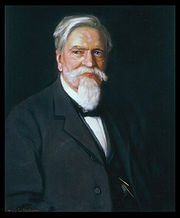

Simon Bolivar Buckner

Encyclopedia

Simon Bolivar Buckner fought in the United States Army

in the Mexican–American War

and in the Confederate States Army

during the American Civil War

. He later served as the 30th Governor of Kentucky

.

After graduating from the United States Military Academy

at West Point, Buckner became an instructor there. He took a hiatus from teaching to serve in the Mexican–American War, participating in many of the major battles of that conflict. He resigned from the army in 1855 to manage his father-in-law's real estate

in Chicago, Illinois. He returned to his native state in 1857 and was appointed adjutant general

by Governor Beriah Magoffin

in 1861. In this position, he tried to enforce Kentucky

's neutrality policy in the early days of the Civil War. When the state's neutrality was breached, Buckner accepted a commission in the Confederate Army after declining a similar commission to the Union Army

. In 1862, he accepted Ulysses S. Grant

's demand for an "unconditional surrender" at the Battle of Fort Donelson

. He was the first Confederate general to surrender an army in the war. He participated in Braxton Bragg

's failed invasion of Kentucky and near the end of the war became chief of staff to Edmund Kirby Smith

in the Trans-Mississippi

Department.

In the years following the war, Buckner became active in politics. He was elected governor of Kentucky in 1887. It was his second campaign for that office. His term was plagued by violent feuds in the eastern part of the state, including the Hatfield-McCoy feud

and the Rowan County War

. His administration was rocked by scandal when state treasurer James "Honest Dick" Tate absconded with $250,000 from the state's treasury. As governor, Buckner became known for veto

ing special interest legislation. In the 1888 legislative session alone, he utilized more vetoes than the previous ten governors combined. In 1895, he made an unsuccessful bid for a seat in the U.S. Senate

. The following year, he joined the National Democratic Party

, or "Gold Democrats", who favored a sound money policy over the Free Silver

position of the mainline Democrats. He was the Gold Democrats' candidate for Vice President of the United States

in the 1896 election, but polled just over one percent of the vote on a ticket with John M. Palmer

. He never again sought public office and died of uremic poisoning on January 8, 1914.

. He was the third child and second son of Aylett Hartswell and Elizabeth Ann (Morehead) Buckner. Named after the "South American soldier and statesman, Simón Bolívar

, then at the height of his power", the boy did not begin school until age nine, when he enrolled at a private school in Munfordville. His closest friend in Munfordville was Thomas J. Wood

, who would become a Union Army

general opposing Buckner at the Battle of Perryville

and the Battle of Chickamauga

during the Civil War. Buckner's father was an iron worker, but found that Hart County did not have sufficient timber to fire his iron furnace. Consequently, in 1838, he moved the family to southern Muhlenberg County

where he organized an iron-making corporation. Buckner attended school in Greenville

, and later at Christian County Seminary in Hopkinsville

.

On July 1, 1840, Buckner enrolled at the United States Military Academy

. In 1844 he graduated eleventh in his class of 25 and was commissioned a brevet

second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Infantry Regiment

. He was assigned to garrison duty at Sackett's Harbor

on Lake Ontario

until August 28, 1845, when he returned to the Academy to serve as an assistant professor of geography

, history

, and ethics

.

, enlisting with the 6th U.S. Infantry Regiment. His early duties included recruiting soldiers and bringing them to the Texas

border. In November 1846, he was ordered to join his company

in the field; he met them en route between Monclova

and Parras

. The company joined John E. Wool

at Saltillo

. In January 1847, Buckner was ordered to Vera Cruz

with William J. Worth

's division

. While Maj. Gen.

Winfield Scott

besieged Vera Cruz

, Buckner's unit engaged a few thousand Mexican cavalry at a nearby town called Amazoque.

On August 8, 1847, Buckner was appointed quartermaster

of the 6th Infantry. Shortly thereafter, he participated in battles at San Antonio

and Churubusco

, being slightly wounded in the latter battle. He was appointed a brevet first lieutenant for gallantry at Churubusco and Contreras

, but declined the honor in part because reports of his participation at Contreras were in error—he had been fighting in San Antonio at the time. Later, he was offered and accepted the same rank solely based on his conduct at Churubusco.

Buckner was again cited for gallant conduct at the Battle of Molino del Rey

, and was appointed a brevet captain. He participated in the Battle of Chapultepec

, the Battle of Belen Gate, and the storming of Mexico City

. At the conclusion of the war, American soldiers served as an army of occupation for a time, leaving soldiers time for leisure activities. Buckner joined the Aztec Club

, and in April 1848 was a part of the successful expedition of Popocatépetl

, a volcano southeast of Mexico City

. Buckner was afforded the honor of lowering the American flag over Mexico City for the last time during the occupation.

.

Buckner married Mary Jane Kingsbury on May 2, 1850, at her aunt's home in Old Lyme, Connecticut

. Shortly after their wedding, he was assigned to Fort Snelling

and later to Fort Atkinson on the Arkansas River

in present-day Kansas

. On December 31, 1851, he was promoted to first lieutenant, and on November 3, 1852, he was elevated to captain of the commissary department of the 6th U.S. Infantry in New York City

. Previously, he had attained only a brevet to these ranks. Buckner gained such a reputation for fair dealings with the Indians

, that the Oglala Lakota

tribe called him Young Chief, and their leader, Yellow Bear

, refused to treat

with anyone but Buckner.

Before leaving the Army, Buckner helped an old friend from West Point and the Mexican–American War, Captain Ulysses S. Grant

, by covering his expenses at a New York hotel until money arrived from Ohio to pay for his passage home. On March 26, 1855, Buckner resigned from the Army to work with his father-in-law, who had extensive real estate holdings in Chicago, Illinois. When his father-in-law died in 1856, Buckner inherited his property and moved to Chicago to manage it.

Still interested in military affairs, Buckner joined the Illinois State Militia of Cook County

as a major

. On April 3, 1857, he was appointed adjutant general

of Illinois

by Governor

William Henry Bissell

. He resigned the post in October of the same year. Following the Mountain Meadows massacre

, a regiment of Illinois volunteers organized for potential service in a campaign against the Mormons

. Buckner was offered command of the unit and a promotion to the rank of colonel

. He accepted the position, but predicted that the unit would not see action. His prediction proved correct, as negotiations between the federal government and Mormon leaders eased tensions between the two.

In late 1857, Buckner and his family returned to his native state and settled in Louisville

. Buckner's daughter, Lily, was born there on March 7, 1858. Later that year, a Louisville militia known as the Citizens' Guard was formed, and Buckner was made its captain. He served in this capacity until 1860, when the Guard was incorporated into the Kentucky State Guard's Second Regiment. He was appointed inspector general of Kentucky in 1860.

appointed Buckner adjutant general, promoted him to major general, and charged him with revising the state's militia laws. The state was torn between Union

and Confederacy

, with the legislature supporting the former and the governor the latter. This led the state to declare itself officially neutral

. Buckner assembled 61 companies

to defend Kentucky's neutrality.

