Battle of the Bogside

Encyclopedia

The Battle of the Bogside was a very large communal riot

that took place during 12–14 August 1969 in Derry

, Northern Ireland. The fighting was between residents of the Bogside

area (allied under the Derry Citizens' Defence Association) and the Royal Ulster Constabulary

(RUC).

The rioting erupted after the RUC attempted to disperse Irish nationalists

who were protesting against a loyalist

Apprentice Boys

parade along the city walls, past the nationalist Bogside. Rioting continued for three days in the Bogside. The RUC was unable to enter the area and the British Army

was deployed to restore control. The riot, which sparked widespread violence elsewhere

in Northern Ireland, is commonly seen as one of the first major confrontations in the conflict known as the Troubles

.

and nationalist

population. In 1961, for example, the population was 53,744, of which 36,049 was Catholic and 17,695 Protestant. However after the partition of Ireland

in 1921, it had been ruled by the Unionist

-dominated government of Northern Ireland

.

As a result, although Catholics made up 60% of Derry's population in 1961, due to the division of electoral wards, unionists had a majority of 12 seats to 8 on the city council. When there arose the possibility of Nationalists gaining one of the Unionist wards, the boundaries were redrawn to maintain Unionist control. Control of the city council gave Unionists control over the allocation of public housing, which they allocated in such a way as to keep the Catholic population in a limited number of wards. This policy had the additional effect of creating a housing shortage for Catholics.

Secondly, only owners or tenants of a dwelling and their spouses were allowed to vote in local elections. Nationalists argued that these practices were retained by Unionists after their abolition in Great Britain in 1945 in order to reduce the anti-Unionist vote. Figures show that, in Derry city, Nationalists comprised 61.6% of parliamentary electors, but only 54.7% of local government electors. Catholics also alleged discrimination in employment.

Another grievance, highlighted by the Cameron Commission into the riots of 1969, was the issue of perceived regional bias; where Northern Ireland government decisions alleged to favour the mainly Protestant east of Northern Ireland rather than the mainly Catholic west. Examples of such controversial decisions affecting Derry were the decision to close the anti-submarine training school in 1965, adding 600 to an unemployment figure already approaching 20%; the decision to site Northern Ireland's new town at Craigavon

and the siting of Northern Ireland's second University in the mainly unionist town of Coleraine

rather than Derry, which was four times larger.

, with the intention of forcing the government of Northern Ireland to change their housing policies. This groups founders were mostly local members of the Northern Ireland Labour Party

, such as Eamonn McCann

and members of the James Connolly

Republican Club (the Northern manifestation of Sinn Féin

, which was banned in Northern Ireland). The Housing Action Committee took direct action

such as blocking roads and attending local council meetings uninvited in order to force them to house Catholic families who had been on council's housing waiting list for a long time. By the summer of 1968, this group had linked up with the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

and were agitating for a broader program of reform within Northern Ireland.

On 5 October 1968, these activists organised a march through the centre of Derry. However, the demonstration was banned. When the marchers, including Members of Parliament Eddie McAteer

and Ivan Cooper

, defied this ban they were batoned by the RUC. The RUC's actions were televised and caused widespread anger in nationalist circles. The following day, 4000 people demonstrated in solidarity with the marchers in Guildhall Square in the centre of Derry. This march passed off peacefully, as did another demonstration attended by up to 15,000 people on 16 November. However, these incidents proved to be the start of an escalating pattern of civil unrest, that culminated in the events of August 1969.

from Belfast

to Derry was attacked by loyalists at Burntollet

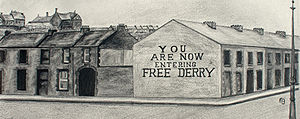

, five miles outside Derry. It is alleged that the RUC failed to protect the march. When the marchers (many of whom were injured) arrived in Derry on 5 January, rioting broke out between their supporters and the RUC. That night, RUC officers broke into homes in the Catholic Bogside area and assaulted several residents. An inquiry led by Lord Cameron concluded that, "a number of policemen were guilty of misconduct, which involved assault and battery, malicious damage to property...and the use of provocative sectarian and political slogans". After this point, barricade

s were set up in the Bogside and vigilante

patrols organised to keep the RUC out. It was at this point that the famous mural with the slogan "You are now entering Free Derry

" was painted on the corner of Columbs Street by a local activist named John Casey.

