns and allow the working classes the time and the opportunity to advance their demands and their needs.'

Although the INLA does not support the Good Friday Agreement, it does not call for a return to armed struggle on behalf of republicans either. An INLA statement released in 1999 declared, "we do not see a return to armed struggle as a viable option at the present time"

The INLA maintains a presence in parts of Northern Ireland and has carried out punishment beatings on local alleged petty criminals.

The INLA maintains a presence in parts of Northern Ireland and has carried out punishment beatings on local alleged petty criminals.

The Independent Monitoring Commission

, which monitors paramilitary activity in Northern Ireland, claimed in a November 2004 report that the INLA was heavily involved in criminality. In 1997, an INLA man named John Morris was shot dead by Gardaí (Irish Police) in Dublin during the attempted robbery of a newspaper distributor's depot in Inchicore

. Three other INLA members were arrested in the incident. In 1999, the INLA in Dublin became involved in a feud with a criminal gang in the city. After a young INLA man named Patrick Campbell was killed by drug dealers, the INLA carried out several shootings in reprisal, including at least one killing. Irish journalist Paul Williams has also claimed the INLA, especially in Dublin, is now primarily a front for organised crime. The IRSP and INLA deny these allegations, arguing that no one has been simultaneously convicted of membership in the INLA and of drug offences. The IRSP and the INLA have both strongly denied any involvement with drug dealing, stating that the INLA has threatened criminals which it claims have falsely used its name.

In 2006, the INLA claimed to have put at least two drugs gangs out of business in Northern Ireland. After their raid on a criminal organisation based in the north-west, they released a statement saying that "the Irish National Liberation Army will not allow the working class people of this city to be used as cannon fodder by these criminals whose only concern is profit by whatever means available to them."

The October 2006 Independent Monitoring Commission

(IMC) report stated that the INLA "was not capable of undertaking a sustained campaign [against the United Kingdom], nor does it aspire to".

In December 2007, disturbances broke out at an INLA parade in the Bogside

in Derry

between watchers and Police Service of Northern Ireland

(PSNI) officers attempting to arrest four of the marchers.

In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Independent Monitoring Commission

reports the INLA were said to have remained a threat, with a desire to mount more attack, and could well be more dangerous in the future, although in the meantime it was largely a criminal enterprise

. In the same vein they committed the murder of Brian McGlynn on 3 June 2007 during the span of the former's report. This murder was said to have occurred because the victim used the INLA name in the drug trade

. On 24 June 2008, the INLA was said to have committed the murder of Emmett Shiels, although the IMC report did indicate the investigation was continuing.

It was also said to be partaking in "serious crimes" such as drug dealing, extortion

, robbery

, fuel laundering and smuggling

. Furthermore, the INLA and CIRA are noted to have co-operated.

On 15 February 2009 the INLA claimed responsibility for the shooting dead of Derry drug-dealer Jim McConnell.

In March 2009 it was reported that the INLA had stood down its Dublin Brigade in order to allow its army council to carry out an internal investigation into allegations of drug-dealing and criminality. The INLA denied it as an organisation was involved in drug dealing and went on to say that "As a result of evidence presented to us, we are investigating the activities of people associated with us in [Dublin]. Pending that outcome, we have stood down several people." A short time later the INLA's Dublin Commander; Declan "Whacker" Duffy publicly disassociated himself from the organisation. Duffy criticized the INLA leadership stating that "You would imagine if there was a thorough investigation being carried out by the INLA they would have at least came and spoke to me." He went on to state that: "I can’t deny that I’m disappointed with the way the INLA has handled things but at the same time I’m not going to get into a sniping match with them."

On 19 August 2009 the INLA shot and wounded a man in Derry. The INLA claimed that the man was involved in drug dealing although the injured man and his family denied the allegation. However, in a newspaper article on 28 August the victim retracted his previous statement and admitted that he had been involved in small scale drug-dealing but has since ceased these activities.

, in Bray

, the INLA formally announced an end to its armed campaign, stating the current political framework allowed for the pursuit of its goals through peaceful, democratic means. Martin McMonagle from Derry said: "The Republican Socialist Movement has been informed by the INLA that following a process of serious debate ... it has concluded that the armed struggle is over. The objective of a 32-county socialist republic will be best achieved through exclusively peaceful political struggle". They laid a wreath beforehand.

The governments of Britain and Ireland were informed. Hillary Rodham Clinton

of the United States

was due to visit Belfast

the following day. Sinn Féin

's Gerry Adams

was doubtful but added: "However, if it is followed by the actions that are necessary, this is a welcome development". On 6 February 2010, days before the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning

(IICD) was due to disband, the INLA revealed that it had decommissioned its weapons over the preceding few weeks. Had the INLA retained its weapons beyond 9 February, the date on which the legislation under which the IICD operated ended, then they would have been treated as belonging to common criminals rather than remnants from the Troubles.