The state board that controlled the militia considered it to be pro-secessionist

and ordered it to store its arms. On July 20, 1861, Buckner resigned from the state militia, declaring that he could no longer perform his duties due to the board's actions. That August he was twice offered a commission as a brigadier general

in the Union Army

—the first from general in chief Winfield Scott

, and the second from Secretary of War

Simon Cameron

following the personal order of President Abraham Lincoln

—but he declined. After Confederate Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk

occupied Columbus, Kentucky

, violating the state's neutrality, Buckner accepted a commission as a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army

on September 14, 1861, and was followed by many of the men he formerly commanded in the state militia. When his Confederate commission was approved, Union officials in Louisville indicted him for treason and seized his property. (Concerned that a similar action might be taken against his wife's property in Chicago, he had previously deeded it to his brother-in-law.) He became a division

commander in the Army of Central Kentucky under Brig. Gen. William J. Hardee

and was stationed in Bowling Green, Kentucky

.

on the Tennessee River

in February 1862, he turned his sights on nearby Fort Donelson

on the Cumberland

. Western Theater

commander Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston

sent Buckner to be one of four brigadier generals defending the fort. In overall command was the influential politician and military novice John B. Floyd

; Buckner's peers were Gideon J. Pillow and Bushrod Johnson

.

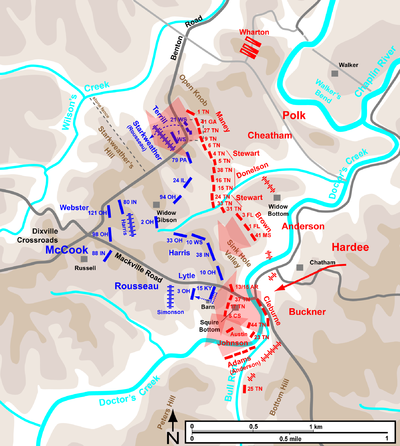

Buckner's division defended the right flank of the Confederate line of entrenchments that surrounded the fort and the small town of Dover, Tennessee

. On February 14, the Confederate generals decided they could not hold the fort and planned a breakout, hoping to join with Johnston's army, now in Nashville

. At dawn the following morning, Pillow launched a strong assault against the right flank of Grant's army, pushing it back 1 mile. Buckner, not confident of his army's chances and not on good terms with Pillow, held back his supporting attack for over two hours, which gave Grant's men time to bring up reinforcements and reform their line. Buckner's delay did not prevent the Confederate attack from opening a corridor for an escape from the besieged fort. However, Floyd and Pillow combined to undo the day's work by ordering the troops back to their trench positions.

Late that night the generals held a council of war

in which Floyd and Pillow expressed satisfaction with the events of the day, but Buckner convinced them that they had little realistic chance to hold the fort or escape from Grant's army, which was receiving steady reinforcements. His defeatism carried the meeting. General Floyd, concerned he would be tried for treason

if captured by the North, sought Buckner's assurance that he would be given time to escape with some of his Virginia regiments before the army surrendered. Buckner agreed and Floyd offered to turn over command to his subordinate, Pillow. Pillow immediately declined and passed command to Buckner, who agreed to stay behind and surrender. Pillow and Floyd were able to escape, as did cavalry commander Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest

.

That morning, Buckner sent a messenger to the Union Army requesting an armistice and a meeting of commissioners to work out surrender terms. He may have been hoping Grant would offer generous terms, remembering the assistance he gave Grant when he was destitute, but Grant had no sympathy for his old friend and his reply included the famous quotation, "No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works." To this, Buckner responded:

Grant was courteous to Buckner following the surrender and offered to loan him money to see him through his impending imprisonment, but Buckner declined. The surrender was a humiliation for Buckner personally, but also a strategic defeat for the Confederacy, which lost more than 12,000 men and much equipment, as well as control of the Cumberland River, which led to the evacuation of Nashville.

at Fort Warren

in Boston

, Kentucky Senator Garrett Davis

unsuccessfully sought to have him tried for treason. On August 15, 1862, after five months of writing poetry in solitary confinement, Buckner was exchanged for Union Brig. Gen. George A. McCall

. The following day he was promoted to major general and ordered to Chattanooga, Tennessee

, to join Gen. Braxton Bragg

's Army of Mississippi

.

Days after Buckner joined Bragg, both Bragg and Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith

began an invasion of Kentucky. As Bragg pushed north, his first encounter was in Buckner's home town of Munfordville

. The small town was important for Union forces to maintain communication with Louisville if they decided to press southward to Bowling Green and Nashville. A small force under the command of Col. John T. Wilder

guarded the town. Though vastly outnumbered, Wilder refused requests to surrender on September 12 and September 14. By September 17, however, Wilder recognized his difficult position and asked Bragg for proof of the superior numbers he claimed. In an unusual move, Wilder agreed to be blindfolded and brought to Buckner. When he arrived, he told Buckner that he (Wilder) was not a military man and had come to ask him what he should do. Flattered, Buckner showed Wilder the strength and position of the Confederate forces, which outnumbered Wilder's men almost 5-to-1. Seeing the hopeless situation he was in, Wilder informed Buckner that he wanted to surrender. Any other course, he later explained, would be "no less than willful murder."

Bragg's men continued northward to Bardstown

where they rested and sought supplies and recruits. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell

's Army of the Ohio

, the main Union force in the state, was pressing toward Louisville. Bragg left his army and met Kirby Smith in Frankfort, where he was able to attend the inauguration

of Confederate Governor Richard Hawes

on October 4. Buckner, although protesting this distraction from the military mission, attended as well and gave stirring speeches to the local crowds about the Confederacy's commitment to the state of Kentucky. The inauguration ceremony was disrupted by the sound of cannon fire from an approaching Union division and the inaugural ball scheduled for that evening was canceled.

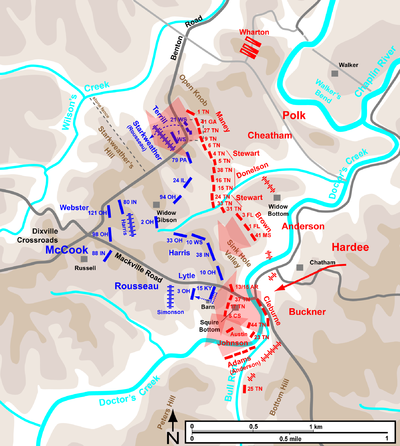

Based on intelligence acquired by a spy in Buell's army, Buckner advised Bragg that Buell was still ten miles from Louisville in the town of Mackville

Based on intelligence acquired by a spy in Buell's army, Buckner advised Bragg that Buell was still ten miles from Louisville in the town of Mackville

. He urged Bragg to engage Buell there before he reached Louisville, but Bragg declined. Buckner then asked Leonidas Polk to request that Bragg concentrate his forces and attack the Union army at Perryville

, but again, Bragg refused. Finally, on October 8, 1862, Bragg's army—not yet concentrated with Kirby Smith's—engaged Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook's

corps of Buell's army and began the Battle of Perryville

. Buckner's division fought under General Hardee during this battle, achieving a significant breakthrough in the Confederate center, and reports from Hardee, Polk, and Bragg all praised Buckner's efforts. His gallantry was for naught, however, as Perryville ended in a tactical draw that was costly for both sides, causing Bragg to withdraw and abandon his invasion of Kentucky. Buckner joined many of his fellow generals in publicly denouncing Bragg's performance during the campaign.