On 19 April there were clashes between NICRA marchers, loyalists and the RUC in the Bogside area. RUC officers entered the house of Samuel Devenny (42), a local Catholic who was not involved in the riot, and severely beat him with batons. His teenage daughters were also beaten in the attack. Devenny died of his injuries on 17 July and he is sometimes referred to as the first victim of The Troubles. Others consider John Patrick Scullion, who was killed 11 June 1966 by the UVF, to have been the first victim of the conflict.

On 12 July ("The Twelfth

") there was further rioting in Derry, nearby Dungiven

, and Belfast. The violence arose out of the yearly Orange Order marches. During the clashes in Dungiven, Catholic civilian Francis McCloskey (67) was beaten with batons by RUC officers and died of his injuries the following day. Following these riots, Irish republicans

in Derry set up the Derry Citizens Defence Association

, with the intention of preparing for future disturbances. The members of the DCDA were initially Republican Club (and possibly IRA) activists, but they were joined by many other left-wing activists and local people. This group stated their aim as firstly to keep the peace, but if this failed, to organise the defence of the Bogside. To this end, they stockpiled materials for barricades and missiles, ahead of the Apprentice Boys of Derry

march on 12 August.

in 1689 and was considered highly provocative by many Catholics. Derry activist Eamonn McCann wrote that the march, "was regarded as a calculated insult to the Derry Catholics".

Although the march did not pass through the Bogside, it passed close to it at the junction of Waterloo Place and William Street. It was here that trouble broke out. Initially, taunts were exchanged between the loyalists and Bogsiders. Stones were then thrown from both sides for a period, before the police forced the nationalists into Rossville Street and the Bogside itself. They were followed by local supporters of the Apprentice Boys, and the confrontation escalated.

Large crowds turned out in the Bogside, pelted the police with stones and Molotov cocktail

s, and manned pre-prepared barricades to block their progress - which the RUC tried to clear with armoured cars. Out of 59 officers who made the initial incursion, 43 were treated for injuries.

The actions of the Bogside residents were co-ordinated to some extent. The Derry Citizens Defence Association

The actions of the Bogside residents were co-ordinated to some extent. The Derry Citizens Defence Association

set up a headquarters in the house of Paddy Doherty

in Westland Street and tried to supervise the making of petrol bombs and the positioning of barricades. They also set up "Radio Free Derry." Many local people, however, joined in the rioting on their own initiative and impromptu leaders also emerged, such as Bernadette Devlin, Eamonn McCann

and others.

Locals youths climbed onto the roof of the High Flats on Rossville Street, from where they bombarded the RUC below with missiles. When the advantage that this position possessed was realised, the youths were kept supplied with stones and petrol bombs.

The RUC were in many respects badly prepared for the "battle". Their riot shield

s were too small and did not protect their whole bodies. In addition, their uniforms were not flame resistant and a number were badly burned by petrol bombs. They possessed armoured cars and guns, but were not permitted to use them. Moreover, there was no system in place to relieve officers, with the result that the same policemen had to serve in the rioting for three days without rest.

The police responded to this situation by flooding the area with CS gas

, which caused a range of respiratory injuries among the local people. A total of 1,091 canisters containing 12.5g of CS; and 14 canisters containing 50g of CS, were released in the densely populated residential area. After two days of almost continuous rioting, during which police were drafted in from all over Northern Ireland, the RUC were exhausted, and were snatching sleep in doorways whenever the opportunity allowed.

On 13 August, Jack Lynch

, Taoiseach

of the Republic of Ireland made a televised speech about the events in Derry, in which he said that he "could not stand by and watch innocent people injured and perhaps worse." He promised to send the Irish Army

to the border and to set up field hospitals for those injured in the fighting. Lynch's words were widely interpreted in the Bogside as promising that Irish troops were about to be sent to their aid. Unionists were appalled at this prospect, which they saw as a threatened invasion of Northern Ireland. In fact, although the Irish Army was indeed sent to the border, they restricted their activities to providing medical care for the injured.