The decommissioning was confirmed by General John de Chastelain

of the IICD on 8 February 2010. On the same day INLA spokesman Martin McMonagle said that the INLA made "no apology for [its] part in the conflict" but they believed in the "primacy of politics" to "advance the working class struggle in Ireland".

's Sutton database, the INLA was responsible for 113 killings during "the Troubles", between 1969 and 2001. According to the INLA's Roll of Honour, 33 of its members were killed during the conflict.

Irish Republicanism

Irish republicanism is an ideology based on the belief that all of Ireland should be an independent republic.In 1801, under the Act of Union, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland merged to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

paramilitary group that was formed on 8 December 1974. Its goal is to remove Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

from the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and create a socialist united Ireland

United Ireland

A united Ireland is the term used to refer to the idea of a sovereign state which covers all of the thirty-two traditional counties of Ireland. The island of Ireland includes the territory of two independent sovereign states: the Republic of Ireland, which covers 26 counties of the island, and the...

.

Sharing a common Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

ideology with its political wing, the Irish Republican Socialist Party

Irish Republican Socialist Party

The Irish Republican Socialist Party or IRSP is a republican socialist party active in Ireland. It claims the legacy of socialist revolutionary James Connolly, who founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party in 1896 and was executed after the Easter Rising of 1916.- History :The Irish Republican...

(IRSP), it enjoyed its peak of influence in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In its earliest days, the INLA was known as the People's Liberation Army (PLA). During the PLA period, the group's purpose was primarily to protect IRSP members from attacks.

After a twenty-four year armed campaign, the INLA declared a ceasefire

Ceasefire

A ceasefire is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be declared as part of a formal treaty, but they have also been called as part of an informal understanding between opposing forces...

on 22 August 1998. In August 1999, it stated that "There is no political or moral argument to justify a resumption of the campaign". In October 2009, the INLA formally vowed to pursue its aims through peaceful political means.

The organisation is classified as a proscribed terrorist

Terrorism

Terrorism is the systematic use of terror, especially as a means of coercion. In the international community, however, terrorism has no universally agreed, legally binding, criminal law definition...

group in the UK and as an illegal organisation in the Republic of Ireland

Republic of Ireland

Ireland , described as the Republic of Ireland , is a sovereign state in Europe occupying approximately five-sixths of the island of the same name. Its capital is Dublin. Ireland, which had a population of 4.58 million in 2011, is a constitutional republic governed as a parliamentary democracy,...

.

Foundation

The founders of the INLA were Seamus CostelloSeamus Costello

Seamus Costello was a leader of Official Sinn Féin and the Official Irish Republican Army and latterly of the Irish Republican Socialist Party and the Irish National Liberation Army ....

and other activists who had left or been forced out of the Official IRA in the wake of the OIRA's 1972 ceasefire and the increasingly reformist approach of Official Sinn Féin. Costello espoused a mixture of traditional republican militarism and Marxist-oriented politics. Shortly after it was founded, the INLA came under attack from their former comrades in the OIRA, who wanted to destroy the new grouping before it could get off the ground.

On 20 February 1975, Hugh Ferguson, an INLA member and an IRSP branch chairperson, was the first person to be killed in the feud. One of the first military operations of the INLA was the shooting of OIRA leader Sean Garland

Seán Garland

Seán Garland is a former President of the Workers' Party in Ireland.-Early Life:Born at Belvedere Place, off Mountjoy Square in Dublin, Garland joined the Irish Republican Army in 1953. In 1954, he briefly joined the British Army as an IRA agent and collected intelligence on Gough Barracks in...

in Dublin on 1 March. Although shot six times he survived. After several more shootings a truce was arranged, but fighting started again. The most prominent victim of the re-started feud was Billy McMillen

Billy McMillen

Billy McMillen was an Irish republican activist and an officer of the Official Irish Republican Army...

, the commander of the OIRA in Belfast, shot by INLA member Gerard Steenson. His murder was unauthorised and was condemned by Costello. This was followed by several more assassinations on both sides, the most prominent victim being Seamus Costello, who was shot dead on the North Strand Road

North Strand Road

North Strand Road is a street in the Northside of Dublin, Ireland.-Route:North Strand Road is a continuation of Amiens Street that runs northeast from the junction of Portland Row and Seville Place...

in Dublin on 6 October 1977. Costello's death was a severe blow to the INLA, as he was their most able political and military leader.

It has also recently been claimed by some in the Republican Socialist Movement that one of their members killed in 1975, Brendan McNamee (who was involved in the killing of Billy McMillen), was actually killed by Provisional Irish Republican Army

Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army is an Irish republican paramilitary organisation whose aim was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and bring about a socialist republic within a united Ireland by force of arms and political persuasion...

members. The Officials had denied involvement at the time of the killing and had instead blamed it on the Provisionals (Provos

Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army is an Irish republican paramilitary organisation whose aim was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and bring about a socialist republic within a united Ireland by force of arms and political persuasion...