. He remained there until late April 1863, when he was ordered to take command of the Army of East Tennessee. He arrived in Knoxville

on May 11, 1863, and assumed command the following day. Shortly thereafter, his department was converted into a district of the Department of Tennessee under Gen. Bragg and was designated the Third Corps of the Army of Tennessee.

In late August, Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

approached Buckner's position at Knoxville. Buckner called for reinforcements from Bragg at Chattanooga

, but Bragg was being threatened by forces under Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans

and could not spare any of his men. Bragg ordered Buckner to fall back to the Hiwassee River

. From there, Buckner's unit traveled to Bragg's supply base at Ringgold, Georgia

, then on to Lafayette

and Chickamauga

. Bragg was also forced from Chattanooga and joined Buckner at Chickamauga. On September 19 and 20, the Confederate forces attacked and emerged victorious at the Battle of Chickamauga

. Buckner's Corps fought on the Confederate left both days, the second under the "wing" command of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet

, participating in the great breakthrough of the Union line.

After Chickamauga, Rosecrans and his Army of the Cumberland

retreated to fortified Chattanooga. Bragg held an ineffective siege against Chattanooga, but refused to take any further action as the Union forces there were reinforced by Ulysses S. Grant and reopened a tenuous supply line. Many of Bragg's subordinates, including Buckner, advocated that Bragg be relieved of command. Thomas L. Connelly, historian of the Army of Tennessee, believes that Buckner was the author of the anti-Bragg letter sent by the generals to President Jefferson Davis

. Bragg retaliated by reducing Buckner to division command and abolishing the Department of East Tennessee.

Buckner was given a medical leave of absence following Chickamauga, returning to Virginia, where he engaged in routine work while recovering his strength. His division was sent without him to support Longstreet in the Knoxville Campaign

, while the remainder of Bragg's army was defeated in the Chattanooga Campaign

. Buckner served on the court martial of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws

after that subordinate of Longstreet's was charged with poor performance at Knoxville. Buckner was briefly given command of Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood

's division in February 1864, and on March 8, he was given command of the reestablished Department of East Tennessee. The department was a shell of its former self—less than one-third its original size, badly equipped, and in no position to mount an offensive. Buckner was virtually useless to the Confederacy here, and on April 28, he was ordered to join Edmund Kirby Smith in the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederacy.

Buckner had difficulty traveling to the West, and it was early summer before he arrived. He assumed command of the District of West Louisiana on August 4. Shortly after Buckner arrived at Smith's headquarters in Shreveport

, Louisiana

, Smith began requesting a promotion for him. The promotion to lieutenant general came on September 20. Smith placed Buckner in charge of the critical but difficult task of selling the department's cotton through enemy lines.

As news of Gen. Robert E. Lee

's surrender on April 9, 1865, reached the department, soldiers deserted the Confederacy in droves. On April 19, Smith consolidated the District of Arkansas with the District of West Louisiana; the combined district was put under Buckner's command. On May 9, Smith made Buckner his chief of staff. Rumors began to swirl in both Union and Confederate camps that Smith and Buckner would not surrender, but would fall back to Mexico with soldiers who remained loyal to the Confederacy. Though Smith did cross the Rio Grande

, he learned on his arrival that Buckner had traveled to New Orleans

on May 26 and arranged terms of surrender. Smith had instead instructed Buckner to move all the troops to Houston

, Texas.

At Fort Donelson, Tennessee, Buckner had become the first Confederate general of the war to surrender an army; at New Orleans, he became one of the last. The surrender became official when Smith endorsed it on June 2, (Only Brigadier General Stand Watie

held out longer, he surrendered the last Confederate land forces on June 23, 1865).

Conditions set forth in Buckner's surrender were the following:

(1) "All acts of hostility on the part of both armies are to cease from this date."

(2) The officers and men are to be "paroled until duly exchanged."

(3) All Confederate property was to be turned over to the Union.

(4) All officers and men could return home.

(5) "The surrender of property will not include the side arms or private horses or baggage of officers" and enlsited men.

(6) "All 'self-disposed persons' who return to 'peaceful pursuits' are assured that may resume their usual avocations . . . "."

and yellow fever

.

Buckner returned to Kentucky when he was eligible in 1868 and became editor of the Louisville Courier. Like most former Confederate officers, he petitioned the United States Congress

for the restoration of his civil rights

as stipulated by the 14th Amendment

. He recovered most of his property through lawsuits and regained much of his wealth through shrewd business deals.

On January 5, 1874, after five years of suffering with tuberculosis

, Buckner's wife died. Now a widower, Buckner continued to live in Louisville until 1877 when he and his daughter Lily returned to the family estate in Munfordville. His sister, a recent widow, also returned to the estate in 1877. For six years, these three inhabited and repaired the house and grounds of Glen Lily, which had been neglected during the war and its aftermath. On June 14, 1883, Lily Buckner married Morris B. Belknap of Louisville, and the couple made their residence in Louisville. On October 10 of the same year, Buckner's sister died, and he was left alone.

that nominated Horatio Seymour

for president. Though Buckner had favored George H. Pendleton

, he loyally supported the party's nominee throughout the campaign.

In 1883, Buckner was a candidate for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination. Other prominent candidates included Congressman

Thomas Laurens Jones

, former congressman J. Proctor Knott

, and Louisville mayor Charles Donald Jacob

. Buckner consistently ran third in the first six ballots, but withdrew his name from consideration before the seventh ballot. The delegation from Owsley County

switched their support to Knott, starting a wave of defections that resulted in Jones' withdrawal and Knott's unanimous nomination. Knott went on to win the general election and appointed Buckner to the board of trustees for the Kentucky Agricultural and Mechanical College (later the University of Kentucky

) in 1884. At that year's state Democratic convention, he served on the committee on credentials.

On June 10, 1885, Buckner married Delia Claiborne of Richmond, Kentucky

. Buckner was 62; Claiborne was 28. Their son, Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr.

, was born on July 18, 1886.

Delegates to the 1887 state Democratic convention nominated Buckner unanimously for the office of governor. A week later, the Republican

Delegates to the 1887 state Democratic convention nominated Buckner unanimously for the office of governor. A week later, the Republican

s chose William O. Bradley as their candidate. The Prohibition Party

and the Union Labor Party also nominated candidates for governor. The official results of the election gave Buckner at plurality of 16,797 over Bradley.