By 14 August, the rioting in the Bogside had reached a critical point. Almost the entire community there had been mobilised by this point, many galvanised by false rumours that St Eugene's Cathedral

had been attacked by the police. The RUC were also beginning to use firearms. Two rioters were shot and injured in Great James' Street. The B-Specials

, an auxiliary, mostly Protestant police force, much feared by Catholics for their role in killings in the 1920s, were called up and sent to Derry, provoking fears of a massacre on the part of the Bogsiders.

On the afternoon of the 14th, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

, James Chichester-Clark

, took the unprecedented step of requesting the British Prime Minister

Harold Wilson

for troops

to be sent to Derry. Soon afterwards a company of the Prince of Wales Own Regiment

relieved the police, with orders to separate the RUC and the Bogsiders, but not to attempt to breach the barricades and enter the Bogside itself. This marked the first direct intervention of the London government in Ireland since partition

. The British troops were at first welcomed by the Bogside residents as a neutral force compared to the RUC and especially the B-Specials.

Only a handful of radicals in Bogside, notably Bernadette Devlin, opposed the deployment of British troops. This good relationship did not last long however, as the Troubles escalated.

Over 1000 people had been injured in the rioting in Derry, but no one was killed. A total of 691 RUC men were deployed in Derry during the riot, of whom only 255 were still in action at 12.30 on the 15th. Manpower then fluctuated for the rest of the afternoon: the numbers recorded are 318, 304, 374, 333, 285 and finally 327 at 5.30 pm While some of the fluctuation in numbers can be put down to exhaustion rather than injury, these figures indicate that the RUC suffered at least 350 serious injuries. How many Bogsiders were injured is unclear, as many injuries were never reported.

for people to stretch police resources to aid the Bogsiders led to rioting in Belfast

and elsewhere, which left five Catholics and two Protestants dead. That same night (the 14th) a loyalist mob burned all of the Catholic homes on Bombay Street. Over 1,500 Catholics were expelled from their homes in Belfast. Taken together with events in Derry, this period of rioting is widely seen as the point in which The Troubles

escalated from a situation of civil unrest to one of a three-way armed conflict between nationalists, state forces and unionists.

in October 2004.

Riot

A riot is a form of civil disorder characterized often by what is thought of as disorganized groups lashing out in a sudden and intense rash of violence against authority, property or people. While individuals may attempt to lead or control a riot, riots are thought to be typically chaotic and...

that took place during 12–14 August 1969 in Derry

Derry

Derry or Londonderry is the second-biggest city in Northern Ireland and the fourth-biggest city on the island of Ireland. The name Derry is an anglicisation of the Irish name Doire or Doire Cholmcille meaning "oak-wood of Colmcille"...

, Northern Ireland. The fighting was between residents of the Bogside

Bogside

The Bogside is a neighbourhood outside the city walls of Derry, Northern Ireland. The area has been a focus point for many of the events of The Troubles, from the Battle of the Bogside and Bloody Sunday in the 1960s and 1970s...

area (allied under the Derry Citizens' Defence Association) and the Royal Ulster Constabulary

Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary was the name of the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2000. Following the awarding of the George Cross in 2000, it was subsequently known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC. It was founded on 1 June 1922 out of the Royal Irish Constabulary...

(RUC).

The rioting erupted after the RUC attempted to disperse Irish nationalists

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

who were protesting against a loyalist

Ulster loyalism

Ulster loyalism is an ideology that is opposed to a united Ireland. It can mean either support for upholding Northern Ireland's status as a constituent part of the United Kingdom , support for Northern Ireland independence, or support for loyalist paramilitaries...