) who also denied involvement. This has not however been confirmed by the IRSP officially.

Armed campaign

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

, particularly based on Divis Flats in west Belfast

Belfast

Belfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

, which as a result became colloquially known as "the planet of the Irps" (a reference to the Irish Republican Socialist Party

Irish Republican Socialist Party

The Irish Republican Socialist Party or IRSP is a republican socialist party active in Ireland. It claims the legacy of socialist revolutionary James Connolly, who founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party in 1896 and was executed after the Easter Rising of 1916.- History :The Irish Republican...

and the film Planet of the Apes

Planet of the Apes (1968 film)

Planet of the Apes is a 1968 American science fiction film directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, based on the 1963 French novel La Planète des singes by Pierre Boulle. The film stars Charlton Heston, Roddy McDowall, Kim Hunter, Maurice Evans, James Whitmore, James Daly and Linda Harrison...

). During this period, the INLA competed with the Provisional Irish Republican Army

Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Provisional Irish Republican Army is an Irish republican paramilitary organisation whose aim was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and bring about a socialist republic within a united Ireland by force of arms and political persuasion...

for members, with both groups attacking the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

and the Royal Ulster Constabulary

Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary was the name of the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2000. Following the awarding of the George Cross in 2000, it was subsequently known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC. It was founded on 1 June 1922 out of the Royal Irish Constabulary...

. The first action to bring the INLA to international notice was its assassination on 30 March 1979 of Airey Neave

Airey Neave

Airey Middleton Sheffield Neave DSO, OBE, MC was a British soldier, barrister and politician.During World War II, Neave was one of the few servicemen to escape from the German prisoner-of-war camp Oflag IV-C at Colditz Castle...

, one of Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990...

's closest political supporters.

The INLA lost another of its founding leadership in 1980, when Ronnie Bunting

Ronnie Bunting

Ronnie Bunting was an Irish republican and socialist activist in Ireland. He became a member of the Official IRA in the early 1970s and was a founder member of the Irish National Liberation Army in 1974. He became leader of the INLA in 1978 and was assassinated in 1980.-Background:Bunting came...

, a Protestant republican

Protestant Nationalist

Irish nationalism has been chiefly associated with Roman Catholics. However, historically this is not an entirely accurate picture. Protestant nationalists were also influential supporters of the political independence the island of Ireland from the island of Great Britain and leaders of national...

, was assassinated at his home. Noel Lyttle, who was also a Protestant member of INLA, was killed in the same incident. Another leading INLA member, Miriam Daly

Miriam Daly

Miriam Daly was an Irish republican activist and university lecturer who was assassinated by loyalist paramilitaries.She was born in the Curragh army camp, Kildare, Ireland. Her father had been active in the Irish War of Independence alongside Michael Collins, but favoured the Anglo-Irish Treaty...

, was killed by loyalist

Ulster loyalism

Ulster loyalism is an ideology that is opposed to a united Ireland. It can mean either support for upholding Northern Ireland's status as a constituent part of the United Kingdom , support for Northern Ireland independence, or support for loyalist paramilitaries...

assassins in the same year. Although no group claimed responsibility, the INLA claimed that the SAS

Special Air Service

Special Air Service or SAS is a corps of the British Army constituted on 31 May 1950. They are part of the United Kingdom Special Forces and have served as a model for the special forces of many other countries all over the world...

was involved in the killings of Bunting and Lyttle.

Offensive INLA actions at this time included the 1982 bombing of the Mount Gabriel

Mount Gabriel

Mount Gabriel is a mountain on the Mizen Peninsula situated immediately to the north of the town of Schull, in West Cork, Ireland.Mt. Gabriel is 407m high and is the highest eminence in the coastal zone south and east of Bantry Bay. A roadway serving the radar installations on the summit is open...

radar station in County Cork

County Cork

County Cork is a county in Ireland. It is located in the South-West Region and is also part of the province of Munster. It is named after the city of Cork . Cork County Council is the local authority for the county...

, which the INLA alleged was providing assistance to North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, allegedly in violation of Irish neutrality

Irish neutrality

Ireland has a "traditional policy of military neutrality". In particular, Ireland remained neutral during World War II, and has never been a member of NATO or the Non-Aligned Movement. The formulation and justification of the neutrality policy has varied over time...

. Their most bloody attack came on 6 December 1982 – the Ballykelly disco bombing

Ballykelly disco bombing

The Droppin Well bombing or Ballykelly bombing occurred on 6 December 1982, when the Irish National Liberation Army exploded a time bomb at a disco in Ballykelly, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. The disco was targeted because it was frequented by British Army soldiers from the nearby...

of the Droppin' Well Bar in Ballykelly, County Londonderry

County Londonderry

The place name Derry is an anglicisation of the old Irish Daire meaning oak-grove or oak-wood. As with the city, its name is subject to the Derry/Londonderry name dispute, with the form Derry preferred by nationalists and Londonderry preferred by unionists...