Buckner proposed a number of progressive

ideas, most of which were rejected by the legislature. Among his successful proposals were the creation of a state board of tax equalization, creation of a parole system for convicts, and codification of school laws. His failed proposals included creation of a department of justice, greater local support for education and better protection for forests.

Much of Buckner's time was spent trying to curb violence in the eastern part of the state. Shortly after his inauguration, the Rowan County War

escalated to vigilantism, when residents of the county organized a posse and killed several of the leaders of the feud. Though this essentially ended the feud, the violence had been so bad that Buckner's adjutant general recommended that the Kentucky General Assembly

dissolve Rowan County, though this suggestion was not acted upon. In 1888, a posse from Kentucky entered West Virginia

and killed a leader of the Hatfield clan in the Hatfield-McCoy feud

. This caused a political conflict between Buckner and Governor Emanuel Willis Wilson

of West Virginia

, who complained that the raid was illegal. The matter was adjudicated in federal court, and Buckner was cleared of any connection to the raid. Later in Buckner's term, feuds broke out in Harlan

, Letcher

, Perry

, Knott

, and Breathitt

counties.

A major financial scandal erupted in 1888 when Buckner ordered a routine audit of the state's finances which had been neglected for years. The audit showed that the state's longtime treasurer, James "Honest Dick" Tate, had been mismanaging and embezzling

the state's money since 1872. Faced with the prospect that his malfeasance would be discovered, Tate absconded with nearly $250,000 of state funds. He was never found. The General Assembly immediately began impeachment

hearings against Tate, convicted him in absentia

, and removed him from office. State auditor Fayette Hewitt was censure

d for neglecting the duty of his office, but was not implicated in Tate's theft or disappearance.

During the 1888 session, the General Assembly passed 1,571 bills, exceeding the total passed by any other session in the state's history. Only about 150 of these bills were of a general nature; the rest were special interest bills passed for the private gain of legislators and those in their constituencies. Buckner veto

ed 60 of these special interest bills, more than had been vetoed by the previous ten governors combined. Only one of these vetoes was overridden by the legislature. Ignoring Buckner's clear intent to veto special interest bills, the 1890 legislature passed 300 more special interest bills than had its predecessor. Buckner vetoed 50 of these. His reputation for rejecting special interest bills led the Kelley Axe Factory, the largest axe factory in the country at the time, to present him with a ceremonial "Veto Hatchet".

When a tax cut passed over Buckner's veto in 1890 drained the state treasury, the governor loaned the state enough money to remain solvent until tax revenue came in. Later that year, he was chosen as a delegate to the state's constitutional convention. In this capacity, he unsuccessfully sought to extend the governor's appointment powers and levy taxes on churches, clubs, and schools that made a profit.

; outgoing governor John Y. Brown; and congressman James B. McCreary

. The Democratic party split over the issue of bimetalism. Buckner advocated for a gold standard, but the majority of Kentuckians advocated "Free Silver

". Seeing that he would not be able to win the seat in light of this opposition, he withdrew from the race in July 1895. In spite of his withdrawal, he still received 9 of the 134 votes cast in the General Assembly.

At the 1896 Democratic National Convention

in Chicago, the Democrats nominated William Jennings Bryan

for president

and adopted a platform calling for the free coinage of silver. Sound money Democrats opposed Bryan and the free silver platform. They formed a new party—the National Democratic Party

, or Gold Democrats—which Buckner joined. At the new party's state convention in Louisville, Buckner's name was proposed as a candidate for vice president

. He was given the nomination without opposition at the party's national convention in Indianapolis

. Former Union general John Palmer

was chosen as the party's nominee for president.

Palmer and Buckner both had developed reputations as independent executives while serving as governors of their respective states. Because they had served on opposite sides during the Civil War, their presence on the same ticket emphasized national unity. The ticket was endorsed by several major newspapers including the Chicago Chronicle, Louisville Courier-Journal, Detroit Free Press

, Richmond Times, and New Orleans Picayune. Despite these advantages, the ticket was hurt by the candidates' ages, Palmer being 79 and Buckner 73. Further, some supporters feared that voting for the National Democrat ticket would be a wasted vote and might even throw the election to Bryan. Ultimately, Palmer and Buckner received just over one percent of the vote in the election.

Following this defeat, Buckner retired to Glen Lily but remained active in politics. Though he always claimed membership in the Democratic party, he opposed the machine politics

of William Goebel

, his party's gubernatorial nominee in 1899. In 1903, he supported his son-in-law, Morris Belknap, for governor against Goebel's lieutenant governor

, J. C. W. Beckham

. When the Democrats again nominated William Jennings Bryan in the 1908 presidential election

, Buckner openly supported Bryan's opponent, Republican William Howard Taft

.

At 80 years of age, Buckner memorized five of Shakespeare

's plays because cataract

s threatened to blind him, but an operation saved his sight. On a visit to the White House

in 1904, Buckner asked President Theodore Roosevelt

to appoint his only son

as a cadet at West Point, and Roosevelt quickly agreed. His son would later serve in the U.S. Army and be killed at the Battle of Okinawa

, making him the highest-ranking American to have been killed by enemy fire during World War II

.

Following the deaths of Stephen D. Lee

and Alexander P. Stewart

in 1908, Buckner became the last surviving Confederate soldier with the rank of lieutenant general. The following year, he visited his son, who was stationed in Texas, and toured old Mexican–American War battlefields where he had served. In 1912, his health began to fail. He died on January 8, 1914, after a week-long bout with uremic poisoning

. He was buried in Frankfort Cemetery

in Frankfort, Kentucky

.

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

in the Mexican–American War

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known as the First American Intervention, the Mexican War, or the U.S.–Mexican War, was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848 in the wake of the 1845 U.S...

and in the Confederate States Army

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. He later served as the 30th Governor of Kentucky

Governor of Kentucky

The Governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of the executive branch of government in the U.S. state of Kentucky. Fifty-six men and one woman have served as Governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-election once...

.

After graduating from the United States Military Academy

United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy at West Point is a four-year coeducational federal service academy located at West Point, New York. The academy sits on scenic high ground overlooking the Hudson River, north of New York City...

at West Point, Buckner became an instructor there. He took a hiatus from teaching to serve in the Mexican–American War, participating in many of the major battles of that conflict. He resigned from the army in 1855 to manage his father-in-law's real estate

Real estate

In general use, esp. North American, 'real estate' is taken to mean "Property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals, or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this; an item of real property; buildings or...

in Chicago, Illinois. He returned to his native state in 1857 and was appointed adjutant general

Adjutant general

An Adjutant General is a military chief administrative officer.-Imperial Russia:In Imperial Russia, the General-Adjutant was a Court officer, who was usually an army general. He served as a personal aide to the Tsar and hence was a member of the H. I. M. Retinue...

by Governor Beriah Magoffin

Beriah Magoffin

Beriah Magoffin was the 21st Governor of Kentucky, serving during the early part of the Civil War. Personally, Magoffin adhered to a states' rights position, including the right of a state to secede from the Union, and he sympathized with the Confederate cause...

in 1861. In this position, he tried to enforce Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

's neutrality policy in the early days of the Civil War. When the state's neutrality was breached, Buckner accepted a commission in the Confederate Army after declining a similar commission to the Union Army

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

. In 1862, he accepted Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

's demand for an "unconditional surrender" at the Battle of Fort Donelson

Battle of Fort Donelson

The Battle of Fort Donelson was fought from February 11 to February 16, 1862, in the Western Theater of the American Civil War. The capture of the fort by Union forces opened the Cumberland River as an avenue for the invasion of the South. The success elevated Brig. Gen. Ulysses S...