Apprentice Boys

Apprentice Boys of Derry

The Apprentice Boys of Derry is a Protestant fraternal society with a worldwide membership of over 80,000, founded in 1814. They are based in the city of Derry, Northern Ireland. However, there are Clubs and branches across Ireland, Great Britain and further afield...

parade along the city walls, past the nationalist Bogside. Rioting continued for three days in the Bogside. The RUC was unable to enter the area and the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

was deployed to restore control. The riot, which sparked widespread violence elsewhere

1969 Northern Ireland Riots

During 12–17 August 1969, Northern Ireland was rocked by intense political and sectarian rioting. There had been sporadic violence throughout the year arising from the civil rights campaign, which was demanding an end to government discrimination against Irish Catholics and nationalists...

in Northern Ireland, is commonly seen as one of the first major confrontations in the conflict known as the Troubles

The Troubles

The Troubles was a period of ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland which spilled over at various times into England, the Republic of Ireland, and mainland Europe. The duration of the Troubles is conventionally dated from the late 1960s and considered by many to have ended with the Belfast...

.

Background

Tensions had been building in Derry for over a year before the Battle of the Bogside. In part, this was due to long-standing grievances held by much of the city's population. The city had a majority CatholicIrish Catholic

Irish Catholic is a term used to describe people who are both Roman Catholic and Irish .Note: the term is not used to describe a variant of Catholicism. More particularly, it is not a separate creed or sect in the sense that "Anglo-Catholic", "Old Catholic", "Eastern Orthodox Catholic" might be...

and nationalist

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

population. In 1961, for example, the population was 53,744, of which 36,049 was Catholic and 17,695 Protestant. However after the partition of Ireland

Partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland was the division of the island of Ireland into two distinct territories, now Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland . Partition occurred when the British Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1920...

in 1921, it had been ruled by the Unionist

Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party – sometimes referred to as the Official Unionist Party or, in a historic sense, simply the Unionist Party – is the more moderate of the two main unionist political parties in Northern Ireland...

-dominated government of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

.

Nationalist grievances

Unionists maintained political control of Derry by two means. Firstly, electoral wards were designed so as to give unionists a majority in the city. The "Londonderry County Borough", which covered the city, had been won by nationalists in 1921. It was recovered by unionists, however, following re-drawing of electoral boundaries by the unionist government in the Northern Ireland parliament.As a result, although Catholics made up 60% of Derry's population in 1961, due to the division of electoral wards, unionists had a majority of 12 seats to 8 on the city council. When there arose the possibility of Nationalists gaining one of the Unionist wards, the boundaries were redrawn to maintain Unionist control. Control of the city council gave Unionists control over the allocation of public housing, which they allocated in such a way as to keep the Catholic population in a limited number of wards. This policy had the additional effect of creating a housing shortage for Catholics.

Secondly, only owners or tenants of a dwelling and their spouses were allowed to vote in local elections. Nationalists argued that these practices were retained by Unionists after their abolition in Great Britain in 1945 in order to reduce the anti-Unionist vote. Figures show that, in Derry city, Nationalists comprised 61.6% of parliamentary electors, but only 54.7% of local government electors. Catholics also alleged discrimination in employment.

Another grievance, highlighted by the Cameron Commission into the riots of 1969, was the issue of perceived regional bias; where Northern Ireland government decisions alleged to favour the mainly Protestant east of Northern Ireland rather than the mainly Catholic west. Examples of such controversial decisions affecting Derry were the decision to close the anti-submarine training school in 1965, adding 600 to an unemployment figure already approaching 20%; the decision to site Northern Ireland's new town at Craigavon

Craigavon

Craigavon is a settlement in north County Armagh, Northern Ireland. It was a planned settlement that was begun in 1965 and named after Northern Ireland's first Prime Minister — James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon. It was intended to be a linear city incorporating Lurgan and Portadown, but this plan...

and the siting of Northern Ireland's second University in the mainly unionist town of Coleraine

Coleraine

Coleraine is a large town near the mouth of the River Bann in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It is northwest of Belfast and east of Derry, both of which are linked by major roads and railway connections...

rather than Derry, which was four times larger.

Activism

In March 1968, a small number of activists in the city founded the Derry Housing Action CommitteeDerry Housing Action Committee

The Derry Housing Action Committee , was an organisation formed in 1968 in Derry, Northern Ireland to protest about housing conditions and provision....