, which catered to British military personnel, in which 11 soldiers and 6 civilians were killed.

1981 Irish hunger strike

The 1981 Irish hunger strike was the culmination of a five-year protest during The Troubles by Irish republican prisoners in Northern Ireland. The protest began as the blanket protest in 1976, when the British government withdrew Special Category Status for convicted paramilitary prisoners...

for the recognition of the political status of paramilitary prisoners. Three INLA members died during the latter hunger strike – Patsy O'Hara

Patsy O'Hara

Patsy O'Hara was an Irish republican hunger striker and member of the Irish National Liberation Army .He was born in Bishop Street, Derry, Northern Ireland. O'Hara joined Na Fianna Éireann in 1970, and in 1971 his brother Sean was interned in Long Kesh. In late 1971, he was shot and wounded by a...

, Kevin Lynch, and Michael Devine, along with seven Provisional IRA members.

On 20 November 1983, three members of the congregation in the Mountain Lodge Pentecostal Church, Darkley near Keady

Keady

Keady is a town in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. It is situated south of Armagh city and very close to the border with the Republic of Ireland. The town had a population of 2,960 people in the 2001 Census....

, County Armagh

County Armagh

-History:Ancient Armagh was the territory of the Ulaid before the fourth century AD. It was ruled by the Red Branch, whose capital was Emain Macha near Armagh. The site, and subsequently the city, were named after the goddess Macha...

were shot dead during a Sunday service. The attack was claimed by the Catholic Reaction Force

Catholic Reaction Force

The name Catholic Reaction Force was used to claim responsibility for attacks and threats against Protestants in Northern Ireland during "The Troubles". In 1983 it claimed responsibility for shooting dead three Protestant civilians at a church service near Darkley, County Armagh. That was claimed...

, a cover name for a small group of people, including one member of the INLA. The weapon used came from an INLA arms dump, but Tim Pat Coogan

Tim Pat Coogan

Timothy Patrick Coogan is an Irish historical writer, broadcaster and newspaper columnist. He served as editor of the Irish Press newspaper from 1968 to 1987...

claims in his book The IRA that the weapon had been given to the INLA member to assassinate a known loyalist and the attack on the church was not sanctioned. The INLA's then chief of staff, Dominic McGlinchey

Dominic McGlinchey

Dominic McGlinchey from Bellaghy, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland was an Irish republican paramilitary with the Irish National Liberation Army .-Background:...

, came out of hiding to condemn the attack.

On 14 April 1992, the INLA carried out its first killing in England after the death of Airey Neave, when they shot dead a recruiting Army Sergeant in Derby

Derby

Derby , is a city and unitary authority in the East Midlands region of England. It lies upon the banks of the River Derwent and is located in the south of the ceremonial county of Derbyshire. In the 2001 census, the population of the city was 233,700, whilst that of the Derby Urban Area was 229,407...

. (In June 2010, Declan Duffy was charged with the murder.)

Supergrass

In the early 1980s, the INLA was greatly weakened by splits and criminality within its own ranks, as well as the conviction of many of its members under the British supergrass schemeSupergrass (informer)

Supergrass is a slang term for an informer, which originated in London. Informers had been referred to as "grasses" since the late-1930s, and the "super" prefix was coined by journalists in the early 1970s to describe those informers from the city's underworld who testified against former...

. Harry Kirkpatrick

Harry Kirkpatrick

Henry 'Harry' Kirkpatrick is a former Irish National Liberation Army member turned informer against other members of the INLA. In February 1983 Kirkpatrick was arrested on multiple charges including the murder of two policemen, two UDR soldiers, and Hugh McGinn, a Catholic member of the...

, an INLA volunteer, was arrested in February 1983 on charges of five murders and subsequently agreed to give evidence against other INLA members.

The INLA kidnapped his wife Elizabeth, and later kidnapped his sister and his stepfather too. All were released physically unharmed. INLA Chief of Staff Dominic McGlinchey

Dominic McGlinchey

Dominic McGlinchey from Bellaghy, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland was an Irish republican paramilitary with the Irish National Liberation Army .-Background:...

is alleged to have killed Kirkpatrick's lifelong friend Gerard 'Sparky' Barkley because he may have revealed the whereabouts of the Kirkpatrick family members to the police.