. He was the first Confederate general to surrender an army in the war. He participated in Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg was a career United States Army officer, and then a general in the Confederate States Army—a principal commander in the Western Theater of the American Civil War and later the military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.Bragg, a native of North Carolina, was...

's failed invasion of Kentucky and near the end of the war became chief of staff to Edmund Kirby Smith

Edmund Kirby Smith

Edmund Kirby Smith was a career United States Army officer and educator. He served as a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, notable for his command of the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederacy after the fall of Vicksburg.After the conflict ended Smith...

in the Trans-Mississippi

Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War

The Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War was the major military and naval operations west of the Mississippi River. The area excluded the states and territories bordering the Pacific Ocean, which formed the Pacific Coast Theater of the American Civil War.The campaign classification...

Department.

In the years following the war, Buckner became active in politics. He was elected governor of Kentucky in 1887. It was his second campaign for that office. His term was plagued by violent feuds in the eastern part of the state, including the Hatfield-McCoy feud

Hatfield-McCoy feud

The Hatfield–McCoy feud involved two families of the West Virginia–Kentucky back country along the Tug Fork, off the Big Sandy River. The Hatfields of West Virginia were led by William Anderson "Devil Anse" Hatfield while the McCoys of Kentucky under the leadership of Randolph "Ole Ran'l" McCoy....

and the Rowan County War

Rowan County War

The Rowan County War, located in Rowan County, Kentucky, centered in Morehead, Kentucky, was a feud that took place between 1884 and 1887. In total, 20 people died and 16 were wounded.-Background:...

. His administration was rocked by scandal when state treasurer James "Honest Dick" Tate absconded with $250,000 from the state's treasury. As governor, Buckner became known for veto

Veto

A veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

ing special interest legislation. In the 1888 legislative session alone, he utilized more vetoes than the previous ten governors combined. In 1895, he made an unsuccessful bid for a seat in the U.S. Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

. The following year, he joined the National Democratic Party

National Democratic Party (United States)

The National Democratic Party or Gold Democrats was a short-lived political party of Bourbon Democrats, who opposed the regular party nominee William Jennings Bryan in 1896. Most members were admirers of Grover Cleveland. They considered Bryan a dangerous man and charged that his "free silver"...

, or "Gold Democrats", who favored a sound money policy over the Free Silver

Free Silver

Free Silver was an important United States political policy issue in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Its advocates were in favor of an inflationary monetary policy using the "free coinage of silver" as opposed to the less inflationary Gold Standard; its supporters were called...

position of the mainline Democrats. He was the Gold Democrats' candidate for Vice President of the United States

Vice President of the United States

The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term...

in the 1896 election, but polled just over one percent of the vote on a ticket with John M. Palmer

John M. Palmer (politician)

John McAuley Palmer , was an Illinois resident, an American Civil War General who fought for the Union, the 15th Governor of Illinois, and presidential candidate of the National Democratic Party in the 1896 election on a platform to defend the gold standard, free trade, and limited...

. He never again sought public office and died of uremic poisoning on January 8, 1914.

Early life

Simon B. Buckner, Sr., was born at Glen Lily, his family's estate near Munfordville, KentuckyMunfordville, Kentucky

Munfordville is a city in and the county seat of Hart County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 1,563 at the 2000 census.-History:The city was once known as Big Buffalo Crossing. The current name came from Richard Jones Munford, who donated the land for development in 1816...

. He was the third child and second son of Aylett Hartswell and Elizabeth Ann (Morehead) Buckner. Named after the "South American soldier and statesman, Simón Bolívar

Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios Ponte y Yeiter, commonly known as Simón Bolívar was a Venezuelan military and political leader...

, then at the height of his power", the boy did not begin school until age nine, when he enrolled at a private school in Munfordville. His closest friend in Munfordville was Thomas J. Wood

Thomas J. Wood

Thomas John Wood was a career United States Army officer and a Union general during the American Civil War.-Early life and career:...

, who would become a Union Army

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

general opposing Buckner at the Battle of Perryville

Battle of Perryville

The Battle of Perryville, also known as the Battle of Chaplin Hills, was fought on October 8, 1862, in the Chaplin Hills west of Perryville, Kentucky, as the culmination of the Confederate Heartland Offensive during the American Civil War. Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg's Army of Mississippi won a...

and the Battle of Chickamauga

Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought September 19–20, 1863, marked the end of a Union offensive in southeastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia called the Chickamauga Campaign...

during the Civil War. Buckner's father was an iron worker, but found that Hart County did not have sufficient timber to fire his iron furnace. Consequently, in 1838, he moved the family to southern Muhlenberg County

Muhlenberg County, Kentucky

Muhlenberg County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2010 Census, the population was 31,499. The county is named for Peter Muhlenberg. Its county seat is Greenville....

where he organized an iron-making corporation. Buckner attended school in Greenville

Greenville, Kentucky

Greenville is a city in and the county seat of Muhlenberg County, Kentucky, United States. It is named for Revolutionary War General Nathan Greene...

, and later at Christian County Seminary in Hopkinsville

Hopkinsville, Kentucky

Hopkinsville is a city in Christian County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 31,577 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Christian County.- History :...

.

On July 1, 1840, Buckner enrolled at the United States Military Academy

United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy at West Point is a four-year coeducational federal service academy located at West Point, New York. The academy sits on scenic high ground overlooking the Hudson River, north of New York City...

. In 1844 he graduated eleventh in his class of 25 and was commissioned a brevet

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Infantry Regiment

2nd Infantry Regiment (United States)

The 2nd Infantry Regiment is an infantry regiment in the United States Army. It has served the United States for more than two hundred years. It is the third oldest regiment in the US Army with a Lineage date of 1808 and a history extending back to 1791...

. He was assigned to garrison duty at Sackett's Harbor

Sackets Harbor, New York

Sackets Harbor is a village in Jefferson County, New York, United States. The population was 1,386 at the 2000 census. The village was named after land developer and owner Augustus Sackett, who founded it in the early 19th century.The Village of Sackets Harbor is within the western part of the...

on Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south by the American state of New York. Ontario, Canada's most populous province, was named for the lake. In the Wyandot language, ontarío means...

until August 28, 1845, when he returned to the Academy to serve as an assistant professor of geography

Geography

Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes...

, history

History

History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

, and ethics

Ethics

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, is a branch of philosophy that addresses questions about morality—that is, concepts such as good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, justice and crime, etc.Major branches of ethics include:...

.