, with the intention of forcing the government of Northern Ireland to change their housing policies. This groups founders were mostly local members of the Northern Ireland Labour Party

Northern Ireland Labour Party

The Northern Ireland Labour Party was an Irish political party which operated from 1924 until 1987.In 1913 the British Labour Party resolved to give the recently formed Irish Labour Party exclusive organising rights in Ireland...

, such as Eamonn McCann

Eamonn McCann

Eamonn McCann is an Irish journalist, author and political activist.-Life:McCann was born and has lived most of his life in Derry. He was educated at St. Columb's College in the city. He is prominently featured in the documentary film The Boys of St...

and members of the James Connolly

James Connolly

James Connolly was an Irish republican and socialist leader. He was born in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, to Irish immigrant parents and spoke with a Scottish accent throughout his life. He left school for working life at the age of 11, but became one of the leading Marxist theorists of...

Republican Club (the Northern manifestation of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin is a left wing, Irish republican political party in Ireland. The name is Irish for "ourselves" or "we ourselves", although it is frequently mistranslated as "ourselves alone". Originating in the Sinn Féin organisation founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith, it took its current form in 1970...

, which was banned in Northern Ireland). The Housing Action Committee took direct action

Direct action

Direct action is activity undertaken by individuals, groups, or governments to achieve political, economic, or social goals outside of normal social/political channels. This can include nonviolent and violent activities which target persons, groups, or property deemed offensive to the direct action...

such as blocking roads and attending local council meetings uninvited in order to force them to house Catholic families who had been on council's housing waiting list for a long time. By the summer of 1968, this group had linked up with the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association was an organisation which campaigned for equal civil rights for the all the people in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s...

and were agitating for a broader program of reform within Northern Ireland.

On 5 October 1968, these activists organised a march through the centre of Derry. However, the demonstration was banned. When the marchers, including Members of Parliament Eddie McAteer

Eddie McAteer

Eddie McAteer was an nationalist politician in Northern Ireland.Born in Coatbridge, Scotland, McAteer's family moved to Derry in Northern Ireland while he was young. In 1930 he joined the Inland Revenue, where he worked until 1944. He then became an accountant and more actively involved in politics...

and Ivan Cooper

Ivan Cooper

Ivan Averill Cooper is a former politician from Northern Ireland who was a Member of the Parliament of Northern Ireland, and founding member of the SDLP...

, defied this ban they were batoned by the RUC. The RUC's actions were televised and caused widespread anger in nationalist circles. The following day, 4000 people demonstrated in solidarity with the marchers in Guildhall Square in the centre of Derry. This march passed off peacefully, as did another demonstration attended by up to 15,000 people on 16 November. However, these incidents proved to be the start of an escalating pattern of civil unrest, that culminated in the events of August 1969.

January to July, 1969

In January 1969, a march by the radical nationalist group People's DemocracyPeople's Democracy

People's Democracy was a political organisation that, while supporting the campaign for civil rights for Northern Ireland's Catholic minority, stated that such rights could only be achieved through the establishment of a socialist republic for all of Ireland...

from Belfast

Belfast

Belfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

to Derry was attacked by loyalists at Burntollet

Burntollet

Burntollet was the setting for an infamous attack during the so called Troubles of Northern Ireland. A nationalist march from Belfast to Derry was attacked whilst passing through Burntollet on the 4th of January, 1969 . A loyalist crowd, numbering in the region of 200, attacked the civil rights...

, five miles outside Derry. It is alleged that the RUC failed to protect the march. When the marchers (many of whom were injured) arrived in Derry on 5 January, rioting broke out between their supporters and the RUC. That night, RUC officers broke into homes in the Catholic Bogside area and assaulted several residents. An inquiry led by Lord Cameron concluded that, "a number of policemen were guilty of misconduct, which involved assault and battery, malicious damage to property...and the use of provocative sectarian and political slogans". After this point, barricade

Barricade

Barricade, from the French barrique , is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction...

s were set up in the Bogside and vigilante

Vigilante

A vigilante is a private individual who legally or illegally punishes an alleged lawbreaker, or participates in a group which metes out extralegal punishment to an alleged lawbreaker....

patrols organised to keep the RUC out. It was at this point that the famous mural with the slogan "You are now entering Free Derry

Free Derry

Free Derry was a self-declared autonomous nationalist area of Derry, Northern Ireland, between 1969 and 1972. Its name was taken from a sign painted on a gable wall in the Bogside in January 1969 which read, “You are now entering Free Derry"...