In May 1983, ten men were charged with various offences on the basis of evidence from Kirkpatrick. Those charged included Irish Republican Socialist Party vice-chairman Kevin McQuillan and former councillor Sean Flynn. IRSP chairman and INLA member James Brown

Jimmy Brown (Irish nationalist)

Jimmy Brown was a Belfast member of the Irish Republican Socialist Party , the Irish National Liberation Army , and the Irish People's Liberation Organisation ..Jimmy Brown left the IRSP in the mid-eighties to join up with the IPLO...

was charged with the murder of a police officer. Others escaped; Jim Barr, an IRSP member named by Kirkpatrick as part of the INLA, fled to the US where, having spent 17 months in jail, he won political asylum in 1993.

In December 1985, 27 people were convicted on the basis of Kirkpatrick's statements. By December 1986, 24 of them would have their convictions overturned. Gerard Steenson

Gerard Steenson

Gerard Steenson was an Irish republican socialist paramilitary activist. He was a member of the Irish National Liberation Army group during the Troubles in Northern Ireland....

was given five life sentences for the deaths of the same five individuals that Kirkpatrick himself had been convicted of. These included UDR soldier Colin Quinn shot in Belfast in December 1980.

The distrust and division that they sowed were the final act in splitting former comrades into warring factions and leading to the formation of the Irish People's Liberation Organisation

Irish People's Liberation Organisation

The Irish People's Liberation Organisation was a small Irish republican paramilitary organization which was formed in 1986 by disaffected and expelled members of the Irish National Liberation Army whose factions coalesced in the aftermath of the supergrass trials...

by Jimmy Brown and Gerard Steenson, both of whom had been convicted under the supergrass scheme. This led to that organisation's feud with the INLA in which 16 people would be killed.

Feuds and splits

In 1987, the INLA and its political wing, the IRSP came under attack from the Irish People's Liberation OrganisationIrish People's Liberation Organisation

The Irish People's Liberation Organisation was a small Irish republican paramilitary organization which was formed in 1986 by disaffected and expelled members of the Irish National Liberation Army whose factions coalesced in the aftermath of the supergrass trials...

(IPLO), an organisation founded by people who had resigned or been expelled from the INLA. The IPLO's initial aim was to destroy the INLA and replace it with their organisation. Five members of the INLA were killed by the IPLO, including their leaders Ta Power and John O'Reilly. The INLA retaliated with several killings of their own. After the INLA killed the IPLO's leader, Gerard Steenson

Gerard Steenson

Gerard Steenson was an Irish republican socialist paramilitary activist. He was a member of the Irish National Liberation Army group during the Troubles in Northern Ireland....

, a truce was reached. Although severely damaged by the IPLO's attacks, the INLA continued to exist. The IPLO, which was heavily involved in drug dealing, was put out of existence by the Provisional IRA in a large scale operation in 1992.

Directly after the feud in October 1987, the INLA received more damaging publicity when Dessie O'Hare

Dessie O'Hare

Dessie O'Hare , also known as "The Border Fox", is an Irish republican paramilitary, who was once the most wanted man in Ireland....

, an erstwhile INLA volunteer set up his own group called the 'Irish Revolutionary Brigade' and kidnapped a Dublin dentist named John O'Grady. O'Hare cut off two of O'Grady's fingers and sent them to his family in order to secure a ransom

Ransom

Ransom is the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release, or it can refer to the sum of money involved.In an early German law, a similar concept was called bad influence...

. O'Grady was eventually rescued and O'Hare's group arrested after several shootouts with armed Gardaí. The INLA disassociated itself from the action, issuing a statement saying O'Hare 'is not a member of the INLA'. O'Hare later rejoined the INLA while in prison.

In 1995, four members of the INLA, including chief of staff Hugh Torney

Hugh Torney

Hugh Torney was an Irish National Liberation Army paramilitary leader best known for his activities on behalf of the INLA and Irish Republican Socialist Party in a feud with the Irish People's Liberation Organisation , a grouping composed of disgruntled former INLA members in the...

, were arrested by Gardaí in Balbriggan

Balbriggan

Balbriggan is a town in the northern part of the administrative county of Fingal, within County Dublin, Ireland. The 2006 census population was 15,559 for Balbriggan and its environs.- Name :...

while trying to smuggle weapons from Dublin to Belfast

Belfast

Belfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

. Torney, with the support of two of his co-accused, called a ceasefire in exchange for favourable treatment by the Irish Government

Irish Government

The Government of Ireland is the cabinet that exercises executive authority in Ireland.-Members of the Government:Membership of the Government is regulated fundamentally by the Constitution of Ireland. The Government is headed by a prime minister called the Taoiseach...

. Since Torney, who was chief of staff, under the INLA's rules lacked the authority to call a ceasefire (because he was incarcerated), he and the two men who supported him were expelled from the INLA.

Torney and one of those men, Dessie McCleery, and founder member John Fennell were not going to surrender the leadership of the organisation. Their faction, known as the INLA/GHQ, assassinated the new INLA chief of staff, Gino Gallagher

Gino Gallagher

Gino Gallagher was an Irish republican who was Chief of Staff of the Irish National Liberation Army. He was killed in Belfast on 30 January 1996, while waiting in line for his unemployment benefit....