Service in the Mexican–American War

In May 1846, Buckner resigned his teaching position to fight in the Mexican–American WarMexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known as the First American Intervention, the Mexican War, or the U.S.–Mexican War, was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848 in the wake of the 1845 U.S...

, enlisting with the 6th U.S. Infantry Regiment. His early duties included recruiting soldiers and bringing them to the Texas

Texas

Texas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

border. In November 1846, he was ordered to join his company

Company (military unit)

A company is a military unit, typically consisting of 80–225 soldiers and usually commanded by a Captain, Major or Commandant. Most companies are formed of three to five platoons although the exact number may vary by country, unit type, and structure...

in the field; he met them en route between Monclova

Monclova

On the other hand, temperatures during late spring and summer can have bouts of extreme heat, with evenings above 40°C for many consecutive days. In recent decades the hottest records have climbed as high as 43°C on July 13, 2005 and 45°C on May 4, 1984. However nighttime low temperatures are...

and Parras

Parras (municipality)

Parras is a one of the 38 municipalities of Coahuila, in north-eastern Mexico. The municipal seat lies at Parras de la Fuente. The municipality covers an area of 9,271.7 km².As of 2005, the municipality had a total population of 44,715....

. The company joined John E. Wool

John E. Wool

John Ellis Wool was an officer in the United States Army during three consecutive U.S. wars: the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War and the American Civil War. By the time of the Mexican-American War, he was widely considered one of the most capable officers in the army and a superb organizer...

at Saltillo

Saltillo

Saltillo is the capital city of the northeastern Mexican state of Coahuila and the municipal seat of the municipality of the same name. The city is located about 400 km south of the U.S. state of Texas, and 90 km west of Monterrey, Nuevo León....

. In January 1847, Buckner was ordered to Vera Cruz

Veracruz, Veracruz

Veracruz, officially known as Heroica Veracruz, is a major port city and municipality on the Gulf of Mexico in the Mexican state of Veracruz. The city is located in the central part of the state. It is located along Federal Highway 140 from the state capital Xalapa, and is the state's most...

with William J. Worth

William J. Worth

William Jenkins Worth was a United States general during the Mexican-American War.-Early life:Worth was born in 1794 in Hudson, New York, to Thomas Worth and Abigail Jenkins. Both of his parents were Quakers, but he rejected the pacifism of their faith...

's division

Division (military)

A division is a large military unit or formation usually consisting of between 10,000 and 20,000 soldiers. In most armies, a division is composed of several regiments or brigades, and in turn several divisions typically make up a corps...

. While Maj. Gen.

Major general (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Marine Corps, and United States Air Force, major general is a two-star general-officer rank, with the pay grade of O-8. Major general ranks above brigadier general and below lieutenant general...

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852....

besieged Vera Cruz

Siege of Veracruz

The Battle of Veracruz was a 20-day siege of the key Mexican beachhead seaport of Veracruz, during the Mexican-American War. Lasting from 9-29 March 1847, it began with the first large-scale amphibious assault conducted by United States military forces, and ended with the surrender and occupation...

, Buckner's unit engaged a few thousand Mexican cavalry at a nearby town called Amazoque.

On August 8, 1847, Buckner was appointed quartermaster

Quartermaster

Quartermaster refers to two different military occupations depending on if the assigned unit is land based or naval.In land armies, especially US units, it is a term referring to either an individual soldier or a unit who specializes in distributing supplies and provisions to troops. The senior...

of the 6th Infantry. Shortly thereafter, he participated in battles at San Antonio

San Antonio, Texas

San Antonio is the seventh-largest city in the United States of America and the second-largest city within the state of Texas, with a population of 1.33 million. Located in the American Southwest and the south–central part of Texas, the city serves as the seat of Bexar County. In 2011,...

and Churubusco

Battle of Churubusco

The Battle of Churubusco took place on August 20, 1847, in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Contreras during the Mexican-American War. After defeating the Mexican army at Churubusco, the U.S. Army was only 5 miles away from Mexico City, the capital of the nation...

, being slightly wounded in the latter battle. He was appointed a brevet first lieutenant for gallantry at Churubusco and Contreras

Battle of Contreras

The Battle of Contreras, also known as the Battle of Padierna, took place during August 19–20, 1847, in the final encounters of the Mexican-American War. In the Battle of Churubusco, fighting continued the following day.-Background:...

, but declined the honor in part because reports of his participation at Contreras were in error—he had been fighting in San Antonio at the time. Later, he was offered and accepted the same rank solely based on his conduct at Churubusco.

Buckner was again cited for gallant conduct at the Battle of Molino del Rey

Battle of Molino del Rey

The Battle of Molino del Rey was one of the bloodiest engagements of the Mexican-American War. It was fought in September 1847 between Mexican forces under General Antonio Léon against an American force under General Winfield Scott at a hill called El Molino del Rey near Mexico City.-Background:On...

, and was appointed a brevet captain. He participated in the Battle of Chapultepec

Battle of Chapultepec

The Battle of Chapultepec, in September 1847, was a United States victory over Mexican forces holding Chapultepec Castle west of Mexico City during the Mexican-American War.-Background:On September 13, 1847, in the costly Battle of Molino del Rey, U.S...

, the Battle of Belen Gate, and the storming of Mexico City

Battle for Mexico City

The Battle for Mexico City refers to the series of engagements from September 8 to September 15, 1847, in the general vicinity of Mexico City during the Mexican-American War...

. At the conclusion of the war, American soldiers served as an army of occupation for a time, leaving soldiers time for leisure activities. Buckner joined the Aztec Club

Aztec Club of 1847

The Aztec Club of 1847 is an historic society founded in 1847 by United States Army officers of the Mexican–American War. It exists as a hereditary organization including members who can trace a direct lineal connection to those originally eligible....

, and in April 1848 was a part of the successful expedition of Popocatépetl

Popocatépetl

Popocatépetl also known as "Popochowa" by the local population is an active volcano and, at , the second highest peak in Mexico after the Pico de Orizaba...

, a volcano southeast of Mexico City

Mexico City

Mexico City is the Federal District , capital of Mexico and seat of the federal powers of the Mexican Union. It is a federal entity within Mexico which is not part of any one of the 31 Mexican states but belongs to the federation as a whole...

. Buckner was afforded the honor of lowering the American flag over Mexico City for the last time during the occupation.

Interbellum

After the war, Buckner accepted an invitation to return to West Point to teach infantry tactics. Just over a year later, he resigned the post in protest over the academy's compulsory chapel attendance policy. Following his resignation, he was assigned to a recruiting post at Fort ColumbusFort Columbus

Fort Columbus was a fortification and army post in Governors Island, New York Harbor, New York City, New York, from 1806 to 1904.-Fort Jay:Fort Columbus was the name of a fortification and later the army post that developed around it...

.

Buckner married Mary Jane Kingsbury on May 2, 1850, at her aunt's home in Old Lyme, Connecticut

Old Lyme, Connecticut

Old Lyme is a town in New London County, Connecticut, United States. The Main Street of the town is a historic district. The town has long been a popular summer resort and artists' colony...