" was painted on the corner of Columbs Street by a local activist named John Casey.

On 19 April there were clashes between NICRA marchers, loyalists and the RUC in the Bogside area. RUC officers entered the house of Samuel Devenny (42), a local Catholic who was not involved in the riot, and severely beat him with batons. His teenage daughters were also beaten in the attack. Devenny died of his injuries on 17 July and he is sometimes referred to as the first victim of The Troubles. Others consider John Patrick Scullion, who was killed 11 June 1966 by the UVF, to have been the first victim of the conflict.

On 12 July ("The Twelfth

The Twelfth

The Twelfth is a yearly Protestant celebration held on 12 July. It originated in Ireland during the 18th century. It celebrates the Glorious Revolution and victory of Protestant king William of Orange over Catholic king James II at the Battle of the Boyne...

") there was further rioting in Derry, nearby Dungiven

Dungiven

Dungiven is a small town and townland in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It is on the main A6 Belfast to Derry road. It lies where the rivers Roe, Owenreagh and Owenbeg meet at the foot of the Benbradagh. Nearby is the Glenshane Pass, where the road rises to over...

, and Belfast. The violence arose out of the yearly Orange Order marches. During the clashes in Dungiven, Catholic civilian Francis McCloskey (67) was beaten with batons by RUC officers and died of his injuries the following day. Following these riots, Irish republicans

Irish Republicanism

Irish republicanism is an ideology based on the belief that all of Ireland should be an independent republic.In 1801, under the Act of Union, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland merged to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

in Derry set up the Derry Citizens Defence Association

Derry Citizens Defence Association

The Derry Citizens' Defence Association , was an organisation set up in July 1969 in response to a perceived threat to the nationalist community of Derry in connection with the annual parade of the Apprentice Boys of Derry on 12 August. This followed clashes with the Royal Ulster Constabulary in...

, with the intention of preparing for future disturbances. The members of the DCDA were initially Republican Club (and possibly IRA) activists, but they were joined by many other left-wing activists and local people. This group stated their aim as firstly to keep the peace, but if this failed, to organise the defence of the Bogside. To this end, they stockpiled materials for barricades and missiles, ahead of the Apprentice Boys of Derry

Apprentice Boys of Derry

The Apprentice Boys of Derry is a Protestant fraternal society with a worldwide membership of over 80,000, founded in 1814. They are based in the city of Derry, Northern Ireland. However, there are Clubs and branches across Ireland, Great Britain and further afield...

march on 12 August.

The Apprentice Boys march

The annual Apprentice Boys parade on 12 August commemorated the Protestant victory in the Siege of DerrySiege of Derry

The Siege of Derry took place in Ireland from 18 April to 28 July 1689, during the Williamite War in Ireland. The city, a Williamite stronghold, was besieged by a Jacobite army until it was relieved by Royal Navy ships...

in 1689 and was considered highly provocative by many Catholics. Derry activist Eamonn McCann wrote that the march, "was regarded as a calculated insult to the Derry Catholics".

Although the march did not pass through the Bogside, it passed close to it at the junction of Waterloo Place and William Street. It was here that trouble broke out. Initially, taunts were exchanged between the loyalists and Bogsiders. Stones were then thrown from both sides for a period, before the police forced the nationalists into Rossville Street and the Bogside itself. They were followed by local supporters of the Apprentice Boys, and the confrontation escalated.

Large crowds turned out in the Bogside, pelted the police with stones and Molotov cocktail

Molotov cocktail

The Molotov cocktail, also known as the petrol bomb, gasoline bomb, Molotov bomb, fire bottle, fire bomb, or simply Molotov, is a generic name used for a variety of improvised incendiary weapons...

s, and manned pre-prepared barricades to block their progress - which the RUC tried to clear with armoured cars. Out of 59 officers who made the initial incursion, 43 were treated for injuries.