. After the INLA killed both McCleery and Torney in 1996, the rest of Torney's faction quietly disbanded.

Killing of Billy Wright

Billy WrightBilly Wright (loyalist)

William Stephen "Billy" Wright was a prominent Ulster loyalist during the period of violent religious/political conflict known as "The Troubles". He joined the Ulster Volunteer Force in 1975 and became commander of its Mid-Ulster Brigade in the early 1990s...

was the founder and leader of the Loyalist Volunteer Force

Loyalist Volunteer Force

The Loyalist Volunteer Force is a loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed by Billy Wright in 1996 when he and the Portadown unit of the Ulster Volunteer Force's Mid-Ulster Brigade was stood down by the UVF leadership. He had been the commander of the Mid-Ulster Brigade. The...

(LVF). Since July 1996, the group had launched a string of attacks on civilians (whom they identified as Catholics), killing at least five. In April 1997, Wright was sentenced to eight years in Maze Prison

Maze (HM Prison)

Her Majesty's Prison Maze was a prison in Northern Ireland that was used to house paramilitary prisoners during the Troubles from mid-1971 to mid-2000....

. On the morning of 27 December 1997, he was assassinated by three INLA prisoners – Christopher "Crip" McWilliams, John "Sonny" Glennon and John Kennaway – who were armed with two pistol

Pistol

When distinguished as a subset of handguns, a pistol is a handgun with a chamber that is integral with the barrel, as opposed to a revolver, wherein the chamber is separate from the barrel as a revolving cylinder. Typically, pistols have an effective range of about 100 feet.-History:The pistol...

s. He was shot as he travelled in a prison van (alongside another LVF prisoner, Norman Green and one prison officer) from one part of the prison to another. Kennaway held the driver hostage and Glennon gave cover with a .22 Derringer pistol while McWilliams opened the side door and fired seven shots at Wright with his PA63 semi-automatic

FEG PA-63

The FÉG PA-63 is a semi-automatic pistol designed and manufactured by the FÉGARMY Arms Factory of Hungary.-History:FÉGARMY Arms Factory of Hungary started producing Walther PP/PPK clones in the late 1940s starting with their Model 48 which differed from the Walther PP only in minor details...

. After killing Wright, the three volunteers handed themselves over to prison guards. They also handed over a statement, which read:

That night, LVF gunmen opened fire on a disco

Disco

Disco is a genre of dance music. Disco acts charted high during the mid-1970s, and the genre's popularity peaked during the late 1970s. It had its roots in clubs that catered to African American, gay, psychedelic, and other communities in New York City and Philadelphia during the late 1960s and...

in a mainly nationalist area of Dungannon

Dungannon

Dungannon is a medium-sized town in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. It is the third-largest town in the county and a population of 11,139 people was recorded in the 2001 Census. In August 2006, Dungannon won Ulster In Bloom's Best Kept Town Award for the fifth time...

. Four civilians were wounded and a former Provisional IRA volunteer was killed in the attack.

The nature of Wright's killing led to speculation that prison authorities colluded with the INLA to have him killed, as he was a danger to the peace process. The INLA strongly denied these rumours, and published a detailed account of the assassination in the March/April 1999 issue of The Starry Plough

The Starry Plough (newspaper)

The Starry Plough is the official newspaper of the Irish Republican Socialist Party. It states on its website: "The Starry Plough is the only paper that stands firmly against British rule and the destruction of capitalism in Ireland." The paper also focuses on socialist solidarity issues around the...

newspaper.

Ceasefire

The INLA declared a ceasefire on 22 August 1998. When calling its ceasefire, the INLA acknowledged the 'faults and grievous errors in our prosecution of the war'. The INLA admitted that innocent people had been killed and injured 'and at times our actions as a liberation army fell far short of what they should have been'. The INLA went on to accept the massive vote in favour of the Good Friday AgreementBelfast Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement or Belfast Agreement , sometimes called the Stormont Agreement, was a major political development in the Northern Ireland peace process...

– an arrangement it had opposed during the 1998 referendum – by the people of Ireland.

'The will of the Irish people is clear. It is now time to silence the guns and allow the working classes the time and the opportunity to advance their demands and their needs.'

Although the INLA does not support the Good Friday Agreement, it does not call for a return to armed struggle on behalf of republicans either. An INLA statement released in 1999 declared, "we do not see a return to armed struggle as a viable option at the present time"

Post-ceasefire activities

The Independent Monitoring Commission

Independent Monitoring Commission

The Independent Monitoring Commission was an organization founded on 7 January 2004, by an agreement between the British and Irish governments, signed in Dublin on 25 November 2003...