. Shortly after their wedding, he was assigned to Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling, Minnesota

Fort Snelling, originally known as Fort Saint Anthony, was a military fortification located at the confluence of the Minnesota River and Mississippi River in Hennepin County, Minnesota...

and later to Fort Atkinson on the Arkansas River

Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. The Arkansas generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's initial basin starts in the Western United States in Colorado, specifically the Arkansas...

in present-day Kansas

Kansas

Kansas is a US state located in the Midwestern United States. It is named after the Kansas River which flows through it, which in turn was named after the Kansa Native American tribe, which inhabited the area. The tribe's name is often said to mean "people of the wind" or "people of the south...

. On December 31, 1851, he was promoted to first lieutenant, and on November 3, 1852, he was elevated to captain of the commissary department of the 6th U.S. Infantry in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

. Previously, he had attained only a brevet to these ranks. Buckner gained such a reputation for fair dealings with the Indians

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

, that the Oglala Lakota

Oglala Lakota

The Oglala Lakota or Oglala Sioux are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people; along with the Nakota and Dakota, they make up the Great Sioux Nation. A majority of the Oglala live on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, the eighth-largest Native American reservation in the...

tribe called him Young Chief, and their leader, Yellow Bear

Yellow Bear

-The First Yellow Bear:The first Yellow Bear was a prominent headman among the Tapisleca Tiyospaye , one of the major divisions of the southern Oglala Lakota. He accompanied the first Oglala delegation to Washington, D.C. in 1870. By the following year, Colonel John E...

, refused to treat

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

with anyone but Buckner.

Before leaving the Army, Buckner helped an old friend from West Point and the Mexican–American War, Captain Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

, by covering his expenses at a New York hotel until money arrived from Ohio to pay for his passage home. On March 26, 1855, Buckner resigned from the Army to work with his father-in-law, who had extensive real estate holdings in Chicago, Illinois. When his father-in-law died in 1856, Buckner inherited his property and moved to Chicago to manage it.

Still interested in military affairs, Buckner joined the Illinois State Militia of Cook County

Cook County, Illinois

Cook County is a county in the U.S. state of Illinois, with its county seat in Chicago. It is the second most populous county in the United States after Los Angeles County. The county has 5,194,675 residents, which is 40.5 percent of all Illinois residents. Cook County's population is larger than...

as a major

Major (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, major is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel...

. On April 3, 1857, he was appointed adjutant general

Adjutant general

An Adjutant General is a military chief administrative officer.-Imperial Russia:In Imperial Russia, the General-Adjutant was a Court officer, who was usually an army general. He served as a personal aide to the Tsar and hence was a member of the H. I. M. Retinue...

of Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

by Governor

Governor of Illinois

The Governor of Illinois is the chief executive of the State of Illinois and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by popular suffrage of residents of the state....

William Henry Bissell

William Henry Bissell

William Henry Bissell was the 11th Governor of the U.S. state of Illinois from 1857 until his death. He was one of the first successful Republican Party candidates, winning the election of 1856 just two years after the founding of his party.Bissell was born in Hartwick, Otsego County, New York...

. He resigned the post in October of the same year. Following the Mountain Meadows massacre

Mountain Meadows massacre

The Mountain Meadows massacre was a series of attacks on the Baker–Fancher emigrant wagon train, at Mountain Meadows in southern Utah. The attacks culminated on September 11, 1857 in the mass slaughter of the emigrant party by the Iron County district of the Utah Territorial Militia and some local...

, a regiment of Illinois volunteers organized for potential service in a campaign against the Mormons

Mormonism

Mormonism is the religion practiced by Mormons, and is the predominant religious tradition of the Latter Day Saint movement. This movement was founded by Joseph Smith, Jr. beginning in the 1820s as a form of Christian primitivism. During the 1830s and 1840s, Mormonism gradually distinguished itself...

. Buckner was offered command of the unit and a promotion to the rank of colonel

Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, colonel is a senior field grade military officer rank just above the rank of lieutenant colonel and just below the rank of brigadier general...

. He accepted the position, but predicted that the unit would not see action. His prediction proved correct, as negotiations between the federal government and Mormon leaders eased tensions between the two.

In late 1857, Buckner and his family returned to his native state and settled in Louisville

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

. Buckner's daughter, Lily, was born there on March 7, 1858. Later that year, a Louisville militia known as the Citizens' Guard was formed, and Buckner was made its captain. He served in this capacity until 1860, when the Guard was incorporated into the Kentucky State Guard's Second Regiment. He was appointed inspector general of Kentucky in 1860.

Civil War

In 1861 Kentucky governor Beriah MagoffinBeriah Magoffin

Beriah Magoffin was the 21st Governor of Kentucky, serving during the early part of the Civil War. Personally, Magoffin adhered to a states' rights position, including the right of a state to secede from the Union, and he sympathized with the Confederate cause...

appointed Buckner adjutant general, promoted him to major general, and charged him with revising the state's militia laws. The state was torn between Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

and Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

, with the legislature supporting the former and the governor the latter. This led the state to declare itself officially neutral

Neutrality (international relations)

A neutral power in a particular war is a sovereign state which declares itself to be neutral towards the belligerents. A non-belligerent state does not need to be neutral. The rights and duties of a neutral power are defined in Sections 5 and 13 of the Hague Convention of 1907...

. Buckner assembled 61 companies

Company (military unit)

A company is a military unit, typically consisting of 80–225 soldiers and usually commanded by a Captain, Major or Commandant. Most companies are formed of three to five platoons although the exact number may vary by country, unit type, and structure...

to defend Kentucky's neutrality.

The state board that controlled the militia considered it to be pro-secessionist

Secession in the United States

Secession in the United States can refer to secession of a state from the United States, secession of part of a state from that state to form a new state, or secession of an area from a city or county....

and ordered it to store its arms. On July 20, 1861, Buckner resigned from the state militia, declaring that he could no longer perform his duties due to the board's actions. That August he was twice offered a commission as a brigadier general

Brigadier general (United States)

A brigadier general in the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, is a one-star general officer, with the pay grade of O-7. Brigadier general ranks above a colonel and below major general. Brigadier general is equivalent to the rank of rear admiral in the other uniformed...

in the Union Army

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

—the first from general in chief Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852....

, and the second from Secretary of War

United States Secretary of War

The Secretary of War was a member of the United States President's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War," was appointed to serve the Congress of the Confederation under the Articles of Confederation...

Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of War for Abraham Lincoln at the start of the American Civil War. After making his fortune in railways and banking, he turned to a life of politics. He became a U.S. senator in 1845 for the state of Pennsylvania,...

following the personal order of President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

—but he declined. After Confederate Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk

Leonidas Polk

Leonidas Polk was a Confederate general in the American Civil War who was once a planter in Maury County, Tennessee, and a second cousin of President James K. Polk...

occupied Columbus, Kentucky

Columbus, Kentucky

Columbus is a city in Hickman County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 229 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Columbus is located at .According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of , all of it land....