The Battle

Derry Citizens Defence Association

The Derry Citizens' Defence Association , was an organisation set up in July 1969 in response to a perceived threat to the nationalist community of Derry in connection with the annual parade of the Apprentice Boys of Derry on 12 August. This followed clashes with the Royal Ulster Constabulary in...

set up a headquarters in the house of Paddy Doherty

Paddy Doherty

Patrick Doherty is a former activist in Derry, Northern Ireland.As vice-chairman of the Derry Citizens Defence Association Doherty played a major role in the events of August 1969 which culminated in the Battle of the Bogside, and was a leading figure in Free Derry in the years following its...

in Westland Street and tried to supervise the making of petrol bombs and the positioning of barricades. They also set up "Radio Free Derry." Many local people, however, joined in the rioting on their own initiative and impromptu leaders also emerged, such as Bernadette Devlin, Eamonn McCann

Eamonn McCann

Eamonn McCann is an Irish journalist, author and political activist.-Life:McCann was born and has lived most of his life in Derry. He was educated at St. Columb's College in the city. He is prominently featured in the documentary film The Boys of St...

and others.

Locals youths climbed onto the roof of the High Flats on Rossville Street, from where they bombarded the RUC below with missiles. When the advantage that this position possessed was realised, the youths were kept supplied with stones and petrol bombs.

The RUC were in many respects badly prepared for the "battle". Their riot shield

Riot shield

Riot shields are lightweight protection devices deployed by police and some military organizations. Most are a clear polycarbonate, though some are constructed of light metals with a view hole. Riot shields are almost exclusively long enough to cover an average sized man from the top of the head to...

s were too small and did not protect their whole bodies. In addition, their uniforms were not flame resistant and a number were badly burned by petrol bombs. They possessed armoured cars and guns, but were not permitted to use them. Moreover, there was no system in place to relieve officers, with the result that the same policemen had to serve in the rioting for three days without rest.

The police responded to this situation by flooding the area with CS gas

CS gas

2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile is the defining component of a "tear gas" commonly referred to as CS gas, which is used as a riot control agent...

, which caused a range of respiratory injuries among the local people. A total of 1,091 canisters containing 12.5g of CS; and 14 canisters containing 50g of CS, were released in the densely populated residential area. After two days of almost continuous rioting, during which police were drafted in from all over Northern Ireland, the RUC were exhausted, and were snatching sleep in doorways whenever the opportunity allowed.

On 13 August, Jack Lynch

Jack Lynch

John Mary "Jack" Lynch was the Taoiseach of Ireland, serving two terms in office; from 1966 to 1973 and 1977 to 1979....

, Taoiseach

Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government or prime minister of Ireland. The Taoiseach is appointed by the President upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Oireachtas , and must, in order to remain in office, retain the support of a majority in the Dáil.The current Taoiseach is...

of the Republic of Ireland made a televised speech about the events in Derry, in which he said that he "could not stand by and watch innocent people injured and perhaps worse." He promised to send the Irish Army

Irish Army

The Irish Army, officially named simply the Army is the main branch of the Defence Forces of Ireland. Approximately 8,500 men and women serve in the Irish Army, divided into three infantry Brigades...

to the border and to set up field hospitals for those injured in the fighting. Lynch's words were widely interpreted in the Bogside as promising that Irish troops were about to be sent to their aid. Unionists were appalled at this prospect, which they saw as a threatened invasion of Northern Ireland. In fact, although the Irish Army was indeed sent to the border, they restricted their activities to providing medical care for the injured.

By 14 August, the rioting in the Bogside had reached a critical point. Almost the entire community there had been mobilised by this point, many galvanised by false rumours that St Eugene's Cathedral

St Eugene's Cathedral

St Eugene's Cathedral is the Roman Catholic cathedral located in Derry, Northern Ireland. It is the "Mother Church" for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Derry, as well as the parish Church of the parish of Templemore.-History:...

had been attacked by the police. The RUC were also beginning to use firearms. Two rioters were shot and injured in Great James' Street. The B-Specials

Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary was a reserve police force in Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the founding of Northern Ireland. It was an armed corps, organised partially on military lines and called out in times of emergency, such as war or insurgency...