, which monitors paramilitary activity in Northern Ireland, claimed in a November 2004 report that the INLA was heavily involved in criminality. In 1997, an INLA man named John Morris was shot dead by Gardaí (Irish Police) in Dublin during the attempted robbery of a newspaper distributor's depot in Inchicore

Inchicore

-Location and access:Located five kilometres due west of the city centre, Inchicore lies south of the River Liffey, west of Kilmainham, north of Drimnagh and east of Ballyfermot. The majority of Inchicore is in the Dublin 8 postal district...

. Three other INLA members were arrested in the incident. In 1999, the INLA in Dublin became involved in a feud with a criminal gang in the city. After a young INLA man named Patrick Campbell was killed by drug dealers, the INLA carried out several shootings in reprisal, including at least one killing. Irish journalist Paul Williams has also claimed the INLA, especially in Dublin, is now primarily a front for organised crime. The IRSP and INLA deny these allegations, arguing that no one has been simultaneously convicted of membership in the INLA and of drug offences. The IRSP and the INLA have both strongly denied any involvement with drug dealing, stating that the INLA has threatened criminals which it claims have falsely used its name.

In 2006, the INLA claimed to have put at least two drugs gangs out of business in Northern Ireland. After their raid on a criminal organisation based in the north-west, they released a statement saying that "the Irish National Liberation Army will not allow the working class people of this city to be used as cannon fodder by these criminals whose only concern is profit by whatever means available to them."

The October 2006 Independent Monitoring Commission

Independent Monitoring Commission

The Independent Monitoring Commission was an organization founded on 7 January 2004, by an agreement between the British and Irish governments, signed in Dublin on 25 November 2003...

(IMC) report stated that the INLA "was not capable of undertaking a sustained campaign [against the United Kingdom], nor does it aspire to".

In December 2007, disturbances broke out at an INLA parade in the Bogside

Bogside

The Bogside is a neighbourhood outside the city walls of Derry, Northern Ireland. The area has been a focus point for many of the events of The Troubles, from the Battle of the Bogside and Bloody Sunday in the 1960s and 1970s...

in Derry

Derry

Derry or Londonderry is the second-biggest city in Northern Ireland and the fourth-biggest city on the island of Ireland. The name Derry is an anglicisation of the Irish name Doire or Doire Cholmcille meaning "oak-wood of Colmcille"...

between watchers and Police Service of Northern Ireland

Police Service of Northern Ireland

The Police Service of Northern Ireland is the police force that serves Northern Ireland. It is the successor to the Royal Ulster Constabulary which, in turn, was the successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary in Northern Ireland....

(PSNI) officers attempting to arrest four of the marchers.

In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Independent Monitoring Commission

Independent Monitoring Commission

The Independent Monitoring Commission was an organization founded on 7 January 2004, by an agreement between the British and Irish governments, signed in Dublin on 25 November 2003...

reports the INLA were said to have remained a threat, with a desire to mount more attack, and could well be more dangerous in the future, although in the meantime it was largely a criminal enterprise

Business

A business is an organization engaged in the trade of goods, services, or both to consumers. Businesses are predominant in capitalist economies, where most of them are privately owned and administered to earn profit to increase the wealth of their owners. Businesses may also be not-for-profit...

. In the same vein they committed the murder of Brian McGlynn on 3 June 2007 during the span of the former's report. This murder was said to have occurred because the victim used the INLA name in the drug trade

Illegal drug trade

The illegal drug trade is a global black market, dedicated to cultivation, manufacture, distribution and sale of those substances which are subject to drug prohibition laws. Most jurisdictions prohibit trade, except under license, of many types of drugs by drug prohibition laws.A UN report said the...

. On 24 June 2008, the INLA was said to have committed the murder of Emmett Shiels, although the IMC report did indicate the investigation was continuing.

It was also said to be partaking in "serious crimes" such as drug dealing, extortion

Extortion

Extortion is a criminal offence which occurs when a person unlawfully obtains either money, property or services from a person, entity, or institution, through coercion. Refraining from doing harm is sometimes euphemistically called protection. Extortion is commonly practiced by organized crime...

, robbery

Robbery

Robbery is the crime of taking or attempting to take something of value by force or threat of force or by putting the victim in fear. At common law, robbery is defined as taking the property of another, with the intent to permanently deprive the person of that property, by means of force or fear....

, fuel laundering and smuggling

Smuggling

Smuggling is the clandestine transportation of goods or persons, such as out of a building, into a prison, or across an international border, in violation of applicable laws or other regulations.There are various motivations to smuggle...

. Furthermore, the INLA and CIRA are noted to have co-operated.

On 15 February 2009 the INLA claimed responsibility for the shooting dead of Derry drug-dealer Jim McConnell.