, violating the state's neutrality, Buckner accepted a commission as a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

on September 14, 1861, and was followed by many of the men he formerly commanded in the state militia. When his Confederate commission was approved, Union officials in Louisville indicted him for treason and seized his property. (Concerned that a similar action might be taken against his wife's property in Chicago, he had previously deeded it to his brother-in-law.) He became a division

Division (military)

A division is a large military unit or formation usually consisting of between 10,000 and 20,000 soldiers. In most armies, a division is composed of several regiments or brigades, and in turn several divisions typically make up a corps...

commander in the Army of Central Kentucky under Brig. Gen. William J. Hardee

William J. Hardee

William Joseph Hardee was a career U.S. Army officer, serving during the Second Seminole War and fighting in the Mexican-American War...

and was stationed in Bowling Green, Kentucky

Bowling Green, Kentucky

Bowling Green is the third-most populous city in the state of Kentucky after Louisville and Lexington, with a population of 58,067 as of the 2010 Census. It is the county seat of Warren County and the principal city of the Bowling Green, Kentucky Metropolitan Statistical Area with an estimated 2009...

.

Fort Donelson

After Union Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant captured Fort HenryBattle of Fort Henry

The Battle of Fort Henry was fought on February 6, 1862, in western Tennessee, during the American Civil War. It was the first important victory for the Union and Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the Western Theater....

on the Tennessee River

Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately 652 miles long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names...

in February 1862, he turned his sights on nearby Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson was a fortress built by the Confederacy during the American Civil War to control the Cumberland River leading to the heart of Tennessee, and the heart of the Confederacy.-History:...

on the Cumberland

Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a waterway in the Southern United States. It is long. It starts in Harlan County in far southeastern Kentucky between Pine and Cumberland mountains, flows through southern Kentucky, crosses into northern Tennessee, and then curves back up into western Kentucky before...

. Western Theater

Western Theater of the American Civil War

This article presents an overview of major military and naval operations in the Western Theater of the American Civil War.-Theater of operations:...

commander Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston served as a general in three different armies: the Texas Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army...

sent Buckner to be one of four brigadier generals defending the fort. In overall command was the influential politician and military novice John B. Floyd

John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd was the 31st Governor of Virginia, U.S. Secretary of War, and the Confederate general in the American Civil War who lost the crucial Battle of Fort Donelson.-Early life:...

; Buckner's peers were Gideon J. Pillow and Bushrod Johnson

Bushrod Johnson

Bushrod Rust Johnson was a teacher, university chancellor, and Confederate general in the American Civil War. He was one of a handful of Confederate generals who were born and raised in the North.-Early life:...

.

Buckner's division defended the right flank of the Confederate line of entrenchments that surrounded the fort and the small town of Dover, Tennessee

Dover, Tennessee

Dover is a city in Stewart County, Tennessee, United States, westnorthwest of Nashville on the Cumberland River. An old national cemetery is in Dover. The population was 1,442 at the 2000 census...

. On February 14, the Confederate generals decided they could not hold the fort and planned a breakout, hoping to join with Johnston's army, now in Nashville

Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat of Davidson County. It is located on the Cumberland River in Davidson County, in the north-central part of the state. The city is a center for the health care, publishing, banking and transportation industries, and is home...

. At dawn the following morning, Pillow launched a strong assault against the right flank of Grant's army, pushing it back 1 mile. Buckner, not confident of his army's chances and not on good terms with Pillow, held back his supporting attack for over two hours, which gave Grant's men time to bring up reinforcements and reform their line. Buckner's delay did not prevent the Confederate attack from opening a corridor for an escape from the besieged fort. However, Floyd and Pillow combined to undo the day's work by ordering the troops back to their trench positions.

Late that night the generals held a council of war

Council of war

A council of war is a term in military science that describes a meeting held to decide on a course of action, usually in the midst of a battle. Under normal circumstances, decisions are made by a commanding officer, optionally communicated and coordinated by staff officers, and then implemented by...

in which Floyd and Pillow expressed satisfaction with the events of the day, but Buckner convinced them that they had little realistic chance to hold the fort or escape from Grant's army, which was receiving steady reinforcements. His defeatism carried the meeting. General Floyd, concerned he would be tried for treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

if captured by the North, sought Buckner's assurance that he would be given time to escape with some of his Virginia regiments before the army surrendered. Buckner agreed and Floyd offered to turn over command to his subordinate, Pillow. Pillow immediately declined and passed command to Buckner, who agreed to stay behind and surrender. Pillow and Floyd were able to escape, as did cavalry commander Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest was a lieutenant general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. He is remembered both as a self-educated, innovative cavalry leader during the war and as a leading southern advocate in the postwar years...

.

That morning, Buckner sent a messenger to the Union Army requesting an armistice and a meeting of commissioners to work out surrender terms. He may have been hoping Grant would offer generous terms, remembering the assistance he gave Grant when he was destitute, but Grant had no sympathy for his old friend and his reply included the famous quotation, "No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works." To this, Buckner responded:

Grant was courteous to Buckner following the surrender and offered to loan him money to see him through his impending imprisonment, but Buckner declined. The surrender was a humiliation for Buckner personally, but also a strategic defeat for the Confederacy, which lost more than 12,000 men and much equipment, as well as control of the Cumberland River, which led to the evacuation of Nashville.

Invasion of Kentucky

While Buckner was a Union prisoner of warPrisoner of war

A prisoner of war or enemy prisoner of war is a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict...

at Fort Warren

Fort Warren (Massachusetts)

Fort Warren is a historic fort on the Georges Island at the entrance to Boston Harbor. The fort is pentagonal, made with stone and granite, and was constructed from 1833–1861, completed shortly after the beginning of the American Civil War...

in Boston

Boston

Boston is the capital of and largest city in Massachusetts, and is one of the oldest cities in the United States. The largest city in New England, Boston is regarded as the unofficial "Capital of New England" for its economic and cultural impact on the entire New England region. The city proper had...

, Kentucky Senator Garrett Davis

Garrett Davis

Garrett Davis was a U.S. Senator and Representative from Kentucky.Born in Mount Sterling, Kentucky, Garrett Davis was the brother of Amos Davis. After completing preparatory studies, Davis was employed in the office of the county clerk of Montgomery County, Kentucky, and afterward of Bourbon...

unsuccessfully sought to have him tried for treason. On August 15, 1862, after five months of writing poetry in solitary confinement, Buckner was exchanged for Union Brig. Gen. George A. McCall

George A. McCall

George Archibald McCall was a United States Army officer who became a brigadier general and prisoner of war during the American Civil War. He was also a naturalist.-Biography:...

. The following day he was promoted to major general and ordered to Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga is the fourth-largest city in the US state of Tennessee , with a population of 169,887. It is the seat of Hamilton County...

, to join Gen. Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg was a career United States Army officer, and then a general in the Confederate States Army—a principal commander in the Western Theater of the American Civil War and later the military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.Bragg, a native of North Carolina, was...