, an auxiliary, mostly Protestant police force, much feared by Catholics for their role in killings in the 1920s, were called up and sent to Derry, provoking fears of a massacre on the part of the Bogsiders.

On the afternoon of the 14th, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland was the de facto head of the Government of Northern Ireland. No such office was provided for in the Government of Ireland Act 1920. However the Lord Lieutenant, as with Governors-General in other Westminster Systems such as in Canada, chose to appoint someone...

, James Chichester-Clark

James Chichester-Clark

James Dawson Chichester-Clark, Baron Moyola, PC, DL was the penultimate Prime Minister of Northern Ireland and eighth leader of the Ulster Unionist Party between 1969 and March 1971. He was Member of the Northern Ireland Parliament for South Londonderry for 12 years beginning at the by-election...

, took the unprecedented step of requesting the British Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Harold Wilson

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, FSS, PC was a British Labour Member of Parliament, Leader of the Labour Party. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s, winning four general elections, including a minority government after the...

for troops

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

to be sent to Derry. Soon afterwards a company of the Prince of Wales Own Regiment

Prince of Wales's Own Regiment of Yorkshire

The Prince of Wales's Own Regiment of Yorkshire was an infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the King's Division. It was created in 1958 by the amalgamation of The West Yorkshire Regiment and The East Yorkshire Regiment...

relieved the police, with orders to separate the RUC and the Bogsiders, but not to attempt to breach the barricades and enter the Bogside itself. This marked the first direct intervention of the London government in Ireland since partition

Partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland was the division of the island of Ireland into two distinct territories, now Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland . Partition occurred when the British Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1920...

. The British troops were at first welcomed by the Bogside residents as a neutral force compared to the RUC and especially the B-Specials.

Only a handful of radicals in Bogside, notably Bernadette Devlin, opposed the deployment of British troops. This good relationship did not last long however, as the Troubles escalated.

Over 1000 people had been injured in the rioting in Derry, but no one was killed. A total of 691 RUC men were deployed in Derry during the riot, of whom only 255 were still in action at 12.30 on the 15th. Manpower then fluctuated for the rest of the afternoon: the numbers recorded are 318, 304, 374, 333, 285 and finally 327 at 5.30 pm While some of the fluctuation in numbers can be put down to exhaustion rather than injury, these figures indicate that the RUC suffered at least 350 serious injuries. How many Bogsiders were injured is unclear, as many injuries were never reported.

Rioting elsewhere

A call by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights AssociationNorthern Ireland Civil Rights Association

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association was an organisation which campaigned for equal civil rights for the all the people in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s...

for people to stretch police resources to aid the Bogsiders led to rioting in Belfast

Belfast

Belfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

and elsewhere, which left five Catholics and two Protestants dead. That same night (the 14th) a loyalist mob burned all of the Catholic homes on Bombay Street. Over 1,500 Catholics were expelled from their homes in Belfast. Taken together with events in Derry, this period of rioting is widely seen as the point in which The Troubles

The Troubles

The Troubles was a period of ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland which spilled over at various times into England, the Republic of Ireland, and mainland Europe. The duration of the Troubles is conventionally dated from the late 1960s and considered by many to have ended with the Belfast...

escalated from a situation of civil unrest to one of a three-way armed conflict between nationalists, state forces and unionists.

Documentary

The documentary Battle of the Bogside, produced and directed by Vinny Cunningham and written by John Peto, won "Best Documentary" at the Irish Film and Television AwardsIrish Film and Television Awards

The Irish Film and Television Awards were first awarded in 2003. Its sole aim is to celebrate Ireland's notably talented film and television community...

in October 2004.

External links

- Boy with Petrol Bomb and Gas Mask (mural) Google street view

- Images from the booklet "Battle of Bogside" published in (1969).

- Wilson considered direct rule option as violence raged in North The Irish Times. 3 January 2000

- CAIN project chronology of events.