In March 2009 it was reported that the INLA had stood down its Dublin Brigade in order to allow its army council to carry out an internal investigation into allegations of drug-dealing and criminality. The INLA denied it as an organisation was involved in drug dealing and went on to say that "As a result of evidence presented to us, we are investigating the activities of people associated with us in [Dublin]. Pending that outcome, we have stood down several people." A short time later the INLA's Dublin Commander; Declan "Whacker" Duffy publicly disassociated himself from the organisation. Duffy criticized the INLA leadership stating that "You would imagine if there was a thorough investigation being carried out by the INLA they would have at least came and spoke to me." He went on to state that: "I can’t deny that I’m disappointed with the way the INLA has handled things but at the same time I’m not going to get into a sniping match with them."

On 19 August 2009 the INLA shot and wounded a man in Derry. The INLA claimed that the man was involved in drug dealing although the injured man and his family denied the allegation. However, in a newspaper article on 28 August the victim retracted his previous statement and admitted that he had been involved in small scale drug-dealing but has since ceased these activities.

End of armed campaign

On 11 October 2009, speaking at the graveside of its founding member, Seamus CostelloSeamus Costello

Seamus Costello was a leader of Official Sinn Féin and the Official Irish Republican Army and latterly of the Irish Republican Socialist Party and the Irish National Liberation Army ....

, in Bray

Bray

Bray is a town in north County Wicklow, Ireland. It is a busy urban centre and seaside resort, with a population of 31,901 making it the fourth largest in Ireland as of the 2006 census...

, the INLA formally announced an end to its armed campaign, stating the current political framework allowed for the pursuit of its goals through peaceful, democratic means. Martin McMonagle from Derry said: "The Republican Socialist Movement has been informed by the INLA that following a process of serious debate ... it has concluded that the armed struggle is over. The objective of a 32-county socialist republic will be best achieved through exclusively peaceful political struggle". They laid a wreath beforehand.

The governments of Britain and Ireland were informed. Hillary Rodham Clinton

Hillary Rodham Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton is the 67th United States Secretary of State, serving in the administration of President Barack Obama. She was a United States Senator for New York from 2001 to 2009. As the wife of the 42nd President of the United States, Bill Clinton, she was the First Lady of the...

of the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

was due to visit Belfast

Belfast

Belfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

the following day. Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin is a left wing, Irish republican political party in Ireland. The name is Irish for "ourselves" or "we ourselves", although it is frequently mistranslated as "ourselves alone". Originating in the Sinn Féin organisation founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith, it took its current form in 1970...

's Gerry Adams

Gerry Adams

Gerry Adams is an Irish republican politician and Teachta Dála for the constituency of Louth. From 1983 to 1992 and from 1997 to 2011, he was an abstentionist Westminster Member of Parliament for Belfast West. He is the president of Sinn Féin, the second largest political party in Northern...

was doubtful but added: "However, if it is followed by the actions that are necessary, this is a welcome development". On 6 February 2010, days before the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning

Independent International Commission on Decommissioning

The Independent International Commission on Decommissioning was established to oversee the decommissioning of paramilitary weapons in Northern Ireland, as part of the peace process.-Legislation and organisation:...

(IICD) was due to disband, the INLA revealed that it had decommissioned its weapons over the preceding few weeks. Had the INLA retained its weapons beyond 9 February, the date on which the legislation under which the IICD operated ended, then they would have been treated as belonging to common criminals rather than remnants from the Troubles.

The decommissioning was confirmed by General John de Chastelain

John de Chastelain

Alfred John Gardyne Drummond de Chastelain is a retired Canadian soldier and diplomat.De Chastelain was born in Romania and educated in England and in Scotland before his family immigrated to Canada in 1954...

of the IICD on 8 February 2010. On the same day INLA spokesman Martin McMonagle said that the INLA made "no apology for [its] part in the conflict" but they believed in the "primacy of politics" to "advance the working class struggle in Ireland".

Deaths as a result of activity

According to the University of UlsterUniversity of Ulster

The University of Ulster is a multi-campus, co-educational university located in Northern Ireland. It is the largest single university in Ireland, discounting the federal National University of Ireland...

's Sutton database, the INLA was responsible for 113 killings during "the Troubles", between 1969 and 2001. According to the INLA's Roll of Honour, 33 of its members were killed during the conflict.

| Status | Deaths | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| British security forces | 46 | 41% |

| Irish security forces | 2 | 2% |

| Civilian | 39 | 34% |

| Civilian political activist | 3 | 3% |

| Republican paramilitary | 16 | 14% |

| Loyalist paramilitary | 7 | 6% |

Sources

- Jack Holland, Henry McDonald, INLA – Deadly Divisions'

- The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, ISBN 1844881202

- CAIN project

- Coogan, Tim Pat, The IRA, Fontana Books, ISBN 0-00-636943-X

- The Starry Plough – IRSP newspaper